Abstract

Colorectal cancer (CRC) represents one of the leading causes of tumor-related deaths worldwide. Among the various tools at physicians’ disposal for the diagnostic management of the disease, tomographic imaging (e.g., CT, MRI, and hybrid PET imaging) is considered essential. The qualitative and subjective evaluation of tomographic images is the main approach used to obtain valuable clinical information, although this strategy suffers from both intrinsic and operator-dependent limitations. More recently, advanced imaging techniques have been developed with the aim of overcoming these issues. Such techniques, such as diffusion-weighted MRI and perfusion imaging, were designed for the “in vivo” evaluation of specific biological tissue features in order to describe them in terms of quantitative parameters, which could answer questions difficult to address with conventional imaging alone (e.g., questions related to tissue characterization and prognosis). Furthermore, it has been observed that a large amount of numerical and statistical information is buried inside tomographic images, resulting in their invisibility during conventional assessment. This information can be extracted and represented in terms of quantitative parameters through different processes (e.g., texture analysis). Numerous researchers have focused their work on the significance of these quantitative imaging parameters for the management of CRC patients. In this review, we aimed to focus on evidence reported in the academic literature regarding the application of parametric imaging to the diagnosis, staging and prognosis of CRC while discussing future perspectives and present limitations. While the transition from purely anatomical to quantitative tomographic imaging appears achievable for CRC diagnostics, some essential milestones, such as scanning and analysis standardization and the definition of robust cut-off values, must be achieved before quantitative tomographic imaging can be incorporated into daily clinical practice.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, Computed tomography, Magnetic resonance imaging, Positron emission tomography, Parametric imaging, Perfusion imaging, Diffusion imaging, Texture analysis

Core tip: While encouraging progress has been made in the management of colorectal cancer (CRC), it still remains among the malignancies with higher incidence and mortality. Tomographic imaging plays a crucial role in the diagnosis, staging and evaluation of treatment responses in CRC; however, it may also conceal critical information that could guide treatment decisions. The quantitative analysis of computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography/CT images could unveil novel promising biomarkers in the form of numerical parameters. These parameters, if validated in terms of their clinical significance, may contribute to redefining the role of diagnostic imaging and improving CRC management.

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the malignancies with the highest incidence in Western countries and is the third most common cancer in both men and women[1]. The TNM staging classification of CRC, based on the depth of tumor invasion (T), lymph node involvement (N) and metastatic spread (M), is strongly associated with the 5-year survival rate[2]. Therefore, the timely identification of CRC represents a critical step to prevent the growth of invasive neoplasms. Similarly, accurate preoperative staging is necessary to differentiate CRCs with a good prognosis from those with a poor prognosis to select the most appropriate treatment and to optimize outcomes.

Currently, various imaging modalities are recommended for the clinical evaluation of patients affected by CRC for diagnosis, characterization (differentiation between mucinous and nonmucinous tumors), staging (depth of tumor spread, extramural vascular invasion, and the presence of malignant lymph nodes and distant metastasis), surgical planning (circumferential resection margin and sphincteric involvement in rectal cancer), the assessment of posttreatment tumor responses and follow-up after therapy[3-5]. Among these, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) associated with CT (18FDG-PET/CT) or MRI (18FDG-PET/MRI) play a crucial role in the management of CRC. Qualitative evaluation represents the conventional approach to the use of these imaging modalities

The growth of CRC is accompanied by the activation of numerous biological processes, such as neoangiogenesis and anarchic cellular proliferation, and an increase in cellular energy metabolism and glucose consumption. These processes determine neoplastic heterogeneity, which is characterized by a misshapen, irregular and disorganized tissue architecture with areas of high cell density, hypoxia, necrosis, hemorrhage and myxoid changes. Intratumor heterogeneity tends to change over time and to increase as tumors grow, impacting local and distant neoplastic invasion, the delivery of chemotherapeutic agents, cellular resistance to chemotherapy and radiotherapy and, consequently, prognosis[6].

The current state-of-the-art CT, MRI, and hybrid PET scanners offer the possibility to obtain structural, functional and molecular information about these biological neoplastic processes. Their “in vivo” quantitative evaluation can add value to the diagnostic management of CRC in different clinical settings. Parametric analysis (PA) allows the extraction of the numerical data contained in the voxels of each image and information regarding their processing in terms of parametric maps, parameter distributions, and the quantification of spatial complexity and density, signal intensity or activity for CT, MRI or PET, respectively, by using time curves and volumetry[7-9]. PA requires the drawing of a region of interest (ROI) that includes the target tissue for analysis. Depending on the imaging modalities and techniques used, it is possible to obtain different quantitative parameters that are representative of peculiar neoplastic features such as perfusion, structural heterogeneity, cellularity, oxygenation and glucose consumption.

The present review describes the role of imaging PA in patients with CRC by focusing on its technical features, clinical advantages and limitations in advanced quantitative functional and molecular imaging, such as diffusion-weighted MRI (DWI), perfusion imaging (PI), blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) MRI, MR spectroscopy (MRSI) and metabolic imaging as well as advanced quantitative image analysis techniques, such as texture analysis (TA) and volumetry.

LIMITATIONS OF THE CONVENTIONAL QUALITATIVE ASSESSMENT OF MORPHOLOGICAL IMAGING

The evaluation of images based on morphological features represents the routine clinical approach to CT and MRI. Although this diagnostic approach is recommended in clinical guidelines for the management of CRC, it suffers from several limitations, as shown in Table 1. In particular, the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) have been introduced for standardizing the assessment of tumor responses to cytotoxic chemotherapy, and they are mainly based on tumor size measurements[10]. However, it has been observed that RECIST can underestimate both responses to chemotherapy (alone or coupled with antiangiogenic agents) and focal therapies[8,11-13]. Indeed, solid tumors may respond to therapies by developing intratumoral necrotic areas and/or cystic or myxoid degeneration; as a result, the overall size of the neoplasm may be reduced, unchanged or paradoxically increased[12,14,15].

Table 1.

Current limitations of qualitative imaging based on morphological features used for the assessment of colorectal cancer

| Diagnostic task | Limits of qualitative imaging |

| Primary tumor identification | Early stages of CRC hard to detect |

| Neoplastic and inflammatory tissue not easily differentiable | |

| Lymph node involvement | Lymph node size criteria often misleading and insufficient |

| Shape, border irregularity and structural heterogeneity hard to assess for small lymph nodes | |

| Prediction of early responses to chemotherapy and radiation therapy | Not possible with qualitative evaluation alone |

| Evaluation of treatment responses and the detection of recurrent disease | Differentiation of residual or recurrent neoplastic tissue from posttreatment induced fibrosis or necrosis is often challenging |

CRC: Colorectal cancer.

To overcome the above-described limitations, parametric imaging could a useful tool to integrate the information obtained from morphological imaging. PA allows the extraction of numerical data as either quantitative parameters (processed according to a pharmacokinetic model and expressed as an absolute amount with a corresponding unit of measurement) or as semiquantitative parameters (as a ratio of the measured amount and a standard of reference and expressed as pure number). In the following text, for the sake of simplicity, we will use the term quantitative to indicate both quantitative and semiquantitative parameters.

ADVANCED QUANTITATIVE FUNCTIONAL AND MOLECULAR IMAGING

Physiological aspects and technical features

DWI with apparent diffusion coefficient maps: DWI is a functional MR technique that measures the Brownian motion of water molecules in biological tissues, which is restricted by an increase in cellularity and architectural tissue changes[16,17]. Consequently, water diffusion properties are altered in tumors because of the coexistence of dense cellularity, fibrosis, necrosis, neovascularization and hemorrhage. In detail, the increased tissue cellularity observed in the solid part of a tumor reduces the intercellular space and consequently restricts Brownian motion. By using DWI, it is possible to calculate a quantitative measure of water molecule diffusion over time, known as the ADC. The apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) value is expressed as 10-3 mm2/s and can be calculated for each unit volume (voxel) to provide a parametric ADC map. In particular, ADC has been shown to be inversely related to tumor cellularity, and it has been clinically applied to distinguish benign from malignant tumors, to assess tumor grade, to delineate the extent of a tumor, to define the classes of risk that influence the prognosis, and to evaluate and predict tumor treatment responses in CRC patients[18,19] (Figure 1).

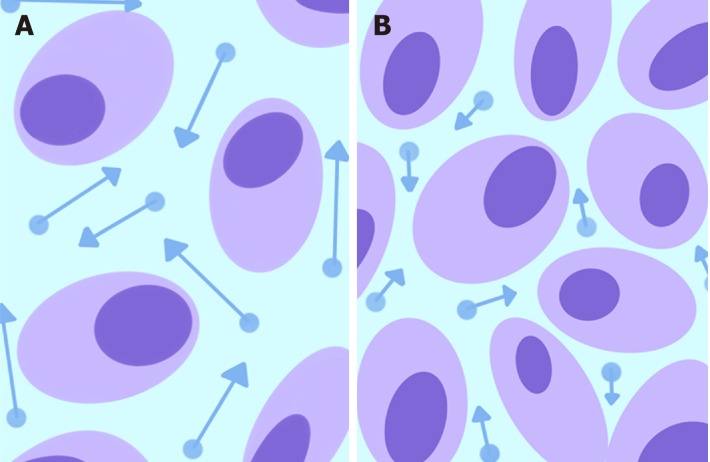

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of water molecule diffusion (dots) in the extracellular space. Normal tissues (A) show a relatively larger extracellular space with high water diffusion (longer arrow vectors higher ADC values), whereas the increased tissue cellularity in a neoplasm (B) reduces the intercellular space and consequently restricts diffusion (shorter arrow vectors lower ADC values).

PI based on dynamic contrast enhanced CT or MRI: Neoangiogenesis, a process induced by the upregulation of vascular growth factors, is a well-known critical aspect of CRC that leads to the development of a new, altered and immature microcirculatory network inside the tumor[20-22]. In particular, neoangiogenesis promotes an irregular architectural vascular pattern[23] with areas of low vascular density and regions of high angiogenic activity. Consequently, neoangiogenesis causes structural heterogeneity due to the coexistence of areas of high cell density, necrosis, hemorrhage and myxoid changes within tumoral tissue[24].

The above-described phenomena can be investigated using a functional modality such as PI based on dynamic contrast enhanced (DCE). DCE imaging consists of the acquisition of baseline images before intravenous contrast agent injection, followed by subsequent image acquisition over time[25]. PI is an advanced DCE quantitative technique based on the repeated high frequency acquisition of images, which allows the assessment of changes in signal intensity over time. It can be performed with both CT and MRI scanners. PI allows the assessment of vascularity in biological tissues in terms of tumor vessel features (perfusion, permeability, and density), extracellular-extravascular space composition and plasma volume[25]. In the following text, we will use the terms DCE and PI interchangeably. A broad spectrum of quantitative parameters can be obtained using PI to assess the vascular properties of pathological tissues[22] (Figure 2). A summary of the main PI quantitative parameters used in the assessment of CRC is shown in Table 2[26,27]. There is a growing interest in the role of PI in clinical practice for tumor detection and characterization and the assessment of responses to therapy (especially with respect to antiangiogenic treatment strategies) and prognosis.

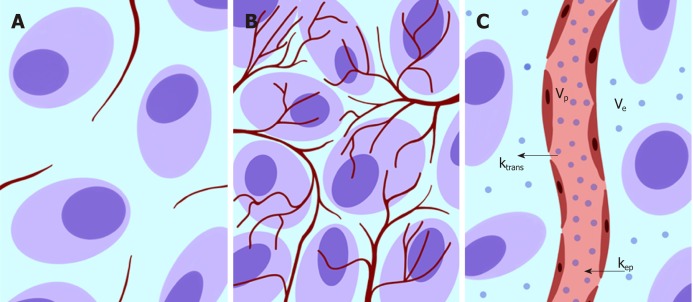

Figure 2.

Schematic representation showing vascularization changes in normal tissue (A) and neoplastic neoangiogenesis (B). In C, a typical bicompartmental model (extended Toft’s model) is depicted with various parameters that can be assessed according to the tissue contrast agent concentration (dots) and the arterial input function data.

Table 2.

Main quantitative parameters extracted from perfusion imaging of colorectal cancer

| Parameter name | Parameter definition | Parameter significance |

| Regional blood flow | Blood flow per unit volume or mass of tissue, expressed in mL of blood/min/100 mL tissue | It reflects the rate of the delivery of oxygen and nutrients to a certain tissue |

| Regional blood volume | Volume of capillary blood contained in a certain volume of tissue, expressed in mL blood/100 mL of tissue | It reflects the functional vascular volume |

| Mean transit time | Mean time needed for blood to pass through the capillary network, expressed in seconds | It reflects the time required for the contrast agent bolus to pass through tissue |

| Permeability-surface area product (PS) | Flow of molecules through the capillary membranes in a certain volume of tissue, expressed in mL/min/100 mL tissue | It reflects the vascular leakage rate in the microcirculation |

| Transfer constant (KTrans) | Rate at which the contrast agent transfers from the blood to the interstitium (rate of contrast extraction) | It reflects the balance between capillary permeability and blood flow in a tissue |

| Tissue interstitial volume (Ve) | Volume of extravascular and extracellular contrast agent in a certain tissue, expressed as a percentage | It is a measure of cell density |

| Rate constant (Kep) | Rate at which the contrast agent returns from the extravascular-extracellular space to the vascular compartment: Kep = Ktrans/Ve | It reflects the tissue microcirculation and contrast agent permeability |

Hybrid Imaging: 18FDG-PET/CT and 18FDG-PET/MRI are molecular and morphological imaging techniques that couple the metabolic and anatomical assessment of tumor lesions[28]. 18F-FDG is an analog of glucose that is transported into cells through membrane glucose transporter proteins after intravenous administration[29]. Since malignant cells have increased glucose consumption (Figure 3), a preferential accumulation of 18F-FDG occurs in cancer cells compared to normal cells[30]. The uptake of 18F-FDG detected by PET can be quantified using parameters such as the standardized maximum or mean uptake value (SUVmax or SUVmean), the metabolic tumor volume (MTV) or the total lesion glycolysis (TLG). The SUVmax is defined as the uptake value of the pixel with the highest activity inside an ROI divided by the injected dose (which has to be corrected for decay and normalized for the patient’s weight or body surface). The SUVmean is the average of all the uptake values of the pixels within an ROI. The MTV is defined as the volume of tumor tissues with pathological FDG uptake and calculated as follows: All the voxels inside a tridimensional ROI with SUV values above a determined threshold are included in the final volume; the threshold may be represented by the absolute value (≥ 2.5 or ≥ 3 or ≥ 3.5) or the percentage (≥ 20% or ≥ 30% or ≥ 40% or ≥ 50%) of the SUVmax. As a result, the MTV incorporates the characteristics of both the volumetric data and the metabolic activity of the tumor. Finally, the TLG is calculated according to the following formula: SUVmean × MTV. 18FDG-PET/CT has played a role in clinical practice in the detection of extrahepatic distant metastasis, the evaluation of tumor responses to therapy and the follow-up of treated patients with rising serum carcinoembryonic antigen levels without detectable disease according to morphological imaging.

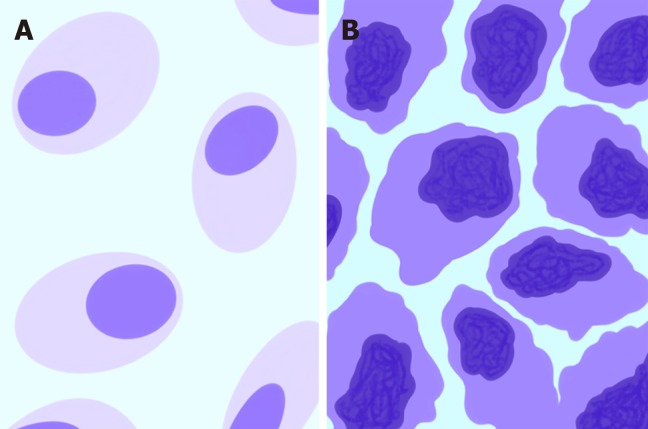

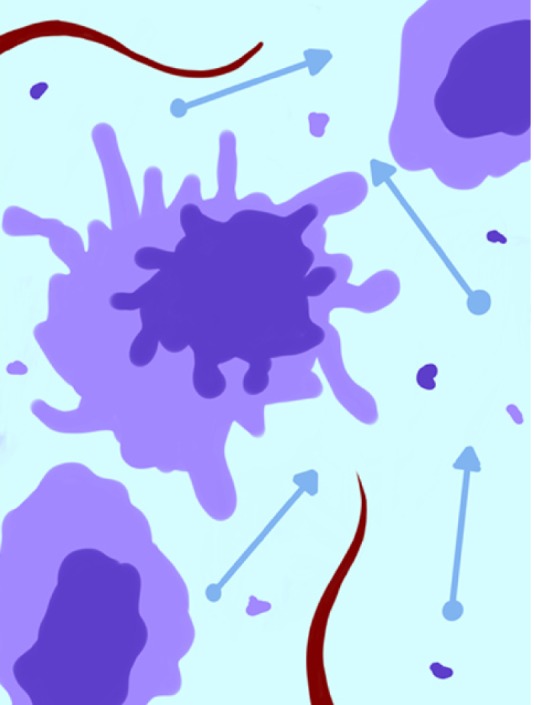

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of morphological and metabolic features of normal tissue (A) compared with those of neoplastic malignant cells (B). The darker shade of violet represents the higher glucose consumption typical of malignant cells.

While the potential use of non-FDG PET radiotracers in CRC imaging is a current topic of investigation, we refrained from discussing this matter in the present review due to the dearth of clinically oriented evidence available in the current literature.

Primary tumor identification, tumor grading and differentiation, and local staging

While endoscopy is considered the main diagnostic tool for the detection of CRC, imaging has the potential to identify primary tumors. Nevertheless, both malignant and benign abnormalities (e.g., inflammatory bowel disease, complicated diverticulitis, and hyperplasic polyps and adenomas) can present with an increase in bowel wall thickness or as polypoid lesions. When using conventional imaging, differential diagnosis is mainly based on morphological features (e.g., lesion size and longitudinal extension, the evaluation of the transitional zone between pathological and healthy mucosa, the presence of focal or multifocal intestinal involvement, the preservation of mural stratification, and the pattern of mesenteric and lymph node involvement). Although all these characteristics contribute the most to the determination of the correct diagnosis, parametric imaging could increase the overall diagnostic accuracy; moreover, it may be useful for the tumor grading and differentiation and local staging.

DWI with ADC maps: ADC values have been investigated as possible quantitative parameters that are useful for differential diagnosis. Kilickesmez et al[31] reported that mean ADC values may be used to differentiate recto-sigmoid malignancy from both normal rectum and inflammatory bowel disease-affected tissues. The mean ADC value (0.97 × 10-3 mm2/s) of the recto-sigmoid tumor group was significantly different from those of the healthy control (1.47 × 10-3 mm2/s) and inflammatory bowel disease groups (1.37 × 10-3 mm2/s). A recent metanalysis[32] reported that the ADC values of CRC malignant lesions ranged from 0.97 × 10-3 mm2/s to 1.19 × 10-3 mm2/s, while those of benign lesions ranged from 1.37 × 10-3 mm2/s to 2.69 × 10-3 mm2/s.

The ADC value might serve as a potential noninvasive biomarker of CRC tumor aggressiveness. Indeed, Curvo-Semedo et al[33] reported significantly lower ADCmean values in poorly differentiated versus well-differentiated RC, as well as in a T3-T4 stage group versus a T1-T2 stage group. Additionally, Tong et al[34] showed a negative correlation between ADC values and extramural maximal depth in RC.

PI: Quantitative perfusion parameters have been reported as feasible tools that could be used to discriminate between CRC and noncancerous diseases. Goh et al[35] reported that the blood volume (BV), blood flow (BF), mean transit time (MTT), and permeability-surface area product (PS) determined based on perfusion CT were significantly different between patients with CRC and diverticulitis. In particular, the CRC group showed significantly higher BV, BF and PS and a shorter MTT compared to the diverticulitis group. These findings are correlated with neoangiogenesis processes associated with CRC growth. Similarly, Shen et al[36] showed that transfer constant (Ktrans) values obtained from perfusion MRI were significantly higher in rectal cancer (RC) compared to those in benign abnormalities (0.267 min-1 ± 0.07 vs 0.118 min-1 ± 0.03), indicating that significant angiogenesis and abnormal vasculature enhanced the influx of the contrast agent. Using a 0.156 min-1 cut-off value for Ktrans, a sensitivity of 100.0% and a specificity of 93.3% were observed when discriminating RC patients from controls.

Sun et al[37] reported that the mean BF and BV obtained from perfusion CT were significantly different among well, moderately, and poorly differentiated tumors (61.17 ± 17.97, 34.8 ± 13.06 and 22.24 ± 9.31 mL/min/100 g, respectively). The same working group confirmed these findings, providing further evidence that BF, when determined using perfusion CT images, is associated with tumor grade[38].

Hybrid imaging: Due to its utilization of a combination of morphological and molecular information, 18FDG-PET/CT has a high sensitivity for the detection of colorectal lesions. However, unlike determinations based on metabolic information, there is no established consensus regarding the discrimination of benign lesions from premalignant or malignant lesions based on visual appearance alone. A quantitative approach to focal colorectal uptake has been investigated. A few studies have observed that PET quantitative parameters could help to differentiate benign from premalignant or malignant lesions[39], while there have been other studies that have found the opposite[40,41]. Moreover, a quantitative approach may be useful for local staging. Liao et al[42] reported that quantitative parameters such as MTV calculated with a 2.5 threshold aided in discriminating the pT1-T2 group from the pT3-T4 group in patients with RC. The MTV2.5 values for the pT1-T2 and pT3-T4 patient groups were 11.6 ± 11.4 and 34.6 ± 21.4, respectively. Using the median value of 28 mL as a cut-off, MTV2.5 provided excellent specificity (92.8%) and a positive predictive value (97.1%) for the T3-T4 group, helping to identify patients who would benefit from preoperative chemoradiation therapy (CRT).

Lymph node involvement

Nodal involvement has an important role in the stratification of risk for CRC patients, and an accurate assessment of this parameter could significantly influence therapeutic management and prognosis. Morphological criteria (size, margins, structural disomogeneity, and clustering) have been used for the detection of pathological lymph node involvement[43-47]; however, this approach is still highly debated.

DWI with ADC maps: Quantitative ADC values extracted from DWI have been proposed as tools to differentiate between benign and malignant lymph nodes; however, their role remains unclear in this setting. Heijnen et al[48] reported that DWI can facilitate lymph node detection during the primary staging of RC, but although the ADCmean value was higher for benign nodes compared to malignant nodes (1.15 × 10-3 mm2/s vs 1.04 × 10-3 mm2/s), the difference was not statistically significant. Lambregts et al[49] assessed the performance of ADC measurements for nodal restaging in patients with RC undergoing preoperative CRT. The authors reported that the ADCmean value of malignant lymph nodes after CRT was significantly higher compared to that of benign lymph nodes (1.43 × 10-3 mm2/s ± 0.38 vs 1.19 × 10-3 mm2/s ± 0.27)[49]. This finding was attributed to the induction of posttreatment necrosis, which increases the diffusivity and consequently the ADC value. However, the overlapping of ADC values between benign and malignant nodes resulted in insufficient accuracy when ADC values were used alone for the detection of nodal metastases after CRT.

PI: PA of PI could further increase the diagnostic accuracy of conventional imaging for nodal involvement evaluation in RC patients[50-54]. Ambruster et al[50] have reported that DCE-MRI quantitative maps increase both the sensitivity (86% vs 71%) and specificity (90% vs 70%) of conventional MRI for the detection of malignant lymph nodes in locally advanced RC (LARC). Grovik et al[51] and Yeo et al[52] found that Ktrans values obtained for primary tumors with perfusion MRI were strongly correlated with nodal status in surgical specimens. Yu et al[55] reported that metastatic lymph nodes from RC showed significantly higher Ktrans values and tissue interstitial volume (Ve) compared with nonmetastatic lymph nodes during perfusion MRI of lymph nodes with short axis diameters > 5 mm (Ktrans: 0.484 min-1 ± 0.198 vs 0.218 min-1 ± 0.116; Ve: 0.399 ± 0.118 vs 0.203 ± 0.096). Conversely, Yang et al[54] demonstrated that the Ktrans values were significantly lower in metastatic lymph nodes from RC during perfusion MRI of lymph nodes with short axis diameters < 5 mm. However, when using a Ktrans cut-off value of 0.088 min-1 to differentiate between positive and negative lymph nodes, a sensitivity of 60.5% and a specificity of 81.5% were observed.

Hybrid imaging: Qualitative evaluation with 18FDG-PET/CT for the assessment of nodal involvement has limited advantages compared to evaluation with CT[56,57], but a quantitative approach might be utilized to overcome this limitation. Tsunoda et al[58] compared the diagnostic accuracy of visual analysis and SUVmax evaluation for lymph node metastases using 18FDG-PET/CT in patients with CRC. The sensitivity, specificity and accuracy were 28.6%, 92.9% and 75.0%, respectively, when using a visual approach, while they were 53.1%, 90.6% and 80.1%, respectively, when using a SUVmax cut-off value of 1.5. The mean SUVmax of the malignant lymph nodes (6.3; range: 1.0-33.8) was significantly higher than that of the benign lymph nodes (2.5; range: 1.3-3.3). Similarly, Yu et al[59] observed that a quantitative approach based on the use of SUVmax might improve the detection of regional lymph node metastasis when using 18FDG-PET/CT in patients with CRC. A significant difference in SUVmax between metastatic and benign juxtaintestinal lymph nodes was observed. When using a cut-off value for SUVmax of 2.0, the corresponding sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV were 91.4%, 87.8%, 69.6% and 97.1%, respectively.

Response to treatment: efficacy prediction and the assessment of neoadjuvant CRT in RC

CRT has become the standard of care for LARC. This treatment is associated with fewer local recurrences and may also result in improved long-term survival. The preoperative noninvasive assessment of CRT response in LARC is crucial for planning the surgical approach. MRI is largely used for the local restaging of LARC after neoadjuvant CRT; however, conventional morphological sequences have intrinsic limitations when used for the differentiation of residual viable tumors from surrounding fibrosis[60,61]. The overall accuracy of local neoplastic restaging using only morphological T2-weighted (T2w) sequences after CRT is reported to be 47-52%[61,62]. CRT induces the necrosis of neoplastic tissue as well as reductions in cellular density and metabolism, increases in the extracellular space and the suppression of neoangiogenesis (Figure 4); these phenomena can be investigated via PA of tomographic images.

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of neoplastic tissue after treatment. Cytolysis increases the extracellular space and consequently water diffusion and reduces lesion vascularization and metabolism.

DWI with ADC maps: Several studies[49,63-65] have shown the usefulness of ADC values for the assessment of tumor responses to preoperative CRT, suggesting that the increase of ADC values after CRT is associated with a good response to preoperative CRT. The absence of ADC value changes during CRT could be used to identify nonresponding patients[66]. The increase in ADC in neoadjuvant CRT responders may be due to cell death, cellular membrane disruption and decreased cellularity, which contribute to increased water diffusion. Regarding the assessment of post-CRT residual tumors in LARC, Song et al[67] reported that the mean ADC after CRT of viable tumors (0.93 × 10-3 mm2/s) differed significantly from that of nonviable tumors (1.55 × 10-3 mm2/s). Moreover, when an ADC value of 1.045 x 10-3 mm2/s was used as a cut-off value for distinguishing between viable and nonviable tumors, false positive findings were not observed, resulting in a specificity and positive predictive value of 100%. In the same clinical setting, Grosu et al[68] reported that the ADCmean after CRT of viable tumors (1.02 × 10-3 mm2/s) differed significantly from that of scar tissue (1.77 × 10-3 mm2/s). An ADC cut-off value of 1.34 × 10-3 mm2/s resulted in a sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of 93%, 91%, and 92%, respectively. Bassaneze et al[69] reported that patients with pathological complete responses (pCRs) to neoadjuvant treatment differed significantly from those with non-pCRs in terms of the absolute value of the post-CRT ADC. The mean post-CRT ADC value was 1.53 × 10-3 mm2/s in the pCR patient group and 1.16 × 10-3 mm2/s in the non-pCR patient group. All patients with residual tumors in the surgical specimen showed ADC values that were below the cut-off of 1.49 × 10-3 mm2/s.

However, conflicting results have been reported regarding the value of pretreatment tumor ADC values for the prediction of CRT response in patients with LARC when using surgical specimens as the standard of reference. Some authors observed significantly lower pretreatment ADC values in good responders compared to nonresponders[70,71]. Conversely, others reported that the pretreatment ADC values were not significantly different between responders and nonresponders[72].

PI: Perfusion CT quantitative parameters have been evaluated for the prediction and assessment of the response of LARC to neoadjuvant CRT. Bellomi et al[73] reported that the baseline BF and BV were significantly higher and the MTT was significantly lower in responders compared to nonresponders. Conversely, Sahani et al[74] and Curvo-Semedo et al[75] reported that the baseline BF was significantly higher and the MTT was significantly lower in non-responders compared to responders. Additionally, both groups[73,75] reported a reduction in BF, BV and PS and an increase in MTT after CRT. These perfusion changes are thought to be due to CRT-related fibrosis, which causes the compression of tumor capillaries, a decreased number of arteriovenous shunts, an increased resistance to flow and a reduced volume in the vascular bed[76]. A reduction of 40% or more in BF, BV and permeability was observed in patients with RC who responded to neoadjuvant therapy[22,77].

A few studies have evaluated the usefulness of perfusion MRI quantitative parameters for predicting and assessing responses to preoperative treatment in LARC. Lim et al[78] reported that pre-CRT Ktrans values were significantly higher in the downstaged group after CRT than in the non-downstaged group. Tong et al[79] reported that patients with pCR had significantly higher Ktrans, Ve and rate constant (Kep) values before CRT than non-pCR patients. In particular, a Ktrans threshold of 0.66 had a sensitivity of 100% for predicting pCR. Gollub et al[80] observed that Ktrans was significantly lower for tumors from patients with pCR compared with patients with non-pCR after neoadjuvant chemotherapy; moreover, the posttreatment Ktrans value was correlated with the percentage tumor response and final tumor size according to histopathology. Kim et al[64] showed a significant reduction in the Ktrans values in the downstaged group after CRT compared to that in the nondownstaged group. Furthermore, the percentage difference between the pre- and post-CRT Ktrans values in the downstaged group was significantly higher compared to that in the nondownstaged group, suggesting that a large decrease in the Ktrans value after CRT was associated with a good response to CRT. DeVries et al[72] investigated the prognostic value of the perfusion index, which is a microcirculatory perfusion MRI parameter representative of both flow and permeability. The perfusion index was significantly increased in patients who failed to respond to CRT.

A final remark should be made regarding the role of PI in the evaluation of the response to antiangiogenic agents. Bevacizumab is an antiangiogenic monoclonal antibody that targets vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). This kind of therapeutic agent often suppresses tumor growth in the absence of notable morphological changes and requires a direct "in vivo" evaluation of vascularity to reveal therapeutic results. Willett et al[81] showed a reduction in BF, BV and PS via perfusion CT 12 days after beginning treatment with bevacizumab alone in LARC patients.

In summary, high baseline values and marked post-CRT decreases in perfusion parameters (BF, BV and Ktrans) are predominantly reported in patients with good response. This observation suggests that highly perfused tumors may provide better access for chemotherapy, better oxygenation and higher radiosensitivity compared with poorly perfused tumors. Conversely, the following two neoplastic features may explain a high baseline perfusion parameter in patients who fail to respond to neoadjuvant CRT: (1) The presence of arteriovenous shunts, which is accompanied by a high perfusion rate but a low exchange of nutrients/chemotherapy; and (2) Tissue hypoxia, which induces a high perfusion rate.

Hybrid imaging: Several studies have investigated the role of 18FDG-PET/CT in the evaluation of responses to CRT in LARC patients. Lambrecht et al[70] observed that changes in SUVmax during (after 10-12 fractions) and 5 wk after CRT with respect to the SUVmax value prior to the beginning of CRT (ΔSUVmax) were significantly correlated with the pathological response to treatment. Janssen et al[82] reported that a cut-off value representing a 48% reduction in SUVmax after 2 wk of CRT in patients with LARC resulted in a specificity of 100% and a sensitivity of 64% when differentiating pathological responders from nonresponders. Maffione et al[83] performed a systemic review of the early prediction of responses by 18FDG-PET/CT during neoadjuvant CRT in LARC. The percentage decrease in SUVmax showed a high accuracy (mean sensitivity 82%; pooled sensitivity 85%) in terms of the early prediction response when using a mean cut-off of 42%. As a result, the early assessment of nonresponding patients allows the modification of the treatment strategy, especially in terms of timing and the type of surgical approach used. It should be noted that radiation-induced inflammation could cause increased 18FDG uptake, possibly reducing PET specificity[82,84-87]. To overcome this limitation, the use of dual-time 18F-FDG PET has been proposed. This requires two PET scans; the first is conducted 40-60 min after the injection of 18F-FDG (standard time), and the second is conducted 90-270 min after injection (delayed time), thus allowing the evaluation of 18FDG uptake over time. While 18FDG uptake due to inflammation appears to be stable or to decrease over time, neoplastic 18FDG uptake tends to increase[88]. Yoon et al[89] compared the accuracy of pre-CRT standard and post-CRT dual-time 18FDG-PET/CT in the prediction of CRT responses in LARC patients. The quantitative dual-time score (defined as the delay index [DI], which is equal to post-SUVmax-early – post-SUVmax-delayed/post-SUVmax-delayed of post-CRT 18FDG-PET/CT) showed significantly better performance with a higher area under the curve value (0.906 vs 0.696, P = 0.018) than the standard quantitative score (defined as the response index [RI], which is equal to pre-SUVmax – post-SUVmax/ pre-SUVmax). The DI showed a sensitivity of 86.7%, a specificity of 87%, a PPV of 68.4% and a PNV of 95.2%, suggesting that dual-time post-CRT PET/CT might be the most appropriate diagnostic tool for this specific setting.

Responses to treatment: colorectal liver metastases

Surgical resection remains the only treatment with curative potential for colorectal liver metastases (CRLMs)[89]. In patients who are not suitable candidates for surgery, chemotherapy alone or in combination with local hepatic treatments, such as intrahepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy, transcatheter arterial chemo-embolization (TACE), selective internal radiation therapy (SIRTI), radiofrequency ablation (RFA), laser therapy or cryotherapy, may be performed[90]. Tomographic imaging based on conventional qualitative evaluation contributes mostly to defining the appropriate therapeutic management of CRLMs[91,92]; however, defining tumor biology could allow the improved selection of treatment strategies and, as a result, the more accurate prognostic evaluation of patients[90]. In this setting, PA could provide potentially useful imaging markers for the prediction of treatment response.

DWI with ADC maps: ADC values have been proposed for use in assessing the responses of CRLMs to chemotherapy[93,94]. Koh et al[93] reported that high mean pretreatment ADC values for CRLMs were associated with poorer responses to chemotherapy (nonresponder: 1.55 × 10-3 mm2/s; responder 1.36 × 10-3 mm2/s). Indeed, high ADC values are observed in necrotic areas, which typically show poor perfusion and allow only limited local delivery of chemotherapeutic drugs. Cui et al[94] found that CRLMs showed significantly decreased mean pretreatment ADC values in responding lesions (0.95 × 10-3 mm2/s ± 0.15) than in nonresponding lesions (1.18 × 10-3 mm2/s ± 0.27). Furthermore, an early increase in ADC values was observed in responding lesions after 3 or 7 d of treatment.

PI: Few studies have been performed to assess the utility of quantitative PI parameters as biomarkers for the assessment of CRLM responses to treatment. Using baseline perfusion MRI and follow-up MRI evaluated on the basis of RECIST 1.1 criteria in patients with CRLMs treated with a combination of chemotherapy and bevacizumab, Coenegrachts et al[95] found significantly higher Kep values in responders than in nonresponders (responders: 0.09852; nonresponders: 0.07829). Moreover, the Kep values were significantly decreased in responding patients compared to nonresponding patients after 6, 12 and 18 weeks of treatment, suggesting that Kep values may be able to predict early treatment response in CLRMs.

Hybrid imaging: Few studies have investigated the possible role of quantitative parameters derived from18FDG-PET/CT in the assessment of CLRM treatment responses. Recently, Nishioka et al[96] observed that an SUVmean value cut-off of 3 and morphological CT criteria[10] had similar excellent predictive power for ≤ 10% tumor viability (areas under the curve of 0.916 and 0.882, respectively) compared to that for the degree of tumor shrinkage (area under the curve of 0.69) in patients who underwent PET/CT after chemotherapy and before the surgical resection of CRLMs.

CRC prognosis

Tumor stage at diagnosis is considered the most important prognostic factor for CRC patients[97]. However, other prognostic factors that include biological and molecular information should be taken into account to personalize prognosis[98]. Parameters such as tumor differentiation grade and the presence of lymphangiovascular invasion (LVI)[99] are valuable in the prognostic evaluation of RC patients. Similarly, the plasmatic levels of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)[100] are useful for the prognostic assessment of CRLMs.

As a result, detailed information regarding the individual tumor profile of each patient is critical to determine the risk for local and distant recurrence[101]. Measures such as overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS) or recurrence-free survival (RFS) are commonly used for prognostic evaluation. PA has the potential to introduce novel useful biomarkers that could correlate to the biological and genetic prognostic features of CRC and CRLMs or predict OS, PFS and/or RFS. Consequently, such parameters could be useful in CRC risk stratification and in treatment planning.

DWI with ADC maps: The quantitative evaluation of ADC maps derived from DWI could aid in the prediction of patient prognosis[16,18,70]. Curvo-Semedo et al[33] reported that ADC values differed significantly between RC tumors with and without mesorectal fascia (MRF) invasion, between N0 and N+ cancers and even among different histological grades. In particular, decreased mean pretreatment ADC values were observed in tumors with MRF involvement, metastatic lymph nodes or poorly differentiated grading. Sun et al[102] reported that decreased ADC values were strongly associated with increased T stage and a more aggressive tumor profile. Tong et al[34] observed that the extramural maximal depth and the ADC value have a significant negative correlation in the T3 RC spread. Heijmen et al[103] reported that low prechemotherapy ADC values in CRLMs predicted poorer outcomes in terms of both PFS and OS.

PI: Goh et al[104] reported that CRC with low BF at staging according to perfusion CT showed an increased tendency to metastasize and resulted in significantly decreased OS. Particularly, a group of patients who had developed metastatic disease prior to follow up presented a mean baseline BF value of 45.7, while the mean BF value of the disease-free group was 76 mL/min/100 g. Similarly, Hayano et al[76] reported that patients with RC with increased BF according to perfusion CT survived significantly longer than those with decreased BF. More recently, two studies reported that Ktrans measured via DCE-MRI is correlated with the pathological differentiation of RC; poorly differentiated tumors showed increased Ktrans values[36,105]. Moreover, Ktrans values were significantly higher in lesions with distant metastasis than in lesions without distant metastasis and in the pLVI positive group than in the pLVI negative[105] group.

Finally, perfusion MRI studies conducted on patients with CRLMs treated with bevacizumab are worth mentioning[106-108]. Indeed, Hirashima et al[106] observed a significant correlation between a reduction in the Ktrans value 7 days after the start of treatment and a longer time to progression. Subsequently, Kim et al[107] confirmed this finding and found that a reduction of 40% in the Ktrans cut-off value could be used to discriminate responders from nonresponders. De Bruyne et al[108] found that a decrease in Ktrans of more than 40% after bevacizumab chemotherapy in patients with CRLMs was associated with improved PFS.

Hybrid imaging: Avallone et al[109] evaluated the prognostic role of early metabolic responses to CRT in patients with LARC. In their study, 18FDG-PET scans were performed before and 12 days after the beginning of CRT. Responders, defined on the basis of a reduction in the SUV mean value ≥ 52% compared to the baseline, showed a 5-year RFS that was significantly higher than that of nonresponders.

Muralidharan et al[110] reported that high MTV and TLG values for CRLMs before surgical resection were significantly associated with poorer recurrence-free survival (RFS) and OS, while the SUVmax and SUVmean did not show any significant predictive ability. Lastoria et al[111] performed a 18FDG-PET/CT evaluation before and after 1 cycle of FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab treatment in patients with resectable CRLMs. Pathological responses were assessed in patients undergoing resection. For each lesion, a ≤ -50% change in the SUVmax and the TLG compared to baseline was used as a threshold to indicate a significant metabolic response. An early metabolic PET/CT response had a stronger and more independent and statistically significant predictive value for PFS and OS compared to both CT/RECIST and pathological response according to multivariate analysis. Similarly, Lau et al[112] investigated the prognostic value of 18FDG-PET/CT before and after preoperative chemotherapy in patients undergoing the liver resection of CRLMs. SUVmax, MTV, and TGV, their changes (DSUVmax, DMTV, DTGV) and their correlation with RFS and OS were evaluated. DSUVmax was the only parameter predictive of RFS and OS according to multivariate analysis. Patients with metabolically responsive tumors had an OS of 86% at 3 years vs 38% for patients with nonresponding lesions. Gulec et al[113] investigated the relationship between MTV and TLG and clinical outcomes in patients with unresectable CRLMs undergoing treatment with 90Y resin microspheres. The authors observed that MTV values below 200 cc during pretreatment PET/TC and below 30 cc during posttreatment PET/CT at 4 wk were significantly associated with a longer median survival compared to MTV values above 200 during the pretreatment exam and 30 cc during the posttreatment exam at 4 wk. Similar results were found for TLG values below and above 600 g during the pretreatment exam and below and above 100 g during the posttreatment exam, respectively.

Giacomobono et al[114] evaluated the value of SUVmax for stratifying CRC patients with unexplained CEA increases and FDG uptake at the site of anastomosis after surgical curative resection. Nonspecific FDG uptake at the anastomotic site was the most frequent cause of error because it could be due to both post-CRT/postsurgical fibrosis/scar tissue and disease recurrence. The anastomotic SUVmax was the only significant predictor of tumor recurrence at the site of anastomosis. A decreased OS was reported in patients with a SUVmax greater than 5.7 compared with that in patients with lower values (median survival: 16 mo vs 31 mo; P = 0.002). Marcus et al[115] showed that a decreased MTVtotal and TLGtotal were associated with increased OS in patients with local, loco-regional and/or distant-recurrent biopsy-verified CRC.

OTHER ADVANCED QUANTITATIVE FUNCTIONAL AND MOLECULAR IMAGING MODALITIES

Blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) MRI and MR spectroscopy (MRSI) represent further advanced imaging modalities available for use with quantitative PA in CRC.

BOLD-MRI is able to assess in vivo tissue hypoxia according to blood flow and the paramagnetic properties of deoxyhemoglobin within red blood cells[116]. Endogenous deoxyhemoglobin decreases the transverse relaxation rate (T2*) in blood, which can be quantified by R2* (= 1/T2*)[117,118]. Tumor hypoxia is caused by the inability of the neoplastic vascular system to provide an adequate supply of oxygen to the growing tumor mass. Tumor hypoxia induces the expression of the transcription factor hypoxia inducible factor-1 alpha (HIF-1α), which promotes the adaptation of cancer cells to hypoxia and the development of more aggressive clones less sensitive to radiotherapy and chemotherapy[119] and impacts metastatic spread to favor tumor recurrence and a poor prognosis. Heijmen et al[103] investigated the ability of BOLD-MRI to predict outcomes and responses to systemic treatment in patients with CRLMs undergoing MRI before and one week after the beginning of first-line chemotherapy. The authors reported that a low pretreatment T2* value in CRLMs (indicating a higher concentration of deoxyhemoglobin) was a significant predictor for increased OS; however, the T2* value did not significantly change one week after the beginning of treatment, which did not make it a useful predictor of the response to therapy.

MRSI is a noninvasive technique that allows the measurement of metabolites and metabolic processes in normal and pathological tissues[120]. The resonance frequencies of the metabolites are expressed in parts per million (ppm). Tumor tissues are characterized by disordered energy metabolism (an increased lactate concentration due to anaerobic glycolysis and the activation of the creatine/phosphocreatine system), amino acid metabolism (the accumulation of amino acids due to the increased turnover of structural proteins) and choline metabolism (increased levels of choline, which is a marker of cellular membrane turnover related to cell proliferation)[121]. Dzik-Jurasz et al[122] demonstrated the presence of choline and lipid peaks in patients with RC. Kim et al[120] reported that a choline peak at 3.2 ppm in patients with RC disappeared after radiation therapy and chemotherapy.

Both of these modalities suffer from limited clinical applicability due to their high intrinsic technical complexity; furthermore, there are still insufficient evidence in the literature to define their possible role in CRC clinical management.

QUANTITATIVE IMAGE ANALYSIS METHODS

Texture analysis

Physiological aspects and technical features: As previously stated, tumor heterogeneity is a hallmark of malignancy that is highly related to tumor biology[24,123], and it can be qualitatively and/or quantitatively evaluated by several imaging modalities. TA is a postprocessing imaging technique that allows heterogeneity quantification to evaluate both the distribution and relationships within the information contained in each voxel[123]. The content of this information depends on the imaging modality used (Hounsfield units measure density for CT, signal intensity measures tissue relaxation times for MRI, and standard uptake values measure activity for PET). A broad spectrum of quantitative parameters can be extracted from any diagnostic imaging modality, ranging from first-order parameters (defined on the basis of histogram analysis, which does not account for spatial distribution) to more complex higher-order parameters[124]. Multiple first-order parameters are available, including the mean gray-level intensity (brightness), uniformity (distribution of the gray level), entropy (a measure of irregularity), skewness (a measure of the asymmetry of the pixel histogram distribution) and kurtosis (the magnitude of the pixel histogram distribution)[125]. The analysis is performed by drawing an ROI in the largest cross-section of the tumor or in tumor subregions and by taking into account the whole tumor volume or delineating the margins in an organ in the absence of a target lesion. Interestingly, TA approaches can also be employed for morphological images (such as unenhanced CT images or T2-weighted MR images), possibly reducing the need for more complex, expensive and time-consuming techniques. Additionally, filtering techniques can be applied to the original images before performing TA to widen the range of available quantitative parameters[126]. Encouraging results have been recently published for TA in the field of oncologic imaging[127,128]. Regarding CRC, the application of TA to CT, MRI and PET/CT images has been investigated and might be useful in different clinical settings for characterization, staging, prognosis and treatment planning.

Primary tumor identification: The accurate differentiation of colorectal nonneoplastic (i.e., hyperplasic polyps) and neoplastic lesions (i.e., adenomas and adenocarcinomas) based on computed tomography colonography (CTC) for mucosal colorectal lesions is mandatory for appropriate patient management[129]. The lesion size is correlated with the risk of malignancy, but size alone is not sufficient to discriminate between nonneoplastic and neoplastic lesions for the following reasons: (1) CTC tends to underestimate polyp size[130]; and (2) The overlap in the sizes of benign, premalignant and malignant lesions. Moreover, combination of metabolic and morphological information does not seem to increase the accuracy of CTC[41]. Therefore, TA might improve the diagnostic performance of CTC by introducing additional criteria for evaluation. Song et al[131] evaluated the accuracy of the use of CTC texture features in differentiating colorectal lesions. Intensity, gradient (i.e., the degree of the intensity change) and curvature (i.e., the degree that a geometric object deviates from being flat) were calculated for each colorectal polyp lesion. The results showed that the combination of gradient and curvature features significantly improved the performance of CTC in differentiating hyperplasic polyps from neoplastic lesions. The skewness and entropy values calculated on the basis of ADC maps were significantly lower in patients with stage pT1-2 tumors versus those with stage pT3-4 tumors[132]. Kurtosis values obtained on the basis of DWI were significantly higher in high-grade than in low-grade RC[133].

Lymph node involvement: The evaluation of the structural heterogeneity of loco-regional lymph nodes by using TA could help predict nodal status in RC to reliably differentiate malignant lymph nodes from benign lymph nodes. In this regard, Cui et al[134] reported that the heterogeneity of benign mesorectal nodes calculated by using enhanced CT images was significantly lower than that of malignant nodes when the short-axis diameter was 3–10 mm. However, no difference was observed between benign and malignant lymph nodes less than 3 mm and larger than 10 mm. Liu et al[132] reported that entropy values calculated by using ADC maps were significantly higher in pN1-2 than in pN0 RC. Similarly, Zhu et al[133] reported significantly higher kurtosis values calculated by using DWI in pN1-2 compared to pN0 RC.

Response to treatment: Neoadjuvant CRT in RC: TA of MR images might identify biomarkers able to assess responses to CRT in patients with LARC[125,132,135-137]. Using T2 weighted images, De Cecco et al[135] found that pre-neoadjuvant CRT kurtosis was significantly decreased in pCR versus partial-responders or nonresponders. Similarly, using T2 weighted images, Shu et al[136] found that TA of a combination of pre- and early-treatment features could distinguish between responders and nonresponders. TA approaches based on advanced sequences such as DCE[137] and ADC maps[132] have also been proposed and have shown promising results.

CRLMs: early identification and responses to treatment: Liver colonization by CRC cells is considered to be a multiple step process that progresses from prometastatic hepatic reactions to micrometastases and finally generates macrometastases[138]. The liver prometastatic reaction produces a special microenvironment favoring liver colonization by tumor cells. This reaction begins in the early tumor stage with the release of cytokines and chemokines by hepatic sinusoidal endothelium and Kupffer cells in response to colon cancer soluble factors and circulating cells. Cytokines and chemokines lead to the activation of perisinusoidal stellate cells and portal tract fibroblasts, which deposit extracellular matrix and create stromal support for cancer cells. The early preoperative identification of prometastatic hepatic reactions might facilitate the use of personalized treatment strategies that involve the selection of chemotherapy independently according to local staging[139]. Similarly, the preoperative identification of micrometastases in addition to visible liver metastases might indicate the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in CRC patients who are candidates for liver resection[140]. Conventional tomographic imaging is unable to detect liver prometastatic reactions or occult liver micrometastases. A few studies have tested the ability of TA to detect precocious hepatic alterations on the basis of the fact that the spatial heterogeneity of an apparently disease-free liver may be altered by liver prometastatic reactions and occult liver micrometastases.

Rao et al[140] assessed the capability of whole-liver portal phase CT TA to detect structural differences between apparently disease-free liver parenchyma in CRC patients without and with liver metastases. Disease-free liver parenchyma in patients with synchronous liver metastases (Group B) showed entropy values significantly higher and uniformity values significantly lower than those in patients without liver metastases (Group A). Furthermore, the disease-free liver parenchyma in patients who developed metachronous liver metastases within 18 months after primary staging CT (Group C) showed a subtle trend towards increased entropy and decreased uniformity values compared to that in patients in group A, although the difference was not significant. These results produced the following observations: (1) Group B presented greater heterogeneity in the liver parenchymal structure compared to group A due to the possible presence of micrometastases in the apparently disease-free remaining liver tissues or tumor-induced changes in liver perfusion; and (2) Group C may show ongoing tumor-induced, structural and/or hemodynamic changes in the liver parenchyma that precede morphological changes, allowing the identification of patients at risk of developing metachronous hepatic metastases.

Finally, both CT- and MRI-based TA parameters have been explored as feasible tools to predict treatment responses in patients with CRLMs[141,142]. Zhang et al[141] evaluated the response to chemotherapy of 193 unresectable liver metastases using dimensional reduction that was observed by the comparison of T2-weighted pretreatment and posttreatment MR images as a reference standard (a cutoff of a 30% decrease in the maximum diameter defined the responders). The authors found that the association of a first-order parameter (variance) and a higher-order parameter (angular second moment) had the ability to predict response, with an AUC of 0.814. Likewise, Ahn et al[142] demonstrated that decreased skewness values, obtained from two-dimensional ROIs used to annotate liver metastases on CT portal-phase images, were predictive of responses to chemotherapy (AUC = 0.797).

Prognosis: Ng et al[143] showed a correlation between the entire primary CRC heterogeneity according to portal venous CT images with the 5-year OS rate. CRC with decreased heterogeneity (decreased entropy, kurtosis and standard deviation of pixel distribution; increased uniformity and skewness) was associated with a decreased 5-year OS.

Miles et al[144] assessed the ability of the TA of hepatic portal phase CT images to predict survival in patients with CRC subject to surveillance for at least 24 months after tumor resection. Kaplan-Meier curves showed that increased uniformity was a significant predictor of survival. Finally, Lovinfosse et al[145] evaluated the TA of baseline 18FDG-PET/CT in LARC patients and concluded that increased coarseness values may be indicative of worse outcomes.

Volumetry

CT, MRI and PET hybrid imaging allow the “in vivo” calculation of neoplastic volume. RC tumor burden is correlated with disease stage and represents an important prognostic feature in terms of the prediction of treatment response, OS and PFS after CRT[146-149]. The tumor volume reduction rate has been reported to be superior to RECIST criteria for the prediction of the pathological responses of RC to neoadjuvant CRT[150].

The determination of tumor volumetry by using morphological CT and MR images requires the delineation of the neoplastic contours, which can be defined visually by manually tracing the presumed lesion boundary in each image containing the neoplasm. The volumes of the lesions are calculated by adding each of the 2D volumes (multiplying the 2D area by image thickness) of the entire lesion. The following considerations can explain the limits of this qualitative visual approach for tumor volumetry measurement: (1) Inflammatory peritumoral reactions can hamper the exact delineation of the interface between the tumor and the surrounding tissues; and (2) The difficulty in distinguishing between therapy-induced fibrosis and the residual viable tumor can also be problematic. A quantitative parametric analysis of images has also been proposed to solve this problem of tumor volumetry measurement.

T2-weighted signal intensity-selected volumetry of post-CRT MRI performed better than visual qualitative T2 volumetry in predicting pCR in patients with LARC[151]. Posttreatment total lesion diffusion (TLD = total DWI tumor volume x mean volumetric ADC) was better correlated than the total DWI tumor volume with histopathological tumor responses after CRT in patients with LARC[152].

LIMITATIONS AND POTENTIAL EFFECTIVE CLINICAL APPLICATIONS OF PARAMETRIC IMAGING ANALYSIS

DWI with ADC maps

Well-defined cut-off values are needed to use ADC maps in routine clinical practice. The ADC value thresholds used for differentiating normal and pathological tissue, assessing responses to therapy and defining prognosis have not yet been established for CRC. The lack of definite thresholds may be attributed to the following: (1) ADC values depend on the scanner and the acquisition protocol used and the clinical setting; (2) ADC values are subject to measuring errors due to the low spatial resolution of DWI images; and (3) The lack of reproducibility for ADC measurements. ADC values appear to be particularly promising for the prediction and assessment of RC responses to neoadjuvant CRT.

Perfusion imaging

The following general principles concerning angiogenesis and CRC have been established: More poorly perfused tumors usually lead to a poorer outcome; baseline perfusion is significantly higher in responders than in nonresponders to several types of therapies; and an early reduction in vascular parameters after therapy is usually associated with improved patient outcome[22]. The use of PI techniques has not yet been introduced in routine clinical practice, probably due to the numerous different technical approaches required and the complexity of parameter measurement. The following limitations of PI have to be considered: (1) The quantification of contrast agent concentrations is challenging because of the complex relationship between density (CT) or signal (MRI) and the contrast medium concentration, which is dependent on many factors, including the contrast agent dose, rate of injection, time of circulation, machine parameters, and, for MRI, native tissue relaxation rates and imaging sequence; (2) The different models used for the analysis of DCE imaging data and the calculation of quantitative perfusion parameters[153] may influence the measurement of quantitative perfusion parameters[35]; and (3) Tumor ROI analysis with current DCE imaging software platforms utilizes the mean quantitative vascular parameters, which do not reflect the spatial heterogeneity of perfusion[154]. Because of the large variety of potential indicators that could be used as imaging biomarkers, PI still needs further study to be recognized as an effective diagnostic tool in routine clinical practice. Among all the potential clinical applications of DCE imaging for CRC, the assessment and prediction of responses to antiangiogenic agents appears to be the most promising.

Hybrid imaging

18FDG-PET/CT quantitative parameters have added value for routine clinical practice. The following topics may benefit from a quantitative approach: The improvement of the detection of regional lymph node metastases; the prediction and assessment of RC responses to neoadjuvant CRT; the detection of tumor recurrence after surgery in combination with serum CEA levels. There is not enough scientific evidence to recommend the routine use of quantitative 18FDG-PET/CT for the identification and/or local staging of primary CRC because PET has the following limitations: (1) FDG uptake depends on several features, including tumor grade, the type of tumor involvement, histological type (e.g., FDG is limited in the evaluation of mucinous tumors); and (2) Limited spatial resolution, which may cause small lesions to be missed.

Texture analysis

Texture analysis mainly suffers from the following limitations: (1) The biological correlations of TA measurements have not been established definitively; and (2) The image acquisition parameters (for CT: Tube voltage, tube current, collimation; for MRI: features of the sequences) and TA processing (unfiltered or filtered at a fine, medium or coarse scale; TA calculation of single axial sections or whole target volumes; the use of semiautomated and automated systems to delineate tumor regions or volumes) may affect the measurement of TA parameters and may change their biological correlation. TA represents an ongoing topic of investigation, but the clinical effectiveness of the technique still has to be defined in different clinical settings relevant to CRC.

THE NEXT STEPS: MULTI-PARAMETRIC IMAGING ASSESSMENT, RADIOMICS AND RADIOGENOMICS, AND MACHINE LEARNING

The complexity of tumor biology cannot be described by a single morphological, functional and/or molecular parameter. An integrated approach utilizing noninvasive in vivo imaging techniques can be used to accurately represent neoplastic heterogeneity. A more comprehensive multiparametric assessment of tumor biology can be obtained from a single examination combining morphological, functional and/or molecular information by using hybrid devices such as PET/CT or PET/MRI. A few studies have investigated the relationships between functional and molecular parameters in CRC. An inverse relationship between tumor vascularization (expressed as the Kep value) and metabolism (expressed as SUVmax) was observed in CRLMs[155]. CRCs with a low-flow and high-metabolism phenotype were associated with increased levels of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1a), suggesting that flow and metabolism mismatch may represent an adaptative angiogenic response to hypoxia[156]. Highly perfused RC manifested with higher FDG uptake levels than low-perfusion tumors, suggesting that tumor growth is accompanied by an intense inflammatory reaction rather than the development of necrosis[157]. A significant negative correlation between the ADC and SUV values was reported for adenocarcinomas of the rectum, suggesting that the vital cellular burden is associated with increased metabolism[158,159]. The decrease in flow and metabolism (expressed as BF x SUVmax) showed high accuracy in the prediction of histopathological responses to radiation therapy and chemotherapy when using a cutoff value of -75% in patients with RC[159]. Multiparametric quantitative assessment appears to be a promising strategy for CRC management; however, its role in the different clinical settings associated with CRC must still be defined.

Further prospective investigations are needed to evaluate the clinical effectiveness of multiparametric imaging and to propose its routine clinical use in CRC settings.

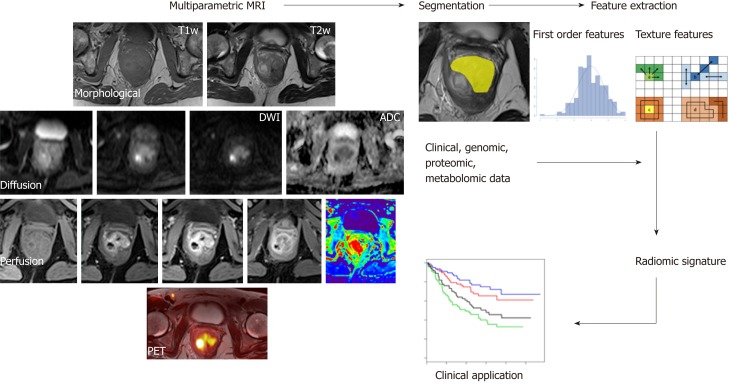

Radiomics has recently emerged as a promising tool for discovering new imaging biomarkers by extracting and analyzing numerous quantitative image features representative of tumor heterogeneity and phenotype. Radiomics combines the imaging of quantitative biomarkers with clinical reports and laboratory test values in a statistical model (Figure 5). Similarly, radiogenomics evaluates the relationship between radiomics and gene-expression patterns or transcriptomic and/or proteomic data to generate a statistical model. These advanced computational techniques can be applied to any type of clinical image, such as CT, MRI or hybrid PET images, and they can be used in a variety of clinical settings for diagnosis, the prediction of prognosis, and the evaluation of treatment response[160,161]. Although there is still a limited amount of evidence regarding the applications of radiogenomics to CRC, it retains tremendous potential[162]. Indeed, studies conducted using images from different modalities (mainly PET/CT) have investigated the relationship between radiomic data and K-ras gene mutations in CRC patients with encouraging results[163-165]. The K-ras gene mutation is an independent prognostic factor for survival and a negative predictive marker of tumor responses to drugs that target anti-epidermal growth factor receptors (EGFRs). Shin et al[163] reported that the frequency of K-ras mutations was higher in polypoid tumors with a larger axial to longitudinal dimension ratio. Using an animal model, Miles et al[166] reported that the combined multiparametric assessment of 18F-FDG uptake (expressed as SUVmax), CT texture (expressed as the mean value of tumor pixels with positive values) and perfusion (expressed as BF) has excellent accuracy (90.1%) in the identification of CRCs with K-ras mutations.

Figure 5.

A typical radiomics workflow consists of several steps. After image acquisition, segmentation is performed to define the tumor region. From this region, several features are extracted based on the intensity histogram and texture analysis. Finally, these features are assessed for their prognostic power or are linked with the stage or gene expression.

The increasing use of quantitative imaging data in clinical practice will require the use of automated and intelligent systems for analyzing a large amount of numerical information. Artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches can be helpful for the evaluation of radiomic and radiogenomic features. Deep learning convolutional neural networks can perform texture analysis and training with large amounts of data to create predictive algorithms.

CONCLUSION

The interpretation of medical tomographic images can no longer treat images strictly as pictures but instead must use innovative approaches based on numerical analysis. PA allows the extraction and analysis of the large amount of numerical data hidden in tomographic images. This information must be correlated with genetic, histological, clinical, prognostic and/or predictive data. The transition from purely anatomical tomographic imaging to quantitative tomographic imaging can also benefit the diagnostic management of CRC. However, to be of practical value and to have a real effect on clinical CRC diagnostic management, quantitative imaging approaches require the following: (1) The standardization of technical features to ensure the acquisition of good quality data and the development of robust techniques for analysis to assure reproducibility among different operators, scanners and centers; (2) Well-defined cut-off values for each proposed parameter measure in different clinical settings relevant to CRC; (3) A clear definition of the clinical significance of each numerical parameter as a single measure or a multiparametric combination; and (4) A real added-value when used to determine the known clinical and pathological factors of each new numerical imaging biomarker.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: No potential conflicts of interest. No financial support.

Peer-review started: June 20, 2019

First decision: July 22, 2019

Article in press: August 24, 2019

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Italy

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Caputo D, Gavriilidis P, Jeong KY, Tchilikidi KY S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: A E-Editor: Ma YJ

Contributor Information

Pier Paolo Mainenti, Institute of Biostructures and Bioimaging of the National Council of Research (CNR), Naples 80145, Italy. pierpamainenti@hotmail.com.

Arnaldo Stanzione, University of Naples "Federico II", Department of Advanced Biomedical Sciences, Naples 80131, Italy.

Salvatore Guarino, University of Naples "Federico II", Department of Advanced Biomedical Sciences, Naples 80131, Italy.

Valeria Romeo, University of Naples "Federico II", Department of Advanced Biomedical Sciences, Naples 80131, Italy.

Lorenzo Ugga, University of Naples "Federico II", Department of Advanced Biomedical Sciences, Naples 80131, Italy.

Federica Romano, University of Naples "Federico II", Department of Advanced Biomedical Sciences, Naples 80131, Italy.

Giovanni Storto, IRCCS-CROB, Referral Cancer Center of Basilicata, Rionero in Vulture 85028, Italy.

Simone Maurea, University of Naples "Federico II", Department of Advanced Biomedical Sciences, Naples 80131, Italy.

Arturo Brunetti, University of Naples "Federico II", Department of Advanced Biomedical Sciences, Naples 80131, Italy.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:7–34. doi: 10.3322/caac.21551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yuan Y, Li MD, Hu HG, Dong CX, Chen JQ, Li XF, Li JJ, Shen H. Prognostic and survival analysis of 837 Chinese colorectal cancer patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:2650–2659. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i17.2650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Labianca R, Nordlinger B, Beretta GD, Mosconi S, Mandalà M, Cervantes A, Arnold D ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Early colon cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2013;24 Suppl 6:vi64–vi72. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glynne-Jones R, Wyrwicz L, Tiret E, Brown G, Rödel C, Cervantes A, Arnold D ESMO Guidelines Committee. Rectal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:iv263. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Cutsem E, Cervantes A, Nordlinger B, Arnold D ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Metastatic colorectal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2014;25 Suppl 3:iii1–iii9. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerlinger M, Rowan AJ, Horswell S, Math M, Larkin J, Endesfelder D, Gronroos E, Martinez P, Matthews N, Stewart A, Tarpey P, Varela I, Phillimore B, Begum S, McDonald NQ, Butler A, Jones D, Raine K, Latimer C, Santos CR, Nohadani M, Eklund AC, Spencer-Dene B, Clark G, Pickering L, Stamp G, Gore M, Szallasi Z, Downward J, Futreal PA, Swanton C. Intratumor heterogeneity and branched evolution revealed by multiregion sequencing. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:883–892. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glüer CC, Barkmann R, Hahn HK, Majumdar S, Eckstein F, Nickelsen TN, Bolte H, Dicken V, Heller M. [Parametric biomedical imaging--what defines the quality of quantitative radiological approaches?] Rofo. 2006;178:1187–1201. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-926973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.García-Figueiras R, Baleato-González S, Padhani AR, Marhuenda A, Luna A, Alcalá L, Carballo-Castro A, Álvarez-Castro A. Advanced imaging of colorectal cancer: From anatomy to molecular imaging. Insights Imaging. 2016;7:285–309. doi: 10.1007/s13244-016-0465-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prezzi D, Goh V. Rectal Cancer Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Imaging Beyond Morphology. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2016;28:83–92. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2015.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chun YS, Vauthey JN, Boonsirikamchai P, Maru DM, Kopetz S, Palavecino M, Curley SA, Abdalla EK, Kaur H, Charnsangavej C, Loyer EM. Association of computed tomography morphologic criteria with pathologic response and survival in patients treated with bevacizumab for colorectal liver metastases. JAMA. 2009;302:2338–2344. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi H, Charnsangavej C, Faria SC, Macapinlac HA, Burgess MA, Patel SR, Chen LL, Podoloff DA, Benjamin RS. Correlation of computed tomography and positron emission tomography in patients with metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor treated at a single institution with imatinib mesylate: proposal of new computed tomography response criteria. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1753–1759. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.3049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lencioni R, Llovet JM. Modified RECIST (mRECIST) assessment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2010;30:52–60. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1247132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rao SX, Lambregts DM, Schnerr RS, Beckers RC, Maas M, Albarello F, Riedl RG, Dejong CH, Martens MH, Heijnen LA, Backes WH, Beets GL, Zeng MS, Beets-Tan RG. CT texture analysis in colorectal liver metastases: A better way than size and volume measurements to assess response to chemotherapy? United European Gastroenterol J. 2016;4:257–263. doi: 10.1177/2050640615601603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shankar S, Dundamadappa SK, Karam AR, Stay RM, van Sonnenberg E. Imaging of gastrointestinal stromal tumors before and after imatinib mesylate therapy. Acta Radiol. 2009;50:837–844. doi: 10.1080/02841850903059423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chung WS, Park MS, Shin SJ, Baek SE, Kim YE, Choi JY, Kim MJ. Response evaluation in patients with colorectal liver metastases: RECIST version 1.1 versus modified CT criteria. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199:809–815. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.7910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patterson DM, Padhani AR, Collins DJ. Technology insight: water diffusion MRI--a potential new biomarker of response to cancer therapy. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2008;5:220–233. doi: 10.1038/ncponc1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.deSouza NM, Riches SF, Vanas NJ, Morgan VA, Ashley SA, Fisher C, Payne GS, Parker C. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging: a potential non-invasive marker of tumour aggressiveness in localized prostate cancer. Clin Radiol. 2008;63:774–782. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koh DM, Collins DJ. Diffusion-weighted MRI in the body: applications and challenges in oncology. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188:1622–1635. doi: 10.2214/AJR.06.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heijmen L, Verstappen MC, Ter Voert EE, Punt CJ, Oyen WJ, de Geus-Oei LF, Hermans JJ, Heerschap A, van Laarhoven HW. Tumour response prediction by diffusion-weighted MR imaging: ready for clinical use? Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2012;83:194–207. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2011.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rak J, Mitsuhashi Y, Bayko L, Filmus J, Shirasawa S, Sasazuki T, Kerbel RS. Mutant ras oncogenes upregulate VEGF/VPF expression: implications for induction and inhibition of tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 1995;55:4575–4580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goh V, Halligan S, Daley F, Wellsted DM, Guenther T, Bartram CI. Colorectal tumor vascularity: quantitative assessment with multidetector CT--do tumor perfusion measurements reflect angiogenesis? Radiology. 2008;249:510–517. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2492071365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goh V, Glynne-Jones R. Perfusion CT imaging of colorectal cancer. Br J Radiol. 2014;87:20130811. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20130811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Konerding MA, Fait E, Gaumann A. 3D microvascular architecture of pre-cancerous lesions and invasive carcinomas of the colon. Br J Cancer. 2001;84:1354–1362. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nelson DA, Tan TT, Rabson AB, Anderson D, Degenhardt K, White E. Hypoxia and defective apoptosis drive genomic instability and tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2095–2107. doi: 10.1101/gad.1204904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Connor JP, Tofts PS, Miles KA, Parkes LM, Thompson G, Jackson A. Dynamic contrast-enhanced imaging techniques: CT and MRI. Br J Radiol. 2011;84 Spec No 2:S112–S120. doi: 10.1259/bjr/55166688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]