Abstract

Severe acute pancreatitis (SAP) is a risk factor for candidemia. We report a case of candida endophthalmitis in a 67-year-old man who was admitted to a hospital due to SAP with poorly controlled diabetes. After treatment for SAP, he was diagnosed with candidemia and candida endophthalmitis. We chose appropriate antifungal agents based on the results of a bacterial culture test. After treatment, the disappearance of Candida albicans (C. albicans) from the blood stream was confirmed in blood cultures. In addition, exudative plaques consistent with a fungal infection disappeared. After a diagnosis of candidemia is made, it is important to administer appropriate antifungal therapy and perform frequent ophthalmologic examinations.

Keywords: candidemia, candida endophthalmitis, ocular candidiasis, severe acute pancreatitis

Introduction

Although severe acute pancreatitis (SAP) is a benign disease, the mortality rate remains high. Fungal infections are common in patients with infected pancreatic necrosis and pseudocysts. Fungal infections indicate patients with a high risk of mortality in the long term (1). Many articles have reported that most fungal infections occur late in the clinical course of acute pancreatitis (AP) and are associated with pancreatic fluid collection. There are few reports of fungal infection early in the clinical course. In this case report, a 67-year-old man with poorly controlled diabetes developed candidemia and candida endophthalmitis early in the clinical course of SAP. We suggest that it is important to detect the source of infection and implement appropriate approaches to eliminate fungal infections when SAP patients develop high fever.

Case Report

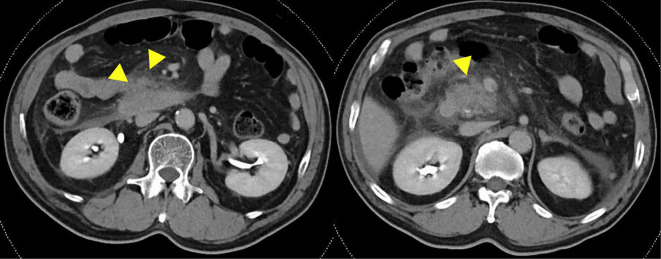

A 67-year-old man was hospitalized with SAP at a hospital near ours in June 2017. He was transferred to our hospital to receive treatment for SAP 3 days after his initial hospitalization. His past medical history included chronic pancreatitis and diabetes. He had consumed 5 liters of beer every day for 47 years. A physical examination conducted after his admission to our hospital revealed the following findings: body temperature, 36.6℃; blood pressure, 172/94 mmHg; heart rate, 96 beats/min; and respiratory rate, 21 breaths/min. His abdomen was hard and flat with tenderness and defensiveness. A blood test revealed an increased white blood cell count (WBC, 20,000 /μL) and increased serum concentrations of C-reactive protein (CRP, 31.03 mg/dL), amylase (280 IU/L), and lipase (254 U/L). Although he was undergoing insulin treatment at a nearby hospital, his HbA1c (National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program) level was 9.6% (Table 1). Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CE-CT) revealed low enhancement of the pancreatic parenchyma of the pancreas head with surrounding fluid collection (Fig. 1). Based on the criteria of the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, 2008 (2), the patient's prognostic factor score was 2 points (CRP, >15 mg/dL and SIRS), and his CE-CT grade was 2. Thus, we diagnosed the patient with SAP.

Table 1.

Laboratory Data on Admission.

| <Peripheral Blood> | <Biochemistry> | <Arterial blood test> | ||||||||||||||||

| WBC | 20,000 | /μL | TP | 5.8 | g/dL | Amy | 280 | IU/L | (room air) | |||||||||

| RBC | 439×104 | /μL | Alb | 3.0 | g/dL | P-Amy | 275 | IU/L | pH | 7.471 | ||||||||

| Hb | 14.4 | g/μL | T-bil | 1.2 | mg/dL | Lipase | 254 | U/L | pCO2 | 36.3 | mmHg | |||||||

| Ht | 41.50 | % | D-bil | 0.3 | mg/dL | Elastase-1 | 3,102 | ng/L | pO2 | 67.9 | mmHg | |||||||

| PLT | 15.1×104 | /μL | BUN | 6.2 | mg/dL | Na | 135.9 | mEq/L | BE | 2.7 | mEq/L | |||||||

| Cr | 0.55 | mg/dL | K | 3.8 | mEq/L | SpO2 | 93.30 | % | ||||||||||

| Ca | 8.0 | mg/dL | Cl | 96.8 | mEq/L | |||||||||||||

| AST | 18 | IU/L | CRP | 31.03 | mg/dL | |||||||||||||

| ALT | 19 | IU/L | HbA1c (NGSP) | 9.60 | % | |||||||||||||

| LDH | 217 | IU/L | β-D glucan | 19.8 | pg/mL | |||||||||||||

| ALP | 256 | IU/L | ||||||||||||||||

| γ-GTP | 55 | IU/L | ||||||||||||||||

| CK | 107 | IU/L | ||||||||||||||||

WBC: white blood cells, RBC: red blood cells, Hb: hemoglobin, Ht: hematocrit, PLT: platelet, TP: total protein, Alb: albumin, T-bil: total bilirubin, D-bil: direct bilirubin, Cr: creatinine, Ca: calcium, AST: aspartic aminotransferase, ALT: alanin aminotransferase, LDH: lactate dehydrogenase, ALP: alkaline Phosphatase, γ-GTP: γ-glutamyltransferase, CK: creatine kinase, Amy: amylase, HbA1c (NGSP): hemoglobin A1c (National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program)

Figure 1.

The contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CE-CT) findings on admission. These findings revealed low enhanced pancreatic parenchyma of the pancreas head with surrounding fluid collection.

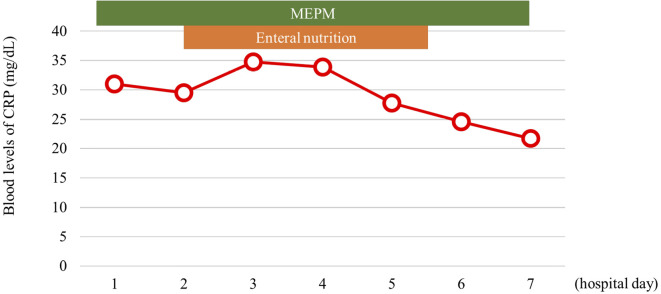

He received fluid resuscitation (100 mL/kg, daily), which was started at admission. He was treated with nafamostat mesylate (240 mg, daily) for 5 days and antibiotics (meropenem 1.5 g, daily) for 10 days. He stayed in the intensive care unit (ICU) for 12 days (Fig. 2). His abdominal pain and inflammation improved.

Figure 2.

The early clinical course of SAP. MEPM: meropenem

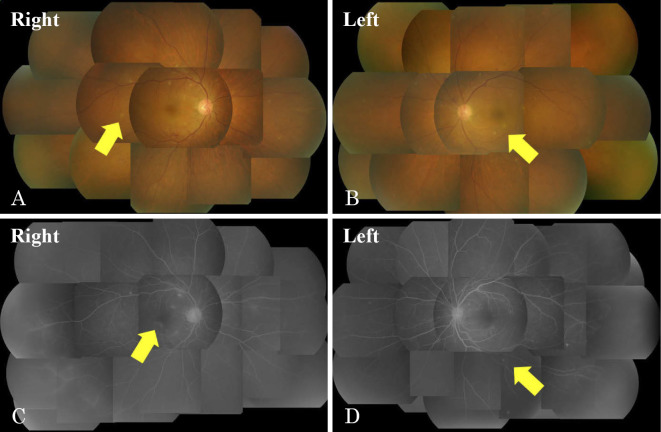

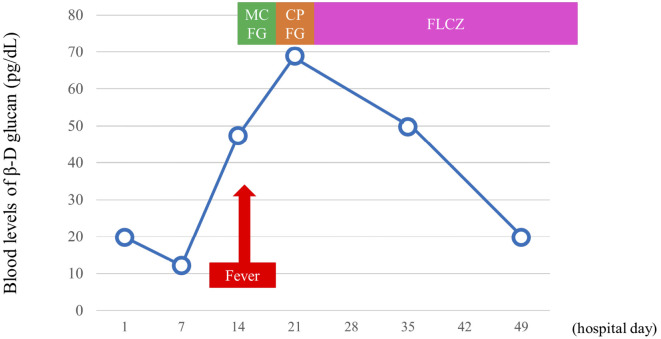

However, he developed a high fever 16 days after being hospitalized. The patient did not have a urinary tract infection, pneumonia or infected pancreatic fluid. Candida albicans (C. albicans) was detected in both blood and central venous catheter cultures. The blood level of β-D glucan obtained on the same day was 47.4 pg/mL. We diagnosed the patient with candidemia; thus, ophthalmologic examinations were performed. Exudative plaques consistent with a fungal infection were observed in both retinas after a fundoscopic examination (Fig. 3). He was diagnosed with candida endophthalmitis. Fortunately, he did not experience a visual disturbance. We chose appropriate antifungal agents based on the bacterial culture test results; micafungin (MCFG, 150, mg daily), caspofungin (CPFG, 75 mg, daily), and fluconazole (FLCZ, 800 mg, daily) were administered with intravenous fluids for 59 days (Table 2). The blood cultures were evaluated weekly, and the disappearance of C. albicans from the blood stream was confirmed. Exudative plaques consistent with a fungal infection disappeared after another fundoscopic examination. The blood levels of β-D glucan became negative (19.8 pg/mL) 50 days after hospitalization (Fig. 4). After receiving treatment for candidemia and candida endophthalmitis, he was discharged 95 days after hospitalization without any complications of AP.

Figure 3.

The fundoscopic and fluorescent fundoscopic findings. Exudative plaques consistent with a fungal infection were observed in both retinas. A, B: Fundoscopic findings. C, D: Fluorescent fundoscopic findings.

Table 2.

The Bacterial Culture Test for C. albicans.

| MIC (μg/mL) | ||

|---|---|---|

| AMPH-B | =0.5 | S |

| 5-FC | ≤0.125 | S |

| MCFG | ≤0.03 | S |

| VRCZ | ≤0.015 | S |

| MCZ | =0.125 | S |

| FLCZ | =0.25 | S |

| ITCZ | =0.125 | S |

MIC: minimum inhibitory concentration, AMPH-B: amphotericin, 5-FC: flucytosine, MCFG: micafunginin, VRCZ: voriconazole, MCZ: miconazole, FLCZ: fluconazole, ITCZ: Itraconazole

Figure 4.

Change in the blood levels of β-D glucan after admission. MCFG: micafunginin, CPFG: caspofungin, FLCZ: fluconazole

Discussion

Candidemia is a life-threatening infection that is associated with a high rate of mortality and an increased length of hospital stay. The risk factors for candidemia include the use of broad-spectrum antibacterial agents, the use of central venous catheters, receipt of parenteral nutrition, receipt of renal replacement therapy by ICU patients, neutropenia, the use of implantable prosthetic devices, and the receipt of immunosuppressive agents (including glucocorticosteroids, chemotherapeutic agents, and immunomodulators) (3).

In the present case, candidemia occurred at a relatively early phase, and a catheter Candida infection was also proven. It is thought that percutaneous or transcatheter catheter infection occurred and led to candidemia and endophthalmitis. Candidemia may occur from the gastrointestinal tract or due to catheter infection. Because candida is normally distributed throughout the gastrointestinal tract, invasive procedures increase the risk of candidemia (4). AP has been reported to be associated with increased gut mucosal permeability, predisposing patients to septic complications. The translocation of fungal flora from the gastrointestinal tract to extraintestinal sites plays an important role in the pathogenesis of fungal infections in patients with AP. Fungal infection is also said to be caused by microbial substitution due to the prolonged prophylactic administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics. SAP carries with it a high risk of fungal infection because the Japanese guidelines for the management of AP (Japanese Guidelines 2015: JPNGL2015) recommend the prophylactic administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics to patients with SAP and necrotizing pancreatitis, which may improve their prognosis if antibiotics are administered in the early phase of pancreatitis (within 72 hours of the onset) (5). Additionally, the median time from the onset of AP to the isolation of fungi is generally 7 weeks in pancreatic fluid (6). Thus, it is rare to isolate fungi early in the clinical course of AP.

In JPNGL 2015, the effect of the prophylactic administration of antifungal agents in patients with AP is not clear, and the routine administration of these agents is not recommended (5). De et al. reported that early treatment with fluconazole did not affect the length of hospital stay or mortality of patients with pancreatitis (7). Furthermore, Shorr et al. pointed out that the prophylactic administration of antifungal agents led to an increased frequency of infection with resistant strains of Candida (8).

Feman et al. reported that the incidence of ocular candidiasis in patients with candidemia was only 2% (9). Ocular candidiasis is divided into chorioretinitis and endophthalmitis. Chorioretinitis involves inflammation of the choroid and retina, while endophthalmitis involves inflammation of the vitreous body. The pathogenic pathway of candida endophthalmitis is as follows: candida reaches the choroid and retina through hematogenous spread and proliferates, causing retinal abscesses and subsequent vitreous involvement. Nagao et al. reported that C. albicans as the etiological agent (OR: 3.68, 95%CI: 1.11-12.2, p=0.034) and higher β-D glucan values (OR: 9.99, 95%CI: 2.60-21.3, p=0.001) were identified as statistically significant risk factors for ocular candidiasis in a multivariate analysis (10). Lingappan et al. reported that the incidence of retinal detachment in patients with fungal endophthalmitis was 29% (11). Some cases of fungal endophthalmitis may lead to blindness due to retinal detachment.

The primary recommended treatments for candida endophthalmitis are amphotericin (AMPH-B; 0.7-1 mg/kg) with flucytosine (5-FC; 25 mg/kg) every 6 hours, fluconazole (FLCZ; 6-12 mg/kg) daily, and surgical intervention for patients with severe endophthalmitis or vitreitis. Alternative therapy is recommended for patients intolerant of AMPH-B and 5-FC therapy and patients who experience or therapeutic failure with these treatments. The duration of therapy is at least 4-6 weeks, as determined by repeated examinations to verify the resolution. Diagnostic vitreal aspiration is recommended for patients with endophthalmitis of unknown origin (3).

There have been no reports of pancreatitis with candida endophthalmitis. In this case, the patient had multiple risks factors for candidemia. He used broad-spectrum antibacterial agents and central venous catheters and had stayed in the ICU for a long time. It is thought that the combination of his poorly controlled diabetes and central venous catheter infection led to the development of candidemia. We believe that the patient's candidiasis was triggered by a catheter infection, and that this was complicated by candida endophthalmitis through hematogenous spread. Generally, candidemia associated with pancreatitis occurs later in the clinical course because of microbial substitution and infected pancreatic fluid. In emergency treatment for diseases such as SAP, central venous catheters are often inserted. Candida endophthalmitis lacks initial symptoms and should be included in the differential diagnosis of patients with SAP in the early phase of the condition. It is recommended that a fundoscopic examination be quickly performed when candidemia and ocular symptoms are detected in the early phase of SAP.

When we encounter an infection of unknown etiology, we should consider the incidence of candidemia and whether the patients have any risk factors for candidemia. The administration of appropriate antifungal therapy and the frequent performance of ophthalmologic examinations are important for patients diagnosed with candidemia.

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

References

- 1. Reuken PA, Albig H, Rodel J, et al. . Fungal infections in patients with infected pancreatic necrosis and pseudocysts: risk factors and outcome. Pancreas 47: 92-98, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Takeda K, Yokoe M, Takada T, et al. . Assessment of severity of acute pancreatitis according to new prognostic factors and CT grading. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 17: 37-44, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes D, et al. . Clinical practice guidelines for the management of candidiasis: 2009 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 48: 503-535, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bae JH, SC Lee. Intravitreal liposomal amphotericin B for treatment of endogenous candida endophthalmitis. Jpn J Ophthalmol 59: 346-352, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mayumi T, Yoshida M, Isaji S, et al. . Japanese guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis: Japanese Guidelines 2015. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 22: 405-432, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Liu WC, Chan MC, Lin TY, Hsu CH, Chiu SK. Candida lipolytica candidemia as a rare infectious complication of acute pancreatitis: a case report and literature review. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 46: 393-396, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. De Waele JJ, Vogelaers D, Blot S, Colardyn F. Fungal infections in patients with severe acute pancreatitis and the use of prophylactic therapy. Clin Infect Dis 37: 208-213, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shorr AF, Chung K, Jackson WL, Waterman PE, Kollef MH. Fluconazole prophylaxis in critically ill surgical patients: a meta-analysis. Crit Care Med 33: 1928-1935, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Feman SS, Nichols JC, Chung SM, Theobald TA. Endophthalmitis in patients with disseminated fungal disease. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 100: 67-70, 2002. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nagao M, Saito T, Doi S, et al. . Clinical characteristics and risk factors of ocular candidiasis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 73: 149-152, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lingappan A, Wykoff CC, Albini TA, et al. . Endogenous fungal endophthalmitis: causative organisms, management strategies, and visual acuity outcomes. Am J Ophthalmol 153: 162-166, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]