Abstract

Retinoic acid (RA), an essential active metabolite of vitamin A, controls numerous physiological processes. In addition to the analytical challenges owing to its geometric isomers, low endogenous abundance, and often localized occurrence, nonspecific interferences observed during liquid chromatography (LC) multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) quantification methods have necessitated lengthy chromatography to obtain accurate quantification free of interferences. We report the development and validation of a fast high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) multiplexing multiple reaction monitoring cubed (MRM3) assay for selective and sensitive quantification of endogenous RA from complex matrices. The fast HPLC separation was achieved using an embedded amide C18 column packed with 2.7 μm fused-core particles which provided baseline resolution of endogenous RA isomers (all-trans-RA, 9-cis-RA, 13-cis-RA, and 9,13-di-cis-RA) and demonstrated significant improvements in chromatographic efficiency compared to porous particle stationary phases. Multiplexing technology further enhanced sample throughput by a factor of 2 by synchronizing parallel HPLC systems to a single mass spectrometer. The fast HPLC multiplexing MRM3 assay demonstrated enhanced selectivity for endogenous RA quantification in complex matrices and had comparable analytical performance to robust, validated LC-MRM methodology for RA quantification. The quantification of endogenous RA using the described assay was validated on a number of mouse tissues, nonhuman primate tissues, and human plasma samples. The combined integration of fast HPLC, MRM3, and multiplexing yields an analysis workflow for essential low-abundance endogenous metabolites that has enhanced selectivity in complex matrices and increased throughput that will be useful in efficiently interrogating the biological role of RA in larger study populations.

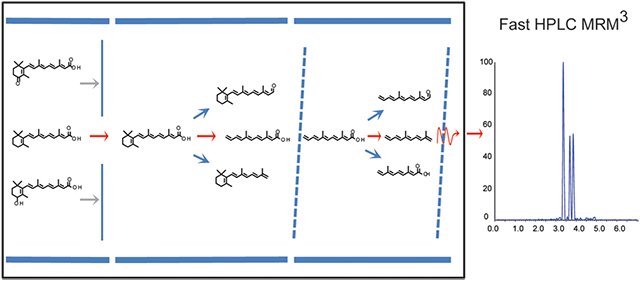

Graphical Abstract

Vitamin A is essential to numerous physiological processes including cell proliferation, differentiation, immune response, development, reproduction, cellular metabolism, and nervous system function.1-4 Metabolism activates vitamin A into retinoic acid (RA), a potent signaling molecule that controls gene transcription through activation of nuclear receptors and can also function via nongenomic mechanisms.5-8 The expression of retinoid-binding proteins, enzymes, and receptors that contribute to RA generation, catabolism, and signaling indicate that RA levels are spatially and temporally controlled to produce the individual actions of vitamin A.9-12 Whereas it has been shown that alteration of strictly controlled endogenous RA concentrations in vivo contributes to disease states via disruption of RA signaling that yields defects in function including cellular metabolism (type 2 diabetes, obesity), proliferation and differentiation (numerous forms of cancer), and cell signaling (immune disorders, inflammation, and fibrosis),13-17 many questions pertaining to the role of RA in retinoid biology remain. The ability to directly detect and quantify endogenous RA from circulation and/or tissue is essential to determining the mechanisms of disease and the role that disturbances in RA concentration play in physiological dysfunction.5,14,18-21

A variety of analytical techniques has been used to detect and quantify endogenous retinoids.19-28 Among these techniques, liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) has emerged as the most effective technique due to its combination of robustness, selectivity, and sensitivity. However, the analysis of RA remains technically challenging owing to its low endogenous abundance and it’s often localized occurrence.14,18-21,29 Additionally, there are several biologically occurring geometric isomers that have distinct biological actions (refer to Figure S1, Supporting Information, for structures of RA isomers).6,7,30-34 Geometric isomers, inherently isobaric, are an analytical challenge and must be separated chromatographically before mass spectrometry detection.19

LC-MS/MS has been used effectively to quantify RA in biological matrices using selected reaction monitoring (SRM) also termed multiple reaction monitoring (MRM).19-22 Typical MRM detection uses a tandem quadrupole mass spectrometer to select for an analyte’s unique precursor ion to product ion transition. Monitoring a unique precursor ion to product ion transition is the basis of quantitative mass spectrometry and imparts selectivity as detection requires an analyte to meet the precursor ion m/z condition, fragment under controlled conditions to form a characteristic product ion, and satisfy the product ion m/z condition in order to reach the detector. The main advantage of MRM is the elimination of background as most of the ions in a complex mixture do not satisfy the MRM m/z criteria yielding increases in sensitivity between 100- and 1000-fold for RA detection.20,35

Although, MRM detection typically has superior selectivity and sensitivity, some instances have been observed where abundant species in complex matrices that are coextracted and coeluted with the analyte of interest can still pose a challenge for quantification.36-38 Nonspecific signal can originate due to species of similar nominal mass that are present at abundance often several orders of magnitude greater than the analyte of interest yielding nonspecific interferences in MRM transitions.19,36-39 Current strategies to combat nonspecific interferences in MRM include using chromatographic separations to move interferences out of the analysis window and the inclusion of additional mass events. Whereas nonspecific interferences have been observed during RA detection and the impact of manipulating the chromatographic separation to move interfering species away from RA has been discussed, using multiple mass events or multistage MRM to remove interferences and impart selectivity has not been well-defined.39

The addition of a second consecutive m/z transition, to yield MS3 detection, increases selectivity by decreasing the likelihood that interfering species have a similar nominal mass as the ions in the multiple m/z transitions. Tandem quadrupole/linear ion trap hybrid mass spectrometers allow for multistage MRM by selecting and isolating the first generation precursor ion in the first quadrupole, producing the first generation product ions in the multipole collision cell (first generation product ions are the second generation precursor ions), and then selecting/isolating/fragmenting the unique second generation precursor ion in the linear ion trap (LIT) to produce second generation product ions from which a unique second generation product ion is then detected. The inclusion of a second consecutive m/z transition using a tandem quadrupole/linear ion trap hybrid mass spectrometer is a detection scheme that has also been termed multiple reaction monitoring cubed (MRM3).40 Tandem quadrupole/linear ion trap hybrid mass spectrometers are based upon the ion path of a tandem quadrupole instrument and can function in either MRM mode where the “final” quadrupole is a LIT operated in a normal RF/DC mode or in MRM3 mode where the “final” quadrupole functions as a LIT that traps ions which can be fragmented further and then ejected axially from the ion trap in a mass selective fashion.41 When operated in MRM3 mode, the LIT offers efficient ion trapping and the ability to perform MS3 or MRM3 detection with all the conventional performance features of a tandem quadrupole instrument.35,41-43 Whereas MRM3 has been applied to protein, peptide, and drug quantification,44-49 the utility of MRM3 for the quantification of endogenous metabolites and the ability of MRM3 to remove species present in complex biological matrices that interfere with endogenous metabolite detection has not been described. Here, we detail the use of fast high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) multiplexing MRM3 for rapid, sensitive, and selective quantification of RA isomers from complex matrices demonstrating the utility of fast HPLC multiplexing MRM3 for quantification of endogenous small molecules.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Materials.

All-trans-RA (atRA), 9-cis-RA (9cRA), 13-cis-RA (13cRA), and acitretin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). 9,13-di-cis-RA (9,13dcRA) was prepared as described.33 Acitretin was used as the internal standard. Optima LC/MS grade water (H2O), acetonitrile (ACN), and formic acid (FA) were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA).

Animal Plasma and Tissues.

Collection of mouse tissue, nonhuman primate (NHP) (Rhesus macques) tissue, and human plasma samples are described in the Supporting Information.

Extraction.

Retinoids were homogenized in saline and extracted from tissue by a two-step liquid–liquid extraction as described in detail previously.19-21

Liquid Chromatography (LC).

Two different gradients were developed to resolve RA and its isomers. A shorter gradient (gradient 1) was mainly used for cultured cells or subcellular fractions and a longer gradient (gradient 2) was used primarily for plasma and tissue samples. Both gradients were performed using a Shimadzu Prominence UFLC XR high-performance liquid chromatograph (HPLC) (Shimadzu, Columbia, MD). All separations were performed using an Ascentis Express RP-Amide guard cartridge column (Supelco, 50 × 2.1 mm, 2.7 μm) coupled to an Ascentis Express RP-Amide analytical column (Supelco, 100 × 2.1 mm, 2.7 μm). Mobile phase A consisted of 0.1% formic acid in water, and mobile phase B consisted of 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile. Refer to the Supporting Information for a description of gradients and LC operating parameters.

Mass Spectrometry (MS).

Data were acquired with an AB Sciex QTRAP 5500 hybrid tandem quadrupole/linear ion trap mass spectrometer (AB Sciex, Framingham, MA). Gas-phase ionization was achieved using atmospheric pressure chemical ionization (APCI) operated in the positive ion mode. The instrument was controlled by Analyst v1.6 software and operated in multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode or in multistage MRM mode (MRM3). The MRM transition for RA was m/z 301.2 → m/z 205.1 and for acitretin was m/z 327.2 → m/z 159.1. The MRM3 transition for RA was m/z 301.1 → m/z 205.1 → m/z 159.1 and for acitretin was m/z 327.2 → m/z 159.1 → m/z 129.1. The MRM and MRM3 APCI and mass spectrometry parameters are described in the Supporting Information. At present, MRM3 is only compatible with AB Sciex’s QTRAP configuration.

Multiplexing.

An integrated multiplex LC-MS system was used consisting of an AB Sciex QTRAP 5500 hybrid tandem quadrupole/linear ion trap mass spectrometer, two Shimadzu Prominence UFLC XR HPLC systems, a pump containing a four solvent selection valve for sample loading, and three switching valves for flow path control. The two chromatographic systems shared a single high pressure loading pump. All hardware modules were controlled by Analyst v1.6 software with the MPX driver 1.0 add-on. Further details on the MPX software are described in the Supporting Information.

High Resolution Mass Spectrometry (HRMS).

Samples were analyzed by electrospray ionization in positive ion mode on a benchtop quadrupole-orbitrap mass spectrometer (Q Exactive; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany). Refer to the Supporting Information on experimental parameters for HRMS data acquisition, empirical formula calculations, and product ion structural determination.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Mass Spectrometry.

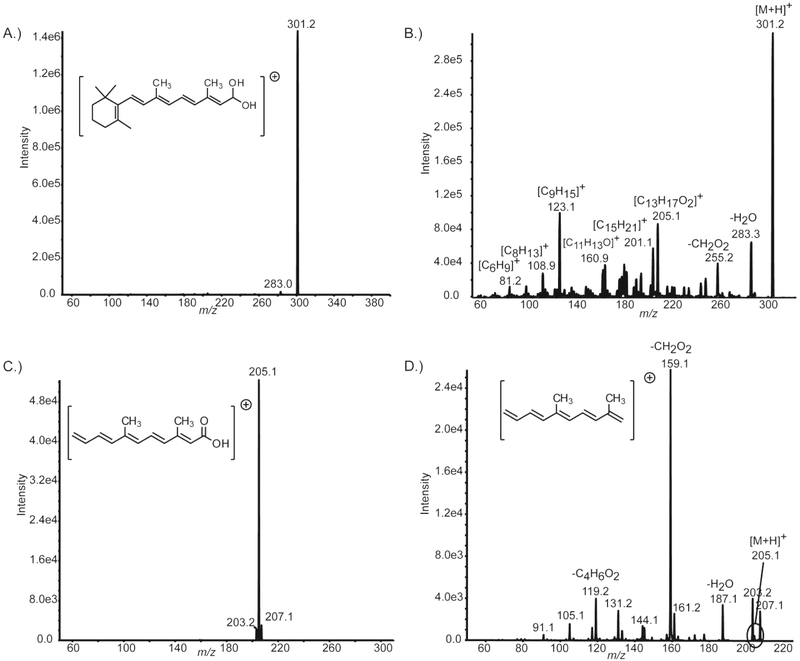

Gas-phase ionization of RA has been accomplished using positive and negative ion modes for both electrospray ionization (ESI) and atmospheric pressure chemical ionization (APCI). APCI and ESI mass spectra displayed comparable full scan (MS1) and tandem (MS2) mass spectra (Figure 1 and Figure S2, Supporting Information).19-21 Positive ion mode APCI offered several advantages including greater ionization efficiency, better sensitivity, larger dynamic range, and reduced sensitivity to ion suppression in complex matrices.19-22 RA detection and quantification has been reported previously using APCI in positive ionization mode where the favorable ionization efficiency has been attributed to RA’s chemical structure (i.e., conjugated structure and carboxylic acid functional group).21 APCI of RA provided robust protonated precursor ion signal at m/z 301.2 ([M + H]+) as shown in Figure 1A.

Figure 1.

APCI positive ion mode mass spectra of atRA. (A) First generation precursor ion mass spectrum of atRA [M + H]+ at m/z value 301.2. Inset displays atRA structure. (B) First generation product ion mass spectrum of m/z 301.2. Neutral loss or empirical formula is designated for most prominent product ions. (C) Second generation precursor ion mass spectrum of m/z value 205.1. Inset displays the proposed structure for product ion at m/z 205.1. (D) Second generation product ion mass spectrum of m/z 205.1. Neutral loss is designated for most prominent product ions. Inset displays proposed structure for product ion at m/z 159.1.

The MRM transition of m/z 301.2 → 205.1 was characteristic of RA and yielded the greatest signal-to-noise ratio in biological samples as seen herein and detailed in previous reports.19-22 The MRM m/z 301.2 → 205.1 transition has been demonstrated to be highly sensitive (limit of detection (LOD) at 62.5 attomol) and have a dynamic linear range of 4 orders of magnitude (250 attomol to 10 pmol) for direct quantification of RA.20 Despite the obvious utility of MRM detection of RA, some complex matrices have been documented to present analytical challenges in the form of nonspecific interfering signal during MRM detection of RA.39 Chromatographic resolution of interfering species has proven effective but often results in longer chromatographic run times.19-21,39 Here, we incorporated multistage MRM to enhance the selectivity of RA detection.

The MS3 mass spectrum for the second generation precursor ion at m/z 205.1 (m/z 301.2 → 205.1) displayed several abundant product ions (Figure 1D). The product ion at m/z was chosen as the second generation product ion for MRM3 method development and validation based on its abundance and characteristic formic acid neutral loss. As such, the MRM3 transition found to have the highest signal-to-noise ratio and greatest specificity was m/z 301.2 → 201.1 → 159.1. In order to fully characterize the unique product ions produced by the gas-phase dissociation of RA that were used in the multistage MRM detection scheme, we used a combination of low-resolution and high-resolution tandem mass spectrometry (Figure 1 and Figure S2, Supporting Information). The structural identity of the m/z 205.1 product ion has not been reported to date. The proposed structure and gas-phase fragmentation mechanism of the product ion at m/z 205.1 is presented in Figure 1C, Figure S3, and Table S1, Supporting Information. Similarly, the proposed structure for the product ion at m/z 159.1 (the second generation product ion in the MRM3 scheme) and gas-phase fragmentation mechanism are displayed in Figure 1D, Figure S4, and Table S2, Supporting Information. Refer to the Supporting Information for details on structure elucidation.

Liquid Chromatography.

Endogenous RA isomers with distinct biological actions have been reported and must be resolved to achieve accurate quantification.5,11,14,18-29,32-34 Numerous liquid chromatographic separations have been reported for RA using a variety of column chemistries, solvent compositions, and gradient profiles to achieve varying degrees of separation efficiency.19-28,33,34 Insufficient chromatographic separation of these endogenous isomers can lead to coelution of the individual isomer species thereby confounding identification, quantification, and ultimately, the elucidation of their respective molecular mechanisms. For example, atRA binds retinoic acid receptor (RAR) with high affinity but exhibits little affinity toward retinoid X receptor (RXR).6,7,10,30,31 Conversely, 9cRA has been postulated to bind uniquely to both RXR and RaR.6,7,10,30,31 13cRA and 9,13cRA do not bind efficiently to RAR or RXR. It is therefore important to be able to detect and quantify each endogenous isomer individually with high accuracy and precision in order to interrogate their respective contributions to biological action.

The use of HPLC for separation of RA isomers preceding MRM detection using an embedded polar group C18 stationary phase has been reported previously for cultured cells/subcellular fractions and tissue samples that had analytical run times of 12 and 25 min, respectively.20 We sought to reduce these analytical run times in order to increase throughput by employing a fast HPLC separation using fused-core particles with the same embedded polar group C18 stationary phase. In comparison to traditional C18 column chemistry, the embedded amide group used here provided superior retention and selectivity for acids due to enhanced hydrogen bonding between the embedded amide carbonyl group, which is a hydrogen bond acceptor, and the carboxylic acid group of RA, which is a hydrogen bond donor. This interaction between RA and the embedded amide group stationary phase facilitated the separation of RA isomers. The 2.7 μm fused-core particles consisted of a 1.7 μm solid silica core covered in a 0.5 μm porous shell. Fused-core particles that have a nonporous core and a superficial porous layer provide greater speed and approximately twice the efficiency of traditional fully porous particles due to a reduced diffusion path length provided by the porous shell stationary phase.50 Additionally, the 2.7 μm fused-core particles provide comparable chromatographic efficiency to sub-2 μm particles at half the back pressure which allows the use of conventional HPLC pumps.50,51

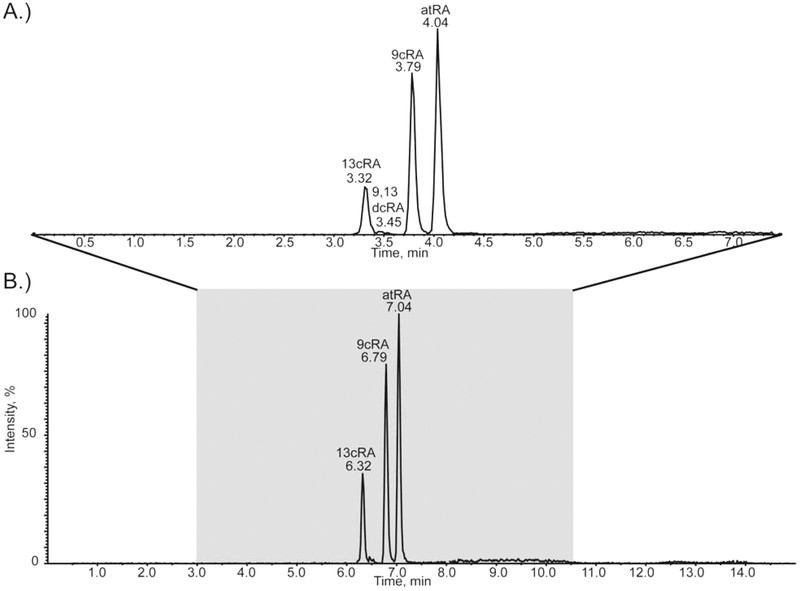

We developed two gradients that resolved RA isomers: atRA, 9cRA, 13cRA, and 9,13dcRA. Gradient 1, developed for cultured cell/subcellular fractions, had a 6.3 min chromatographic run time (Figure S5, Supporting Information). Gradient 2, developed for plasma and tissue protocols, had a 15 min chromatographic run time (Figure 2). The longer 15 min run time of the plasma/tissue method allowed for an extended gradient which yielded greater resolution (Rs) of RA isomers than the cultured cell/subcellular fraction method, Rs of 1.3 vs 1.0, respectively, for Rs between atRA and 9cRA This increased resolution was useful in terms of producing better quality data from complex plasma and tissue matrices. Refer to Figure S6, Supporting Information, for an example chromatogram of atRA detection plus internal standard (acitretin) from human plasma using gradient 2. Please note, the total chromatographic run cycle time described for gradients 1 and 2 was different than the actual acquisition time for collection of the multiplexed MRM3 data as shown according to the shaded area in Figure 2 and Figure S5, Supporting Information, and explained in detail in the following section. Table S3, Supporting Information, summarizes the improvement in column performance in regards to separation of RA isomers with fused-core silica particles as compared to traditional porous particles. Retention time (tR) of atRA was reduced to 3.5 and 6.7 min, respectively, for gradient 1 (cell) and gradient 2 (plasma/tissue) allowing for shorter run times. Height equivalent to theoretical plate (HETP) was reduced by 25.3% and 47.1%, and number of theoretical plates (N) was increased by 24.6% and 15.4% with the fused-core particle stationary phase as compared to the porous particle stationary phase for both gradient 1 and gradient 2, respectively. Chromatographic efficiency, as described by N/m (N per meter), was increased for both gradient 1 (cell) and gradient 2 (plasma/tissue) with fused-core particles as compared to porous particles with N/m values of 228 000 and 328 000, respectively. Typically, sub-2 μm particle columns used in UHPLC separations achieve N/m of >200 000 indicating that our fast HPLC separation achieved comparable chromatographic efficiency at much lower backpressures (<4000 psi). A recent report by Arnold et al.52 used a similar fused-core embedded polar group column for RA isomer separation in a UHPLC-MS/MS method for human plasma analysis reporting a tR of approximately 14 min for atRA and a run time of 20 min (excluding column equilibration time which was not specified).52 Although a detailed evaluation of chromatographic performance was not included in this report, the work by Arnold et al.52 supported the effectiveness of the embedded amide group C18 stationary phase for separation of endogenous RA isomers.

Figure 2.

MRM3 chromatogram using fast HPLC multiplexing. Gradient 2, multiplexing acquisition window was set to 7.5 min (A) and total chromatographic run time was 15 min (B). The tR for 13cRA, 9,13-dcRA, 9cRA, and atRA are indicated. The shaded portion of the total chromatographic run time corresponds to the mass spectrometry acquisition window for HPLC multiplexing.

Fast HPLC Multiplexing.

In addition to optimizing HPLC parameters for greater chromatographic efficiency and decreased run time, the introduction of multiplexing technology can greatly enhance sample throughput by synchronizing parallel HPLC systems to a single MS detector via precise timing of switching valves and a shared loading pump.53-55 In this format, each HPLC stream is uniquely timed to perform alternate injections and HPLC gradient elutions where switching valves divert the HPLC stream to waste or to the mass spectrometer. This integrated approach enabled maximum utilization of the mass spectrometer by precisely timing acquisition windows for each HPLC stream to cover only the HPLC window of interest which effectively doubled sample throughput.

Multiplexing was achieved through the use of AB Sciex’s MPX-1 driver add-on software. The MPX software interface controlled both HPLC systems and dictated MS acquisition windows. For example, the acquisition window for Gradient 2, which had a 15 min chromatographic run time, was set to 7.5 min bracketing the elution of the RA isomers (Figure 2). By adjusting the MS acquisition window to 7.5 min, the time the mass spectrometer spent collecting data was reduced in half for the chromatographic run time. The second HPLC stream performed the exact same chromatographic separation and MS acquisition but was synchronized to be offset from stream 1 such that the MS acquisition of stream 2 began when the MS acquisition of stream 1 was completed. The same MPX method programming was adopted for the Gradient 1 (Figure S5, Supporting Information). In both cases, HPLC multiplexing increased sample throughput by a factor of 2 and resulted in net analytical run times of 3.2 and 7.5 min for gradient 1 and gradient 2, respectively.

Analytical Performance.

The fast HPLC MRM3 assay for RA detection and quantification was assessed for sensitivity, linearity, accuracy, and precision. Assay sensitivity was assessed by determining the limit of detection (LOD) and limit of quantitation (LOQ). The LOD, defined as a signal-to-noise ratio of 3, and the LOQ, defined as a signal-to-noise ratio of 10, were determined for both gradient 1 and gradient 2. The LOD was 70.0 attomol (0.070 fmol) and LOQ was 265 attomol (0.265 fmol) for atRA from gradient 1. The LOD was 135 attomol (0.135 fmol) and LOQ was 825 attomol (0.825 fmol) for atRA from gradient 2. Refer to Figure S7, Supporting Information, for an example chromatogram at the LOQ for atRA. The LOD and LOQ values determined herein were highly comparable to MRM sensitivity benchmarks reported by Kane et al.20 which are the most sensitive to date for detection of RA. The LOD and LOQ for 9cRA and 13cRA have been reported to be comparable to atRA. This trend was the consistent with our observations for the RA isomers using fast HPLC MRM3 (data not shown). One typical drawback of multistage tandem mass spectrometry is each isolation/fragmentation event is accompanied by decreased ion signal. Because decreased ion signal translates to diminished sensitivity, any increase in selectivity gained by additional mass events needs to be evaluated in terms of lost sensitivity. Tandem quadrupole/linear ion trap mass spectrometers based upon the ion path of a tandem quadrupole mass spectrometer have displayed high trapping efficiencies and efficient axial ion extraction from the LIT that have led to performance improvements.41 Our results were consistent with those observations in that the increase in selectivity imparted by MRM3 detection yielded an increase in signal-to-noise sufficient to compensate for any lost ion signal due to an additional isolation/fragmentation event. As such, we achieved comparable sensitivity and increased selectivity with our MRM3 assay as compared to MRM detection.

Assay linearity was evaluated via generation of calibration curves that were fit using least-squares linear regression analysis. A representative calibration curve for atRA using gradient 2 demonstrated the linear range of 4 orders of magnitude (Figure S8, Supporting Information). Similar curves were generated for gradient 1 and the geometric isomers (data not shown). The linear working ranges extended from low fmol to 10 pmol. All calibration curves had correlation coefficients, r2, of 0.996 or higher.

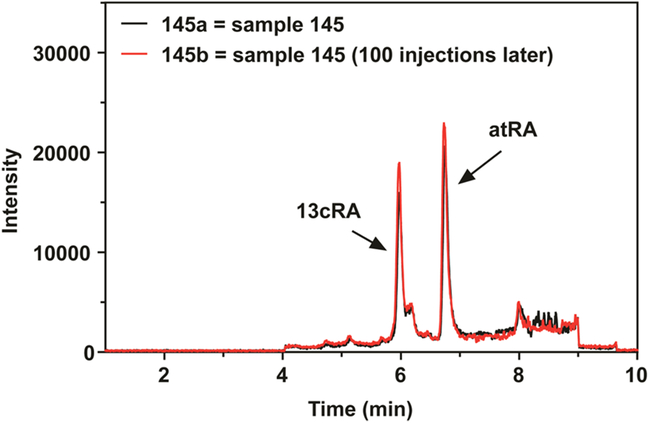

Accuracy and intra- and interday precision were evaluated by analysis of repeat measurements of standards prepared in neat solvent and plasma/tissue extracts. Assay accuracy, defined as the percent difference between nominal and measured values, was determined to be greater than 91%, 94%, and 94% for low (10 fmol), middle (100 fmol), and high (500 fmol) quality control samples, respectively. Instrumental coefficient of variance (CV) as measured using repeat measurements of neat standards was less than 4.0% for both intra- and interday experiments. Intraday assay precision as evaluated by CV of atRA quantification was 4.5% ± 0.2% for n = 6 pieces from the same liver. Interday precision (CV) of atRA quantification was 4.7% ± 0.2% for n = 10 pieces from the same liver. Furthermore, the average CV of triplicate analysis for atRA in 146 different human plasma samples measured over 5 days was 7.1% ± 3.8%. The MRM3 assay demonstrated excellent stability over time as illustrated by the overlaid chromatograms in Figure 3. These two chromatograms represent the same human plasma sample measured 100 injections apart and show nearly identical response.

Figure 3.

Fast HPLC-MRM3 of human plasma. Fast HPLC-MRM3 chromatograms for the same human plasma extract analyzed 100 injections apart to demonstrate method stability. Chromatographic peaks for 13cRA and atRA are noted.

Application.

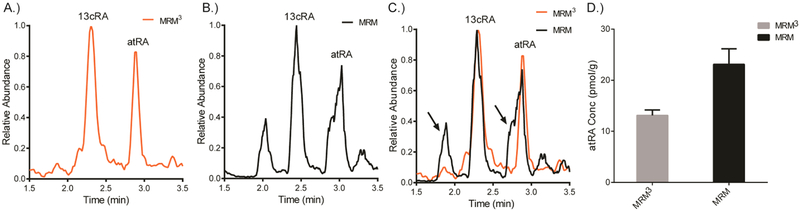

Quantification of endogenous RA in vivo is a crucial parameter for evaluating normal retinoid metabolism as well as addressing the role altered RA levels play in various disease and metabolically challenged conditions. For instance, the measurements of endogenous RA from tissue including liver, kidney, adipose, muscle, spleen, testis, and brain in mouse tissues have been reported and used to interrogate a variety of physiological processes linked to RA metabolism.5,19-21 Accurate quantification free of interferences is required to obtain biologically relevant data, and MRM3 has been reported to be an effective means to eliminate a nonspecific signal that interferes with MRM detection.48,49,56,57 Testis tissue has been previously reported to have nonspecific interferences during MRM detection of RA depending on the chromatographic system.39 Another recent report of MRM detection of RA in testis showed similar interference.58 Accordingly, we assayed testis tissue to test the utility of the MRM3 detection scheme for reducing interferences and applied the fast HPLC separation using both MRM3 and MRM detection schemes on the same samples. Figure 4 shows chromatograms for testis using MRM3 and MRM detection using the fast HPLC gradient 2 separation (Figure 4A,B, respectively). A distinct shoulder was observed on the atRA peak with MRM detection using this fast HPLC chromatographic separation (Figure 4B). The interference from structurally similar species of similar nominal mass that were observed with MRM detection of RA during some chromatographic conditions were likely due to abundant endogenous lipid species that coextract during the liquid–liquid extraction used in sample preparation. MRM3 detection removed this nonspecific signal that is observed in MRM detection through implementation of a second consecutive m/z transition which enhanced the selectivity of atRA detection (Figure 4C). The nonspecific signal observed in MRM detection was significant because it interfered with atRA quantification. The atRA values that were obtained with MRM detection were significantly altered (p < 0.05; biased high) as compared to MRM3 detection using the fast HPLC chromatographic system (Figure 4D). It should be noted that adequate chromatographic resolution of interfering species of similar nominal mass can be used to ensure specificity in MRM detection, albeit with significantly longer run times and significantly reduced throughput. Longer gradients using traditional porous particle stationary phases that chromatographically resolve RA from interfering signal and use MRM detection have returned statistically similar values for atRA in testis from C57BL/6 mice on a copius vitamin A content diet as compared to our current measurement using fast HPLC and MRM3 detection.20

Figure 4.

Comparison of fast HPLC-MRM3 and fast HPLC-MRM chromatograms from testis. (A) Fast HPLC-MRM3 chromatogram. (B) Fast HPLC-MRM chromatogram. (C) Overlaid MRM3 and MRM chromatograms. Note the shoulder on the left-hand side of the atRA peak in the MRM chromatogram and the additional peak not associated with RA designated with arrows. (D) Quantification of endogenous atRA from testis tissue using the fast HPLC-MRM and fast HPLC-MRM3 detection schemes. Data are mean ± SEM, n = 6, p < 0.001.

We additionally observed that enhanced selectivity of MRM3 detection coupled to the fast HPLC separation reduced analytical variability as compared to MRM detection coupled to fast HPLC separation. The MRM3 measurements of six individual animals had a CV of 17.9% which accounted for both analytical and biological variation. The MRM measurements of the same samples had a CV of 29.4%. Whereas identical samples (repeat injections from the same vial) were used for both MRM3 and MRM measurements, biological variation as the source of the error was eliminated and the 11.5% difference in CV was attributed to analytical variation introduced by the detection modality. Practically, MRM3 increased specificity sufficiently to permit the implementation of more rapid chromatography and this more rapid chromatography combined with multiplexing subsequently increased sample throughput by a factor of 3–5. As such, the maximum output of the fast HPLC-MRM3 multiplexing assay was 20 samples per hour for gradient 1 and 8 samples per hour for gradient 2.

The developed assay was utilized to generate reference RA values (Table 1) by quantifying retinoids in a number of tissues from multiple species where quantification of RA levels was of interest in regards to physiological processes.6,19 Wild-type C57BL/6 and Rbp1−/− mouse tissues were quantified to demonstrate assay utility in genetic mouse models that have been used to investigate retinoid metabolism.21,59 Nonhuman primate (NHP) RA was quantified to demonstrate assay applicability to additional animal models. NHP RA concentrations were largely similar to those obtained in mouse. Furthermore, human plasma samples from 41 healthy adults were analyzed for RA content to demonstrate assay applicability to human studies. Further details on quantification of RA from mouse, NHP, and human samples are provided in the Supporting Information.

Table 1.

Endogenous RA in Human, Mouse, and Non-Human Primate Tissues and Plasmaa

| RA: plasma (pmol/mL), tissue (pmol/g) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tissue/ fluid |

N | atRA | 9cRA | 9,13dcRA | 13cRA |

| Mouse (Wild-Type): C57BL/6 | |||||

| testis | 5 | 9.9 ± 0.7 | n.d. | 5.8 ± 0.6 | 1.7 ± 0.3 |

| liver | 5 | 14.2 ± 0.8 | n.d. | 4.8 ± 0.9 | 1.8 ± 0.2 |

| heart | 10 | 3.7 ± 0.2 | n.d. | 8.1 ± 0.4 | 1.5 ± 0.1 |

| lung | 10 | 9.9 ± 1.0 | n.d. | 12.1 ± 1.6 | 1.0 ± 0.2 |

| Mouse: Rbp1−/− | |||||

| testis | 16 | 12.8 ± 0.5c | n.d. | 5.4 ± 0.7 | 2.3 ± 0.2 |

| liver | 10 | 11.5 ± 0.5c | n.d. | 4.1 ± 0.3 | 2.2 ± 0.2 |

| heart | 10 | 2.8 ± 0.2c | n.d. | 8.2 ± 0.5 | 1.5 ± 0.3 |

| lung | 10 | 7.2 ± 0.7c | n.d. | 13.0 ± 1.3 | 0.9 ± 0.2 |

| Nonhuman Primate: Rhesus Macques | |||||

| liver | 3 | 9.5 ± 1.8 | n.d. | 1.9 ± 0.3 | 2.1 ± 0.7 |

| heart, left ventricle | 2 | 4.1 ± 0.6 | n.d. | 5.9 ± 0.8 | 1.5 ± 0.1 |

| heart, right ventricle | 2 | 4.0 ± 0.5 | n.d. | 8.1 ± 0.6 | 1.9 ± 0.4 |

| lung | 5 | 6.7 ± 0.6 | n.d. | 3.5 ± 0.1 | 1.4 ± 0.2 |

| Human | |||||

| plasma | 41 | 5.7 ± 0.2 | 0.1 ± 0.1b | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 6.6 ± 0.4 |

| plasma (male) | 24 | 5.5 ± 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.1b | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 6.5 ± 0.5 |

| plasma (female) | 17 | 5.8 ± 0.4 | 0.1 ± 0.1b | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 6.8 ± 0.6 |

RA values in Rbp1−/− mice were statistically equivalent to those in wild-type, except where noted. Individual NHP measurements for liver and heart were the average of three independent analyses for each animal for the number of animals listed. All values are the mean ± SEM expressed in pmol/g tissue or pmol/mL fluid. n.d. = not detected.

Possible origin due to light exposure or isomerization during preparation.

atRA values statistically different from WT mice, testis, liver, heart, and lung, had P-values of 0.0082, 0.0091, 0.0080, and 0.0407, respectively, between wild-type and Rbp1−/− mice.

The application of MRM3 detection using a hybrid tandem quadrupole/linear ion trap mass spectrometer to quantify low abundance endogenous metabolites is novel and has not yet been reported. Two other studies indicated the use of MRM3 for quantification of metabolites reporting application to exogenous drug metabolites in human hair as indicators of chronic abuse or acute consumption of cannabis.48,49 This application encountered difficulty in quantifying cannabinoid metabolites of THC, specifically 11-nor-Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol-9-carboxylic acid, due to the presence of structurally similar compounds that could not be removed by sample preparation and that interfered with MRM detection. MRM3 was cited to increase specificity and increase signal-to-noise as compared to MRM. The authors of both reports stated that they confirmed the validity and robustness of their MRM3 detection scheme by comparison to a well-established GC-NCI-MS/MS assay. In comparison, the fast HPLC MRM3 assay for RA described herein showed a reduction in interference caused by compounds of similar nominal mass thereby increasing the selectivity of RA detection and provided a robust comparison to a well validated LC-MS/MS assay.20

Among the LC-MS methodology previously reported for RA detection, retinoid quantification via HPLC/MSn using a three-dimensional quadrupole ion trap (QIT) preceded by a normal phase separation where RA was detected using MS3 was described.60 Whereas QIT instruments have similar low mass resolution and low mass accuracy as compared to tandem quadrupole instruments, QIT instruments typically have less sensitivity and less dynamic range.61 The lower sensitivity and lower dynamic range of a QIT instrument derives from the condition that QIT instruments have low trapping efficiency due to a small trapping volume. The small trapping volume constrains the capacity for ion storage which limits dynamic range in large part to overfilling the QIT. This leads to deterioration of the mass spectra and a nonlinear response with respect to ion number.35,41,62 Thus, even though QIT instruments can be used for MSn detection of small molecules and can impart excellent selectivity through MSn, the QIT is not usually regarded as best suited for quantitative analysis.62 Indeed, the previously reported HPLC/MSn assay for RA quantification was consistent with QIT performance in that the linear range displays over 2 orders of magnitude less dynamic range and the LOD was several orders of magnitude less sensitive than a previously reported MRM-based RA assay on a tandem quadrupole instrument20 or the MRM3-based RA assay, described herein, on a hybrid tandem quadrupole/linear ion trap mass spectrometer. Similarly, others have reported the use of MS3 in quantification assays for other analytes using ion trap instrumentation and, although these assays report increased selectivity with MS3 detection, they also revealed the analytical limitations of QIT for small molecule quantification including limited linear range and limited sensitivity.63,64

The analytical improvements including increased chromatographic efficiency and heightened selectivity without compromised sensitivity for endogenous RA quantification from complex matrices via the fast HPLC multiplexing MRM3 assay represents significant improvement in quantitative analytical methodology over previous quantitative assays. Consequently, the implementation of fast HPLC multiplexing MRM3 for RA quantification will enable a greater understanding of the role of endogenous RA in physiological function, disease, and injury.

SUMMARY

A fast HPLC multiplexing MRM3 assay was developed, characterized, and applied to the detection and quantification of endogenous RA isomers from complex matrices in order to remove interfering signal that was observed with MRM detection during some chromatographic separation systems. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time fast HPLC multiplexing MRM3 has been reported for quantification of not only RA but also for any other endogenous biological metabolite. The combined integration of fast HPLC, LC multiplexing, and MRM3 detection is a novel combination of analytical methodology which resulted in resolution of endogenous RA isomers, rapid analytical throughput, and enhanced specificity without compromising assay sensitivity. This assay will be used to investigate the role of RA in disease (e.g., cancer, inflammation, immune dysfunction, and reproductive and developmental disorders), and the increased throughput afforded here will be useful toward interrogating larger biological study groups (e.g., human populations).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by University of Maryland, Baltimore Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences New Faculty Start-Up funds and with Federal funds from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (Contract number HHSN272202000046C). The authors are very grateful to Norbert Ghyselinck and Pierre Chambon (Institut de Genetique et de Biologie Moleculaire et Cellulaire, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Medicale, Illkirch, France) for the Rbp1−/− mice. The authors thank Dr. Thomas J. Macvittie (University of Maryland, School of Medicine, Department of Radiation Oncology, Baltimore, MD) for the nonhuman primate tissue samples. The authors thank Dr. Douglas S. Kwon (Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT, and Harvard, Boston, MA) for the human plasma samples. All mass spectrometry research was performed at the University of Maryland School of Pharmacy Mass Spectrometry Center (SOP1841-IQB2014). Additionally, we would like to acknowledge and thank all members of the Kane laboratory.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Supporting Information contains description of experimental parameters, additional discussion of results, and corresponding tables and figures. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Campo-Paysaa F; Marlétaz F; Laudet V; Schubert M Genesis 2008, 46, 640–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Berry DC; Noy N Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1821, 168–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Tafti M; Ghyselinck NB Arch. Neurol 2007, 64, 1706–1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Gudas LJ Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1821, 213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Napoli JL Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1821, 152–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Chambon P FASEB J. 1996, 10, 940–954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Shaw N; Elholm M; Noy NJ Biol. Chem 2003, 278, 41589–41592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Chen N; Napoli JL FASEB J. 2008, 22, 236–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Mark M; Ghyselinck NB; Chambon P Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol 2006, 46, 451–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Ruberte E; Friederich V; Chambon P; Morriss-Kay G Development 1993, 118, 267–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Napoli JL; Boerman MH; Chai X; Zhai Y; Fiorella PD J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol 1995, 53, 497–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Napoli JL Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1999, 1440, 139–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Berry DC; DeSantis D; Soltanian H; Croniger CM; Noy N Diabetes 2012, 61, 1112–1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Kane MA; Folias AE; Pingitore A; Perri M; Obrochta KM; Krois CR; Cione E; Ryu JY; Napoli JL Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2010, 107, 21884–21889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Tang X-H; Gudas LJ Annu. Rev. Pathol 2011, 6, 345–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Altucci L; Gronemeyer H Nat. Rev. Cancer 2001, 1, 181–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Harrison EH Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1821, 70–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Kane MA; Folias AE; Wang C; Napoli JL FASEB J. 2010, 24, 823–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Kane MA; Napoli JL Methods Mol. Biol 2010, 652, 1–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Kane MA; Folias AE; Wang C; Napoli JL Anal. Chem 2008, 80, 1702–1708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Kane MA; Chen N; Sparks S; Napoli JL Biochem. J 2005, 388, 363–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Gundersen TE; Bastani NE; Blomhoff R Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom 2007, 21, 1176–1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Wang Y; Chang WY; Prins GS; van Breemen RB J. Mass Spectrom 2001, 36, 882–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Kane MA; Folias AE; Napoli JL Anal. Biochem 2008, 378, 71–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Schmidt CK; Brouwer A; Nau H Anal. Biochem 2003, 315, 36–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Wyss R; Bucheli FJ Chromatogr. B: Biomed. Sci. Appl 1997, 700, 31–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Napoli JL; Pramanik BC; Williams JB; Dawson MI; Hobbs PD J. Lipid Res 1985, 26, 387–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Hagen JJ; Washco KA; Monnig CAJ Chromatogr. B: Biomed. Sci. Appl 1996, 677, 225–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Siegenthaler JA; Ashique AM; Zarbalis K; Patterson KP; Hecht JH; Kane MA; Folias AE; Choe Y; May SR; Kume T; Napoli JL; Peterson AS; Pleasure SJ Cell 2009, 139, 597–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Germain P; Chambon P; Eichele G; Evans RM; Lazar MA; Leid M; De Lera AR; Lotan R; Mangelsdorf DJ; Gronemeyer H Pharmacol. Rev 2006, 58, 760–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Germain P; Chambon P; Eichele G; Evans RM; Lazar MA; Leid M; De Lera AR; Lotan R; Mangelsdorf DJ; Gronemeyer H Pharmacol. Rev 2006, 58, 712–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).McCormick AM; Kroll KD; Napoli JL Biochemistry 1983, 22, 3933–3940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Arnhold T; Tzimas G; Wittfoht W; Plonait S; Nau H Life Sci. 1996, 59, PL169–PL177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Horst RL; Reinhardt TA; Goff JP; Nonnecke BJ; Gambhir VK; Fiorella PD; Napoli JL Biochemistry 1995, 34, 1203–1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Hager JW Anal. Bioanal. Chem 2004, 378, 845–850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Van Eeckhaut A; Lanckmans K; Sarre S; Smolders I; Michotte YJ Chromatogr. B: Anal. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci 2009, 877, 2198–2207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Vogeser M; Seger C Clin. Chem 2010, 56, 1234–1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Sherman J; McKay MJ; Ashman K; Molloy MP Proteomics 2009, 9, 1120–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Kane MA Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1821, 10–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Fortin T; Salvador A; Charrier JP; Lenz C; Bettsworth F; Lacoux X; Choquet-Kastylevsky G; Lemoine J Anal. Chem 2009, 81, 9343–9352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Hager JW Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom 2002, 16, 512–526. [Google Scholar]

- (42).Hager JW; Yves Le Blanc JC Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom 2003, 17, 1056–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Hopfgartner G; Husser C; Zell M J. Mass Spectrom 2003, 38, 138–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Lemoine J; Fortin T; Salvador A; Jaffuel A; Charrier J-P; Choquet-Kastylevsky G Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2012, 12, 333–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Lakowski TM; Szeitz A; Pak ML; Thomas D; Vhuiyan MI; Kotthaus J; Clement B; Frankel A J. Proteomics 2013, 80C, 43–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Miyachi A; Murase T; Yamada Y; Osonoi T; Harada K-I J. Proteome Res 2013, 12, 2690–2699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Cesari N; Fontana S; Montanari D; Braggio S J. Chromatogr. B: Anal. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci 2010, 878, 21–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Thieme D; Sachs H; Uhl M Drug Test. Anal 2014, 6, 112–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Park M; Kim J; Park Y; In S; Kim E; Park Y J. Chromatogr. B: Anal. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci 2014, 947–948, 179–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Salisbury JJ J. Chromatogr. Sci 2008, 46, 883–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Ali I; Al-Othman ZA; Al-Za’abi M Biomed. Chromatogr 2012, 26, 1001–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Arnold SLM; Amory JK; Walsh TJ; Isoherranen N J. Lipid Res 2012, 53, 587–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Zweigenbaum J; Heinig K; Steinborner S; Wachs T; Henion J Anal. Chem 1999, 71, 2294–2300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Wu JT; Zeng H; Deng Y; Unger SE Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom 2001, 15, 1113–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Jemal M; Huang M; Mao Y; Whigan D; Powell ML Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom 2001, 15, 994–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Hunter C J. Biomol Tech 2010, 21, S34. [Google Scholar]

- (57).Jeudy J; Salvador A; Simon R; Jaffuel A; Fonbonne C; Léonard J-F; Gautier J-C; Pasquier O; Lemoine J Anal. Bioanal. Chem 2014, 406, 1193–1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Nya-Ngatchou JJ; Arnold SLM; Walsh TJ; Muller CH; Page ST; Isoherranen N; Amory JK Andrology 2013, 1, 325–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Pierzchalski K; Yu J; Norman V; Kane MA FASEB J. 2013, 27, 1904–1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).McCaffery P; Evans J; Koul O; Volpert A; Reid K; Ullman MD J. Lipid Res 2002, 43, 1143–1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Han X; Aslanian A; Yates JR Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2008, 12, 483–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Hopfgartner G; Varesio E; Tschäppät V; Grivet C; Bourgogne E; Leuthold LA J. Mass Spectrom 2004, 39, 845–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Rathahao E; Peiro G; Martins N; Alary J; Guéraud F; Debrauwer L Anal. Bioanal. Chem 2005, 381, 1532–1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Flamini R; Vedova AD; De Rosso M; Panighel A Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom 2007, 21, 3737–3742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.