Abstract

Differentiation of progenitors in a controlled environment improves the repair of critical-sized calvarial bone defects; however, integrating micro RNA (miRNA) therapy with 3D printed scaffolds still remains a challenge for craniofacial reconstruction. In this study, we aimed to engineer three-dimensional (3D) printed hybrid scaffolds as a new ex situ miR-148b expressing delivery system for osteogenic induction of rat bone marrow stem cells (rBMSCs) in vitro, and also in vivo in critical-sized rat calvarial defects. miR-148b-transfected rBMSCs underwent early differentiation in collagen-infilled 3D printed hybrid scaffolds, expressing significant levels of osteogenic markers compared to non-transfected rBMSCs, as confirmed by gene expression and immunohistochemical staining. Furthermore, after eight weeks of implantation, micro-computed tomography, histology and immunohistochemical staining results indicated that scaffolds loaded with miR-148b-transfected rBMSCs improved bone regeneration considerably compared to the scaffolds loaded with non-transfected rBMSCs and facilitated near-complete repair of critical-sized calvarial defects. In conclusion, our results demonstrate that collagen-infilled 3D printed scaffolds serve as an effective system for miRNA transfected progenitor cells, which has a promising potential for stimulating osteogenesis and calvarial bone repair.

Keywords: 3D printing, miRNA, Bone tissue engineering, Biofabrication

1. Introduction

Three-dimensional (3D) printing has recently been a promising approach in building anatomically-correct scaffolds with tailored architecture for bone restoration during craniofacial reconstruction [1,2]. Recent investigations on scaffold-based regenerative medicine using 3D printing have generated the demand for developing higher performance biomaterials for use in bone tissue repair that match the biomechanical properties of bone and possess sufficient bioactivity to stimulate new bone formation [3–11].

3D Printed scaffolds are commonly preferred over locally delivered therapeutics or stem cells for targeting a specific tissue type [12,13]. Although several successful attempts have been made using engineered stem cells expressing transcription or growth factors to heal criticalsized craniofacial defects, complete repair of such defects has still been a long-standing problem [10]. The use of diffusible cytokines to drive differentiation in implantable bone grafts has resulted in ectopic tissue formation and disorganized tissue interfaces. Moreover, systemic growth factor administration frequently fails in clinical trials because of their short half-life in vivo [11]. Implantation of mature differentiated cells, on the other hand, often results in poor tissue integration, reduced tissue volume, and robust host response [14,15].

Recently, gene therapy has gained significant interest for craniofacial reconstruction [8,16]. In particular, the use of microRNAs (miRNAs) have been a paradigm shift from previous methods and utilizing miRNAs to modulate the function and differentiation of stem/progenitor cells is an attractive therapeutic modality for regenerative medicine [17]. miRNAs are small non-coding RNAs that can regulate gene expression at the post-transcriptional level by binding to complementary sites on target messenger RNAs [18]; however, vectors are required to protect and deliver miRNAs into cells since they cannot easily cross the cell membrane and rapidly degrade in vivo [19,20]. Although several viral and non-viral vectors can deliver miRNAs into cells [21–23], launching an effective miRNA delivery system as successful therapeutic agents is still challenging due to limitations related to efficient delivery, biological stability, long-term presentation and targeting to facilitate spatial and temporal control [24]. To date, a few studies have demonstrated that miRNAs, namely miR-26a, –148b, –27a and –489, could induce osteogenesis in osteo-progenitor cells such as bone marrow-derived and adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs and ASCs) [25–27]. Among all, miR-148b delivery systems have been shown to regulate osteogenesis in mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). For example, Schoolmeesters et al. reported increased total alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity (an early biomarker of osteogenesis in human BMSCs) with miR-148b [27]. Mariner et al. showed that transfection with miR-148b had the effect of sensitizing human MSCs to soluble osteogenic factors resulting in rapid and robust induction of bone-related markers, including ALP activity and calcium deposition [28]. Li et al. demonstrated that miR-148b could promote bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling cascade by directly targeting the noggin gene in hASCs, which resulted in transcriptional activation of osteogenic genes including ALP, osteocalcin (OCN) and collagen type I alpha (CollA) [29]. Thus, in both hASCs and hBMSCs, miR-148b has shown to inductively promote osteogenic differentiation [18,27]. Moreover, miR-148a has been reported to play a role in promoting osteoclastogenesis by targeting the v-maf musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene homolog [30].

Although the majority of research endeavors has focused on miRNA profiling, signaling pathways and delivery systems, which inspire new applications in regenerative medicine [8], to the best of our knowledge, only a limited number of studies has been performed using 3D culture systems for delivering miR-148b for craniofacial reconstruction [17,31]. There is currently no established consensus on the best routes to proceed for bone regeneration and thus novel scaffold-based approaches should be investigated in order to better understand the role of miR-148b on calvarial bone repair.

In this study, we present a novel platform for miRNA delivery by engineering ex situ-activated 3D printed hybrid scaffolds. rBMSCs were transfected with miR-148b in 2D monolayer via photoactivated-miR-148b delivery conjugates. Then, they were loaded into collagen gel that was subsequently used to infill a 3D printed polymeric frame. The frame enabled the loading of miR-148b transfected rBMSCs via collagen infilling through pores, which could be tailored on demand by controlling design parameters such as pore size and filament diameter. The novelty of this work relies in the ability of miR-148b transfected rBMSCs to grow and differentiate in 3D printed hybrid scaffolds allowing us to study the impact of miR-148b on calvarial defect repair. This was intended as a feasibility study to demonstrate the success of 3D printed hybrid scaffolds as a new ex situ miR-148b delivery system for osteogenic induction in rat calvarial defects. The presented hybrid scaffold did not only serve as a delivery system for miRNA but was also used as a device for effective repair of bone tissue.

The miR-148b transfected rBMSCs were assessed in vitro in terms of proliferation and osteogenesis, and 3D printed scaffolds further tested for their effectiveness in repairing critical-sized calvarial bone defects in a Fischer rat model.

2. Materials and methods

Custom modified miR-148b with 3′ thiol and nitrobenzyl spacer insertion, and 6-TAMRA 5′ label was purchased from Trilink Biotechnologies (San Diego, CA). NaOH pellets, formaldehyde (36%), antifoam A concentrate, (hydroxypropyl) cellulose (HPC) (99%), silver nitrate (AgN03) (> 99%), sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) (> 99%), phosphate buffer saline (PBS) powder, sodium chloride (NaCl) (> 99.5%), tris(2-carboxyethyl) phosphine hydrochloride (0.5 M) and tris (hydroxymethyl) aminomethane (Tris) (> 99.8%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

2.1. Synthesis of photoacdvated-miR-148b delivery conjugates

HPC-modified silver nanoparticles (SNPs) were synthesized and functionalized with the photocleavable miR-148b as described before [32]. Briefly, silver nanoparticles were synthesized by adding 125 mM AgNO3 and 61.5 mM formaldehyde to a solution containing 0.5 g NaOH, 0.31 g HPC, 330 mL deionized water, and 5 μL antifoam A agent at room temperature at rate of 0.5mL/min. The silver nanoparticles were purified by dialysis overnight followed by lyophilization over 72 h. The 6-TAMRA-labeled oligonucleotides were mixed with HPC-SNP (100 ppm) at a molecular to NP number ratio of 5000:1, respectively. The NP suspension was incubated at 37 °C under rocking conditions for 24 h to facilitate the thiol linkage of the oligo onto the SNP surface. The following day, 1% SDS (10 μL) and 25 mM PBS (20 μL) were added to the SNP-oligo conjugate solution to initiate the Tris-buffer based salt-aging process. After 24 h, the solution was adjusted to 20 mM NaCl and 10 mM Tris buffer (pH 8.0) concentration by adding 5 μL of a 1 M Tris-NaCl buffer. Functionalized nanoparticles were purified by centrifuging at 2700g for 20 min and then re-suspended in deionized water (18.2 MΩ) prior to analysis. Oligonucleotide surface quantification was determined by treating and reducing the sulfide bond with tris (2-carboxyethyl) phosphine hydrochloride and measuring the fluorescence intensity of the released 6-TAMRA fluorophore in the supernatant sample. Oligonucleotide samples were quantified by measuring 6-TAMRA fluorescence intensity recorded at 570 nm (540 nm excitation) (Spectramax M5 Microplate/Cuvette Reader, Molecular Devices, PA). The nanoparticle quantity was determined by inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES) (Perkin Elmer Optima 5300 DV Optical Emission Spectrometer, Walthon, MA). To measure the photo-release of the conjugated miR-148b from the silver nanoparticles at 405 nm irradiation, the supernatants of samples exposed to increasing light energy doses were collected and measured for TAMRA fluorescence measurements, as described above. The intensities were normalized to a negative control of a non-irradiated sample, as well as to the total particle loading. All illumination experiments were carried out using a mounted 405 nm LED light source at a power setting of 0.8 W, purchased from Thorlabs (Newton, NJ).

2.2. miR-148b particle size and surface charge measurements

Nanoparticles were also measured before and after modification for size using dynamic laser light scattering (DLS) (4 mW He-Ne laser with a fixed wavelength of 633 nm, 90° backscatter at 25 °C in disposable 10 × 10 × 45 mm polystyrene cell) as well as for surface zeta potential charge (DTS1070 Malvern cell) using a Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS instrument (Worcestershire, UK). All measurements for miR-148b particle size and surface charge measurements were performed in triplicates and values are reported as the mean ± standard error mean.

2.3. Fabrication and characterization of collagen-infilled 3D printed hybrid scaffolds

Composite ink made of polycaprolactone (PCL) (MW 70,000, Scientific Polymer Products, Ontario, NY)/poly (d,l-lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) (Resomer® RG 503 [50:50], Evonik Industries, Essen, Germany)/hydroxyapatite nano-particles (HAp 202, Fluidinova, Mala, Portugal) was prepared at a mixing ratio of (4.5:4.5:1) (v/v) as described in our previous work [33]. Collagen was extracted from rat tails according to a previously published study [34] and then dissolved in 0.02 N acetic acid solution (VWR International, Radnor, PA) to prepare 9 mg/mL solution. Next, neutralized collagen solution was prepared by mixing 9 mg/mL collagen solution with 10× Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline (DPBS) (Mediatech, Inc., Manassas, VA), HyClone™ deionized water (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), and 0.2 N sodium hydroxide solution in water (NaOH) (EMD Millipore Corporation, Burlington, MA) at a mixing ratio of (5:1:3:1) (v/v).

PCL/PLGA/HAp frames (7.45 × 7.35 × 10 mm) were fabricated using a custom-made mechanical extrusion tool [33] mounted on the Multi-Arm BioPrinter (MABP) developed in our past work [35]. A raster gap of 1.2 mm and a filament thickness of 500 μm were used as design parameters and all other parameters including the nozzle size (inner diameter), printing speed and extrusion temperature were set to be 0.61 mm, 40 mm/min and 140 °C, respectively. Next, neutralized-collagen solution was pipetted into 3D printed frames to infill the pores and then hybrid scaffolds were incubated at 37 °C for 15 min in order to fully crosslink the collagen solution.

After fabrication, structural properties of 3D printed frames, including filament diameter (μm), pore size (μm), printability, skeletal density (g/cm3), and porosity volume (%), were determined according to our previous study [33]. Surface and morphological characterization of 3D printed frames (with and without collagen) were visualized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Briefly, scaffolds were freeze-dried (Labconco, Kansas City, MO) over-night, and then dipped into the liquid nitrogen in order to cross-section the filaments using a sharp blade without shearing the samples. Then, samples were mounted on a carbon conductive double-faced adhesive tape (Nisshin EM Co., Ltd., Tokyo Japan) and placed on a specimen mount holder. Thereafter, the holders were placed in an EM ACE600 sputter coater (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) for a total coating thickness of 20 nm. Coated samples were inserted in a vacuum chamber and imaged with a Nova NanoSEM 630 Ultra-High-Resolution scanning electron microscope (Nanolab Technologies, Milpitas, CA) using the Everhart-Thornley detector (ETD) at an accelerating voltage of 5.0 keV under the high vacuum mode with a working distance from 3.4 to 4.9 mm.

Mechanical properties of 10-layer printed frames (with and without collagen) were determined by compressing them up to 50% strain using an Instron 5966 mechanical tester (Instron, Norwood, Massachusetts) operated with a 10 kN load cell (2580-201, Instron) at a crosshead speed of 50mm/min according to a previously published study [36]. Peak compressive stress and Young’s Modulus within the linear region of resulting stress-strain curve were obtained from an average of three constructs.

2.4. In vitro cell culture study and cellular transfection

rBMSCs were extracted from inbred 4 weeks-old female Fischer white rats (F344/DuCrl, Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) based on previously published procedure [37]. Briefly, rats were euthanized according to American Association for Laboratory Animal Science (AALAS) and The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC, protocol number: 46591). Thereafter, rBMSCs were extracted from femurs and tibias of limbs flushing Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) through marrow cavity via 22-gauge needle. Isolated rBMSCs were plated on 6-well cell culture plates in Minimal Eagle’s Medium, Alpha modification (αMEM; Corning Cellgro, Manassas, VA) including 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 2 mM l-glutamine (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 100 u/mL penicillin (Sigma-Aldrich) and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator and culture media was changed every day until removing all of the non-adherent cells. After 90% confluency, cells were treated with 0.25% Trypsin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and transferred into 75 cm2 flasks to use in further in-vitro studies. Osteogenic differentiation capability of extracted rBMSCs was tested after seeding the cells on 2D monolayer using differentiation media over time in culture in our previously published study [38].

In order to transfect cells with silver nanoparticle conjugated miR-148b, half million rBMSCs were seeded onto 35 mm Petri glass-bottom dishes and incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2 for 24 h prior to transfecting the SNP-miR148b-TAMRA particles. Cells in 2D monolayer in 35 mm Petri dishes were transfected with SNP-miR148b conjugates (100 μL, 34 nM miR148b, 200 ppm SNPs) for 16 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2. The transfected cells were then photoactivated at 405 nm (0.8 mW, 10 min) to release miR-148b.

2.5. Confocal microscopy colocalization & transfection efficiency

A total of three groups were prepared: (i) rBMSCs only, (ii) rBMSCs transfected with SNP-miR148b-TAMRA, and (iii) rBMSCs transfected with SNP-miR148b-TAMRA and illuminated at 405 nm. After transfection, cells were allowed to incubate for 12 h, and imaged for colocalization between the SNPs (blue) and TAMRA-tagged miR148b (red) using an Olympus FV10i-LIV Confocal (Tokyo, Japan), where SNPs were imaged under the Blue-Narrow fluorescence channel (Ex 405 nm/Em 420-460 nm), and 6-TAMRA was viewed under the TRITC channel (Ex. 552 nm/Em. 558 nm) at 60× magnification. Post-imaging, all samples were trypsinized and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min for flow cytometry analysis using BD SORP LSRFortessa Cytometer (Franklin Lakes, NJ). 50,000 events were counted, with 3 replicates used for each analyzed group. The percentage of rBMSCs transfected with the SNP-miR148-TAMRA construct was determined using the phycoerythrin (PE) channel to view the TAMRA fluorophore, while fluorescein isothiocynate (FITC) was used for SNP plasmon scattering. rBMSC samples were run at a flow rate of 0.5 μL/s and all analysis were performed using FlowJo software.

2.6. Cell viability and proliferation assays

3D Printed dual-layer frames (7.45 × 7.35 × 1 mm) were sterilized using an Anprolene gas sterilizer (AN74iX, Anderson Sterilizers, Haw River, NC). After sterilization, 1 mL of neutralized collagen solution was mixed with 2 × 106 rBMSCs. Next, collagen encapsulated cells were injected manually into the 3D printed frames by infilling the pores. Similarly, this process was repeated for miR-148b transfected rBMSCs group. Cell-laden 3D hybrid scaffolds were incubated at 37 °C in 90% humidity and 5% CO2 for 15 min without adding any aqueous solution in order to fully crosslink the collagen solution according to the previously published study [38].

Cell proliferation assay was performed using a cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) (Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Rockville, MD) at Days 1, 4, 7 and 14, as previously described [25]. Briefly, scaffolds were washed with DPBS thrice, and then 500 μL of growth media and CCK-8 solution mixture at the ratio of 10:1 (v/v) was added. After 2 h of incubation at 37 °C, triplet replicates of 120 μL of solution were placed into a microplate scanning spectrophotometer (Bio-Tek PowerWave ×340, Bio-Tek Instruments Inc., Winooski, Vermont) and data were collected in total of six scaffolds per each group at 450 nm and reported as the mean ± standard error mean.

In order to visualize live and dead rBMSCs and miR-148b transfected rBMSCs on Day 14, scaffolds were washed with DPBS three times and then stained with a solution made of 2 μM calcein AM (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 1 μM ethidium homodimer-1 (ThermoFisher Scientific). After 20 min of incubation at 37 °C in dark, constructs were washed with DPBS three times and imaged using an Olympus BX61 microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan), where live and dead cells visualized under FITC green fluorescence (at a wavelength of 518 nm) and Alexa Fluor red fluorescence (at a wavelength of 543 nm), respectively. Images were taken with UPLFLN (NA:0.13) 4× and 10× objectives using Olympus cellSens software.

2.7. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

In order to determine the differentiation of rBMSCs and miR-148b-transfected rBMSCs towards osteogenic lineage, RT-PCR was used to examine osteogenesis-related gene expressions on Days 14 and 21 of incubation in the growth media. At these time points, a total of three scaffolds with duplicates from both groups, were collected separately in Eppendorf tubes containing 1 mL of TRIzol® reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) after rinsing the media with DPBS. Samples were then placed at −80 °C. RNA extraction process was started after thawing the samples at room temperature and then homogenized using a pestel motor mixer (Argos Technologies, Inc., Vermon Hills, IL). Next, 0.2 mL of HPLC grade chloroform (EMD Millipore Corporation) was added to the homogenized solution and mixed for 15 s and incubated for 5 min at room temperature. Then, samples were centrifuged at 12,000 ×g for 15 min at 4 °C using a Labnet Prism™ R Refrigerated Microcentrifuge (Labnet International Inc., Edison, NJ). Next, colorless upper aqueous phase from the separation was pipetted to new Eppendorf tube and mixed with 0.5 mL of molecular biology grade isopropanol (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in order to precipitate RNA. Then, tubes were incubated at room temperature for 10 min and centrifuged at 12,000 ×g for 10 min at 4 °C. When RNA was collected at the bottom of the tube, the RNA pellet was washed with 70% of 1 mL ethanol (VWR Life Sciences) and centrifuged at 7500 ×g for 5 min at 4 °C. Ethanol washing process was repeated to remove the supernatant completely. When ethanol was completely removed from the tube, RNA was dissolved in 50 μL of diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated water (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and then concentration was measured using NanoDrop (ND-1000 Spectrophotometer). In total, 1 μg of RNA was pipetted into AccuPower® CycleScript RT PreMix (Bioneer, Daejon, South Korea) and DEPC water added to fill up the reaction volume to 50 ×L. Then, complementary deoxyribonucleic acid (cDNA) was synthesized using T100 Thermal Cycler (BioRad, Hercules, CA) according to the AccuPower® protocol. Next, RT-PCR was performed in triplicates per gene in a 96-well plate using the Power SYBRTM Green Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Science). After pipetting the primer and cDNA mixtures into each well, the plate was placed in a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) to run comparative cycle threshold method in total of 45 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C and 1 min at 60 °C followed by the thermal dissociation protocol for SYBR green detection. Thereafter, the fold change in gene expression of the target genes including runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2), ALP, and OCN were quantified using the 2−ΔΔCT method normalized by glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) housekeeping gene of untreated rBMSCs at time 0 based on the previously published study [39] and values were reported as the mean ± standard error mean. Forward and reverse primers for the targeted genes are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Forward and reverse nrimers for the measured mRNA for RT-PCR.

| Gene | Forward primers | Reverse primers |

|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | 5′-GGC ATG GAC TGT GGT CAT GA-3′ | 5′-CAA CTC CCT CAA GAT TGT CAG CAA-3′ |

| RUNX2 | 5′-CCG ATG GGA CCG TGG TT-3′ | 5′-CAG CAG AGG CAT TTC GTA GCT-3′ |

| OCN | 5′-GAG CTG CCC TGC ACT GGG TG-3′ | 5′-TGG CCC CAG ACC TCT TCC CG-3′ |

| ALP | 5′-TCC GTG GGT CGG ATT CCT-3′ | 5′-GCC GGC CCA AGA GAG AA-3′ |

2.8. In vitro immunofluorescence imaging

After 14 days of incubation, morphologies of rBMSCs and miR-148b-treated rBMSCs were visualized by confocal microscopy in order to confirm cytoskeletal organization and osteogenic differentiation. Scaffolds were first rinsed three times with DBPS and then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich) overnight at 4 °C. The following day, the scaffolds were washed three times with DPBS and then permeabilized using 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min at room temperature. A blocking buffer solution of 2.5% normal goat serum (NGS) (Sigma-Aldrich) in DPBS was applied on constructs for 60 min at room temperature.

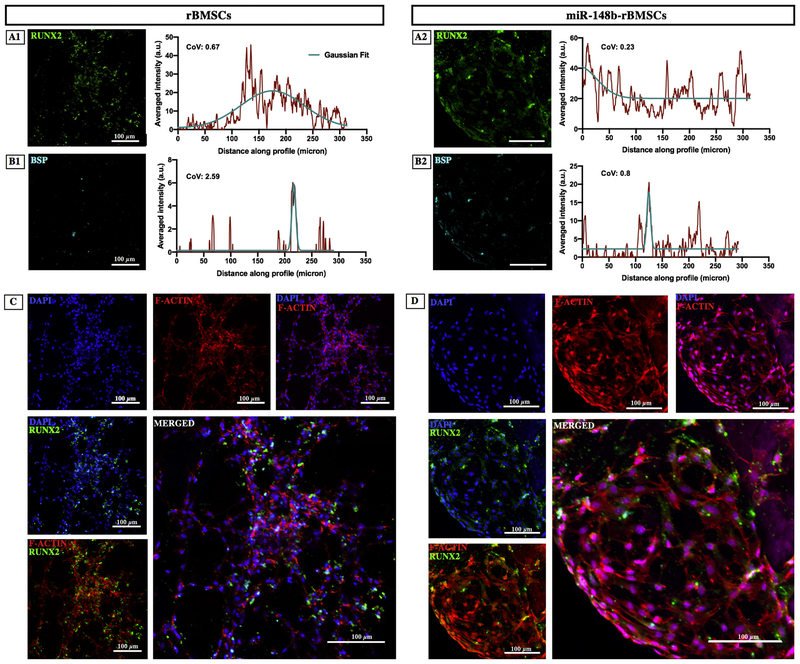

To visualize osteogenic differentiation, samples were incubated with rabbit anti-bone sialoprotein antibody (BSP) (catalog number: ab52128) (1:100 (v/v) in 2.5% NGS) and mouse anti-RUNX2 antibody (catalog number: ab76956) (1:100 (v/v) in 2.5% NGS) at 4 °C for overnight at dark. The next day, samples were washed three times with DPBS. Then, samples were incubated with goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 633 secondary antibody (1:100 (v/v) in 2.5% NGS) for BSP (cy5 fluorophore) and goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 secondary antibody for RUNX2 (green fluorophore) for 2 h at room temperature in dark. To visualize cellular morphologies and cytoskeletal organization, Phalloidin (A12380, Moleculer Probes) (1:100 in 2.5% NGS) and Hoechst nucleic acid staining (Life Technologies) (1:500 in 2.5% NGS) solutions were mixed into the secondary antibody solution, which were imaged using a laser excitation wavelength of Alexa Fluor 568 (red fluorophore) and 405 (blue fluorophore) nm, respectively. Then, constructs were washed three times with DPBS and imaged using an Olympus FLUOVIEW FV1000 laser scanning confocal microscope (Olympus America Inc., Melville, NY) via UPLAPO 10× NA:0.40 objective with 0.75 magnification. Images were captured with a 2× line scanning Kalman filter and acquired in a sequential scan mode via FV10-ASW version 3.0 system software in order to reduce the detector noise.

In order to quantify the distribution homogeneity of expressed RUNX2 and BSP antibodies, plot profile of images was obtained using Image J after converting them into binary images. Thereafter, Gaussian curve was fit on the plot profile to determine the mean and standard deviation of the curvature. Next, coefficient of variation (CoV) was calculated by dividing the standard deviation by mean to determine the variation of distribution along x-axis, where the smaller CoV indicates the greater data homogeneity [40].

2.9. In vivo study

Eight male Fischer 344 rats (12-weeks old, 190–200 g) were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA) and cared for in our animal facility (Millennium Science Complex, PSU, PA) according to AALAS and IACUC (protocol number: 46591). In order to create two critical-sized calvarial defects (5 mm) per animal, rats were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (Midwest Veterinary, Lakeville, MN) mixed with xylazine (LLOYD Inc., Shenandoah, IA) at a dose of 100 mg/kg for ketamine and 10 mg/kg for xylazine. When animals were fully anesthetized, artificial tears (Rugby Laboratories, Livonia, MI) were placed on both of eyes of the rats and heads were shaved and treated with betadine surgical scrub followed by ethanol. Bupivicaine (0.015 mg/kg) (Centralized Biological Laboratory, PSU, PA) at a concentration of 2.5 mg/mL was injected at the site of incision under the skin (approx. 0.15–0.2 mL) pre-surgery. A sagittal incision (approximately 2 cm in length) was made through the skin and the skin was pulled back to expose the periosteum. A sagittal incision was made through the periosteum, which was retracted to expose the calvarium. Total of 16 defects (5 mm, each with 1 mm in depth) were drilled into the parietal bone on each side of the skull using a trephine bit, taking care to keep the dura matter intact. One defect was excluded from the study due to the damage on coronal and sagittal suture lines during the drilling process. Then, rBMSCs (n = 5) and miR-148b transfected rBMSCs (n = 5) were seeded in hybrid scaffolds and then implanted into defects. Empty defect (n = 5) was used as a negative control group. In defect assignments on rats, randomization was performed to satisfy the independency requirement. After implantation, periosteum and skin were closed and sutured with simple interrupted 5–0 monocryl (Ethicon Inc., Somerville, NJ) and 4–0 vicryl (Ethicon Inc.) sutures, respectively.

Animals were placed on a warming pad allowing recovery, and the same dose of buprenorphine was administered post-surgery. Then, animals were observed closely until they were awakened from sternal recumbency. Following the post-surgery recovery, a single dose of buprenorphine (0.015 mg/kg) was administered every 12 h for a minimum of 24 h of analgesia. Animals were observed and weighed daily for at least 10 days post-surgery and weighed once a week after removing the sutures on Day 10. Eight weeks after the surgery, animals were euthanized by CO2 inhalation of 2 L per min until breathing cessation and subsequent decapitation.

2.10. Determination of bone regeneration

Micro-computed tomography (μCT) scanning was performed based on our previously published work [25]. A vivaCT 40 scanner (Scanco Medical, Switzerland) was used with 17.5 μm isometric voxels, 70 kV energy, 114 μA intensity, and 200 ms integration time. Thereafter, image analysis was conducted using a precisely 3D oriented volume of interest (VOI) in Avizo (FEI Company, Hillsboro, OR), MATLAB (Natick, MA), and ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Following a Gaussian smoothing filter (sigma 0.9), four points spaced around the circumference of each defect were located midway through the calvarium thickness. These points were exported to a custom written MATLAB script, which calculated a best-fit plane and transform matrix for an orthogonal coordinate system with origin at the center of the defect and one axis parallel to the direction of calvarium thickness. A cylindrical VOI with a radius of 2.5 mm and a height of 1 mm was then centered at the origin of this coordinate system in Avizo [41]. Bone voxels were labeled using a threshold cutoff of 300 mgHA/cm3. The volume of all bone voxels within the VOI above this threshold was summed and then divided by the total cylindrical volume to yield bone volume divided by total volume (BV/TV (%)). Relative bone mineral density (BMD) was calculated by dividing the bone tissue mean BMD within the VOI by native mean calvarial BMD, which was calculated using a small VOI located between the two defects in a region that was not drilled during surgery. Bone coverage area was calculated by a maximum intensity projection of the binary 3D thresholded VOI data onto a plane defined by the long axis of the cylinder and is expressed as area percentage of a circle with a radius of 2.5 mm. Connectivity was calculated by exporting the thresholded VOI data from Avizo to ImageJ and using the BoneJ2 plug-in tools including Purify and Connectivity. The calculated number of connected segments was then normalized by the total VOI to determine the connectivity density.

2.11. Histology and immunohistochemistry

After μCT scanning, calvarial explants were extracted, rinsed with DPBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for two days at 4 °C. Then, explants were decalcified with 0.5 M ethylenediaminetetraacetic (EDTA) acid disodium salt (Research Products International, Mt. Prospect, IL) solution approximately 6 weeks at 4 °C. After decalcification, samples were embedded in cyromatrix (ThermoFisher Scientific) embedding resin and sectioned using Leica CM1950 Cryostat (Leica Biosystems, Wetzlar, Germany) at −20 °C with 20 μm thickness. After collecting the sections on glass microscope slides, samples were placed on a slide rack in Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) automated staining platform (Leica Auto Stainer XL, Leica Biosystems) without applying any heat during the staining process based on the manufacturer’s protocol. After the staining process, stained sections were mounted using a xylene substitute mountant (Thermo Scientific) and kept at room temperature to dry overnight. Sectioned samples were also stained for Masson’s Trichrome (HT15–1KT, Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Then, both H&E and Masson’s Trichrome stained samples were imaged using a Keyence BZ-9000 (Keyence Corporation of America, Elmwood Park, NJ) fluorescence microscope under bright field with 2× magnification using a neutral density optical filter.

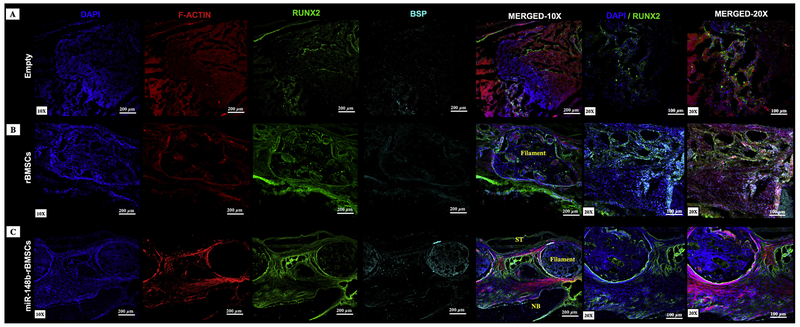

Similar to the immunofluorescence staining protocol, sectioned slides were used for DAPI, F-ACTIN, RUNX2, BSP for immunohistochemistry staining to evaluate the in vivo differentiation of implanted scaffolds. Images were obtained using an Olympus F100 microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) at 10× and 20× magnifications.

2.12. Statistical analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation unless stated otherwise. Normality test was performed on all data before performing statistical tests. Zeta potential, Young’s modulus, peak stress and RT-PCR data were analyzed using two-sample t-test (one-tailed) assuming equal variances with a 95% confidence interval. Two-way ANOVA with repeated measurements was used to determine cell proliferation studies at a 95% confidence level. Coefficient of variations of two groups was compared using the two-sample standard deviation test at a 95% confidence level. Bone regeneration data were analyzed by two-sided one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Fisher’s individual tests for differences of means at a 95% confidence level. Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05 (*), p < 0.01 (**), and p < 0.001 (***). All statistical analysis was performed using Minitab 17.3 (Minitab Inc., State College, PA).

3. Results

3.1. miR-148b delivery conjugates and transfection efficiency

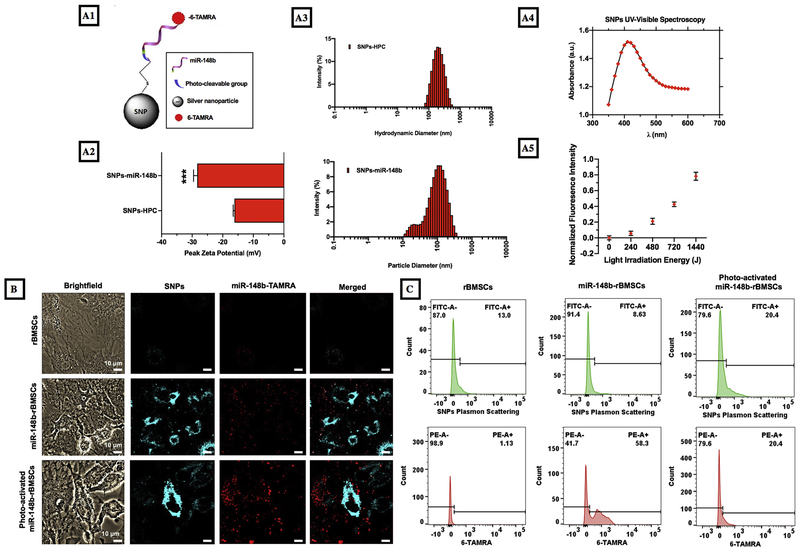

miR-148b delivery conjugates were synthesized by functionalization of silver nanoparticles via a modified salt-aging technique with a photo-cleavable group (Fig. 1A) [18]. Modified miRNA was used to facilitate the linkage of the molecule to the SNP surface using the thiol terminal 3′ end, and a nitrobenzyl photocleavable linker between the 3′ terminal and miR-148b sequence to enable temporal photocleavage and release of miRNA. 5′ fluorescence modification enables the quantification of oligo load on nanoparticle as well as imaging and fluorescence intensity measurements upon photo-irradiation. Quantification of the supernatant yielded a concentration of 34.30 ± 9.96 nM of miR-148b tethered to the nanoparticles and 24.5 ± 0.7 ppm of silver nanoparticles based on readings from ICP-AES (data not shown). Dynamic light scattering measurements showed that zeta potential significantly (p < 0.001) shifted from −16.17 ± 0.23 mV to −28.33 ± 0.70 mV from SNP-HPC to SNP-148b after functionalization as a result of the conjugation of the negatively charged nucleic acid to the SNPs (Fig. 1A2). A change in nanoparticle hydrodynamic size from 166.4 ± 2.8 to 75.1 ± 1.1 nm as the bulky HPC molecules (MW ~80,000) were displaced with much smaller (MW = 8841) miRNA molecules (Fig. 1A3). The shoulder in the size distribution was likely due to trace amounts of unattached miRNA molecules forming disulfide bridges and clusters. In this study, a photo-activation wavelength within the range of 400-415 nm was selected based on the extinction spectra of SNPs, which demonstrated high absorption within such range (Fig. 1A4). Despite its photo-sensitive region at around 365 nm, the nitrobenzyl photo-cleavable (PC) linker was shown to cleave at longer wavelengths, up to 450 nm, when coupled with plasmonic SNPs [42]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time demonstrating the cleavage of the PC linker at 405 nm enhanced by the plasmonic effect of the SNPs (Fig. 1A5). Supernatant of illuminated samples were measured for fluorescence intensity and the measured intensity was normalized to the intensity of a non-illuminated sample supernatant. The increase in light intensity resulted in an increase in fluorescence intensity suggesting photocleavage. The release profile suggests a linear response to increasing light energy for the photo-sensitive linker.

Fig. 1.

Representation and characterization of miR-148b delivery conjugates. (A1) A schematic of miR-148b nanoparticles, (A2-A3) DLS results, (A4) absorbance spectra for photo-release, and (A5) light irradiation energy vs fluorescence intensity graph for conjugates at 405 nm irradiation. (B) Images represent brightfield views, silver particle reflectance (405/420–460 nm), 6-TAMRA fluorescence (552 nm/558 nm), and reflectance and fluorescence overlay of rBMSCs, miR-148b-transfected rBMSCs and photo-activated miR-148b-transfected rBMSCs. (C) Representative flow cytometry histograms of rBMSCs, miR-148b transfected rBMSCs and photo-activated miR-148b transfected rBMSCs with PE and FITC channels (Note: n = 3 samples were used to calculate the differentiation efficiency).

Colocalization of the SNPs and miR148b-TAMRA molecules was determined by utilization of confocal microscopy to view SNPs through the blue channel and miR148b-TAMRA through the red TRITC channel. Images for all three groups are shown in Fig. 1B. Upon conjugation to the nanoparticle surface, the fluorescence property of the photo-active TAMRA molecule was quenched [43]. This was a result of its close proximity to the nanoparticle surface based on distance-dependent fluorescent resonance energy transfer (FRET) from one molecule to another [44]. The quenching phenomenon decreased as the distance between them increased upon photo-irradiation and the electron energy levels ceased to overlap. The calculated Mander’s coefficient (MOC), an established mathematical procedure to calculate the overlapping colocalization between different probes, was used to determine the qualitative release as described previously [45]. The non-illuminated sample yielded MOCs of 0.441 and 0.261 for the illuminated sample. The decrease in colocolization alludes to the separation of the miR148b-TAMRA molecules from the SNPs as they were photo-activated and released. The low MOC for the non-irradiated sample was likely due to the exposure of the sample to a high intensity confocal laser source at 405 nm, inducing a premature and unintended photo-cleavage of PC-miR148b-TAMRA molecules.

Flow cytometry analysis revealed 56.1 ± 2.2% of cells contained SNP-miR148b-TAMRA 12 h post-transfection, just before illumination (Fig. 1C). The red PE channel was used to observe surface-conjugated TAMRA fluorescence in gated live cell populations. After photo-activation, the percentage decreased likely due to quenching of the fluorophore under the intense near-UV-light, or leakage into solution of the free TAMRA molecules from the permeabilized and suspended cells. To view the backscattering from SNPs, the green FITC channel was utilized, which showed modest increases post-transfection and illumination, suggesting a stronger emission profile of the miRNA free SNPs.

3.2. Fabrication of miR-148b enriched hybrid scaffolds

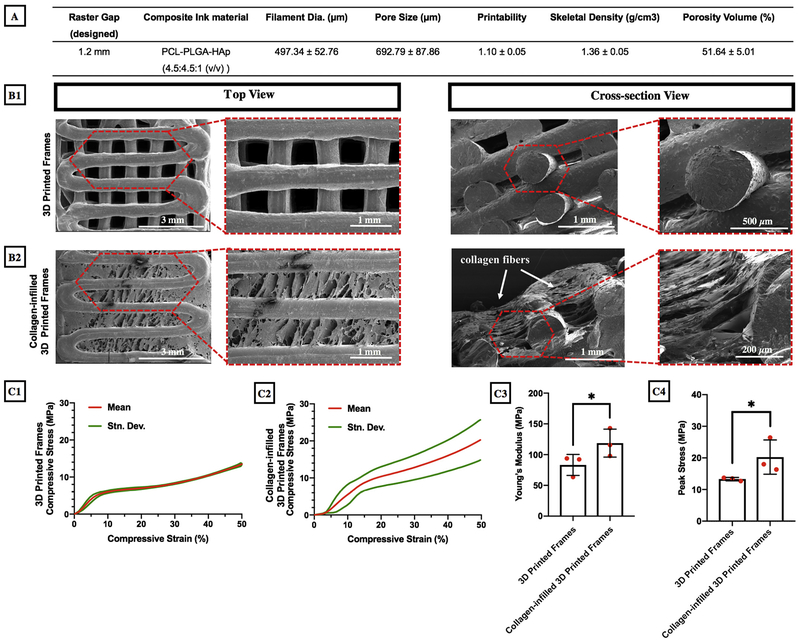

The PCL/PLGA/HAp composite ink was 3D printed via a custom-made mechanical extrusion system under tightly-controlled process conditions resulting in a printability value of 1.1 as presented in Fig. 2A. 3D Printed frames exhibited a filament thickness of 497.34 ± 52.76 μm and a pore size of 693 ± 88 μm. Fig. 2B1–B2 clearly demonstrate that 3D printed frame had an interconnected porous morphology, which was confirmed by SEM images. Furthermore, collagen filled pores of 3D printed frames closing the gap between filaments. Moreover, 3D printed frames had a circular filament morphology and the total porosity was measured to be 51.64 ± 5.01% (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

(A) Structural properties of 3D printed frames; SEM images of (B1) 3D printed frame-only and (B2) collagen-infilled samples; (C1–C2) Compressive mechanical properties, (C3) Young’s modulus and (C4) peak stress of 3D printed frame-only and collagen-infilled samples (*p < 0.05, n = 3).

Mechanical properties of 3D printed frames, with and without collagen infill, were tested using a compression test and the compressive stress (MPa) was plotted against the compressive strain (%) as shown in Fig. 2C1–C2. Young’s modulus for both groups, calculated from the linear portion of the elastic region up to 10%, were determined to be 83.21 ± 17.09 MPa for 3D printed frames and 118.74 ± 22.71 MPa for collagen-infilled 3D printed frames (p = 0.048) (Fig. 2C3). Furthermore, the peak stress was determined to be significantly higher (p = 0.046) in collagen-infilled 3D printed frames (20.25 ± 5.42 MPa) compared to the empty frames (13.28 ± 0.55 MPa) enabling the constructs to withstand higher compressive loads [46] (Fig. 2C4).

3.3. Cell proliferation, viability and morphology in 3D printed hybrid scaffolds

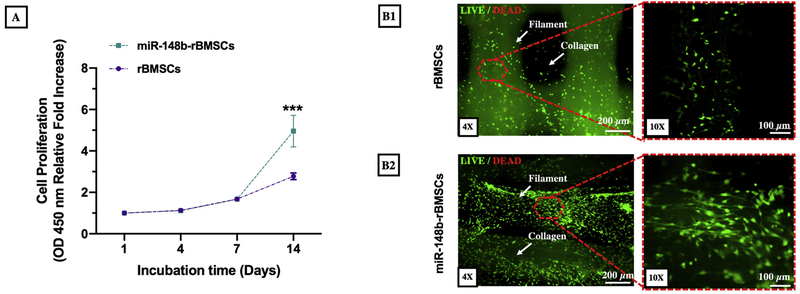

After the 3D printing process, miR-148b-transfected rBMSCs were encapsulated in collagen, which was subsequently injected into 3D printed frames infilling the pores. Proliferation of rBMSCs (with and without miR-148b transfection) in hybrid scaffolds were assessed using a CCK-8 assay performed on Days 1, 4, 7, and 14. As shown in Fig. 3A, miR-148b transfection did not exhibit a statistically significant effect on cell proliferation for the first week of culture period, where transfection and photo-activation processes did not induce any major inhibition on the proliferation of rBMSCs. However, the proliferation rate of miR-148b-transfected rBMSCs significantly increased compared to rBMSCs after 14 days of incubation (p = 0.000). Fig. 3B1 and B2 demonstrate fluorescent images of rBMSCs and miR-148b-transfected rBMSCs on 3D printed scaffolds after 14 days of incubation. Cells appeared mainly on filament surfaces of 3D frames for both groups; however, cells in miR-148b enriched scaffolds also spread within the collagen matrix throughout the entire porous structure, which is highly desirable for cells to deposit their own ECM within the pores.

Fig. 3.

Cell proliferation of rBMSCs (with and without miR-148b transfection) in 3D printed hybrid scaffolds. A) Optical density values of rBMSCs and miR-148b-transfected rBMSCs obtained from CCK-8 assay, (B1) fluorescent images of rBMSCs and (B2) miR-148b-transfected rBMSCs in 3D printed scaffolds after 14 days of incubation (n = 6).

3.4. Osteogenic differentiation of rBMSCs in 3D printed hybrid scaffolds

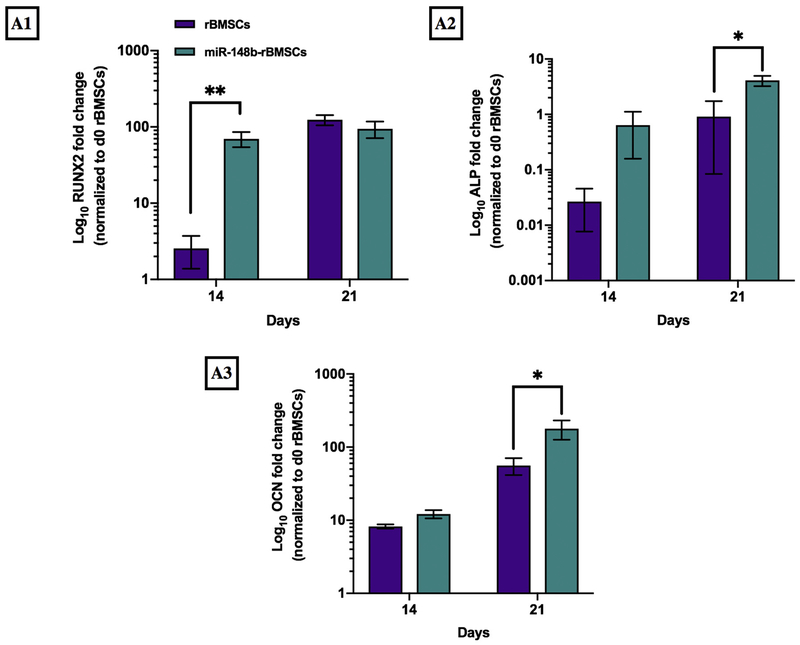

In order to understand how miR-148b enriched scaffolds enhanced bone formation as an ex situ delivery template in vitro, we monitored the gene expression levels of early-stage (RUNX2 and ALP) and late-stage (OCN) osteogenic differentiation markers after 14 and 21 days of culture. Quantified gene expression levels of rBMSCs and miR-148b transfected rBMSCs were demonstrated in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Measurement of gene expression levels of (A1) RUNX2, (A2) ALP and (A3) OCN on Days 14 and 21 for rBMSCs and miR-148b-transfected rBMSCs (*p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01, n = 6).

After 14 days of culture in growth media, expression levels of early-stage osteogenic differentiation markers of RUNX2 significantly upregulated for miR-148b-treated rBMSCs compared to the untreated rBMSCs (p = 0.006) (Fig. 4A1). However, there was no difference in the gene expression level of RUNX2 on Day 21. Moreover, elevated levels of ALP gene were noticeable for the miR-148b group on Day 14, which became significant on Day 21 with respect to untreated rBMSCs (p = 0.028) (Fig. 4A2). The expression level of OCN marker increased for both groups over time. However, it was observed that miR-148b transfected rBMSCs exhibited 1.5-fold (times) greater OCN expression compared to the untreated group on Day 14 and reached a significant level (3 folds) on Day 21 (p = 0.044) (Fig. 4A3).

Immunofluorescence images of rBMSCs and miR-148b transfected rBMSCs in hybrid scaffolds were demonstrated in Fig. 5. Results confirmed that both groups took up the differentiation specific markers, including RUNX2 and BSP, indicating that cells underwent osteogenic differentiation. However, miR-148b-transfected rBMSCs group exhibited significant expression and homogenous distribution of RUNX2 and BSP compared to the untreated group (p = 0.000) (Fig. 5A–B).

Fig. 5.

Confocal images of (A1–A2) RUNX2, (B1–B2) BSP, (C) DAPI and F-actin staining for rBMSCs and miR-148b-transfected rBMSCs on 3D printed scaffolds after 14 days of incubation. Green and blue staining represent RUNX2 and BSP expressions of cells, respectively. DAPI and F-Actin staining indicate nucleus and cytoskeleton organization of cells, respectively. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3.5. Bone regeneration in critical-sized rat calvarial defects

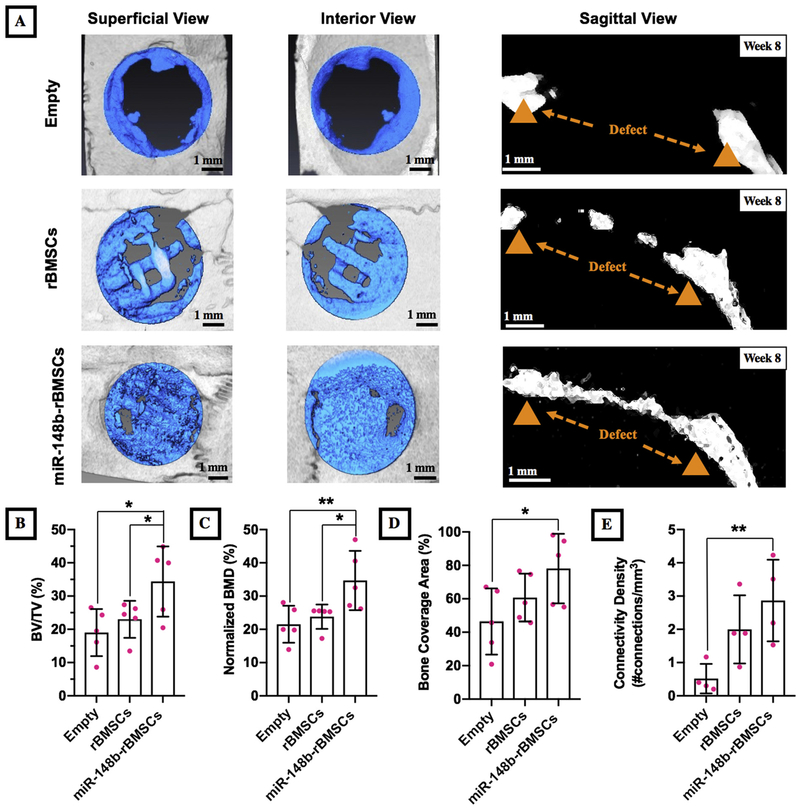

After 8 weeks of implantation, bone healing was assessed by μCT for defects for three groups and images were presented in Fig. 6A. Bone repair was limited for empty group that was mainly observed at the edges of the surrounding defect without forming any bridges across the defect region. In both groups of implants, newly mineralized bone formation was observed; however, bone regeneration was limited for the rBMSCs group, which was mainly observed at the edges of the defects bridging through filaments. However, there was a remarkable increase in bone regeneration for the miR-148b-transfected rBMSCs, which nearly filled the entire defect. As shown in the sagittal views of defects, miR-148b transfected rBMSCs bridged the bone gap along the defect center compared to the untreated group. Quantitative analysis derived from μCT scans also confirmed that BV/TV (%) of miR-148b transfected group was calculated to be significantly higher compared to empty groups (p = 0.01) and 1.5-fold times higher than that of the untreated group (p = 0.044) (Fig. 6B). Furthermore, miR-148b transfected group yielded 34.7 ± 8.9% normalized BMD, which was significantly higher than that of the non-transfected group (p = 0.021) (23.8 ± 3.67%) and the empty group (p = 0.007) (21.54 ± 5.58%) (Fig. 6C). Bone coverage area for the defects in the implantation site for miR-148b, untreated, and empty groups were measured to be 78.1 ± 20.8%, 60.7 ± 14.3% and 46.43 ± 19.77%, respectively, which resulted in significant improvement for the miR-148b treated group compared to the empty group (p = 0.019). (Fig. 6D). Connectivity density, in other words, the total number of connections per volume, for the miR-148b, untreated, and empty groups were determined to be 2.86 ± 1.23,1.99 ± 1.03 and 0.5 ± 0.4, respectively (Fig. 6E). The connectivity density (p = 0.007) for the miR-148b treated group was significantly higher compared to the empty group (Fig. 6E).

Fig. 6.

Bone healing in critical-sized (5 mm) calvarial defects. (A) μCT images of three groups including empty defect and calvarial defects implanted with 3D printed hybrid scaffolds (with and without miR-148b transfection) with their superficial, interior and sagittal views, (B) BV/TV (%), (C) relative BMD (%), (D) bone coverage area (%) and (E) connectivity density results obtained from the quantitative analysis of μCT scanning. (*p < 0.05 and p < 0.01, n = 5).

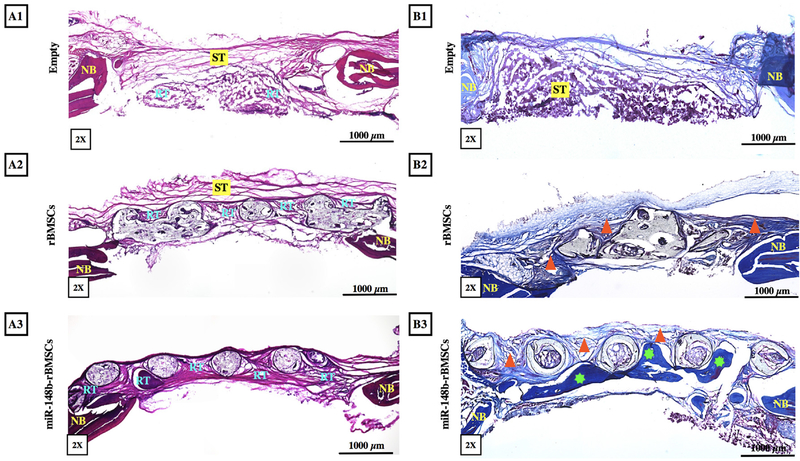

H&E Staining of explant sections confirmed that fibrous connective soft tissue (ST) was formed in empty defects with very limited regenerated bone tissue (RT) and rBMSCs-only group primarily displayed fibrous connective ST and limited but more compact newly RT located around filaments (Fig. 7A1–A2). In contrast, denser bone tissue was formed in miR-148b enriched scaffolds with distinguishable dark purple staining, particularly around the filaments, bridging the native calvarium with improved defect closure (Fig. 7A3). In addition, degradation of frame was also observed, where cells were visible inside the frame material in 20× H&E images. Masson’s Trichrome staining of sectioned defects indicated that empty group (Fig. 7B1) had mainly soft tissue formation, where no calcification was observed in the defect area. On the other hand, rBMSCs group had immature bone formation as highlighted by triangles in Fig. 7B2. The miR-148b-treated group had considerable bone formation (highlighted by stars in Fig. 7B3) compared the other groups. In particular, a notable amount of mature bone formation was observed around the filaments bridging the defect.

Fig. 7.

Histological evaluation of bone regeneration. (A1–A3) H&E and (B1–B3) Masson’s Trichrome staining of sections for empty defect, rBMSCs and miR-148btransfected rBMSCs, respectively, at Week 8 post implantation (ST: soft tissue, NB: native bone, RT: regenerated bone tissue, triangle indicates immature bone, star indicates mature bone formation).

Immuno images of histological sections from explants were presented in Fig. 8. RUNX2 and BSP were weakly expressed in the empty group (Fig. 8A). Compared to other groups, RUNX2 and BSP were strongly expressed for the miR-148b-treated group, where BSP was primarily observed on the lateral side of filaments (Fig. 8C).

Fig. 8.

Immunohistochemical staining of sectioned rat calvarial defects with groups of (A) empty defect, (B) rBMSCs, and (C) miR-148b-transfected rBMSCs at Week 8 post implantation. DAPI (blue) and F-Actin (red) staining indicate nucleus and cytoskeleton organization of cells, respectively. Green and blue staining represent RUNX2 and BSP expressions of cells, respectively. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

4. Discussion

miRNA-based therapeutic approaches have recently gained significant attention as committed progenitors retain their stem-like properties of reduced immunogenicity, cytokine production and migratory capability while being committed to differentiation pathway [47]. Their use to locally deliver therapeutics has attracted much attention since many distinct vehicles have been tuned to serve the purpose of miRNA delivery both in situ and ex situ [8]. The goal of this study was to engineer a 3D hybrid system with controlled architecture for ex situ delivery of miR148b in a nano-formulated vehicle, which has great potential to facilitate complete regeneration of critical-sized defects for craniofacial reconstruction.

Advantages to using silver nanoparticle delivery systems include facile surface conjugation chemistry of the miRNA mimic molecule using the robust thiolate bonding to silver surfaces [32]. Additionally, the ability to couple near field energy and re-emit in the form of photonic or photothermal emission provides a robust mechanism for decaging of the molecule. This occurs as a result of the nitrobenzyl photocleavable linker absorption in the UV region overlapping with the SNP plasmon resonance facilitating its photo-cleavage [18,42]. Thus, photoactivated-miR-148b delivery conjugates were used as a transfection vehicle for rBMSCs (Fig. 1A). miR-148b was inactive while tethered to the nanoparticle and conjugated via a photo-cleavable linker. Photoactivation and release of the miRNA mimic can occur over a range of wavelengths from 350 to 450 nm in order to release it from the nanoparticle surface after transfection [42]. The transfection efficiency data (~56%) confirmed the potential of photo-activated nano-particles as an effective miRNA mimic delivery tool for rBMSCs (Fig. 1B–C).

The composite ink (PCL/PLGA/HAp) was used to fabricate 3D printed scaffolds by melt extrusion process, which generated 3D structures with controlled porous architecture providing requisite space for collagen injection, gene delivery and cell proliferation [48]. Conventional scaffolds used in bone regeneration generally possess interconnected porous architecture (with around 300 μm pores) to facilitate bone regeneration and vascularization as well as ECM deposition and organization [49]. In this study, 3D printed scaffolds were designed as highly porous structures (with an average pore size of ~700 μm) in order to enable the loading of high number of cells laden in collagen compared to conventional 3D printed scaffolds, where cells can only be loaded on the surface of filaments. In our design, pores were infilled with collagen, which is also a porous hydrogel promoting high cell viability as reported in our recent study [38]. Despite the 3D printed frames structurally supported the hybrid scaffold to facilitate sufficient mechanical strength [50] and were reinforced with osteoinductive hydroxyapatite particles to induce osteogenesis for successful bone restoration [33], the pore size in the presented hybrid scaffolds was designed to be larger (~700 μm) to generate sufficient gaps between filaments for cellular infilling enabling gene delivery. Mechanical test results indicated that the incorporation of collagen gel reinforced the mechanical properties of 3D printed frames as collagen crosslinked and formed thicker fibers filling spaces between filaments inducing better mechanical properties [51,52]. Previous reports demonstrate differences between the 3D miRNA-activated systems in comparison to monolayer [8,53]. Thus, the common denominator of this work was to enable a controlled 3D structure for the delivery of miRNA, as the cells were transfected ex situ prior to scaffold seeding.

It was interesting to evaluate cell proliferation in 3D printed hybrid scaffolds since previously published studies indicated progression of in vitro osteogenesis followed by decreased cellular proliferation on 2D cultures due to miRNA transfection [54,55]. This study showed that there was no significant inhibition of rBMSC proliferation after miR-148b transfection compared to non-transfected rBMSCs, which might occur due to the effect of 3D hybrid scaffolds in triggering cell proliferation in both groups and also providing increased surface area for cell attachment, migration and spreading [56,57].

For improved control over differentiation due to gene transfection with miRNA, our previous study demonstrated the upregulation of early and late stage osteogenic markers [18]. In this study, osteogenic potential of rBMSCs in 3D printed scaffolds were highlighted in terms of osteogenic gene expressions. Significantly upregulated RUNX2 levels for the miR-148b group indicates early stage differentiation during bone remodeling [58]. A significant enhancement of cellular differentiation of the miR-148b-treated group was confirmed by unregulated OCN and ALP expression, and the results were in agreement with previous studies [28,31]. Formation of bone involves a complex series of events including proliferation and differentiation of osteo-progenitors, and early and late stage osteogenesis can be defined by immunochemical markers such as RUNX2 and BSP [59]. In this work, rBMSCs-only group expressed osteogenic markers to a certain extent. This might be due to the presence of HAp and collagen type-I in the scaffold frame and filler matrix, respectively, as HA is osteoconductive and collagen type-I is a primary component of native bone ECM [33]. Previous in vitro studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of miR-148b in osteogenic differentiation from various osteoprogenitors by promoting the target genes for early- and late-stage osteogenesis [18,60].

Healing a critical-sized calvarial defect remains an unsolved problem due to the limited bone regeneration without intervention [61]. Rat calvarial defect model is a clinically relevant and well-published model for evaluating bone regeneration [62]. In this study, we present a novel strategy for miRNA mimic delivery, which was also evaluated for its ability to promote bone regeneration in rat calvarial defects. Calvarial defects were partially repaired with 3D printed scaffolds and the empty defect had minimal healing; however, the ex situ miR-148b delivery system induced near-complete closure of defects. It is likely that miR148b-transfected cells contributed to the bone repair by direct differentiation into osteogenic lineage. Moreover, it should be mentioned that miR-148b transfected cells may have secreted trophic signals recruiting surrounding endogenous cells and influencing bone repair process. Previous studies indicated the functional role of miRNAs on the signaling pathways of osteogenic differentiation during bone formation [27,63–65]. However, miR-148b targeting genes in osteogenesis regulatory circuits with the exact molecular mechanism still remain unknown. It should be noted that miR-148b needs more experimental validation in order to reveal its role in progenitor cells osteogenesis and contributions in different stages of bone regeneration. In this study, we preferred to evaluate bone regeneration in 8 weeks as our previous study revealed that such time point was sufficient to observe substantial degradation in the frame material [33]; however, further studies would be essential in order to further understand time-dependent bone healing in the presented 3D printed platform.

The results of this study demonstrate that miR-148b enriched scaffolds promoted better bone regeneration with significant bone ECM deposition, which might be due to the upregulated osteogenic differentiation of miR-148b-transfected rBMSCs compared to the untreated group. Together, these data indicate that miR-148b enriched scaffolds increased osteogenesis of differentiating rBMSCs and promoting new bone formation. However, future studies may also focus on investigating the influence of other factors, such as but not limited to in vivo degradation, miR-148b concentration, and cell density, on promoting calvarial defect repair.

5. Conclusions

Although delivery of stem/progenitor cells has been widely used in 3D printed or bioprinted constructs, differentiating these cells into target tissue-specific cell types is not trivial to control, which yields poor tissue regeneration. In this study, we developed a novel ex situ miRNA delivery system through the use of collagen-infilled 3D printed hybrid scaffolds. The results demonstrated the ability of miR-148b enriched scaffolds in effectively modulating osteogenic differentiation of rBMSCs and improving bone regeneration in critical-sized calvarial bone defects, which provided preclinical data supporting the potential application of 3D printed scaffolds with miR-148b as an option for future critical-sized bone defects on large animals before translating into clinics. For future work, we will aim to facilitate the differentiation of multiple groups of progenitors towards osteogenic and endotheliogenic lineages in order to induce bone regeneration and vascularization in tandem, respectively.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by Osteology Foundation (15-042), International Team for Implantology (1275_2017), and National Science Foundation (1600118) and National Institutes of Health (RDE024790A). Dr. R. Seda Tigli Aydin acknowledges a grant provided by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey (TUBITAK) (BIDEP 2219). The authors are also thankful to The Huck Institute of The Life Sciences and Materials Research Institute at the Pennsylvania State University in providing support for the core facility use.

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interest

The authors confirm that there are no known conflicts of interest associated with this publication and there has been no significant financial support for this work that could have influenced its outcome.

References

- [1].Ozbolat IT, Moncal KK, Gudapati H, Evaluation of bioprinter technologies, Addit. Manuf 13 (2017) 179–200 Supplement C. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Datta P, Ozbolat V, Ayan B, Dhawan A, Ozbolat IT, Bone tissue bioprinting for craniofacial reconstruction, Biotechnol. Bioeng 114 (11) (2017) 2424–2431 November. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Shao H, et al. , 3D printing magnesium-doped wollastonite/β-TCP bioceramics scaffolds with high strength and adjustable degradation, J. Eur. Ceram. Soc 36 (6) (2016) 1495–1503. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Sun M, et al. , Systematical evaluation of mechanically strong 3D printed diluted magnesium doping Wollastonite scaffolds on osteogenic capacity in rabbit calvarial defects, Sci. Rep 6 (2016) 34029 September. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Shao H, et al. , 3D robocasting magnesium-doped wollastonite/TCP bioceramic scaffolds with improved bone regeneration capacity in critical sized calvarial defects, J. Mater. Chem. B 5 (16) (2017) 2941–2951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Shao H XS, Ke X, Liu A, Sun M, He Y, Yang X, Fu J, Liu Y, Zhang L, Yang G, Bone regeneration in 3D printing bioactive ceramic scaffolds with improved tissue/material interface pore architecture in thin-wall bone defect, Biofabrication 9 (2) (2017) 025003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ozbolat IT, 3D Bioprinting: Fundamentals, Principles and Applications, Academic Press is an imprint of Elsevier, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Curtin CM, Castaño IM, O’Brien FJ, Scaffold-based microRNA therapies in regenerative medicine and cancer, Adv. Healthc. Mater 7 (1) (2018) 1700695 January. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Maroulakos M, Kamperos G, Tayebi L, Halazonetis D, Ren Y, Applications of 3D printing on craniofacial bone repair: a systematic review, J. Dent 80 (2019) 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Szpalski C, Barr J, Wetterau M, Saadeh PB, Warren SM, Cranial bone defects: current and future strategies, Neurosurg. Focus FOC 29 (6) (2010) E8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Eppler SM, et al. , A target-mediated model to describe the pharmacokinetics and hemodynamic effects of recombinant human vascular endothelial growth factor in humans, Clin. Pharmacol. Ther 72 (1) (July 2002) 20–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ravnic DJ, et al. , Transplantation of bioprinted tissues and organs: technical and clinical challenges and future perspectives, Ann. Surg 266 (1) (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Leberfinger AN, Moncal KK, Ravnic DJ, Ozbolat IT, Emerich DF, Orive G (Eds.), 3D Printing for Cell Therapy Applications BT - Cell Therapy: Current Status and Future Directions, Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2017, pp. 227–248. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Cai X, et al. , Influence of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells pre-implantation differentiation approach on periodontal regeneration in vivo, J. Clin. Periodontol 42 (4) (April 2015) 380–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Kuhn LT, et al. , Developmental-like bone regeneration by human embryonic stem cell-derived mesenchymal cells, Tissue Eng. Part A 20 (1.2) (2013) 365–377. August. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Heller M, et al. , Materials and scaffolds in medical 3D printing and bioprinting in the context of bone regeneration, Int. J. Comput. Dent 19 (4) (2016) 301–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Qureshi AT, et al. , Photoactivated miR-148b-nanoparticle conjugates improve closure of critical size mouse calvarial defects, Acta Biomater. 12 (2015) 166–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Qureshi AT, Monroe WT, Dasa V, Gimble JM, Hayes DJ, miR-148b-nanoparticle conjugates for light mediated osteogenesis of human adipose stromal/stem cells, Biomaterials 34 (31) (2013) 7799–7810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Verma IM, Gene therapy that works, Science (80-.) 341 (6148) (2013) 853–855, August. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Aagaard L, Rossi JJ, RNAi therapeutics: principles, prospects and challenges, Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev 59 (2) (2007) 75–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Xie J, et al. , Long-term, efficient inhibition of microRNA function in mice using rAAV vectors, Nat. Methods 9 (2012) 403 March. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Dalby B, et al. , Advanced transfection with Lipofectamine 2000 reagent: primary neurons, siRNA, and high-throughput applications, Methods 33 (2) (2004) 95–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Chiou G-Y, et al. , Cationic polyurethanes-short branch PEI-mediated delivery of Mir145 inhibited epithelial–mesenchymal transdifferentiation and cancer stem-like properties and in lung adenocarcinoma, J. Control. Release 159 (2) (2012) 240–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Burnett JC, Rossi JJ, RNA-based therapeutics: current progress and future prospects, Chem. Biol 19 (1) (2012) 60–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Luzi E, Marini F, Sala SC, Tognarini I, Galli G, Brandi ML, Osteogenic differentiation of human adipose tissue-derived stem cells is modulated by the miR-26a targeting of the SMAD1 transcription factor, J. Bone Miner. Res 23 (2) (2008) 287–295 February. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Mizuno Y, et al. , miR-125b inhibits osteoblastic differentiation by down-regulation of cell proliferation, Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 368 (2) (2008) 267–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Schoolmeesters A, et al. , Functional profiling reveals critical role for miRNA in differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells, PLoS One 4 (5) (2009) e5605 May. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Mariner PD, Johannesen E, Anseth KS, Manipulation of miRNA activity accelerates osteogenic differentiation of hMSCs in engineered 3D scaffolds, J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med 6 (4) (2012) 314–324. April. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Li K-C, Lo S-C, Sung L-Y, Liao Y-H, Chang Y-H, Hu Y-C, Improved calvarial bone repair by hASCs engineered with Cre/loxP-based baculovirus conferring prolonged BMP-2 and MiR-148b co-expression, J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med 11 (11) (2017) 3068–3077 November. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Cheng P, et al. , miR-148a regulates osteoclastogenesis by targeting V-maf musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene homolog B, J. Bone Miner. Res 28 (5) (2013) 1180–1190 May. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Liao Y-H, et al. , Osteogenic differentiation of adipose-derived stem cells and calvarial defect repair using baculovirus-mediated co-expression of BMP-2 and miR-148b, Biomaterials 35 (18) (2014) 4901–4910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Qureshi AT, et al. , Biocompatible/bioabsorbable silver nanocomposite coatings, J. Appl. Polym. Sci 120 (5) (2011) 3042–3053 June. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Moncal KK, et al. , 3D printing of poly(ε-caprolactone)/poly (d,L-lactide-co-glycolide)/hydroxyapatite composite constructs for bone tissue engineering, J. Mater. Res 33 (14) (2018) 1972–1986 July. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Rajan N, Habermehl J, Coté M-F, Doillon CJ, Mantovani D, Preparation of ready-to-use, storable and reconstituted type I collagen from rat tail tendon for tissue engineering applications, Nat. Protoc 1 (6) (2006) 2753–2758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Ozbolat IT, Chen H, Yu Y, Development of ‘multi-arm bioprinter’ for hybrid biofabrication of tissue engineering constructs, Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf 30 (3) (2014) 295–304. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Jakus AE et al. , “Hyperelastic ‘bone’: a highly versatile, growth factor–free, osteoregenerative, scalable, and surgically friendly biomaterial,” Sci. Transl. Med, vol. 8, no. 358, p. 358ra127–358ra127, Sep. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Zhang L, Chan C, Isolation and enrichment of rat mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and separation of single-colony derived MSCs, J. Vis. Exp 37 (2010) 1852 March. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Moncal KK, Ozbolat V, Datta P, Heo DN, Ozbolat IT, Thermally-controlled extrusion-based bioprinting of collagen, J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med 30 (5) (2019) 55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD, Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method, Methods 25 (4) (2001) 402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Romano FL, Ambrosano GMB, de A. Magnani MBB, Nouer DF, Analysis of the coefficient of variation in shear and tensile bond strength tests, J. Appl. Oral Sci 13 (2005) 243–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Sawyer AA, et al. , The stimulation of healing within a rat calvarial defect by mPCL–TCP/collagen scaffolds loaded with rhBMP-2, Biomaterials 30 (13) (2009) 2479–2488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Kumal RR, et al. , Plasmon-enhanced photocleaving dynamics in colloidal microRNA-functionalized silver nanoparticles monitored with second harmonic generation, Langmuir 32 (40) (2016) 10394–10401 October. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Brown PK, Qureshi AT, Moll AN, Hayes DJ, Monroe WT, Silver nanoscale antisense drug delivery system for photoactivated gene silencing, ACS Nano 7 (4) (2013) 2948–2959. April. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Umadevi M, Fluorescence quenching by plasmonic silver nanoparticles, Surface Plasmon Enhanced, Coupled and Controlled Fluorescence (2017) 197–202 20-March-. [Google Scholar]

- [45].Dunn KW, Kamocka MM, McDonald JH, A practical guide to evaluating colocalization in biological microscopy, Am. J. Physiol. Physiol 300 (4) (January 2011) C723–C742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Depalle B, Qin Z, Shefelbine SJ, Buehler MJ, Influence of cross-link structure, density and mechanical properties in the mesoscale deformation mechanisms of collagen fibrils, J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater 52 (2015) 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].M. Valenti M, Dalle Carbonare L, & Mottes, “Role of microRNAs in progenitor cell commitment and osteogenic differentiation in health and disease (review),” Int. J. Mol. Med, vol. 41, no. 5, pp. 2441–2449, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Peng W, Datta P, Ayan B, Ozbolat V, Sosnoski D, Ozbolat IT, 3D bioprinting for drug discovery and development in pharmaceutics, Acta Biomater. 57 (Supplement C) (2017) 26–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Bose S, Vahabzadeh S, Bandyopadhyay A, Bone tissue engineering using 3D printing, Mater. Today 16 (12) (2013) 496–504. [Google Scholar]

- [50].Datta P, Barui A, Wu Y, Ozbolat V, Moncal KK, Ozbolat IT, Essential steps in bioprinting: from pre- to post-bioprinting, Biotechnol. Adv 36 (5) (2018) 1481–1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Garnero P, The contribution of collagen crosslinks to bone strength, Bonekey Rep 1 (2012) 182 September. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Yang Y, Kaufman LJ, Rheology and confocal reflectance microscopy as probes of mechanical properties and structure during collagen and collagen/hyaluronan self-assembly, Biophys. J 96 (4) (2009) 1566–1585 February. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Mencía Castaño I, Curtin CM, Duffy GP, O’Brien FJ, Next generation bone tissue engineering: non-viral miR-133a inhibition using collagen-nanohydroxyapatite scaffolds rapidly enhances osteogenesis, Sci. Rep 6 (2016) 27941 June. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Kim YJ, Bae SW, Yu SS, Bae YC, Jung JS, miR-196a regulates proliferation and osteogenic differentiation in mesenchymal stem cells derived from human adipose tissue, J. Bone Miner. Res 24 (5) (2009) 816–825 May. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Bauer TW GA, Muschler GF, Stevenson S, Bone graft materials : an overview of the basic science, Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res 371 (2000) 10–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Yu H-S, Won J-E, Jin G-Z, Kim H-W, Construction of mesenchymal stem cell–containing collagen gel with a macrochanneled polycaprolactone scaffold and the flow perfusion culturing for bone tissue engineering, Biores. Open Access 1 (3) (2012) 124–136 June. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Somaiah BGJC, Kumar A, Mawrie D, Sharma A, Patil SD, Bhattacharyya J, Swaminathan R, Collagen promotes higher adhesion, survival and proliferation of mesenchymal stem cells, PLoS One 10 (12) (2015) e0145068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Huang W, Yang S, Shao J, Li YP, Signaling and transcriptional regulation in osteoblast commitment and differentiation, Front. Biosci. a J. virtual Libr 12 (2007) 3068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Zhang X, Li Y, Chen YE, Chen J, Ma PX, Cell-free 3D scaffold with two-stage delivery of miRNA-26a to regenerate critical-sized bone defects, Nat. Commun 7 (2016) 10376 January. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Song W, Wu K, Yan J, Zhang Y, Zhao L, MiR-148b laden titanium implant promoting osteogenic differentiation of rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells, RSC Adv. 3 (28) (2013) 11292–11300. [Google Scholar]

- [61].Cameron JA, Milner DJ, Lee JS, Cheng J, Fang NX, Jasiuk IM, Heber-Katz E, Stocum DL (Eds.), Employing the Biology of Successful Fracture Repair to Heal Critical Size Bone Defects BT - New Perspectives in Regeneration, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2013, pp. 113–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Spicer PP, Kretlow JD, Young S, Jansen JA, Kasper FK, Mikos AG, Evaluation of bone regeneration using the rat critical size calvarial defect, Nat. Protoc 7 (2012) 1918 September. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Li JB, Z, Hassan MQ, Jafferji M, Aqeilan RI, Garzon R, Croce CM, van Wijnen AJ, Stein JL, Stein GS, Lian, Biological functions of miR-29b contribute to positive regulation of osteoblast differentiation, ournal Biol. Chem 284 (25) (2009) 15676–15684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Suh JS, Lee JY, Choi YS, Chong PC, Park YJ, Peptide-mediated intracellular delivery of miRNA-29b for osteogenic stem cell differentiation, Biomaterials 34 (17) (2013) 4347–4359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Zhang W-B, Zhong W-J, Wang L, A signal-amplification circuit between miR-218 and Wnt/β-catenin signal promotes human adipose tissue-derived stem cells osteogenic differentiation, Bone 58 (2014) 59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]