Abstract

Objective

To investigate the variation in severe neonatal morbidity among very preterm (VPT) infants across European regions and whether morbidity rates are higher in regions with low compared with high mortality rates.

Design

Area-based cohort study of all births before 32 weeks of gestational age.

Setting

16 regions in 11 European countries in 2011/2012.

Patients

Survivors to discharge from neonatal care (n=6422).

Main outcome measures

Severe neonatal morbidity was defined as intraventricular haemorrhage grades III and IV, cystic periventricular leukomalacia, surgical necrotizing enterocolitis and retinopathy of prematurity grades ≥3. A secondary outcome included severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD), data available in 14 regions. Common definitions for neonatal morbidities were established before data abstraction from medical records. Regional severe neonatal morbidity rates were correlated with regional in-hospital mortality rates for live births after adjustment on maternal and neonatal characteristics.

Results

10.6% of survivors had a severe neonatal morbidity without severe BPD (regional range 6.4%–23.5%) and 13.8% including severe BPD (regional range 10.0%–23.5%). Adjusted inhospital mortality was 13.7% (regional range 8.4%–18.8%). Differences between regions remained significant after consideration of maternal and neonatal characteristics (P<0.001) and severe neonatal morbidity rates were not correlated with mortality rates (P=0.50).

Conclusion

Severe neonatal morbidity rates for VPT survivors varied widely across European regions and were independent of mortality rates.

Keywords: neonatology, mortality, epidemiology

What is already known on this topic?

Mortality rates for very preterm infants differ across European regions.

Morbidity rates may vary, but cross-regional comparisons are difficult because of unstandardised definitions and patient populations.

Mortality rates could affect the prevalence of severe neonatal morbidity among survivors if selection due to mortality affects patient case mix.

What this study adds?

This study confirms wide variations in neonatal morbidity across European regions using common definitions and patient populations.

Adjusting for maternal and neonatal characteristics reduces the variation between regions, but does not explain it.

A trade-off between mortality and morbidity rates at the regional level is not observed.

Introduction

Delivery before 32 weeks of gestation occurs in 1%–2% of births, contributing to significant mortality and morbidity.1 Advances in obstetric and neonatal care with more active management of these infants2 have increased survival in high-income countries.3–7 However, differences in mortality rates persist between and within countries,6 which may be partly explained by professional attitudes and decision-making regarding extremely preterm infants.6 Differences in maternal demographic and socioeconomic characteristics and the organisation and quality of obstetrical and neonatal care also contribute to mortality variations.8 9

Increased survival among very preterm infants may lead to higher risks of neonatal morbidity among survivors.10 11 Studies in the 1990s and 2000 provided conflicting reports; some found increasing neonatal morbidity as survival improved, while others reported no change.12 More recent studies show that improved survival did not result in increased rates of major neonatal morbidities, although rates of bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) may increase as more extremely preterm infants survive.13–18

While repeated studies by the same research groups enable standardised methodologies and comparable results over time,13–15 comparing morbidity across settings is more challenging, as morbidity has been measured using multiple definitions and study populations. Consequently, in contrast to mortality, few comparable data exist concerning geographical variation in morbidity in very preterm populations.19 20 Quantifying trade-offs between mortality and morbidity is relevant in a cross-country context, as improved neonatal survival may result in higher rates of impairment. Even if morbidity rates do not increase, the number of surviving high-risk infants will be greater when mortality is lower. This information is important for planning for health, social and educational services.

Using a contemporary prospective, population-based, multiregional cohort of live births <32 weeks gestation, we aimed to describe the variation in severe neonatal morbidity in Europe using standardised definitions, and to assess the potential trade-offs between survival and subsequent morbidity.

Methods

Study design

The ‘Effective Perinatal Intensive Care In Europe’ (EPICE) cohort is a prospective study of all stillbirths and live births between 22+0 and 31+6 weeks gestation in 19 regions in 11 European countries that together have >850 000 births annually: Belgium (Flanders), Denmark (Eastern Region), Estonia (entire country), France (Burgundy, Ile-de-France and the Northern region), Germany (Hesse and Saarland), Italy (Emilia-Romagna, Lazio and Marche), the Netherlands (Central and Eastern region), Poland (Wielkopolska), Portugal (Lisbon and Northern region), Sweden (greater Stockholm area) and the UK (East Midlands, Northern, and Yorkshire and Humber regions).21 The regions were included because of their geographical and organisational diversity, their ability to implement the study protocol and sample size considerations. Data were collected on births over varying 12-month periods between April 2011 and September 2012, except in French regions (6-month study period).

Data were extracted from medical records in obstetric and neonatal units using standardised pretested forms. Gestational age (GA) was defined as the best obstetric assessment based on information on last menstrual period and antenatal ultrasounds, which are part of routine obstetric care in all regions. The completeness of inclusions was cross-checked against delivery unit registers or routine regional statistics. Infants were followed until discharge from hospital to home or into long-term care, or death.

Study population

Three of the regions, Saarland (Germany), Marche (Italy) and Burgundy (France), were excluded because they had fewer than 100 eligible infants and therefore the number of severe morbid events was low. These regions had mortality and morbidity rates similar to the cohort average. For the analysis of mortality, we included 7438 live births after exclusion of stillbirths (n=1554), terminations of pregnancy (n=787) and severe congenital anomalies (n=123). Infants with severe congenital anomalies were excluded because of differences in screening and termination policies across the regions22 and consequent effects on mortality and morbidity. For the analysis of morbidity, our primary study population was infants discharged home or into long-term institutional care (n=6422). We also computed morbidity rates among neonatal admissions and inhospital deaths to allow comparison with other studies and to assess selection into our sample.

Definition of outcomes

Severe neonatal morbidity was defined as a composite measure of cystic periventricular leukomalacia (cPVL), intraventricular haemorrhage (IVH grades III and IV), surgical necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC requiring surgical treatment or peritoneal drainage) or retinopathy of prematurity (ROP≥stage 3). Severe BPD was need for oxygen with the fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) >30% or need for respiratory support (mechanical ventilation and non-invasive ventilation) at 36 weeks of postmenstrual age among survivors to ≥36 weeks.23 As data on FiO2 were not collected in two regions in the UK, we chose not to include severe BPD in our primary composite, but analysed it separately. Inhospital mortality was death after live birth before discharge from neonatal care, including labour ward deaths.

Covariables

Maternal, pregnancy and neonatal characteristics used to adjust for population differences are those that differ between regions, have an impact on mortality and morbidity and do not reflect obstetrical or neonatal care.9 These include maternal age; parity; multifetal pregnancy; pregnancy complications (pre-eclampsia, eclampsia/hemolysis elevated liver enzymes low platelet count), preterm premature rupture of membranes >12 hours; GA in completed weeks; small for gestational age (SGA) defined as a birth weight for GA≤10th percentile of intrauterine growth curves24; infant sex and presence of congenital anomalies. Congenital anomalies were those reportable to Eurocat,25 but not considered severe,9 as these were excluded. We also describe other perinatal care and health outcomes: delivery in a level III maternity unit using national definitions (yes/no), antenatal corticosteroids administration (any/no), mode of delivery (prelabour caesarean, intrapartum caesarean or vaginal delivery), 5 min Apgar score, initial respiratory support (none, nasal continuous positive airway pressure (nCPAP) or mechanical ventilation) and neonatal transport within 48 hours after birth.

Statistical analyses

We first described the prevalence of severe neonatal morbidity without and with severe BPD by region for surviving infants<32 weeks of GA and by GA subgroup (<28 weeks and 28–31 weeks of GA). Descriptive tables were also generated for neonatal admissions and inhospital deaths.

We then computed adjusted rates of mortality and severe neonatal morbidity (without and with severe BPD) taking into consideration maternal, pregnancy and infant characteristics. Adjusted rates were derived using logistic regressions following methods used to analyse mortality in the EPICE sample.9 For each region, the ratio of the observed to the expected number of events was calculated by using the estimated predicted probabilities and was then multiplied by the observed rate in the study population. We used the Wald test to assess the significance of region in unadjusted and adjusted models. The variation between regions was quantified through the SD of the mortality percentages for the regions, expressed as a coefficient of variation. To test associations between adjusted regional mortality and morbidity rates, we used Spearman rank correlations. We used a minimal adjustment model for each individual morbidity component, including only GA, because of the low number of cases.

Ethics

Ethical approval and informed parental consent (active or passive, depending on each participating country’s national legislation) for data collection were obtained in each study region. In the French regions, EPICE was carried out as part of the EPIPAGE 2 study, and parents had to consent to all parts of data collection, leading to 6.4% of total births for which consent could not be obtained.

Results

The mean GA was 28.4 weeks and mean birth weight was 1194 g (table 1); 31.5% were <10th percentile by intrauterine growth standards, while 31.2% were multiples; 86.3% received antenatal corticosteroids and 64.8% were born by caesarean section. Over one quarter of the sample had mothers 35 years of age or over and 56.2% had primparous mothers. The inhospital mortality rate was 13.6% for all infants<32 weeks, 33.5% for infants<28 weeks and 4.2% for infants 28 to 31 weeks.

Table 1.

Characteristics of live births and survivors to discharge from the neonatal unit

| Characteristics | Live births (n = 7438) |

Survivors to discharge (n = 6422) |

| Infant characteristics | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) |

| Gestational age | 28.4 (2.4) | 28.9 (2.0) |

| Birth weight, mean | 1194 (402) | 1255 (370) |

| Gestational age | % | % |

| <25 weeks | 9.2 | 3.7 |

| 25–27 weeks | 23.0 | 21.1 |

| 28–29 weeks | 24.9 | 26.9 |

| 30–31 weeks | 42.9 | 48.3 |

| Male | 54.3 | 53.9 |

| Multiple pregnancy | 31.2 | 31.7 |

| SGA* | ||

| <3rd percentile | 20.2 | 20.2 |

| 3–<10th percentile | 11.4 | 11.7 |

| ≥10th percentile | 68.4 | 68.1 |

| Apgar score at 5 min | ||

| <4 | 6.6 | 2.5 |

| 4–6 | 13.6 | 12.4 |

| ≥7 | 79.9 | 85.1 |

| Congenital anomaly† | 7.1 | 7.3 |

| Maternal and pregnancy characteristics | ||

| Maternal age | ||

| <35 years | 73.9 | 73.6 |

| 35 years | 26.1 | 26.4 |

| Parity | ||

| Nulliparous | 56.2 | 56.8 |

| Multiparous | 43.8 | 43.2 |

| PPROM | 25.1 | 25.0 |

| Pre-eclampsia/eclampsia/HELLP | 14.9 | 15.7 |

| Healthcare and management | ||

| Any antenatal steroids | 86.3 | 89.2 |

| Delivery in level III unit | 77.9 | 78.0 |

| Neonatal transport | 11.3 | 11.0 |

| Type of delivery | ||

| Prelabour caesarean | 39.9 | 41.8 |

| Intrapartum caesarean | 24.9 | 25.9 |

| Vaginal delivery | 35.2 | 32.4 |

| Initial respiratory management | ||

| None | 15.4 | 12.4 |

| nCPAP | 41.4 | 46.3 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 43.2 | 41.2 |

*Small for gestational age using intrauterine references.

†Congenital anomalies reportable to Eurocat, but not severe. Cases with severe anomalies were excluded.

HELLP, hemolysis elevated liver enzymes low platelet count; PPROM, preterm premature rupture of membrane.

Severe morbidity rates by GA groups

Overall, 10.6% of survivors had one or more severe neonatal morbidities without severe BPD and 13.8% had severe morbidity when severe BPD was included (table 2A). Severe NEC was the least prevalent of the morbidities (1.9%), followed by cPVL (3.2%), ROP≥stage3 (3.7%), IVH grades III and IV (3.9%) and severe BPD (5.5%). For morbidity without BPD, the regional range was from <8% in Ile-de-France, the Northern region in France and Sweden (greater Stockholm area), to 23.5% in Poland (Wielkopolska).

Table 2A.

Severe neonatal morbidity among very preterm infants born before 32 weeks of gestation surviving to discharge in 16 European regions

| IVH grade III/IV | cPVL | ROP stage 3+ | Severe NEC | Severe morbidity no BPD | Severe BPD | Severe morbidity with severe BPD | |

| n/N (%) | n/N (%) | n/N (%) | n/N (%) | n/N (%) | n/N (%) | n/N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All regions | 250/6333 (3.9) | 203/6350 (3.2) | 236/6308 (3.7) | 119/6422 (1.9) | 663/6238 (10.6) | 278/5039 (5.5) | 716/5173 (13.8) |

| Belgium: Flanders | 17/620 (2.7) | 21/645 (3.3) | 24/637 (3.8) | 8/651 (1.2) | 61/604 (10.1) | 31/643 (4.8) | 84/599 (14.0) |

| Denmark: Eastern | 9/276 (3.3) | 4/277 (1.4) | 9/276 (3.3) | 6/286 (2.1) | 24/268 (9.0) | 33/267 (12.4) | 50/255 (19.6) |

| Estonia | 4/140 (2.9) | 8/140 (5.7) | 12/140 (8.6) | 4/140 (2.9) | 21/140 (15.0) | 5/140 (3.6) | 24/140 (17.1) |

| France: Northern | 6/275 (2.2) | 9/275 (3.3) | 5/267 (1.9) | 2/275 (0.7) | 21/267 (7.9) | 20/244 (8.2) | 37/246 (15.0) |

| France: Ile-de-France | 31/743 (4.2) | 16/746 (2.1) | 2/724 (0.3) | 1/746 (0.1) | 46/722 (6.4) | 28/694 (4.0) | 72/692 (10.4) |

| Germany: Hesse | 12/526 (2.3) | 11/524 (2.1) | 23/524 (4.4) | 15/528 (2.8) | 51/525 (9.7) | 27/524 (5.2) | 67/524 (12.8) |

| Italy: Lazio | 17/469 (3.6) | 16/469 (3.4) | 24/461 (5.2) | 6/472 (1.3) | 54/465 (11.6) | 16/458 (3.5) | 63/461 (13.7) |

| Italy: Emilia | 15/389 (3.9) | 9/389 (2.3) | 18/391 (4.6) | 6/391 (1.5) | 39/389 (10.0) | 17/386 (4.4) | 46/386 (11.9) |

| The Netherlands: East-Central | 15/326 (4.6) | 9/324 (2.8) | 4/326 (1.2) | 6/329 (1.8) | 30/326 (9.2) | 24/327 (7.3) | 47/326 (14.4) |

| Poland: Wielkopolska | 21/235 (8.9) | 22/235 (9.4) | 24/234 (10.3) | 11/236 (4.7) | 55/234 (23.5) | 3/236 (1.3) | 55/234 (23.5) |

| Portugal: Northern | 12/246 (4.9) | 12/246 (4.9) | 14/246 (5.7) | 4/246 (1.6) | 28/246 (11.4) | 13/246 (5.3) | 36/246 (14.6) |

| Portugal: Lisbon | 16/360 (4.4) | 12/360 (3.3) | 14/359 (3.9) | 7/360 (1.9) | 41/359 (11.4) | 18/359 (5.0) | 49/359 (13.6) |

| UK: Northern | 12/347 (3.5) | 5/349 (1.4) | 16/351 (4.6) | 14/380 (3.7) | 37/330 (11.2) | 29/283 (10.2) | 57/270 (21.1) |

| UK: East Midlands | 28/507 (5.5) | 18/502 (3.6) | 14/507 (2.8) | 12/507 (2.4) | 58/502 (11.6) | NA | NA |

| UK: Yorkshire and Humber | 27/638 (4.2) | 25/633 (3.9) | 25/637 (3.9) | 14/638 (2.2) | 80/633 (12.6) | NA | NA |

| Sweden: Stockholm | 8/236 (3.4) | 6/236 (2.5) | 8/228 (3.5) | 3/237 (1.3) | 17/228 (7.5) | 14/232 (6.0) | 29/228 (12.7) |

BPD, bronchopulmonary dysplasia; cPVL, cystic periventricular leukomalacia; IVH, intraventricular haemorrhage; NEC, necrotizing enterocolitis; ROP, retinopathy of prematurity.

For infants born before 28 weeks of GA, severe neonatal morbidity rates without and with severe BPD were 26.8%, and 36.9%, respectively (table 2B). Severe BPD, ROP≥stage 3 and IVH grade III/IV were the most prevalent morbidities. Variation between regions was wide (16% to >40%) for the composite variables. For infants 28 to 31 weeks, morbidity rates were 5.3% without severe BPD and 7.0% with severe BPD (table 2C); IVH grades III and IV, cPVL and severe BPD were the most prevalent morbidities. Differences between regions were significant (P<0.001) across both subpopulations and composite indicators.

Table 2B.

Severe neonatal morbidity among very preterm infants born before 28 weeks of GA surviving to discharge in 16 European regions

| IVH grade III/IV | cPVL | ROP stage 3+ | Severe NEC | Severe morbidity no BPD | Severe BPD | Severe morbidity with severe BPD | |

| n/N (%) | n/N (%) | n/N (%) | n/N (%) | n/N (%) | n/N (%) | n/N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All regions | 158/1566 (10.1) | 90/1570 (5.7) | 198/1565 (12.7) | 77/1593 (4.8) | 415/1550 (26.8) | 195/1232 (15.8) | 457/1240 (36.9) |

| Belgium: Flanders | 8/120 (6.7) | 6/126 (4.8) | 21/127 (16.5) | 7/127 (5.5) | 37/122 (30.3) | 19/123 (15.4) | 50/120 (41.7) |

| Denmark: Eastern | 4/85 (4.7) | 2/85 (2.4) | 6/84 (7.1) | 4/87 (4.6) | 13/82 (15.9) | 27/77 (35.1) | 33/75 (44/0) |

| Estonia | 2/39 (5.1) | 3/39 (7.7) | 11/39 (28.2) | 3/39 (7.7) | 14/39 (35.9) | 5/39 (12.8) | 17/39 (43.6) |

| France: Northern | 2/77 (2.6) | 5/77 (6.5) | 4/75 (5.3) | 2/77 (2.6) | 13/75 (17.3) | 10/67 (14.9) | 20/69 (29.0) |

| France: Ile-de-France | 20/175 (11.4) | 8/176 (4.5) | 2/174 (1.1) | 0/176 (0.0) | 28/173 (16.2) | 19/160 (11.9) | 45/161 (28.0) |

| Germany: Hesse | 9/156 (5.8) | 7/156 (4.5) | 21/154 (13.6) | 14/157 (8.9) | 41/155 (26.5) | 22/154 (14.3) | 54/154 (35.1) |

| Italy: Lazio | 9/98 (9.2) | 4/98 (4.1) | 18/96 (18.8) | 3/98 (3.1) | 30/97 (30.9) | 9/94 (9.6) | 34/96 (35.4) |

| Italy: Emilia | 12/102 (11.8) | 6/102 (5.9) | 18/102 (17.6) | 2/102 (2.0) | 29/102 (28.4) | 14/98 (14.3) | 35/100 (35.0) |

| The Netherlands: East-Central | 10/87 (11.5) | 4/87 (4.6) | 3/87 (3.4) | 4/88 (4.5) | 17/87 (19.5) | 19/87 (21.8) | 30/87 (34.5) |

| Poland: Wielkopolska | 13/63 (20.6) | 6/62 (9.7) | 17/62 (27.4) | 3/63 (4.8) | 27/62 (43.5) | 2/63 (3.2) | 27/62 (43.5) |

| Portugal: Northern | 6/65 (9.2) | 7/65 (10.8) | 10/65 (15.4) | 2/65 (3.1) | 16/65 (24.6) | 7/65 (10.8) | 20/65 (30.8) |

| Portugal: Lisbon | 10/91 (11.0) | 7/91 (7.7) | 13/91 (14.3) | 2/91 (2.2) | 26/91 (28.6) | 14/91 (15.4) | 31/91 (34.1) |

| UK: Northern | 9/88 (10.2) | 5/93 (5.4) | 13/93 (14.0) | 10/103 (9.7) | 28/89 (31.5) | 20/54 (37.0) | 39/60 (65) |

| UK: East Midlands | 21/108 (19.4) | 8/106 (7.5) | 13/108 (12.0) | 10/108 (9.3) | 40/106 (37.7) | NA | NA |

| UK: Yorkshire and Humber | 16/149 (10.7) | 7/144 (4.9) | 20/148 (13.5) | 8/149 (5.4) | 41/144 (28.5) | NA | NA |

| Sweden: Stockholm | 7/63 (11.1) | 5/63 (7.9) | 8/60 (13.3) | 3/63 (4.8) | 15/61 (24.6) | 8/60 (13.3) | 22/61 (36.1) |

BPD, bronchopulmonary dysplasia; cPVL, cystic periventricular leukomalacia; GA, gestational age; IVH, intraventricular haemorrhage; NEC, necrotizing enterocolitis; ROP, retinopathy of prematurity.

Table 2C.

Severe neonatal morbidity among very preterm infants born between 28 and 31 weeks of GA surviving to discharge in 16 European regions

| IVH grade III/IV | cPVL | ROP stage 3+ | Severe NEC | Severe morbidity no BPD | Severe BPD | Severe morbidity with severe BPD | |

| n/N (%) | n/N (%) | n/N (%) | n/N (%) | n/N (%) | n/N (%) | n/N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All regions | 92/4767 (1.9) | 113/4780 (2.4) | 38/4743 (0.8) | 42/4829 (0.9) | 248/4688 (5.3) | 83/3807 (2.2) | 259/3726 (7.0) |

| Belgium: Flanders | 9/500 (1.8) | 15/519 (2.9) | 3/510 (0.6) | 1/524 (0.2) | 24/482 (5.0) | 12/520 (2.3) | 34/479 (7.1) |

| Denmark: Eastern | 5/191 (2.6) | 2/192 (1.0) | 3/192 (1.6) | 2/199 (1.0) | 11/186 (5.9) | 6/190 (3.2) | 17/180 (9.4) |

| Estonia | 2/101 (2.0) | 5/101 (5.0) | 1/101 (1.0) | 1/101 (1.0) | 7/101 (6.9) | 0/101 (0.0) | 7/101 (6.9) |

| France: Northern | 4/198 (2) | 4/198 (2.0) | 1/192 (0.5) | 0/198 (0.0) | 8/192 (4.2) | 10/177 (5.6) | 17/177 (9.6) |

| France: Ile-de-France | 11/568 (1.9) | 8/570 (1.4) | 0/550 (0.0) | 1/570 (0.2) | 18/549 (3.3) | 9/534 (1.7) | 27/531 (5.1) |

| Germany: Hesse | 3/370 (0.8) | 4/368 (1.1) | 2/370 (0.5) | 1/371 (0.3) | 10/370 (2.7) | 5/370 (1.4) | 13/370 (3.5) |

| Italy: Lazio | 8/371 (2.2) | 12/371 (3.2) | 6/365 (1.6) | 3/374 (0.8) | 24/368 (6.5) | 7/364 (1.9) | 29/365 (7.9) |

| Italy: Emilia | 3/287 (1.0) | 3/287 (1.0) | 0/289 (0.0) | 4/289 (1.4) | 10/287 (3.5) | 3/288 (1.0) | 11/286 (3.8) |

| The Netherlands: East-Central | 5/239 (2.1) | 5/237 (2.1) | 1/239 (0.4) | 2/241 (0.8) | 13/239 (5.4) | 5/240 (2.1) | 17/239 (7.1) |

| Poland: Wielkopolska | 8/172 (4.7) | 16/173 (9.2) | 7/172 (4.1) | 8/173 (4.6) | 28/172 (16.3) | 1/173 (0.6) | 28/172 (16.3) |

| Portugal: Northern | 6/181 (3.3) | 5/181 (2.8) | 4/181 (2.2) | 2/181 (1.1) | 12/181 (6.6) | 6/181 (3.3) | 16/181 (8.8) |

| Portugal: Lisbon | 6/269 (2.2) | 5/269 (1.9) | 1/268 (0.4) | 5/269 (1.9) | 15/268 (5.6) | 4/268 (1.5) | 18/268 (6.7) |

| UK: Northern | 3/259 (1.2) | 0/256 (0.0) | 3/258 (1.2) | 4/277 (1.4) | 9/241 (3.7) | 9/229 (3.9) | 18/210 (8.6) |

| UK: East Midlands | 7/399 (1.8) | 10/396 (2.5) | 1/399 (0.3) | 2/399 (0.5) | 18/396 (4.5) | NA | NA |

| UK: Yorkshire and Humber | 11/489 (2.2) | 18/489 (3.7) | 5/489 (1.0) | 6/489 (1.2) | 39/489 (8.0) | NA | NA |

| Sweden: Stockholm | 1/173 (0.6) | 1/173 (0.6) | 0/168 (0.0) | 0/174 (0.0) | 2/167 (1.2) | 6/172 (3.5) | 7/167 (4.2) |

BPD, bronchopulmonary dysplasia; cPVL, cystic periventricular leukomalacia; GA, gestational age; IVH, intraventricular haemorrhage; NEC, necrotizing enterocolitis; ROP, retinopathy of prematurity.

The overall morbidity rate was higher when calculated for neonatal admissions (online supplementary table S1). Among deaths, 28% had a diagnosis of at least one morbidity, principally IVH grade III/V (22.1%) and NEC (6.5%). Proportions were lower for other morbidities with later age at diagnosis (online supplementary table S2).

fetalneonatal-2017-313697supp001.pdf (844.7KB, pdf)

Adjustment for maternal and neonatal characteristics

While several maternal and neonatal characteristics were associated with severe neonatal morbidity in univariable analyses, only GA, SGA, pre-eclampsia/eclampsia and congenital anomalies remained significant in multivariable analyses, as shown in table 3. This was the model used to compute the adjusted morbidity rates. Regional variation remained significant after adjustment (P<0.001). The coefficient of variation of regional rates decreased from 35.2% to 31.7% after adjustment (59.9% to 51.8% for infants 28–31 weeks and 28.5% to 27.4% for infants <28 weeks).

Table 3.

Associations between infant and pregnancy characteristics and severe morbidity: infants discharged from neonatal hospitalisation (n=6422)

| Characteristics | n | % | P | Adjusted RR (95% CI) |

| Infant characteristics | ||||

| Gestational age | ||||

| 23 | 19 | 61.3 | <0.001 | 45.55 (32.02 to 64.80) |

| 24 | 103 | 51.8 | 22.26 (14.51 to 34.15) | |

| 25 | 99 | 34.5 | 19.33 (13.91 to 26.86) | |

| 26 | 104 | 23.4 | 13.65 (9.75 to 19.11) | |

| 27 | 90 | 15.3 | 8.70 (6.19 to 12.24) | |

| 28 | 77 | 10.0 | 5.55 (3.91 to 7.89) | |

| 29 | 58 | 6.4 | 3.82 (2.66 to 5.49) | |

| 30 | 69 | 5.3 | 2.30 (1.56 to3.40) | |

| 31 | 44 | 2.6 | Ref | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 296 | 10.3 | 0.365 | Ref |

| Female | 367 | 11.0 | 1.10 (0.96 to 1.27) | |

| Type of pregnancy | ||||

| Singleton | 483 | 11.3 | 0.012 | Ref |

| Multiple | 180 | 9.2 | 0.94 (0.79 to 1.12) | |

| SGA* | ||||

| <10th | 183 | 9.1 | 0.008 | 0.82 (0.68 to 0.98) |

| ≥10th | 480 | 11.4 | Ref | |

| Maternal and pregnancy characteristics | ||||

| Maternal age | ||||

| <35 years | 497 | 10.9 | 0.200 | Ref |

| 35 years | 161 | 9.8 | 1.01 (0.86 to 1.18) | |

| Parity | ||||

| Nulliparous | 381 | 10.8 | 0.459 | Ref |

| Multiparous | 274 | 10.3 | 0.94 (0.81 to1.08) | |

| PPROM | 164 | 10.8 | 0.815 | 0.92 (0.78 to1.08) |

| Pre-eclampsia/ eclampsia/HELLP |

70 | 7.2 | <0.001 | 0.76 (0.59 to 0.98) |

| Congenital anomaly† | 67 | 14.5 | 0.005 | 1.34 (1.07 to 1.67) |

*Small for gestational age, using intrauterine references.

†Congenital anomalies reportable to Eurocat, but not severe. Cases with severe anomalies were excluded.

HELLP, hemolysis elevated liver enzymes low platelet count; PPROM, preterm premature rupture of membrane; RR, relative risk.

Association between regional rates of morbidity and mortality

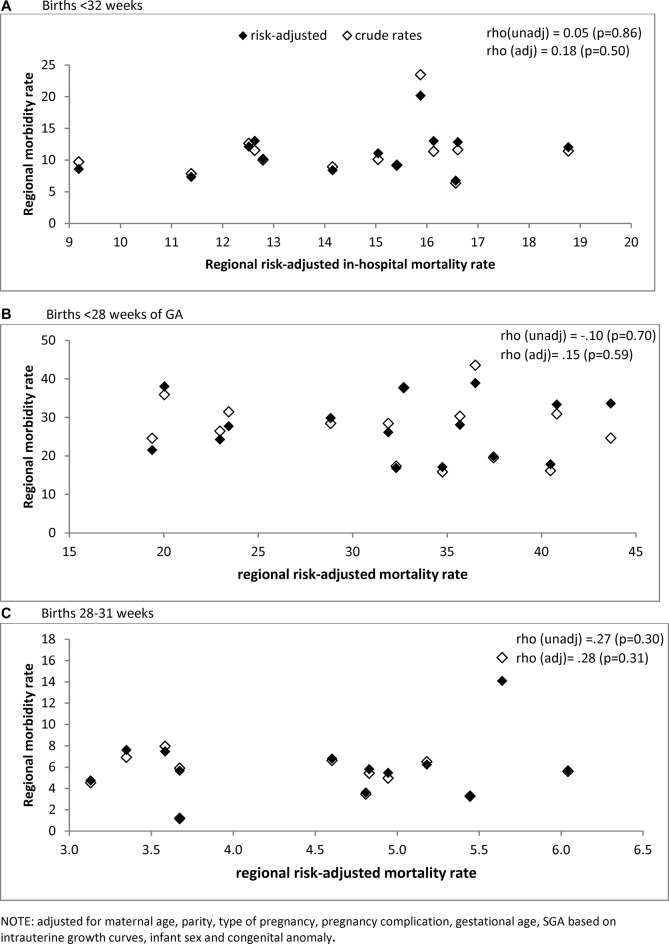

Risk-adjusted regional mortality rates ranged from 8.4% to 18.8% (unadjusted 7.3% to 21.1%) for the overall sample, 19.4% to 45.4% (unadjusted 17.0% to 43.8%) for infants <28 weeks and 1.4% to 6.0% (unadjusted 1.5% to 7.5%) for those 28–31 weeks (online supplementary table S3). Figure 1 illustrates the absence of an association between in-hospital mortality and morbidity without BPD among survivors, as shown by the Spearman rho included with the figure. Spearman rank correlations for each individual severe morbidity did not reveal negative associations, but there was a positive association with severe IVH (table 4). Scatter plots for each morbidity are included in supplementary material (online supplementary figure S1–S3)

Figure 1.

Association between adjusted severe neonatal morbidity composite, excluding severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia among survivors, and adjusted mortality rates in 16 European regions.

Table 4.

Spearman’s correlations between adjusted very preterm mortality and rates of individual morbidities, adjusted for GA, in 16 European regions, all births <32 weeks of GA and by GA subgroups

| <28 weeks' GA | 28–31 weeks' GA | Total <32 weeks' GA | ||||

| rho | P value | rho | P value | rho | P value | |

| IVH grade III/IV | 0.38 | 0.15 | 0.43 | 0.10 | 0.69 | <0.01 |

| cPVL | 0.02 | 0.93 | 0.30 | 0.26 | 0.22 | 0.42 |

| ROP stage 3+ | 0.08 | 0.75 | −0.01 | 0.98 | 0.14 | 0.61 |

| Severe NEC | −0.45 | 0.08 | 0.26 | 0.33 | −0.27 | 0.31 |

| Severe BPD | 0.11 | 0.71 | −0.47 | 0.09 | −0.11 | 0.70 |

BPD, bronchopulmonary dysplasia; cPVL, cystic periventricular leukomalacia; GA, gestational age; IVH, intraventricular haemorrhage; NEC, necrotizing enterocolitis; ROP, retinopathy of prematurity.

Discussion

Our study reveals wide variability in severe neonatal morbidity rates for very preterm infants across European regions: from 6% to 24% for overall morbidity without severe BPD. We did not observe a trade-off between rates of mortality and severe neonatal morbidity among surviving infants. In fact, for individual morbidities, we observed higher rates of severe brain lesions in higher mortality regions. Adjustment for maternal and neonatal characteristics reduced the variation between regions, but regional differences remained significant.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of our study are its population-based design and the use of a common and pretested protocol for medical record abstraction. The morbidities included in this study have well-established definitions. For BPD, we used the fraction of inspired oxygen at 36 weeks or respiratory support to define severe cases.23 Two regions did not collect information on FiO2 and thus we could not include severe BPD in our primary outcome variable. However, results associating morbidity with mortality were similar without and with severe BPD, although rates of severe neonatal morbidity increased from 10.6% to 13.8% with the latter. Our regional samples were not large enough to provide a high degree of precision for the prevalence of individual morbidities; variability due to random chance should be considered when comparing the results between regions. Finally, we did not have data on maternal socioeconomic status. However, while socioeconomic factors are major predictors of preterm birth risk and the health and development of very preterm children26 27 they have not been associated with inhospital mortality or morbidity.28 29

Comparison with other studies

Comparison of morbidity rates across studies is complicated because of the use of different definitions, GA cut-offs and population inclusion criteria. The US Neonatal Research Network centres reported rates of IVH grade III/IV of 15%, cPVL 4%, NEC (Bell stage 2–3) 10% and ROP, stage 3 or more, 12% among infants born at less than 28 weeks in 2008–2012 and surviving more than 12 hours after birth.13 A California population-based study of survivors born at 22–28 weeks using hospital data reported rates of 7.5% for IVH grade III/IV, 2.3% for PVL, 6.7 for NEC and 9.9% for ROP requiring surgery.30 Among survivors born at 28–31 weeks in the EPIPAGE 2 cohort in France in 2011,14 the rate of IVH grade III or more was 3.1%; cPVL 1.6%; ROP stage 3 or more 0.1%. Among survivors born at 28–31 weeks, severe BPD was 3.1% and NEC 3.2%. These results are within ranges in our study; some differences are due to use of neonatal intensive care unit admissions versus survivors, which leads to increased rates. Our results are also in line with recent findings from studies over time concluding that there is no obvious trade-off between mortality and severe morbidity rates among survivors.6 13

Interpretation

Differences in regional morbidity rates were attenuated, but persisted, after risk adjustment. Fewer maternal and neonatal characteristics were associated with morbidity compared with previous analyses of mortality.9 As risk factors differ for individual morbidities, adjustment for patient case mix may be more complex when morbidity is analysed as a composite. For instance, SGA is not a risk factor for IVH or PVL, but strongly affects BPD31; male sex is strongly related to IVH, but may be less important for other morbidities.32

In previous studies, regional differences have been attributed to variations in the use of interventions, such as tocolytics, administration of antenatal corticosteroids, delivery in tertiary centres and respiratory care.4 In this cohort, admission hypothermia varied widely between different regions and was associated with an almost twofold risk of neonatal mortality.33 However, there was no association with morbidity.33 Other evidence-based interventions in this cohort also showed a larger impact on mortality than morbidity.21 At the lowest GAs (22–24 weeks), initiation of active care may also differ between regions and influence the risks of mortality and neonatal morbidity.34 35

Implications for practice and policy

The variation in severe neonatal morbidity rates across regions suggests that reductions are possible with current medical knowledge. Very preterm birth leads to high costs for families, health services and societies due to life-long neurodevelopmental and other impairments.36 It is also associated with worse long-term health-related quality of life.37 Given the strong association between severe neonatal morbidity and adverse longer-term outcomes38 effective preventive actions represent a cost-effective use of finite healthcare resources. This focus is particularly important as the active management of extremely preterm infants becomes more widespread.35 Furthermore, we show the importance of having comparable international indicators of severe neonatal morbidity for surveillance, benchmarking and the large-scale research studies needed to improve our understanding of the determinants of severe neonatal morbidity.

Footnotes

AKEB and JZ contributed equally.

Contributors: AKEB and JZ had access to the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: AKEB, JZ, AP, RFM, AvH, HV, LK, BNM, AF, JM, MC, SP, PVR, HB, ESD; acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data: AKEB, JZ, AP, RFM, AvH, HV, BM, AF, JM, MC, SP, PVR, HB, ESD and all authors in the Epice Research Group; drafting of the manuscript: AKEB, JZ, AP, RFM, AvH, HV, BM, AF, JM, MC, SP, PVR, HB, ESD; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content and approval of final version of the manuscript: All authors (including investigators listed in Epice Research Group); statistical analysis: AKEB, JZ, AP. Final approval: all authors.

Funding: The research leading to these results received funding from the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement n°259882. Additional funding is acknowledge from the following regions: France (French Institute of Public Health Research/Institute of Public Health and its partners the French Health Ministry, the National Institute of Health and Medical Research, the National Institute of Cancer, and the National Solidarity Fund for Autonomy; grant ANR-11-EQPX-0038 from the National Research Agency through the French Equipex Program of Investments in the Future; and the Prem Up Foundation); Poland (2012- 2015 allocation of funds for international projects from the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education); Sweden (Stockholm County Council (ALF-project and Clinical Research Appointment) and by the Department of Neonatal Medicine, Karolinska University Hospital), UK (funding for The Neonatal Survey from Neonatal Networks for East Midlands and Yorkshire and Humber regions).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: French Advisory Committee on Use of Health Data in Medical Research and the French National Commission for Data Protection and Liberties. Also, ethics authorisation was obtained for each study in the participating regions.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Access to data in the EPICE cohort for researchers who are not members of the consortium is not currently possible, but EPICE is part of a H2020 project (RECAP, https://recap-preterm.eu/) to develop a Platform for data sharing. Please contact the corresponding author for more information.

Collaborators: BELGIUM: Flanders (E Martens, G Martens, P Van Reempts); DENMARK: Eastern Region (K Boerch, A Hasselager, L Huusom, O Pryds, T Weber); ESTONIA (L Toome, H Varendi); FRANCE: Burgundy, Ile-de France and Northern Region (PY Ancel, B Blondel, A Burguet, PH Jarreau, P Truffert); GERMANY: Hesse (RF Maier, B Misselwitz, S Schmidt), Saarland (L Gortner); ITALY: Emilia Romagna (D Baronciani, G Gargano), Lazio (R Agostino, D DiLallo, F Franco), Marche (V Carnielli), M Cuttini; NETHERLANDS: Eastern & Central (C Koopman-Esseboom, A Van Heijst, J Nijman); POLAND: Wielkopolska (J Gadzinowski, J Mazela); PORTUGAL: Lisbon and Tagus Valley (LM Graça, MC Machado), Northern region (Carina Rodrigues, T Rodrigues), H Barros; SWEDEN: Stockholm (AK Bonamy, M Norman, E Wilson); UK: East Midlands and Yorkshire and Humber (E Boyle, ES Draper, BN Manktelow), Northern Region (AC Fenton, DWA Milligan); INSERM, Paris (J Zeitlin, M Bonet, A Piedvache).

Contributor Information

on behalf of Epice Research Group:

East Midlands And yorkshire and humber (e boyle, Es Draper, Bn Manktelow), Northern Region (ac fenton, Dwa Milligan), INSERM, Paris (j Zeitlin, M Bonet, and A Piedvache)

Collaborators: on behalf of Epice Research Group

References

- 1. Blencowe H, Cousens S, Oestergaard MZ, et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of preterm birth rates in the year 2010 with time trends since 1990 for selected countries: a systematic analysis and implications. Lancet 2012;379:2162–72. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60820-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rysavy MA, Li L, Bell EF, et al. Between-hospital variation in treatment and outcomes in extremely preterm infants. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1801–11. 10.1056/NEJMoa1410689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Seaton SE, King S, Manktelow BN, et al. Babies born at the threshold of viability: changes in survival and workload over 20 years. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2013;98:F15–20. 10.1136/fetalneonatal-2011-301572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fellman V, Hellström-Westas L, Norman M, et al. One-year survival of extremely preterm infants after active perinatal care in Sweden. JAMA 2009;301:2225-33 10.1001/jama.2009.771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Costeloe KL, Hennessy EM, Haider S, et al. Short term outcomes after extreme preterm birth in England: comparison of two birth cohorts in 1995 and 2006 (the EPICure studies). BMJ 2012;345:e7976 10.1136/bmj.e7976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Serenius F, Sjörs G, Blennow M, et al. EXPRESS study shows significant regional differences in 1-year outcome of extremely preterm infants in Sweden. Acta Paediatr 2014;103:27–37. 10.1111/apa.12421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Field DJ, Dorling JS, Manktelow BN, et al. Survival of extremely premature babies in a geographically defined population: prospective cohort study of 1994-9 compared with 2000-5. BMJ 2008;336:1221–3. 10.1136/bmj.39555.670718.BE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Smith LK, Draper ES, Manktelow BN, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in survival and provision of neonatal care: population based study of very preterm infants. BMJ 2009;339:b4702 10.1136/bmj.b4702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Draper ES, Manktelow BN, Cuttini M, et al. Variability in Very Preterm Stillbirth and In-Hospital Mortality Across Europe. Pediatrics 2017;139:e20161990 10.1542/peds.2016-1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lam HS, Wong SP, Liu FY, et al. Attitudes toward neonatal intensive care treatment of preterm infants with a high risk of developing long-term disabilities. Pediatrics 2009;123:1501–8. 10.1542/peds.2008-2061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gallagher K, Aladangady N, Marlow N. The attitudes of neonatologists towards extremely preterm infants: a Q methodological study. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2016;101:31–6. 10.1136/archdischild-2014-308071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zeitlin J, Ancel PY. Interpreting data on the health outcomes of extremely preterm babies. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2011;96:F314–16. 10.1136/adc.2010.202168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Bell EF, et al. Trends in Care Practices, Morbidity, and Mortality of Extremely Preterm Neonates, 1993-2012. JAMA 2015;314:1039–51. 10.1001/jama.2015.10244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ancel PY, Goffinet F, Kuhn P, et al. Survival and morbidity of preterm children born at 22 through 34 weeks' gestation in France in 2011: results of the EPIPAGE-2 cohort study. JAMA Pediatr 2015;169:230-8 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.3351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Grisaru-Granovsky S, Reichman B, Lerner-Geva L, et al. Population-based trends in mortality and neonatal morbidities among singleton, very preterm, very low birth weight infants over 16 years. Early Hum Dev 2014;90:821–7. 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2014.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Moore T, Hennessy EM, Myles J, et al. Neurological and developmental outcome in extremely preterm children born in England in 1995 and 2006: the EPICure studies. BMJ 2012;345:e7961 10.1136/bmj.e7961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. de Waal CG, Weisglas-Kuperus N, van Goudoever JB, et al. Mortality, neonatal morbidity and two year follow-up of extremely preterm infants born in The Netherlands in 2007. PLoS One 2012;7:e41302 10.1371/journal.pone.0041302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Younge N, Goldstein RF, Bann CM, et al. Survival and neurodevelopmental outcomes among periviable infants. N Engl J Med 2017;376:617–28. 10.1056/NEJMoa1605566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Draper ES, Zeitlin J, Fenton AC, et al. Investigating the variations in survival rates for very preterm infants in 10 European regions: the MOSAIC birth cohort. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2009;94:F158–63. 10.1136/adc.2008.141531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shah PS, Lui K, Sjörs G, et al. Neonatal outcomes of very low birth weight and very preterm neonates: An international comparison. J Pediatr 2016;177:144–52. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.04.083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zeitlin J, Manktelow BN, Piedvache A, et al. Use of evidence based practices to improve survival without severe morbidity for very preterm infants: results from the EPICE population based cohort. BMJ 2016;354:i2976 10.1136/bmj.i2976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Papiernik E, Zeitlin J, Delmas D, et al. Termination of pregnancy among very preterm births and its impact on very preterm mortality: results from ten European population-based cohorts in the MOSAIC study. BJOG 2008;115:361–8. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01611.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jobe AH, Bancalari E. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;163:1723–9. 10.1164/ajrccm.163.7.2011060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zeitlin J, Bonamy AE, Piedvache A, et al. Variation in term birthweight across European countries affects the prevalence of small for gestational age among very preterm infants. Acta Paediatr 2017;106:1447–55. 10.1111/apa.13899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. EUROCAT. European surveillance of congenital anomalies. www.eurocat-network.eu (accessed Jun 2017).

- 26. Smith LK, Draper ES, Manktelow BN, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in very preterm birth rates. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2007;92:F11–F14. 10.1136/adc.2005.090308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wong HS, Edwards P. Nature or nurture: a systematic review of the effect of socio-economic status on the developmental and cognitive outcomes of children born preterm. Matern Child Health J 2013;700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bonet M, Smith LK, Pilkington H, et al. Neighbourhood deprivation and very preterm birth in an English and French cohort. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013;13:97 10.1186/1471-2393-13-97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Germany L, Saurel-Cubizolles MJ, Ehlinger V, et al. Social context of preterm delivery in France in 2011 and impact on short-term health outcomes: the EPIPAGE 2 cohort study. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2015;29:184–95. 10.1111/ppe.12189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Anderson JG, Baer RJ, Partridge JC, et al. Survival and major morbidity of extremely preterm infants: a population-based study. Pediatrics 2016;138:e20154434 10.1542/peds.2015-4434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zeitlin J, El Ayoubi M, Jarreau PH, et al. Impact of fetal growth restriction on mortality and morbidity in a very preterm birth cohort. J Pediatr 2010;9:e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mohamed MA, Aly H. Male gender is associated with intraventricular hemorrhage. Pediatrics 2010;125:e333–9. 10.1542/peds.2008-3369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wilson E, Maier RF, Norman M, et al. Admission Hypothermia in Very Preterm Infants and Neonatal Mortality and Morbidity. J Pediatr 2016;175:61–7. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.04.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Smith LK, Blondel B, Van Reempts P, et al. Variability in the management and outcomes of extremely preterm births across five European countries: a population-based cohort study. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2017;102:F400–F408. 10.1136/archdischild-2016-312100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bonet M, Cuttini M, Piedvache A, et al. Changes in management policies for extremely preterm births and neonatal outcomes from 2003 to 2012: two population-based studies in ten European regions. BJOG 2017;124:1595–604. 10.1111/1471-0528.14639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Petrou S, Eddama O, Mangham L. A structured review of the recent literature on the economic consequences of preterm birth. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2011;96:F225–32. 10.1136/adc.2009.161117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Petrou S, Abangma G, Johnson S, et al. Costs and health utilities associated with extremely preterm birth: evidence from the EPICure study. Value Health 2009;12:1124–34. 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2009.00580.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schmidt B, Asztalos EV, Roberts RS, et al. Impact of bronchopulmonary dysplasia, brain injury, and severe retinopathy on the outcome of extremely low-birth-weight infants at 18 months: results from the trial of indomethacin prophylaxis in preterms. JAMA 2003;289:1124–9. 10.1001/jama.289.9.1124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

fetalneonatal-2017-313697supp001.pdf (844.7KB, pdf)