Abstract

Rapamycin, an inhibitor of target-of-rapamycin, extends lifespan in mice, possibly by delaying aging. We recently showed that rapamycin halts the progression of Alzheimer’s (AD)-like deficits, reduces amyloid-beta (Aβ) and induces autophagy in the human amyloid precursor protein (PDAPP) mouse model. To delineate the mechanisms by which chronic rapamycin delays AD we determined proteomic signatures in brains of control- and rapamycin-treated PDAPP mice. Proteins with reported chaperone-like activity were overrepresented among proteins up-regulated in rapa-mycin-fed PDAPP mice and the master regulator of the heat-shock response, heat-shock factor 1, was activated. This was accompanied by the up-regulation of classical chaperones/heat shock proteins (HSPs) in brains of rapamycin-fed PDAPP mice. The abundance of most HSP mRNAs except for alpha B-crystallin, however, was unchanged, and the cap-dependent translation inhibitor 4E-BP was active, suggesting that increased expression of HSPs and proteins with chaperone activity may result from preferential translation of pre-existing mRNAs as a consequence of inhibition of cap-dependent translation. The effects of rapamycin on the reduction of Aβ, up-regulation of chaperones, and amelioration of AD-like cognitive deficits were recapitulated by transgenic over-expression of heat-shock factor 1 in PDAPP mice. These results suggest that, in addition to inducing autophagy, rapamycin preserves proteostasis by increasing chaperones. We propose that the failure of proteostasis associated with aging may be a key event enabling AD, and that chronic inhibition of target-of-rapamycin may delay AD by maintaining proteostasis in brain.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, chaperones, heat shock factor 1, proteostasis, rapamycin, TOR

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common form of age-associated dementia (Selkoe 2002). Deficits in AD are believed to result in large part from the accumulation of amyloid-beta (Aβ), a toxic peptide released after proteolysis of the amyloid precursor protein (APP). The largest risk factor for AD is aging itself. Aging and age-associated diseases such as AD have in common the expression of misfolded and aggregated or damaged proteins (Hartl et al. 2011). Protein homeostasis or proteostasis is defined as the tendency of a cell or system to maintain proteins in their functional state by facilitating their proper folding, or their degradation. Heat shock proteins (HSPs) and chaperones have a major role in promoting proteostasis by assisting protein folding, or by promoting their dissociation and degradation when improperly folded or aggregated. The expression of major HSPs in mammals is regulated mainly by heat shock factor 1 (HSF1), (Morimoto 1998; Morley and Morimoto 2004). HSF1 expression is required for lifespan extension and protection from proteotoxicity by caloric restriction in C. elegans (Steinkraus et al. 2008). Over-expression of HSF1 alone is sufficient to increase longevity (Hsu et al. 2003), and it ameliorates neurodegeneration in C. elegans models of polyglutamine (polyQ) diseases (Hsu et al. 2003; Morley and Morimoto 2004) and Alzheimer’s disease (Cohen et al. 2010). Conversely, loss of HSF1 function accelerates neurodegeneration through the reduced expression of major HSPs (Fujimoto et al. 2005; Steele et al. 2008). Aging is associated with a decline in HSP levels and in the responsiveness to stress, both at the cellular and organismal levels (Tonkiss and Calderwood 2005). Transgenic mice over-expressing HSF1 (HSF1+/0) were recently generated that show a significantly enhanced heat shock response and protection against physiological and pathological stresses (Pierce et al. 2010). The primary form of regulation of heat shock genes is at the level of transcription. Abundance of HSPs, however, is also post-transcriptionally regulated (Banerji et al. 1984; Theodorakis et al. 1988; Morimoto 2008). HSP mRNAs are preferentially translated when cap-dependent translation is inhibited (Beretta et al. 1996), resulting in their continued synthesis when global translation is compromised (Panniers 1994; Cuesta et al. 2000). eIF4E is a translation initiation factor that is required to direct ribosomes to the cap (Kapp and Lorsch 2004) structure of eukaryotic mRNAs. Hypophosph-orylated eIF4E binding protein 1 (4E-BP1) interacts strongly with eIF4E and blocks eIF4E function. Under normal growth conditions (Gingras et al. 1999), 4E-BP is repressed by target-of-rapamycin (TOR; Ma and Blenis 2009), by phosphorylation on Thr-37 and Thr-46(Gingras et al. 1999, 2001). Rapamycin inhibits 4E-BP1 phosphorylation by mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), enabling the interaction between eIF4E and 4E-BP1, and consequently inhibiting cap-dependent translation (Beretta et al. 1996; Gingras et al. 2001; Ma and Blenis 2009).

We (Spilman et al. 2010) and others (Caccamo et al. 2010) had previously demonstrated that inhibition of the mTOR pathway by long-term rapamycin treatment blocks AD-like cognitive impairment and Aβ accumulation in the human amyloid precursor protein (PDAPP) mouse model of AD, and enhances aspects of proteostasis through the induction of autophagy. The experiments of this study were conducted to further explore the mechanisms by which chronic rapamycin lowers Aβ levels and improves cognitive outcomes in PDAPP mice.

Methods

Mice

Human amyloid precursor protein mice (Hsia et al. 1999; Galvan et al. 2006) were maintained by heterozygous crosses with C57BL/6J mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Even though the human APP transgene is driven by a neuronal promoter, heterozygous crosses were set up such that the transgenic animal in was the dam or the sire in approximately 50% of the breeding pairs to avoid biases related to potential effects of transgene expression during gametogenesis, and to rule out imprinting effects. All experimental PDAPP transgenic mice were heterozygous with respect to the transgene. Non-transgenic littermates were used as controls. Unless stated otherwise, experimental groups were as follows: control-fed non-Tg, n = 10; rapamycin-fed non-Tg, n = 10; control-fed Tg, n = 12; rapamycin-fed Tg, n = 12. Rapamycin was administered for 16 weeks starting at 4 months of age. All animals were males and 8-month old at the time of testing. HSF1+/0 were derived and maintained on a C57BL/6 background.

Rapamycin treatment

Mice were fed chow containing either microencapsulated rapamycin at 2.24 mg/kg or a control diet as described by Harrison et al. (2009). More information is provided in the Supporting Information section.

Behavioral testing

The novel object recognition task was used to test recognition memory (Antunes and Biala 2012), associated with dorsal hippocampal function. Spatial learning and memory were determined using the Morris water maze (Zhang et al. 2010; Morris 1984; Galvan et al. 2006, 2008), Supporting Information section.

2D Gel Electrophoresis

Tissues were processed for 2D gel electrophoresis as described (Pierce et al. 2008) and Supporting Information section.

Immunoblots and real–time quantitative PCR

Mice were killed by isoflurane overdose followed by cervical dislocation. Hemibrains were flash frozen. One hemibrain was homogenized in liquid N2, while the other was used in immunohistochemical and RT-PCR determinations. Detailed information is provided in the Supporting Information section.

Immunohistochemistry

Ten-micrometer coronal cryosections from snap-frozen brains were post-fixed in ice-cold methanol, stained with specific antibodies and imaged as described in Supporting Information.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (Graph-Pad, JMP Software, San Diego, CA, USA) and StatView. In two-variable experiments, two-way anova followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc tests were used to evaluate the significance of differences between group means. When analyzing one-variable experiments with more than two groups (such as in the evaluation of changes in abundance in chaperone proteins using proteomic studies, Table 1 as indicated), significance of differences among means was evaluated using one-way anova followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. Evaluation of differences between two groups was evaluated using Student’s t-test. Values of p < 0.05 were considered significant.

Table 1.

Proteins differentially expressed in brain tissues of control- as compared with rapamycin-treated PDAPP transgenic mice. Significance of differences was assessed using Student’s t-test and one-way anova. p-values are indicated

| Protein Name | Proteins Changed by 2D Gel Electrophoresis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Access. no. |

Mass Values Searched |

Mass Values Matched |

% Cover-age |

Mowse Score |

Fold change, rapa-treated |

p-value t-test |

p-value 1W-anova |

|

| Neurofilament M protein | P08553 | 44 | 26 | 27 | 196 | > 2-fold Increase | < 0.05 | |

| Nuclear mitotic apparatus protein | Q80Y35 | 104 | 38 | 16 | 84 | > 2-fold Increase | 0.19 | |

| Kinesin like protein | P28741 | 98 | 25 | 28 | 72 | > 2-fold Increase | 0.24 | |

| Endoplasmin | P08113 | 47 | 25 | 28 | 179 | 1.98 | < 0.05 | |

| Dynamin 1 | P39053 | 52 | 24 | 24 | 129 | > 2-fold Increase | 0.09 | |

| NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreduct 75 kDa subunit, mitochondrial | Q91VD9 | 88 | 24 | 36 | 103 | > 2-fold Increase | 0.18 | |

| Neurofilament Light Polypeptide | P08551 | 49 | 29 | 43 | 277 | > 2-fold Increase | 0.08 | |

| 33 | 16 | 27 | 134 | 0.73 | < 0.05 | |||

| Dihydropyrimidinase-related protein 2 | O08553 | 69 | 15 | 33 | 76 | 1.49 | < 0.05 | |

| 48 | 17 | 41 | 123 | 1.22 | < 0.05 | |||

| Alpha Internexin | P46660 | 68 | 28 | 46 | 221 | > 2-fold Increase | 0.17 | |

| Glial Fibrilary Acidic Protein | P03995 | 96 | 17 | 39 | 73 | > 2-fold Decrease | 0.06 | |

| Guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(o) alpha | P18872 | 49 | 13 | 34 | 82 | 0.78 | < 0.05 | |

| 14-3-3 protein zeta/delta | P63101 | 47 | 12 | 47 | 97 | > 2-fold Increase | 0.16 | |

| 64 | 16 | 51 | 117 | 1.82 | < 0.05 | |||

| Beta Synuclein | Q91ZZ3 | 17 | 6 | 45 | 76 | 1.40 | < 0.05 | |

| Alpha Synuclein | O55042 | 20 | 5 | 39 | 67 | 1.84 | < 0.05 | |

| Proteins Changed by Immunoblot | ||||||||

| CryAB | 1.38 | 0.02 | < 0.0001 | |||||

| HSP105 | 1.49 | 0.03 | < 0.001 | |||||

| HSP60 | 1.38 | 0.22 | < 0.001 | |||||

| HSP90 | 1.88 | 0.01 | < 0.001 | |||||

| HSP25 | 1.268 | 0.09 | < 0.001 | |||||

Ethics and guidelines statement

All studies reported were in compliance with all rules and regulations for the humane use of animals in research and were approved by the University of Texas Health Science Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. To minimize pain or discomfort, mice were killed by isoflurane overdose, which is significantly less stressful than other methods such as asfixiation by CO2 overdose. The Animal Research: Reporting in vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines as described by Kilkenny et al. 2010 have been followed in the preparation of this manuscript.

Results

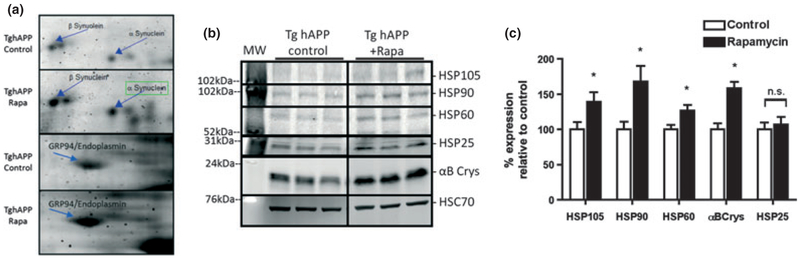

Chronic rapamycin treatment increases levels of chaperones and proteins with chaperone–like activity in PDAPP mouse brains

We previously demonstrated that chronic feeding with rapamycin-supplemented chow decreased Aβ, halted the progression of AD-like cognitive decline and increased brain autophagy in PDAPP transgenic mice. To further explore the mechanisms by which chronic rapamycin feeding blocks cognitive decline in PDAPP mice we determined proteomic signatures (Ideker and Krogan 2012) in brains of PDAPP mice that were fed control- or rapamycin-supplemented chow for 16 weeks starting at 4 months of age to identify changes in levels of proteins that correlated with decreased brain Aβ and improved cognitive function (Spilman et al. 2010). Six (43%) of the proteins that showed changes in rapamycin-treated brains were categorized primarily as structural proteins, 2 (14%) as synaptic proteins, 2 (14%) as signaling proteins, 1 (7%) as a protein involved in metabolism, 1 (7%) as a protein that functions as a professional chaperone, while 2 (14%) are involved in vesicle transport. We determined significance of differences in protein abundance using BioRad PdQuest software (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA), with either a 2-fold cutoff or a significance level of p < 0.05. Although a 2-fold change is generally considered of interest in proteomics studies, we included a second criterion that incorporated statistical testing of fold-differences, as proteins that change by less than 2-fold can still contribute a relevant physiological effect. Of 14 proteins that were significantly changed to any extent, or were changed over 2-fold, or both, in rapamycin-treated PDAPP brains, 4 (29%), while not classical chaperones, were reported to have chaperone-like activity, including endoplasmin/glucose-regulated protein 94 (GRP94) (Eletto et al. 2010), 14-3-3 zeta (Vincenz and Dixit 1996; Lynn et al. 2008), and alpha (Rekas et al. 2012) and beta (Lee et al. 2004) synucleins (Fig. 1a and Table 1). As chaperone-activity is important for proteostasis, we next determined whether levels of classical chaperones were also increased in rapamycin-treated PDAPP brains by immunoblot. HSP105, HSP90, HSP60, and alpha B-crystallin (CryAB), but not Hsp25, Hsp22, nor Hsp70 (Figure S1) were significantly up-regulated in brains of rapamycin-fed PDAPP animals as compared with control-fed mice (Fig. 1b and c). Covariation analyses of chaperone abundance changes in brains of rapamycin-fed as compared with control-fed PDAPP mice revealed that the slopes of the curves representing changes in levels of different HSPs were significantly different from zero (p = 0.01) but were not significantly different from each other (p = 0.35, multiple linear regression analysis). The calculated value of the pooled slope for the curves representing the increases in abundance of chaperones in rapamycin-treated PDAPP brains was 48.36 and the Y-intercept was 51.6353. Thus, levels of HSP105, HSP90, HSP60, and CryAB were synchronously increased in brains of PDAPP mice chronically fed with a rapamycin-supplemented diet.

Fig. 1.

Up-regulation of chaperones in brains of rapamycin-fed human amyloid precursor protein mice. (a) Regions of representative 2D gels showing up-regulated α and β-synuclein, GRP94, and 14-3-3 in rapamycin-fed human amyloid precursor protein mice, respectively. Arrows indicate spot identities determined by MALDI-TOF MS. n = 12 animals per experimental group. (b) Representative immunoblots of major Heat shock proteins (HSPs) from whole-brain extracts. (c) Densitometric quantitation of immunoblots normalized to HSC70. Immunoblots were performed four times. n = 5–8 animals/group. Data are averages ± SEM. * indicates p < 0.05.

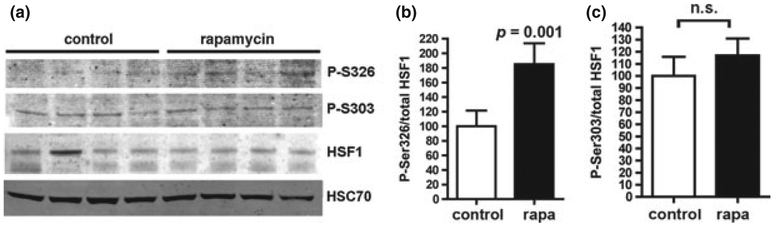

Activated HSF1 is increased in brains of rapamycin–fed PDAPP mice

Heat shock gene expression requires the activation of heat shock factor transcriptional activators including HSF1 (Morimoto 1998). HSF1 is regulated by interaction of its monomers with HSP90, and by constitutive repressive phosphorylation at Ser(S) 303 and S307 (Knauf et al. 1996; Chu et al. 1998). Competitive binding of misfolded proteins to HSP90 relieves its interaction with HSF1 and enables the activation of HSF1 by trimerization and acquisition of transcriptional competence after phosphorylation at Ser326 (Guettouche et al. 2005). To determine whether the increased HSP levels in brains of rapamycin-treated mice was associated with increased activation of HSF1, we examined the phosphorylation of HSF1 at S326 and S303 in brain tissues of control- and rapamycin-fed PDAPP mice. In agreement with the increase in HSP levels, we found that S326-phosphorylated HSF1 was increased in brains of rapamycin-fed PDAPP animals (Fig. 2a and b). The phospho-specific antibody that recognizes HSF1 phosphorylated at S326, however, recognized endogenous brain proteins only weakly as compared with recombinant HSF1 over-expressed in continuous cell line cultures. Thus, the intensity of the bands observed in immunoblots of brain tissue lysates exposed to the phospho-Ser326-HSF1-specific antibody was weak, both in Western blots of brain lysates as well as in western blots of material immunoprecipitated from brain lysates using an antibody specific for total HSF1, or the same P(Ser326)HSF1 antibody (Figure S4). No significant differences in phosphorylation of HSF1 at S303 were observed among experimental groups (Fig. 2a and c). The increase in phosphorylation of HSF1 at S326 with no changes in phosphorylation at S303 suggests that chronic rapamycin feeding increases HSF1 activity in brains of PDAPP mice.

Fig. 2.

Levels of Ser326-phosphorylated (activated) heat-shock factor 1 (HSF1) are increased in brains of rapamycin-fed human amyloid precursor protein mice. (a) Representative immunoblots of whole-brain lysates from control- and rapamycin-fed human amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice. HSC70 immunoreactive bands serve as loading control. (b) Quantitative analyses of phosphorylated HSF1 (Ser326), calculated as the ratio of P(S326)HSF1 to total HSF1 for each sample. (c) Quantitative analyses of phosphorylated HSF1 (Ser303), calculated as the ratio of P(Ser303)HSF1 to total HSF1 for each sample. Student’s t-test was used to determine significance of differences between means. p as indicated. Immunoblots for Ser326 and Ser303-phosphorylated HSF1 and for HSF1 were performed 3 times; immunoblots for HSC70 were performed four times. n = 4–8 animals/group. Data are means ± SEM.

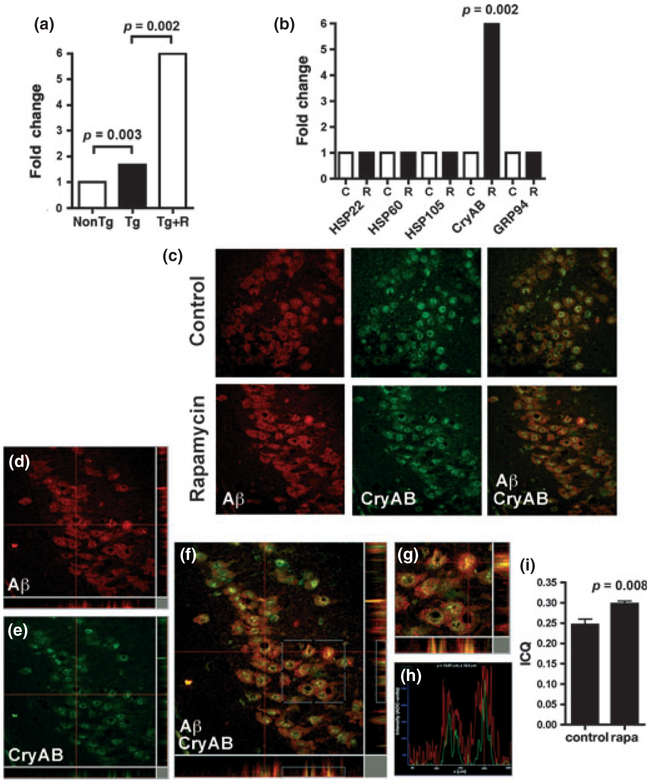

Transcription of CryAB, but not of other chaperones, is increased in brains of rapamycin–fed PDAPP mice

Proteostatic stress activates the HSF1-mediated transcriptional response and also largely inhibits protein synthesis (Voisine et al. 2010). Translation of pre-existing heat shock mRNAs is favored in these conditions, however, resulting in their continuing synthesis when global translation is compromised (Panniers 1994). To determine whether chronic rapamycin feeding changes HSP mRNA levels in brain, we performed real-time quantitative PCR using primers specific for HSP105, HSP90, HSP60, GRP94, CryAB, and HSP22 on brain tissues from control- and rapamycin-fed PDAPP mice. In spite of the observed increase in S326-phosphorylated HSF1 in rapamycin-treated PDAPP brains (Fig. 2), the abundance of most HSP mRNAs was unchanged (Fig. 3a), suggesting that their up-regulation at the protein level is a result of the preferential translation of pre-existing mRNAs (Voisine et al. 2010; Morimoto 1998). CryAB mRNA levels, however, were significantly increased in brains of PDAPP mice chronically fed with rapamycin-supplemented chow as compared with control-fed mice (Fig. 3a). Moreover, CryAB mRNA levels were significantly increased in brain tissues of PDAPP transgenic mice with respect to those of non-transgenic littermates (Fig. 3b), suggesting that the CryAB gene is up-regulated in brains of PDAPP mice with respect to non-transgenic littermates, and that chronic rapamycin treatment further stimulates CryAB transcription in transgenic PDAPP brains. The CryAB promoter has been extensively characterized in the lens (Somasundaram and Bhat 2004; Duncan and Zhao 2007). However, relatively less is known about the regulation of CryAB transcription in brain. The CryAB gene 5′UTR contains functional HSF1, HSF2, and HSF4 binding sites (Somasundaram and Bhat 2004; Schug 2008). Although we cannot rule out an effect of HSF2 and/or HSF4 in the activation of CryAB transcription, HSF2 is not stress-inducible (McMillan et al. 2002) and HSF4 is only expressed in olfactory epithelium and in the lens in the adult (Nakai 2009). Thus, the increase in CryAB mRNA observed in PDAPP brains is likely a result of HSF1 transcriptional transactivation in conditions of proteotoxic stress induced by Aβ accumulation.

Fig. 3.

Alpha B-crystallin (CryAB) is transcriptionally up-regulated and is found in the proximity of Aβ-specific immunoreactivity in brains of rapamycin-fed human amyloid precursor protein (PDAPP) mice. (a) CryAB mRNA levels are higher (1.6-fold) in brains of control-fed transgenic PDAPP mice, and (b) further augmented (6-fold) in brains of PDAPP mice chronically fed with rapamycin-supplemented chow. Data are fold changes in mRNA normalized to GAPDH. n = 6 animals/group. (c) Representative images of confocal images obtained from hippocampal CA3 of control-fed (c) and rapamycin-fed (d) PDAPP mouse brains. (d–g) Orthogonal threedimensional projections of a representative z-stack of confocal images obtained from hippocampal CA3 of rapamycin-fed PDAPP mice. (d and e) Orthogonal three-dimensional projections of the green (d) and red (e) channel signals, corresponding to Aβ- and CryAB-specific immunoreactivity, respectively. (f) Overlay of green (Aβ) and green (CryAB) channels. The region of interest shown in (g) and analyzed in (h) is denoted as a white square. (g) Magnified view of the inset in (f). (h) Correlation plots for the intensity values of green (CryAB immunoreactivity) and red (Aβ-specific immunoreactivity) signals in the x- and y-orthogonal planes shown in (g). The antibody used (6E10) detects both free Aβ and Aβ sequences embedded in the amyloid precursor protein precursor. (i) Intensity correlation quotients (ICQ) for CryAB and Aβ-specific immunoreactive signals are significantly increased in hippocampi of rapamycin-fed PDAPP mice (p as indicated). Student’s t-test was used to determine significance of differences between means. n = 4 animals/group. Data are means ± SEM.

Up-regulation of CryAB mRNA in PDAPP mouse brains, however, was not accompanied by a proportional increase in protein levels (Fig. 4c), suggesting that the increase in CryAB transcription by HSF1 may represent a blunted activation of the chaperone response as a consequence of Aβ accumulation that does not result in net increases in CryAB protein abundance in PDAPP brains.

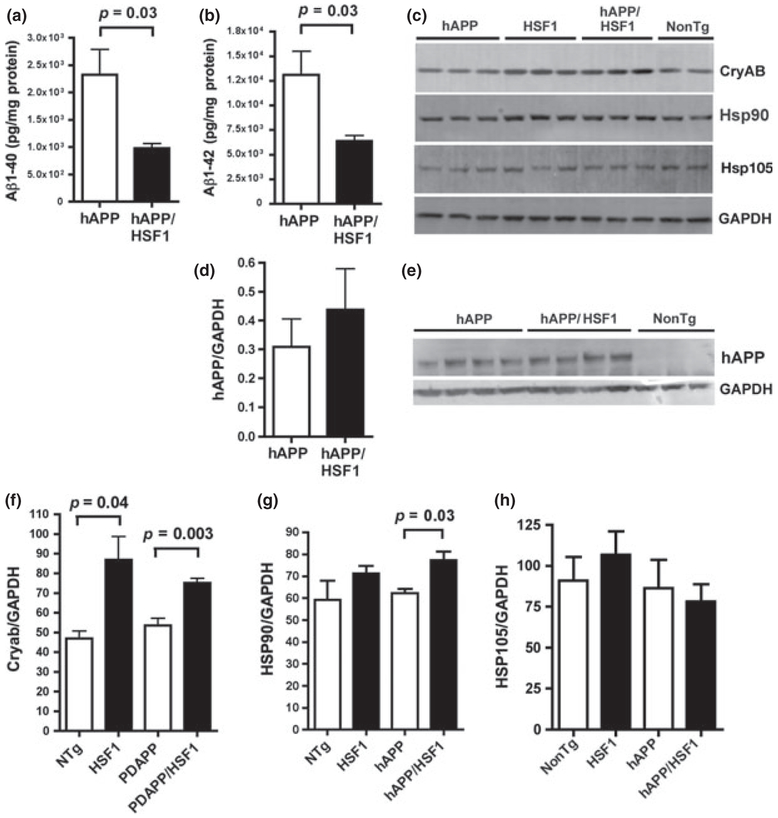

Fig. 4.

Transgenic over-expression of heat-shock factor 1 (HSF1) reduces Aβ levels and increases levels of CryAB and Hsp90 in brains of human amyloid precursor protein (PDAPP) mice. (a) Levels of Aβ1–40 and (b) Levels of Aβ1–42 are reduced in brains of double-transgenic PDAPP/HSF1+/0 mice. n = 4 animals/group. (c) Representative immunoblots of whole-brain lysates from non-transgenic (NonTg) or HSF1+/0 (HSF1), PDAPP single-transgenic and PDAPP/HSF1+/0 (PDAPP/HSF1) double-transgenic mice. Antibodies used in immunoblots are indicated. (d) Quantitative analyses and (e) representative immunoblots show that levels of the APP precursor are unchanged by HSF1 overexpression. (f–h) Quantitative densitometric analyses of immunoreactive bands in (c). p as indicated, Tukey’s post hoc test applied to a significant effect of genotype for the HSF1 transgene (p = 0.006, one-way anova). (g) A trend that did not reach significance (p = 0.059) was observed for the effect of genotype for the HSF1 transgene in one-way anova. p as indicated, Student’s t-test for the comparison between PDAPP and PDAPP/HSF1 groups. (h) No significant differences in HSP105 abundance were observed between experimental groups. Immunoblots for CryAB, Hsp90, amyloid precursor protein, andGAPDH were performed three times; immunoblots for Hsp105 were performed four times. n = 4–8 animals/group. Data are means ± SEM.

CryAB is found in close proximity to Aβ–immunoreactive signals in brains of rapamycin–fed PDAPP mice

In addition to the lens, CryAB is also expressed extensively in other tissues, including the brain (Ecroyd and Carver 2009). CryAB and its C. elegans homolog HSP16 have previously been implicated in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease (Wu et al. 2010; Shinohara et al. 1993; Renkawek et al. 1994). HSP16 is induced by over-expression of Aβ, interacts with Aβ in Aβ-transgenic C. elegans (Fonte et al. 2002, 2008), and can partially suppress Aβ toxicity (Fonte et al. 2008). To determine whether CryAB was present in proximity to Aβ-containing molecules in PDAPP brains, we performed dual immunolabeling and confocal microscopy analyses of sections of control- and rapamycin-fed PDAPP mice using antibodies specific for CryAB and for Aβ (Fig. 3c and d). The antibody used to detect Aβ (6E10) recognizes both the free peptide and its sequence in full-length APP. Consistent with prior reports (Fonte et al. 2002, 2008), thresholded Mander’s split colocalization coefficients (Manders et al. 1993; Costes et al. 2004) for CryAB and for Aβ-immunoreactive signals were 0.24 and 0.48, respectively, indicating that roughly 1:4 of the CryAB signal and 1 : 2 of the Aβ-containing APP signal were colocalized with each other, respectively (Manders et al. 1993; Costes et al. 2004). If two proteins are parts of the same complex, then their immunostaining intensities are likely to vary in synchrony (Manders et al. 1993; Li et al. 2004). The intensity correlation quotients [ICQ, an index of whether the staining intensities are associated in a random, dependent, or segregated manner, (Li et al. 2004)] for CryAB and Aβ-immunoreactive signals showed a dependent association that was significantly increased in rapamycin-treated brains (Fig. 3e and f). These results suggest that CryAB and Aβ or CryAB and Aβ-containing full-length APP molecules, are present in close proximity in hippocampi of PDAPP transgenic mice, and that chronic rapamycin feeding enhances their association. Signals for CryAB- and Aβ-specific immunoreactivity were found in perinuclear structures in which the presence of CryAB had already been reported [(Raju et al. 2011; Kopito 2000) Fig. 3c].

Transgenic over–expression of HSF1 reduces Aβ levels in brains of PDAPP mice

Transgenic HSF1+/0 mice show an enhanced heat shock response (Pierce et al. 2010). To determine whether the up-regulation of chaperone proteins is mechanistically linked to the decrease in Aβ levels in PDAPP mice chronically fed with a rapamycin-supplemented diet, we crossed PDAPP mice to HSF1+/0 transgenic mice and determined Aβ levels in brains of single-transgenic PDAPP and double-transgenic PDAPP/HSF1+/0 male progeny at 10 months of age. Double-transgenic PDAPP/HSF1+/0 mice had significantly reduced levels of both Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 (Fig. 4a and b) as compared with mice transgenic for PDAPP alone. This difference did not arise from changes in levels of the PDAPP precursor in PDAPP/HSF1+/0 brains, as levels of PDAPP were not significantly different among experimental groups (Fig. 4c and d). Thus, over-expression of HSF1+/0 in PDAPP transgenic brains significantly reduces Aβ levels in brain. Aβ deposition was not determined as plaques are not consistently detectable in PDAPP mice before 12 months of age.

Increased CryAB and Hsp90 expression in PDAPP/HSF1+/0 brains

Like PDAPP mice chronically fed with a rapamycin-supplemented diet, doubly transgenic PDAPP/HSF1+/0 mice showed significantly increased brain levels of CryAB (Fig. 4c and d) and Hsp90 (Fig. 4c and e). In contrast, levels of Hsp105 (Fig. 4 c and f) and GRP94 were unchanged in doubly transgenic PDAPP/HSF1+/0 mice. Higher CryAB levels were observed in animals carrying the HSF1 transgene irrespectively of their genotype for the PDAPP transgene (Fig. 4a and b). On the other hand, the increase in Hsp90 was only observed in animals transgenic for PDAPP, suggesting that the HSF1-induced increase in Hsp90 required stimulation by stress (Pierce et al. 2010), in this case likely arising from the accumulation of Aβ in PDAPP mice (Fig. 4a and e). Thus, over-expression of HSF1 in PDAPP brains increases levels of a subset of the group of chaperone proteins that were also up-regulated by rapamycin treatment (Fig. 1), including CryAB and Hsp90, but not of Hsp105. Although CryAB levels were increased in all mice carrying an HSF1 transgene, the up-regulation of Hsp90 in HSF1 transgenic animals was dependent on the coexpression of PDAPP and thus likely on the presence of Aβ in brain.

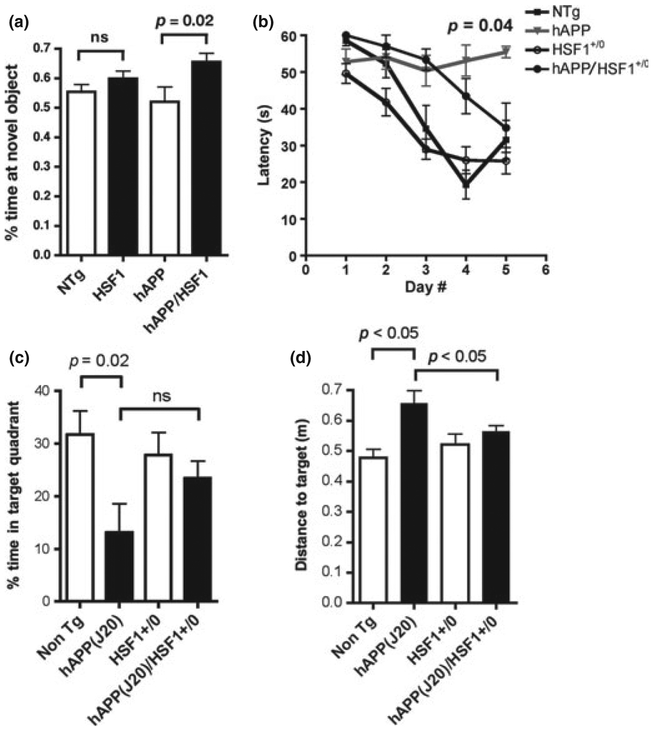

Transgenic over–expression of HSF1 ameliorates AD–like cognitive deficits in PDAPP mice

As over-expression of HSF1 was sufficient to lower Aβ levels in PDAPP/HSF1+/0 brains (Fig. 4), but increased only a subset of the chaperone proteins that were up-regulated by rapamycin, we sought to determine whether cognitive function would be affected by HSF1 over-expression in PDAPP/HSF1+/0 mice. To this aim, 10-week-old single and double-transgenic male progeny from the PDAPP × HSF1+/0 cross were tested with the novel object recognition task (Antunes and Biala 2012). PDAPP/HSF1+/0 mice showed significantly improved memory of a previously encountered object (p = 0.02, Fig. 5a), and this improvement was significant even when compared with non-transgenic animals (p = 0.02, Student’s t-test with Welch’s correction). anova could not be used to test significance of differences between group means because variance in the PDAPP transgenic group was significantly different from that of all other groups (F (11,11) = 3.811, p = 0.03, F test). No differences were observed in total time spent exploring (data not shown) between PDAPP and PDAPP/ HSF1+/0 mice, ruling out differences in motivation. Thus, over-expression of HSF1 significantly enhanced memory of a previously encountered object in young transgenic PDAPP mice.

Fig. 5.

Transgenic over-expression of heat-shock factor 1 (HSF1) ameliorates Alzheimer’s disease-like cognitive deficits in human amyloid precursor protein (PDAPP) mice. (a) Time exploring a novel object was significantly increased in PDAPP/HSF1 mice, indicating improved memory of a previously encountered object (p as indicated, Welch’s correction on Student’s t-test). (b) Although performance in the Morris water maze in PDAPP and PDAPP/HSF1 groups was significantly impaired with respect to that of non-transgenic (NTg) littermates (p < 0.001 and p < 0.01 for the comparison between NTg and PDAPP and NTg and PDAPP/HSF1, respectively, Bonferroni’s post hoc test applied to a significant effect of genotype, F(3,128) = 11.38, p < 0.0001, two-way anova), spatial learning in double-transgenic PDAPP/HSF1 mice was improved with respect to single-transgenic PDAPP mice in the last 2 days of training (p as indicated for the comparison between PDAPP and PDAPP/HSF1 groups, Welch’s correction on Student’s t-test. Welch’s correction was used because variances between PDAPP and PDAPP/HSF1 groups were significantly different, F(4,4) = 18.32, p = 0.01, F test). A significant interaction between day of training and performance for different genotypes was observed [F(12,128) = 2.79, p = 0.002]. Overall learning was effective [F(4,128) = 16.52, p < 0.0001, two-way anova] for all groups. (c) Time spent in the target quadrant in the probe trial was reduced in PDAPP mice with respect to non-transgenic littermates, as previously described (Chin et al. 2005; Galvan et al. 2006, 2008; Meilandt et al. 2009) (p value indicated, Welch’s correction on Student’s t-test). Time spent in the target quadrant was not significantly different between PDAPP and PDAPP/HSF1 groups. (d) Distance to the target (Gallagher proximity measure) was significantly larger for PDAPP mice with respect to all other experimental groups at all times during searching in a probe trial (p < 0.05, Tukey’s multiple comparison test applied to a significant effect of genotype on performance, p = 0.03, one-way anova). PDAPP/HSF1+/0 animals, however, spent most of the trial time searching for the platform at locations closer to its former position, in a manner indistinguishable from non-transgenic or HSF1+/0 single transgenic animals (p > 0.05 for both comparisons, p = 0.03, one-way anova). n = 8–18 animals/group. Data are means ± SEM.

Impairments in spatial memory are a frequent feature of the early stages of AD that is recapitulated in an age-dependent fashion in transgenic PDAPP mice (Hsia et al. 1999; Galvan et al. 2006, 2008). To determine whether HSF1 overexpression would affect spatial learning and memory in PDAPP/HSF1+/0 double-transgenic mice, we tested groups of male experimental animals with the Morris water maze task at 8 months of age, the earliest time at which PDAPP mice show consistent spatial learning and memory deficits (Hsia et al. 1999; Galvan et al. 2006, 2008). PDAPP transgenic animals showed increased floating (Figure S2), as previously described (Zhang et al. 2010). This was abrogated by HSF1 over-expression (Figure S2). As floating artificially lowers the values for distance swam, to avoid confounds arising from increased floating we used latency as a measure of performance. Although PDAPP animals showed profound deficits during acquisition, as described (Zhang et al. 2010; Hsia et al. 1999; Galvan et al. 2006, 2008), learning was significantly improved in PDAPP/HSF+/0 animals compared with single-transgenic PDAPP mice (Fig. 5b). PDAPP/HSF1+/0 mice, however, showed learning deficits when compared with non-transgenic littermates or to single HSF1+/0 transgenics (Fig. 5b). Thus, over-expression of HSF1 ameliorates but does not abolish AD-like spatial learning deficits in PDAPP mice. Consistent with these observations, PDAPP animals showed impaired memory (Fig. 5c). In spite of their learning improvements, the time spent in the target quadrant during the probe trial was increased but not significantly improved in PDAPP/HSF1+/0 mice (Fig. 5c). Measures of time spent in the target quadrant, however, may not detect subtle differences in search accuracy(Gallagher et al. 1993). To determine whether fine differences in retention might exist between PDAPP and PDAPP/HSF1+/0, we calculated Gallagher proximity (Gallagher et al. 1993) for all experimental groups. This measure, which can accurately resolve differences in search strategies by continuously computing the mouse’s proximity to the target over the course of the search (Gallagher et al. 1993), is a more precise measure of recall. Consistent with their impaired learning of the platform location, PDAPP mice were significantly further away from the former platform position than all other experimental groups at all times during the probe trial, when the platform was not available (p < 0.05, Tukey’s multiple comparison test applied to a significant effect of genotype on performance, p = 0.03, one-way anova, Fig. 5d). PDAPP/HSF1+/0 animals, however, spent most of the trial time searching for the platform at locations significantly closer to its former position, in a manner indistinguishable from non-transgenic or HSF1+/0 single transgenic animals (p > 0.05 for both comparisons, p = 0.03, one-way anova). Thus, consistent with the improvements observed in spatial learning in PDAPP/HSF1+/0 mice, these results suggest that over-expression of HSF1 in PDAPP/HSF1+/0 mice does not abolish but significantly ameliorates spatial memory deficits of PDAPP mice.

To compare the effect of HSF1 over-expression with that of rapamycin treatment (Spilman et al. 2010) on spatial learning and memory in PDAPP mice, we expressed performance of each experimental group in different experiments as a percent of the performance of the non-transgenic control group, using the average latencies at each day for the calculations. The results of that analysis revealed that while performance of control PDAPP animals was worse than that of non-transgenic mice at all times during spatial training, performance of rapamycin-treated and HSF1-overexpressing PDAPP animals approached that of non-transgenic animals in the last 2 days of training. Maximal performance (at the end of training) of both groups was improved with respect to control PDAPP mice to a comparable degree (Figure S3). The same was true for the measure of memory of the former location of the escape platform. Thus, HSF1 over-expression is comparable to chronic rapamycin treatment in improving spatial learning and memory in PDAPP mice.

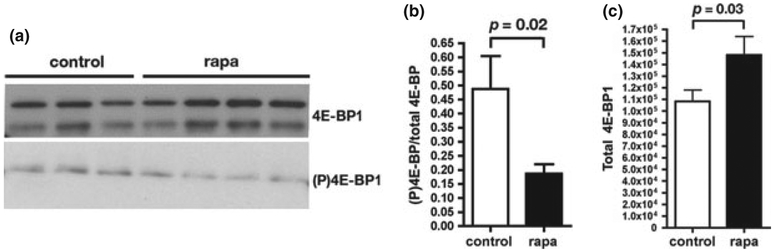

Thr37/Thr46–phosphorylation of 4E–BP is reduced in brains of rapamycin–fed PDAPP mice

We hypothesized that mechanism by which rapamycin induced the up-regulation of HSPs in PDAPP brains may involve rapamycin-induced inhibition of 4E-BP1 phosphorylation by mTOR, which would in turn inhibit cap-dependent protein synthesis and thus allow for the preferential translation of pre-existing HSP mRNAs (Panniers 1994; Beretta et al. 1996; Cuesta et al. 2000). To determine whether phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 in brains of PDAPP mice was affected by chronic rapamycin treatment, we determined levels of Thr(T)37/T46-phosphorylated 4E-BP1 (Gingras et al. 1999). T37/T46-phosphorylated 4E-BP1 levels were significantly reduced in brains of PDAPP mice chronically fed with a rapamycin-supplemented diet (Fig. 6a and b), suggesting that cap-dependent translation was inhibited in rapamycin-treated PDAPP brains. Moreover, overall levels of 4E-BP1 were significantly increased in rapamycin-treated PDAPP brain tissues (Fig. 6c), suggesting that chronic inhibition of cap-dependent protein translation by chronic rapamycin feeding may result in the up-regulation of 4E-BP1 as previously reported (Demontis and Perrimon 2010).

Fig. 6.

Reduced phosphorylation of 4E-BP in brains of rapamycin-fed human amyloid precursor protein (PDAPP) mice. (a) Representative immunoblots of 4E-BP and of P(T37/46)4E-BP in whole-brain extracts from control- and rapamycin-fed PDAPP mice. (b and c) Densitometric quantitation of (P)4E-BP (b) and of total 4E-BP (c) in whole-brain extracts of control- and rapamycin-fed PDAPP mice. p-values are indicated. Student’s t-test was used to determine significance of differences between means. Immunoblots for 4E-BP and for Thr37/46-phosphorylated 4E-BP were performed three times. n = 4–8 animals/group. Data are means ± SEM.

Discussion

Persistent mTOR activity has been reported in conditions of inflammation, cancer, diabetes (Inoki et al. 2002), and AD (Bove et al. 2011) and it has been suggested that PI3K/mTOR signaling attenuates the stress response by inhibiting Hsp70 translation (Sun et al. 2011), favoring the development of age-related pathologies. Deficiencies in insulin-PI3K-AKT signaling in AD have been reported (Liu et al. 2011), possibly resulting from Aβ induced inhibition of Akt/GSK-3β (Jimenez et al. 2011), which promotes cell death (Simon et al. 2011). The rapid increase in longevity observed in humans as compared with other great apes [occurring in the last < 100 000 years (Finch and Austad 2012)] is not associated with a lengthened reproductive lifespan. Thus, it has been suggested that there was little selective pressure to evolve effective mechanisms of neuroprotection in old age (Finch and Austad 2012). It is therefore conceivable that brain mTOR activity levels that are adequate during the reproductive years may become detrimental as humans age (Blagosklonny 2010; Kapahi 2010). The TOR pathway is central to the regulation of metabolic processes and it has also been implicated in the regulation of synaptic plasticity at nerve terminals (Hoeffer and Klann 2010). It has become increasingly apparent, however, that excessive excitability contributes significantly to cognitive impairment in AD (Palop and Mucke 2010; Bakker et al. 2012). We previously showed that chronic (> 16 weeks) feeding of PDAPP mice with a rapamycin-supplemented diet that partially inhibits mTOR activity in brain (Halloran et al. 2012; Spilman et al. 2010) preserves cognitive function in PDAPP mice modeling AD (Spilman et al. 2010), maintains memory in aged wild-type mice(Halloran et al. 2012), and enhances memory in younger C57BL/6J mice (Halloran et al. 2012). Thus, chronic partial inhibition of TOR may contribute to the amelioration of AD-like deficits in mice.

Chronic rapamycin feeding enhances autophagy in hippocampal neurons of PDAPP mice (Spilman et al. 2010) and other AD models (Caccamo et al. 2010). The data of this study indicate that chronic inhibition of mTOR induces another arm of the proteostatic response by augmenting HSPs in brains of mice modeling AD (Fig. 1 and 2), likely as a result of preferential translation of pre-existing mRNAs (Banerji et al. 1984; Theodorakis et al. 1988; Panniers 1994; Beretta et al. 1996; Morimoto 2008) in rapamycin-treated PDAPP brains, as in conditions of cellular stress(Panniers 1994; Cuesta et al. 2000).

The small chaperone CryAB was prominent among the chaperones up-regulated in rapamycin-treated PDAPP brains, both at the transcriptional and at the protein levels. Alpha-crystallins act as molecular chaperones by binding to partially denatured or otherwise functionally impaired proteins and maintaining them in large soluble aggregates (Basha et al. 2012; Shammas et al. 2011). CryAB is induced by over-expression of Aβ and it interacts with Aβ in Aβ-transgenic C. elegans (Fonte et al. 2002, 2008). Moreover, over-expression of the wild-type ortholog of CryAB, HSP16, in C elegans is sufficient to partially suppress Aβ toxicity (Fonte et al. 2008), and it was recently shown that binding of CryAB with Aβ fibrils inhibits fibril elongation (Shammas et al. 2011). In agreement with these data, CryAB was present in the proximity of Aβ-containing polypeptides (Aβ and/or Aβ-containing APP) in perinuclear structures (Gamerdinger et al. 2011; Raju et al. 2011; Ren et al. 2009) and this association was enhanced in PDAPP animals chronically fed with a rapamycin-supplemented diet (Fig. 3). The perinuclear distribution of CryAB and Aβ-immunoreactivity could reflect an interaction of cytosolic CryAB with Aβ-containing APP in transit through the endoplasmic reticulum. The subcellular localization of the CryAB/Aβ-containing polypeptide interaction in rapamycin-treated PDAPP brains, as well as the requirement for CryAB for the rapamycin-mediated reduction in brain Aβ levels remain to be determined.

Providing strong support for a key role of chaperones in the preservation of brain function during AD-like pathogenesis, transgenic over-expression of HSF1 in PDAPP mice mimicked the effect of chronic rapamycin feeding, resulting in significantly reduced brain Aβ levels (Fig. 4) and improved cognitive function (Fig. 5) in PDAPP/HSF1+/0 mice. Among the chaperones examined, only CryAB and HSP90, which has a crucial role in the feedback loop that controls HSF1 activity, were up-regulated in PDAPP/HSF1+/0 brains (Fig. 4). Even though Hsp90 is a major target of HSF1 transcriptional transactivation (Stephanou and Latchman 2011; Ali et al. 1998), our results and prior studies (Pierce et al. 2010) suggest that its up-regulation requires stress such as that arising from the accumulation of high levels of Aβ in PDAPP brains. Indeed, HSP90 has been shown to inhibit early stages of Aβ aggregation (Evans et al. 2006), thus potentially preventing the formation of toxic oligomeric forms of the peptide (Selkoe 2002; Kayed and Lasagna-Reeves 2012). Thus, our results suggest that HSP90 may be part of a protective response triggered by high Aβ levels that is mediated by activation of HSF1 in rapamycin-treated PDAPP brains.

HSP mRNAs are preferentially translated when cap-dependent translation is inhibited by different stress stimuli (Panniers 1994; Beretta et al. 1996; Cuesta et al. 2000). In agreement with the hypothesis that inhibition of mTOR by chronic rapamycin feeding may enable HSP synthesis by partially inhibiting cap-dependent translation, 4E-BP1 phosphorylation was decreased in rapamycin-treated PDAPP brains (Fig. 6). In addition, and similar to what is observed during stress (Tettweiler et al. 2005) and in conditions of caloric restriction (Zid et al. 2009), 4E-BP1 levels were increased in rapamycin-treated PDAPP brains (Fig. 6), further enforcing inhibition of eIF4E (Gingras et al. 1999).

As human Aβ is undetectable before 2.5 month of age, by 10 months of age brains of PDAPP mice have been exposed to human Aβ produced from the hAPP transgene for approximately three quarters of their lives (Hsia et al. 1999; Galvan et al. 2002). Chronic rapamycin treatment may continuously facilitate the brain’s response to ongoing proteotoxic stress by favoring the translation of chaperone proteins, which maintain proteostasis (Voisine et al. 2010; Morimoto 2008) and protect cells from damage associated with the accumulation of Aβ (Veereshwarayya et al. 2006; Wilhelmus et al. 2007; Treusch et al. 2009). Proteins belonging to other functional groups such as neuronal structure were induced as well, and could very well contribute to the neuroprotective effects of rapamycin. A previous proteomic study, however, did not reveal an up-regulation of chaperone proteins in rapamycin-treated Jurkat T cells (Grolleau et al. 2002). This may reflect differences in cell and tissue type-specific responses between immortalized T-lymphocyte cells treated with rapamycin in vitro and brain tissues chronically exposed to rapamycin in vivo.

In summary, our data suggest that the reduction in brain Aβ levels and the amelioration of cognitive deficits in PDAPP mice chronically fed with a rapamycin-supplemented diet (Halloran et al. 2012; Spilman et al. 2010) may be due, at least in part, to the preferential translation of HSP mRNAs as a consequence of rapamycin-mediated inhibition of cap-dependent translation, an effect that could be mimicked by HSF1 over-expression. Taken together with our previous studies, our results suggest that chronic rapamycin treatment may mimic the effect of nutrient deprivation on downstream effectors of the mTOR pathway, up-regulating proteostatic responses to stress (Kapahi et al. 2010; Taylor and Dillin 2011) such as the heat shock response (Saunders and Verdin 2009) and autophagy (Spilman et al. 2010; Caccamo et al. 2010), thus blocking or delaying the development of functional impairments in a mouse model of AD. Our data support the hypothesis that chronic mTOR inhibition delays aging, and that an important mechanism mediating this effect involves preventing or delaying the loss of proteostasis associated with increasing age. We propose that the failure of proteostasis associated with aging may be a key event that enables the initiation of pathogenic processes of AD.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Levels of HSP22 and HSP70 in brains of PDAPP mice are not affected by rapamycin treatment.

Figure S2. Increased floating in PDAPP mice.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms. Katrine Krueger for outstanding administrative assistance, as well as Mr. John Ramos and Ms. Elisabeth Romero for excellent animal husbandry. This study was supported in part by AG-NS-0726-10 New Scholar Award in Aging from the Ellison Medical Foundation, NIRG 04-1054 from the Alzheimer’s Association, and a UTHSCSA University Research Council Award from UTHSCSA to VG; by the San Antonio Nathan Shock Center of Excellence in the Basic Biology of Aging (AR and RS), RC2AG036613 NIH Recovery Act Grand Opportunities ‘GO’ grant to AR, and by 5T32AG021890 NIA Biology of Aging Training Grant Fellowship to S.H. The authors have no conflict of interests to report.

Abbreviations used:

- Aβ

amyloid-beta

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- CryAB

alpha B-crystallin

- HSF1

heat shock factor 1

- HSR

heat shock response

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- PDAPP

human amyloid precursor protein

Footnotes

Supporting information

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher’s web-site.

References

- Ali A, Bharadwaj S, O’Carroll R and Ovsenek N (1998) HSP90 interacts with and regulates the activity of heat shock factor 1 in Xenopus oocytes. Mol. Cell. Biol 18, 4949–4960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antunes M and Biala G (2012) The novel object recognition memory: neurobiology, test procedure, and its modifications. Cogn. Process 13, 93–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker A, Krauss GL, Albert MS, Speck CL, Jones LR, Stark CE, Yassa MA, Basset SS, Shelton AL and Gallagher M (2012) Reduction of hippocampal hyperactivity improves cognition in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Neuron 74, 467–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerji SS, Theodorakis NG and Morimoto RI (1984) Heat shock-induced translational control of HSP70 and globin synthesis in chicken reticulocytes. Mol. Cell. Biol 4, 2437–2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basha E, O’Neill H and Vierling E (2012) Small heat shock proteins and alpha-crystallins: dynamic proteins with flexible functions. Trends Biochem. Sci 37, 106–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beretta L, Gingras AC, Svitkin YV, Hall MN and Sonenberg N (1996) Rapamycin blocks the phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 and inhibits cap-dependent initiation of translation. EMBO J. 15, 658–664. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blagosklonny MV (2010) Revisiting the antagonistic pleiotropy theory of aging: TOR-driven program and quasi-program. Cell Cycle 9, 3151–3156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bove J, Martinez-Vicente M and Vila M (2011) Fighting neurodegeneration with rapamycin: mechanistic insights. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 12, 437–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caccamo A, Majumder S, Richardson A, Strong R and Oddo S (2010) Molecular interplay between mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), amyloid-beta, and Tau: effects on cognitive impairments. J. Biol. Chem 285, 13107–13120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin J, Palop JJ, Puolivali J, Massaro C, Bien-Ly N, Gerstein H, Scearce-Levie K, Masliah E and Mucke L (2005) Fyn kinase induces synaptic and cognitive impairments in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci 25, 9694–9703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu B, Zhong R, Soncin F, Stevenson MA and Calderwood SK (1998) Transcriptional activity of heat shock factor 1 at 37 degrees C is repressed through phosphorylation on two distinct serine residues by glycogen synthase kinase 3 and protein kinases Calpha and Czeta. J. Biol. Chem 273, 18640–18646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen E, Du D, Joyce D, Kapernick EA, Volovik Y, Kelly JW and Dillin A (2010) Temporal requirements of insulin/IGF-1 signaling for proteotoxicity protection. Aging Cell. 9, 126–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costes SV, Daelemans D, Cho EH, Dobbin Z, Pavlakis G and Lockett S (2004) Automatic and quantitative measurement of protein-protein colocalization in live cells. Biophys. J 86, 3993–4003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuesta R, Laroia G and Schneider RJ (2000) Chaperone hsp27 inhibits translation during heat shock by binding eIF4G and facilitating dissociation of cap-initiation complexes. Genes Dev. 14, 1460–1470. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demontis F and Perrimon N (2010) FOXO/4E-BP signaling in Drosophila muscles regulates organism-wide proteostasis during aging. Cell 143, 813–825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan B and Zhao K (2007) HMGA1 mediates the activation of the CRYAB promoter by BRG1. DNA Cell Biol. 26, 745–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ecroyd H and Carver JA (2009) Crystallin proteins and amyloid fibrils. Cell. Mol. Life Sci 66, 62–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eletto D, Dersh D and Argon Y (2010) GRP94 in ER quality control and stress responses. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol 21, 479–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans CG, Wisen S and Gestwicki JE (2006) Heat shock proteins 70 and 90 inhibit early stages of amyloid beta-(1–2) aggregation in vitro. J. Biol. Chem 281, 33182–33191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch CE and Austad SN (2012) Primate aging in the mammalian scheme: the puzzle of extreme variation in brain aging. Age (Dordr) 34, 1075–1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonte V, Kapulkin V, Taft A, Fluet A, Friedman D and Link CD (2002) Interaction of intracellular beta amyloid peptide with chaperone proteins. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 9439–9444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonte V, Kipp DR, Yerg J 3rd, Merin D, Forrestal M, Wagner E, Roberts CM and Link CD (2008) Suppression of in vivo beta-amyloid peptide toxicity by overexpression of the HSP-16.2 small chaperone protein. J. Biol. Chem 283, 784–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto M, Takaki E, Hayashi T, Kitaura Y, Tanaka Y, Inouye S and Nakai A (2005) Active HSF1 significantly suppresses polyglutamine aggregate formation in cellular and mouse models. J. Biol. Chem 280, 34908–34916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher M, Burwell R and Burchinal M (1993) Severity of spatial learning impairment in aging: development of a learning index for performance in the Morris water maze. Behav. Neurosci 107, 618–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvan V, Chen S, Lu D, Logvinova A, Goldsmith P, Koo EH and Bredesen DE (2002) Caspase cleavage of members of the amyloid precursor family of proteins. J. Neurochem 82, 283–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvan V, Gorostiza OF, Banwait S et al. (2006) Reversal of Alzheimer’s-like pathology and behavior in human APP transgenic mice by mutation of Asp664. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 7130–7135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvan V, Zhang J, Gorostiza OF, Banwait S, Huang W, Ataie M, Tang H and Bredesen DE (2008) Long-term prevention of Alzheimer’s disease-like behavioral deficits in PDAPP mice carrying a mutation in Asp664. Behav. Brain Res 191, 246–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamerdinger M, Kaya AM, Wolfrum U, Clement AM and Behl C (2011) BAG3 mediates chaperone-based aggresome-targeting and selective autophagy of misfolded proteins. EMBO Rep. 12, 149–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gingras AC, Gygi SP, Raught B, Polakiewicz RD, Abraham RT, Hoekstra MF, Aebersold R and Sonenberg N (1999) Regulation of 4E-BP1 phosphorylation: a novel two-step mechanism. Genes Dev. 13, 1422–1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gingras AC, Raught B, Gygi SP et al. (2001) Hierarchical phosphorylation of the translation inhibitor 4E-BP1. Genes Dev. 15, 2852–2864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grolleau A, Bowman J, Pradet-Balade B, Puravs E, Hanash S, Garcia-Sanz JA and Beretta L (2002) Global and specific translational control by rapamycin in T cells uncovered by microarrays and proteomics. J. Biol. Chem 277, 22175–22184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guettouche T, Boellmann F, Lane WS and Voellmy R (2005) Analysis of phosphorylation of human heat shock factor 1 in cells experiencing a stress. BMC Biochem. 6, 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halloran J, Hussong S, Burbank R et al. (2012) Chronic inhibition of mTOR by rapamycin modulates cognitive and non-cognitive components of behavior throughout lifespan in mice. Neuroscience 223, 102–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison DE, Strong R, Sharp ZD et al. (2009) Rapamycin fed late in life extends lifespan in genetically heterogeneous mice. Nature 460, 392–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartl FU, Bracher A and Hayer-Hartl M (2011) Molecular chaperones in protein folding and proteostasis. Nature 475, 324–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeffer CA and Klann E (2010) mTOR signaling: at the crossroads of plasticity, memory and disease. Trends Neurosci. 33, 67–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsia AY, Masliah E, McConlogue L, Yu GQ, Tatsuno G, Hu K, Kholodenko D, Malenka RC, Nicoll RA and Mucke L (1999) Plaque-independent disruption of neural circuits in Alzheimer’ s disease mouse models. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 3228–3233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu AL, Murphy CT and Kenyon C (2003) Regulation of aging and age-related disease by DAF-16 and heat-shock factor. Science 300, 1142–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ideker T and Krogan NJ (2012) Differential network biology. Mol. Syst. Biol, 8, 565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoki K, Li Y, Zhu T, Wu J and Guan KL (2002) TSC2 is phosphorylated and inhibited by Akt and suppresses mTOR signalling. Nat. Cell Biol 4, 648–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez S, Torres M, Vizuete M et al. (2011) Age-dependent accumulation of soluble amyloid beta (Abeta) oligomers reverses the neuroprotective effect of soluble amyloid precursor protein-alpha (sAPP(alpha)) by modulating phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt-GSK-3beta pathway in Alzheimer mouse model. J. Biol. Chem 286, 18414–18425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapahi P (2010) Protein synthesis and the antagonistic pleiotropy hypothesis of aging. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 694, 30–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapahi P, Chen D, Rogers AN, Katewa SD, Li PW, Thomas EL and Kockel L (2010) With TOR, less is more: a key role for the conserved nutrient-sensing TOR pathway in aging. Cell Metab. 11, 453–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapp LD and Lorsch JR (2004) The molecular mechanics of eukaryotic translation. Annu. Rev. Biochem 73, 657–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayed R and Lasagna-Reeves C (2012) Molecular Mechanisms of Amyloid Oligomers Toxicity. J. Alzheimers Dis doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-129001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilkenny C, Browne WJ, Cuthill IC, Emerson M and Altman DG (2010) Improving bioscience research reporting: the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol. 29, e1000412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knauf U, Newton EM, Kyriakis J and Kingston RE (1996) Repression of human heat shock factor 1 activity at control temperature by phosphorylation. Genes Dev. 10, 2782–2793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopito RR (2000) Aggresomes, inclusion bodies and protein aggregation. Trends Cell Biol. 10, 524–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D, Paik SR and Choi KY (2004) Beta-synuclein exhibits chaperone activity more efficiently than alpha-synuclein. FEBS Lett. 576, 256–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Lau A, Morris TJ, Guo L, Fordyce CB and Stanley EF (2004) A syntaxin 1, Galpha(o), and N-type calcium channel complex at a presynaptic nerve terminal: analysis by quantitative immunocolocalization. J. Neurosci 24, 4070–4081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Liu F, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K and Gong CX (2011) Deficient brain insulin signalling pathway in Alzheimer’s disease and diabetes. J. Pathol 225, 54–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynn EG, McLeod CJ, Gordon JP, Bao J and Sack MN (2008) SIRT2 is a negative regulator of anoxia-reoxygenation tolerance via regulation of 14–3-3 zeta and BAD in H9c2 cells. FEBS Lett. 582, 2857–2862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma XM and Blenis J (2009) Molecular mechanisms of mTOR-mediated translational control. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 10, 307–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manders EMM, Verbeek FJ and Aten JA (1993) Measurement of colocalization of objects in dual-color confocal images. J. Microsc 169, 375–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan DR, Christians E, Forster M et al. (2002) Heat shock transcription factor 2 is not essential for embryonic development, fertility, or adult cognitive and psychomotor function in mice. Mol. Cell. Biol 22, 8005–8014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meilandt WJ, Cisse M, Ho K, Wu T, Esposito LA, Scearce-Levie K, Cheng IH, Yu GQ and Mucke L (2009) Neprilysin overexpression inhibits plaque formation but fails to reduce pathogenic Abeta oligomers and associated cognitive deficits in human amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice. J. Neurosci 29, 1977–1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto RI (1998) Regulation of the heat shock transcriptional response: cross talk between a family of heat shock factors, molecular chaperones, and negative regulators. Genes Dev. 12, 3788–3796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto RI (2008) Proteotoxic stress and inducible chaperone networks in neurodegenerative disease and aging. Genes Dev. 22, 1427–1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morley JF and Morimoto RI (2004) Regulation of longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans by heat shock factor and molecular chaperones. Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 657–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris R (1984) Developments of a water-maze procedure for studying spatial learning in the rat. J. Neurosci. Methods 11, 47–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakai A (2009) Heat shock transcription factors and sensory placode development. BMB Rep. 42, 631–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palop JJ and Mucke L (2010) Amyloid-beta-induced neuronal dysfunction in Alzheimer’ s disease: from synapses toward neural networks. Nat. Neurosci 13, 812–818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panniers R (1994) Translational control during heat shock. Biochimie 76, 737–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce A, Wei R, Halade D, Yoo SE, Ran Q and Richardson A (2010) A Novel mouse model of enhanced proteostasis: full-length human heat shock factor 1 transgenic mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 402, 59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce A, Mirzaei H, Muller F et al. (2008) GAPDH is conformationally and functionally altered in association with oxidative stress in mouse models of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Mol. Biol 382, 1195–1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raju I, Kumarasamy A and Abraham EC (2011) Multiple aggregates and aggresomes of C-terminal truncated human alphaA-crystallins in mammalian cells and protection by alphaB-crystallin. PLoS ONE 6, e19876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rekas A, Ahn KJ, Kim J and Carver JA (2012) The chaperone activity of alpha-synuclein: utilizing deletion mutants to map its interaction with target proteins. Proteins 80, 1316–1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren PH, Lauckner JE, Kachirskaia I, Heuser JE, Melki R and Kopito RR (2009) Cytoplasmic penetration and persistent infection of mammalian cells by polyglutamine aggregates. Nat. Cell Biol 11, 219–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renkawek K, Voorter CE, Bosman GJ, van Workum FP and de Jong WW (1994) Expression of alpha B-crystallin in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 87, 155–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders LR and Verdin E (2009) Cell biology. Stress response and aging. Science 323, 1021–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schug J (2008) Using TESS to predict transcription factor binding sites in DNA sequence. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics 21, Unit 2.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe DJ (2002) Alzheimer’s disease is a synaptic failure. Science 298, 789–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shammas SL, Waudby CA, Wang S et al. (2011) Binding of the molecular chaperone alphaB-crystallin to Abeta amyloid fibrils inhibits fibril elongation. Biophys. J 101, 1681–1689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinohara H, Inaguma Y, Goto S, Inagaki T and Kato K (1993) Alpha B crystallin and HSP28 are enhanced in the cerebral cortex of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurol. Sci 119, 203–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon D, Medina M, Avila J and Wandosell F (2011) Overcoming cell death and tau phosphorylation mediated by PI3K-inhibition: a cell assay to measure neuroprotection. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 10, 208–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somasundaram T and Bhat SP (2004) Developmentally dictated expression of heat shock factors: exclusive expression of HSF4 in the postnatal lens and its specific interaction with alphaB-crystallin heat shock promoter. J. Biol. Chem 279, 44497–44503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spilman P, Podlutskaya N, Hart MJ, Debnath J, Gorostiza O, Bredesen D, Richardson A, Strong R and Galvan V (2010) Inhibition of mTOR by rapamycin abolishes cognitive deficits and reduces amyloid-beta levels in a mouse model of Alzheimer’ s disease. PLoS ONE 5, e9979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele AD, Hutter G, Jackson WS, Heppner FL, Borkowski AW, King OD, Raymond GJ, Aguzzi A and Lindquist S (2008) Heat shock factor 1 regulates lifespan as distinct from disease onset in prion disease. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 13626–13631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinkraus KA, Smith ED, Davis C, Carr D, Pendergrass WR, Sutphin GL, Kennedy BK and Kaeberlein M (2008) Dietary restriction suppresses proteotoxicity and enhances longevity by an hsf-1-dependent mechanism in Caenorhabditis elegans. Aging Cell 7, 394–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephanou A and Latchman DS (2011) Transcriptional modulation of heat-shock protein gene expression. Biochem. Res. Int 2011, 238601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Conn CS, Han Y, Yeung V and Qian SB (2011) PI3K-mTORC1 attenuates stress response by inhibiting cap-independent Hsp70 translation. J. Biol. Chem 286, 6791–6800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RC and Dillin A (2011) Aging as an event of proteostasis collapse. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol 3, a004440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tettweiler G, Miron M, Jenkins M, Sonenberg N and Lasko PF (2005) Starvation and oxidative stress resistance in Drosophila are mediated through the eIF4E-binding protein, d4E-BP. Genes Dev. 19, 1840–1843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theodorakis NG, Banerji SS and Morimoto RI (1988) HSP70 mRNA translation in chicken reticulocytes is regulated at the level of elongation. J. Biol. Chem 263, 14579–14585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonkiss J and Calderwood SK (2005) Regulation of heat shock gene transcription in neuronal cells. Int. J. Hyperthermia 21, 433–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treusch S, Cyr DM and Lindquist S (2009) Amyloid deposits: protection against toxic protein species? Cell Cycle 8, 1668–1674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veereshwarayya V, Kumar P, Rosen KM, Mestril R and Querfurth HW (2006) Differential effects of mitochondrial heat shock protein 60 and related molecular chaperones to prevent intracellular beta-amyloid-induced inhibition of complex IV and limit apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem 281, 29468–29478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincenz C and Dixit VM (1996) 14–3-3 proteins associate with A20 in an isoform-specific manner and function both as chaperone and adapter molecules. J. Biol. Chem 271, 20029–20034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voisine C, Pedersen JS and Morimoto RI (2010) Chaperone networks: tipping the balance in protein folding diseases. Neurobiol. Dis 40, 12–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelmus MM, de Waal RM and Verbeek MM (2007) Heat shock proteins and amateur chaperones in amyloid-Beta accumulation and clearance in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurobiol 35, 203–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Cao Z, Klein WL and Luo Y (2010) Heat shock treatment reduces beta amyloid toxicity in vivo by diminishing oligomers. Neurobiol. Aging 31, 1055–1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Gorostiza OF, Tang H, Bredesen DE and Galvan V (2010) Reversal of learning deficits in hAPP transgenic mice carrying a mutation at Asp664: a role for early experience. Behav. Brain Res 206, 202–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zid BM, Rogers AN, Katewa SD, Vargas MA, Kolipinski MC, Lu TA, Benzer S and Kapahi P (2009) 4E-BP extends lifespan upon dietary restriction by enhancing mitochondrial activity in Drosophila. Cell 139, 149–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Levels of HSP22 and HSP70 in brains of PDAPP mice are not affected by rapamycin treatment.

Figure S2. Increased floating in PDAPP mice.