Abstract

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) provides a noninvasive method for investigating brain morphology. Within the medial temporal lobe, special attention has been paid to the hippocampus (HC) and amygdala (AG) because of their role in memory, depression, emotion, and learning. Volume changes in these areas have been observed in conjunction with certain disease states, e.g. Alzheimer's disease, post-traumatic stress disorder, and depression. Aging has also been shown to result in gray matter volume loss of the overall brain, including the HC. With regard to gender specificity, results suggest a larger shrinkage for men of brain gray matter, with controversial observations being made for the HC.

With recently refined MRI acquisition and segmentation protocols, the HC and AG of 80 subjects in early adulthood (39 men and 41 women, age 18–42 years) were investigated. Whereas the volume of the AG appeared to be independent of age and gender, a significant negative correlation with age for both left and right HC was found in men (r = −0.47 and −0.44, respectively) but not in women (r = 0.01 and 0.02, respectively). The volume decline in men appeared to be linear, starting at the beginning of the third life decade and approximating 1.5% per annum. Using voxel-based regressional analysis, it was shown that changes with age occurred mostly in the head and tail of the HC. This finding underscores the need to include sociodemographic variables in functional and anatomical MRI designs.

Keywords: magnetic resonance imaging, voxel-based morphometry, hippocampus, amygdala, volume decline, age, gender

Magnetic resonance (MR) studies in the past have repeatedly demonstrated that aging is generally associated with decreases in gray matter and increases in CSF (Jernigan et al., 1990). Results from recent studies furthermore suggest that these changes begin earlier and result in a larger total volume loss in men than in women (Gur et al., 1991; Blatter et al., 1995; Coffey et al., 1998). With regard to the hippocampus (HC) and the medial temporal lobe (MTL), age-related changes have also been demonstrated by MR studies. Studies using segmentation protocols for quantitative assessment estimated the HC volume loss per year in healthy subjects to be in the range of 0.3% (Coffey et al., 1992), 1.5% (Jack et al., 1998), or 2.1% (Kaye et al., 1997). Evidence for MTL volume decline with age stems from studies that categorized atrophy from mild to severe, showing that more severe atrophy occurs in older subjects (Yoshi et al., 1988). Other methods that have been used to demonstrate volume changes in the MTL with age include the segmentation of the lateral ventricles, which are adjacent to the HC throughout their inferior rostrocaudal extent (Raz et al., 1997). However, in the MTL and specifically in the HC, whether age-related changes differ between gender is discussed controversially. Here, some studies report no gender differences in age-related changes in older (Coffey et al., 1992; Jack et al., 1998) and younger subjects (Yoshi et al., 1988; Raz et al., 1997), whereas others find the atrophy to be stronger in men (Golomb et al., 1993; Christiansen et al., 1994; Blatter et al., 1995) or in women (Murphy et al., 1996). Possible explanations for these controversial results can be seen in differences in image acquisition, differences in methods for quantification of specific medial temporal lobe volumes in the brain, and differences in the definition of the borders of the MTL structures to be assessed.

With the recent enhancements in MR image acquisition, analysis, and anatomical definitions (Laakso et al., 1997; Bartzokis et al., 1998;Convit et al., 1999; Pruessner et al., 2000), it is believed that a more reliable assessment of these structures can be performed. With this, a more precise investigation of the effects of sociodemographic variables on the morphology of medial temporal lobe structures becomes possible. The present study was designed to investigate possible effects of gender and age on the morphology of the HC and the amygdala (AG) in early adulthood. The structures were manually segmented from high-resolution MR images, and the resulting volumes were correlated with age separately for the group of men and women. In addition, the technique of voxel-based regressional analysis with structural MR images (Wright et al., 1995; Paus et al., 1999) was used to allow investigation of changes within the segmented structures.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects. The subjects for this study were chosen from the ongoing International Consortium of Brain Mapping (ICBM) initiative to create a statistical atlas of the normal adult brain (Mazziotta et al., 1995). Between 1995 and 1997, 150 subjects were recruited at the Montreal Neurological Institute for neurological and sociodemographic assessment and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanning. From those 150 subjects, 80 (39 male and 41 female) were chosen for the current study.

Sociodemographic and neurological assessment. Information about age, gender, handedness, education, and neurological and psychiatric condition was obtained directly from the subjects with a computerized self-report (Giedd et al., 1996). For the original selection, subjects had to be medication-free and not suffering from any mental or psychological problems in the past or present. Subjects were excluded if they had ever suffered from a head trauma with unconsciousness during infancy or adulthood. Furthermore, subjects had to be free of any acute physical diseases at the time of the scan. Any history of cardiovascular disease served as an exclusion criterion as well.

The further selection of 80 subjects for the purpose of this study was based on age, handedness, and years of education so that the two groups of men and women were comparable. Although this goal could not be reached completely, no statistical differences occurred between men and women with regard to these variables.

The subjects' age ranged from 18 to 42 years (mean age 25.09 ± 4.9 years). Of the 80 subjects, 10 were left-handed, 55 were right-handed, and 15 showed no clear preference for either hand.

MR image acquisition. MRI scans were obtained using a Siemens Magnetom 1.5 T system with a standard radio frequency head coil (Siemens Medical Systems, Montreal, Quebec, Canada). The protocol used as part of the ICBM initiative generates T1, T2, and proton density-weighted image volumes with a slice separation of 1 mm. For the purpose of this study, only the T1 weighted acquisition scans were used. These volumes were acquired using a three-dimensional (3-D) spoiled gradient echo acquisition with sagittal volume excitation (repetition time = 18, echo time = 10; flip angle = 30°; 140 contiguous 1 mm sagittal slices). The rectangular field of view for the sagittal images was 256 mm superior-inferior by 204 mm anterior-posterior.

MR image analysis. All images were transferred to a Silicon Graphics workstation (Silicon Graphics, Mountain View, CA). A combination of different algorithms was used to prepare the raw MRI volumes for manual segmentation. This process corrected for image intensity nonuniformities (Sled et al., 1998), linear stereotaxic transformation (Collins et al., 1994) into coordinates based on the Talairach atlas (Talairach and Tournoux, 1988), and resampling onto a 1 mm voxel grid before image segmentation using a linear interpolation kernel. It has been shown that the automatic stereotaxic transformation is as accurate as the manual procedure but shows higher stability (Collins et al., 1994). Also, the correction for image intensity has been proven to recover most of the artifacts present in the ICBM database (Sled et al., 1998).

Volumetric analysis was performed with the interactive software package DISPLAY developed at the Brain Imaging Center of the Montreal Neurological Institute. This program allows simultaneous viewing of volumes in coronal, sagittal, and horizontal orientations. Because of the contiguous 1 mm slices, the investigator can navigate through the brain in 1 mm intervals in all orientations. The software calculates volumes of labeled structures automatically. Regions of interest can be edited manually and semiautomatically by thresholding the image. The program also allows 3-D surface rendering and interactive manipulation.

Assessment of HC volume. The anatomical boundaries used for both HC and AG have been described in detail elsewhere (Pruessner et al., 2000). In short, the following procedures for delineation of HC and AG were used. The most posterior part of the HC was defined as the first appearance of ovoid mass of gray matter inferiomedial to the trigone of the lateral ventricle (TLV). The lateral border of the HC at this point was the TLV, whereas medially, the border of the HC was identified by white matter. Farther anterior, an arbitrary border was defined for the superior and medial border of the HC, to differentiate HC gray matter from the gray matter of the Andreas Retzius gyrus, the fasciolar gyrus, and the crus of the fornix. This border was defined by drawing a vertical line from the medial end of the TLV inferiorly to the parahippocampal gyrus and a horizontal line from the superior border of the quadrogeminal cistern to the TLV. The inferior border of the HC at this point was again identified by white matter.

For the HC body, the most visible inferiolateral layer of gray matter was excluded, assuming that it actually represents entorhinal cortex. Next, the white matter band at the superomedial level of the HC body, the fimbria, was included. If gray matter was found superior to the fimbria, the first row of gray matter was also included. The dentate gyrus, located between the four corpus ammonis (CA) regions in the hippocampal formation, together with the CA regions themselves and part of the subiculum, were included. The subiculum was divided by drawing a straight line with an angle of ∼45° from the most inferior part of the HC medially to the cistern if no white matter delineation was visible between these two structures. The lateral border at this point was identified by the inferior horn of the lateral ventricle. If the inferior horn was invisible, the caudally adjacent white matter was used as border. The quadrogeminal cistern defined the superomedial border of the HC.

The appearance of the HC head was defined by the emergence of the uncal recess of the HC head in the superomedial region of the HC. The most important structures for identification of lateral, anterior, and superior borders of the HC head were the uncal recess of the inferior horn of the lateral ventricle and the alveus. In addition to the coronal view, the sagittal and horizontal views were used for identification of the anterior border of the HC. In the superomedial part, the HC often forms a distinct protuberance, which can be best identified in the coronal plane. Also, the uncal cleft could often serve as a marker of the inferior border of the HC.

Assessment of AG volume. The AG is located in the superomedial temporal lobe, with the basal ganglia bordering superiorly and the entorhinal cortex bordering inferiorly. The posterior end of the AG was defined in the coronal and horizontal planes, at the point where gray matter first started to appear superior to the alveus and lateral to the HC. If the alveus was not visible, the inferior horn of the lateral ventricle was used as border. Although this landmark presents the danger of misaligning the border between the HC and AG, especially in subjects where an enlargement of the ventricular system is present, it was chosen for reasons of consistency across subjects. The superior border of the AG was arbitrarily defined by drawing a horizontal line between the superolateral part of the optical tract and the fundus of the inferior portion of the circular sulcus of the insula. This border was chosen to prevent erroneous inclusion of parts of the putamen and claustrum in the amygdaloid measurement. In some cases, the superior border of the AG could be identified as a small layer of white matter, which then was used for delineation of the AG.

For identification of the medial and lateral border, the horizontal view was used. The ambient cistern was used as the medial border after one layer of gray matter directly adjacent to the cistern was excluded, assuming that a clear separation from the cisternal area is impossible. Farther anterior, a semicircle drawn from the lateral end of the lateral ventricle to the alveus was used as an arbitrary landmark for the medial border, because the transition of AG to entorhinal cortex is not visible in MR images. The lateral border of the AG was defined by the lateral half of the semicircle. For the inferior border of the AG, the coronal images were used for best separation. The tentorial indentation served as a demarcation line between AG and entorhinal cortex by excluding the gray matter inferiolateral to the indentation. The anterior border of the AG was defined at the level of the closure of the lateral sulcus, which was identified in the horizontal plane.

Reliability assessment. The reliability of the manual segmentation method has been described elsewhere (Pruessner et al., 2000). In short, the intraclass intrarater and interrater reliability coefficient varied between r = 0.83 (interrater reliability for the right AG) and r = 0.95 (intrarater reliability for the left AG), indicating good accordance between raters and a good overall reliability of the protocol.

Statistical analysis. HC and AG mean volumes and SDs were calculated for the whole group and separately for men and women. To evaluate differences between HC/AG volumes for both hemispheres and gender differences, a two-factor (gender by hemisphere) mixed design ANOVA was calculated with the HC and AG volumes as dependent variables. To investigate whether the transformation into Talairach space had an effect on interhemispheric or gender differences, all calculations were also performed with the native volumes. The formula for transformation of the standard volumes back into native space is [standard volume = stereotaxic volume divided by (sx × sy ×sz)], where sx, sy, and szare the scaling factors of the linear transformation. To calculate associations of age with HC and AG volume, Pearson correlations were calculated with these variables separately for men and women.

To further describe age-related changes within the HC, a linear regression model was applied to the individual voxels of the HC of all subjects (Wright et al., 1995; Paus et al., 1999). This procedure allowed investigation of which part of the HC is correlated with age. The subjects' age acts as an independent variable, and the MR image signal intensity of each voxel acts as a dependent variable in the regression. Three preprocessing steps were performed with the MR images. First, the preprocessed MR images were blurred using a Gaussian smoothing kernel (full-width at half-maximum, 6 mm) to reduce the number of comparisons for the regressional analysis. Second, the labels of the original HC segmentation were used to create a probabilistic map of the HC for the group investigated. Third, this probabilistic map was then used as template to derive 3-D images of the HC from the blurred MR image of each subject. To examine the association between HC volume and age, the statistical significance of the relation between age and signal intensity was assessed for each voxel. The interesting parameter was the slope of the effect of age on the MR image signal intensity within the HC volume. The slope and its SD were estimated by least squares fitting of the linear model at each voxel. To derive at-statistic map, the voxels were divided by their SD. To determine whether a given peak was significant, we used the 3-D Gaussian random field theory, which corrected for the multiple comparisons performed within the voxels of the HC. With the number of comparisons made within the HC, values equal to or larger than t = 2.5 (p = 0.05) were considered significant (Worsley et al., 1997).

RESULTS

Demographic and brain volumetric data

Men and women in the current sample were matched for age (41 women: 24.7 ± 5.05 years; 39 men: 25.5 ± 4.7 years;t < 1; df = 38; p > 0.20) and handedness (41 women: 5 left-handed, 7 neither left nor right-handed, 29 right-handed; 39 men: 5 left-handed, 8 neither left nor right-handed, 26 right-handed). The resulting volumes from the manual segmentation of HC and AG for the whole group (n = 80) are shown in Table 1. The manual segmentation results are shown simultaneously in standard stereotaxic as well as native space.

Table 1.

Minimum and maximum, mean and SD for the right and left hippocampal and amygdaloid volumes (n = 80)

| Minimum | Maximum | Mean | SD | Coefficient of variation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RHC | 3483 | 5270 | 4300 | 431.4 | 0.1 |

| LHC | 3138 | 5096 | 4072 | 454.6 | 0.1 |

| RAG | 1016 | 2198 | 1476 | 230 | 0.14 |

| LAG | 1013 | 2348 | 1487 | 243.6 | 0.12 |

| RHC_n | 2542 | 4320 | 3264.9 | 419.5 | 0.13 |

| LHC_n | 2317 | 4249 | 3090.2 | 418.9 | 0.14 |

| RAG_n | 716 | 1708 | 1222.3 | 203.2 | 0.12 |

| LAG_n | 756 | 1973 | 1129 | 208.3 | 0.18 |

All values are mm3. RHC, Right hippocampus; LHC, left hippocampus; LAG, left amygdala; RAG, right amygdala; RHC_n, right hippocampus in native space (NS); LHC_n, left hippocampus (NS); LAG_n, left amygdala (NS); RAG_n, right amygdala (NS).

Effects of gender and hemisphere on brain volumetric data

Results of a two-factor within ANOVA (gender by hemisphere) showed no effect of gender on the HC (F < 1; df = 78;p > 0.20) but indicated a significant difference between right and left HC volume (F = 55.9; df = 78; p < 0.001), with the right HC being larger than the left (4300 vs 4072 mm3). The interaction between gender and hemisphere for the HC was not significant (F < 1; df = 78; p > 0.20). Also, no differences were found for the AG with regard to gender and left and right hemispheric volumes (all main and interaction effects with F < 1; df = 78; p > 0.20).

Effects of age and gender on brain volumetric data

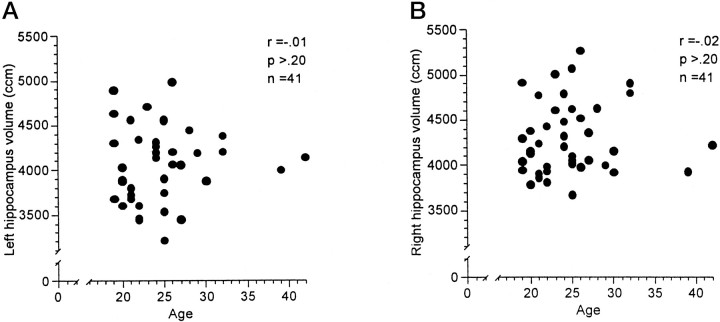

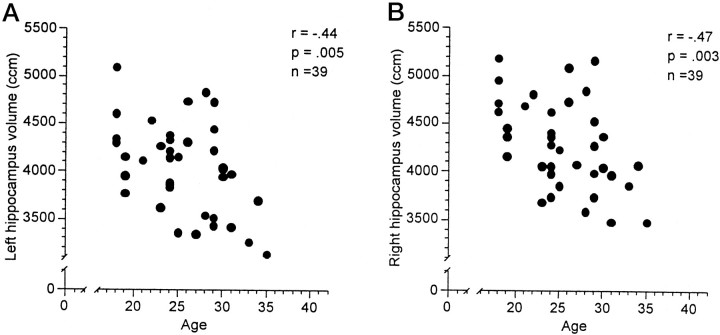

Possible associations between the subjects' age and HC and AG volumes were investigated using Pearson correlations. Table2 shows the results separately for men and women. The AG volumes appeared to be independent of age for men and women. HC volumes were not associated with age in the group of women. In the group of men, however, the subjects' age was significantly negatively correlated with left and right HC volumes. Figure1, a and b, shows the scatterplots for age and HC volume in the group of women. Figure2, a and b, shows the scatterplots for age and left and right HC volume in the group of men. The magnitude of the correlations suggests that age determined between 19 and 22% of the variability in the HC volumes in the group of men. The volume decline in men appears to be linear, starting at the beginning of the third life decade and approximating an annual volume loss of 1.5%.

Table 2.

Pearson correlations for the right and left hippocampal and amygdaloid volumes with age, in native and standard stereotaxic space, separately for men (n = 39) and women (n = 41)

| RHC | LHC | RAG | LAG | RHC_n | LHC_n | RAG_n | LAG_n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | −0.47 (p = 0.03) | −0.44 (p = .005) | −0.19 (p > 0.20) | −0.24 (p = 0.14) | −0.43 (p = .006) | −0.41 (p = 0.01) | −0.19 (p > 0.20) | −0.24 (p = 0.14) |

| Women | −0.02 (p > 0.20) | −0.01 (p > 0.20) | −0.13 (p > 0.20) | −0.02 (p > 0.20) | 0.06 (p > 0.20) | 0.07 (p > 0.20) | −0.08 (p > 0.20) | −0.07 (p > 0.20) |

All correlations are Pearson correlations. RHC, Right hippocampus, in standard stereotaxic space (STS); LHC, left hippocampus (STS); LAG, left amygdala (STS); RAG, right amygdala (STS); RHC_n, right hippocampus in native space (NS); LHC_n, left hippocampus (NS); LAG_n, left amygdala (NS); RAG_n, right amygdala (NS).

Fig. 1.

Scatterplots between left (A) and right (B) hippocampal volume and age in 41 healthy, normal women (age 18–42 years).

Fig. 2.

Scatterplots between left (A) and right (B) hippocampal volume and age in 39 healthy, normal men (age 18–36 years).

Results of the voxel-based morphometry with HC volumes

In the next step, the association between age and HC volume was investigated with a voxel-based linear regression model. The signal intensity of each blurred voxel of the HC entered the regressional model as dependent variable, whereas the age was entered as independent variable. The result of the linear regression model was a 3-Dt-statistic map of the size of the probabilistic map of the hippocampus. The regression model was applied separately to the group of men as well as to the group of women. For better visualization of the results of the regression, the 3-D t-statistic maps were co-registered on the respective average MRI brain image of the women or men in this study.

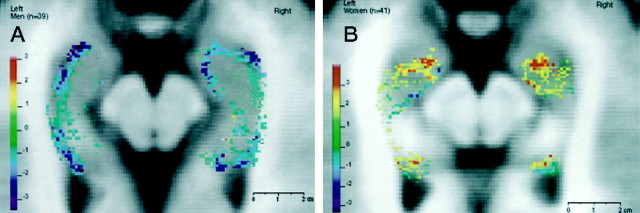

The regressional analysis revealed significant peaks oft-values (t > 2.5, p < 0.05; corrected) as a function of normalized signal intensity and age in the head of the HC as well as the tail. This was true for both men and women. Figure 3a shows the 3-D t-statistic map for men along the long axis of the HC. Here, significant negative t-values were found in the medial and lateral part of the right HC head (t = −2.9,p = 0.02) as well as in the lateral part of the left HC head (t = −3.1, p = 0.02). In the HC tail, small clusters of significant negative t-values were found in the posterior end of the HC tail in both the left (t = −3.0, p = 0.02) and right (t = −2.6, p = 0.03) hemisphere. In Figure 3b, the 3-D statistical map along the long axis of the hippocampus is shown for the group of women. In contrast to the group of men, it shows positive t-values in different portions of the HC head in the left (t = 3.2,p = 0.02) and right (t = 3.4,p = 0.01) hemispheres. Also, for both left and right hemispheres, small clusters of significant positive t-values for the group of women were found in the HC tail (t = 3.0, p = 0.02).

Fig. 3.

Transverse slice through the long axis of the hippocampus showing the results from the voxel-based regression analysis for women (A) and men (B).

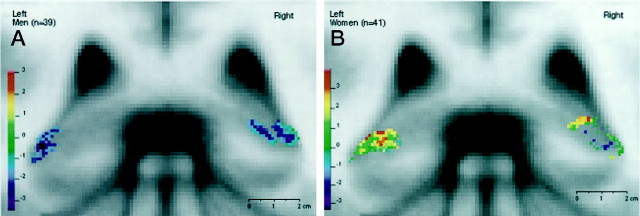

The t-values correspond to an increase or a decrease in the signal intensity of the original MR images. For the group of women, a significant increase in signal intensity of the MR image with age occurred in the head and tail of the HC, whereas a significant decrease in signal intensity appeared in the same regions in the group of men. Figures 4 and5 depict these results in coronal cuts perpendicular to the line connecting the anterior and posterior commissure. These projections allow specification of the significantt-value peaks with regard to their inferior–superior location. Figure 4a shows the 3-D t-statistic map for the HC head in the group of men. It can be shown in this view that the significant decrease of signal intensity with age is located in the medial and inferior portions of the right HC head and in the inferiolateral portions of the left HC head. These locations represent the area where the inferior horn of the lateral ventricle and its uncal recess are most often found. In contrast, in Figure 4b, which shows the same anterior portion of the HC head in the group of women, no negative peaks in the medial and lateral region of the HC head can be observed. Instead, a significant signal increase with age occurred in the superior portion of the HC head, in the transition region between HC and AG. In this region, the alveus is usually located, expanding from the medial border of the HC to the lateral part, where it borders the inferior horn of the lateral ventricle.

Fig. 4.

Coronal slice perpendicular to the anterior–posterior commissure line at the level of the HC head showing the results from the voxel-based regressional analysis for women (A) and men (B).

Fig. 5.

Coronal slice perpendicular to the anterior–posterior commissure line at the level of the HC tail showing the results from the voxel-based regressional analysis for women (A) and men (B).

In Figure 5a, the HC tail is shown for the group of men. Here, large clusters of significant signal decreases extending from the superior to the inferior portion of the HC were seen in both hemispheres. Figure 5b shows the group of women. Small clusters of signal increases can be seen in the superior part of the HC, where the fimbria is usually found.

Taken together, the results of this analysis clearly show a decrease in signal intensity in the HC head and tail of men. This intensity decrease was most prominent adjacent to the inferior horn of the lateral ventricle in the HC head and the trigone of the lateral ventricle in the HC tail. These findings can explain the volume differences found in the manual segmentation. In older men, these regions of the HC were more often classified as ventricle mass, which contributed to the observed volume decline with age. In women, the signal intensity increase in the head and tail of the HC occurred in a region where thin bands of white matter (alveus, fimbria) are attached to the HC. Because the segmentation protocol defined these white matter regions as part of the HC, a reclassification of tissue as white rather than gray matter in older women had no consequences for the overall HC volume. Thus, no correlation of volume with age was found in the group of women, despite signal-intensity changes.

DISCUSSION

The study results presented here suggest a significant gender difference with regard to HC volume decline with aging in early adulthood in healthy subjects. The HC and AG volumes of 39 men and 41 women were derived from high-resolution MR images translated into standard stereotaxic space before segmentation. No overall gender difference was apparent. However, although men showed a consistent decline between the third and fifth life decade with regard to HC volume, women in this age range remained constant. The calculated volume decline in men corresponds to an annual loss of 1.5%. For the AG, no changes with age were observed for either men or women.

These findings extend results from earlier studies in several aspects. First, age-related HC volume decline begins early in adulthood. Although previous studies reported a decline of brain volume beginning at the end of the second life decade, it was so far unknown whether this would also be true for structures of the medial temporal lobe or, more specifically, the HC (Jernigan et al., 1990). Jack et al. (1998)reported a volume decline of the HC with an annual rate of 1.5% for both men and women in a group of healthy elderly ranging from 70 to 89 years. Coffey et al. (1992) reported a smaller volume loss of 0.3% per annum for the amygdaloid–hippocampal complex in 76 healthy volunteers with an age range from 36 to 91, and Kaye et al. (1997) described a volume decline of 2.1% in the HC per year in subjects 84 years and older. The findings of the present study suggest that the age-related HC volume decline in men starts with the beginning of the third life decade.

Second, the HC volume decline with age is gender specific. Earlier studies suggested gender differences with regard to age-related volume decline of brain structures but not the HC. Interestingly, Gur et al. (1999) reported an almost identical correlation for volume decline of CNS gray matter for men in the same age range; for women, they reported a smaller yet significant decline of total gray matter as well. For medial temporal lobe gray matter, reports are conflicting. Although some studies reported stronger temporal lobe volume decline with age in men than in women (Cowell et al., 1994; Raz et al., 1997), others found no gender differences (Coffey et al., 1998) or reported greater temporal lobe atrophy in women than in men (Murphy et al., 1996). For the HC, no studies are available that show a gender-specific age-related volume decline. One study that reported men to have more atrophy in the HC assessed volume decline on a four-point scale. Also, the authors did not discuss the age onset of the HC volume decline (Golomb et al., 1993). The present study extends previous findings by showing that the HC is susceptible to gender-specific age-related decline starting in early adulthood, and it further allows estimation of the annual volume loss of this structure.

Third, morphometric changes of the HC with age seem to be located mostly in the head and tail of the HC, as revealed by the voxel-based regressional analysis. This is the first study to show region specificity of age-related processes within the HC in humans. This finding is in line with earlier suggestions that the HC head might be most susceptible to the influences of aging (Jack et al., 1997, 1998). In the present study, the HC tail also appears as a possible site for age-related changes.

Unfortunately, the interpretation of the findings of the voxel-based regressional analysis is restricted by the ambiguity of the observed signal-intensity changes in the MR images. Although a decrease of signal intensity with age in the anterior and posterior HC was observed in men, this was contrasted by an increase of signal intensity with age in women. This change of signal intensity in T1-weighted MR images can have a number of reasons. In the men, a shrinkage of the hippocampal volume with an expansion of the adjacent ventricles would explain the observed results. Other possibilities include pathological or inflammatory processes within the cells of the HC, which have been found to cause a signal decrease in T1 images (Baenziger et al., 1993;Kreft et al., 1999). Furthermore, changes in the iron content of cells can have a significant impact on the MR signal, and these might be age-related (Vymazal et al., 1995). However, the changes within the HC were observed only at the border and not throughout the structure, favoring a volume decline as a possible explanation. In the women, the signal-intensity increase could reflect an increase in white matter, which is supported by the notion that the increase occurred in regions where white matter bands border the hippocampus. However, changes in the iron content of the HC cells in the opposite direction than that of men could also lead to the observed signal-intensity changes. Overall, because none of these possibilities can be ruled out without access to histological data, the discussion about possible origins of the age-related changes in signal intensity has to remain speculative.

Other issues that need to be addressed when considering the results of this study include the reliability and validity of the methods that were used. These issues need to be considered separately for the manual segmentation as well as the voxel-based regressional analysis.

Regarding the segmentation protocol that was used, its reliability has been demonstrated recently (Pruessner et al., 2000). The reliability of the segmentation in this study is further supported by the notion that almost identical correlations between age and volume were observed in the left and right hemisphere for both men and women, verifying the magnitude of the correlation and the precision of the segmentation method itself. It can be assumed that imprecise and unreliable segmentation had resulted in a greater variability in the correlation coefficients across hemispheres. For the validity, it is believed that recent advancements in image acquisition, data processing, definition of structural boundaries, and 3-D analyzing software allowed a more precise morphometric analysis of HC and AG in this study (Mori et al., 1997; Jack et al., 1998; Van Paesschen et al., 1998; Ashtari et al., 1999; Pruessner et al., 2000). Earlier studies in this field have been compromised by inferior image quality and software restrictions in the available analyzing tools (Jack et al., 1989). The current study benefited from high-resolution MR images and three-dimensional imaging software for simultaneous segmentation in all dimensions. Further support for the validity stems from the fact that the rater was blind with regard to gender and age of the subjects, allowing an unbiased segmentation process.

Voxel-based regressional analysis is completely automated; therefore, reliability is no longer a concern. Recent studies using this method in conjunction with memory variables support the notion that this approach is valid for investigating morphometric changes in the HC (Maguire et al., 2000). Last, although the manual segmentation emphasized the quantitative aspects of the observed gender differences, the voxel-based regression revealed the differences within the structure. Although the interpretation of these results needs to be more qualitative, the Voxel-based regression extends the findings from the manual segmentation.

Unfortunately, questions regarding possible origins of the observed gender differences cannot be addressed in this study. Because no neuroendocrinological or neuropsychological measurements were included, any considerations in this regard will remain speculative. However, we wish to mention the recent increasing interest in the neuroprotective effect of estrogens on the brain (Sherwin, 1998). This argument could explain why gender differences were found in this study, because it investigated a population in which the hormonal differences between men and women are most pronounced. It could also explain why other studies investigating elderly populations failed to find gender effects on HC volume changes with aging, because estrogens are no longer available for women after menopause (Jack et al., 1998). In fact, most of the studies investigating HC volume changes with age have chosen elderly populations (Coffey et al., 1992; Jack et al., 1995, 1997).

Finally, it needs to be addressed which functional consequences this finding might have. Because the HC is known to be involved in spatial memory processes (Maguire et al., 2000) and recent studies were able to show a direct association between the HC volume and memory performance (Lupien et al., 1998), it can only be speculated whether men in early adulthood show a decline in these specific memory tasks when compared with women. However, to test for possible gender differences in HC morphology and its association with memory function, gender needs to be included as an independent variable in the respective study designs.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by the International Consortium for Brain Mapping, the Human Brain Project, and the German Research Foundation (Pr597/1-1).

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Jens C. Pruessner, McConnell Brain Imaging Centre, Montreal Neurological Institute, 3801 University Street, Suite WB 208, Montreal, Quebec, Canada H3A 2B4. E-mail:jens@bic.mni.mcgill.ca.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ashtari M, Greenwald BS, Kramer-Ginsberg E, Hu J, Wu H, Patel M, Aupperle P, Pollack S. Hippocampal/amygdala volumes in geriatric depression. Psychol Med. 1999;29:629–638. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799008405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baenziger O, Martin E, Steinlin M, Good M, Largo R, Burger R, Fanconi S, Duc G, Buchli R, Rumpel H. Early pattern recognition in severe perinatal asphyxia: a prospective MRI study. Neuroradiology. 1993;35:437–442. doi: 10.1007/BF00602824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartzokis G, Altshuler LL, Greider T, Curran J, Keen B, Dixon WJ. Reliability of medial temporal lobe volume measurements using reformatted 3D images. Psychiatry Res. 1998;82:11–24. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4927(98)00007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blatter DD, Bigler ED, Gale SD, Johnson SC, Anderson CV, Burnett BM, Parker N, Kurth S, Horn SD. Quantitative volumetric analysis of brain MR: normative database spanning 5 decades of life. Am J Neuroradiol. 1995;16:241–251. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christiansen P, Larsson HBW, Thomsen C. Age dependent white matter lesions and brain volume changes in healthy volunteers. Acta Radiol. 1994;35:117–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coffey CE, Wilkinson WE, Parashos IA. Quantitative cerebral anatomy of the aging human brain: a cross-sectional study using magnetic resonance imaging. Neurology. 1992;42:527–536. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.3.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coffey CE, Lucke JF, Saxton JA, Ratcliff G, Unitas LJ, Billig B, Bryan RN. Sex differences in brain aging: a quantitative magnetic resonance imaging study. Arch Neurol. 1998;55:169–179. doi: 10.1001/archneur.55.2.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collins DL, Neelin P, Peters TM, Evans AC. Automatic 3D intersubject registration of MR volumetric data in standardized Talairach space. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1994;18:192–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Convit A, McHugh P, Wolf OT, de Leon MJ, Bobinski M, De Santi S, Roche A, Tsui W. MRI volume of the amygdala: a reliable method allowing separation from the hippocampal formation. Psychiatry Res. 1999;90:113–123. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4927(99)00007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cowell PE, Turetsky BT, Gur RC, Grossman RI, Shtasel DI, Gur RE. Sex differences in aging of the human frontal and temporal lobe. J Neurosci. 1994;14:4748–4755. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-08-04748.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giedd JN, Snell JW, Lange N, Rajapakse JC, Casey BJ, Kozuch PL, Vaituzis AC, Vauss YC, Hamburger SD, Kaysen D, Rapoport JL. Quantitative magnetic resonance imaging of human brain development: ages 4–18. Cereb Cortex. 1996;6:551–560. doi: 10.1093/cercor/6.4.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Golomb J, de Leon MJ, Kluger A, George AE, Tarshish C, Ferris SH. Hippocampal atrophy in normal aging: an association with recent memory impairment. Arch Neurol. 1993;50:967–973. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1993.00540090066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Golomb J, Kluger A, de Leon MJ, Ferris SH, Mittelman M, Cohen J, George AE. Hippocampal formation size predicts declining memory performance in normal aging. Neurology. 1996;47:810–813. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.3.810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gur RC, Mozley PD, Resnick SM, Gottlieb GL, Kohn M, Zimmerman R, Herman G, Grossman R, Beretta D. Gender differences in age effect on brain atrophy measured by magnetic rensonace imaging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:2845–2849. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.7.2845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gur RC, Turetsky BI, Matsui M, Yan M, Bilker W, Hughett P, Gur RE. Sex differences in brain gray and white matter in healthy young adults: correlations with cognitive performance. J Neurosci. 1999;19:4065–4072. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-10-04065.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jack CR, Jr, Twomey CK, Zinsmeister AR, Sharbrough FW, Petersen RC, Cascino GD. Anterior temporal lobes and hippocampal formations: normative volumetric measurements from MR images in young adults. Radiology. 1989;172:549–554. doi: 10.1148/radiology.172.2.2748838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jack CR, Jr, Theodore WH, Cook M, McCarthy G. MRI-based hippocampal volumetrics: data acquisition, normal ranges and optimal protocol. Magn Reson Imaging. 1995;13:1057–1064. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(95)02013-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jack CR, Jr, Petersen RC, Xu YC, Waring SC, O'Brien PC, Tangalos EG, Smith GE, Ivnik RJ, Kokmen E. Medial temporal atrophy on MRI in normal aging and very mild Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1997;49:786–794. doi: 10.1212/wnl.49.3.786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jack CR, Jr, Petersen RC, Xu Y, O'Brien PC, Smith GE, Ivnik RJ, Tangalos EG, Kokmen E. Rate of medial temporal lobe atrophy in typical aging and Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1998;51:993–999. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.4.993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jernigan TL, Press GA, Hesselink JR. Methods for measuring brain morphologic features on magnetic resonance images: validation and normal aging. Arch Neurol. 1990;47:27–32. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1990.00530010035015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaye JA, Swihart T, Howieson D, Dame A, Moore MM. Volume loss of the hippocampus and temporal lobe in healthy elderly persons destined to develop dementia. Neurology. 1997;48:1297–1304. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.5.1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kreft B, Dombrowski F, Block W, Bachmann R, Pfeifer U, Schild H. Evaluation of different models of experimentally induced liver cirrhosis for MRI research with correlation to histopathologic findings. Invest Radiol. 1999;34:360–366. doi: 10.1097/00004424-199905000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laakso MP, Juottonen K, Partanen K, Vainio P, Soininen H. MRI volumetry of the hippocampus: the effect of slice thickness on volume formation. Magn Reson Imaging. 1997;15:263–265. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(96)00390-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lupien SJ, deLeon M, de Santi S, Convit A, Tarshish C, Nair NP, Thakur M, McEwen BS, Hauger RL, Meaney MJ. Cortisol levels during human aging predict hippocampal atrophy and memory deficits. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:69–73. doi: 10.1038/271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maguire EA, Gadian DG, Johnsrude IS, Good CD, Ashburner J, Frackowiak RS, Frith CD. Navigation-related structural change in the hippocampi of taxi drivers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:4398–4403. doi: 10.1073/pnas.070039597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mazziotta JC, Toga AW, Evans AC, Fox P, Lancaster J. A probabilistic atlas of the human brain: theory and rationale for its development. The International Consortium for Brain Mapping. NeuroImage. 1995;2:89–101. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1995.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mori E, Yoneda Y, Yamashita H, Hirono N, Ikeda M, Yamadori A. Medial temporal structures relate to memory impairment in Alzheimer's disease: an MRI volumetric study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1997;63:214–221. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.63.2.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murphy DGM, DeCarli C, McIntosh AR, Daly E, Mentis MJ, Pietrini P, Szcepanik J, Schapiro MB, Grady CL, Horwitz B, Rapoport SI. Sex differences in human brain morphometry and metabolism: an in vivo quantitative magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography study on the effect of aging. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:585–594. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830070031007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paus T, Zijdenbis A, Worsley K, Collins DL, Blumenthal J, Giedd JN, Rapaport JL, Evans AC. Structural maturation of neural pathways in children and adolescents: in vivo study. Science. 1999;283:1–4. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5409.1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pruessner JC, Li LM, Serles W, Pruessner M, Collins DL, Kabani N, Lupien S, Evans AC. Volumetry of hippocampus and amygdala with high-resolution MRI and three-dimensional analysis software: minimizing the discrepancies between laboratories. Cereb Cortex. 2000;10:433–442. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.4.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raz N, Gunning FM, Head D, Dupuis JH, McQuain J, Briggs SD, Loken WJ, Thornton AE, Acker JD. Selective aging of the human cerebral cortex observed in vivo: differential vulnerability of the prefrontal gray matter. Cereb Cortex. 1997;7:268–282. doi: 10.1093/cercor/7.3.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sherwin BB. Estrogen and cognitive functioning in women. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1998;217:17–22. doi: 10.3181/00379727-217-44200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sled JG, Zijdenbos AP, Evans AC. A nonparametric method for automatic correction of intensity nonuniformity in MRI data. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 1998;17:87–97. doi: 10.1109/42.668698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Talairach J, Tournoux P. Co-planner stereotaxic atlas of the human brain; 3-dimensional proportional system: an approach to cerebral imaging. Thieme; New York: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van Paesschen W, Duncan JS, Stevens JM, Connelly A. Longitudinal quantitative hippocampal magnetic resonance imaging study of adults with newly diagnosed partial seizures: one-year follow-up results. Epilepsia. 1998;39:633–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1998.tb01432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vymazal J, Hajek M, Patronas N, Giedd JN, Bulte JW, Baumgarner C, Tran V, Brooks RA. The quantitative relation between T1-weighted and T2-weighted MRI of normal gray matter and iron concentration. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1995;5:554–560. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880050514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Worsley KJ, Poline JB, Friston KJ, Evans AC. Characterizing the response of PET and fMRI data using multivariate linear models. NeuroImage. 1997;6:305–319. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1997.0294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wright IC, McGuire PK, Poline JB, Travere JM, Murray RM, Frith CD, Frackowiak RSJ, Friston KJ. A voxel-based method for the statistical analysis of gray and white matter density applied to schizophrenia. NeuroImage. 1995;2:244–252. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1995.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yoshi F, Barker WW, Chang JY. Sensitivity of cerebral glucose metabolism to age, gender, brain volume, brain atrophy and cerebrovascular risk factors. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1988;8:654–661. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1988.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]