Abstract

The hypothesis that the buffering of Ca2+ by mitochondria could affect the Ca2+-dependent inhibition of voltage-activated Ca2+ channels, (ICa), was tested in voltage-clamped bovine adrenal chromaffin cells. The protonophore carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl-hydrazone (CCCP), the blocker of the Ca2+ uniporter ruthenium red (RR), and a combination of oligomycin plus rotenone were used to interfere with mitochondrial Ca2+ buffering. In cells dialyzed with an EGTA-free solution, peak ICa generated by 20 msec pulses to 0 or +10 mV, applied at 15 sec intervals, from a holding potential of −80 mV, decayed rapidly after superfusion of cells with 2 μm CCCP (τ = 16.7 ± 3 sec;n = 8). In cells dialyzed with 14 mm EGTA, CCCP did not provoke ICa loss. Cell dialysis with 4 μm ruthenium red or cell superfusion with oligomycin (3 μm) plus rotenone (4 μm) also accelerated the decay of ICa. After treatment with CCCP, decay of N- and P/Q-type Ca2+ channel currents occurred faster than that of L-type Ca2+channel currents. These data are compatible with the idea that the elevation of the bulk cytosolic Ca2+ concentration, [Ca2+]c, causes the inhibition of L- and N- as well as P/Q-type Ca2+ channels expressed by bovine chromaffin cells. This [Ca2+]c signal appears to be tightly regulated by rapid Ca2+ uptake into mitochondria. Thus, it is plausible that mitochondria might efficiently regulate the activity of L, N, and P/Q Ca2+ channels under physiological stimulation conditions of the cell.

Keywords: mitochondrial Ca2+, Ca2+ channels, Ca2+-dependent inhibition of Ca2+ channels, chromaffin cells, L-type Ca2+ channels, N-type Ca2+channels, P/Q-type Ca2+ channels

The Ca2+-dependent inactivation of high-threshold voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels was first suggested in the pioneering work of Hagiwara and Nakajima (1966), subsequently proven by Brehm and Eckert (1978) andTillotson (1979), and later on extended to various excitable cells (Hagiwara and Byerly, 1981). Since then, various Ca2+ channel subtypes (L, N, P/Q, R) have been identified (García et al., 2000), but it is unclear whether all of them are equally prone to inactivation by Ca2+ entry or the elevation of the cytosolic concentration of Ca2+, [Ca2+]c. For instance, the cardiac and smooth muscle L-type Ca2+ channel is quickly inactivated after depolarization, with a time constant in the range of 50–100 msec (Yue et al., 1990; Giannattasio et al., 1991; Neely et al., 1994). However, the neuronal L-type Ca2+ channel is inactivated more slowly by the increase of [Ca2+]c(von Gersdorff and Matthews, 1996). The bovine adrenal chromaffin cell is a suitable model to reexamine this problem for two reasons: (1) this cell expresses L-, N- and P/Q-types of Ca2+ channels (Albillos et al., 1996), and (2) its mitochondria undergo large Ca2+ transients and hence its manipulation might produce drastic local changes of [Ca2+]c to cause the inhibition of Ca2+ channels.

On the other hand, the concept that mitochondria can act as rapid and reversible Ca2+ buffers during depolarization of neurons (Werth and Thayer, 1994; White and Reynolds, 1997; Pivovarova et al., 1999;Colegrove et al., 2000) and chromaffin cells (Herrington et al., 1996; Park et al., 1996; Babcock et al., 1997) is a recent one. Mitochondria can certainly sense the [Ca2+]c transients generated at subplasmalemmal domains (Rizzuto et al., 1994;Budd and Nicholls, 1996; Lawrie et al., 1996; Pivovarova et al., 1999), and reciprocally, Ca2+ uptake or release from mitochondria generate changes in local [Ca2+]c that modulate Ca2+ entry (Budd and Nicholls, 1996). However, the measured elevations of mitochondrial Ca2+ concentrations, [Ca2+]m, were only in the submicromolar or the low micromolar range (Rizzuto et al., 1994; Babcock et al., 1997; Brini et al., 1997). These small [Ca2+]mtransients could not account for the efficacy of mitochondria to sense the local [Ca2+]c of 20–50 μm likely occurring in the vicinity of Ca2+ channels in bovine chromaffin cells (Neher, 1998). This issue has been clarified recently by using mitochondrially targeted aequorins of low Ca2+affinity; we observed that mitochondria undergo surprising, rapid near-millimolar [Ca2+]m transients on activation of Ca2+ entry through Ca2+ channels into bovine chromaffin cells stimulated with short pulses of acetylcholine (ACh) or high K+ (Montero et al., 2000). These large [Ca2+]m can already account for the large and rapid changes of [Ca2+]ctaking place at subplasmalemmal sites during cell depolarization.

In this context, we thought that if we impaired the rapid sequestration of Ca2+ by mitochondria of the Ca2+ entering the cell during its depolarization, we could provoke larger and long-lasting [Ca2+]c at subplasmalemmal sites; in this manner, we should be able to study how these local [Ca2+]c elevations would affect the Ca2+ current through each Ca2+channel subtype (L, N, or P/Q) generated by test depolarizing pulses applied to voltage-clamped bovine chromaffin cells. By following this strategy, we have found that the three Ca2+ channel subtypes can undergo full inhibition by local [Ca2+]c elevations, although at different rates. We report here the experiments leading to these conclusions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation and culture of adrenal medulla chromaffin cells. Bovine adrenal medulla chromaffin cells were isolated following standard methods (Livett, 1984) with some modifications (Moro et al., 1990). Cells were suspended in DMEM supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum, 10 μmcytosine arabinoside, 10 μm fluorodeoxyuridine, 50 IU/ml penicillin, and 50 μg/ml streptomycin. They were plated on 1-cm-diameter glass coverslips at low density (5 × 104 cells per coverslip).

Current measurements and analysis. Ca2+(ICa), Ba2+(IBa), Na+(INa), and acetylcholine (IACh) currents were recorded using the whole-cell configuration of the patch-clamp technique (Hamill et al., 1981). Coverslips containing the cells were placed on an experimental chamber mounted on the stage of a Nikon Diaphot inverted microscope. During the preparation of the seal with the patch pipette, the chamber was continuously perfused with a control Tyrode solution containing (in mm): 137 NaCl, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 10 HEPES/NaOH, 0.005 tetrodotoxin (TTX), pH 7.4 (no TTX was added when measuringINa). Once the patch membrane was ruptured and the whole-cell configuration of the patch-clamp technique established, the cell being recorded was locally, rapidly, and continuously superfused with an extracellular solution of a composition similar to the chamber solution, but containing nominally 0 mm Ca2+ (no EGTA added;INa), 10 mmCa2+ (ICa), or 10 mm Ba2+(IBa) as charge carriers (see Results for specific experimental protocols). External solutions were rapidly exchanged using electronically driven miniature solenoid valves coupled to a multi-barrel concentration-clamp device, the common outlet of which was placed within 100 μm of the cell to be patched. The flow rate was ∼1 ml/min and regulated by gravity. Experiments were performed at room temperature (22–24°C). Cells were dialyzed with an intracellular solution containing (in mm): 10 NaCl, 100 CsCl, 20 TEA.Cl, 5 Mg.ATP, 0.3 Na.GTP, 20 HEPES/CsOH, pH 7.2; in some experiments (see Results) 14 mm EGTA was also included in the pipette solution.

Whole-cell recordings were made with fire-polished electrodes (resistance 2–5 MΩ when filled with the standard Cs+/TEA intracellular solution) mounted on the headstage of a DAGAN 8900 patch-clamp amplifier, allowing cancellation of capacitative transient and compensation of series resistance. A Labmaster data acquisition and analysis board and a 386-based microcomputer with pCLAMP software (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA) were used to acquire and analyze the data.

Cells were clamped at −80 mV holding potential (HP). Step depolarization to 0, +10, or +20 mV from this HP of different duration, were applied at various time intervals (see Results). Cells with pronounced rundown of ICa orIBa were discarded (Fenwick et al., 1982). Leak and capacitative currents were subtracted by using currents elicited by small hyperpolarizing pulses.

Measurements of changes of [Ca2+]c in fura-2-loaded chromaffin cells. Chromaffin cells were loaded with fura-2 by incubating them with fura-2 AM (4 μm) for 30 min at room temperature in Krebs-HEPES solution, pH 7.4, containing (in mm): 145 NaCl, 5.9 KCl, 1.2 MgCl2, 2.5 CaCl2, 10 Na-HEPES, 10 glucose. The loading incubation was terminated by washing several times the coverslip containing the attached cells, using Krebs-HEPES. The cells were then kept at 37°C in the incubator for 15–30 min. The fluorescence of fura-2 in single cells was measured with the photomultiplier-based system described by Neher (1989), which produces a spatially averaged measure of the [Ca2+]c. Fura-2 was excited with light alternating between 360 and 390 nm, using a Nikon 40× fluorite objective. Emitted light was transmitted through a 425 nm dichroic mirror and 500–545 nm barrier filter before being detected by the photomultiplier. [Ca2+]c was calculated from the ratios of the light emitted when the dye was excited by the two alternating excitation wavelengths (Grynkiewicz et al., 1985). Experiments were performed at room temperature (22–24°C).

Chemicals. Collagenase type A was purchased from Boehringer Mannheim (Madrid, Spain). DMEM, fetal calf serum, penicillin, and streptomycin were purchased from Life Technologies (Madrid, Spain). BSA, TTX, carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl-hydrazone (CCCP), ruthenium red, oligomycin, and rotenone were purchased from Sigma (Madrid, Spain). Other chemicals were obtained from either Sigma or Merck (Madrid, Spain).

Statistical analysis. Results are expressed as means ± SEM. The statistical differences between means of two experimental results were assessed by Student's t test or one-factor ANOVA by Scheffe F test. A value of p ≤ 0.05 was taken as the limit of significance.

RESULTS

Effects of CCCP on ICa in cells dialyzed with intracellular solutions with or without EGTA

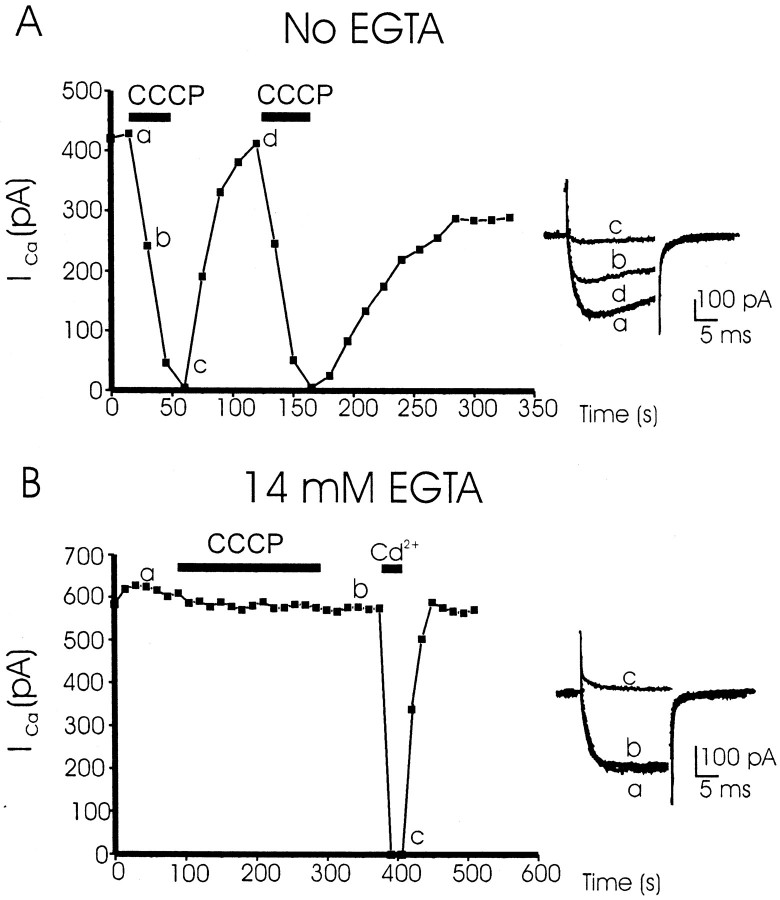

Experiments were designed to test how interference with the ability of mitochondria to sequester Ca2+ during cell activation modified the amplitude of peak inward Ca2+ channel currents. ICawas measured as indicated in Materials and Methods. In cells dialyzed with an EGTA-free intracellular solution, the current declined slowly and stabilized after 3–4 min. In eight cells, the current loss amounted to 35 ± 3% and had a time constant (τ) of 78 ± 11 sec. Cells with initial current decline that was not stabilized after 3 min were discarded. The cell of Figure1A shows an already stabilized initial ICa of 420 pA (peak current). Superfusion of the cell with CCCP caused almost full loss ofICa in 30 sec. The current quickly recovered during CCCP washout (in ∼30 sec). A second addition of CCCP again caused a loss of ICa in a reversible manner, but the recovery was partial, likely because of the absence of EGTA in the pipette that favors the rundown of Ca2+ channels (Fenwick et al., 1982). Original traces in theinset show that contrary to the cell dialyzed with 14 mm EGTA (B, trace a, inset), this cell exhibited clear current inactivation during the depolarizing pulse, before (A, trace a, inset) and during CCCP treatment (A, trace b, inset). The averaged initial ICaamplitude was 415 ± 68 pA (n = 8 cells). In the presence of CCCP, ICa was fully blocked with the much faster τ of 16.7 ± 3.4 sec. From now on we will call thisICa loss inhibition, to distinguish this effect from the classic Ca2+-dependent current inactivation occurring during cell depolarization (Hagiwara and Byerly, 1981).

Fig. 1.

CCCP provokes the inhibition ofICa in cells dialyzed with an EGTA-free intracellular solution, but not in the presence of EGTA. The two cells of A and B were voltage clamped at −80 mV and dialyzed with 14 mm EGTA (B) or with an intracellular solution without EGTA (A). To generate inward whole-cell Ca2+ channel currents (10 mm Ca2+ in the extracellular solution), cells were stimulated with 20 msec test depolarizing pulses to +10 mV at 15 sec intervals. Each black square shows the amplitude of peak ICa (ordinates) as a function of the time course shown in the abscissa. CCCP (2 μm) and Cd2+ (100 μm) were added with the extracellular solution (that continuously superfused the cells) during the time periods indicated by the horizontal black bars. Insets at the right in A and Bshow original current traces taken at the times shown by small letters. These are original records of two typical experiments, of eight for each protocol (see Results for averaged data).

The second cell (Fig. 1B) was dialyzed with an intracellular solution containing 14 mm EGTA to prevent surges of [Ca2+]c during cell activation. The initial peak ICa was >600 pA, and the current in this cell was fairly stable, both before and during the application for 3 min of the mitochondrial protonophore CCCP (2 μm). Applied at the end of the recording period, Cd2+ (100 μm) fully and reversibly inhibited ICa. OriginalICa traces showed no obvious inactivation (Fig.1B, inset). Averaged results obtained in cells dialyzed with EGTA using this protocol showed an initial ICaamplitude of 608.5 ± 4 pA (n = 8 cells); in the presence of CCCP, peak ICa decreased by only 5.32 ± 2% (n = 8).

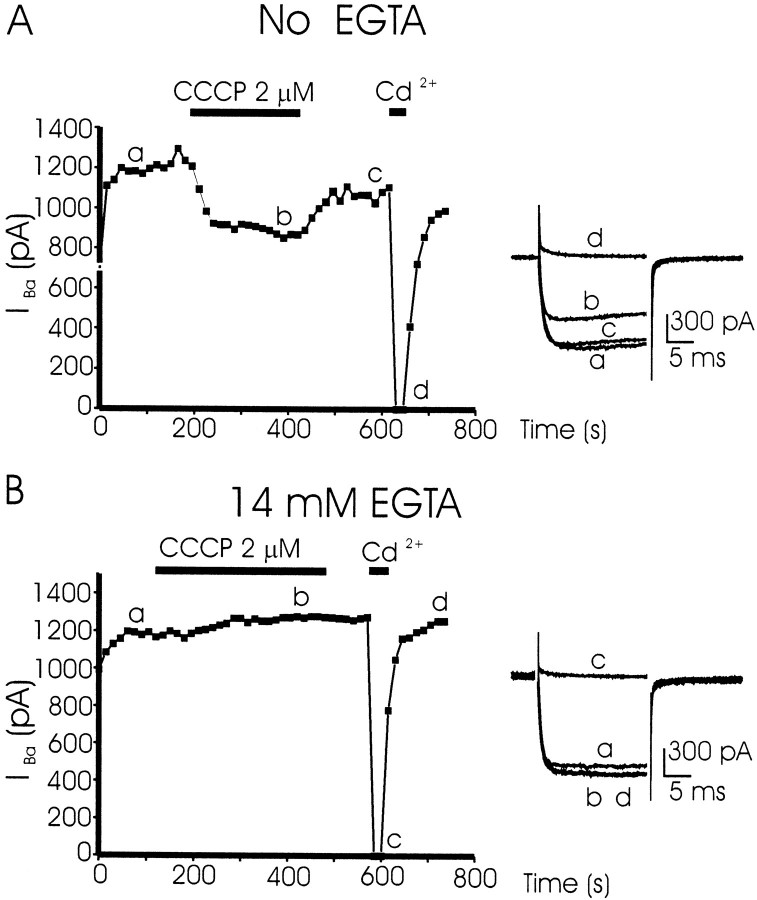

Similar experiments were performed using 10 mmBa2+ as charge carrier. As shown previously, Ba2+ generated greater peak currents than Ca2+ (Albillos et al., 1994): although the initial ICa in 20 cells averaged 493 ± 48 pA, the initial IBa of another 17 cells amounted to 854 ± 94 pA. The cell of Figure2A was dialyzed with an EGTA-free intracellular solution. The initialIBa of 1300 pA was reduced in CCCP to 900 pA in 1 min. Washout of CCCP allowed a partial gradual recovery of the current, which was fully blocked by Cd2+. Averaged results from nine cells gave an initial IBaamplitude of 783 ± 140 pA, which was reduced by 39 ± 4.9% in CCCP (τ of 76.9 ± 13 sec). In the cell of Figure2B that was dialyzed with 14 mm EGTA, the initial IBa amounted to 1200 pA. With 2 μm CCCP, the current measured along a 5 min period of cell superfusion remained unchanged. Cd2+ (100 μm) fully and reversibly blocked such current. In eight cells the initial IBa in the absence of CCCP was 933 ± 136 pA, and in its presence IBadecreased by only 5.3 ± 4%. Original current traces (insets at the right in A andB) show that IBa did not suffer inactivation during the depolarizing pulse, neither in the cell dialyzed with EGTA (B) nor in the cell dialyzed with an EGTA-free solution (A).

Fig. 2.

CCCP affects little the amplitudes of whole-cell Ba2+ currents (IBa), independently of cell dialysis with EGTA or with an EGTA-free intracellular solution. The cell of B was dialyzed with 14 mm EGTA and that of A with a solution deprived of EGTA. Cells were superfused with 10 mmBa2+ as charge carrier and stimulated with 20 msec test depolarizing pulses to +10 mV at 15 sec intervals to study the time course of their peak IBa. CCCP (2 μm) or Cd2+ (100 μm) was applied during the time periods shown by the horizontal black bars. Original traces at the right in A andB were taken at the times shown by small letters. Nine cells were tested for each protocol. Here we present the results obtained in one prototypical cell with each protocol. See Results for averaged results.

Time course of CCCP-induced inhibition ofICa and of its recovery, studied at high-frequency stimulation

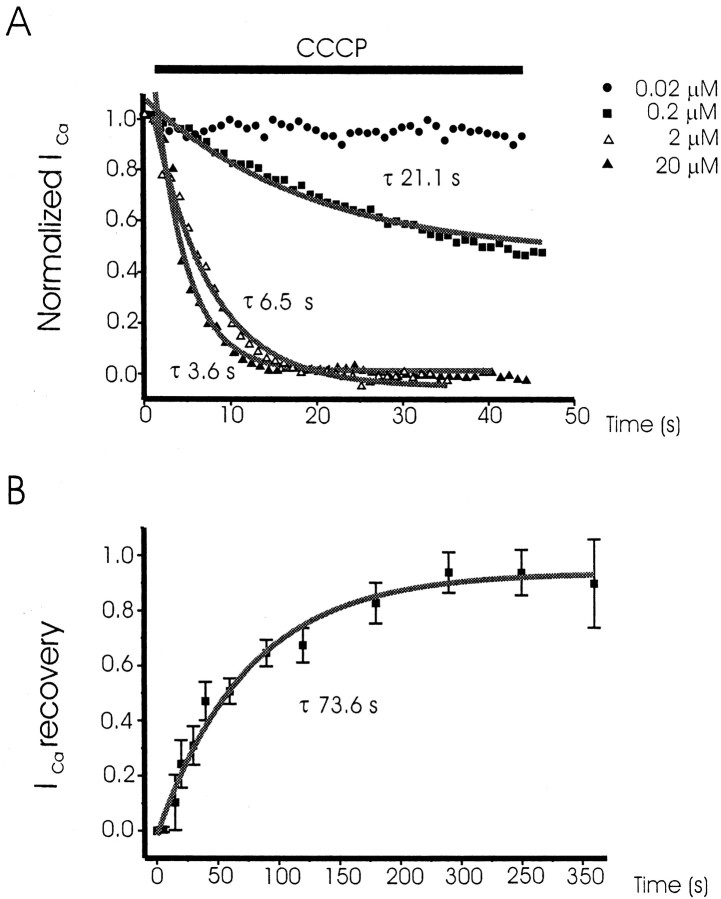

Under physiological conditions in the intact adrenal gland, chromaffin cell Ca2+ channels are likely recruited at intervals of 1 sec, because splanchnic nerves fire action potentials at ∼1 Hz. Hence, experiments were performed to studyICa decline during repetitive pulsing. Cells were dialyzed with an EGTA-free intracellular solution. In these experiments, control currents showed an initial decay of their amplitude during repetitive pulsing at 1 Hz; the peakICa decayed slightly to reach a steady state with a τ of 4.3 sec (n = 50 cells). OnceICa stabilized (in ∼15 sec), CCCP (0.02–20 μm) was given for 45 sec (Fig.3A). As shown in the Figure, the rate of ICa inhibition was dependent on the concentration of CCCP applied. Thus, at 0.02 μm,ICa peak was inhibited by only 6.3% at the end of the application period (45 sec). At 0.2 μm CCCP,ICa declined slowly (τ of 21.1 sec). At 2 and 20 μm CCCP, ICa declined much faster (τ of 6.5 sec at 2 μm and 3.6 sec at 20 μm CCCP). The highest concentrations used, 2 and 20 μm, inhibited ICa by 100%, with an average τ of 8.6 ± 1.8 sec (n = 15 cells) and 6 ± 0.7 sec (n = 18 cells), respectively. Blockade induced by 0.2 μm CCCP amounted to 52.1 ± 8.9%, with a τ of 25 ± 8.1 sec (n = 11 cells). No significant blockade of ICa was seen with 0.02 μm CCCP (6.3 ± 4.1% blockade;n = 6 cells). The one-factor ANOVA by ScheffeF test showed statistically significant differences between the low and high CCCP concentrations.

Fig. 3.

ICa generated by depolarizing test pulses applied at high frequency: inhibition by CCCP and recovery after its washout. Cells were dialyzed with an EGTA-free intracellular solution and superfused with a 10 mmCa2+-based extracellular solution. They were voltage clamped at −80 mV and 10 msec pulses to +10 mV applied at 1 sec intervals. A shows experiments performed with the concentrations of CCCP shown at the right. ICa was normalized as a fraction of the initial current peak. In B, ICa was elicited at 1 sec intervals by applying 20 msec depolarizing test pulses to +20 mV. Superfusion of CCCP (2 μm) provoked a progressive decline of peak ICa amplitude (data not shown). Currents were measured at the times shown in the abscissa after washout of CCCP.ICa that recovered after each washout time period was normalized as a fraction of the initialICa before CCCP (ordinate). Data are means ± SEM of 18 cells; τ for current recovery was 73.6 sec (n = 18 cells).

To study ICa recovery after blockade by CCCP, cells were superfused with 2 μm CCCP, which suppressed fully the current after 29 sec of pulsing. Then, CCCP was removed form the superfusion, and ICa was tested at different time intervals (5–240 sec) (Fig. 3B). At 5 sec there was no current recovery, but at 30 sec a sizable ICawas measured; after 2 min, most of the current was recovered. The current is expressed as a fraction of the initialICa; the recovery curve could be well fitted to a single exponential, showing a τ of 73.6 sec (n = 18 cells) (Fig. 3B).

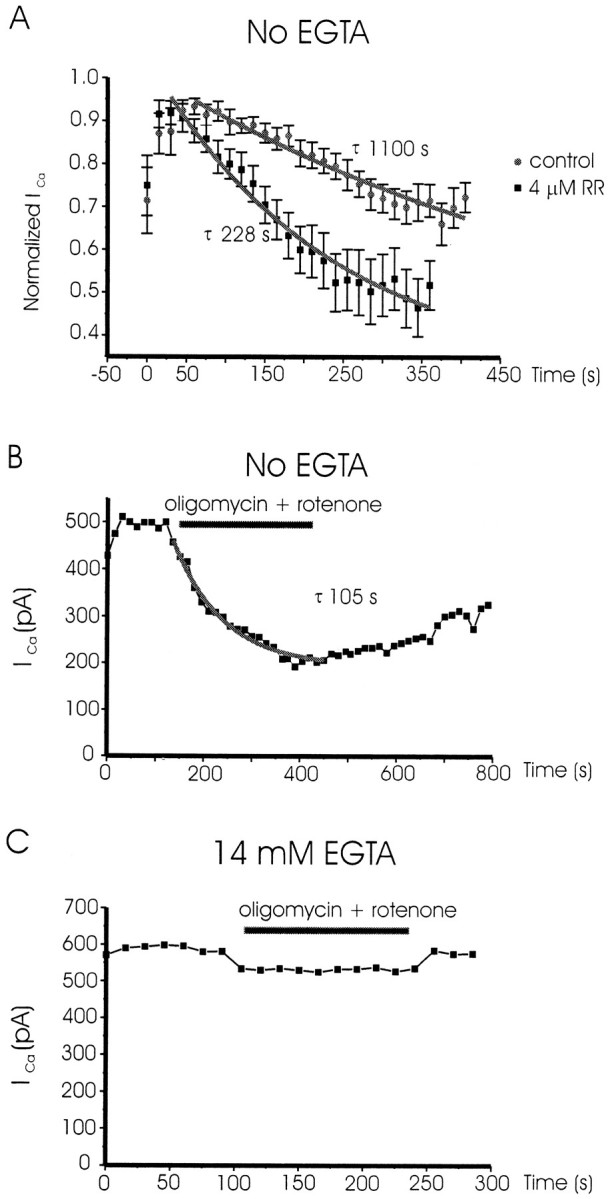

Effects on ICa of the intracellular application of ruthenium red

Another means of blocking Ca2+ sequestration by mitochondria was the direct inhibition of the Ca2+uniporter by RR (Montero et al., 2000). Because it is cell impermeant, this compound was given intracellularly by dialysis with the patch pipette. Figure4A shows averaged results obtained in chromaffin cells dialyzed with an EGTA-free solution in the absence (control) or the presence of RR (4 μm). The τ for the decay of ICain control cells was 1110 sec (n = 10 cells), whereas that of cells dialyzed with ruthenium red was 228 sec (n = 11 cells). The inhibition of peak current after 5 min recording was 24.5 ± 4.5% in control cells and 55.5 ± 6.5% in cells dialyzed with ruthenium red (p < 0.01). When EGTA (14 mm) was present in the intracellular solution, either with or without ruthenium red, no current inhibition was observed after 5 min stimulation (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

RR and oligomycin plus rotenone accelerated the inhibition of ICa with repetitive depolarizing pulsing. A shows averaged results (± SEM) obtained in 10 control cells (no RR) and in 11 cells dialyzed with RR. Cells were voltage clamped at −80 mV, dialyzed with an EGTA-free intracellular solution, and superfused with 10 mm Ca2+as charge carrier. ICa was elicited by 20 msec depolarizing test pulses to +10 mV, applied at 15 sec intervals.B and C show the effects of the superfusion with a solution containing oligomycin (3 μm) plus rotenone (4 μm) on two different cells dialyzed with 14 mm EGTA (C) or with an intracellular solution without EGTA (B). The cells were stimulated with 20 msec test depolarizing pulses to +10 mV at 15 sec intervals using 10 mm Ca2+ as charge carrier. Eachblack square shows the amplitude of peakICa as a function of the time course shown in the abscissa. Oligomycin plus rotenone was applied with the continued extracellular perfusion during the time periods indicated by thehorizontal black bars.

Effects of oligomycin plus rotenone on ICaamplitude in cells dialyzed with or without EGTA

Ca2+ uptake into mitochondria can be also blocked by using a combination of oligomycin plus rotenone. Oligomycin blocks mitochondrial ATP production by direct inhibition of the ATP synthase, whereas rotenone is a specific inhibitor of the electron transport chain that blocks electron transfer and proton extrusion mechanisms, thereby decreasing mitochondrial membrane potential and ATP synthesis. Thus, the dissipation of the negative membrane potential of the mitochondria will prevent the Ca2+ uptake by the uniporter, leading Ca2+ to accumulate near the Ca2+ channels.

The cell shown in Figure 4B was dialyzed with an intracellular EGTA-free solution. Once ICareached a stable value (∼500 pA), superfusion of the cell with a mixture of oligomycin (3 μm) plus rotenone (4 μm) caused the loss of ∼60% of the current in 3 min. After washout of the drugs, ICa recovered slowly and partially. In 11 cells, the superfusion of the cell with oligomycin plus rotenone induced a 67 ± 10% inhibition ofICa, with an averaged τ of 102 ± 12 sec.

Figure 4C shows a similar experiment in one cell dialyzed with an intracellular solution containing 14 mm EGTA. In this cell, superfusion with the mixture of oligomycin plus rotenone caused a small inhibition of ICa, which recovered fully after washout of the drugs. Averaged results obtained in EGTA-dialyzed cells shows an inhibition of 17 ± 1% ofICa (n = 3 cells). This inhibition of ICa in cells dialyzed with EGTA-containing solutions seems to be related to oligomycin, as proven by the fact that superfusion of cells with only oligomycin induced a similar inhibition (19 ± 4%; n = 4 cells), whereas superfusion with rotenone alone had no effect onICa in cells dialyzed with EGTA (data not shown).

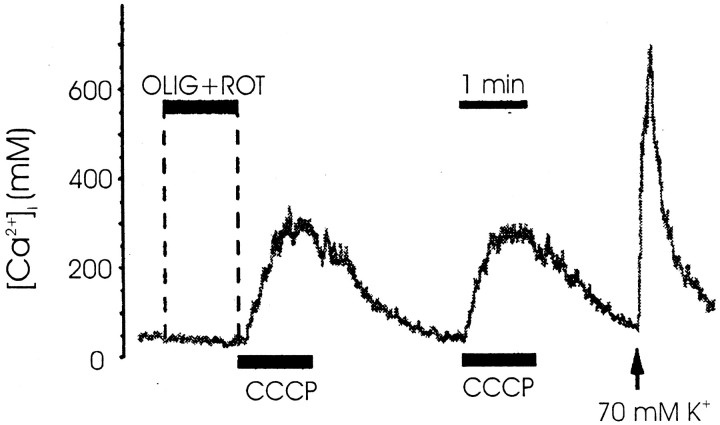

CCCP increased the [Ca2+]c in resting cells, whereas oligomycin plus rotenone did not

The differences observed between CCCP effects and those of oligomycin plus rotenone could be attributed to the ability of the former compound to release Ca2+ from mitochondria and other intracellular stores, in addition to its effect of preventing Ca2+ uptake into mitochondria. To test this possibility, we studied the effects of these compounds on the [Ca2+]c levels in single fura-2-loaded bovine chromaffin cells. In the cell shown in Figure5, superfusion of the cell with a solution containing oligomycin (1 μm) plus rotenone (4 μm) did not induce any significant change on [Ca2+]c. However, superfusion of the cells with 2 μm CCCP during 90 sec induced a fast increase of [Ca2+]c to approximately three to four times the basal levels (basal level amounted to 55 ± 1 nm; n = 10 cells). As shown in the Figure, effects of CCCP were reversible and reproducible after a second application of the compound. Similar results were obtained in the other eight cells, in which application of CCCP induced an increase of [Ca2+]c levels to a peak of 187 ± 19 nm.

Fig. 5.

Changes in the [Ca2+]c in fura-2-loaded cells induced by CCCP, oligomycin, and rotenone. Typical records of changes in the [Ca2+]c in one fura-2-loaded chromaffin cell are shown. The cell was superfused for 90 sec with CCCP (2 μm) or a mixture of oligomycin (1 μm) plus rotenone (4 μm), as shown by the horizontal bars. At the end of the experiment, after the washout of CCCP, a K+ pulse (70 mm isotonic K+, 2.5 mm Ca2+, 5 sec) was applied as shown by the arrow to assess the viability of the cell. The [Ca2+]c is expressed in nanomolar (ordinate). Similar results were obtained in the other eight cells (see Results for averaged results).

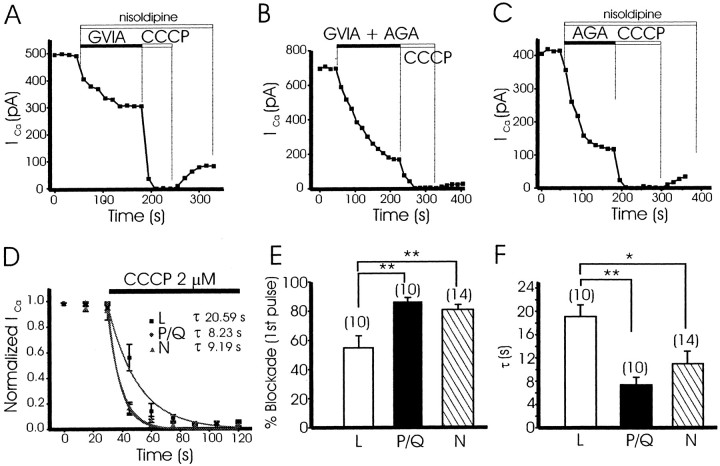

Different effects of CCCP on the various subtypes of Ca2+ channels in chromaffin cells

We have studied the effects of the superfusion with CCCP (2 μm) on L-, N-, and P/Q-type Ca2+channels in bovine chromaffin cells. In these experiments, cells were dialyzed with an intracellular EGTA-free solution. To isolate P/Q-type Ca2+ channels, cells were superfused with a combination of nisoldipine (an L-type Ca2+ channel blocker; 3 μm) plus ω-agatoxin GVIA (an N-type Ca2+ channel blocker; 1 μm). To isolate N-type Ca2+ channels, cells were superfused with a combination of nisoldipine plus ω-agatoxin IVA (a P/Q-type Ca2+ channel blocker; 2 μm). To isolate L-type Ca2+ channels, cells were superfused with ω-conotoxin GVIA (1 μm) plus ω-agatoxin IVA (2 μm).

Figure 6A shows a typical experiment in a cell treated with nisoldipine plus ω-conotoxin GVIA. Once the current stabilized, we studied the effects of CCCP on the remaining current, mostly P/Q Ca2+channel current, by superfusing the cell with 2 μm CCCP. This treatment led to a prompt decrease ofICa, which slowly and partially recovered after washout of CCCP. Averaged results showed that under these conditions, ICa was inhibited by 86.4 ± 3% (n = 10) in the first 10 sec of superfusion with CCCP (Fig. 6E). Inhibition ofICa was almost complete and developed with a τ of 7.2 ± 1 sec (n = 10 cells) (Fig.6D,F). When cells were treated with a combination of ω-conotoxin GVIA plus ω-agatoxin IVA to isolate the L-type Ca2+ channel current (Fig.6B), superfusion of the cells with 2 μmCCCP induced a slower blockade of the remaining L-type Ca2+ channel current, with a τ of 19.1 ± 2 sec (n = 10 cells) (Fig.6D,F). Only 54 ± 8% (n= 10 cells) of the ICa was blocked during the first depolarizing pulse in the presence of CCCP (Fig.6E). Finally, in cells treated with ω-agatoxin IVA plus nisoldipine to isolate N-type channel currents, superfusion of the cells with 2 μm CCCP induced a fast (τ of 11.4 ± 1 sec; n = 14 cells) (Fig. 6C,F) and almost complete blockade of ICa of 80.5 ± 4% in the first depolarizing pulse (n = 14 cells) (Fig. 6E).

Fig. 6.

CCCP caused a faster inhibition ofICa through non-L, as compared with L-type Ca2+ channels. Cells were voltage clamped at −80 mV and stimulated with 20 msec test depolarizing pulses to +10 mV at 15 sec intervals using 10 mm Ca2+ as charge carrier and dialyzed without EGTA. A shows the time course of peak ICa recorded in one cell superfused with nisoldipine (3 μm) and ω-conotoxin GVIA (GVIA; 1 μm) to block L- and N-type Ca2+channels, as well as the blocking effects of CCCP (2 μm) of the remaining current. B shows a similar experiment in which N- and P/Q-type Ca2+ channels were blocked by superfusing the cell with GVIA and ω-agatoxin IVA (AGA; 2 μm); after this, CCCP was applied at 2 μm.C shows an experiment in which L- and P/Q-type Ca2+ channels were blocked by superfusing the cell with nisoldipine and ω-agatoxin IVA; after this, CCCP was applied at 2 μm. D shows the normalized averaged time course of CCCP effects under these conditions. Blockade of N- and P/Q-type Ca2+ channels developed faster, with a τ of 9.2 sec (n = 14) and 8.2 sec (n = 10 cells), respectively, than that of L-type Ca2+ channels (τ = 20.6 sec;n = 10 cells) as shown in F. Eshows averaged data of the blockade of the first depolarizing pulse induced by CCCP under each experimental condition. The data are means ± SEM of 10–14 cells. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001.

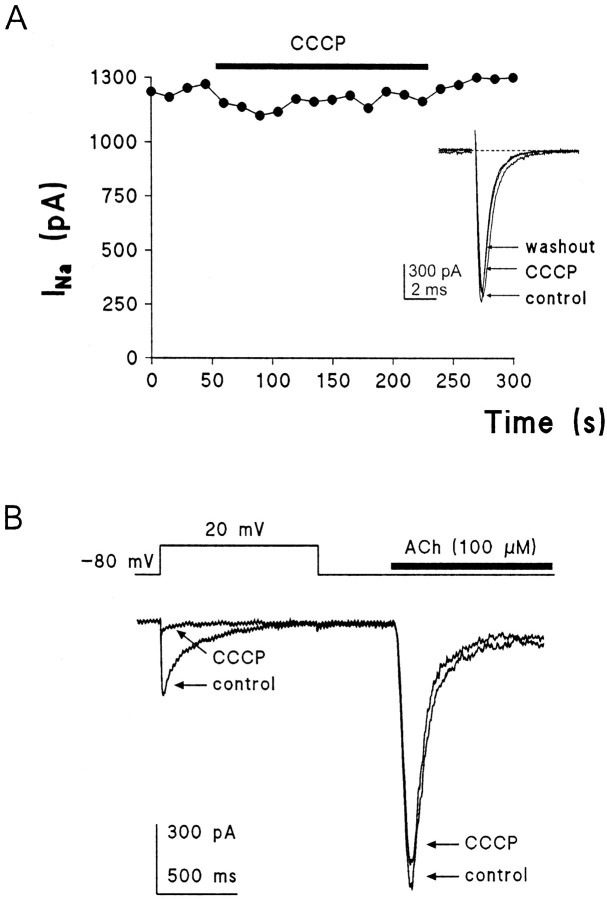

Effects of CCCP on Na+ channel currents and nicotinic receptor currents

It was of interest to test the specificity of the effects of CCCP on Ca2+ channel currents; thus, its effects on Na+ channel currents and nicotinic receptor currents were also studied. Figure 7Ashows the time course of peak INa in a chromaffin cell dialyzed with an EGTA-free solution. Test pulses to −10 mV produced initial INa of near 1200 pA amplitude. Addition of 2 μm CCCP for 2 min did not affect significantly the amplitude of the current; neither the kinetics of activation nor the kinetics of inactivation of the current was affected, as seen in the original INa traces shown in the inset. The τ for inactivation ofINa before CCCP was 1 msec, and after 90 sec superfusion with CCCP the τ amounted to 0.998 msec (inset). Averaged results obtained with this protocol show a peak INa amplitude of 851 ± 119 pA (10 cells) and 800 ± 113 pA (10 cells), respectively, before and during CCCP superfusion (6.1% of current inhibition); the τ values for INa inactivation were 0.997 ± 0.001 and 0.998 ± 0.001 msec, respectively.

Fig. 7.

Inward currents through voltage-dependent Na+ channels (INa) and through nicotinic receptor channels (IACh) were not affected by CCCP.A shows the time course of peak INaelicited by 16 msec depolarizing test pulses to −10 mV, applied at 15 sec intervals to a cell voltage clamped at −80 mV. The cell was superfused with an extracellular solution containing 137 mmNa+ and 0 mm Ca2+ and dialyzed with an intracellular EGTA-free solution. CCCP was superfused as shown by the black horizontal bar. Insets show original traces taken immediately before (control), at 90 sec of superfusion with CCCP, and 2 min after washout of CCCP. Similar results were obtained in the other nine cells; averaged values ofINa for all cells are given in Results. The stimulation protocol for recording of IACh is shown at the top of B. The cell was voltage clamped at −80 mV, and then stimulation was applied at 120 sec intervals as follows. First, a 1 sec depolarizing pulse to +20 mV was applied, and then, after 300 msec, an acetylcholine (ACh) pulse of 500 msec duration was given. Typical current traces obtained before (control) and at the 90 sec of superfusion with 2 μm CCCP are shown.

The protocol used to explore sequentially the effects of CCCP on Ca2+ channels and nicotinic receptor channel currents is shown at the top of Figure 7B. The control trace shows first the ICa generated by a long (1 sec) depolarizing pulse to +20 mV, followed by the current induced by 500 msec application of 100 μm ACh (IACh). ICa (372 pA) inactivated with a τ of 120.2 msec. IAChhad a greater amplitude (1160 pA) and desensitized with a τ of 98.5 msec. In the presence of 2 μm CCCP (120 sec superfusion), peak ICa was greatly inhibited (20.5 pA) butIACh was unaffected (1049 pA), showing a τ for its desensitization of 92.3 msec. In 17 cells,ICa (in 10 mmCa2+) amounted to 284 ± 36 pA and was reduced to 63 ± 88 pA in the presence of CCCP (75% current inhibition). However, IACh was 1091 ± 98 and 972 ± 95 pA, before and after superfusion of the cells with 2 μm CCCP (∼11% of current loss).

DISCUSSION

The central finding of this study was the inhibition by CCCP of the amplitude of peak ICa generated by repeated depolarizing pulses of voltage-clamped chromaffin cells. This effect seemed to be quite selective for Ca2+ channel currents. In fact, other inward currents through voltage-dependent Na+ channels or nicotinic receptor channels were scarcely affected by CCCP.

Because it is an uncoupler of oxidative phosphorylation, CCCP could cause ATP depletion and a deficit of energy supply to Ca2+-ATPases and hence inhibition ofICa. However, the intracellular pipette solution contained 5 mm ATP that surely served to fuel intracellular as well as plasmalemmal Ca2+-ATPases. Another possibility is that CCCP causes direct pharmacological inhibition of Ca2+ channels, as reported by Stapleton et al. (1994) and Park et al. (1996). This is also unlikely because a compound causing direct blockade of Ca2+ channels will do so regardless of the use of Ca2+ or Ba2+ as charge carrier, or regardless of the presence or absence of EGTA in the intracellular solution. This is the case, for instance, for the neuroprotectant lubeluzole, which blocks L- and N- as well as P/Q-type Ca2+ channel currents regardless of the use of Ca2+ or Ba2+ as charge carrier (Hernández-Guijo et al., 1997). This was not the case for CCCP, which caused the quick inhibition ofICa (Fig. 1A) but only a mild inhibition of IBa (Fig. 2A). In addition, the inhibition of ICa was fully prevented by intracellular EGTA.

Rather, we attribute the effects of CCCP on ICato its well known effects on mitochondria. CCCP collapses the proton gradient and the electrical potential, causing mitochondrial depolarization. This has two immediate consequences: blockade of Ca2+ uptake by the mitochondrial uniporter and the release of any stored mitochondrial Ca2+. This will cause an increase of the bulk [Ca2+]c(Fig. 5) that will reach tenths of micromolar at subplasmalemmal sites, after cell depolarization, as we recently demonstrated using mitochondrially targeted aequorin and electroporated bovine chromaffin cells (Montero et al., 2000). We believe that this high local [Ca2+]c is responsible for the inhibition of ICa. Such inhibition is gradual during repeated application of depolarizing pulses at 1 Hz (Fig. 3). This was likely caused by the progressive elevation of [Ca2+]c near the Ca2+ channels, because Ca2+enters the cell through those channels during each pulse, and Ca2+ cannot be buffered by CCCP-poisoned mitochondria. A subpopulation of mitochondria is capable of taking up vast amounts of Ca2+, which reach mitochondrial [Ca2+] near the millimolar. These mitochondria can sense up to 50 μm[Ca2+]c, and hence they must be located close to the plasmalemma, where such large [Ca2+]c gradients are possible (Montero et al., 2000).

A second mechanism relates to the release of mitochondrial Ca2+ as a consequence of the dissipation of the proton gradient. If CCCP is applied when mitochondria is still full of Ca2+, then CCCP will induce a prompt release of mitochondrial Ca2+ that generates the increase in local [Ca2+]c near the internal mouth of the Ca2+ channel (Fig. 5). This increase will promote the Ca2+-induced inhibition of Ca2+. This second mechanism can also explain the differences observed between CCCP and the other agents used to prevent Ca2+ uptake into mitochondria, i.e., slower and partial ICa decay after ruthenium red dialysis or extracellular superfusion with oligomycin plus rotenone. As shown in Figure 5, CCCP favors Ca2+ release from mitochondria and other intracellular store in fura-2-loaded chromaffin cells, whereas oligomycin plus rotenone did not.

That the dialysis of the cells with 14 mm EGTA completely prevented the current inhibition by CCCP (Fig. 1B) strongly supports the hypothesis that the sequestration of Ca2+ by mitochondria plays a major role in maintaining functional Ca2+ channels during repeated stimulation of chromaffin cells. This was corroborated also by three additional experimental findings. First, ruthenium red, which blocks the Ca2+ uniporter thus preventing mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake, also caused the gradual inhibition ofICa during repeated depolarization pulses (Fig.4A). Second, combined oligomycin plus rotenone, which also collapses the mitochondrial potential, also caused gradualICa inhibition (Fig. 4B), which was again prevented by 14 mm intracellular EGTA (Fig.4C). Third, when Ba2+ was used as charge carrier instead of Ca2+, CCCP caused little inhibition of IBa. This might be explained by the fact that Ba2+ is a poor substrate for the Ca2+ transport systems (Schilling et al., 1989; Wagner-Mann et al., 1992). In addition, Ba2+ has also been described as inducing the inactivation of Ca2+ channels, although with an affinity for the inactivation site on the Ca2+channels 100 times slower than that of Ca2+(Ferreira et al., 1997). The partial inhibition ofIBa induced by CCCP could be also attributed to Ba2+-induced release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores or binding sites (von Rüden et al., 1993). It is plausible that this Ca2+ may be taken up by mitochondria in control conditions (Montero et al., 2000). However, treatment of the cells with CCCP will preclude this mitochondrial Ca2+ removal, and this Ca2+ might thus contribute to the partial blockade of Ca2+ channel currents seen when Ba2+ is used as charge carrier.

We believe that the full inhibition of ICa by CCCP, indicating that L- and N- as well as P/Q-type Ca2+ channels were affected, is a most interesting finding (Fig. 6). Modulation by Ca2+ of L-type channels is well illustrated; however, little evidence is available for N and P/Q channels. The Ca2+-dependent inactivation of Ca2+ channels seems to be more sensitive to Ca2+ in the case of L-type Ca2+channels, as compared with non-L-type Ca2+ channels (Plant, 1988; Kasai and Neher, 1992). However, we find here that N and P/Q channels were inhibited faster than L channels after repeated application of depolarizing pulses to CCCP-treated cells (Fig. 6D). This raises the question of whether the classic Ca2+-dependent inactivation of Ca2+ channel currents (Hagiwara and Byerly, 1981) and the Ca2+-dependent inhibition of such currents (this work) are different manifestations of the same underlying mechanism of modulation of the channels by Ca2+ ions.

In any case, the idea that clearly emerges from this study is that as on other cell types (Bassani et al., 1992;Rizzuto et al., 1992; Friel and Tsien, 1994; Drummond and Fay, 1996; Park et al., 1996; Greenwood et al., 1997), mitochondria have an important role in shaping the [Ca2+]c transients generated under our experimental conditions (i.e., brief depolarizing pulses applied at 0.1–1 Hz to dialyzed cells). It might be that under more physiological stimulation conditions of chromaffin cells (i.e., by short-cut repeated depolarizing pulses), mitochondria could sense the high [Ca2+]c that can be reached only underneath the plasma membrane (Montero et al., 2000). Hence, we believe that by limiting the extent and duration of such large local [Ca2+]c transients, mitochondria strategically located near the plasma membrane play the important function of maintaining the L, N, and P/Q Ca2+ channels ready to be recruited under stressful conditions that cause repetitive stimulation of chromaffin cells, by endogenously released acetylcholine in the intact adrenal gland.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by grants from DGICYT (Dirección General de Investigación Científica y Técnica; No. PB99-0004 and No. PB99-0005), CAM (Comunidad Autónoma de Madrid; No. 08.5/0002/98 and No. 08.5/0007/98), Programa de Grupos Estratégicos CAM/UAM, and Fundación Teófilo Hernando, Spain. We thank Ricardo de Pascual for the preparation of cell cultures. J.M.H.G. and A.R.N. are fellows of CAM, Madrid, Spain. We also thank Drs. Javier García-Sancho and Javier Alvarez for their suggestions and criticisms.

Correspondence should be addressed to Luis Gandía, Departamento de Farmacología, Facultad de Medicina, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, C/Arzobispo Morcillo, 4, 28029 Madrid Spain. E-mail:luis.gandia@uam.es.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albillos A, Artalejo AR, López MG, Gandía L, García AG, Carbone E. Calcium channel subtypes in cat chromaffin cells. J Physiol (Lond) 1994;477:197–213. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albillos A, García AG, Olivera BM, Gandía L. Re-evaluation of the P/Q Ca2+ channel components of Ba2+ currents in bovine chromaffin cells superfused with solutions containing low and high Ba2+ concentrations. Pflügers Arch. 1996;432:1030–1038. doi: 10.1007/s004240050231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Babcock DF, Herrington J, Park YB, Hille B. Mitochondrial participation in the intracellular Ca2+ network. J Cell Biol. 1997;136:833–843. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.4.833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bassani RA, Bassani JWM, Bers DM. Mitochondrial and sarcolemmal Ca2+ transport reduce [Ca2+]i during caffeine contractures in rabbit cardiac myocytes. J Physiol (Lond) 1992;453:591–608. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brehm P, Eckert R. Calcium entry leads to inactivation of calcium channel in Paramecium. Science. 1978;202:1203–1206. doi: 10.1126/science.103199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brini M, De Giorgi F, Murgia M, Marsault R, Massimino ML, Cantini M, Rizzuto R, Pozzan T. Subcellular analysis of Ca2+ homeostasis in primary cultures of skeletal muscle myotubes. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:129–143. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.1.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Budd SL, Nicholls DG. A re-evaluation of the role of mitochondria in neuronal Ca2+ homeostasis. J Neurochem. 1996;66:403–411. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.66010403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colegrove SL, Albrecht MA, Friel DD. Dissection of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake and release fluxed in situ after depolarization-evoked [Ca2+](i) elevations in sympathetic neurons. J Gen Physiol. 2000;115:351–370. doi: 10.1085/jgp.115.3.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drummond RM, Fay FS. Mitochondria contribute to Ca2+ removal in smooth muscle cells. Pflügers Arch. 1996;431:473–482. doi: 10.1007/BF02191893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fenwick EM, Marty A, Neher E. Sodium and calcium currents in bovine chromaffin cells. J Physiol (Lond) 1982;331:599–635. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferreira G, Yi J, Rios E, Shirokov R. Ion-dependent inactivation of barium current through L-type calcium channels. J Gen Physiol. 1997;109:449–461. doi: 10.1085/jgp.109.4.449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friel DD, Tsien RW. An FCCP-sensitive Ca2+ store in bullfrog sympathetic neurons and its participation in stimulus-evoked changes in [Ca2+]i. J Neurosci. 1994;14:4007–4024. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-07-04007.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.García AG, Gandía L, López MG, Montiel C. Calcium channels for exocytosis: functional modulation with toxins. In: Botana L, editor. Seafood and freshwater toxins: pharmacology, physiology and detection. Marcel Decker; New York: 2000. pp. 91–124. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giannattasio B, Jones SW, Scarpa A. Calcium currents in the A7r5 smooth muscle-derived cell line. Calcium-dependent and voltage-dependent inactivation. J Gen Physiol. 1991;98:987–1003. doi: 10.1085/jgp.98.5.987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenwood IA, Helliwell RM, Large WA. Modulation of Ca2+-activated Cl− currents in rabbit portal vein smooth muscle by an inhibitor of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake. J Physiol (Lond) 1997;505:53–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.053bc.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hagiwara S, Byerly L. Calcium channel. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1981;4:69–125. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.04.030181.000441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hagiwara S, Nakajima S. Effects of intracellular Ca ion concentration upon the excitability of the muscle fiber membrane of a barnacle. J Gen Physiol. 1966;49:807–818. doi: 10.1085/jgp.49.4.807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamill OP, Marty A, Neher E, Sakmann B, Sigworth FJ. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflügers Arch. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hernández-Guijo JM, Gandía L, de Pascual R, García AG. Differential effects of the neuroprotectant lubeluzole on bovine and mouse chromaffin cell calcium channel subtypes. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;122:275–285. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kasai H, Neher E. Dihydropyridine-sensitive and ω-conotoxin-sensitive calcium channels in mammalian neuroblastoma-glioma cell line. J Physiol (Lond) 1992;448:161–188. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lawrie AM, Rizzuto R, Pozzan T, Simpson WM. A role of calcium influx in the regulation of mitochondrial calcium in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:10753–10759. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.18.10753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Livett BG. Adrenal medullary chromaffin cells in vitro. Physiol Rev. 1984;64:1103–1161. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1984.64.4.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Montero M, Alonso M-T, Carnicero E, Cuchillo-Ibáñez I, Albillos A, García AG, García-Sancho J, Alvarez J. Physiological stimuli trigger fast millimolar [Ca2+] transients in chromaffin cell mitochondria. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:57–61. doi: 10.1038/35000001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moro MA, López MG, Gandía L, Michelena P, García AG. Separation and culture of living adrenaline- and noradrenaline-containing cells from bovine adrenal medullae. Anal Biochem. 1990;185:243–248. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(90)90287-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neely A, Olcese R, Bew X, Birmbaumer L, Stefani E. Ca2+-dependent inactivation of a cloned cardiac Ca2+ channel α1 subunit (α1C) expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Biophys J. 1994;66:1895–1903. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80983-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neher E. Combined fura-2 and patch-clamp measurements in rat peritoneal mast cells. In: Sellin LC, Libelius R, Thesleff S, editors. Neuromuscular junction. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 1989. pp. 65–76. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neher E. Vesicle pools and Ca2+ microdomains: new tools for understanding their roles in neurotransmitter release. Neuron. 1998;20:389–399. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80983-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park YB, Herrington J, Babcock DF, Hille B. Ca2+ clearance mechanisms in isolated rat adrenal chromaffin cells. J Physiol (Lond) 1996;492:329–346. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pivovarova NB, Hongpaisan J, Andrews SB, Friel DD. Depolarization-induced mitochondrial Ca accumulation in sympathetic neurons: spatial and temporal characteristics. J Neurosci. 1999;19:6372–6384. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-15-06372.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Plant TD. Properties and calcium-dependent inactivation of calcium currents in cultured mouse pancreatic β-cells. J Physiol (Lond) 1988;404:731–747. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rizzuto R, Simpson C, Brini M, Pozzan T. Rapid changes of mitochondrial Ca2+ revealed by specifically targeted recombinant aequorin. Nature. 1992;358:325–327. doi: 10.1038/358325a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rizzuto R, Bastianutto C, Brini M, Murgia M, Pozzan T. Mitochondrial Ca2+ homeostasis in intact cells. J Cell Biol. 1994;126:1183–1194. doi: 10.1083/jcb.126.5.1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schilling WP, Rajan L, Strobl-Jager E. Multiple effects of ryanodine on intracellular free Ca2+ in smooth muscle cells from bovine and porcine coronary artery: modulation of sarcoplasmic reticulum function. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:12838–12848. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stapleton SR, Scott RH, Bell BA. Effects of metabolic blockers on Ca2+-dependent currents in cultured sensory neurones from neonatal rats. Br J Pharmacol. 1994;111:57–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb14023.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tillotson D. Inactivation of Ca conductance dependent on entry of Ca ions in molluscan neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:1497–1500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.3.1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.von Gersdorff H, Matthews G. Calcium-dependent inactivation of calcium current in synaptic terminals of retinal bipolar neurons. J Neurosci. 1996;16:115–122. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-01-00115.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.von Rüden L, García AG, López MG. The mechanism of Ba2+-induced exocytosis from single chromaffin cells. FEBS Lett. 1993;336:48–52. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81606-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wagner-Mann C, Hu Q, Strueck M. Characterization of the bradykinin-stimulated calcium influx pathway of cultured vascular endothelial cells. Br J Pharmacol. 1992;105:903–911. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Werth JL, Thayer SA. Mitochondria buffer physiological calcium loads in cultured rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. J Neurosci. 1994;14:346–356. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-01-00348.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.White RJ, Reynolds IJ. Mitochondria accumulate Ca2+ following intense glutamate stimulation of cultured rat forebrain neurons. J Physiol (Lond) 1997;498:31–47. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yue DT, Backy PH, Imredy JP. Calcium-sensitive inactivation in the gating of single-calcium channels. Science. 1990;250:1735–1738. doi: 10.1126/science.2176745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]