Abstract

Although GluR1o and GluR3o are homologous at the amino acid level, GluR3o desensitizes approximately threefold faster than GluR1o. By creating chimeras of GluR1o and GluR3o and point amino acid exchanges in their S2 regions, two residues were identified to be critical for GluR1o desensitization: Y716 and the R/G RNA-edited site, R757. With creation of the double-point mutant (Y716F, R757G)GluR1o, complete exchange of the desensitization rate of GluR1o to that of GluR3o was obtained. In addition, both the potency and affinity of the subtype-selective agonist bromohomoibotenic acid were exchanged by the Y716F mutation. A model is proposed of the AMPA receptor binding site whereby a hydrogen-bonding matrix of water molecules plays an important role in determining both ligand affinity and receptor desensitization properties. Residues Y716 in GluR1 and F728 in GluR3 differentially interact with this matrix to affect the binding affinity of some ligands, providing the possibility of developing subtype-selective compounds.

Keywords: AMPA receptor, desensitization, binding site, GluR1, GluR2, GluR3, GluR4 agonist subtype-selectivity, mutant receptors

l-glutamate, the major excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain, activates three distinct types of ionotropic glutamate receptors (iGluR): NMDA receptors, AMPA receptors (AMPARs), and kainate (KA) receptors (for review, see Hollmann and Heinemann, 1994;Dingledine et al., 1999). These receptor channels consist of a heteromeric complex composed of four or five subunits (Ferrer-Montiel and Montal, 1996; Mano and Teichberg, 1998; Rosenmund et al., 1998). Four different subunits (GluR1–4) can contribute to the formation of AMPARs and are capable of forming functional homomeric and heteromeric channels (Brose et al., 1994). GluR1–4 can exist in two alternate splice versions, termed flip and flop (Sommer et al., 1990), which show differences in their desensitization properties (Mosbacher et al., 1994; Koike et al., 2000) and their sensitivity to blockers of desensitization, such as cyclothiazide (Partin et al., 1994). In addition, in GluR2, GluR3, and GluR4, intronic elements determine a codon switch in the primary transcripts at a position termed the R/G site that immediately precedes the flip/flop region (Lomeli et al., 1994). The R/G site also affects receptor desensitization properties as well as recovery from desensitization.

Native and cloned AMPARs desensitize rapidly and almost completely in response to glutamate application, on a millisecond time scale (Mayer and Westbrook, 1987; Stern-Bach et al., 1998; Dingledine et al., 1999). Excessive activation of iGluRs, for example by blocking their desensitization, may mediate neuronal excitotoxic death (Jensen et al., 1998, 1999). Consequently, iGluRs are thought to play a role in several neurological disorders and neurodegenerative diseases (Bittigau and Ikonomidou, 1997). However, although there is substantial knowledge relating to iGluR desensitization at the cellular level, relatively little is known about the molecular mechanism of desensitization. In contrast, the characterization of the agonist binding domain of iGluRs has been greatly advanced by x-ray crystal structure data of soluble GluR2 binding domain constructs consisting of segments S1 and S2 joined together by a polypeptide linker (Armstrong et al., 1998; Armstrong and Gouaux, 2000). S1 is located N-terminal to transmembrane domain I (TMD I), whereas S2 is situated between TMD III and TMD IV and contains the flip/flop and R/G sites. Agonist binding to AMPARs is thought to involve an interaction of S1 with S2 that yields a closed configuration, which has been suggested to be related to both efficacy and desensitization (Paas, 1998; Armstrong and Gouaux, 2000; Krupp and Westbrook, 2000).

In the present study, AMPAR amino acid residues involved in both ligand binding and channel gating were investigated by creating receptor chimeras and point exchanges between two homologous AMPAR subunits, GluR1o and GluR3o. Because GluR3o has a faster desensitization rate constant than GluR1o, it was possible to investigate the molecular reasons for this difference. In addition, although the homology in the S1 and S2 regions between these subunits is 81 and 92%, respectively, they are not identical. Our recent discovery (Coquelle et al., 2000) of an AMPAR subtype-selective agonist, (S)-4-bromohomoibotenic acid [(S)-BrHIBO], made it possible to investigate differences in the binding sites of GluR1o versus GluR3o responsible for determining this selectivity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mutagenesis. For preparation of high-expression cRNA transcripts, GluR1o and GluR3o (provided by Dr. S. F. Heinemann, The Salk Institute, La Jolla, CA) were each inserted into the pGEM HE vector (Liman et al., 1992) at the (5′)-BamHI and (3′)-XbaI sites of the multiple cloning site. All of the 5′ and 3′ untranslated sequence had been removed from these clones. GluR4co in pBluescript SK(−) vector (kindly supplied by Dr. A. Buonanno, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) was digested with XhoI, treated with Klenow enzyme to produce blunt ends, and subsequently digested with BamHI. The GluR4co insert was then subcloned into the (5′)-BamHI and (3′)-XbaI (blunt-ended with Klenow enzyme) sites of pGEM HE vector, leaving a 58 bp 5′- and ≈430 bp 3′-untranslated sequence. Mutagenesis was performed with the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) using the GluR1o, GluR3o, or GluR4co pGEM HE cDNA as a template. Mutagenic oligonucleotides were obtained from DNA Technology A/S (Aarhus, Denmark) and also contained silent restriction sites for screening of mutant colonies. Mutated regions were cassetted back into the corresponding template cDNA and then sequenced-verified using the BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit and an Applied Biosystems Prism 310 Sequencer (Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, CA). cDNAs were grown in XL1 Blues bacteria (Stratagene) and prepared using column purification (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA). cRNA was synthesized from these cDNAs using the mMessage mMachine T7 mRNA-capping transcription kit (Ambion, Austin, TX).

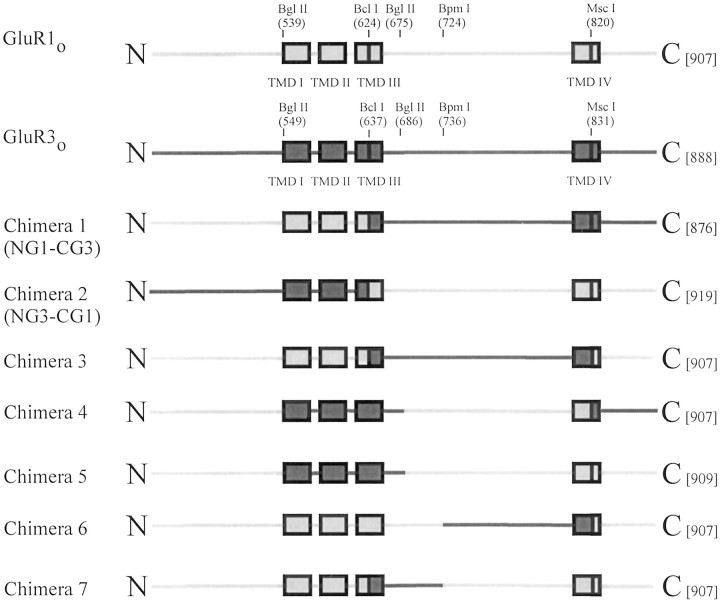

Creation of chimeric receptors. Chimeric GluR1o–GluR3o receptors were created using naturally occurring restriction enzyme sites in the wild-type receptor cDNAs (Fig. 1). Construction of chimeras 1 and 2 has been described previously (Banke et al., 1997); these chimeras were formerly named NG1-CG3 and NG3-CG1, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Chimeric constructs of GluR1o and GluR3o. The GluR1o sequence is represented bylight gray areas, and the GluR3o sequence is represented by black areas.Numbering above the wild-type sequences refers to amino acid position number, starting from the initiation methionine. The corresponding restriction enzyme sites in the cDNA used to create these constructs are also indicated. The amino acid length of each protein is given in square brackets. Note that chimeras 1 and 2 were previously named NG1-CG3 and NG3-CG1, respectively (Banke et al., 1997), but have been renamed here for simplicity. TMD I through TMD IV are indicated as boxes; N, N terminus; C, C terminus. This figure is not drawn to scale.

Recombinant baculovirus construction. The baculovirus-Sf9 cell system was used to express recombinant AMPAR complexes used for radioligand binding assays. All manipulations of virus and insect cells, including maintenance of cell culture, transfection, plaque purification, amplification, and expression of receptor, were according to standard protocols in the Guide to Baculovirus Expression Vector Systems and Insect Cell Culture Techniques (Life Technologies, Paisley, UK) and Baculovirus Expression Vector System: Procedures and Methods Manual, Second Edition (PharMingen, San Diego, CA). The creation and expression of recombinant GluR1o and GluR3o baculoviruses and Sf9 cell culture have been described previously (Nielsen et al., 1998). Baculoviruses of the mutants (Y716F, R757G)GluR1o, (Y716F)GluR1o, (F728Y, G769R)GluR3o, and (F728Y)GluR3o were made in the same manner by subcloning these mutants from the pGEM HE vector into a baculovirus transfer vector and using the PharMingen BaculoGold transfection kit.

Radioligand binding. The affinities of compounds at wild-type and mutant receptors were determined from competition experiments with (R,S)-[5-methyl-3H]AMPA (40.87 Ci/mmol; NEN, Boston, MA) as described previously (Nielsen et al., 1998; Coquelle et al., 2000). Competition data were fit to a logistic equation (Eq. 1) to determine the Hill coefficient (nH) or to Equation 2 for calculation of the drug affinity (Ki):

| Equation 1 |

| Equation 2 |

where Kd equals radioligand dissociation constant, Ki equals inhibitor dissociation constant, Ltequals total radioligand concentration,TBmax equals total radioligand bound at zero competitor concentration, nHequals Hill coefficient, NSB equals nonspecific binding, and [I] equals total competitive inhibitor concentration.

Oocyte preparation. Mature female Xenopus laevis(African Reptile Park, Tokai, South Africa) were anesthetized using 0.1% ethyl 3-aminobenzoate, and ovaries were surgically removed. The ovarian tissue was dissected and treated with 2 mg/ml collagenase in Ca2+-free Barth's medium for 2 hr at room temperature and subsequently defolliculated using fine forceps. On the second day, oocytes were injected with 50–100 nl of ∼1 μg/μl cRNA and incubated in Barth's medium (in mm): 88 NaCl, 1 KCl, 0.33 Ca(NO3)2, 0.41 CaCl2, 0.82 MgSO4, 2.4 NaHCO3, and 10 HEPES, pH 7.4, with gentamicin (0.10 mg/ml) at 17°C. Oocytes were used for recordings from 6 to 10 d after injection.

Two-electrode voltage clamp. The oocytes were voltage-clamped by using a two-electrode voltage clamp (Dagan Corporation, Minneapolis, MN) having a virtual ground, with both microelectrodes filled with 3 m KCl. Recordings were made while the oocytes were continuously superfused with frog Ringer's solution (in mm): 115 NaCl, 2 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, and 5 HEPES, pH 7.0. Drugs were dissolved in Ringer's solution and were added by bath application. All recordings were made at room temperature at a holding potential (Vh) of −80 mV. In our hands, oocyte calcium-activated chloride channels have never been observed to interfere with the expressed AMPAR currents.

Agonist concentration-response curves were constructed by measuring the maximal current induced by increasing concentrations of agonist. Data from individual oocytes were fit to a logistic equation:I = Imax/[1 + (EC50/[agonist])nh], where I is the response observed at a given agonist concentration. The parameters Imax(maximal current observed at infinite agonist concentration),nH (Hill coefficient), and the EC50 were determined by an iterative least squares fitting routine.

Patch-clamp recordings. Injected oocytes were prescreened with a two-electrode voltage clamp; those having a response >200 nA (Vh = −80 mV) to 300 μm KA were selected for further investigation. The vitelline membrane was removed by placing the oocyte in a 35 mm dish containing a hyperosmotic medium (in mm): 200 K+-aspartate, 20 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 5 EGTA-KOH, and 10 HEPES-KOH, pH 7.4. After 10–15 min in this solution, the vitelline membrane was removed with a pair of fine forceps. Outside-out patches from oocytes were prepared with thin-walled glass capillaries (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) filled with (in mm): 100 KCl, 10 EGTA, and 10 HEPES, pH 7.0. Pipettes had a resistance of 3–5 MΩ. The external solution was frog Ringer's. Fast application of agonists to outside-out membrane patches was made using a double-barreled theta-glass tube (outer diameter, 2.0 mm; wall thickness, 0.3 mm; septum thickness, 0.12 mm; Hilgenberg, Malsfeld, Germany). Frog Ringer's solution flowed continuously through one barrel, while the other barrel contained either 10 mml-glutamate or 1 mm (R,S)-BrHIBO. The theta-glass tube was stepped using a piezo-electric element (Burleigh Instruments, Fishers, NY). By measuring the change in junction current between two different buffer solutions, the 10–90% rise time was determined to be <100 μsec. Rate constants (τ values) were determined by fitting the average macroscopic responses to the following rate equation: At =Aoe−t/τ+ Iss, whereAt is the current amplitude at time (t), Ao is the maximum current amplitude, e is the base of the natural logarithm,Iss is the steady-state current, and τ is the rate constant. Currents were recorded with an RK-400 amplifier (Bio-Logic Science Instruments, Claix, France), filtered at 2 kHz, and digitized with a sampling rate of 20 kHz; data were stored on-line onto a personal computer hard disk drive.

Sequence and data analyses software. Nucleotide and protein alignments and sequence comparisons were performed using PCgene version 6.60 (IntelliGenetics Inc., Mountain View, CA). The GluR1o, GluR3o, and GluR4co proteins are numbered here beginning from the initiation methionine. The numbering for GluR2 is as given inArmstrong et al. (1998). Unless otherwise stated, one-way ANOVA (followed by the Bonferroni t test, if required) or Student's t test was used for comparison of the parameters of the receptors using SigmaStat for Windows version 2.0 (SPSS Science, Chicago, IL) or GraphPad (San Diego, CA) Instat version 2.01. Values were considered statistically significantly different if pvalues were <0.05. Electrophysiological data were analyzed as described above using NPM (written by Dr. Steve Traynelis, Emory University, Atlanta, GA), VClamp version 6.0 (Cambridge Electronic Design, Cambridge, UK), and Origin version 5.0 (Microcal Software, Northampton, MA); binding data were analyzed using Grafit version 3.00 (Erithacus Software Ltd., Horley, UK).

Molecular modeling. The amino acid sequences of GluR1–4 (flop versions) were aligned with the GluR2-S1S2I construct described by Armstrong et al. (1998) using Macaw software version 2.0.5 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) (Schuler et al., 1991; Lawrence et al., 1993). Models of the binding sites of GluR1–4 were built from GluR2-S1S2J complexed with various ligands (Armstrong et al., 2000) by interchanging homologous amino acids, in particular Y702 (GluR2) for phenylalanine in GluR3 and GluR4. This was justified on the basis of previous models of GluR1–4 homology built from GluR2-S1S2I using Swiss-Model via the Expert Protein Analysis System (ExPASy) Molecular Biology Server (Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics, Geneva, Switzerland; http://www.expasy.ch), which showed very little deviation of backbone and side chains around the binding site.

Based on the crystal structures of GluR2-S1S2J complexed withl-glutamate and (S)-AMPA (Armstrong et al., 2000), models were constructed of these ligands as well as for (S)-BrHIBO bound to GluR1 and GluR3. A reasonable binding conformation for the tri-ionized form of (S)-BrHIBO was found by a Monte Carlo search of the conformational space according to the MMFF94 forcefield in MacroModel version 6.5 (Mohamadi et al., 1990) including the GB/SA solvation model. The chosen local minimum energy conformation lay 0.05 kcal/mol above the global minimum. The binding positions of (S)-BrHIBO were estimated by overlaying the formally charged atoms of (S)-BrHIBO on (S)-AMPA. The two α-amino acid portions were matched directly, but the isoxazole ring of (S)-BrHIBO was inverted around the carboxylate bioisostere, matching the ring N with O1 and vice versa, as suggested previously (Christensen et al., 1992; Greenwood et al., 1998).

Calculations were performed to confirm the preferred sites for water molecules within the ligand-binding cavities of the agonist-bound state of the GluR1 and GluR3 homology models using the program GRID, version 18 (Goodford, 1985). The proton positions and hydrogen-bonding networks were established by a combination of inspection, energy minimization, and Monte Carlo methods to resolve ambiguities as follows: all waters and side-chain hydroxyls within 8.5 Å of the ligand were rotated randomly to give thousands of initial structures. The positions of the protons were then optimized, including all atoms within a 12.5 Å radius, again using the MMFF94 forcefield (Mohamadi et al., 1990). (For additional details concerning our homology models, interested readers may contact Prof. Tommy Liljefors at the following e-mail address: tl@dfh.dk.)

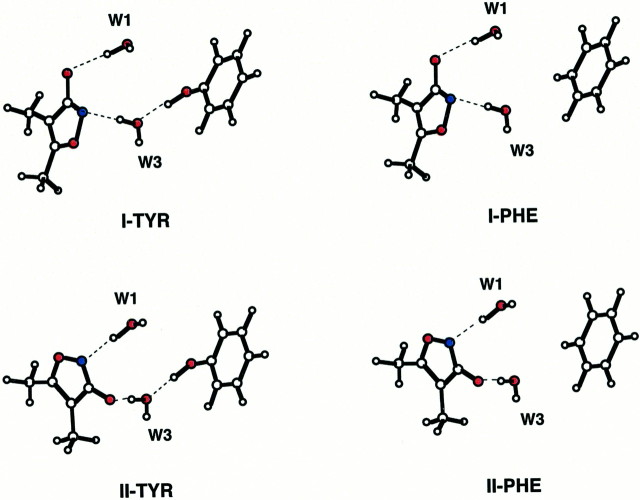

Finally, simplified models of both HIBO-type and AMPA-type binding relative to the nonconserved Y716(GluR1)/F728(GluR3) residue were constructed, consisting of a benzene or phenol ring representing this residue (TYR or PHE), a deprotonated 3-hydroxy-4,5-dimethylisoxazol anion representing either AMPA (I) or 4-methylhomoibotenic acid (MeHIBO), and two interposing water molecules corresponding to W1 and W3. Fixing as few internal geometric coordinates as possible to retain approximate relative orientations, the four models (I-TYR, I-PHE, II-TYR, and II-PHE) were submitted to quantum mechanical energy minimizations usingab initio B3LYP density functional theory with the 6–31+G(d) basis set in Gaussian 98 version A.7 (Gaussian Inc., Pittsburgh, PA).

Materials. Restriction enzymes and other molecular biological enzymes were obtained from New England BioLabs (Beverly, MA). (R,S)-AMPA and (R,S)-BrHIBO were synthesized in the Department of Medicinal Chemistry, The Royal Danish School of Pharmacy (Krogsgaard-Larsen et al., 1980; Hansen et al., 1989). Sf900-II culture medium, gentamicin, antibiotics, and plaque assay reagents were obtained from Life Technologies. KA andl-quisqualic acid were purchased from Tocris Cookson Ltd. (Bristol, UK). Collagenase and additional chemicals and reagents were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) or similar local suppliers.

RESULTS

Desensitization of wild-type and chimeric AMPARs

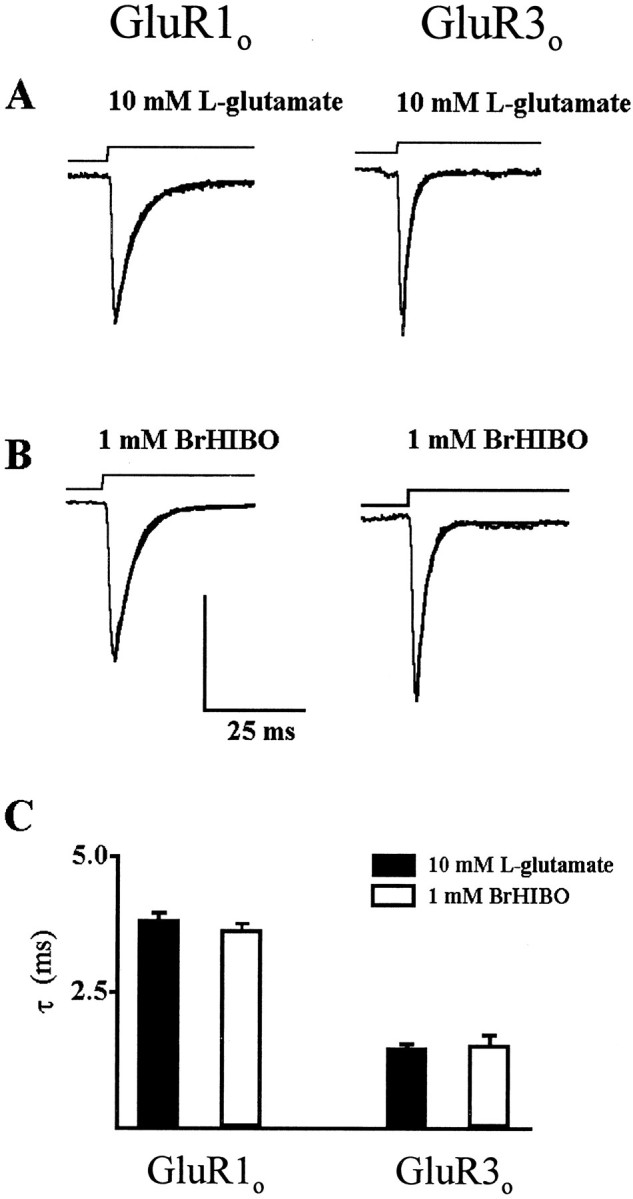

The gating properties of the wild-type, homomeric AMPAR subunits were characterized in X. laevis oocytes injected with wild-type GluR1o or GluR3ocRNA. Because the observed desensitization rate constant (τ) can be dependent on agonist concentration, a high concentration ofl-glutamate was used such that τ was independent of agonist concentration (Koike et al., 2000). Responses of GluR1o and GluR3o to fast application (<100 μsec) of either 10 mml-glutamate (Fig.2A) or 1 mm BrHIBO (Fig. 2B) were examined. GluR1o exhibited a slower desensitization rate compared with GluR3o for both agonists, whereas no difference was seen between these agonists. However, the 10–90% rise time for 1 mm(R,S)-BrHIBO at GluR1o (826 ± 24 μsec; n = 5) was statistically significantly different from that at GluR3o (590 ± 82 μsec; n = 5), and (R,S)-BrHIBO showed a significantly slower 10–90% rise time than that observed with 10 mml-glutamate (343 ± 39 μsec for the 10 fastest patches of GluR1o). This difference in rise time could be because 1 mm BrHIBO is not a saturating concentration of agonist, whereas 10 mml-glutamate represents ∼20-fold EC50 (Dingledine et al., 1999).

Fig. 2.

l-glutamate and (R,S)-BrHIBO desensitization at GluR1o and GluR3o. A, Comparison of representative currents evoked by 10 mml-glutamate on outside-out patches expressing GluR1o (left, scale bar = 40 pA) or GluR3o (right, scale bar = 60 pA), respectively. l-glutamate was applied by fast application on outside-out patches as shown above the traces (Vh = −60 mV). Each trace was fitted to a monoexponential equation (line over traces), and τ was determined; τ (GluR1o), 4.2 msec; τ (GluR3o), 1.5 msec. B, Current evoked by 1 mm (R,S)-BrHIBO on outside-out patches expressing GluR1o (left, scale bar = 250 pA) or GluR3o (right, scale bar = 50 pA); τ (GluR1o), 4.0 msec; τ (GluR3o), 1.8 msec. C, Mean τ ± SEM for GluR1o (two left bars) and GluR3o (two right bars). Filled bars, 10 mml-glutamate (left, n = 13; right,n = 16); open bars, 1 mm(R,S)-BrHIBO (left, right,n = 5).

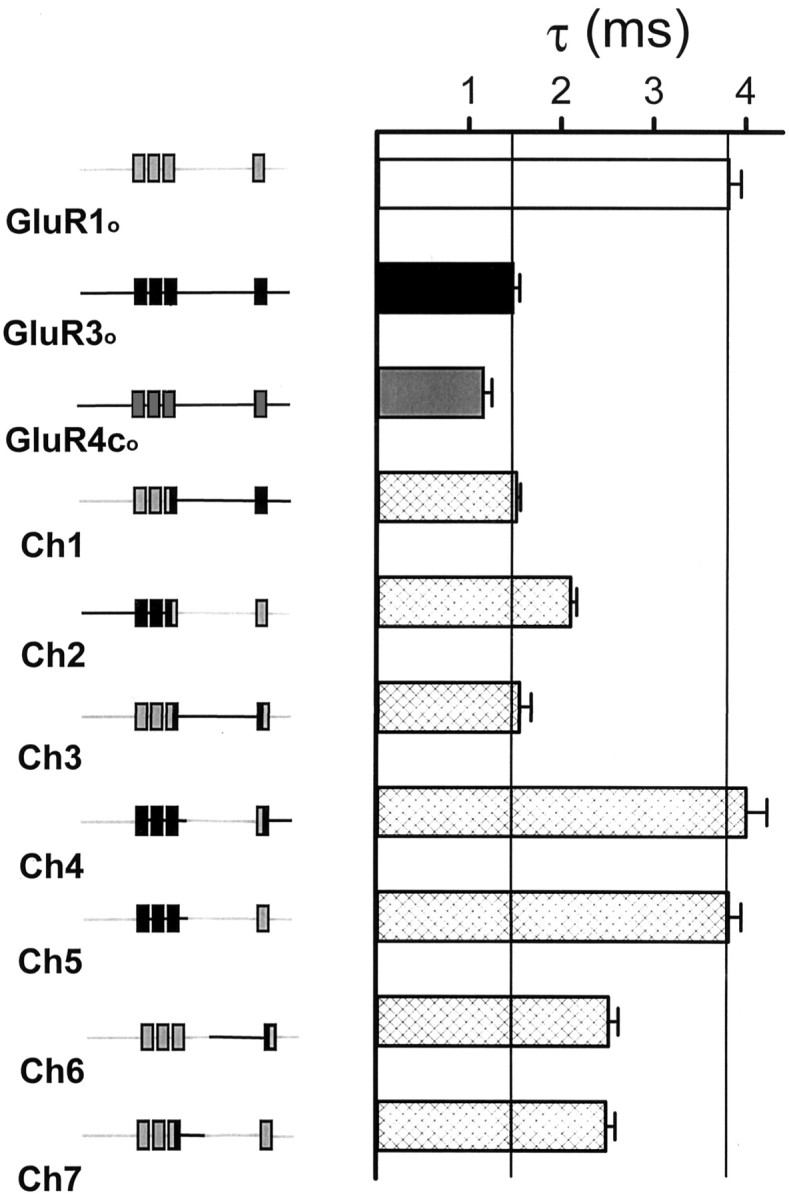

To localize the region or regions of GluR1o and GluR3o responsible for determining τ, chimeric (Ch) GluR1o-GluR3oreceptors were created, and their desensitization properties were measured (Figs. 1, 3). All of the tested receptors were functionally expressed in oocytes and showed almost complete desensitization to 10 mml-glutamate (Table 1). Chimeras 6 and 7 had τ values that were not statistically significantly different from one another but that were, however, intermediate between the values for GluR1o and GluR3o. This suggested that there was an amino acid residue or residues in both the N- and C-terminal halves of the S2 region that was responsible for determining τ.

Fig. 3.

Desensitization at chimeric AMPARs. Comparison of 10 mml-glutamate-evoked currents (mean ± SEM) from, starting at top left, GluR1o, GluR3o, GluR4co, and chimeric receptors (Ch) 1–7 expressed in X. laevis oocytes. The chimeric constructs are shown on the left, as described in Figure1. l-glutamate was applied by fast application on outside-out patches (Vh = −60 mV). Data were fit to a monoexponential equation (see Materials and Methods), and τ was determined.

Table 1.

Kinetic properties of wild-type and mutant AMPARs

| Receptor | τ (msec) | τrec (msec) | τdeact(msec) | Ipeak (pA) | Iss (% Ipeak) | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chimera 1 | 1.53 ± 0.031-165 | 30 ± 20 | 7 ± 1 | 5 | ||

| Chimera 2 | 2.12 ± 0.051-165 | 78 ± 37 | 6 ± 2 | 5 | ||

| Chimera 3 | 1.57 ± 0.111-165 | 107 ± 17 | 5 ± 2 | 7 | ||

| Chimera 4 | 4.03 ± 0.21### | 141 ± 50 | 9 ± 2 | 6 | ||

| Chimera 5 | 3.82 ± 0.15### | 109 ± 36 | 7 ± 2 | 5 | ||

| Chimera 6 | 2.54 ± 0.09††† | 59 ± 18 | 8 ± 2 | 10 | ||

| Chimera 7 | 2.51 ± 0.16††† | 49 ± 10 | 5 ± 1 | 6 | ||

| GluR1o | 3.84 ± 0.12### | 155 ± 16 | 0.99 ± 0.11 | 60 ± 13 | 8 ± 1 | 13,10,10 |

| E665D | 3.63 ± 0.22### | 42 ± 10 | 9 ± 2 | 6 | ||

| A666S | 3.58 ± 0.30### | 68 ± 36 | 7 ± 1 | 5 | ||

| F681Y | 3.71 ± 0.32### | 30 ± 9 | 6 ± 1 | 5 | ||

| T686S | 3.57 ± 0.12### | 40 ± 11 | 7 ± 2 | 6 | ||

| V697T | 3.57 ± 0.15### | 140 ± 23 | 6 ± 1 | 9 | ||

| R698K | 3.86 ± 0.15### | 82 ± 17 | 5 ± 1 | 5 | ||

| E701A | 3.76 ± 0.35### | 19 ± 8 | 9 ± 1 | 7 | ||

| E702D | 3.83 ± 0.30### | 102 ± 25 | 6 ± 2 | 7 | ||

| M704V | 3.83 ± 0.46### | 94 ± 83 | 5 ± 2 | 5 | ||

| I705A | 3.87 ± 0.44### | 181 ± 27 | 9 ± 1 | 7 | ||

| Y714F | 3.04 ± 0.21###,1-160 | 49 ± 19 | 6 ± 2 | 7 | ||

| Y716F | 2.45 ± 0.351-165,## | 117 ± 10 | 0.94 ± 0.11 | 14 ± 2 | 9 ± 1 | 5,5,7 |

| I748V | 3.92 ± 0.13### | 54 ± 13 | 9 ± 1 | 6 | ||

| R757G | 2.55 ± 0.10††† | 52 ± 11* | 1.13 ± 0.06 | 119 ± 25 | 5 ± 1 | 19,5,4 |

| P759A | 3.75 ± 0.30### | 86 ± 15 | 7 ± 1 | 14 | ||

| Y714F + Y716F | 2.89 ± 0.17††† | 149 ± 24 | 1.02 ± 0.08 | 112 ± 25 | 9 ± 2 | 14,5,9 |

| Y714F + R757G | 2.49 ± 0.12††† | 60 ± 6* | 1.02 ± 0.20 | 128 ± 60 | 8 ± 2 | 10,5,4 |

| Y716F + R757G | 1.75 ± 0.071-165 | 56 ± 19* | 1.12 ± 0.12 | 54 ± 14 | 7 ± 1 | 7,7,4 |

| Y714F + Y716F + R757G | 1.67 ± 0.051-165 | 90 ± 9* | 1.02 ± 0.10 | 102 ± 30 | 9 ± 1 | 21,8,9 |

| GluR3o | 1.49 ± 0.061-165 | 142 ± 25 | 1.05 ± 0.09 | 28 ± 5 | 8 ± 2 | 16,5,6 |

| F728Y | 1.19 ± 0.041-165,‡ | 107 ± 29 | 8 ± 2 | 5 | ||

| F728Y + G769R | 1.84 ± 0.101-165,‡,§§ | 138 ± 29 | 6 ± 1 | 10 | ||

| GluR4co | 1.17 ± 0.081-165 | 120 ± 34 | 5 ± 1 | 9 | ||

| F724Y | 0.95 ± 0.031-165,1-159 | 61 ± 33 | 6 ± 1 | 6 | ||

| G765R | 1.77 ± 0.261-165,1-153, | 33 ± 17 | 7 ± 2 | 6 | ||

| F724Y + G765R | 1.64 ± 0.061-165, | 78 ± 19 | 5 ± 2 | 4 |

All receptors were expressed in Xenopus laevisoocytes, and currents were recorded in outside-out patch-clamp configuration after 10 mm l-glutamate stimulation.*,#,†,§,‡p < 0.05;

F1-160: ,##,§§,p < 0.01;

F1-165: ,###,†††,p < 0.001.

versus GluR1o,

F1-159: versus GluR3o,

versus GluR1o and GluR3o,

F1-153: versus GluR4co,

F1-226: versus (F724Y)GluR4co.

n = number of eggs recorded for each parameter (τ, τrec, τdeact).

Desensitization of AMPAR point mutants

Alignment of the S2 regions of GluR1o and GluR3o (Fig.4A) reveals 15 amino acid differences. Therefore, all these residues in GluR1o were individually changed to the corresponding GluR3o residue, and τ was measured (Fig. 4B, Table 1). All mutants were functional when expressed in oocytes. For three mutants (Y714F, Y716F, and R757G), a decreased τ was observed compared with GluR1o but full conversion to the rapid GluR3o desensitization rate was not obtained. Residue R757 of GluR1o corresponds to the R/G editing site and is known to affect desensitization, as well as the recovery from desensitization, after brief application of agonist to AMPARs (Lomeli et al., 1994). Because R757 is located within the C-terminal half of the S2 region (Ch6) and Y714 and Y716 are contained within the N-terminal half (Ch7), this explains why each chimera only showed a partial effect on τ. It was decided to construct multiple-point mutations of these residues to obtain a full conversion of GluR1o τ to that of GluR3o.

Fig. 4.

Desensitization at GluR1o S2 region point mutants. A, An alignment of GluR1o and GluR3o amino acid sequences in the region between TMD III and TMD IV (S2 region). N, N terminus; C, terminus; TMDs are represented by boxes. This section of the figure is not drawn to scale. B, A histogram of the mean desensitization rate constant (τ) for GluR1o point mutants, with amino acids numbered as in A. The 10–90% rise time for the double mutants (pooled) was 275 ± 21 μsec compared with 343 ± 39 μsec for GluR1o (10 fastest patches), which was not statistically significantly different. Significant differences versus GluR1o are indicated as follows: ##p < 0.001,#p < 0.01.

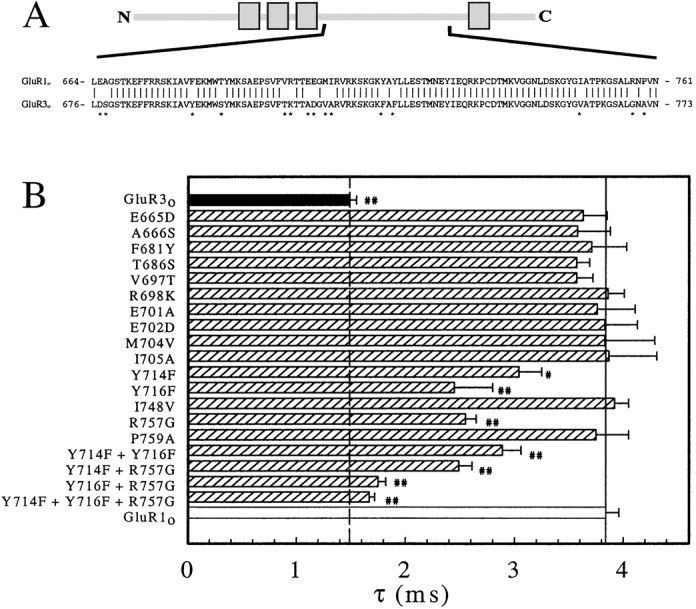

Desensitization, recovery, and deactivation of AMPAR mutants

For the double-point mutant (Y714F, Y716F)GluR1o, τ was statistically significantly different from that for GluR1o and for GluR3o (Fig. 4B, Table 1). The double-point mutant (Y714F, R757G)GluR1o had a τ value that was intermediate between GluR1oand GluR3o and was statistically significantly different from the single-point mutant (Y714F)GluR1o but not different from (R757G)GluR1o, displaying a lack of additivity of effect on τ for these two amino acid residues. Yet, creation of the double-point mutant (Y716F, R757G)GluR1ocompletely converted the desensitization rate constant to a value that was not different from GluR3o. The effects of the double mutations in this case are synergistic, because each of the single-point mutations only partially changed the τ value toward that of GluR3o. The triple-point mutant (Y714F, Y716F, R757G)GluR1o was also evaluated and found not to be statistically different from GluR3o or from (Y716F, R757G)GluR1o, indicating that the effects of Y714F and Y716F exchange are not additive. Therefore, the two key amino acid residues that seem to be responsible for controlling τ in GluR1o are R757 and Y716, although Y714 may have some small effect as well. It was of interest to see whether the complementary changes in GluR3o could result in a slower desensitization rate, as seen for GluR1o. However, the mutants (F728Y)GluR3o and (F728Y, G769R)GluR3o desensitized at rates that were not statistically significantly different from wild-type GluR3o (Table 1). Similar results were obtained with the homologous mutations in GluR4co, which also contains a phenylalanine at this position.

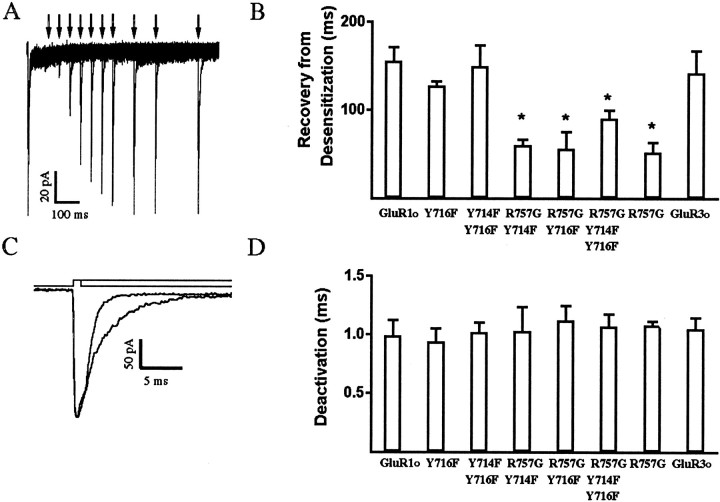

To test whether these point mutations have any effect on the rate of recovery from desensitization, τrec was measured for wild-type GluR1o and GluR3o as well as for several GluR1o mutants (Fig.5, Table 1). Four mutants [(Y714F, Y716F, R757G)GluR1o, (Y714F, R757G)GluR1o, (Y716F, R757G)GluR1o, and (R757G)GluR1o] exhibited a faster recovery from desensitization than did wild type, whereas (Y714F, Y716F)GluR1o and (Y716F)GluR1o were indistinguishable from GluR1o. The data suggest that this τrec effect occurs because of the R/G site (Lomeli et al., 1994) and that the values are in the same range as reported previously for GluR1o (147 msec) (Partin et al., 1996). This implies that Y714 or Y716 are not involved in recovery from desensitization. Interestingly, GluR3o had a τrec that was not different from GluR1o, suggesting that residues in GluR3o other than the R/G site may be involved in controlling τrec. These mutants and wild-type receptors were also evaluated with respect to their deactivation rate (τdeact) after a brief (1 msec) application of 10 mml-glutamate (Fig. 5, Table 1). The τdeact value obtained here for GluR1o is similar to that reported previously (1.1 ± 0.2 msec, Mosbacher et al., 1994; 0.80 ± 0.04 msec, Partin et al., 1996), and none of these mutants differed significantly from wild-type.

Fig. 5.

Deactivation and recovery from desensitization.A, Recovery from desensitization in an outside-out patch expressing wild-type GluR1o receptors.l-glutamate (10 mm) was applied for 1 msec at the following time intervals (in msec): 0, 50, 100, 150, 200, 250, 300, 350, 400, 500, 600, and 800. τrec was 152 msec for this experiment. B, Histogram showing recovery from desensitization for GluR1o and the multiple-point mutants.C, Deactivation and desensitization in an outside-out patch expressing GluR1o. Deactivation and desensitization were obtained by application of 10 mml-glutamate for 1 and 100 msec, respectively, as shown above the traces. Traces were fitted to a monoexponential equation with the following results: τdeact, 0.98 msec; τ, 3.12 msec. D, Histogram showing deactivation rate constants for GluR1o, GluR3o , and GluR1o mutants. *p < 0.05, significantly different from GluR1o.

AMPAR pharmacology

These Y/F and R/G exchanges were then evaluated with regard to effects on agonist potency (EC50) and affinity (Ki). For the latter experiments, the mutants (Y716F, R757G)GluR1o, (Y716F)GluR1o, (F728Y, G769R)GluR3o, and (F728Y)GluR3o were engineered into recombinant baculoviruses and expressed by infection in Sf9 cells. Receptor expression was verified by SDS-PAGE and Western immunoblotting as described previously (Nielsen et al., 1998), and all mutants had the same Mr as the respective wild-type receptor (data not shown).

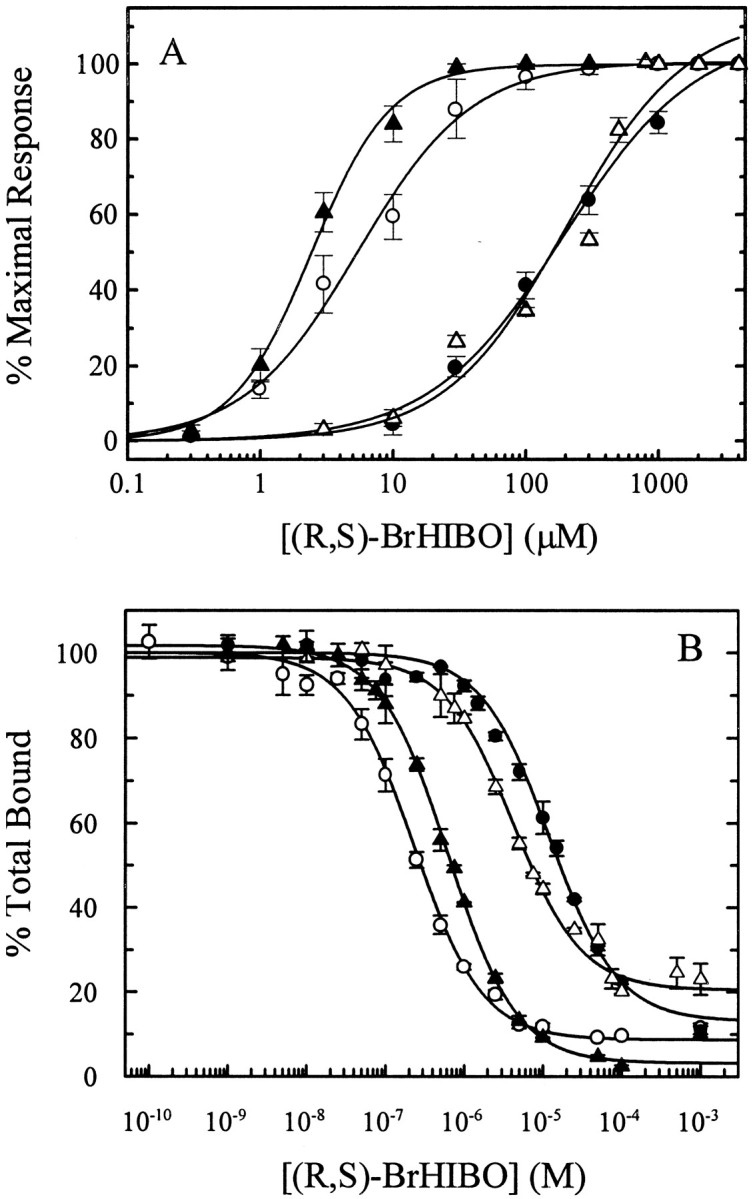

Whereas agonists such as AMPA, KA, and l-glutamate have little or no selectivity between GluR1o and GluR3o (Banke et al., 1997), (R,S)-BrHIBO exhibits an ∼28-fold selectivity for GluR1o (EC50 = 7.2 ± 2.8 μm;n = 5) over GluR3o (EC50 = 198 ± 31 μm; n = 5) (Fig.6A, Table2). Interestingly, at the mutants (Y716F, R757G)GluR1o, (Y714F,Y716F, R757G)GluR1o, and (Y716F)GluR1o, (R,S)-BrHIBO had a potency that was not statistically significantly different from that at GluR3o. Similarly, at the mutants (F728Y, G769R)GluR3o and (F728Y)GluR3o, (R,S)-BrHIBO had a potency that was not different from GluR1o. These results imply that the R/G site is not involved in this change in potency. Hence, the agonist potency for (R,S)-BrHIBO at GluR1o and GluR3o was interchanged by the Y716/F728 point exchanges. In comparison, the potency of (R,S)-BrHIBO at (Y714F, R757G)GluR1o was unchanged from wild-type GluR1o (Table 2), also indicating that neither residue Y714 nor residue R757 are important for this switch in agonist potency.

Fig. 6.

Pharmacology of mutant and wild-type AMPARs. Potency (EC50) and affinity (Ki) of (R,S)-BrHIBO at wild-type and mutant AMPARs are shown. A, Receptors were expressed in X. laevis oocytes, and steady-state currents were measured after application of increasing concentrations of (R,S)-BrHIBO. EC50 was determined by fitting data to a logistic equation as described in Materials and Methods. Curves are mean ± SEM from 5 to 16 oocytes.B, Receptors were expressed in Sf9 cell membranes and drug affinity was measured by (R,S)-[3H]AMPA competition binding assays. Ki was determined by nonlinear, iterative fitting of the data as described in Materials and Methods. Shown are the mean ± SD of triplicate determinations from single experiments (replicated 3–6 times). ○, GluR1o(EC50 = 7.2 ± 2.8 μm;n = 5; Ki = 183 nm); ●, GluR3o (EC50 = 198 ± 31 μm; n = 5;Ki = 9.53 μm); ▵, (Y716F)GluR1o (EC50 = 200 ± 27 μm; n = 16;Ki = 3.69 μm); ▴, (F728Y)GluR3o (EC50 = 2.6 ± 0.4 μm; n = 5;Ki = 423 nm).

Table 2.

Agonist potencies and affinities at wild-type and mutant AMPARs

| Receptor/drug | l-glutamate2-a | Kainate2-a | l-quisqualate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ki(nm) | nH | Ki(nm) | nH | Ki(nm) | nH | |

| GluR3o | 249 ± 72-b | 1.10 ± 0.03 | 1,980 ± 170 | 0.94 ± 0.04 | 21.9 ± 2.52-c | 1.01 ± 0.05 |

| (F728Y, G769R)GluR3o | 168 ± 7 | 1.11 ± 0.07 | 23,300 ± 9902-c,2-d,2-f | 0.90 ± 0.03 | 8.1 ± 1.72-d | 1.00 ± 0.07 |

| (F728Y)GluR3o | 159 ± 7 | 1.01 ± 0.02 | 14,700 ± 1,8002-c,2-d | 0.93 ± 0.03 | ||

| GluR1o | 169 ± 13 | 0.93 ± 0.05 | 478 ± 38 | 0.85 ± 0.01 | 4.7 ± 0.8 | 1.07 ± 0.06 |

| (Y716F, R757G)GluR1o | 149 ± 12 | 1.20 ± 0.22 | 25 ± 52-d–2-f | 1.26 ± 0.15 | 14.7 ± 2.82-c | 1.00 ± 0.07 |

| (Y716F)GluR1o | 34.4 ± 4.52-e,2-f | 0.97 ± 0.02 | ||||

| (Y714F, R757G)GluR1o | ||||||

| (Y714F, Y716F, R757G)GluR1o | ||||||

| Table 2. Continued | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (R,S)-AMPA2-a | (R,S)-BrHIBO | (R,S)-BrHIBO | |||

| Ki(nm) | nH | Ki(nm) | nH | EC50(μM) | nH |

| 20.6 ± 1.1 | 0.99 ± 0.04 | 12,000 ± 2,380 | 0.92 ± 0.03 | 198 ± 31 | 0.89 ± 0.05 |

| 10.0 ± 1.8 | 1.02 ± 0.01 | 427 ± 272-d | 0.93 ± 0.01 | 23 ± 62-d | 1.18 ± 0.05 |

| 7.6 ± 0.7 | 1.04 ± 0.02 | 364 ± 252-d | 0.97 ± 0.04 | 2.6 ± 0.42-d | 1.53 ± 12 |

| 21.9 ± 1.8 | 0.96 ± 0.05 | 173 ± 372-d | 0.85 ± 0.10 | 7.2 ± 2.82-d | 1.10 ± 0.09 |

| 66 ± 62-c–2-f | 0.99 ± 0.12 | 4,050 ± 4102-c,2-d | 1.00 ± 0.15 | 184 ± 632-c,2-e | 0.76 ± 0.08 |

| 87 ± 82-c–2-f | 0.98 ± 0.05 | 3,400 ± 1902-c,2-d | 1.04 ± 0.05 | 200 ± 272-c,2-e,2-f | 0.95 ± 0.05 |

| 8.6 ± 4.02-d | 0.99 ± 0.21 | ||||

| 141 ± 232-c | 1.01 ± 0.15 | ||||

Ki values at GluR1o and GluR3o are taken from Nielsen et al. (1998).

GluR3ol-glutamate Ki is statistically significantly different from the others. Statistically significantly different from

GluR1o,

GluR3o,

(F728Y,G769R)GluR3o, or

(F728Y)GluR3o. Ki values shown are mean ± SEM determined from 3–6 competition curves, performed in triplicate. EC50values shown are mean ± SEM determined from 5–16 concentration-response curves. nH is Hill coefficient (mean ± SEM).

In binding experiments made on Sf9 cell membranes expressing wild-type AMPARs, the compoundsl-glutamate, l-quisqualate, AMPA, and KA exhibited little subtype selectivity (Table 2). In contrast, (R,S)-BrHIBO showed a 69-fold selectivity for GluR1o (Ki = 173 ± 37 nm) over GluR3o (Ki = 12.0 ± 2.4 μm) (Fig.6B, Table 2), which is in agreement with the higher potency of (R,S)-BrHIBO seen at GluR1o. (R,S)-BrHIBO had an affinity for the mutant (F728Y, G769R)GluR3o that was not different from that at GluR1o but was different from GluR3o. The affinity of (R,S)-BrHIBO at the mutant (Y716F, R757G)GluR1o was different from that at both GluR3o and GluR1o but is clearly approaching the lower affinity seen at GluR3o. Therefore, these complementary mutations have effectively reversed the pharmacology of (R,S)-BrHIBO at GluR1o and GluR3o. Yet there was no major change in the l-glutamate affinity at these mutants compared with the wild-type receptors. (R,S)-AMPA showed only a threefold lower affinity at (Y716F, R757G)GluR1o compared with GluR1o and no change in affinity at (F728Y, G769R)GluR3o compared with GluR3o. Because the R/G site is expected to be localized far away from the binding pocket in GluR1o and GluR3o, as it is in GluR2 (Armstrong et al., 1998; Armstrong and Gouaux, 2000), the observed changes in binding affinity could most probably be attributed to the Y/F site. This was verified by subsequent measurement of the affinity of (R,S)-BrHIBO at the mutant (Y716F)GluR1o, which was not different from (Y716F, R757G)GluR1o, and the mutant (F728Y)GluR3o, which was not different from (F728Y, G769R)GluR3o (Table 2). In contrast to BrHIBO, Y/F exchange had the opposite effect on the binding affinity of KA, causing a sevenfold decrease for GluR3o and a 14-fold increase for GluR1o. This suggests that BrHIBO interacts very differently with these residues than does KA.

Not unexpectedly, it was found that GluR2o(R) also binds (R,S)-BrHIBO with an affinity that is about the same as that of GluR1o (Coquelle et al., 2000), because GluR2 has a tyrosine in the position homologous to Y716 of GluR1o. It is predicted that GluR4o should have a low affinity for these analogs, similar to GluR3o, because a phenylalanine residue is present at this position in GluR4o. Furthermore, this similarity in GluR1/GluR2 sensitivity to BrHIBO suggests that use of the GluR2-S1S2 binding site model may provide relevant information about the GluR1 binding site.

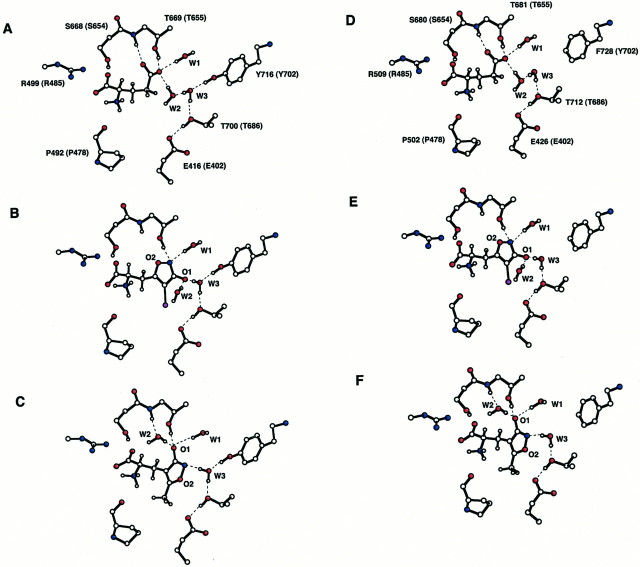

Molecular modeling of GluR1 and GluR3 binding sites

To improve our understanding of the reasons for these differences in binding and desensitization between GluR1o and GluR3o, homology models of the ligand binding domains of GluR1o, GluR3o, and GluR4o were generated using the x-ray crystal structures of GluR2-S1S2 constructs (Armstrong et al., 1998; Armstrong and Gouaux, 2000). Seven amino acids residues interact directly with the ligand within the GluR2-S1S2 constructs: Y450, P478, T480, and R485 from S1, and S654, T655, and E705 from S2. These correspond to the homologous residues Y464, P492, T494, R499, S668, T669, and E719 in GluR1 (numbering from the initiation methionine) or with Y474, P502, T504, R509, S680, T681 and E731 in GluR3. As expected from the high amino acid sequence identity of these proteins within the binding site, all seven of the identified ligand-binding residues in GluR2-S1S2 are predicted to occupy virtually the same spatial positions in GluR1 and GluR3. The question arises as to why AMPA has the same affinity for both GluR1o and GluR3owhile homoibotenic acid analogues such as BrHIBO and MeHIBO exhibit subtype selectivity (Coquelle et al., 2000). To investigate this question, l-glutamate, AMPA, and BrHIBO were docked into the binding sites of the models of GluR1 and GluR3 (Fig.7). Docking was guided by the experimentally observed binding modes of AMPA and glutamate to GluR2-S1S2J (Armstrong and Gouaux, 2000).

Fig. 7.

Binding site models. Models ofl-glutamate (A, D), (S)-BrHIBO (B, E), and (S)-AMPA (C, F) binding to GluR1o (A–C) and GluR3o(D–F). The seven amino acid residues that have been shown to interact directly with ligands in the GluR2-S1S2 constructs correspond to the homologous residues Y464, P492, T494, R499, S668, T669, and E719 in GluR1o (numbering from the initiation methionine) or with Y474, P502, T504, R509, S680, T681, and E731 in GluR3o. Residues are numbered (in Aand D), with the homologous GluR2 residue (Armstrong et al., 1998) indicated in parentheses. Some residues have been removed for clarity. Hydrogen bonds are denoted by dashed lines. W1, W2, and W3 are binding site water molecules. O1 represents the hydroxyl group of AMPA or BrHIBO and O2 is the isoxazole oxygen.

The crystal structures of the GluR2-S1S2 constructs show that a number of water molecules are present within the binding site and that, to some extent, their positions depend on the nature of the bound ligand. On the basis of the very high degree of homology, it is most probable that the water matrix observed within GluR2-S1S2 for a given ligand is also present in GluR1 and GluR3. This hypothesis was confirmed by GRID analysis. On this basis, water structure was added to the models within a radius of 8.5 Å of the ligand. The water molecules W1-W3 are of most importance in the present context. In the case of the docking of BrHIBO (for which no GluR2-S1S2 crystal structure has yet been published), it was necessary to relocate W2. Note that for both BrHIBO and AMPA to interact with the same amino acid residues within GluR2-S1S2, the heterocyclic rings of BrHIBO and AMPA must adopt different orientations. In particular, the negatively charged oxygens (labeled O1 in Fig. 7) of these two ligands must point in opposite directions (Christensen et al., 1992; Greenwood et al., 1998). The O2 of BrHIBO overlaps closely with the position of W2 in the AMPA complex, but by preserving the position of W2 relative to the flipped isoxazole ring of BrHIBO, this water molecule comes to occupy a zone close to that of W2 in the glutamate structure. This is confirmed to be a favorable site for water by GRID analysis. Because hydrogen atoms are undetectable by protein crystallography, and therefore not included in the experimental GluR2-S1S2 structures, their positions must be determined by calculation. Where necessary, Monte Carlo simulations were used to resolve ambiguities in assigning the pattern of H bonding. The positions of selected protons and the alignment of their H bonds are indicated in Figure 7.

DISCUSSION

Receptor desensitization

Agonist binding can cause iGluRs to either open or desensitize (assume a closed state). However, little is known about how agonist binding is coupled to channel gating. Here, we took advantage of the known differences in desensitization properties of the AMPAR subunits (Lomeli et al., 1994; Banke et al., 1997; Stern-Bach et al., 1998) for an investigation of the underlying molecular mechanism or mechanisms involved in GluR1o desensitization. GluR1o was chosen as an example of an AMPAR subunit exhibiting a slow desensitization rate and GluR3o as an example of one having a fast rate. Evaluation of a series of chimeric receptors focused on exchange of amino acid sequences in the S2 region of GluR1obecause previous evidence had suggested that amino acids in the S2 region were important for GluR1o desensitization properties (Mano et al., 1996; Banke et al., 1997). The single-point GluR1o mutations Y714F and Y716F each created receptors having a faster τ than wild type, and point exchanges at other residues in S2 that differ between GluR1oand GluR3o had no effect on τ, except when GluR1o or GluR3o were exchanged at the R/G site, which had been identified previously as being important for controlling AMPAR desensitization properties (Lomeli et al., 1994). However, only a double exchange of Y716F plus R757G in GluR1o converted the desensitization rate to that seen with GluR3o. Therefore, we have identified that residue Y716 also somehow plays a very important role in the desensitization mechanism of GluR1o and that neighboring Y714 can weakly interact with this process also, but cannot completely substitute for Y716. Remarkably, the complementary mutations in GluR3o did not result in an increase in τ toward that of GluR1o; rather, there was little effect on τ. Our interpretation of these results is that the desensitization mechanism or mechanisms of the AMPAR subunits may not be entirely the same, at least with respect to the subunit amino acid residues that are involved. It is likely that other amino acid residues in the S1 region, or perhaps even residues N-terminal to S1, are involved in the desensitization mechanism. Our own data with chimera 2 and other mutagenesis studies (Uchino et al., 1992; Mano et al., 1996; Stern-Bach et al., 1998) support this interpretation.

Residues Y714 and Y716 are not involved in recovery from desensitization or deactivation but seem to be specifically involved in controlling the rate of GluR1o desensitization. The deactivation rate constant (τdeact) forl-glutamate at GluR1o measured in this study is in good agreement with the values given in the literature (Mosbacher et al., 1994; Partin et al., 1996). However, no changes in τdeact were observed with the mutant GluR1o receptors. In contrast, all of the multiple-point GluR1o mutants containing the exchange R757G exhibited faster recovery times than wild-type GluR1o, whereas neither the double exchange of Y714F plus Y716F nor the Y716F single exchange altered τrec. This is consistent with the finding that the R/G site controls recovery from desensitization in GluR1o.

Binding site interactions

In addition to effects on the time course of receptor desensitization and deactivation, it was a possibility that the Y/F exchange in GluR1o was somehow directly affecting agonist binding. Previous studies have shown that the S1 region and the N-terminal portion of the S2 region are involved in ligand binding (Uchino et al., 1992; Stern-Bach et al., 1994; Li et al., 1995; Mano et al., 1996). Subsequently, the x-ray crystal structures were solved for both the ligand-bound and unbound (apo) versions of soluble GluR2-S1S2 binding site constructs (Armstrong et al., 1998; Armstrong and Gouaux, 2000). This indicated that the C-terminal region of S2, which includes the flip/flop region as well as the R/G site, is located far away from the binding pocket, on the solvent-exposed surface of the protein. In contrast, residue Y716 lies in the N-terminal part of the S2 region of GluR1o, within the binding pocket. So, could an exchange of binding site properties between GluR1o and GluR3o be seen on Y/F exchange?

Whereas most agonists at AMPARs show little or no subtype selectivity, (R,S)-BrHIBO exhibited a 28-fold preference for GluR1o compared with GluR3oin terms of potency (EC50) and a 69-fold preference in terms of affinity (Ki). The fact that both BrHIBO potency and affinity could be transposed by the Y/F exchange between GluR1o and GluR3o leads to the conclusion that Y716 does interact in some manner with (R,S)-BrHIBO in the GluR1o binding domain. Because no change in EC50, compared with wild type, was observed with the mutant (Y714F, R757G)GluR1o, it is also concluded that the Y714 residue is not involved in agonist interactions. Therefore, Y716 seems to play a key role in determining both the slower desensitization rate of GluR1oand the higher affinity of a subtype-selective agonist. This indicates that there can indeed be some mechanistic link between agonist binding and receptor desensitization. A connection between binding and desensitization is also suggested from recently published GluR2-S1S2 x-ray crystal structure data (Armstrong and Gouaux, 2000), where a correlation is seen between the extent of S1-S2 domain closure produced by a ligand and the extent of desensitization experimentally observed for that ligand.

Molecular modeling

Armstrong et al. (1998) predict that E402 (E416 in GluR1o) of the S1 region interacts with T686 (T700 in GluR1o) of the S2 region via an H bond helping to stabilize the closed conformation. This may be thought of as an interdomain “lock” of the type suggested by Abele et al. (2000). We therefore came to focus on the hydrogen-bonded connection of the ligand to this lock through W3 and, in particular, how the nonconserved aromatic residue (Y/F) proximal to W3 influences network stability. By inspection, it is clear that W3 plays a critical role connecting ligand and lock, although its role is lessened in the case of glutamate binding by the interposed W2. Glutamate assigns an equal charge to both of its distal carboxylate oxygens, whereas AMPA and BrHIBO present a greater charge on O1 and less on the ring nitrogen. BrHIBO directs a negatively charged oxygen toward W3, whereas AMPA presents the lesser-charged nitrogen. At the same time, the acidity of the W3 proton forming an H bond to the ring is affected by Y716. Exchange to a phenylalanine abolishes the H-bond donation to W3, causing a net decrease of positive charge on the proton in question and thus decreasing the strength of the H bond it makes with the ring. Therefore, the binding of HIBO derivatives ought to be more sensitive than that of AMPA or glutamate to this Y/F position because they present the more strongly charged O1 to this W3 proton. Further modeling was undertaken to quantify this.

Cooperative H bonding is a subtle electronic effect requiring the use of quantum mechanics for adequate modeling (Masella and Flament, 2000). Therefore, we conducted high-level ab initio calculations on a simplified model of the region around W3. Dimethylisoxazolol was chosen to represent both MeHIBO and AMPA to allow more accurate perturbative calculations rather than attempting to compensate for the presence of bromine (Fig. 8). The calculations show clearly that breaking the H bond between the phenyl ring and W3 causes a decrease in the acidity of the hydrogen-bonding W3 proton (Mulliken population analysis gives a difference of 0.02 charge units for both I and II). It is also clear that the presence or absence of the hydroxyl has quite a different effect on the total energies of models I and II: the tyrosine-OH of GluR1 lends more stability when the strongly negative O1 is proximal to W3. The difference in the relative stabilities is 1.65 kcal/mol. By using the proportionality factor of 1.36 to convert kilocalories per mole to log units at 298°K, the net result is a prediction that the ratio between the selectivities of MeHIBO and AMPA at GluR1 versus GluR3 will be 16:1. Given that AMPA is roughly equipotent at both receptors, MeHIBO is predicted to bind 16 times more weakly at GluR3o than GluR1o. This finding is in excellent agreement with the experimentally observed binding affinities of MeHIBO (Ki = 471 ± 134 nm at GluR1o and 7270 ± 2200 nm at GluR3o) (Coquelle et al., 2000). Therefore, we conclude that the observed binding selectivity of the HIBO derivatives for GluR1 over GluR3 resides primarily in the effect of the Y/F position on the hydrogen-bonding network linking the ligand with W3 to Y716 in GluR1. Neither glutamate nor AMPA show this susceptibility because of the weaker links between W3 and the ligand and, in the latter case, because of a rather weak connection involving W2, for which only a small decrease in affinity is observed.

Fig. 8.

Ab initio modeling of ligand binding. Simplified models of AMPA (I) and MeHIBO (II) binding to GluR1 (TYR) and GluR3 (PHE) under constrained optimization according toab initio molecular orbital theory (see Materials and Methods). Quantum chemical energy calculations yield total energies (Hartree) at B3LYP/6–31+G(d): I-TYR, −859.7460; II-TYR, −859.7462; I-PHE, −784.5093; II-PHE, −784.5069. Relative energy differences: TYR ΔE, −0.18 kcal/mol; PHE ΔE, +1.47 kcal/mol.

Finally, because the water molecule W3 connects Y716 in GluR1o (Fig. 7A–C) with the T700–E416 H bond, it is also probable that the water structure and H-bond matrix, along with the altered volume occupied by tyrosine versus phenylalanine, influence the desensitization properties of the receptor, as observed here in the case ofl-glutamate. Further refinements of our models, including quantum mechanical calculations of the bond energy of the T700–E416 H bond, are underway and should shed more light on the role of this region in controlling desensitization as well as binding.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Grants 9700761, 9900010, and 9900201 from the Danish Medical Research Council, by the Lundbeck, Alfred Benzon, and Novo Nordisk Foundations, and by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. We thank Dr. D. Bowie for discussions and critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank Dr. Ulf Madsen for generously supplying us with (R,S)-4-bromohomoibotenic acid.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Darryl S. Pickering, Department of Pharmacology, The Royal Danish School of Pharmacy, 2 Universitetsparken, DK-2100 Copenhagen, Denmark. E-mail:picker@dfh.dk.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abele R, Keinänen K, Madden D. Agonist-induced isomerization in a glutamate receptor ligand-binding domain. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:21355–21363. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M909883199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armstrong N, Gouaux E. Mechanisms for activation and antagonism of an AMPA-sensitive glutamate receptor: crystal structures of the GluR2 ligand binding core. Neuron. 2000;28:165–181. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00094-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armstrong N, Sun Y, Chen GQ, Gouaux E. Structure of a glutamate-receptor ligand-binding core in complex with kainate. Nature. 1998;395:913–917. doi: 10.1038/27692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banke TG, Schousboe A, Pickering DS. Comparison of the agonist binding site of homomeric, heteromeric, and chimeric GluR1o and GluR3o AMPA receptors. J Neurosci Res. 1997;49:176–185. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4547(19970715)49:2<176::aid-jnr6>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bittigau P, Ikonomidou C. Glutamate in neurologic diseases. J Child Neurol. 1997;2:471–485. doi: 10.1177/088307389701200802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brose N, Huntley GW, Stern-Bach Y, Sharma G, Morrison JH, Heinemann SF. Differential assembly of coexpressed glutamate receptor subunits in neurons of rat cerebral cortex. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:16780–16784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christensen IT, Ebert B, Madsen U, Nielsen B, Brehm L, Krogsgaard-Larsen P. Excitatory amino acid receptor ligands. Synthesis and biological activity of 3-isoxazolol amino acids structurally related to homoibotenic acid. J Med Chem. 1992;35:3512–3519. doi: 10.1021/jm00097a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coquelle T, Christensen JK, Banke TG, Madsen U, Schousboe A, Pickering DS. Agonist discrimination between AMPA receptor subtypes. NeuroReport. 2000;11:2643–2648. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200008210-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dingledine R, Borges K, Bowie D, Traynelis SF. The glutamate receptor ion channels. Pharmacol Rev. 1999;51:7–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferrer-Montiel AV, Montal M. Pentameric subunit stoichiometry of a neuronal glutamate receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2741–2744. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.2741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goodford PJ. A computational procedure for determining energetically favorable binding sites on biologically important macromolecules. J Med Chem. 1985;28:849–857. doi: 10.1021/jm00145a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenwood JR, Vaccarella G, Capper HR, Allan RD, Johnston GAR (1998) Heterocycles as bioisosteres for the ω-carboxylate moiety of glutamate in AMPA receptor agonists: a review and theoretical study. Internet J Chem http://www.ijc.com 1:38.

- 13.Hansen JJ, Nielsen B, Krogsgaard-Larsen P, Brehm L, Nielsen EØ, Curtis DR. Excitatory amino acid agonists. Enzymic resolution, X-ray structure, and enantioselective activities of (R)- and (S)-bromohomoibotenic acid. J Med Chem. 1989;32:2254–2260. doi: 10.1021/jm00130a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hollmann M, Heinemann S. Cloned glutamate receptors. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1994;17:31–108. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.17.030194.000335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jensen JB, Schousboe A, Pickering DS. AMPA receptor-mediated excitotoxicity in neocortical neurons is developmentally regulated and dependent upon receptor desensitization. Neurochem Int. 1998;32:505–513. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(97)00130-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jensen JB, Schousboe A, Pickering DS. Role of desensitization and subunit expression for kainate receptor-mediated neurotoxicity in murine neocortical cultures. J Neurosci Res. 1999;55:208–217. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19990115)55:2<208::AID-JNR8>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koike M, Tsukada S, Tsuzuki K, Kijima H, Ozawa S. Regulation of kinetic properties of GluR2 AMPA receptor channels by alternative splicing. J Neurosci. 2000;20:2166–2174. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-06-02166.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krogsgaard-Larsen P, Honoré T, Hansen JJ, Curtis DR, Lodge D. New class of glutamate agonist structurally related to ibotenic acid. Nature. 1980;284:64–66. doi: 10.1038/284064a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krupp JJ, Westbrook GL. An orphan glutamate channel points the way to the gates. Nature. 2000;3:301–302. doi: 10.1038/73846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lawrence CE, Altschul SF, Boguski MS, Liu JS, Neuwald AF, Wootton JC. Detecting subtle sequence signals: a Gibbs sampling strategy for multiple alignment. Science. 1993;262:208–214. doi: 10.1126/science.8211139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li F, Owens N, Verdoorn TA. Functional effects of mutations in the putative agonist binding region of recombinant α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole-propionic acid receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 1995;47:148–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liman ER, Tytgat J, Hess P. Subunit stoichiometry of a mammalian K+ channel determined by construction of multimeric cDNAs. Neuron. 1992;9:861–871. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90239-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lomeli H, Mosbacher J, Melcher T, Hoger T, Geiger JR, Kuner T, Monyer H, Higuchi M, Bach A, Seeburg PH. Control of kinetic properties of AMPA receptor channels by nuclear RNA editing. Science. 1994;266:1709–1713. doi: 10.1126/science.7992055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mano I, Teichberg VI. A tetrameric subunit stoichiometry for a glutamate receptor-channel complex. NeuroReport. 1998;9:327–331. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199801260-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mano I, Lamed Y, Teichberg VI. A venus flytrap mechanism for activation and desensitization of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptors. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:15299–15302. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.26.15299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Masella M, Flament J-P. Influence of cooperativity on hydrogen bond networks. Molecular Simulation. 2000;24:131–156. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mayer ML, Westbrook GL. The physiology of excitatory amino acids in the vertebrate central nervous system. Prog Neurobiol. 1987;28:197–276. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(87)90011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mohamadi F, Richards NGJ, Guida WC, Liskamp R, Lipton M, Caufield C, Chang G, Hendrickson T, Still WC. MacroModel: an integrated software system for modeling organic and bioorganic molecules using molecular mechanics. J Comput Chem. 1990;111:440–467. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mosbacher J, Schoepfer R, Monyer H, Burnashev N, Seeburg PH, Ruppersberg JP. A molecular determinant for submillisecond desensitization in glutamate receptors. Science. 1994;266:1059–1062. doi: 10.1126/science.7973663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nielsen B, Banke TG, Schousboe A, Pickering DS. Pharmacology of [3H]AMPA binding to homomeric and heteromeric GluR1o and GluR3o receptors expressed in Sf9 insect cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;360:227–238. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00668-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paas Y. The macro- and microarchitectures of the ligand-binding domain of glutamate receptors. Trends Neurosci. 1998;21:117–125. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(97)01184-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Partin KM, Patneau DK, Mayer ML. Cyclothiazide differentially modulates desensitization of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor splice variants. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;46:129–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Partin KM, Fleck MW, Mayer ML. AMPA receptor flip/flop mutants affecting deactivation, desensitization, and modulation by cyclothiazide, aniracetam, and thiocyanate. J Neurosci. 1996;16:6634–6647. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-21-06634.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosenmund C, Stern-Bach Y, Stevens CF. The tetrameric structure of a glutamate receptor channel. Science. 1998;280:1596–1599. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5369.1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schuler GD, Altschul SF, Lipman DJ. A workbench for multiple alignment construction and analysis. Proteins. 1991;9:180–190. doi: 10.1002/prot.340090304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sommer B, Keinänen K, Verdoorn TA, Wisden W, Burnashev N, Herb A, Kohler M, Takagi T, Sakmann B, Seeburg PH. Flip and flop: a cell-specific functional switch in glutamate-operated channels in the CNS. Science. 1990;249:1580–1585. doi: 10.1126/science.1699275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stern-Bach Y, Bettler B, Hartley M, Sheppard PO, O'Hara PJ, Heinemann SF. Agonist selectivity of glutamate receptors is specified by two domains structurally related to bacterial amino acid-binding proteins. Neuron. 1994;13:1345–1357. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90420-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stern-Bach Y, Russo S, Neuman M, Rosenmund C. A point mutation in the glutamate binding site blocks desensitization of AMPA receptors. Neuron. 1998;21:907–918. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80605-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Uchino S, Sakimura K, Nagahari K, Mishina M. Mutations in a putative agonist binding region of the AMPA-selective glutamate receptor channel. FEBS Lett. 1992;24:253–257. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)81286-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]