Abstract

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a disorder of two pathologies: amyloid plaques, the core of which is a peptide derived from the amyloid precursor protein (APP), and neurofibrillary tangles composed of highly phosphorylated tau. Protein kinase C (PKC) is known to increase non-amyloidogenic α-secretase cleavage of APP, producing secreted APP (sAPPα), and glycogen synthase kinase (GSK)-3β is known to increase tau phosphorylation. Both PKC and GSK-3β are components of the wnt signaling cascade. Here we demonstrate that overexpression of another member of this pathway, dishevelled (dvl-1), increases sAPPα production. The dishevelled action on APP is mediated via both c-jun terminal kinase (JNK) and protein kinase C (PKC)/mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase but not via p38 MAP kinase. These data position dvl-1 upstream of both PKC and JNK, thereby explaining the previously observed dual signaling action of dvl-1. Furthermore, we show that human dvl-1 and wnt-1 also reduce the phosphorylation of tau by GSK-3β. Therefore, both APP metabolism and tau phosphorylation are potentially linked through wnt signaling.

Keywords: dishevelled, Alzheimer's disease, amyloid precursor protein, PKC, JNK, GSK-3, tau, wnt

Amyloid precursor protein (APP) is a ubiquitous membrane-bound protein, the metabolism of which is central to the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease (AD). APP is cleaved at three sites, at least, by α-, β-, and γ-secretases; β- and γ-secretase cleavage together result in the amyloid β-peptide (Aβ) that is deposited in plaques in AD and a secreted fragment of APP (sAPPβ). α-secretase, on the other hand, cleaves APP within the Aβ sequence, resulting in a cell-associated C-terminus sequence and a longer secreted fragment (sAPPα). Although cleavage at all three sites occurs in normal brain, the amyloid cascade hypothesis (Hardy and Higgins, 1992) postulates that amyloid generation is at the primary event in AD pathogenesis, presumably because of disruption of the normal balance between α-secretase and β-/γ-secretase cleavage. Mutations in the APP gene and the presenilin genes, associated with familial AD, result in increased production of total Aβ or relatively more of the longer Aβ42 (Borchelt et al., 1996; Scheuner et al., 1996), and recent evidence suggests that the presenilins either have or are tightly coupled to γ-secretase activity (De Strooper et al., 1998; Wolfe et al., 1999). Multiple lines of evidence have demonstrated that the metabolism of APP by α-secretase is regulated at least partially by PKC (Nitsch et al., 1992; Hung et al., 1993; Slack et al., 1993; Mills and Reiner, 1999). Increasing PKC activity results in increased sAPP, and decreased Aβ production results in non-neuronal cell lines (Buxbaum et al., 1993; Hung et al., 1993) and brain (Savage et al., 1998), although in neurons in culture both sAPP and Aβ may increase (LeBlanc et al., 1998).

Although PKC regulates α-secretase processing, the mechanism for this is not known. PKC contributes to diverse signaling pathways, including MAP kinase signaling, and MAP kinase inhibitors attenuate muscarinic-induced sAPP secretion (Haring et al., 1998), suggesting that the PKC effect on sAPPα production is via MAP kinase. PKC also transduces the wnt/wingless signal, resulting in glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β) inhibition (Goode et al., 1992; Cook et al., 1996). Because GSK-3β has been shown to regulate tau phosphorylation in cells, including in neurons, this suggested a possible link between two critical processes in Alzheimer's disease. We therefore examined the role of wnt signaling in regulating APP metabolism and tau phosphorylation through the intermediary phosphoprotein, dishevelled.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and plasmids. Cell lines expressing either APP695wt or APP695swe were generated with complete cDNA cloned into the pcDNA3(−) (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA) vector with the addition of a Kozak sequence at the 5′ end to enhance expression. The resulting vector containing APP695 cDNA was transfected into human embryonic kidney (HEK)293 cells using Transfectam (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Stable transfectants were selected and maintained in culture with 500 μg/ml geneticin sulfate, G418 (Life Technologies). Ten independently selected clones were analyzed for APP expression and Aβ production. Cells were grown in a 50% (v/v) mixture of NUT 12 (HAM with glutamine) and DMEM with HEPES modification. Media also contained 10% (v/v) FBS, glutamine (100 IU/ml), penicillin–streptomycin, and geneticin (0.5 mg/ml) (Sigma, Poole, UK).

A full-length cDNA clone of human dishevelled 1 (gift from G. Novelli, Universita Tor Vergata, Rome) was tagged with a c-myc epitope at the C terminus and subcloned into pCIneo (Promega, Madison, WI). A 65 mer oligonucleotide primer was prepared (Oswel, Southampton, UK) containing a NotI site, followed by a stop codon, then a 30 base pair sequence encoding the c-myc epitope, a BamHI site, and 20 base pairs from the 3′ end of the human dishevelled 1 (hdvl-1) gene before the stop codon. PCR was used to construct a dvl-1-myc fusion using the above primer with a 20 mer primer at positions 1872–1891 from the human dvl-1 sequence. The PCR fragment generated was cloned into pT7 (Novagen, Madison, WI), and the fidelity of the PCR fragment was confirmed by DNA sequencing. Double digestion with NotI and FseI generated a 3′hdvl1-myc 0.3 kb fragment, which was ligated to a 1.7 kb 5′EcoRI–FseI fragment and pCIneo, previously digested and linearized with EcoRI and NotI (Promega). The entire coding sequence of the hdvl1 clone was sequenced.

The 3′ end of human dvl-2 was cloned from a human cerebellum cDNA library. The resulting PCR product was digested with NHE1 and BAMH1 and ligated to a 2.2 kb BamHI and XHO1 digested PCR fragment cloned from a separate cDNA hippocampal library containing the entire 5′ end of dvl-2. The resulting ligated complete cDNA was subcloned into pCIneo. Full-length human dvl-3 was a gift of Dr. Pizutti (Universita de Milano, Milan) and was subcloned into pCIneo betweenEcoR1 and NotI. The PCR products and the completed ligation product were sequenced at every step to ensure that the whole gene was contained in the plasmid and that its orientation was correct.

Other constructs that were used encoded the kinases GSK-3β (Lovestone et al., 1994), JNK-3, and p38 MAP kinase (a gift from B. Zanke, Ontario Cancer Institute, Toronto), as reported previously. A plasmid encoding for JNK inhibitory protein (JIP-1; a gift from R. Davies, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Worcester, UK), previously shown to inhibit JNK signaling (Dickens et al., 1997), was used in some experiments. A human c-myc-tagged Wnt-1 construct (Wnt-1-myc) subcloned into the expression vector pcDNA3.1, as described previously (Naylor et al., 2000), was a kind gift from T. Dale (Institute of Cancer Research, London).

Transfections and chemical treatments. Cells were transfected using Lipofectamine (Life Technologies, Paisley, UK) according to manufacturer's protocol. In each experiment control cells were transfected with empty vector. Transfection medium was left on the cells overnight and then replaced with OPTIMEM (Life Technologies) for an additional 24 hr. Medium was removed, and cells were incubated in 1 ml of fresh OPTIMEM for 1 hr; these 1 hr incubation samples were harvested for analyses. In some experiments, cells transfected with dvl-1 were incubated in OPTIMEM containing one of the following reagents: a PKC inhibitor, bisindolylmaleimide-I, used at 1 and 10 μm; a compound that prevents the activation of MAP/ERK kinase (Alessi et al., 1995), PD98059, used at 10 and 20 μm; a p38 kinase inhibitor, PD169316, used at 89 nm; a PKC activator, phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (TPA), used at 150 nm (C-N Biosciences, Nottingham, UK); and the GSK-3β inhibitor, lithium chloride (Sigma, Poole, UK), used at 25 mm.

Protein analysis. After the 1 hr incubation period, media was removed from the cells and centrifuged for 5 min at 121 ×g. The supernatants were desalted using NAP10 columns (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Buckinghamshire, UK), then concentrated using a Speed Vac (Savant Instruments). The concentrates were dissolved in Laemmli sample buffer, boiled for 5 min, separated by SDS-PAGE, and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. These were immunoblotted using the APP monoclonal antibody 22C11 (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany). In some instances membranes were immunoblotted using either a sAPPα-specific monoclonal antibody (6E10; Senetek) or a rabbit polyclonal antiserum (G26) that specifically recognized sAPPβ, which was raised against the neo C terminus of wild-type sAPPβ (ISEVKM). Blots were developed using ECL reagents (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

In some experiments cell lysates were prepared. Media was removed from the cells, which then were washed with PBS and homogenized in Laemmli sample buffer. These samples were then boiled for 5 min before SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with the APP antibody, 22C11.

Media samples were assayed for Aβ40 and Aβ42 using a characterized sandwich ELISA. The Aβ40 and Aβ42 were captured using the Ban50 antibody and detected using BA27 HRP and BC05 HRP antibodies, respectively; imaging was performed using peroxidase substrate/solution (Kirkegaard and Perry Laboratories). Aβ42 as a percentage of Aβ40 was then calculated (Murphy et al., 1999).

Pulse–chase experiments. Cells were plated on 60 mm dishes and grown to 95% confluency. They were then transiently transfected with Dvl-1 myc or with pcINeo as described above, after which they were preincubated in methionine-free, serum-free media for 15 min. The cells were then incubated with 100 μCi of [3535]methionine (New England Biolabs) in fresh OPTIMEM for 30 min, washed, and then incubated in fresh OPTIMEM. At 0 min, 1 hr, and 4 hr, cells were harvested by washing three times with chilled PBS and were then scraped into chilled PBS. The cells were then pelleted by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 5 min, and the pellets were lysed in lysis buffer (Tris base, 50 mm; NaCl, 150 mm; EDTA, 1 mm; Triton X-100 1%; PMSF, 142 mm; protease inhibitor cocktail tablet, one per 7 ml; Roche, Hertforshire, UK) for 20 min on ice. The lysates were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatants were cleared by incubating with Sepharose AG beads (Autogen Bioclear) for 1 hr at 4°C on a roller. After centrifugation to pellet out the beads, 20 μl of 22C11 was added to the cleared supernatants (after a Bradford assay was performed to ensure that there was equal protein content in each tube) and incubated overnight at 4°C on a roller. Sepharose AG beads were added to each tube and incubated for 2 hr at 4°C on a roller. The bead conjugates were then pelleted by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 5 min, washed three times with lysis buffer, and then dissolved in 2× SDS Laemmli buffer. They were then boiled for 10 min and centrifuged for 5 min at 13,000 rpm. The supernatants were separated by SDS electrophoresis, the gels dried down and then exposed to phosphorimaging, and the integrated intensity of the band per unit area was measured.

Immunocytochemistry. In some experiments, dvl-1-transfected cells were plated onto coverslips and fixed in ice-cold methanol. The efficiency of dvl-1 transfection was assessed by immunofluorescence, using an anti-dvl-1 polyclonal antibody raised against a 15 amino acid sequence selected from the C-terminal DEP domain (amino acids 556–571) of human dvl-1. In experiments to determine wnt signaling, β-catenin was visualized with a polyclonal antibody recognizing human β-catenin (Transduction), and wnt-1-myc was visualized with a monoclonal antibody recognizing the myc tag (9E10, Sigma).

Analysis of data. Western blots were scanned and quantified using Bio-Rad Quantity One densitometry software, and data were analyzed by unpaired Student's t tests assuming unequal variance using the software package SPSS. For every experiment the amount of sAPP in the experimental situation relative to sAPP in the control for each individual blot was calculated (thus normalizing control values to 1).

RESULTS

Dishevelled increases sAPP secretion in non-neuronal cells.

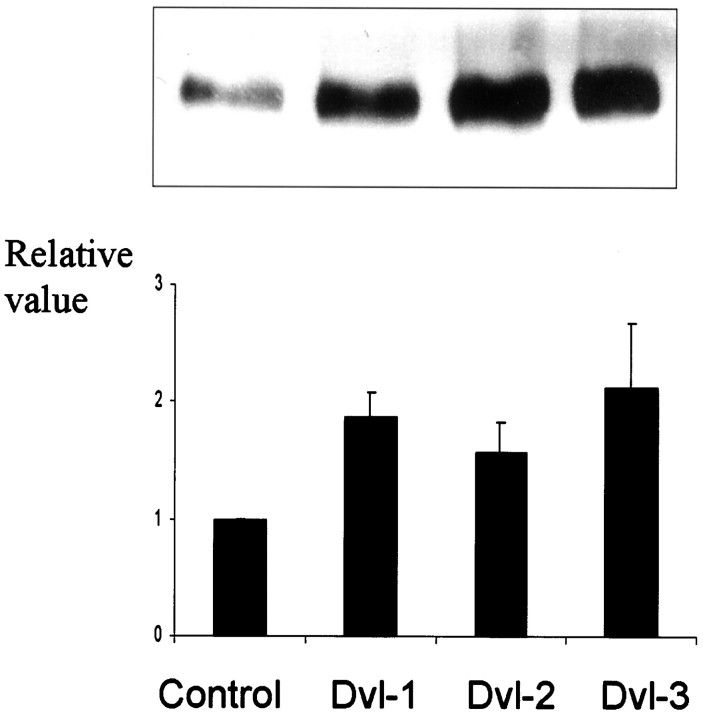

Human HEK293 cells stably overexpressing full-length human wild-type APP695 were used to examine the effects of manipulating the wnt pathway on APP metabolism, secreted APP species being readily detectable from the medium of this cell line. First, these cells were transiently transfected with cDNA coding for hdvl-1, a component of the wnt pathway that when activated by an external wnt signal or by overexpression results in decreased activity of GSK-3β on its substrates (Anderton et al., 2000). sAPP secretion from control cells overexpressing APP (and transfected with empty vector) and from the same cell line transiently transfected with cDNA coding for dvl-1 were compared by immunoblot analysis. sAPP secretion by dvl-1-transfected cells was twice that of cells not expressing dvl-1 (combined results from repeated experiments; n = 10;p < 0.001) (Fig. 1). This increase in sAPP in the medium is all the more remarkable because the change must be attributable only to that fraction of cells expressing dvl-1. We determined dvl-1 expression using both Western blotting and immunofluorescence microscopy using the dvl-1 antibody; ∼30% of cells expressed dvl-1, and neither the proportion nor the amount of dvl-1 protein showed substantial changes between experiments (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Dishevelled increases sAPP production. sAPP in the medium of HEK293 cells stably expressing wtAPP695 was assessed by immunoblotting with an antibody (22C11) recognizing all species of secreted APP. Transient transfection with dvl-1, dvl-2, or dvl-3 increased sAPP as demonstrated on this example and by densitometry of multiple experiments (n = 10;p < 0.05 in all cases).

We then examined the effects of human dvl-2 and dvl-3 on APP secretion. In parallel experiments, transient expression of all three human isoforms of dvl resulted in an increase in sAPP secretion into the media (n = 10; p < 0.05 in all three cases) (Fig. 1). There were no significant differences between the different isoforms.

Dvl-1 stimulates α-secretase activity

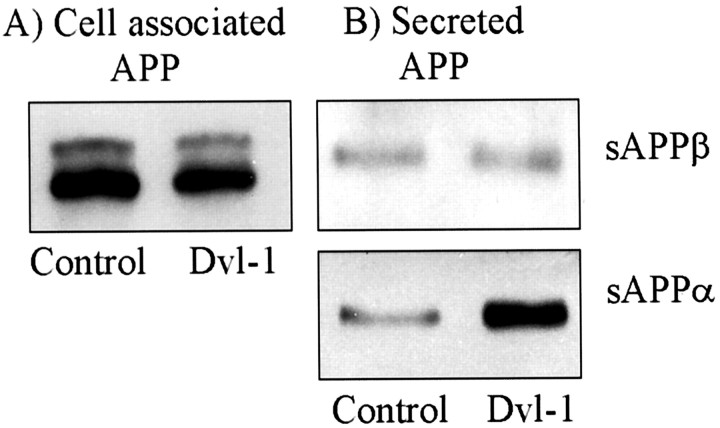

The increase in sAPP observed could have been caused by an effect of dvl-1, either directly or indirectly, on an APP-secretase activity, or because dvl-1 transduces signals to transcription factors, could have been caused by an increase in overall expression of APP. However, cell-associated APP in lysates from cells did not significantly change in response to overexpression of dvl-1, suggesting that the effect was indeed mediated through altering secretase activity on APP (Fig.2A).

Fig. 2.

Dvl-1 increases sAPPα but not total APP expression or sAPPβ secretion. Transfection of dvl-1 had no effect on the total expression of APP as assessed by the N-terminal antibody 22C11 when used to probe cell lysates (A). Transfection of dvl-1 resulted in an increase in sAPP produced by α-secretase but not those products resulting from β-secretase processing, as demonstrated by Western blots of concentrated media using antibodies specific for each (B).

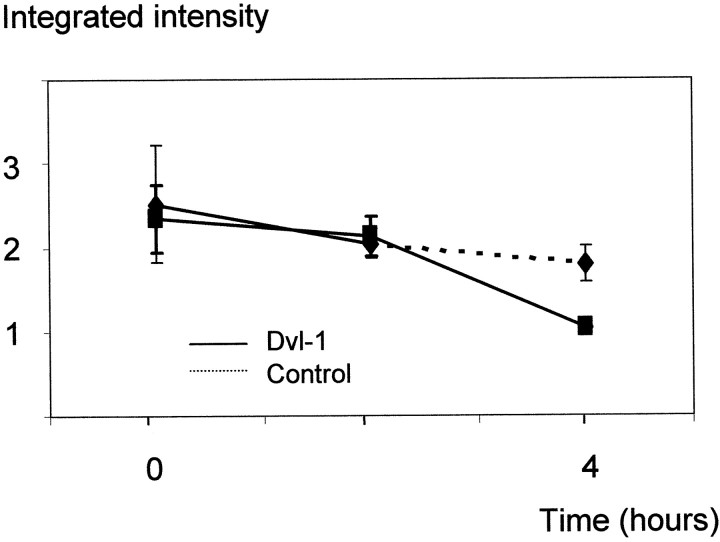

To confirm this we performed a pulse–chase experiment comparing the turnover of sAPP in cells transfected with empty vector with those transfected with dvl-1. Neither the amount nor the turnover of sAPP was altered by expression of dvl-1 in the first hour, the period when sAPPα generation doubles. An increase in the turnover of sAPP was apparent in dvl-1-transfected cells by 4 hr, in line with the findings above and indicating increased metabolism of APP (Fig.3).

Fig. 3.

Dvl-1 has no effect on the rate of turnover of halo-APP. Cells stably expressing APPwt with and without transient dvl-1 transfection were compared using metabolic labeling and pulse chase. Cells were incubated in methionine-free medium followed by incubation in 35S-methionine-containing medium. At baseline and at 2 and 4 hr after the pulse, APP was immunoprecipitated from lysed cells using 22C11 and halo-APP quantitated by autoradiography and densitometry. No significant differences at any time point were observed (n = 3), demonstrating that dvl-1 does not affect turnover of total APP.

APP is metabolized by at least three proteolytic activities, and although we expected that the majority of sAPP generated was as a result of α-secretase cleavage, it was possible that the effect we observed was mediated by increased secretion of APP species metabolized by other secretases. We examined this using antibodies specific to APP cleaved by α-secretase (6E10) and β-secretase (G26; Glaxo Wellcome). In each experiment we found that although the amount of α-secretase-cleaved sAPP species increased in the media, no effect was seen on β-secretase species (Fig. 2B).

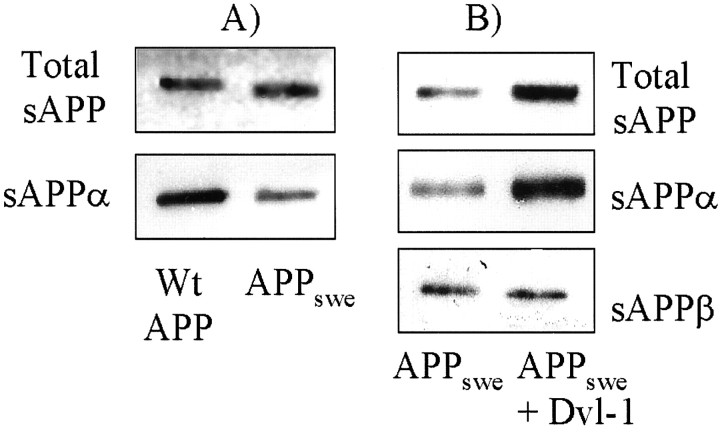

The Swedish ((K670N/M671L)) mutation in APP associated with familial AD increases the metabolism of APP by β-secretase at the expense of α-secretase (Haass et al., 1995; Thinakaran et al., 1996). We therefore examined the effect of dvl-1 on APP metabolism in HEK293 cells stably expressing APPswe. First, we confirmed that in these cells there is proportionally less sAPPα. Medium from wild-type cells had more than twice the amount of sAPPα (as measured using densitometry with the antibody 6E10) than medium from Swedish cells, despite near equal loading of total cell-associated sAPP (Fig.4A). However, transient transfection of dvl-1 in these cells had the same effect as in wild-type cells, resulting in an increase in sAPP and specifically in a substantial increase in sAPPα and not sAPPβ (Fig.4B).

Fig. 4.

Dvl-1 increases sAPPα in APPswe cells. APP expression in cells expressing APPswe was similar to cells expressing APPwt when cell lysates were compared using 22C11 immunoblotting. However, APPswe cells possess a bias toward amyloidogenic metabolism, as demonstrated by decreased sAPPα secretion into the medium (A). Despite this bias, transient expression of dvl-1 in these cells increased sAPP release, and this release was caused by sAPPα and not sAPPβ (B).

We then went on to examine the production of amyloid peptides Aβ40 and Aβ42 generated in these cell lines by ELISA using the BAN50/BA27 BAN50/BC05 combination of antibodies, respectively (Murphy et al., 1999). The mean value of neither Aβ40 nor Aβ42 significantly differed in HEK293 cells expressing only APPswe compared with the same cells transiently transfected with dvl-1 (ratio of Aβ42/40 0.08 vs 0.06; nonsignificant difference). Previously in non-neuronal cells the generation of Aβ peptide has been shown to have a reciprocal relationship with that of the sAPPα peptide (Gabuzda et al., 1993). However, this relationship between “amyloidogenic” metabolism and “non-amyloidogenic” metabolism was not preserved in neurons or in neuroblastoma cell lines (Dyrks et al., 1994; LeBlanc et al., 1998), suggesting that Aβ generation in some cell types may not be coupled to sAPP generation. To determine whether this was the case in the stable cell line that we were using, the HEK293 APPswe cells were treated with phorbol ester and Aβ40 quantified by ELISA, and in the same cells, sAPP was measured in the medium by immunoblotting using 22C11. A significant reduction in Aβ40 was seen with 1μm TPA treatment (44% reduction; p < 0.0005; n = 6) coupled with an increase in sAPP as expected. At a lower concentration of TPA (150 nm), a small and nonsignificant reduction in Aβ40 was observed (20% reduction) despite an increase in sAPP being apparent on Western blots. The different concentrations of TPA did not affect the amount of sAPP in the medium (6.6 vs 5.1; n= 8; NS). These data demonstrate that the generation of APPs is more sensitive, at least in these cells, to signaling changes than the generation of Aβ. We were unable to detect Aβ in medium from APPwt cells consistent with previous findings that Aβ generation is minimal in similar cell lines.

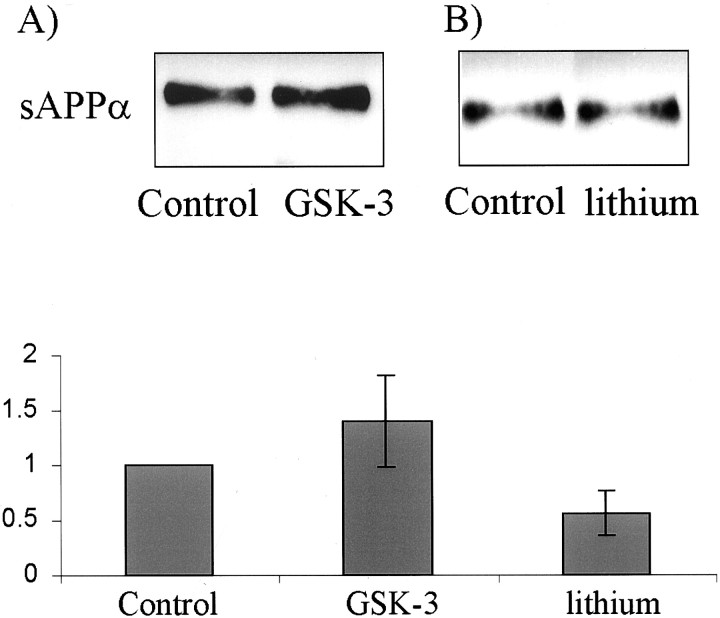

The action of dishevelled signaling on sAPP is not mediated via GSK-3β

Because the wnt signal is transduced via dishevelled, resulting in the inhibition of GSK-3β, we examined the effects of both overexpression of GSK-3β and inhibition of GSK-3β on sAPP secretion. We predicted that inhibition of GSK-3β with lithium (Klein and Melton, 1996) would mimic the dvl-1 signal, leading to an increase in sAPP secretion. However, this was not the case, and lithium did not increase sAPP secretion (n = 4; nonsignificant change) (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, overexpression of cDNA for human GSK-3β did not affect the secretion of sAPP into the medium (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

The effects of dvl-1 on sAPPα are not mediated via GSK-3β. Inhibition of GSK-3β with lithium, mimicking the dvl signal, did not increase sAPPα production (A), and overexpression of GSK-3β, countering the dvl signal, did not reduce sAPPα (B). In all cases, densitometry data are normalized relative to controls for each individual experiment.

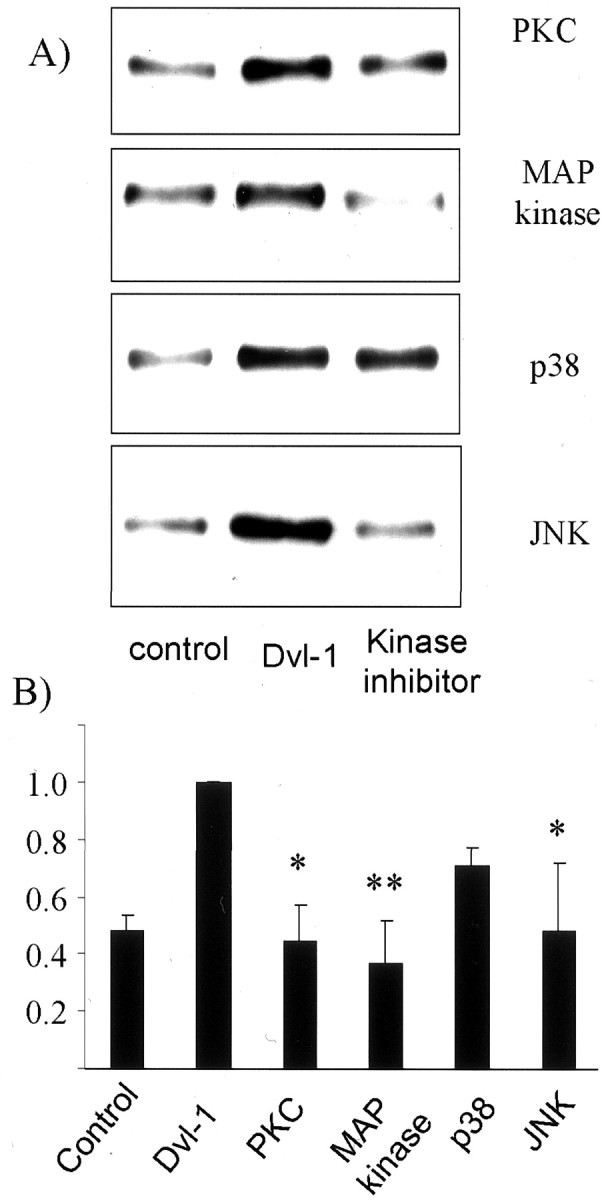

The action of dishevelled on sAPP is mediated via PKC/MAP kinase and by JNK signaling

Because the dvl-1 effect on α-secretase was not mediated, as we had predicted, via GSK-3β, we examined other pathways thought to be involved in dvl-1 signaling. Wnt signaling is transduced through dvl-1 and PKC (Cook et al., 1996). PKC participates in the signaling of diverse cascades, including the MAP kinase pathway via MAP kinase kinase (MEK) and MEK kinase (MEKK). The JNK pathway is analogous to the MAP kinase pathway and can also be triggered by MEKK (Hirai et al., 1996) as well as by dishevelled (Boutros et al., 1998; Li et al., 1999). To determine which if any of these kinases transduces a dvl-1 signal to α-secretase, we attempted to block a dvl-1-mediated increase in sAPPα using an inhibitor of PKC (bisindolylmaleimide-I), a specific inhibitor of MEK activation (PD98059), and a specific inhibitor of p38 MAP kinase (PD169316). To block potential JNK effects, cells were cotransfected with both dvl-1 and cDNA coding for the JNK regulatory protein JIP-1 (Dickens et al., 1997). Data shown in Figure6 are normalized relative to the amount of sAPPα secreted by cells transfected with dvl-1 alone. Each experiment was repeated four times, and the proportion of sAPP secreted by cells expressing dvl-1 in the presence of kinase inhibition was expressed relative to sAPPα secreted by cells transfected with dvl-1 in the absence of kinase inhibitor in that particular experiment. The results were highly reproducible and demonstrated a >50% reduction in sAPPα after inhibition of PKC, prevention of MAP kinase activation, or inhibition of JNK signaling. In contrast, PD169316, a p38 MAP kinase inhibitor, reduced dvl-1-mediated sAPPα secretion by only 30% (not significant) (Fig. 6). In other experiments the inhibitors alone had no effect on sAPP generation (data not shown).

Fig. 6.

The dvl-1 effect on sAPPα secretion is blocked via inhibition of PKC/MAP kinase and JNK. HEK293 wtAPP695cells were transfected with dvl-1 and treated with a PKC inhibitor (bisindolylmaleimide-I), an inhibitor of MEK/MAP kinase signaling (PD98059), and an inhibitor of p38 (PD169316), and cotransfected with JIP-1, an inhibitor of JNK signaling. The secretion of sAPPα was assessed by immunoblotting (A) and measured by densitometry (B) (n = 4; error bars = SEM). Transfection of dvl-1 increased sAPPα secretion, but this increase was substantially reduced by PKC and MAP kinase signaling inhibition but unaffected by p38 MAP kinase inhibition. Inhibition of JNK signaling had a partial effect on sAPPα secretion. In all cases, densitometry data are normalized relative to controls for each individual experiment. *p < 0.05; **p = 0.005.

We then determined whether activating these pathways would increase sAPPα secretion in these cells (Fig.7). HEK293 wtAPP695cells were stimulated with TPA to activate PKC or transfected with cDNA coding for p38 kinase or for JNK-3. In results complementary to the inhibitor studies, we found that p38 MAP kinase failed to induce sAPPα secretion, whereas increases in PKC and JNK activity both significantly increased sAPP secretion more than twofold (p < 0.05).

Fig. 7.

PKC/MAP kinase and JNK increase sAPPα production. Endogenous PKC in HEK293 wtAPP695 cells was activated with phorbol ester, and the same cells were also transfected with plasmids encoding p38 MAP kinase and JNK-3. The secretion of sAPPα was assessed by immunoblotting (A) and measured by densitometry (B). Activation of PKC and transfection of JNK-3 increased sAPPα production, whereas p38 MAP kinase transfection had no effect. These results are exactly complementary to those of Figure 6 and demonstrate an effect of PKC/MAP kinase and JNK-3 on sAPPα. In all cases, densitometry data are normalized relative to controls for each individual experiment. *p < 0.05; **p = 0.005.

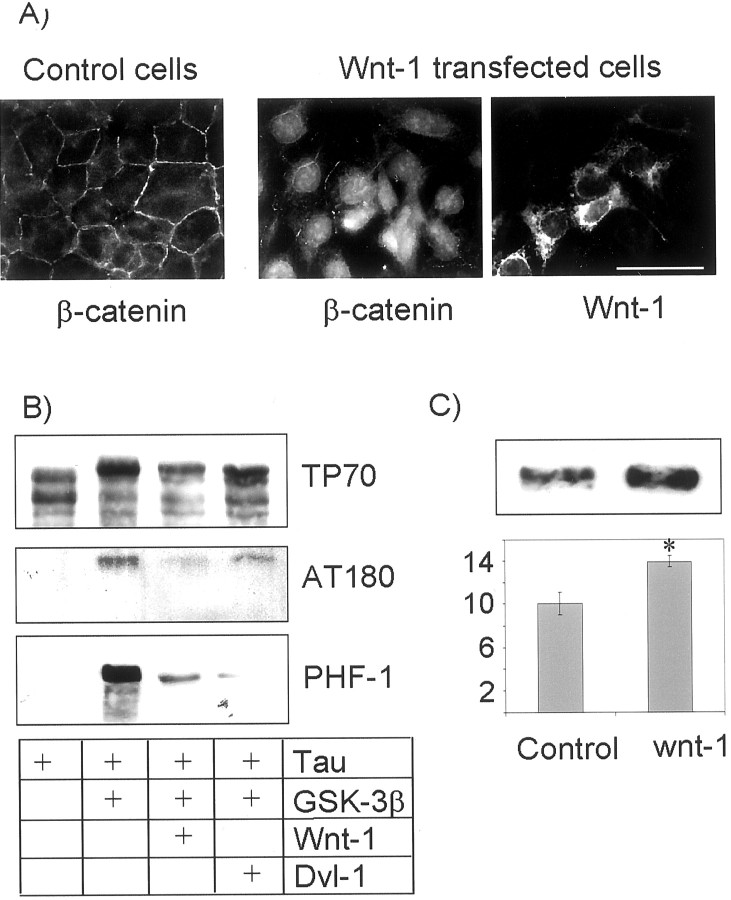

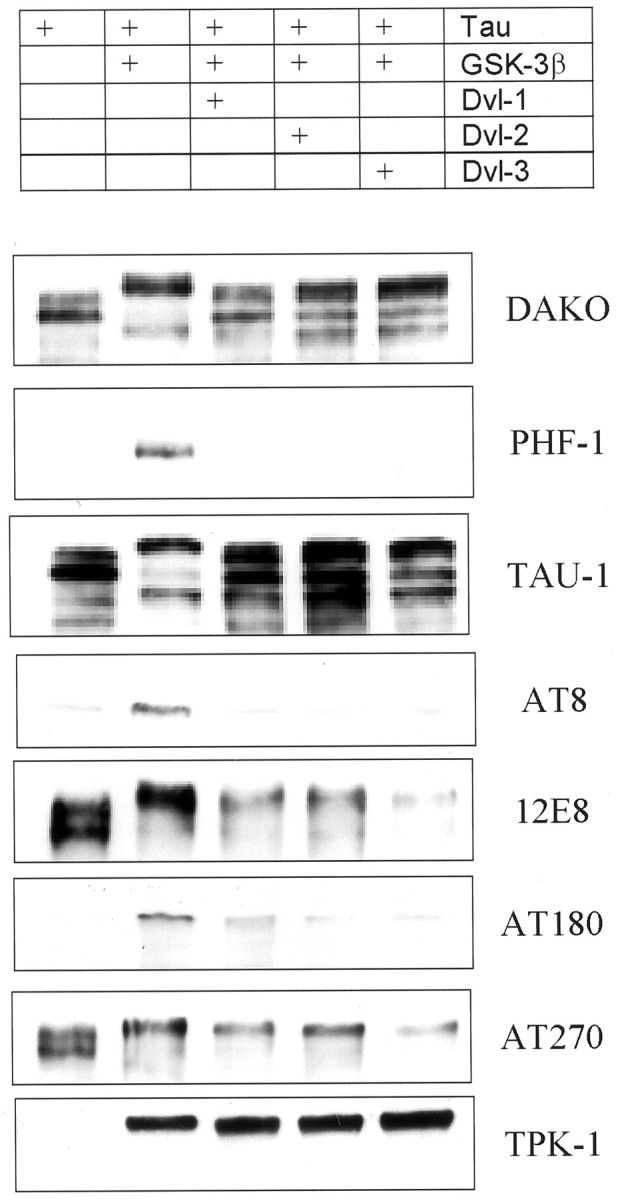

Human dishevelled reduces the phosphorylation of tau mediated by GSK-3β

Previously, murine dishevelled was shown to reduce GSK-3-mediated tau phosphorylation (Wagner et al., 1997). To establish whether human dishevelled had equivalent activity, we cotransfected cDNA coding for tau and GSK-3β into CHO cells with and without cDNA coding for human dvl-1. With use of a polyclonal phosphorylation-independent antibody (Dako Ltd., Cambridge, UK), tau expressed in CHO cells generates multiple bands representing endogenous kinase activity in these cells producing differently phosphorylated species (Fig.8). Coexpressing GSK-3β resulted in a change in electrophoretic mobility, tau now appearing predominantly as a slowly migrating band. Cotransfecting dvl-1 in addition to GSK-3β increased the electrophoretic mobility of tau to a modest extent, indicating a probable reduction in phosphorylation. This was confirmed using a panel of phosphorylation-specific monoclonal antibodies. This was most obvious with the antibody PHF-1, which recognizes an epitope of tau (Ser 406) only when highly phosphorylated. Tau expressed in CHO cells alone was not recognized by PHF-1, although it was recognized when GSK-3β was also expressed. Despite equivalent levels of GSK-3β protein (as demonstrated by the antibody TPK1), cotransfection of dishevelled together with GSK-3β and tau eliminated recognition by PHF-1. There were no obvious differences between dvl-1, -2, and -3.

Fig. 8.

Dishevelled decreases GSK-3β phosphorylation of tau. Tau was transiently expressed in CHO cells alone, together with cDNA for GSK-3β and together with both GSK-3β and dvl-1, dvl-2, or dvl-3. GSK-3β increased phosphorylation of tau as recognized by a decreased mobility on SDS-PAGE when examined using the phosphorylation-independent antibody (Dako) and a change in recognition by phosphorylation-dependent antibodies. When dvl-1, dvl-2, or dvl-3 was also expressed, tau mobility increased relative to that of GSK-3 cotransfected cells but did not return to the same pattern as tau in the absence of GSK-3. Recognition by the phosphorylation-dependent antibody PHF1 was abolished and that of the other phosphorylation antibodies markedly reduced (or in the case of TAU1, increased). Expression of GSK-3β is indicated by the antibody TPK1.

A less pronounced increase in phosphorylation of tau in cells cotransfected with GSK-3β was observed with AT8 labeling, which was reversed in cells transfected with dvl-1, -2, or -3 in addition to GSK-3 and tau. Similarly TAU1, which requires its epitope in tau [which overlaps with that of AT8 (Biernat et al., 1992; Goedert et al., 1995)] in a nonphosphorylated state, labeled tau less well in GSK-3β-transfected cells, but this effect was reversed when dvl-1, -2, and -3 were also expressed. Dishevelled cotransfection with GSK-3β also reduced, compared with GSK-3β alone, the intensity of recognition by the monoclonal antibodies 12E8, AT180, and AT270, recognizing tau phosphorylated at epitopes Ser262/356 (Seubert et al., 1995), Thr 231 (Goedert et al., 1994), and Thr 181 (Goedert et al., 1994), respectively. The effects of dishevelled in attenuating the GSK-3β-mediated increase in recognition by these antibodies was less marked than that for PHF-1, and each of the isoforms of dishevelled (dvl-1, -2, and -3) reduced the GSK-3β increase in tau phosphorylation without any striking differences between isoforms being apparent.

Wnt-1 inhibits phosphorylation of tau by GSK-3β and increases sAPP generation

Dvl-1 is activated after receipt of the wnt signal, transduced through the frizzled receptor. We therefore examined the effect of wnt-1 signaling directly on tau phosphorylation and APP processing. To generate a wnt signal, we transfected native HEK293 cells with cDNA coding for human wnt-1 and assayed the generation of wnt signaling by determining β-catenin intracellular localization by immunocytochemistry. Wnt signaling and dvl-1 activation have been shown to stabilize and induce nuclear translocation of β-catenin, the final effector of the signal (Kikuchi, 2000), and we therefore used β-catenin as an assay of wnt function (Van Gassen et al., 2000). Untransfected HEK293 cells displayed β-catenin immunoreactivity colocalizing with the cell boundary. Cultures transfected with wnt-1 showed increased cytoplasmic and nuclear β-catenin consistent with receipt of the wnt signal. Interestingly, cells expressing wnt-1 and adjacent cells both showed β-catenin nuclear translocation, consistent with wnt-1 being a secreted protein. These cells were then transfected with cDNA coding for tau alone, for tau and GSK-3β, and for tau, GSK-3β, and either wnt-1 or dvl-1. As before, dvl-1 expression reduced the intensity of the slow migrating band of tau recognized by TP70 and the phosphorylation-specific antibodies AT180 and PHF-1. Wnt-1 transfected cells showed a similar reduction indicating that wnt-1, like dvl-1, attenuated GSK-3β phosphorylation of tau. We then transfected HEK293 cells stably expressing human APP695 with cDNA coding for wnt-1 and measured sAPP secretion into the medium as before. Wnt-1 expression, like dvl expression, resulted in a 40% increase in sAPP generation [10.1 (SD 2.1) vs 14.0 (SD 0.8);n = 2; p = 0.02] (Fig.9).

Fig. 9.

Wnt signaling reduces tau phosphorylation and increases sAPPα generation. In wild-type HEK293 cells, β-catenin assumes a cell-boundary localization (A). In cells transfected with wnt-1, and in surrounding cells, the localization of β-catenin changed and became cytoplasmic and nuclear, indicating the receipt of the wnt signal by these cells. Wnt signal reduced the phosphorylation of tau by GSK-3β as demonstrated by a loss of slow migrating bands visualized with the phosphate-independent antibody TP70 and a loss of bands reactive with the phosphorylation-dependent antibodies AT180 and PHF-1 (B). This reduction in tau phosphorylation was similar to that resulting from dvl-1 transfection. Wnt-1 transfection also reduced sAPPα generation relative to vector-only transfected cells (C). *p < 0.05. Scale bar, 20 μm.

DISCUSSION

The regulation of APP metabolism has been a matter of intense scrutiny since it was demonstrated that peptides from this protein form the amyloid of the senile plaque in AD. There are at least two distinct metabolic routes whereby APP is metabolized: β- and γ-secretase cleavage together result in the peptide that is deposited in plaques, whereas most secreted sAPP is generated by α-secretase. The β-secretase has been isolated [β-site APP-cleaving enzyme (BACE)] (Hussain et al., 1999; Sinha et al., 1999; Vassar et al., 1999; Yan et al., 1999), and some evidence has suggested that α-secretase is a member of the ADAMs (a disintigrin and metalloprotease) family (Parvathy et al., 1998; Hooper et al., 1999; Lammich et al., 1999;Racchi et al., 1999). We now demonstrate that dishevelled increases the generation of α-secretase-cleaved APP because dvl-1, -2, and -3 all increase sAPPα secretion into the medium both significantly and substantially. The magnitude of the increase in sAPPα appears similar to that induced by activation of PKC. However, in the model that we have used, dishevelled is expressed in only a proportion of cells (∼30%), whereas the activation of PKC applies to all cells. Therefore, the effect of dishevelled on individual cells must be considerably greater than that of PKC alone. The increase in sAPPα after dvl-1 expression is caused by increased release of α-secretase-cleaved APP and not increased release of β-secretase-cleaved APP, as shown by immunoblotting using antibodies specific to sAPPα and sAPPβ. Neither can the finding be attributed to an increased expression of total APP because the amount of APP associated with the cells did not change after expression of dvl-1.

Moreover, the observation that sAPPα was increased in cell lines bearing the Swedish mutation in APP points toward increased α-secretase activity rather than increased secretion of sAPPα. This mutation increases β-secretase at the expense of α-secretase, thereby increasing the generation of Aβ. The observation that increased sAPP secretion after dvl-1 transfection is caused by sAPPα and not sAPPβ, together with the observation that the generation of Aβ was unaffected, strongly suggests that dvl-1 action is to increase α-secretase cleavage of APP rather than simply to increase secretion of α- or β-secretase-cleaved APP, in which case an increase in sAPPβ would have been expected in APPswe cells.

It is unlikely that dishevelled regulates the activity of α-secretase directly but instead regulates the activity via a signaling pathway. It is known that dishevelled activates JNK (Boutros et al., 1998; Li et al., 1999), and our results indicate that signaling through this route is partially responsible for the effect of dvl-1 on APP. The dvl-1-mediated increase in sAPPα was blocked by inhibition of JNK, and conversely, increased JNK activity mimicked the effects of dvl-1. To our knowledge this is the first demonstration of an effect of JNK on APP processing, although JNK-3 has recently been shown to phosphorylate APP (Standen et al., 2001). However, this is not the only route whereby dvl-1 regulates production of α-secretase-cleaved sAPP. Inhibitors of both PKC and MAP kinase signaling blocked the dvl-1-mediated increase in sAPPα, and increased PKC activity increased sAPPα. These findings are in line with previous studies demonstrating that α-secretase activity is regulated via both PKC and MAP kinase in addition to other pathways not yet characterized (Racchi et al., 1999).

Our findings are also compatible with previous findings in relation to dishevelled signaling. Genetic experiments suggested that theDrosophila dishevelled, dsh, is an upstream activator of JNK (Strutt et al., 1997; Boutros et al., 1998), and transfection of dsh and mouse dvl resulted in increased phosphorylation of JNK (Boutros et al., 1998; Li et al., 1999). However, not all dishevelled signaling is via JNK, and mutations in dsh can uncouple signaling to JNK and to β-catenin (Li et al., 1999). Two lines of evidence have implicated PKC in dishevelled signaling. The wingless signal is transduced through dishevelled, a process that involves phosphorylation of dvl (Yanagawa et al., 1995; Axelrod et al., 1996, 1998; Steitz et al., 1996). Wingless signaling involves PKC (Cook et al., 1996) and as Lee et al. (1999) point out, a PKC-binding protein, RACK8, is highly homologous, if not identical to human dvl-3. Because CaMKII is upstream of dishevelled (Lee et al., 1999), this suggested that PKC was downstream of dishevelled, and we have now provided the first biochemical evidence for this because dvl-1-mediated sAPPα was blocked by PKC inhibition.

Our results cannot be explained by a nonspecific effect of dvl-1 on sAPPα because we were able to exclude a role for p38 MAP kinase. We were also able to exclude GSK-3β from the pathway from dvl-1 to APP. GSK-3β is a key target of wingless signaling, and both wnt and dvl-1 have been shown to inhibit GSK-3β (Diaz-Benjumea and Cohen, 1994;Dominguez et al., 1995; Hedgepeth et al., 1997; Papkoff and Aikawa, 1998); we initially expected GSK-3β to be involved in the dvl-1-mediated increase in sAPPα. APP can be directly phosphorylated by GSK-3β (Aplin et al., 1996), and when this happens the cellular maturation of APP is altered (Aplin et al., 1997). Lithium is a relatively specific inhibitor of GSK-3β (Klein and Melton, 1996;Stambolic et al., 1996) and would be expected to increase sAPPα if the dvl-1 effect were mediated via GSK-3β. However, we observed no effects of lithium on sAPP release from cells, and conversely overexpression of GSK-3β failed to reduce sAPPα production.

Although GSK-3β does not alter sAPPα production, the fact that dvl-1 increases sAPPα and inhibits GSK-3β suggests that dishevelled might be the point through which the two pathological processes of AD are linked. In AD, neurofibrillary tangles composed largely of highly phosphorylated tau accumulate in neurons, whereas plaques are deposited extracellularly. Both lesions are invariable features of AD, and the amyloid cascade hypothesis postulates that one (amyloid) precedes another (tangles). However, although animal models generate amyloid deposition, they have not demonstrated significant accumulation of highly phosphorylated tau. One variation of the amyloid cascade hypothesis would be that some common factor influences both lesions. We now report that human dvl-1 decreases GSK-3β phosphorylation of tau, extending previous findings by demonstrating that this reduction is at multiple epitopes. Previously, GSK-3β phosphorylation of tau was shown to alter the properties of tau, reducing its ability to bind to and stabilize microtubules (Lovestone et al., 1996). Most recently, murine dvl-1 has been shown to stabilize microtubules (Krylova et al., 2000). Therefore dvl-1 acts as a counterbalance to GSK-3β, reducing tau phosphorylation and enhancing stability of microtubules.

Dishevelled acts as a convergence point between wnt signaling and Notch signaling (Axelrod et al., 1996), both processes having been implicated in AD pathogenesis through the presenilins. Thus PS-1 binds components of the wnt signaling cascade, including both GSK-3β and β-catenin, and alters β-catenin signaling (Takashima et al., 1998; Kang et al., 1999). Presenilins also regulate the processing of Notch in a manner analogous to regulation of APP processing, a function altered by the familial AD mutations in PS-1 (Jarriault et al., 1995; Chan and Jan, 1999). Our finding suggests the scheme shown in Figure10, whereby dishevelled, previously shown to be a common point between Notch and wnt/wingless signaling (Axelrod et al., 1996), has now been demonstrated to be upstream of both APP metabolism and tau phosphorylation. PS-1 interacts with both Notch and wingless signaling, independently inhibiting wnt signaling and stimulating Notch activation (Soriano et al., 2001). De Strooper and Annaert note that Notch and wnt signaling are mutually inhibitory on at least three levels: PS-1 as noted above and Notch extracellular domain binding to wnt and at the level of dvl-1. Our results suggest that dvl might function to link tau phosphorylation with these signaling pathways. It is noteworthy that the effects of dvl on the cell are likely to be synergistic in that increasing evidence, although not fully understood, suggests that sAPPα has an important role in synaptic plasticity or in neuroprotection (Seabrook et al., 1999). Similarly tau plays an important role in promoting stability of the neuronal cytoskeleton, and this function is modified by the mutations that cause frontal lobe dementias or by GSK-3β phosphorylation or by dvl-1 (Hong and Lee, 1997; Dayanandan et al., 1999; Krylova et al., 2000). Dishevelled therefore increases the neuroprotective sAPPα and enhances the neuronal stabilizing properties of tau. This is in line with the previous observation that Aβ toxicity in neurons is reduced by lithium, which, like dvl-1, inhibits GSK-3 (Alvarez et al., 1999).

Fig. 10.

Dishevelled signaling increases sAPPα and decreases tau phosphorylation. Dishevelled has previously been shown to mediate wnt signaling and may be at an intersection between notch and wnt signaling. The demonstration that dvl-1 and wnt-1 alter both APP metabolism and tau phosphorylation suggests that wnt signaling has a role in both of the key processes involved in AD pathology.

In summary, we have demonstrated that dishevelled regulates α-secretase cleavage of APP, generating a more than twofold increase in the amount of sAPPα secreted by cells. This effect is mediated by JNK, PKC, and MAP kinase acting either in concert or independently. Dishevelled also inhibits GSK-3β, reducing the phosphorylation of tau in the process, although GSK-3β activity has no bearing on sAPPα release. However, the fact that dishevelled mediates an increase in the production of the neuroprotective sAPPα and a decrease in the phosphorylation of tau links two processes, both of which have been shown previously to be protective of neuronal structure and function and both of which are important in AD pathogenesis.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Medical Research Council (LINK project NoG963007), Research into Aging, and the Wellcome Trust. We thank Chris Plumpton (Glaxo R&D) for the G26 antisera.

A.M. and S.C. contributed equally to this work.

Correspondence should be addressed to Simon Lovestone, Institute of Psychiatry, King's College London, De Crespigny Park, London, SE5 8AF, UK. E-mail: s.lovestone@iop.kcl.ac.uk.

L. Raymond's present address: Department of Medical Genetics, Cambridge Institute of Medical Research, Addenbrooke‘s Hospital, Cambridge CB2 2XY, UK.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alessi DR, Cuenda A, Cohen P, Dudley DT, Saltiel AR. PD 098059 is a specific inhibitor of the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:27489–27494. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.46.27489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvarez G, Muñoz-Montaño JR, Satrústegui J, Avila J, Bogónez E, Díaz-Nido J. Lithium protects cultured neurons against β-amyloid-induced neurodegeneration. FEBS Lett. 1999;453:260–264. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00685-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderton BH, Dayanandan I, Killick I, Lovestone S. Does dysregulation of the notch and wingless/Wnt pathways underlie the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease? Mol Med Today. 2000;6:54–59. doi: 10.1016/s1357-4310(99)01640-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aplin AE, Gibb GM, Jacobsen JS, Gallo JM, Anderton BH. In vitro phosphorylation of the cytoplasmic domain of the amyloid precursor protein by glycogen synthase kinase-3β. J Neurochem. 1996;67:699–707. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.67020699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aplin AE, Jacobsen JS, Anderton BH, Gallo JM. Effect of increased glycogen synthase kinase-3 activity upon the maturation of the amyloid precursor protein in transfected cells. NeuroReport. 1997;8:639–643. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199702100-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Axelrod JD, Matsuno K, Artavanis-Tsakonas S, Perrimon N. Interaction between wingless and notch signaling pathways mediated by dishevelled. Science. 1996;271:1826–1832. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5257.1826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Axelrod JD, Miller JR, Shulman JM, Moon RT, Perrimon N. Differential recruitment of Dishevelled provides signaling specificity in the planar cell polarity and Wingless signaling pathways. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2610–2622. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.16.2610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biernat J, Mandelkow EM, Schroter C, Lichtenberg Kraag B, Steiner B, Berling B, Meyer H, Mercken M, Vandermeeren A, Goedert M. The switch of tau protein to an Alzheimer-like state includes the phosphorylation of two serine-proline motifs upstream of the microtubule binding region. EMBO J. 1992;11:1593–1597. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05204.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borchelt DR, Thinakaran G, Eckman CB, Lee MK, Davenport F, Ratovitsky T, Prada CM, Kim G, Seekins S, Yager D, Slunt HH, Wang R, Seeger M, Levey AI, Gandy SE, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Price DL, Younkin SG. Familial Alzheimer's disease-linked presenilin 1 variants elevate Aβ 1–42/1–40 ratio in vitro and in vivo. Neuron. 1996;17:1005–1013. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80230-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boutros M, Paricio N, Strutt DI, Mlodzik M. Dishevelled activates JNK and discriminates between JNK pathways in planar polarity and wingless signaling. Cell. 1998;94:109–118. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81226-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buxbaum JD, Koo EH, Greengard P. Protein phosphorylation inhibits production of Alzheimer amyloid β/A4 peptide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:9195–9198. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.19.9195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan YM, Jan YN. Presenilins, processing of β-amyloid precursor protein, and Notch signaling. Neuron. 1999;23:201–204. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80771-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cook D, Fry MJ, Hughes K, Sumathipala R, Woodgett J, Dale TC. Wingless inactivates glycogen synthase kinase-3 via an intracellular signaling pathway which involves a protein kinase. EMBO J. 1996;15:4526–4536. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dayanandan R, Van Slegtenhorst M, Mack TG, Ko L, Yen SH, Leroy K, Brion JP, Anderton BH, Hutton M, Lovestone S. Mutations in tau reduce its microtubule binding properties in intact cells and affect its phosphorylation. FEBS Lett. 1999;446:228–232. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00222-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Strooper B, Saftig P, Craessaerts K, Vanderstichele H, Guhde G, Annaert W, Von Figura K, Van Leuven F. Deficiency of presenilin-1 inhibits the normal cleavage of amyloid precursor protein. Nature. 1998;391:387–390. doi: 10.1038/34910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diaz-Benjumea FJ, Cohen SM. wingless acts through the shaggy/zeste-white 3 kinase to direct dorsal-ventral axis formation in the Drosophila leg. Development. 1994;120:1661–1670. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.6.1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dickens M, Rogers JS, Cavanagh J, Raitano A, Xia Z, Halpern JR, Greenberg ME, Sawyers CL, Davis RJ. A cytoplasmic inhibitor of the JNK signal transduction pathway. Science. 1997;277:693–696. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5326.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dominguez I, Itoh K, Sokol SY. Role of glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta as a negative regulator of dorsoventral axis formation in Xenopus embryos. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:8498–8502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dyrks T, Mönning U, Beyreuther K, Turner J. Amyloid precursor protein secretion and βA4 amyloid generation are not mutually exclusive. FEBS Lett. 1994;349:210–214. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00671-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gabuzda D, Busciglio J, Yankner BA. Inhibition of β-amyloid production by activation of protein kinase C. J Neurochem. 1993;61:2326–2329. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb07479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goedert M, Jakes R, Crowther RA, Cohen P, Vanmechelen E, Vandermeeren M, Cras P. Epitope mapping of monoclonal antibodies to the paired helical filaments of Alzheimer's disease: identification of phosphorylation sites in tau protein. Biochem J. 1994;301:871–877. doi: 10.1042/bj3010871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goedert M, Jakes R, Vanmechelen E. Monoclonal antibody AT8 recognises tau protein phosphorylated at both serine 202 and threonine 205. Neurosci Lett. 1995;189:167–170. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11484-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goode N, Hughes K, Woodgett JR, Parker PJ. Differential regulation of glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta by protein kinase C isotypes. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:16878–16882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haass C, Lemere CA, Capell A, Citron M, Seubert P, Schenk D, Lannfelt L, Selkoe DJ. The Swedish mutation causes early-onset Alzheimer's disease by β-secretase cleavage within the secretory pathway. Nat Med. 1995;1:1291–1296. doi: 10.1038/nm1295-1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hardy JA, Higgins GA. Alzheimer's disease: the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Science. 1992;256:184–185. doi: 10.1126/science.1566067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haring R, Fisher A, Marciano D, Pittel Z, Kloog Y, Zuckerman A, Eshhar N, Heldman E. Mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent and protein kinase C-dependent pathways link the m1 muscarinic receptor to β-amyloid precursor protein secretion. J Neurochem. 1998;71:2094–2103. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71052094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hedgepeth CM, Conrad LJ, Zhang J, Huang HC, Lee VMY, Klein PS. Activation of the wnt signaling pathway: a molecular mechanism for lithium action. Dev Biol. 1997;185:82–91. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hirai S, Izawa M, Osada S, Spyrou G, Ohno S. Activation of the JNK pathway by distantly related protein kinases, MEKK and MUK. Oncogene. 1996;12:641–650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hong M, Lee VMY. Insulin and insulin-like growth factor-1 regulate tau phosphorylation in cultured human neurons. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:19547–19553. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.31.19547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hooper NM, Parvathy S, Karran EH, Turner AJ. Angiotensin-converting enzyme and the amyloid precursor protein secretases. Biochem Soc Trans. 1999;27:229–234. doi: 10.1042/bst0270229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hung AY, Haass C, Nitsch RM, Qiao Qiu W, Citron M, Wurtman RJ, Growdon JH, Selkoe DJ. Activation of protein kinase C inhibits cellular production of the amyloid β-protein. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:22959–22962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hussain I, Powell DJ, Howlett DR, Tew DG, Week TD, Chapman C, Gloger IS, Murphy KE, Southan CD, Ryan DM, Smith TS, Simmons DL, Walsh FS, Dingwall C, Christie G. Identification of a novel aspartic protease (Asp 2) as β-secretase. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1999;14:419–427. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1999.0811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jarriault S, Brou C, Logeat F, Schroeter EH, Kopan R, Israel A. Signalling downstream of activated mammalian Notch. Nature. 1995;377:355–358. doi: 10.1038/377355a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kang DE, Soriano S, Frosch MP, Collins T, Naruse S, Sisodia SS, Leibowitz G, Levine F, Koo EH. Presnelin 1 facilitates the constitutive turnover of β-catenin: differential activity of Alzheimer's disease-linked PS1 mutants in the β-catenin-signaling pathway. J Neurosci. 1999;19:4229–4237. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-11-04229.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kikuchi A. Regulation of β-catenin signaling in the Wnt pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;268:243–248. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klein PS, Melton DA. A molecular mechanism for the effect of lithium on development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:8455–8459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krylova O, Messenger MJ, Salinas PC. Dishevelled-1 regulates microtubule stability. A new function mediated by glycogen synthase kinase-3beta. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:83–94. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lammich S, Kojro E, Postina R, Gilbert S, Pfeiffer R, Jasionowski M, Haass C, Fahrenholz F. Constitutive and regulated alpha-secretase cleavage of Alzheimer's amyloid precursor protein by a disintegrin metalloprotease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:3922–3927. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.LeBlanc AC, Koutroumanis M, Goodyer CG. Protein kinase C activation increases release of secreted amyloid precursor protein without decreasing Aβ production in human primary neuron cultures. J Neurosci. 1998;18:2907–2913. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-08-02907.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee JS, Ishimoto A, Yanagawa S. Characterization of mouse dishevelled (Dvl) proteins in Wnt/Wingless signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:21464–21470. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.30.21464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li L, Yuan HD, Xie W, Mao JH, Caruso AM, McMahon A, Sussman DJ, Wu DQ. Dishevelled proteins lead to two signaling pathways. Regulation of LEF-1 and c-Jun N-terminal kinase in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:129–134. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lovestone S, Reynolds CH, Latimer D, Davis DR, Anderton BH, Gallo J-M, Hanger D, Mulot S, Marquardt B, Stabel S, Woodgett JR, Miller CCJ. Alzheimer's disease-like phosphorylation of the microtubule-associated protein tau by glycogen synthase kinase-3 in transfected mammalian cells. Curr Biol. 1994;4:1077–1086. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00246-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lovestone S, Hartley CL, Pearce J, Anderton BH. Phosphorylation of tau by glycogen synthase kinase-3β in intact mammalian cells: the effects on organisation and stability of microtubules. Neuroscience. 1996;73:1145–1157. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00126-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mills J, Reiner PB. Regulation of amyloid precursor protein cleavage. J Neurochem. 1999;72:443–460. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0720443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Murphy MP, Hickman LJ, Eckman CB, Uljon SN, Wang R, Golde TE. gamma-Secretase, evidence for multiple proteolytic activities and influence of membrane positioning of substrate on generation of amyloid beta peptides of varying length. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:11914–11923. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.17.11914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Naylor S, Smalley MJ, Robertson D, Gusterson BA, Edwards PA, Dale TC. Retroviral expression of Wnt-1 and Wnt-7b produces different effects in mouse mammary epithelium. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:2129–2138. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.12.2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nitsch RM, Slack BE, Wurtman RJ, Growdon JH. Release of Alzheimer amyloid precursor derivatives stimulated by activation of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. Science. 1992;258:304–307. doi: 10.1126/science.1411529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Papkoff J, Aikawa M. WNT-1 and HGF regulate GSK3β activity and β-catenin signaling in mammary epithelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;247:851–858. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Parvathy S, Hussain I, Karran EH, Turner AJ, Hooper NM. The amyloid precursor protein (APP) and the angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) secretase are inhibited by hydroxamic acid-based inhibitors. Biochem Soc Trans. 1998;26:S242. doi: 10.1042/bst026s242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Racchi M, Solano DC, Sironi M, Govoni S. Activity of α-secretase as the common final effector of protein kinase C-dependent and -independent modulation of amyloid precursor protein metabolism. J Neurochem. 1999;72:2464–2470. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0722464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Savage MJ, Trusko SP, Howland DS, Pinsker LR, Mistretta S, Reaume AG, Greenberg BD, Siman R, Scott RW. Turnover of amyloid β-protein in mouse brain and acute reduction of its level by phorbol ester. J Neurosci. 1998;18:1743–1752. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-05-01743.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Scheuner D, Eckman C, Jensen M, Song X, Citron M, Suzuki N, Bird TD, Hardy J, Hutton M, Kukull W, Larson E, Levy-Lahad E, Viitanen M, Peskind E, Poorkaj P, Schellenberg G, Tanzi R, Wasco W, Lannfelt L, Selkoe D, Younkin S. Secreted amyloid β-protein similar to that in the senile plaques of Alzheimer's disease is increased in vivo by the presenilin 1 and 2 and APP mutations linked to familial Alzheimer's disease. Nat Med. 1996;2:864–870. doi: 10.1038/nm0896-864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Seabrook GR, Smith DW, Bowery BJ, Easter A, Reynolds T, Fitzjohn SM, Morton RA, Zheng H, Dawson GR, Sirinathsinghji DJS, Davies CH, Collingridge GL, Hill RG. Mechanisms contributing to the deficits in hippocampal synaptic plasticity in mice lacking amyloid precursor protein. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38:349–359. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(98)00204-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Seubert P, Mawal-Dewan M, Barbour R, Jakes R, Goedert M, Johnson GVW, Litersky JM, Schenk D, Lieberburg I, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VMY. Detection of phosphorylated Ser262 in fetal tau, adult tau, and paired helical filament tau. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:18917–18922. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.32.18917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sinha S, Anderson JP, Barbour R, Basi GS, Caccavello R, Davis D, Doan M, Dovey HF, Frigon N, Hong J, Jacobson-Croak K, Jewett N, Keim P, Knops J, Lieberburg I, Power M, Tan H, Tatsuno G, Tung J, Schenk D, Seubert P, Suomensaari SM, Wang SW, Walker D. Purification and cloning of amyloid precursor protein β-secretase from human brain. Nature. 1999;402:537–540. doi: 10.1038/990114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Slack BE, Nitsch RM, Livneh E, Kunz GM, Jr, Breu J, Eldar H, Wurtman RJ. Regulation by phorbol esters of amyloid precursor protein release from Swiss 3T3 fibroblasts overexpressing protein kinase C α. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:21097–21101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Soriano S, Kang DE, Fu M, Pestell R, Chevallier N, Zheng H, Koo EH. Presenilin 1 negatively regulates beta-catenin/T cell factor/lymphoid enhancer factor-1 signaling independently of beta-amyloid precursor protein and notch processing. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:785–794. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.4.785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stambolic V, Ruel L, Woodgett JR. Lithium inhibits glycogen synthase kinase-3 activity and mimics wingless signalling in intact cells. Curr Biol. 1996;6:1664–1668. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)70790-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Standen CL, Brownlees J, Grierson AJ, Kesavapany S, Lau KF, McLoughlin DM, Miller CC. Phosphorylation of Thr(668) in the cytoplasmic domain of the Alzheimer's disease amyloid precursor protein by stress-activated protein kinase 1b (Jun N-terminal kinase-3). J Neurochem. 2001;76:316–320. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Steitz SA, Tsang M, Sussman DJ. Wnt-mediated relocalization of dishevelled proteins. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 1996;32:441–445. doi: 10.1007/BF02723007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Strutt DI, Weber U, Mlodzik M. The role of RhoA in tissue polarity and Frizzled signalling. Nature. 1997;387:292–295. doi: 10.1038/387292a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Takashima A, Murayama M, Murayama O, Kohno T, Honda T, Yasutake K, Nihonmatsu N, Mercken M, Yamaguchi H, Sugihara S, Wolozin B. Presenilin 1 associates with glycogen synthase kinase-3β and its substrate tau. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9637–9641. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Thinakaran G, Teplow DB, Siman R, Greenberg B, Sisodia SS. Metabolism of the “Swedish” amyloid precursor protein variant in neuro2a (N2a) cells. Evidence that cleavage at the “β-secretase” site occurs in the Golgi apparatus. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:9390–9397. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.16.9390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Van Gassen G, De Jonghe C, Nishimura M, Yu G, Kuhn S, George-Hyslop P, Van Broeckhoven C. Evidence that the beta-catenin nuclear translocation assay allows for measuring presenilin 1 dysfunction. Mol Med. 2000;6:570–580. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vassar R, Bennett BD, Babu-Khan S, Kahn S, Mendiaz EA, Denis P, Teplow DB, Ross S, Amarante P, Loeloff R, Luo Y, Fisher S, Fuller J, Edenson S, Lile J, Jarosinski MA, Biere AL, Curran E, Burgess T, Louis JC, Collins F, Treanor J, Rogers G, Citron M. Beta-secretase cleavage of Alzheimer's amyloid precursor protein by the transmembrane aspartic protease BACE. Science. 1999;286:735–741. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5440.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wagner U, Brownlees J, Irving NG, Lucas FR, Salinas PC, Miller CCJ. Overexpression of the mouse dishevelled-1 protein inhibits GSK-3β-mediated phosphorylation of tau in transfected mammalian cells. FEBS Lett. 1997;411:369–372. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00733-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wolfe MS, Xia W, Ostaszewski BL, Diehl TS, Kimberly WT, Selkoe DJ. Two transmembrane aspartates in presenilin-1 required for presenilin endoproteolysis and gamma-secretase activity. Nature. 1999;398:513–517. doi: 10.1038/19077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yan RQ, Bienkowski MJ, Shuck ME, Miao HY, Tory MC, Pauley AM, Brashler JR, Stratman NC, Mathews WR, Buhl AE, Carter DB, Tomasselli AG, Parodi LA, Heinrikson RL, Gurney ME. Membrane-anchored aspartyl protease with Alzheimer's disease β-secretase activity. Nature. 1999;402:533–537. doi: 10.1038/990107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yanagawa S, van Leeuwen F, Wodarz A, Klingensmith J, Nusse R. The dishevelled protein is modified by wingless signaling in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1087–1097. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.9.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]