Abstract

The present study was designed to explore the relationship between the cannabinoid and opioid receptors in animal models of opioid-induced reinforcement. The acute administration of SR141716A, a selective central cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonist, blocked heroin self-administration in rats, as well as morphine-induced place preference and morphine self-administration in mice. Morphine-dependent animals injected with SR141716A exhibited a partial opiate-like withdrawal syndrome that had limited consequences on operant responses for food and induced place aversion. These effects were associated with morphine-induced changes in the expression of CB1 receptor mRNA in specific nuclei of the reward circuit, including dorsal caudate putamen, nucleus accumbens, and septum. Additionally, the opioid antagonist naloxone precipitated a mild cannabinoid-like withdrawal syndrome in cannabinoid-dependent rats and blocked cannabinoid self-administration in mice. Neither SR141716A nor naloxone produced any intrinsic effect on these behavioral models. The present results show the existence of a cross-interaction between opioid and cannabinoid systems in behavioral responses related to addiction and open new strategies for the treatment of opiate dependence.

Keywords: addiction, cannabinoid, drug abuse, opioid, rat, mice, self-administration

Converging research findings have provided evidence for the existence of a functional interaction between the endogenous brain cannabinoid system and the endogenous opioid system (Hine et al., 1975; Vela et al., 1995; Pugh et al., 1997; Tanda et al., 1997; Manzanares et al., 1999; Valverde et al., 2000). The former is the pharmacological target of the psychoactive compounds of marijuana (Felder and Glass, 1998). It is composed by the cannabinoid CB1 receptor (Devane et al., 1988; Matsuda et al., 1993), several endogenous lipid transmitters, including anandamide (Devane et al., 1992) and 2-archidonyl glycerol (Mechoulam et al., 1995; Stella et al., 1997). The CB1 receptor has been proposed as the receptor responsible for the reinforcing properties of cannabinoids (Martellota et al., 1998; Ledent et al., 1999; Tanda et al., 1997, 2000). On the other hand, the opioid system (which includes several families of related neuropeptides and the opioid receptors) is activated by the opiate morphine and several semisynthetic opioids (heroin, methadone) that act through specific interactions with μ, δ, and κ opioid receptors (Akil, 1984; Thompson et al., 1993; Mansour et al., 1995). Among them, the μ receptor has been identified as the major contributor to opiate dependence (Matthes et al., 1996; Kieffer, 1999). When comparing μ, δ, κ, and CB1 receptors, clearly they exhibit overlapping neuroanatomical distribution, convergent neurochemical mechanisms, and comparable functional neurobiological properties: (1) opioid peptides and receptors have a similar neuroanatomical presence than cannabinoid receptors in the different structures of the reward circuitry, including dorsal caudate putamen, ventral striatum, septal nuclei, and the amygdaloid complex. (Herkenham et al., 1991; Matsuda et al., 1993; Delfs et al., 1994; Mansour et al., 1995; Navarro et al., 1998; Mason et al., 1999), (2) opioid and cannabinoid receptors are members of the G-protein-coupled family of receptors for neurotransmitters (Matsuda et al., 1990; Kieffer, 1999), and they modulate similar transduction systems, including the cAMP–protein kinase A cascade, inward rectifier K+channels, and voltage-dependent Ca2+channels (Howlett, 1995; Reisine et al., 1996; Hutcheson et al., 1998), (3) last, opioid and cannabinoid signaling systems are implicated in the regulation of common physiological processes such as nociception, motor behavior, or reward (Akil, 1984; Pugh et al., 1997;Gardner and Vorel, 1998; Manzanares et al., 1999). The existence of a functional cross-talk between both systems is supported also by pharmacological analysis confirming the existence of a cooperation between opioids and cannabinoids in analgesia and tolerance–dependence phenomena (Hine et al., 1975; Welch et al., 1992; Vela et al., 1995;Ledent et al., 1999; Navarro et al., 1998; Manzanares et al., 1999; Mason et al., 1999; M. Martin et al., 2000). Theoretically, these functional interactions might be potentially useful for the development of therapeutic strategies for opiate and marijuana addiction, following the rationale that led to the use of opioid antagonists (i.e., naltrexone) for the treatment of ethanol abuse (Volpicelli et al., 1992). The present study was designed to test this hypothesis in animal models (nongenetically-modified rodents) by (1) analyzing the effects of the CB1 cannabinoid receptor antagonist SR 141716A in opiate self-administration and opiate-induced place preference in rats and mice and (2) evaluating the actions of the opiate antagonist naloxone in both cannabinoid-dependent rats and in cannabinoid self-administration in mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals. Male Wistar rats obtained from Charles River Laboratory (Hollister, CA) (La Jolla experiments), or through Panlab (Barcelona, Spain) (Madrid experiments) were used in the present studies. Body weights were 200–250 gm on arrival and reached ∼300–400 gm at the time of testing. The rats were housed two per cage with food and water available ad libitum (except for limited access to either food or water as required). Lights were on a 12 hr light/dark cycle with lights on at 6:00 A.M. Naive CD1 mice (Panlab; Harlan, Nossan, Italy) weighing 20–22 gm were used in all the experiments. They were housed six per cage and acclimatized to laboratory conditions for at least 1 week before use.

All animal procedures met the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health detailed in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and the European Communities directive 86/609/EEC regulating animal research.

Opiate self-administration in rats and mice. Rats were trained to lever press for food (one 0.45 mg food pellet; Bio-Serve, Frenchtown, NJ) on a fixed ratio 1 (FR1) schedule of reinforcement, while food was restricted to 20 gm of chow per rat per day. Once stable responding was achieved, animals were divided into two groups. The first group (n = 9) was trained to acquire an FR5, time-out 2 min schedule of food reinforcement and was given a limited access to food for the rest of the experiment. When a stable baseline was achieved, they were used for studying the effects of acute administration of the CB1 receptor antagonist SR 141716A (a gift from Sanofi, Montpellier, France). To this end, the animals received intraperitoneal injections of either saline or the cannabinoid antagonist (0, 0.03. 0.3, and 3 mg/kg) in a Latin square design manner, either 60 min before or immediately before the testing session. Baseline sessions were intercalated between testing sessions for assessing carryover effects. The second group (n = 30) was deeply anesthetized under halothane (1.0–1.5%) and implanted with chronic indwelling catheters in the jugular vein, as previously described (Caine et al., 1993). After a postoperative recovery period of 7 d, animals were trained to self-administer heroin on a daily basis (Carrera et al., 1999) using standard 240 min sessions on a heroin dose of 0.06 mg/kg per infusion. In all self-administration sessions a lever press resulted in an intravenous infusion of a 100 μl solution of heroin dissolved in saline. A white cue light above the lever indicated delivery of a heroin infusion and remained lit for a 20 sec time-out period, during which responses were recorded but not reinforced. All operant sessions were conducted during the animals' dark cycles. The daily sessions for all the studies continued until the total number of heroin infusions per session stabilized to within ±10% for 3 consecutive days. Trained rats were used for evaluating the effects of SR 141716A (0, 0.03, 0.3, and 3 mg/kg, i.p.) on heroin self-administration in a Latin square design. Each rat received one dose per day. Heroin self-administration sessions included a pretreatment of subcutaneous saline (1.0 ml/kg body weight) 25 min into a session, and an intraperitoneal dose of SR 141716A 30 min after saline, 55 min into a session. Immediately after each injection the lever was retracted for 5 min to avoid self-injections before the onset of drug effect. Dose effects were evaluated 5 min after injection for 180 min. Somatic signs of withdrawal after the administration of SR141716A were rated for 10 min as described below. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA using a within-subject design, with two-factor design vehicle (saline injection) and SR 141716A dose (0, 0.03, 0.1, 0.3, 3 mg/kg). Subsequent individual mean comparisons were conducted with the Newman–Keuls a posteriori test.

Self-administration of morphine, naloxone, SR141716A, WIN 55,212–2, HU-210, and CP 55,940 in CD1 mice was performed as described (Martellota et al., 1998). Animals were tested in pairs in identical test cages. Each test cage presented a frontal hole provided with an infrared detector that activated a cumulative recorder and operated a syringe pump to deliver solution contingent on a nose poke response. A rear vertical chink was made on the opposite wall through which the tail was extended outside the box and secured to a horizontal surface allowing access to tail veins with a 27 gm winged needle, connected to a syringe through a Teflon tubing. Each nose poke of the active mouse resulted in a contingent injection of 1.0 μl of either vehicle or drug solution both to the active and yoked passive mouse. Nose pokes of the yoked controls were counted but had no programmed consequences. Pairs of animals were selected on the basis of approximately equal levels of nose poking during pretest and randomly allocated to the different experimental groups. Each mouse was used in only one 60 min self-administration session.

Conditioned place preference in rats and mice.Place-conditioning studies were performed using male Wistar rats, tested in a Y-maze with three chambers of the same size interconnected by a common central passage, as previously described (Rodríguez de Fonseca et al., 1995; Chaperon et al., 1998). Two groups of animals were tested. The first experiment (n = 10–12per group) studied the effects of intraperitoneal injections of saline (unpaired compartment) or SR141716A (0, 0.1, 0.3 and 3 mg/kg, paired compartment), administered immediately before placing the animal in the conditioning chambers. A preconditioning session was performed on day 0 for establishing the initial preferences of the animals. Six conditioning sessions (one per day) were performed thereon, on which days 1, 3, and 5 were used for the injection of SR141716A, whereas days 2, 4, and 6 for used for saline pairings. Testing session was performed on day seven and lasted 30 min. The second experiment was performed in male rats implanted with either a placebo or a morphine pellet as described above. Seventy-two hours after pellet implantation, animals were used for analyzing the effects of vehicle or intraperitoneal SR 141716A injections during conditioning sessions on the establishment of place aversion. Animals were exposed on day 0 to a preconditioning session, followed on day 1 to a vehicle injection (unpaired compartment) and on day 2 to SR141716A administration (paired compartment). Testing session was performed on day 3 and lasted 30 min.

Place preference in mice was performed as previously described (Ledent et al., 1999). Preconditioning and expression sessions lasted 18 min, whereas alternative saline or morphine conditioning sessions were of 20 min each. The experimental protocol includes two studies. Experiment 1 was designed to test the effects of acute administration of vehicle, SR 141716, morphine, or the combination in the establishment of place preference conditioning. Experiment 2 used the animals injected with vehicle or morphine of experiment 1 to test the effects of SR 141716A on the expression of an already acquired morphine-induced place preference. Morphine hydrochloride (5 mg/ml) was dissolved in saline and given subcutaneously before the mice was confined in the corresponding compartment during experiment 1. Morphine pellets (75 mg morphine base) or placebo pellets were implanted subcutaneously after the first place preference test. Seventy-two hours after pellet implantation, mice were tested again in the place preference paradigm for the experiment 2. The CB1 antagonist SR 141716A was administered intraperitoneally at the dose of 3 mg/kg dissolved in 5% chremophor, 5% ethanol, and 90% distilled water. This compound was given 10 min before the mouse was confined in the compartment in the conditioned period for the experiment 1 and 10 min before the testing phase in experiment 2. All compounds were given at 0.1 ml/10 gm body weight, except SR141716A which was given at 0.2 ml/10 gm body weight.

Data on place preference studies were expressed as the change of preference toward either the morphine-paired or the saline-paired compartment. This change of preference was calculated as the difference between the time spent in a compartment the day of expression and the time spent in that compartment on the day of preconditioning.

Opiate and cannabinoid withdrawal. Opiate withdrawal-related signs during self-administration sessions were rated according to theGellert and Holtzman (1978) rating scale. This scale consists of graded signs (weight loss, escape attempts, and wet-dog shakes) and checked signs (diarrhea, fasciculations, teeth chattering, swallowing movements, salivation, chromodacryorrhea, ptosis, abnormal posture, erection and/or ejaculation, and irritability on handling). Cannabinoid withdrawal was rated as previously described (Rodríguez de Fonseca et al., 1997). The cannabinoid withdrawal rating scale was composed of counted signs (wet-dog shakes, compulsive facial rubbings, grooming activity, and scratching sequences) and observed signs (including ptosis, piloerection, swallowing movements, salivation, penile grooming, or abnormal posture). The cannabinoid withdrawal rating scale does not include opiate withdrawal-associated signs like weight loss, teeth chattering, diarrhea, vocalization, or eye blinking. Counted signs (total number of events) were summed with observed signs (events observed over a specific observation time) and subjected to parametric statistics.

In situ hybridization. In situ hybridization for analyzing the CB1 receptor mRNA level in neurons of reward-relevant brain areas was performed as previously described (Navarro et al., 1998) using emulsion-coated paraformaldehyde-fixed tissue sections (20 μm) stained with methylene blue. They were obtained from: (1) animals treated with either saline (vehicle group) or morphine (acute morphine group; 10 mg/kg, i.p.) and killed 6 hr after the injection, (2) animals implanted under anesthesia with either two lactose pellets (placebo group) or two morphine (75 mg morphine base each) pellets (chronic morphine group) pellets and killed 48 hr after surgical implantation, or (3) animals killed 6 hr after removing the two morphine pellets that were implanted under anesthesia 48 hr before (abstinence group). Antisense- or sense-labeled cRNA probes were generated with T3 and T7 polymerases in the pBSK (+). The sense cRNA probe was used as a specific control and under identical conditions showed no detectable labeling. CB1 riboprobes were synthesized by using T3 polymerase plasmid generously provided by Dr. M. Parmentier (Université Libre de Bruxelles, Belgium), in a standard transcription reaction containing33P[UTP]. This resulted in probes with specific activities of ∼1.8 × 109dpm/μg. The probes were hydrolyzed in bicarbonate buffer to an average length of 150 bases and used for the hybridization studies. After hybridization overnight at 48°C, the slides were washed to reduce background, counterstained with cresyl violet, placed in 70% ethanol for 1 min, air-dried, and dipped in LM-1 photographic emulsion (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Arlington Heights, IL), and left exposed for 3 weeks. The slides were then developed and coverslipped. For quantitative analysis of CB1 mRNA expression, a computer-aided quantitation of silver grains of positive-labeled cells was performed as previously described (Busiguina et al., 2000). For each CB1 receptor mRNA-labeled neuron examined, a circular field of constant surface area was delimited over the soma whose boundaries were defined by methylene blue staining. Grain density was taken as an estimate of the level of hybridization signals, an index of the CB1 receptor mRNA expression per neuron. For each section, background grain density was measured over the neuropil of at least 40 neurons in randomly chosen fields and subtracted from the grain counts.

RESULTS

Effects of the cannabinoid receptor antagonist SR141716A on heroin self-administration in rats

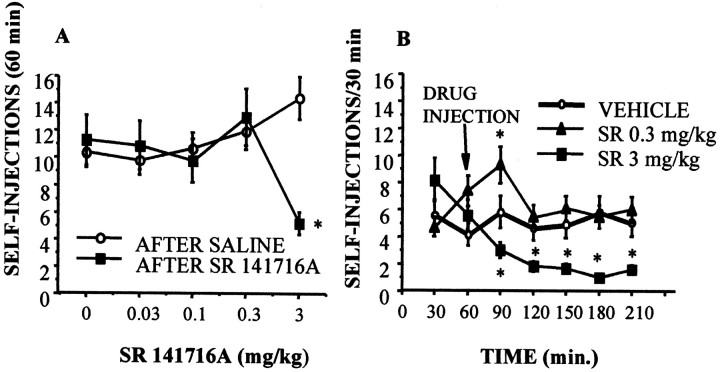

The acute administration of a cannabinoid receptor antagonist SR141716A (Rinaldi-Carmona et al., 1994) at a dose of 3 mg/kg resulted in a reduction of heroin self-administration (0.06 mg/kg per infusion) during the first hour after the injection (Fig.1A). A time analysis (Fig. 1B) showed that the dose of 0.3 mg/kg resulted in a transient increase of heroin self-administration in the first 30 min after the injection, whereas the 3 mg/kg dose profoundly decreased heroin infusions up to the end of the session (Fig.2B). This effect was selective and not associated to motor disturbances because at any of the doses selected for the present experiment the CB1 antagonist affected operant responses for food (Fig. 3B). Using the place conditioning paradigm, SR 141716A was found to be ineffective on inducing place preference, although the higher dose used (3 mg/kg) shifted the preference of the animal toward the compartment paired with this dose. This shift in the preference was not statistically significant. Testing day values for absolute time spent in the SR 141716A-paired compartment in seconds were (mean ± SEM): vehicle, 493.8 ± 68; SR 0.1 mg/kg, 450 ± 92; SR 0.3 mg/kg, 434.3 ± 82.7; and SR 3 mg/kg, 673.6 ± 123.2. These results indicate an absence of intrinsic rewarding properties of SR141716A in the range of doses used.

Fig. 1.

Effects of the CB1 receptor antagonist on heroin self-administration in Wistar male rats. A, Acute injection of SR 141716A (3 mg/kg) reduced heroin self-administration (0.06 mg/injection) in the next 60 min. B, Time analysis along the 210 min session revealed that the effect of 3 mg/kg SR 141716A was still present 150 min after its administration. At the dose of 0.3 mg/kg, the CB1 antagonist induced a temporary increase in heroin self-administration. The CB1 receptor antagonist failed to modify operant responses for food and did not induce place preference (see Results). *p < 0.01 versus saline-treated group; Newman–Keuls.

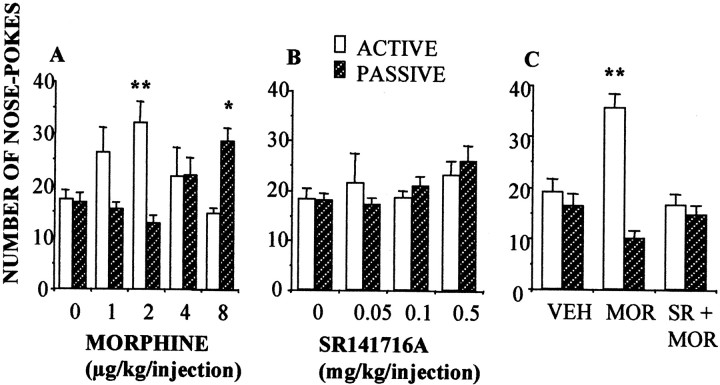

Fig. 2.

Effects of the CB1 receptor antagonist SR 141716A on opiate reinforcement in mice. A, Mice self-administered morphine following a bell-shaped dose–response curve. Injection of morphine or vehicle to active (open bars) and passive (hatched bars) mice was controlled by nose pokes of the active mouse. The number of nose pokes was recorded in n = 6–18 animals per group.B, The CB1 receptor antagonist SR141716A failed to induce self-administration. C, Pretreatment with SR 141716A (0.25 mg/kg, i.p.) 30 min before the onset of the session prevented morphine (2 μg/kg) self-administration. **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05, active versus passive; Newman–Keuls test.

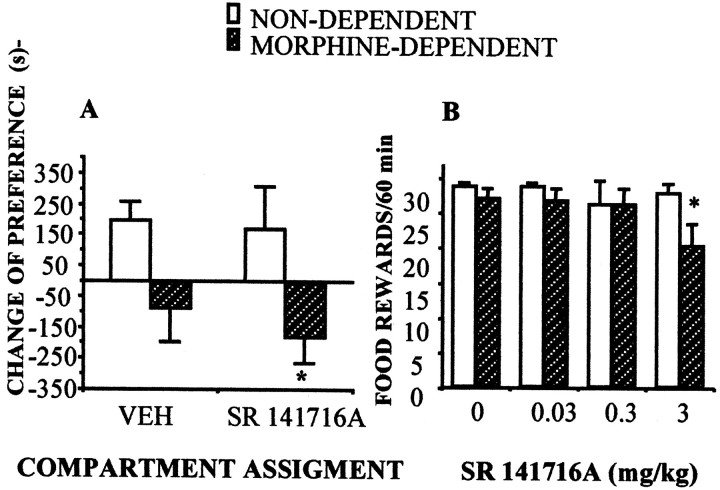

Fig. 3.

Effects of the administration of the CB1 receptor antagonist SR 141716A in morphine-dependent rats. A,Acute administration of SR 141716A (3 mg/kg) resulted in place aversion as reflected by the significant negative change of preference in morphine-dependent animals. n = 8–12 animals per group; *p < 0.05 SR141716A versus saline treatment; Newman–Keuls. B, CB1 cannabinoid receptor blockade affected operant responding for food (60 min sessions, FR 5, time out 2 min) in food-deprived animals (n = 9), only in morphine-dependent rats. *p < 0.05 SR141716A versus saline treatment; Newman–Keuls.

Effects of cannabinoid receptor blockade on morphine self-administration and morphine-induced place preference in mice

The above-described effects of the cannabinoid antagonist SR 141716A on opiate self-administration were replicated in mice (Fig. 2). Mice self-administered morphine (Fig. 2A) but they did not self-inject SR 141716A (Fig. 2B). However, SR 141716A administration blocked morphine self-administration (Fig.2C). Also, mice did not exhibit the transient increase in heroin self-administration observed in rats. Further research is needed to clarify whether this difference is based on species-specific responses or on the doses of SR141716A used in the present study in mice. However, cannabinoid receptor blockade profoundly disturbed the acquisition of morphine-induced place preference, a different model for evaluating the reinforcing properties of this opiate. These results clearly support the proposed mediation of the endogenous cannabinoid system on opiate reinforcement. Testing day values for the change of preference toward the different drug-paired compartments were (in seconds, mean ± SEM): vehicle-paired, −44 ± 41; SR 141716A-paired, 78 ± 80; morphine-paired, 166 ± 16 (p < 0.01 versus vehicle); and morphine + SR141716A-paired, 28 ± 61. In this model, the cannabinoid antagonist was not capable of inducing positive place preference conditioning, indicating again a lack of intrinsic rewarding properties.

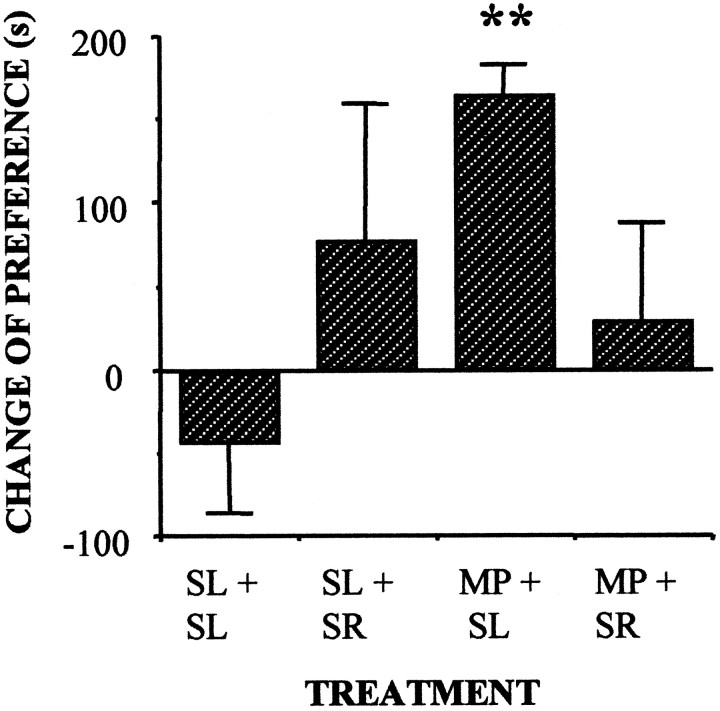

Effects of cannabinoid receptor blockade on opiate-dependent rodents

In an effort to further investigate the interactions between cannabinoid and opioid systems we studied the effects of cannabinoid receptor blockade in opiate-dependent animals. First we tested the potential aversive effects of cannabinoid receptor blockade in opiate-dependent rodents. Acute SR141716A (3 mg/kg) administration resulted in place aversion (Fig. 3A) and produced a decrease in the number of operant responses for food (Fig. 3B). These negative reinforcing properties of SR 141716A in opiate-dependent rats were also observed in morphine-dependent mice, on which the administration of the CB1 receptor antagonist blocked the expression of an already acquired morphine-induced place preference (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Acute administration of SR 141716A (3 mg/kg) blocked the expression of an already established morphine-induced place preference in morphine-dependent mice. SL, Saline;MP, morphine, SR, SR141716A. **p < 0.01, morphine-dependent versus saline-treated group; Scheffé F test.

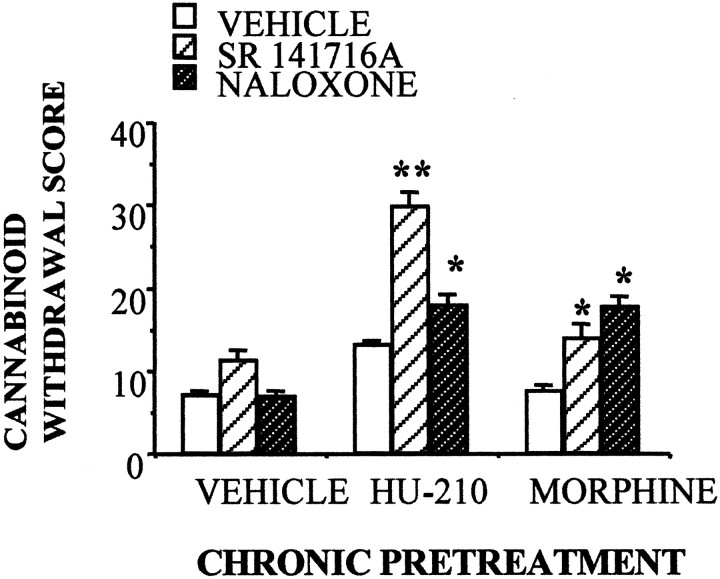

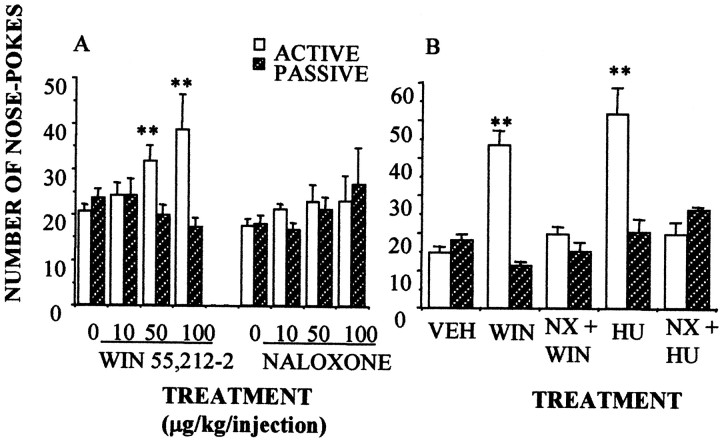

Effects of opioid receptor blockade on rodent models of cannabinoid dependence

The above-described experiments suggest the existence of a functional interaction between opioid and cannabinoid receptors in opiate addiction. The interaction is bidirectional because naloxone administration induced a partial cannabinoid withdrawal syndrome in rats chronically treated with the cannabinoid agonist HU-210 (100 μg · kg−1 · d−1for 14 d) (Fig. 5). Additionally, both SR141716A and naloxone precipitated a partial cannabinoid withdrawal syndrome in rats implanted with morphine pellets. The main differences between the withdrawal syndromes induced by naloxone and SR 141716A in HU-210-dependent animals were in the repetitive and abruptly interrupted motor sequences that characterize cannabinoid withdrawal (facial rubbings, paw fluttering, scratching, and grooming sequences). These behaviors did not appear after naloxone treatment. As described before (Navarro et al., 1998), neither diarrhea, weight loss, teeth chattering, nor chromodacryorrhoea were observed after SR141716A administration in opiate-dependent or cannabinoid-dependent animals. The opioid contribution to cannabinoid withdrawal also appeared in mice. Naloxone (0.1 and 1 mg/kg) was found to block the self-administration of the cannabinoid receptor agonists WIN 55,212–2 (0.1 mg/kg per infusion) (Fig.6A) and HU-210 (5 μg/kg per infusion) (Fig. 6B). Naloxone, however, was not self-administered by the rodents (Fig.6A).

Fig. 5.

Naloxone administration (1 mg/kg, i.p.) induced a partial cannabinoid withdrawal syndrome in male rats chronically exposed to either the cannabinoid receptor agonist HU-210 (100 μg/kg for 14 d) or to the opiate morphine (2 pellets of 75 mg of morphine base implanted subcutaneously for 72 hr). The cannabinoid antagonist SR 141716A (3 mg/kg) induced a partial cannabinoid withdrawal syndrome in morphine-dependent animals.n = 9–15 animals per group; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05, versus saline-treated animals; Newman–Keuls test.

Fig. 6.

Opioid involvement in cannabinoid self-administration. A, Mice did self-inject the CB1 receptor agonist WIN 55,212–2 (50 and 100 μg/kg per injection), although they did not self-inject the opioid receptor antagonist naloxone (NX). However, naloxone (B) (100 μg/kg) decreased the self-administration of the cannabinoid receptor agonists WIN 55,212–2 (WIN; 100 μg/kg per injection) and HU-210 (HU; 100 μg/kg per injection). n = 10–12 animals per group; **p < 0.01, active versus passive; Newman–Keuls test.

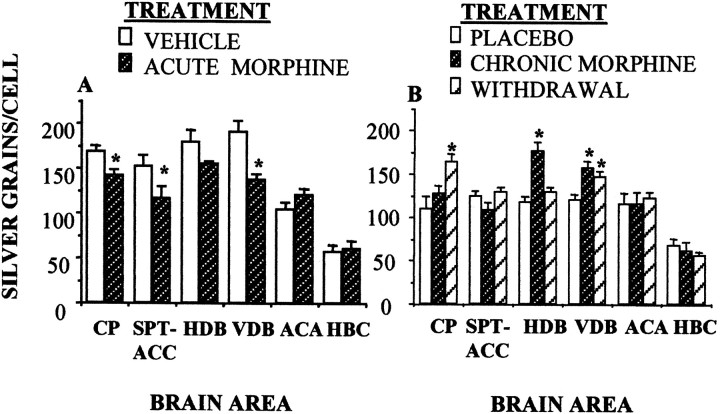

Effects of morphine on the expression of CB1 receptor mRNA in the rat brain

Acute administration of morphine resulted in specific changes in the expression of the CB1 cannabinoid receptor mRNA, as revealed by the analysis of grain density in the labeled neurons from the in situ hybridization. Morphine decreased the expression of the CB1 mRNA in the dorsal caudate putamen, the medial septum shell of the accumbens, and the vertical arm of the diagonal band of Broca (Fig.7A).These effects were reversed in both morphine-dependent and morphine-withdrawing animals (Fig. 7B). Morphine-dependent animals exhibited increased levels of the CB1 mRNA in the diagonal band of Broca and normal levels in the caudate putamen and septo-accumbens area. Withdrawal induced by removing morphine pellets increased the cell labeling in the caudate putamen and the vertical arm of the diagonal band.

Fig. 7.

Opioid involvement in cannabinoid CB1 receptor mRNA expression in the rat brain, measured by quantitative in situ hybridization histochemistry. A, Acute morphine (5 mg/kg) decreased the expression of the CB1 receptor mRNA in specific brain areas. B, Chronic morphine (2 pellets of 75 mg of morphine base implanted subcutaneously for 72 hr) or opiate withdrawal (removal of morphine pellets for 6 hr) reversed these effects. n = 3–4 animals per group; *p < 0.01, versus vehicle or placebo groups; Newman–Keuls test. CP, Caudate putamen;SPT-ACC, septum shell of accumbens; HDB, horizontal arm of the diagonal band of Broca; VDB, vertical arm of the diagonal band; ACA, anterior amygdaloid nuclei; HBC, habenular complex.

DISCUSSION

The present study supports the existence of converging opioid and cannabinoid mechanisms implicated in the acute positive reinforcing actions of opioids and cannabinoids in rodents. The finding of an association of a particular genetic variant of the human CB1 receptor to intravenous drug use, including opiates, further supports this hypothesis (Comings et al., 1997). The results also indicate the existence of parallel neuroadaptions in both the endogenous opioid and the endogenous cannabinoid systems that occur during both chronic opiate or chronic cannabinoid exposure. The demonstration of the pharmacological activity of SR 141716A as a blocker of the acute reinforcing properties of morphine and/or heroin in intact animals suggests that drugs acting as cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonists may be considered as a new therapeutic approach for the treatment of opiate addiction (Navarro et al., 1998; Rubino et al., 2000). These properties can be extended to ethanol abuse because SR141716A has been reported to suppress ethanol self-administration in rodents (Colombo et al., 1998;Gallate et al., 1999; Rodríguez de Fonseca et al., 1999), probably through the recently described ethanol-induced changes in both endocannabinoid synthesis and CB1 receptor function (Basavarajappa and Hungund, 1999). Although the present data may suggest that the CB1 antagonist SR 141716A has an opiate receptor antagonist-like profile, SR141716A cannot interact directly with μ-opioid receptors. Previous studies reported that this compound exhibited no affinity for any of the cloned opioid receptor subtypes (Rinaldi-Carmona et al., 1994).

The profile of these functional interactions suggests that the CB1 receptor seems to be necessary for the expression of the rewarding properties of morphine and heroin in intact rats and mice, as demonstrated using place preference and self-administration paradigms (Figs. 1, 2) (see Results). These present data confirm the findings described in CB1 receptor knock-out mice (Ledent et al., 1999; M.Martin et al., 2000), indicating that potential developmental alterations in reward circuits are not the neural basis of the lack of reinforcing effects of morphine in these animals. These results extended to the reward system the convergent mechanisms described for opioids and cannabinoids in analgesia, confirming the cooperation of cannabinoid CB1 receptors with opioid μ, δ, and κ receptors in multiple physiological roles (Welch and Stevens, 1992; Pugh et al., 1997; Mason et al., 1999; Manzanares et al., 1999; T. J. Martin et al., 2000).

Acute mechanisms contributing to the common effects of cannabinoids and opiates may include the already described convergent activatory actions of both types of psychoactive substances in ascending mesolimbic dopaminergic projections, resulting in an enhancement of dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens (Chen et al., 1990; Tanda et al., 1997; Gardner and Vorel, 1998). Supporting this hypothesis, we have recently found that morphine-induced increase in extracellular dopamine levels in the nucleus accumbens is dramatically attenuated in CB1 knock-out (Mascia et al., 1999). The ability of cannabinoid CB1 receptor-acting drugs to reduce heroin self-administration is also consistent with the recently described role of the anandamide–CB1 receptor system as a modulator of dopamine D2 receptor-mediated responses (Giuffrida et al., 1999). Dopamine D2 receptors are considered one of the major contributors to opiate-induced positive reinforcement (Maldonado et al., 1997), and the capacity of the cannabinoid receptor antagonist to interfere with the acquisition and expression of morphine-induced place preference resembles that described for dopamine D2–D3 receptor agonists such as 7-hydroxy-2(di-n-propylamino)tetralin (Rodríguez de Fonseca et al., 1995). However, the finding of cocaine-induced place preference and sensitization in CB1 receptor knock-out mice suggests a secondary role for cannabinoid CB1 receptor–dopamine receptor interaction in the molecular events responsible for the effects described on morphine reinforcement in the present study.

The blocking of heroin self-administration responses found with high doses of the CB1 antagonist SR 141716A (i.e., 3 mg/kg) may suggest the induction of a negative affective state, which was exacerbated by the induction of dependence (morphine pellet implantation) as reflected by the suppression of operant responses for food and the place aversion induced by SR141716A in the opiate-dependent animals. The finding of a naloxone-induced cannabinoid withdrawal in cannabinoid-dependent animals supports the bidirectional nature of these neuroadaptions. The underlying effects of chronic administration of opiates and cannabinoids may involve not only the direct actions on their homologous receptor system, but also the common intracellular signaling mechanisms. Thus, it has been described that both chronic cannabinoid and opiate exposure not only induces parallel desensitization in Gi-protein coupling to the adenylate cyclase (Sim et al., 1996a,b; Nestler and Aghajanian, 1997), but also a profound upregulation of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase activity to counteract the inhibition of the cAMP-dependent cascade of signaling events induced by both types of drugs (Blendy and Maldonado, 1998;Hutcheson et al., 1998; Koob et al., 1998). Additionally, chronic exposure to opiates or cannabinoids induce comparable neuroadaptions in specific transmitter systems, including dopamine (Diana et al., 1995,1998) and corticotropin-releasing factor (Heinrichs et al., 1995;Rodríguez de Fonseca et al., 1997). These adaptations contribute to the onset of the aversive state that characterize repeated drug exposure (Koob et al., 1998). Because both μ-opioid and CB1 cannabinoid receptors are located in the same neuronal cells of reward-relevant telencephalic nuclei (Navarro et al., 1998), it is possible that the effects of either the CB1 antagonist in opiate-dependent animals or the opioid receptor antagonist in cannabinoid-dependent rodents may reflect the convergence of both heterologous receptors to a common functional response in processing negative reinforcement, leading to a blockade of drug self-administration. In this regard, the experiments with in situ hybridization indicate that acute opiate exposure upregulated the CB1 signaling pathway in dorsal striatum, septo-accumbens, and diagonal band of Broca areas. Similar results have been reported in opiate-dependent mice (Rubino et al., 1997). Additionally subchronic cannabinoid administration upregulated the opioid signaling system in the CNS (Mailleux and Vanderhaeghen, 1994; Manzanares et al., 1999; Mason et al., 1999).

The present study provides solid evidence for the existence of a potential cross-talk between opioids and cannabinoids in brain motivational systems involved in drug dependence. As the identification of opioid–ethanol interactions leads to the clinical evaluation of opioid antagonists as a therapy in alcoholism, the existence of functional interactions between the endogenous cannabinoid system and the endogenous opioid signaling system may have a place as a new target for the pharmacotherapy of addiction.

Footnotes

This work has been supported by Dirección General de Investigación Cientifica y Técnica Grant PM 96/0047, Comisión Interministerial de Ciencia y Tecnología, Spain Grant SAF 2000-0101, Comunidad de Madrid (Grant 08.5/0013/98), and Plan Nacional Sobre Drogas (M.N., F.R.F., J.A.C., I.A., M.A.V.); National Institutes of Health Grant DK 26741 (G.F.K., M. R.C.); Ministero dell'Università della Riecrea Scientifica e Technologica and Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche (W.F., G.C., L.F.), BIOMED2 Grant PL982267, and Laboratorios Dr. Esteve (O.V., R.M.). M.N and F.R.F are research fellows of the Del Amo Program, Universidad Complutense de Madrid. We are grateful to Dr. M. Mossé (Sanofi Research) for generously providing SR141716A. This is publication number 12558-NP from The Scripps Research Institution.

Correspondence should be addressed to Miguel Navarro or Fernando Rodríguez de Fonseca, Departamento de Psicobiología, Facultad de Psicología, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, 28223 Madrid, Spain. E-mail: pspsc10@sis.ucm.es.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akil H. Endogenous opioids: biology and function. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1984;7:223–255. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.07.030184.001255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Basavarajappa BS, Hungund BL. Down-regulation of cannabinoid receptor agonist-stimulated [35S]-GTPγS binding in synaptic plasma membrane from chronic ethanol-exposed mouse. Brain Res. 1999;815:89–97. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)01072-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blendy JA, Maldonado R. Genetic analysis of drug addiction: the role of the cAMP response element binding protein. J Mol Med. 1998;76:104–110. doi: 10.1007/s001090050197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Busiguina S, Argente J, García-Segura LM, Chowen JA. Anatomically specific changes in the expression of somatostatin, growth hormone-releasing hormone and growth hormone receptor mRNA in diabetic rats. J Neuroendocrinol. 2000;12:29–39. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2000.00416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caine SB, Lintz R, Koob GF. Intravenous drug self-administration techniques in animals. In: Sahgal A, editor. Behavioral neuroscience: a practical approach. Oxford UP; Oxford: 1993. pp. 117–143. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carrera MRA, Schulteis G, Koob GF. Heroin self-administration in dependent Wistar rats: increased sensitivity to naloxone. Psychopharmacology. 1999;144:111–120. doi: 10.1007/s002130050983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaperon F, Soubrié P, Puech AJ, Thiebot MH. Involvement of central cannabinoid (CB1) receptors in the establishment of place conditioning in rats. Psychopharmacology. 1998;135:324–332. doi: 10.1007/s002130050518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen J, Paredes W, Li J, Smith D, Lowinson J, Gardner EL. Δ9- tetrahydrocannabinol produces naloxone-blockable enhancement of presynaptic basal dopamine efflux in nucleus accumbens of conscious, freely-moving rats, as measured by intracerebral microdialysis. Psychopharmacology. 1990;102:156–162. doi: 10.1007/BF02245916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colombo G, Agabio R, Fa M, Guano L, Lobina C, Loche A, Reali A, Gessa GL. Reduction of voluntary ethanol intake in ethanol-preferring sP rats by the cannabinoid antagonist SR 141716. Alcohol Alcohol. 1998;33:126–130. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.alcalc.a008368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Comings DE, Muhleman D, Gade R, Johnson P, Verde R, Saucier G, MacMurray J. Cannabinoid receptor gene (CNR1): association with iv drug use. Mol Psychiatry. 1997;2:161–168. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delfs JM, Kong H, Mestek A, Chen Y, Yu L, Reisine T, Chesselet MF. Expression of mu opioid receptor mRNA in the rat brain: an in situ hybridization study at the single cell level. J Comp Neurol. 1994;345:46–68. doi: 10.1002/cne.903450104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Devane WA, Dysarz FA, III, Johnson MR, Melvin LS, Howlett AC. Determination and characterization of a cannabinoid receptor in rat brain. Mol Pharmacol. 1988;34:605–613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Devane WA, Hanus L, Breuer A, Pertwee RG, Stevenson LA, Griffin G, Gibson D, Madelbaum A, Mechoulam R. Isolation and structure of a brain constituent that binds to the cannabinoid receptor. Science. 1992;258:1946–1949. doi: 10.1126/science.1470919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diana M, Pistis M, Muntoni M, Gessa GL. Profound decrease of mesolimbic dopaminergic neuronal activity in morphine withdrawn rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;272:781–785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diana M, Melis M, Muntoni AL, Gessa GL. Mesolimbic dopaminergic decline after cannabinoid withdrawal. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:10269–10273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.10269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Felder C, Glass M. Cannabinoid receptors and their endogenous agonists. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1998;38:179–200. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.38.1.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gallate JE, Saharov T, Mallet PE, McGregor IS. Increased motivation for beer in rats following the administration of a cannabinoid CB1 receptor agonist. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;370:233–240. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00170-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gardner EL, Vorel RS. Cannabinoid transmission and reward-related events. Neurobiol Dis. 1998;5:502–533. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.1998.0219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gellert VF, Holtzman SG. Development and maintenance of morphine tolerance and dependence in the rat by scheduled access to morphine drinking solutions. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1978;205:536–546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giuffrida A, Parsons LH, Kerr TM, Rodríguez de Fonseca F, Navarro M, Piomelli D. Dopamine activation of endogenous cannabinoid signaling in dorsal striatum. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:358–363. doi: 10.1038/7268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heinrichs SC, Menzaghi F, Schulteiss G, Koob GF, Stinus L. Suppression of corticotropin-releasing factor in the amygdala attenuates aversive consequences of morphine withdrawal. Behav Pharmacol. 1995;6:74–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herkenham M, Lynn AB, Johnson MR, Melvin LS, De Costa BR, Rice KC. Characterization and localization of cannabinoid receptors in rat brain: a quantitative in vitro autoradiographic study. J Neurosci. 1991;11:563–583. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-02-00563.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hine B, Friedman E, Torrelio M, Gershon S. Morphine-dependent rats: blockade of precipitated abstinence by tetrahydrocannabinol. Science. 1975;187:443–445. doi: 10.1126/science.1167428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Howlett AC. Pharmacology of cannabinoid receptors. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1995;35:607–634. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.35.040195.003135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hutcheson DM, Tzavara ET, Smadja C, Valjent E, Roques BP, Hanoune J, Maldonado R. Behavioural and biochemical evidence for signs of abstinence in mice treated chronically with delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;125:1567–1577. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kieffer BL. Opioids: first lessons from knockout mice. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1999;20:19–26. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(98)01279-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koob GF, Sanna PP, Bloom FE. Neuroscience of addiction. Neuron. 1998;21:467–476. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80557-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ledent C, Valverde O, Cossu G, Petitet F, Aubert JF, Beslot F, Bohme GA, Imperato A, Pedrazzini T, Roques BP, Vassart G, Fratta W, Parmentier M. Unresponsiveness to cannabinoids and reduced addictive effects of opiates in CB1 receptor knockout mice. Science. 1999;283:401–404. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5400.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mailleux P, Vanderhaeghen JJ. Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol regulates substance P and enkephalin mRNAs levels in caudate putamen. Eur J Pharmacol. 1994;267:R1–R3. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(94)90234-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maldonado R, Saiardi A, Valverde O, Samad TA, Roques BP, Borrelli E. Absence of opiate rewarding effects in mice lacking dopamine D2 receptors. Nature. 1997;388:536–539. doi: 10.1038/41567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mansour A, Fox CA, Akil H, Watson SJ. Opioid-receptor mRNA expression in the rat CNS: anatomical and functional implications. Trends Neurosci. 1995;18:22–29. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(95)93946-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manzanares J, Corchero J, Romero J, Fernandez-Ruiz JJ, Ramos JA, Fuentes JA. Pharmacological and biochemical interactions between opioids and cannabinoids. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1999;20:287–294. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01339-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martellota MC, Cossu G, Fattore L, Gessa GL, Fratta W. Self-administration of the cannabinoid receptor agonist WIN 55,212–2 in drug-naive mice. Neuroscience. 1998;85:327–330. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00052-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martin M, Ledent C, Parmentier M, Maldonado R, Valverde O. Cocaine, but not morphine, induces conditioned place-preference and sensitization to locomotor responses in CB1 knockout mice. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:4038–4046. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martin TJ, Kim SA, Cannon DG, Sizemore GM, Bian D, Porreca F, Smith SE. Antagonism of delta(2)-opioid receptors by naltrindole-5′-isothiocyanate attenuates heroin self-administration but not antinociception in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;294:975–982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mascia MS, Obinu MC, Ledent C, Parmentier M, Bohme GA, Imperato A, Fratta W. Lack of morphine-induced dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens of Cannabinoid CB1 receptor knockout mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;383:R1–R2. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00656-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mason DJ, Jr, Lowe J, Welch SP. A diminution of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol modulation of dynorphin A(1–17) in conjunction with tolerance development. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;381:105–111. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00542-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Matsuda L, Lolait SJ, Brownstein MJ, Young AC, Bonner TI. Structure of a cannabinoid receptor and functional expression of the cloned cDNA. Nature 346 1990. 561 564 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Matsuda LS, Bonner TI, Lolait SJ. Localization of cannabinoid receptor mRNA in rat brain. J Comp Neurol. 1993;327:535–550. doi: 10.1002/cne.903270406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matthes HW, Maldonado R, Simoninin F, Valverde O, Slowe S, Kitchen I, Befort K, Dierich A, Le Meur M, Dolle P, Tzavara E, Hanoune J, Roques BP, Keiffer BL. Loss of morphine-induced analgesia, reward effect and withdrawal symptoms in mice lacking the mu-opioid-receptor gene. Nature. 1996;383:819–823. doi: 10.1038/383819a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mechoulam R, Ben-Shabat S, Hanus L, Ligumsky M, Kaminski NE, Schatz AR, Gopher A, Almog S, Martin BR, Compton DR, Pertwee RG, Griffin G, Bayewitch M, Barg J, Vogel Z. Identification of an endogenous 2-monoglyceride, present in canine gut, that binds to cannabinoid receptors. Biochem Pharmacol. 1995;50:83–90. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(95)00109-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Navarro M, Chowen JA, Carrera MRA, del Arco I, Villanœa MA, Martin Y, Roberts AJ, Koob GF, Rodríguez de Fonseca F. CB1 cannabinoid receptor antagonist-induced opiate withdrawal in morphine-dependent rats. NeuroReport. 1998;9:3397–3402. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199810260-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nestler EJ, Aghajanian GK. Molecular and cellular basis of addiction. Science. 1997;278:58–63. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5335.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pugh G, Jr, Mason DJ, Jr, Combs V, Welch SP. Involvement of dynorphin B in the antinociceptive effects of the cannabinoid CP 55,940 in the spinal cord. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;281:730–737. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reisine T, Law SF, Blake A, Tallent M. Molecular mechanisms of opiate receptor coupling to G proteins and effector systems. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1996;780:168–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb15121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rinaldi-Carmona M, Barth F, Heaume M, Shire D, Calandra B, Congy C, Martínez S, Maruani J, Neliat G, Caput D, Ferrara P, Soubrie P, Breliere JC, Le Fur G. SR141716A, a potent and selective antagonist of the brain cannabinoid receptor. FEBS Lett. 1994;350:240–244. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00773-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rodríguez de Fonseca F, Rubio P, Martín-Calderón JL, Caine SB, Koob GF, Navarro M. The dopamine receptor agonist 7-OH-DPAT modulates the acquisition and expression of morphine-induced place preference. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;274:47–55. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)00708-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rodríguez de Fonseca F, Carrera MRA, Navarro M, Koob GF, Weiss F. Activation of Corticotropin-releasing factor in the limbic system during cannabinoid withdrawal. Science. 1997;276:2050–2054. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5321.2050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rodríguez de Fonseca F, Roberts AJ, Bilbao A, Koob GF, Navarro M. Cannabinoid receptor antagonist SR141716a decreases operant ethanol self administration in rats exposed to ethanol-vapor chambers. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 1999;20:1109–1114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rubino T, Tizzoni L, Vigano D, Massi P, Parolaro D. Modulation of rat brain cannabinoid receptors after chronic morphine treatment. NeuroReport. 1997;8:3219–3223. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199710200-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rubino T, Massi P, Vigano D, Fuzio D, Parolaro D. Long-term treatment with SR141716A, the CB1 receptor antagonist influences morphine withdrawal syndrome. Life Sci. 2000;66:2213–2219. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(00)00547-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sim LJ, Selley DE, Dworkin SI, Childers SR. Effects of chronic morphine administration on mu opioid receptor-stimulated [35S]GTPγS autoradiography in rat brain. J Neurosci. 1996a;16:2684–2692. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-08-02684.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sim LJ, Hampsom RE, Deadwyler SA, Childers SR. Effects of chronic treatment with Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol on cannabinoid-stimulated [35S]GTPγS autoradiography in rat brain. J Neurosci. 1996b;16:8057–8066. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-24-08057.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stella N, Schweitzer P, Piomelli D. A second endogenous cannabinoid that modulates long-term potentiation. Nature. 1997;388:773–778. doi: 10.1038/42015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tanda G, Pontieri FE, Di Chiara G. Cannabinoid and heroin activation of mesolimbic dopaminergic transmission by a common μ1 opioid receptor mechanism. Science. 1997;276:2048–2050. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5321.2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tanda G, Munzar P, Goldberg SR. Self-administration behavior is maintained by the psychoactive ingredient of marijuana in squirrel monkeys. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:1073–1074. doi: 10.1038/80577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thompson RC, Mansour A, Akil H, Watson SJ. Cloning and pharmacological characterization of a rat mu opioid receptor. Neuron. 1993;11:903–913. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90120-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Valverde O, Ledent C, Beslot F, Parmentier M, Roques BP. Reduction of stress-induced analgesia but not of exogenous opioid effects in mice lacking CB1 receptors. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:533–539. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00929.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vela G, Ruiz-Gayo M, Fuentes JA. Anandamide decreases naloxone-precipitated withdrawal signs in mice chronically treated with morphine. Neuropharmacology. 1995;34:665–668. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(95)00032-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Volpicelli JR, Alterman AI, Hayashida M, O'Brien CP. Naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:876–880. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820110040006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Welch SP, Stevens DL. Antinociceptive activity of intrathecally administered cannabinoids alone, and in combination with morphine, in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992;262:10–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]