Abstract

Recent studies in Aplysia have revealed a novel postsynaptic Ca2+ component to posttetanic potentiation (PTP) at the siphon sensory to motor neuron (SN–MN) synapse. Here we asked whether the postsynaptic Ca2+component of PTP was a special feature of the SN–MN synapse, and if so, whether it reflected a unique property of the SN or the MN. We examined whether postsynaptic injection of BAPTA reduced PTP at SN synapses onto different postsynaptic targets by comparing PTP at SN–MN and SN–interneuron (L29) synapses. We also examined PTP at L29–MN synapses. Postsynaptic BAPTA reduced PTP only at the SN–MN synapse; it did not affect PTP at either the SN–L29 or the L29–MN synapse, indicating that the SN and the MN do not require postsynaptic Ca2+ for PTP with all other synaptic partners. The postsynaptic Ca2+ component of PTP is present at other Aplysia SN–MN synapses; tail SN–MN synapses also showed reduced PTP when the MN was injected with BAPTA. Surprisingly, in both tail and siphon SN–MN synapses, there was an inverse relationship between the initial size of the EPSP and the postsynaptic component to PTP; only the initially weak SN–MN synapses showed a BAPTA-sensitive component. Homosynaptic depression of initially strong SN–MN synapses into the size range of initially weak synapses did not confer postsynaptic Ca2+ sensitivity to PTP. Finally, the postsynaptic Ca2+ component of PTP could be induced in the presence of APV, indicating that it is not mediated by NMDA receptors. These results suggest a dual model for PTP at the SN–MN synapse, in which a postsynaptic Ca2+contribution summates with the conventional presynaptic mechanisms to yield an enhanced form of PTP.

Keywords: synaptic plasticity, Aplysia, postsynaptic Ca2+, posttetanic potentiation, sensory neurons, short-term facilitation

Activity-dependent synaptic facilitation can exist across a broad range of temporal domains, from milliseconds to days and weeks. Long-term potentiation (LTP), a form of enhancement in synaptic strength that can persist for weeks, has been extensively studied and widely proposed as a key cellular mechanism underlying memory (Bliss and Collingridge, 1993; Huang et al., 1994;Buonomano, 2000). In contrast, short-term synaptic enhancement (STE), lasting seconds to minutes, has received relatively less experimental attention. Nevertheless, there is increasing evidence that STE is important for on-line information processing in a number of systems (Zucker, 1989; Delaney and Tank, 1994; Regehr et al., 1994; Fischer and Carew, 1995; Gerstner and Abbott, 1997). There are at least three distinct forms of STE, which can be differentiated by both the amount of presynaptic activity required for their induction and the duration of the synaptic enhancement (Zucker, 1989; Fisher et al., 1997). The most sustained form of STE is posttetanic potentiation (PTP), which has a time course on the order of minutes (Zucker, 1989; Fisher et al., 1997).

Unlike LTP, which appears to rely on both presynaptic and postsynaptic mechanisms (Lynch et al., 1983; Malenka et al., 1989; Bekker and Stevens, 1990; Larkman et al., 1992; Nicoll and Malenka, 1995; Malenka and Nicoll, 1999), PTP has generally been considered to be an entirely presynaptic phenomenon. There has been considerable support for the idea that PTP is mediated by an accumulation of free Ca2+ that enters the presynaptic terminal during activity (Zucker, 1989; Delaney and Tank, 1994; Kamiya and Zucker, 1994). Thus, it was surprising when postsynaptic Ca2+ emerged as a contributing factor to PTP at sensorimotor synapses in Aplysia. Two groups independently described the fact that strong postsynaptic hyperpolarization during presynaptic tetanus reduces the amount of PTP (Cui and Walters, 1994; Lin and Glanzman, 1994). These observations suggest that at least some synapses may require an influx of postsynaptic Ca2+ for the induction of PTP. Additional support for this idea came from work by Bao et al. (1997), who used cultured Aplysia sensory to motor neuron (SN–MN) synapses to examine the effects of manipulating postsynaptic Ca2+. They found that blocking the rise in postsynaptic Ca2+with either strong postsynaptic hyperpolarization or injection of the Ca2+ chelator BAPTA into the MN attenuated the amount of PTP induced at the SN–MN synapse.

A natural question following from the work described above is whether the postsynaptic Ca2+ contribution to PTP is specific to the SN–MN synapse or whether it is a general property of Aplysia synapses. This question prompted Fischer et al. (1997) to explore a possible postsynaptic Ca2+ dependency of PTP at an inhibitory interneuronal synapse (L30–L29) within the siphon withdrawal reflex (SWR) circuitry of Aplysia. They found that chelating Ca2+ in the postsynaptic neuron (L29) did not affect the magnitude of PTP generated at the synapse, whereas chelating Ca2+ in the presynaptic neuron (L30) with flash photolysis after PTP induction completely abolished PTP. These results indicate that the L29–L30 synapse inAplysia displays the common type of PTP that is thought to be mediated exclusively by residual presynaptic Ca2+.

Collectively, the results obtained thus far in Aplysiaindicate that the SN–MN synapse exhibits a unique form of PTP that has a postsynaptic Ca2+ contribution. This observation raises the intriguing question as to the nature of the SN–MN synapse that endows it with this special property. Is the postsynaptic component of PTP at this synapse a unique feature of the presynaptic cell (SN), the postsynaptic cell (MN), both, or neither? The aim of the current study was to study this question in detail. Because the SNs, L29 interneurons, and the MNs are interconnected, the SWR circuit provides the opportunity to examine the specificity of postsynaptic Ca2+ contribution to PTP at synapses in a well-defined functional circuit. We examined whether the postsynaptic Ca2+ component of PTP was specific to the SN by blocking the rise in postsynaptic Ca2+ at synapses that share a common presynaptic cell (SN) but differ in their postsynaptic targets (MN and L29). We examined the possibility that the postsynaptic Ca2+ contribution to PTP was specific to the MN by comparing the effects of blocking the postsynaptic increase in Ca2+ on PTP at two synapses with differing presynaptic neurons (the SN and the L29 interneuron) that share a common postsynaptic target (MN). Our results revealed a postsynaptic Ca2+ contribution to PTP at a subset of siphon SN–MN synapses. In addition, this postsynaptic Ca2+ component of PTP is present at tail SN–MN synapses in Aplysia. We found a similar reduction in PTP using postsynaptic BAPTA injection at SN–MN synapses in the tail withdrawal circuit, indicating that the postsynaptic Ca2+ contribution to PTP may be a general property of Aplysia SN–MN synapses. Finally, our findings suggest the hypothesis that the postsynaptic Ca2+ contribution at these synapses gives rise to an enhanced component of PTP that appears to summate with the more typical, presynaptic form of PTP.

Parts of this paper have been published previously in abstract form (Schaffhausen et al., 1998, Schaffhausen and Carew, 1999).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Adult Aplysia californica (120–200 gm) were acquired commercially (Marinus, Long Beach, CA; Marine Specimens Unlimited, Long Beach, CA; Aplysia Resource Center, Coral Gables, FL) and housed individually in a 600 l aquarium with continuously circulating artificial seawater (ASW) (Instant Ocean; Aquarium Systems, Mentor, OH) at ∼15°C. Animals were fed dried seaweed weekly.

Experimental preparation. Animals were anesthetized by injection of isotonic MgCl2 (∼50% of body weight). Abdominal ganglia were removed and pinned ventral side up on a Petri dish coated with a thin layer of silicone elastomer (Sylgard; Dow Corning, Midland, MI). The ganglia were desheathed to expose the cluster of neurons involved in the SWR. Desheathing was conducted in a 1:1 mixture of ASW (in mm: 460 NaCl, 55 MgCl2, 11 CaCl2, 10 KCl, and 10 Tris, pH 7.5) and isotonic MgCl2 to prevent synaptic transmission during dissection. Throughout the experiments, ganglia were perfused continuously (1 ml/min) with ASW (∼20°C) at a rate of 1 ml/min, unless otherwise specified.

Intracellular recordings. Standard intracellular recording techniques were used. Neurons were impaled with glass microelectrodes (resistance of 5–10 MΩ) filled with 3 mKCl. For the duration of the experiment, MNs were hyperpolarized (0.3–3.5 nA) to −65 mV to prevent spiking. L29 and SN resting potentials were not manipulated. The resting potential and input resistances of the neurons were monitored throughout the experiment to ensure a healthy preparation. Fewer than 5% of preparations were excluded because of changes in membrane resting potential or input resistance.

Drug administration. Two hundred (1×) or 600 mm (3×) BAPTA (tetrapotassium salt; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was dissolved in 3m KCl, 10 mm HEPES buffer, and 3 mm fast green dye (Fisher Scientific, Houston, TX). BAPTA loading was accomplished by impaling neurons with a beveled microelectrode (3–5 MΩ) and then injecting BAPTA with 3–5 pulses (20 msec, 20–40 psi) from a picospritzer (General Valve, Fairfield, NJ). In experiments in which L29 was injected, the efficacy of BAPTA was assessed by examining the monosynaptic connection between L29 and the LFS motor neuron every 2 min until there was no evidence of transmission, even with sustained activation of L29. In all cases, transmission from L29 to the MN was abolished within 20 min. In experiments in which the MN was BAPTA loaded, successful injection was determined by visualizing the fast green dye inside the cell, and a minimum of 20 min was allowed for BAPTA to take effect. In control experiments, neurons were injected with the 3 mKCl, 10 mm HEPES, and 3 mmfast green mixture.

For experiments involving APV (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), the drug was dissolved in ASW at a concentration of 50 μm and perfused continuously over the ganglion.

Data acquisition. Recordings were made using intracellular amplifiers (Getting, Model 5A; Axoclamp 2; Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA) and displayed on a storage oscilloscope (model 5111A; Tektronix, Wilsonville, OR). A MACLAB (version 8/s; ADInstruments, Castle Hill, Australia) data acquisition unit with appropriate software (Chart 3.6/s; ADInstruments) provided measurements of EPSP amplitude, duration, and integrated area. Data were digitized and stored on tape and then later replayed for analysis.

Experimental protocol. In all experiments, drug and control groups were examined in separate ganglia. The postsynaptic cell (either MN or L29) was impaled first with a beveled electrode (3–6 MΩ) and then pressure-injected with either BAPTA or control solution. Twenty minutes later, the presynaptic cell (either SN or L29) was impaled. After 1 min, a depolarizing pulse (40 msec, 0.5–2.5 nA) was injected into the presynaptic neuron to elicit a single pretest spike, thus establishing a baseline EPSP amplitude. One minute later, a tetanus (20 Hz for 2 sec for the SN–MN and SN–L29 synapses; 5 sec for the L29–MN synapses) was administered to the presynaptic neuron with a Grass stimulator (model S88D; Grass Instruments, Quincy, MA). A posttest was conducted 10 sec after termination of the tetanus, again by eliciting a single spike in the presynaptic cell. Playback of the video cassette recording tape ensured that the presynaptic neuron had fired during the tetanus (close to 100% of preparations), and experiments were included in the data set only if the synapse showed PTP (>85% of preparations).

An additional set of experiments was conducted examining PTP at the SN–MN synapse with the BAPTA concentration in the MN tripled to 600 mm, with all other parameters the same as described above. Experiments with APV were performed identically to those described above, except the ganglion was perfused with 50 μm APV dissolved in ASW for the duration of the experiment. For experiments involving homosynaptic depression, current (1–3 nA) was injected into the SN to elicit a single spike once every 10 sec for 100 sec (a total of 10 spikes) to induce homosynaptic depression. Ten sec after the 10th spike, the SN received a tetanus exactly as in other experiments. PTP was measured 10 sec later. Control experiments were performed in which there was no SN tetanus before the last test point, so that it was possible to determine the amount of recovery from depression that occurred between the penultimate and final test points.

Statistics. For all experiments involving BAPTA and APV, the amount of PTP (determined as the percent change in EPSP amplitude over baseline after SN tetanus) was averaged for both drug and control groups. The group averages were then compared using two-tailedt tests for independent means. For the homosynaptic depression experiments, PTP was measured as the percent change from the last pretest (the 10th stimulation) to the 10 sec posttest after tetanus, and the amount of PTP for the BAPTA and non-BAPTA controls was compared using a t test for independent means. In all cases, a p < 0.05 was considered significant. In instances in which the amount of PTP induced was greater than three SDs beyond the mean PTP (n = 2), the experiment was ruled an outlier and not included in the final data set.

RESULTS

At the SN–MN synapse, greater PTP is observed at initially weak synapses compared with initially strong ones

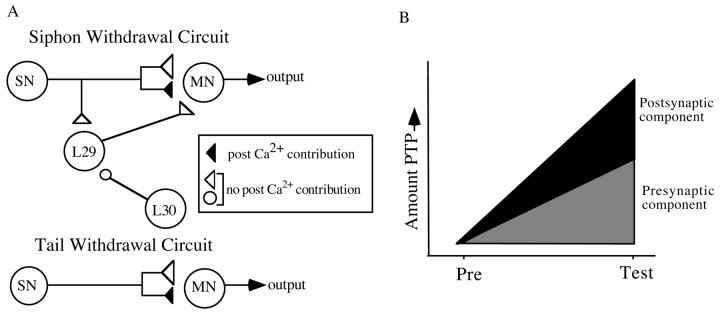

The primary goal of this study was to examine the postsynaptic Ca2+ contribution to PTP at a number of synapses in the SWR circuit (Fig. 1). Our first step in this analysis was to examine the SN–MN synapse, in which a postsynaptic component had been identified previously in culture (Lin and Glanzman, 1994; Bao et al., 1997). To examine whether there was also a postsynaptic Ca2+ component of PTP at these synapses within the intact CNS, we compared PTP at two groups of SN–MN synapses: one group that had BAPTA injected in the MN and one control group with no BAPTA. The large number of SN–MN synapses used in this study (n = 57) provided the opportunity to examine PTP in detail, and the experiments yielded two basic results.

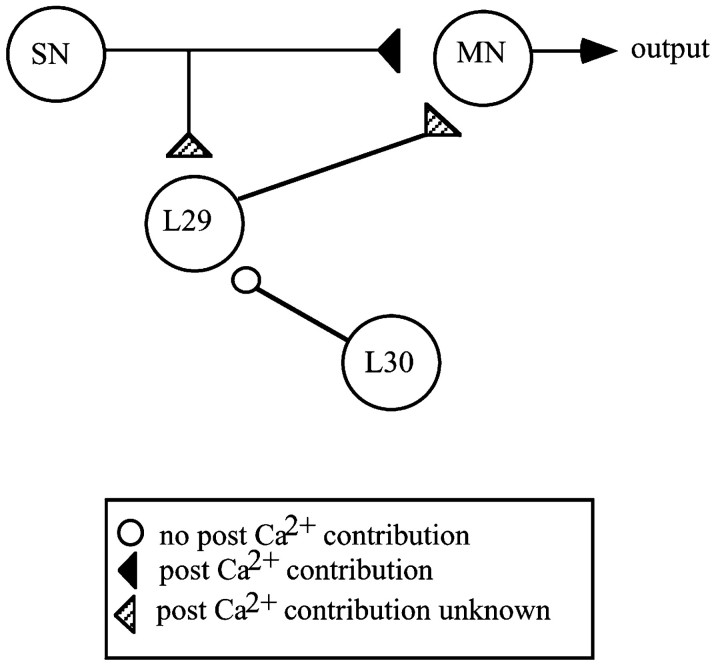

Fig. 1.

A schematic diagram of the siphon withdrawal circuit showing synaptic sites in which postsynaptic Ca2+ is involved in PTP (black synapses), in which postsynaptic Ca2+ is not involved in PTP (white synapses), and in which the role of postsynaptic Ca2+ in PTP is unknown (striped synapses). In all cases,triangles represent an excitatory synapse, andcircles represent inhibitory synapses. L30–L29 data are from Fischer et al. (1997).

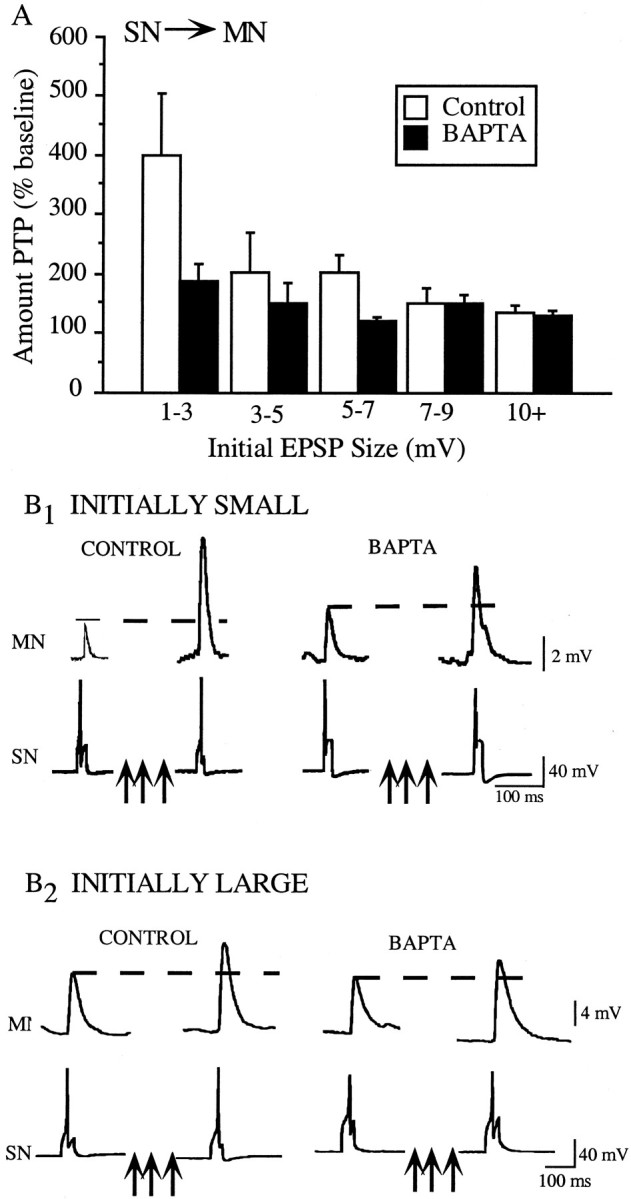

First, we found that the magnitude of PTP induced at SN–MN synapses in the control group was not uniform. Instead, there was an inverse relationship between the initial EPSP size and the magnitude of PTP generated at the synapse (Fig.2A, white bars). The weakest synapses (1–3 mV) displayed a striking capacity for facilitation, showing PTP that was more than double the amount for the stronger synapses (400% of baseline vs 160% of baseline). Although it could be argued that the larger amount of PTP seen at the weaker synapses reflects either (1) a “ceiling effect” for PTP at the stronger synapses or (2) was a consequence of smaller initial values yielding a greater percent change, several lines of evidence suggest that this is not the case (see Discussion).

Fig. 2.

PTP at the SN–MN is not uniform, and only initially weak synapses are sensitive to postsynaptic BAPTA injection.A, The magnitude of PTP induced at the SN–MN synapse is inversely proportional to the initial size of the synapse (white bars), with the weakest synapses showing the greatest amount of PTP. Injections of BAPTA into the MN significantly reduced PTP at the weaker synapses but did not affect the amount of PTP induced at the stronger synapses (compare black bars with white bars). For control groups, 1–3 mV (n = 7), 3–5 mV (n = 5), 5–7 mV (n = 5), 7–9 mV (n = 4), and 10+ mV (n = 7); for BAPTA groups, 1–3 mV (n = 8), 3–5 mV (n = 7), 5–7 mV (n = 4), 7–9 mV (n = 6), and 10+ (n = 5).B1, Representative SN–MN traces in which both synapses were initially weak. The magnitude of PTP at the BAPTA-loaded synapse was only half of the amount seen at the control synapse. B2, Representative SN–MN traces in which both synapses were initially strong. There was no difference in the magnitude of PTP induced at the BAPTA-loaded and control synapse.

Our second major finding was that BAPTA injection in the MN did not reduce PTP at all SN–MN synapses. Rather, PTP was attenuated only at synapses that were initially weak (Fig. 2A,black bars). The sample traces in Figure 2(B1, B2,left) show findings from both types of experiments. First, consider the traces from the control groups. Pronounced PTP is evident at the initially weak synapse (Fig.2B1, left), which facilitated from 3.92 to 10.74 mV, a change to 274% of baseline. In contrast, the EPSP in the control group for initially strong synapses facilitated to only 143% of baseline, from 10.99 to 15.97 mV (Fig.2B2). These traces also illustrate our finding that BAPTA selectively reduces PTP at the initially weak SN–MN synapses and does not affect the magnitude of PTP at the initially strong synapses. Figure2B1 shows typical results from control and BAPTA groups within the initially weak category. Although the initial amplitudes of the EPSPs for both groups were ∼4 mV, PTP at the BAPTA-loaded synapse was greatly reduced. The control synapse facilitated to 274% of baseline, whereas the BAPTA synapse facilitated to just 146% of baseline. This result contrasts with the experiments shown in Figure 2B2, which illustrates traces from both the control and BAPTA groups in the initially strong category. The PSPs in the control and BAPTA groups both had initial amplitudes of close to 11 mV, and both facilitated to ∼15.5 mV, ∼140% of baseline.

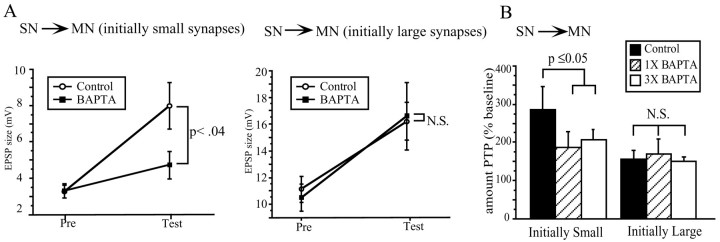

Figure 3 shows summary data for PTP experiments at the initially weak and initially strong SN–MN synapses. The data are expressed as changes in absolute EPSP amplitude. To determine whether there was a significant difference between the amount of BAPTA-induced reduction in PTP at weak versus strong SN–MN synapses, we divided the data set at the mean of the initial EPSP size (6.2 ± 0.52 mV, mean ± SE). “Weak” PSPs were defined as those that were initially less than the mean of all of the pretest PSPs, and those initially greater than the mean were categorized as “strong.” The data for initially weak synapses (Fig.3) reveal a significant reduction in the amount of PTP induced in the BAPTA-loaded synapses compared with control synapses (t(31) = 2.217; p < 0.04). The magnitude of the reduction was ∼50%, bringing the average amount of PTP down from 285 to 150% of baseline. In contrast, the amount of PTP induced at the initially strong SN–MN synapses was not affected by postsynaptic BAPTA injection. There was no change in the amount of PTP at strong SN–MN synapses because of postsynaptic BAPTA injection (t(16) = 0.146; NS). Both BAPTA and control groups showed the same average magnitude of facilitation, ∼160% of baseline.

Fig. 3.

Postsynaptic BAPTA injection significantly reduced PTP at weak SN–MN synapses (<6.2 mV) but did not affect PTP at strong SN–MN synapses (>6.2 mV). A, At initially weak SN–MN synapses (left), PTP was significantly reduced by BAPTA injection into the MN. Control synapses (n = 15) showed an enhanced form of PTP, facilitating to 285% of baseline, whereas BAPTA-loaded synapses (n = 18) facilitated to only 150% of baseline. The magnitude of PTP at initially strong SN–MN synapses (right) was not affected by postsynaptic BAPTA injection. Both the control synapses (n = 12) and BAPTA-loaded synapses (n = 11) facilitated to ∼160% of baseline. B, Tripling the concentration of BAPTA in the MN does not change the distribution of BAPTA-sensitive SN–MN synapses. At both the 200 and 600 nm concentrations, BAPTA was equally effective in significantly reducing PTP at the initially weak SN–MN synapses. Neither concentration of BAPTA affected the magnitude of PTP at the initially strong SN–MN synapses.

These results support the previous findings of Bao et al. (1997), who reported that there is a postsynaptic Ca2+ contribution to PTP at the SN–MN synapse. In addition, our results show that the amount of PTP induced at the SN–MN synapse is not uniform. Rather, it is a function of the initial strength of the synapse, with the weakest synapses showing the largest degree of PTP. Also, we found that not all SN–MN synapses are alike in their BAPTA sensitivity. Only the initially weak SN–MN synapses that exhibit the greatest PTP are sensitive to postsynaptic BAPTA injection.

The argument could be made that our failure to detect a reduction in PTP at the initially strong synapses was attributable to insufficient Ca2+ chelation in the MN. That is, perhaps the stronger EPSPs were accompanied by a greater postsynaptic Ca2+ influx than the weak EPSPs. If this were the case, it might follow that the concentration of BAPTA we used was sufficient to effectively chelate Ca2+for weak EPSPs but not sufficient to chelate Ca2+ for the strong EPSPs. To directly examine this question, we repeated the above experiments with a threefold increase in the amount of BAPTA injected into the MN (from 200 to 600 mm). If the lack of a BAPTA effect at initially strong synapses was simply attributable to insufficient chelation of Ca2+, then tripling the BAPTA concentration in the MN should reveal a BAPTA sensitivity at initially strong synapses. As shown in Figure 3B, tripling the concentration of BAPTA in the MN did not confer BAPTA sensitivity on strong synapses. Moreover, PTP at initially weak synapses was not further attenuated by the greater concentration of BAPTA, because both 1× and 3× BAPTA conditions reduced the amount of PTP by ∼50% compared with controls (each group significantly different from controls; p < 0.05). Likewise, the magnitude of PTP at initially strong synapses was not significantly changed by the presence of increased postsynaptic BAPTA. These findings further support the hypothesis that only the enhanced form of PTP observed at the weak SN–MN synapses has a postsynaptic Ca2+component.

There is no postsynaptic Ca2+contribution to PTP at the SN–L29 synapses

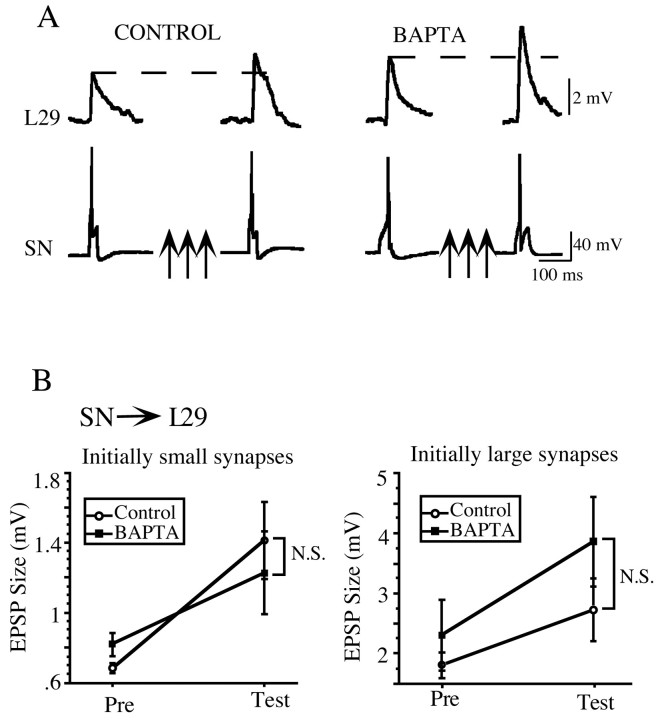

Having shown that there is a postsynaptic Ca2+ contribution to PTP at the SN–MN synapses, we next asked whether the SN required postsynaptic Ca2+ with other synaptic partners. To examine this question, we analyzed PTP at the SN–L29 synapse, which has the same presynaptic neuron as the SN–MN synapse but has a different postsynaptic target neuron. Figure4A illustrates representative traces from these experiments. The control synapse had an initial amplitude of 2.3 mV and facilitated to 3.7 mV, an increase of 155% of baseline. The BAPTA-loaded synapses showed a similar amount of enhancement, facilitating from 3 to 4.4 mV, an increase of 153% of baseline. Although the initial size of all of the SN–L29 synapses (0.67–3.5 mV) were within the range of the weak SN–MN synapses, which do use a postsynaptic Ca2+-dependent mechanism for PTP, we did not find a postsynaptic Ca2+ component of PTP at the SN–L29 synapse. Nonetheless, to ensure a comparable analysis with the SN–MN synapse, we divided the SN–L29 data set in half at the mean (1.35 ± 0.35 mV, mean ± SE) into weak and strong categories. As shown in Figure 4B, there were no statistically significant differences in the amount of PTP demonstrated by the control and BAPTA-loaded groups at either the initially weak (left) or initially strong (right) SN–L29 synapses. Initially weak synapses in control and BAPTA groups facilitated approximately the same amount, 178 and 154% of baseline, respectively (t(6) = 0.19; NS). Likewise, there was a similar magnitude of PTP induced at initially strong control synapses and initially strong synapses with postsynaptic BAPTA, at 147 and 171% of baseline, respectively (t(4) = 1.26; NS). These data show that the postsynaptic Ca2+ component of PTP seen at the SN–MN is not specific to the SN, because it does not seem to be a property of SN synapses onto all their target neurons.

Fig. 4.

PTP at the SN–L29 synapse was not affected by postsynaptic injection of BAPTA. A, Representative traces from control and BAPTA-loaded SN–L29 synapses. The two synapses showed a comparable magnitude of PTP, facilitating to ∼150% of baseline. B, Dividing the L29–MN data in half into initially weak and initially strong categories does not reveal a selective BAPTA effect as seen at initially weak SN–MN synapses. At initially weak L29–MN synapses (<1.4 mV; left), there was no significant difference in the magnitude of PTP induced at control (n = 3) and BAPTA-loaded (n = 5) synapses. At initially strong L29–MN synapses (>1.4 mV; right), the magnitude of PTP was the same at control (n = 3) and BAPTA-loaded (n = 3) synapses.

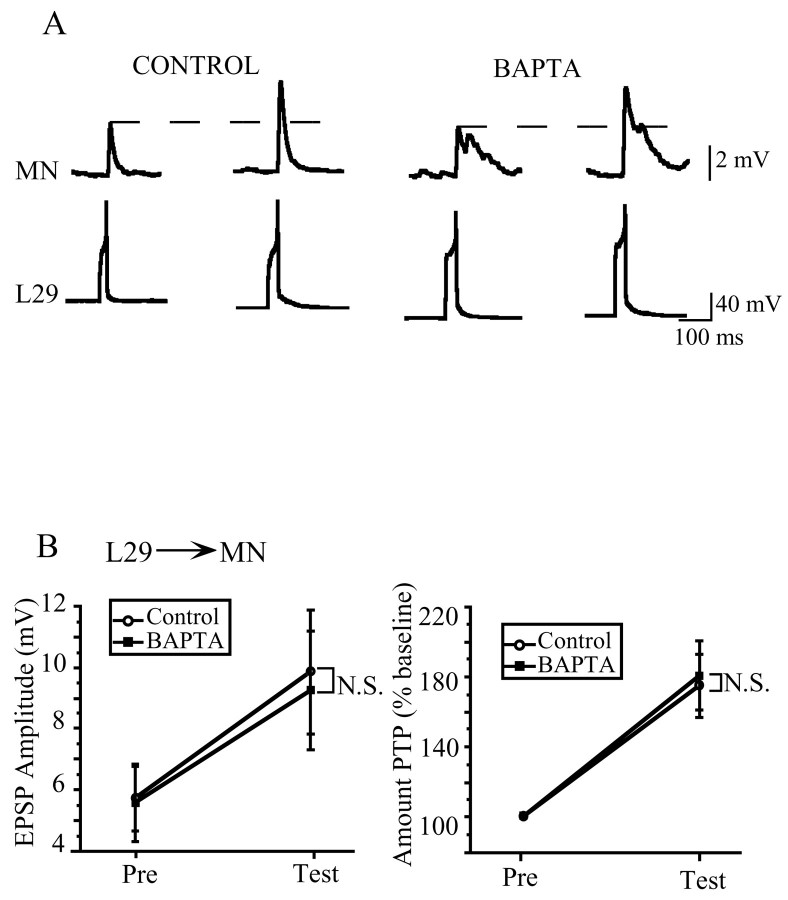

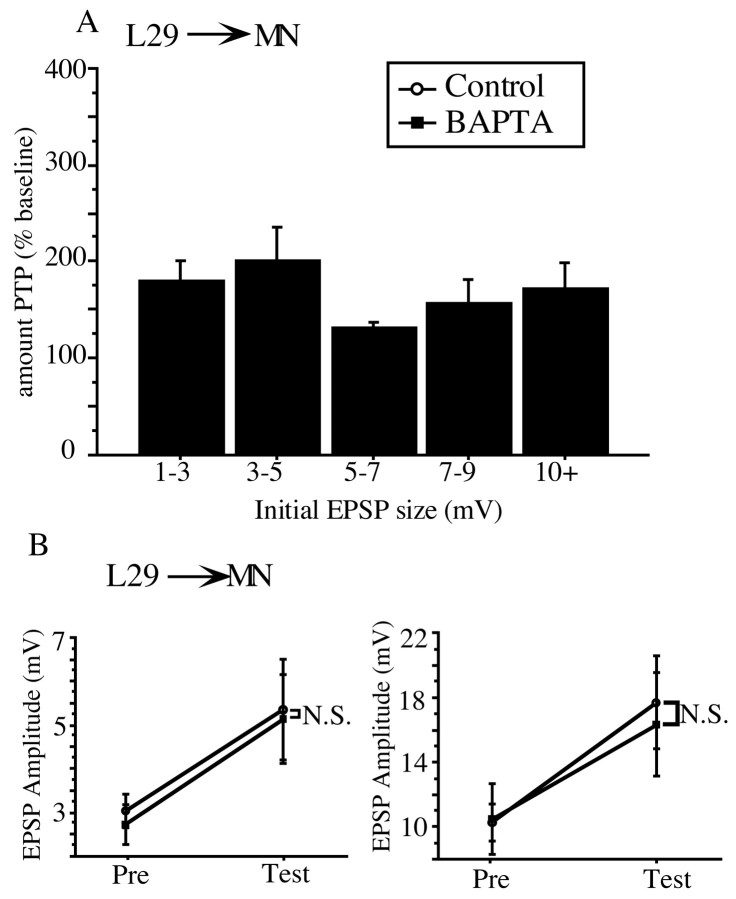

There is no postsynaptic Ca2+contribution to PTP at the L29–MN synapse

To examine the possibility that the postsynaptic Ca2+ component to PTP is specific to the MN, we investigated PTP at a synapse with the same postsynaptic target as the SN–MN synapse (the MN) but a different presynaptic input (the L29 interneuron). We found that postsynaptic BAPTA injection does not reduce the amount of PTP induced at the L29–MN synapse. Representative traces shown in Figure 5Aillustrate a typical result; the control and BAPTA-loaded synapses have comparable initial amplitudes, ∼3.5 mV, and both facilitate to ∼6.5 mV, an increase of ∼165% of baseline. Figure 5Billustrates the summary data, which revealed no significant difference between control and BAPTA-injected groups in the average amount of PTP induced at the L29–MN synapse (t(26)= 0.22; NS). Both groups facilitated to ∼175% of baseline. These data show that the postsynaptic Ca2+contribution to PTP at the SN–MN synapses is not specific to the MN, because the L29–MN synapse does not show the postsynaptic Ca2+ requirement for PTP that is seen at the SN–MN synapse. Thus, neither the SN nor the MN is uniquely responsible for the postsynaptic Ca2+contribution to PTP at the SN–MN synapse.

Fig. 5.

PTP at the L29–MN synapse was not affected by postsynaptic injection of BAPTA. A, Representative traces from control and BAPTA-loaded L29–MN synapses. The two synapses showed a comparable magnitude of PTP, facilitating to ∼170% of baseline. B, The summary data from the L29–MN experiments show that there was no significant reduction in the magnitude of PTP at BAPTA-loaded synapses (n = 15) compared with control synapses (n = 11).

Interestingly, the initial size range of L29–MN synapses is nearly identical to that seen at the SN–MN synapse (range of 1–15 mV for the L29–MN synapse compared with range of 1–16 mV for the SN–MN synapse). However, unlike the SN–MN synapse, there was no inverse relationship between initial size of the synapse and the amount of PTP induced at the L29–MN synapse. Whereas PTP at the SN–MN synapse shows an enhanced form of PTP at initially weak synapses (Fig.2A), PTP at the L29–MN synapse remains relatively constant (at 175%) across all size ranges (Fig.6A). In addition, the fact that PTP at the L29–MN is the same across all initial EPSP sizes lends additional support to the idea that the enhanced PTP induced at the weak SN–MN synapses is not merely a function of greater percent change from the weak baseline. If this were the case, one would expect to see the same exaggerated PTP at the initially weak L29–MN synapses (see Discussion). To quantitatively explore this issue, we analyzed the L29–MN data in exactly the same manner as the SN–MN data. We divided the L29–MN data set into two groups, divided at the mean of initial EPSP amplitude (5.1 ± 0.72 mV, mean ± SE). The results of this analysis are shown in Figure 6B. There was no reduction in PTP as a result of BAPTA injection into the MN at either the initially strong L29–MN synapses (t(8) = 0.88; NS) or the initially weak L29–MN synapses (t(16) = 0.141; NS). Together with the results from the SN–L29 experiments, these data show that not all initially weak synapses use a postsynaptic Ca2+-dependent process for PTP.

Fig. 6.

The amount of PTP induced at the L29–MN remains relatively constant across all initial EPSP sizes, unlike PTP at the SN–MN synapse. A, Weak L29–MN synapses do not show the enhanced amount of PTP seen at initially weak SN–MN synapses.B, Dividing the L29–MN data in half into initially weak and initially strong categories does not reveal a selective BAPTA effect. At initially weak L29–MN synapses (<5.1 mV;left), there was no significant difference in the magnitude of PTP induced at control (n = 10) and BAPTA-loaded (n = 9) synapses. At initially strong L29–MN synapses (>5.1 mV; right), the magnitude of PTP was the same for control (n = 5) and BAPTA-loaded (n = 6) synapses.

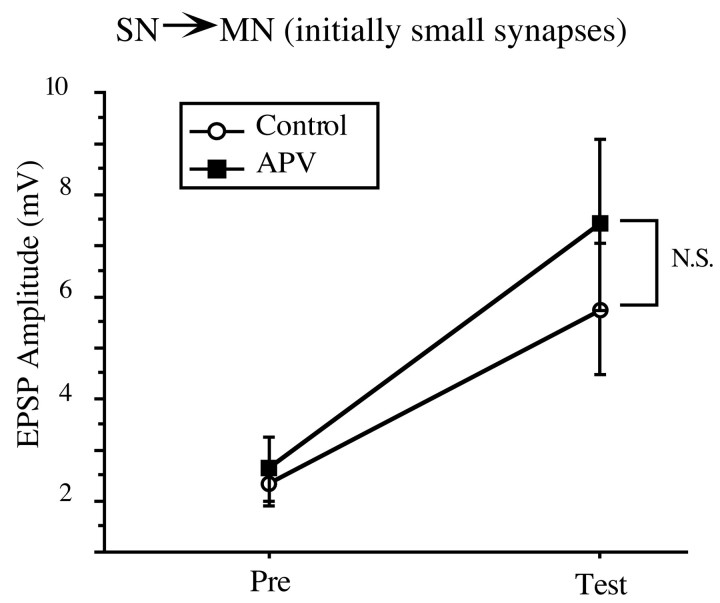

The postsynaptic Ca2+ component of enhanced PTP at the SN–MN synapse does not depend on NMDA receptor activation

Research examining LTP in both vertebrates and Aplysiahas shown that some postsynaptic effects can be mediated at least in part by NMDA receptor (NMDA-R)-dependent mechanisms (Bliss and Collingridge, 1993; Lin and Glanzman, 1994). In SN–MN cultures, the postsynaptic Ca2+ contribution to PTP at the SN–MN has been shown not to require NMDA-R activation (Koneko and Hawkins, 1998). To investigate the possibility that PTP in the intact ganglion might depend on the activation of NMDA-Rs, we compared the amount of PTP induced at initially weak SN–MN (<6.2 mV) synapses in the presence and absence of the NMDA-R antagonist APV. Our results are shown in Figure 7. At initially weak SN–MN synapses, there was no significant difference between the magnitude of PTP induced in the presence of APV compared with that induced in regular ASW (t(13) = 0.796; NS). In addition, all synapses displayed the expected enhanced form of PTP, facilitating to ∼300% of baseline. These results show that Ca2+ entry through NMDA-Rs does not contribute to the postsynaptic Ca2+component of the PTP we observe at initially weak SN–MN synapses.

Fig. 7.

The postsynaptic Ca2+contribution to PTP at the initially weak SN–MN synapses (<6.2 mV) does not depend on the activation of NMDA receptors. The magnitude of PTP induced at these synapses was the same in the presence of APV (n = 8) and the absence of APV (n = 8).

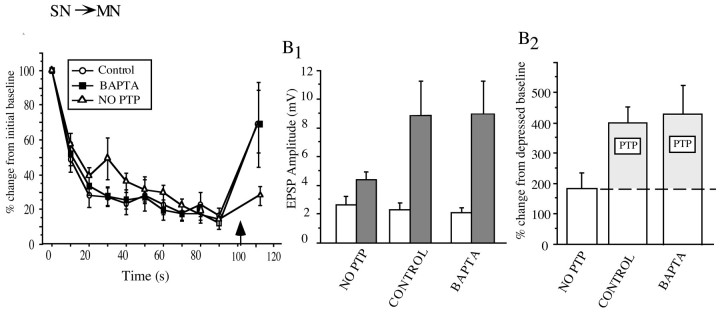

Inducing homosynaptic depression to reduce the size of initially strong SN–MN EPSPs does not confer BAPTA sensitivity to PTP

Results of our experiments at the SN–L29 and L29–MN synapses indicate that a synapse does not show postsynaptic BAPTA sensitivity simply by virtue of being initially weak. Instead, it seems that there is something unique about the initially weak SN–MN synapses that allows them to use, at least in part, a postsynaptic Ca2+-dependent process to achieve PTP. One possibility is that the strength of the SN–MN synapse just before PTP induction determines whether it can take advantage of postsynaptic Ca2+-dependent mechanisms. If this were the case, then it might be possible to confer BAPTA sensitivity on the initially strong SN–MN synapses by first depressing them into the size range of the initially weak synapses. There is strong precedent inAplysia for the notion that depressing an SN synapse engages different facilitatory mechanisms in response to 5-HT (Braha et al., 1990; Emptage et al., 1996; Sugita et al., 1997; see Discussion). We induced homosynaptic depression to reduce the initial strength of synapses that were in the size range of the BAPTA-insensitive group established in our previous PTP experiments (>6 mV) (Fig. 3B). After the synapses were depressed by means of repeated activation into the size range of the initially weak synapses (<6 mV) (Fig. 2A), we induced PTP and asked whether postsynaptic BAPTA injection affected the magnitude of that PTP.

As shown in Figure 8A, the BAPTA-loaded group and both control groups displayed nearly identical depression curves, with 75% of the depression occurring between the first and second activation and the leveling off to reach ∼10% of initial baseline by the 10th activation. When we examined PTP superimposed on this depressed baseline, we found that the control and BAPTA groups showed the same magnitude of PTP (Fig.8A,B1). In addition, both groups showed much greater enhancement than the group that did not receive a tetanus (No PTP). The weak enhancement in the No PTP group at the test point (112 sec) reflects modest recovery from synaptic depression. Figure8B2, which shows normalized data, provides an estimate of the magnitude of PTP at the SN–MN synapses that takes into account the recovery from depression between the last activation and the PTP test. The magnitude of PTP induced at depressed synapses was not affected by postsynaptic BAPTA injection (t(12) = 1.81; NS), indicating that depressing an initially strong EPSP does not confer BAPTA sensitivity to PTP at these synapses. Taken collectively, these results argue against the hypothesis that the initially weak SN–MN synapses simply reflect a state of homosynaptic depression. Rather, they suggest that the initially weak SN EPSP reflects a special status of the synapse that allows it to use, at least in part, a postsynaptic Ca2+ component of PTP.

Fig. 8.

A, Depressing initially strong SN–MN synapses into the size range of initially weak SN–MN synapses through repeated activation does not confer BAPTA sensitivity on the previously strong synapses. There was no significant difference between the amount of PTP induced at depressed control synapses (n = 6) and depressed BAPTA-loaded synapses (n = 7), although both groups were significantly different from the no tetanus condition (n = 7). The bold arrow indicates the time of SN tetanus.B1, Raw data are shown comparing the magnitude of change between the last pretest (white bars) and the 10 sec PTP test (gray bars) in the tetanized groups (control and BAPTA) with the unstimulated group. B2, To account for recovery from depression, PTP in the BAPTA and control groups was estimated as the amount of facilitation beyond the average magnitude of recovery in the group that did not receive any tetanus (No PTP).

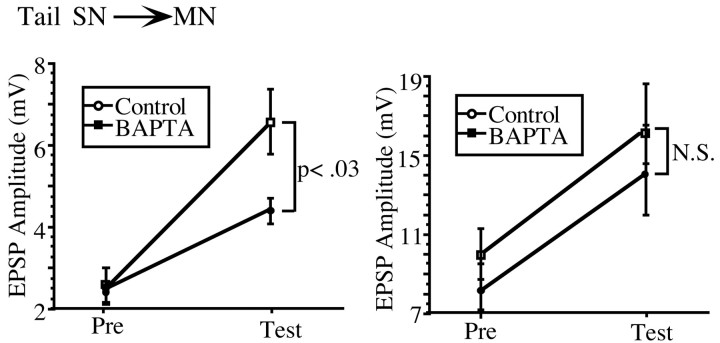

A BAPTA-sensitive component to PTP is evident at tail SN–MN synapses

Our experiments thus far indicate that a BAPTA-sensitive component to PTP is quite restricted within the SWR circuit, being evident only at a subset of siphon SN–MN synapses. A homologous set of SN–MN synapses exists in the neural circuit for tail withdrawal inAplysia (Walters et al., 1983a). These synapses exhibit several forms of short-term plasticity that are quite comparable with those exhibited by the siphon SN–MN synapses (Walters et al., 1983b). This then raises the following question: is the postsynaptic component of PTP that we have observed unique to the SN–MN synapses in the SWR, or is it a more general property of SN–MN synapses in other circuits in Aplysia? To explore this question, in a final series of experiments, we examined the BAPTA sensitivity of PTP at the tail SN–MN synapses in the pleural–pedal ganglia. We found that, just as in the siphon SN–MN synapses, there was a wide range of initial EPSP amplitudes. Moreover, the magnitude of PTP at these synapses was inversely proportional to the initial EPSP amplitude; weak EPSPs showed greater PTP than stronger synapses. As with the siphon SN–MN synapses, we divided the data set in half at the mean (mean, 5.2 mV). Our results are shown in Figure 9. Just as in the siphon SN–MN synapses, only the initially weak EPSPs exhibited a BAPTA-sensitive component of PTP. Initially weak tail SN–MN synapses in the control group showed pronounced PTP, facilitating to ∼285% of baseline, whereas initially weak BAPTA-loaded synapses showed significantly reduced PTP (t(15)= 2.4; p < 0.05), facilitating to 170% of baseline. At initially strong tail SN–MN synapses, there was no significant difference between BAPTA and control groups in the magnitude of PTP induced (t(11) = 0.77; NS). These data confirm and extend our previous findings at the siphon SN–MN synapses and suggest that a postsynaptic component of PTP may be a general feature of SN–MN synapses in Aplysia.

Fig. 9.

PTP at tail SN–MN synapses is identical to PTP at siphon SN–MN synapses. Initially weak tail SN–MN synapses (n = 17) show pronounced PTP that is reduced by 50% by postsynaptic BAPTA injection (left). PTP at initially strong tail SN–MN synapses (n = 13) was not affected by postsynaptic BAPTA injection (right).

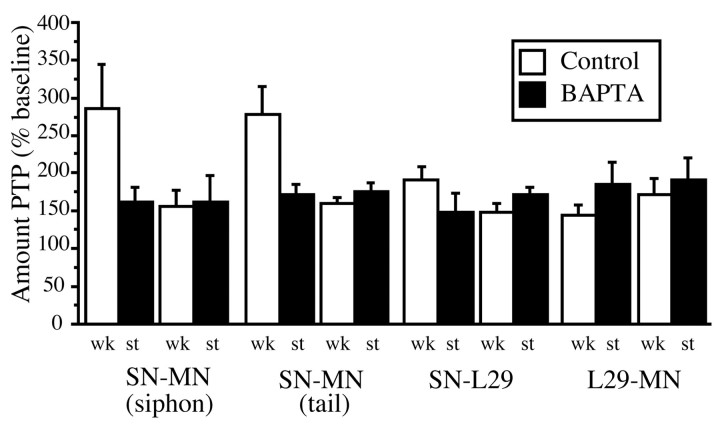

To directly compare the difference in the magnitude of PTP at all the synapses we have examined, as well as their BAPTA sensitivity, our results are shown in normalized form in Figure10. The data cast in this manner illustrate two key points. First, only initially weak SN–MN synapses (in both siphon and tail circuits) exhibit enhanced PTP (∼285% of baseline). All other synapses exhibit comparable PTP (∼160% of baseline). Second, only the initially weak SN–MN synapses display a BAPTA-sensitive postsynaptic component, which reduces the magnitude of their PTP to the range of all other synapses.

Fig. 10.

Normalized data from all synapses are shown. Of all of the synapses examined, only initially weak siphon and tail SN–MN synapses showed enhanced PTP that was reduced by postsynaptic BAPTA injection. The magnitude of PTP at initially strong SN–MN synapses, SN–L29 synapses, and L29–MN synapses was ∼50% of the PTP seen at initially weak SN–MN synapses, and there was no reduction in PTP with postsynaptic BAPTA injection. Note also that postsynaptic BAPTA reduced PTP in the SN–MN synapses to the level of all other synapses.

DISCUSSION

Postsynaptic Ca2+ contributions to PTP at the SN–MN synapse

Our data reveal three important features of PTP at the SN–MN synapse. First, within the synapses we have sampled in the SWR circuitry, the postsynaptic Ca2+ component of PTP does not extend beyond the SN–MN synapse (Fig.11). It is not a general property of all SN synapses or all synapses onto the MN, but rather is a unique mechanism specific to the SN–MN synapse. Second, our results show that the postsynaptic Ca2+ component to PTP at the SN–MN synapse is only expressed at initially weak synapses; initially strong SN–MN synapses show no postsynaptic Ca2+ component of PTP. Third, initially weak SN–MN synapses appear to display an “enhanced” form of PTP compared with all other synapses we examined. Together, these observations suggest the hypothesis that the postsynaptic Ca2+ contribution to PTP at initially weak tail and siphon SN–MN synapses provides an additional component of facilitation that combines with presynaptically mediated PTP, giving rise to an enhanced form of PTP at these synapses (Fig. 11). It will be of interest to explore the generality of this hypothesis at other synaptic sites within the SWR.

Fig. 11.

A, The SWR and tail withdrawal circuits are shown with the involvement of postsynaptic Ca2+ indicated at each synaptic site. At the SN–MN synapses, only initially weak synapses use a postsynaptic Ca2+-dependent mechanism for PTP (weak; black triangle). Initially strong SN–MN synapses, SN–L29 synapses, L29–MN synapses, and L30–L29 synapses do not use postsynaptic Ca2+ for PTP (all shown as white synapses). The triangles represent an excitatory synapse, and the circles represent an inhibitory synapse. B, A model is shown that proposes that, within the SWR, synapses that appear to use only presynaptic mechanisms for facilitation all show a similar magnitude of PTP (∼160% of baseline), but the initially weak SN–MN synapses can engage a postsynaptic mechanism that combines with the presynaptically induced facilitation to yield an enhanced form of PTP.

It could be argued that the inverse relationship between initial size of the EPSP and the magnitude of PTP induced at the SN–MN synapse is the result of an upper limit on the amount of PTP possible, so that the strongest SN–MN synapses encounter a ceiling that prevents them from facilitating to the same extent as the weakest synapses. Two lines of evidence argue against this interpretation. First, one would expect strong SN–MN synapses that were depressed into the size range of initially weak synapses before SN tetanus would show a magnitude of PTP that was comparable with that seen at initially weak SN–MN synapses. However, this was not the case. Second, the enhanced form of PTP at the initially weak SN–MN synapses is not a result of the small initial baseline yielding a greater percent change, because one would also expect that the initially weak SN–L29 and L29–MN synapses would also show a greater amount of PTP compared with their stronger counterparts.

Experiments to determine whether the postsynaptic Ca2+ dependency at the SN–MN synapse is specific to the SN or specific to the MN showed that neither the SN nor the MN requires postsynaptic Ca2+ for PTP with other synaptic partners. PTP at the SN–L29 and L29–MN synapses was not affected by BAPTA injection into the postsynaptic cell. Thus, the postsynaptic Ca2+ contribution to PTP at the SN–MN synapse is not unique to the SN or MN alone. Rather, it appears to be a unique property of the SN–MN synapse that, at least in cases in which the synapse is initially weak, allows it to engage a postsynaptic Ca2+-dependent mechanism for PTP.

Interestingly, similar findings concerning the selective postsynaptic Ca2+ dependency of initially weak synapses have been reported recently by Wan and Poo (1999). At the developing neuromuscular junction in Xenopus oocytes, they found that persistent, activity-dependent facilitation required postsynaptic Ca2+ when the synapses were initially weak (<1.5 nA) but not when the synapses were initially strong (>1.5 nA). They also found an inverse relationship between initial size of the synaptic potential and the magnitude of the potentiation induced. In this system, postsynaptic Ca2+ appears to be released from internal Ca2+ stores, because loading of the postsynaptic myocyte with Runthenium Red to block internal Ca2+ release blocked induction of potentiation. The similarity of Wan and Poo's results to the present findings in Aplysia suggests the possibility that Ca2+ release from internal stores in the MN may contribute to PTP at the initially weak SN–MN synapses.

The surprising result that only the initially weak SN–MN synapses use a postsynaptic mechanism for PTP led us to consider whether the availability of the postsynaptic Ca2+component corresponds to a particular functional state of the SN–MN synapse. Specifically, we questioned whether weak synapses might actually reflect synapses in a depressed state and whether that state might allow the weak SN–MN synapses to take advantage of postsynaptic Ca2+-dependent processes for PTP. There is strong precedent for this possibility; several studies have shown that homosynaptically depressed SN–MN synapses use different mechanisms for facilitation induced by serotonin than nondepressed synapses (Braha et al., 1990; Emptage et al., 1996; Sugita et al., 1997) (for review, Byrne and Kandel, 1996). Interestingly, our results show that inducing homosynaptic depression at the SN–MN synapse does not engage a postsynaptic Ca2+ component of PTP, because BAPTA injection in the MN at initially strong (and then depressed) synapses does not affect the magnitude of PTP induced. Thus, it appears that the state dependency of the postsynaptic Ca2+ mechanism is not a result of simple depression at the SN–MN synapse, but this finding does not preclude the possibility that some aspect of the synaptic activation history of the SN–MN synapse may determine whether postsynaptic Ca2+ processes contribute to PTP.

A related observation in Aplysia is relevant to the issue of initial EPSP size and subsequent facilitation. Recently, Jiang and Abrams (1998) have shown that paired-pulse facilitation (PPF) at SN–MN synapses is considerably greater when the initial EPSP amplitude is small compared with PPF at initially larger EPSPs. Furthermore, Jiang and Abrams also found that depressing an initially strong SN–MN synapse into the size range of the initially weak ones did not increase the magnitude of PPF. These results are quite similar to those we obtained, and collectively suggest two conclusions. First, it is unlikely that initially weak SN–MN EPSPs simply reflect a previously existing state of homosynaptic depression. Second, when considered with the recent findings of Wan and Poo (1999) discussed above, there are now several instances in which there is a clear inverse relationship between the initial EPSP size and subsequent facilitation.

NMDA receptors have been strongly implicated in Ca2+-dependent postsynaptic mechanisms of plasticity in the CNS. In cultured SN–MN synapses, NMDA-Rs do not appear necessary for PTP, because APV application fails to block induction of PTP at these synapses (Kononenko and Hawkins, 1998). Our results are consistent with this observation and suggest that NMDA-R activation is not required for PTP at the SN–MN synapse. Thus, although the SN–MN synapse of Aplysia uses postsynaptic Ca2+-dependent processes for both LTP and PTP, the mechanisms of Ca2+elevation involved in these two forms of plasticity appear to be different.

One important question concerns the source of the postsynaptic Ca2+ involved in PTP at the SN–MN synapse. Postsynaptic Ca2+ could come from extracellular Ca2+ entering the MN through one of several types of Ca2+ channels, from internal stores within the MN or from a combination of these sources. It is unlikely that the Ca2+enters the MN through NMDA channels for the reasons discussed above. Several other studies examining the SN–MN synapses in culture have shown that strong hyperpolarization of the MN during tetanus reduces the magnitude of PTP at the SN–MN synapse (Cui and Walters, 1994; Lin and Glanzman 1994, Bao et al., 1997), which suggests that postsynaptic Ca2+ may enter through voltage-sensitive channels. In our experiments in the intact CNS, it would be surprising if the postsynaptic Ca2+ involved in PTP at the SN–MN synapses enters the MN through voltage-gated channels, because it is the weaker synapses that use the postsynaptic mechanism.

Presynaptic mechanisms alone cannot produce enhanced PTP

It is interesting to note that, at the same frequency of stimulation, the magnitude of the PTP is quite comparable at all synapses we sampled in the SWR circuit in which PTP seems to be independent of postsynaptic Ca2+ (Fig.10). Specifically, PTP was ∼160% of baseline for (1) the SN–L29 synapse, (2) the L29–MN synapse, (3) the initially strong SN–MN synapses, and (4) the initially strong (then depressed) SN–MN synapses. In contrast, initially weak siphon and tail SN–MN synapses, which do exhibit a postsynaptic Ca2+component of PTP, display an enhanced amount of PTP, facilitating to ∼285% of baseline. Postsynaptic BAPTA injections reduce the amount of PTP induced at initially weak SN–MN synapses to ∼160% of baseline, a magnitude that is in register with the amount of PTP generated at the other SWR synapses (Fig. 10). These observations suggest the hypothesis that, at weak siphon and tail SN–MN synapses, the postsynaptic Ca2+ component of PTP provides additional enhancement that is combined with the potentiation induced presynaptically (Fig. 11B).

Although the model illustrated in Figure 11B supports this hypothesis, other possibilities remain. For example, it is also possible that the initially weak SN–MN synapses are actively decreased in amplitude through a mechanism that is not shared by other synapses in the SWR circuit, and this mechanism is reversed by the influx of postsynaptic Ca2+ during PTP. In the limit, it is possible that all synapses in the SWR circuit undergo a rise in postsynaptic Ca2+ during PTP, but this postsynaptic Ca2+ influx may not have detectable effects if synaptic strength is not first reduced in amplitude via the mechanism expressed at initially weak SN–MN synapses. Moreover, it is not clear at this point whether the postsynaptic Ca2+ processes can exist independently from presynaptic mechanisms. Presynaptic activation may be required for the induction of postsynaptic Ca2+ processes. Alternatively, it may be that any rise in postsynaptic Ca2+ can enhance initially weak SN–MN synapses or at least lower the presynaptic activation requirements for PTP at these synapses. Finally, we have sampled only a small subset of all possible synapses from SNs onto their followers and from other (non-SN) inputs onto the MNs. Additional experiments may reveal other cases of postsynaptic Ca2+ contributions to PTP.

Functional significance of a postsynaptic Ca2+ component of PTP at the SN–MN synapse

What does this novel mechanism of facilitation functionally contribute to circuit dynamics, synaptic plasticity, and ultimately, to the animal's behavior? There are several possible benefits of a selective postsynaptic Ca2+ contribution to PTP that is restricted to specific subsets of SN synapses. For example, the output of a single SN need not be identical across all of its branches: some branches may give rise to an initially weak EPSP, whereas other branches could produce a stronger EPSP. This could allow the system to take uniform sensory input and transform it into selective enhancement of some synapses over others. In this manner, it might be possible to restrict the augmented form of PTP to specific branches of a single presynaptic neuron. Such a differential enhancement could contribute to selective activation of one neuronal pathway over another. Similarly, it may be possible to increase synaptic efficacy between particular SNs and specific MNs, allowing for preferential activation of particular motor pathways by a subset of sensory inputs. In addition, it is possible that one SN connection onto an MN could “inherit” the postsynaptic Ca2+ derived from another neighboring SN onto the same MN that had recently undergone PTP. This raises the potential for a Hebb-like association (Bonhoeffer et al., 1989;Schuman and Madison, 1994) between two SNs and their follower MN, which could provide a mechanism for generalization of a single input signal across multiple neuronal pathways.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institute of Mental Health Grant 5R01 MH 48672-04-06 (to T.J.C.). We thank Carolyn Scherff for helpful comments on an earlier version of this manuscript.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Thomas Carew, Department of Neurobiology and Behavior, University of California at Irvine, Irvine, CA 92697-4550. E-mail: tcarew@uci.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bao JX, Kandel ER, Hawkins RD. Involvement of pre-and postsynaptic mechanisms in posttetanic potentiation at Aplysia synapses. Science. 1997;275:969–973. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5302.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bekker JM, Stevens CF. Presynaptic mechanism for long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. Nature. 1990;346:724–729. doi: 10.1038/346724a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bliss TVP, Collingridge GL. A synaptic model of memory: long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. Nature. 1993;361:31–39. doi: 10.1038/361031a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonhoeffer T, Staiger V, Aertsen A. Synaptic plasticity in rat hippocampal slice cultures: local “Hebbian” conjunction of pre- and postsynaptic stimulation leads to distributed synaptic enhancement. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:8113–8117. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.20.8113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braha O, Dale N, Hochner B, Klein M, Abrahms TW, Kandel ER. Second messengers involved in the two processes of presynaptic facilitation of the sensory-motor synapse of Aplysia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:2040–2044. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.5.2040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Byrne JH, Kandel ER. Presynaptic facilitation revisited: state and time dependence. J Neurosci. 1996;16:425–435. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-02-00425.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buonomano DV. Decoding temporal information: a model based on short-term synaptic plasticity. J Neurosci. 2000;20:129–141. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-03-01129.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cui M, Walters ET. Homosynaptic LTP and PTP of sensorimotor synapses mediating the tail withdrawal reflex in Aplysia are reduced by postsynaptic hyperpolarization. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 1994;20:1071. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delaney KR, Tank DW. A quantitative measurement of the dependence of short-term synaptic enhancement of presynaptic residual calcium. J Neurosci. 1994;14:5885–5902. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-10-05885.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Emptage NJ, Mauelshagen J, Carew TJ. Threshold serotonin concentration required to produce synaptic facilitation differs for depressed and non-depressed synapses in Aplysia sensory neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1996;75:843–854. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.75.2.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fischer TM, Carew TJ. Activity-dependent recurrent inhibition: a mechanism for dynamic gain control in the siphon withdrawal reflex of Aplysia. J Neurosci. 1995;13:1302–1314. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-03-01302.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fischer TM, Zucker RS, Carew TJ. Activity-dependent potentiation of synaptic transmission from L30 inhibitory interneurons of Aplysia depends on residual presynaptic Ca2+but not on postsynaptic Ca2+. J Neurophysiol. 1997;22:2061–2071. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.4.2061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fisher SA, Fischer TM, Carew TJ. Multiple, over-lapping processes underlying short-term synaptic enhancement. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20:170–177. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)01001-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerstner W, Abbott LF. Learning navigational maps through potentiation and modulation of hippocampal place cells. J Comp Neurosci. 1997;1:79–94. doi: 10.1023/a:1008820728122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang Y-Y, Li X-C, Kandel ER. cAMP contributes to mossy fiber LTP by initiating both a covalently-mediated early phase and a macro-molecular synthesis dependent late phase. Cell. 1994;79:69–79. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90401-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang XY, Abrams TW. Use-dependent decline of paired-pulse facilitation at Aplysia sensory neuron synapses suggest a distinct vesicle pool or release mechanism. J Neurosci. 1998;18:10310–10319. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-24-10310.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamiya HZ, Zucker RS. Residual Ca2+ and short-term synaptic plasticity. Nature. 1994;371:603–606. doi: 10.1038/371603a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kononenko N, Hawkins RD. PTP at Aplysia sensory-motor neuron synapses in isolated cell culture does not involve NMDA receptors or nitric oxide signaling. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 1998;24:1189. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larkman A, Hannay T, Stratfosel K, Jack T. Presynaptic release probability influences the locus of long-term potentiation. Nature. 1992;360:70–73. doi: 10.1038/360070a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin XY, Glanzman DL. Long-term potentiation of Aplysia sensorimotor synapse in cell culture: regulation by postsynaptic voltage. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1994;255:113–118. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1994.0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lynch G, Larson J, Kelso S, Barrionuevo G, Schottler F. Intracellular injections of EGTA block induction of hippocampal long-term potentiation. Nature. 1983;305:719–721. doi: 10.1038/305719a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malenka RC, Nicoll RA. LTP: a decade of progress? Science. 1999;285:1870–1874. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5435.1870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malenka RC, Kauer JA, Nicoll RA. The impact of postsynaptic calcium on synaptic transmission-its role in long-term potentiation. Trends Neurosci. 1989;12:444–450. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(89)90094-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nicoll RA, Malenka RC. Contrasting properties of two forms of long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. Nature. 1995;377:115–118. doi: 10.1038/377115a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Regehr WG, Delaney KR, Tank DW. The role of presynaptic calcium in short-term enhancement at the hippocampal mossy fiber synapse. J Neurosci. 1994;14:523–537. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-02-00523.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schaffhausen JH, Carew TJ. An analysis of postsynaptic contributions to PTP at sensory-motor synapses in Aplysia. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 1999;25:863. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schaffhausen JH, Fischer TM, Carew TJ. Contribution of postsynaptic Ca2+ to the induction of PTP in the neural circuit for siphon withdrawal. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 1998;24:701. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-05-01739.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schuman EM, Madison DV. Communication of synaptic potentiation between synapses of the hippocampus. Adv Second Messenger Phosphoprotein Res. 1994;29:507–520. doi: 10.1016/s1040-7952(06)80032-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sugita S, Baxter DA, Byrne JH. Differential effects of 4-aminopyridine, serotonin, and phorbol esters on facilitation of sensorimotor connections in Aplysia. J Neurophysiol. 1997;77:172–185. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.1.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walters ET, Byrne JH, Carew TJ, Kandel ER. Mechanoafferent neurons innervating the tail of Aplysia. I. Response properties and synaptic connections. J Neurophysiol. 1983a;50:1522–1542. doi: 10.1152/jn.1983.50.6.1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walters ET, Byrne JH, Carew TJ, Kandel ER. Mechanoafferent neurons innervating the tail of Aplysia. II. Modulation by sensitizing stimulation. J Neurophysiol. 1983b;50:1543–1559. doi: 10.1152/jn.1983.50.6.1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wan JJ, Poo MM. Activity-induced potentiation of developing neuromuscular synapses. Science. 1999;285:1725–1728. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5434.1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zucker RS. Short-term synaptic plasticity. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1989;12:13–31. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.12.030189.000305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]