Abstract

Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) are required for numerous forms of neuronal plasticity, including long-term potentiation (LTP). We induced LTP in rat hippocampal area CA1 using theta-pulse stimulation (TPS) paired with β-adrenergic receptor activation [isoproterenol (ISO)], a protocol that may be particularly relevant to normal patterns of hippocampal activity during learning. This stimulation resulted in a transient phosphorylation of p42 MAPK, and the resulting LTP was MAPK dependent. In addition, CaMKII was regulated in two, temporally distinct ways after TPS–ISO: a transient rise in the fraction of phosphorylated CaMKII and a subsequent persistent increase in CaMKII expression. The increases in MAPK and CaMKII phosphorylation were strongly colocalized in the dendrites and cell bodies of CA1 pyramidal cells, and both the transient phosphorylation and delayed expression of CaMKII were prevented by inhibiting p42/p44 MAPK. These results establish a novel bimodal regulation of CaMKII by MAPK, which may contribute to both post-translational modification and increased gene expression.

Keywords: long-term potentiation, mitogen-activated protein kinase, Erk, Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II, β-adrenergic receptors, rat hippocampus, phosphorylation, protein synthesis

Mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) are components of a phosphorylation cascade that is activated in hippocampal neurons by synaptic stimuli, including growth factors and glutamate, and the importance of MAPKs in relatively long-term processes such as the regulation of gene expression and cellular remodeling is well established (Chang and Karin, 2001). Some of these effects are thought to reflect MAPK-dependent activation of transcription factors, along with an increasingly appreciated regulation of translational efficiency (Grewal et al., 1999). Recently, evidence has pointed to a role of MAPK in a relatively rapid and localized phenomenon, long-term potentiation (LTP). LTP is a use-dependent increase in synaptic efficiency that is widely studied as a model for associative memory (Bliss and Collingridge, 1993; Malenka and Nicoll, 1999). The expression of LTP can be divided into two stages: early LTP (E-LTP), which lasts <2 hr and does not require ongoing protein synthesis, and a later stage (L-LTP), which is sensitive to blockers of transcription and translation. MAPK is transiently activated by stimuli that induce LTP at the CA3–CA1 synapse in hippocampus, and blockers of the MAPK pathway interfere with LTP as well as behavioral memory (English and Sweatt, 1997; Atkins et al., 1998; Impey et al., 1998; Winder et al., 1999; Davis et al., 2000). Surprisingly, MAPK activity is necessary even for the expression of E-LTP, suggesting a role of MAPK in post-translational processes underlying LTP induction or maintenance. MAPK may participate in both stages of LTP, first by modifying existing proteins that determine synaptic behavior, and subsequently by regulating the expression of proteins necessary for the maintenance of synaptic changes.

Within minutes after LTP-inducing stimulation, a fraction of cellular MAPK translocates from the cytosol into the nucleus (Davis et al., 2000), where it can alter gene expression by transcriptional control (Xia et al., 1996; Impey et al., 1998). However, the MAPK remaining in the dendrites is also extensively phosphorylated (Impey et al., 1998;Winder et al., 1999), and extranuclear substrates for MAPK have been identified that include components of the postsynaptic signaling network (Muthalif et al., 1996; Chen et al., 1998; Kim et al., 1998). The subcellular distribution of p42-MAPK in hippocampal neurons, with similar expression in dendrites and cell bodies, is consistent with combined cytosolic and nuclear effects of MAPK (Flood et al., 1998). Recently, the postsynaptic density has been shown to include p42 MAPK, the kinase that phosphorylates it, and a phosphatase that inactivates it (Husi et al., 2000). Together, these findings are consistent with the MAPK pathway interacting with LTP signaling pathways through a local synaptic mechanism.

Here, we describe the MAPK-dependent regulation of a central protein in neuronal plasticity, Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII), after the induction of LTP by a protocol that may be particularly relevant to normal patterns of activity at the CA3–CA1 synapse during learning (Thomas et al., 1996; Brown et al., 2000). Our major finding is that MAPK mediates two temporally distinct processes: an early and transient phosphorylation of CaMKII, followed by a sustained increase in CaMKII expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Electrophysiology

Hippocampal slices (400 μm thick) were prepared from male Sprague Dawley rats (125–200 gm) and maintained in an interface chamber. For recording, the slices were transferred to a submersion chamber, where they were superfused at 30-31°C with artificial CSF (ACSF) containing (in mm): 118 NaCl, 3.5 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 1.3 MgSO4, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 24 NaHCO3, and 15 glucose, bubbled with 95% O2/5% CO2. Drugs were either applied in the interface maintenance chamber (preincubation) or introduced into the superfusate while recording. Monophasic, constant-current stimuli (100 μsec) were delivered with a bipolar electrode (F. Haer, Bowdoinham, ME), and the EPSP was monitored in CA1 either by field recording in stratum radiatum (2 m NaCl,Re = 1–3 MΩ) or intracellular recording in stratum pyramidale (3 m KCl,Re = 50–90 MΩ). The EPSP was monitored by stimuli delivered at 0.033 Hz, and the signals were low-pass filtered at 3 kHz and digitized at 20 kHz. EPSP amplitude and slope (measured as the maximum slope in any 1 msec window during the rising phase of the EPSP) were calculated on-line using an Axobasic routine (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA). LTP was induced in area CA1 by applying 1 μm isoproterenol (ISO) in the bath for 10 min, followed by theta-pulse stimulation (TPS; 150 pulses at 10 Hz) of the Schaffer collaterals (stratum radiatum in area CA3). ISO was washed out immediately after TPS. The stimulus intensity used for TPS was adjusted to initially produce an EPSP of 1.0–1.5 mV for field recording, and 20–25 mV from −80 mV for intracellular experiments. Bath-applied drugs were dissolved in ACSF and added to the maintenance chamber (for preincubation) or to the superfusate in the recording chamber. PD98059 was applied in the maintenance chamber in ACSF containing 0.1% DMSO, and controls for these experiments were preincubated in the same vehicle. Inhibitor-1 was dissolved in 3m KCl and applied in the intracellular electrode for 40 min before TPS–ISO stimulation. All slices used for subsequent immunoblotting or immunohistochemistry were harvested at least 3 hr after slice preparation, when background phospho-MAPK levels are low (Winder et al., 1999). Each experiment included two control groups: unstimulated controls (harvested directly from the interface chamber) and sham-stimulated controls (placed in the recording chamber and subjected to test stimuli only). In some experiments, sham-stimulated controls were harvested at times corresponding to 2, 15, and 60 min after TPS delivery in associated stimulated slices. No significant differences were observed between these groups, and they were pooled for the purposes of statistical analysis.

Western immunoblotting

TPS–ISO-treated slices were removed from the recording chamber at 2, 15, and 60 min after the end of stimulation and immediately frozen on dry ice. The CA1 region was microdissected along the three cuts shown in Figure 1A, transferred to cold microcentrifuge tubes, and kept at −20°C for not more than 2–3 d before assaying. Care was taken to ensure that the slices remained frozen throughout the procedure. Sham-stimulated slices were removed at the corresponding times and controls were harvested directly from the interface maintenance chamber, and the CA1 regions were isolated as above. All Western analyses were performed blind to the tissue stimulation conditions. Fifty microliters of ice-cold lysis buffer were added to each tube, and CA1 regions were homogenized on ice using a motorized Potter-Elvehjem homogenizer directly in the Eppendorf tube (15 strokes, 1 stroke per second). The lysis buffer had the following composition (in mm, unless indicated otherwise): 50 Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 50 NaCl, 10 EGTA, 5 EDTA, 2 sodium pyrophosphate, 4 para-nitrophenylphosphate, 1 sodium orthovanadate, 1 phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 25 sodium fluoride, 2 DTT, 1 μm okadaic acid, 1 μmmicrocystin L-R, 20 μg/ml leupeptin, and 4 μg/ml aprotinin. Immediately after homogenization an additional 2.5 μl of PMSF was added to each tube, and protein determination was performed using Bio-Rad Protein Assay reagent (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

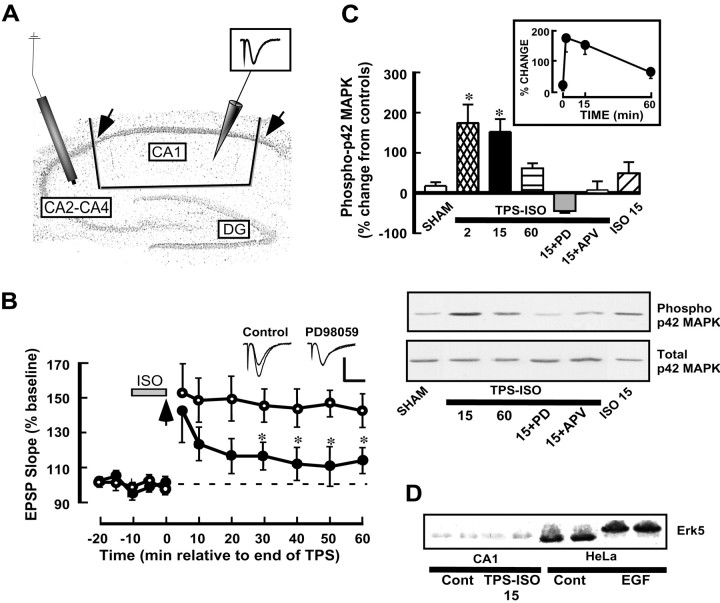

Fig. 1.

MAPK participates in TPS–ISO-induced LTP. A, Nissl-stained unstimulated hippocampal slice showing the positioning of the stimulating (left) and recording (right) electrodes and the cuts used to excise the CA1 region. Thearrows indicate the boundaries of the CA1 region, for the purpose of counting cell bodies. B, MAPK activity is required for LTP induced by TPS–ISO. Isoproterenol (1 μm) was applied to the bath for 10 min, followed by theta pulse stimulation of the Schaffer collaterals (TPS; 150 pulses at 10 Hz). TPS–ISO-induced LTP persisted for at least 60 min after the end of stimulation (○; n = 5). In slices preincubated with PD98059 (50 μm), the maintenance of TPS–ISO LTP was blocked (●; n = 6).Asterisks indicate group differences with p < 0.05 (Newman–Keuls multiple comparison test). The superimposed traces show representative field EPSPs before TPS–ISO and 60 min after stimulation. Additional experiments showed a similar inhibition of LTP by pretreatment with 30 μm PD98059 [LTP at 60 min: 142 ± 27 in controls (n = 3) and 117 ± 13 in treated slices (n = 3); p< 0.05], in contrast to the previous findings with HFS-induced LTP (Liu et al., 1999). Calibration: 0.5 mV, 5 msec. C, TPS–ISO increases p42 MAPK phosphorylation in area CA1 of the hippocampus. The bar graph summarizes immunoblot data and shows the levels of phospho-(Thr202/Tyr204)-p42 MAPK normalized to total MAPK in each CA1 region and expressed as percentage of paired, untreated control slices. 2, 15, and60 indicate minutes after stimulation. Significant differences from sham-stimulated slices are indicated by theasterisks (p < 0.05). PD98059 (PD) was applied at 50 μm in the maintenance chamber, and aminophosphonovaleric acid (APV) was applied in the recording chamber at 100 μm for 10 min before stimulation). ISOindicates slices exposed to 1 μm isoproterenol alone for 10 min. The inset shows the time course of MAPK phosphorylation after TPS–ISO stimulation. An immunoblot, from a single experiment, of phospho-p42 MAPK (top panel) and total-p42 MAPK (bottom panel) is shown below. D, TPS–ISO does not phosphorylate Erk5. The immunoblot, probed for Erk5 immunoreactivity, was run with homogenates from hippocampal area CA1 (4 lanes on the left) and HeLa cells (4 lanes on the right). Within each type of tissue, the two lanes on the left are from untreated controls, whereas the two lanes on theright are from stimulated tissue (TPS–ISO, 15 min after stimulation for CA1 and 15 min of 1 ng/ml EGF for HeLa cells). Erk5 from EGF-stimulated HeLa cells shows a clear mobility shift, indicative of increased phosphorylation, but no shift occurred in stimulated hippocampus.

An appropriate volume of 6× loading buffer was added to the homogenates, and samples were boiled for 5 min. Samples (30 μg of proteins per well) were loaded on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel and resolved by standard electrophoresis. The gels were then transferred electrophoretically onto nitrocellulose membrane (Hybond-C extra; Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL) using a transfer tank kept at 4°C, with typical parameters being 2 hr with a constant current of 400 mA. Membranes were blocked for 1 hr at room temperature with blocking buffer (BB), 5% non fat dry milk in PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-T), then probed overnight at 4°C using primary antibodies for phospho-(Thr202/Tyr204)-p42 MAPK (rabbit polyclonal, 1:2000; New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA), phospho-(Thr286)-CaMKII (mouse monoclonal, 1:1000; ABR, Golden, CO or Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY) or Bmk1/Erk5 (rabbit polyclonal, 1:250; Upstate Biotechnology). All primary antibodies were dissolved in BB. After washing in PBS-T (three washes, 15 min each), the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG (1:5000; Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN), and proteins were visualized using chemiluminescence (Amersham ECL Western Blotting Analysis System). Membranes were then stripped by strong agitation with 0.2N NaOH (15 min, room temperature), blocked in BB for 1 hr at room temperature, and probed overnight at 4°C using antibodies for total p42/p44 MAPK (1:2000; NEB), total CaMKII (1:1000;Chemicon, Temecula, CA), or actin (1:1000; Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Densitometric analysis of the bands was performed by means of a Molecular Dynamics Personal Densitometer SI (Sunnyvale, CA) using ImageQuant Software. Digital resolution was set at 12 bits per pixel, with a 50 μm pixel size. Phospho-p42 MAPK and phospho-CaMKII values were normalized to total p42 MAPK and either actin or total CaMKII, respectively, and total CaMKII was normalized to actin.

HeLa cell culture and treatment

HeLa cells were grown in 10% FBS/DMEM/penicillin–streptomycin using standard methods. Cells were starved for 18 hr before induction with epidermal growth factor (EGF) to reach 75% confluence in 60 mm culture dishes. Bmk1/Erk5 was stimulated using 1 ng/ml EGF (Upstate Biotechnology). Cells were harvested 15 min after induction. Control cells did not receive EGF. Cells were resuspended in 200 μl of the lysis buffer described above, scraped, shaken at 4°C for 20 min, centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C, assayed for protein content, and processed for electrophoresis and Western immunoblot as described above. Forty microliters of protein were loaded per lane on 8% SDS-PAGE gels. Bmk1/Erk5 activation was detected by gel mobility shift as described previously (Kato et al., 1998).

Conventional immunohistochemistry

Day 1. At 2, 15, and 60 min after the end of stimulation, TPS–ISO-treated, sham-stimulated, and control slices were immediately put in ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde/0.1% glutaraldehyde in PBS, pH 7.4, and fixed overnight. The slices were then washed for 2–3 hr in PBS and sectioned into 40 μm slices using a Vibratome (Lancer, Bridgeton, MO). Free-floating sections were rinsed for 10 min in PBS–0.3% Triton X-100 (PBS-TX), incubated for 15 min in PBS-TX containing 0.75% H2O2, rinsed three times with PBS-TX (10 min each), and blocked with 10% normal goat serum in PBS-TX (PBS-TX-NGS) for 40 min. Sections were then incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies [rabbit polyclonal raised against either phospho-(Thr202/Tyr204)-MAPK (1:750) or total MAPK (1:2000), both from NEB, dissolved in PBS-TX-NGS].

Day 2. After washing in PBS-TX (three times, 10 min each), slices were incubated in biotinylated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Vectastain, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), diluted 1:200 in PBS-TX-NGS for 2 hr at room temperature. After the sections were washed three times (10 min each) in PBS-TX, they were incubated for 90 min in avidin–biotin–peroxidase complex (Vectastain, Vector Laboratories; final dilution 1:100). Sections were washed three times (10 min each) in PBS-TX, placed in a solution of PBS containing 0.1% 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB), and incubated for 10 min at room temperature. Reaction was developed by adding 0.02% H2O2 for 2–3 min. After extensive washings, tissue sections were mounted onto gelatin-coated slides for light microscopic examination. In some experiments slices were counterstained using standard cresyl violet (Nissl staining). Counting of neurons of the CA1 pyramidal cell layer was performed in the region between the beginning of CA2 and the subicular end of CA1 (see Fig. 1A, region between the two arrows). Counting of neurons in CA2–CA4 was performed in the remainder of the pyramidal cell layer. All counts were performed blind as to the stimulating conditions of the slices. Images of DAB-stained slices were digitized, transformed into TIFF files, and assembled into montages using Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems, Mountain View, CA).

Laser confocal microscopy immunohistochemistry

Day 1. Sections (40 μm thick) were cut as described above. Free-floating sections were rinsed for 10 min in PBS-TX and blocked with 10% normal goat serum–10% normal horse serum in PBS-TX for 40 min (blocking solution). Sections were then incubated overnight at 4°C with the following primary antibodies dissolved in blocking solution: rabbit polyclonal antibody raised against phospho(Thr202/Tyr204)-MAPK (1:750, NEB) and mouse monoclonal anti-phospho-(Thr286)-CaMKII antibody (1:1000, Upstate Biotechnology).

Day 2. After washing in PBS-TX (three times, 10 min each), slices were incubated for 2 hr at room temperature with fluorescein (FITC)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Vectastain, Vector Laboratories) diluted 1:200 in blocking solution. Sections were then washed (three times, 10 min each) and mounted onto gelatin-coated slides for microscopic examination using Vectashield (Vector Laboratories) as mounting medium. For double labeling, slices were incubated for an additional 2 hr at room temperature with FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG plus Texas Red-conjugated horse anti-mouse IgG, both diluted 1:200 in blocking solution (both from Vector Laboratories). After extensive washings, sections were mounted as above.

FITC single-labeled and FITC/Texas Red double-labeled tissue sections were analyzed and imaged using a Zeiss LSM 410 inverted confocal microscope with Zeiss Plan-Neofluar objectives (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). For visualization of FITC, an ArKr 488/568 laser was used with a 515–540 nm bandpass emission, and for visualization of Texas Red, the same laser was used with a 590 nm long-pass emission filter. Forty micrometer slices were scanned at 20 μm depth, keeping all the parameters (pinhole, contrast, and brightness) constant for slices from the same experiment. Images demonstrate colocalization of phospho-MAPK and phospho-CaMKII in neurons but represent only semiquantitative immunofluorescence intensity. Images were saved as TIFF files. To obtain the images shown in Figure6A–C, two sets of two overlapping scans of sections of area CA1 were recorded from each slice, one set of phospho-MAPK images (digitally converted to green) and a second set of phospho-CaMKII (digitally converted to red). Scans were then digitally combined to obtain double-labeled FITC/Texas Red images. The images were then assembled into montages using Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems).

Fig. 6.

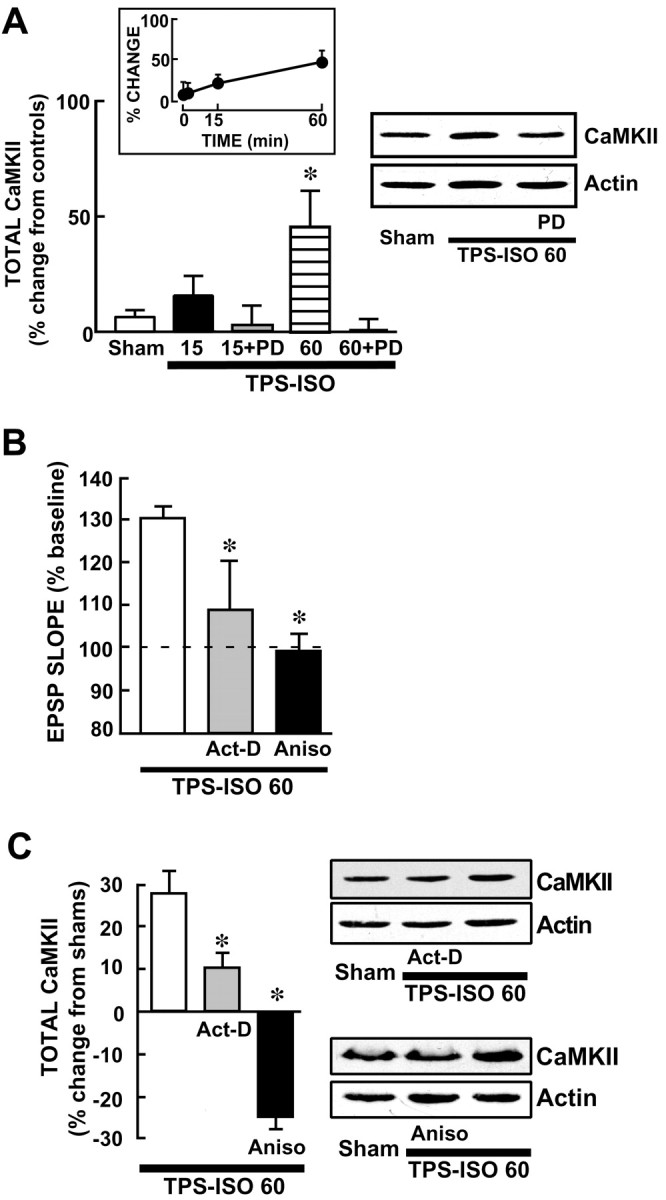

TPS–ISO produces a delayed increase in total CaMKII that requires MAPK activation and protein synthesis.A, A MEK inhibitor prevents the increase in CaMKII expression after TPS–ISO. Western immunoblots were prepared from CA1 regions, using antibody probes for total CaMKII and for actin. The bar graph shows summary data, with total CaMKII level normalized to actin from the same CA1 sample and expressed as percentage change from unstimulated controls. Total CaMKII was significantly increased only at 60 min after TPS–ISO (*p < 0.05). Atright is a representative immunoblot, which was run with CA1 homogenates from slices harvested at 60 min. PD= 50 μm PD98059. B, LTP measured at 60 min after TPS–ISO is inhibited by actinomycin-D or anisomycin. Both drugs were applied in the bath starting 30 min before TPS–ISO. The graph summarizes EPSP slopes at 60 min after stimulation, expressed as percentage of baseline. TPS–ISO-induced LTP measured 31.1 ± 6.7% above baseline (n = 5) and was blocked by 40 μm actinomycin-D (Act-D) or 20 μm anisomycin (Aniso) [+9.7 ± 11.7% (n = 3) and −1.1 ± 7.3% (n = 3), respectively; both pvalues < 0.05 vs TPS–ISO]. C, The increase in total CaMKII by TPS–ISO is blocked by actinomycin-D and anisomycin. Slices were harvested 60 min after TPS–ISO or at the equivalent time for sham-stimulated controls. The graph indicates total CaMKII levels normalized to actin for each band and expressed as percentage change from the sham-stimulated slices. TPS–ISO produced an increase in total CaMKII (+33.9 ± 16.6%; n = 5), which was prevented by 40 μm actinomycin-D and 20 μmanisomycin [+9.7 ± 6% (n = 3) and −24.2 ± 5.7% (n = 3), respectively; both pvalues < 0.05 vs TPS–ISO]. Anisomycin reduced total CaMKII below sham-stimulated controls (p < 0.05). Sample immunoblots are shown for CA1 homogenates from slices treated with actinomycin-D (top blot) and anisomycin (bottom blot).

Statistical analysis

Summary data are presented as group means ± SEM. Immunoblot and cell count data were expressed as the percentage relative to nonstimulated controls run in the same experiment. In no experiment did the sham-stimulated slices differ significantly from these controls. Group means were analyzed by Student's ttest or by ANOVAs followed by Newman–Keuls post hoctests.

RESULTS

TPS–ISO induces MAPK-dependent LTP and increases MAPK phosphorylation in area CA1

TPS–ISO induced a stable LTP that was inhibited in slices preincubated with the MEK inhibitor PD98059 (Fig.1). The effect of PD98059 became statistically significant at 30 min after stimulation, and even as early as 10 min a trend toward inhibition of potentiation was apparent. This time course of LTP inhibition by PD98059 is similar to that reported in slices stimulated with trains of high-frequency stimulation (HFS) (English and Sweatt, 1996, 1997). Additional experiments showed a similar inhibition of LTP by pretreatment with 30 μmPD98059 (LTP at 60 min: 142 ± 27% in controls, n= 3, and 117 ± 13%, n = 3 in slices treated with PD98059; p < 0.05), in contrast to previous findings with HFS-induced LTP (Liu et al., 1999).

Immunoblots for phospho-MAPK and total MAPK were performed on area CA1 excised from hippocampal slices harvested at 2, 15, and 60 min after the end of TPS–ISO stimulation. Densitometric analysis of immunoblots of area CA1 showed that TPS–ISO caused an early and transient increase in p42 MAPK phosphorylation (Fig. 1C). Phospho-p42 MAPK levels were significantly increased at 2 and 15 min after the end of stimulation [+174.2 ± 46.1% (n = 8) and +152.2 ± 31.9% (n = 13) above controls, respectively]. At 60 min, a time point when LTP was intact, phospho-p42 MAPK had declined toward control levels (+61.6 ± 12.4%; n = 4). The TPS–ISO-induced increase in phospho-p42 MAPK was well below the point of saturation, because a larger increase was seen in slices exposed to 10 μm phorbol-12,13-dibutyrate in separate experiments (+326.8 ± 71.9%; n = 9). As reported previously (Kanterewicz et al., 2000), the amount of total p44 MAPK in rat hippocampus appeared to be considerably less than p42 MAPK; in our immunoblots, total p44 MAPK generally could be detected only by overexposing the p42 MAPK signal. Under these conditions, p44 MAPK phosphorylation was not increased after TPS–ISO (data not shown), in agreement with previous results from HFS-stimulated slices (English and Sweatt, 1996, 1997). Preincubating the slices with PD98059 (50 μm) for 2 hr before stimulation completely inhibited the effect of TPS–ISO stimulation on p42 MAPK phosphorylation, at both 2 min and 15 min after stimulation [−50.3 ± 8.9% (n = 7) and −55.3 ± 1.8 (n = 3), respectively]. MAPK phosphorylation was also blocked by the NMDA antagonist APV (+3 ± 11.1%;n = 3; at 15 min after stimulation). Stimulation of slices with 1 μm isoproterenol alone, which did not produce any reliable effect on the EPSP (Fig.1B), had a nonsignificant tendency to increase p42 MAPK phosphorylation at 2 min (+85.7 ± 45.4%; n= 3) after stimulation, but not at 15 min (+32.3 ± 24.2%;n = 8).

PD98059 can also inhibit Erk5 phosphorylation by MEK5 (Kamakura et al., 1999). To evaluate whether the inhibition of this pathway might contribute to the effect of PD98059 on TPS–ISO-induced LTP, we assayed homogenates of CA1 regions and HeLa cells for the mobility shift that is characteristic of activated Erk5 (Kato et al., 1998). There was strong labeling for the enzyme in unstimulated as well as stimulated HeLa cells, but only a weak band in the CA1 region immunoblots (which needed to be overexposed to be visible in the blots) (Fig.1D). A clear mobility shift was evident in Erk5 from HeLa cells exposed to EGF, but not in Erk5 from slices stimulated with TPS–ISO. These data indicate that the Erk5 pathway is not involved in TPS–ISO-induced LTP.

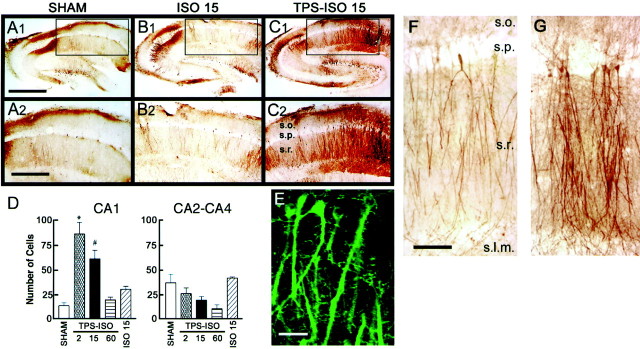

The distribution of MAPK phosphorylation after TPS–ISO

The locus of MAPK activation after TPS–ISO is of interest, because there are both cytoplasmic and nuclear targets for MAPK that could contribute to the expression of LTP. MAPK translocates to the nucleus upon phosphorylation (Impey et al., 1998) but also activates cytoplasmic substrates such as phospholipase A2(Hazan et al., 1997), ribosomal protein S6 kinase, and Elk-1 (Sgambato et al., 1998; Davis et al., 2000). Using immunohistochemical methods, we investigated the anatomical and cellular localization of phospho-MAPK in the hippocampal slice after TPS–ISO stimulation. TPS–ISO dramatically increased phospho-MAPK immunoreactivity in the pyramidal cell bodies of area CA1 (Fig.2A–C). This effect was quantified by counting the labeled cell bodies in the CA1 pyramidal cell layer of 40-μm-thick slices (between arrowsshown in Fig. 1A) and in the remainder of stratum pyramidale (areas CA2–CA4). Few pyramidal neurons were positive for phospho-MAPK immunoreactivity in the CA1 region of sham-stimulated slices or unstimulated controls [13.3 ± 3.0 cells (n = 6), and 8.5 ± 2.1 cells (n = 11), respectively]. TPS–ISO pairing dramatically increased phospho-MAPK immunoreactivity in CA1 neurons at 2 and 15 min after stimulation [86.8 ± 11.9 cells (n = 7) and 61.3 ± 8.7 cells (n = 7), respectively; bothp values < 0.05 vs shams]. The increase in MAPK phosphorylation was transient, with the number of positive cell bodies returning to control levels within 60 min (19.0 ± 3.0 cells; n = 3). The effect of isoproterenol alone on the number of phospho-MAPK-positive cells was relatively weak and brief, differing from controls only at 2 min after stimulation [30 ± 3 cells (n = 3)], whereas TPS alone did not significantly increase the number of positive cells at any time point. Outside of the CA1 region, TPS–ISO stimulation did not increase phospho-MAPK immunoreactivity in pyramidal neurons at any of the time points tested (Fig. 2D), indicating that the effect of the LTP-inducing stimulation was restricted to the postsynaptic cells of the Schaffer collateral–CA1 synapse.

Fig. 2.

The hippocampal distribution of phosphorylated MAPK after TPS–ISO. A–C, Phospho-MAPK was visualized using DAB staining. The top images show entire hippocampal slices, with the boxed region (areaCA1) digitally expanded in the bottom images. A shows a sham-treated slice,B shows a slice treated with 1 μmisoproterenol alone and harvested 15 min after treatment, andC shows a TPS–ISO slice 15 min after treatment. Note the prominent staining in stratum pyramidale (s.p.) and stratum radiatum (s.r.) of CA1, which was consistently seen in TPS–ISO-treated slices. In this slice, stratum oriens (s.o.) also showed strong staining, which was observed only in a minority of slices treated with TPS–ISO. Scale bars:top traces, 1 mm; bottom traces, 500 μm. D, Summary of the quantitative analysis performed on DAB-positive pyramidal cell bodies in areas CA1 (left panel) and CA2–CA4 (right panel). DAB-positive cell bodies were counted for CA1 (roughly corresponding to the bottom panels ofA–C) (Fig. 1A) and for the remainder of the pyramidal layer (CA2–CA4). In area CA1, only TPS–ISO-treated slices, harvested at either 2 or 15 min after stimulation, showed an increase in DAB-positive cells (*p < 0.01; #p < 0.05). No significant effects were observed in CA2–CA4.E, A laser confocal immunofluorescent image of phospho-MAPK immunoreactivity in area CA1 of a TPS–ISO-treated slice harvested 15 min after treatment. Labeling was observed throughout the dendrites of stratum radiatum, in the perinuclear region, and in the nucleus. Scale bar, 25 μm. F, G, DAB-labeled images within area CA1 of sham-stimulated (F) and TPS–ISO (G) slices, harvested 15 min after stimulation. The entire apical dendritic tree of CA1 pyramidal neurons is shown. s.o., Stratum oriens; s.p., stratum pyramidale; s.r., stratum radiatum; s.l.m., stratum lacunosum-moleculare. Scale bar, 100 μm.

TPS–ISO consistently increased MAPK phosphorylation in the dendrites of stratum radiatum, and rarely in stratum oriens. After TPS–ISO, labeling was evident in fine dendritic branches (Fig.2E) and prominent throughout the apical dendritic tree in positive neurons, extending from stratum pyramidale to stratum lacunosum-moleculare (Fig. 2F,G). The increase in phospho-MAPK immunoreactivity was transient throughout the dendrites, returning to baseline within 60 min (data not shown).

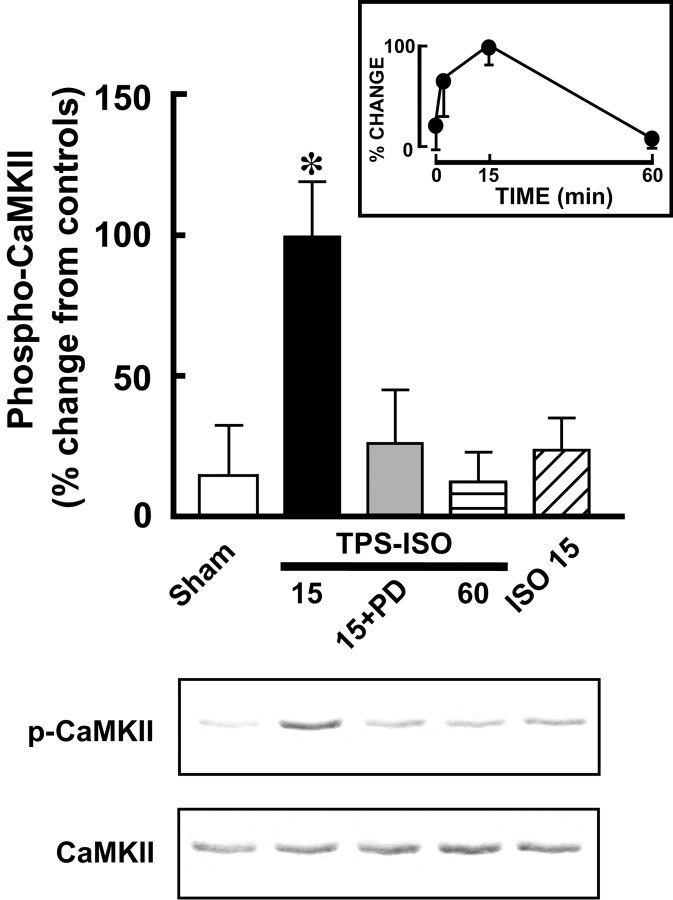

MAPK is required for CaMKII phosphorylation in area CA1 during TPS–ISO-induced LTP

Trains of HFS produce a persistent phosphorylation of CaMKII in area CA1 (Fukunaga et al., 1995; Ouyang et al., 1997). We found that TPS–ISO also increased the fraction of CaMKII in the phosphorylated form (Fig. 3). However, this effect was transient, peaking at ∼15 min after stimulation (+99.3 ± 19.6%; n = 13) and returning to control levels within 60 min (+6.6 ± 9.1%; n = 10), when LTP was still intact. Preincubating the slices before stimulation with PD98059, a MEK inhibitor without direct effects on CaMKII activity (English and Sweatt, 1997; Liu et al., 1999), completely blocked the increase in CaMKII phosphorylation by TPS–ISO [at 15 min, +25.0 ± 19.5% (n = 4), not statistically different from sham-stimulated controls, which measured +14.2 ± 17.8% (n = 11)]. The effect of TPS–ISO at 15 min was also blocked by incubating the slices with the NMDA antagonist APV (100 μm for 10 min, +26.5 ± 16.5%;n = 3). Stimulation with 1 μmisoproterenol alone did not significantly increase CaMKII phosphorylation at any time point.

Fig. 3.

The MAPK pathway is required for TPS–ISO-induced phosphorylation of CaMKII in area CA1. The bar graph summarizes immunoblot data and shows phospho-CaMKII levels normalized to total CaMKII and expressed as percentage of paired, untreated control slices. Only TPS–ISO slices harvested 15 min after stimulation showed a significant increase in CaMKII phosphorylation (*p< 0.05). This effect was completely blocked by treatment with 50 μm PD98059. The inset shows the time course of phospho-CaMKII after TPS–ISO stimulation. The representative Western immunoblot, which was taken from a single experiment, includes the treatments summarized in the graph. The top panelshows phosphorylated CaMKII, and the bottom panel shows total CaMKII.

Phospho-CaMKII is dephosphorylated by protein phosphatase-1 (PP1) (Strack et al., 1997), and the physiological inhibition of PP1 can be an important factor in the induction of LTP (Blitzer et al., 1995;Coussens and Teyler, 1996; Thomas et al., 1996; Blitzer et al., 1998). In the case of TPS–ISO, β-adrenergic stimulation by isoproterenol reduces PP1 activity by activating phosphatase inhibitor-1 (I-1) to enable the induction of LTP (Brown et al., 2000). This effect is mediated by activation of the cAMP pathway, resulting in the phosphorylation of I-1 by PKA. The role of MAPK in TPS–ISO-induced LTP could involve the inhibition of PP1 activity, as suggested by a network analysis of signaling pathways (Bhalla and Iyengar, 1999). We examined this hypothesis using an LTP induction method consisting of TPS coupled with the specific inhibition of postsynaptic PP1 by thiophosphorylated I-1 (Brown et al., 2000) and testing the ability of PD98059 to block LTP induced by TPS in these cells. If MAPK were to act by facilitating the cAMP-dependent inhibition of PP1, then LTP induced in this manner should be insensitive to PD98059. Our results did not support this hypothesis. PD98059 remained completely effective in blocking LTP, indicating that the MAPK pathway must contribute to LTP by acting independently of PP1 (Fig.4A).

Fig. 4.

The MAPK requirement for LTP does not involve PP1 inhibition or spike modulation. A, PD98059 blocks LTP induced by TPS in CA1 neurons injected with 10 μmthiophosphorylated inhibitor-1 (I-1-P). In control slices (n = 5) pretreated with 0.1% DMSO, a stable LTP was obtained after TPS (150 pulses at 10 Hz), but LTP was absent in slices pretreated with 50 μm PD98059 (n = 5). The traces show superimposed sample intracellular EPSPs obtained during the baseline period and 40 min after TPS (arrowhead). Calibration: 5 mV, 10 msec. B, PD98059 does not affect the pattern of spiking during TPS in cells recorded with thiophosphorylated I-1. The intracellular potential was sampled every 30th pulse during TPS. Sample trace series and the summary data are shown. The groups did not differ significantly at any sample time. Data are from the same cells as in A. Calibration: 20 mV, 10 msec.

Burst firing is evoked during TPS in the cells injected with thiophosphorylated I-1, occurring primarily in the second half of the train and typically consisting of two or three spikes per stimulus (Fig. 4B) (Brown et al., 2000). Work in mouse hippocampal slices has shown that TPS must evoke burst spiking for the induction of LTP and that the inhibition of MAPK reduces bursting (Thomas et al., 1998; Winder et al., 1999). However, we found that PD98059 did not alter the pattern of spiking during TPS, indicating that MAPK did not contribute to LTP by shaping the synaptic response during induction (Fig. 4B). Thus, the role of MAPK in LTP appears not to be limited to the regulation of spike generation.

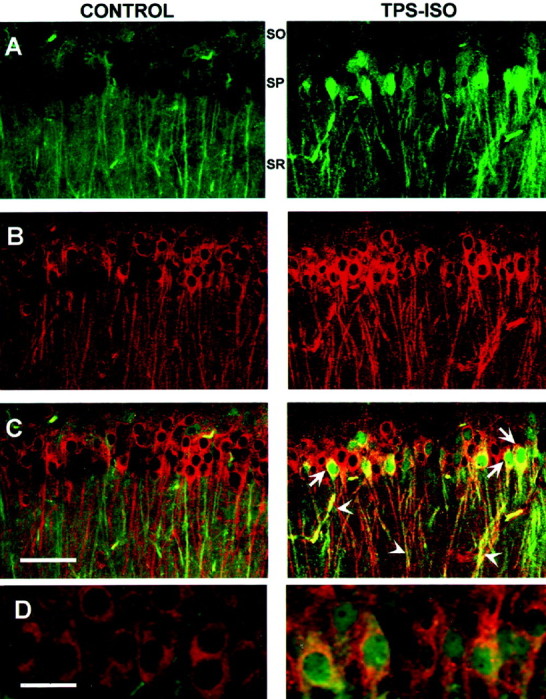

Colocalization of MAPK phosphorylation and CaMKII phosphorylation after TPS–ISO

If activation of the MAPK pathway is required for CaMKII phosphorylation after TPS–ISO, one would expect to find a colocalized increase in phospho-MAPK and phospho-CaMKII in stimulated neurons. Phospho-MAPK and phospho-CaMKII were visualized in area CA1 using double-label laser confocal microscopy. In slices harvested 15 min after TPS–ISO, phospho-MAPK labeling was increased above sham-stimulated controls in the dendrites of stratum radiatum, in the cell bodies of stratum pyramidale, and in the nuclei (Fig.5). Phospho-CaMKII immunoreactivity also increased both in the cell bodies and in the dendrites of CA1 pyramidal neurons but was excluded from the nuclei. In addition, phospho-MAPK and phospho-CaMKII colocalized in the apical dendrites and the perinuclear somata of CA1 pyramidal neurons in TPS–ISO-stimulated slices. In those neurons in which phospho-MAPK and phospho-CaMKII were colocalized, only phospho-MAPK translocated into the nucleus, an effect that was observed as early as 2 min after stimulation (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5.

Phospho-MAPK and phospho-CaMKII are colocalized in CA1 pyramidal neurons after TPS–ISO. Laser confocal images were obtained from slices that were double labeled using antibodies specific for phospho-MAPK and phospho-CaMKII. Phospho-MAPK labeling is indicated by green (A), phospho-CaMKII labeling is indicated by red (B), and combined labeling is indicated by yellow-orange(C, D). The panels on theleft are from sham-stimulated controls, and those on theright are from slices harvested 15 min (A–C) or 2 min (D) after TPS–ISO. A–C, At 15 min after stimulation, TPS–ISO increased both phospho-MAPK and phospho-CaMKII in dendrites of stratum radiatum (s.r.) and in cell bodies of stratum pyramidale (s.p.). The digitally combined signals (C) show that phospho-MAPK and phospho-CaMKII were colocalized in dendrites and in the perinuclear region, but only phospho-MAPK translocated to the nucleus. Scale bar, 50 μm. D, As early as 2 min after TPS–ISO, phospho-MAPK had already translocated to the nucleus. Scale bar, 20 μm.

TPS–ISO produces a MAPK-dependent increase in total CaMKII

High-frequency stimulation has been associated with an increase in total CaMKII in the dendrites and cell bodies of CA1 neurons (Ouyang et al., 1997, 1999). We observed that TPS–ISO significantly increased total CaMKII in area CA1 above sham-stimulated controls 60 min after stimulation (+46.6 ± 15.6%; n = 10) (Fig.6A), with a tendency toward elevated CaMKII at the 15 min time point (+19.7 ± 8.5%;n = 10). Because MAPK can regulate protein expression through both transcriptional and translational mechanisms (Seger and Krebs, 1995; Pain, 1996), we tested the ability of PD98059 to prevent the increase in CaMKII expression induced by TPS–ISO. In slices that had been preincubated with PD98059, TPS–ISO did not increase the level of total CaMKII at 15 min (+2.8 ± 8.6%; n = 6) or 60 min (+0.5 ± 5.1%; n = 5) after stimulation. These results suggest that the transient rise in MAPK activity that follows TPS–ISO stimulation contributes to the later increase in CaMKII expression, perhaps reflecting the MAPK-regulated transcription or translation of CaMKII.

The increase in total CaMKII is translation and transcription dependent

To determine whether the increase in total CaMKII was mediated by protein synthesis, we tested the effects of inhibitors of transcription and translation. As shown in Figure 6C, both actinomycin-D and anisomycin blocked LTP measured 60 min after TPS–ISO, as shown previously (Frey et al., 1993; Huang and Kandel, 1994). The increase in total CaMKII at 60 min was significantly reduced by actinomycin-D, and anisomycin reduced the level of CaMKII below that of control slices. These results indicate that the rise in CaMKII levels reflects de novo protein synthesis, rather than decreased CaMKII degradation.

DISCUSSION

Ca2+- and cAMP-dependent pathways may contribute to p42 MAPK phosphorylation by TPS–ISO

Several signaling mechanisms converge to activate the MAPK pathway in CNS neurons, and this integrative property may be important for the effectiveness of TPS–ISO stimulation in phosphorylating MAPK. Specifically, TPS–ISO is expected to mobilize two different pathways that lead to MAPK phosphorylation, one initiated by Ca2+ and the other by cAMP (Grewal et al., 1999). Even individual EPSPs produce NMDA receptor-dependent Ca2+ transients in dendritic spines of CA1 neurons (Emptage et al., 1999), and patterns of stimulation used to induce LTP result in a more extensive elevation of Ca2+ (Perkel et al., 1993; Yeckel et al., 1999). The Ca2+ influx resulting from strong HFS of the Schaffer collaterals is sufficient by itself to activate MAPK (English and Sweatt, 1996; Impey et al., 1998). We found that the MAPK phosphorylation induced by TPS–ISO was blocked by the NMDA receptor antagonist APV, so the Ca2+pathway is required for MAPK activation with this form of stimulation as well. However, the Ca2+ signal itself was insufficient to activate the MAPK pathway, because TPS without ISO did not increase phospho-MAPK.

Similarly, isoproterenol alone only modestly increased MAPK phosphorylation in our experiments. In mouse hippocampus, β-adrenergic stimulation increases MAPK phosphorylation, an effect that desensitizes after 10 min of isoproterenol exposure (Winder et al., 1999). It is likely that such desensitization occurred in our experiments during the 10 min application of isoproterenol, resulting in little MAPK phosphorylation measured even at our earliest post-stimulation time point in slices exposed only to isoproterenol. Despite the activation of MAPK by isoproterenol, Winder at al. (1999)found that this treatment did not produce any lasting increase in the EPSP, indicating that MAPK plays a regulatory role in LTP. However, the duration of MAPK activation can be an important determinant of the cellular consequences of this pathway (Marshall, 1995). By recruiting both the Ca2+ and cAMP routes of MAPK pathway activation, and substantially prolonging the duration of MAPK phosphorylation, TPS–ISO pairing may engage downstream mechanisms that differ from those of β-adrenergic stimulation alone. A similar synergistic effect has been reported in PC12 cells, in which the activation of a receptor tyrosine kinase or the generation of cAMP separately stimulates MAPK only transiently, but together they produce a sustained increase in activity (Yao et al., 1995). In this context, it is interesting that the LTP protocols shown to phosphorylate MAPK or to increase MAPK-mediated gene expression are also likely to generate postsynaptic cAMP, either by Ca2+-dependent activation of adenylyl cyclases or by the stimulation of cyclase-coupled receptors (Blitzer et al., 1995; English and Sweatt, 1996; Impey et al., 1998). Concurrent increases in Ca2+ and cAMP thus may be particularly effective in generating a prolonged phospho-MAPK signal, in addition to the previously demonstrated cooperative role of these pathways in the MAPK-dependent activation of CREB (Impey et al., 1998).

The role of CaMKII activation in neuronal plasticity

The importance of CaMKII in regulating synaptic plasticity and dendritic architecture has been established in various preparations. Such diverse phenomena as dendritic exocytosis and stabilization, induction of LTP, growth cone turning, and the regulation of synaptic density require active CaMKII (Zheng et al., 1994; Giese et al., 1998;Maletic-Savatic et al., 1998; Wu and Cline, 1998; Rongo and Kaplan, 1999). The role of CaMKII in the neuron has focused primarily on its catalytic activity, which can behave as a biochemical switch by becoming autonomous after a transient rise in Ca2+ (Hanson et al., 1994). The induction of LTP has been identified as a process that requires CaMKII activation (Otmakhov et al., 1997; Giese et al., 1998), possibly through the phosphorylation or synaptic insertion of AMPA receptors (Hayashi et al., 2000; Lee et al., 2000).

CaMKII is a prominent constituent of the postsynaptic density (PSD), a highly interactive complex of proteins that includes many components of the synaptic signaling network (Husi et al., 2000;Walikonis et al., 2000). CaMKII binds to several scaffolding or cytoskeletal proteins and to NMDA receptors. Some of these associations, as well as the translocation of CaMKII to postsynaptic sites, require that CaMKII be activated (Strack and Colbran, 1998;Gardoni et al., 1999; Shen et al., 2000). In addition, CaMKII phosphorylates substrates in the PSD that are clearly central to some forms of synaptic function, including AMPA- and NMDA-type glutamate receptors (McGlade-McCulloh et al., 1993; Omkumar et al., 1996; Gardoni et al., 2001). Other CaMKII substrates are likely to contribute to neuronal plasticity; for example, the catalytic domain of CaMKII promotes the synaptic insertion of AMPA receptors independently of its ability to phosphorylate these receptors (Hayashi et al., 2000).

The biochemical mechanism by which the MAPK pathway contributes to CaMKII phosphorylation is not yet understood. We tested the possibility that MAPK inhibits postsynaptic PP1, which can act as a gate to regulate the phosphorylation of CaMKII after LTP-inducing stimulation (Blitzer et al., 1998; Bhalla and Iyengar, 1999; Brown et al., 2000). However, direct inhibition of postsynaptic PP1 did not overcome the requirement for MAPK activity, indicating that MAPK acts independently of PP1 to regulate CaMKII phosphorylation. CaMKII itself is not a substrate for MAPK, but the presence of both enzymes in the PSD suggests that interactions may occur.

MAPK-dependent expression of CaMKII and LTP maintenance

In addition to CaMKII phosphorylation, LTP-inducing stimulation also causes an increase in the total amount of CaMKII in pyramidal cell somata and dendrites. This effect was observed as soon as 5 min after high-frequency stimulation and persisted for at least 30 min (Ouyang et al., 1999). Our data show that CaMKII expression continues to rise for 60 min after stimulation with TPS–ISO. An important question is whether increased CaMKII synthesis contributes to LTP maintenance, presumably through a noncatalytic effect of CaMKII. General inhibitors of gene transcription and translation block the late phase of LTP (Nguyen et al., 1994; Frey and Morris, 1997, 1998), and the long time course of elevated CaMKII expression is consistent with the hypothesis that de novo CaMKII synthesis contributes to late LTP. CaMKII mRNA is localized to dendritic spines (Roberts et al., 1998), can be transported to the dendrites from the soma (Miyashiro et al., 1994; Mayford et al., 1996), and increases in the dendrites after the induction of LTP (Thomas et al., 1994). These findings, along with the observation that polyribosomes and other components of the translational machinery are present in dendrites, suggest that the local regulation of translation may be important in CaMKII-dependent synaptic plasticity (Tiedge and Brosius, 1996; Roberts et al., 1998; Wu et al., 1998). MAPK could influence the translation of CaMKII by regulating ribosomal initiation factors (Pain, 1996; Waskiewicz et al., 1997; Frödin and Gammeltoft, 1999). Although these initiation factors have been established as important control points for the regulation of translation by MAPK, their participation in CaMKII synthesis remains to be determined.

Extra-dendritic mechanisms may also contribute to LTP, because LTP maintenance is blocked by transcription inhibitors and appears to require the delivery of a molecule from beyond the immediate dendritic region (Nguyen et al., 1994; Frey and Morris, 1997). MAPK is known to phosphorylate transcription factors, including CREB and Elk-1 (Impey et al., 1998; Davis et al., 2000), and LTP-inducing stimulation has been shown to increase the abundance of CaMKII mRNA (Mackler et al., 1992;Thomas et al., 1994; Roberts et al., 1996). Thus, MAPK-mediated transcription may contribute to the increase in CaMKII expression after TPS–ISO stimulation. Because MAPK translocation to the nucleus and MAPK-dependent phosphorylation of CREB require activation of the cAMP pathway (Impey et al., 1998; Roberson et al., 1999), LTP-inducing stimuli that generate cAMP, such as TPS–ISO and widely spaced trains of HFS (Frey et al., 1993; Blitzer et al., 1995), are likely to be particularly effective in regulating transcription through MAPK.

Newly synthesized CaMKII, even in the absence of activation, may contribute to synaptic function. It is estimated that CaMKII comprises 20–40% of the protein in PSDs isolated from rat forebrain (Hanson and Schulman, 1992). A sizeable fraction of this CaMKII appears to be catalytically inactive, suggesting the possibility of a structural function. CaMKII within isolated PSDs has low activity that is responsive to Ca2+/calmodulin (Rich et al., 1989), and the PSD protein densin-180 shows affinity for inactive CaMKII (Strack et al., 2000; Walikonis et al., 2001). The increase in CaMKII expression after LTP-inducing stimulation may result in a structural modification of the synapse that contributes to the stabilization of LTP.

By virtue of its ability to regulate translation and transcription and to modify components of the postsynaptic signaling network, MAPK is likely to participate in diverse forms of neuronal plasticity. The present study establishes a novel paradigm for such a role of MAPK: an early covalent modification of a signaling protein, followed by increased expression of the same protein. As the interactions between the components of the dendritic compartment become better understood, other examples of MAPK regulating signaling pathways at multiple levels may be identified.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant NS33646 and a Veterans Affairs Merit Grant to E.M.L., NIH Grant GM5408 to R.I., and NIH Grant AG06647 to J.H.M. M.G.G. is the recipient of Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche-NATO fellowship N. 217.30. We thank William Janssen, Michelle Adams, and Ravi Shah for their help in confocal laser microscopy, J. Dedrick Jordan and Prahlad Ram for advice on immunochemistry, and Tara A. Santore for performing the HeLa experiments. Thiophosphorylated inhibitor-1 was a gift of Shirish Shenolikar.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Robert D. Blitzer, Box 1215, Department of Pharmacology, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, One Gustave Levy Place, New York, NY 10029. E-mail:rb2@doc.mssm.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Atkins CM, Selcher JC, Petraitis JJ, Trzaskos JM, Sweatt JD. The MAPK cascade is required for mammalian associative learning. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:602–609. doi: 10.1038/2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhalla US, Iyengar R. Emergent properties of networks of biological signaling pathways. Science. 1999;283:381–387. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5400.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bliss TV, Collingridge GL. A synaptic model of memory: long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. Nature. 1993;361:31–39. doi: 10.1038/361031a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blitzer RD, Wong T, Nouranifar R, Iyengar R, Landau EM. Postsynaptic cAMP pathway gates early LTP in hippocampal CA1 region. Neuron. 1995;15:1403–1414. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blitzer RD, Connor JH, Brown GP, Wong T, Shenolikar S, Iyengar R, Landau EM. Gating of CaMKII by cAMP-regulated protein phosphatase activity during LTP. Science. 1998;280:1940–1942. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5371.1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown GP, Blitzer RD, Connor JH, Wong T, Shenolikar SH, Iyengar R, Landau EM. Long-term potentiation induced by theta frequency stimulation is regulated by a protein phosphatase 1-operated gate. J Neurosci. 2000;20:7880–7887. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-21-07880.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang L, Karin M. Mammalian MAP kinase signaling cascades. Nature. 2001;410:37–40. doi: 10.1038/35065000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen HJ, Rojas-Soto M, Oguni A, Kennedy MB. A synaptic Ras-GTPase activating protein (p135 SynGAP) inhibited by CaM kinase II. Neuron. 1998;20:895–904. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80471-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coussens CM, Teyler TJ. Protein kinase and phosphatase activity regulate the form of synaptic plasticity expressed. Synapse. 1996;24:97–103. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199610)24:2<97::AID-SYN1>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis S, Vanhoutte P, Pages C, Caboche J, Laroche S. The MAPK/ERK cascade targets both Elk-1 and cAMP response element-binding protein to control long-term potentiation-dependent gene expression in the dentate gyrus in vivo. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4563–4572. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-12-04563.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Emptage N, Bliss TV, Fine A. Single synaptic events evoke NMDA receptor-mediated release of calcium from internal stores in hippocampal dendritic spines. Neuron. 1999;22:115–124. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80683-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.English JD, Sweatt JD. Activation of p42 mitogen-activated protein kinase in hippocampal long term potentiation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:24329–24332. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.40.24329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.English JD, Sweatt JD. A requirement for the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade in hippocampal long term potentiation. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:19103–19106. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.31.19103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flood DG, Finn JP, Walton KM, Dionne CA, Contreras PC, Miller MS, Bhat RV. Immunolocalization of the mitogen-activated protein kinases p42MAPK and JNK1, and their regulatory kinases MEK1 and MEK4, in adult rat central nervous system. J Comp Neurol. 1998;398:373–392. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19980831)398:3<373::aid-cne6>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frey U, Morris RG. Synaptic tagging and long-term potentiation. Nature. 1997;385:533–536. doi: 10.1038/385533a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frey U, Morris RG. Synaptic tagging: implications for late maintenance of hippocampal long-term potentiation. Trends Neurosci. 1998;21:181–188. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(97)01189-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frey U, Huang YY, Kandel ER. Effects of cAMP simulate a late stage of LTP in hippocampal CA1 neurons. Science. 1993;260:1661–1664. doi: 10.1126/science.8389057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frödin M, Gammeltoft S. Role and regulation of 90 kDa ribosomal S6 kinase (RSK) in signal transduction. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1999;151:65–77. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(99)00061-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fukunaga K, Muller D, Miyamoto E. Increased phosphorylation of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II and its endogenous substrates in the induction of long-term potentiation. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:6119–6124. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.11.6119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gardoni F, Schrama LH, van Dalen JJ, Gispen WH, Cattabeni F, Di Luca M. αCaMKII binding to the C-terminal tail of NMDA receptor subunit NR2A and its modulation by autophosphorylation. FEBS Lett. 1999;456:394–398. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00985-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gardoni F, Schrama LH, Kamal A, Gispen WH, Cattabeni F, Di Luca M. Hippocampal synaptic plasticity involves competition between Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II and postsynaptic density 95 for binding to the NR2A subunit of the NMDA receptor. J Neurosci. 2001;21:1501–1509. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-05-01501.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giese KP, Fedorov NB, Filipkowski RK, Silva AJ. Autophosphorylation at Thr286 of the α calcium-calmodulin kinase II in LTP and learning. Science. 1998;279:870–873. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5352.870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grewal SS, York RD, Stork PJ. Extracellular-signal-regulated kinase signaling in neurons. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1999;9:544–553. doi: 10.1016/S0959-4388(99)00010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hanson PI, Schulman H. Neuronal Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinases. Annu Rev Biochem. 1992;61:559–601. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.61.070192.003015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hanson PI, Meyer T, Stryer L, Schulman H. Dual role of calmodulin in autophosphorylation of multifunctional CaM kinase may underlie decoding of calcium signals. Neuron. 1994;12:943–956. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90306-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hayashi Y, Shi SH, Esteban JA, Piccini A, Poncer JC, Malinow R. Driving AMPA receptors into synapses by LTP and CaMKII: requirement for GluR1 and PDZ domain interaction. Science. 2000;287:2262–2267. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5461.2262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hazan I, Dana R, Granot Y, Levy R. Cytosolic phospholipase A2 and its mode of activation in human neutrophils by opsonized zymosan. Correlation between 42/44 kDa mitogen-activated protein kinase, cytosolic phospholipase A2 and NADPH oxidase. Biochem J. 1997;326:867–876. doi: 10.1042/bj3260867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang YY, Kandel ER. Recruitment of long-lasting and protein kinase A-dependent long-term potentiation in the CA1 region of hippocampus requires repeated tetanization. Learn Mem. 1994;1:74–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Husi H, Ward MA, Choudhary JS, Blackstock WP, Grant SG. Proteomic analysis of NMDA receptor-adhesion protein signaling complexes. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:661–669. doi: 10.1038/76615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Impey S, Obrietan K, Wong ST, Poser S, Yano S, Wayman G, Deloulme JC, Chan G, Storm DR. Cross talk between ERK and PKA is required for Ca2+ stimulation of CREB-dependent transcription and ERK nuclear translocation. Neuron. 1998;21:869–883. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80602-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kamakura S, Moriguchi T, Nishida E. Activation of the protein kinase ERK5/BMK1 by receptor tyrosine kinases. Identification and characterization of a signaling pathway to the nucleus. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:26563–26571. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.37.26563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kanterewicz BI, Urban NN, McMahon DB, Norman ED, Giffen LJ, Favata MF, Scherle PA, Trzskos JM, Barrionuevo G, Klann E. The extracellular signal-regulated kinase cascade is required for NMDA receptor-independent LTP in area CA1 but not area CA3 of the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2000;20:3057–3066. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-09-03057.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kato Y, Tapping RI, Huang S, Watson MH, Ulevitch RJ, Lee JD. Bmk1/Erk5 is required for cell proliferation induced by epidermal growth factor. Nature. 1998;395:713–716. doi: 10.1038/27234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim JH, Liao D, Lau LF, Huganir RL. SynGAP: a synaptic RasGAP that associates with the PSD-95/SAP90 protein family. Neuron. 1998;20:683–691. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee HK, Barbarosie M, Kameyama K, Bear MF, Huganir RL. Regulation of distinct AMPA receptor phosphorylation sites during bidirectional synaptic plasticity. Nature. 2000;405:955–959. doi: 10.1038/35016089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu J, Fukunaga K, Yamamoto H, Nishi K, Miyamoto E. Differential roles of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II and mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in hippocampal long-term potentiation. J Neurosci. 1999;19:8292–8299. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-19-08292.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mackler SA, Brooks BP, Eberwine JH. Stimulus-induced coordinate changes in mRNA abundance in single postsynaptic hippocampal CA1 neurons. Neuron. 1992;9:539–548. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90191-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Malenka RC, Nicoll RA. Long-term potentiation—a decade of progress? Science. 1999;285:1870–1874. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5435.1870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maletic-Savatic M, Koothan T, Malinow R. Calcium-evoked dendritic exocytosis in cultured hippocampal neurons. Part II: mediation by calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. J Neurosci. 1998;18:6814–6821. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-17-06814.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marshall CJ. Specificity of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling: transient versus sustained extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation. Cell. 1995;80:179–185. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90401-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mayford M, Baranes D, Podsypanina K, Kandel ER. The 3′-untranslated region of CaMKII alpha is a cis-acting signal for the localization and translation of mRNA in dendrites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13250–13255. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McGlade-McCulloh E, Yamamoto H, Tan SE, Brickey DA, Soderling TR. Phosphorylation and regulation of glutamate receptors by calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Nature. 1993;362:640–642. doi: 10.1038/362640a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miyashiro K, Dichter M, Eberwine J. On the nature and differential distribution of mRNAs in hippocampal neurites: implications for neuronal functioning. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10800–10804. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.10800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Muthalif MM, Benter IF, Uddin MR, Malik KU. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IIα mediates activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase and cytosolic phospholipase A2 in norepinephrine-induced arachidonic acid release in rabbit aortic smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:30149–30157. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.47.30149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nguyen PV, Abel T, Kandel ER. Requirement of a critical period of transcription for induction of a late phase of LTP. Science. 1994;265:1104–1107. doi: 10.1126/science.8066450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Omkumar RV, Kiely MJ, Rosenstein AJ, Min KT, Kennedy MB. Identification of a phosphorylation site for calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in the NR2B subunit of the N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:31670–31678. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.49.31670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Otmakhov N, Griffith LC, Lisman JE. Postsynaptic inhibitors of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase type II block induction but not maintenance of pairing-induced long-term potentiation. J Neurosci. 1997;17:5357–5365. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-14-05357.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ouyang Y, Kantor D, Harris KM, Schuman EM, Kennedy MB. Visualization of the distribution of autophosphorylated calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II after tetanic stimulation in the CA1 area of the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1997;17:5416–5427. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-14-05416.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ouyang Y, Rosenstein A, Kreiman G, Schuman EM, Kennedy MB. Tetanic stimulation leads to increased accumulation of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II via dendritic protein synthesis in hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 1999;19:7823–7833. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-18-07823.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pain VM. Initiation of protein synthesis in eukaryotic cells. Eur J Biochem. 1996;236:747–771. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.00747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Perkel DJ, Petrozzino JJ, Nicoll RA, Connor JA. The role of Ca2+ entry via synaptically activated NMDA receptors in the induction of long-term potentiation. Neuron. 1993;11:817–823. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90111-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rich DP, Colbran RJ, Schworer CM, Soderling TR. Regulatory properties of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in rat brain postsynaptic densities. J Neurochem. 1989;53:807–816. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1989.tb11777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Roberson ED, English JD, Adams JP, Selcher JC, Kondratick C, Sweatt JD. The mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade couples PKA and PKC to cAMP response element binding protein phosphorylation in area CA1 of hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1999;19:4337–4348. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-11-04337.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roberts LA, Higgins MJ, O'Shaughnessy CT, Stone TW, Morris BJ. Changes in hippocampal gene expression associated with the induction of long-term potentiation. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1996;42:123–127. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(96)00148-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roberts LA, Large CH, Higgins MJ, Stone TW, O'Shaughnessy CT, Morris BJ. Increased expression of dendritic mRNA following the induction of long-term potentiation. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1998;56:38–44. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(98)00026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rongo C, Kaplan JM. CaMKII regulates the density of central glutamatergic synapses in vivo. Nature. 1999;402:195–199. doi: 10.1038/46065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Seger R, Krebs EG. The MAPK signaling cascade. FASEB J. 1995;9:726–735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sgambato V, Vanhoutte P, Pages C, Rogard M, Hipskind R, Besson MJ, Caboche J. In vivo expression and regulation of Elk-1, a target of the extracellular-regulated kinase signaling pathway, in the adult rat brain. J Neurosci. 1998;18:214–226. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-01-00214.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shen K, Teruel MN, Connor JH, Shenolikar S, Meyer T. Molecular memory by reversible translocation of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:881–886. doi: 10.1038/78783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Strack S, Colbran RJ. Autophosphorylation-dependent targeting of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II by the NR2B subunit of the N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:20689–20692. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.33.20689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Strack S, Barban MA, Wadzinski BE, Colbran RJ. Differential inactivation of postsynaptic density-associated and soluble Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II by protein phosphatases 1 and 2A. J Neurochem. 1997;68:2119–2128. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68052119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Strack S, Robison AJ, Bass MA, Colbran RJ. Association of calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II with developmentally regulated splice variants of the postsynaptic density protein densin-180. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:25061–25064. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000319200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Thomas KL, Laroche S, Errington ML, Bliss TV, Hunt SP. Spatial and temporal changes in signal transduction pathways during LTP. Neuron. 1994;13:737–745. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90040-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Thomas MJ, Moody TD, Makhinson M, O'Dell TJ. Activity-dependent β-adrenergic modulation of low frequency stimulation induced LTP in the hippocampal CA1 region. Neuron. 1996;17:475–482. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80179-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Thomas MJ, Watabe AM, Moody TD, Makhinson M, O'Dell TJ. Postsynaptic complex spike bursting enables the induction of LTP by theta frequency synaptic stimulation. J Neurosci. 1998;18:7118–7126. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-18-07118.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tiedge H, Brosius J. Translational machinery in dendrites of hippocampal neurons in culture. J Neurosci. 1996;16:7171–7181. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-22-07171.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Walikonis R, Oguni A, Khorosheva E, Jeng C, Asuncion F, Kennedy M. Densin-180 forms a ternary complex with the α-subunit of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II and α-actinin. J Neurosci. 2001;21:423–433. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-02-00423.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Walikonis RS, Jensen ON, Mann M, Provance DW, Jr, Mercer JA, Kennedy MB. Identification of proteins in the postsynaptic density fraction by mass spectrometry. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4069–4080. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-04069.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Waskiewicz AJ, Flynn A, Proud CG, Cooper JA. Mitogen-activated protein kinases activate the serine/threonine kinases Mnk1 and Mnk2. EMBO J. 1997;16:1909–1920. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.8.1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Winder DG, Martin KC, Muzzio IA, Rohrer D, Chruscinski A, Kobilka B, Kandel ER. ERK plays a regulatory role in induction of LTP by theta frequency stimulation and its modulation by β-adrenergic receptors. Neuron. 1999;24:715–726. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81124-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wu GY, Cline HT. Stabilization of dendritic arbor structure in vivo by CaMKII. Science. 1998;279:222–226. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5348.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wu L, Wells D, Tay J, Mendis D, Abbott MA, Barnitt A, Quinlan E, Heynen A, Fallon JR, Richter JD. CPEB-mediated cytoplasmic polyadenylation and the regulation of experience-dependent translation of α-CaMKII mRNA at synapses. Neuron. 1998;21:1129–1139. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80630-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Xia Z, Dudek H, Miranti CK, Greenberg ME. Calcium influx via the NMDA receptor induces immediate early gene transcription by a MAP kinase/ERK-dependent mechanism. J Neurosci. 1996;16:5425–5436. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-17-05425.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yao H, Labudda K, Rim C, Capodieci P, Loda M, Stork PJ. Cyclic adenosine monophosphate can convert epidermal growth factor into a differentiating factor in neuronal cells. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:20748–20753. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.35.20748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yeckel MF, Kapur A, Johnston D. Multiple forms of LTP in hippocampal CA3 neurons use a common postsynaptic mechanism. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:625–633. doi: 10.1038/10180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zheng JQ, Felder M, Connor JA, Poo MM. Turning of nerve growth cones induced by neurotransmitters. Nature. 1994;368:140–144. doi: 10.1038/368140a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]