Abstract

Hypocretins (Hcrts) are recently discovered peptides linked to the human sleep disorder narcolepsy. Humans with narcolepsy have decreased numbers of Hcrt neurons and Hcrt-null mice also have narcoleptic symptoms. Hcrt neurons are located only in the lateral hypothalamus (LH) but neither electrolytic nor pharmacological lesions of this or any other brain region have produced narcoleptic-like sleep, suggesting that specific neurons need to be destroyed. Hcrt neurons express the Hcrt receptor, and to facilitate lesioning these neurons, the endogenous ligand hypocretin-2/orexin B (Hcrt2) was conjugated to the ribosome-inactivating protein saporin (SAP). In vitrobinding studies indicated specificity of the Hcrt2-SAP because it preferentially bound to Chinese hamster ovary cells containing the Hcrt/orexin receptor 2 (HcrtR2/OX2R) or the Hcrt/orexin receptor 1 (HcrtR1/OX1R) but not to Kirsten murine sarcoma virus transformed rat kidney epithelial (KNRK) cells stably transfected with the substance P (neurokinin-1) receptor. Administration of the toxin to the LH, in which the receptor is known to be present, eliminated some neurons (Hcrt, melanin-concentrating hormone, and adenosine deaminase-containing neurons) but not others (a-melanocyte-stimulating hormone), indicating specificity of the toxin in vivo. When the toxin was administered to the LH, rats had increased slow-wave sleep, rapid-eye movement (REM) sleep, and sleep-onset REM sleep periods. These behavioral changes were negatively correlated with the loss of Hcrt-containing neurons but not with the loss of adenosine deaminase-immunoreactive neurons. These findings indicate that damage to the LH that also causes a substantial loss of Hcrt neurons is likely to produce the multiple sleep disturbances that occur in narcolepsy.

Keywords: hypothalamus, peptides, lesion, sleep, REM sleep, circadian rhythm

Regular periods of sleep and wakefulness occur in virtually all mammals and birds. Sleep is generally divided into two states, slow-wave sleep (SWS) and rapid-eye movement (REM) sleep. The neuronal mechanisms underlying the regulation of sleep and wakefulness are unclear (for review, see Shiromani, 1998), and to gain a better understanding investigators have studied the human sleep disorder narcolepsy. Narcolepsy is a disabling neurological disorder characterized by excessive daytime sleepiness, sleep attacks, sleep fragmentation, cataplexy, sleep-onset REM sleep periods (SOREMP), and hypnagogic hallucinations. Recently, narcolepsy was linked with the loss of neurons containing the hypocretin (Hcrt) neuropeptides (Peyron et al., 2000; Thannickal et al., 2000). Narcoleptic patients have low CSF concentrations of hypocretin-1 (Nishino et al., 2000), which is consistent with a decrease in the number of Hcrt neurons. Moreover, narcoleptic canines possess a mutation in the hypocretin-2 receptor (Lin et al., 1999), and mice with deletion of the Hcrt gene exhibit symptoms of narcolepsy (Chemelli et al., 1999).

The hypocretin peptides, also known as the orexins, are produced exclusively by neurons located in the lateral hypothalamus (LH) (De Lecea et al., 1998; Peyron et al., 1998; Sakurai et al., 1998). A single gene encodes Hcrt, which is cleaved by proteolytic processing into two smaller peptides, hypocretin-1 (orexin A) and hypocretin-2 (orexin B) (De Lecea et al., 1998; Sakurai et al., 1998). Hypocretin/orexin-containing neurons project to the entire brain and spinal cord (De Lecea et al., 1998; Date et al., 1999; Nambu et al., 1999).

Hcrt-containing neurons are located in a part of the brain that von Economo considered to be a “wake” center (von Economo, 1930). However, his findings were ignored because lesions of the posterior hypothalamus have to date yielded inconsistent effects on sleep and wakefulness. For instance, Ranson (1939), Nauta (1946), and Shoham and Teitelbaum (1982) observed behavioral signs of sleepiness after electrolytic lesions of the posterior hypothalamus but did not report the daily amounts of sleep, which makes it difficult to conclude whether the behavioral symptoms were isolated or pervasive. When long-term electroencephalogram (EEG) sleep recordings were made, increased wakefulness and reduced REM sleep were obtained after electrolytic lesions of the LH (McGinty, 1969; Danguir and Nicolaidis, 1980; Jurkowlaniec et al., 1994). Swett and Hobson (1968) reported increased SWS accompanied by behavioral rigidity in some cats, but their electrolytic lesions encompassed the ventral tegmental area. Excitotoxic lesions of the posterior hypothalamus with ibotenic acid have also produced transient effects, such as increased sleep for 1–4 d followed by increased wakefulness; REM sleep was increased only during the first 3–21 hr (Sallanon et al., 1988; Denoyer et al., 1991).

The inconsistent effects on sleep after electrolytic or excitotoxic lesions of the posterior hypothalamus or LH might have occurred because the methods used to make the lesion did not destroy the appropriate neurons. Moreover, some neurons are resistant to lesion by excitotoxins such as ibotenate (Yanai et al., 1997). In the present study, to more effectively target the Hcrt system, the ribosome-inactivating protein saporin (SAP) (Stirpe et al., 1992) was conjugated to the hypocretin/orexin receptor binding ligand hypocretin-2/orexin-B (Hcrt2) to lesion Hcrt receptor-bearing neurons. The LH contains a high concentration of Hcrt receptor mRNA (Trivedi et al., 1998) and immunoreactivity (Hervieu et al., 2001), and the Hcrt-immunoreactive (ir) axons make synaptic contacts with Hcrt-containing perikarya (Horvath et al., 1999), indicating the presence of the Hcrt receptor on Hcrt neurons. When the Hcrt2-SAP was administered to the LH of rats, the toxin lesioned LH neurons, including the Hcrt-ir neurons, and produced symptoms that are characteristic of narcolepsy. These findings identify the LH as promoting wakefulness and inhibiting REM sleep and demonstrate that the Hcrt2-SAP conjugate is a useful tool for investigating the Hcrt system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experiment 1: In vitro analysis of binding of Hcrt2-SAP

Hypocretin receptor-containing cells. Stably transfected cell lines expressing the hypocretin/orexin receptor 1 (HcrtR1/OX1R) or receptor 2 (HcrtR2/OX2R) are described by Sakurai et al. (1998). Chinese hamster ovary cells expressing HcrtR1/OX1R or HcrtR2/OX2R (gifts from Dr. M. Yanagisawa, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX) were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum at SRI International. For fixation, 2.5 × 106 cells/sample were washed with 1 ml of fluorescent-activated cell sorting (FACS) buffer (2% fetal bovine serum in PBS) per 106 cells. The buffer was then removed and cells were fixed by resuspension of the pellet in 1% paraformaldehyde (1 ml/106cells). After a 15 min incubation at 4°C, an equal volume of FACS buffer was added; cells were pelleted after thorough mixing. The pellets were washed as described above and resuspended in ice-cold 90% ethanol (1 ml/106 cells). After a 1 hr incubation at 4°C, an equal volume of FACS buffer was added; cells were pelleted after mixing. The pellets containing the fixed cells were washed again, resuspended in 200 μl of FACS buffer per sample (2.5 × 106 cells), and shipped to Advanced Targeting Systems for analyses.

To identify whether the Hcrt2-SAP bound to another peptide receptor, Kirsten murine sarcoma virus transformed rat kidney epithelial (KNRK) cells stably transfected with the substance P [neurokinin-1 (NK-1)] receptor (a gift from Dr. Nigel Bunnett, University of California, San Francisco, CA) were used (Wiley and Lappi, 1997).

FACS analysis. FACS analysis was performed at Cytometry Research LLC (San Diego, CA). Adherent cells were detached using CellStripper (Cellgro; Mediatech, Herndon, VA) and counted. A total of 2.5 × 106 cells/sample were washed with FACS buffer. Hcrt2-SAP or substance P attached to saporin (SP-SAP) was applied to the cells at a final concentration of 100 nm in 200 μl of FACS buffer. Samples were incubated for 1 hr at 4°C. Samples were washed twice with 1 ml of FACS buffer. A chicken anti-saporin antibody (Advanced Targeting Systems) was applied at a dilution of 1:50 in 100 μl of FACS buffer. Samples were incubated for 1 hr at 4°C and then washed as described previously. Rabbit anti-chicken IgY conjugated to FITC (Chemicon, Temecula, CA) was applied at a 1:50 final dilution in 100 μl of FACS buffer. Samples were incubated for 30 min at 4°C and then washed as described previously. Cells were resuspended in 500 μl of FACS buffer and then run on a FACScan (Becton Dickinson, Richmond, CA). Data were analyzed using CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson).

Experiment 2: Time course of the effects of Hcrt2-SAP on hypothalamic neurons

Subjects. Male Sprague Dawley rats (400–450 gm) (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) were housed singly in Plexiglas cages with wood shavings; food and water were availablead libitum. The temperature in the room was 25°C and a 12 hr light/dark cycle (lights on from 7 A.M. to 7 P.M.; 100 lux) was maintained.

In 10 rats (under anesthesia with a cocktail of 0.75 mg/kg acepromazine, 2.5 mg/kg xylazine, and 22 mg/kg ketamine, i.m.), a unilateral injection of Hcrt2-SAP was made to the LH using a stereotaxic instrument; the rats were killed 2 (n = 3), 4 (n = 4), or 12 (n = 3) d later. The rats were perfused (after an overdose of Nembutal) with saline (100 ml) followed by 10% formalin (350 ml). The brains were carefully removed, placed overnight in the formalin solution, and then equilibrated in 30% sucrose solution at 4°C.

Microinjection sites. The Hcrt2-SAP conjugate (490 ng/0.5 μl; Advanced Targeting Systems) or pyrogen-free saline were delivered (0.5 μl) (Picospritzer; General Valve, Fairfield, NJ) using a glass micropipette (tip diameter of 20 mm). After injection the pipette was left in place for 5 min and then withdrawn slowly. A single injection was made in each rat in the LH (coordinates relative to bregma: anterior, −3.3 to −3.8 mm; lateral, 1.3–1.6 mm; ventral, 8.2–9.0 mm below the dura).

Immunohistochemistry. Tissue sections (30 mm thick) cut on a sliding microtome were incubated overnight at room temperature in the primary antibody (a one in five series for each primary antibody). After washing, the sections were placed in the secondary antibody for 1 hr (1:250) (Chemicon) followed by incubation in avidin–biotin complex for 1 hr (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). The DAB method was used to visualize the reaction product. The tissue sections were then counter-stained with a Nissl stain (Neutral Red), dehydrated in graded alcohols, and coverslipped. Control sections were reacted without the primary antibodies or in preadsorbed serum; no labeled neurons were evident. The specificity of the antibodies was further confirmed by the restriction of the labeled neurons to the posterior hypothalamus.

Antibodies. Rabbit anti-orexin-A (hypocretin-ir) (1:70,000; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Arlington Heights, IL), rabbit anti-adenosine deaminase (1:10,000; Chemicon); rabbit anti-melanin-concentrating hormone (MCH) (1:50,000; Chemicon), and rabbit anti-a melanocyte-stimulating hormone (a-MSH) (1:5000;Chemicon) were used.

Cell counts. One person (M. Malik) blind to the type of drug and site of injection counted all of the immunoreactive somata on the ipsilateral (injection side) and the contralateral side. At least 12 sections (a one in five series) that encompassed the rostral pole of the LH to the caudal pole of the tuberomammillary nucleus (TMN) were examined. All somata that were immunoreactive for the specific antigen [Hcrt, adenosine deaminase (ADA), MCH, or a-MSH] were counted, and the total numbers of cells were determined for each animal. For each animal, the cell counts obtained on the contralateral side (noninjected side) served as the control. A 10 square grid (50 μm/square) centered around the fornix was used to count the cells. For each animal, cell counts on the ipsilateral side were expressed relative to the contralateral side. Camera lucida drawings were made to identify the distribution of Hcrt, MCH, a-MSH, and ADA-ir neurons in the posterior hypothalamus using the Neurolucida program (Colchester, VT).

Experiment 3: Effects of bilateral injection of Hcrt2-SAP on sleep and wakefulness

Subjects. Twenty male Sprague Dawley rats were used in this experiment; housing conditions were the same as those described for experiment 2.

Surgery. The rats were implanted under anesthesia (cocktail of 0.75 mg/kg acepromazine, 2.5 mg/kg xylazine, and 22 mg/kg ketamine, i.m.) with electrodes to record the EEG and electromyogram (EMG), as described previously (Shiromani et al., 2000). At this time, bilateral injections of Hcrt2-SAP (490 ng/0.5 μl) or pyrogen-free saline were made to the LH; the injection procedure and target site were the same as in experiment 2. After the surgery the rats were returned to their home cages and continuous EEG and EMG recordings were collected for at least 2 weeks. Next the rats were perfused (after overdose of Nembutal), and formalin-fixed brains were used for histological analysis.

Analysis of sleep–wake states. Contralateral frontal–occipital EEG screw electrodes were used for EEG acquisition. The EEG data were filtered at 70 Hz (low-pass filter) and 0.3 Hz (high-pass filter) using a Grass electroencephalograph (Grass Instruments, Quincy, MA) and were continuously sampled at 128 Hz. The 24 hr EEG and EMG recordings obtained on days 2, 6, and 14 after injection were scored manually as described previously (Shiromani et al., 2000) in 12 sec epochs for awake, SWS, and REM sleep by one person (E. Winston) blind to the type of drug administered to the rats. Wakefulness was identified by the presence of desynchronized EEG and high EMG activity. Slow-wave sleep consisted of high-amplitude slow waves together with a low EMG tone relative to waking. REM sleep was identified by the presence of desynchronized EEG and/or θ activity coupled with low EMG relative to slow-wave sleep. The amount of time spent in wakefulness, SWS, and REM sleep was determined for each hour. To determine whether there was a change in the amplitude of the diurnal rhythm of sleep, the ratio of sleep during the light-on period versus the light-off period was calculated (Table1). δ power (0.5–4 Hz) was calculated using the ICELUS software system (M. Opp, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI). After the EEG data were scored, the code was broken to reveal the identity of each rat. ANOVA and t tests with Bonferroni corrections (where appropriate) were used to compare changes in sleep parameters.

Table 1.

Changes in light–dark ratios in rats with lateral hypothalamic injections of saline or Hcrt2-SAP

| Group | 6 d after injection | 14 d after injection | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wake | SWS | REM | EEG δ power in SWS | Wake | SWS | REM | EEG δ power in SWS | |

| Hcrt cell loss >60% (n = 9) | 1.00 ± 0.12* | 1.25 ± 0.15* | 0.46 ± 0.09* | 1.12 ± 0.08* | 0.90 ± 0.10* | 1.39 ± 0.17* | 0.45 ± 0.05* | 1.21 ± 0.07* |

| Hcrt cell loss <30% (n = 3) | 0.38 ± 0.09 | 3.56 ± 1.00 | 2.63 ± 1.30 | 1.63 ± 0.16 | 0.33 ± 0.04 | 3.73 ± 0.69 | 3.77 ± 0.65 | 1.54 ± 0.27 |

| Saline (n = 8) | 0.43 ± 0.03 | 2.99 ± 0.28 | 3.15 ± 0.61 | 1.68 ± 0.17 | 0.36 ± 0.03 | 3.28 ± 0.37 | 4.41 ± 0.76 | 1.80 ± 0.21 |

Values (±SEM) represent ratio of wakefulness, SWS, or REM sleep percentage during light-on period versus its corresponding value during light-off period. For EEG δ power, the values represent the ratio of δ power during the 2 hr period after lights on (7 A.M. to 9 A.M.) versus the 2 hr period after lights off (7 P.M. to 9 P.M.). For δ power, the 2 hr time points represented the peak and nadir of the δ power across the 24 hr in saline-treated rats, a finding that is consistent with the waxing and waning of EEG δ power (Borbely, 1994).

p < 0.05, significant difference compared with the values of the saline group.

The criteria used to identify SOREMPs were based on a combination of electrophysiological and behavioral observations and were modeled after those used in humans, because no such criteria exist for rats. In humans, SOREMPS are defined as episodes of REM sleep occurring within a 15 min window after the onset of sleep (Carskadon et al., 1986). In young normal Sprague Dawley rats, the duration of wake (day, 1.92 ± 0.1 min; night, 6.33 ± 0.47; data from Shiromani et al., 2000) and SWS (day, 3.83 ± 0.32; night, 2.8 ± 0.25; data fromShiromani et al., 2000) bouts are considerably shorter, making it necessary to modify the criteria. Accordingly, a SOREMP in the rat was identified as a REM sleep episode in the day or night that occurred after ≥2 min of wakefulness with <2 min of an intervening episode of SWS. The 2 min duration of wake and SWS bouts was based on the duration of these bouts in normal Sprague Dawley rats (Shiromani et al., 2000), and this duration was also observed in the saline-treated rats in the present study (Table 2). In addition to these electrophysiological criteria, a behavioral determination of a SOREMP was made when the videotape showed that the rat was lying down, had irregular respiration, and had phasic motor twitches. A Sony video camera (CCD-TRV16; Sony, Tokyo, Japan) with the capability to record in darkness was used to record the animal's behavior. In the video clips, the EEG and EMG are superimposed on the behavior to facilitate identifying the behavioral state of the rat.

Table 2.

Average (±SEM) number of transitions to SWS, REM sleep, or wakefulness and duration of wakefulness, SWS, or REM sleep in rats administered Hcrt2-SAP in the LH

| Group | Average number of transitions | Average duration of bouts (min) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W-SWS | SWS-REM | SWS-W | Wake | SWS | REM | |

| Light-off period | ||||||

| Hcrt cell loss >60% (n = 9) | 93.7 ± 8.8* | 41.2 ± 3.9 | 52.5 ± 6.9* | 3.8 ± 0.5* | 3.2 ± 0.3* | 1.9 ± 0.1* |

| HcrtT cell loss <30% (n = 3) | 46.7 ± 8.8 | 24.7 ± 5.2 | 22.0 ± 4.2 | 12.4 ± 3.4 | 2.9 ± 0.4 | 1.7 ± 0.6 |

| Saline (n = 8) | 56.3 ± 4.6 | 30.6 ± 4.2 | 25.6 ± 3.1 | 10.3 ± 0.9 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.1 |

| Light-on period | ||||||

| Hcrt cell loss >60% (n = 9) | 98.5 ± 7.1 | 20.5 ± 2.8* | 78.0 ± 5.9* | 3.6 ± 0.8 | 3.6 ± 0.2 | 1.7 ± 0.2 |

| Hcrt cell loss <30% (n = 3) | 97.0 ± 6.6 | 51.0 ± 6.4 | 46.0 ± 4.2 | 2.0 ± 0.4 | 4.3 ± 0.2* | 1.5 ± 0.1 |

| Saline (n = 8) | 116.0 ± 5.0 | 70.1 ± 3.6 | 45.9 ± 2.6 | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 3.1 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.1 |

W, Wakefulness.

p < 0.05, significance for each group compared with its respective saline group.

Immunohistochemistry and cell counts. The tissue was reacted for visualization of Hcrt or adenosine deaminase-ir neurons as described in experiment 2. The cell counts were performed as noted in experiment 2 by a person (M. Malik) who was blind to the type of drug administered. In this experiment, comparisons were made with the saline-injected rats.

In situ hybridization. To identify loss of Hcrt receptor mRNA, a 1420 bp region of the Hcrt 2 receptor was amplified by PCR, cloned into pBluescript, and used to generate cRNA for in situ hybridization. The cRNA was transcribed from a linearized plasmid using T7 (antisense) or T3 (sense) RNA polymerase and35S-UTP with a riboprobe kit (Promega, Madison, WI). Acetylated tissue was incubated overnight at 55°C in hybridization buffer containing probe (106cpm/ml); washed successively in 2× SSC–1 mm DTT (50°C, 1 hr), 0.2× SSC–1 mm DTT (55°C, 1 hr), and 0.2× SSC–1 mm DTT (60°C, 1 hr); dehydrated; exposed to film; and developed after 72 hr. The slides were then coated with Kodak NTB emulsion (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY) and developed after 4 weeks. To determine the specificity of labeling, adjacent tissue sections were also hybridized with the sense probe. No labeling was evident using the sense probe (data not shown).

RESULTS

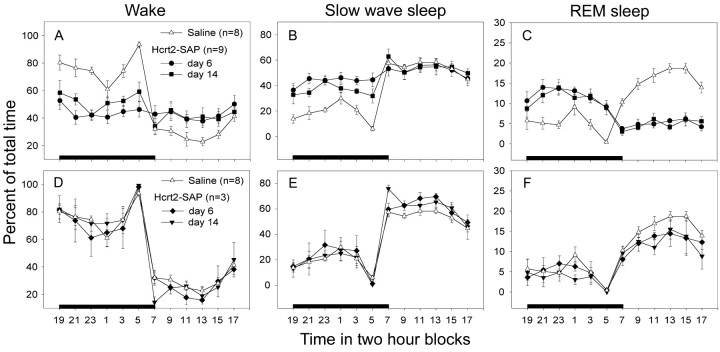

Experiment 1: In vitro analysis of binding of Hcrt2-SAP

FACS analysis was performed on cells transfected with the Hcrt receptors or NK-1 receptor. In this assay, the fluorescent probe was attached to antibodies to saporin, such that the entire Hcrt2-SAP complex must be intact for a read-out to occur. Figure1 shows that the Hcrt2-SAP binds to the HcrtR2/OX2 receptor and, to a lesser degree, to the HcrtR1/OX1R (Fig. 1A). These data are consistent with the properties of the ligand alone (Sakurai et al., 1998). There is no binding of Hcrt2-SAP to cells that are transfected with the substance P receptor, indicating lack of cross-reactivity with another peptide receptor. As expected, SP-SAP bound to substance P receptor (NK-1)-containing KNRK cells (Mantyh et al., 1997) (Fig. 1B). These data demonstrate that binding of Hcrt2-SAP is specific for the Hcrt receptors.

Fig. 1.

FACS analysis of Hcrt2-SAP binding to Hcrt receptor-transfected cells and cells expressing the NK-1 receptor. Binding was measured using FITC-labeled anti-saporin antibody to determine whether the entire conjugate was bound to the receptors.A, Hcrt2-SAP binding to cells transfected with the HcrtR1/OX1 receptor (green line) or the HcrtR2/OX2 receptor (red line). HcrtR2/OX2 cells not exposed to Hcrt2-SAP lack binding (blue line). B, Hcrt2-SAP does not bind to cells transfected with the NK-1 receptor (blue line). As a positive control, SP-SAP is shown binding to these cells.

Experiment 2: Time course of the effects of Hcrt2-SAP on hypothalamic neurons

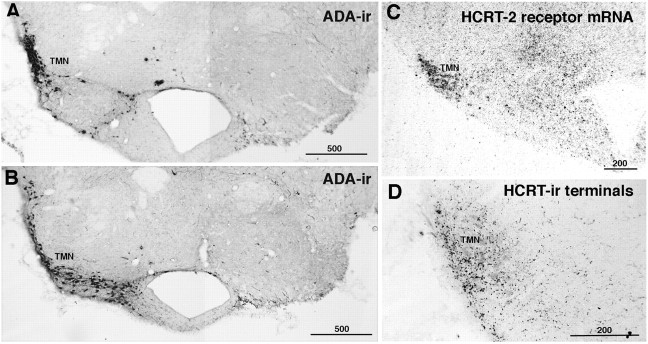

To identify the cytotoxic effects in vivo, the Hcrt2-SAP was administered unilaterally to the hypothalamic regions known to contain the Hcrt receptor. The neurons in the TMN were counted because they do not contain Hcrt but possess the receptor, as demonstrated by the presence of Hcrt receptor mRNA in the TMN (Fig.2C). The TMN neurons represent a homogenous population of densely packed neurons that contain the enzyme ADA (Senba et al., 1985) (Fig. 2A,B), and Hcrt fibers densely innervate this nucleus (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

Effects of Hcrt2-SAP on Hcrt receptor mRNA-containing neurons in the TMN. Virtually all of the TMN neurons contain adenosine deaminase (A, B,left side). Hcrt receptor mRNA is present in these neurons (C), and Hcrt fibers and terminals innervate this nucleus (D). A unilateral administration of Hcrt2-SAP to the TMN eliminated these neurons (A, B, right side). Scale bars are in micrometers.

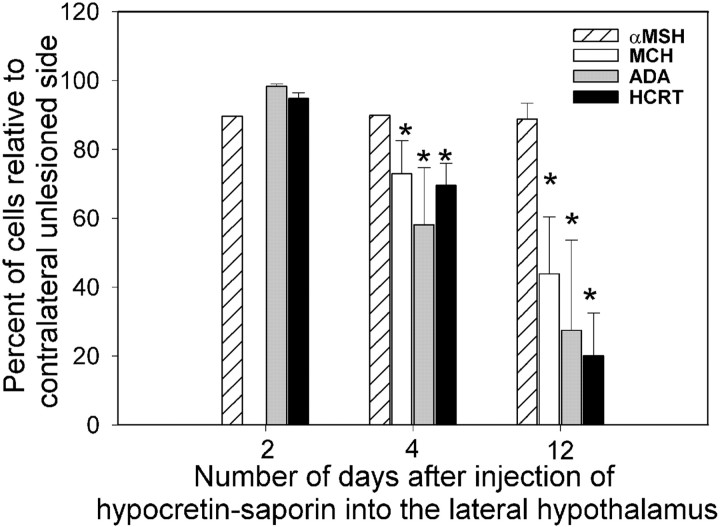

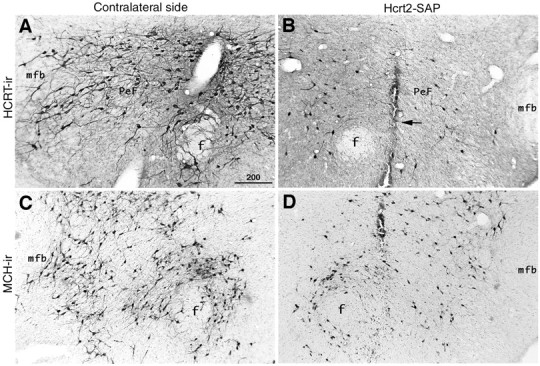

Figure 3 summarizes the time-dependent loss of specific markers of neuronal phenotypes in the posterior hypothalamus. Comparisons made to the contralateral uninjected side indicated that rats killed on day 2 after injection (n= 3) had little loss of Hcrt-ir or ADA-ir neurons. However, by day 4 after injection there was a significant decrease (31%) in the number of Hcrt-ir neurons (paired t test with contralateral nonlesioned side, t = 6.07; df = 3;p < 0.009; power = 96.8). By day 12 there was a 76% loss of Hcrt-ir neurons (paired t test,t = 7.7; df = 2; p < 0.001; power = 94.6). ADA-ir neurons also showed a similar time course of neuronal marker loss. Representative photomicrographs from animals with unilateral Hcrt2-SAP lesions are presented in Figure4A,B. The time course of loss of markers is consistent with that of other targeted saporin conjugates (Waite et al., 1994; Mantyh et al., 1997).

Fig. 3.

Time course of the effects of Hcrt2-SAP on markers of neuronal phenotypes in the posterior hypothalamus. A unilateral injection of Hcrt2-SAP (490 ng/0.5 μl in a volume of 0.5 μl) was made to the LH, and rats were killed 2, 4, or 12 d later. Adjacent tissue sections (30 μm thick) were processed for visualization of Hcrt-, MCH-, a-MSH-, or ADA-containing neurons. The contralateral uninjected side served as a control. There was a time-dependent loss of neurons in the injection zone beginning on day 4 after injection, which is consistent with the effects of saporin conjugated to other ligands. *p < 0.05.

Fig. 4.

Effects of Hcrt2-SAP on hypocretin (HCRT-ir) (A, B) and melanin-concentrating hormone (MCH-ir) (C, D) -containing neurons in the LH.B and D represent the side receiving the Hcrt2-SAP injection; A and C represent the contralateral, uninjected side. The arrow inB points to the micropipette tract. The tissue is from a representative rat that was examined 12 d after unilateral microinjection of Hcrt2-SAP in the LH. Adjacent tissue sections were processed for visualization of Hcrt- or MCH-immunoreactive neurons.f, Fornix; mfb, medial forebrain bundle;PeF, perifornical area. The scale bar inA (in micrometers) applies to the other photomicrographs also.

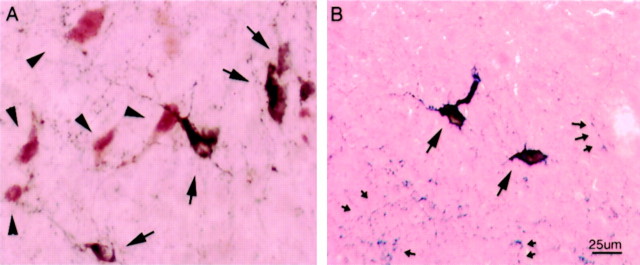

To identify whether the toxin affected other neuronal markers within the injection area, neurons containing melanin-concentrating hormone (MCH-immunoreactive) (Fig. 4C,D) or a-MSH (Fig. 5) were counted. MCH- and a-MSH-immunoreactive neurons are located in close proximity to the Hcrt neurons but are separate from the Hcrt neurons and also distinct from each other (Elias et al., 1998). MCH neurons were found to be decreased after unilateral Hcrt2-SAP injections (Figs. 3 and 4C,D) with the same time course as the Hcrt and TMN neurons, but a-MSH neurons were spared (Figs. 3 and5). This suggests that some neurons are more sensitive to the toxin, and this sensitivity may depend on the presence of the Hcrt receptor and/or the subtype of Hcrt receptor on the neuron.

Fig. 5.

Effects of Hcrt2-SAP on a-MSH (arrows) and Hcrt (arrowheads) neurons in the LH. A represents the contralateral uninjected side and B represents the side receiving the Hcrt2-SAP injection. Tissue sections from rats with a unilateral injection of Hcrt2-SAP in the LH were processed for visualization of both Hcrt (brown reaction product) and a-MSH (black-brown reaction product) neurons. Note the close proximity of the Hcrt neurons to the a-MSH neurons (A) and the lack of Hcrt-ir neurons in the side administered Hcrt2-SAP (B). The small arrows inB identify a-MSH terminals and varicosities.

Experiment 3: Effects of bilateral injection of Hcrt2-SAP on sleep and wakefulness

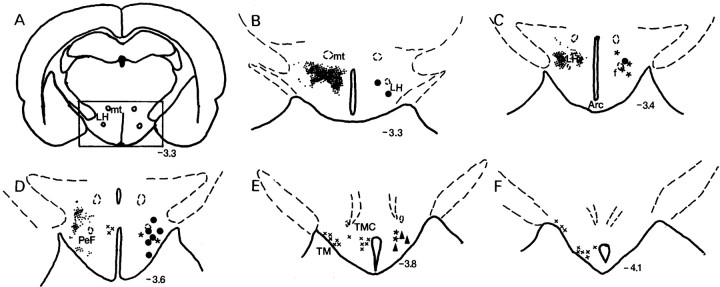

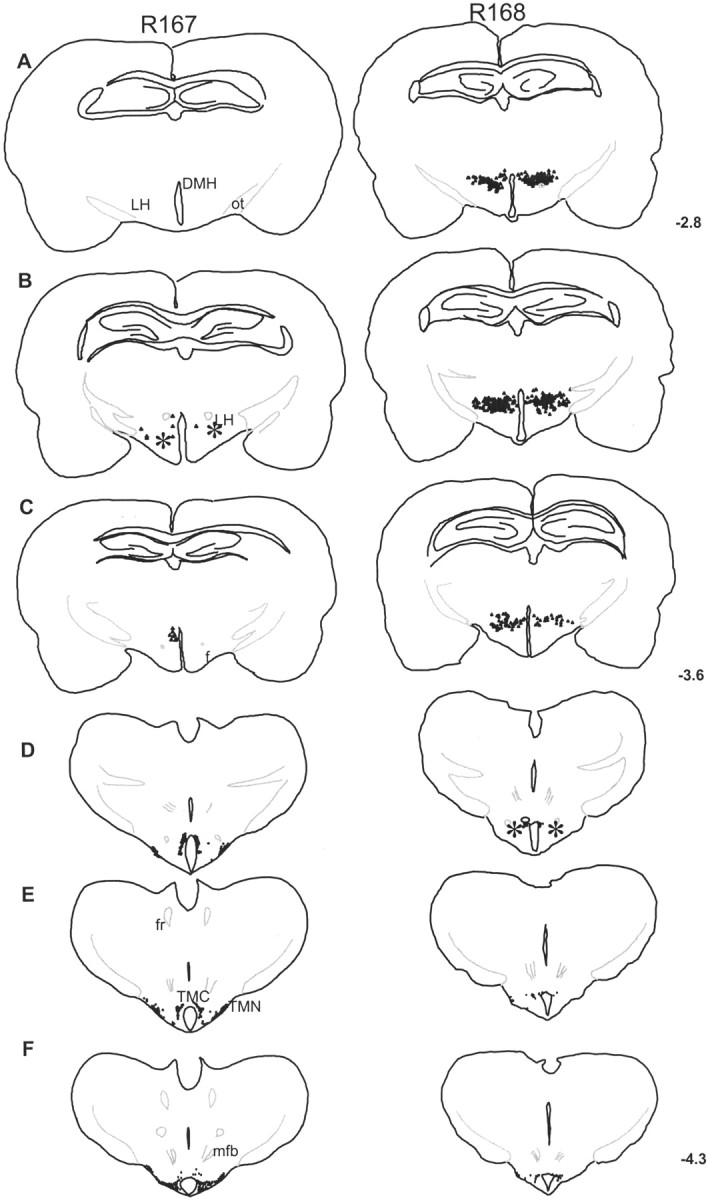

The location of the injection sites is schematically illustrated in Figure 6. Figure7 is a camera lucida drawing detailing the loss of the Hcrt-ir cells in two representative rats.

Fig. 6.

Camera lucida drawings of injection sites as well as Hcrt-ir neurons (small dots) in the LH.Large filled circles represent the sites for which application of Hcrt2-SAP produced >60% Hcrt cell loss (Hcrt-x rats).Filled triangles represent the sites for which Hcrt2-SAP injections produced <30% Hcrt cell loss. Asterisksrepresent the saline injection sites. The location of Hcrt neurons (small dots) and ADA-ir neurons (marked by ×) is shown on the left side of the drawings.Arc, Arcuate nucleus; f, fornix;mt, mammillothalamic tract; PeF, perifornical area; TM, tuberomammillary nucleus; TMC, TM central portion. The nomenclature is according to the rat atlas of Paxinos and Watson (1986).

Fig. 7.

Camera lucida drawing of the posterior hypothalamus from two representative rats with Hcrt2-SAP injections.Asterisks denote the site of injection. In rat R167, the toxin eliminated virtually all of the Hcrt-ir cells (99% loss) but spared the adenosine deaminase-ir cells in the TMN (0% loss). In rat R168, the administration of the toxin to a slightly more caudal region produced a 30% loss of Hcrt-ir cells and a 63% loss of adenosine deaminase-ir cells in the TMN. DMH, Dorsomedial hypothalamus; mfb, medial forebrain bundle;ot, optic tract; TMC, tuberomammillary nucleus central portion.

Extent of loss of Hcrt neurons

Animals administered bilateral injections of Hcrt2-SAP in the hypothalamus were compared with rats receiving injections of saline into the hypothalamus (n = 8; average number of Hcrt-ir cells per rat was 1324.0 ± 57.6). Animals administered bilateral injections of Hcrt2-SAP were divided into two groups: rats with >60% loss of Hcrt neurons (represented as Hcrt-x; n = 9; average number of Hcrt-ir cells per rat was 155.6 ± 55.6) and rats with <30% Hcrt cell loss (n = 3; average number of Hcrt-ir cells per rat was 928.0 ± 62.7). A one-way ANOVA identified a significant between-group difference (F(2,16) = 116.06; p< 0.001) and Tukey's post hoc comparison revealed that all three groups were significantly different from each other with respect to the number of Hcrt-ir neurons (p < 0.001).

Hcrt2-SAP administered bilaterally to the LH produced a loss of Hcrt receptor mRNA (Fig. 8, A vsD) and of Hcrt-ir neurons (Fig. 8, B vsE). We estimate that the loss of Hcrt receptor mRNA-containing neurons extended along a radius of 0.8–1.0 mm, and this was sufficient to knock out the Hcrt-ir cells with boundaries extending from −2.0 to −4.0 posterior to bregma. Consistent with the loss of Hcrt-ir somata, there was a loss of Hcrt-ir fibers and terminals at target sites, such as the locus ceruleus (Fig. 8,C vs F).

Fig. 8.

Photomicrographs of hypothalamic sections depicting Hcrt receptor mRNA (A, D), Hcrt-ir neurons (B, E), and Hcrt-ir fibers in the locus ceruleus (C,F). In A–C, tissue from saline-treated rats is depicted. D–F depict tissue from a representative rat with Hcrt2-SAP administered to the LH.A depicts an autoradiogram image of Hcrt receptor mRNA labeling in the LH (coronal section). The region outlined by thebox in A represents the area in which Hcrt-ir neurons are present (B). Images inB and F are presented in reverse contrast. Hcrt2-SAP applied to the LH eliminated Hcrt receptor mRNA labeling (D) and Hcrt-ir neurons (E). Elimination of the Hcrt-ir neurons produced a loss of Hcrt-ir fibers at target sites such as the locus ceruleus (LC). In control rats, the LC is heavily innervated by Hcrt-ir fibers (C), but this innervation is lost after Hcrt2-SAP lesions of the Hcrt-ir neurons in the LH (F). 3V, Third ventricle;4V, fourth ventricle; Amyg, amygdala;f, fornix; MHb, medial habenula;mt, mammillothalamic tract; PeF, perifornical nucleus.

Analysis of sleep data

Based on the time course of Hcrt neuronal loss after toxin administration (experiment 2 and Fig. 3), the sleep data obtained on days 2, 6, and 14 after injection were analyzed. There were no significant differences in sleep–wakefulness on day 2 after injection between the saline- and Hcrt2-SAP-treated rats. This indicates that both groups had similar sleep levels after the surgery and before day 4, when a noticeable cell loss was first evident in rats administered Hcrt2-SAP (Fig. 3). In the saline-treated rats, there were no significant differences in sleep between day 6 and day 14. Therefore, the data from these days were combined.

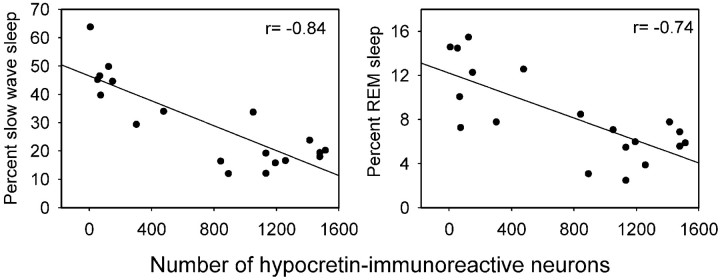

Figure 9 summarizes the diurnal distribution of sleep–wake states across the 24 hr in the three groups. As is typical of nocturnal rodents, saline-treated rats (n = 8) demonstrated a clear diurnal distribution of sleep–wake states, with the rats exhibiting more wakefulness at night and more sleep during the day. However, the Hcrt-x rats (n = 9) (Fig. 9A–C) demonstrated very little difference in sleep–wakefulness during the day versus during the night. Table 1 summarizes the ratio of sleep–wake states during the day versus during the night. In the Hcrt-x rats, the ratio for wakefulness and SWS is close to 1, indicating a lack of a diurnal difference in these states (Table 1). For REM sleep, the ratio is <1, indicating more REM sleep at night in the Hcrt-x rats (Table 1). The diurnal difference in EEG δ power (0.3–4 Hz) during periods of SWS was also attenuated in the Hcrt-x rats (Table 1).

Fig. 9.

Mean (±SEM) percentage of wakefulness, SWS, and REM sleep during 24 hr in rats administered Hcrt2-SAP or saline in the posterior hypothalamus. The 24 hr are represented in 2 hr blocks. Thedark bar represents the 12 hr light-off period. Animals with a >60% decline in the number of Hcrt cells (A–C) experienced significantly more SWS and REM sleep at night compared with saline-treated rats. During the day the lesioned rats had as much SWS as controls but REM sleep was decreased. The night-time increase in sleep served to lessen the diurnal variation in sleep. In animals that had partial loss of Hcrt neurons (D–F), there was no change in sleep.

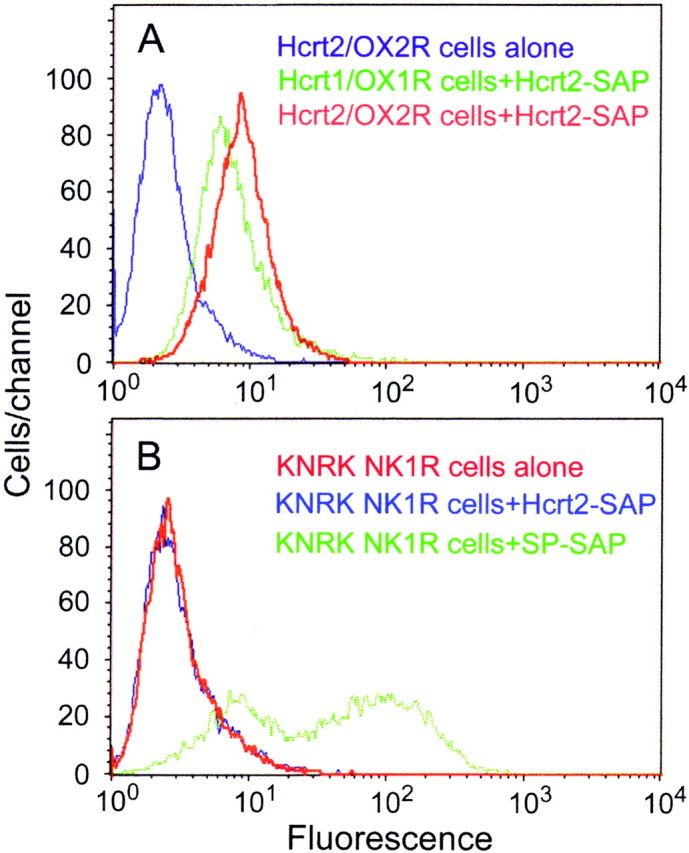

The day versus night difference in wakefulness was lost because Hcrt-x rats exhibited 2.3 times as much total sleep time as controls during the dark period (p < 0.001). These rats had significant increases in both SWS (2.4 times; p < 0.001) and REM sleep (2.2 times; p < 0.001) at night. To determine how the overall percentage changes in sleep occurred, we determined the number and average duration of bouts of wakefulness, SWS and REM sleep during the day and night (Table 2). At night, the increase in sleep occurred because the duration of wake bouts decreased while the duration of SWS and REM sleep bouts increased (see Table 2for significance). Regression analysis across all animals with lateral hypothalamic injections (n = 20) revealed a significant inverse relationship between the number of Hcrt-ir neurons and SWS (r = −0.84; df = 19; p < 0.01) and REM sleep (r = −0.74; df = 19;p < 0.01) during the dark period (Fig.10).

Fig. 10.

Relationship between sleep states (SWS and REM sleep) during the dark period and the numbers of Hcrt-ir cells in the LH. There was a significant inverse relationship between the numbers of Hcrt cells and sleep states.

During the day the Hcrt-x- and saline-treated rats had similar amounts of SWS. However, in the Hcrt-x rats sleep was significantly fragmented, as evidenced by a twofold increase in the number of transitions from SWS to waking (p < 0.01; Table 2). The increased awakenings during the day would prevent REM sleep from occurring (Mistlberger et al., 1987) and indeed, Hcrt-x rats had two-thirds fewer REM sleep bouts than saline-injected controls (p < 0.001; Table 2). Although these rats had significantly fewer REM sleep bouts, the lengths of individual REM sleep bouts were not different compared with saline rats (Table 2). Thus, during the day (the animal's major sleep period), the sleep of Hcrt-x rats was highly fragmented, with frequent awakenings and fewer REM sleep bouts. At night, the Hcrt-x rats were awake less and slept more than saline-treated rats. When averaged over the 24 hr period, the Hcrt-x rats had significantly more SWS (36% increase) compared with saline-treated rats (p < 0.01) but had a slight (17%) decrease in the REM sleep amounts (p < 0.05). The emergence of the behavioral effects in the Hcrt-x rats corresponded with the time course of the loss of Hcrt-ir cells in the LH.

The day and night levels of sleep in rats with partial (30%) loss of Hcrt neurons were not different compared with saline-treated rats (Fig.9D–F). However, when averaged over the 24 hr period, these rats had a small increase in SWS (6% increase; p< 0.05) and a decrease in REM sleep (26% decrease; p< 0.01) on day 14.

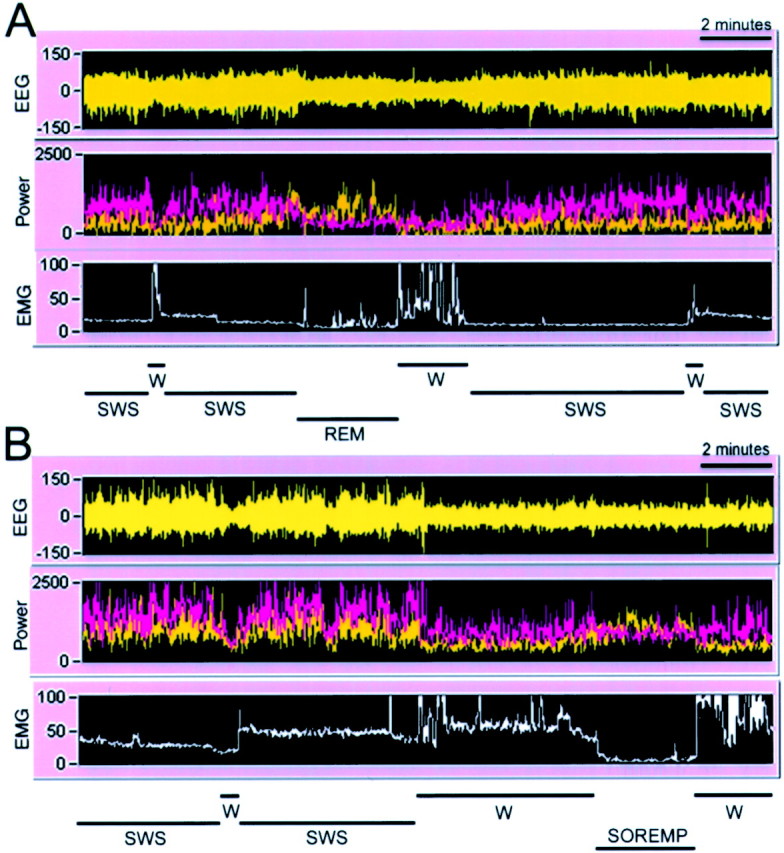

SOREMPs

SOREMPs are an important symptom of narcolepsy. Hcrt-x rats had on average 7.4 ± 1.5 SOREMPs per night and 3.2 ± 1.2 episodes during the day. Such episodes were rarely observed in saline-treated rats (day, 0.5 ± 0.2; night, 0.1 ± 0.1) or in rats with a <30% loss of Hcrt cells (day, 0.3 ± 0.3; night, 0.3 ± 0.3). A representative example of a normal REM sleep bout in a saline-treated rat versus a SOREMP in a Hcrt-x rat is presented in Figure 11. Representative examples of SOREMPs are evident in the video clips. The video recordings complement the data shown in Figure 11 by showing the behavioral repertoire exhibited by the rats before and after the SOREMPs. Moreover, the videos show the SOREMPs occurring at inappropriate times, including when the animals are feeding. Occasionally, the rats were found to exhibit “rocking” behavior as a prelude to a SOREMP (video 3). Such behavior has been described in Hcrt null mice (Chemelli et al., 1999). When the rats entered into a SOREMP episode, such episodes lasted 2.1 ± 0.2 min on average, which is similar to the duration of REM sleep bouts (Table 2). Thus, the SOREMPs were inappropriate triggering of REM sleep during wakefulness.

Fig. 11.

Alternation between wakefulness (W), SWS, and REM sleep in rats administered saline (A) or Hcrt2-SAP (B) into the LH. The figure represents a 20 min segment of a sleep–wake recording during the night (9:00 P.M.).A and B consist of a recording of the EEG, power of the EEG in the δ (0.3–4 Hz; pink) and θ (4–12 Hz; yellow) bands, and integrated activity of the nuchal muscles (EMG). The sleep–wake state determination, based on the relationship of the EEG, power, and EMG activity, is indicated at the bottom of each panel.A depicts a normal transition from SWS to REM sleep to wakefulness. B depicts a SOREMP exhibited by a Hcrt2-SAP-treated rat with a 90% loss of Hcrt-ir neurons. The SOREMP is identified by a loss of EMG tone (near zero), by increased θ activity, by a reduction in δ activity (pink band in B), and by an EEG amplitude that is similar to wakefulness. These criteria are used to identify REM sleep, including SOREMP, and they are not present during wakefulness or SWS. Note that the first brief bout of wakefulness in Bcannot be construed as REM sleep, because there is no θ activity and the EMG tone is rising, denoting that the rat woke up, albeit briefly.

The behavior of two rats was monitored until 45 d after injection, and an increase in sleep during the night (2.8 times increase in total sleep vs saline rats) and many SOREMPs were still evident (rats 171 and 181 in the video clips), suggesting a long-term change in sleep architecture. There was a significant negative correlation between the number of Hcrt cells in the LH and the number of SOREMPs during the night (r = −0.72; df = 19; p < 0.05).

Effects of loss of adenosine deaminase-immunoreactive neurons in the TMN on sleep

Hcrt2-SAP lesioned ADA-ir neurons in the TMN in many animals. The TMN neurons possess the Hcrt receptor (Fig. 2A,B) but do not contain Hcrt. However, there was no significant relationship (p < 0.171) between the loss of ADA-ir neurons in the TMN and SWS or REM sleep. There was also no correlation between the number of adenosine deaminase-containing cells in the TMN and the number of SOREMPs.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated in rats that lesion of the LH, which also eliminated the Hcrt-containing neurons, increased both SWS and REM sleep and produced SOREMPs. The effects were site-specific, because the application of the saporin conjugate to a slightly more caudal site in the posterior hypothalamus (Fig. 6, filled triangles) did not produce hypersomnolence. The caudal site (TMN) contains the Hcrt receptor, but application of the saporin conjugate to this site lesioned the receptor-bearing neurons (Fig. 2) but did not produce narcoleptic-like sleep behavior.

Hcrt2-SAP

Saporin is a protein isolated from the seeds of Saponaria officinalis (Stirpe et al., 1983). Extensive studies have shown that when saporin is coupled with antibodies or ligands that recognize cell-surface antigens or receptors, the conjugate binding is specific and initiates apoptosis in targeted cells (Waite et al., 1994;Bergamaschi et al., 1996; Mantyh et al., 1997).

In this study, saporin was conjugated to the peptide hypocretin-2 (orexin-B). Prepro-hypocretin is cleaved into two smaller peptides, hypocretin-1 (orexin-A) and hypocretin-2 (orexin-B). Hypocretin-2 is a linear peptide with a free N terminus that facilitates conjugation to saporin. Hypocretin-1 is more difficult to couple to saporin because both of its termini are blocked (Sakurai et al., 1998). Hcrt2-SAP bound to cells containing the Hcrt receptor but did not bind to cells that did not contain the Hcrt receptor (KNRK cells), indicating specificity of the Hcrt2-SAP. Cytotoxic effects in the brain were demonstrated by administering the Hcrt2-SAP to LH neurons known to contain the Hcrt receptor. Specific markers of some neuronal phenotypes were decreased within the Hcrt2-SAP injection area, whereas others (a-MSH) were spared (Fig. 3).

Diurnal rhythm changes in the Hcrt-x rats

In the Hcrt-x rats, the diurnal rhythm of wakefulness and SWS was severely attenuated (Table 1), primarily because of an increase in sleep during the night. As a result, Hcrt-x rats had increased SWS (>36%) over the 24 hr period. Even rats with <30% Hcrt neuronal loss had a slight increase in SWS (>6%) over the 24 hr period. SWS and REM sleep were found to correlate with a decline in Hcrt neurons. Although the Hcrt-SAP-treated rats exhibited hypersomnia, the 24 hr sleep of human narcoleptics is not different compared with normal controls (Aldrich, 1991). However, studies have not been done to specifically correlate sleep with the severity of Hcrt neuronal loss in human narcoleptics.

The diurnal rhythm of EEG δ power, a measure of sleep homeostasis (Borbely, 1994) was attenuated in the Hcrt-x rats (Table 1). However, there were no changes in the overall levels of δ power compared with saline-treated rats. δ power was not measured in Hcrt null mice (Chemelli et al., 1999). The Hcrt-x rats had an increase in both SWS and REM sleep during the normal night-active period, and daytime sleep was highly fragmented with frequent arousals. Human narcoleptics also exhibit excessive sleepiness and SOREMPs during the day, and night-time sleep is very fragmented (Aldrich, 1991). Thus, in the Hcrt-x rats the sleep architecture is similar to what occurs in narcolepsy.

Because narcoleptics are sleepy during the wake–active period, it is hypothesized that in narcolepsy the circadian mechanism for arousal is impaired (Broughton et al., 1998). The diurnal rhythm of sleep–wakefulness is regulated by the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), the circadian pacemaker. Lesions of the SCN eliminate the day–night variation in sleep, but such lesions have never been shown to produce SOREMPs (Coindet et al., 1975; Mistlberger et al., 1987). Thus, it is unlikely that the night-time hypersomnolence or the SOREMPs in the Hcrt-x rats were attributable to lesions of the SCN. In narcolepsy, the circadian clock functions normally (Dantz et al., 1994).

A possible explanation for the attenuation of the day–night sleep rhythm is that the lesion reduced the circadian drive from the SCN on the systems of arousal, which may be dependent, at least in part, on release of Hcrt from the LH. If this is the case, weakening the circadian arousal drive, by lesion of the SCN or by Hcrt neuronal loss, should significantly shorten the bouts of wakefulness during the night and increase sleep. In the present study, the Hcrt-x animals had more sleep and shorter wake bouts (Table 2). SCN-lesioned monkeys also have substantially shorter wake-bout lengths (Edgar et al., 1993) and more total sleep time during the day (active) period. The SCN projects directly to the LH, although the strongest projections are to the medial portions, along the third ventricle (Watts et al., 1987) where Hcrt neurons are also present. A direct although small projection from the SCN to the Hcrt cells has been reported recently (Abrahamson et al., 2001), although these authors suggest that circadian input to posterior hypothalamic arousal systems more likely is mediated through the medial preoptic and/or anterior hypothalamic nuclei (Abrahamson and Moore, 2001). We suggest that the SCN might regulate wakefulness by providing a waking signal to the Hcrt neurons. Such a signal might activate the Hcrt neurons, which then release Hcrt at target neurons to maintain wakefulness. We have recently proposed a model in which the Hcrt neurons activate the monoaminergic and cholinergic systems (Kilduff and Peyron, 2000). Intracerebroventricular injection of Hcrt induces arousal (Hagan et al., 1999), and systemic application of hypocretin-1 to narcoleptic dogs reduces cataplexy and normalizes sleep (John et al., 2000).

SOREMPs

As in the murine model, the Hcrt-x rats had more SWS and REM sleep at night and multiple periods of behavioral arrest during purposeful behavior. In the Hcrt knock out mice, EEG recordings were not made during the periods of behavioral arrest, whereas in the present study, continuous EEG recording allowed identification of the periods of behavioral arrest as SOREMPs (see video clips and Fig. 11). Interestingly, Shoham and Teitelbaum (1982), who made electrolytic lesions that included primarily the LH, observed that the rats collapsed into sleep when engaged in a spontaneous behavior such as grooming (they referred to such behavior as “groom-arrest”). Based on the present study, such groom-arrest episodes may very well have been SOREMPs.

Specific incidences of cataplexy were not observed in either hypocretin/orexin null mutant mice or the Hcrt2-SAP-injected rats. However, in canine narcolepsy, specific incidences of cataplexy are triggered in response to food or play and are short, lasting on the average 23 sec (Wu et al., 1999). Stimuli that trigger cataplexy need to be identified in rodents. Alternatively, the brainstem effector neurons implicated in cataplexy (Wu et al., 1999) need to be directly targeted to produce clear cataplectic episodes.

Implications of these findings for narcolepsy

In previous studies lesions of the posterior hypothalamus did not consistently produce symptoms of narcolepsy (Ranson, 1939; Nauta, 1946;Swett and Hobson, 1968; McGinty 1969; Danguir and Nicolaidis, 1980;Shoham and Teitelbaum,1982; Sallanon et al., 1988; Denoyer et al., 1991; Jurkowlaniec et al., 1994). Given the emerging evidence that narcolepsy is associated with a dysfunction or loss of the Hcrt system, at either the receptor or the ligand level, it is very likely that in previous studies the appropriate neurons were not destroyed.

There are also other neurons in the LH, and one can begin to assess their role in narcolepsy. For instance, MCH-containing neurons overlap with the Hcrt neurons (Elias et al., 1998), and these neurons were lesioned in the present study by Hcrt2-SAP. However, it is unlikely that loss of the MCH neurons could have caused the sleep abnormalities in our rats or human narcoleptics, because these cells are present in human narcoleptics (Thannickal et al., 2000) and MCH knock out mice do not show behavior consistent with narcolepsy (Shimada et al., 1998).

Loss of the histamine-containing neurons is also not the cause of the hypersomnolence or increased REM sleep, because the number of histamine-containing neurons was counted and there was no relationship with narcoleptic symptoms. The TMN has been implicated in the regulation of sleep–wakefulness because antihistamines cause drowsiness and the TMN contains the only known collection of histaminergic neurons in the brain (Senba et al., 1985). The enzyme adenosine deaminase colocalizes with histamine and can be used to identify the histamine TMN neurons (Senba et al., 1985). Histamine microinjections into TMN targets such as the preoptic area produce a dose-dependent increase in wakefulness (Lin et al., 1994). The inhibition of histamine synthesis in the preoptic area increases sleep and decreases wakefulness (Lin et al., 1994). Histamine H1 and H2 receptors are postulated to mediate the arousal (Lin et al., 1994). TMN neurons have the highest discharge rate during waking and are virtually silent during sleep (Vanni-Mercier et al., 1984; Szymusiak et al., 1989; Sakai et al., 1990). The TMN is a major target of the Hcrt-containing neurons. The Hcrt receptor mRNA is localized to the TMN (Fig. 2A,B) and Hcrt2-SAP lesioned the TMN. However, destruction of these neurons does not produce hypersomnolence, SOREMP, or other narcoleptic symptoms.

The Hcrt-x rats in the present study share many features of sleep architecture present in human (Aldrich, 1991) and canine (Kaitin et al., 1986a,b) narcolepsy and in Hcrt gene knock out mice (Chemelli et al., 1999). In humans (Aldrich, 1991), dogs (Lin et al., 1999), and the knock out mice (Chemelli et al., 1999), narcoleptic symptoms are not evident until adulthood, yet in our study with adult rats, a site-directed lesion readily produced these symptoms within a few days. This observation indicates that an inherited gene defect need not be the only route by which narcolepsy can occur. Humans without any familial history of the illness can develop narcolepsy, leading to the suggestion that this is an autoimmune disorder influenced by environmental factors (Honda and Matsuki, 1998). Increased number of astrocytes are present in the LH of narcoleptic patients (Thannickal et al., 2000), and a close association with a human leukocyte antigen DQ allele, DQB1*0602, is considered a predisposing factor in human narcolepsy (Mignot et al., 1997).

In the only two available animal models of human narcolepsy (Chemelli et al., 1999; Lin et al., 1999), the dysfunction in the Hcrt system is inherited and is in the entire animal. These characteristics make it difficult to localize the subgroup of Hcrt-containing neurons and the associated circuits that may underlie the individual symptoms of narcolepsy. The Hcrt2-SAP conjugate provides a method of investigating the contribution of the Hcrt system to the regulation of behavior across various species. This could be useful in determining whether the network underlying sleep is conserved across species. Moreover, because the Hcrt neurons project to multiple sites, Hcrt-SAP can be used to identify the role of these target sites in behavior. The effects of the saporin conjugate on sleep are long lasting, and this model could be used to test pharmacological treatments for narcolepsy.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants NS30140, AG09975, AG15853, MH55772, and MH61755 and by the Medical Research Service of the Department of Veterans Affairs. We thank M. Malik, Jill Winston, Melissa Boyle, and Kristie Majer for expert technical assistance and E. Winston for data analysis. We thank Drs. Michael Charness and Gary Gilbert for critiquing an initial draft of this manuscript and Carlos Blanco-Centurion for helpful discussions.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Priyattam J. Shiromani, West Roxbury Veterans Affairs Medical Center, 1400 VFW Parkway, West Roxbury, MA 02132. E-mail: pshiromani@hms.harvard.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abrahamson EE, Moore RY. The posterior hypothalamic area: chemoarchitecture and afferent connections. Brain Res. 2001;889:1–22. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)03015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abrahamson EE, Leak RK, Moore RY. The suprachiasmatic nucleus projects to posterior hypothalamic arousal systems. NeuroReport. 2001;12:435–440. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200102120-00048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aldrich MS. The neurobiology of narcolepsy. Trends Neurosci. 1991;14:235–239. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(91)90121-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bergamaschi G, Perfetti V, Tonon L, Novella A, Lucotti C, Danova M, Glennie MJ, Merlini G, Cazzola M. Saporin, a ribosome-inactivating protein used to prepare immunotoxins, induces cell death via apoptosis. Br J Haematol. 1996;93:789–794. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1996.d01-1730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borbely AA. Sleep homeostasis and models of sleep regulation. In: Kryger MH, Roth T, Dement WC, editors. Principles and practice of sleep medicine. Saunders; Toronto: 1994. pp. 309–320. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Broughton R, Krupa S, Boucher B, Rivers M, Mullington J. Impaired circadian waking arousal in narcolepsy-cataplexy. Sleep Res Online. 1998;1:159–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carskadon MA, Dement WC, Mitler MM, Roth T, Westbrook P, Keenan S. Guideline for the multiple sleep latency test (MSLT): a standard measure of sleepiness. Sleep. 1986;9:519–524. doi: 10.1093/sleep/9.4.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chemelli RM, Willie JT, Sinton CM, Elmquist JK, Scammell T, Lee C, Richardson JA, Williams SC, Xiong Y, Kisanuki Y, Fitch TE, Nakazato M, Hammer RE, Saper CB, Yanagisawa M. Narcolepsy in orexin knockout mice: molecular genetics of sleep regulation. Cell. 1999;98:437–451. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81973-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coindet J, Chouvet G, Mouret J. Effects of lesions of the suprachiasmatic nuclei on paradoxical sleep and slow wave sleep circadian rhythms in the rat. Neurosci Lett. 1975;1:243–247. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Danguir J, Nicolaidis S. Cortical activity and sleep in the rat lateral hypothalamic syndrome. Brain Res. 1980;185:305–321. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)91070-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dantz B, Edgar DM, Dement WC. Circardian rhythms in narcolepsy: studies on a 90 minute day. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1994;90:24–35. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(94)90110-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Date Y, Ueta Y, Yamashita H, Yamaguchi H, Matsukura S, Kangawa K, Sakurai T, Yanagisawa M, Nakazato M. Orexins, orexigenic hypothalamic peptides, interact with autonomic, neuroendocrine, and neuroregulatory systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:748–753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.2.748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Lecea L, Kilduff TS, Peyron C, Gao X, Foye PE, Danielson PE, Fukuhara C, Battenberg EL, Gautvik VT, Bartlett FS, Frankel WN, Van den Pol AN, Bloom FE, Gautvik KM, Sutcliffe JG. The hypocretins: hypothalamus-specific peptides with neuroexcitatory activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:322–327. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Denoyer M, Sallanon M, Buda C, Kitahama K, Jouvet M. Neurotoxic lesion of the mesencephalic reticular formation and/or the posterior hypothalamus does not alter waking in the cat. Brain Res. 1991;539:287–303. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91633-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edgar DM, Dement WC, Fuller CA. Effect of SCN lesions on sleep in squirrel monkeys: evidence for opponent processes in sleep-wake regulation. J Neurosci. 1993;13:1065–1079. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-03-01065.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elias CF, Saper CB, Maratos-Flier E, Tritos NA, Lee C, Kelly J, Tatro JB, Hoffman GE, Ollmann MM, Barsh GS, Sakurai T, Yanagisawa M, Elmquist JK. Chemically defined projections linking the mediobasal hypothalamus and the lateral hypothalamic area. J Comp Neurol. 1998;402:442–459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hagan JJ, Leslie RA, Patel S, Evans ML, Wattam TA, Holmes S, Benham CD, Taylor SG, Routledge C, Hemmati P, Munton RP, Ashmeade TE, Shah AS, Hatcher CP, Hatcher PD, Jones DN, Smith MI, Piper DC, Hunter AJ, Porter RA, Upton N. Orexin A activates locus coeruleus cell firing and increases arousal in the rat. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:10911–10916. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.19.10911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hervieu GJ, Cluderay JE, Harrison DC, Roberts JC, Leslie RA. Gene expression and protein distribution of the orexin-1 receptor in the rat brain and spinal cord. Neuroscience. 2001;103:777–797. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00033-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Honda Y, Matsuki K. Genetic aspects of narcolepsy. In: Thorpy M, editor. Handbook of sleep disorders. Marcel Dekker; New York: 1998. pp. 217–234. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horvath TL, Diano S, Van den Pol AN. Synaptic interaction between hypocretin (orexin) and neuropeptide Y cells in the rodent and primate hypothalamus: a novel circuit implicated in metabolic and endocrine regulations. J Neurosci. 1999;19:1072–1087. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-03-01072.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.John J, Wu MF, Siegel JM. Systemic administration of hypocretin-1 reduces cataplexy and normalizes sleep and waking durations in narcoleptic dogs. Sleep Res Online. 2000;3:23–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jurkowlaniec E, Trojniar W, Tokarski J. Daily pattern of EEG activity in rats with lateral hypothalamic lesions. J Physiol Pharmacol. 1994;45:399–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaitin KI, Kilduff TS, Dement WC. Evidence for excessive sleepiness in canine narcoleptics. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1986a;64:447–454. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(86)90078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaitin KI, Kilduff TS, Dement WC. Sleep fragmentation in canine narcolepsy. Sleep. 1986b;9:116–119. doi: 10.1093/sleep/9.1.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kilduff TS, Peyron C. The hypocretin/orexin ligand-receptor system: implications for sleep and sleep disorders. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:359–365. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01594-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin JS, Sakai K, Jouvet M. Hypothalamo-preoptic histaminergic projections in sleep-wake control in the cat. Eur J Neurosci. 1994;6:618–625. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1994.tb00306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin L, Faraco J, Li R, Kadotani H, Rogers W, Lin X, Qiu X, deJong PJ, Nishini S, Mignot E. The sleep disorder canine narcolepsy is caused by a mutation in the hypocretin (orexin) receptor 2 gene. Cell. 1999;98:365–376. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81965-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mantyh PW, Rogers SD, Honore P, Allen BJ, Ghilardi JR, Li J, Daughters RS, Lappi DA, Wiley RG, Simone DA. Inhibition of hyperalgesia by ablation of lamina I spinal neurons expressing the substance P receptor. Science. 1997;278:275–279. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5336.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McGinty DJ. Somnolence, recovery, and hyposomnia following ventromedial diencephalic lesions in the rat. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1969;26:70–79. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(69)90035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mignot E, Hayduk R, Black J, Grumet FC, Guilleminault C. HLA DQB1*0602 is associated with cataplexy in 509 narcoleptic patients. Sleep. 1997;20:1012–1020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mistlberger RE, Bergmann BM, Rechtschaffen A. Relationships among wake episode lengths, contiguous sleep episode lengths, and electroencephalographic δ waves in rats with suprachiasmatic nuclei lesions. Sleep. 1987;10:12–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nambu T, Sakurai T, Mizukami K, Hosoya Y, Yanagisawa M, Goto K. Distribution of orexin neurons in the adult rat brain. Brain Res. 1999;827:243–260. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01336-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nauta JH. Hypothalamic regulation of sleep in rats: an experimental study. J Neurophysiol. 1946;9:285–316. doi: 10.1152/jn.1946.9.4.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nishino S, Ripley B, Overeem S, Lammers GJ, Mignot E. Hypocretin (orexin)deficiency in human narcolepsy. Lancet. 2000;355:39–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)05582-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Academic; New York: 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peyron C, Tighe DK, Van den Pol AN, De Lecea L, Heller HC, Sutcliffe JG, Kilduff TS. Neurons containing hypocretin (orexin) project to multiple neuronal systems. J Neurosci. 1998;18:9996–10015. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-23-09996.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peyron C, Faraco J, Rogers W, Ripley B, Overeem S, Charnay Y, Nevsimalova S, Aldrich M, Reynolds D, Albin R, Li R, Hungs M, Pedrazzoli M, Padigaru M, Kucherlapati M, Fan J, Maki R, Lammers GJ, Bouras C, Kucherlapati R, Nishino S, Mignot E. A mutation in a case of early onset narcolepsy and a generalized absence of hypocretin peptides in human narcoleptic brains. Nat Med. 2000;6:991–997. doi: 10.1038/79690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ranson SW. Somnolence caused by hypothalamic lesions in the monkey. Arch Neurol Psychiatr. 1939;41:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sakai K, ElMansari M, Lin JS, Zhang G, Vanni-Mercier G. The posterior hypothalamus in the regulation of wakefulness and paradoxical sleep. In: Mancia M, Marini G, editors. The diencephalon and sleep. Raven; New York: 1990. pp. 171–198. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sakurai T, Amemiya A, Ishii M, Matsuzaki I, Chemelli RM, Tanaka H, Williams SC, Richarson JA, Kozlowski GP, Wilson S, Arch JR, Buckingham RE, Haynes AC, Carr SA, Annan RS, McNulty DE, Liu WS, Terrett JA, Elshourbagy NA, Bergsma DJ, Yanagisawa M. Orexins and orexin receptors: a family of hypothalamic neuropeptides and G protein-coupled receptors that regulate feeding behavior. Cell. 1998;92:573–585. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80949-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sallanon M, Sakai K, Buda C, Puymartin M, Jouvet M. Increase of paradoxical sleep induced by microinjections of ibotenic acid into the ventrolateral part of the posterior hypothalamus in the cat. Arch Ital Biol. 1988;126:87–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Senba E, Daddona PE, Watanabe T, Wu JY, Nagy JI. Adenosine deaminase is a marker for histamine neurons in the rat. J Neurosci. 1985;5:3402. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-12-03393.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shimada M, Tritos NA, Lowell BB, Flier JS, Maratos-Flier E. Mice lacking melanin-concentrating hormone are hypophagic and lean. Nature. 1998;396:670–674. doi: 10.1038/25341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shiromani PJ. Sleep circuitry, regulation, and function: lessons from c-fos, leptin, and timeless. In: Morrison A, Fluharty C, editors. Progress in psychobiology and physiological psychology. Academic; San Diego: 1998. pp. 67–90. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shiromani PJ, Lu J, Wagner D, Thakkar J, Greco MA, Basheer R, Thakkar M. Compensatory sleep response to 12 h wakefulness in young and old rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000;278:R125–R133. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.278.1.R125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shoham S, Teitelbaum P. Subcortical waking and sleep during lateral hypothalamic “somnolence” in rats. Physiol Behav. 1982;28:323–333. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(82)90082-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stirpe F, Gasper-Campani A, Barbieri L, Falasca A, Abbondanza A, Stevens WA. Ribosome-inactivating proteins from the seeds of Saponaria officinalis L. (soapwort), of Agrostemma githago L. (corn cockle), and of Asparagus officinalis (asparagus) and from the latex of Hura crepitans L. (sandbox tree). Biochem J. 1983;216:617–625. doi: 10.1042/bj2160617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stirpe F, Barbieri L, Battelli MG, Soria M, Lappi DA. Ribosome-inactivating proteins from plants: present status and future prospects. Biotechnology. 1992;10:405–412. doi: 10.1038/nbt0492-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Swett CP, Hobson A. The effects of posterior hypothalamic lesions on behavioral and electrographic manifestations of sleep and waking in cats. Arch Ital Biol. 1968;106:283–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Szymusiak R, Iriye T, McGinty D. Sleep-waking discharge of neurons in the posterior lateral hypothalamic area of cats. Brain Res Bull. 1989;23:111–120. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(89)90169-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thannickal T, Moore RY, Nienhuis R, Ramanathan L, Gulyani S, Aldrich M, Cornford M, Siegel JM. Reduced number of hypocretin neurons in human narcolepsy. Neuron. 2000;27:460–474. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00058-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Trivedi P, Yu H, MacNeil DJ, Van der Ploeg LH, Guan XM. Distribution of orexin receptor mRNA in the rat brain. FEBS Lett. 1998;438:71–75. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01266-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vanni-Mercier G, Sakai K, Jouvet M. Neurones specifiques de l'eveil dans l'hypothalamus posterieur. C R Acad Sci III. 1984;298:195–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.von Economo C. Sleep as a problem of localization. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1930;71:249–259. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Waite JJ, Wardlow ML, Chen AC, Lappi DA, Wiley RG, Thal LJ. Time course of cholinergic and monoaminergic changes in rat brain after immunolesioning with 192 IgG-saporin. Neurosci Lett. 1994;169:154–158. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90379-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Watts AG, Swanson LW, Sanchez-Watts G. Efferent projections of the suprachiasmatic nucleus. I. Studies using anterograde transport of Phaseolus vulgaris leucoagglutinin in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1987;258:204–229. doi: 10.1002/cne.902580204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wiley RG, Lappi DA. Destruction of neurokinin-1 receptor expressing cells in vitro and in vivo using substance P-saporin. Neurosci Lett. 1997;230:97–100. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00490-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wu MF, Gulyani SA, Yau E, Mignot E, Phan B, Siegel JM. Locus coeruleus neurons: cessation of activity during cataplexy. Neuroscience. 1999;91:1389–1399. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00600-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yanai K, Zhao XL, Watanabe T. Excitotoxic lesions of histaminergic neurons by excitatory amino acid agonists in the rat brain. Neurosci Lett. 1997;232:159–162. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00609-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]