Abstract

Anatomical evidence indicates that medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) neurons project to the dorsal raphe nucleus (DR). In this study, we functionally characterized this descending pathway in rat brain. Projection neurons in the mPFC were identified by antidromic stimulation from the DR. Electrical stimulation of the mPFC mainly inhibited the activity of DR 5-HT neurons (55 of 66). Peristimulus time histograms showed a silence of 150 ± 9 msec poststimulus (latency, 36 ± 1 msec). The administration of WAY-100635 and picrotoxinin partly reversed this inhibition, indicating the involvement of 5-HT1A and GABAA receptors. In rats depleted of 5-HT with p-chlorophenylalanine, the electrical stimulation of mPFC mainly activated 5-HT neurons (31 of 40). The excitations (latency, 17 ± 1 msec) were antagonized by MK-801 and NBQX. Likewise, MK-801 prevented the rise in DR 5-HT release induced by electrical stimulation of mPFC. The application of 8-OH-DPAT in mPFC significantly inhibited the firing rate of DR 5-HT neurons and, in dual-probe microdialysis experiments, reduced the 5-HT output in mPFC and DR. Furthermore, the application of WAY-100635 in mPFC significantly antagonized the reduction of 5-HT release produced by systemic 8-OH-DPAT administration in both areas. These results indicate the existence of a complex regulation of DR 5-HT neurons by mPFC afferents. The stimulus-induced excitation of some 5-HT neurons by descending excitatory fibers releases 5-HT, which inhibits the same or other DR neurons by acting on 5-HT1A autoreceptors. Afferents from the mPFC also inhibit 5-HT neurons through the activation of GABAergic interneurons. Ascending serotonergic pathways may control the activity of this descending pathway by acting on postsynaptic 5-HT1A receptors.

Keywords: 5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT1A receptors, 5-HT release, AMPA/KA receptors, dorsal raphe nucleus, GABA receptors, NMDA receptors, medial prefrontal cortex

Serotonergic [5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT)] neurons participate in many physiological functions and are the cellular target of drugs used to treat psychiatric illnesses (Aghajanian et al., 1987; Jacobs and Azmitia, 1992; Montgomery, 1994;Meltzer, 1999). Their activity is controlled by 5-HT1A autoreceptors in the raphe nuclei (Blier and de Montigny, 1987; Sprouse and Aghajanian, 1987). Also, afferents to the dorsal raphe nucleus (DR) originate in various brain areas. These include the catecholamine groups (Baraban and Aghajanian, 1980;Peyron et al., 1995, 1996), the lateral habenula (Aghajanian and Wang, 1977; Stern et al., 1981; Kalén and Wiklund, 1989), the hypothalamus (Peyron et al., 1998), the substantia nigra (Stern et al., 1981), and the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) (Aghajanian and Wang, 1977; Sesack et al., 1989; Takagishi and Chiba, 1991; Hajós et al., 1998; Peyron et al., 1998).

Pyramidal neurons of the mPFC integrate cortical and thalamic inputs and project mainly to subcortical areas, including, among others, the mediodorsal nucleus of the thalamus, the amygdaloid complex, the lateral habenula, hypothalamic areas, and the brainstem aminergic nuclei (Aghajanian and Wang, 1977; Thierry et al., 1983; Sesack et al., 1989; Sesack and Pickel, 1992; Murase et al., 1993; Hajós et al., 1998; Peyron et al., 1998). In turn, the mPFC is densely innervated by aminergic fibers from the latter nuclei. In particular, it receives serotonergic afferents from the raphe nuclei (Azmitia and Segal, 1978) and contains a large density of various 5-HT receptors (see below). Given its unique cytoarchitecture and connectivity, the prefrontal cortex regulates a large number of cognitive and associative functions and is involved in the planning and execution of complex tasks (Fuster, 1997). Severe mental illnesses have been associated with an abnormal prefrontal function (Andreasen et al., 1997; Drevets et al., 1997). Given the involvement of 5-HT in psychiatric diseases such as anxiety, depression, and schizophrenia, the relationships between the mPFC and 5-HT neurons are of particular importance to understand the pathophysiology and treatment of these diseases.

Layer V pyramidal neurons in mPFC are enriched in 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptors (Pazos and Palacios, 1985; Pompeiano et al., 1992, 1994; Kia et al., 1996) with opposed effects on neuronal excitability (Araneda and Andrade, 1991). The activation of pyramidal 5-HT2A receptors triggers an increase in EPSCs, resulting from an enhanced glutamate release and subsequent activation of AMPA–KA receptors (Aghajanian and Marek, 2000). Likewise, the local activation of 5-HT2A and 5-HT1A receptors increases and decreases, respectively, the 5-HT release in mPFC (Casanovas et al., 1999;Martín-Ruiz et al., 2001). Because of the existence of descending projections from the mPFC to the DR, postsynaptic 5-HT receptors in mPFC could exert a distal feedback via descending inputs. Indeed, there is circumstantial evidence supporting that postsynaptic 5-HT1A receptors participate in the control of serotonergic activity (Blier and de Montigny, 1987; Ceci et al., 1994;Romero et al., 1994; Hajós et al., 1999). In the present study we examine the control of the activity of DR 5-HT neurons by the mPFC and the transmitters and receptors involved in this control.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Male Wistar rats weighing 260–320 gm (Iffa Credo, Lyon, France) were used. Animal care followed the European Union regulations (EEC Council Directives of 24/11/1986; 86/609/EEC). They were kept in a controlled environment (12 hr light/dark cycle and 22 ± 2°C room temperature). Food and water were provided ad libitumbefore and during microdialysis experiments, which usually began between 9:00 and 10:00 A.M. The stereotaxic coordinates (in millimeters) were taken from the atlas of Paxinos and Watson (1986) using bregma and dura mater as references.

Chemicals

5-HT oxalate, 8-hydroxy-2-(di-n-propylamino)tetralin (8-OH-DPAT), (+)MK-801 (dizolcipine), 2,3-dihydroxy-6-nitro-7-sulfamoyl-benzo(f) quinoxaline (NBQX), picrotoxininin, andN-(2-(4-(2-methoxyphenyl)-1-piperazinyl)ethyl)-N-(2-pyridyl) cyclohexanecarboxamide · 3HCl (WAY-100635) were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) and Research Biochemicals (Natick, MA). Citalopram · HBr was from Lundbeck A/S. Other materials and reagents were from local commercial sources.

Single-unit extracellular recordings

These were performed as previously described (Sawyer et al., 1985; Celada et al., 1996). For recording experiments, rats were anesthetized with chloral hydrate (400 mg/kg, i.p.). The femoral vein was cannulated for the administration of drugs, and additional anesthetic (chloral hydrate, 80 mg/kg) was regularly given to maintain anesthesia. Rats were placed in a David Kopf (Tujinga, CA) stereotaxic frame. All wound margins and points of contact between the animal and the stereotaxic apparatus were infiltrated with lidocaine solution (5%). Body temperature was maintained at 37 ± 1°C with a heating pad. The atlanto-occipital membrane was punctured to allow some drainage of the CSF. After scalp removal, two small burr holes were drilled over the mPFC [anteroposterior (AP) +3.4 from bregma, lateral (L) ±0.5] for the insertion of stimulating electrodes. A 4 × 4 mm recording hole was drilled over lambda, and the saggital sinus was ligated, cut, and reflected. Bipolar stimulating electrodes consisted of two stainless steel enamel-coated wires (California Fine Wire, Grover Beach, CA) with a diameter of 150 μm and a tip separation of ∼100 μm and in vitro impedances of 10–30 KΩ. Electrodes were lowered to 5 mm below the cortical surface and cemented in place with cyanoacrylate glue and dental cement. For the antidromic identification of pyramidal neurons projecting to the DR, a recording hole was drilled over the mPFC, and the stimulating electrode was implanted in the DR [AP −7.8 from bregma, L −3.1, dorsoventral (DV) −6.8, with an angle of 30°]. The antidromic nature of DR-evoked responses was determined by collision extinction with spontaneously occurring spikes (Fuller and Schlag, 1976). Recording electrodes were made from 2.0 mm outer diameter (o.d.) capillary glass (WPI, Saratosa, FL) pulled on a Narishige (Tokyo, Japan) PE-2 pipette puller and filled with 2 mNaCl. The electrode impedance was lowered to 4–10 MΩ by passing 500 msec 150 V DC pulses (Grass stimulation model S-48) through the electrode.

Constant current electrical stimuli were generated with a Grass stimulation unit S-48 connected to a Grass SIU 5 stimulus isolation unit. mPFC neurons were stimulated with monophasic square wave pulses (0.2 msec, 0.9 Hz, 0.5–2.5 mA). Single-unit extracellular recordings were amplified with a Neurodata IR283 (Cygnus Technology, Delaware Water Gap, PA), postamplified, and filtered with a Cibertec (Madrid, Spain) amplifier, and computed on-line using a DAT 1401plus interface system Spike2 software (Cambridge Electronic Design, Cambridge, UK). Data were also recorded on magnetic audiotape for off-line recording if necessary. Descents were performed along the midline. 5-HT neurons were usually encountered 4.8–6.5 mm below the brain surface and identified according to previously described electrophysiological criteria (Wang and Aghajanian, 1977). Serotonergic neurons exhibited a regular firing rate with frequencies of 0.4–3.5 Hz, and 2–5 msec biphasic or triphasic extracellular waveforms and were inhibited by the 5-HT1A agonist 8-OH-DPAT.

Surgery and microdialysis procedures

Microdialysis procedures in unanesthetized rats were performed essentially as described in Adell and Artigas (1991). Anesthetized rats (pentobarbitone, 60 mg/kg, i.p.) were placed in a stereotaxic apparatus and implanted with microdialysis probes. Dual probe microdialysis was performed by implanting two I-shaped probes in the mPFC (AP +3.4, L −0.8, DV −6.0) and the DR (AP −7.8, L −3.1, DV −7.5). Probes in the DR were implanted with an angle of 30° to avoid obstruction of the cerebral aqueduct. The length of membrane exposed to the brain tissue was 4 mm long (o.d. 0.25 mm) in mPFC and 1.5 mm long in DR. One group of rats was implanted with 4 mm probes in the lateral prefrontal cortex (AP +3.4, L −3.0, DV −6.0) and DR (as above) to control for the effects in DR of the local application of 8-OH-DPAT in mPFC.

Animals were allowed to recover from surgery for ∼20 hr, and then probes were perfused with artificial CSF (aCSF) (in mm: 125NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.26 CaCl2, and 1.18 MgCl2) containing 1 μm citalopram at 0.25 μl/min. Sample collection started 60 min after the beginning of perfusion. Dialysate samples were collected every 20 min (5 μl). Usually five or six fractions were collected before drug administration, of which four were used to obtain the individual basal values. Two different microdialysis experiments were conducted in unanesthetized rats. In the first one, groups of rats were administered with two sequential injections of 8-OH-DPAT (0.1 + 0.1 mg/kg, s.c.) 3 hr apart. Animals of the control group received the two injections in identical conditions, and the effects of 8-OH-DPAT on 5-HT release were examined in the DR and mPFC (rats had dual implants). Two other groups of rats received the first 8-OH-DPAT injection in control conditions, and the second one was administered while the 5-HT1A receptor antagonist WAY-100635 (100 μm) was perfused into the DR or the mPFC (perfusions began 40 min before the second 8-OH-DPAT injection) to examine the role of presynaptic and postsynaptic 5-HT1A receptors in the control of 5-HT release in both areas. The ratios between the inhibitions of the second and first injection on 5-HT release were calculated and compared in both groups (i.e., with and without WAY-100635 in the DR or mPFC).

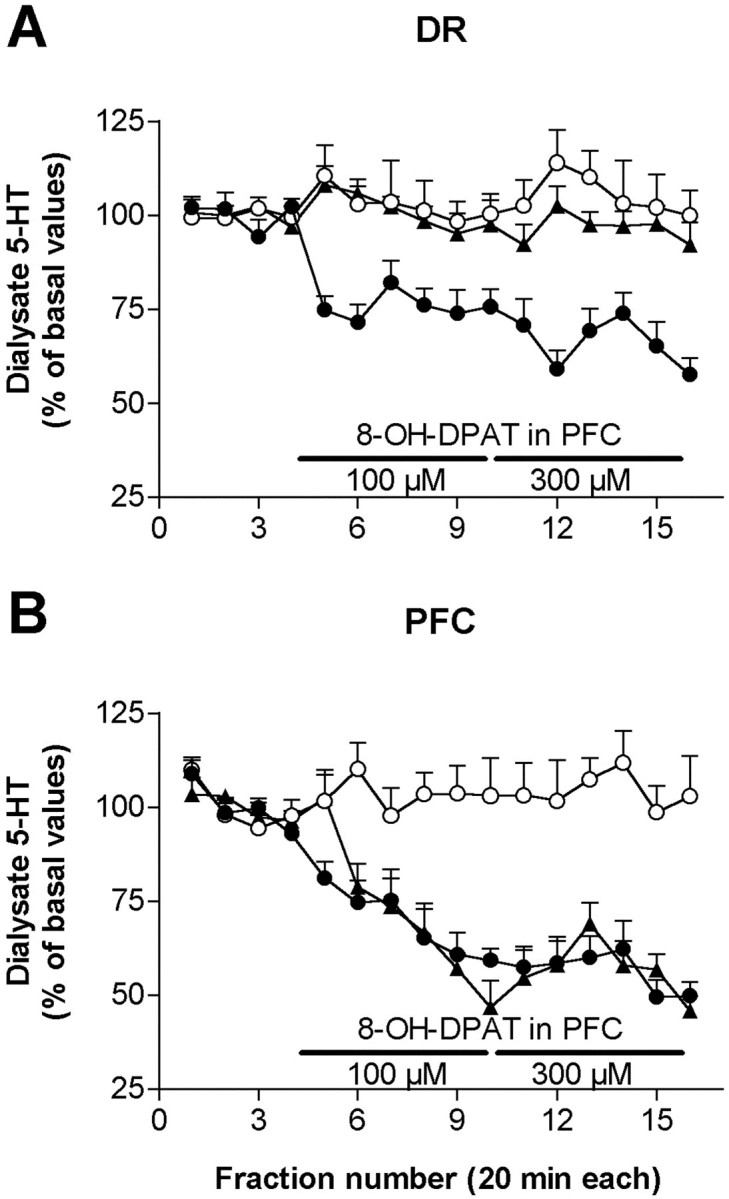

In another experiment, 8-OH-DPAT (100 and 300 μm; 120 min each) was perfused through the probe in mPFC, and 5-HT was analyzed in dialysates from the mPFC and DR of the same animals (dual implants). The total amount of 8-OH-DPAT perfused through the dialysis probes at the two concentrations used was 3 and 9 nmol over the course of 2 hr (uncorrected for probe recovery). Two groups of controls were used, one receiving aCSF in both sites for the entire collection period (sham changes of perfusion syringes were also performed in this group) and another one in which the prefrontal probes were placed more laterally, in an area devoid of neurons projecting to the DR (Peyron et al., 1998; see above coordinates).

Electrical stimulation and microdialysis in anesthetized rats

We examined the effect of the electrical stimulation of the mPFC on the 5-HT release in the DR. Microdialysis probes were implanted the day before, as above. After chloral hydrate anesthesia, rats were placed in the stereotaxic frame, and stimulating electrodes were placed in the mPFC. In a first experiment, the effects of three different stimulation conditions (S1–S3) were examined: S1, 0.9 Hz, 1.7 mA, 0.2 msec; S2, 10 Hz, 0.5 mA, 1 msec; S3, 20 Hz, 0.5 mA, 1 msec. A second experiment assessed the effects of S4 (0.9 Hz, 2 mA, 0.2 msec) and S3. Both S1 and S4 mimicked the stimulation conditions at which peristimulus time histograms (PSTHs) were obtained, whereas S2 and S3 were chosen to examine the effects of higher frequency stimulation (10–20 Hz) at a lower intensity (0.5 mA). Dialysate fractions were collected every 10 min. In these experiments, perfusion rate was 1.5 μl/min to facilitate the handling of the dialysate samples. Probes were perfused with aCSF containing 1 μmcitalopram as above. Usually 10 fractions were collected before electrical stimulation.

Chromatographic analysis

5-HT was determined using a modification of an HPLC method previously described (Adell and Artigas, 1998). The composition of the chromatographic eluant was as follows: 0.15 mNaH2PO4, 1.3 mmoctyl sodium sulfate, and 0.2 mm EDTA, pH 2.8 adjusted with phosphoric acid, plus 27% methanol. 5-HT was separated on a 3 μm ODS 2 column (7.5 cm × 0.46 cm; Beckman, San Ramón, CA) and detected amperometrically with a Hewlett Packard 1049 detector (oxidation potential, +0.6 V). Retention time was 3.5–4 min. The absolute detection limit for 5-HT was typically 1 fmol/sample. Dialysate 5-HT values were calculated by reference to standard curves run daily.

Drug administration

Local administration. In electrophysiological experiments, drugs (dissolved in aCSF) were infused through a 32 gm stainless steel cannula (Small Parts Inc., Miami, FL) implanted in the mPFC (same coordinate as stimulating electrodes). The cannula was attached to a 10 μl Hamilton syringe by a Teflon tubing. A microinfusion pump (Bioanalytical Systems Inc., West Lafayette, IN) was used. After recording baseline spontaneous activity, 200 nl of the 5-HT1A agonist 8-OH DPAT (100 μm; Research Biochemicals) was infused over the course of 1 min. This volume has been reported to diffuse to a maximum effective diameter of 0.4–0.6 mm (Myers, 1971).

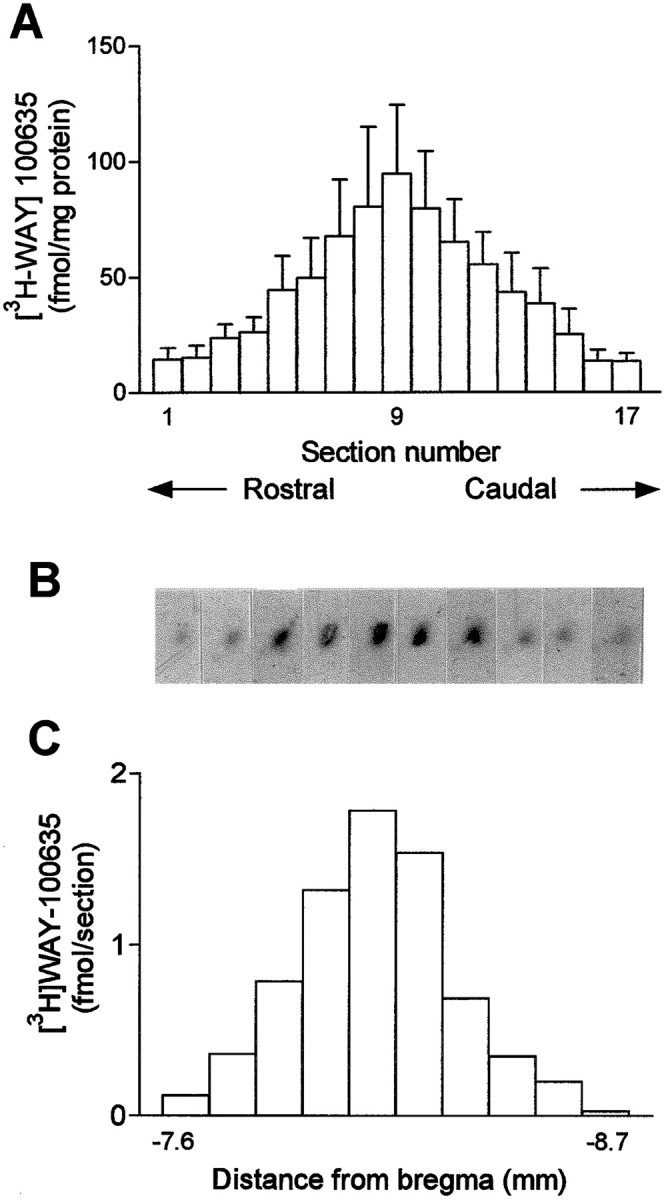

In dialysis experiments the local application of 8-OH-DPAT (100 and 300 μm) and WAY-100635 (100 μm) dissolved in aCSF was made by reverse dialysis through the probe. We examined the extent of the diffusion of WAY-100635 in the DR after its local application by using [3H]WAY-100635 (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Little Chalfont, UK), as described (Romero and Artigas, 1997). We used the DR to examine drug diffusion because of the concentration of 5-HT1A receptors in a small brain area. Four rats were implanted with 1.5-mm-long probes in the DR, which were perfused at 0.25 μl/min with aCSF containing 100 μm WAY-100635, plus 100 nm of the radioactive tracer. The in vitro recovery of the dialysis probes (1.5 mm) for WAY-100635 was 58.7 ± 4.6% (as measured by the amount of tritium label of the tracer). After an infusion period of 80 min, the rats were decapitated, and the brains were removed and frozen. Coronal midbrain sections (14-μm-thick) were cut to examine the labeling of 5-HT1A receptors in the DR by [3H] WAY-100635 (Gozlan et al., 1995;Khawaja et al., 1995). Given the rostrocaudal distribution of the various neuronal groups composing the DR, coronal sections were cut at different anteroposterior levels (approximately from −6.5 to −9.0 mm relative to bregma). Additional sections were cut in some rats at hippocampal and cortical levels. The sections were exposed to a tritium-sensitive film (Hyperfilm 3H; Amersham) for 3 weeks. The optical density of the tritium labeling in films was measured using an image analysis system (Imaging Research Inc., St. Catharines, Ontario, Canada). The surface of areas showing a dense labeling by [3H]WAY-100635 was quantified to calculate the total amount of tritium label in each section and the density of ligand binding.

Systemic administration. The 5-HT synthesis inhibitorp-clorophenylalanine (pCPA) was dissolved in saline and administered (350 mg/kg, i.p.) 48 and 24 hr before the recordings. At the end of the experiments, a portion of the frontoparietal cortex was dissected out, weighed, and frozen at −80°C for subsequent analysis of 5-HT.

In some electrophysiological experiments, once a stable response to mPFC stimulation was obtained, we administered intravenously the selective 5-HT1A receptor antagonist WAY-100635 (5–10 μg/kg, i.v.), the GABAA receptor antagonist picrotoxinin (1–2 mg/kg, i.v.; Sigma), the NMDA receptor antagonist (+)MK-801 (0.66–0.99 mg/kg, i.v.; RBI); or the AMPA–kainate glutamate antagonist NBQX (1–2 mg/kg, i.v.; Tocris Cookson, Bristol, UK) to examine their effects on the response of DR 5-HT neurons to the mPFC stimulation. Typically, drug effects were measured starting 1.5–4 min after administration. In microdialysis experiments, 8-OH-DPAT was administered subcutaneously at 0.1 mg/kg.

Histology

At the end of the experiments, rats were killed by an overdose of anesthetic. Rats used in electrophysiology experiments were perfused transcardially with saline followed by 10% formalin solution (Sigma). Brains were post-fixed, sectioned (70 μm), and stained with Neutral Red for histological verification of stimulating and infusion cannula sites. In microdialysis experiments the placement of the dialysis probes was checked by perfusing Fast Green dye and visual inspection of the probe track after cutting the brain at the appropriate levels.

Data treatment and statistical analyses

Responses in 5-HT neurons evoked by mPFC stimulation were characterized by measuring the magnitude and duration of inhibitory and excitatory responses from PSTHs following essentially the criteria described by Hajós et al. (1998). The following responses were identified: (1) antidromic activation: antidromic spikes following a constant latency. The antidromic nature of this excitation was determined by collision extinction with spontaneously occurring spikes (Fuller and Schlag, 1976). (2) Orthodromic activation: orthodromic excitations elicited spikes with short and variable latencies. In orthodromically activated neurons, the cortical stimulation evoked orthodromic spikes with a success rate higher than 10%. Milder activations (5–10%) were also observed in a substantial number of neurons, mostly followed by inhibitory responses. (3) Inhibitions: The onset of the inhibition was defined by either a total cessation of spikes for at least four successive bins (10 msec width) or a 75% decrease in the number of spikes with respect to the prestimulus value. The offset of the inhibition was defined as the first of four bins equal to or above the prestimulus value.

The changes in firing rate after 8-OH-DPAT administration in mPFC were quantified by analyzing a 2 min epoch centered around the maximal changes produced by drug infusion and comparing them to a similar 2 min epoch before the onset of drug infusion in mPFC. The effects of drugs were assessed using one-way repeated measures ANOVA and paired Student's t test.

Microdialysis results were expressed as femtomoles per fraction and represented in the figures as percentages of baseline. ANOVA for repeated measures of raw data were used to assess the effects of drug administration or electrical stimulation on 5-HT release. In the experiments involving two sequential injections of 8-OH-DPAT, we computed the individual ratios between the value of 5-HT in the two fractions (7 and 16) at which the effect of 8-OH-DPAT was maximal (peak ratios). These values were used to examine the effects of the application of WAY-100635 (in DR or mPFC) on the effects of the second 8-OH-DPAT injection.

Statistical significance has been set at the 95% confidence level (two-tailed). Unless otherwise specified, all values are expressed as the mean ± SEM.

RESULTS

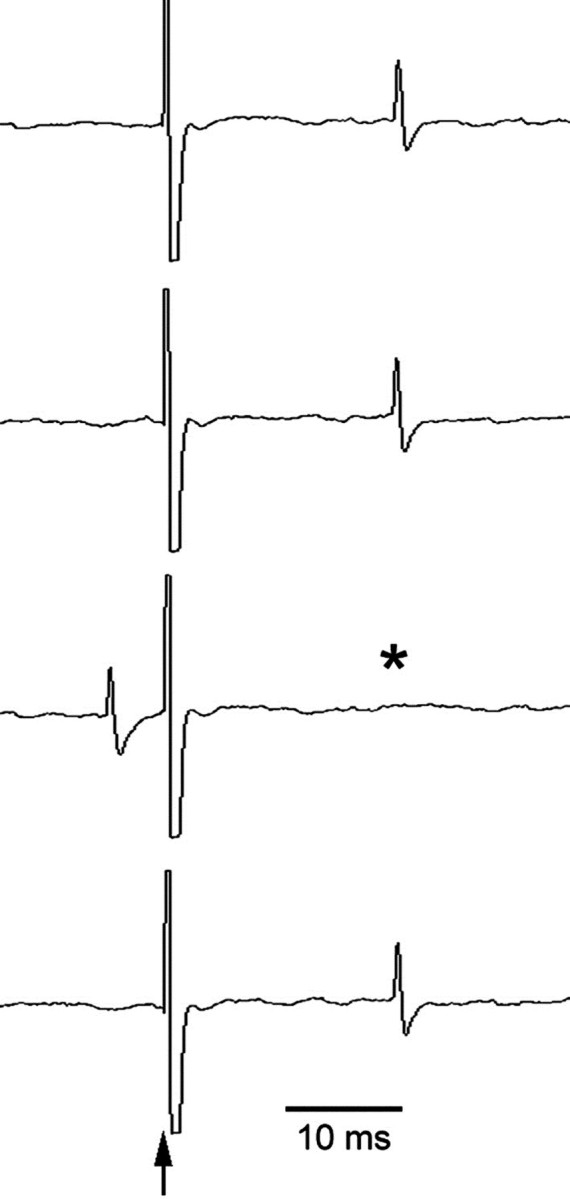

Identification of mPFC neurons projecting to the DR

In an initial experiment, we identified by antidromic activation pyramidal mPFC neurons projecting to the DR (mPFC recordings were performed at the same coordinate used for stimulation experiments; see below) (Fig. 1). Seventeen neurons were antidromically activated from the DR with a latency 17.6 ± 1.6 msec. Considering an average linear distance of 11.1 mm between the stimulation and recording sites, the conduction velocity (distance/latency) was 0.63 m/sec, in the range of reported values for mPFC efferent fibers (Thierry et al., 1983).

Fig. 1.

Extracellular recording of a representative mPFC neuron projecting to the DR. Electrical stimulation of the DR (arrow) evoked antidromic responses in mPFC neurons. Theasterisk denotes an antidromic spike missing because of collision with an spontaneous action potential.

Effect of mPFC stimulation on DR 5-HT neurons

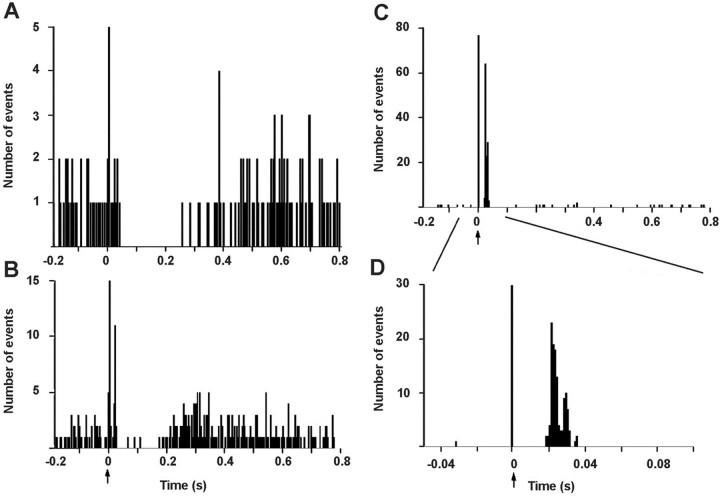

The effect of the electrical stimulation of the mPFC was studied on 106 5-HT neurons in the DR responding to the stimulation (Table1). Two main types of responses were recorded: inhibition and orthodromic activation. Neurons that were antidromically activated were not considered. The majority of the recorded 5-HT neurons in control rats (55 of 66; 83%) responded to mPFC stimulation (currents ranging from 0.5 to 2.5 mA) with a short-latency poststimulus inhibition (Fig.2A). Of these, 18 showed a concurrent short-latency subthreshold (5–10%) orthodromic activation (Fig. 2B). Eleven (of 66) neurons (17%) responded to mPFC stimulation with a short-latency orthodromic activation (>10%) (Fig. 2C,D). The success rate of orthodromic activation varied between neurons and was 24.7 ± 7.7% on average (n = 11).

Table 1.

Summary of the basal firing rate and responses of 5-HT neurons to electrical stimulation (0.5–2.5 mA) of the mPFC

| Control | pCPA | |

|---|---|---|

| Inhibition | 55 | 9 |

| Firing rate (spikes/sec) | 1.24 ± 0.10 | 0.9 ± 0.3 |

| Delay (msec) | 36 ± 1 | 37 ± 3 |

| Duration (msec) | 150 ± 9 | 118 ± 19 |

| Orthodromic activation | 11 | 31 |

| Firing rate (spikes/sec) | 1.16 ± 0.19 | 0.73 ± 0.12 |

| Delay (msec) | 16.6 ± 1.4 | 18.9 ± 0.68 |

| Duration (msec) | 17.3 ± 2.0 | 20.1 ± 1.8 |

| Success rate (%) | 24.7 ± 7.7 | 29.4 ± 3.8 |

| Total | 66 | 40 |

| Firing (spikes/sec) | 1.23 ± 0.09 | 0.77 ± 0.11* |

5-HT neurons were recorded in the DR of control andpCPA (2× 350 mg/kg, i.p.) pretreated rats. Success rate was defined as the ratio between the number of orthodromic spikes elicited by mPFC stimulation and the number of triggers. Data are means ± SEM.

p < 0.05 versus controls.

Fig. 2.

Typical examples of responses of DR neurons to the electrical stimulation of the mPFC. A shows a PSTH corresponding to an inhibition of a 5-HT neuron. B shows a PSTH in which a subthreshold activation (9%) occurred before inhibition. C and D show an orthodromic activation of a 5-HT neuron (note the different time scale and bin size in D). The arrow indicates the stimulus artifact. PSTH made up of 250 consecutive trials of single pulse stimuli (0.2 msec, 1 mA) delivered at 0.9 Hz. Bin width 4 msec (A–C) and 1 msec (D). Note the different ordinate scale in A and Bversus C and D.

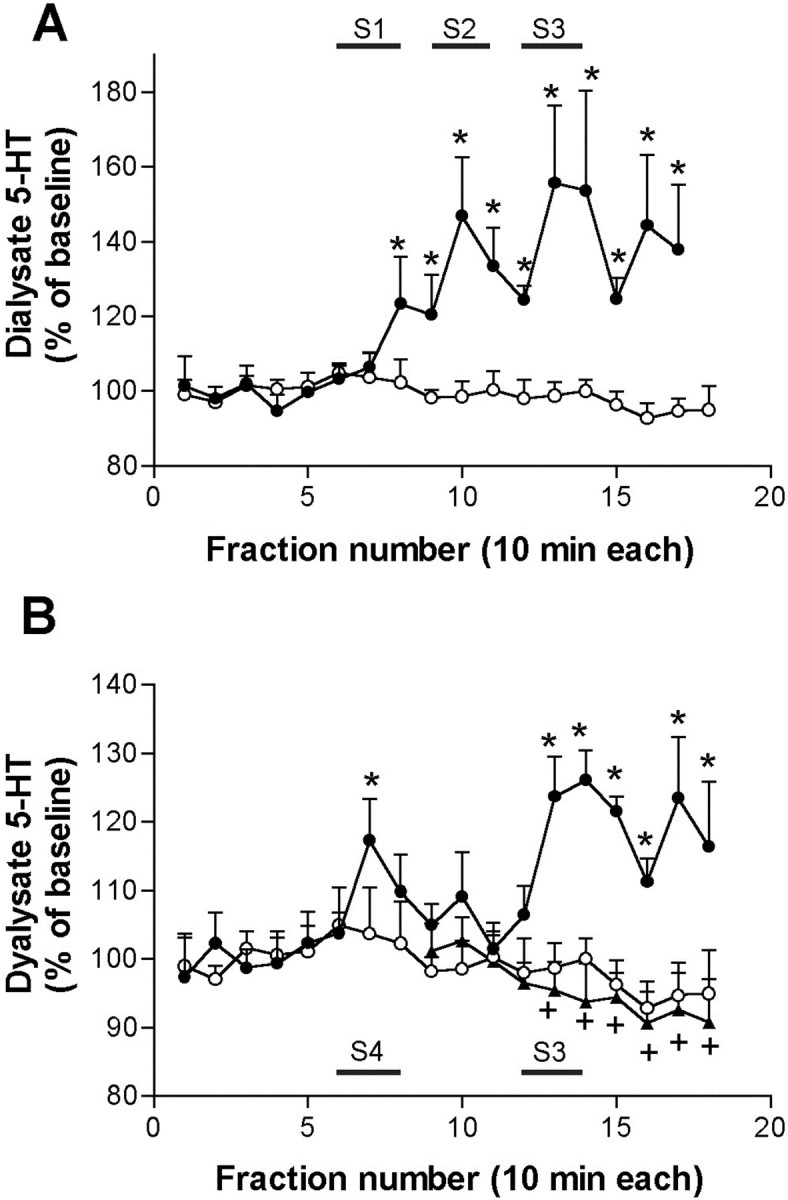

We assessed the effects of the electrical stimulation of the mPFC on the 5-HT release in the DR of chloral hydrate-anesthetized rats (Fig.3). Control rats were implanted with electrodes in the mPFC but received no stimulation. Dialysate fractions were collected every 10 min. Two different experiments were performed. In the first (pilot) experiment, electrical stimulation was delivered in three different conditions (S1-S3; see legend to Fig.3) for two fractions (20 min total), separated from each other by 10 min. The electrical stimulation of the mPFC enhanced 5-HT release in the DR, to a maximum of 156 ± 21% of baseline at the third stimulation (Fig. 3A). Two-way ANOVA analysis revealed a significant effect of the time (p < 0.00001) and of the time × group interaction (p < 0.00001) versus controls. In a second experiment, a first stimulation period was delivered for 20 min (S4, 0.9 Hz, 0.2 msec, 2 mA) followed by a second stimulation (S3, 20 Hz, 1 msec, 0.5 mA) for 20 min delivered 40 min later. As in the first experiment, the electrical stimulation of the mPFC increased the 5-HT release in the DR compared with sham-stimulated rats (Fig. 3B). Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of the time (p < 0.02) and of the time × group interaction (p < 0.0005). Interestingly, the stimulation of the mPFC using S4 stimulation conditions produced a transient elevation of the 5-HT release in the DR, whereas the stimulation at a higher frequency (20 Hz) and lower intensity (0.5 mA) (S3 conditions) resulted in an increase in 5-HT that persisted 40 min after the end of the stimulation period (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Effects of electrical stimulation of the mPFC on the 5-HT release in the DR. A, Three different stimulation conditions (S1, 0.9 Hz, 1,7 mA, 0.2 msec; S2, 10 Hz, 0.5 mA, 1 msec; S3, 20 Hz, 0.5 mA, 1 msec; shown by horizontal bars) increased the 5-HT release in the DR (filled circles; n = 4). Control rats (open circles; n = 6) were implanted with electrodes, but no current was passed.B, The electrical stimulation of mPFC using the same conditions than in PSTH experiments (S4, 0.9 Hz, 2 mA, 0.2 msec;first bar) produced a transient elevation of the 5-HT release in DR (see also the effect of S1 in A), whereas the stimulation at S3 conditions (20 Hz, 0.5 mA, 1 msec) produced a sustained increase in 5-HT release for at least 60 min (filled circles; n = 7). Control rats (open circles; n = 6) were implanted with electrodes, but no current was passed. The local application of MK-801 (300 μm; filled triangles;n = 7) by reverse dialysis prevented the increase in 5-HT release induced by the second stimulation conditions. *p < 0.05 versus controls;+p < 0.05 versus stimulation (no MK-801)

Role of 5-HT1A autoreceptors on the mPFC-induced inhibitions

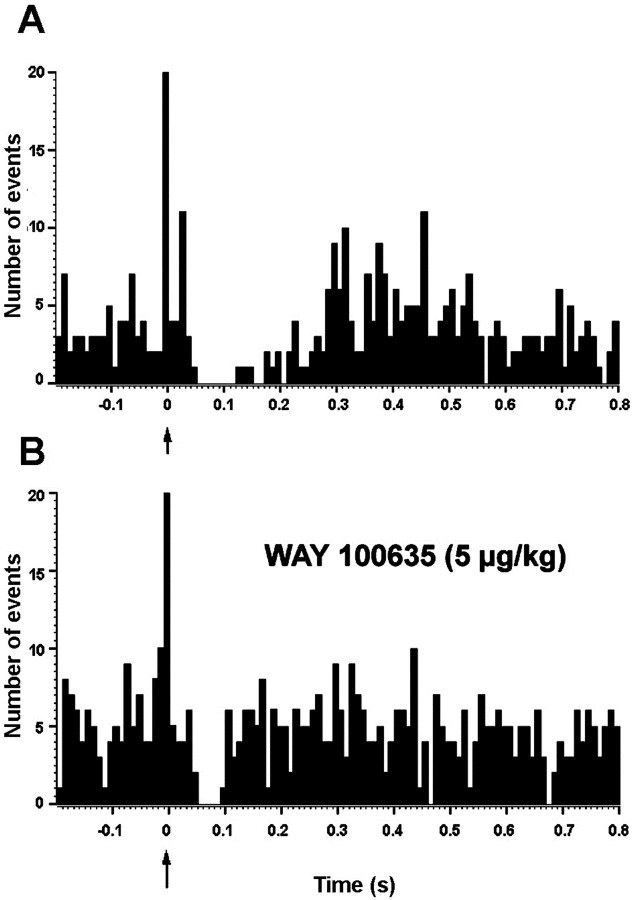

The above results suggested that the stimulation of mPFC excited a proportion of DR 5-HT neurons. These could release 5-HT which, by acting on local 5-HT1A receptors, would inhibit the same or other 5-HT neurons in the DR. To examine this possibility we used two different experimental approaches. In the first one, rats were administered the selective 5-HT1A receptor antagonist WAY-100635 once a basal PSTH was recorded (typically, 250 sweeps). The administration of WAY-100635 (5–10 μg/kg, i.v.) significantly reduced the percentage of basal inhibition (13 ± 2 to 65 ± 10% of prestimulus firing rate; p< 0.001; paired t test; n = 11) and its duration (from 188 ± 19 to 124 ± 16 msec; p< 0.002; paired t test; n = 11) without significantly altering the firing rate. Figure4 shows two PSTHs of a 5-HT neuron in the DR, before (A) and after (B) the administration of WAY-100635 (5 μg/kg, i.v.).

Fig. 4.

Effect of the systemic administration of the 5-HT1A receptor antagonist WAY-100635 on the poststimulus inhibition of a DR 5-HT neuron in response to stimulation of the mPFC.A, DR serotonergic neuron inhibited by mPFC stimulation (arrow) (suppression of 230 msec to 30% of prestimulus firing rate). B, WAY-100635 (5 μg/kg, i.v.) partially blocks the inhibition (to 50 msec, 77% prestimulus firing rate). Bin size: 10 msec, 250 sweeps.

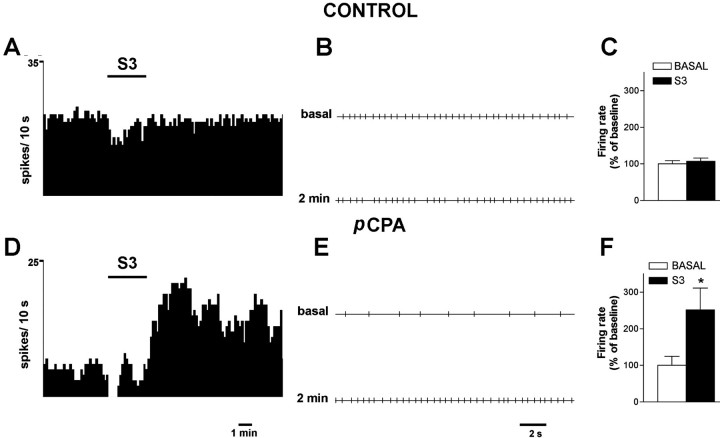

The contribution of 5-HT released in the DR after mPFC stimulation to the observed inhibitions was studied by pretreating the rats with the 5-HT synthesis inhibitor pCPA. In 5-HT-depleted rats (pCPA; 2 × 350 mg/kg, i.p.; 48 and 24 hr before experiments), the concentration of 5-HT in frontoparietal cortex was around 10% of that in control rats (30 ± 3 pmol/gm;n = 19 vs 288 ± 37 pmol/gm; n = 7; p < 0.0001; Student's t test). InpCPA-pretreated rats, the electrical stimulation of the mPFC resulted in a significantly higher proportion of orthodromic activations compared with control rats [77 (31 of 40) versus 17% (11 of 66) in control rats; p < 0.01; χ2 test] (Table 1). Nine neurons were equally inhibited by mPFC stimulation in pCPA-pretreated rats. The lower firing rate in pCPA-treated rats (Table 1) perhaps results from a reduction of noradrenergic synthesis (Reader et al., 1986) and reduced activation of α1-adrenoceptors controlling 5-HT activity (Baraban and Aghajanian, 1980).

The electrical stimulation of the mPFC (20 Hz, 1 msec, 0.5 mA) did not change the firing rate of 5-HT neurons in control rats (baseline, 1.50 ± 0.14 Hz; post-stimulation, 1.55 ± 0.14 Hz;n = 11; measured 4 min after the end of the stimulation period). However, it increased that in pCPA-treated rats, from 0.64 ± 0.16 Hz (baseline) to 1.18 ± 0.18 Hz (post-stimulation; also measured 4 min after the end of the stimulation period) (p < 0.02; pairedt test; n = 7) (Fig.5).

Fig. 5.

Effect of mPFC stimulation (S3, 20 Hz, 1 msec, 0.5 mA, for 3 min; shown by a horizontal bar) on the spontaneous firing of 5-HT neurons. A andD show integrated firing rate histograms of two representative neurons in control (A) andpCPA-treated (D) rats.B and E show the corresponding spike trains of the same neurons before and 2 min after S3 stimulation. During the second minute of the stimulation, the firing rate of 5-HT neurons in pCPA-treated rats was already significantly increased versus basal (1.1 ± 0.2 vs 0.6 ± 0.2 spikes/sec;p < 0.02). However, the maximal effect of the stimulation was noted later. C and F are bar graphs with the mean ± SEM values of firing rate before and after (4th minute) S3 stimulation (n = 12 controls and 7 pCPA-treated rats). *p < 0.02 versus baseline.

Involvement of GABAA receptors in the mPFC-triggered inhibition of DR 5-HT neurons

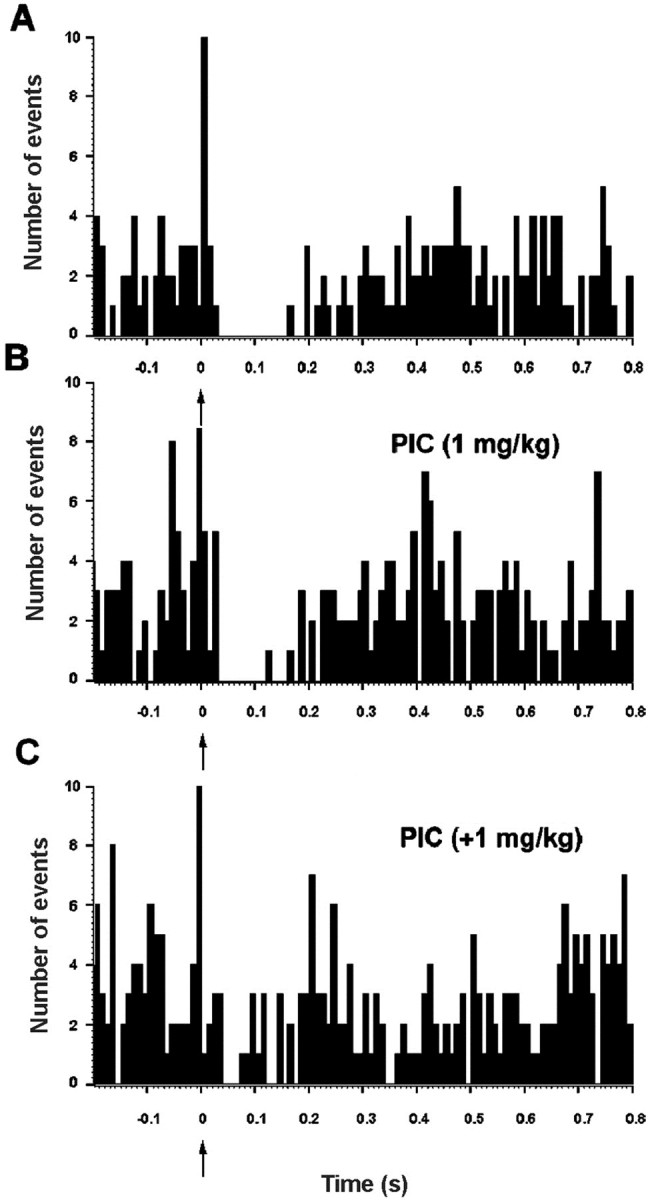

Because neither 5-HT depletion nor 5-HT1Areceptor blockade totally reversed the mPFC-induced inhibition of 5-HT neurons, we assessed the involvement of GABAAreceptors. The intravenous administration of picrotoxinin (1–2 mg/kg, i.v.) partially blocked the inhibitory responses to mPFC stimulation as shown in Figure 6. Under basal conditions mPFC stimulation depressed firing rate to 11 ± 3% of prestimulus baseline levels. The administration of picrotoxinin (1 mg/kg, i.v.) resulted in a significant reduction of the inhibition to 32 ± 7% of prestimulus firing rate (p < 0.005; pairedt test; n = 8). Likewise, the administration of picrotoxinin significantly reduced the duration of the mPFC-triggered inhibition (from 151 ± 31 msec in baseline conditions to 124 ± 26 msec; p < 0.02; pairedt test; n = 8) without altering the firing rate of the recorded neurons. The administration of an additional dose of picrotoxinin (1 + 1 mg/kg, i.v.) further decreased the inhibition to 49 ± 8% of prestimulus firing rate (paired t test;p < 0.05; n = 5). The treatment with this additional dose of picrotoxinin significantly increased the firing rate from 0.9 ± 0.3 to 1.8 ± 0.2 spikes/sec (p < 0.002; paired t test;n = 5).

Fig. 6.

Effect of the GABAA receptor antagonist picrotoxinin on the poststimulus inhibition of a DR 5-HT neuron in response to mPFC stimulation. A, PSTH of a DR 5-HT neuron inhibited by mPFC stimulation (arrow) (suppression of 260 msec to 24% of prestimulus firing rate).B, Picrotoxinin (1 mg/kg, i.v.) partially blocked the mPFC-induced inhibition. C, An additional intravenous picrotoxinin dose of 1 mg/kg further reduced the mPFC-induced inhibition (to 140 msec, 57% prestimulus firing rate). Bin size: 10 msec, 250 sweeps.

Ionotropic glutamate receptors and orthodromic activation of DR 5-HT neurons

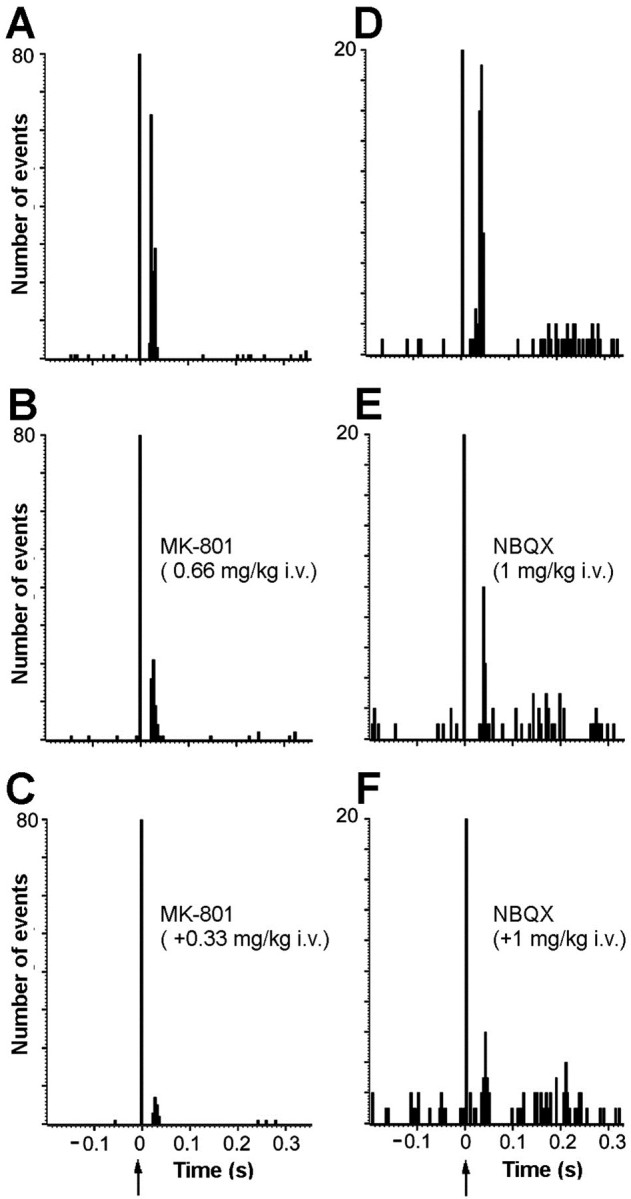

We assessed the involvement of ionotropic glutamate receptors in the mPFC-induced orthodromic activations of 5-HT neurons. Because the percentage of neurons activated was higher in rats depleted of 5-HT (Table 1), these experiments were performed in rats pretreated withpCPA (2 × 350 mg/kg, as above). The treatment with the NMDA receptor antagonist MK-801 (0.66–0.99 mg/kg, i.v.) markedly reduced the mPFC-induced orthodromic activation, from 40 ± 11 to 10 ± 4% (p < 0.05; paired Student'st test; n = 5). Figure7, B and C, shows the effect of MK-801 administration on the orthodromic activation of a representative DR 5-HT neuron.

Fig. 7.

Involvement of ionotropic glutamate receptors in the mPFC-induced activations of DR 5-HT neurons. A shows the baseline orthodromic activation (52%, latency 18–36 msec) of a 5-HT neuron after the stimulation of mPFC. B andC show, in the same neuron, the reversal of the excitation produced by increasing doses of the NMDA receptor antagonist (±)MK-801 (0.66 + 0.33 mg/kg, i.v.). Bin size: 4 msec, 240 sweeps.D shows the baseline orthodromic activation (21.2%, latency 26–48 msec) of another DR 5-HT neuron after the stimulation of mPFC. E and F show the reversal of the excitation produced by increasing doses of the AMPA–KA receptor antagonist NBQX (1 + 1 mg/kg, i.v.) in the neuron shown inD. Bin size: 4 msec, 225 sweeps.

To examine the involvement of local NMDA receptors on the mPFC-induced increase of 5-HT release in the DR, we performed an additional microdialysis experiment in chloral hydrate-anesthetized rats. In these, the NMDA receptor antagonist MK-801 (300 μm) was locally administered by reverse dialysis through the probe in the DR for 2 hr, beginning 1 hr before the mPFC stimulation (n= 7). In this condition, the delivery of electrical stimuli in the mPFC (20 min, 20 Hz, 1 msec, 0.5 mA) did not enhance the 5-HT release in the DR (Fig. 3B).

The administration of the AMPA–KA antagonist NBQX (1 + 1 mg/kg, i.v.) also reduced significantly the effect of the mPFC stimulation on the orthodromic activation of DR 5-HT neurons, from 29 ± 6 to 11 ± 3% (p < 0.01; paired t test;n = 5) (Fig. 7E,F).

Control of the 5-HT release in mPFC and DR by 5-HT1Areceptors in both areas

Systemic administration of 8-OH-DPAT

The basal 5-HT concentrations in the DR and mPFC in presence of 1 μm citalopram were 66 ± 13 fmol/fraction (n = 19) and 16 ± 1 fmol/fraction (n = 20), respectively.

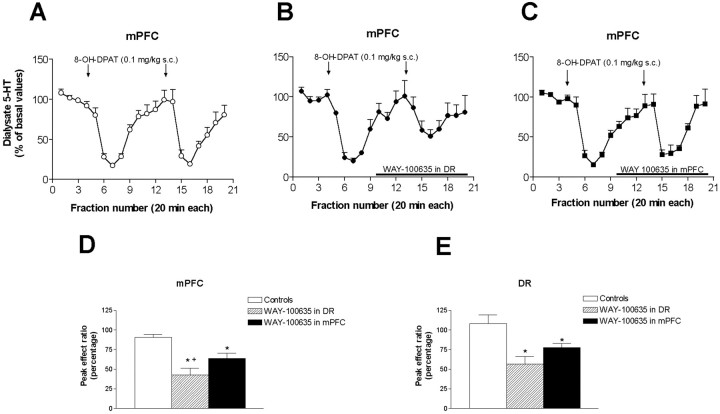

The administration of 8-OH-DPAT (0.1 mg/kg, s.c.) reduced the dialysate 5-HT concentration to 17.4 ± 2.1% of baseline in mPFC and to 36.7 ± 4.9% in the DR of the same rats. The 5-HT reduction was significantly more marked in mPFC than in DR (p < 0.003; Student's t test). In both areas, a second injection of 8-OH-DPAT reduced 5-HT to an extent similar to that of the first injection. The peak ratios (fraction 7/fraction 16) were close to unity (119 ± 12% in the DR, 101 ± 11 in mPFC;n = 6) (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Effect of the local application of WAY-100635 (100 μm) in the DR or mPFC on the reduction of 5-HT release elicited by 8-OH-DPAT (0.1 mg/kg, s.c.) in these areas of rats implanted with two dialysis probes. The graph in A shows the effect of two sequential injections of 8-OH-DPAT (arrows) on the 5-HT release in the mPFC (open circles). The perfusion of WAY-100635 (horizontal bar) in the DR (B, filled circles) or mPFC (C, filled squares) partly antagonized the effect of the second 8-OH-DPAT injection on 5-HT release in mPFC. The bar graph in Dshows the peak ratios between the maximal effects on 5-HT release in the mPFC elicited by the two 8-OH-DPAT injections in identical conditions (open bars; e.g., as in A) or during the infusion of WAY-100635 in the DR (striped bars; as in B) or mPFC (black bars, as in C). The bar graph in E shows the peak ratios of the maximal effects on 5-HT release elicited by the two 8-OH-DPAT injections (as in D) but in this case, referred to the effects on 5-HT release in the DR (for simplicity, the actual dialysate graphs in the DR are not shown). Data are means ± SEM of five or six rats per group.*p < 0.05 versus controls;+p < 0.05 versus WAY-100635 in mPFC.

The local application of 100 μm WAY-100635 in the DR or mPFC did not enhance the basal 5-HT release in neither area but partly prevented the reduction of 5-HT release elicited by the second 8-OH-DPAT injection in the DR and mPFC. Figure 8 shows the peak ratios for the groups of rats treated with 8-OH-DPAT (0.1 mg/kg, s.c.) in the control situation (both injections given in identical conditions) and when WAY-100635 was locally applied in the DR or mPFC during the second 8-OH-DPAT administration. One-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of the WAY-100635 application on peak ratios for the effects of 8-OH-DPAT in both regions (p < 0.03 in DR;p < 0.001 in mPFC). Post-hoc t test revealed the existence of a significantly lower reduction of the 5-HT release in DR or mPFC after the application of WAY-100635 in either area, although the attenuation of the effect was smaller when WAY-100635 was locally applied in the mPFC (Fig. 8).

To examine the extent of the diffusion of the local application of WAY-100635 by reverse dialysis, we performed an in vivoautoradiographic study in which 100 nm[3H]WAY-100635 was perfused together with cold 100 μm WAY-100635 in the DR. This area was chosen because of the concentration of 5-HT1A receptors in a small area of tissue. Rats were killed after 80 min of perfusion, sections were cut at different rostrocaudal levels of the DR, and the radioactivity in each section was counted by image analysis (see Materials and Methods). Figure9 shows the distribution of the tritium label at different rostrocaudal levels in the DR (n = 4). In the four rats examined, the [3H]WAY-100635 binding was confined within midbrain sections differing 1.2 ± 0.1 mm in their AP coordinate (e.g., ± 0.6 mm on average from the section containing the maximal labeling). Autoradiographic examination of other areas rich in 5-HT1A receptors, such as hippocampus or frontal cortex did not reveal any labeling above background in any of the four rats (data not shown).

Fig. 9.

Distribution of the ex vivo[3H]WAY-100635 binding along the rostrocaudal axis in the DR as measured autoradiographically in coronal midbrain sections. The histogram in A shows the mean ± SEM values of the [3H]WAY-100635 binding in 17 equally spaced coronal sections cut at different rostrocaudal levels (n = 4). B and Cshow, respectively, 10 autoradiograms of midbrain sections containing the DR and the amount of tritium label in each section. In this particular rat, tritium levels above background were found between approximately −7.6 to −8.7 mm from bregma. Note that the shape of the tritium label (dark spots in B) follows the track of the dialysis probe (30° inclination) and has a shape different from that of the DR, suggesting that not all 5-HT1A receptors within the DR were labeled by the perfusion of [3H]WAY-100635.

Local administration of 8-OH-DPAT in mPFC

In a second set of microdialysis experiments, we applied 8-OH-DPAT by reverse dialysis into the mPFC and we examined its effects on 5-HT release in this area and the DR. Baseline 5-HT values in dialysates from DR, mPFC, and lateral PFC were 54 ± 4 (n = 25), 15 ± 1 (n = 17), and 12 ± 1 fmol/fraction (n = 7), respectively. The application of 8-OH-DPAT induced a sustained reduction of 5-HT release in medial prefrontal cortex that was maximal at the end of the perfusion period (∼50% reduction) (p < 0.0001 vs controls, significant effect of time and of the time × treatment interaction; two-way repeated measures ANOVA) (Fig.10). A similar reduction was noted when 8-OH-DPAT was applied in lateral prefrontal cortex (p < 0.0001 vs controls, significant effects of time and of treatment × time interaction; two-way repeated measures ANOVA). The average values (baseline = 100%) for the 100 and 300 μm applications were 65 ± 5 and 50 ± 4 for mPFC and 61 ± 4 and 51 ± 4 for lateral PFC, respectively.

Fig. 10.

Effects of the local infusion of 100 and 300 μm 8-OH-DPAT in prefrontal cortex (PFC) on the 5-HT release in DR (A) and PFC (B). Control animals (open circles) received aCSF for the whole experiment (syringe changes were also performed in this group). The application of 8-OH-DPAT in medial prefrontal cortex (filled circles) significantly reduced the 5-HT release in this area and the DR. In contrast, the perfusion of 8-OH-DPAT in the lateral prefrontal cortex (filled triangles), an area devoid of neurons projecting to the DR reduced locally the 5-HT release but not in the DR. Data are from seven or eight rats per group.

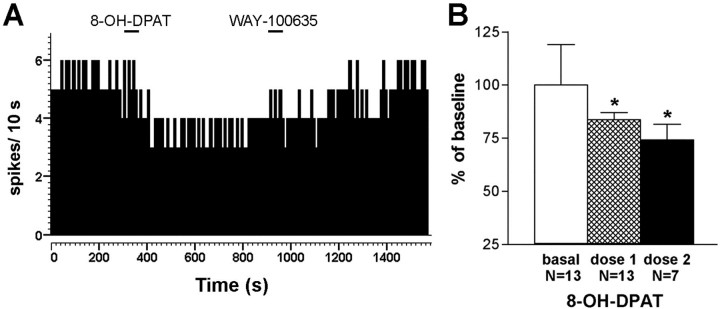

The application of 8-OH-DPAT in mPFC (but not in the lateral prefrontal cortex) was accompanied by a reduction of the 5-HT release in the DR, which was significantly different from controls (p <0.0001, significant treatment × time interaction; two-way repeated measures ANOVA) (Fig. 10). The average values in the DR during the period of infusion of 100 μm 8-OH-DPAT in mPFC were 100 ± 9 for controls (perfusion of aCSF), 77 ± 4 (8-OH-DPAT in mPFC), and 98 ± 3 (8-OH-DPAT in lateral PFC) (p < 0.02; one-way ANOVA). The corresponding values for the period of infusion of 300 μm 8-OH-DPAT were, respectively, 96 ± 9, 61 ± 5, and 95 ± 5 (p < 0.01, one-way ANOVA). Likewise, the single point application of 8-OH-DPAT (100 μm, 200 nl delivered in 1 min) at the coordinate used for mPFC stimulations significantly reduced the firing rate of 5-HT neurons in the DR (p < 0.01; paired Student's t test;n = 13) (Fig. 11). In seven rats, we infused a second dose of 8-OH-DPAT, which reduced the firing rate of 5-HT neurons in the DR further (p< 0.01, paired Student's t-test; n = 7).

Fig. 11.

Effect of 8-OH-DPAT in mPFC on the firing rate of DR 5-HT neurons. A, The local application of 8-OH-DPAT (0.2 μl, 100 μm, 1 min horizontal bar) in mPFC reduced the firing rate of a DR neuron. A return to baseline firing was observed after the local application of WAY-100635 (0.2 μl, 100 μm, 1 min horizontal bar). B, Mean ± SEM values of the firing rate of 13 DR neurons before and after the application of 8-OH-DPAT in mPFC as above. In seven neurons, the application of a second 8-OH-DPAT dose in mPFC reduced the firing rate further. *p < 0.02 versus baseline.

DISCUSSION

Two main findings derive from the present study. First, projection neurons in the mPFC control the activity of DR 5-HT neurons in a complex manner. Consistent with previous observations, we identified by antidromic activation a substantial number of mPFC neurons projecting monosynaptically to 5-HT neurons (Hajós et al., 1998). Secondly, postsynaptic 5-HT1A receptors in mPFC, possibly located in pyramidal neurons projecting to the DR, exert a distal feedback control of serotonergic activity.

Dual control of 5-HT neurons by mPFC afferents

The stimulation of the mPFC mainly inhibited 5-HT neuronal activity, as previously reported (Hajós et al., 1998). In some instances, this was accompanied by subthreshold (5–10%) activations, whereas 17% of neurons were clearly activated by mPFC stimulation. The abundance of inhibitions was inconsistent with the excitatory nature of projection (pyramidal) neurons in mPFC. We therefore reasoned that the excitation of some 5-HT neurons could increase 5-HT release in the DR, which, acting on 5-HT1A autoreceptors, would inhibit the same or other 5-HT neurons. This mechanism, assigning an important physiological role to raphe 5-HT1Aautoreceptors, is supported by the following observations. First, mPFC stimulation increased the 5-HT release in the DR at several stimulation conditions, including the one eliciting 5-HT neuronal inhibition. Second, the proportion of inhibitions encountered was dramatically reduced in pCPA-pretreated rats, which strongly supports the involvement of 5-HT in the mPFC-triggered inhibitions. Third, these were antagonized by the selective 5-HT1A receptor antagonist WAY-100635.

A previous report found that neither pCPA nor WAY-100635 reversed the mPFC-induced inhibitions in the DR, concluding that they were independent of 5-HT1A receptor activation (Hajós et al., 1998). Two reasons may account for this discrepancy. First, only high doses of pCPA, such as that used herein completely suppress serotonergic function (Chaput et al., 1990). Second, the dose of WAY-100635 used by Hajós et al. (1998)(100 μg/kg, i.v.) may inhibit 5-HT neuronal activity (Martin et al., 1999). In our hands, an intravenous dose of 5–10 μg/kg was sufficient to reverse the inhibitory effects of 5-HT1A receptor activation on 5-HT cell firing (Casanovas et al., 2000) (L. Romero, P. Celada, and F. Artigas, unpublished observations).

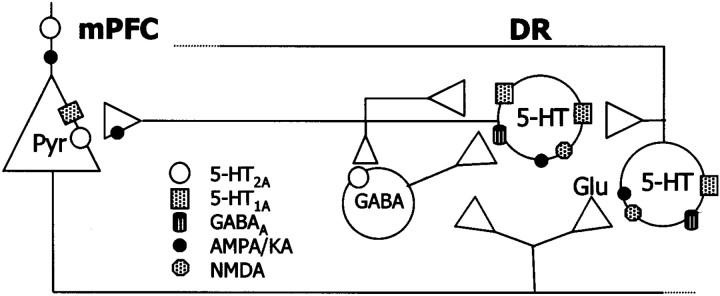

In addition to 5-HT1A autoreceptors, we present evidence that GABAA receptors also participate in the inhibitory effects of mPFC on serotonergic activity, because inhibitions were also reversed by picrotoxinin. The DR and adjacent periaqueductal gray matter (PAG) contain a large density of GABAergic elements (Nanopoulos et al., 1982; Belin et al., 1983; Abellán et al., 2000) and GABA suppresses the activity of 5-HT neurons (Gallager and Aghajanian, 1976). Given the existing anatomical and functional relationships between the mPFC, the DR, and the PAG (Thierry et al., 1983; Takagishi et al., 1991; Jolas and Aghajanian, 1997) mPFC afferents to the DR or PAG could inhibit the activity of 5-HT neurons through the activation of local GABAergic inputs (Fig.12).

Fig. 12.

Schematic representation of the putative relationships between projection neurons in mPFC and DR 5-HT neurons. Descending excitatory afferents from the mPFC control the activity of 5-HT neurons directly, via NMDA and AMPA–KA receptors, and indirectly, via activation of local inhibitory (5-HT1A and GABAA) receptors. The stimulus-induced excitation of neurons receiving a direct input from the mPFC (either 5-HT or GABAergic) releases 5-HT or GABA, which inhibit other 5-HT neurons via 5-HT1A or GABAA receptors. The involvement of 5-HT1A receptors in the mPFC-induced inhibitions of 5-HT neurons is supported by the decrease in the proportion of inhibitions in rats depleted of 5-HT (Table 1) and by the reversal of the inhibitions induced by 5-HT1A receptor blockade with WAY-100635. Additionally, GABAergic inputs may also occur via a serotonergic control of GABA interneurons (Liu et al., 2000). The firing activity of 5-HT neurons and the release of 5-HT in midbrain and forebrain are dependent on the activation of 5-HT1Aautoreceptors in the DR. However, the activation by 8-OH-DPAT of postsynaptic 5-HT1A receptors on cortical pyramidal neurons also reduces 5-HT cell firing in the DR and 5-HT release in the DR and mPFC, likely through the inhibition of the activity of excitatory inputs from the mPFC to the DR. Thus, pyramidal 5-HT1Areceptors in mPFC are a second population of 5-HT1Areceptors controlling serotonergic activity.

Previous in vitro evidence indicates that ionotropic glutamate receptors are involved in the excitatory control of 5-HT neurons (Pan and Williams, 1989), but no evidence was available that this occurred in vivo. Moreover, the anatomical source of this excitatory input was unknown. Our observations suggest that mPFC afferents control 5-HT neuron activity in vivo through AMPA–KA and NMDA receptors because NBQX and MK-801 antagonized the orthodromic excitations produced by mPFC stimulation (we used 5-HT-depleted rats to increase the proportion of excitations). These observations parallel the effects of glutamatergic agonists on 5-HT release in the DR (Tao and Auerbach, 1996; Tao et al., 1997). Likewise, MK-801 pretreatment prevented the increase in DR 5-HT release produced by the mPFC stimulation, which supports that this was caused by an increased glutamatergic input. Interestingly, the higher stimulation frequency used induced a persistent elevation of the 5-HT release, which was accompanied by an increased firing rate. Given the involvement of NMDA receptors in long-term potentiation (Malenka and Nicoll, 1999), the present results suggest that endogenous glutamate from stimulated mPFC afferents, acting on NMDA receptors, would induce a sustained facilitation of serotonergic activity.

Control of serotonergic activity by 5-HT1A receptors in mPFC

The inhibition of 5-HT synthesis and release elicited by the systemic administration of selective 5-HT1Aagonists was attributed to the exclusive activation of raphe 5-HT1A autoreceptors (Hjorth et al., 1987; Hutson et al., 1989) mainly because the activation of 5-HT1A receptors hyperpolarized 5-HT neurons and reduced cell firing (Aghajanian and Lakoski, 1984; Sprouse and Aghajanian, 1987). Consistently, the application of direct or indirect 5-HT1A receptor agonists in the raphe nuclei decreased 5-HT synthesis and release in forebrain (Hutson et al., 1989;Adell and Artigas, 1991; Invernizzi et al., 1991; Adell et al., 1993).

The present results indicate that postsynaptic 5-HT1A receptors in mPFC, possibly on pyramidal neurons projecting to the DR, also control 5-HT neuron activity and 5-HT release. First, the local application of 8-OH-DPAT in mPFC reduced the firing rate of DR 5-HT neurons. Diffusion to the DR is unlikely to play a significant role because of the limited diffusion of the small volume (200 nl) used in recording experiments (Myers, 1971). Second, the application of 8-OH-DPAT in mPFC, but not in lateral prefrontal cortex, reduced the 5-HT release in the DR. The lateral prefrontal cortex contains 5-HT1A receptors (Pompeiano et al., 1992) but lacks projections to the DR (Peyron et al., 1998). This characteristic facilitated the assessment of the specificity of the changes observed in the DR when 8-OH-DPAT was applied in mPFC.

The reduction of 5-HT release in mPFC by local 8-OH-DPAT application agrees with previous data (Casanovas et al., 1999). However, 8-OH-DPAT unexpectedly reduced 5-HT release in lateral prefrontal cortex. Given the apparent absence of terminal 5-HT1A receptors (Kia et al., 1996), a tentative explanation for this finding is that postsynaptic 5-HT1A receptors may additionally control the 5-HT release by local changes in glutamatergic transmission. Hence, the 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptor agonist DOI, locally applied in mPFC, increased 5-HT release through a 5-HT2A- and AMPA–KA-dependent mechanism (Martin-Ruiz et al., 2001). Because of the opposite effects of 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptor activation on pyramidal neuron excitability (Araneda and Andrade, 1991) 8-OH-DPAT might have effects opposed to those of DOI on 5-HT release.

Consistent with the well established role of DR 5-HT1A autoreceptors in the control of 5-HT release, the application of WAY-100635 in the DR antagonized the reduction in 5-HT release elicited by systemic 8-OH-DPAT administration. The effect of WAY-100635 was partial, in agreement with its limited diffusion within the DR, as exemplified by [3H]WAY-100635. Likewise, the application of WAY-100635 in mPFC also antagonized the effects of systemic 8-OH-DPAT administration on 5-HT release. This effect is most likely attributable to the antagonism of the action of 8-OH-DPAT at postsynaptic 5-HT1A receptors in pyramidal neurons (Pompeiano et al., 1992; Kia et al., 1996) and adds to the above electrophysiological and neurochemical observations indicating that postsynaptic 5-HT1A receptors in mPFC control serotonergic activity. WAY-100635 antagonized the effect of systemic 8-OH-DPAT more when applied in the DR than in mPFC, possibly because of the key role of DR 5-HT1Aautoreceptors, but also to the fact that unilateral applications in the mPFC affected half of the putative afferents to the DR (Peyron et al., 1998). Moreover, not all 5-HT neurons may be controlled by mPFC afferents.

Given the marked control of 5-HT function by 5-HT1A receptors, a potential confounding factor in the present microdialysis experiments could be the use of citalopram in the perfusion fluid. However, 1 μm citalopram inhibits partially 5-HT reuptake (Hervás et al., 2000) in a small tissue area surrounding the probe, causing little activation of 5-HT1A autoreceptors in the DR (Tao et al., 2000). Higher concentrations (typically >10 μm) are required to significantly activate 5-HT1Areceptors and reduce 5-HT release (Tao et al., 2000). Consistently, 1 μm citalopram did not interfere with the local or systemic actions of 5-HT1A receptor ligands on 5-HT release in midbrain or forebrain (Casanovas et al., 1997, 1999;Adell and Artigas, 1998). On the other hand, citalopram was required to mask the in vivo uptake inhibitory properties of 8-OH-DPAT (Adell et al., 1993; Assié and Koek, 1996), which would confound its effect on 5-HT1A receptors.

Conclusions

The present results indicate that the activity of DR 5-HT neurons is strongly regulated by the mPFC. Presynaptic and postsynaptic 5-HT1A receptors, as well as GABAA and glutamate ionotropic receptors are involved in this control (Fig. 12). In particular, 5-HT1A autoreceptors in the DR may play a pivotal role in the physiological control of ascending 5-HT pathways, attenuating excessive activation of 5-HT neurons by excitatory afferents from the mPFC. A corollary of the present observations is that mPFC afferents may differentially drive the activity of 5-HT neurons projecting to different forebrain structures, depending on whether these cells are activated or inhibited (indirectly) by mPFC afferents. Likewise, postsynaptic 5-HT1Areceptors in mPFC exert a distal feedback control of serotonergic activity through the modulation of descending excitatory afferents to the DR. Given the involvement of the serotonergic system in mood control, perception and cognition, the reciprocal interactions between the mPFC and the DR may play an important role in the pathophysiology and treatment of severe psychiatric illnesses, including depression and schizophrenia.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Fondo de Investigacion Sanitaria Grant 01/1147 and Comision Interministerial de Ciencia y Tecnologia Grant SFA2001-2133. Financial support from Bayer S.A. is also acknowledged. We thank the drug companies for the generous supply of drugs. M.V.P. is recipient of a predoctoral fellowship from the Institut d'Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer. The technical help of Leticia Campa is gratefully acknowledged.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Francesc Artigas, Department of Neurochemistry, Institut d' Investigacions Biomèdiques de Barcelona Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (Institut d'Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer), Rosselló 161, Sixth Floor, 08036 Barcelona, Spain. E-mail:fapnqi@iibb.csic.es.

G. Guillazo's present address: Department of Psychobiology and Methodology, Autonomous University of Barcelona, 08193 Bellaterra, Spain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abellán MT, Adell A, Honrubia MA, Mengod G, Artigas F. GABA(B)-RI receptors in serotonergic neurons: effects of baclofen on 5-HT output in rat brain. NeuroReport. 2000;11:941–945. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200004070-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adell A, Artigas F. Differential effects of clomipramine given locally or systemically on extracellular 5-hydroxytryptamine in raphe nuclei and frontal cortex. An in vivo microdialysis study. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1991;343:237–244. doi: 10.1007/BF00251121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adell A, Artigas F. A microdialysis study of the in vivo release of 5-HT in the median raphe nucleus of the rat. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;125:1361–1367. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adell A, Carceller A, Artigas F. In vivo brain dialysis study of the somatodendritic release of serotonin in the raphe nuclei of the rat. Effects of 8-hydroxy-2-(di-n-propylamino)tetralin. J Neurochem. 1993;60:1673–1681. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb13390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aghajanian GK, Lakoski JM. Hyperpolarization of serotonergic neurons by serotonin and LSD: studies in brain slices showing increased K+ conductance. Brain Res. 1984;305:181–185. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)91137-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aghajanian GK, Marek GJ. Serotonin model of schizophrenia: emerging role of glutamate mechanisms. Brain Res Rev. 2000;31:302–312. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(99)00046-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aghajanian GK, Wang RY. Habenular and other midbrain raphe afferents demonstrated by a modified retrograde tracing technique. Brain Res. 1977;122:229–242. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(77)90291-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aghajanian GK, Sprouse JS, Rasmussen K. Physiology of the midbrain serotonin system. In: Meltzer HY, editor. Psychopharmacology: the third generation of progress. Raven; New York: 1987. pp. 141–149. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andreasen NC, O'Leary DS, Flaum M, Nopoulos P, Watkins GL, Boles Ponto LL, Hichwa RD. Hypofrontality in schizophrenia: distributed dysfunctional circuits in neuroleptic-naive patients. Lancet. 1997;349:1730–1734. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)08258-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Araneda R, Andrade R. 5-Hydroxytryptamine2 and 5-hydroxytryptamine1A receptors mediate opposing responses on membrane excitability in rat association cortex. Neuroscience. 1991;40:399–412. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90128-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Assié MB, Koek W. Possible in vivo 5-HT reuptake blocking properties of 8-OH-DPAT assessed by measuring hippocampal extracellular 5-HT using microdialysis in rats. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;119:845–850. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15749.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Azmitia EC, Segal M. An autoradiographic analysis of the differential ascending projections of the dorsal and median raphe nuclei in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1978;179:641–668. doi: 10.1002/cne.901790311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baraban JM, Aghajanian GK. Suppression of serotonergic neuronal firing by alpha-adrenoceptor antagonists: evidence against GABA mediation. Eur J Pharmacol. 1980;66:287–294. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(80)90461-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Belin MF, Nanopoulos D, Didier M, Aguera M, Steinbusch H, Verhofstad A, Maitre M, Pujol JF. Inmunohistochemical evidence for the presence of gamma-aminobutyric acid and serotonin in one nerve cell. A study on the raphe nuclei of the rat using antibodies to glutamate decarboxylase and serotonin. Brain Res. 1983;275:329–339. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)90994-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blier P, de Montigny C. Modification of 5-HT neuron properties by sustained administration of the 5-HT1A agonist gepirone: electrophysiological studies in the rat brain. Synapse. 1987;1:470–480. doi: 10.1002/syn.890010511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Casanovas JM, Lesourd M, Artigas F. The effect of the selective 5-HT1A agonists alnespirone (S-20499) and 8-OH-DPAT on extracellular 5-hydroxytryptamine in different regions of rat brain. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;122:733–741. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Casanovas JM, Hervás I, Artigas F. Postsynaptic 5-HT1A receptors control 5-HT release in the rat medial prefrontal cortex. NeuroReport. 1999;10:1441–1445. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199905140-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Casanovas JM, Berton O, Celada P, Artigas F. In vivo actions of the selective 5-HT1A receptor agonist BAY x 3702 on serotonergic cell firing and release. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2000;362:248–254. doi: 10.1007/s002100000291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ceci A, Baschirotto A, Borsini F. The inhibitory effect of 8-OH-DPAT on the firing activity of dorsal raphe neurons in rats is attenuated by lesion of the frontal cortex. Neuropharmacology. 1994;33:709–713. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(94)90177-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Celada P, Siuciak JA, Tran TM, Altar CA, Tepper JM. Local infusion of brain-derived neurotrophic factor modifies the firing pattern of dorsal raphe serotonergic neurons. Brain Res. 1996;712:293–298. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01469-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chaput Y, Lesieur P, de Montigny C. Effects of short-term serotonin depletion on the efficacy of serotonin neurotransmission: electrophysiological studies in the rat central nervous system. Synapse. 1990;6:328–337. doi: 10.1002/syn.890060404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drevets WC, Price JL, Simpson JR, Todd RD, Reich T, Vannier M, Raichle ME. Subgenual prefrontal cortex abnormalities in mood disorders. Nature. 1997;386:824–827. doi: 10.1038/386824a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fuller JH, Schlag JD. Determination of antidromic excitation by the collision test: problems of interpretation. Brain Res. 1976;112:283–298. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(76)90284-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fuster JM. The prefrontal cortex. Anatomy, physiology and neuropsychology of the frontal lobe. Lippincott-Raven; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gallager DW, Aghajanian GK. Effect of antipsychotic drugs on the firing of dorsal raphe cells. II. Reversal by picrotoxin. Eur J Pharmacol. 1976;39:357–364. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(76)90145-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gozlan H, Thibault S, Laporte AM, Lima L, Hamon M. The selective 5-HT1A antagonist radioligand [3H]WAY 100635 labels both G-protein-coupled and free 5-HT1A receptors in rat brain membranes. Eur J Pharmacol Mol Pharmacol. 1995;288:173–186. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(95)90192-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hajós M, Richards CD, Szekely AD, Sharp T. An electrophysiological and neuroanatomical study of the medial prefrontal cortical projection to the midbrain raphe nuclei in the rat. Neuroscience. 1998;87:95–108. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00157-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hajós M, Hajos-Korsok E, Sharp T. Role of the medial prefrontal cortex in 5-HT1A receptor-induced inhibition of 5-HT neuronal activity in the rat. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;126:1741–1750. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hervás I, Queiroz CM, Adell A, Artigas F. Role of uptake inhibition and autoreceptor activation in the control of 5-HT release in the frontal cortex and dorsal hippocampus of the rat. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;130:160–166. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hjorth S, Carlsson A, Magnusson T, Arvidsson LE. In vivo characterization of 8-OH-DPAT: evidence for 5-HT receptor selectivity and agonist action in the rat CNS. In: Dourish CT, Ahlenius S, Hutson PH, editors. Brain 5-HT1A receptors. Ellis Horwood; Chichester, UK: 1987. pp. 94–105. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hutson PH, Sarna GS, O'Connell MT, Curzon G. Hippocampal 5-HT synthesis and release in vivo is decreased by infusion of 8-OH-DPAT into the nucleus raphe dorsalis. Neurosci Lett. 1989;100:276–280. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(89)90698-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Invernizzi R, Carli M, Di Clemente A, Samanin R. Administration of 8-Hydroxy-2-(di-n-propylamino)tetralin in raphe nuclei dorsalis and medianus reduces serotonin synthesis in the rat brain: differences in potency and regional sensitivity. J Neurochem. 1991;56:243–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1991.tb02587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jacobs BL, Azmitia EC. Structure and function of the brain serotonin system. Physiol Rev. 1992;72:165–229. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1992.72.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jolas T, Aghajanian GK. Opioids suppress spontaneous and NMDA-induced inhibitory postsynaptic currents in the dorsal raphe nucleus of the rat in vitro. Brain Res. 1997;755:229–245. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00103-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kalén P, Wiklund L. Projections from the medial septum and diagonal band of Broca to the dorsal and central superior raphe nuclei: a non-cholinergic pathway. Exp Brain Res. 1989;75:401–416. doi: 10.1007/BF00247947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khawaja X, Evans N, Reilly Y, Ennis C, Minchin MCW. Characterisation of the binding of [3H]WAY-100635, a novel 5-hydroxytryptamine(1A) receptor antagonist, to rat brain. J Neurochem. 1995;64:2716–2726. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.64062716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kia HK, Miquel MC, Brisorgueil MJ, Daval G, Riad M, El Mestikawy S, Hamon M, Vergé D. Immunocytochemical localization of serotonin(1A) receptors in the rat central nervous system. J Comp Neurol. 1996;365:289–305. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960205)365:2<289::AID-CNE7>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu RJ, Jolas T, Aghajanian GK. Serotonin 5-HT2 receptors activate local GABA inhibitory inputs to serotonergic neurons of the dorsal raphe nucleus. Brain Res. 2000;873:34–45. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02468-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Malenka RC, Nicoll RA. Long-term potentiation–a decade of progress? Science. 1999;285:1870–1874. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5435.1870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martin LP, Jackson DM, Wallsten C, Waszczak BL. Electrophysiological comparison of 5-hydroxytryptamine(1A) receptor antagonists on dorsal raphe cell firing. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;288:820–826. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martin-Ruiz R, Puig MV, Celada P, Shapiro DA, Roth BL, Mengod G, Artigas F (2001) Control of serotonergic function in medial prefrontal cortex by serotonin-2A receptors through a glutamate-dependent mechanism. J Neurosci 21:xxx. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Meltzer HY. The role of serotonin in antipsychotic drug action. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;21:S106–S115. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Montgomery SA. Long-term treatment of depression. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1994;26:31–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Murase S, Grenhoff J, Chouvet G, Gonon FG, Svensson TH. Prefrontal cortex regulates burst firing and transmitter release in rat mesolimbic dopamine neurons studied in vivo. Neurosci Lett. 1993;157:53–56. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90641-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Myers RD. Methods for chemical stimulation of the brain. In: Myers RD, editor. Methods of psychobiology, Vol 1. Academic; New York: 1971. pp. 247–280. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nanopoulos D, Belin MF, Maitre M, Vincendon G, Pujol JF. Immunocytochemical evidence for the existence of GABAergic neurones in the nucleus raphe dorsalis. Possible existence of neurones containing serotonin and GABA. Brain Res. 1982;232:375–389. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)90281-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pan ZZ, Williams JT. GABA- and glutamate-mediated synaptic potentials in rat dorsal raphe neurons in vitro. J Neurophysiol. 1989;61:719–726. doi: 10.1152/jn.1989.61.4.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Academic; Sydney: 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pazos A, Palacios JM. Quantitative autoradiographic mapping of serotonin receptors in the rat brain. I. Serotonin-1 receptors. Brain Res. 1985;346:205–230. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90856-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peyron C, Luppi PH, Kitahama K, Fort P, Hermann DM, Jouvet M. Origin of the dopaminergic innervation of the rat dorsal raphe nucleus. NeuroReport. 1995;6:2527–2531. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199512150-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Peyron C, Luppi PH, Fort P, Rampon C, Jouvet M. Lower brainstem catecholamine afferents to the rat dorsal raphe nucleus. J Comp Neurol. 1996;364:402–413. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960115)364:3<402::AID-CNE2>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Peyron C, Petit JM, Rampon C, Jouvet M, Luppi PH. Forebrain afferents to the rat dorsal raphe nucleus demonstrated by retrograde and anterograde tracing methods. Neuroscience. 1998;82:443–468. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00268-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pompeiano M, Palacios JM, Mengod G. Distribution and cellular localization of mRNA coding for 5-HT1A receptor in the rat brain: correlation with receptor binding. J Neurosci. 1992;12:440–453. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-02-00440.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pompeiano M, Palacios JM, Mengod G. Distribution of the serotonin 5-HT2 receptor family mRNAs: comparison between 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptors. Mol Brain Res. 1994;23:163–178. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(94)90223-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reader TA, Briere R, Grondin L, Ferron A. Effects of p-chlorophenylalanine on cortical monoamines and on the activity of noradrenergic neurons. Neurochem Res. 1986;11:1025–1035. doi: 10.1007/BF00965591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Romero L, Artigas F. Preferential potentiation of the effects of serotonin uptake inhibitors by 5-HT1A receptor antagonists in the dorsal raphe pathway: role of somatodendritic autoreceptors. J Neurochem. 1997;68:2593–2603. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68062593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Romero L, Celada P, Artigas F. Reduction of in vivo striatal 5-hydroxytryptamine release by 8-OH-DPAT after inactivation of Gi/Go proteins in dorsal raphe nucleus. Eur J Pharmacol. 1994;265:103–106. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)90230-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sawyer SF, Tepper JM, Young SJ, Groves PM. Antidromic activation of dorsal raphe neurons from neostriatum: physiological characterization and effects of terminal autoreceptor activation. Brain Res. 1985;332:15–28. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90385-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sesack SR, Pickel VM. Prefrontal cortical efferents in the rat synapse on unlabeled neuronal targets of catecholamine terminals in the nucleus accumbens septi and on dopamine neurons in the ventral tegmental area. J Comp Neurol. 1992;320:145–160. doi: 10.1002/cne.903200202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sesack SR, Deutch AY, Roth RH, Bunney BS. Topographical organization of the efferent projections of the medial prefrontal cortex in the rat: an anterograde tract-tracing study with Phaseolus vulgaris leucoagglutinin. J Comp Neurol. 1989;290:213–242. doi: 10.1002/cne.902900205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sprouse JS, Aghajanian GK. Electrophysiological responses of serotonergic dorsal raphe neurons to 5-HT1A and 5-HT1B agonists. Synapse. 1987;1:3–9. doi: 10.1002/syn.890010103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stern WC, Johnson A, Bronzino JD, Morgane PJ. Neurpharmacology of the afferent projections from the lateral habenula and substantia nigra to the anterior raphe in the rat. Neuropharmacology. 1981;20:979–989. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(81)90029-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Takagishi M, Chiba T. Efferent projections of the infralimbic (area 25) region of the medial prefrontal cortex in the rat: an anterograde tracer PHA-L study. Brain Res. 1991;566:26–39. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91677-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tao R, Auerbach SB. Differential effect of NMDA on extracellular serotonin in rat midbrain raphe and forebrain sites. J Neurochem. 1996;66:1067–1075. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.66031067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tao R, Ma Z, Auerbach SB. Influence of AMPA/kainate receptors on extracellular 5-hydroxytryptamine in rat midbrain raphe and forebrain. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;121:1707–1715. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tao R, Ma ZY, Auerbach SB. Differential effect of local infusion of serotonin reuptake inhibitors in the raphe versus forebrain and the role of depolarization-induced release in increased extracellular serotonin. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;294:571–579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Thierry AM, Deniau JM, Chevalier G, Ferron A, Glowinski J. An electrophysiological analysis of some afferent and efferent pathways of the rat prefrontal cortex. Prog Brain Res. 1983;58:257–261. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)60027-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang RY, Aghajanian GK. Antidromically identified serotonergic neurons in the rat midbrain raphe: evidence for collateral inhibition. Brain Res. 1977;132:186–193. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(77)90719-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]