Abstract

We isolated two mutants defective in the uptake of exogenous serotonin (5-HT) into the neurosecretory motor neurons ofCaenorhabditis elegans. These mutants were hypersensitive to exogenous 5-HT and hyper-responsive in the experience-dependent enhanced slowing response to food modulated by 5-HT. The two allelic mutations defined the gene mod-5(modulation of locomotion defective), which encodes the only serotonin reuptake transporter (SERT) in C. elegans. The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor fluoxetine (Prozac) potentiated the enhanced slowing response, and this potentiation requiredmod-5 function, establishing a 5-HT- and SERT-dependent behavioral effect of fluoxetine in C. elegans. By contrast, other responses of C. elegans to fluoxetine were independent of MOD-5 SERT and 5-HT. Further analysis of the MOD-5-independent behavioral effects of fluoxetine could lead to the identification of novel targets of fluoxetine and could facilitate the development of more specific human pharmaceuticals.

Keywords: C. elegans, SERT, fluoxetine, serotonin, reuptake, modulation of behavior, SSRI

The activity of serotonin (5-HT), a key neuromodulator, is mediated postsynaptically through metabotropic (Martin et al., 1998) and ionotropic (Maricq et al., 1991; Ranganathan et al., 2000) 5-HT receptors and their downstream signaling components (Hille, 1992). 5-HT modulates several behaviors of the nematodeCaenorhabditis elegans, including egg laying and locomotion (Horvitz et al., 1982; Trent et al., 1983; Avery and Horvitz, 1990;Schafer and Kenyon, 1995). 5-HT also mediates the enhanced slowing response exhibited by food-deprived nematodes after they encounter bacteria (Sawin et al., 2000). 5-HT neurotransmission can be regulated by the removal of 5-HT from the synaptic cleft by a serotonin reuptake transporter (SERT; Cooper et al., 1996). Na+/Cl−-dependent SERTs were cloned first from rats (Blakely et al., 1991; Hoffman et al., 1991) and subsequently from other species (Mortensen et al., 1999, and references therein), including humans and Drosophila melanogaster. SERT antagonists, such as the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) fluoxetine (Prozac), paroxetine (Paxil), and sertraline (Zoloft), are broadly used in the treatment of psychiatric disorders (Schloss and Williams, 1998). Therefore, in addition to the basic question of SERT function and regulation, it is of particular clinical importance to understand SERT function in vivo. SERT-deficient mice do not show gross developmental defects but have reduced 5-HT levels in the brain (Bengel et al., 1998), are insensitive to 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (ecstasy)-induced hyperactivity (Bengel et al., 1998), and show a brain region- and gender-specific reduction in the density and expression of 5-HT1a receptors (Li et al., 2000). However, no obvious behavioral defects or abnormal responses to SSRIs in these SERT-deficient mice have been reported.

In this article, we report the isolation of two C. elegans SERT-deficient mutants and describe studies of these mutants revealing that the C. elegans SERT is required for the experience-dependent enhanced slowing response and that the SSRI fluoxetine can act on both 5-HT- and SERT-dependent and -independent targets.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

mod-5 mapping, cloning, and cDNA. Nematodes were grown at 20°C as described previously (Brenner, 1974), except that Escherichia coli strain HB101 rather than OP50 was used as the food source (Sawin et al., 2000). Wild-type animals wereC. elegans strain N2. mod-5(n822) andmod-5(n823) were isolated from a genetic screen in which clonal populations of F3 animals descended from P0 animals mutagenized with ethyl methanesulfonate (Brenner, 1974) were pretreated with 5-HT (15 min incubation in 500 μl of 13 mm 5-HT followed by two washes with M9) (Wood et al., 1988) and then examined for the presence of formaldehyde-induced fluorescence (FIF) (Sulston et al., 1975) in the neurosecretory motor neurons (NSMs).mod-5(n3314) was isolated from a library of animals mutagenized with UV illumination and trimethylpsoralen (Jansen et al., 1997). The deletion library was constructed essentially as described previously (Jansen et al., 1997; Liu et al., 1999; P. Reddien, R. Ranganathan, and H. R. Horvitz, unpublished results).mod-5(n3314) was outcrossed to the wild type six times before behavioral assays. mod-5(n823) was mapped to linkage group I (LG I) on the basis of two-factor linkage to dpy-5 unc-75 I. The following three-factor data were obtained:mod-5 (47/47) dpy-5 (0/47)unc-75, mod-5 (35/35) unc-73 (0/35)lin-44 dpy-5, lin-6 (27/27) lin-17(0/27) mod-5, lin-17 (13/13) fog-1(0/13) mod-5, and fog-1 (3/26) mod-5(23/26) unc-11. All mapping experiments were performed by mating hermaphrodites homozygous for the recombinant chromosome withmod-5(n823) males and scoring the F1 cross progeny for 5-HT hypersensitivity at 5 min in 10 mm 5-HT. Germ line transformation experiments (Mello et al., 1991) were performed by injecting various constructs with 80 μg/ml pl15EK (which contains the wild-type lin-15 gene) into a mod-5(n823); lin-15(n765ts) strain and scoring 5-HT sensitivity in transgenic lines that produced non-Lin progeny at 22.5°C. Long-range PCR was performed using the Advantage cDNA PCR kit (Clontech, Cambridge, UK). DNA sequences were determined using an automated ABI 373A DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). RT-PCR was performed with primers corresponding to exons predicted by Genefinder (C. elegans Sequencing Consortium, 1998). The 5′ and 3′ ends of themod-5 cDNA were determined using 5′- and 3′-rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) kits (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD), respectively. To construct the mod-5minigene, we used PCR and primers that contained restriction enzyme sites at their ends to amplify 2.7 kb of the mod-5 promoter region. A PstI–BamHI fragment of this PCR product was ligated into the pPD49.26 vector (A. Fire, Carnegie Institute of Washington, Baltimore, MD) digested withPstI and BamHI. This mod-5 promoter construct was then digested with NcoI and SacI and ligated to an NcoI–SacI fragment of themod-5 coding region that was PCR-amplified in a manner similar to that used for the mod-5 promoter region.

Laser microsurgery. Neurons were ablated during the second larval stage using a laser microbeam, as described previously (Avery and Horvitz, 1987; Bargmann and Horvitz, 1991). Behavioral assays of young adult animals were performed 2 d later. Mock-ablated animals were animals transferred to agar pads and anesthetized in parallel to the animals that underwent laser ablation. Sawin et al. (2000)described details concerning how ablated animals were assayed sequentially in each of the different behavioral conditions.

Neurotransmitter and drug pretreatment and behavioral assays. The locomotory rate was assayed and 5-HT-containing plates were prepared as described previously (Sawin et al., 2000). Fluoxetine (HCl salt; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was dissolved in water, and 400 μl of a 25× stock solution were added to each 5 cm plate, containing ∼10 ml of agar, to obtain the various final concentrations of fluoxetine. The plates were allowed to dry at room temperature with their lids removed for >2 hr.

To assay 5-HT hypersensitivity, we placed 20 animals in 200 μl of 5-HT solution (creatinine sulfate salt; Sigma; dissolved in M9 buffer;Wood et al., 1988) in 96-well microtiter wells and scored the swimming behavior of the animals as either active or immobile at 5 min; an animal was scored as immobile if it did not exhibit any swimming motion for 5 sec. Fluoxetine-induced paralysis was scored in a similar manner at 10 min.

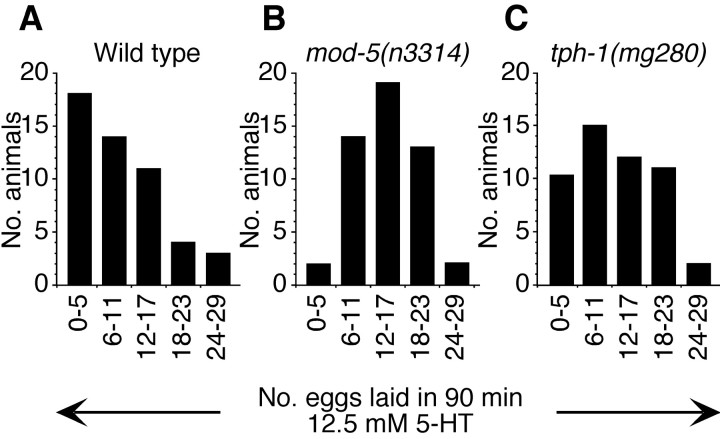

Egg-laying assays were performed as described previously (Trent et al., 1983). Briefly, 1-d-old adult animals (staged by picking late fourth larval stage animals 36 hr before the assay) were placed in wells of microtiter dishes containing 100 μl of 12.5 mm5-HT or 500 μg/ml fluoxetine, and the number of eggs laid was counted after 90 min.

5-HT-uptake assays in vivo. FIF assays were performed as described previously (Sulston et al., 1975). For the anti-5-HT antisera experiments shown in Figure 1B, mod-5(n823); cat-4 and cat-4; lin-15(n765ts) double mutants were grown at 20°C, and animals of both genotypes were incubated separately on plates containing 2 mm 5-HT and bacteria (for details concerning how plates were prepared, see Sawin et al., 2000) for 2 h and then incubated on plates with bacteria but without 5-HT for 30 min. Controls without exogenous 5-HT were similarly treated in parallel. Before fixation, mod-5(n823); cat-4 andcat-4; lin-15 double mutants preincubated on 5-HT-containing plates were combined, and mod-5(n823); cat-4 andcat-4; lin-15 double mutants preincubated on control plates were combined. 5-HT staining was performed as described previously (Desai et al., 1988) using affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal anti-5-HT antisera (H. Steinbusch, Maastrict University, Maastrict, the Netherlands). The cat-4; lin-15 mutants were not defective in the uptake of 5-HT (data not shown) and served as internal controls for each staining reaction. These animals could be distinguished from the test animals by the Multivulva phenotype caused bylin-15. Neurons with bright staining in cell bodies, axonal processes, and varicosities were termed “bright,” and neurons with weak staining in just the cell bodies and axonal processes were termed “weak.” For the results in Table 1, the procedure was essentially the same, except that the animals experienced an additional 1 hr incubation on control or fluoxetine-containing plates before the 2 hr incubation with 5-HT but did not experience the 30 min incubation on plates without drug after the 5-HT preincubation (for details, see Table 1 legend). lin-15 adult animals grown at 22.5°C were added to all plates at the first incubation step, and these animals served as internal controls for the staining reaction.

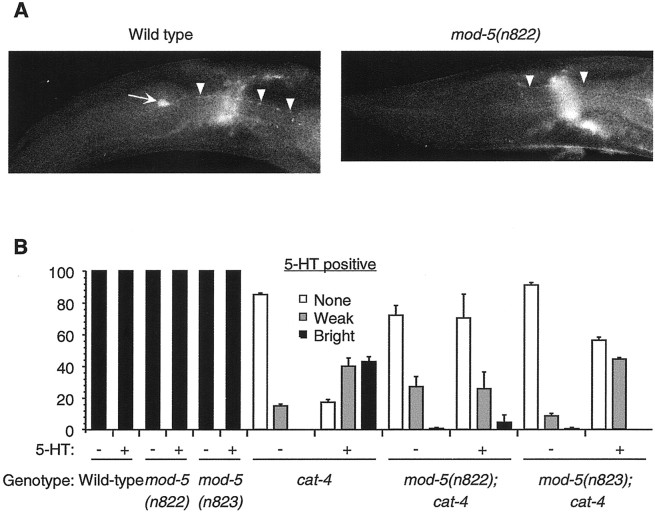

Fig. 1.

The NSMs of mod-5 mutants are defective in 5-HT uptake. A, Wild-type andmod-5(n822) animals preincubated with exogenous 5-HT were stained using FIF to visualize 5-HT (Sulston et al., 1975).Arrow, NSM cell body; arrowheads, NSM axonal processes. No NSM cell bodies were FIF-positive inmod-5(n822) mutants. The fluorescence seen in the axonal processes may be the consequence of partial 5-HT reuptake activity (seeB). B, NSMs in mod-5(n822)and mod-5(n823) mutants show reduced uptake of exogenous 5-HT when assayed using anti-5-HT antibodies. The mutationcat-4(e1141) was included to reduce the levels of endogenous 5-HT, which would otherwise obscure the detection of 5-HT uptake. At least 100 animals were tested for each genotype in each condition. For details, see Materials and Methods. Error bars indicate SEM.

Table 1.

Fluoxetine phenocopies mod-5 in 5-HT uptake assays in vivo

| 5-HT-positive NSMs (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pretreatment 1 | Pretreatment 2 | Genotype | |

| tph-1 | mod-5; tph-1 | ||

| — | — | 0 | 0 |

| — | 5-HT | 98 | 0 |

| 0.22 mm flx | 5-HT + 0.22 mmflx | 20 | NA |

| 0.29 mm flx | 5-HT + 0.29 mm flx | 7 | NA |

| 0.44 mmflx | 5-HT + 0.44 mm flx | 0 | NA |

In pretreatment 1, animals were incubated for 1 hr on plates containing no drug or the specified concentration of fluoxetine (flx). In pretreatment 2, animals from plates with no drug in pretreatment 1 were transferred to plates containing no drug or 2 mm 5-HT, and animals from plates with fluoxetine in pretreatment 1 were transferred to plates containing 2 mm 5-HT and the same specified concentration of fluoxetine as in pretreatment 1. After 2 hr, animals were fixed and stained with anti-5-HT antisera. (See Materials and Methods for controls included to ensure that lack of 5-HT staining did not result from a failure of the antibody staining reaction.) NA, not applicable. At least 100 animals were assayed in each condition for each genotype; >200 mod-5; tph-1 animals pretreated with 5-HT in pretreatment 2 were scored. tph-1(mg280) andmod-5(n3314) were the alleles used.

MOD-5-mediated uptake in mammalian cells. We obtained a modified version of the MSCVpac vector (Hawley et al., 1994) in which the pac gene had been replaced with the gfp gene [green fluorescent protein (GFP) vector; a generous gift from J. Schwartz, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA]. We further modified the GFP vector as follows. The ends of a BglII–Mfe I fragment containing the entiremod-5 cDNA were blunted using the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I and then ligated to the GFP vector digested withHpaI, placing mod-5 under the control of the retroviral long terminal repeat promoter (GFPMOD-5). The Phoenix packaging cell line (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) was used to generate a virus containing either GFPMOD-5 or GFP vector. Human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cells were infected with these viral stocks in the presence of 4 mg/ml polybrene, and clones expressing high levels of GFP were isolated using a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACstar or FACSvantage; Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA). The GFPMOD-5 clones were then screened for MOD-5 C. elegans SERT (CeSERT)-mediated [3H]5-HT uptake activity, and one clone was chosen for use in all further uptake experiments. Cells were plated at 106 cells per well of a six-well dish and allowed to grow overnight before being assayed. Cells were incubated in prewarmed wash buffer (120 mm NaCl, 10 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, 4.7 mmKCl, 2.2 mm CaCl2, 1.2 mmKH2PO4, 1.2 mm MgSO4, 1.8 mg/ml glucose, 100 μm pargyline, and 100 μm ascorbic acid) for 10 min at 37°C, and the buffer was then replaced with prewarmed wash buffer plus substrate. In Figure 4B, the NaCl was substituted with an equivalent amount of sodium gluconate or choline chloride. Except for the trials shown in Figure 4, C and D, 50 nm [3H]5-HT (specific activity, 24 Ci/mmol; New England Nuclear, Boston, MA) was used as a substrate (there was no dilution with nonradioactive substrate in these experiments). For the trials shown in Figure 4,C and D, radiolabeled substrates were diluted with nonradioactive substrate to maintain a specific activity of 0.1 Ci/mmol. Uptake was allowed to proceed at 37°C for varying times for the time course and for 10 min in all other experiments. Cells were then washed three times with ice-cold wash buffer and solubilized in 1% SDS, and the radioactivity retained in the cells was determined by liquid scintillation. Cell numbers, quantified in parallel wells taken through all steps of the assay, were used to convert counts per minute to nmoles per cell per minute. The specific uptake of each substrate for each condition was obtained by subtracting the average value obtained from at least three trials with the GFP vector cell line from the average value obtained from at least six trials with the GFPMOD-5 cell line. Inhibitor Ki values were determined from concentration-versus-uptake profiles after adjustment for substrate concentrations (Cheng and Prusoff, 1973). Statistical significance was evaluated using Student's t test (Statview).

Fig. 4.

Physiological characterization of MOD-5 CeSERT. Experiments were performed using HEK293 cell lines stably transfected with either a mod-5:: gfp(GFPMOD-5) or a gfp control (GFP vector) construct (for details, see Materials and Methods). Results indicate mean ± SEM from at least six replicate trials with a MOD-5 CeSERT-expressing cell line after subtracting the nonspecific 5-HT uptake from at least three replicate trials with a cell line expressing GFP from the parent vector lacking mod-5. Except in A, all assays were performed for 10 min. In A, B, 50 nm[3H]5-HT was used. In C, D, the radiolabeled neurotransmitters were present at 0.1 Ci/mmol specific activity. Error bars indicate SEM. A, Time dependence of MOD-5 CeSERT-mediated [3H]5-HT transport.Circles, GFPMOD-5; squares, GFP vector.B, Dependence of MOD-5 CeSERT-mediated [3H]5-HT transport on Na+ and Cl− ions in the external buffer. Results are shown as a percentage of the normalized 5-HT uptake in standard NaCl-containing buffer. Transport is strictly dependent on Na+ but only partially dependent on Cl−. C, MOD-5 CeSERT-mediated [3H]5-HT transport as a function of 5-HT concentration. [3H]5-HT uptake was measured at various 5-HT concentrations. Inset, Eadie–Hoftsee transformation (Stryer, 1995) of the data.Km, 150 ± 8 nm;Vmax, 8.31 × 10−9nmol · cell−1 · min−1. This Vmax value cannot be compared in a meaningful way with values from other studies in the absence of information about relative SERT levels on the cell membrane.D, MOD-5 CeSERT-mediated transport was specific for [3H]5-HT. Assays were performed with 1 μm [3H]5-HT and a 50 μm concentration of each of the other radiolabeled neurotransmitters, and the results are presented as a percentage of normalized 1 μm [3H]5-HT uptake. There was no detectable transport when neurotransmitters other than 5-HT were added at 1 μm (data not shown).E, Antagonism of MOD-5 CeSERT-mediated 5-HT uptake. Inhibition curves for SSRIs and other transporter inhibitors are shown. Assays were performed for 10 min with 50 nm[3H]5-HT in the presence of varying concentrations of each of the compounds. The extent of [3H]5-HT uptake is plotted as the percentage of [3H]5-HT uptake observed in the absence of antagonists versus log[inhibitor]. See Results for Ki values calculated from these data.

RESULTS

Isolation of mutants defective in 5-HT uptake

FIF histochemistry indicates that the C. elegans NSMs, located in the pharynx, contain 5-HT in their cell bodies and axonal processes (Horvitz et al., 1982). FIF in the NSMs was more readily observed when animals were preincubated with exogenous 5-HT before the staining protocol (Horvitz et al., 1982; our unpublished results). This observation suggested that the NSMs possess an active uptake system that can concentrate 5-HT from the extracellular environment.

We performed a genetic screen for mutants lacking FIF in the NSMs after preincubation with exogenous 5-HT (see Materials and Methods). Two mutations that failed to complement each other, n822 andn823, were isolated. n822 and n823mutants lacked FIF in the NSM cell bodies after 5-HT preincubation but retained FIF in the NSM axonal processes (Fig.1A). Nomarski optics (Ellis and Horvitz, 1986) revealed that these mutants had NSM cell bodies in their usual positions (data not shown).

5-HT can also be detected in C. elegans using anti-5-HT antisera, which have proven to be more sensitive than FIF and have allowed the reliable detection of endogenous 5-HT in the NSMs and other neurons without requiring preincubation with exogenous 5-HT (Desai et al., 1988; Loer and Kenyon, 1993; Sawin et al., 2000). We used anti-5-HT antisera to evaluate 5-HT reuptake in n822 andn823 mutants. Because endogenous 5-HT masks 5-HT reuptake in NSMs visualized using anti-5-HT antisera, we used acat-4(e1141) (catecholamine-defective) genetic background to reduce endogenous 5-HT levels (Desai et al., 1988; Weinshenker et al., 1995). cat-4 encodes GTP cyclohydrolase I (C. Loer, personal communication), which is required for the synthesis of a biopterin cofactor needed for dopamine and 5-HT biosynthesis (Kapatos et al., 1999).

We counted the number of immunoreactive NSMs in cat-4 single and n822; cat-4 and n823; cat-4 double mutants with or without exogenous 5-HT preincubation. Although NSMs in thecat-4 mutants were capable of 5-HT uptake, the NSMs in then822; cat-4 and n823; cat-4 double mutants were partially defective in 5-HT uptake (Fig. 1B), confirming our FIF observations. For example, we observed no brightly fluorescing NSMs in n823; cat-4 mutants preincubated with 5-HT, whereas 43% of the NSMs in cat-4 mutants had bright immunofluorescence (Fig. 1B, black bars). That a slight increase in NSM immunoreactivity was observed inn822; cat-4 and n823; cat-4 mutants after 5-HT preincubation suggests that the n822 and n823mutations do not lead to a complete loss of 5-HT uptake activity. Although previous studies did not detect anti-5-HT immunoreactivity incat-4 mutants (Desai et al., 1988; Loer and Kenyon, 1993;Weinshenker et al., 1995), we observed, using the same staining protocol as in the previous studies, a small percentage of weakly anti-5-HT-immunoreactive NSMs in cat-4 mutants in the absence of 5-HT preincubation (Fig. 1B). This staining is 5-HT, because this antibody did not result in any immunoreactivity in tph-1 mutants (see below), which lack the 5-HT biosynthetic enzyme tryptophan hydroxylase and are specifically deficient in 5-HT (Sze et al., 2000). Our data suggest that the cat-4 mutation does not lead to a complete loss of 5-HT, consistent with the conclusions of Desai et al. (1988) and Avery and Horvitz (1990).

5-HT-uptake mutants exhibit a hyperenhanced slowing response

Because n822 and n823 mutants were defective in 5-HT uptake, we sought to determine whether these mutants were abnormal in their responses to endogenous 5-HT release. We tested the 5-HT-dependent enhanced slowing response (Sawin et al., 2000) of these mutants. Whereas well-fed wild-type animals slow their locomotory rate slightly in response to bacteria (the basal slowing response), food-deprived wild-type animals display a greater degree of slowing of locomotory rate in response to bacteria (the enhanced slowing response;Sawin et al., 2000) (Fig.2A). Strikingly,n822 and n823 mutants exhibited a hyperenhanced slowing response: on Petri plates with bacteria, the locomotory rates of food-deprived n822 and n823 mutants slowed significantly more than did those of food-deprived wild-type animals (Fig. 2A, gray bars). On Petri plates without bacteria, the locomotory rates of food-deprived n822and n823 mutants were not significantly different from those of food-deprived wild-type animals (Fig. 2A,gray bars). Well-fed n822 and n823mutants exhibited no defect in the 5-HT-independent dopamine-dependent basal slowing response to bacteria (Fig. 2A,black bars) (Sawin et al., 2000). Genes involved in the enhanced slowing response are called mod (modulation of locomotion defective; Sawin et al., 2000), and we named the gene defined by the allelic mutations n822 and n823 mod-5. The hyperenhanced slowing responses of thesemod-5 mutants were presumably a consequence of a defect in the clearing of 5-HT from the relevant synapses by uptake into serotonergic neurons, thereby leading to increased 5-HT signaling and a greater inhibition of locomotion.

Fig. 2.

Phenotypic characterization ofmod-5. A, mod-5 mutants exhibited a hyperenhanced slowing response. Well-fed (black bars) and food-deprived (gray bars) animals were transferred to assay plates with or without a bacterial lawn, and the locomotory rate of each animal was recorded after 5 min; food-deprived animals were transferred to plates without bacteria 30 min before the transfer to locomotory assay plates (for details, seeSawin et al., 2000). At least 10 trials were performed for each genotype for each condition. For this and all subsequent panels, each trial involved testing at least five animals for each of the conditions; a given animal was tested in only one condition.p values were calculated by comparing the combined data for the mutants from all of the separate trials under one set of conditions to the combined data for the wild-type animals assayed in parallel under the same conditions. B, The hyperenhanced slowing response exhibited by mod-5(n823) mutants was suppressed by ablation of the NSMs. Number of animals tested: three of each ablation state when well-fed; seven mock-ablated, food-deprived; and 12 NSM-ablated, food-deprived. C, A decrease in endogenous 5-HT partially suppressed the mod-5phenotype. mod-5(n823); cat-4 double mutants displayed an enhanced slowing response intermediate to that ofmod-5(n823) (see A) andcat-4 mutants. D, mod-5mutants were hypersensitive to exogenous 5-HT. 5-HT dose–response curves for wild-type and mod-5 mutant animals were generated from averages of five trials with 20 animals of each genotype at each concentration in which animals were scored for movement after 5 min. Error bars indicate SEM. ***p< 0.0001, Student's t test.

Ablation of the serotonergic NSMs or decrease in endogenous 5-HT suppresses mod-5 mutations

Ablation of the serotonergic NSMs with a laser microbeam leads to a defect in the enhanced slowing response (Sawin et al., 2000). Because the NSMs were defective in 5-HT uptake in mod-5 mutants (see above), we tested whether ablation of the NSMs affected the hyperenhanced slowing response of mod-5 mutants. On Petri plates with bacteria, food-deprived NSM-ablated mod-5(n823)mutants exhibited an enhanced slowing response that was significantly reduced in comparison with that of food-deprived, mock-ablatedmod-5(n823) mutants (Fig. 2B, gray bars). Well-fed NSM-ablated mod-5(n823) mutants were not significantly affected in their basal slowing response to bacteria (Fig. 2B, black bars). Ablation of the I5 neuron, another pharyngeal neuron, had no effect on the enhanced slowing response of mod-5 mutants (data not shown), indicating that the effect of the NSM ablations was not a consequence of the ablation protocol per se.

We reasoned that the ablation of the NSMs probably led to a loss of 5-HT needed for the hyperenhanced slowing exhibited by mod-5mutants. To test this hypothesis, we determined whether thecat-4 mutation, which decreases 5-HT levels (see above), could suppress the mod-5 phenotype. cat-4 mutants are defective in the enhanced slowing response (Sawin et al., 2000) (Fig. 2C), and the reduced 5-HT in these mutants is the cause of this defect (Sawin et al., 2000).

On Petri plates with bacteria, the locomotory rate of food-deprived mod-5(n823); cat-4 double mutants was significantly faster than that of food-deprived mod-5(n823)mutants (Fig. 2, compare C, A, gray bars) but similar to that of NSM-ablated mod-5(n823)mutants (Fig. 2B), suggesting that for the enhanced slowing response the ablation of the NSMs is equivalent to a reduction in 5-HT levels in the animal. That the locomotory rate of food-deprivedmod-5(n823); cat-4 double mutants was significantly slower than that of cat-4 mutants (Fig. 2C) is likely a consequence of the effect of residual 5-HT in cat-4 mutants (Fig. 1B).

We propose that when food-deprived mod-5 mutants encounter bacteria, the NSMs release 5-HT, and this 5-HT is inefficiently cleared, thus causing the hyperenhanced slowing response.

mod-5 mutants are hypersensitive to exogenous 5-HT

Exogenous 5-HT inhibits wild-type C. elegans locomotion (Horvitz et al., 1982). To determine whether mod-5(n822) andmod-5(n823) mutants were abnormal in their response to exogenous 5-HT, we used a liquid swimming assay (Ranganathan et al., 2000). In this assay, mod-5(n822) and mod-5(n823)mutants were hypersensitive to exogenously added 5-HT (Fig.2D), presumably because this 5-HT was not efficiently cleared from the relevant synapses.

MOD-5 is similar to SERTs

We used the 5-HT hypersensitivity of mod-5 mutants in the liquid swimming assay to map and clone the gene. We mappedmod-5 to a ∼2.0 map unit interval on chromosome I, betweenfog-1 and unc-11 (Fig.3A) (see Materials and Methods). We noted an open reading frame, Y54E10BR.b (GenBank accession number AC024812), in this region predicted to encode a protein with similarity to serotonin reuptake transporters (SERTs). Because loss of SERT function would provide a simple explanation for both the defective 5-HT uptake and 5-HT hypersensitivity of mod-5 mutants, we decided to determine whether Y54E10BR.b was mod-5.

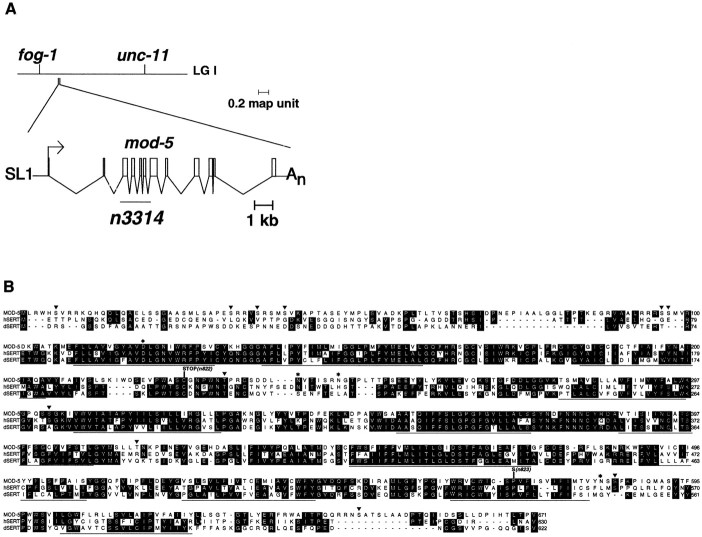

Fig. 3.

mod-5 encodes a protein similar to the human and Drosophila 5-HT reuptake transporters.A, Top, Genetic map of themod-5 region of LG I. Bottom, Intron–exon structure of mod-5 (Y54E10BR.b), inferred from cDNA sequences. Open boxes, Coding regions;lines, untranslated regions, arrow, direction of transcription; SL1, SL1trans-spliced leader. The mod-5 open reading frame is 2016 bp within a 2594 bp cDNA. The extent of the 1688 bp n3314 deletion is depicted. B, Amino acid sequence alignment of MOD-5 CeSERT with hSERT and dSERT. The 12 predicted transmembrane regions are underlined. Amino acids conserved between MOD-5 and at least one of the two other proteins are shown in black boxes, and the twomod-5 point mutations are indicated.mod-5(n822) is a Thr-to-Ala transversion mutation resulting in a C225opal nonsense substitution, andmod-5(n823) is a Cys-to-Thr transition mutation resulting in a P569S missense substitution. Triangles, Potential PKA or PKC phosphorylation sites. Such sites have been implicated in SERT membrane distribution (Qian et al., 1997;Ramamoorthy et al., 1998a) and the rate of 5-HT transport (Miller and Hoffman, 1994). *Potential N-linked glycosylation sites (consensus NXS/T). Such sites have been implicated in proper folding and insertion of SERTs into the membrane, protection from degradation, or both (Tate and Blakely, 1994; Ramamoorthy et al., 1998b). Diamond, The aspartate residue conserved in SERTs, norepinephrine transporters, and dopamine transporters.

We generated an 8 kb PCR product from the genomic region spanning the first eight exons of Y54E10BR.b (Fig. 3A) and encoding the first 507 amino acids of the corresponding predicted protein. This construct rescued the 5-HT hypersensitivity phenotype ofmod-5(n823) mutants in 16 of 20 transgenic lines tested [0–50% animals immobilized after 5 min in 10 mm 5-HT, contrasted with 100%mod-5(n823) mutants immobilized under the same conditions; data not shown; Fig. 2D], suggesting that not all 671 amino acids of MOD-5 are essential for at least some aspects of SERT function.

We obtained a partial cDNA clone of Y54E10ABR.b using RT-PCR and determined the 5′ and 3′ ends of the cDNA using 5′- and 3′-RACE, respectively. The 5′ end of the cDNA contained an SL1trans-spliced leader, which is found at the 5′ ends of manyC. elegans transcripts (Krause and Hirsh, 1987). The 3′ end contained a poly(A) stretch, indicating that we had determined the complete Y54E10BR.b transcriptional unit (Fig. 3A). This cDNA was capable of rescuing the 5-HT hypersensitivity ofmod-5 mutants (see below).

Protein sequence comparisons revealed that the predicted protein encoded by our full-length cDNA is 44% identical to human SERT (hSERT;Ramamoorthy et al., 1993) and 45% identical to the other known invertebrate SERT, from D. melanogaster (dSERT; Corey et al., 1994), which is itself 51% identical to hSERT (Fig.3B). We identified single-base mutations in the Y54E10BR.b coding sequence in mod-5(n822) and mod-5(n823)mutants (Fig. 3B). The mutation in mod-5(n822) is predicted to change cysteine 225 (codon TGT) to an opal stop codon (TGA). The mutation in mod-5(n823) is predicted to change proline 569 (CCG) to serine (TCG) within a transmembrane region. We concluded that Y54E10BR.b is mod-5.

Like SERTs from other species (Barker and Blakely, 1998, and references therein), the MOD-5 protein is predicted to contain 12 putative transmembrane regions (Fig. 3B). Much of the sequence conservation is clustered in or around these transmembrane regions, suggesting that the membrane topology of the SERTs is important for their function. At position 119 (Fig. 3B,diamond) within the first predicted transmembrane domain, MOD-5 has an aspartate residue that is conserved in 5-HT, dopamine, and norepinephrine (NE) reuptake transporters but not in γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) reuptake transporters (Barker and Blakely, 1998). This aspartate may be involved in binding to the amino group in 5-HT, dopamine, and NE (Kitayama et al., 1992; Barker et al., 1999). At position 116, MOD-5 has a phenylalanine residue that is conserved in hSERT and participates in ligand binding (Adkins et al., 2001). MOD-5 also has other similarities to hSERT and dSERT (Fig. 3B, legend).

mod-5(n3314) is a null allele

To determine the phenotypic consequence of completely eliminatingmod-5 function, we screened libraries of mutagenized animals using PCR to identify large deletions (Jansen et al., 1997) in themod-5 genomic locus. We isolated a deletion allele,n3314, that contains a 1688-bp deletion in themod-5 genomic locus (Fig. 3A). The altered open reading frame (ORF) is predicted to encode the first 42 amino acids of MOD-5 and, if the end of exon 2 splices onto the next available splice acceptor site at the start of exon 8, an additional 18 out-of-frame amino acids before ending at a premature stop codon.

n3314 mutants displayed both the hyperenhanced slowing response and 5-HT hypersensitivity in the liquid swimming assay (Fig.2A,D), and the n3314 mutation failed to complement the mod-5(n822) and mod-5(n823)alleles for both of these behaviors (data not shown), confirming thatn3314 is an allele of mod-5. mod-5(n3314) mutants were more hypersensitive to 5-HT than were mod-5(n822) and mod-5(n823) mutants (Fig.2D). mod-5(n3314) mutants also exhibited a more severe hyperenhanced slowing response than did the nonsensemod-5(n822) and the missense mod-5(n823) mutants (Fig. 2A). On Petri plates without bacteria, the locomotory rate of mod-5(n3314) mutants was not different from that of the wild type (Fig. 2A). Well-fedmod-5(n3314) mutants showed no defect in their basal slowing response to bacteria (Fig. 2A). Given the stronger behavioral defects of mod-5(n3314) mutants and the molecular nature of the n3314 deletion, we think that n3314is a null allele of mod-5 and that bothmod-5(n822) and mod-5(n823) are partial loss-of-function alleles. mod-5(n822), which is predicted to encode only the first 224 amino acids of MOD-5, is not a null allele, based on comparisons of the phenotypes of mod-5(n822),mod-5(n3314), and mod-5(n822)/mod-5(n3314) trans-heterozygous animals (Fig. 2A,D; data not shown). This activity of mod-5(n822) might be a consequence of the presence of functional mod-5 transcripts produced by alternative splicing or read-through of the stop codon. Alternatively, it is conceivable that the first 225 amino acids of MOD-5 retain partial SERT function. This latter possibility is consistent with our rescue of the 5-HT hypersensitivity of mod-5(n823) mutants with a construct that encodes only the first 507 amino acids of MOD-5.

Because we had isolated the mod-5 cDNA using RT-PCR and RACE, we sought to confirm that the protein encoded by this cDNA could function in vivo. We constructed a mini-gene in which themod-5 cDNA was placed under the control of 2.7 kb of genomic DNA upstream to the first predicted methionine of mod-5. mod-5(n3314) animals transgenic for extrachromosomal arrays consisting of this minigene construct were no longer 5-HT-hypersensitive (data not shown), confirming that we had defined a functional mod-5 gene and that the mod-5 cDNA could encode a functional SERT and was suitable for 5-HT-uptake assays in a heterologous system (see below).

MOD-5 functions as a SERT in mammalian cells

Using retroviral-mediated gene transfer (see Materials and Methods), we generated HEK293 cell lines that stably expressed MOD-5. Using these cell lines, we performed uptake assays similar to those previously done for other SERTs (Ramamoorthy et al., 1993; Demchyshyn et al., 1994). The uptake of [3H]5-HT by MOD-5-expressing cell lines was saturable, indicating that the accumulation of [3H]5-HT in the cells was facilitated by MOD-5 (Fig.4A). MOD-5-mediated [3H]5-HT transport was strictly dependent on Na+ ions (Fig.4B), as has been observed for 5-HT transport by hSERT (Ramamoorthy et al., 1993), rat SERT (rSERT; Blakely et al., 1991;Hoffman et al., 1991), and dSERT (Demchyshyn et al., 1994). By contrast, MOD-5 did not display a strict dependence on Cl− ions (Fig. 4B), whereas both hSERT and rSERT, but not dSERT, did display such strict dependence (Blakely et al., 1991; Hoffman et al., 1991; Ramamoorthy et al., 1993; Demchyshyn et al., 1994).

MOD-5-mediated [3H]5-HT transport occurred in a concentration-dependent and saturable manner (Fig.4C), with a Km of 150 ± 8 nm, a value similar to those reported for other SERTs (Km range, 280–630 nm; Blakely et al., 1991; Hoffman et al., 1991;Ramamoorthy et al., 1993; Corey et al., 1994; Demchyshyn et al., 1994;Chang et al., 1996; Padbury et al., 1997; Chen et al., 1998; Mortensen et al., 1999).

We tested the specificity of MOD-5 by assaying the ability of MOD-5 to transport various radiolabeled neurotransmitters besides 5-HT. MOD-5-mediated uptake was highly specific for [3H]5-HT and inefficient at translocating radiolabeled GABA, glutamate, glycine, NE, histamine, and dopamine (Fig. 4D). We also tested the ability of these neurotransmitters to inhibit [3H]5-HT uptake via MOD-5. None of the six neurotransmitters tested, even when present at 100 μm, substantially inhibited the uptake of 50 nm 5-HT. Specifically, the extent of [3H]5-HT uptake in the presence of a 100 μm concentration of each neurotransmitter was as follows: GABA, 104 ± 17% of control; glutamate, 92 ± 12%; glycine, 107 ± 18%; NE, 122 ± 15%; histamine, 107 ± 15%; and dopamine, 118 ± 15%. We also tested whether octopamine or tyramine, two invertebrate-specific neurotransmitters, could inhibit [3H]5-HT transport; we could not test MOD-5-mediated uptake of these neurotransmitters, because radiolabeled octopamine and tyramine are not available. Tyramine (100 μm) partially inhibited (54 ± 10% of control) the transport of [3H]5-HT (50 nm) by MOD-5; octopamine (100 μm) did not inhibit (86 ± 12% of control) MOD-5-mediated [3H]5-HT (50 nm) transport. By comparison, dSERT-mediated transport of 100 nm[3H]5-HT was reduced to 95 ± 15% of control by 200 μm tyramine and to 82 ± 15% of control by 200 μm octopamine (Corey et al., 1994). These data suggest that there are subtle differences in the properties of MOD-5 and dSERT.

We tested whether MOD-5-mediated [3H]5-HT transport was inhibited by tricyclic antidepressants, SSRIs, and nonspecific monoamine transporter inhibitors (Blakely et al., 1991; Ramamoorthy et al., 1993; Demchyshyn et al., 1994). The rank order of potency for inhibition of MOD-5-mediated [3H]5-HT transport was imipramine (Ki, 89 ± 58 nm) ∼ fluoxetine (Ki, 133 ± 90 nm) ∼ paroxetine (Ki, 179 ± 64 nm) > desipramine (Ki, 334 ± 115 nm) > citalopram (Ki, 994 ± 298 nm) ≫ cocaine (Ki, 4076 ± 349 nm) (Fig. 4E). This rank order is different from that of other SERTs (for example, the rank order of potency for inhibition of hSERT-mediated [3H]5-HT transport is paroxetine > fluoxetine > imipramine ∼ citalopram ≫ cocaine;Ramamoorthy et al., 1993), and for some of the inhibitors theKi values were higher than those reported for the other SERTs (Blakely et al., 1991; Hoffman et al., 1991;Ramamoorthy et al., 1993; Corey et al., 1994; Demchyshyn et al., 1994;Chang et al., 1996; Padbury et al., 1997; Chen et al., 1998; Mortensen et al., 1999).

Taken together, the specificity of MOD-5-mediated transport for 5-HT, the dependence of such transport on Na+and Cl− ions, and the inhibition of 5-HT transport by SSRIs establish that MOD-5 is a SERT from C. elegans, CeSERT.

MOD-5 is likely the only SERT in C. elegans

To determine whether MOD-5 is the only SERT in C. elegans, we analyzed the C. elegans genomic sequence for other potential SERTs and performed in vivo assays of 5-HT uptake in mod-5 mutants. We found 15 Na+/Cl−-dependent neurotransmitter transporter-like predicted ORFs in the completedC. elegans genomic sequence (C. elegansSequencing Consortium, 1998). Only two of these ORFs, T23G5.5 and T03F7.1, are nearly as similar (43 and 41% identity, respectively) to hSERT, as is MOD-5 CeSERT, and only MOD-5 CeSERT and T23G5.5 have an aspartate corresponding to aspartate 119 in MOD-5 CeSERT, a conserved residue likely to be functionally important for amine transport (see above). T23G5.5 is a dopamine reuptake transporter and is very inefficient at transporting 5-HT (Jayanthi et al., 1998). Hence, from sequence analysis, it appeared likely that MOD-5 CeSERT is the only SERT in C. elegans. This finding is consistent with the observation that to date only one SERT gene per species has been identified.

If there existed a second SERT in C. elegans, serotonergic neurons in mod-5(n3314) mutants might be able to take up exogenously added 5-HT. It is also conceivable that nonserotonergic cells possess SERT activity. We tested both these possibilities using anti-5-HT antisera to detect the uptake of 5-HT. To eliminate endogenous 5-HT, we used the tph-1(mg280) mutant, which contains a deletion in the tryptophan hydroxylase gene and is hence defective in an enzyme essential for 5-HT biosynthesis (Sze et al., 2000). tph-1 mutants completely lack anti-5-HT immunofluorescence (Sze et al., 2000). We have confirmed these findings (Table 1) using the same anti-5-HT antibodies used in Figure1B. tph-1 mutants are unlikely to be perturbed in the levels of other biogenic amines, because tryptophan hydroxylase functions in only 5-HT biosynthesis (Cooper et al., 1996;Sze et al., 2000).

To identify cells capable of 5-HT uptake, we examined the head, ventral cord, gut, and tail of tph-1 mutants pretreated with 5-HT and observed 5-HT immunofluorescence in only the serotonergic neurons (see below; data not shown). To examine more carefully the requirement of MOD-5 CeSERT for 5-HT uptake by serotonergic neurons, we scored the NSMs for 5-HT uptake, because these neurons are the most brightly staining serotonergic neurons in the animal after incubation with exogenous 5-HT. Without 5-HT pretreatment, both tph-1 single and mod-5(n3314); tph-1 double mutants had no NSMs that were 5-HT-positive (Table 1). By contrast, when pretreated with 5-HT,tph-1 mutants displayed robust 5-HT staining in the NSMs, whereas mod-5(n3314); tph-1 double mutants showed none (Table 1). We observed similar results for the serotonergic ADF neurons in the head and for the hermaphrodite-specific neurons (HSNs) in the midbody (data not shown). Thus, no other transporter appeared to transport 5-HT into serotonergic neurons in the absence of the MOD-5 CeSERT. We also examined the head, ventral cord, gut, and tail ofmod-5(n3314); tph-1 double mutants pretreated with 5-HT and observed no 5-HT immunofluorescence anywhere in the animal (data not shown), indicating that no other cells display 5-HT uptake activity in the absence of MOD-5 CeSERT.

These 5-HT uptake experiments, taken together with the analysis of theC. elegans genomic sequence, suggest that MOD-5 is the only SERT in C. elegans.

mod-5 interacts genetically with mod-1and goa-1

Mutants defective in the 5-HT-mediated enhanced slowing response defined several mod genes (Sawin et al., 2000). One of these genes, mod-1, encodes a novel ionotropic 5-HT receptor, a 5-HT-gated chloride channel (Ranganathan et al., 2000). On Petri plates with bacteria, the locomotory rate of food-deprived mod-1mutants is substantially faster than that of the wild type (Ranganathan et al., 2000; Sawin et al., 2000) (Fig.5A, gray bars). By contrast, mod-5 mutants exhibit a hyperenhanced slowing response (Fig. 5A).

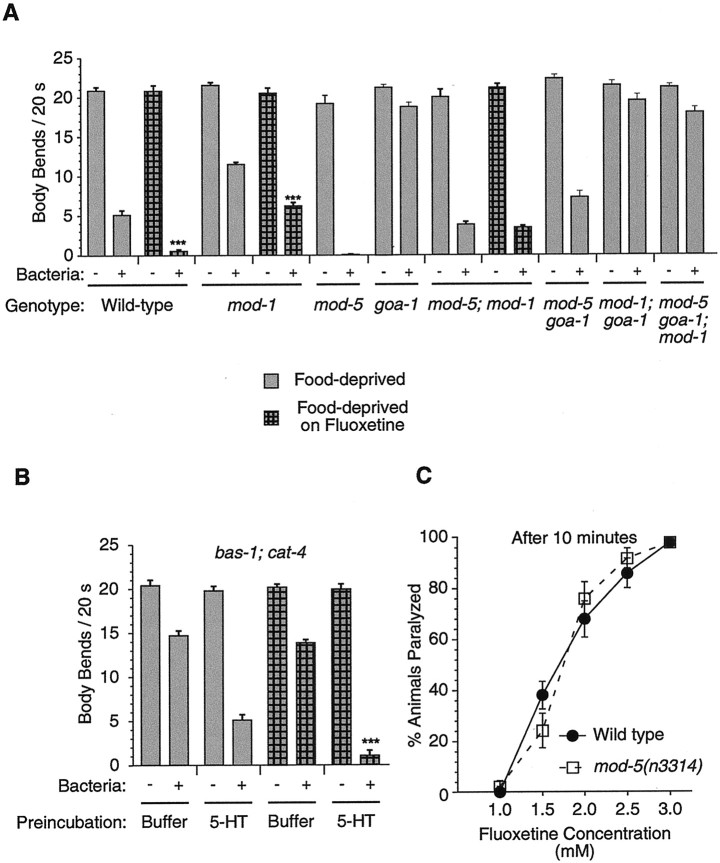

Fig. 5.

mod-5 genetic interactions and 5-HT and MOD-5 CeSERT dependence of the potentiating effect of fluoxetine.A, Gray bars, Enhanced slowing response of mod-1, goa-1, mod-5 goa-1, goa-1; mod-1, mod-5; mod-1, and mod-5 goa-1; mod-1 mutants. At least five trials were performed for each genotype. Hatched bars, Effect of fluoxetine on the enhanced slowing response of wild-type animals (data reproduced from Sawin et al., 2000) andmod-1 and mod-5; mod-1 mutants (at least 10 trials for each genotype). B, Rescue by 5-HT preincubation (see Materials and Methods) of the resistance ofbas-1; cat-4 mutants to the potentiating effect of fluoxetine on the enhanced slowing response. At least five trials were performed with each genotype. C,mod-5(n3314) mutants retained normal sensitivity to fluoxetine-mediated paralysis. Five trials with 20 animals of each genotype at each concentration were conducted, and the animals were scored for paralysis after 10 min. Error bars indicate SEM. ***p < 0.0001, Student's ttest.

To define the genetic pathway in which mod-1 andmod-5 act in the enhanced slowing response, we characterizedmod-5(n3314); mod-1(ok103) double mutants.mod-1(ok103) is a null allele by genetic and molecular criteria (Ranganathan et al., 2000). If the function of the MOD-1 5-HT receptor were essential for the effects of 5-HT not cleared from synapses in mod-5 mutants, then eliminating mod-5function should have had no effect in a mutant that lackedmod-1 function; i.e., mod-5(n3314); mod-1(ok103)double mutants should exhibit the same phenotype asmod-1(ok103) single mutants. However, the enhanced slowing response of mod-5(n3314); mod-1(ok103) double mutants was intermediate to the responses of mod-1(ok103) andmod-5(n3314) single mutants (Fig. 5A, gray bars). This observation suggests that the 5-HT signaling triggered by bacteria in the enhanced slowing response acts via at least two parallel 5-HT signaling pathways, a MOD-1-dependent pathway and a MOD-1-independent pathway. This observation is also consistent with the observation that mod-1(ok103) single mutants were not completely defective in the enhanced slowing response (Fig.5A).

Animals carrying mutations in the G-protein gene goa-1(Gαo, G0 protein, α subunit; Mendel et al., 1995; Segalat et al., 1995) are also defective in the enhanced slowing response (Sawin et al., 2000) (Fig.5A). Because GOA-1 animals are resistant to 5-HT in assays of locomotion (Segalat et al., 1995; our unpublished observations), pharyngeal pumping (Segalat et al., 1995), and egg laying (Mendel et al., 1995; Segalat et al., 1995), we tested whether the MOD-1-independent pathway might involve goa-1. As withmod-5; mod-1 double mutants, the enhanced slowing response of mod-5(n3314) goa-1(n1134) double mutants was intermediate to the responses of mod-5(n3314) and goa-1(n1134)single mutants (Fig. 5A, gray bars), indicating that 5-HT signaling triggered by bacteria in the enhanced slowing response does not act solely through goa-1. By contrast, food-deprived mod-5(n3314) goa-1(n1134); mod-1(ok103) triple mutants exhibited very little slowing in response to bacteria (Fig.5A). These observations suggested that MOD-1 and GOA-1 act in two parallel pathways that together mediate the response to the excess 5-HT signaling in mod-5(n3314) mutants.

Fluoxetine blocks 5-HT uptake in vivo

Because fluoxetine blocked [3H]5-HT transport in mammalian cells expressing MOD-5 CeSERT (see above), we tested whether fluoxetine could block 5-HT uptake in vivo inC. elegans (Table 1). We pretreated tph-1 mutants with fluoxetine, incubated the animals with 5-HT, and scored the number of 5-HT-positive NSMs. We observed, for example, few 5-HT-positive NSMs when tph-1 mutants were pretreated with 0.22 mm fluoxetine (Table 1), a concentration sufficient to potentiate the enhanced slowing response (see below). Furthermore, tph-1 mutants pretreated with as little as 0.44 mm fluoxetine, a concentration lower than that required for all the MOD-5 CeSERT-independent effects of fluoxetine (see below), were as defective in 5-HT uptake as were untreatedmod-5(n3314); tph-1 double mutants (Table 1). These observations suggested that fluoxetine can block 5-HT uptake inC. elegans in vivo and does so by inhibiting MOD-5 CeSERT.

The potentiation of the enhanced slowing response by fluoxetine requires MOD-5 CeSERT and 5-HT

When wild-type animals that have been food-deprived in the presence of 0.22 mm fluoxetine encounter bacteria, they slow their locomotory rate more than if they had been food-deprived in the absence of fluoxetine (Sawin et al., 2000) (Fig. 5A). This fluoxetine-mediated potentiation of the enhanced slowing response resembles the hyperenhanced slowing response exhibited bymod-5(n3314) mutants (Fig. 5A), suggesting that fluoxetine causes this potentiation by blocking MOD-5 CeSERT function. If so, mod-5(n3314) mutants should be resistant to the potentiating effect of fluoxetine on the enhanced slowing response. Because food-deprived mod-5(n3314) mutants exhibit an extreme hyperenhanced slowing response that cannot be further potentiated by fluoxetine treatment (Fig. 5A; data not shown), we used mod-5(n3314); mod-1(ok103) double mutants to test this hypothesis. These double mutants are partially suppressed for the hyperenhanced slowing response exhibited by mod-5(n3314)animals (Fig. 5A, gray bars); therefore, a potentiation of the enhanced slowing response could be observed.

The enhanced slowing response of mod-1(ok103) mutants was potentiated by fluoxetine (Fig. 5A, hatched bars), indicating that fluoxetine can potentiate the enhanced slowing response in the absence of MOD-1 5-HT receptor function. This observation was consistent with the phenotype of mod-5(n3314); mod-1(ok103) double mutants in this assay, which suggested that there are MOD-1-independent 5-HT pathways through which the enhanced slowing response is effected. By contrast, mod-5(n3314); mod-1(ok103) double mutants were completely resistant to the potentiating effect of fluoxetine on the enhanced slowing response (Fig. 5A, hatched bars). Therefore, the MOD-5 CeSERT is likely the only in vivo target in C. elegans on which fluoxetine acts to potentiate the enhanced slowing response.

Because fluoxetine-mediated potentiation of the enhanced slowing response is MOD-5 CeSERT-dependent, it is also likely to be 5-HT-dependent, as we previously suggested (Sawin et al., 2000) on the basis of the observation that the enhanced slowing response ofbas-1(ad446); cat-4 double mutants (bas, biogenic amine synthesis-defective) is resistant to such potentiation. However, our studies of egg laying by tph-1 mutants suggest that the resistance of cat-4 animals to the effects of high concentrations of fluoxetine is likely not to be caused by a deficiency in 5-HT in these animals (see below). Because tph-1 mutants display sluggish locomotion (data not shown), they could not be assayed for resistance to the fluoxetine-mediated potentiation of the enhanced slowing response.

We sought to determine whether it is the 5-HT-deficiency ofbas-1; cat-4 double mutants that renders these animals resistant to the potentiating effect of fluoxetine. The defect in the enhanced slowing response of bas-1; cat-4 double mutants in the absence of fluoxetine treatment can be rescued by preincubating the animals on Petri plates containing 2 mm 5-HT (Sawin et al., 2000) (Fig. 5B), a pretreatment sufficient for the detection of 5-HT in the NSMs of cat-4 (Fig.1B) and tph-1 (Table 1) mutants. Whenbas-1; cat-4 mutants were preincubated with 5-HT and then food-deprived in the presence of fluoxetine, they exhibited a potentiated enhanced slowing response (Fig. 5B). Therefore, restoration of 5-HT to bas-1; cat-4 mutants is sufficient for fluoxetine to potentiate the enhanced slowing response of these mutants. We conclude that the effect of fluoxetine on the enhanced slowing response is dependent not only on MOD-5 CeSERT but also on 5-HT.

Fluoxetine induces nose contraction and paralysis inmod-5 and tph-1 mutants

Treatment of C. elegans with high concentrations (0.25–1 mg/ml, 0.7–2.9 mm) of fluoxetine leads to paralysis (Choy and Thomas, 1999), contraction of nose muscles (Choy and Thomas, 1999), and stimulation of egg laying (Weinshenker et al., 1995). The concentrations of fluoxetine required for these effects are at least 2.5-fold higher than that required to detect a block of 5-HT uptake in vivo (see above) and for the potentiation of the enhanced slowing response (Fig. 5B) (Sawin et al., 2000). If the only in vivo target for fluoxetine were MOD-5 CeSERT,mod-5 mutants would be paralyzed, have contracted noses, and display excessive egg laying. mod-5 mutants exhibit none of these characteristics (data not shown), suggesting that either MOD-5 CeSERT is not the sole target of fluoxetine in C. elegans or that an altered developmental program compensates for the animals growing up without a SERT. In the latter case, mod-5(n3314)mutants would be expected to be resistant to the effects of fluoxetine. Therefore, we tested mod-5(n3314) mutants for their responses to high concentrations of fluoxetine.

mod-5(n3314) mutants retained wild-type sensitivity to fluoxetine in assays of paralysis induced by fluoxetine treatment (Fig.5C). There was no difference in the time course of paralysis at any of the concentrations tested (data not shown). These observations suggest that fluoxetine-induced paralysis in C. elegans is not caused by the lack of 5-HT uptake from synapses. Fluoxetine-treated wild-type and mod-5(n3314) mutant animals assumed a rigid body posture (data not shown), as observed by others (Choy and Thomas, 1999). By contrast, 5-HT-treated animals assumed a relaxed and flaccid body posture (data not shown), suggesting that the mechanisms of locomotory inhibition by 5-HT and fluoxetine are distinct. 5-HT has been proposed to decrease excitatory input to the locomotory muscles (Nurrish et al., 1999). Given the two distinct body postures, we suggest that fluoxetine may directly or indirectly increase excitatory input or decrease inhibitory input to the locomotory muscles.

When treated with fluoxetine for 20 min, a similar proportion of wild-type and mod-5(n3314) mutant animals had contracted noses (100% at 2.9 mm and ∼25% at 1.5 mm). Thus, the effect of fluoxetine on nose contraction also appears to act via a MOD-5 CeSERT-independent pathway. This conclusion is consistent with the conclusion by Choy and Thomas (1999) that fluoxetine-mediated nose contraction is 5-HT-independent, although their hypothesis was based on studies ofcat-1(e1111) mutants, which are defective in signaling by several biogenic amines (Duerr et al., 1999), and cat-4mutants, which we found to not completely lack 5-HT (Fig.1B).

That the effects of high concentrations of fluoxetine on nose contraction and paralysis were independent of MOD-5 CeSERT suggested that fluoxetine acts either on another SERT or on a distinct non-SERT target(s). As discussed above, we think that MOD-5 is the only SERT inC. elegans, making it likely that a non-SERT target(s) of fluoxetine mediates the MOD-5 CeSERT-independent effects. Such non-SERT targets may or may not be part of a serotonergic signaling pathway. We decided to explore the requirement for 5-HT by testing whether fluoxetine can act in animals that lack 5-HT. The 5-HT-deficient mutants that have been used in numerous previous studies (Weinshenker et al., 1995; Choy and Thomas, 1999; Sawin et al., 2000), such ascat-1, cat-4, and bas-1 mutants, all affect multiple biogenic amines. None has been shown to cause a complete loss of 5-HT function. We therefore tested tph-1mutants, which appear to completely lack 5-HT (see above), for their response to fluoxetine.

One hundred percent of tph-1 animals displayed contracted noses after treatment with 2.9 mm fluoxetine for 20 min. These data confirm the hypothesis of Choy and Thomas (1999)that this effect of fluoxetine is 5-HT-independent. We found that fluoxetine treatment paralyzed tph-1 mutants to a similar extent as wild-type animals (data not shown), suggesting that paralysis by high concentrations of fluoxetine is also a 5-HT-independent process.

Fluoxetine stimulates egg laying in mod-5 andtph-1 mutants

In 1.5 mm fluoxetine, mod-5(n3314) mutants were stimulated to lay eggs to nearly the same extent as was the wild type (Fig. 6A,B,black bars), suggesting that fluoxetine can stimulate egg laying via one or more MOD-5 CeSERT-independent pathways. Nevertheless,mod-5(n3314) mutants were hypersensitive to exogenous 5-HT in assays of egg laying (Fig.7A,B), suggesting that MOD-5 CeSERT can affect serotonergic synapses that regulate egg laying.mod-5(n3314) mutants and wild-type animals contain similar numbers of eggs (25.7 ± 2.8 and 26.3 ± 2.2, respectively), indicating that this hypersensitivity to exogenous 5-HT was not a consequence of differences in basal egg-laying rates between wild-type animals and mod-5 mutants but rather a result of excess 5-HT signaling in mod-5(n3314) mutants.

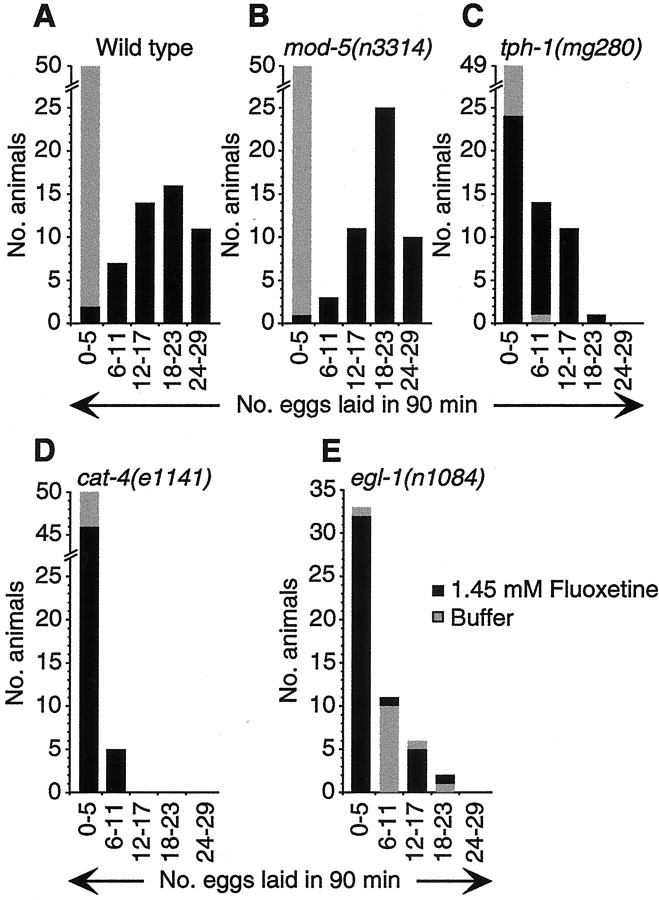

Fig. 6.

5-HT and MOD-5 CeSERT independence of fluoxetine-induced egg laying. Fluoxetine-induced egg laying:n = 50 for each genotype. A, Wild-type animals. B, mod-5(n3314)mutants. C, tph-1 mutants.D, cat-4 mutants. E,egl-1 mutants.

Fig. 7.

mod-5(n3314) mutants, but nottph-1 mutants, are hypersensitive to stimulation of egg laying by 5-HT. 5-HT-induced stimulation of egg laying:n = 50 for each genotype. A, Wild-type animals. B, mod-5(n3314)mutants. C, tph-1 mutants.

Given that the stimulation of egg laying by fluoxetine did not require the MOD-5 CeSERT, we wondered whether this stimulation required 5-HT.tph-1 mutants were partially resistant to the stimulation of egg laying by fluoxetine (Fig. 6A,C), indicating that 5-HT mediated some but not all of the egg-laying response to fluoxetine. By contrast, cat-4 mutants were completely resistant to fluoxetine-induced egg laying (Fig.6A,D), as reported by Weinshenker et al. (1995).

The reduction in egg laying by tph-1 mutants in response to fluoxetine (Fig. 6C) is unlikely to be caused by a lower number of eggs within tph-1 mutants or the inability of egg-laying muscles in tph-1 mutants to respond to stimulatory input: tph-1 mutants contain more eggs than do wild-type animals (Sze et al., 2000; and data not shown), andtph-1 mutants laid at least as many eggs in response to exogenous 5-HT as did wild-type animals (Fig. 7C). Thatmod-5(n3314) and tph-1 mutants laid significant numbers of eggs in response to fluoxetine argues that the mechanism(s) through which fluoxetine stimulates egg laying in C. elegansis not only MOD-5 CeSERT-independent but also, in part, 5-HT-independent.

The serotonergic HSN motor neurons innervate the egg-laying muscles and drive egg laying (Trent et al., 1983; Desai et al., 1988).egl-1(n1084) mutants, which lack the HSNs (Desai et al., 1988), released some eggs in the absence of fluoxetine (Fig.6E, gray bars), presumably because these animals were severely bloated with eggs. However, treatment with fluoxetine had no effect on egg laying in egl-1 mutants (Fig. 6E, black bars). These observations indicate that the HSNs are required for the stimulation of egg laying by fluoxetine.

DISCUSSION

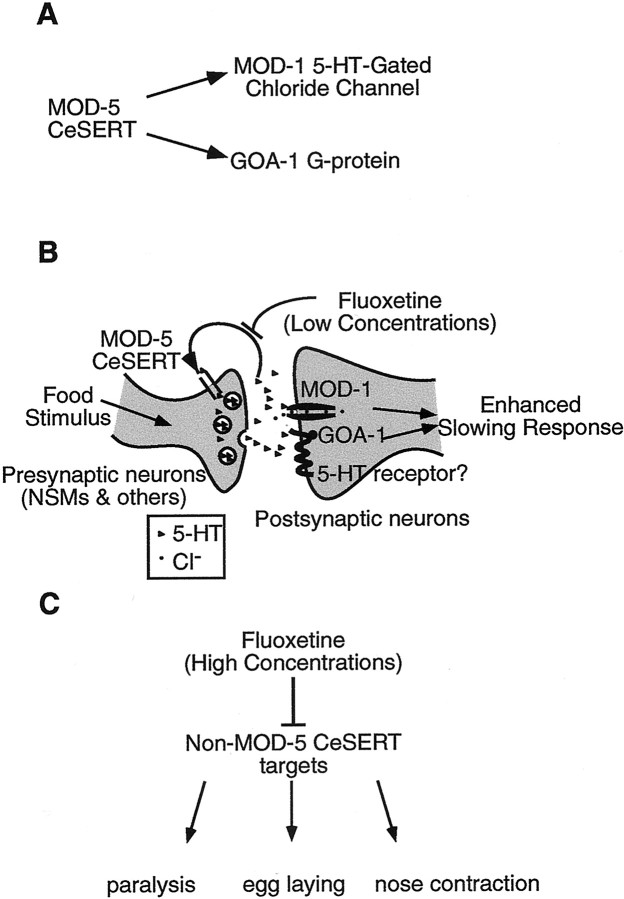

The C. elegans gene mod-5 encodes a homolog of human SERT, a protein of major importance in human neurobiology and psychiatric disease. MOD-5 CeSERT acts in a pathway that includes both a novel type of 5-HT receptor, the 5-HT-gated chloride channel MOD-1, and the G-protein GOA-1. We have identified a C. elegansmodulatory behavior (the potentiation of the enhanced slowing response) in which fluoxetine (Prozac) affects 5-HT signaling by antagonizing MOD-5 CeSERT. We have also identified C. elegans behaviors in which fluoxetine acts independently of both SERT and 5-HT. The analysis of these behaviors could define novel targets of fluoxetine action. Choy and Thomas (1999) initiated such studies, screening for mutants that fail to show the nose contraction response to fluoxetine treatment, and in this way they defined two genes required for this response.

MOD-5 probably acts upstream of MOD-1 and GOA-1

mod-5 mutants, which exhibit a hyperenhanced slowing response, are opposite in phenotype to all other modmutants, which were isolated on the basis of their failures to exhibit the enhanced slowing response (Sawin et al., 2000). These opposite phenotypes allow genetic epistasis experiments to be performed to help define a genetic pathway for this behavior.

We performed such epistasis analysis with the genes mod-1,goa-1, and mod-5 (Fig. 5A). The phenotypes of mod-5 goa-1 and mod-5; mod-1 double mutants were intermediate between those of either mod-5 orgoa-1 or mod-5 or mod-1 single mutants, respectively; mod-5 goa-1; mod-1 triple mutants were almost completely defective in the enhanced slowing response. The intermediate phenotypes of these double mutants with mod-5indicate that mod-1 and goa-1 act in parallel pathways for the enhanced slowing response (Fig.8A). mod-1and goa-1 probably both act downstream of mod-5(Fig. 8A), because in the absence of bothmod-1 and goa-1, the presence or absence ofmod-5 has little effect.

Fig. 8.

Models for the effects of fluoxetine on C. elegans behaviors. A, MOD-5 CeSERT acts upstream of the MOD-1 5-HT-gated chloride channel and the GOA-1 G-protein.B, The potentiating effect of low concentrations of fluoxetine on the enhanced slowing response is 5-HT- and MOD-5 CeSERT-dependent. The stimulus of food in a food-deprived animal results in the release of 5-HT. This 5-HT acts through the MOD-1 5-HT-gated chloride channel and through a GOA-1-dependent 5-HT signaling pathway, which likely acts in parallel to the MOD-1 pathway. Together, these two pathways result in the slowing of the locomotory rate. Mutation in mod-5 or application of fluoxetine leads to inefficient clearing of 5-HT and thus a hyperenhanced slowing response. 5-HT receptor, A metabotropic 5-HT receptor that GOA-1 might couple to. Triangles, 5-HT;circles, chloride ions. C, The effects of high concentrations of fluoxetine on egg laying, nose contraction, and paralysis are MOD-5 CeSERT-independent. High concentrations of fluoxetine act on non-SERT targets and on a non-5-HT pathway to paralyze C. elegans and to lead to the contraction of nose muscles. By contrast, stimulation of egg laying by fluoxetine is MOD-5 CeSERT-independent but still partially dependent on 5-HT (for details, see Discussion).

Because mod-5 encodes a SERT and mod-5 mutants are defective in the loading of 5-HT into serotonergic neurons, it is likely that MOD-5 CeSERT functions in neurons that synthesize and release 5-HT. That mod-1 probably acts downstream ofmod-5 and encodes a 5-HT receptor (Ranganathan et al., 2000) suggests that MOD-1 acts in cells that are postsynaptic to the serotonergic neurons in which MOD-5 functions (Fig.8B). Alternatively, MOD-1 could be a presynaptic 5-HT receptor, acting in the same serotonergic cells as MOD-5. We consider this latter possibility unlikely, given that amod-1:: GFP reporter that rescues themod-1 mutant phenotype (Ranganathan et al., 2000) is not expressed in the NSM, HSN, and ADF serotonergic neurons (R. Ranganathan and H. R. Horvitz, unpublished data). Moreover, expression of thismod-1:: GFP reporter was observed in certain nonserotonergic neurons (data not shown) that are likely to be direct postsynaptic partners of some of the serotonergic neurons (White et al., 1986). Similarly, because goa-1 mutants are resistant to the effects of exogenous 5-HT (Mendel et al., 1995, Segalat et al., 1995; our unpublished data), the functions of this G-protein required for responding to 5-HT are likely to be downstream of the serotonergic neurons in which MOD-5 functions (Fig. 8B).

The molecular features of MOD-5, MOD-1, and GOA-1 combined with our genetic epistasis analysis lead us to propose a simple model for the enhanced slowing response in which MOD-5 acts upstream of both MOD-1 and GOA-1, which in turn act in parallel to each other (Fig.8B). Although this model places MOD-1 and GOA-1 within the same cells (Fig. 8B), our data are also consistent with a model in which these proteins act in parallel in different neurons in the animal, possibly responding to distinct presynaptic serotonergic neurons.

Fluoxetine-induced egg laying is only partially 5-HT-dependent

Weinshenker et al. (1995) observed that cat-4 mutants, which are deficient in dopamine and 5-HT (see above), do not lay eggs in response to fluoxetine and suggested that fluoxetine is likely to stimulate egg laying by affecting a 5-HT signaling pathway, possibly by inhibiting a SERT. However, we found that mod-5 CeSERT null mutants were stimulated to lay eggs by fluoxetine and thattph-1 mutants, which appeared to completely lack 5-HT, were only partially resistant to fluoxetine. Thus fluoxetine can stimulate some egg laying in the absence of 5-HT. The resistance ofcat-4 mutants to fluoxetine is unlikely to be a consequence of their deficiency in dopamine (Weinshenker et al., 1995). One possibility is that the biopterin cofactor generated by the GTP cyclohydrolase I enzyme encoded by the cat-4 gene (C. Loer, personal communication) participates in the biosynthesis of small molecules in addition to dopamine and 5-HT. Consistent with this possibility, cat-4 animals have an altered cuticle (Loer and Kenyon, 1993), a characteristic not found in bas-1 mutants, which also have reduced levels of both 5-HT and dopamine (Loer and Kenyon, 1993; our unpublished results). Moreover, bas-1mutants, unlike cat-4 mutants, were not resistant to fluoxetine-induced egg laying (data not shown). Hence, the resistance of cat-4 mutants to fluoxetine-induced egg laying need not be a consequence of their deficiency in either 5-HT or dopamine.

tph-1 mutants were partially resistant to fluoxetine-induced egg laying, whereas mod-5(n3314) mutants were not at all resistant. Because we have shown that MOD-5 is likely the only SERT inC. elegans, these observations suggest that fluoxetine-mediated stimulation of egg laying through non-SERT pathways still involves 5-HT signaling. We propose that 5-HT signaling serves as a requisite permissive signal for the egg-laying circuitry to respond in full to a fluoxetine-stimulated non-5-HT signal. This model is consistent with the hypothesis that 5-HT promotes and maintains the active phase of egg laying (Waggoner et al., 1998). Alternatively, 5-HT could be required during development for the neuromusculature to be competent to respond fully to fluoxetine.

Potentiation of the enhanced slowing response by fluoxetine requires MOD-5 CeSERT and 5-HT

The therapeutic effect of fluoxetine in human patients is thought to be mediated primarily by a block in 5-HT uptake by hSERT. However, fluoxetine causes a variety of adverse side effects, including headaches, sexual dysfunction, and sleep disorders (Baldessarini, 1996). It remains important to resolve whether these side effects result from the action of fluoxetine on hSERT or from the action of fluoxetine on non-hSERT target(s).

We have shown that high concentrations of fluoxetine have effects on both mod-5 and tph-1 mutants. Our results demonstrate that in C. elegans, effects of fluoxetine previously thought to be 5-HT-dependent are MOD-5 CeSERT-independent and, to varying degrees, 5-HT-independent (Fig. 8C). It has recently been proposed, on the basis of the identification of fluoxetine-resistant mutants and the cloning of a novel family ofC. elegans transmembrane proteins required for responses to fluoxetine, that some of these side effects of fluoxetine could involve 5-HT-independent targets (Choy and Thomas, 1999; Schafer, 1999). Our demonstration in this study that there is a SERT- and 5-HT-dependent effect of fluoxetine on C. elegans behavior (Fig.8B) (the potentiation of the enhanced slowing response) strengthens the argument that non-SERT and nonserotonergic targets of fluoxetine in C. elegans could well be relevant to the effects of fluoxetine in humans. Moreover, the potentiation of the enhanced slowing response by fluoxetine requires much lower doses of fluoxetine than do the other effects of fluoxetine on C. elegans behavior, arguing that fluoxetine is likely acting on its most sensitive target, i.e., MOD-5 CeSERT, to bring about the potentiation of the enhanced slowing response. By contrast, the non-SERT targets that mediate the other effects of fluoxetine inC. elegans are likely to have either lower binding affinities or lower bioavailability for fluoxetine.

We propose that the further genetic analysis of the C. elegans behaviors elicited by fluoxetine in mod-5 andtph-1 mutants will help define SERT- and 5-HT-independent targets of fluoxetine. Such studies could be instrumental in the development of pharmaceuticals that modulate 5-HT neurotransmission with fewer side effects than those currently in use in the clinic.

Footnotes

This research was supported by United States Public Health Service Grant GM24663 (H.R.H.). E.R.S. was supported by predoctoral fellowships from the National Science Foundation and the W. M. Keck Foundation. R.R. was supported by a Howard Hughes Medical Institute predoctoral fellowship. H.R.H. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. We thank Brendan Galvin, Brad Hersh, Eric Miska, Ignacio Perez de la Cruz, Peter Reddien, and Hillel Schwartz for suggestions concerning this manuscript, Ron Ellis for directing our attention to the presence of a SERT gene in unfinished C. elegans genomic sequence, Subbu Apparsundaram for guidance concerning the SERT assays, Jay Schwartz for advice and assistance in generating the stable cell lines expressing MOD-5, and Beth Castor for DNA sequence determinations.

Correspondence should be addressed to H. Robert Horvitz, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Department of Biology, Room 68-425, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02139. E-mail: horvitz@mit.edu.

E. R. Sawin's present address: Sustainability Institute, 13 Spencer Meadow, Hartland, VT 05048.

C. Trent's present address: Biology Department, MS 9160, Western Washington University, 516 High Street, Bellingham, WA 98225-9160.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adkins EM, Barker EL, Blakely RD. Interactions of tryptamine derivatives with serotonin transporter species variants implicate transmembrane domain I in substrate recognition. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;59:514–523. doi: 10.1124/mol.59.3.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Avery L, Horvitz HR. A cell that dies during wild-type C. elegans development can function as a neuron in a ced-3 mutant. Cell. 1987;51:1071–1078. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90593-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avery L, Horvitz HR. Effects of starvation and neuroactive drugs on feeding in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Exp Zool. 1990;253:263–270. doi: 10.1002/jez.1402530305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baldessarini RJ. Drugs and the treatment of psychiatric disorders: depression and mania. In: Goodman LS, Gilman A, Hardman JG, Gilman AG, Limbird LE, Molinoff PB, Ruddon RW, editors. Goodman & Gilman's the pharmacological basis of therapeutics, Ed 9. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1996. pp. 431–459. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bargmann CI, Horvitz HR. Chemosensory neurons with overlapping functions direct chemotaxis to multiple chemicals in C. elegans. Neuron. 1991;7:729–742. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90276-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barker EL, Blakely RD. Structural determinants of neurotransmitter transport using cross-species chimeras: studies on serotonin transporter. Methods Enzymol. 1998;296:475–498. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(98)96035-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barker EL, Moore KR, Rakhshan F, Blakely RD. Transmembrane domain I contributes to the permeation pathway for serotonin and ions in the serotonin transporter. J Neurosci. 1999;19:4705–4717. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-12-04705.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bengel D, Murphy DL, Andrews AM, Wichems CH, Feltner D, Heils A, Mossner R, Westphal H, Lesch KP. Altered brain serotonin homeostasis and locomotor insensitivity to 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (“Ecstasy”) in serotonin transporter-deficient mice. Mol Pharmacol. 1998;53:649–655. doi: 10.1124/mol.53.4.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blakely RD, Berson HE, Fremeau RT, Jr, Caron MG, Peek MM, Prince HK, Bradley CC. Cloning and expression of a functional serotonin transporter from rat brain. Nature. 1991;354:66–70. doi: 10.1038/354066a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brenner S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1974;77:71–94. doi: 10.1093/genetics/77.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.C. elegans Sequencing Consortium. Genome sequence of the nematode C. elegans: a platform for investigating biology. Science. 1998;282:2012–2018. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang AS, Chang SM, Starnes DM, Schroeter S, Bauman AL, Blakely RD. Cloning and expression of the mouse serotonin transporter. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1996;43:185–192. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(96)00172-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen JX, Pan H, Rothman TP, Wade PR, Gershon MD. Guinea pig 5-HT transporter: cloning, expression, distribution, and function in intestinal sensory reception. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:G433–G448. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.275.3.G433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheng Y, Prusoff WH. Relationship between the inhibition constant (Ki) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50 percent inhibition (I50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem Pharmacol. 1973;22:3099–3108. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(73)90196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choy RK, Thomas JH. Fluoxetine-resistant mutants in C. elegans define a novel family of transmembrane proteins. Mol Cell. 1999;4:143–152. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80362-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cooper JR, Bloom FE, Roth RH. The biochemical basis of neuropharmacology, Ed 7. Oxford UP; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corey JL, Quick MW, Davidson N, Lester HA, Guastella J. A cocaine-sensitive Drosophila serotonin transporter: cloning, expression, and electrophysiological characterization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:1188–1192. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.3.1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Demchyshyn LL, Pristupa ZB, Sugamori KS, Barker EL, Blakely RD, Wolfgang WJ, Forte MA, Niznik HB. Cloning, expression, and localization of a chloride-facilitated, cocaine-sensitive serotonin transporter from Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:5158–5162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.5158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Desai C, Garriga G, McIntire SL, Horvitz HR. A genetic pathway for the development of the Caenorhabditis elegans HSN motor neurons. Nature. 1988;336:638–646. doi: 10.1038/336638a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duerr JS, Frisby DL, Gaskin J, Duke A, Asermely K, Huddleston D, Eiden LE, Rand JB. The cat-1 gene of Caenorhabditis elegans encodes a vesicular monoamine transporter required for specific monoamine-dependent behaviors. J Neurosci. 1999;19:72–84. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-01-00072.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ellis HM, Horvitz HR. Genetic control of programmed cell death in the nematode C. elegans. Cell. 1986;44:817–829. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hawley RG, Lieu FH, Fong AZ, Hawley TS. Versatile retroviral vectors for potential use in gene therapy. Gene Ther. 1994;1:136–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hille B. G protein-coupled mechanisms and nervous signaling. Neuron. 1992;9:187–195. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90158-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoffman BJ, Mezey E, Brownstein MJ. Cloning of a serotonin transporter affected by antidepressants. Science. 1991;254:579–580. doi: 10.1126/science.1948036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horvitz HR, Chalfie M, Trent C, Sulston JE, Evans PD. Serotonin and octopamine in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 1982;216:1012–1014. doi: 10.1126/science.6805073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jansen G, Hazendonk E, Thijssen KL, Plasterk RH. Reverse genetics by chemical mutagenesis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Genet. 1997;17:119–121. doi: 10.1038/ng0997-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jayanthi LD, Apparsundaram S, Malone MD, Ward E, Miller DM, Eppler M, Blakely RD. The Caenorhabditis elegans gene T23G5.5 encodes an antidepressant- and cocaine-sensitive dopamine transporter. Mol Pharmacol. 1998;54:601–609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kapatos G, Hirayama K, Shimoji M, Milstien S. GTP cyclohydrolase I feedback regulatory protein is expressed in serotonin neurons and regulates tetrahydrobiopterin biosynthesis. J Neurochem. 1999;72:669–675. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0720669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kitayama S, Shimada S, Xu H, Markham L, Donovan DM, Uhl GR. Dopamine transporter site-directed mutations differentially alter substrate transport and cocaine binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:7782–7785. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krause M, Hirsh D. A trans-spliced leader sequence on actin mRNA in C. elegans. Cell. 1987;49:753–761. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90613-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li Q, Wichems C, Heils A, Lesch KP, Murphy DL. Reduction in the density and expression, but not G-protein coupling, of serotonin receptors (5-HT1A) in 5-HT transporter knock-out mice: gender and brain region differences. J Neurosci. 2000;20:7888–7895. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-21-07888.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu LX, Spoerke JM, Mulligan EL, Chen J, Reardon B, Westlund B, Sun L, Abel K, Armstrong B, Hardiman G, King J, McCague L, Basson M, Clover R, Johnson CD. High-throughput isolation of Caenorhabditis elegans deletion mutants. Genome Res. 1999;9:859–867. doi: 10.1101/gr.9.9.859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Loer CM, Kenyon CJ. Serotonin-deficient mutants and male mating behavior in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. J Neurosci. 1993;13:5407–5417. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-12-05407.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maricq AV, Peterson AS, Brake AJ, Myers RM, Julius D. Primary structure and functional expression of the 5HT3 receptor, a serotonin-gated ion channel. Science. 1991;254:432–437. doi: 10.1126/science.1718042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martin GR, Eglen RM, Hamblin MW, Hoyer D, Yocca F. The structure and signalling properties of 5-HT receptors: an endless diversity? Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1998;19:2–4. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(97)01143-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mello CC, Kramer JM, Stinchcomb D, Ambros V. Efficient gene transfer in C. elegans: extrachromosomal maintenance and integration of transforming sequences. EMBO J. 1991;10:3959–3970. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04966.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mendel JE, Korswagen HC, Liu KS, Hajdu-Cronin YM, Simon MI, Plasterk RH, Sternberg PW. Participation of the protein Go in multiple aspects of behavior in C. elegans. Science. 1995;267:1652–1655. doi: 10.1126/science.7886455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miller KJ, Hoffman BJ. Adenosine A3 receptors regulate serotonin transport via nitric oxide and cGMP. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:27351–27356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mortensen OV, Kristensen AS, Rudnick G, Wiborg O. Molecular cloning, expression and characterization of a bovine serotonin transporter. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1999;71:120–126. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(99)00178-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]