Abstract

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a common neurodegenerative disease that lacks therapies to prevent progressive neurodegeneration. Impaired energy metabolism and reduced ATP levels are common features of PD. Previous studies revealed that terazosin (TZ) enhances the activity of phosphoglycerate kinase 1 (PGK1), thereby stimulating glycolysis and increasing cellular ATP levels. Therefore, we asked whether enhancement of PGK1 activity would change the course of PD. In toxin-induced and genetic PD models in mice, rats, flies, and induced pluripotent stem cells, TZ increased brain ATP levels and slowed or prevented neuron loss. The drug increased dopamine levels and partially restored motor function. Because TZ is prescribed clinically, we also interrogated 2 distinct human databases. We found slower disease progression, decreased PD-related complications, and a reduced frequency of PD diagnoses in individuals taking TZ and related drugs. These findings suggest that enhancing PGK1 activity and increasing glycolysis may slow neurodegeneration in PD.

Keywords: Neuroscience

Keywords: Parkinson’s disease

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most common neurodegenerative disease. It is estimated to affect approximately 6 million people worldwide, and its prevalence will increase further as populations age (1). Patients with PD suffer debilitating motor symptoms as well as nonmotor symptoms including dementia and neuropsychiatric abnormalities (2, 3). Dopamine neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) and their projections into the striatum are especially susceptible to disruption in PD (4). Loss and impaired function of dopamine neurons cause the motor abnormalities that are a hallmark feature of PD. Although current treatments can sometimes relieve PD symptoms, no therapies prevent the neurodegeneration (5).

PD may have a number of different causes, and several pathogenic mechanisms have been proposed to contribute to the apoptotic death of neurons (6–10). In the majority of cases, the etiologies are unknown and probably complex. Aging, environmental toxins, and genetic mutations are all risk factors. In many cases, energy deficits and decreased ATP levels are observed in PD (11). First, aging, the major risk factor for PD, impairs cerebral glucose metabolism, reduces mitochondrial biogenesis, and decreases ATP levels (12). Second, glycolysis and mitochondrial function are decreased in individuals with PD (13, 14). Third, mitochondrial toxins (1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine [MPTP], rotenone, paraquat) induce PD and PD-like phenotypes in cells and animals, including humans (15). Fourth, mutations associated with familial PD (e.g., PINK1, LRRK2, α-synuclein, parkin, DJ-1, CHCHD2) disrupt various aspects of energy metabolism (16). It is also hypothesized that SNc dopaminergic neurons may be particularly susceptible to PD neurodegeneration, because their highly branched, unmyelinated axonal arbor, their many neurotransmitter release sites, and their rhythmic firing engender a large metabolic burden (17). These considerations suggested that impaired bioenergetics and reduced ATP levels might contribute to the pathogenesis of PD, might modify the risk of developing PD in the face of PD risk factors, and/or might modify the course or severity of the disease.

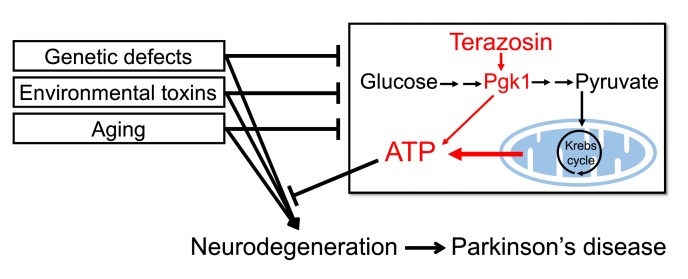

We recently discovered that terazosin (TZ) binds and activates phosphoglycerate kinase 1 (PGK1) (18), the first ATP-generating enzyme in glycolysis (Figure 1A). TZ is an α1-adrenergic receptor antagonist that can relax smooth muscle and is prescribed to treat benign prostatic hyperplasia and, rarely, hypertension (19). However, biochemical and functional studies show that the effects of TZ on PGK1 are independent of α1-adrenergic antagonism (18). The crystal structure of TZ with PGK1 revealed that the 2, 4-diamino-6, 7-dimethoxyisoquinazoline motif of TZ binds PGK1 adjacent to the ADP/ATP binding site. In cultured cells, TZ enhanced PGK1 activity, thereby increasing ATP levels, and inhibited apoptosis (18).

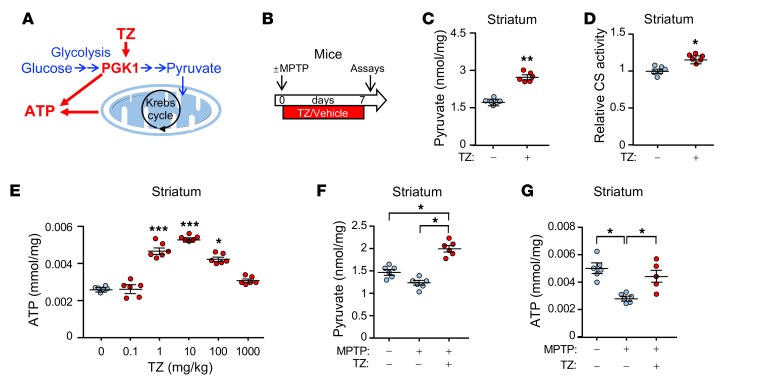

Figure 1. TZ enhances glycolysis in the mouse brain.

Data points represent individual mice. Blue indicates controls and red indicates TZ treatment. (A) Schematic of ATP production by glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation. (B) Schematic time course for experiments in C–G. Eight-week-old C57bl/6 mice were given MPTP (20 mg/kg i.p.) or vehicle 4 times at 2-hour intervals. Then, TZ (10 μg/kg) or vehicle was injected i.p. once a day for 1 week. Assays were performed on day 7. (C–E) Pyruvate levels (C), citrate synthase (CS) activity (D), and ATP levels (E) were measured in mouse striatum. TZ doses are indicated in E. n = 6. Statistical comparison was made versus no TZ treatment. (F and G) Pyruvate (F) and ATP (G) levels in the mouse striatal region. Supplemental Table 3 shows statistical tests and P values for all comparisons. Bars and whiskers indicate the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001, by Mann-Whitney U test (C and D), Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s test (E), and Kruskal-Wallis with Dwass-Steele-Critchlow-Fligner test (F and G).

The impaired energy production in PD, together with the ability of TZ to increase PGK1 activity, led us to hypothesize that increasing glycolysis in vivo might slow or prevent the apoptotic neurodegeneration of PD. To test this hypothesis, we used models of PD in flies, mice, rats, and human cells, and we interrogated patient databases to learn whether TZ altered the course of disease.

Results

TZ increases brain ATP levels in vivo in mice.

To determine whether TZ would enhance glycolysis in vivo, we administered the drug to mice. TZ increased the levels of pyruvate, the product of glycolysis, in the SNc and striatum as well as in cortex (Figure 1, B and C, and Supplemental Figure 1, A and B; supplemental material available online with this article; https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI129987DS1). Increased pyruvate enhances oxidative phosphorylation (20), and consistent with this finding, we observed that TZ increased citrate synthase activity, a marker of mitochondrial activity (Figure 1D and Supplemental Figure 1C). Correspondingly, we found that ATP levels increased (Figure 1E and Supplemental Figure 1D). Like previous in vitro data, the dose response was biphasic; our previous studies suggest that, at low but not high concentrations, TZ may enhance ATP release from PGK1 (18).

We also asked whether TZ would increase energy production in mice that received MPTP. MPTP causes PD in humans and is used to model PD in other animals (21, 22). Seven days after administration of MPTP to mice, pyruvate and ATP levels fell (Figure 1, F and G, and Supplemental Figure 2, A–C), and administration of TZ prevented the fall in pyruvate and ATP levels. Mitochondrial content (assessed by the ratio of mitochondrial DNA to nuclear DNA and by VDAC and PHB1 levels) also fell (Supplemental Figure 2, D–F). TZ partially prevented the decrease. As previously suggested (23), the increased pyruvate levels may have stimulated mitochondrial biogenesis. It would be difficult to measure ATP specifically in neurons, however, we observed similar changes in human neuroblastoma cells (Supplemental Figure 3, A–E). These data indicate that TZ activates glycolysis in vivo. Together with measurements of brain TZ levels (Supplemental Figure 3F), they also indicate that TZ readily crosses the blood-brain barrier.

Although PGK1 produces ATP, oxidative phosphorylation is probably important for increasing ATP on the basis of the following: (a) pyruvate, the product of glycolysis and major substrate for the citric acid cycle, increased (Figure 1, C and F, Supplemental Figure 1B, Supplemental Figure 2B, and Supplemental Figure 3A); (b) citrate synthase activity, a marker of mitochondrial activity, increased (Figure 1D, Supplemental Figure 1C, and Supplemental Figure 3B); (c) the extracellular acidification rate, a measure of glycolysis, and the O2 consumption rate, a measure of mitochondrial respiration, both increased (Supplemental Figure 3, D and E); and (d) mitochondrial content was partially maintained after MPTP (Supplemental Figure 2, D and F), which may have also contributed to the increased ATP content.

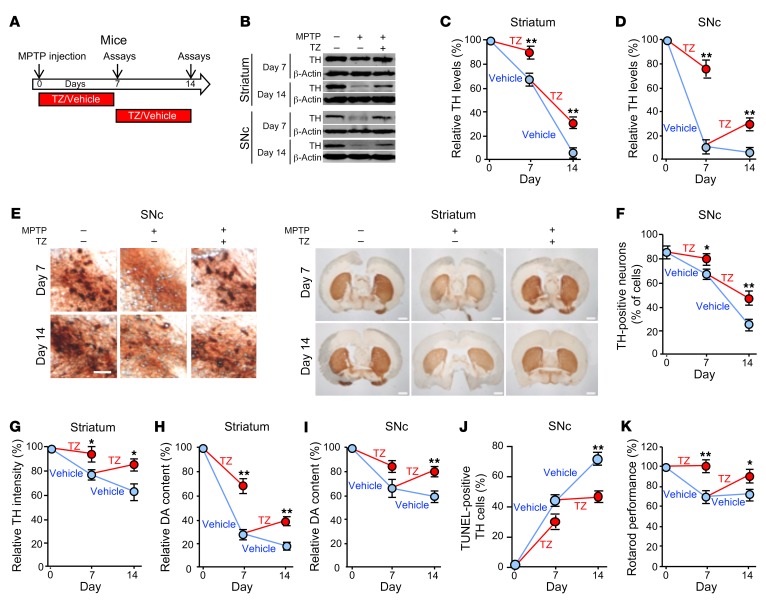

TZ decreases MPTP-induced neurodegeneration in mice.

MPTP can model aspects of dopamine neuron loss in mice (21). To determine whether PGK1 stimulation would slow or prevent MPTP-mediated deficits, we administered MPTP to the mice, followed by administration of TZ for the next 7 days, and an assay on day 7 (Figure 2A). Because individuals with PD present after the onset of neuron degeneration, we also asked whether delayed TZ administration would slow neuron loss and functional decline. Therefore, in some mice, we waited 7 days after delivering MPTP before starting the 7-day course of TZ treatment. We then performed an assay on day 14 (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. TZ improves dopamine neuron and motor function in MPTP-treated mice.

(A) Schematic for experiments in panels B–K. Eight-week-old C57BL/6 mice received 4 i.p. injections of MPTP (20 mg/kg at 2-hour intervals) or vehicle on day 0. Mice were then injected with TZ (10 μg/kg) or vehicle (0.9% saline) once a day for 1 week, and assays were performed on day 7. Other mice began receiving daily TZ or vehicle injections beginning on day 7, and assays were performed on day 14. n = 6. (B–D) Example of Western blots with TH and β-actin (protein loading control) in striatum and SNc on days 7 and 14 (B). Quantification of TH protein normalized to control (C and D). n = 6. (E) Example of immunostaining of TH in SNc and striatum. Scale bars: 100 μm (SNc) and 1 mm (striatum). Quantification of TH-positive neurons in SNc (F) and TH intensity in the striatum (G). n = 6. (H and I) Dopamine (DA) content in striatum and SnC. n = 6. (J) Percentage of TH-positive neurons that were positive for TUNEL staining. n = 6. (K) Behavioral response of mice in the rotarod test. Data reflect the duration that the mice remained on an accelerated rolling rod, normalized to mice on day 0. n = 8. Data represent examples and indicate the mean ± SEM. Blue indicates control and red indicates TZ treatment. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01, by Mann-Whitney U test for days 7 and 14. Supplemental Table 3 shows P values for all comparisons.

Over the course of 14 days, MPTP progressively decreased the levels of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), the rate-limiting enzyme for generating dopamine. MPTP decreased TH levels in the SNc and striatum, reduced the numbers of TH-positive cells in the SNc, and decreased the intensity of TH immunostaining in the neuron projections into the striatum (Figure 2, B–G, and Supplemental Figure 4, A and B). As a result, the dopamine, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC) and homovanillic acid (HVA) content of the striatum and SNc decreased (Figure 2, H and I, and Supplemental Figure 4, C–F). MPTP also increased the percentage of TH-positive cells that were TUNEL positive, indicating increased apoptosis (Figure 2J and Supplemental Figure 4, G and H). Beginning TZ treatment at the time we administered MPTP attenuated all these defects on day 7. When TZ delivery was delayed for 7 days after MPTP administration, it improved the abnormalities on day 14. Consistent with these biochemical defects, TZ prevented deficits in motor function on day 7, and it improved motor performance on day 14 after delayed administration (Figure 2K and Supplemental Figure 4, I and J).

These in vivo results in mice suggest that TZ slows or prevents MPTP-induced neurodegeneration, partially restores TH and dopamine levels, and improves motor function.

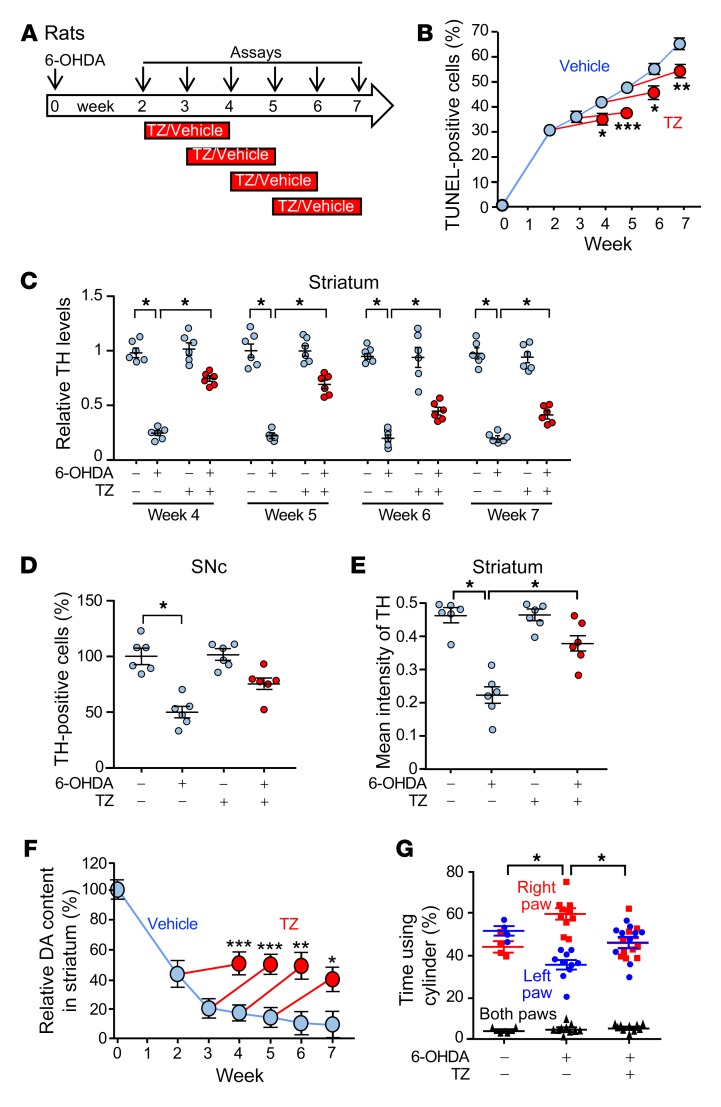

TZ enhancement of PGK1 activity slows neurodegeneration in 6-OHDA–treated rats.

The compound 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) is delivered to rats to produce a model of dopamine neuron degeneration in PD (24). Previous studies have shown progressive cell death and injury between 2 and 12 weeks after administration of 6-OHDA (25–27). Therefore, we chose a 7-week course of observation. We injected 6-OHDA into the right striatum of rats, waited 2–5 weeks, and then initiated a 2-week course of TZ treatment (Figure 3A). In vehicle-treated rats, evidence of SNc cell apoptosis progressively increased from 2 to 7 weeks (Figure 3B and Supplemental Figure 5, A and B). However, irrespective of the delay before the start of treatment, we observed that TZ attenuated further cell loss. 6-OHDA also progressively decreased TH levels in the striatum and SNc (Figure 3C and Supplemental Figure 5, C–F). The percentage of TH-positive cells in the SNc and the intensity of TH immunostaining in the striatum also decreased (Figure 3, D and E). TZ partially reverted these abnormalities toward control values. 6-OHDA progressively decreased dopamine, DOPAC, and HVA content, and TZ partially prevented the reduction (Figure 3F and Supplemental Figure 5, G and H). Seven weeks after injection of 6-OHDA into the right striatum, we observed that use of the left forepaw had fallen (Figure 3G), however, when the rats received TZ between weeks 5 and 7, they used both forepaws equally.

Figure 3. TZ slows neurodegeneration, increases dopamine, and improves motor performance in 6-OHDA–treated rats.

(A) Schematic for experiments in B–G. 6-OHDA (20 μg) was injected into the right striatum of rats on day 0. TZ (70 μg/kg) or saline was injected i.p. daily for 2 weeks, beginning 2, 3, 4, or 5 weeks after 6-OHDA injection. Assays were performed at 0 and 2–7 weeks. (B) Percentage of TUNEL-positive SNc cells. n = 6. (C) Quantification of TH protein levels assessed by immunoblotting in the striatum, normalized to control. n = 6. (D and E) Percentage of SNc cells positive for TH immunostaining (D) and intensity of TH immunostaining in striatum (E) 7 weeks after 6-OHDA injection. TZ treatment was administered from week 5 to week 7. n = 6. (F) Dopamine content in the right striatum relative to the left (control) striatum. n = 6. (G) Results of the cylinder test. 6-OHDA was injected into the right striatum, impairing use of the left paw. The assay was performed 7 weeks after 6-OHDA injection. TZ treatment was given from week 5 to week 7. n = 4 for control group and n = 10 for the two 6-OHDA groups. In C, D, E, and G, data points represent individual rats, and bars and whiskers indicate the mean ± SEM. Blue indicates controls and red indicates TZ treatment. Supplemental Table 3 shows statistical tests and P values for all comparisons. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001, by Mann-Whitney U test (B and F), Kruskal-Wallis with Dwass-Steele-Critchlow-Fligner test (C, D, and E), and Friedman with Dunn’s test (G).

Previous studies have shown that MPTP and 6-OHDA can rapidly reduce TH expression (21), and consistent with this finding, we observed that TH levels, TH-positive neurons, TH intensity in the striatum, and dopamine content decreased rapidly after administration of MPTP and 6-OHDA to mice and rats, respectively (Figures 2 and 3 and Supplemental Figures 4 and 5). Cell death was also apparent. However, not all the damaged cells were rapidly killed, as cell death continued to progress for at least 14 days in MPTP-treated mice and for 7 weeks in 6-OHDA–treated rats (Figure 2J and Figure 3B). Accordingly, TH levels, TH-positive neurons, TH intensity in the striatum, and dopamine content also continued to decrease further with time. Administration of TZ, even after the onset of neurodegeneration, slowed cell death, and it increased TH levels, dopamine content, and motor performance compared with vehicle-treated controls (Figures 2 and 3 and Supplemental Figures 4 and 5).

After MPTP and 6-OHDA administration, apoptotic cell death continued for 14 days and 7 weeks, respectively. Delayed TZ administration (beginning on day 7 in MPTP-treated mice and in week 5 in 6-OHDA–treated rats) slowed or prevented further apoptotic cell death. In MPTP-treated mice, dopamine levels, behavioral performance, and in some cases TH levels on day 14 exceeded those on day 7. Likewise, in 6-OHDA–treated rats, dopamine and TH levels by week 7 exceeded those in week 5. PD neurons that have not yet undergone apoptotic cell death almost certainly have impaired metabolic function (28). Our results suggest that TZ improved the function of neurons that were impaired by MPTP and 6-OHDA but had not yet degenerated.

TZ enhances PGK activity to attenuate rotenone-induced neurodegeneration in flies.

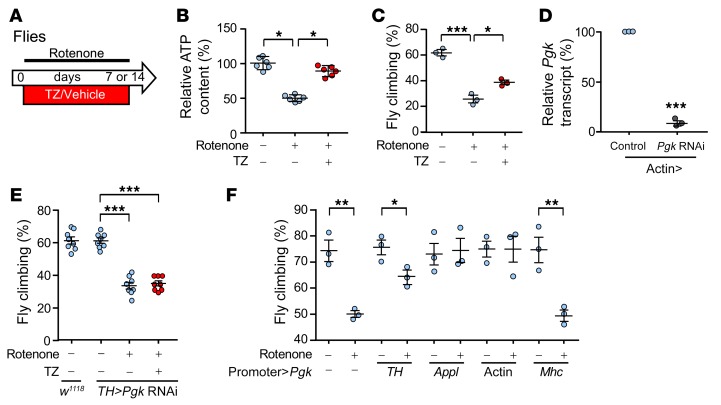

As an additional model of PD, we treated Drosophila melanogaster with rotenone, a mitochondrial complex I inhibitor implicated in sporadic PD (29). Rotenone exposure reduced brain ATP levels (Figure 4, A and B). It also disrupted motor function as tested by climbing behavior (Figure 4C). PGK is highly conserved in flies and mammals, and supplying TZ together with rotenone minimized decrements in ATP content and motor performance.

Figure 4. TZ enhances Pgk activity to attenuate rotenone-impaired motor performance.

(A) Schematic for experiments in panels B–F. Flies received rotenone (125 or 250 μM in food) with TZ (1 μM) or vehicle for 7 or 14 days. (B) Relative ATP content in the brains of w1118 flies that received 250 μM rotenone with or without TZ for 14 days. n = 6, with 200 fly heads for each treatment in each trial. (C) Climbing behavior of flies after 250 μM rotenone with TZ (1 μM) or vehicle for 7 days. Data show the percentage of flies that climbed up a tube (see Methods). n = 3, with 200 flies tested for each treatment in each trial. (D) Knockdown of Pgk in offspring of actin-Gal4 crossed with UAS-Pgk RNAi flies. Offspring of actin-Gal4 crossed with y1 v1 P [CaryP] attP2 were used as a genetic background matched control. n = 3, with RNA collected from 30 fly heads for each sample. (E) Pgk was knocked down in TH neurons by crossing UAS-Pgk RNAi flies with flies carrying the TH neuron-specific promoter (TH-Gal4) to produce TH>Pgk RNAi flies. Rotenone (250 μM) and TZ were administered as indicated for 7 days. Climbing behavior was measured on day 7. n = 8, with 200 flies tested for each treatment in each trial. (F) Pgk (UAS-Pgk) overexpression was driven by a dopaminergic neuron promoter (TH-Gal4), a pan-neuronal promoter (Appl-Gal4), a pan-cell promoter (Actin-Gal4), and a muscle-specific promoter (Mhc-Gal4). Rotenone (250 μM) was administered for 7 days, and climbing behavior was measured on day 7. n = 3, with 200 flies tested for each treatment in each trial. Data points represent individual groups of flies, and bars and whiskers show the mean ± SEM. Blue indicates controls and red indicates TZ treatment. Supplemental Table 3 shows statistical tests and P values for all comparisons. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001, by Kruskal-Wallis with a Dwass-Steele-Critchlow-Fligner test (B), 1-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test (C and E), paired t test (D), and unpaired t test (F).

Previous studies showed that TZ increases ATP by enhancing PGK1 activity (18, 30). We knocked down Pgk in Drosophila by expressing RNAi and found that it abolished the protective effect of TZ on motor performance (Figure 4, D and E, vs. Figure 4C). Conversely, overexpression of PGK1 in Drosophila TH neurons, all neurons (Appl promoter), or all cells (actin promoter) made flies resistant to rotenone-induced behavioral defects (Figure 4F). In contrast, we found that expression in muscle was not protective. These results, together with earlier findings (18, 30), indicate that TZ protects TH neurons by activating PGK1.

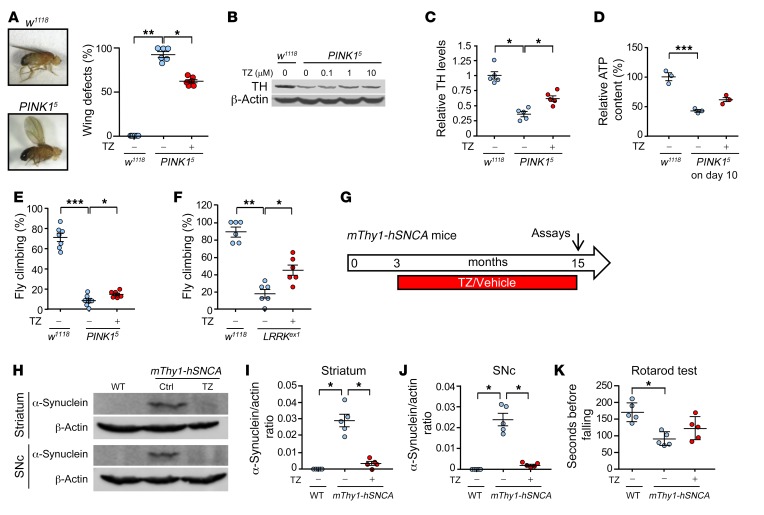

TZ attenuates neurodegeneration in genetic models of PD.

In addition to toxin-induced models, we tested fly, mouse, and human genetic models of PD. PINK1 mutations cause PD in humans; we therefore tested the Drosophila PINK15 mutant (31–33). We administered vehicle or TZ from day 1 after hatching to day 10. On day 10, nearly all PINK15 flies exhibited wing posture defects (Figure 5A). TZ partially reversed this abnormality. Brain TH and ATP levels also decreased, and motor performance was impaired in PINK15 flies (Figure 5, B–E, and Supplemental Figure 6). TZ partially corrected these defects. We also tested the Drosophila LRRKex1 mutant (34); LRRK2 mutations cause autosomal-dominant, late-onset PD (35). TZ also attenuated motor deficits in that model (Figure 5F).

Figure 5. TZ improves TH levels and motor performance in genetic models of PD.

Data points are from individual mice and groups of flies. (A–E) WT (w1118) and PINK15 flies received TZ or vehicle for 10 days beginning on the first day after eclosion. Day 10 assays included: (A) Example of wing posture defect and percentage of w1118 and PINK15 flies with wing posture defects. n = 6, with 80 flies for each treatment in each trial. (B and C) Example of TH Western blot (B) and quantification of TH (C). n = 5, with 40 fly heads for each treatment in each trial. (D) ATP content in brains (relative to w1118). n = 3, with 200 fly heads for each treatment in each trial. (E) Climbing behavior of flies. n = 3, with 100 flies for each treatment in each trial. (F) Climbing behavior of LRRKex1 male flies. n = 6, with 100 flies for each treatment in each trial. (G–K) TZ administration to mThy1-hSNCA–transgenic mice. (G) Schematic for experiments in panels H–K. (H) Example of Western blot of α-synuclein in striatum and SNc. (I and J) Quantification of α-synuclein in striatum and SNc. n = 5. (K) Duration that mice remained on an accelerating rotarod. n = 5. Data are from individual groups of flies (A–F) and individual mice (I–K). Bars and whiskers indicate the mean ± SEM. Blue indicates controls and red indicates TZ treatment. Supplemental Table 3 shows statistical tests and P values for all comparisons. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001, by 1-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test (D) and Kruskal-Wallis with a Dwass-Steele-Critchlow-Fligner test (A–C, E, F, and I–K).

Abnormal accumulation of α-synuclein, a major constituent of Lewy bodies, is a key feature of PD (36). Transgenic mice overexpressing WT human α-synuclein (mThy1-hSNCA) exhibit PD-like neurodegeneration at an advanced age (37). We began treating mThy1-hSNCA mice at 3 months of age with vehicle or TZ. When they were 15 months old, the vehicle-treated mice had substantial expression of human α-synuclein in the striatum and SNc (Figure 5, G–J) and impaired motor performance on the rotarod and pole tests (Figure 5K and Supplemental Figure 7). TZ treatment partially prevented these abnormalities.

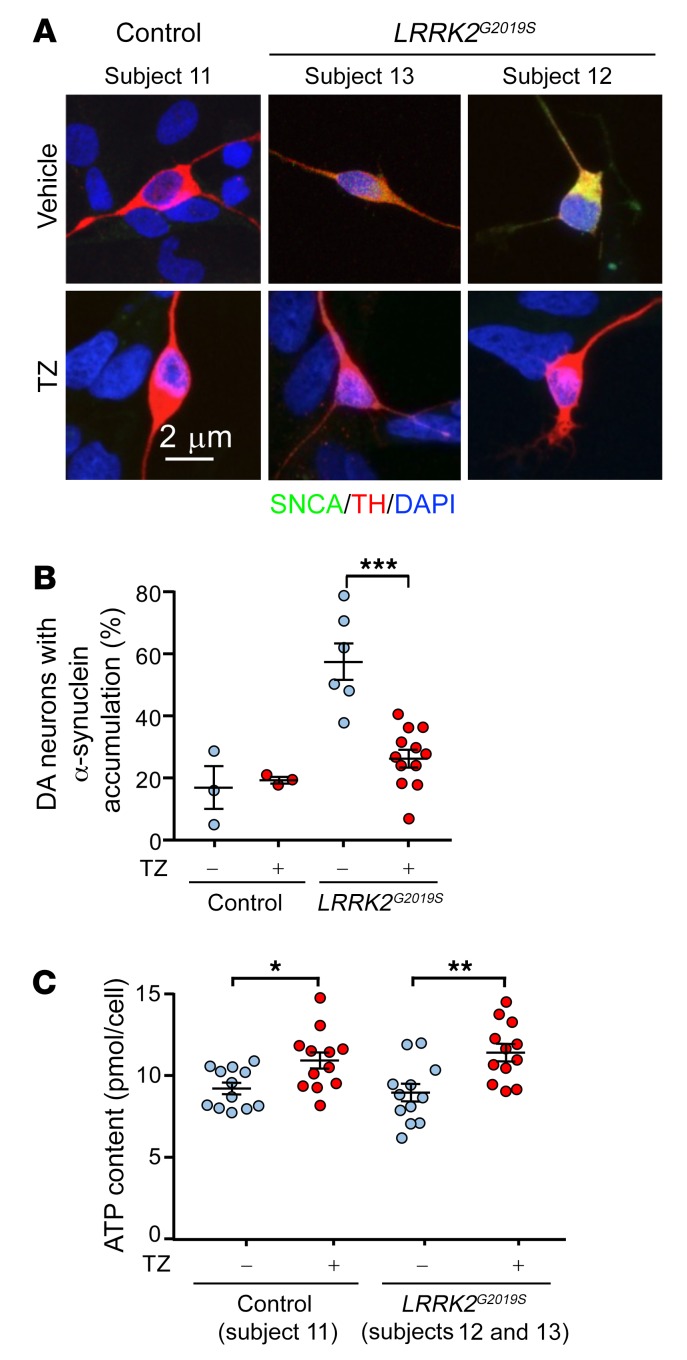

We also tested the effect of TZ on dopamine neurons differentiated from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). LRRK2G2019S is the most common LRRK2 mutation and is associated with approximately 4% of familial PD cases and approximately 1% of sporadic PD cases (38). Dopamine neurons derived from LRRK2G2019S iPSCs recapitulate PD features including abnormal α-synuclein accumulation (39). We studied such neurons generated from 2 patients. After 30 days of differentiation, the dopamine neurons showed no overt signs of neurodegeneration (Supplemental Figure 8). However, approximately 60% of the LRRK2G2019S dopamine neurons had accumulated α-synuclein compared with approximately 15% of dopamine neurons from healthy individuals (Figure 6, A and B). Addition of TZ for 24 hours increased the ATP content and reduced the percentage of LRRK2G2019S dopamine neurons with elevated α-synuclein accumulation (Figure 6, A–C).

Figure 6. TZ increases ATP content and decreases α-synuclein accumulation in iPSC-derived dopamine neurons from patients with PD.

(A) iPSC-derived dopamine neurons from 2 patients with PD (subjects 12 and 13) carrying LRRK2G2019S mutations and a healthy control (subject 11). Thirty-day-old dopamine neurons were plated and were treated with TZ (10 μM) 1 or 3 days later. The neurons were studied 24 hours after addition of TZ. We observed no difference between the 2 start dates and therefore combined the data. Representative immunofluorescence images of α-synuclein (SNCA, green), TH (red), and DAPI (nuclei, blue). (B) Percentage of TH-positive neurons with cytoplasmic accumulation of α-synuclein. n = 12. (C) ATP content in control and LRRK2G2019S iPSC–derived dopamine neurons. n = 12. Bars and whiskers indicate the mean ± SEM. Blue indicates controls and red indicates TZ treatment. Supplemental Table 3 shows statistical tests and P values for all comparisons. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001, by Mann-Whitney U test.

In the Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative database, individuals with PD who were taking TZ had a reduced rate of progressive motor disability.

In the past, assessment of whether an agent might affect PD has been largely limited to animal models. Three factors allowed us to assess efficacy in humans. First, TZ is a relatively commonly used drug. Second, availability of human clinical databases allowed us to test for a TZ effect. Third, tamsulosin can serve as a control for TZ. Like TZ, tamsulosin is an α1-adrenergic antagonist, and, like TZ, tamsulosin is prescribed for benign prostatic hyperplasia. However, in contrast to TZ, tamsulosin does not have a quinazoline motif that binds to and enhances PGK1 activity.

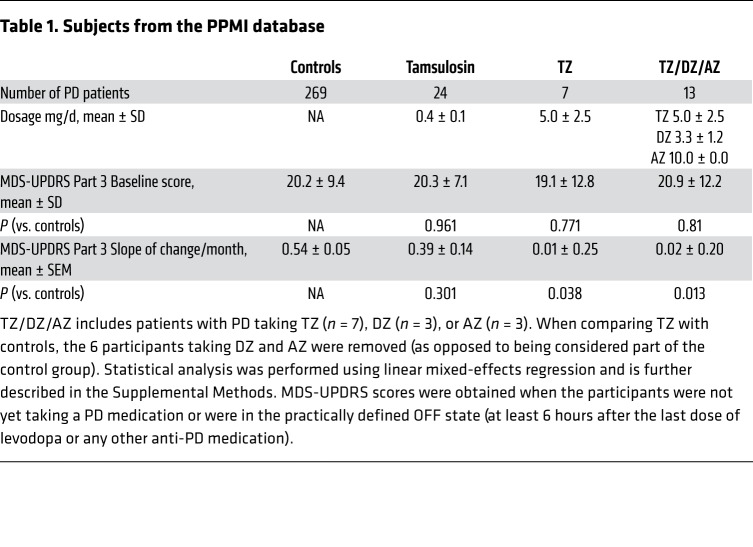

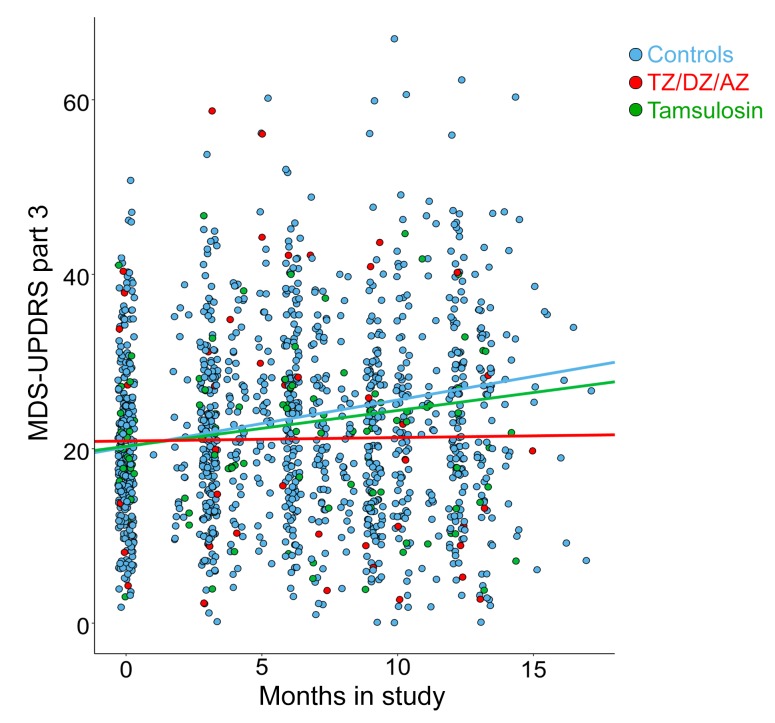

PD is common in older men, its incidence increases markedly after age 60, and the prevalence of the disease in men is approximately 1.5 times that in women (40). TZ is prescribed for benign prostatic hyperplasia, a disease that also affects older men. Therefore, we suspected that some patients with PD used TZ, and we hypothesized that they would have a reduced rate of disease progression. To test this hypothesis, we interrogated the Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative (PPMI) database. This database enrolls patients with PD shortly after diagnosis and follows their motor function as determined by the Movement Disorder Society’s Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale Part 3 (41). Although this clinical database is small, it is relatively unique in assessing motor progression. We identified 7 men with PD who used TZ and compared them with 269 men not taking TZ. Compared with the controls, the patients who used TZ had a slower rate of motor function decline (Table 1). Although the difference was statistically significant, only 7 patients used TZ. We therefore sought a larger sample.

Table 1. Subjects from the PPMI database.

The crystal structure of TZ with PGK1 (18) suggested that related drugs with quinazoline motifs might also enhance PGK1 activity. Consistent with that possibility, doxazosin (DZ) and alfuzosin (AZ) increased glycolysis in M17 cells and tyrosine hydroxylase levels in MPTP-treated mice (Supplemental Figure 9, A and B). We identified 13 men in the PPMI database who were using TZ, DZ, or AZ (TZ/DZ/AZ) (Table 1). The progression of motor disability was slowed in those patients (Figure 7, Supplemental Figure 10, and Table 1).

Figure 7. TZ and related drugs slow the progression of motor defects for patients with PD enrolled in the PPMI database.

Movement Disorder Society–Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS) Part 3 (motor) scores for patients with PD in the PPMI database. Patients were taking TZ/DZ/AZ (blue, n = 13), tamsulosin (green, n = 24), or none of these drugs (red, n = 269). Data represent scores upon entry into the PPMI database through approximately 1 year and include all measures between those times. All patients taking these drugs were men prescribed TZ/DZ/AZ or tamsulosin, without breaks for benign prostatic hyperplasia or undefined urological problems. Lines are plotted from linear mixed-effect regression analyses. By maximum likelihood estimation, TZ/DZ/AZ differed from controls (P = 0.012).

In contrast to TZ, DZ, and AZ, tamsulosin lacks a quinazoline motif for binding to PGK1. Consistent with that, tamsulosin did not rescue tyrosine hydroxylase levels in MPTP-treated mice (Supplemental Figure 9B). Correspondingly, tamsulosin failed to slow the motor function decline of patients enrolled in the PPMI database (Figure 7 and Table 1). These data are also consistent with the conclusion that enhanced glycolytic activity and attenuation of cell death are mediated by the effect of TZ on PGK1 and not on α1-adrenergic receptors.

The IBM Watson/Truven database shows that individuals with PD who used TZ/DZ/AZ had fewer PD-related diagnoses.

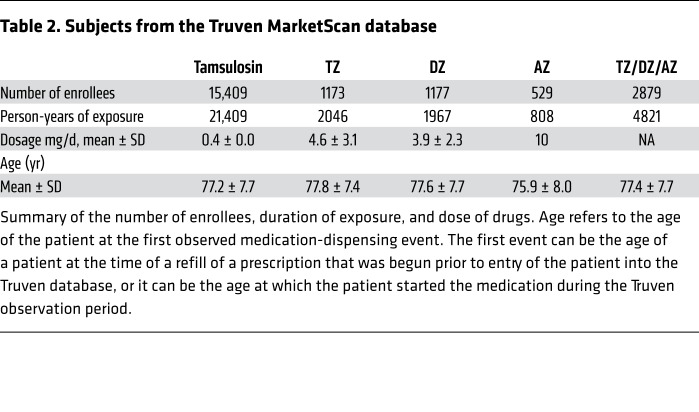

To evaluate a larger number of individuals with PD and to use a different database and assessment methods, we interrogated the IBM Watson/Truven Health Analytics MarketScan Database for the years 2011 to 2016. The database includes longitudinal, deidentified diagnoses (ICD-9/ICD-10 codes) and pharmaceutical claims. We identified 2880 PD patients with PD taking TZ/DZ/AZ (4821 person years) (Table 2). For a comparison group, we chose patients with PD who were taking tamsulosin, which controlled for use of an α1-adrenergic antagonist and for the presence of benign prostatic hyperplasia. We identified 15,409 individuals with PD who were taking tamsulosin (21,409 person years). To obtain a list of diagnostic codes associated with PD, we first identified the 497 most common diagnostic codes in the group of individuals with PD. Then, 2 neurologists who care for patients with PD identified 79 potentially PD-related diagnoses (Supplemental Table 1).

Table 2. Subjects from the Truven MarketScan database.

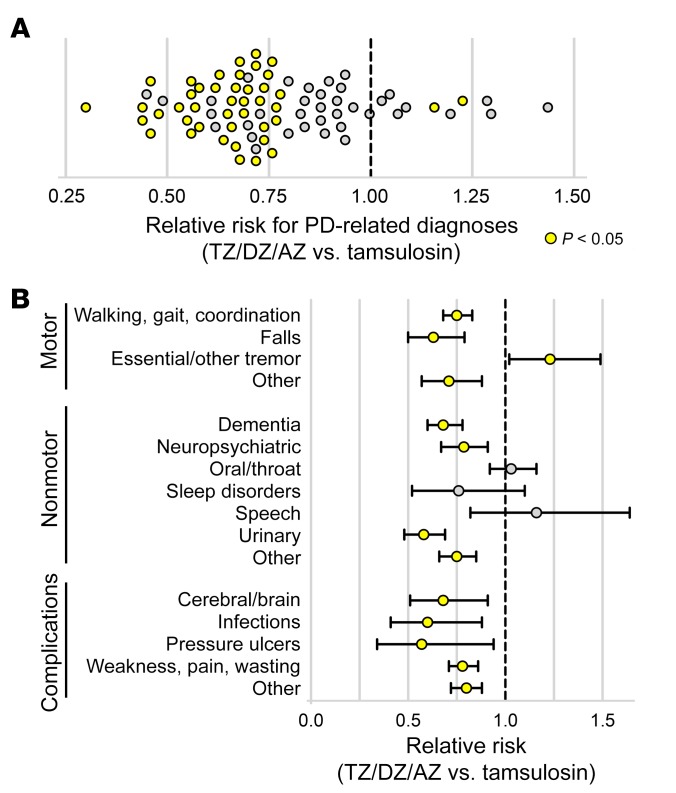

Using a quasi-Poisson generalized linear model, we found that the relative risk (RR) of having any of the 79 PD-related diagnostic codes was 0.78 (95% CI: 0.74–0.82) for the TZ/DZ/AZ group relative to the individuals on tamsulosin (P < 0.00001). Of the 79 PD-related codes, we found a reduced risk in 69 codes among patients with PD who were taking TZ/DZ/AZ versus those taking tamsulosin (Figure 8A). Moreover, 41 diagnostic codes were statistically significantly decreased in the PD patients taking TZ/DZ/AZ versus those on tamsulosin, whereas only 2 diagnostic codes were significantly increased in the TZ/DZ/AZ group.

Figure 8. TZ and related drugs reduce symptoms as assessed by diagnostic codes for patients with PD in the Truven/IBM Watson clinical database.

Data are from the Truven Health Marketscan Commercial Claims and Encounters and Medicare Supplemental Databases for the years 2011–2016. Patients had a diagnosis of PD and were prescribed TZ/DZ/AZ or tamsulosin for at least 1 year. We assessed RRs for 79 previously identified PD-related diagnostic codes. (A) RR for 79 PD-related diagnostic codes for patients taking TZ/DZ/AZ versus tamsulosin. Yellow indicates a statistically significant difference in risk between TZ/DZ/AZ and tamsulosin (P < 0.05) determined by a generalized linear model with a quasi-Poisson distribution. (B) RR for the categories of PD-related diagnostic codes for patients taking TZ/DZ/AZ versus tamsulosin. Data represent the mean and 95% CIs.

To estimate PD-related benefits and risks attributable to TZ/DZ/AZ versus tamsulosin, we calculated the RR for clinically relevant groupings of the 79 PD-related codes. Relative to patients with PD taking tamsulosin, those on TZ/DZ/AZ had reduced clinic and hospital visits for motor symptoms (RR 0.77; 95% CI: 0.70–0.84), nonmotor symptoms (RR 0.78; 95% CI: 0.73–0.83), and PD complications (RR 0.76; 95% CI: 0.71–0.82) (Figure 8B, Supplemental Table 1, and Supplemental Table 2). Of note, dopamine analogs do not treat PD symptoms such as dementia and neuropsychiatric manifestations (3). However, the RR for these diagnostic codes was also less than 1.0.

These data suggest that under real-world conditions, TZ and related drugs that enhance PGK1 activity reduce PD signs, symptoms, and complications.

Individuals who used TZ/DZ/AZ had a decreased risk of PD diagnosis.

We also used the Truven database to test whether TZ/DZ/AZ might reduce the frequency of PD diagnoses. We identified 78,444 PD-free enrollees who were taking TZ/DZ/AZ. During a follow-up duration of 284 ± 382 days (mean ± SD), a total of 118 individuals (0.15%) developed PD. In contrast, in an equal-sized cohort of PD-free enrollees taking tamsulosin and matched for age and follow-up duration (284 ± 381 days), 190 individuals (0.25%) developed PD. The HR from the Cox proportional hazards regression for the matched cohort was 0.62 (95% CI: 0.49–0.78; P < 0.0001).

Discussion

Our results indicate that in both toxin-induced and genetic models of PD in multiple animal species, enhancement of PGK1 activity slows or prevents neurodegeneration in vivo, thereby increasing dopamine levels and improving motor performance. Enhancement of PGK1 activity showed beneficial effects, even when begun after the onset of neurodegeneration. Moreover, interrogation of 2 independent databases suggested that TZ and related quinazoline agents slowed disease progression, reduced PD-related complications in individuals with PD, and reduced the risk of receiving a PD diagnosis.

Evidence from our present and earlier experiments indicates that TZ elicits its beneficial effects in PD by enhancing the activity of PGK1 and not by inhibiting the α1-adrenergic receptor. Our earlier experiments and crystal structure showed that the quinazoline motif of TZ binds PGK1 near the nucleotide binding site (18). Studies with recombinant PGK1, studies using cultured cells, and measurements in brain following in vivo delivery all revealed a biphasic relationship between the concentration of TZ and ATP levels (18). In the present study, tamsulosin inhibited α1-adrenergic receptors, but its structure lacks a quinazoline group that binds PGK1, and it did not enhance glycolysis or prevent the reduction of tyrosine hydroxylase levels in MPTP-treated mice. In contrast, 2 drugs that have a structure similar to that of TZ (DZ and AZ) enhanced glycolysis in vitro and protected MPTP-treated mice. Knockdown of Pgk1 in Drosophila TH neurons abolished the protective effect of TZ. Overexpression of PGK1 in flies, mice, and fish phenocopied the effects of TZ (18, 30). TZ was active in Drosophila melanogaster, which do not have α1-adrenergic receptors. Allosteric and covalent regulatory mechanisms have been identified for most glycolytic enzymes. For example, insulin-stimulated deacetylation increases PGK1 activity, and disrupting that regulation results in glycolytic insufficiency (42).

Previous work has identified numerous genetic mutations and several environmental factors that cause or predispose individuals to PD (11–16, 43). As indicated above, reduced energy metabolism and decreased ATP levels are a feature of many of these environmental and genetic factors, as is aging, the major PD risk factor. Therefore, enhancing glycolysis might slow progression in PD of several etiologies.

This study does not reveal how enhanced glycolysis slows neurodegeneration and progression in PD. However, the increased ATP levels produced by TZ may be key. ATP has properties of a hydrotrope; it can prevent aggregate formation and dissolve previously formed protein aggregates (44, 45). Moreover, the transition between aggregate stability and dissolution occurs in a narrow range at physiological ATP concentrations. We speculate that by elevating ATP levels, TZ facilitates the solubilization of aggregates, including α-synuclein, and prevents the neurodegeneration of PD. However, other mechanisms are also possible including ATP-dependent disaggregases and chaperones (such as hsp90) that reduce apoptosis (18, 44, 45).

This study also has limitations, including those for toxin-induced and genetic models of PD (46). Toxins such as MPTP and rotenone can cause PD in humans and PD-like disease in animals. Genetic defects also cause PD in humans and PD-like disease in animals. However, most PD is age related, with etiologies that remain unidentified and are likely complex. Moreover, no current model unequivocally or accurately predicts therapeutic benefit or pathogenesis. It is precisely for these reasons that we used multiple animal models of PD and that we sought out human data. A second limitation is that our analysis of human databases was limited to men, because they are treated for benign prostatic hyperplasia. However, we expect that similar results would be obtained in women. Third, our data from humans are retrospective; however, these data provide compelling evidence that cannot be obtained from animal models alone. Fourth, our analysis of the PPMI and Truven databases compared patients on TZ/DZ/AZ with those on tamsulosin. Although all the drugs were prescribed for benign prostatic hyperplasia, we cannot exclude the possibility that some other factor might have influenced prescribing behavior. For example, orthostatic hypotension is a complication of both the autonomic dysfunction in PD and of the drugs, and there are reports suggesting that tamsulosin may elicit less orthostatic hypotension than TZ (47). However, such an effect would not explain the PPMI conclusions. Interestingly, the risk of orthostatic hypotension and falls was reduced, not increased, for patients with PD taking TZ/DZ/AZ versus those on tamsulosin. In PD, neurons that have not yet degenerated almost certainly have compromised cellular function (28), and we speculate that TZ/DZ/AZ improved their functional integrity.

Results from this study, together with earlier data, led us to 3 additional speculations. First, TZ is already used clinically, and in this regard, it is interesting that several studies reported that TZ improved glucose metabolism in patients with diabetes (48, 49). That observation has gone unexplained. We speculate that stimulation of PGK1 activity might have been responsible. Consistent with that conjecture and with the conclusion that an α1-adrenergic receptor antagonistic effect was not responsible, we found that α1-adrenergic receptor antagonists structurally unrelated to TZ lacked that effect. In addition, disruption of the α1B-adrenergic receptor in mice had an effect opposite of that induced by TZ (50). Second, loss-of-function PGK1 mutations cause recessive hemolytic anemia, myopathy, seizures, and intellectual disability. However, other studies have reported Parkinsonism (51, 52), and the authors speculated that reduced ATP generation in the SNc may have been responsible. Third, PD occurs approximately 1.5 times more frequently in men than in women (53). Why males are more predisposed to PD is unknown. However, it may be worth noting that the PGK1 gene is located on the X chromosome. Thus, the consequences of DNA sequence variations that could subtly reduce PGK1 levels or activity might more often manifest in men than in women.

Our findings that TZ increased glycolysis and prevented progressive neurodegeneration suggest that energy deficits might either be a pathogenic factor in the pathogenesis of PD or predispose individuals to PD in the presence of environmental or genetic etiologies (11, 16). These findings identify a protein and a pathway that might be targeted to slow or prevent neurodegeneration in PD and potentially other neurodegenerative diseases with altered energy balance (54).

Methods

The Supplemental Methods contain information on the materials, reagents, experimental procedures, and analysis methods used in this study.

Statistics.

For experiments to quantify animal behavior and for sample collections, the experimenters were blinded to the genotype and intervention, and the studies were conducted by 2 different experimenters. The number of animals studied was based on our past experience and preliminary data. In all figures, data points are from individual mice and rats or groups of flies. We did not exclude any data points from this study. Data in the figures indicate the mean ± SEM. Blue indicates controls, and red indicates TZ treatment. Statistical significance for comparisons between data sets was primarily done with nonparametric tests. For studies of fly motor performance, our previous studies showed that within a group of flies (15–50 flies for 1 data point), the data fit a Gaussian distribution. Moreover, data for multiple groups of flies also fit a Gaussian distribution. Therefore, parametric tests were used to evaluate statistical significance in studies using flies, and ANOVA evaluations were 1 way. All statistical tests were 2 tailed. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Supplemental Table 3 shows the statistical tests used for all data and the resulting P values for comparisons.

Study approval.

All experiments using mice and rats were approved by the IACUC of Peking University in Beijing (approval nos. LSC-Liul-1 and LSC-Liul-2).

Author contributions

RC designed and performed many of the experiments and analyzed the data. YZ and YL performed fly and mouse studies. IFC and AC performed LRRK2 iPCS studies. AR designed the LRRK2-mutant iPSC studies. JES and PMP performed the analysis of the Truven database. YY, ZC, and WS performed parts of the animal behavior tests. JLS and NSN performed the PPMI database analysis. YH, CZ, and LG provided technical support and data analysis. XJ designed experiments. MJW designed experiments and analyzed data. LL designed and supervised experiments and analyzed data. RC, AR, MJW, and LL wrote the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Carles Calatayud (Center of Regenerative Medicine in Barcelona, Hospital Duran i Reynals, Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona, Spain) for help and advice with iPSC cultures. We thank Andrew Thurman (Department of Internal Medicine, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa) for assistance with the statistical analysis. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (91649201 and 31771121, to LL) and Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals Clinical Medicine Development of Special Funding Support (ZYLX201706, to LL); the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (MINECO) (SAF2015-69706-R, to AR, and BFU2016-80870-P, to AC); and the Instituto de Salud Carlos III – ISCIII/FEDER (Red de Terapia Celular: TerCel RD16/0011/0024 and PIE14/00061, to AR). Additional support was provided by the European Research Council (ERC) 2012-StG (311736- PD-HUMMODEL, to AC); the AGAUR (Agency for Management of University and Research Grants (2017-SGR-899); the CERCA Programme/Generalitat de Catalunya (to AR); and the Roy J. Carver Charitable Trust and the Pappajohn Biomedical Institute (to MJW). MJW is an investigator at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Version 1. 09/16/2019

Electronic publication

Version 2. 10/01/2019

Print issue publication

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Copyright: © 2019, American Society for Clinical Investigation.

Reference information: J Clin Invest. 2019;129(10):4539–4549.https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI129987.

Contributor Information

Rong Cai, Email: 1301111624@pku.edu.cn.

Yu Zhang, Email: yuzhang_2013@126.com.

Jacob E. Simmering, Email: jacob-simmering@uiowa.edu.

Jordan L. Schultz, Email: jordan-schultz@uiowa.edu.

Yuhong Li, Email: yuhongli@ccmu.edu.cn.

Antonella Consiglio, Email: consiglio@ub.edu.

Angel Raya, Email: araya@cmrb.eu.

Philip M. Polgreen, Email: philip-polgreen@uiowa.edu.

Nandakumar S. Narayanan, Email: nandakumar-narayanan@uiowa.edu.

Yanpeng Yuan, Email: m18237902837@163.com.

Zhiguo Chen, Email: chenzhiguo@gmail.com.

Wenting Su, Email: wtsu@ccmu.edu.cn.

Yanping Han, Email: yanping-han@hotmail.com.

Chunyue Zhao, Email: chunyuezhaopku@163.com.

Lifang Gao, Email: lifanggao@ccmu.edu.cn.

Xunming Ji, Email: jixm@ccmu.edu.cn.

Lei Liu, Email: leiliu@ccmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.GBD 2016 Neurology Collaborators Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(5):459–480. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30499-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fahn S. The history of dopamine and levodopa in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2008;23(Suppl 3):S497–S508. doi: 10.1002/mds.22028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaudhuri KR, Odin P. The challenge of non-motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease. Prog Brain Res. 2010;184:325–341. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(10)84017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalia LV, Lang AE. Parkinson’s disease. Lancet. 2015;386(9996):896–912. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61393-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maiti P, Manna J, Dunbar GL. Current understanding of the molecular mechanisms in Parkinson’s disease: Targets for potential treatments. Transl Neurodegener. 2017;6:28. doi: 10.1186/s40035-017-0099-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braak H, Del Tredici K. Neuropathological staging of brain pathology in sporadic Parkinson’s disease: Separating the wheat from the chaff. J Parkinsons Dis. 2017;7(s1):S71–S85. doi: 10.3233/JPD-179001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hunn BH, Cragg SJ, Bolam JP, Spillantini MG, Wade-Martins R. Impaired intracellular trafficking defines early Parkinson’s disease. Trends Neurosci. 2015;38(3):178–188. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2014.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson ME, Stecher B, Labrie V, Brundin L, Brundin P. Triggers, facilitators, and aggravators: Redefining Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis. Trends Neurosci. 2019;42(1):4–13. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2018.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lunati A, Lesage S, Brice A. The genetic landscape of Parkinson’s disease. Rev Neurol (Paris) 2018;174(9):628–643. doi: 10.1016/j.neurol.2018.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grünewald A, Kumar KR, Sue CM. New insights into the complex role of mitochondria in Parkinson’s disease. Prog Neurobiol. 2019;177:73–93. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2018.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saxena U. Bioenergetics failure in neurodegenerative diseases: back to the future. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2012;16(4):351–354. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2012.664135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoyer S. Brain glucose and energy metabolism during normal aging. Aging (Milano) 1990;2(3):245–258. doi: 10.1007/BF03323925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsu CC, et al. Risk factors for myopia progression in second-grade primary school children in Taipei: a population-based cohort study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2017;101(12):1611–1617. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2016-309299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schapira AH. Mitochondrial complex I deficiency in Parkinson’s disease. Adv Neurol. 1993;60:288–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blesa J, Phani S, Jackson-Lewis V, Przedborski S. Classic and new animal models of Parkinson’s disease. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2012;2012:845618. doi: 10.1155/2012/845618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schapira AH. Mitochondria in the aetiology and pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7(1):97–109. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70327-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Surmeier DJ. Determinants of dopaminergic neuron loss in Parkinson’s disease. FEBS J. 2018;285(19):3657–3668. doi: 10.1111/febs.14607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen X, et al. Terazosin activates Pgk1 and Hsp90 to promote stress resistance. Nat Chem Biol. 2015;11(1):19–25. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilt TJ, Howe W, MacDonald R. Terazosin for treating symptomatic benign prostatic obstruction: a systematic review of efficacy and adverse effects. BJU Int. 2002;89(3):214–225. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-4096.2001.02537.x-i1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Compan V, et al. Monitoring mitochondrial pyruvate carrier activity in real time using a BRET-based biosensor: investigation of the Warburg effect. Mol Cell. 2015;59(3):491–501. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heikkila RE, Hess A, Duvoisin RC. Dopaminergic neurotoxicity of 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,5,6-tetrahydropyridine in mice. Science. 1984;224(4656):1451–1453. doi: 10.1126/science.6610213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Przedborski S, et al. The parkinsonian toxin MPTP: action and mechanism. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2000;16(2):135–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson L, Yang Q, Szustakowski JD, Gullicksen PS, Halse R. Pyruvate induces mitochondrial biogenesis by a PGC-1 alpha-independent mechanism. Am J Physiol, Cell Physiol. 2007;292(5):C1599–C1605. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00428.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ungerstedt U. 6-Hydroxy-dopamine induced degeneration of central monoamine neurons. Eur J Pharmacol. 1968;5(1):107–110. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(68)90164-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.He Y, Lee T, Leong SK. Time course of dopaminergic cell death and changes in iron, ferritin and transferrin levels in the rat substantia nigra after 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) lesioning. Free Radic Res. 1999;31(2):103–112. doi: 10.1080/10715769900301611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harms AS, et al. Delayed dominant-negative TNF gene therapy halts progressive loss of nigral dopaminergic neurons in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease. Mol Ther. 2011;19(1):46–52. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yuan WJ, et al. Neuroprotective effects of edaravone-administration on 6-OHDA-treated dopaminergic neurons. BMC Neurosci. 2008;9:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-9-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Braak H, Del Tredici K. Potential pathways of abnormal tau and α-synuclein dissemination in sporadic Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2016;8(11):a023630. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a023630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coulom H, Birman S. Chronic exposure to rotenone models sporadic Parkinson’s disease in Drosophila melanogaster. J Neurosci. 2004;24(48):10993–10998. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2993-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boyd PJ, et al. Bioenergetic status modulates motor neuron vulnerability and pathogenesis in a zebrafish model of spinal muscular atrophy. PLoS Genet. 2017;13(4):e1006744. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clark IE, et al. Drosophila pink1 is required for mitochondrial function and interacts genetically with parkin. Nature. 2006;441(7097):1162–1166. doi: 10.1038/nature04779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsai PI, et al. PINK1 Phosphorylates MIC60/Mitofilin to Control Structural Plasticity of Mitochondrial Crista Junctions. Mol Cell. 2018;69(5):744–756.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yun J, et al. Loss-of-function analysis suggests that Omi/HtrA2 is not an essential component of the PINK1/PARKIN pathway in vivo. J Neurosci. 2008;28(53):14500–14510. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5141-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee SB, Kim W, Lee S, Chung J. Loss of LRRK2/PARK8 induces degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in Drosophila. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;358(2):534–539. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.04.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zimprich A, et al. Mutations in LRRK2 cause autosomal-dominant parkinsonism with pleomorphic pathology. Neuron. 2004;44(4):601–607. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spillantini MG, Crowther RA, Jakes R, Hasegawa M, Goedert M. alpha-Synuclein in filamentous inclusions of Lewy bodies from Parkinson’s disease and dementia with lewy bodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(11):6469–6473. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rockenstein E, et al. Differential neuropathological alterations in transgenic mice expressing alpha-synuclein from the platelet-derived growth factor and Thy-1 promoters. J Neurosci Res. 2002;68(5):568–578. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lill CM. Genetics of Parkinson’s disease. Mol Cell Probes. 2016;30(6):386–396. doi: 10.1016/j.mcp.2016.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nguyen HN, et al. LRRK2 mutant iPSC-derived DA neurons demonstrate increased susceptibility to oxidative stress. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8(3):267–280. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Driver JA, Logroscino G, Gaziano JM, Kurth T. Incidence and remaining lifetime risk of Parkinson disease in advanced age. Neurology. 2009;72(5):432–438. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000341769.50075.bb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goetz CG, et al. Movement Disorder Society-sponsored revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS): scale presentation and clinimetric testing results. Mov Disord. 2008;23(15):2129–2170. doi: 10.1002/mds.22340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang S, et al. Insulin and mTOR pathway regulate HDAC3-mediated deacetylation and activation of PGK1. PLoS Biol. 2015;13(9):e1002243. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zanon A, Pramstaller PP, Hicks AA, Pichler I. Environmental and genetic variables influencing mitochondrial health and Parkinson’s disease penetrance. Parkinsons Dis. 2018;2018:8684906. doi: 10.1155/2018/8684906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Patel A, et al. ATP as a biological hydrotrope. Science. 2017;356(6339):753–756. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf6846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hayes MH, Peuchen EH, Dovichi NJ, Weeks DL. Dual roles for ATP in the regulation of phase separated protein aggregates in Xenopus oocyte nucleoli. Elife. 2018;7:e35224. doi: 10.7554/eLife.35224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dawson TM, Golde TE, Lagier-Tourenne C. Animal models of neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Neurosci. 2018;21(10):1370–1379. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0236-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dong Z, Wang Z, Yang K, Liu Y, Gao W, Chen W. Tamsulosin versus terazosin for benign prostatic hyperplasia: a systematic review. Syst Biol Reprod Med. 2009;55(4):129–136. doi: 10.3109/19396360902833235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kirk JK, Konen JC, Shihabi Z, Rocco MV, Summerson JH. Effects of terazosin on glycemic control, cholesterol, and microalbuminuria in patients with non–insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and hypertension. Am J Ther. 1996;3(9):616–621. doi: 10.1097/00045391-199609000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shionoiri H, et al. Long-term therapy with terazosin may improve glucose and lipid metabolism in hypertensives: a multicenter prospective study. Am J Med Sci. 1994;307(Suppl 1):S91–S95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boyda HN, Procyshyn RM, Pang CC, Barr AM. Peripheral adrenoceptors: the impetus behind glucose dysregulation and insulin resistance. J Neuroendocrinol. 2013;25(3):217–228. doi: 10.1111/jne.12002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sakaue S, et al. Early-onset parkinsonism in a pedigree with phosphoglycerate kinase deficiency and a heterozygous carrier: do PGK-1 mutations contribute to vulnerability to parkinsonism? NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 2017;3:13. doi: 10.1038/s41531-017-0014-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sotiriou E, Greene P, Krishna S, Hirano M, DiMauro S. Myopathy and parkinsonism in phosphoglycerate kinase deficiency. Muscle Nerve. 2010;41(5):707–710. doi: 10.1002/mus.21612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wooten GF, Currie LJ, Bovbjerg VE, Lee JK, Patrie J. Are men at greater risk for Parkinson’s disease than women? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75(4):637–639. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.020982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yao J, Irwin RW, Zhao L, Nilsen J, Hamilton RT, Brinton RD. Mitochondrial bioenergetic deficit precedes Alzheimer’s pathology in female mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(34):14670–14675. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903563106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.