Abstract

Optimization of host-cell production systems with improved yield and production reliability is desired in order to meet the increasing demand for biologics with complex post-translational modifications. Aggregation of suspension-adapted mammalian cells remains a significant problem that can limit the cellular density and per volume yield of bio-reactors. Here, we propose a genetically encoded technology that directs the synthesis of anti-adhesive and protective coatings on the cellular surface. Inspired by the natural ability of mucin glycoproteins to resist cellular adhesion and hydrate and protect cell and tissue surfaces, we genetically encode new cell-surface coatings through the fusion of engineered mucin domains to synthetic transmembrane anchors. Combined with appropriate expression systems, the mucin coating technology directs the assembly of thick, highly hydrated barriers to strongly mitigate cell aggregation and protect cells in suspension against fluid shear stresses. The coating technology is demonstrated on suspension adapted human 293-F cells, which resist clumping even in media formulations that otherwise would induce extreme cell aggregation and show improved performance over commercially available anti-clumping agent. The stable biopolymer coatings do not show deleterious effects on cell proliferation rate, efficiency of transient transfection with cDNAs, or recombinant protein expression. Overall, our mucin coating technology and engineered cell lines have the potential to improve the single-cell growth and viability of suspended cells in bioreactors.

Keywords: synthetic biology, bioprocess

Introduction

Protein therapeutic agents represent a large and rapidly growing portion of the pharmaceutical market (Dumont, Euwart, Mei, Estes, & Kshirsagar, 2016). Current biologics enable the treatment of a wide variety of human diseases, including cancer, autoimmune disorders, and infectious diseases (Carter, 2011; Leader, Baca, & Golan, 2008). The commercial success of biologics has been a major impetus for the development of improved manufacturing technologies that reliably produce the biological agents on a large scale.

The majority of all recombinant protein pharmaceuticals are produced in mammalian cells at present (F. M. Wurm, 2004). Mammalian cells are preferred over prokaryotic organisms for production of protein therapeutics because eukaryote-specific post-translational modifications are often required for protein functionality and appropriate pharmacokinetics. As an example, monoclonal antibodies, a major class of protein therapeutics, must be post-translationally modified with sugar structures called glycans in a post-translational modification process called glycosylation (Shukla & Thömmes, 2010; Zhu, 2012). Without glycosylation, therapeutic antibodies typically have poor stability and pharmacokinetics in vivo.

Today, the majority of all recombinant protein pharmaceuticals are produced in the mammalian Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO) cell line. However, a significant drawback CHO cells for bio-manufacturing is their capacity to generate glycans that are not native to humans (Ghaderi, Zhang, Hurtado-Ziola, & Varki, 2012). These glycans can produce deleterious immune responses and have been implicated in therapeutic resistance, which remains a significant concern for physicians and patients (Casademunt et al., 2012). The risk of patient immune responses from CHO-derived products has motivated a deeper consideration of the use of human cell lines for manufacturing recombinant protein therapies (Sandberg et al., 2012).

Suspension adapted human embryonic kidney 293 cells (293-F) have become the most popular host cell line for the production of biological therapeutics with human glycosylation patterns (Casademunt et al., 2012; Vink, Oudshoorn-Dickmann, Roza, Reitsma, & de Jong, 2014). The 293-F cell system has several desirable features for recombinant protein production, including a fast proliferation rate, a high level of protein production, and ease of transient transfection (Casademunt et al., 2012; Durocher, Perret, & Kamen, 2002; Swiech et al., 2011; F. Wurm & Bernard, 1999). Recently, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved several therapeutic agents produced in 293-F cells (Dumont et al., 2016). However, compared to CHO-cell systems, 293-F cells can exhibit a higher propensity to form large aggregates in suspension, limiting their yield and reliability for bio-manufacturing (F. Wurm & Bernard, 1999). While special medium formulations have been developed to reduce cell clumping (Tolbert et al.; Peshwa et al.; Zanghi et al.; Han et al.), aggregation continues to be a challenge for mammalian suspension cell culture, especially at the high cell densities required for fast, high-yield protein production (Liu & Goudar, 2013). Exogenous addition of anti-clumping agents also introduces additional molecules that must be purified away from secreted protein products (Dee et al.; Tsao et al.; Li et al.; Park et al.). An alternative strategy would be to genetically engineer production cells to have reduced adhesion, but few approaches have been developed at the current time.

A naturally occurring family of biopolymers called mucins are utilized in nature to reduce adhesion and fouling at biological interfaces. Mucins are characterized by amino acid sequences rich in serine and threonine residues, which are post-translationally modified with O-linked pendant glycan structures (Thornton, Rousseau, & McGuckin, 2008). The bottlebrush molecular structure of mucins confers an anti-adhesive characteristic that is exploited in biological systems for diverse purposes, including antifouling coatings, lubrication, and modulation of cellular interactions (Jay & Waller, 2014; Kuo, Gandhi, Zia, & Paszek, 2018; Paszek et al., 2014). Of the mucin family members, Mucin-1 (Muc1) has long been recognized as an anti-adhesive protein that can interfere with integrin- and cadherin-mediated cell interactions (Klinken, Dekker, Buller, & Einerhand, 1995; Wesseling, Valk, & Hilkens, 1996; Wesseling, van der Valk, Vos, Sonnenberg, & Hilkens, 1995). The anti-adhesive properties of Mucl are conferred by its large ectodomain, which is heavily O-glycosylated during trafficking to the cell surface. Neutral and anionic sugar residues of the glycans can coordinate with water to form a highly hydrated barrier on the cell surface (Gendler & Spicer, 1995).

In this work, we construct semi-synthetic mucin cDNAs to create a genetically-encoded technology for reduction of aggregation of human-cell host production systems. The work builds from and extends our previous work in developing a method for stable expression of native and engineered mucins on the cell surface (Shurer et al., 2017). Here, the mucin technology is further developed, tested, and refined specifically for use as an anti-adhesive coating on host-cell production systems. As a demonstration of concept, we develop new 293-F cell lines with stable anti-adhesive coatings and evaluate their performance in regards to proliferation rate, cell aggregation, resistance to shear stress, and efficiency of transfection with plasmid DNA.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies and Reagents

The following antibodies were used: Human CD227 (555925, BD Biosciences) (Muc1), β-Actin (sc-4778, Santa Cruz), Goat anti-Mouse IgG-HRP (sc-2005, Santa Cruz). Lectins used were: Biotinylated Peanut Agglutinin (PNA; B-1075, Vector Laboratories), CF568 PNA (29061, Biotium), CF640R PNA (29063, Biotium), CF633 Wheat Germ Agglutinin (WGA; 29024, Biotium). Biotinylated lectins were detected using ExtrAvidin-Peroxidase (E2886, Sigma). To induce transactivator cell lines, doxycycline was used (sc-204734, Santa Cruz). For gentamycin selection, G418 was used (10131035, Thermo Fisher).

Constructs

A tetracycline-inducible, transposon based Piggybac expression vector with an integrated, co-expressed reverse tetracycline transactivator gene (pPB tet rtTA NeoR) was used for stable line generation (kindly provided by Dr. Valerie Weaver, University of California San Francisco, USA). The pPB tet rtTA NeoR plasmid was modified by the insertion of the internal ribosome entry site (IRES) of the encephalomyocarditis virus followed by the fluorescent protein copGFP into the NotI and XbaI sites (pPB tet IRES GFP rtTA NeoR). Synthetic cDNAs containing either 21 or 42 tandem repeats (TR) of the amino acid sequence PDTRPAPGSTAPPAHGVTSA were codon optimized with codon scrambler (Tang & Chilkoti, 2016), generated through custom gene synthesis (General Biosystems), and cloned in place of the native tandem repeats in pcDNA3.1 Muc1 TM21 – previously described in (Paszek et al., 2014; Shurer et al., 2017) – using the BamHI and Bsu36I restriction sites. The Muc1 gene containing the engineered 21 or 42 tandem repeats was then cloned into the pPB tet IRES GFP rtTA NeoR plasmid using the BamHI and EcoRI sites to generate Muc1 42TR TM21 pPB tet IRES GFP rtTA NeoR and Muc1 21TR TM21 pPB tet IRES GFP rtTA NeoR plasmids used to make the Mucin-270 and Mucin-135 biopolymer cell lines, respectively. To produce the Mucin-0 cell line, the native Muc1 tandem repeats were deleted from the pcDNA3.1 Muc1 TM21 through Q5 site directed mutagenesis with 5’-TGGAGGAGCCTCAGGCATACTTTATTG-3’ (forward) and 5’-CCACCGCCGACCGAGGTGACATCCTG-3’ (reverse) primers. The Muc1 gene with 0TR was then cut from the pcDNA3.1 Muc1 0TR TM21 and cloned into the pPB tet IRES GFP rtTA NeoR plasmid via the BamHI and EcoRI sites. The plasmid pLV puro mRuby2 was used for transient transfection experiments with cytoplasmic red fluorescent protein (RFP). For secreted RFP experiments, SS-mScarlet-I pPB tet IRES GFP rtTA NeoR plasmid was used. To construct this plasmid, the backbone was linearized using BamHI-HF and EcoRI-HF. A dsDNA oligo encoding the Muc1 signal sequence (MTPGTQSPFFLLLLLTVLTVVTGS) fused by a GGGGS linker to mScarlet-I was ordered from Integrated DNA Technologies. This fragment was inserted into the linearized backbone via NEB HiFi Assembly.

Cell Lines and Culture

FreeStyle 293-F Cells were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Cells were cultured and maintained according to the manufacturer’s guidelines in an Eppendorf New Brunswick s41i incubator in Erlenmeyer flasks. Cells were maintained between 0.5 × 106 and 3 × 106 cells/mL at 120 rpm, 37oC, and 8% CO2 in FreeStyle 293 Expression Medium (Thermo). Transfections were performed using polyethyleneimine (PEI) as previously reported (Durocher et al., 2002). Genetically-encoded stable cell lines were created by co-transfection of the pPB tet IRES GFP rtTA NeoR plasmids described above with a hyperactive transposase plasmid (Shurer et al., 2017) and subsequently selected with 750 μg/mL of gentamycin for two weeks. Cell proliferation was quantified by cell counting on a hemocytometer with trypan blue exclusion.

Confocal Microscopy

Samples were collected, pelleted at 200 rcf for 5 min, and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature. Samples were washed three times with PBS. Cells were labeled with 1:1000 CF568 PNA for O-glycans and 1:1000 CF633 WGA for the cell membrane in PBS for 30 minutes at room temperature. Samples were washed three times with PBS and imaged on a Zeiss LSM800 with a 63x water immersion objective.

Flow Cytometry Analysis

All samples were measured using live cells, unless otherwise indicated. Cells were harvested from suspension culture, pelleted at 200 rcf for 5 min, and resuspended in 0.5% BSA PBS. Samples were filtered through a 0.22 μm filter cap and analyzed on a BD FACS Aria Fusion. For the doxycycline time-course, cells were induced with 1 μg/mL of doxycycline. Cellular samples from the cultures were taken at the indicated time points, pelleted at 200 rcf for 5 min, and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature. Samples were rinsed three times with PBS and stored at 4oC until flow cytometry analysis. Analysis of all flow cytometry data was performed using FlowJo software.

Immuno- and Lectin Blot Analysis

Cells are inoculated at 0.5 × 106 cells/mL and grown overnight, 16–18 hr. Biopolymer expression was then induced with 1 μg/mL doxycycline, and cells were grown with doxycycline for an additional 48 hr. After 48 hr, a sample was taken for each cell line, pelleted at 200 rcf for 5 min before the supernatant was separated, and the cell pellet was lysed by resuspending in RIPA lysis buffer (Abcam), vortexing the sample for 30 seconds, and heating to 98oC for 10 min. Lysates were frozen on liquid nitrogen and stored at −80oC. Lysates were separated on Nupage 3–8% Tris-Acetate gels (Invitrogen) and transferred to PVDF membranes. Membranes were blocked with 3% BSA TBST for 2 hr. Primary antibodies were diluted 1:1000 and lectins were diluted to 1 μg/mL in 3% BSA TBST and incubated on membranes overnight at 4oC. Secondary antibodies or ExtrAvidin were diluted 1:2000 in 3% BSA TBST and incubated for 2 hr at room temperature. Blots were developed in Clarity ECL (BioRad) substrate and imaged on a ChemiDoc (BioRad) documentation system.

PCR amplification of Mucin-270 transgene in the transfected 293F cells

To test for amplification or deletion of stably integrated Mucin-270 cDNAs in 293F genomes, PCR amplification was performed with Q5 Hot start high-fidelity DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs Inc., Ipswich, MA) using extracted genomic DNA as the template. Genomic DNA was extracted with GeneJET genomic DNA purification kit (Thermo Scientific., Waltham, MA). A total of 60 ng of genomic DNA was used for PCR amplification. Primers: Mucin-270 FWD 5’-ATGACACCGGGCACCCAGTC-3’ and Mucin-270 REV 5’-CTACATACTTCGTCGGCGCATGTAC-3’. Size of amplicon is 2994 bp.

Cell Clumping Analysis

Cells were inoculated at 0.75 × 106 cells/mL and induced with 1 μg/mL doxycycline after overnight growth (16–18 hr). Cells were then grown to a high cell density for an additional 48 or 72 hr in the presence of 1 μ/mL doxycycline. Cell density was quantified by collecting sample of the culture, mixing thoroughly to dissociate large clumps, and counting viable cells with a hemocytometer and trypan blue exclusion. For imaging, samples were drawn with wide-bore pipette tips to reduce dissociation of large clumps and diluted in PBS to approximately 6.75 × 104 cells/cm2 for imaging in 2D. Phase contrast images were acquired on an Olympus IX81 microscope with a 10x objective. Fiji was used for image processing (Schindelin et al., 2012). Two independent samples were collected and prepared as technical replicates for imaging with three regions of interest imaged per technical replicate. Three biological replicates were performed. Automated image analysis was performed using custom analysis software adapted from a previous publication (Shurer et al., 2017). Briefly, the analysis software located the center of each circular object. The coordinates of each cell’s center were then used to calculate the Ripley’s K function in MATLAB. The percent of single cells was calculated by counting the total number of cells which do not have any neighboring cells within 19 μm and dividing by the total number of cells in the image. Similarly, the percent of cells in various cluster sizes was calculated by binning the cells into clusters based on the number of neighboring cells within 19 μm.

To evaluate resistance to calcium induced cell aggregation, cultures were inoculated at 0.5 × 106 cells/mL and induced with 1 μg/mL doxycycline after overnight growth (16–18 hr). After 48 hr, cells were resuspended at 4 × 106 cells/mL. The culture media was then supplemented with 2 mM CaCl2, 1:300 anti-clumping agent (Thermo Fisher, 0010057AE), or both. Still images and videos of the cell suspension were acquired after 24 hr of treatment by transferring the culture to a glass test tube. The concentration of cells in suspension was determined by collecting duplicate samples from each culture after allowing the largest aggregates to settle out of suspension for 20 seconds. Cell concentration was measured using a hemocytometer and Trypan blue.

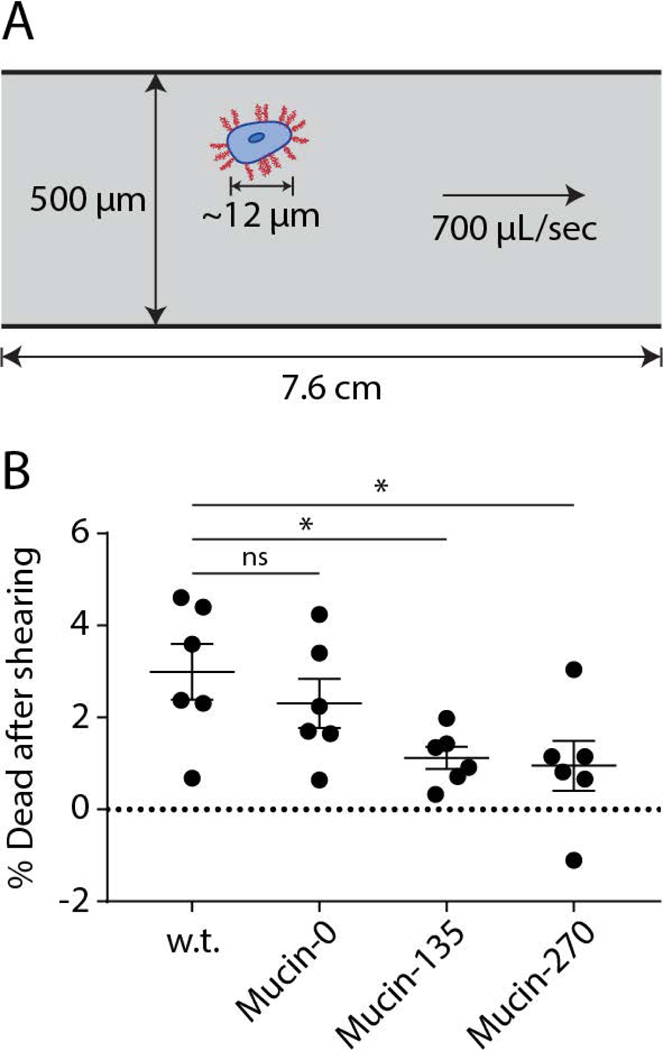

Shear Stress Experiments

Cells were inoculated at 0.5 × 106 cells/mL, grown overnight (16–18 hr), and induced with 1 μg/mL doxycycline for 48 hr. Using a 5 mL syringe with a 16-gauge needle connected to 6.5 in of 1.02 mm silicon tubing, cell suspensions were sheared by flowing through a 500 μm constriction (Teflon tubing) at a constant force generated by a 1 kg mass applied to a syringe with gravity. Samples were passed through the constriction five times. Cells were then stained with 1 μg/mL CF640R PNA for 15 min at 4oC. Cells were washed with 0.5% BSA PBS three times and then stained with Ethidium homodimer-1 (dead cell stain, Thermo Fisher, L3224). Three biological replicates were performed, with two technical replicates for each biological replicate. Percent dead cells was determined by measuring the fraction of cells that had taken up the dead cell stain on a BD FACS Aria Fusion. A control sample without shear was used to subtract background cell death for each cell line. For Mucin-135 and Mucin-270 cell lines, only PNA positive cells were considered for analysis. Data analysis was performed using FlowJo software.

Transfection Experiments

Cells were inoculated at 0.5 × 106 cells/mL, grown overnight (16–18 hr), and induced with 1 μg/mL doxycycline for 48 hr. Cells were then diluted to 2 × 106 cells/mL in fresh medium containing 1 μg/mL doxycycline and transfected with 1 μg DNA per 106 cells. The next day (16–18 hr post-transfection), cells were diluted 1:1 with fresh medium containing 1 μg/mL doxycycline. To measure transfection efficiency, cells were transfected with the pLV puro mRuby2 plasmid and transfection efficiency was calculated by flow cytometry as the fraction of cells expressing RFP 72 hr post transfection. For production and secretion of recombinant RFP, cells were transfected with SS-mScarlet-I pPB tet IRES GFP rtTA NeoR. After 24 hr, secreted RFP fluorescence in the media supernatant was quantified using a Tecan M1000 Pro plate reader.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical significance was determined by ordinary one-way ANOVA or Student’s t test (two-tailed) as appropriate using Prism (GraphPad). All graphs were generated in Prism (Graphpad) except for boxplot which were generated in R.

Results

Genetically-Encoded Biopolymers Expressed on the Surface of 293-F Cell Lines

Drawing inspiration from the anti-adhesive properties of naturally occurring mucins, we created cDNAs that encoded Muc1-like biopolymers with transmembrane domains for anchorage to the cell surface. The biopolymer domains consisted of an unstructured protein backbone with 0 – 42 perfect repeats of PDTRPAPGSTAPPAHGVTSA, which is recognized by the O-glycosylation machinery of the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus and heavily glycosylated while trafficked to the cell surface. Each biopolymer was targeted to the extracellular space by the native Muc1 signal sequence. The biopolymers were anchored to the cell membrane with a 21-amino acid transmembrane domain (Mercanti et al., 2010; C. R. Shurer et al., 2017). By replacing the native autocatalytic domain of Muc1 (Levitin et al., 2005) with the engineered 21-amino acid transmembrane domain, we mitigated the risk of ectodomain shedding from the cell surface. Our engineered constructs also lacked a cytoplasmic tail to avoid inadvertent transduction of biochemical or physical stimuli by the mucins.

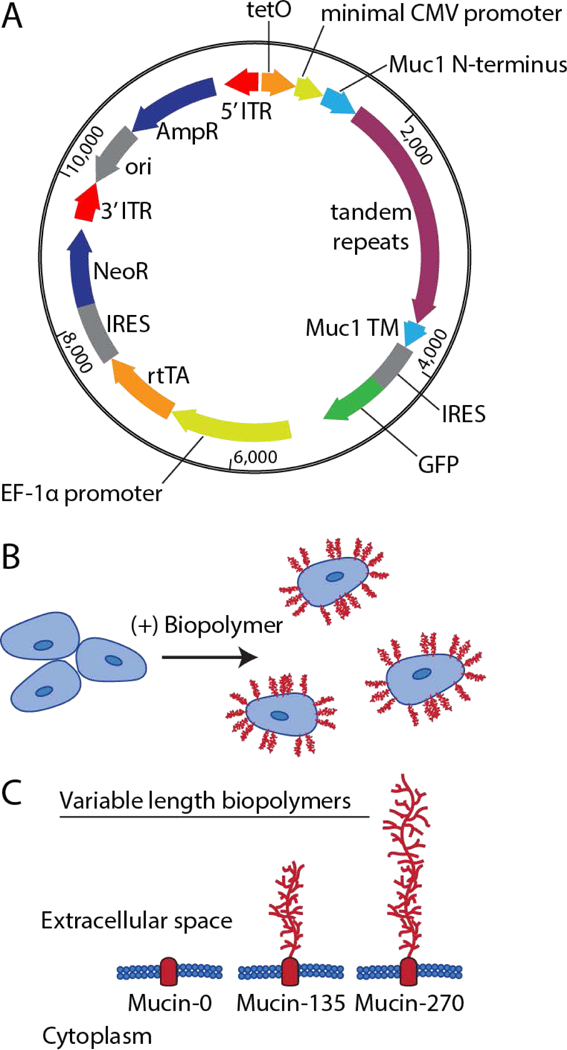

The genetic modification of the 293-F cell line was performed non-virally with an “all-in-one plasmid” that contained all necessary elements for selection and tetracycline-inducible expression (Fig. 1A). The vector included a tetracycline-responsive promoter for expression of the biopolymer coating and an additional cassette for constitutive expression of the reverse tetracycline transactivator (rtTA-M2) and neomycin-resistance gene (Gossen, Bender, Muller, al, & Freundlieb, 1995). A bicistronic green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter was also included for visual confirmation of transcription of the mucin cDNA. The cDNA for the biopolymers was stably incorporated into the genome at random locations by transposon mediated integration (X. Li et al., 2013; Wilson, Coates, & George, 2007; Woodard & Wilson, 2015). This approach avoided the use of any viral technology, which poses a serious safety concern in bio-manufacturing (Dumont et al., 2016). We hypothesized that the modified cells would be coated with a dense, inducible layer of mucin biopolymers on their surface (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1 – Engineering Biopolymer-Coated Cell Lines.

A transposon-based method was used to stably integrate the DNA encoding the engineered biopolymers under a doxycycline inducible promoter. A, Schematic representation of the all-in-one vector used for producing biopolymer-coated cell lines showing key elements. For incorporation into the cellular genome, the vector includes a tetracycline responsive element (tetO), a minimal CMV promoter, the Muc1 signal sequence (Muc1 N-terminus), the tandem repeats of the biopolymer (0, 21, or 42 repeats of PDTRPAPGSTAPPAHGVTSA), the transmembrane domain of Muc1 (Muc1 TM), the bicistronic green fluorescent protein reporter (IRES GFP), a EF-1α promoter, the reverse tetracycline transactivator (rtTA), and a second bicistronic neomycin resistance cassette (IRES NeoR). These elements were all flanked by 5’ and 3’ inverted terminal repeat sequences (ITRs) required for transposon-mediated incorporation into the genome. For vector replication and production in bacteria, there was also an ampicillin resistance cassette (AmpR) and an origin of replication (ori). B, Schematic representation of membrane bound biopolymers expressed by the cells and localized to the cells surface. C, Schematic of the relative size of the extracellular domain of the engineered biopolymers designated Mucin-0, Mucin-135, and Mucin-270 for their respective length in nm. The predicted molecular weight of these proteins was 42 kDa, 81 kDa, and 120 kDa, respectively.

We tested three different biopolymers size for their effects on 293-F cell aggregation. Mucin-like genes with 0, 21, and 42 tandem repeats were constructed. The contour lengths of the polymers with 21 and 42 repeats were predicted to be 135 nm and 270 nm, respectively. We therefore designated the biopolymers Mucin-0, Mucin-135, and Mucin-270 based on the relative length of the biopolymer (Fig. 1C). Because it lacks the large, glycosylated biopolymer domain, the Mucin-0 construct served as a control for any effects related to expression of the transmembrane anchor of the biopolymer.

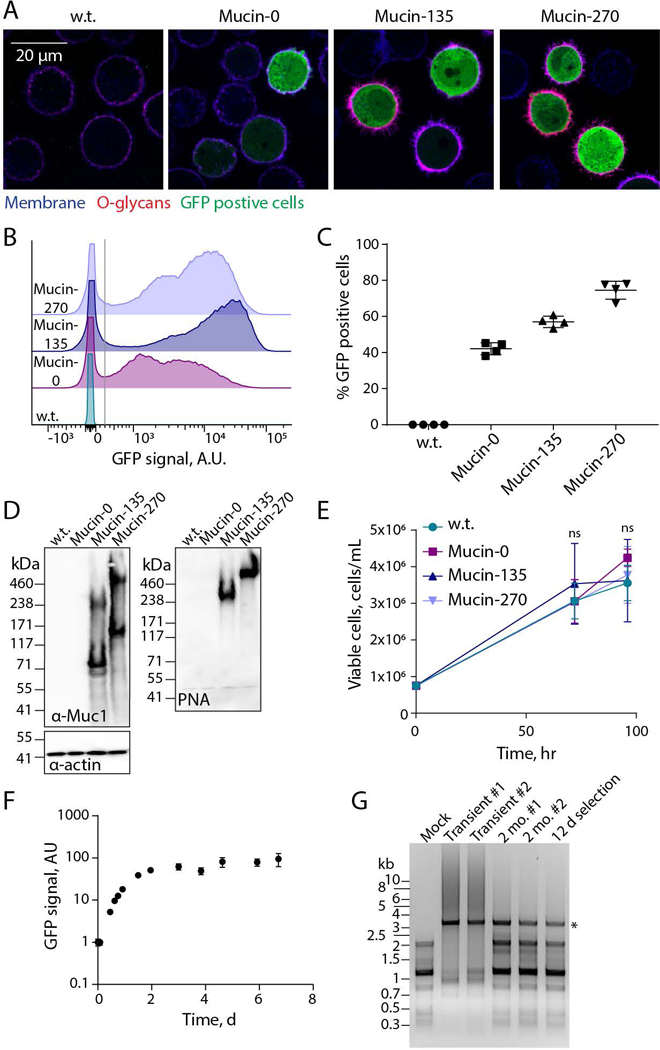

We confirmed the expression and localization of the biopolymers to the cell surface. Fluorescent microscopy showed expression of the cDNA, reported by the bicistronic GFP signal, and the presence of O-glycans on the membrane of cells expressing the Mucin-135 and Mucin-270 semi-synthetic genes (Fig. 2A). We observed a large distribution of biopolymer expression levels, which we attributed to the randomized transposition of the cDNAs into the genome (Fig. 2B). Despite the broad distribution, a large portion of the cell populations had stably integrated the cDNA, as shown by the GFP reporter (Fig. 2A–C). The expression and size of the biopolymers was further validated by Western blot (Fig. 2D). Both the Mucin-135 and Mucin-270 could be probed with antibodies against the native Muc1 tandem repeats (Fig. 2D, left). Wild-type (w.t.) cells had no detectable level of endogenous Muc1 expression and no significant O-linked mucin-like glycosylation (Fig. 2D). The Mucin-135 and Mucin-270 were heavily glycosylated when expressed. This is shown by the protein bands which are detected above the protein sequence molecular weight when probing with anti-Muc1 antibodies (Fig. 2D, left; predicted molecular weights 81 kDa and 120 kDa for Mucin-135 and Mucin-270, respectively). O-glycosylation is further demonstrated by the detection of the biopolymer with PNA which binds specifically to O-linked glycans such as those found on Muc1 (Fig. 2D, right).

Figure 2 – Validation of Biopolymer Coatings.

Expression and cell-surface localization of biopolymer coatings was validated for the new, engineered 293-F cell lines. A, Representative confocal microscopy images of stable suspension adapted human embryonic kidney 293 (293-F) cell lines – wild type (w.t.), or stably expressing the Mucin-0, Mucin-135, or Mucin-270 biopolymer. Images show the cell membrane (shown in blue, CF633 Wheat Germ Agglutinin, WGA), O-glycans covalently attached to the Mucin-135 and Mucin-270 biopolymers (shown in red, CF568 Peanut Agglutinin, PNA), and green-fluorescent protein (shown in green, GFP) which is co-expressed on the plasmid with the Mucin-0, Mucin-135 and Mucin-270 biopolymer. B, Representative flow cytometry histograms showing the polydisperse population of biopolymer expressing cell lines compared to w.t. cells, y-axis is scaled to show the population distribution of GFP positive cells. >50,000 cells per histogram. C, Quantification of the percent of cells which are GFP positive for each cell line. Cells with GFP signal above the gray line in Fig. 2B were considered GFP positive. Mean and S.D. are shown, >50,000 cells per sample, n = 4. D, Representative immunoblot (left) and lectin blot (right) of whole cell lysates for each generated stable cell line compared to w.t. cells, n = 3. E, Viable cell concentration determined by hemocytometer counting with trypan blue exclusion, n = 3. F, GFP signal of Mucin-270 cells after induction of expression at t = 0 hr, measured by flow cytometry, n = 3, >15,000 cells per sample. G, Agarose gel showing polymerase chain reaction (PCR) product of Mucin-270 gene from DNA extracted from non-transfected cells (Mock), w.t. cells transiently transfected (Transient), or cells with the Mucin-270 gene incorporated in the genome and cultured for 2 months (2 mo.) or 12 days (12 d) after gentamycin selection. Star indicates the predicted molecular weight of Mucin-270 PCR product. #1 and #2 are biological replicates. Mean and S.D. shown, ns – not significant.

No significant difference in cell proliferation rate was observed for any of our biopolymer-coated cell lines (Fig. 2E). We concluded that the additional protein load of our biopolymers did not adversely affect the rapid growth rate of parental 293-F cells. For our stable cell line, we used the well characterized reverse-tetracycline inducible promoter (Gossen et al., 1995) which initiates gene transcription upon addition of doxycycline and halts transcription on withdrawal of doxycycline. Our cell line responded as predicted to induction by doxycycline, demonstrating temporal control over expression of the mucin coating (Fig. 2F).

Highly repetitive cDNAs, such as mucins, are reported to have higher frequencies of amplification and deletion in the cellular genome (Gemayel, Vinces, Legendre, & Verstrepen, 2010; Oren et al., 2016). The cDNAs for our Mucin-135 and Mucin-270 constructs were codon optimized to minimize their repetitiveness. We found that the optimized cDNAs were stable when integrated in the host cell genome. Notably, no noticeable amplification or deletion of stably integrated Mucin-270, the largest and most repetitive of our biopolymer cDNAs, was observed after 2 months of cell culture (Fig. 2G).

Biopolymer Coatings Reduced Cell Aggregation

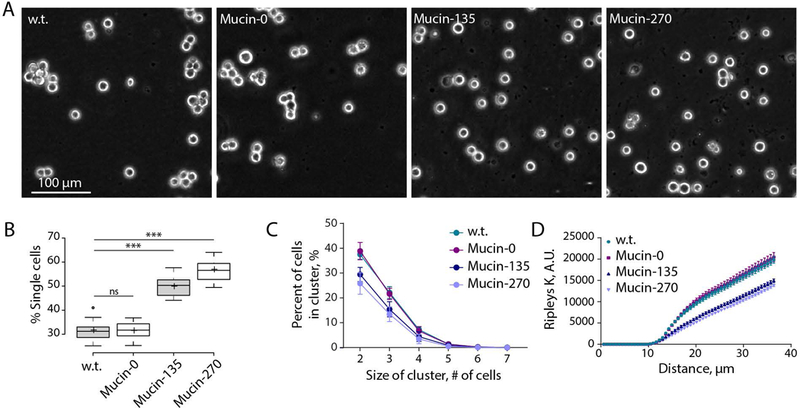

After establishing our stable populations, we set out to determine if the biopolymer coatings could reduce cell aggregation in suspension cell cultures. Phase contrast images of the cell lines qualitatively showed more cell aggregates in the w.t. and Mucin-0 cell lines than in the Mucin-135 and Mucin-270 lines (Fig. 3A). Quantification of the fraction of single cells in the sample showed an increase in the percent of single cells for the Mucin-135 and Mucin-270 coatings compared to the w.t. cells, while the Mucin-0 line showed no difference compared to w.t. cells (Fig. 3B, Supporting Fig. 1A). Correspondingly, w.t. and Mucin-0 coated cell lines were much more likely to form clusters of two or more cells than Mucin-135 or Mucin-270 cell lines (Fig. 3C, Supporting Fig. 1B).

Figure 3 – Biopolymer Coatings Reduced Cell Aggregation.

Genetically-encoded biopolymer coatings of Mucin-135 and Mucin-270 size reduce cell aggregation in suspension cell culture. A, Representative phase contrast images for w.t. and biopolymer cell lines. Images were for cells grown at a concentration of 3.8 ± 0.7 × 106 cells/mL at 72 hr post-induction. B, Quantification of the fraction of cells in various cluster sizes from phase contrast images such as those shown in Fig. 3A, 3 biological replicate samples, 2 technical replicate samples, 3 images analyzed per sample, samples (further discussion of replicates in Materials and Methods section). Center lines show the medians; box limits indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles as determined by R software; whiskers extend 1.5 times the interquartile range from the 25th and 75th percentiles, outliers are represented by dots; crosses represent sample means. C, Quantification of the fraction of cells which are in clusters of various sizes from phase contrast images such as those shown in Fig. 3A. Mean and S.D. are shown. D, Ripleys K function versus distance calculated for the cell distribution acquired from phase contrast images such as those shown in Fig. 3A. Mean and S.E.M. are shown, replicates described in Fig. 3B. ns – not significant; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.005.

Inspection of phase contrast images of our 293-F lines engineered with Mucin-135 or Mucin-270 revealed that the majority of cells were singlets or doublets with few detectable higher order aggregates (Fig. 3B). Because of the absence of higher order aggregates, we reasoned that the doublets in the Mcuin-135 and Mucin-270 samples may be actively dividing cells or cells that have yet to full disassociate following cytokinesis. The appearance of doublets can also result from single cells randomly settling out of suspension too near each other to resolve in the 2D plane of the image formed on our microscope. To approximate the frequency of single cells which could randomly settle out of suspension in such a way, we created a simulated dataset of randomly placed centroids and conducted our clustering analysis. On average, the simulated centroids would be counted as singlets 66% of the time. By comparison, 57% of the Mucin-270 cells were singlets (Fig. 3B).

To quantify the extent of cell clustering, we analyzed the spatial distribution of cells in the image using the Ripley’s K function, a spatial distribution statistic that counts the frequency at which neighboring particles are found within a given distance of any given particle. Using this statistical tool, we observed that the Mucin-135 and Mucin-270 biopolymers show decreased clustering compared to the w.t. and Mucin-0 cell lines (Fig. 3D, Supporting Fig. 1C).

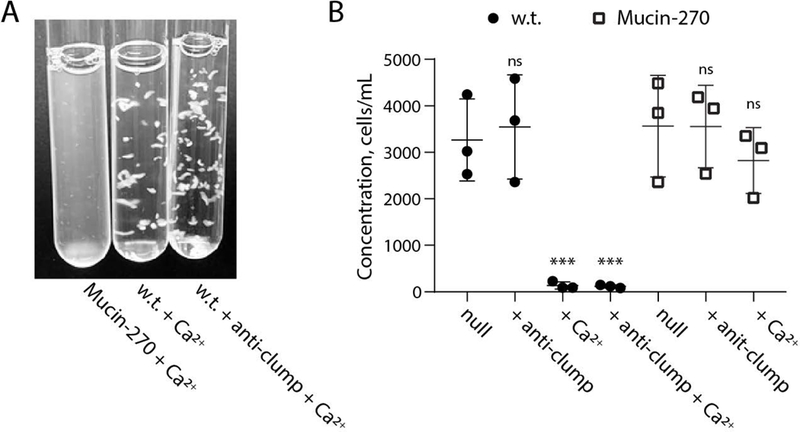

Mucin-270 Coatings Outperformed Commercially Available Anti-Clumping Agent

We found that the Mucin-270 biopolymer coating could reduce cell aggregation even in extreme pro-clumping conditions. Suspension adapted cell lines have previously been shown to significantly aggregate under specific media conditions, such as high calcium concentrations that are known to promote engagement of cadherins (Dee et al., 1997; Han et al., 2006b; Kim, Tai, Mok, Mosser, & Schuman, 2011; Meissner et al., 2001; Peshwa et al., 1993; Sjaastad & Nelson, 1997; Tolbert et al., 1980; Yamamoto et al., 2000; Zanghi et al., 2000). When cultured in high calcium conditions (2 mM CaCl2), the Mucin-270 biopolymer coated cells showed qualitatively less aggregation than w.t. cells (Fig. 4A, Supporting Movie 1). Notably, cultures with Mucin-270 biopolymer coatings retained their turbidity in the pro-clumping conditions, whereas unmodified cells assembled into large clusters easily visible to the naked eye (Fig. 4A, Supporting Movie 1). Mucin-270-coated cells show a slight decrease in concentration of cells in suspension upon calcium treatment while w.t. cells have essentially no cells remaining in suspension (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4 – Mucin-270 Reduced Aggregation in High Calcium Culture Media.

The Mucin-270 cell line out-performs commercial anti-clumping solution in highly aggregating conditions. Also see Supporting Movie 1. A, Image of Mucin-270 and w.t. cultures grown in media with 2 mM CaCl2 (+ Ca2+). Mucin-270 expression significantly decreases cell aggregation, even compared to commercially available anti-clumping reagent (+ anti-clump). B, Quantification of the concentration of w.t. or Mucin-270-expressing cells in suspension for control cultures with no treatment (null), with the addition of commercial anti-clumping reagent (+ anti-clump), with the addition of 2 mM CaCl2 (+ Ca2+), or with both anti-clumping reagent and 2 mM CaCl2 (+ anti-clump + Ca2+). Statistical comparison is to null condition for each cell line. Mean and S.D. are shown, n = 3. ns – not significant; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.005.

Further, the Mucin-270 coating outperforms a commercially available anti-clumping agent in highly aggregating conditions. Under high calcium conditions, anti-clumping agent had no discernable efficacy in mitigating cell clumping (Fig. 4A, Supporting Movie 1). Addition of commercial anti-clumping agent to Mucin-270 coated cells did not further enhance their resistance to clumping in our assays (Fig. 4B). Together, these results demonstrated the ability of our genetically-encoded biopolymer coatings to reduce cell aggregation in suspension.

Biopolymer Coatings Provided Resistance to Shear Stress

The sensitivity of suspension-adapted mammalian cells to shear stresses imposes a limit on the rate of mixing and mass transfer in typical bioreactors (Hu, Berdugo, & Chalmers, 2011). Large volume bioreactors operated at high-cell densities require increased mixing to overcome mass transfer limitations (Hu et al., 2011). Thus, cellular sensitivity to shear places another limit on bioreactor productivity. Because protection of ductal epithelial cells to shear stress is a physiological function of mucins, we considered whether, as an added benefit, our biopolymer coatings might protect cells from shear stresses. To test this possibility, suspended cells were sheared by passage through a narrow constriction and then analyzed for viability after reintroduction into culture (Fig. 5A). A 1 kg mass was applied to a vertically-oriented syringe to generate a constant and controlled pressure that drove the flow of suspended cells through a 7.6 cm length of 500 μm diameter Teflon tubing. Cell death was analyzed by flow cytometry using a live/dead cell stain. We found that the Mucin-135 and Mucin-270 biopolymer-coated cell lines had significantly greater viability after shearing compared to both w.t. and Mucin-0 cell lines (Fig. 5B), suggesting that the mucin coatings could allow for higher mixing rates in the bioreactor, although this possibility was not directly tested.

Figure 5 – Biopolymer Coating Enhanced Resistance to Shear Stresses.

Expression of the stably incorporated biopolymers protects cells from shear stresses. A, Schematic representation of the experimental setup for shearing cells. Briefly, cells were sheared by flowing through a 500 μm Teflon tube under a constant applied force of 1 kg in gravity before being analyzed by flow cytometry with a live/dead cell stain. B, Quantification of the fraction of dead cells after shearing the cells for the w.t. and biopolymer cell lines, Mean and S.E.M. are shown, > 50,000 cells measured for each population, n = 6. ns – not significant; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.005.

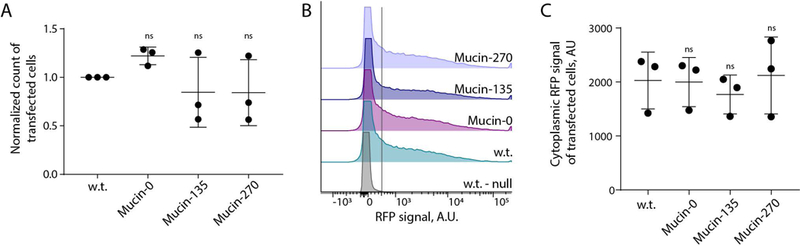

Biopolymer Coated Cell Lines can be Transiently Transfected and Produced Comparable Levels of Recombinant Protein

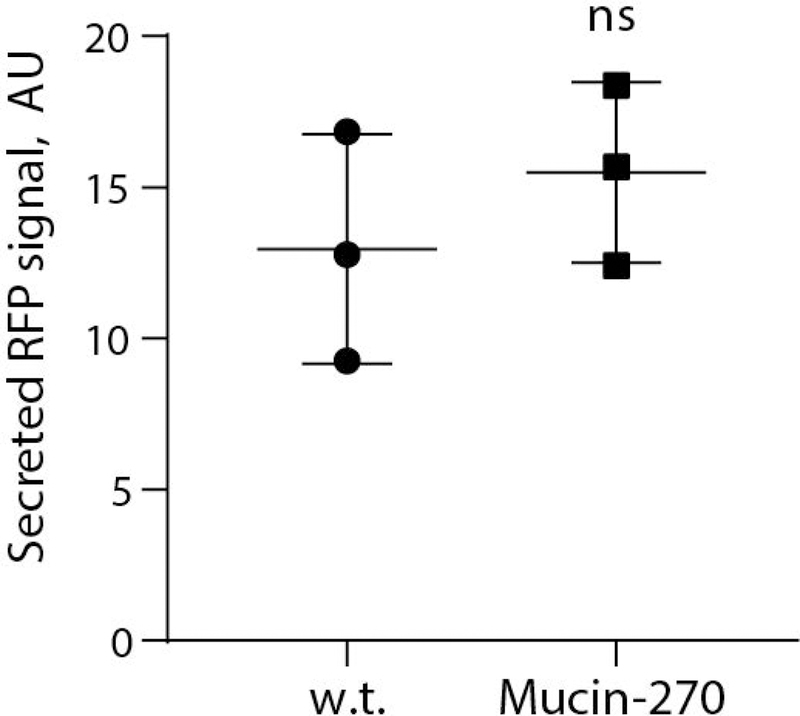

We noted that the use of transient transfection of cells for recombinant protein production has recently become of interest to avoid the long development times associated with selection and isolation of stable cell lines for production of new pharmaceuticals (Derouazi et al., 2004; Durocher et al., 2002; Swiech et al., 2011). Given the potential barrier effect of a mucopolysaccharide coating on the cell surface, we tested whether expression of our biopolymers would affect transfection efficiency of the cell lines. To test, we transiently transfected our cell lines with a plasmid for expression of cytoplasmic red-fluorescent protein. We observed no statistically significant difference in the transfection efficiency of the Mucin-0, Mucin-135, or Mucin-270 cell lines compared to the w.t. cells (Fig. 6A). Single-cell analysis revealed similar distributions of recombinant protein production across the engineered and parental cell populations (Fig. 6B). Further, there is no significant difference in the RFP signal of transfected cells, indicating comparable expression of transiently transfected proteins in the different cell lines (Fig. 6C). We also tested the performance of our engineered cells for production of secreted recombinant proteins. As a test case, we fused a signal peptide to the fluorescent protein, mScarlet-I, and measured production of the secreted protein in medium supernatant from transiently transfected cultures. Mucin-270 coated cells produced the same quantities of secreted recombinant protein as w.t. cells (Fig. 7). We concluded that the biopolymer coatings did not adversely affect transfection efficiency and high protein production rate of the 293-F cell system.

Figure 6 – Biopolymer Coated Cells can be Transfected.

Transfection was determined for the biopolymer coated cell lines by transfection with a cytoplasmic red-fluorescent protein (RFP). A, Quantification of the number of cells for w.t. and biopolymer coated cells transiently transfected with cytoplasmic RFP. The count of transfected cells was normalized to the count of w.t. cells transfected per experiment to account for variable transfection efficiency between replicate transfections. > 50,000 cells measured for each population, n = 3. B, Representative flow cytometry histogram showing the distribution of expression among transfected cell populations. The peak to the left of the gray line, centered around zero, represented the non-transfected population for each cell line which is further validated by the overlapping histogram of non-transfected w.t. cells (w.t.-null). C, Quantification of the geometric mean of RFP for positively transfected cells from B. Mean and S.D. shown, ns – not significant; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.005.

Figure 7 – Mucin-270 cells Produced Comparable Levels of Recombinant Protein Expression.

Quantification of secreted, recombinant RFP from media supernatant of w.t. or Mucin-270-expressing cultures transiently transfected with secreted RFP, n = 3. Mean and S.D. shown, ns – not significant; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.005.

Discussion

The expression of engineered biopolymer coatings shows promise as a technology for improved suspension cell culture for bio-manufacturing applications. In this work, we have shown that established cell lines can be genetically modified to express engineered mucin biopolymers for anti-adhesion. Expression of these biopolymers does not negatively impact the desirable characteristics of 293-F cells, including their fast proliferation rates (Fig. 1E) and high transfection efficiencies (Fig. 6A, B). Moreover, the expression of the biopolymers significantly reduces undesirable cell clumping (Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Supporting Fig. 1) and enhances resistance of the cells to shear forces (Fig. 5). Our Mucin-135 coating and thicker Mucin-270 coatings performed similarly in head-to-head tests and should be equally well-suited for the applications investigated in this work.

Our biopolymer coatings provide a significant reduction of cell aggregation in serum-free media formulations that are typically used for production in bioreactor formulations. Notably, our coatings could reduce aggregation further even in media formulations that were designed to minimize cell clumping (eg. Invitrogen Freestyle 293-F media). Future studies could consider the effect of biopolymer expression on cell aggregation in media formulations that have historically been avoided due to issues of cell aggregation. For example, highly efficient transient transfections have long been performed with DNA-calcium phosphate precipitates (Jordan & Wurm, 2004). However, at the high calcium concentrations required, 293-F cells are known to form large cell aggregates (Meissner et al., 2001; Peshwa et al., 1993). Based on our results (Fig. 4), use of the Mucin-135 or Mucin-270 coatings significantly reduce cell aggregation in such conditions for improved protein production from transiently transfected cultures.

Further refinement of the mucin coating technology may be achieved through additional optimization of the engineered mucins and their regulated expression. Notably, excessive over-production of highly glycosylated mucin-like proteins could possibly compete with recombinant glycoproteins for the cellular glycosylation machinery and the nucleotide sugar building blocks of glycans. Shedding of the engineered mucins from the cell surface is mitigated by our choice of membrane anchor, which lacks a proteolytic cleavage site. Nevertheless, mucin shedding from highly over-expressed surface coatings is a possibility that could present challenges during downstream product purification. Cellular clones for production should be isolated that provide the desired performance enhancements of the mucin coatings, while avoiding over-expression, which could affect downstream sample processing or compromise cellular growth, recombinant product quality, and overall productivity if too many cellular resources are dedicated to coating synthesis.

The mucin technology coating was originally conceived as a solution for suspension-adapted suspension systems that tend to aggregate in the bio-reactor. However, the ability of our coatings to protect cells and strongly resist clumping could also benefit current bio-manufacturing platforms, like CHO cells, which can still aggregate under non-ideal reactor conditions or in non-optimal media formulations. As bio-manufacturing looks beyond CHO systems for next-generation production platforms that mitigate the risk of non-human glyco-conjugates and other antigenic epitopes, adaptation to growth in suspension remains a significant and time-consuming challenge for human, primate, and many other mammalian cell lines (Amaral et al., 2016; Rodrigues et al., 2013). By promoting cell viability and minimizing aggregation, our coatings could help overcome some of the significant barriers to suspension adaptation.

Taken together, our work presents a mucin coating technology for improved single-cell growth of cells in suspension. Despite testing a relatively small number of mucin coatings, the system was largely successful in the primary goal of mitigating cell aggregation. Through future refinement and validation, the coating technology has potential as a viable solution for bio-manufacturing with cellular production systems that have desirable features, but currently remain difficult to deploy in industrial practice due to poor single-cell growth behavior in suspension.

Supplementary Material

Movie showing Mucin-270 cells (left), w.t. cells (center), and w.t. cells with commercial anti-clumping agent (right) in media containing 2 mM CaCl2. The Mucin-270 culture is more turbid than w.t. cultures with only small aggregates. Large clusters are easily observed in both the w.t. culture and w.t. with commercial anti-clumping agent culture.

Additional data to accompany Figure 3 acquired 24 hr prior. A, Quantification of the fraction of cells in various cluster sizes from phase contrast images such as those shown in Fig. 3A. Cells are grown at 3.2 ± 0.7 × 106 cells/mL for 48 hr for all panels. Center lines show the medians; box limits indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles as determined by R software; whiskers extend 1.5 times the interquartile range from the 25th and 75th percentiles, outliers are represented by dots; crosses represent sample means. B, Quantification of the fraction of cells which are in clusters of various sizes from phase contrast images such as those shown in Fig. 3A. Mean and S.D. are shown. C, Ripley’s K function versus distance calculated for the cell distribution acquired from phase contrast images such as those shown in Fig. 3A. Mean and S.E.M. are shown, replicates described in Fig. 3B, n =3,. ns – not significant; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.005.

Acknowledgements

We thank V. Weaver and J. Lakins for transposon plasmids. This investigation was supported by the National Institute of General Medicine Sciences Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award 2T32GM008267 (C.R.S.), Knight Family Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship in Nanoscience and Technology (C.R.S.), Samuel C. Fleming Family Graduate Fellowship (C.R.S.), National Institute of Health New Innovator DP2 GM229133 (M.J.P.) and National Cancer Institute U54 CA210184 (M.J.P.) and R33-CA193043 (M.J.P.). Flow cytometry was carried out at the Cornell University Biotechnology Resource Center.

Grant Numbers: NIH NIGMS 2T32GM008267; NIH DP2 GM229133; NIH NCI U54 CA210184; NIH NCI R33-CA193043

Footnotes

Competing Interests

The authors declare a potential financial interest due to a pending patent on the biopolymer sequences.

References

- Amaral RLF do, Bomfim A de S, Abreu-Neto M. S. de, Picanço-Castro V, Russo EM de S, Covas DT, & Swiech K. (2016). Approaches for recombinant human factor IX production in serum-free suspension cultures. Biotechnology Letters, 38(3), 385–394. 10.1007/s10529-015-1991-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter PJ (2011). Introduction to current and future protein therapeutics: A protein engineering perspective. Experimental Cell Research, 317(9), 1261–1269. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2011.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casademunt E, Martinelle K, Jernberg M, Winge S, Tiemeyer M, Biesert L, … Schröder C (2012). The first recombinant human coagulation factor VIII of human origin: human cell line and manufacturing characteristics. European Journal of Haematology, 89(2), 165–176. 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2012.01804.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dee KU, Shuler ML, & Wood HA (1997). Inducing single-cell suspension of BTI-TN5B1–4 insect cells: I. The use of sulfated polyanions to prevent cell aggregation and enhance recombinant protein production. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 54(3), 191–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derouazi M, Girard P, Van Tilborgh F, Iglesias K, Muller N, Bertschinger M, & Wurm FM (2004). Serum-free large-scale transient transfection of CHO cells. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 87(4), 537–545. 10.1002/bit.20161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumont J, Euwart D, Mei B, Estes S, & Kshirsagar R (2016). Human cell lines for biopharmaceutical manufacturing: history, status, and future perspectives. Critical Reviews in Biotechnology, 36(6), 1110–1122. 10.3109/07388551.2015.1084266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durocher Y, Perret S, & Kamen A (2002). High-level and high-throughput recombinant protein production by transient transfection of suspension-growing human 293-EBNA1 cells. Nucleic Acids Research, 30(2), e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gemayel R, Vinces MD, Legendre M, & Verstrepen KJ (2010). Variable tandem repeats accelerate evolution of coding and regulatory sequences. Annual Review of Genetics, 44, 445–477. 10.1146/annurev-genet-072610-155046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendler SJ, & Spicer AP (1995). Epithelial Mucin Genes. Annual Review of Physiology, 57(1), 607–634. 10.1146/annurev.ph.57.030195.003135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaderi D, Zhang M, Hurtado-Ziola N, & Varki A (2012). Production platforms for biotherapeutic glycoproteins. Occurrence, impact, and challenges of non-human sialylation. Biotechnology & Genetic Engineering Reviews, 28, 147–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gossen M, Bender G, Muller G, al, et, & Freundlieb S (1995). Transcriptional activation by tetracyclines in mammalian cells. Science, 268(5218), 1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Y, Liu X-M, Liu H, Li S-C, Wu B-C, Ye L-L, … Chen Z-L (2006a). Cultivation of Recombinant Chinese hamster ovary cells grown as suspended aggregates in stirred vessels. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering, 102(5), 430–435. 10.1263/jbb.102.430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Y, Liu X-M, Liu H, Li S-C, Wu B-C, Ye L-L, … Chen Z-L (2006b). Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering, 102(5), 430–435. 10.1263/jbb.102.430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu W, Berdugo C, & Chalmers JJ (2011). The potential of hydrodynamic damage to animal cells of industrial relevance: current understanding. Cytotechnology, 63(5), 445–460. 10.1007/s10616-011-9368-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jay GD, & Waller KA (2014). The biology of Lubricin: Near frictionless joint motion. Matrix Biology, 39, 17–24. 10.1016/j.matbio.2014.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan M, & Wurm F (2004). Transfection of adherent and suspended cells by calcium phosphate. Methods, 33(2), 136–143. 10.1016/j.ymeth.2003.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SA, Tai C-Y, Mok L-P, Mosser EA, & Schuman EM (2011). Calcium-dependent dynamics of cadherin interactions at cell–cell junctions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(24), 9857–9862. 10.1073/pnas.1019003108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinken BJV, Dekker J, Buller HA, & Einerhand AW (1995). Mucin gene structure and expression: protection vs. adhesion. American Journal of Physiology - Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology, 269(5), G613–G627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo JC-H, Gandhi JG, Zia RN, & Paszek MJ (2018). Physical biology of the cancer cell glycocalyx. Nature Physics, 14(7), 658–669. 10.1038/s41567-018-0186-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leader B, Baca QJ, & Golan DE (2008). Protein therapeutics: a summary and pharmacological classification. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 7(1), 21–39. 10.1038/nrd2399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitin F, Stern O, Weiss M, Gil-Henn C, Ziv R, Prokocimer Z, … Wreschner DH (2005). The MUC1 SEA module is a self-cleaving domain. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 280(39), 33374–33386. 10.1074/jbc.M506047200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Qin J, Feng Q, Tang H, Liu R, Xu L, & Chen Z (2011). Heparin Promotes Suspension Adaptation Process of CHO–TS28 Cells by Eliminating Cell Aggregation. Molecular Biotechnology, 47(1), 9–17. 10.1007/s12033-010-9306-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Burnight ER, Cooney AL, Malani N, Brady T, Sander JD, … Craig NL (2013). piggyBac transposase tools for genome engineering. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(25), E2279–E2287. 10.1073/pnas.1305987110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M, & Goudar CT (2013). Gene expression profiling for mechanistic understanding of cellular aggregation in mammalian cell perfusion cultures. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 110(2), 483–490. 10.1002/bit.24730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner P, Pick H, Kulangara A, Chatellard P, Friedrich K, & Wurm FM (2001). Transient gene expression: recombinant protein production with suspension-adapted HEK293-EBNA cells. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 75(2), 197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercanti V, Marchetti A, Lelong E, Perez F, Orci L, & Cosson P (2010). Transmembrane domains control exclusion of membrane proteins from clathrin-coated pits. J Cell Sci, 123(19), 3329–3335. 10.1242/jcs.073031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oren M, Barela Hudgell MA, D’Allura B, Agronin J, Gross A, Podini D, & Smith LC (2016). Short tandem repeats, segmental duplications, gene deletion, and genomic instability in a rapidly diversified immune gene family. BMC Genomics, 17 10.1186/s12864-016-3241-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JH, Lim MS, Woo JR, Kim JW, & Lee GM (2016). The molecular weight and concentration of dextran sulfate affect cell growth and antibody production in CHO cell cultures. Biotechnology Progress, 32(5), 1113–1122. 10.1002/btpr.2287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paszek MJ, DuFort CC, Rossier O, Bainer R, Mouw JK, Godula K, … Weaver VM (2014). The cancer glycocalyx mechanically primes integrin-mediated growth and survival. Nature, 511(7509), 319–325. 10.1038/nature13535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peshwa MV, Kyung Y-S, McClure DB, & Hu W-S (1993). Cultivation of mammalian cells as aggregates in bioreactors: Effect of calcium concentration of spatial distribution of viability. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 41(2), 179–187. 10.1002/bit.260410203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues ME, Costa AR, Henriques M, Cunnah P, Melton DW, Azeredo J, & Oliveira R (2013). Advances and Drawbacks of the Adaptation to Serum-Free Culture of CHO-K1 Cells for Monoclonal Antibody Production. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology, 169(4), 1279–1291. 10.1007/s12010-012-0068-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg H, Kannicht C, Stenlund P, Dadaian M, Oswaldsson U, Cordula C, & Walter O (2012). Functional characteristics of the novel, human-derived recombinant FVIII protein product, human-cl rhFVIII. Thrombosis Research, 130(5), 808–817. 10.1016/j.thromres.2012.08.311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, … Cardona A (2012). Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nature Methods, 9(7), 676–682. 10.1038/nmeth.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla AA, & Thömmes J (2010). Recent advances in large-scale production of monoclonal antibodies and related proteins. Trends in Biotechnology, 28(5), 253–261. 10.1016/j.tibtech.2010.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shurer CR, Colville MJ, Gupta VK, Head SE, Kai F, Lakins JN, & Paszek MJ (2017). Genetically Encoded Toolbox for Glycocalyx Engineering: Tunable Control of Cell Adhesion, Survival, and Cancer Cell Behaviors. ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering. 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.7b00037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjaastad MD, & Nelson WJ (1997). Integrin-mediated calcium signaling and regulation of cell adhesion by intracellular calcium. BioEssays: News and Reviews in Molecular, Cellular and Developmental Biology, 19(1), 47–55. 10.1002/bies.950190109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swiech K, Kamen A, Ansorge S, Durocher Y, Picanço-Castro V, Russo-Carbolante EM, … Covas DT (2011). Transient transfection of serum-free suspension HEK 293 cell culture for efficient production of human rFVIII. BMC Biotechnology, 11, 114 10.1186/1472-6750-11-114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang NC, & Chilkoti A (2016). Combinatorial codon scrambling enables scalable gene synthesis and amplification of repetitive proteins. Nature Materials, 15(4), 419–424. 10.1038/nmat4521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton DJ, Rousseau K, & McGuckin MA (2008). Structure and Function of the Polymeric Mucins in Airways Mucus. Annual Review of Physiology, 70(1), 459–486. 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolbert WR, Hitt MM, & Feder J (1980). Cell aggregate suspension culture for large-scale production of biomolecules. In Vitro, 16(6), 486–490. 10.1007/BF02626461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsao YS, Condon R, Schaefer E, Lio P, & Liu Z (2001). Development and improvement of a serum-free suspension process for the production of recombinant adenoviral vectors using HEK293 cells. Cytotechnology, 37(3), 189–198. 10.1023/A:1020555310558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vink T, Oudshoorn-Dickmann M, Roza M, Reitsma J-J, & de Jong RN (2014). A simple, robust and highly efficient transient expression system for producing antibodies. Methods, 65(1), 5–10. 10.1016/j.ymeth.2013.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesseling J, Valk SW van der, & Hilkens J (1996). A mechanism for inhibition of E-cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion by the membrane-associated mucin episialin/MUC1. Molecular Biology of the Cell, 7(4), 565–577. 10.1091/mbc.7.4.565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesseling J, van der Valk SW, Vos HL, Sonnenberg A, & Hilkens J (1995). Episialin (MUC1) overexpression inhibits integrin-mediated cell adhesion to extracellular matrix components. The Journal of Cell Biology, 129(1), 255–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson MH, Coates CJ, & George AL (2007). PiggyBac transposon-mediated gene transfer in human cells. Molecular Therapy: The Journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy, 15(1), 139–145. 10.1038/sj.mt.6300028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodard LE, & Wilson MH (2015). piggyBac-ing models and new therapeutic strategies. Trends in Biotechnology, 33(9), 525–533. 10.1016/j.tibtech.2015.06.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurm F, & Bernard A (1999). Large-scale transient expression in mammalian cells for recombinant protein production. Current Opinion in Biotechnology, 10(2), 156–159. 10.1016/S0958-1669(99)80027-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurm FM (2004). Production of recombinant protein therapeutics in cultivated mammalian cells. Nature Biotechnology, 22(11), 1393–1398. 10.1038/nbt1026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto S, Matsuda H, Takahashi T, Xing X-H, Tanji Y, & Unno H (2000). Aggregate formation of rCHO cells and its maintenance in repeated batch culture in the absence of cell adhesion materials. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering, 89(6), 534–538. 10.1016/S1389-1723(00)80052-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanghi JA, Renner WA, Bailey JE, & Fussenegger M (2000). The Growth Factor Inhibitor Suramin Reduces Apoptosis and Cell Aggregation in Protein-Free CHO Cell Batch Cultures. Biotechnology Progress, 16(3), 319–325. 10.1021/bp0000353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J (2012). Mammalian cell protein expression for biopharmaceutical production. Biotechnology Advances, 30(5), 1158–1170. 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2011.08.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Movie showing Mucin-270 cells (left), w.t. cells (center), and w.t. cells with commercial anti-clumping agent (right) in media containing 2 mM CaCl2. The Mucin-270 culture is more turbid than w.t. cultures with only small aggregates. Large clusters are easily observed in both the w.t. culture and w.t. with commercial anti-clumping agent culture.

Additional data to accompany Figure 3 acquired 24 hr prior. A, Quantification of the fraction of cells in various cluster sizes from phase contrast images such as those shown in Fig. 3A. Cells are grown at 3.2 ± 0.7 × 106 cells/mL for 48 hr for all panels. Center lines show the medians; box limits indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles as determined by R software; whiskers extend 1.5 times the interquartile range from the 25th and 75th percentiles, outliers are represented by dots; crosses represent sample means. B, Quantification of the fraction of cells which are in clusters of various sizes from phase contrast images such as those shown in Fig. 3A. Mean and S.D. are shown. C, Ripley’s K function versus distance calculated for the cell distribution acquired from phase contrast images such as those shown in Fig. 3A. Mean and S.E.M. are shown, replicates described in Fig. 3B, n =3,. ns – not significant; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.005.