Abstract

An easy and inexpensive method of determining the photosynthetic pathway in grasses using a dye widely used in microscopy. To evaluate the efficiency of a new histochemical test for determination of the photosynthetic pathway in grasses (Poacea). Leaves of 58 grass species were sectioned transversally, and the sections treated with a 2% sodium hypochlorite solution to clarify the tissue. After discoloration, sections were washed with distilled water and double-stained with astra blue and safranin (1% each in 50% ethanol) for 1 min. Sections were then mounted between microscopy glass slides and coverslips using water. Grass species showing red staining of the bundle sheath cells were considered C4, and species with translucent bundle sheath were considered C3. The results of the histochemical test were then compared with results from carbon isotope composition analysis and the relevant scientific literature. Observations from the histochemical test were congruent with results from δ13C isotope composition analysis, and with data previously presented in the scientific literature. The proposed histochemical test proved efficient for characterization of the photosynthetic pathway in the tested grasses; however, the method should be further tested in a greater number of grass species, encompassing, preferably, all Poacea subfamilies. Future studies may elucidate if the proposed method can effectively be used in other botanical families. Furthermore, additional investigations may determine whether the phenolic compounds indicated by the histochemical test are exclusive to the bundle sheath of C4 grasses and if possible relations exist between these phenolic compounds and the C4 photosynthetic pathway in grasses.

Keywords: Poaceae, Histochemistry, Safranin, C4, Phenolic, Grasses

Introduction

The C4 photosynthetic rout evolved in plants tens of millions of years ago in response to environmental changes, characterizing an advantage under high light, hight temperature, or draught conditions (Ehleringer et al. 1991; Bowes 1993; Sage 2004).

There are 19 botanical families with C4 species (Sage et al. 2012). Among them, Poaceae is the most diverse with 4500 C4 species (Christin et al. 2008; Vicentini et al. 2008; Bouchenak-Khelladi et al. 2009; Christin and Besnard 2009), which comprises ca. half of all C4 species (Sage et al. 1999). Within grasses, all C4 lineages occur in branches denominated PACMAD, including the subfamilies Panicoideae, Arundinoideae, Chloridoideae, Micrairoideae, Aristidoideae and Dantoideae (Kellogg 1999, 2001; Sage et al. 2011).

The distinction between C3 and C4 grasses is not often apparent, although some characteristics can aid in the process, with emphasis on: anatomic characters; carbon isotope composition and CO2 compensation point; and the activity of specific enzymes. Many authors have attempted to use anatomical characteristics (Hattersley and Watson 1975, 1976; Hattersley and Browning 1981; Hattersley 1984; Prendergast and Hattersley 1987; Prendergast et al. 1987; Dengler et al. 1994), however, evaluation by anatomical traits alone led to much confusion. Carbon isotope composition (δ13C) is also used as a distinction criterion between C3 and C4 plants. Values between − 10 and − 14‰ indicate a C4 plant, while values between − 20 and − 35‰ indicate a C3 plant (Cerling 1999); however, this method requires expensive, high-maintenance equipment. Other methods were employed for the determination of photosynthetic pathways in plants (Edwards and Walker 1983; Hatch 1987; Sage et al. 1987), but always with caveats related to time and cost issues.

Neto (2017) proposed a histochemical method for determination of the photosynthetic pathway in grasses using Safranin O. The test is positive for C4 grasses when cells of the bundle sheath stain strongly red. In C3 grasses, cells of the bundle sheath do not stain red. Confirmation of the efficiency of the histochemical test would provide an additional—as well as convenient and cheap method for determination of the photosynthetic pathway in grasses. However, validation of the test requires evaluation of its efficiency in a larger number of grass species, as well as confirmation of whether similar results can be obtained among the three types of C4 grasses [NAD-dependent malic enzyme (NAD-ME), PEP-Carboxikinase (PCK), and NADP-dependent malic enzyme (NADP-ME)], comparing the results from the histochemical test with carbon isotope composition analysis and information within the relevant literature.

Materials and methods

Plant material collection and preparation

Control leaf samples were collected from grasses with known photosynthetic pathways (rice—C3; maize and sugarcane—C4 NADP-ME). Leaves of 15 identified forage species and 14 identified bamboo species, of several genera, were collected from plants cultivated at Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina’s Fazenda Experimental da Ressacada, Florianópolis, Santa Catarina, Brazil. Additional leaf samples were obtained from 12 grass species cultivated at Embrapa’s Amazonia Oriental experimental area in Belém, Pará, Brazil, and 13 wild grass species in Santa Catarina state. Dried specimens from grasses collected in Belém were deposited at the Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi’s herbarium (Herbarium MG), where specimens were identified by means of botanical comparison, and dried specimens of grasses collected in Santa Catarina were deposited at Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina’s herbarium (Herbário Flor), where specimens were also identified by means of comparison.

Leaves collected for determination of carbon isotope composition were placed in paper bags for subsequent dehydration, and leaves used in the histochemical test were fixated in 70% ethanol.

Determination of stable carbon isotope composition (δ13C) in grasses

Leaf samples were dehydrated in a drying stove (50 °C, until constant mass). Afterwards, leaves were ground in liquid nitrogen with a mortar and pestle until a fine powder was obtained. Ground leaf samples were analyzed at the Laboratóro de Ecologia Isotópica—CENA/USP (Piracicaba, SP). About 2.5 mg of leaf material were conditioned inside aluminium capsules and inserted in an element analyser (EA CHN Carlo Erba—modelo E-1110, Milan, Italy), for determination of the total carbon concentration. The gases generated by the samples’ combustion were purified and injected directly into a mass spectrometer (IRMS Delta Plus, Thermo Scientific, Bremen, Germany), for determination of isotope ratios. The natural abundance of 13C is expressed as the notation delta (δ) and as a value given in parts per thousand (‰), being determined by means of the equation:

where Rsample and Rstandard are the molar ratios 13C/12C of the sample and the standard, respectively. The employed standard was the fossil limestone PeedeeBelamnite (PDB). At each analysis round reference leaf material of known carbon concentration and δ13C was used (sugarcane leaves, δ13C = − 12.7 ‰; %C = 43.82%). The acceptable analytical error for carbon concentration determination is 0.3% and for δ13C is 0.3‰.

Histochemical test for determination of the photosynthetic pathway in grasses

Leaves fixed in 70% ethanol were sectioned transversally at their middle portion by hand with stainless steel blades. Leaf sections were treated with 2% sodium hypochlorite solution for tissue clarification. After discoloration, sections were washed with distilled water and double-stained with astra blue and safranin (1% each in 50% ethanol) for 1 min. Sections were then mounted between microscopy glass slides and coverslips, with a drop of water between them. Photomicrographs were obtained using an Olympus BX40 optical microscope attached to an Olympus DP71 camera.

Results

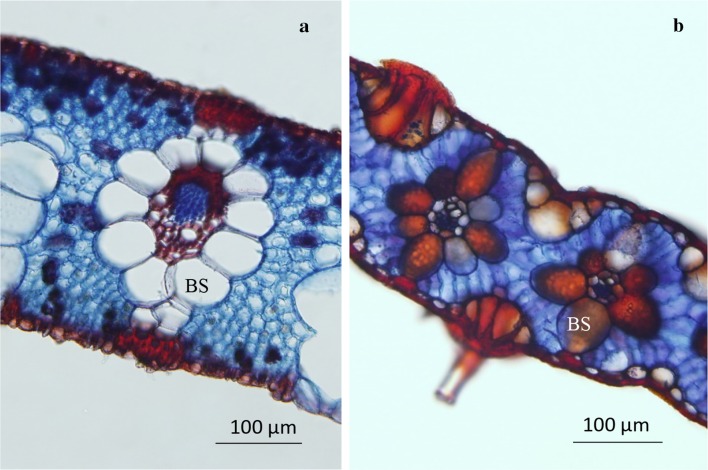

Results from the histochemical test differed between C3 and C4 grasses. C4 grasses presented bundle-sheath cells stained red, while C3 did not. Results for Arundo donax and Uruchloa brizantha clearly illustrate the distinction (Fig. 1). These results are compatible with those provided in Neto (2017).

Fig. 1.

Histochemical test results in Arundo donax (a) and Urochloa brizantha (b). The translucent bundle-sheath cells (BS) in A. donax and the intensely stained red cells in U. brizantha indicate that A. donax is C3 and U. brizantha is C4

Table 1 shows the results of the carbon isotope composition analysis and of the histochemical test of 58 grass species, representing 40 genera, 12 tribes and 6 subfamilies. The results from isotope composition (δ13C) analysis of all evaluated grasses correlated with the histochemical test. All grasses with isotope composition values between − 26.09 and − 29.26 indicated a C3 plant, and presented a negative result in the histochemical test. In contrast, all plants with isotope composition values between − 9.88 and − 14.21 indicated a C4 plant, and presented a positive result in the histochemical test.

Table 1.

Results of the histochemical test (H.T.) and isotopic composition (δ13C, average of three replicates and SD) of 58 grass species

| Categories/species | Subfamily | Tribe | P.P. | H.T. | δ13C‰ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forage | |||||

| Axonopus cothinansis | Panicoideae | Paniceae | NADP-ME (G) | + | − 12.39 ± 0.29 |

| Brachiaria brizantha | Panicoideae | Paniceae | PCK | + | − 11.77 ± 0.17 |

| Brachiaria decumbens | Panicoideae | Paniceae | PCK | + | − 12.27 ± 0.27 |

| Cynodon nlemfluensis | Chloridoideae | Cynodonteae | NAD-ME (G) | + | − 13.46 ± 0.16 |

| Festuca arundinacea | Pooideae | Poeae | C3 | − | − 26.09 ± 0.30 |

| Festuca aurora | Pooideae | Poeae | C3 | − | − 28.14 ± 0.12 |

| Hemarthria altíssima | Panicoideae | Andropogoneae | NADP-ME (G) | + | − 11.68 ± 0.24 |

| Holcus lanatus | Pooideae | Poeae | C3 | − | − 29.26 ± 0.06 |

| Panicum maximum | Panicoideae | Paniceae | PCK (E) | + | − 12.45 ± 0.15 |

| Paspalum atratum | Panicoideae | Paniceae | NADP-ME (G) | + | − 12.06 ± 0.12 |

| Paspalum notatum | Panicoideae | Paniceae | NADP-ME (S) | + | − 11.99 ± 0.13 |

| Pennisetum americanum | Panicoideae | Paniceae | NADP-ME (G) | + | − 12.54 ± 0.12 |

| Pennisetum purpureum | Panicoideae | Paniceae | NADP-ME (S) | + | − 9.88 ± 0.14 |

| Pennisetum setaceum | Panicoideae | Paniceae | NADP-ME (G) | + | n |

| Setaria anceps | Panicoideae | Paniceae | NADP-ME (S) | + | − 11.04 ± 0.12 |

| Sorghum sudanense | Panicoideae | Andropogoneae | NADP-ME (G) | + | − 12.80 ± 0.09 |

| Bamboo | |||||

| Bambusa oldhamii | Bambusoideae | Bambuseae | C3 | − | − 28.66 ± 0.23 |

| Chimono bambusa quadrangulares | Bambusoideae | Bambuseae | C3 | − | − 31.01 ± 0.10 |

| Chusquea leptophyla | Bambusoideae | Bambuseae | C3 | − | − 27.92 ± 0.18 |

| Dendrocalamus asper | Bambusoideae | Bambuseae | C3 | − | − 26.42 ± 0.12 |

| Drepanostachyum falcatum | Bambusoideae | Arundinarieae | C3 | − | − 29.12 ± 0.12 |

| Fargesia gaolinensis | Bambusoideae | Arundinarieae | C3 | − | − 27.71 ± 0.07 |

| Guadua chacoensis | Bambusoideae | Bambuseae | C3 | − | − 30.83 ± 0.19 |

| Parodiolyra micrantha | Bambusoideae | Olyraceae | C3 | − | − 28.70 ± 0.20 |

| Phyllostachys nigra nigra | Bambusoideae | Bambuseae | C3 | − | − 29.36 ± 0.16 |

| Pleioblastus simonii | Bambusoideae | Bambuseae | C3 | − | − 28.05 ± 0.15 |

| Pseudosasa japônica | Bambusoideae | Bambuseae | C3 | − | − 29.15 ± 0.15 |

| Raddia soderstromii | Bambusoideae | Olyreae | C3 | − | − 29.16 ± 0.08 |

| Sasa palmate | Bambusoideae | Bambuseae | C3 | − | − 29.91 ± 0.18 |

| Thyrsostachys siamensis | Bambusoideae | Bambuseae | C3 | − | − 28.99 ± 0.09 |

| Collected | |||||

| Arundo donax | Arundinoideae | Arundineae | C3 | − | − 30.30 ± 0.09 |

| Cenchrus echinatus | Panicoideae | Paniceae | NADP-ME (G) | + | − 12.12 ± 0.14 |

| Cymbopogon citratus | Panicoideae | Andropogoneae | NADP-ME (G) | + | − 12.4 ± 0.20 |

| Digitaria ciliares | Panicoideae | Paniceae | NADP-ME (G) | + | − 11.99 ± 0.18 |

| Digitaria horizontalis | Panicoideae | Paniceae | NADP-ME (G) | + | − 12 ± 0.20 |

| Echinochloa colona | Panicoideae | Paniceae | NADP-ME (G) | + | − 13.02 ± 0.14 |

| Echinochloa crus-pavonis | Panicoideae | Paniceae | NADP-ME (G) | + | − 12.64 ± 0.16 |

| Echinochloa polystachya | Panicoideae | Paniceae | NADP-ME (G) | + | − 11.88 ± 0.26 |

| Eleusine indica | Chloridoideae | Cynodonteae | NAD-ME (G) | + | − 13.3 ± 0.09 |

| Eragrostis tenufolia | Chloridoideae | Eragrostideae | NAD-ME (G) | + | − 14.21 ± 0.07 |

| Homolepis aturensis | Panicoideae | Paniceae | C3 | − | − 28.8 ± 0.12 |

| Homolepis isocalycia | Panicoideae | Paniceae | C3 | − | − 26.3 ± 0.13 |

| Hymenachne amplexicaulis | Panicoideae | Paniceae | C4 | + | − 12 ± 0.14 |

| Megathyrsus maximus | Panicoideae | Paniceae | C4 (G) | + | − 13.47 ± 0.24 |

| Paspalum conjugatum | Panicoideae | Paniceae | NADP-ME (G) | + | − 12.3 ± 0.13 |

| Paspalum maritimum | Panicoideae | Paniceae | NADP-ME (G) | + | − 11.6 ± 0.18 |

| Paspalum melanospermum | Panicoideae | Paniceae | NADP-ME (G) | + | − 11.8 ± 0.09 |

| Paspalum pauciciliatum | Panicoideae | Paniceae | NADP-ME (G) | + | − 13.54 ± 0.12 |

| Paspalum urvillei | Panicoideae | Paniceae | NADP-ME (G) | + | − 12.37 ± 0.09 |

| Paspalum virgatum | Panicoideae | Paniceae | NADP-ME (G) | + | − 11.9 ± 0.13 |

| Setaria parviflora | Panicoideae | Paniceae | NADP-ME (G) | + | − 12.19 ± 0.18 |

| Sorghum halepense | Panicoideae | Andropogoneae | NADP-ME (G) | + | − 13.11 ± 0.13 |

| Sporobolus indicus | Chloridoideae | Zoysieae | NAD-ME (G) | + | − 13.3 ± 0.21 |

| Steinchisma laxum | Panicoideae | Paniceae | C3 | − | − 27 ± 0.21 |

| Urochloa brizantha | Panicoideae | Paniceae | PCK (G) | + | − 13.02 ± 0.18 |

| Crops | |||||

| Oryza sativa | Oryzoideae | Oryzeae | C3 | − | n |

| Saccharum officinarum | Panicoideae | Andropogoneae | NADP-ME (G) | + | n |

| Zea mays | Panicoideae | Andropogoneae | NADP-ME (S) | + | n |

It includes subfamily, tribe, and the photosynthetic pathway (P.P., C3 or C4) and the C4 type of some species (S) and genera (G), according to the literature data (Sage et al. 1999)

n not determined

The histochemical test showed a negative result for all evaluated bamboos, and confirmated the photosynthetic pathway of maize and sugarcane (C4 type NADP-ME, with positive results) and rice (C3, with a negative result), and positive to the three photosynthetic pathway grasses (PDK, NAD-ME and NADP-ME) (Table 1).

Among the forage grasses, only Festuca aurora, Festuca arundinacea, and Holcus lanatus showed negative results. Among the tested wild grasses, Homolepsis aturensis, H. isocalycia, Steinchis malaxum, and A. donax showed negative results, indicating a C3 photosynthetic pathway. All other tested species of forage and wild grasses presented a positive result, indicating they have C4 photosynthetic systems.

Leaf transversal sections that underwent dehydration during performance of the histochemical test presented a slight detachment of the cell wall membrane, and this allowed inferring that the safranin-reactive phenolic substance is located in C4 grasses’ bundle sheath cells’ protoplasts, and not in the cell wall (data not shown).

Discussion

Safranin O is the least specific histochemical indicator of lignin because it not only stains lignin, but all related phenolic substances (Lewis and Yamamoto 1990). The red staining exclusively observed in cells from the bundle sheath of C4 grasses indicates the existence of a phenolic substance only in these cells.

Many plant species present hydroxycinnamic acids (ρ-coumaric, sinapic and ferulic acids) attached to cell walls (Chen et al. 1998; Brett et al. 1999; Bunzel et al. 2003). Derived from the phenilpropanoid metabolism (Ou and Kwok 2004), ferulic acid (4-hydroxy-3-methoxycinnamic) is abundant in plant epidermis, xylem, sheath bundle, and sclerenchyma cells (Faulds and Williamson 1999; Lambert et al. 1999), while also being present on primary and secondary cell walls in grasses (Harris and Hartley 1976).

The red stain observed in bundle sheath cells may indicate the presence of hydroxicinamic acid. However, the observation that the phenolic substances revealed by the histochemical test are located in the protoplasts of bundle sheath cells, and not in the cell wall, suggests such substances are likely to perform another important function inside the cells. The presence of these substances exclusively in cells of C4 grasses’ bundle sheaths may indicate an antioxidant function in view of the capacity antioxidant of these substance. According to Faulds and Williamson (1999) hydroxycinnamic acids, such as ferulic, sinapic, cafeic and p-coumaric acid, are found both covalently attached to the plant cell wall and as soluble forms in the cytoplasm.

The results of the histochemical test of bamboos were expected, given that bamboos are included in the Bambusoideae subfamily, which is composed exclusively of C3 species, distributed between the Bambuseae, Olyreae e Arundinarieae tribes.

The genera Festuca and Holcus are included in the Pooideae subfamily, which is composed exclusively by C3 species (Sage and Monson 1999). Homolepis aturensis, Homolepis isocalycia e Steinchis malaxum are part of the Panicoideae subfamily, Paniceae tribe. The Paniceae tribe presents C3, C4 (of all biochemical subtypes) and intermediary C3–C4 plants. Arundo donax is included in the Arundinoideae subfamily (composed of 60 genera, of which five are C4) and within the Arundineae tribe, composed exclusively of C3 species (Sage et al. 1999).

The genera Axonopus, Cenchrus, Cymbopogon, Digitaria, Hemarthria, Paspalum, Pennisetum, Setaria and Sorghum are C4 of the NADP-ME type. The photosynthetic pathway NADP-ME occurs in the forage species Setaria anceps, Pennisetum purpureum, and Paspalum notatum. The genera Brachiaria and Urochloa are C4 of type PCK, and genera Cynodon, Eragrostis and Sporobolus are C4 of type NAD-ME. The genus Panicum is the only genus to present C3, C4 of all types, and intermediary C3-C4 species, with Panicum maximum being PCK (Sage et al. 1999).

The results from the histochemical test and the carbon isotope composition analysis are in accordance with previous reports concerning the plant genera represented in this study, indicating that the proposed histochemical test can be employed as an additional criterion for the determination of the photosynthetic pathway in grasses. The convenience and low cost of the proposed method allows its utilization as a first indicator of the photosynthetic pathway in grasses. However, its use is recommended only with fresh samples, given that its performance with dry samples is not feasible.

Future studies may confirm the applicability of this method in other botanical families with C4 member species. In Cyperaceae, preliminary studies did not validate use of the test (data not shown). Additionally, the isolation and identification of the phenolic compounds detected by the histochemical test in bundle sheath cells of C4 grasses may elucidate a possible relation between the presence of these substances and the C4 photosynthetic pathway.

Acknowledgements

Our most sincere thanks to the Laboratório de Ecologia Isotópica do Centro de Energia Nuclear na Agricultura—CENA/USP, represented by Prof. Dr. Luiz Antônio Martinelli, for the isotope analyses. We also thank the herbariums Herbários Flor, of Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina and Herbário MG, of Museu paraense Emílio Goeldi, for the plant species identification.

Author contributions

MAMN and MPG performed the experiments. MAMN analyzed and interpreted the results. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Bouchenak-Khelladi Y, Verboom GA, Hodkinson TR, et al. The origins and diversification of C4 grasses and savanna-adapted ungulates. Glob Change Biol. 2009;15:2397–2417. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2009.01860.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowes G. Facing the inevitable: plant sand increasing atmosferic CO2. Ann Rev Plant Physiol Mol Biol. 1993;44:309–332. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pp.44.060193.001521. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brett CT, Wende G, Smith AC, Waldron KW. Biosynthesis of cell-wall ferulate and diferulates. Eur Food Res Technol. 1999;214:482–488. [Google Scholar]

- Bunzel M, Ralph J, Kim H, Lu F, Ralph SA, et al. Sinapate dehydrodimers and sinapate–ferulate heterodimers in cereal dietary fiber. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:1427–1434. doi: 10.1021/jf020910v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerling T. Paleo records of C4 plants and ecosystems. In: Sage RF, Monson RK, editors. C4 plant biology. San Diego: Academic Press; 1999. pp. 445–469. [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Gitz DC, McClure JW. Soluble sinapoyl esters are converted to wall-bound esters in phenylalanine ammonia-lyase-inhibited radish seedlings. Phytochemistry. 1998;49:333–340. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(98)00109-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christin PA, Besnard G. Two independent C4 origins in Aristidoideae (Poaceae) revealed by the recruitment of distinct phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase genes. Am J Bot. 2009;96:2234–2239. doi: 10.3732/ajb.0900111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christin PA, Besnard G, Samaritani E, Duvall MR, Hodkinson TR, et al. Oligocene CO2 decline promoted C4 photosynthesis in grasses. Curr Biol. 2008;18:37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.11.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dengler NG, Dengler RE, Donnelly PM, Hattersley PW. Quantitative leaf anatomy of C3 and C4 grasses (Poaceae): bundle sheath and mesophyll surface area relationships. Ann Bot. 1994;73:241–255. doi: 10.1006/anbo.1994.1029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards GE, Walker DA. C3, C4: mechanisms, and celular and environmental regulation of photosynthesis. Oxford: Blackwell; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Ehleringer JR, Sage RF, Flanagran LB, Pearcy RW. Climate change and the evolution of C4 photosynthesis. Trends Ecol Evolut. 1991;6:95–99. doi: 10.1016/0169-5347(91)90183-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulds CB, Williamson G. The role of hydroxycinnamates in the plant cell wall. J Sci Food Agric. 1999;79:393–395. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0010(19990301)79:3<393::AID-JSFA261>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PJ, Hartley RD. Detection of bound ferulic acid in cell walls of the Gramineae by ultraviolet fluorescence microscopy. Nature. 1976;259:508–510. doi: 10.1038/259508a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hatch MD. C4 photosynthesis: a unique blend of modified biochemistry, anatomy and ultrastructure. Biochem Biophys Acta. 1987;895:81–106. [Google Scholar]

- Hattersley PW. Characterization of C4 type leaf anatomy in grasses (Poaceae). Mesophyll: bundle sheath area ratios. Ann Bot. 1984;53:163–179. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aob.a086678. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hattersley PW, Browning AJ. Occurrence of the suberized lamella in leaves of grasses of different photosynthetic types. I. In parenchymatous bundle sheath and PCR (kranz) sheaths. Protoplasma. 1981;109:333–371. doi: 10.1007/BF01287454. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hattersley PW, Watson L. Anatomical parameters for predicting photosynthetic pathways of grass leaves: the “maximum lateral cell count” and the “maximum cells distant count”. Photomorphology. 1975;25:325–333. [Google Scholar]

- Hattersley PW, Watson L. C4 grasses: anatomical criterion for distinguishing between NADP-malic enzyme species and PCK or NAD-ME enzyme species. Aust J Bot. 1976;24:297–308. doi: 10.1071/BT9760297. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kellogg EA. Phylogenetic aspects of the evolution of C4 photosynthesis. In: Sage RF, Monson RK, editors. C4 plant biology. San Diego: Academic Press; 1999. pp. 411–444. [Google Scholar]

- Kellogg EA. Evolutionary history of the grasses. Plant Physiol. 2001;125:1198–1205. doi: 10.1104/pp.125.3.1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert N, Kroon PA, Faulds CB, Plumb GW, McLauchlan WR, et al. Purification of cytosolic beta-glucosidase from pig liver and its reactivity towards flavonoid glycosides. Biochem Biophys Acta. 1999;1435:110–116. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(99)00213-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis NG, Yamamoto E. Lignin: ocorrence, biogenesis and biodegradation. Ann Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1990;41:455–496. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pp.41.060190.002323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neto MAM. Determinação da via fotossintética em gramíneas. In: da Filho APSS, editor. Poaceae Barnhart. Belém: Marques Editora; 2017. pp. 103–122. [Google Scholar]

- Ou S, Kwok K. Ferulic acid: pharmaceutical Functions preparation and applications in foods. J Sci Food Agric. 2004;84(11):1261–1269. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.1873. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prendergast HDV, Hattersley PW. Australian C4 grasses (Poaceae): leaf blade anatomical features in relation to C4 acid decarboxylation types. Aust J Bot. 1987;35:355–420. doi: 10.1071/BT9870355. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prendergast HDV, Hattersley PW, Stone NE. New structural/biochemical associations in leaf blades of C4 grasses (Poaceae) Funct Plant Biol. 1987;14(4):403–420. doi: 10.1071/PP9870403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sage RF. The evolution of C4 photosynthesis. New Phytol. 2004;161:341–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.00974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage RF, Monson RK. C4 plant biology. San Diego: Academic Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sage RF, Pearcy RW, Seemann JR. The nitrogen use efficiency of C3 and C4 plants. Plant Physiol. 1987;85:355–359. doi: 10.1104/pp.85.2.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage RF, Li M, Monson RK. The taxonomic distribution of C4 photosynthesis. In: Sage RF, Monson RK, editors. C4 plant biology. San Diego: Academic Press; 1999. pp. 551–584. [Google Scholar]

- Sage RF, Christin PA, Edwards EJ. The C4 plant lineages of planet Earth. J Exp Bot. 2011;62:3155–3169. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage RF, Sage TL, Kocacinar F. Photorespiration and the evolution of C4 photosynthesis. Ann Rev Plant Biol. 2012;63:19–47. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042811-105511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicentini A, Barber JC, Aliscioni SS, Giussani LM, Kellogg EA. The age of the grasses and clusters of origins of C4 photosynthesis. Glob Change Biol. 2008;14:2963–2977. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2008.01688.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]