Abstract

Objective:

The objective of this study was to evaluate use of the Internet to solicit sex partners by men who have sex with men (MSM) who were diagnosed with early syphilis infection.

Study:

Field interview records for syphilis patients were reviewed for factors associated with Internet use.

Results:

Internet users were more likely to be of white race (prevalence ratio [PR], 1.6; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.4–1.8), to report anal insertive sex (PR, 1.1; 95% CI, 1.1–1.2), sex with anonymous partners (PR, 1.2; 95% CI, 1.1–1.3), intravenous drug use (PR, 2.7; 95% CI, 1.1–6.7), and nonintravenous drug use (PR, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.1–1.8). Controlling for race and sexual risk behaviors, white race (odds ratio [OR], 2.8; 95% CI, 1.8–4.6), having anonymous sex partners (OR, 3.4; 95% CI, 1.6–7.0), and nonintravenous drug use (OR, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.1–2.6) were associated with meeting sex partners through the Internet.

Conclusions:

Effective sexually transmitted disease risk reduction interventions using the Internet are needed to reach Internet-using, sex-seeking MSM populations engaging in high-risk behaviors.

RISING SYPHILIS RATES IN many urban cities in the United States, Canada, and Western Europe have been focused in men who have sex with men (MSM). Cities experiencing syphilis epidemics in the United States among MSM report HIV coinfection rates ranging from 48% to 75%.1–7 These trends in syphilis and HIV coinfections have prompted multiple public health responses and national media attention.4,7–10 Despite these efforts, disturbing trends in unsafe sexual behavior among MSM continue to be described.7,11–13 The increased risk of HIV transmission in association with a concomitant sexually transmitted disease (STD) such as syphilis14 further necessitates the need for targeted education and interventions at venues, like the Internet, where sex partners are solicited and where sex acts occur to prevent transmission of these infections.

Venues used by MSM for meeting sex partners in Los Angeles and other cities have historically included public sex venues such as bathhouses and sex clubs as well as other public and private venues.8,15,16 Use of these venues to meet sexual partners has been associated with drug use, unprotected anal intercourse, and STD diagnoses.17,18 The use of the Internet among MSM diagnosed with early syphilis in California is emerging as a dominant venue for meeting sexual partners.19 Published data describing the use of the Internet to meet sex partners by MSM have identified associated risk behaviors similar to those reported from commercial sex environments, including sex with multiple casual partners, exposure to persons with HIV, low rates of condom use, and unprotected anal intercourse with partners of unknown HIV status.20–23 Use of the Internet to meet sex partners has been associated with diagnosis of STDs such as syphilis.9 Los Angeles County has experienced rising rates of syphilis in MSM since 2000.2,8,15 Many of these men with syphilis report meeting sex partners through the Internet.15

Use of the Internet to meet sex partners is a growing concern among public health officials for the following reasons: 1) the association of some Internet users with sexual risk-taking behavior, 2) the difficulty of contact tracing and partner notification, and 3) the challenges of creating an effective intervention to curb unsafe sexual behavior solicited through the Internet.24 We evaluated the use of the Internet to meet sex partners among MSM diagnosed with early syphilis during 2001–2003 to describe trends in Internet use by MSM with syphilis and to describe demographic and behavioral correlates of Internet use in this population.

Methods

Syphilis is a reportable infectious disease in California. Medical providers as well as laboratories are required to report cases of syphilis within 24 hours of diagnosis or receipt of a positive lab result. Public health investigators (PHI) conduct field interviews of early syphilis cases (primary, secondary, and early latent) to collect additional demographic information, risk behavior information, and information on contacts and partners. PHI provide counseling and referral to infected patients and proceed with partner counseling and referral services to decrease onward transmission of syphilis. A retrospective review of these cases collected during January 2001 through December 2003 was performed to identify correlates of Internet use.

Data Collection

Field interview records obtained on MSM early syphilis cases were reviewed for the years 2001–2003 for demographic, behavioral, and clinical data. Demographic data included age, race/ethnicity, zip code of primary residence, HIV status, and history of incarceration. Sexual behavioral data included self-reported anal sex, oral sex, sex with anonymous partners, venues for meeting sex partners, condom use, and intravenous and nonintravenous drug use as practiced during the “critical period” of syphilis infection defined in the case definition. Sex with anonymous partners was defined as oral or anal sex with a person for whom no identifying information was available to the syphilis patient. Clinical data included stage of diagnosis, symptoms present at time of diagnosis, treatment information, and follow-up lab testing. Per U.S. Department of Health and Human Services guidelines, data collection, evaluation, and analysis are part of ongoing public health surveillance activities and thus are not subject to review by Institutional Review Boards.

Case Definition

Early syphilis consisted of all reported primary, secondary, and early latent syphilis cases. The diagnosis of primary syphilis was made by the presence of 1 or more ulcers at the site of exposure and the demonstration of exposure to Treponema pallidum by a reactive serologic test for syphilis. Secondary syphilis was diagnosed by the presence of characteristic dermatologic lesions and a reactive nontreponemal test (titer >1:4). The diagnosis of early latent syphilis was made in persons with evidence of having acquired the infection within the previous 12 months based on 1 or more of the following criteria: documented negative test in the last 12 months or a 4-fold or greater increase in titer of a nontreponemal test during the previous 12 months or a history of symptoms consistent with primary or secondary syphilis during the previous 12 months, or a history of sexual exposure to a partner who had confirmed infectious syphilis, or reactive nontreponemal and treponemal tests from a person whose only possible exposure occurred within the preceding 12 months.25

“Critical period” is defined as the time period when a patient is most likely to have contracted syphilis or more likely to have transmitted the infection to another person and varies by the stage of syphilis infection. For primary syphilis, it is the period from treatment date back to 90 days from the onset of symptoms. For secondary syphilis, it is the period from treatment date back to 6.5 months before the onset of symptoms. For early latent syphilis, it is the period from the date of treatment back to 1 year.26

Analysis

Data were analyzed using SAS statistical package version 8.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Initial descriptive analyses of all variables were used to create dichotomized potential predictor variables. Factors that influenced the outcome of interest were assessed in bivariate analysis using chi-squared statistics for categorical variables. Prevalence ratios were used to compare demographics and risk behaviors between Internet users and Internet nonusers. Using logistic regression analysis, the odds of having met a sex partner through the Internet during the critical period when syphilis infection likely occurred were calculated, and variables that were independent correlates of Internet use to meet sex partners were determined by including all independent variables in the model.

Results

Description of Study Population

A total of 1852 cases of early syphilis were reported to the Los Angeles County Department of Health during 2001–2003. Of these, 1219 cases (66%) occurred among MSM. The study population consisted of 850 MSM diagnosed with early syphilis during 2001–2003 in Los Angeles County that responded to questions regarding use of the Internet to meet sex partners during the field interview. Of these, 16% had primary syphilis, 44% had secondary syphilis, and 30% had early latent syphilis. Forty-eight percent of the sample population were white, 11% were black, and 35% were Hispanic. The age distribution was as follows: 1.4% were less than 20 years of age, 19% were between 20 and 29 years of age, 44% were between 30 to 39 years of age, and 27% were between 40 and 49. Sixty percent of the sample population self-reported being HIV-positive.

Trends in Use of the Internet to Meet Sex Partners

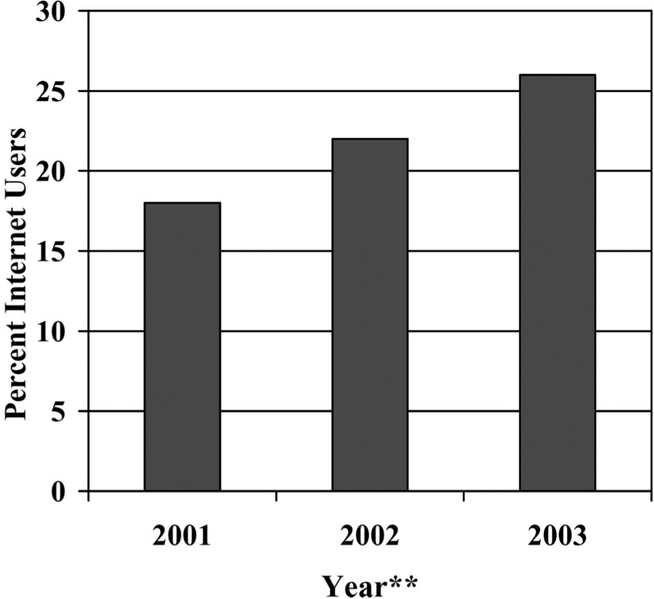

Among men reporting venues for meeting sex partners, the Internet was reported by 18% in 2001, 22% in 2002, and 26% in 2003. From January 2001 to October 2003, the percentage of MSM with syphilis who reported use of the Internet to meet sex partners increased by 8%, representing a relative increase of 9% (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Percent of men who have sex with men (MSM) early syphilis cases reporting use of the Internet to meet sex partners in Los Angeles County January 2001 through December 2003 (N = 198). Denominator values represent MSM diagnosed with early syphilis reporting venues to meet sex partners: 2001 (N = 96), 2002 (N = 395, N = 359).

Demographic, Clinical, and Behavioral Correlates of Internet Use to Meet Sex Partners

Overall, 23% (n = 198) of 850 MSM who were diagnosed with early syphilis infection reported meeting a sex partner through the Internet (Table 1). Of these, 49% were between the ages of 30 to 39, 90% reported having sex with an anonymous partner, 70% reported not using a condom, and 39% reported nonintravenous drug use (marijuana, methamphetamines, Viagra, nitrates/poppers, ecstasy, ketamine, cocaine). In bivariate analysis, white race (prevalence ratio [PR], 1.6; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.4–1.8), having anonymous sex partners (PR, 1.2; 95% CI, 1.1–1.3), anal insertive sex (prevalence ratio [PR], 1.1; 95% CI, 1.1–1.2), use of intravenous drugs (PR, 2.7; 95% CI, 1.1–6.7), and use of nonintravenous drugs (PR, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.1–1.8) were significantly associated with use of the Internet to meet sex partners. Controlling for race and sexual risk behaviors in multivariate analysis, white race (odds ratio [OR], 2.8; 95% CI, 1.8–4.6), having anonymous sex partners (OR, 3.4; 95% CI, 1.6–7.0), and nonintravenous drug use (OR, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.1–2.6) were associated with meeting sex partners through the Internet.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and Behavioral Characteristics of MSM Early Syphilis Cases Reporting Use (N = 198 and Non-use (N = 652) of the Internet to Meet Sex Partners January 2001 through December 2003

| Variable | Total | Internet Use (N = 198) |

Internet Non-Use (N = 652) |

Prevalence Ratio (95% Cl) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | ||||

| Age | |||||

| <20 | 12 | 2 (1) | 10 (1.5) | 0.6 | |

| 20–29* | 165 | 39 (20) | 126 (19) | ||

| 30–39 | 372 | 93 (47) | 279 (43) | ||

| 40–49 | 233 | 46 (23) | 187 (29) | ||

| 50+ | 68 | 18 (9) | 50 (8) | ||

| Race/ethnicity† /TD | |||||

| While | 412 | 132 (67) | 280 (43) | 1.6 (1.4–1.8) | <0.001 |

| Black | 90 | 13 (7) | 77 (12) | ||

| Hispanic | 300 | 40 (20) | 260 (40) | ||

| Other/mixed | 68 | 13 (7) | 35 (5) | ||

| Self-reported HIV Serostatus | |||||

| HIV Seropositive‡ | 508 | 123 (62) | 385 (59) | 1.1 (0.9–1.2) | 0.4 |

| Stage of syphilis§ | |||||

| Primary | 139 | 39 (20) | 100 (15) | 1.2 (1.0–1.3) | 0.03 |

| Secondary | 375 | 94 (47) | 281 (43) | ||

| Early latent | 336 | 65 (33) | 271 (42) | ||

| Behavioral risk factors¶ | |||||

| Anal insertive sex | 679 | 172 (87) | 507 (78) | 1.1 (1.1–1.2) | 0.001 |

| Anal receptive sex | 653 | 162 (82) | 491 (75) | 1.1 (1.0–1.2) | 0.03 |

| Oral sex‖ | 791 | 194 (99) | 597 (92) | 1.1 (1.0–1.1) | 0.003 |

| Anonymous partner** | 653 | 178 (90) | 475 (73) | 1.2 (1.1–1.3) | <0.001 |

| Condom use | 233 | 58 (29) | 175 (27) | 1.1 (0.8–1.3) | 0.7 |

| Incarceration†† | 31 | 4 (2) | 27 (4) | 0.5 (0.2–1.3) | 0.1 |

| IV drug use‡‡ | 18 | 8 (4) | 10 (1.5) | 2.7 (1.1–6.7) | 0.03 |

| Non-IV drug use§§ | 241 | 70 (35) | 171 (26) | 1.4 (1.1–1.8) | 0.005 |

Reference for logistic regression.

White vs. non-White used for prevalence ratio calculation.

HIV status provided by self-report during field interview and is not lab confirmed.

Primary and secondary (symptomatic) vs early latent used for odds ratio calculation.

Behavioral risk factors are collected for the “critical period” as defined in the methods section.

Calculations not performed for this association due to the cell count of ‘1’ for internet users not engaging in oral sex

Anonymous partner is defined as a sexual partner for whom the syphilis case was unable to provide any type of identifying or locating information.

Incarceration in the previous year.

IV Drug use includes use of injectable forms of heroin, methamphetamines, cocaine and others.

Non-IV drug use includes the use of oral, inhaled, and/or smoked forms of marijuana, methamphetamines, poppers/nitrates, sildenafil (Viagra), ketamine, ecstasy, cocaine.

Use of Other Venues to Meet Sex Partners

Compared with nonusers, Internet users were less likely to meet sex partners on the streets (PR, 0.3; 95% CI, 0.1–0.9; P = 0.02). Meeting sex partners at bars/clubs (PR, 0.9; 95% CI, 0.8–1.1), bathhouses/sex clubs (PR, 1.1; 95% CI, 0.8–1.4), parks (PR, 0.8; 95% CI, 0.4–1.7), and motels (PR, 2.2; 95% CI, 0.8–6.1) was not significantly different between Internet sex-seekers and non-Internet sex-seekers.

Discussion

Our results support previous findings that suggest that the use of the Internet among MSM diagnosed with early syphilis is emerging as 1 of the dominant venues for meeting sex partners among persons who self-report practicing unsafe sex.19 Increased access to the Internet among MSM in general and among those with early syphilis in particular and the ease and anonymity of encountering sexual partners provided by this venue could explain these trends. These rationales are supported by our findings that those who used the Internet to meet sex partners were more likely to be white, to have sex with anonymous partners, and to use recreational drugs. In addition, this study reveals the use of multiple venues, including commercial sex environments as well as the Internet by MSM with early syphilis. This overlapping of venue exposure could allow for increased opportunities for STD/HIV prevention education and intervention.

Risk behaviors associated with the Internet such as sex with multiple partners could amplify the risk of HIV/STD transmission when combined with other unsafe sexual behaviors and drug use.22,27,28 Among this population of MSM with early syphilis, sex with anonymous partners, noncondom use, and drug use were common. The possibility of concurrent transmission of HIV among MSM with early syphilis in Los Angeles is concerning and necessitates an ongoing public health response that includes but is not limited to the Internet.

Among this population of Internet-using MSM with early syphilis, white race was associated with meeting sex partners on the Internet, which might suggest a population with greater access to computers and the Internet. Use of the Internet to solicit sex requires computer access and ability as well as an environment that allows for discreet online interaction. Those with this capability could easily access online STD educational materials and clinical referral information if placed on popular web sites that promote solicitation of sex partners. This method of Internet education regarding STDs and HIV has been implemented on a popular gay web site by Klausner et al.29 Cooperation with these web sites is necessary if educational messages are to be delivered to at-risk populations frequenting these sites to solicit sex partners. However, this cooperation could be difficult to obtain as a result of the historical negative publicity surrounding HIV and STDs. The use of the Internet to deliver information about HIV and other STDs has been shown to be a frequently accessed source of information for those at risk that have access to the Internet. Two recently published studies have demonstrated a significantly greater percentage of persons seeking sex through the Internet also used the Internet to access information on STDs, HIV, and other health information compared with non-Internet users.21,30

Our study has the following strengths and limitations. We were able to compare demographic and behavioral information among Internet-using and non-Internet-using MSM diagnosed with early syphilis, thereby avoiding any differential of sexual risk. Our data were collected by face-to-face interviews by public health investigators near the time of syphilis diagnosis, reducing the likelihood of recall bias. Underreporting of certain behaviors could have occurred as a result of the sensitive nature of the interview material. We were not able to compare numbers of sexual partners as a result of data limitations, and sample size limited our ability to show significance for some behavioral factors. Our findings cannot be generalized to other MSM populations because all of these men had been recently diagnosed with syphilis and did not represent the MSM population as a whole. Further study is needed to evaluate the Internet as a venue for transmission and prevention of HIV and STDs in general and among MSM in particular.

Our results support the findings of other authors that the Internet is increasingly being used by MSM at risk for HIV and other STDs to find sexual partners. These trends could be explained by increased access to the Internet, the ease and anonymity of encountering sex partners, and the lack of long-term and established relationships that might encourage communication and disclosure of HIV status and/or other STDs, including syphilis. It is our recommendation that public health departments, community-based organizations, and other public health providers and policymakers should adopt intervention strategies like online outreach through chat rooms and discussion forums and online partner notification as has been recently described.31,32 Additional studies are needed to evaluate the role of the Internet as an STD transmission and prevention venue in all population groups that use the Internet to solicit sexual partners.

Footnotes

Presented in part at STD/HIV Prevention and the Internet, Washington DC, August 2003 (Abstract W2B).

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Primary and secondary syphilis among men who have sex with men—New York City, 2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2002; 51:853–856. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreak of syphilis among men who have sex with men—Southern California, 2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2001; 50:117–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Resurgent bacterial sexually transmitted disease among men who have sex with men—King County, Washington, 1997–1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1999; 48:773–777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jayaraman GC, Read RR, Singh A. Characteristics of individuals with male-to-male and heterosexually acquired infectious syphilis during an outbreak in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. Sex Transm Dis 2003; 30:315–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lacey HB, Higgins SP, Graham D. An outbreak of early syphilis: Cases from North Manchester General Hospital. Sex Transm Infect 2001; 77:311–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fenton KA, Nicoll A, Kinghorn G. Resurgence of syphilis in England: Time for more radical and nationally coordinated approaches. Sex Transm Infect 2001; 77:309–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ciesielski CA. Sexually transmitted disease in men who have sex with men: An epidemiologic review. Curr Infect Dis Rep 2003; 5:145–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen JL, Kodagoda D, Lawrence AM, et al. Rapid public health interventions in response to an outbreak of syphilis in Los Angeles. Sex Transm Dis 2002; 29:277–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klausner JD, Wolf W, Fischer-Ponce L, et al. Tracing a syphilis outbreak through cyberspace. JAMA 2000; 284:447–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kalb C. An old enemy is back. Newsweek. February 10, 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolitski RJ, Valdiserri RO, Denning PH, et al. Are we headed for a resurgence of the HIV epidemic among men who have sex with men? Am J Public Health 2001; 91:883–888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ekstrand ML, Stall RD, Paul JP, et al. Gay men report high rates of unprotected anal sex with partners of unknown or discordant HIV status. AIDS 1999; 23:1525–1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Increases in unsafe sex, rectal gonorrhea among men who have sex with men—San Francisco CA. 1994–1997. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1999; 48:45–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fleming DT, Wasserheit JN. From epidemiological synergy to public health policy and practice: The contribution of other sexually transmitted diseases to sexual transmission of HIV infection. Sex Transm Infect 1999; 75:3–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sexually Transmitted Disease Program, Los Angeles County Department of Health Services. Early Syphilis Surveillance Summary. July 2003:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taylor MM, Aynalem G, Smith L, et al. STD screening in bathhouses, sex clubs and other MSM venues in Los Angeles International Society for Sexually Transmitted Disease Research; Ottawa, Canada; July 2003; Abstract 0087.. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Beneden CA, O’Brien KO, Modesitt S, et al. Sexual behaviors in an urban bathhouse 15 years into the HIV epidemic. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2002; 30:522–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Binson D, Woods WJ, Pollack L, et al. Differential HIV risk in bathhouses and public cruising areas. Am J Public Health 2001; 91:1482–1486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lo TO, Samuel MC, Kent C, et al. Trends in increasing Internet use to seek male sexual partners among MSM syphilis cases, California, 2000–2002 STD/HIV Prevention and the Internet. Washington, DC, August 2003; Abstract W2D. [Google Scholar]

- 20.McFarlane M, Bull SS, Rietmeijer CA. The Internet as a newly emerging risk environment for sexually transmitted diseases. JAMA 2000; 284:443–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elford J, Bolding G, Sherr L. Seeking sex on the Internet and sexual risk behavior among gay men using London gyms. AIDS 2001; 15:1409–1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim AA, Kent C, McFarland W, et al. Cruising on the Internet highway. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2001; 28:89–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Halkitis PN, Parsons JT. Intentional unsafe sex (barebacking) among HIV-positive gay men who seek sexual partners on the Internet. AIDS Care 2003; 15:367–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Toomey KE, Rothenberg RB. Sex and cyberspace—Virtual networks leading to high-risk sex. JAMA 2000; 284:485–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Surveillance Case Definitions. Surveillance and Data Management. Program Operations: Guidelines for STD Prevention. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2000; S23–S25. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Surveillance Case Definitions. Partner Services. Program Operations: Guidelines for STD Prevention. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2000; PS 8–9. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bull SS, McFarlane M. Soliciting sex on the Internet: What are the risks for sexually transmitted diseases and HIV? Sex Transm Dis 2000; 27:545–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rietmeijer CA, Bull SS, McFarlane M. Sex and the Internet. AIDS 2001; 15:1433–1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klausner JD. Websites and STD services. Sex Transm Dis 1999;26:548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rietmeijer CA, Bull SS, McFarlane M, et al. Risks and benefits of the Internet for populations at risk for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) results of an STI clinic survey. Sex Transm Dis 2003; 30: 15–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Internet use and early syphilis infection among men who have sex with men—San Francisco, California, 1999–2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2003; 52:1229–1232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Using the Internet for partner notification of sexually transmitted diseases—Los Angeles County, California, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2004; 53:129–131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]