Abstract

Background:

The association between type 2 diabetes and hospital outcomes of sepsis remains controversial when severity of diabetes is not taken into consideration. We examined this association using nationwide and hospital-based databases.

Methods:

The first part of this study was mainly conducted using a nationwide database, which included 1.6 million type 2 diabetic patients. The diabetic complication burden was evaluated using the adapted Diabetes Complications Severity Index score (aDCSI score). In the second part, we used laboratory data from a distinct hospital-based database to make comparisons using regression analyses.

Results:

The nationwide study included 19,719 type 2 diabetic sepsis patients and an equal number of nondiabetic sepsis patients. The diabetic sepsis patients had an increased odds ratio (OR) of 1.14 (95% confidence interval 1.1–1.19) for hospital mortality. The OR for mortality increased as the complication burden increased [aDCSI scores of 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, and ⩾5 with ORs of 0.91, 0.87, 1.14, 1.25, 1.56, and 1.77 for mortality, respectively (all p < 0.001)].

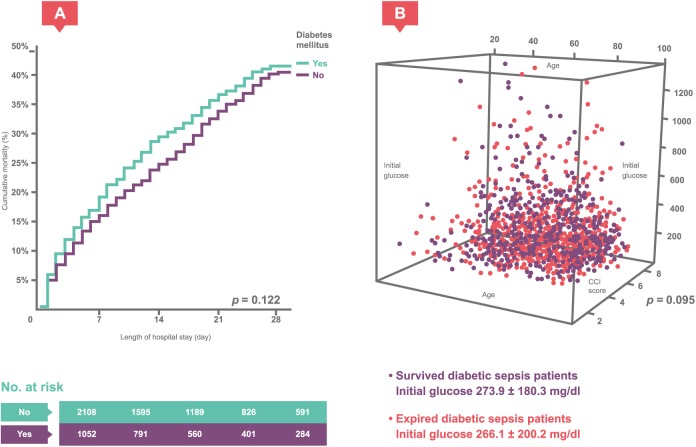

The hospital-based database included 1054 diabetic sepsis patients. Initial blood glucose levels did not differ significantly between the surviving and deceased diabetic sepsis patients: 273.9 ± 180.3 versus 266.1 ± 200.2 mg/dl (p = 0.095). Moreover, the surviving diabetic sepsis patients did not have lower glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c; %) values than the deceased patients: 8.4 ± 2.6 versus 8.0 ± 2.5 (p = 0.078).

Conclusions:

For type 2 diabetic sepsis patients, the diabetes-related complication burden was the major determinant of hospital mortality rather than diabetes per se, HbA1c level, or initial blood glucose level.

Keywords: diabetes complication severity index score, diabetes mellitus, sepsis

Introduction

Sepsis is a leading cause of mortality in critical care worldwide.1–3 In addition to mortality, sepsis may also cause long-term postsepsis cardiovascular disease.4 The reported incidence of sepsis varies; however, an undoubtedly increasing trend has been reported, reflecting the aging population and greater recognition of this condition. Furthermore, treating sepsis patients creates a significant national financial burden.

Diabetes is an important comorbid condition in sepsis because of its high prevalence.5 Diabetic patients are generally believed to be more prone to infections than the general population.6 However, the influence of diabetes on the outcome of sepsis remains inconclusive. Higher mortality rates in patients with diabetes have been reported;7–12 however, other studies have found no effect of diabetes13–16 or even protective effects of diabetes on sepsis.17–20 Within this debate, the most frequently proposed study limitation was study design. Epidemiological studies using large cohorts can avoid the selection bias that is frequently observed in hospital-based studies, but detailed clinical information is usually not available. Most importantly, many studies have failed to consider the influence of diabetic complication severity.

Hemoglobin A1C (HbA1c) is commonly used to measure blood glucose control in diabetic patients and has also been proposed as an independent predictor of hospital mortality in sepsis patients.21 However, its importance in diabetic sepsis patients requires further study because of limited data. Hyperglycemia has been shown to impair polymorphonuclear neutrophil function and cytokine production. However, high initial glucose levels were not reported to be associated with increased mortality in diabetic sepsis patients.22 Furthermore, tight glucose control did not seem to be significantly associated with reduced hospital mortality in critical patients.23,24 The influences of HbA1c and initial glucose levels on the outcome of sepsis deserve further investigation.

In the current study, using a representative nationwide database and a hospital-based database from multiple centers with laboratory data, we examined the association between type 2 diabetes and sepsis outcomes, specifically focusing on (a) whether type 2 diabetes itself increases the risk of mortality in hospitalized sepsis patients or whether risk of mortality depends on diabetic complication burdens, and (b) whether initial blood glucose level and HbA1c affect the hospital outcome.

Methods

Data sources and study participants

In this study, we used two distinct databases: (a) the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD), which included the Longitudinal Cohort of Diabetes Patients (LHDB) and the Longitudinal Health Insurance Database 2000 (LHID 2000); and (b) the hospital-based database from multiple centers.

Because the hospital-based database lacked longitudinal information for each type 2 diabetic individual, we used the LHDB and LHID 2000 to resolve this limitation. The LHDB and LHID 2000 recorded all the medical information for each individual, such as outpatient (at clinics or hospitals) and emergency department visits (at every hospital) and hospitalizations that were not limited to a single medical facility. Therefore, data from the NHIRD avoided recall bias and could be used in the longitudinal cohort study.

In contrast, the hospital-based database from multiple centers could provide laboratory data, such as HbA1c, initial blood glucose level, and culture results. However, the information was restricted to a single facility, and important information from other clinics or hospitals might be missed.

Nationwide database

In the first part of this study, we conducted a nationwide cohort study using data from the NHIRD. The diagnosis codes of the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) are used in the NHIRD to identify specific diagnoses. Data for sepsis patients were retrieved using the ICD-9-CM code 038 plus a main infection diagnosis with antibiotics prescription. The accuracy of sepsis diagnosis in the NHIRD has been validated in previous studies.25 The infection site classification was conducted following the criteria developed by Angus and colleagues.26

The patients were classified as using certain drugs if they took the drugs for more than 1 month within a 1-year period prior to the index hospitalization (the first admission for sepsis). The index date was defined as the first day of index hospitalization. The drugs, procedures, special modalities, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and length of hospital stay were recorded using the claims data of the NHIRD.

Initially, we used the LHDB of the NHIRD, which contains randomized selected data (a total of 1.68 million enrollees from 1999 to 2012) from patients with newly diagnosed diabetes to retrieve the study cohort of type 2 diabetic first-episode sepsis patients.27 The patients in the study cohort had to have been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes at least 1 year prior to the index hospitalization to allow for the evaluation of diabetic complication burden by using the adjusted Diabetes Complications Severity Index score (aDCSI score).28,29

The Diabetes Complications Severity Index (DCSI) was first developed by Young and coworkers.28 The DCSI is a useful tool for adjusting for the baseline severity of diabetic complications and predicting hospital mortality. The aDCSI score was modified from the DCSI score and had been validated in the NHIRD.30 The aDCSI score included seven categories of complications: cardiovascular disease, nephropathy, neuropathy, retinopathy, peripheral vascular disease, stroke, and metabolic emergency events.

The comparison cohort, which was composed of nondiabetic first-episode sepsis patients, was retrieved from the LHID 2000. The LHID 2000 used in this study contains medical information for 1 million beneficiaries, randomly sampled from the registry of all beneficiaries in 2000. The study cohort from the LHDB and the comparison cohort from the LHID 2000 were matched in a 1:1 ratio by propensity scoring. For each patient, we calculated the propensity score using multivariate logistic regression by entering age, sex, income, urbanization level, hospital level, baseline comorbidities, and infection sites from the LHDB and LHID 2000. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of China Medical University (CMUH104-REC2-115).

Hospital-based database

In the second part of this study, we retrieved the first-episode data of type 2 diabetic and nondiabetic sepsis patients from 2006 to 2012 in the electronic databases of three medical centers, Taipei and Taichung Veterans General Hospitals, and the Lin-Kou Medical Center of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital. The type 2 diabetic and nondiabetic sepsis patients were matched by age and sex. Laboratory data, including initial blood glucose level, HbA1c, and initial lactate level; hospital courses, including ICU admission and total and 28-day hospital mortality; received procedures (including mechanical ventilation and hemodialysis); and blood culture results were collected for further analysis. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Taipei Veterans General Hospital (2018-02-003BC), Taichung Veterans General Hospital (CE18102A), and Lin-Kou Medical Center of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (201701502B0C501).

The selection process of participants from the nationwide and hospital-based databases is shown in Supplement Figure 1. Most of the enrolled type 2 diabetic sepsis patients in the hospital database from multiple centers could be traced and linked to the nationwide database by a specific matching method.31 However, matching was not allowed in Taiwan at the time of this study. Regarding the data in the hospital-based database, initial blood glucose levels were measured on the day of admission, either in the emergency department or on the ward, before patients received any acute glucose-lowering injection therapy (i.e. insulin). HbA1c levels were assessed during a 1-month period prior to the admission day.

Statistical analyses

Differences in demographic characteristics, comorbidities, medications, and laboratory data were examined using the chi-square test, the Mann–Whitney test and a two-sample t test. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were calculated using a logistic regression model. A Kaplan–Meier analysis with the log-rank test was performed to compare hospital outcomes among type 2 diabetic sepsis patients with different initial blood glucose levels and HbA1c values. Statistical analyses were performed using the SAS 9.4 statistical package (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). A p value of 0.05 was considered indicative of significance.

Results

First part: nationwide database

After propensity-score matching, data collected between 1999 and 2012 for 19,719 type 2 diabetic first-episode sepsis patients and an equal number of nondiabetic first-episode sepsis patients were retrieved as the study and comparison cohorts from the LHDB and LHID 2000. Demographic characteristics, comorbidities, medications, infection sites, and received procedures of the study and comparison cohorts are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Nationwide database: demographic characteristics, comorbidities, and medications in type 2 diabetic and nondiabetic sepsis patients before and after propensity-score matching.

| Before matching | PS matching | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | All sepsis

patients (n = 120,439) |

Non-DM (n = 21,576, 17.91%) |

DM (n = 98,863, 82.09%) |

p value | Non-DM (n = 19,719) |

DM (n = 19,719) |

Standardized difference | ||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||||

| Sex | <0.0001 | ||||||||||

| Female | 54,767 | 8913 | 41.31 | 45,854 | 46.38 | 7990 | 40.52 | 7884 | 39.98 | 0.011 | |

| Male | 65,672 | 12,663 | 58.69 | 53,009 | 53.62 | 11729 | 59.48 | 11835 | 60.02 | 0.011 | |

| Age, years | <0.0001 | ||||||||||

| 20–29 years | 1529 | 953 | 4.42 | 576 | 0.58 | 530 | 2.69 | 164 | 0.83 | 0.142 | |

| 30–39 years | 3892 | 1439 | 6.67 | 2453 | 2.48 | 1077 | 5.46 | 631 | 3.2 | 0.111 | |

| 40–49 years | 9638 | 2106 | 9.76 | 7532 | 7.62 | 1814 | 9.20 | 1755 | 8.9 | 0.01 | |

| 50–59 years | 17,755 | 2587 | 11.99 | 15,168 | 15.34 | 2318 | 11.76 | 2910 | 14.76 | 0.089 | |

| 60–69 years | 22,552 | 2996 | 13.89 | 19,556 | 19.78 | 2814 | 14.27 | 3694 | 18.73 | 0.12 | |

| 70–79 years | 33,327 | 5179 | 24 | 28,148 | 28.47 | 5012 | 25.42 | 5404 | 27.41 | 0.045 | |

| ⩾80 years | 31,746 | 6316 | 29.27 | 25,430 | 25.72 | 6154 | 31.21 | 5161 | 26.17 | 0.112 | |

| Mean (SD)* | 68.90 (15.08) | 66.89 (18.53) | 69.33 (14.17) | <0.0001 | 68.64 (17.39) | 68.80 (14.88) | 0.01 | ||||

| Insurance premium (NT dollars) | <0.0001 | ||||||||||

| <20,000 | 75,927 | 16,048 | 74.38 | 59,879 | 60.57 | 14,576 | 73.92 | 14433 | 73.19 | 0.016 | |

| 20,000 ⩽ insurance premium < 40,000 | 36,824 | 4558 | 21.13 | 32,266 | 32.64 | 4256 | 21.58 | 4365 | 22.14 | 0.013 | |

| 40,000 ⩽ insurance premium <60,000 | 5930 | 890 | 4.12 | 5040 | 5.1 | 820 | 4.16 | 839 | 4.25 | 0.005 | |

| 60,000 ⩽ insurance premium | 1758 | 80 | 0.37 | 1678 | 1.7 | 67 | 0.34 | 82 | 0.42 | 0.012 | |

| Urbanization level | <0.0001 | ||||||||||

| 1 (highest) | 29,506 | 5407 | 25.1 | 24,099 | 24.38 | 4902 | 24.86 | 4884 | 24.77 | 0.002 | |

| 2 | 33,242 | 5884 | 27.31 | 27,358 | 27.67 | 5362 | 27.19 | 5306 | 26.91 | 0.006 | |

| 3 | 19,906 | 3487 | 16.18 | 16,419 | 16.61 | 3180 | 16.13 | 3186 | 16.16 | 0.001 | |

| 4 | 19,589 | 3439 | 15.96 | 16150 | 16.34 | 3199 | 16.22 | 3250 | 16.48 | 0.007 | |

| 5 (lowest) | 18,166 | 3329 | 15.45 | 14,837 | 15.01 | 3076 | 15.6 | 3093 | 15.69 | 0.002 | |

| Hospital level | <0.0001 | ||||||||||

| Medical center | 38,933 | 7570 | 35.09 | 31,363 | 31.72 | 6836 | 34.67 | 6856 | 34.77 | 0.002 | |

| Regional hospital | 54,017 | 9307 | 43.15 | 44,710 | 45.22 | 8554 | 43.38 | 8554 | 43.38 | 0 | |

| District hospital | 27,484 | 4694 | 21.76 | 22,790 | 23.05 | 4329 | 21.95 | 4309 | 21.85 | 0.002 | |

| Baseline comorbidities | |||||||||||

| HTN | 86,491 | 12,782 | 59.24 | 73,709 | 74.56 | <0.0001 | 12,446 | 63.12 | 12360 | 62.68 | 0.009 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 51,971 | 5284 | 24.49 | 46,687 | 47.22 | <0.0001 | 5182 | 26.28 | 5148 | 26.11 | 0.004 |

| COPD | 52,796 | 9579 | 44.40 | 43,217 | 43.71 | <0.0001 | 9484 | 48.10 | 9524 | 48.30 | 0.004 |

| CLD | 39,563 | 6605 | 30.61 | 32,958 | 33.34 | <0.0001 | 6518 | 33.05 | 6502 | 32.97 | 0.002 |

| CKD | 46,873 | 5362 | 24.85 | 41,511 | 41.99 | <0.0001 | 5324 | 27.00 | 5334 | 27.05 | 0.001 |

| PAOD | 16,240 | 2036 | 9.44 | 14204 | 14.37 | <0.0001 | 2016 | 10.22 | 2014 | 10.21 | 0 |

| IHD | 51,633 | 6852 | 31.76 | 44,781 | 45.30 | <0.0001 | 6783 | 34.40 | 6758 | 34.27 | 0.003 |

| Stroke | 52,615 | 8131 | 37.69 | 44,484 | 45.00 | <0.0001 | 8056 | 40.85 | 8071 | 40.93 | 0.002 |

| Cancer | 33,639 | 4452 | 20.63 | 29,187 | 29.52 | <0.0001 | 4422 | 22.43 | 4387 | 22.25 | 0.004 |

| Drugs | |||||||||||

| NSAIDs | 59,580 | 10,021 | 46.45 | 49,559 | 50.13 | <0.0001 | 9588 | 48.62 | 9401 | 47.67 | 0.019 |

| Aspirin | 13,350 | 1980 | 9.18 | 11,370 | 11.50 | <0.0001 | 1938 | 9.83 | 2150 | 10.90 | 0.035 |

| Statins | 18,869 | 1014 | 4.70 | 17,855 | 18.06 | <0.0001 | 995 | 5.05 | 2178 | 11.05 | 0.222 |

| Biguanides | 42,469 | – | – | 42,469 | 42.96 | – | – | – | 7600 | 38.54 | – |

| DPP-4 inhibitors | 4759 | – | – | 4759 | 4.81 | – | – | – | 659 | 3.34 | – |

| Sulfonylureas | 47,483 | – | – | 47,483 | 48.03 | – | – | – | 8631 | 43.77 | – |

| TZDs | 6443 | – | – | 6443 | 6.52 | – | – | – | 961 | 4.87 | – |

| Other OADs | 18,113 | – | – | 18,113 | 18.32 | – | – | – | 2911 | 14.76 | – |

| Insulin | 34,201 | – | – | 34,201 | 34.59 | – | – | – | 6297 | 31.93 | – |

| Immunosuppressants | 447 | 74 | 0.34 | 373 | 0.38 | 0.4526 | 71 | 0.36 | 52 | 0.26 | 0.017 |

| Steroids | 29,167 | 4676 | 21.67 | 24,491 | 24.77 | <0.0001 | 4578 | 23.22 | 4681 | 23.74 | 0.012 |

| Infection site | |||||||||||

| Respiratory | 44,511 | 8375 | 38.82 | 36,136 | 36.55 | <0.0001 | 7876 | 39.94 | 7420 | 37.63 | 0.047 |

| Genitourinary | 39,244 | 5979 | 27.71 | 33,265 | 33.65 | <0.0001 | 5419 | 27.48 | 6266 | 31.78 | 0.094 |

| Gastrointestinal | 9562 | 1817 | 8.42 | 7745 | 7.83 | <0.0001 | 1607 | 8.15 | 1672 | 8.48 | 0.012 |

| Soft tissue/musculoskeletal | 6682 | 979 | 4.54 | 5703 | 5.77 | <0.0001 | 868 | 4.40 | 1239 | 6.28 | 0.084 |

| Central nervous | 785 | 135 | 0.63 | 650 | 0.66 | <0.0001 | 111 | 0.56 | 139 | 0.70 | 0.018 |

| Cardiovascular | 801 | 164 | 0.76 | 637 | 0.64 | <0.0001 | 143 | 0.73 | 135 | 0.68 | 0.005 |

| Device related | 1924 | 286 | 1.33 | 1638 | 1.66 | <0.0001 | 278 | 1.41 | 275 | 1.39 | 0.001 |

| Others | 10,006 | 1970 | 9.13 | 8036 | 8.13 | <0.0001 | 1745 | 8.85 | 1726 | 8.75 | 0.003 |

| aDCSI score | |||||||||||

| 0 | 24,134 | – | – | 24,134 | 24.41 | – | – | – | 5905 | 29.95 | – |

| 1 | 11,625 | – | – | 11,625 | 11.76 | – | – | – | 2218 | 11.25 | – |

| 2 | 25,030 | – | – | 25,030 | 25.32 | – | – | – | 5340 | 27.08 | – |

| 3 | 10,782 | – | – | 10,782 | 10.91 | – | – | – | 1876 | 9.51 | – |

| 4 | 14,575 | – | – | 14,575 | 14.74 | – | – | – | 2568 | 13.02 | – |

| ⩾5 | 12,171 | – | – | 12,171 | 12.86 | – | – | – | 1812 | 9.19 | – |

| Procedures | |||||||||||

| Nasogastric tube feeding | 71,665 | 12,314 | 57.07 | 59,351 | 60.03 | <0.0001 | |||||

| Central venous catheter insertion | 49,283 | 8335 | 38.63 | 40,948 | 41.42 | <0.0001 | |||||

| Blood transfusion | 61,611 | 10,919 | 50.61 | 50,692 | 51.27 | <0.0001 | |||||

| Hemodialysis | 13,219 | 1786 | 8.28 | 11,433 | 11.56 | <0.0001 | |||||

| ICU admission | 59,583 | 10,060 | 46.63 | 49,523 | 50.09 | 0.0002 | |||||

| NIPPV | 8499 | 1456 | 6.75 | 7043 | 7.12 | <0.0001 | |||||

| Mechanical ventilation | 47,205 | 8237 | 38.18 | 38,968 | 39.42 | <0.0001 | |||||

Results were obtained using the Chi-square test.

Results were obtained using the two-sample t test.

PS matching include variables of age, sex, insurance premium, urbanization level, hospital level, baseline comorbidities, and infection site.

aDSCI, adapted Diabetes Complications Severity Index; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CLD, chronic liver disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; DPP-4 inhibitors, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor; HTN, hypertension; ICU, intensive care unit; IHD, ischemic heart disease; NIPPV, non-invasive positive pressure ventilation; NT dollars, national Taiwan dollars; OADs, oral antidiabetic drugs; PAOD, peripheral arterial occlusion disease; PS, propensity score; TZD, thiazolidinedione.

Before matching, the type 2 diabetic sepsis patients had a higher prevalence of sepsis in the genitourinary tract (33.65% versus 27.71%) and soft tissue/musculoskeletal system (5.77% versus 4.54%, both p < 0.0001). Additionally, the diabetic sepsis patients more frequently received respiratory support (mechanical ventilation: 39.42% versus 38.18%; noninvasive positive pressure ventilation: 7.12% versus 6.75%, both p < 0.0001) and dialysis (11.56% versus 8.28%, p < 0.0001) compared with the nondiabetic sepsis patients.

After propensity-score matching in a multivariate analysis, type 2 diabetic sepsis patients had an increased OR of 1.14 (95% CI 1.10–1.19, p < 0.0001) for mortality after adjusting for age, sex, insurance premium (as a proxy for household income), urbanization level, and hospital level (Table 2).

Table 2.

Nationwide database: odds ratio of mortality related to type 2 diabetes and its complication severity in different adjusted models.

| Characteristics | Die (n = 16205) | Crude | Adjusted model 1 | Adjusted model 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | (95% CI) | p value | OR | (95% CI) | p value | OR | (95% CI) | p value | ||

| DM | ||||||||||

| No | 7811 | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | |||

| Yes | 8394 | 1.13 | (1.09–1.18) | <0.0001 | 1.14 | (1.1–1.19) | <0.0001 | – | – | – |

| aDCSI score | ||||||||||

| 0 | 2034 | 0.80 | (0.75–0.85) | <0.0001 | – | – | – | 0.91 | (0.85–0.97) | 0.0033 |

| 1 | 781 | 0.83 | (0.76–0.91) | <0.0001 | – | – | – | 0.87 | (0.8–0.96) | 0.0053 |

| 2 | 2299 | 1.15 | (1.08–1.23) | <0.0001 | – | – | – | 1.14 | (1.07–1.22) | <0.0001 |

| 3 | 875 | 1.33 | (1.21–1.47) | <0.0001 | – | – | – | 1.25 | (1.13–1.38) | <0.0001 |

| 4 | 1376 | 1.76 | (1.62–1.91) | <0.0001 | – | – | – | 1.56 | (1.43–1.7) | <0.0001 |

| ⩾5 | 1029 | 2.00 | (1.82–2.21) | <0.0001 | – | – | – | 1.77 | (1.61–1.96) | <0.0001 |

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Female | 5685 | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | |||

| Male | 10,520 | 1.45 | (1.39–1.51) | <0.0001 | 1.56 | (1.5–1.63) | <0.0001 | 1.55 | (1.49–1.62) | <0.0001 |

| Age, years | ||||||||||

| 20–29 years | 121 | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | |||

| 30–39 years | 385 | 1.38 | (1.1–1.73) | 0.0055 | 1.37 | (1.09–1.72) | 0.0071 | 1.38 | (1.1–1.74) | 0.0053 |

| 40–49 years | 1090 | 2.08 | (1.69–2.57) | <0.0001 | 2.07 | (1.68–2.56) | <0.0001 | 2.11 | (1.71–2.61) | <0.0001 |

| 50–59 years | 1616 | 2.12 | (1.73–2.6) | <0.0001 | 2.19 | (1.78–2.69) | <0.0001 | 2.21 | (1.8–2.72) | <0.0001 |

| 60–69 years | 2372 | 2.72 | (2.22–3.33) | <0.0001 | 2.72 | (2.22–3.33) | <0.0001 | 2.71 | (2.21–3.32) | <0.0001 |

| 70–79 years | 4635 | 3.80 | (3.11–4.64) | <0.0001 | 3.69 | (3.02–4.51) | <0.0001 | 3.57 | (2.92–4.37) | <0.0001 |

| ⩾80 years | 5986 | 5.32 | (4.36–6.49) | <0.0001 | 5.33 | (4.36–6.52) | <0.0001 | 5.10 | (4.17–6.24) | <0.0001 |

| Insurance premium (NT dollars) | ||||||||||

| <20000 | 12,766 | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | |||

| 20,000 ⩽ insurance premium < 40,000 | 2937 | 0.66 | (0.63–0.69) | <0.0001 | 0.71 | (0.68–0.75) | <0.0001 | 0.72 | (0.68–0.76) | <0.0001 |

| 40,000 ⩽ insurance premium < 60,000 | 458 | 0.49 | (0.43–0.54) | <0.0001 | 0.60 | (0.54–0.68) | <0.0001 | 0.62 | (0.55–0.69) | <0.0001 |

| 60,000 ⩽ insurance premium | 44 | 0.53 | (0.37–0.76) | 0.0005 | 0.67 | (0.47–0.96) | 0.0271 | 0.70 | (0.49–1) | 0.0521 |

| Urbanization level | ||||||||||

| 1 (highest) | 4004 | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | |||

| 2 | 4274 | 0.97 | (0.91–1.02) | 0.2171 | 1.00 | (0.94–1.06) | 0.9948 | 1.01 | (0.95–1.07) | 0.86 |

| 3 | 2655 | 1.03 | (0.97–1.1) | 0.3179 | 1.05 | (0.98–1.12) | 0.134 | 1.06 | (0.99–1.13) | 0.1103 |

| 4 | 2692 | 1.03 | (0.97–1.1) | 0.2939 | 1.03 | (0.96–1.1) | 0.3671 | 1.04 | (0.97–1.11) | 0.2698 |

| 5 (lowest) | 2580 | 1.04 | (0.97–1.11) | 0.2565 | 1.06 | (0.99–1.14) | 0.0723 | 1.07 | (1–1.15) | 0.0409 |

| Hospital level | ||||||||||

| Medical center | 5705 | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | |||

| Regional hospital | 6894 | 0.94 | (0.9–0.99) | 0.0152 | 0.88 | (0.84–0.92) | <0.0001 | 0.87 | (0.83–0.92) | <0.0001 |

| District hospital | 3606 | 1.00 | (0.95–1.06) | 0.9066 | 0.83 | (0.78–0.88) | <0.0001 | 0.81 | (0.77–0.86) | <0.0001 |

| Baseline comorbidities | ||||||||||

| HTN | 10,716 | 1.27 | (1.21–1.32) | <0.0001 | 0.95 | (0.89–1.01) | 0.1142 | – | – | – |

| Hyperlipidemia | 3820 | 0.79 | (0.76–0.83) | <0.0001 | 0.90 | (0.84–0.96) | 0.0014 | – | – | – |

| COPD | 8647 | 1.42 | (1.37–1.48) | <0.0001 | 0.91 | (0.86–0.97) | 0.0018 | – | – | – |

| CLD | 5444 | 1.05 | (1–1.09) | 0.0403 | 1.09 | (1.03–1.16) | 0.0045 | – | – | – |

| CKD | 5031 | 1.41 | (1.35–1.47) | <0.0001 | 0.99 | (0.93–1.06) | 0.7966 | – | – | – |

| PAOD | 1910 | 1.33 | (1.25–1.42) | <0.0001 | 1.08 | (0.99–1.18) | 0.085 | – | – | – |

| IHD | 6116 | 1.29 | (1.24–1.35) | <0.0001 | 0.95 | (0.89–1.01) | 0.1177 | – | – | – |

| Cancer | 4836 | 2.06 | (1.97–2.16) | <0.0001 | 3.02 | (2.83–3.22) | <0.0001 | – | – | – |

| Stroke | 7409 | 1.40 | (1.35–1.46) | <0.0001 | 1.21 | (1.16–1.27) | <0.0001 | – | – | – |

| Procedures | ||||||||||

| Nasogastric tube feeding | 13,777 | 7.84 | (7.46–8.25) | <0.0001 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Central venous catheter insertion | 9973 | 4.74 | (4.54–4.95) | <0.0001 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Blood transfusion | 11,716 | 4.01 | (3.84–4.19) | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Hemodialysis | 2236 | 2.83 | (2.63–3.04) | <0.0001 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| ICU admission | 10,893 | 3.87 | (3.71–4.03) | <0.0001 | ||||||

| NIPPV | 1591 | 2.14 | (1.98–2.32) | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Mechanical ventilation | 10,564 | 6.62 | (6.33–6.92) | <0.0001 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Cardiopulmonary cerebral resuscitation | 3893 | 10.36 | (9.52–11.27) | <0.0001 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

Model 1: adjusted for DM, age, sex, insurance premium, urbanization level, hospital level, and baseline comorbidities.

Model 2: adjusted for aDSCI score, age, sex, insurance premium, urbanization level, and hospital level.

In model 2, baseline comorbidities were not put into the model for adjustment because of the collinearity.

aDSCI, adapted Diabetes Complications Severity Index; CI, confidence interval; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CLD, chronic liver disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; HTN, hypertension; ICU, intensive care unit; IHD, ischemic heart disease; NIPPV, non-invasive positive pressure ventilation, NT dollars, national Taiwan dollars; OR, odds ratio; PAOD, peripheral arterial occlusion disease.

According to diabetic complication burdens in the regression analysis of the main model, the patients with aDCSI scores of 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, and ⩾5 had ORs of 0.91 (95% CI 0.85–0.97), 0.87 (95% CI 0.80–0.96), 1.14 (95% CI 1.07–1.22), 1.25 (95% CI 1.13–1.38), 1.56 (95% CI 1.43–1.70), and 1.77 (95% CI 1.61–1.96) for hospital mortality of sepsis, respectively (all p < 0.001 and p for trend < 0.001). In the subgroup analysis, the type 2 diabetic sepsis patients with higher aDCSI scores had increased ORs for mortality compared with those with lower scores in every age subgroup (per 10 years), especially in the range of 30–39 years (Supplement Figure 2).

We also stratified the sepsis patients according to infection site, and we found that the type 2 diabetic sepsis patients had increased adjusted ORs in every origin except the gastrointestinal system (adjusted OR of 2.29 (95% CI 1.36–3.86) for the central nervous system, adjusted OR of 1.26 (95% CI 1.18–1.35) for the respiratory system, adjusted OR of 1.88 (95% CI 1.14–3.10) for the cardiovascular system, adjusted OR of 1.58 (95% CI 1.46–1.72) for the genitourinary system, adjusted OR of 1.32 (95% CI 1.08–1.61) for soft tissue, and adjusted OR of 0.99 (95% CI 0.86–1.14) for the gastrointestinal system; Supplement Table 1).

Second part: hospital-based database

From the hospital-based database, we initially included data for 4984 sepsis patients collected between 2006 and 2012. After matching for age and sex, 1054 type 2 diabetic sepsis patients and 2108 nondiabetic sepsis patients were included for further analysis.

The type 2 diabetic sepsis patients had a higher initial creatinine level (2.4 ± 2.1 versus 1.9 ± 1.8, p < 0.001) and prevalence of receiving hemodialysis during hospitalization (23.2% versus 16.9%, p < 0.001; Table 3). Furthermore, the type 2 diabetic sepsis patients had a higher ICU admission rate (57.5% versus 55.3%, p = 0.249) and acute physiologic and chronic health II (APACH II) score (25.3 ± 7.1 versus 24.9 ± 7.0, p = 0.292) than the nondiabetic sepsis patients, although the p value did not reach significance. Accordingly, the type 2 diabetic sepsis patients had a higher hospital mortality rate (45.2% versus 42.3%, p = 0.138) and 28-day mortality rate (35.5% versus 32.8%, p = 0.147) than the nondiabetic sepsis patients. The type 2 diabetic sepsis patients had a higher prevalence of Gram-positive coccus bacteremia (16.8% versus 14.4%, p = 0.089) but a lower prevalence of Gram-negative bacillus bacteremia (19.1% versus 20.7%, p = 0.294) than the nondiabetic sepsis patients.

Table 3.

Demographic characteristics, comorbidities, laboratory data, hospital course, and outcomes of matched type 2 diabetic and nondiabetic sepsis patients.

| Variables | Total (n = 3162) | DM | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 1054) | No (n = 2108) | |||

| Age¶ | 70.4 ± 13.1 | 70.3 ± 12.9 | 70.4 ± 13.1 | 0.779 |

| Male | 1956 (61.9) | 652 (61.9) | 1304 (61.9) | 1.000 |

| Hospital mortality | 1368 (43.3) | 476 (45.2) | 892 (42.3) | 0.138 |

| 28-day mortality | 1066 (33.7) | 374 (35.5) | 692 (32.8) | 0.147 |

| Hemodialysis | 602 (19.0) | 245 (23.2) | 357 (16.9) | <0.001 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 1897 (60.0) | 658 (62.4) | 1239 (58.8) | 0.053 |

| ICU admission | 1771 (56.0) | 606 (57.5) | 1165 (55.3) | 0.249 |

| APACH II score (n = 557 versus 1063)¶ |

25.0 ± 7.0 | 25.3 ± 7.1 | 24.9 ±7.0 | 0.292 |

| Length of ICU stay¶ | 15.6 ± 14.3 | 14.6 ± 13.8 | 16.0 ± 14.6 | 0.020 |

| Length of hospital stay¶ | 23.5 ±25.5 | 23.0 ± 27.5 | 23.7 ± 24.4 | 0.214 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| HTN | 931 (29.4) | 463 (43.9) | 468 (22.2) | <0.001 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 54 (1.7) | 36 (3.4) | 18 (0.9) | <0.001 |

| COPD | 287 (9.1) | 72 (6.8) | 215 (10.2) | 0.002 |

| CLD | 244 (7.7) | 81 (7.7) | 163 (7.7) | 1.000 |

| CKD | 1019 (32.2) | 410 (38.9) | 609 (28.9) | <0.001 |

| PAOD | 80 (2.5) | 43 (4.1) | 37 (1.8) | <0.001 |

| IHD | 124 (3.9) | 55 (5.2) | 69 (3.3) | 0.010 |

| Cancer | 958 (30.3) | 226 (21.4) | 732 (34.7) | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 273 (8.6) | 120 (11.4) | 153 (7.3) | <0.001 |

| CCI score¶ | 3.4 ± 2.7 | 3.7 ± 2.4 | 3.2 ± 2.8 | <0.001 |

| Bacterial cultures | ||||

| GPC | 481 (15.2) | 177 (16.8) | 304 (14.4) | 0.089 |

| GNB | 638 (20.2) | 201 (19.1) | 437 (20.7) | 0.294 |

| Laboratory data | ||||

| Glucose | 191.4 ± 141.8 | 270.4 ± 189.4 | 149.1 ± 80.8 | <0.001 |

| WBC (×103) | 13.2 ±13.5 | 14.2 ± 12.1 | 12.7 ±14.1 | <0.001 |

| Hb | 12.0 ± 2.7 | 12.2 ± 2.6 | 12.0 ± 2.7 | 0.057 |

| PLT (×106) | 1.9 ± 1.3 | 2.1 ± 1.6 | 1.9 ± 1.2 | <0.001 |

| Cr | 2.1 ± 1.9 | 2.4 ± 2.1 | 1.9 ±1.8 | <0.001 |

| Bilirubin | 0.9 ± 2.0 | 0.8 ± 1.9 | 0.9 ± 2.0 | <0.001 |

| Lactate | 31.7 ± 31.3 | 32.9 ± 34.0 | 31.0 ± 29.7 | 0.259 |

Results were obtained using the Chi-square test.

Results were obtained using the Mann–Whitney test.

Continuous data are expressed as mean ± SD. Categorical data are expressed as numbers (percentage).

APACH, acute physiologic and chronic health; CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CLD, chronic liver disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; Cr, creatinine; DM, diabetes mellitus; GNB, Gram-negative bacillus (GNB); GPC, Gram-positive coccus; Hb, hemoglobin; HTN, hypertension; ICU, intensive care unit; IHD, ischemic heart disease; PAOD, peripheral arterial occlusion disease; PLT, platelets; SD, standard deviation; WBC, white blood count.

In the univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses, type 2 diabetes was associated with an increased risk of hospital mortality during the sepsis course (adjusted OR = 1.31, 95% CI 1.11–1.54, p = 0.002). This result was similar to that obtained for the nationwide database. The Kaplan–Meier analysis with log-rank test also showed a difference in hospital mortality between the type 2 diabetic and nondiabetic sepsis patients [p = 0.122; Figure 1(a)].

Figure 1.

Diabetic sepsis patients’ initial glucose.

(a) The Kaplan–Meier analysis with log-rank test showed the difference in the hospital course of mortality between the type 2 diabetic and nondiabetic sepsis patients. (b) Scatter plot of initial blood glucose levels in the surviving and deceased type 2 diabetic sepsis patients, which did not differ significantly: 273.9 ± 180.3 mg/dl versus 266.1 ± 200.2 mg/dl (p = 0.095).

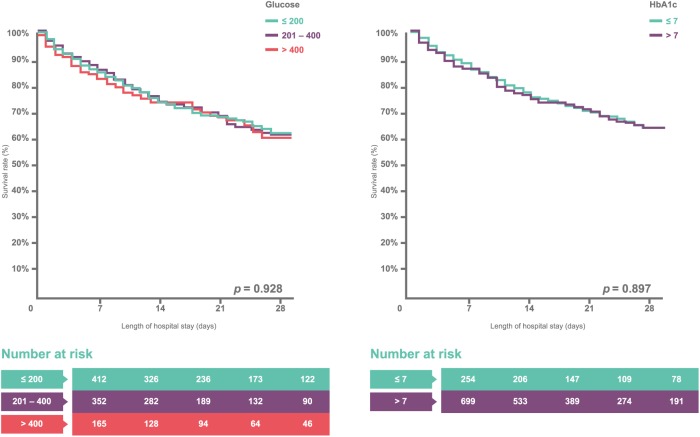

The 1054 type 2 diabetic sepsis patients were divided into two groups, surviving and deceased patients, for further comparison. Initial blood glucose levels between the surviving and deceased diabetic sepsis patient groups did not differ significantly: 273.9 ± 180.3 versus 266.1 ± 200.2 [mg/dl; p = 0.095; Figure 1(b)]. Furthermore, the surviving diabetic sepsis patients did not have lower HbA1c (%) levels than the deceased diabetic sepsis patients: 8.4 ± 2.6 versus 8.0 ± 2.5 (p = 0.078; Supplement Table 2). The univariate analysis, another logistic regression analysis that included age, sex, Charlson comorbidity index score, and important laboratory data, showed an OR of 1.00 (95% CI 1.00–1.00, p = 0.532) for initial glucose levels and 0.94 (95% CI 0.86–1.02, p = 0.143) for HbA1c. The Kaplan–Meier analysis with log-rank test also showed that hospital mortality did not differ among type 2 diabetic sepsis patients with different initial blood glucose levels (⩽200, 201–400, and >400 mg/dl) and HbA1c values (⩽7 and >7%) [Figure 2(a) and (b)].

Figure 2.

Survival rate versus glucose and HbA1c.

(a) The Kaplan–Meier analysis with log-rank test for the hospital course of mortality among type 2 diabetic sepsis patients with different initial blood glucose levels at admission (⩽200, 201–400, and >400). (b) The Kaplan–Meier analysis with log-rank test for the hospital course of mortality between type 2 diabetic sepsis patients with HbA1c levels > 7 and ⩽7.

Sensitivity analysis

We analyzed multiple models adjusted for drugs, procedures, and infection sites to examine the stability of the main model, that is, the multivariate analysis based on the aDCSI score. The models showed that the hospital mortality rate of sepsis increased as the aDCSI score increased (Supplement Table 3).

In the sensitivity analysis, we used a stricter inclusion criterion for HbA1c collection: the HbA1c needed to be collected within 3 days of admission. A total of 366 (sample size reduced from 953 to 366) type 2 diabetic sepsis patients were included. The difference in hospital mortality rate remained unchanged (a hospital mortality rate of 39.5% for HbA1c ⩽ 7 and 35.2% for HbA1c > 7). In addition, we conducted another sensitivity analysis that excluded the outlier subjects with initial blood sugar levels > 600 or <50 mg/dl. The study results remained unchanged (for initial blood glucose levels ⩽200, 201–400, and >400 mg/dl, the hospital mortality rates were 48.2%, 41.2%, and 48.1%, respectively, p = 0.136).

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that the outcome of type 2 diabetic sepsis patients was mainly determined by the cumulative diabetic complication burden (represented by the aDCSI score) rather than diabetes itself. The above argument was reinforced by the reverse ORs found in the type 2 diabetic sepsis patients with an aDCSI score ⩽ 1. In other words, if type 2 diabetic patients have few complications, they may not have an inferior hospital outcome of sepsis compared with nondiabetic patients. Furthermore, somewhat surprisingly, neither recent glucose control (HbA1c) nor the initial blood glucose level was associated with hospital mortality during the sepsis course. In conclusion, clinicians should not infer the outcome of a type 2 diabetic sepsis patient merely on the basis of recent glucose control or initial glucose level; rather, they should consider the cumulative diabetic complication burden. The stereotype of the impact of type 2 diabetes in sepsis should be modified.

This study contributes at least two important novelties in clinical practice. First, we described the trajectory of type 2 diabetic sepsis patients from the past (cumulative diabetic complication burdens) to the recent past (blood glucose control within the prior 3 months, HbA1c) and the present (initial blood glucose at admission). The connections were bridged by using the nationwide diabetic patient database and the multicenter hospital databases concurrently. Second, we evaluated the severity of type 2 diabetic patients by using the aDCSI score, which is specific for the evaluation of diabetic complication burdens, and we explored its use in sepsis outcome predictions.

Donnelly and colleagues demonstrated that diabetes was associated with an increased risk of hospitalization due to infectious diseases. However, diabetes itself and insulin use were not associated with increased 28-day hospital mortality.32 Nonetheless, Dianna and coworkers demonstrated that patients with diabetes had an excess risk of dying from a range of infectious diseases.33 Both studies used a large cohort, but their conclusions were conflicting. We infer that the difference was due to the lack of a classification of diabetes severity. In our study, we introduced the use of the aDCSI score, and the results showed that the sepsis outcomes of diabetic patients were mainly determined by the complication burden of diabetes. Our argument was also supported by the dose–response effect in the trend test for the ORs of patients with different aDCSI scores. Therefore, judging the sepsis outcome only by the existence of diabetes is not sufficient.

HbA1c is a widely used marker that reflects the average glucose level within the previous 120 days. Furthermore, HbA1c was reported a major outcome predictor in diabetic sepsis patients.21 However, our study results did not support this argument. Many studies support the influence of long-term glycemic control on diabetic complication development.34,35 Poor long-term glycemic control makes diabetic patients prone to infectious diseases because of their impaired immune functions.32 In this study, HbA1c levels were assessed during a 1-month period prior to the admission day. In Taiwan, because of the convenience and high quality of medical care, the diabetes specialists were easily accessed without the need of long waiting. Patients could receive antidiabetic drug adjustment according to the HbA1c level in the outpatient department on time. Furthermore, the diabetic sepsis patients presenting with higher HbA1c levels may receive more aggressive blood sugar control with insulin in the initial stage of sepsis. Although, the hospital outcome of diabetic sepsis patients with higher HbA1c was not be as poor as initially thought, more evidence was needed to document this result.

Hyperglycemia frequently occurs in sepsis patients as a stress response that stimulates gluconeogenesis, which uses recycled pyruvate and lactate.36–38 Hyperglycemia may have protective effects in patients because high blood glucose levels increase the diffusion gradient in tissues with abnormal microvasculature caused by sepsis. Our study may indirectly support the above argument. A study by van Vught and colleagues demonstrated that admission hyperglycemia was associated with adverse outcomes in sepsis, irrespective of the presence of diabetes.39 However, our study demonstrated that a high blood glucose level at admission was not associated with hospital outcome. We inferred that the initial blood glucose level was an important risk factor for mortality in nondiabetic sepsis patients but not in type 2 diabetic sepsis patients.

Our study has the following strengths. In the study of the nationwide database, we used claims data for procedures such as mechanical ventilation, hemodialysis, and blood transfusion. The accuracy of this approach is far superior to using only ICD-9 or 10 codes for acute organ dysfunction. Furthermore, detailed information, such as blood culture results and APACH II scores, in the hospital-based database provided a richer understanding of the complex interplay between type 2 diabetes and sepsis, rather than simple taxonomy.

This study is not without limitations. We were able to link the individual patient’s medical information between the hospital-based database and the nationwide diabetic patient database to create a convincing longitudinal cohort study. However, due to the increasing conflict surrounding healthcare database use in Taiwan, we abandoned this idea to avoid further severe debates. Second, some may challenge our use of a previous sepsis definition, originating from the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria, rather than the sepsis-3 definition. However, we believe that the central idea of this study would not change. We retrieved the study cohort by using ICD-9 codes not only for sepsis (038) but also for main infection origins, such as pneumonia or biliary tract infection. Therefore, we are confident that all the retrieved sepsis patients in our study were truly infected and did not have other conditions, such as pancreatitis, burn injury, or trauma, which would similarly induce SIRS reactions. Furthermore, as noted by Cortes-Puch I and coworkers, ‘Moreover, these previous definitions and the SIRS criteria have been widely adopted for use at the bedside and for hospital and statewide quality improvement initiatives worldwide. Numerous controlled trials have relied on them, and this scientific database should not be discarded until unequivocal evidence indicates that superior diagnostic criteria exist.’40 We believe that our study could still provide valuable information to clinicians. Finally, the first sodium–glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitor (Empagliflozin) was available in Taiwan since 2014. However, our nationwide database only included the data from 1999 to 2012. Therefore, we could not discuss the potential risk of serious urinary tract infections and genital infections in type 2 diabetic patients using SGLT2 inhibitors.

Conclusion

In type 2 diabetic sepsis patients, hospital mortality was mainly determined by the diabetes-related complication burden rather than the diabetes itself. Furthermore, initial blood glucose and HbA1c levels may not be as important as previously thought. Early intervention in type 2 diabetic patients could clearly improve the sepsis outcome, especially in the early stage of diabetes with few diabetic complications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Biostatistics Task Force of Taichung Veterans General Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan, Republic of China, for their assistance and advice regarding the statistical analyses. We also thank the Clinical Informatics Research and Development Center of Taichung Veterans General Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan, Republic of China, for their assistance with data retrieval from the electronic database and further classification. This manuscript has been released as a Preprint at ‘10.20944/preprints201807.0398.v1.’41

The authors’ individual contributions are as follows: conception and design: Ming-Shun Hsieh, Sung-Yuan Hu and Chorng-Kuang How. Data analysis and interpretation: Jin-Wei Lin, Ming-Shun Hsieh, Chen-June Seak and Vivian Chia-Rong Hsieh. Manuscript writing: Ming-Shun Hsieh. Final approval and critical revision: Pau-Chung Chen. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Availability of data and material: The data that support the findings of this study are available from NHIRD but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of NHIRD.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: this work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan (MOHW107-TDU-B-212-123004); China Medical University Hospital (DMR-107-192); Academia Sinica Stroke Biosignature Project (BM10701010021); MOST Clinical Trial Consortium for Stroke (MOST 106-2321-B-039-005); Tseng-Lien Lin Foundation, Taichung, Taiwan; and Katsuzo and Kiyo Aoshima Memorial Funds, Japan.

The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. No additional external funding was received for this study.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest in preparing this article. They confirm that they have read the journal’s position on issues involved with unethical publication and affirm that this study is consistent with those guidelines.

Ethics approval and consent to participate: This study was conducted by using the NHIRD in Taiwan. The NHIRD contains deidentified secondary data for research; our study was exempted from the requirement of informed consent from participants. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of China Medical University (CMUH104-REC2-115).

Novelty statements: This study contributes at least two important novelties in clinical practice. Here, we described the trajectory of type 2 diabetic sepsis patients from the past (cumulative diabetic complication burdens) to the recent past (blood glucose control within the previous 3 months, HbA1c) and the present (initial blood glucose at admission).

ORCID iD: Pau-Chung Chen  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6242-5974

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6242-5974

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Contributor Information

Ming-Shun Hsieh, Institute of Occupational Medicine and Industrial Hygiene, National University College of Public Health, Taipei; Department of Emergency Medicine, Taipei Veterans General Hospital, Taoyuan Branch, Taoyuan; Department of Emergency Medicine, Taipei Veterans General Hospital, Taipei; School of Medicine, National Yang-Ming University, Taipei.

Sung-Yuan Hu, Department of Emergency Medicine, Taichung Veterans General Hospital, Taichung.

Chorng-Kuang How, Department of Emergency Medicine, Taipei Veterans General Hospital, Taipei; School of Medicine, National Yang-Ming University, Taipei.

Chen-June Seak, Department of Emergency Medicine, Lin-Kou Medical Center, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taoyuan.

Vivian Chia-Rong Hsieh, Department of Health Services Administration, China Medical University, Taichung.

Jin-Wei Lin, Department of Emergency Medicine, Taipei Veterans General Hospital, Taoyuan Branch, Taoyuan; Department of Emergency Medicine, Taipei Veterans General Hospital, Taipei.

Pau-Chung Chen, Institute of Occupational Medicine and Industrial Hygiene, National University College of Public Health, No. 17, Xu-Zhou Road,100, Taipei.

References

- 1. Vincent JL, Marshall JC, Namendys-Silva SA, et al. Assessment of the worldwide burden of critical illness: the intensive care over nations (ICON) audit. Lancet Respir Med 2014; 2: 380–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fleischmann C, Scherag A, Adhikari NK, et al. Assessment of global incidence and mortality of hospital-treated sepsis. Current estimates and limitations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016; 193: 259–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (sepsis-3). JAMA 2016; 315: 801–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ou SM, Chu H, Chao PW, et al. Long-term mortality and major adverse cardiovascular events in sepsis survivors. A nationwide population-based study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016; 194: 209–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Iwashyna TJ, Netzer G, Langa KM, et al. Spurious inferences about long-term outcomes: the case of severe sepsis and geriatric conditions. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012; 185: 835–841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Donnelly JP, Nair S, Griffin R, et al. Association of diabetes and insulin therapy with risk of hospitalization for infection and 28-day mortality risk. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 64: 435–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Falguera M, Pifarre R, Martin A, et al. Etiology and outcome of community-acquired pneumonia in patients with diabetes mellitus. Chest 2005; 128: 3233–3239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shah BR, Hux JE. Quantifying the risk of infectious diseases for people with diabetes. Diabetes Care 2003; 26: 510–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Thomsen RW, Hundborg HH, Lervang HH, et al. Diabetes mellitus as a risk and prognostic factor for community-acquired bacteremia due to enterobacteria: a 10-year, population-based study among adults. Clin Infect Dis 2005; 40: 628–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Benfield T, Jensen JS, Nordestgaard BG. Influence of diabetes and hyperglycaemia on infectious disease hospitalisation and outcome. Diabetologia 2007; 50: 549–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kornum JB, Thomsen RW, Riis A, et al. Type 2 diabetes and pneumonia outcomes: a population-based cohort study. Diabetes Care 2007; 30: 2251–2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Thomsen RW, Hundborg HH, Lervang HH, et al. Risk of community-acquired pneumococcal bacteremia in patients with diabetes: a population-based case-control study. Diabetes Care 2004; 27: 1143–1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kaplan V, Angus DC, Griffin MF, et al. Hospitalized community-acquired pneumonia in the elderly: age- and sex-related patterns of care and outcome in the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002; 165: 766–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McAlister FA, Majumdar SR, Blitz S, et al. The relation between hyperglycemia and outcomes in 2,471 patients admitted to the hospital with community-acquired pneumonia. Diabetes Care 2005; 28: 810–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tsai CL, Lee CC, Ma MH, et al. Impact of diabetes on mortality among patients with community-acquired bacteremia. J Infect 2007; 55: 27–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vincent JL, Preiser JC, Sprung CL, et al. Insulin-treated diabetes is not associated with increased mortality in critically ill patients. Crit Care 2010; 14: R12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Esper AM, Moss M, Martin GS. The effect of diabetes mellitus on organ dysfunction with sepsis: an epidemiological study. Crit Care 2009; 13: R18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Moss M, Guidot DM, Steinberg KP, et al. Diabetic patients have a decreased incidence of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med 2000; 28: 2187–2192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Thomsen RW, Hundborg HH, Lervang HH, et al. Diabetes and outcome of community-acquired pneumococcal bacteremia: a 10-year population-based cohort study. Diabetes Care 2004; 27: 70–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Graham BB, Keniston A, Gajic O, et al. Diabetes mellitus does not adversely affect outcomes from a critical illness. Crit Care Med 2010; 38: 16–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gornik I, Gornik O, Gasparovic V. HbA1c is outcome predictor in diabetic patients with sepsis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2007; 77: 120–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schuetz P, Jones AE, Howell MD, et al. Diabetes is not associated with increased mortality in emergency department patients with sepsis. Ann Emerg Med 2011; 58: 438–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wiener RS, Wiener DC, Larson RJ. Benefits and risks of tight glucose control in critically ill adults: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2008; 300: 933–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yamada T, Shojima N, Noma H, et al. Glycemic control, mortality, and hypoglycemia in critically ill patients: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Intensive Care Med 2017; 43: 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chao PW, Shih CJ, Lee YJ, et al. Association of postdischarge rehabilitation with mortality in intensive care unit survivors of sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014; 190: 1003–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J, et al. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med 2001; 29: 1303–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lin CC, Lai MS, Syu CY, et al. Accuracy of diabetes diagnosis in health insurance claims data in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc 2005; 104: 157–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Young BA, Lin E, Von Korff M, et al. Diabetes complications severity index and risk of mortality, hospitalization, and healthcare utilization. Am J Manag Care 2008; 14: 15–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chang HY, Weiner JP, Richards TM, et al. Validating the adapted diabetes complications severity index in claims data. Am J Manag Care 2012; 18: 721–726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chen HL, Hsiao FY. Risk of hospitalization and healthcare cost associated with diabetes complication severity index in Taiwan’s national health insurance research database. J Diabetes Complications 2014; 28: 612–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cheng CL, Chien HC, Lee CH, et al. Validity of in-hospital mortality data among patients with acute myocardial infarction or stroke in national health insurance research database in Taiwan. Int J Cardiol 2015; 201: 96–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Donnelly JP, Nair S, Griffin R, et al. Diabetes and insulin therapy are associated with increased risk of hospitalization for infection but not mortality: a longitudinal cohort study. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Magliano DJ, Harding JL, Cohen K, et al. Excess risk of dying from infectious causes in those with type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2015; 38: 1274–1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nathan DM, Genuth S, Lachin J, et al. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 1993; 329: 977–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). Lancet 1998; 352: 837–853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Marik PE, Bellomo R. Stress hyperglycemia: an essential survival response! Crit Care 2013; 17: 305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dungan KM, Braithwaite SS, Preiser JC. Stress hyperglycaemia. Lancet 2009; 373: 1798–1807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Langouche L, Van den Berghe G. Glucose metabolism and insulin therapy. Crit Care Clin 2006; 22: 119–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Van Vught LA, Wiewel MA, Klein Klouwenberg PM, et al. Admission hyperglycemia in critically ill sepsis patients: association with outcome and host response. Crit Care Med 2016; 44: 1338–1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cortes-Puch I, Hartog CS. Opening the debate on the new sepsis definition change is not necessarily progress: revision of the sepsis definition should be based on new scientific insights. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016; 194: 16–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hsieh M, Hu S, How C, et al. Trajectory of type 2 diabetes in sepsis outcome: impacts of diabetic complication burdens, initial glucose level, and HbA1c: population-based cohort study combining with nationwide and hospital-based database. Preprints 2018; 2018070398. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.