NMDA receptors are implicated in various neurological diseases. XiangWei et al. identify seven GRIN2D variants associated with developmental and epileptic encephalopathy. They describe the clinical phenotypes and evaluate functional changes, including pharmacological properties, surface trafficking, and neurotoxicity, as well as the responses to FDA-approved NMDAR drugs for potential rescue pharmacology.

Keywords: glutamate receptor, NMDA receptor, GluN, channelopathy, functional genomics

Abstract

N-methyl d-aspartate receptors are ligand-gated ionotropic receptors mediating a slow, calcium-permeable component of excitatory synaptic transmission in the CNS. Variants in genes encoding NMDAR subunits have been associated with a spectrum of neurodevelopmental disorders. Here we report six novel GRIN2D variants and one previously-described disease-associated GRIN2D variant in two patients with developmental and epileptic encephalopathy. GRIN2D encodes for the GluN2D subunit protein; the GluN2D amino acids affected by the variants in this report are located in the pre-M1 helix, transmembrane domain M3, and the intracellular carboxyl terminal domain. Functional analysis in vitro reveals that all six variants decreased receptor surface expression, which may underline some shared clinical symptoms. In addition the GluN2D(Leu670Phe), (Ala675Thr) and (Ala678Asp) substitutions confer significantly enhanced agonist potency, and/or increased channel open probability, while the GluN2D(Ser573Phe), (Ser1271Phe) and (Arg1313Trp) substitutions result in a mild increase of agonist potency, reduced sensitivity to endogenous protons, and decreased channel open probability. The GluN2D(Ser573Phe), (Ala675Thr), and (Ala678Asp) substitutions significantly decrease current amplitude, consistent with reduced surface expression. The GluN2D(Leu670Phe) variant slows current response deactivation time course and increased charge transfer. GluN2D(Ala678Asp) transfection significantly decreased cell viability of rat cultured cortical neurons. In addition, we evaluated a set of FDA-approved NMDAR channel blockers to rescue functional changes of mutant receptors. This work suggests the complexity of the pathological mechanisms of GRIN2D-mediated developmental and epileptic encephalopathy, as well as the potential benefit of precision medicine.

Introduction

Developmental and epileptic encephalopathies (DEEs) are severe neurodevelopmental disorders that present early in infancy and childhood with intractable epilepsy, developmental delay/intellectual disability, attention deficit hyperactivity disease (ADHD), autism spectrum disorder (ASD), and other neurological and neuropsychiatric symptoms (Gardella et al., 2018; Helbig et al., 2018; Olson et al., 2018; Pons et al., 2018). The DEEs include a spectrum of electroclinical syndromes, such as Ohtahara syndrome, West syndrome, Dravet syndrome, and Lennox-Gastaut syndrome with diverse aetiologies (McTague et al., 2016; Brainstorm Consortium et al., 2018). An increasing number of patients with DEE diagnosed with a specific genetic aetiology reflects the improvement and increasing frequency with which next-generation sequencing (NGS) is applied to patients with epilepsy (Thevenon et al. 2016, Klein and Feroud, 2017; Wilfert et al. 2017; Dunn et al. 2018; Heyne et al., 2018; Wright et al. 2018). However, it can be difficult to conclude definitively whether a de novo variant contributes to disease pathogenesis, especially in the absence of any functional understanding of the effects of the variant.

N-methyl d-aspartate receptors (NMDARs) are ligand-gated ionotropic receptors mediating a slow calcium-permeable component of excitatory synaptic transmission in the CNS (Traynelis et al., 2010). The NMDARs are encoding by the GRIN gene family, which includes GRIN1, GRIN2A, GRIN2B, GRIN2C, GRIN2D, GRIN3A and GRIN3B. NMDARs are tetrameric assemblies of two GluN1 and two GluN2 subunits and play important roles in brain development, synaptic plasticity, learning, and memory. NMDARs also have been implicated in neurodevelopmental disorders (Traynelis et al., 2010; Paoletti et al., 2013). All GluN subunits have a similar structural arrangement for the amino terminal domain (ATD), agonist-binding domain (ABD; S1 and S2), transmembrane domain (M1, M2, M3, and M4), and C-terminal domain (CTD) (Traynelis et al., 2010). Previous studies suggested that three control elements—the pre-M1 helix, the M3 transmembrane helix (especially the SYTANLAAF motif), and the M4 transmembrane helix/pre-M4 region—play important roles in NMDAR channel gating. Moreover, pathogenic missense variants affecting these regions have been implicated in a set of neurodevelopmental conditions, including epilepsy and intellectual disability (Yuan et al., 2014, 2015; Chen et al., 2017; Ogden et al., 2017; Gibb et al., 2018).

Recent advances in NGS technology have increased the identification of disease-associated variants across many genes that are intolerant to variation according to population data (gnomAD database, gnomAD.broadinstitute.org). This includes over 250 missense variants in GRIN genes in patients with various neurological and neuropsychiatric disorders (Burnashev and Szepetowski, 2015; Yuan et al., 2015; Hu et al., 2016; XiangWei et al., 2018; Strehlow et al., 2019). However, only a minority (26%) of these variants have been examined at the functional level (XiangWei et al., 2018). The gap between the high volume of sequencing data and functional evaluation complicates further understanding of disease mechanisms, certainty of diagnosis, and choice of treatment. For GRIN2D/GluN2D, four reported missense variants have been reported in five individuals (Li et al., 2016; Tsuchida et al., 2018), with comprehensive functional evaluation for only one variant associated with epilepsy and intellectual disability that can be classified as pathogenic according to ACMG criteria (Li et al., 2016). In this study, we report seven missense variants in GRIN2D (NM_000836), including six novel variants and one previously reported disease-associated variant at a recurrent site, which were identified by NGS in paediatric patients with DEE. We describe the clinical phenotypes of the patient cohort and present the associated functional changes for a subset of the variants, including their pharmacological properties, cell surface trafficking, ability to induce neurotoxicity, and response to a set of FDA-approved NMDAR channel blockers for potential rescue pharmacology.

Materials and methods

Consent and study approval

Written informed consents were obtained from the parents of all patients reported. This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee and the Institutional Review Boards of Peking University First Hospital, Boston Children’s Hospital, Hospices Civils de Lyon, University Hospital of Lille, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Danish Epilepsy Centre, Antwerp University Hospital, University of Leipzig Hospitals and Clinics and Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg. All in vitro studies were conducted according to the guidelines of Emory University and the University of Pittsburgh.

Patient phenotype and genetic analysis

We retrospectively analysed patient data regarding seizure onset, seizure types, EEG and MRI findings, and response to clinical treatment attempts with conventional anti-epileptic drugs and memantine. Proband 1 (Ser573Phe) and Proband 6 (Ala678Asp) were identified from a cohort of 1969 patients with both epilepsy and intellectual disability who were sequenced using a gene panel targeting 480 epilepsy-related genes that included GRIN2D. This panel used the Agilent SureSelect Target Enrichment technique, containing a total of 11 417 probes covering 1.285 Mbp. Targeted NGS was subsequently performed on an Illumina GAIIx platform using paired-end sequencing of 110 bp to screen for variants. Image analysis and base calling were performed by RTA software (real-time analysis, Illumina) and CASAVA software v1.8.2 (Illumina). After marking duplicate reads and filtering out reads of low base quality score using the Genome Analysis Tool kit (GATK), clean paired-end reads were aligned to GRCh37/hg19 using BWA software (Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). In addition to insertion-deletions (indels) and single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) identified using the GATK, variants were annotated using ANNOVAR. We performed validation and parental origin analyses for the mutation by conventional Sanger sequencing (Kong et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2015; Gao et al., 2017; Hernandez et al., 2017a, b). Proband 6 (Ala678Asp) was evaluated by both Peking University First Hospital and Boston Children’s Hospital. The GRIN2D variants in Probands 1 and 6 are the only de novo variants that were considered as the most likely responsible variants to the phenotypes. Proband 2 (Val667Ile) and Proband 4 (Leu670Phe) were registered and evaluated in University of Leipzig Hospitals and Clinics and Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg, respectively, by whole-exome sequencing with trio. Proband 3 (Leu670Phe), Proband 5 (Ala675Thr), and Proband 8 (Arg1313Trp) were registered and evaluated by a gene panel in the Hospices Civils de Lyon, University Hospital of Lille, and Danish Epilepsy Centre, respectively. Proband 7 (Ser1271Leu) was evaluated at the Antwerp University Hospital by whole-exome sequencing. All genomic DNA used in the experiments were extracted from peripheral leucocytes. All the variants were validated by Sanger sequencing. Assessment of pathogenicity of these seven variants was performed following ACMG guidelines (Richards et al., 2015) before functional studies were undertaken.

Molecular biology

Mutagenesis was performed on cDNA encoding human GRIN genes (Chen et al., 2017) using the QuikChange protocol with Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene) to replicate the parental DNA strand with the desired mismatch incorporated into the primer. Methylated parental DNA was digested with DpnI for 3 h at 37°C and the nicked mutant DNA was transformed into TOP10 Competent Cells (Life Technologies). Bacteria were spun down and prepared using the Qiagen QIAprep® Spin Miniprep kit. Sequences were verified through the mutated region using dideoxy DNA sequencing (Eurofins MWG Operon). The plasmid vector for wild-type human GluN1-1a (hereafter GluN1; GenBank accession codes: NP_015566) and human GluN2D (GenBank accession codes: NP_000827) was pCI-neo (Hedegaard et al., 2012).

The cDNA was linearized using FastDigest (Thermo Fisher Scientific) restriction digestion at 37°C for 1 h. Complementary RNA (cRNA) was synthesized in vitro from linearized cDNA for wild-type and mutants using the mMessage mMachine T7 kit (Ambion). Xenopus laevis stage VI oocytes were prepared from commercially available ovaries (Xenopus 1 Inc.). The ovary was digested with Collagenase Type 4 (Worthington-Biochem) solution (850 μg/ml, 15 ml for a half ovary) in Ca2+-free Barth’s solution, which contained (in mM) 88 NaCl, 2.4 NaHCO3, 1 KCl, 0.33 Ca(NO3)2, 0.41 CaCl2, 0.82 MgSO4, 10 HEPES (pH 7.4 with NaOH) supplemented with 100 μg/ml gentamycin, 40 μg/ml streptomycin). The ovary was incubated in enzyme with gentle mixing at room temperature (23°C) for 2 h. The oocytes were rinsed five times with Ca2+-free Barth’s solution (35–40 ml of fresh solution each time) for 10 min each time, and rinsed further four times with normal Barth’s solution (35–40 ml of fresh solution) on the mixer for 10 min each time. The sorted oocytes were kept in 16°C incubator for further use. X. laevis oocytes were injected with a 1:2 ratio of GluN1:GluN2D cRNA that by weight was 5–10 ng in 50 nl of RNAase-free water per oocyte (Chen et al., 2017). Injected oocytes were maintained in normal Barth’s solution at 15–19°C.

Two-electrode voltage clamp current recordings

Two-electrode voltage clamp (TEVC) current recordings were performed 2–3 days post-injection at room temperature (23°C) as described previously (Yuan et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2017). The extracellular recording solution contained (in mM) 90 NaCl, 1 KCl, 10 HEPES, 0.5 BaCl2, and 0.01 EDTA (pH7.4 with NaOH). Solution exchange was computer controlled through an 8-valve positioner (Digital MVP Valve). Oocytes were placed in a dual track chamber that shared a single perfusion line, allowing simultaneous recording from two oocytes. All concentration-response solutions were made in the extracellular recording solution. Voltage control and data acquisition were achieved by a TEVC amplifier (OC725C, Warner Instruments). The voltage electrode was filled with 0.3 M KCl and the current electrode with 3 M KCl. Oocytes were held under voltage clamp at holding potential −40 mV unless otherwise indicated. MTSEA (2-aminoethyl methanethiol sulfonate hydrobromide; Toronto Research Chemicals) solution was prepared fresh and used within 30 min. All chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich unless otherwise stated.

Whole-cell voltage-clamp current recordings

Human embryonic kidney (HEK293) cells (ATCC CRL-1573) were plated on glass coverslips pretreated with 0.1 mg/ml poly-d-lysine and cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium/GlutaMax™ medium (GIBCO, 15140–122) supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum and 10 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin at 37°C and 5% CO2. The HEK cells were transiently transfected with plasmid cDNAs encoding wild-type or mutant GluN2D receptors along with GluN1 and GFP at a cDNA ratio of 1:1:1 (0.2 μg/μl, 2.5 μl per well) by using the calcium phosphate precipitation method (Chen et al., 2017). After 18–24 h following the transfection, the cells were perfused with external recording solution that contained 3 mM KCl, 150 mM NaCl, 0.01 mM EDTA, 1.0 mM CaCl2, 10 mM HEPES, and 2.0 mM d-mannitol, with the pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH. The whole-cell voltage-clamp current recordings were performed with recording electrodes (resistance: 3–4 MΩ thin-walled filamented borosilicate glass pipettes #TW150F-4, World Precision Instruments) filled with the internal pipette solution that contained 110 mM d-gluconic acid, 110 mM CsOH, 30 mM CsCl, 5 mM HEPES, 4 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM CaCl2, 2 mM MgCl2, 5 mM BAPTA, 2 mM Na2ATP, 0.3 mM Na2GTP (pH was adjusted to 7.35 with CsOH; the osmolality was adjusted to ∼305 mOsmol/kg). The whole cell current responses evoked by maximally-effectively concentrations of agonists (10 μM glutamate and 10 μM glycine) at −60 mV of holding potential were obtained by Axopatch 200B patch-clamp amplifier (Molecular Devices). The current responses were anti-alias filtered with −3 dB, 8-pole Bessel filter at 8 kHz (Frequency Devices) and digitized at 20 kHz using Digidata 1440A acquisition system (Molecular Devices) controlled by Clampex 10.3 (Molecular Devices).

Beta-lactamase assay

HEK293 cells (CRL 1573, ATCC) were plated in 96-well plates (∼50 000 cells/well) and transiently transfected with cDNA encoding β-lac-GluN1 and wild-type or mutant GluN2D using FuGENE6® (Promega) (Swanger et al., 2016). Cells treated with FuGENE6® alone were used to define background absorbance. NMDAR antagonists (200 μM APV and 200 μM 7-CKA) were added at the time of transfection. Six wells were transfected for each condition; surface and total protein levels were measured in three wells each. After 24 h, cells were rinsed with Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS, in mM, 140 NaCl, 5 KCl, 0.3 Na2HPO4, 0.4 KH2PO4, 6 glucose, 4 NaHCO3) supplemented with 10 mM HEPES, and then 100 μl of a 100 μM nitrocefin (Millipore) solution in HBSS with HEPES was added to each well for measuring the level of extracellular enzymatic activity, which reflected NMDAR surface expression. To determine the level of total enzymatic activity, the cells were lysed by a 30-min incubation in 50 μl H2O prior to the addition of 50 μl of 200 μM nitrocefin. The absorbance at 468 nm was read using a microplate reader every min for 30 min at 30°. The rate of increase in absorbance was generated from the slope of a linear fit to the data.

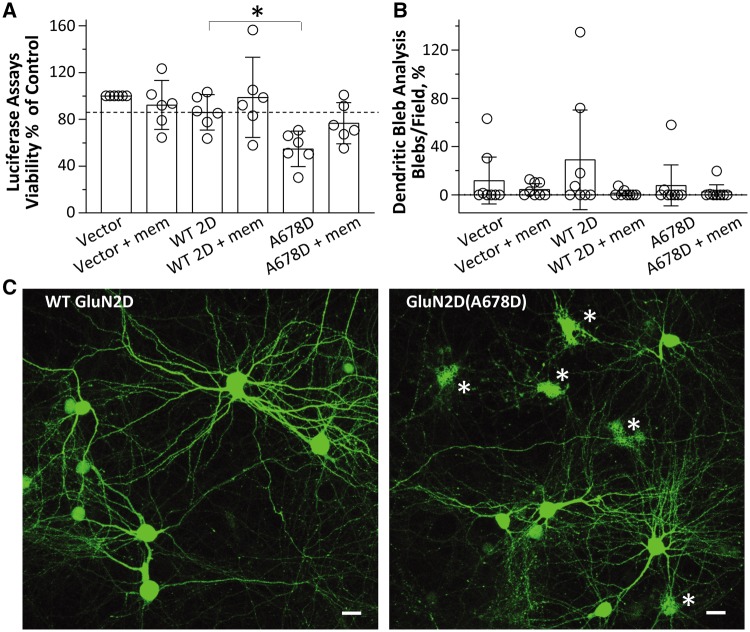

Neuronal excitotoxicity and dendritic swelling/bleb analysis

All procedures involving the use of animals were reviewed and approved by the University of Pittsburgh IACUC. Mixed neuronal/glial cortical cultures were prepared from embryonic Days 17–18 Sprague Dawley rats and maintained as described previously (Aras et al., 2008). For in vitro excitotoxicity studies, primary cortical neurons on 35 mm glass coverslips were transfected at in vitro Days 19–20 in sterile 24-well plates by adding 100 μl per well of transfection mixture (1.5 μg cDNA/well, 2 μl Lipofectamine™ 2000/well, 100 μl Opti-MEM™/well) to coverslips in 0.5 ml of Dulbecco’s modified minimum essential medium, with 2% calf serum (bringing the total volume to 600 μl) (Aras et al., 2008). The vector-expressing control group was transfected with 0.375 μg pUHC13–3 (luciferase-expressing vector) and 1.125 μg of pCI-neo (empty vector). GluN2D variant-expressing groups were transfected with 0.375 μg pUHC13–3 luciferase, 0.3 μg of either wild-type human GluN2D or mutant GluN2D(Ala678Asp), and 0.825 μg pCI-neo. Note that pCI-neo was used to maintain the total amount of plasmid concentration constant among experiments (1.5 μg). Paired sets of the transfected cultures were co-treated with 50 μM memantine until analysis. Measurements of luciferase luminescence, as an index of cell viability, were performed using a commercially available kit (Steadylite, Perkin Elmer) (Aras et al., 2008) 24 h following transfection. Luciferase assay results represent six independent experiments performed on different days per variant (n = 6); for each experiment, measurements were performed in quadruplicate.

Confocal imaging studies to analyse dendritic swelling were performed in four independent experiments on different neuronal culture dates 24 h after transfection. Neurons used for confocal bleb analysis were transfected in three combinations, either: (i) 0.9 μg/well GFP and 0.6 μg pCI-neo (vector), as a vector-expressing control group; (ii) 0.9 μg/well GFP, 0.3 μg of wild-type human GluN2D with 0.3 μg pCI-neo (vector); or (iii) 0.9 μg/well GFP, 0.3 μg of mutant GluN2D(Ala678Asp) with 0.3 μg pCI-neo (vector). An identical set of transfected neurons from each treatment group was also co-incubated with 50 μM memantine for 24 h. Thus, six experimental conditions were analysed.

Image fields were acquired at ×20 magnification with a Nikon A1+ confocal microscope (Aras et al., 2008). For each culture date (n = 4), eight image fields were acquired across two coverslips from each of the six experimental conditions. Each set of four images was subjected to whole-field dendritic bleb analysis (described below), and the measured number of ‘dendritic swellings/image field’ was averaged to obtain a mean value for each coverslip. Summary data in Fig. 5 represents this mean dendritic swellings/field value for all coverslips analysed over four experiments.

Figure 5.

The GluN2D-A678D variant induces neurotoxicity. Transfection of GluN2D(Ala678Asp) into cultured cortical neurons reduces cell viability, which can be prevented by the low affinity NMDAR antagonist memantine. (A) The mean cell viability determined by a Luciferase assay is shown as a per cent of control group (Vector) (% control) with wild-type GluN2D (–), 83%; wild-type GluN2D, 86%; GluN2D-A678D, 55%; GluN2D-A678D + mem, 77%. mem = 50 μM memantine; *P < 0.05; one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test (bar graph is mean ± 95% CI). (B) Dendritic bleb analysis indicated no significant changes between wild-type and GluN2D-A678D. (C) Confocal images display morphological features of cultured rat cortical neurons transfected with GFP-N1 and either wild-type GluN2D (left) and GluN2D-A678D (right), respectively. Note the presence of cellular debris in the mutant-transfected cells (asterisk), indicative of toxicity and as quantified in A. Scale bars = 20 μm. Experiments were repeated in four independent culture dates.

To quantify the number of dendritic blebs within each image field, intensity-thresholding object count parameters within NIS-Elements Advanced Research analysis software was customized to auto-detect well-defined areas of GFP fluorescence with the following characteristics: mean intensity, 400–4095 AFU; area, 0–30 μm2, circularity, 0.5–1.0; smooth, 1×; clean, 3×, separate 1×. In each experiment, these parameters were applied to the aforementioned four random image fields per coverslip and these four values were then averaged to obtain a mean measurement of dendritic blebs/field for each coverslip. Further, GFP-expressing background cellular debris may artificially inflate this automated measurement in vector-expressing neurons (which should exhibit minimal bleb formation). To account for this, the final empirical mean dendritic blebs/field values for pCI-neo (−memantine) and pCI-neo (+memantine) were used as background subtraction standards for each of the vehicle and memantine-treated groups, respectively [i.e. pCI-neo, wild-type-GluN2D and GluN2D(Ala678Asp)-expressing groups had their mean dendritic blebs/field count for each coverslip adjusted for cellular debris, according to which drug they were treated with]. Similar toxicity analyses were described earlier using other NMDAR mutants (Li et al., 2016; Ogden et al., 2017).

Evaluation of FDA-approved NMDAR antagonists

FDA-approved drugs that act as NMDAR open channel blockers (e.g. memantine, dextromethorphan, dextrorphan, and ketamine) were evaluated using TEVC recordings from Xenopus oocytes co-expressing GluN1 with the wild-type or mutant GluN2D. The composite concentration-response curves were recorded at a holding potential of −40 mV and fitted with Equation 2 to determine the IC50 values (see below).

Data and statistics analysis

Statistical analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism 5 (La Jolla, CA, USA) and OriginPro 9.0 (Northampton, MA, USA). Statistical significance was assessed using one-way ANOVA with post hoc Dunnett’s multiple comparison test, with P < 0.05 considered significant. Power was determined using GPower (3.1.9.2). Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Error bars represent SEM unless otherwise stated. The concentration-response relationship for agonists were fitted by:

| (1) |

The concentration-response relationship for inhibition by FDA-approved channel blockers was fitted by:

| (2) |

where N is the Hill slope, EC50 is the concentration of the agonist that produces a half-maximal effect, IC50 is the concentration of the antagonist that produces a half-maximal effect, and minimum is the degree of residual inhibition at a saturating concentration of the antagonist. The channel open probability (POPEN) was estimated from the fold Potentiation observed in MTSEA using the following equation (Yuan et al., 2005):

| (3) |

where γMTSEA and γCONTROL were the single channel chord conductance values estimated from GluN1/GluN2A receptors and fold Potentiation was defined as the ratio of current in the presence of MTSEA to current in the absence of MTSEA (Yuan et al., 2005).

The glutamate deactivation time course was fitted by a non-linear least squares algorithm (ChanneLab, Synaptosoft, Decatur, USA) with a two-component exponential function by:

| (4) |

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary material. Raw data and derived data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Results

Clinical phenotypes associated with GRIN2D variants

All eight patients had DEE in the absence of significant family history or perinatal history. Age at ascertainment was 9 months to 34 years; there were four female and four male patients in our cohort. Family history was negative for epilepsy or developmental delay/intellectual disability for all cases. Perinatal history was negative unless otherwise noted as unknown or remarkable. For all patients for whom epilepsy details were available, most had seizures presented within the first year of life (range <1 month to 3 years, 5 months), five with infantile spasms. Some patients developed other seizure types over time. All patients had developmental delay/intellectual disability, and some had hypotonia and movement disorders. Table 1 provides additional detail regarding these features and EEG and MRI data as available.

Table 1.

Clinical features and genetic characteristic of eight patients with GRIN2D variants

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | Patient 6 | Patient 7 | Patient 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | Male | Male | Female | N/A | Female | Male | Female |

| Age | 4 y, 5 mo | 2 y, 2 mo | 9 y, 8 mo | 9 mo | Dead before 2 y | 7 y, 3 mo | 3 y | 34 y |

| Diagnosis | Epilepsy + DD | EOEE | Epilepsy + ID | EOEE | Epilepsy + ID | Epilepsy + ID | Epilepsy + DD | Epilepsy + ID |

| GRIN2D variants (NM_000836) | c.1718C>T: p.(Ser573Phe) | c.1999G>A: p.(Val667Ile) | c.2008C>T: p.(Leu670Phe) | c.2008C>T: p.(Leu670Phe) | c.2023G>A: p.(Ala675Thr) | c.2033C>A: p.(Ala678Asp) | c.3812C>T: p.(Ser1271Leu) | c.3937C>T: p.(Arg1313Trp) |

| ACMG Classification | Pathogenic | Pathogenic | Pathogenic | Pathogenic | Likely pathogenic | Pathogenic | Likely pathogenic | Uncertain significance |

| Family history | Unremarkable | Maternal uncle has ADHD | Unremarkable | Unremarkable | N/A | Unremarkable | Unremarkable | Unremarkable |

| Perinatal period | Normal | Normal | Normal | Prolonged delivery | N/A | Foetal bradycardia during delivery | Prolonged delivery and foetal distress | N/A |

| Age at onset | 2 mo | 9 mo | <1 y | 4 mo | N/A | 3 y, 5 mo | 2 mo | <1 y |

| Seizure types | Focal motor → GTCS | Atypical absence | Epileptic spasms | Focal motor → GTCS | Epileptic spasms | Focal motor → GTCS | Epileptic spasms (2 mo), myoclonic jerks (3 y 5 mo) | GTCS, focal clonic, myoclonic, epileptic spasms |

| (V)EEG | Slow background, multifocal spikes | Bilateral central spikes (9 mo); hypsarrhythmia (1 y 9 mo) | Diffuse paroxysmal abnormalities (<1 y) | Continuous hypsarrhythmia with bilateral synchrony | N/A | Frequent multifocal spikes (3 y 11 mo); runs of faster alpha activity, multifocal spikes (6 y) | Modified hypsarrhythmia (5 mo); sporadic focal epileptic activity, runs of faster beta activity (3 y) | Frequent/almost continuous sharp-waves with high amplitude |

| Response to AEDs | No formal therapy | seizure free on memantine, IVIG, oral steroids and Mg | no response | Mild amelioration of EEG on steroids – no clinical overt seizures | No response | seizure free on VPA, LEV, and clonazepam | relative controlled by VPA, TPM and ELF (in combination with VNS) | No response |

| Developmental delay | Walked at 2 y | Severe | Severe | Severe | Yes | Walked at 2 y; single words at 2.5 y | Severe | Severe |

| Hypotonia and movement disorder | No | Mild hypotonia, dyskinetic and choreiform movements | Severe hypotonia | Hypotonia, dyskinetic and choreiform movements | Hypotonia | Hypotonia | Severe axial hypotonia, continuous movements | Severe hypotonia, tetraplegia |

| MRI | Normal | Mild cerebral atrophy | Cortical atrophy | Mild cerebral atrophy | N/A | Normal | Normal | Mild cerebral atrophy |

| Blood/urinary metabolic | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | N/A | Normal | Normal | Normal |

| Other neurological features | Poor eye contact, autistic behaviours | Cerebral visual impairment, oculomotor apraxia, changing tone, periodic breathing pattern | Cerebral visual impairment, feeding difficulties | Visual impairment with inconstant fixation, | N/A | Poor eye contact, autistic behaviours | Cerebral visual impairment, pyramidal signs with abnormal plantars (2 y), failure to thrive | Wheelchair user, scoliosis, cerebral visual impairment, amaurosis, feeding difficulties |

AED = anti-epileptic drug; DD = developmental delay; ELF = ethylloflazepate; EOEE = early-onset epileptic encephalopathy; GTCS = generalized tonic clonic seizures; LEV = levetiracetam; mo = months; NA = not available; TPM = topiramate; VGB = vigabatrin; VNS = vagal nerve stimulator; VPA = valproate; y = years.

Proband 1 (Ser573Phe) is a female aged 4 years and 5 months with unremarkable family history and normal perinatal period. Her first seizure onset at 2 months of age and she now has one to two seizures per week without formal therapy. EEG showed slow background and spikes in bilateral occipital and post-temporal region. Brain MRI was normal. She has developmental delay, sat at 11 months old and walked independently at 2 years of age. She has autistic behaviours and less eye contact with others (Table 1).

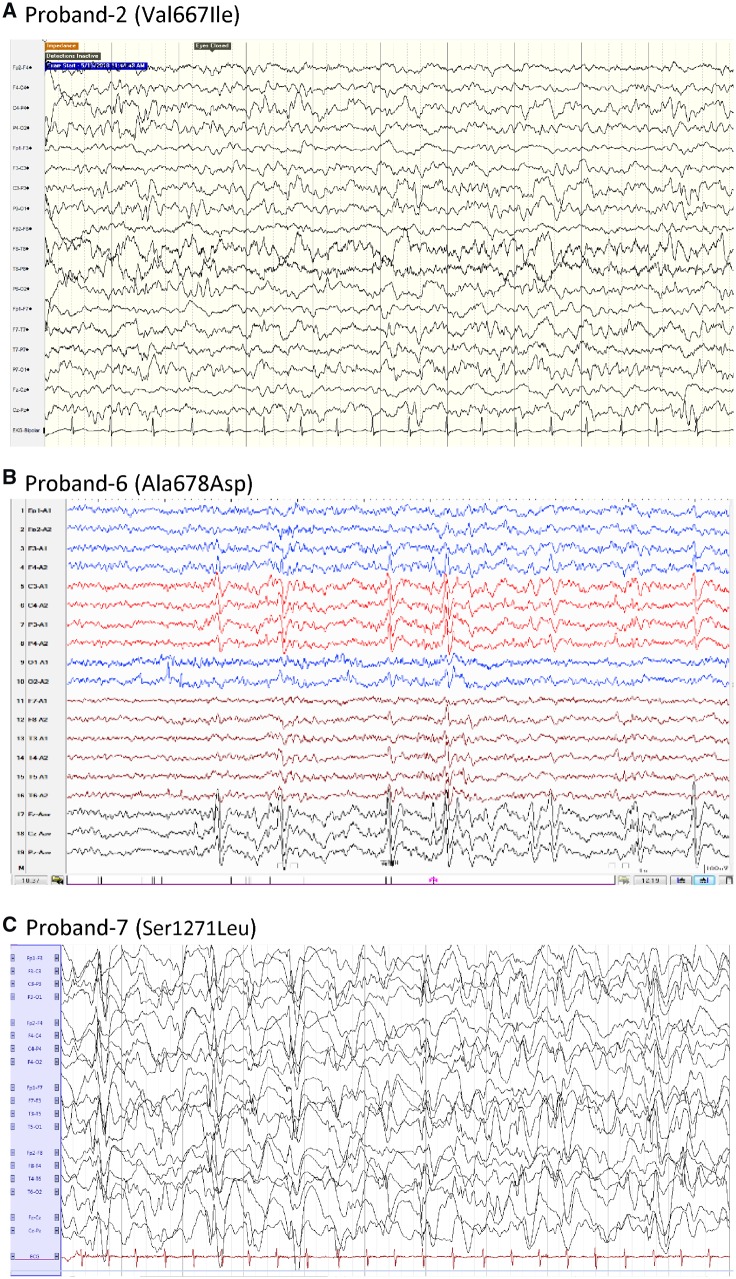

Proband 2 (Val667Ile) is a male aged 2 years and 2 months diagnosed with early onset epileptic encephalopathy (EOEE) with unclear perinatal history. His first seizure was at 9 months and was described as atypical absence (eye rolling or eyelid fluttering). EEG showed bilateral central spikes after the first seizure; the EEG pattern evolved to hypsarrhythmia at 21 months (Fig. 1A). Daily electrographic seizures were recorded on video-electroencephalogram (VEEG) at 18 months. Brain MRI was normal. His seizures were intractable to treatment with valproate and vigabatrin but responded completely to a combination of memantine, IVIg (intravenous immunoglobulin), oral steroids, and magnesium. He had severe global developmental delay and intellectual disability, hypotonia, movement disorder (mild dyskinesia and choreiform movements), and oculomotor apraxia (Table 1).

Figure 1.

EEG features of patients with GRIN2D variants. (A) Proband 2 (Val667Ile) shows multiple spike predominately in bilateral post-lobe (1 year 5 months of age). (B) Proband 6 (Ala678Asp) shows spike and spike-wave in bilateral Rolandic region and mid-line during awake periods (3 years 11 months of age). (C) Proband 7 (Ser1271Leu) shows hypsarrhythmia (3 years).

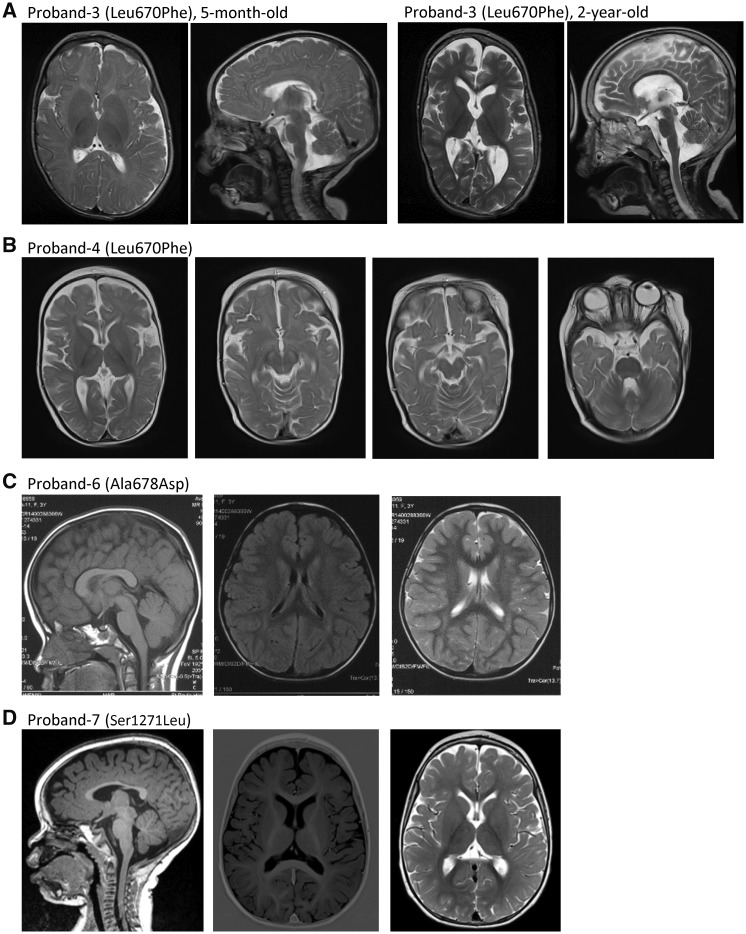

Proband 3 (Leu670Phe) is a male aged 9 years and 8 months with a history of infantile spasms. EEG showed diffuse paroxysmal abnormalities and cortical atrophy on MRI at the time of presentation (Fig. 2A). Seizures were refractory to conventional anti-epileptic drugs. The patient had severe intellectual disability, severe hypotonia, and cortical visual impairment (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Brain MRI of patients with GRIN2D variants. (A) Proband 3 (Leu670Phe) showed cortical atrophy, global loss of white matter volume and enlargement of the lateral ventricles; compare MRI at 5 months old (left two panels) to 2 years old (right two panels). (B) Proband 4 (Leu670Phe) showed mild cortical atrophy. (C) Proband 6 (Ala678Asp) had normal MRI left: sagittal T1. middle: coronal T2. right: coronal T2 at 3 years 5 months of age. (D) Proband 7 (Ser1271Leu) had normal MRI left: sagittal T1, middle: coronal T1, right: coronal T2 at 14 months old.

Proband 4 (Leu670Phe) is a 9-month-old female diagnosed with EOEE at 4 months with prolonged delivery but unremarkable family history. Her seizure changed from left-sided seizure to bilateral tonic-clonic seizure with suspicion of previous temporary infantile spasms at 2 months of age. EEG showed continuous hypsarrhythmia with bilateral synchrony and brain MRI showed mild cerebral atrophy (Fig. 2B). This patient has severe global developmental delay with intermittent smiling and fixation, hypotonia, dyskinetic and choreiform movements and visual impairment. She was refractory to anti-epileptic drugs, but her EEG can be mild ameliorated when using steroids.

Proband 5 (Ala675Thr) is a patient who presented with refractory infantile spasms, severe global developmental delay, and hypotonia. He died before the age of 2 years (Table 1).

Proband 6 (Ala678Asp) is a 7-year-old female with severe developmental delay noted by her parents at the age of 1 year. She was reported to have perinatal (foetal) bradycardia transiently, but the Apgar score was reportedly normal after birth. She had a focal seizure at age 3 years 5 months and then developed generalized tonic-clonic seizures. Her seizures were controlled on valproate, levetiracetam, and clonazepam for 2 years (last seizure onset at age 4 years 7 months). The patient had slow developmental progress after seizure onset. She walked independently at age 2 years 2 months and cannot climb stairs. She remains nonverbal, has autistic stereotypies, and no eye contact with others. Her EEG showed spike-wave complexes in the bilateral Rolandic regions and midline during the awake and asleep states (Fig. 1B). MRI was normal both before and after seizure onset (Fig. 2C). Routine karyotyping, blood and urinary metabolic screens, MLPA (P036), array-CGH, evaluation of mitochondrial genes, mitochondrial respiratory chain complex I-IV, and ATPase-FoF1 enzyme activity assay, were all negative (Table 1).

Proband 7 (Ser1271Leu) is a 3-year-old male with a history of refractory infantile spasms with onset at 2 months. He developed myoclonic jerks at age 3 years 5 months. EEG showed modified hypsarrhythmia at seizure onset and evolved to reveal sporadic multifocal epileptiform activity at the age of 3 years (Fig. 1C). Brain MRI was normal at both 5 months and 14 months (Fig. 2D). This patient also has a severe developmental delay, profound intellectual disability, hypotonia, and dyskinesia. He was refractory to a series of anti-epileptic drugs, but seizures were partially controlled by valproate, topiramate, ethylloflazepate (a benzodiazepine derivate) and vagal nerve stimulator (Table 1).

Proband 8 (Arg1313Trp) is a 34-year-old female with onset of epilepsy by 1 year of age. Seizures consisted of epileptic spasms and generalized tonic-clonic, focal clonic, myoclonic seizures and were refractory to anti-epileptic drugs. EEG at seizure onset showed high-amplitude paroxysmal activity and sharp waves in the biparietal, midline, and right temporoparietal regions. MRI showed microcephaly, small frontal lobes, thin corpus callosum, and moderate cerebellar atrophy. The patient has severe intellectual disability, hypotonia, and cortical visual impairment (Table 1).

Three patients have the same recurrent GluN2D Val667Ile substitution with a diagnosis of EOEE. The age of seizure onset for all three cases was in infancy (2 months to 9 months); all three had global developmental delay and hypotonia. Based on previous in vitro rescue pharmacology evaluation of GluN2D Val667Ile, memantine was administered to Patient 1 in Li et al. (2016), after which the patient showed subjective developmental gains but no seizure improvement. Later the patient’s seizures worsened and developed to refractory status epilepticus, which was controlled with EEG improvement by combination therapy with ketamine and magnesium sulphate. Patient 2 in Li et al. (2016) responded to memantine treatment with seizure control and developmental improvement. She is now 6.5 years old and has profound developmental delay (no speech, no walking) and acquired microcephaly. At 3.5 years old, she had refractory epilepsy with five to seven mostly tonic seizures per day (∼1 min each) despite treatment with memantine (up to 0.5 mg/kg/day) and sultiame (up to 10 mg/kg/day). By 5.5 years of age, she had been seizure-free for >1 year while treated with memantine as above as well as lamotrigine and valproic acid. During this year of seizure freedom, parents also noted an improved sleep pattern and mild developmental progress, including improved alertness and interaction. In addition, the EEG markedly improved. The new patient with the same variant in our study had complete seizure freedom during treatment with memantine, IVIg, oral steroids and magnesium.

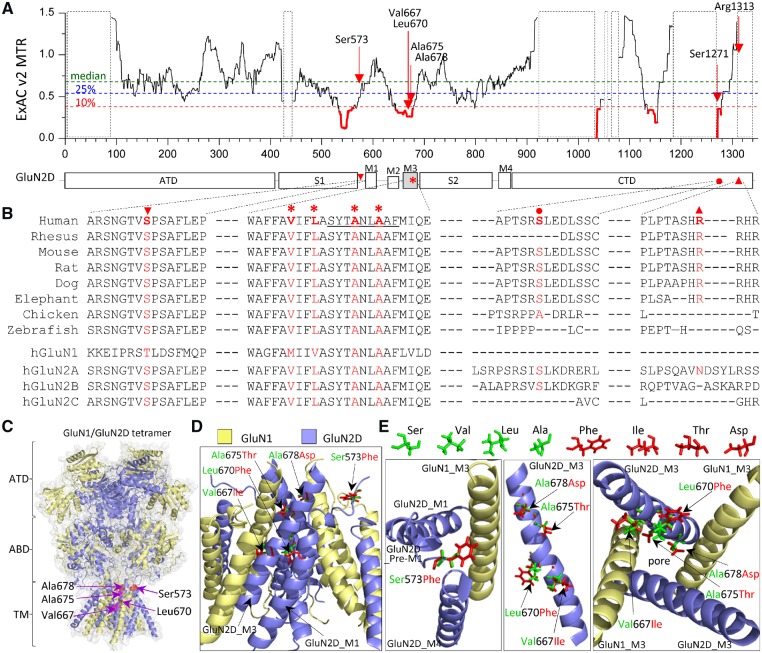

Identification of seven GRIN2D/GluN2D missense mutations

We identified six novel variants in GRIN2D not reported in the literature previously and one GRIN2D variant at a site of recurrent missense variation in a patient not reported previously (all variants refer to NM_000836), all with DEE. These variants are Ser573Phe (S573F), Val667Ile (V667I), Leu670Phe (L670F), Ala675Thr (A675T), Ala678Asp (A678D), Ser1271Leu (S1271L), and Arg1313Trp (R1313W); Leu670Phe is recurrent in two unrelated individuals (Table 1). Intolerance analysis of genetic variation (Traynelis et al., 2017) across functional domains reveals regional variation of purifying selection within GRIN2D/GluN2D (Fig. 3A). The missense variant Ser573Phe is located in the pre-M1 helix, and Val667Ile, Leu670Phe, Ala675Thr, and Ala678Asp are located in transmembrane domain M3, two regions highly intolerant to genetic variations (Fig. 3A). The Val667Ile variant was previous reported in two unrelated individuals with early-onset epileptic encephalopathy and the functional evaluation showed a strong gain-of-function (Li et al. 2016). The missense variants Ser1271Leu and Arg1313Trp are both located in the intracellular domain CTD, a domain of the protein that is either intolerant to genetic variation or not determined because of insufficient genetic information (Fig. 3A). All of these residues are highly conserved in different vertebrate species and/or GluN subunit family (Fig. 3B), suggesting an important role in receptor function. Both GluN2D pre-M1 helix and M3 transmembrane domain are involved in NMDAR channel gating, and interact with the GluN1 pre-M4 region/M4 transmembrane domain (Fig. 3C and D). The substitutions of Phe, Leu, Thr and Asp at positions of 573, 670, 675 and 678 may alter the process whereby ligand binding catalyses opening of the ion channel pore. In this study, we performed experiments on all six variants to evaluate their functional properties.

Figure 3.

Location of seven missense variants in GRIN2D/GluN2D. (A) Intolerance analysis of genetic variation across functional domains within GRIN2D/GluN2D. observed/expected mutant ratios (OE-ratio) below the 10th percentile are in red and indicate the regions under purifying selection (Traynelis et al., 2017). Residue Ser573 is located in pre-M1 helix, linker region between agonist binding domain S1 and transmembrane domain M1. Residues Val667, Leu670, Ala675, and Ala678 are located in transmembrane domain M3, one of the least tolerant regions. Residues Ser1271 and Arg1313 are located in intracellular CTD. The regions highlighted with a dashed box have insufficient data available. ATD = amino-terminal domain; S1, S2 comprise the ABD (agonist binding domain); M1, M2, M3, M4 comprise the transmembrane domain; CTD = carboxyl-terminal domain. (B) The residues of Ala675 and Ala678 are highly conserved across other vertebrate species and all other GluN subunits. The residues Ser573, Val667 and Leu670 are highly conserved across other vertebral species and all other GluN2 subunits, but not the GluN1 subunit. The residues Ser1271 and Arg1313 are conserved in most vertebral species evaluated, but not in other GluN subunits. (C) Homology model of the GluN1/GluN2D receptor built (Li et al., 2016) from the GluN1/GluN2B crystallographic data (PDB: 4PE5; Lee and Chung, 2014; Karakas and Furukawa, 2014) is shown as ribbon structure overlaid by space-filled representation. The GluN1 subunit is yellow and the GluN2D subunit is blue. The positions of p.Ser573Phe, Val667Ile, Leu670Phe, Ala675Thr and Ala678Asp are highlighted by red in the pre-M1 helix and M3 domain. (D) The tetrameric GluN1/GluN2D transmembrane region (ATD and ABD removed) viewed from the side. (E) Potential interaction between GluN2D pre-M1, GluN1-M3, and GluN2D-M4 top-down through the pore (left), side view of one GluN2D M3 domain (middle), and M3 domains of two GluN1 and two GluN2D viewed from the bottom through the pore (right). Wild-type residues Ser, Val, Leu and Ala are green, and mutant residues Phe, Ile, Thr, and Asp are shown as red.

Effects of GluN2D variants on agonist potency

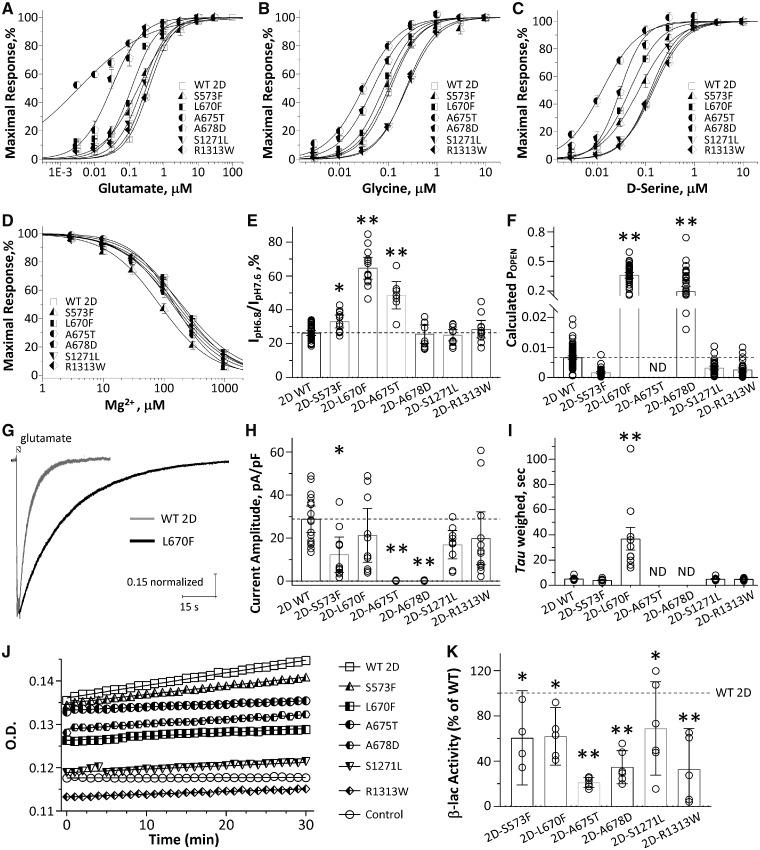

TEVC current recordings in X. laevis oocytes were performed to evaluate the functional effects of these six GluN2D variants co-expressed with wild-type GluN1. Composite concentration-response curves were generated for the endogenous NMDAR co-agonists glutamate, glycine, and d-serine to evaluate whether the missense variants changed agonist potency. Analysis of these data show that GluN2D(Ala675Thr)-containing NMDARs had a statistically significant 19-fold increase of glutamate potency (EC50: 0.02 μM versus 0.39 μM for wild-type in the presence of 10–100 μM glycine, P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test; the same statistical test was used in the following experiments unless otherwise noted), a 3-fold increase of glycine potency (EC50: 0.04 μM versus 0.12 μM for wild-type in the presence of 10 μM glutamate, P < 0.001), and a 14-fold increase of d-serine potency (EC50: 0.01 μM versus 0.14 μM for wild-type in the presence of 10–30 μM glutamate, P < 0.001). NMDARs that contain GluN2D(Ala678Asp) also had 13-fold increase of glutamate potency (EC50: 0.03 μM, P < 0.001), a 2-fold increase of glycine potency (EC50: 0.06 μM, P < 0.001) and a 3.5-fold increase of d-serine potency (EC50 = 0.04 μM, P < 0.001) (Table 2). NMDARs that contain GluN2D(Leu670Phe) also had 3.3-fold increase of glutamate potency (EC50: 0.12 μM, P < 0.001), a modest, but significant increase of glycine potency (EC50: 0.09 μM, P < 0.001) and a 2.8-fold increase of d-serine potency (EC50 : 0.05 μM, P < 0.001) (Table 2). NMDARs that contained GluN2D(Ser573Phe) showed a more modest, but significant increase of glycine potency (EC50: 0.09 μM, < 2-fold change, P < 0.01) and d-serine (EC50: 0.08 μM, < 2-fold change, P < 0.01) (Fig. 4A–C and Table 2). These data suggest that the mutant receptors can be activated by lower concentrations of agonists. However, NMDARs that contained GluN2D(Ser1271Leu) and GluN2D(Arp1313Trp) showed a mild significant decrease of glycine potency (Ser1271Leu: 0.24 μM, P < 0.001; Arp1313Trp: 0.23 μM, P < 0.01) with glutamate and d-serine potency that is comparable to wild-type receptors (Fig. 4A–C and Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of pharmacological properties of wild-type and six GRIN2D variants

| Wild-type 2D | S573F | L670F | A675T | A678D | S1271L | R1313W | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glutamate, EC50, μM (n) | 0.39 ± 0.02 (30) | 0.31 ± 0.04 (12)* | 0.12 ± 0.02 (12)*** | 0.02 ± 0.004 (12)*** | 0.03 ± 0.01 (11)*** | 0.25 ± 0.03 (12) | 0.31 ± 0.03 (12) |

| Glycine, EC50, μM (n) | 0.12 ± 0.01 (38) | 0.09 ± 0.01 (11) | 0.09 ± 0.02 (12)*** | 0.04 ± 0.005 (13)*** | 0.06 ± 0.01 (13)*** | 0.24 ± 0.02 (13)*** | 0.23 ± 0.01 (14)** |

| D-serine, EC50, μM (n) | 0.14 ± 0.01 (29) | 0.08 ± 0.005 (12)*** | 0.05 ± 0.01 (12)*** | 0.01 ± 0.002 (15)*** | 0.04 ± 0.01 (11)*** | 0.13 ± 0.01 (12) | 0.15 ± 0.02 (12) |

| I0.03 gly / I10 gly @-60 mV, (n) | 0.11 ± 0.04 (14) | NA | NA | 0.44 ± 0.04 (12)*** | 0.37 ± 0.06 (9)*** | NA | NA |

| I0.03 gly / I10 gly @ + 40 mV, (n) | 0.11 ± 0.04 (14) | NA | NA | 0.42 ± 0.07 (12)*** | 0.26 ± 0.03 (9) | NA | NA |

| Mg2+, IC50, μM (n)a | 158 ± 11 (31) | 91 ± 12 (9)* | 199 ± 0.6 (16) | 152 ± 11 (10) | 160 ± 23 (11) | 217 ± 0.8 (13) | 190 ± 0.8 (13) |

| Proton, % (n)b | 26 ± 0.7 (38) | 33 ± 1.7 (12)* | 65 ± 3.0 (13)*** | 49 ± 3.4 (8)*** | 26 ± 2.4 (10) | 25 ± 1.5 (12) | 29 ± 2.3 (11) |

| Calculated POPEN | 0.0067 ± 0.0003 (112) | 0.0016 ± 0.0002 (46)*** | 0.36 ± 0.01 (49)*** | ND | 0.20 ± 0.02 (44)*** | 0.0032 ± 0.0003 (44) | 0.0025 ± 0.0003 (40) |

| Surface/total, % (beta-lac assay) | 1 (14) | 0.60 ± 0.13 (4)** | 0.62 ± 0.09 (5)** | 0.21 ± 0.02 (6)*** | 0.35 ± 0.06 (6)*** | 0.69 ± 0.16 (6)* | 0.33 ± 0.13 (5)*** |

| Current amplitude, pA/pF | 29 ± 2.9 | 12 ± 3.6** | 21 ± 5.5 | 0.07 ± 0.03*** | 0.12 ± 0.04*** | 17 ± 2.8 | 20 ± 5.6 |

| Deactivation τW, ms | 5516 ± 255 | 4018 ± 361 | 36 869 ± 8978*** | ND | ND | 4992 ± 428 | 4933 ± 225 |

| Charge transfer, ms × pA/pF | 146 060 | 53 179 | 792 976*** | ND | ND | 86 056 | 96 335 |

| n | 16 | 10 | 10 | 15 | 14 | 9 | 12 |

| Memantine, IC50, μM (n; %)c | 2.5 ± 0.5 (19; 89) | NA | >150 (11; 11)*** | 11 ± 0.9 (12; 76)*** | 5.8 ± 0.9 (14; 81)*** | NA | NA |

| Dextromethorphan, IC50, μM (n; %)c | 5.1 ± 0.7 (18; 91) | NA | >300 (13; 28)*** | 10 ± 0.6 (21; 90)*** | 6.8 ± 0.7 (22; 94) | NA | NA |

| Dextrorphan, IC50, μM (n; %)c | 0.9 ± 0.1 (17; 92) | NA | >100 (12; 21)*** | 2.9 ± 0.2 (17; 80)*** | 1.7 ± 0.2 (17; 88) | NA | NA |

| Ketamine, IC50, μM (n; %)c | 4.5 ± 0.6 (18; 91) | NA | >2,000 (13; 14)*** | 25 ± 3.0 (13; 80)*** | 5.1 ± 0.8 (15; 89) | NA | NA |

Data were expressed as mean ± SEM, (n) is the number of cells recorded from. NA = not available; ND = not determined.

P-value was determined by one-way ANOVA with post hoc Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 compared with wild-type GluN2D.

aHolding potential was −60 mV.

bPercentage of current remaining measured at pH 6.8 compared to pH 7.6 in presence of 100 μM glutamate and 100 μM glycine is given.

cData are ratio of current in drug to current in absence of drug, presented as mean ± SEM. (n; max inhibition % at 30 μM memantine, 100 μM dextromethorphan, 10 μM dextrorphan, and 100 μM ketamine).

Figure 4.

The mutant GluN2D receptors change NMDAR pharmacological and biophysical properties, and reduce cell surface expression. (A–C) Composite concentration-response curves for glutamate (A, in the presence of 30–100 μM glycine), glycine (B; in the presence of 10 μM glutamate), and d-serine (C; in the presence of 10–30 μM glutamate) at VHOLD −40 mV. Smooth curves are Equation 1 fitted to the data. (D) Composite concentration-response curves for Mg2+ (in the presence of 100 μM glutamate and 100 μM glycine) at holding potential −60 mV. Smooth curve is Equation 2 fitted to the data. (E) Summary of proton sensitivity, evaluated by current ratio at pH 6.8 to pH 7.6 at holding potential −40 mV. (F) Summary of calculated channel open probability (POPEN) evaluated by the degree of MTSEA potentiation at holding potential −40 mV (see ‘Materials and methods’ section; ND = determined). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 compared to wild-type GluN2D, one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. (G) Representative whole cell voltage clamp current recordings (normalized) are shown in response to application (1.5-s duration) of 10 μM glutamate (10 μM glycine was in all solutions) from wild-type GluN2D- (grey) and GluN2D-L670F- (black) transfected HEK293 cells. (H and I) Summary of current amplitudes and weighted deactivation time course. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, one way ANOVA, with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons. Fitted parameters are given in Table 2. (J) Representative plots of nitrocefin absorbance (optical density, OD) versus time are shown for HEK293 cells expressing wild-type or mutant GluN2D. β-lac-GluN1 was present in all conditions except control cells. (K) The slopes of OD versus time were averaged (n = 4–6 independent experiments) and graphed as percentages of wild-type for the ratio of surface/total. Data in all composite concentration-response curves (A–D) are mean ± SEM. Data in all bar graphs (E, F, H, I and K) are mean ± 95% CI (confidence interval). Data were analysed by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test compared to wild-type (surface/total ratio, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

We also evaluated the current-voltage relationship for 0.03 μM and 10 μM glycine in the presence of 10 μM glutamate using TEVC recording from oocytes expressing wild-type or mutant NMDARs. The holding potential was changed from −90 mV to +40 mV, before and after NMDAR activation, and the agonist-activated current response isolated and plotted as a function of voltage. GluN2D(Ala675Thr) mutant receptors showed significantly 4-fold higher current at both −60 mV (0.44 versus 0.11, P < 0.001, paired t-test) and +40 mV (0.42 versus 0.11, P < 0.001, paired t-test) compared with wild-type, while GluN2D(Ala678Asp) mutant receptors showed a 3.4-fold higher current at −60 mV (0.37 versus 0.11, P < 0.001, paired t-test) and a 2.4-fold higher current at +40 mV (0.26 versus 0.11) (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Table 2). These data are consistent with the changes in glycine potency of GluN2D(Ala675Thr) and GluN2D(Ala678Asp).

Effects of GluN2D variants on sensitivity to negative allosteric modulators

One of the most important features of NMDAR function is the regulation by endogenous negative allosteric modulators, such as extracellular Mg2+ and protons (Traynelis et al., 2010; Glasgow et al., 2015). We evaluated the effect of variable levels of extracellular Mg2+ on current responses evoked by 100 μM glutamate and 100 μM glycine at a holding potential of −60 mV. The composite concentration-response curves indicated that GluN2D(Ser573Phe) mutant receptors showed an enhanced Mg2+ sensitivity (IC50: 104 μM versus 158 μM of the wild-type, P < 0.05), while GluN2D(Leu670Phe), GluN2D(Ala675Thr), GluN2D(Ala67 8Asp), GluN2D(Leu1271Phe) and GluN2D(Arp1313Trp) had comparable Mg2+ IC50 values compared to the wild-type receptors (Leu1271Phe: 199 μM, Ala675Thr: 150 μM, Ala678Asp: 152 μM, Leu1271Phe: 217 μM, Arp1313Trp: 190 μM; P > 0.05; Fig. 4D and Table 2). We evaluated proton sensitivity by comparing the current amplitude recorded at pH 6.8 and pH 7.6 in response to 100 μM glutamate and 100 μM glycine at a holding potential of −40 mV. The data showed that for GluN2D(Ser573Phe), GluN2D(Leu670Phe), and GluN2D(Ala675Thr) mutant receptors, more current remained at pH 6.8 (Ser573Phe: 33%, Leu670Phe: 65%, Ala675Thr: 49% versus 26% for wild-type, P < 0.001), indicating a reduced sensitivity to the concentration or protons present at physiological pH (i.e. ∼50 nM H+; Fig. 4E and Table 2). GluN2D(Ala678Asp), Ser1271Leu and Arp1313Trp mutant receptors showed no detectable change in proton sensitivity (Ala678Asp: 26%, Ser1271Leu: 25%, Arp1313Trp: 29% current at pH 6.8 versus 26% for wild-type; Fig. 4E and Table 2).

Effects of GluN2D variants on channel open probability

To evaluate the effects of these missense variants on channel open probability (POPEN), we measured the MTSEA-induced potentiation of receptors harbouring a Cys substitution within the SYTANLAAF region of GluN1 by TEVC recording from oocytes. The current response of NMDARs co-expressing wild-type or mutant GluN2D with GluN1(A652C) at holding potential of −40 mV in the presence of 100 μM glutamate and 100 μM glycine is enhanced by treatment with the covalent modifying reagent MTSEA, as modified receptors have their channel locked open (Yuan et al., 2005). Evaluation of the open probability using this method indicated that GluN2D(Leu670Phe) mutant receptors have a 54-fold higher calculated POPEN and the GluN2D(Ala678Asp) mutant receptors have a 29-fold higher calculated POPEN compared to wild-type receptors (Leu670Phe: 0.36, Ala678Asp: 0.20 versus 0.0067, P < 0.001; Fig. 4F and Table 2), the GluN2D(Ser573Phe), GluN2D(Ser1271Leu) and GluN2D(Arg1313Trp) mutant receptors showed no significant change in calculated POPEN than wild-type receptors (Ser573Phe: 0.0016, Ser1271Leu: 0.0032, Arg1313Trp: 0.0025 versus 0.0067 of wild-type, P > 0.05; Fig. 4F and Table 2). However, the GluN2D(Ala675Thr) mutant showed no MTSEA potentiation (current responses with MTSEA were smaller than the one with agonists, data not shown), suggesting this mutation may interfere the ability of MTSEA to lock the NMDARs in open state by covalently labelling A652C of the GluN1 subunit. Alternatively, covalent modification alters the single channel conductance of mutant receptors in unexpected ways.

Effects of GluN2D variants on current amplitude and response time course

It has been suggested that the time course of the NMDAR current response controls the slow component of the excitatory postsynaptic current at synapses (Lester et al., 1990). To investigate whether the GluN2D variants influence current response time course, we performed whole cell voltage clamp current recordings on transiently transfected HEK293 cells and measured the current response following the rapid removal of glutamate (Fig. 4G). NMDARs containing Ser573Phe, Ala675Thr, and Ala678Asp showed reduced current amplitude to application of 10 μM glutamate and 10 μM glycine (P < 0.05, one way ANOVA) (Fig. 4H and Table 2). The glutamate deactivation response time rate was fitted by two exponential components and compared to that for the wild-type GluN2D receptor. The variant Leu670Phe slowed the weighted deactivation time constant τw from 5.5 s to 37 s (P < 0.05, one way ANOVA; Fig. 4G, I and Table 2). The variants GluN2D(Ser573Phe), GluN2D(Ser1271Leu), and GluN2D(Arg1313Trp) showed a comparable weighted deactivation time rate to the wild-type receptors (Fig. 4I and Table 2). The deactivation time course for GluN2D(Ala675Thr) and GluN2D(Ala678Asp) could not be determined because of the low amplitude of the current response. These data suggest NMDARs that contained GluN2D variants influence amplitude of current response and deactivation response time constant.

Effects of GluN2D variants on NMDAR trafficking

To test if the GluN2D variants influence NMDAR surface expression, the cell surface protein level and total protein level were measured using a reporter assay in which beta-lactamase was fused to the extracellular ATD of GluN1 (β-lac-GluN1), and the fusion protein co-expressed with wild-type or mutant GluN2D in HEK293 cells. Beta-lactamase will cleave the cell-impermeable chromogenic substrate nitrocefin in the extracellular solution, allowing a determination of surface receptor expression (Lam and Sherman, 2013; Swanger et al., 2016). NMDARs containing each of the six variant GluN2D subunits showed a significant decrease of surface-to-total protein level, which is a measure of trafficking efficiency, compared to wild-type GluN2D receptors (Ser573Phe was 60 ± 13% of wild-type, P < 0.01; Leu670Phe was 62 ± 9% of wild-type, P < 0.01; Ala675Thr was 21 ± 1.8% of wild-type, P < 0.001, Ala678Asp was 35 ± 5.7% of wild-type, P < 0.001; Ser1271Leu was 69 ± 16% of wild-type, P < 0.05; Arg1313T rp was 33 ± 13% of wild-type, P < 0.001) (Fig. 4J, K and Table 2).

Effects of GluN2D(Ala678Asp) on neuronal excitotoxicity

We selected GluN2D(Ala678Asp) to test for potential neurotoxicity in neurons. To assay cell viability, cultured cortical neurons were transfected with luciferase cDNA as a reporter, along with either vector (pCI-neo), wild-type GluN2D, or GluN2D(Ala678Asp) cDNA. Each transfection condition was performed in the presence of either vehicle or memantine (50 μM; mem). Luciferase assays were performed 24 h following transfection, under the assumption that the level of active luciferase is a measure of live neurons (Aras et al., 2008; Li et al., 2016; Ogden et al., 2017). Each experiment was carried out in quadruplicate, and six independent experiments were performed. Each condition was normalized to its corresponding vector-transfected group to obtain relative viability values. This luciferase assay showed a significant decrease in neuronal viability following transfection of cortical neurons for a 24-h period with GluN2D(Ala678Asp) (0.3 μg cDNA/well) to 55 ± 5.9% of control vector versus 86 ± 5.9% of control vector for wild-type GluN2D, P < 0.01; Fig. 5A). A 24-h co-treatment with 50 μM memantine was able to restore cell viability to 77% of control vector (Fig. 5A). The confocal images of neurons transfected with 60% GFP (0.9 μg cDNA/well) and 20% Ala678Asp did not reveal a significantly altered phenotype or membrane blebbing, making the toxicity we observe for this variant different from that previously described for other GluN2 gain of function variants (Li et al. 2016; Ogden et al., 2017) (Fig. 5B and C). Dendritic blebbing and dendritic swellings were not routinely noted in cells expressing Ala678Asp (Fig. 5B).

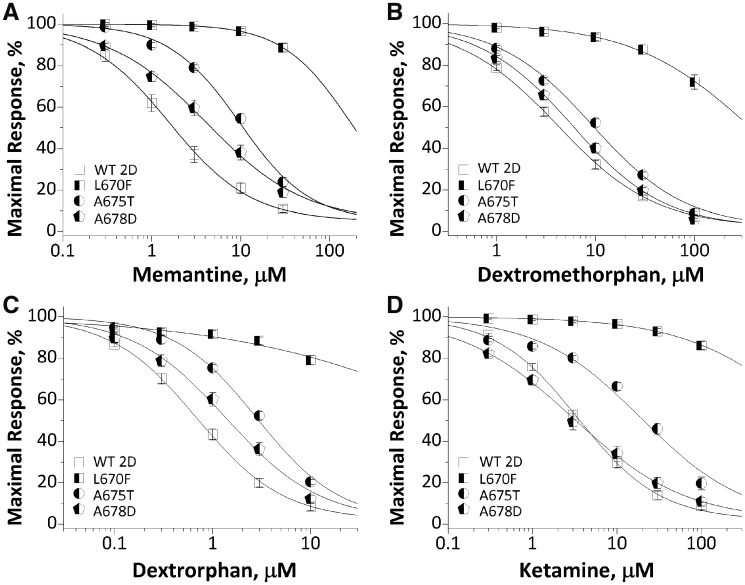

Rescue pharmacology of GluN2D(Leu670Phe), GluN2D(Ala675Thr) and GluN2D(Ala678Asp)

The electrophysiological results suggest that GluN2D (Leu670Phe), GluN2D(Ala675Thr) and GluN2D (Ala678Asp) result in prolonged response time course and/or enhanced agonist potency. We therefore evaluated a set of FDA-approved NMDAR channel blockers for their ability to offset dysregulation of NMDAR function in TEVC recordings from oocytes at holding potential of −40 mV. The data showed all four NMDAR channel blockers (memantine, dextromethorphan, dextrorphan, and ketamine) inhibited mutant GluN2D(Leu670Phe)-containing NMDAR function with a significantly reduced potency (increased IC50 values) (Fig. 6 and Table 2). GluN2D(Ala678Asp)-containing NMDARs also showed reduced potency for all blockers evaluated, except for ketamine, which had comparable potency to the wild-type receptors (4.2 μM versus 3.6 μM of wild-type, P = 0.97, one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test) (Fig. 6 and Table 2). These data raise the possibility that low subanaesthetic doses of ketamine might reduce GluN2D(Ala678Asp)-mediated hyperactivity of NMDAR with similar potency compared with wild-type GluN2D receptors. The differential response of these variant receptors to NMDAR channel blockers reflect that the different channel blockers may engage different structural determinants at their binding site in the channel pore, as previous studies have shown that channel blockers (e.g. memantine/MK-801) bind in a vestibule just above the apex of the M2 re-entrant loop and delimited by M3 α-helices (Lü et al., 2017; Fedele et al., 2018; Song et al., 2018). Variants in both M2 and M3 are known to affect channel blocker potency (Limapichat et al., 2013).

Figure 6.

Effects of FDA-approved NMDAR channel blockers on wild-type and mutant GluN1/GluN2D receptors. Composite concentration-response curves of FDA-approved NMDAR antagonists were evaluated by TEVC recordings from Xenopus oocytes in the presence of 100 μM glutamate and 100 μM glycine at holding potential of −40 mV. (A) memantine, (B) dextromethorphan, (C) dextrorphan, and (D) ketamine. Data are mean ± SEM. Smooth curves are Equation 2 fitted to the data.

Discussion

We report six novel variants and one recurrent missense variant in GRIN2D, identified independently in eight unrelated probands with DEE. Previously, there have been five reported cases of GRIN2D-associated DEE (Asp449Asn, Val667Ile in two patients, Met681Ile, and Ser694Arg) (Li et al., 2016; Tsuchida et al., 2018). Including those reported here and those reported previously, in total there are 10 GRIN2D variants associated with 13 cases, one in the pre-M1 domain (Ser573Phe), one in S1 domain (Asp449Asn), five in the M3 domain (Val667Ile, Leu670Phe, Ala675Thr, Ala678Asp, and Met681Ile), one in the S2 domain (Ser694Arg) and two in the CTD (Ser1271Leu and Arg1313Trp). Only one variant p.Val667Ile had been investigated previously for the functional changes and showed significantly altered macroscopic and single channel properties. These functional changes have been proposed to underlie the aetiology of the early infantile epileptic encephalopathy-46 (EIEE46) (OMIM#617162, Li et al., 2016).

DEE is the unifying phenotype across all 13 patients. Epilepsy data were available for nine cases: 44% (4/9) patients had epilepsy as their initial symptom, while 56% (5/9) patients were evaluated because of developmental delay that preceded seizure onset. We did not find any relationship between the age at onset, types of seizure, EEG pattern, and the degree of developmental delay with the location of the GluN2D amino acid affected by the GRIN2D variant. The age of onset ranged from 2 days to 3 year 5 months of age. EEG results available for nine cases could be divided into two groups; 56% (5/9) patients showed (multi)focal spikes; and 44% (4/9) patients showed hypsarrhythmia. The seizure types ranged from focal seizures, atypical absence seizures, tonic or atonic seizures, to epileptic spasms. Most patients had intractable seizures, but three patients (two with Val667Ile and one with Ala678Asp) were seizure-free on a combination of multiple anti-epileptic drugs and/or NMDAR-targeted combination therapy. In addition to the core phenotypic features of epilepsy and developmental delay/intellectual disability (consistent with DEE), 8 of 13 patients showed certain degree of hypotonia and movement disorders, three patients have autistic behaviour and one patient showed symptoms of ADHD. Brain MRI for one patient (Asp449Asn) shows loss of white matter and thin corpus callosum at 7.5 months old (Tsuchida et al., 2018), and four patients (Val667Ile, two of Leu670Phe, and Arg1313Trp) show mild to moderate cerebral atrophy. These data suggest that the range of potential additional features may develop over time in patients with GRIN2D variants. The presences of brain abnormalities at an early stage are consistent with the idea that GRIN2D plays a role in development. Moreover, this raises the idea that early intervention with therapeutic strategies that rectify aberrant GluN2D activity might improve patient outcome by preventing developmental abnormalities. Early treatment may therefore identify a window of opportunity during which rectification of NMDAR deficits prevent full development of problems with long term consequences.

Some patients in the literature and in our cohort were trialled on memantine, which was administered in a clinical setting as a medication trial like other anti-epileptic drug trials. Its use was based on the premise that memantine represented rational therapy given the understanding of its actions on GRIN2D function (Kotermanski and Johnson, 2009), its well-known safe profile in children (Chez et al., 2007; Erickson et al., 2007), as well as its anti-convulsant effects in almost all animal models of epilepsy (Ghasemi and Schachter, 2011). The divergent response to memantine treatment between Patient 1 in Li et al. (2016) and another two patients [Patient 2 in Li et al. (2016) and the new patient in this study] may be related to the later age at which treatment was initiated for the Patient 1 (at 6.5 years of age) compared to 1–2 years of age for another two patients, suggesting complexity, challenges, and potential therapeutic windows of opportunity in personalized/precision medicine (Kearney, 2017). While in vitro assays of responsiveness to memantine and other such agents may be helpful in predicting whether a given patient may or may not respond, they are not sufficient to gauge the effects of timing of treatment. Further, while we conceptualize these disorders as DEEs with both epilepsy and developmental consequences of GRIN2D-mediated dysfunction, it is clear that treatment with memantine, at least at the times given to the patients described, may ameliorate seizures but is not currently able to rectify the developmental consequences of this condition.

Evaluating genetic variation across the functional domains of GluN2D revealed the regions (e.g. transmembrane domain M3, Fig. 3A) under purifying selection, indicating that functional variation therein is likely to be deleterious and pathogenic. The residues of Ala675 and Ala678 are conserved through all vertebral species and across all other GluN subunits. The residue Ser573, Val667 and Leu670 are highly conserved across other vertebral species and all other GluN2 subunits, but not the GluN1 subunit. The residue Ser1271 and Arg1313 are conserved in most vertebral species evaluated, but not in other GluN subunits (Fig. 3B). Ser573, Val667, Leu670, Ala675, and Ala678 also are invariant in the healthy population in all NMDARs, and Arg1313 is located in a region with incomplete data with which to judge variation in GRIN2D (gnomAD, http://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/; evaluated on November 06, 2018), indicating potential important roles in channel function. We evaluated NMDAR functional changes caused by all six GRIN2D missense variants using a heterologous expression system and primary cultured neurons. Our data show that GluN2D(Ser573Phe), should be a loss-of-function variant since it decreased channel open probability by 4.2-fold, reduced cell surface receptor expression by 40%, and mildly enhanced Mg2+ inhibition, although it modestly increased glycine/d-serine potency and modestly reduced proton inhibition. GluN2D(Ser1271Leu) and GluN2D(Arg1313Trp) also appear to be loss-of-function variants because both mildly decreased glycine potency and channel open probability by ∼2-fold, and reduced cell surface expression by 32% and 67%, respectively. The GluN2D(Leu670Phe) variant significantly enhanced glutamate potency by 3-fold, reduced proton inhibition (35% versus 74% inhibition of wild-type), prolonged response deactivation time course (by 7-fold), increased charge transfer (by 5-fold), and increased channel open probability (by 54-fold), suggesting a gain-of-function variant, although the variant also showed a reduced cell surface trafficking by 38%. The functional status for GluN2D(Ala675Thr) and GluN2D(Ala678Asp) is difficult to definitively determine because of the complexity of the functional changes we observed. Both variants show strongly enhanced agonist potency (e.g. glutamate and glycine potency increased up to 19-fold), reduced proton inhibition (e.g. Ala675Thr, by 2-fold), and increased channel open probability (e.g. Ala678Asp, by 29-fold). According to these functional parameters, it should be considered gain-of-function variant. However, the patch clamp recordings from transfected mammalian cells showed significantly reduced current amplitude and the β-lactamase reporter assay revealed reduced surface-to-total ratios for these two variants when expressed in mammalian cells by 79% and 65%, respectively (Fig. 4H and I); it is unknown whether receptor density at synapses is similarly reduced. Combining the data we have, we can assess the potential for gain- or loss-of-function for these variants (Swanger et al., 2016). Further in vivo study using transgenic mice expressing this mutant allele will be necessary to elucidate the functional status of these variants.

Overall, this work further emphasizes the importance of functional and biochemical validation for each individual variant. The combination of rapidly growing array of genomic sequencing data with functional evaluation of specific molecular mechanism and potential rescue pharmacology in vitro may provide a better understanding of disease mechanism, diagnosis, as well as choice of precision medicine for a subset of severe pediatric neurodevelopmental diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients, families, and referring physicians for their participation in this study and for providing clinical data for phenotyping. The authors thank Jing Zhang, Phuong Le, Gil Shaulsky, and Sukhan Kim for technical support. We also thank Dr Sharon A. Swanger for advice and assistance, Dr Pieter Burger for creating a homology model of human GluN2D, and Dr Taoyun Ji for reviewing of the electroencephalographic and neuroimaging data of Patients 2, 3, 6 and 7.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- DEE

developmental and epileptic encephalopathy

- NMDAR

N-methyl d-aspartate receptor

- TEVC

two-electrode voltage clamp

Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH): the NINDS/NIH (NS036654, NS065371, NS092989 to S.F.T.; NS043277 to E.A.), NICHD/NIH (HD082373 to H.Y.), CSC (201706010321 to W.X.), National Science and Technology Major Project of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2017ZX09304029–006) to Y.W., National Natural Science Foundation of China (81741053), Beijing Natural Science Foundation (7151010), Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission (Z161100000216133, Z161100004916169), Beijing Institute for Brain Disorders Foundation (BIBDPXM2014_014226_000016), Beijing Municipal Natural Science Key Project (15G10050), Beijing key laboratory of molecular diagnosis and study on pediatric genetic diseases (BZ0317), National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFC1306201, 2016YFC0901505), and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (BMU2017JI002, BMU2018XY006). A.P. is supported by the Boston Children’s Hospital Translational Research Program. S.S. was supported by a grant from the Dietmar-Hopp-Stiftung (23011236 to S.S.).

Competing interests

S.F.T. is PI on a research grant from Allergan to Emory University School of Medicine, is a member of the SAB for Sage Therapeutics, is co-founder of NeurOp Inc, and receives royalties for software. S.F.T. is co-inventor on Emory-owned Intellectual Property that includes allosteric modulators of NMDA receptor function. H.Y. is PI on a research grant from Sage Therapeutics to Emory University School of Medicine. N.D. is an SB PhD fellow at FWO.

References

- Aras MA, Hartnett KA, Aizenman E. Assessment of cell viability in primary neuronal cultures. Curr Protoc Neurosci 2008; 44: 7.18.1–7.18.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brainstorm Consortium, Anttila V, Bulik-Sullivan B, Finucane HK, Walters RK, Bras J et al. Analysis of shared heritability in common disorders of the brain. Science 2018; 360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnashev N, Szepetowski P. NMDA receptor subunit mutations in neurodevelopmental disorders. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2015; 20: 73–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Shieh C, Swanger SA, Tankovic A, Au M, McGuire M et al. GRIN1 mutation associated with intellectual disability alters NMDA receptor trafficking and function. J Hum Genet 2017; 62: 589–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chez MG, Burton Q, Dowling T et al. Memantine as adjunctive therapy in children diagnosed with autistic spectrum disorders: an observation of initial clinical response and maintenance tolerability. J Child Neurol 2007; 22: 574–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn P, Albury CL, Maksemous N, Benton MC, Sutherland HG, Smith RA et al. Next generation sequencing methods for diagnosis of epilepsy syndromes. Front Genet 2018; 9: 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedele L, Newcombe J, Topf M, Gibb A, Harvey RJ, Smart TG. Disease-associated missense mutations in GluN2B subunit alter NMDA receptor ligand binding and ion channel properties. Nat Commun 2018; 9: 957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson CA, Posey DJ, Stigler KA, Mullett J, Katschke AR, McDougle CJ et al. A retrospective study of memantine in children and adolescents with pervasive developmental disorders. Psychopharmacology 2007; 191: 141–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao K, Tankovic A, Zhang Y, Kusumoto H, Zhang J, Chen W et al. A de novo loss-of-function GRIN2A mutation associated with childhood focal epilepsy and acquired epileptic aphasia. PLoS One 2017; 12: e0170818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardella E, Marini C, Trivisano M, Fitzgerald MP, Alber M, Howell KB et al. The phenotype of SCN8A developmental and epileptic encephalopathy. Neurology 2018; 91: e1112–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghasemi M, Schachter SC. The NMDA receptor complex as a therapeutic target in epilepsy: a review. Epilepsy Behav 2011; 22: 617–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibb AJ, Ogden KK, McDaniel MJ, Vance KM, Kell SA, Butch C et al. A structurally derived model of subunit-dependent NMDA receptor function. J Physiol 2018; 596: 4057–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow NG, Siegler Retchless B, Johnson JW. Molecular bases of NMDA receptor subtype-dependent properties. J Physiol 2015; 593: 83–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedegaard M, Hansen KB, Andersen KT, Bräuner-Osborne H, Traynelis SF. Molecular pharmacology of human NMDA receptors. Neurochem Int 2012; 61: 601–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helbig KL, Lauerer RJ, Bahr JC, Souza IA, Myers CT, Uysal B et al. De novo pathogenic variants in CACNA1E cause developmental and epileptic encephalopathy with contractures, macrocephaly, and dyskinesias. Am J Hum Genet 2018; 103: 666–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez CC, Kong W, Hu N, Zhang Y, Shen W, Jackson L et al. Altered channel conductance states and gating of GABAA receptors by a pore mutation linked to Dravet syndrome. eNeuro 2017a; 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez CC, Zhang Y, Hu N, Shen D, Shen W, Liu X et al. GABA A receptor coupling junction and pore gabrb3 mutations are linked to early-onset epileptic encephalopathy. Sci Rep 2017b; 7: 15903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyne HO, Singh T, Stamberger H, Abou Jamra R, Caglayan H, Craiu D et al. De novo variants in neurodevelopmental disorders with epilepsy. Nat Genet 2018; 50: 1048–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu C, Chen W, Myers SJ, Yuan H, Traynelis SF. Human GRIN2B variants in neurodevelopmental disorders. J Pharmacol Sci 2016; 132: 115–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karakas E, Furukawa H. Crystal structure of a heterotetrameric NMDA receptor ion channel. Science 2014; 344: 992–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearney JA. Precision medicine: NMDA receptor-targeted therapy for GRIN2D encephalopathy. Epilepsy Curr 2017; 17: 112–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein CJ, Foroud TM. Neurology individualized medicine: when to use next-generation sequencing panels. Mayo Clin Proc 2017; 92: 292–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong W, Zhang Y, Gao Y, Liu X, Gao K, Xie H et al. SCN8A mutations in Chinese children with early onset epilepsy and intellectual disability. Epilepsia 2015; 56: 431–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotermanski SE, Johnson JW. Mg2+ imparts NMDA receptor subtype selectivity to the Alzheimer’s drug memantine. J Neurosci 2009; 29: 2774–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam YW, Sherman SM. Activation of both Group I and Group II metabotropic glutamatergic receptors suppress retinogeniculate transmission. Neuroscience 2013; 242: 78–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KY, Chung HJ. NMDA receptors and L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels mediate the expression of bidirectional homeostatic intrinsic plasticity in cultured hippocampal neurons. Neuroscience 2014; 277: 610–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester RA, Clements JD, Westbrook GL, Jahr CE. Channel kinetics determine the time course of NMDA receptor-mediated synaptic currents. Nature 1990; 346: 565–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D, Yuan H, Ortiz-Gonzalez XR, Marsh ED, Tian L, McCormick EM et al. GRIN2D recurrent de novo dominant mutation causes a severe epileptic encephalopathy treatable with NMDA receptor channel blockers. Am J Hum Genet 2016; 99: 802–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limapichat W, Yu WY, Branigan E, Lester HA, Dougherty DA. Key binding interactions for memantine in the NMDA receptor. ACS Chem Neurosci 2013; 4: 255–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lü W, Du J, Goehring A, Gouaux E. Cryo-EM structures of the triheteromeric NMDA receptor and its allosteric modulation. Science 2017; 355. pii: eaal3729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McTague A, Howell KB, Cross JH, Kurian MA, Scheffer IE. The genetic landscape of the epileptic encephalopathies of infancy and childhood. Lancet Neurol 2016; 1: 304–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden KK, Chen W, Swanger SA, McDaniel MJ, Fan LZ, Hu C et al. Molecular mechanism of disease-associated mutations in the pre-M1 helix of NMDA receptors and potential rescue pharmacology. PLoS Genet 2017; 13: e1006536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson HE, Jean-Marçais N, Yang E, Heron D, Tatton-Brown K, van der Zwaag PA et al. A recurrent de novo PACS2 heterozygous missense variant causes neonatal-onset developmental epileptic encephalopathy, facial dysmorphism, and cerebellar dysgenesis. Am J Hum Genet 2018; 103: 631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paoletti P, Bellone C, Zhou Q. NMDA receptor subunit diversity: impact on receptor properties, synaptic plasticity and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci 2013; 14: 383–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pons L, Lesca G, Sanlaville D, Chatron N, Labalme A, Manel V et al. Neonatal tremor episodes and hyperekplexia-like presentation at onset in a child with SCN8A developmental and epileptic encephalopathy. Epileptic Disord 2018; 20: 289–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med 2015; 17: 405–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song X, Jensen MØ, Jogini V, Stein RA, Lee CH, Mchaourab HS et al. Mechanism of NMDA receptor channel block by MK-801 and memantine. Nature 2018; 556: 515–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strehlow V, Heyne HO, Vlaskamp DRM, Marwick KFM, Rudolf G, de Bellescize J et al. GRIN2A-related disorders: genotype and functional consequence predict phenotype. Brain 2019; 142: 80–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanger SA, Chen W, Wells G, Burger PB, Tankovic A, Bhattacharya S et al. Mechanistic insight into NMDA receptor dysregulation by rare variants in the GluN2A and GluN2B agonist binding domains. Am J Hum Genet 2016; 99: 1261–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thevenon J, Duffourd Y, Masurel-Paulet A, Lefebvre M, Feillet F, El Chehadeh-Djebbar S et al. Diagnostic odyssey in severe neurodevelopmental disorders: toward clinical whole-exome sequencing as a first-line diagnostic test. Clin Genet 2016; 89: 700–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traynelis J, Silk M, Wang Q, Berkovic SF, Liu L, Ascher DB et al. Optimizing genomic medicine in epilepsy through a gene-customized approach to missense variant interpretation. Genome Res 2017; 27: 1715–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traynelis SF, Wollmuth LP, McBain CJ, Menniti FS, Vance KM, Ogden KK et al. Glutamate receptor ion channels: structure, regulation, and function. Pharmacol Rev 2010; 62: 405–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchida N, Hamada K, Shiina M, Kato M, Kobayashi Y, Tohyama J et al. GRIN2D variants in three cases of developmental and epileptic encephalopathy. Clin Genet 2018; 94: 538–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilfert AB, Sulovari A, Turner TN, Coe BP, Eichler EE. Recurrent de novo mutations in neurodevelopmental disorders: properties and clinical implications. Genome Med 2017; 9: 101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright CF, FitzPatrick DR, Firth HV. Paediatric genomics: diagnosing rare disease in children. Nat Rev Genet 2018; 19: 325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]