Abstract

In fish, amphibians, and birds, the loss of hair cells can evoke S-phase entry in supporting cells and the production of new cells that differentiate as replacement hair cells and supporting cells. Recent investigations have shown that supporting cells from mammalian vestibular epithelia will proliferate in limited numbers after hair cells have been killed. Exogenous growth factors such as glial growth factor 2 enhance this proliferation most potently when tested on vestibular epithelia from neonates. In this study, the intracellular signaling pathways that underlie the S-phase entry were surveyed by culturing epithelia in the presence of pharmacological inhibitors and activators. The results demonstrate that phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase is a key element in the signaling cascades that lead to the proliferation of cells in mammalian balance epithelia in vitro. Protein kinase C, mammalian target of rapamycin, mitogen-activated protein kinase, and calcium were also identified as elements in the signaling pathways that trigger supporting cell proliferation.

Keywords: cell proliferation, regeneration, supporting cells, mammals, inner ear, vestibule, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, hearing, rodents, MAPK, p70/p85 S6 kinase

The hearing, balance, and lateral line epithelia of fish, amphibians, and birds have the capacity to recover from sensory deficits by regenerating hair cells (for review, see Corwin and Oberholtzer, 1997). At sites of hair cell loss, supporting cells divide and give rise to progeny that can differentiate as replacement hair cells. In mammals, hearing and balance deficits also arise from hair cell loss, but those deficits are typically permanent (Nadol, 1993). Mammals produce hair cells late in embryonic development. Cell divisions in their otic sensory epithelia decline precipitously and were believed to cease around the time of birth (Ruben, 1967). Recent evidence, however, supports a revised view of the potential for cell proliferation and self-repair in the balance epithelia of mammals.

Balance epithelia in juvenile rodents can heal damage caused by sublethal doses of ototoxic antibiotics administered in vivo(Forge et al., 1993). In vitro treatments with higher levels of antibiotics can kill the majority of the hair cells in vestibular epithelia from adult rodents and humans; when this occurs, limited numbers of supporting cells enter S-phase (Warchol et al., 1993). Subsequent investigations have shown that transforming growth factor-α, epidermal growth factor (EGF), insulin, and insulin-like growth factors can all increase proliferation in cultured mammalian balance epithelia (Lambert, 1994; Yamashita and Oesterle, 1995; Zheng et al., 1997; Kuntz and Oesterle, 1998), as can recombinant human glial growth factor 2 (rhGGF2). RhGGF2 is a secreted member of a family of factors encoded by alternatively spliced transcripts from the neuregulin gene (Marchionni et al., 1993; Riese and Stern, 1998). When vestibular epithelia from newborn rats are cultured in rhGGF2 for 72 hr, >40% of the cells enter S-phase (R. Gu, M. Montcouquiol, M. Marchionni, and J. T. Corwin, unpublished observations).

Binding of growth factors to receptor tyrosine kinases leads to activation of intracellular cascades composed of enzymes and signaling intermediates that could be potential targets for therapeutic control over the regeneration of hair cells; therefore, these targets need to be identified (Corwin and Oberholtzer, 1997). High concentrations of forskolin stimulate supporting cell proliferation in chicken cochleasin vitro, and inhibitors of protein kinase A reduce that effect (Navaratnam et al., 1996), but no signaling cascades that mediate proliferation in mammalian hair cell epithelia have been identified. The potent mitogenic effect of rhGGF2 provided an opportunity to survey intracellular signaling cascades for roles in triggering proliferation in mammalian balance epithelia by culturing epithelia with inhibitors and activators of signaling intermediates in the different pathways that can participate in the control of proliferation in other cell types. Activation of phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase (PI-3K), mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), protein kinase C (PKC), and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), as well as increased intracellular calcium were found to contribute to triggering different levels of S-phase entry and proliferation of cells in balance epithelia from rats.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of epithelial cell cultures. Experiments were conducted in accordance with an approved animal use protocol that adhered to practices outlined in the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals under the supervision of the University of Virginia Animal Care Advisory Committee. This report is based on sensory epithelia cultured from 89 2-d-old (postnatal day 2) Sprague Dawley rats that were killed with carbon dioxide and decapitated. Each head was skinned and disinfected in ice-cold 70% ethanol for 10 min. Next, the vestibular organs from both ears were aseptically transferred to ice-cold DMEM/F-12 medium (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD), and the otoconia and otolithic membranes were removed from the utricles. To separate the sensory epithelium from the underlying tissue, each utricle was incubated in thermolysin at 0.5 mg/ml (Sigma, St Louis, MO) in DMEM/F-12 for 45 min at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere (Saffer et al., 1996). Whole utricles were then transferred to ice-cold DMEM/F-12 containing 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (HyClone, Logan, UT) to stop the digestion, and the epithelium was removed with fine forceps. The surrounding nonsensory epithelium and the outer edges of the sensory macula were trimmed away with a diamond microscalpel and discarded. The remaining pure sensory epithelium was cut into four approximately equal pieces (Fig. 1). The pieces of epithelium were transferred to a glass-bottom culture dish (MatTek, Ashland, MA) that was precoated with poly-l-lysine (5 μg/ml for 1 hr at 37°C; Sigma) and fibronectin (100 μg/ml overnight at 37°C; Sigma). The epithelia were allowed to adhere for 1 hr at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere in medium containing 5% FBS. Next, the adherent epithelia were cultured for 72 hr in DMEM/F-12 containing 3 μg/ml 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine (BrdU) (Sigma), 2.5% FBS, and either DMSO or one of the test compounds.

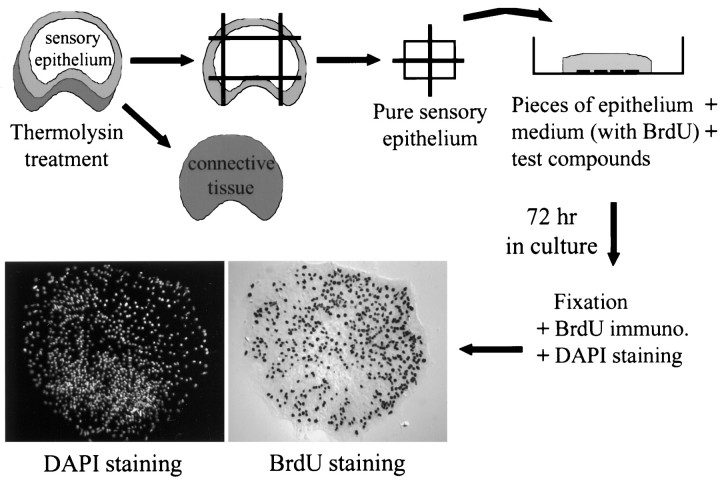

Fig. 1.

Methods used to analyze S-phase entry in vestibular sensory epithelia. Utricles were dissected from 2-d-old rats and incubated with the enzyme thermolysin to separate the sensory epithelium from the underlying connective tissue. The nonsensory epithelium (light gray) was trimmed away, and the remaining pure sensory epithelium was cut into four equal pieces. Pieces of epithelium were transferred to a glass-bottom culture dish in a medium containing BrdU and either vehicle or one of the test compounds. After 72 hr, the cultures were fixed and processed for immunocytochemistry and DAPI staining; next, the fraction of the cells that had entered S-phase and incorporated BrdU during replication of their DNA was calculated from counts of all of the labeled and unlabeled cells.

Test compounds and media. The intracellular signaling mechanisms that are responsible for the entry of supporting cells into S-phase were assessed by incubating sheets of epithelium with the pharmacological activators and inhibitors listed in Table1. Inhibitor concentrations were chosen on the basis of studies that demonstrated inhibition of the target enzyme and/or significant inhibition of the incorporation of BrdU or tritiated thymidine in cultures (references are listed in Table 1). We did not test pathways related to neurotransmitter receptors or ion channels.

Table 1.

List of all the activators and inhibitors used in this study

| Compound name | Target(s) | References |

|---|---|---|

| Inhibitors | ||

| Tyrphostin AG 825 (1) | ErbB2 | Osherov et al., 1993 |

| Wortmannin (2) | PI-3K | Okada et al., 1994a,b |

| LY294002 (1) | PI-3K |

Vlahos et al., 1994

Sanchez-Margalet et al., 1994 |

| Rapamycin (1) | mTOR |

Chung et al., 1992

Brown et al., 1994 |

| FK506 (3) | FKBP12 | Lin et al., 1995 |

| Calphostin C (1) | cPKCs, nPKCs |

Tamaoki et al., 1990

Seynaeve et al., 1994 |

| BIM (1) | PKCs |

Toullec et al., 1991

Martiny-Baron et al., 1993 |

| 1 4-Diamino-2,3-dicyano-1,4-bis (2-aminophenylthio) butadiene (U0126) (1) | MEK1 and MEK2 | Favata et al., 1998 |

| PD98059 (4) | MEK1 |

Alessi et al., 1995

Dudley et al., 1995 |

| Apigenin (1) | ERK/MAPK | Kuo and Yang, 1995 |

| SB203580 (1) | p38-MAPK | Cuenda et al., 1995 |

| Activators | ||

| Anisomycin (5) | JNKs | Cano et al., 1994 |

| DAG (6) | cPKCs, nPKCs | |

| PMA (2) | cPKCs, nPKCs | |

| PI-3,4-P2 (1) | PKCs, Akt/PKB |

Toker et al., 1994

Franke et al, 1997 Klippel et al., 1997 |

| A23187 (2) | Calcium | |

| Ionomycin (2) | Calcium |

Drug sources (in parentheses): 1, Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA; 2, Sigma, St. Louis, MO; 3, Fujisawa, Deerfield, IL; 4, New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA; 5, Biomol, Plymouth Meeting, PA; 6, Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL.

The standard (or control) medium was DMEM/F-12 supplemented with 2.5% FBS and 3 μg/ml BrdU. When test compounds were solubilized in DMSO, control medium also contained DMSO as a vehicle control. Test compounds were added to the standard medium at the concentrations indicated in Results. Each inhibitor was added to the epithelial cultures for 1 hr before the addition of rhGGF2 (Cambridge NeuroScience, Cambridge, MA). RhGGF2 was used at 50 ng/ml throughout the study. The medium was then replaced by the standard medium containing the inhibitor and rhGGF2 for the 72 hr culture period. Wortmannin was added to the medium every 8 hr because of its instability at 37°C (Yao and Cooper, 1996;Parrizas et al., 1997).

Activators were added to the epithelial cultures 15 min before the addition of either standard medium or medium containing rhGGF2, as described in Results. The activators were then removed by replacing the medium with the standard medium, with or without rhGGF2. Anisomycin was added at the same time as standard medium that contained rhGGF2, and remained throughout the 72 hr culture period.

To downregulate PKC, 20 pieces of epithelium were cultured for 16 hr in 5 pm PMA in the standard medium. The medium was then replaced with standard medium that contained rhGGF2 for the remaining 56 hr of the culture.

Bromodeoxyuridine labeling. After culture, epithelia were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min, then rinsed three times in PBS and immersed in 1 N HCl for 15 min to denature nucleic acids. Immunocytochemical identification of nuclei that had incorporated BrdU was performed at room temperature. The cultures were preincubated for 1 hr in TPBS (PBS with 0.2% Triton X-100) with 10% normal horse serum (NHS) and incubated for 2 hr in a mouse monoclonal antibody against BrdU (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) that was diluted 1:50 in TPBS with 2% NHS. After three PBS rinses, the specimens were incubated for 30 min in a secondary antibody solution containing biotinylated rat-adsorbed anti-mouse IgG (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) that was diluted 1:100 in TPBS with 2% NHS. Next, they were processed with avidin, horseradish peroxidase conjugated to biotin, and diaminobenzidine using an Elite avidin–biotin complex (ABC) kit with nickel intensification (Vector Laboratories). The specimens were then incubated in 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) at 10 μg/ml in PBS with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 30 min to stain DNA. After three rinses with PBS, the specimens were examined by epifluorescence microscopy.

MetaMorph software (Universal Imaging, Media, PA) was used to acquire images from a cooled CCD camera (Princeton Instruments, Trenton, NJ) interfaced to a Zeiss Axiovert 135 (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY). All of the nuclei that were stained by DAPI and all of the nuclei that were labeled by BrdU were counted in each piece of epithelium. The labeling index was calculated for each piece of sensory epithelium by dividing the number of BrdU-labeled nuclei by the total number of nuclei in the piece of epithelium (Fig. 1). For each test condition, 24–44 pieces of utricular sensory epithelium were analyzed. Statistical significance was determined using the two-tailed Student's t test.

MAPK immunocytochemistry. Thirty two pieces of sensory epithelium were isolated and trimmed as described above and cultured for 48 hr in DMEM/F-12 with 5% FBS. Next, they were incubated overnight in DMEM/F-12 with 2.5% FBS to reduce the endogenous level of MAPK activation. The medium was then replaced in one set of eight cultures by DMEM/F-12 with 2.5% FBS in the presence of 20 μm U0126, and for eight others by 100 μm PD98059. After 1 hr, eight cultures were treated with DMEM/F-12 with 2.5% FBS (control), eight were treated with DMEM/F-12 with 2.5% FBS in the presence of 20 μm U0126 and 50 ng/ml rhGGF2, eight were treated with DMEM/F-12 with 2.5% FBS in the presence of 100 μm PD98059 and 50 ng/ml rhGGF2, and eight were treated with DMEM/F-12 with 2.5% FBS in the presence 50 ng/ml rhGGF2. After 1 hr, all of the cultures were rinsed with PBS and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS at room temperature for 30 min followed by a methanol permeabilization at −20°C for 10 min. The cultures were rinsed with PBS, blocked in TPBS with 5% NHS, and incubated overnight with a polyclonal antibody to phosphorylated extracellular regulated kinase-1 (ERK-1) and ERK-2 (diluted 1:200 in TPBS with 2% NHS at 4°C) (Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA). After three rinses in PBS, cultures were incubated with biotinylated rat-adsorbed anti-mouse IgG (diluted 1:100 in TPBS with 2% NHS) and processed using an Elite ABC kit with nickel intensification (Vector Laboratories) for11 min.

MAPK SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis. One hundred and ninety-eight pieces of utricular sensory epithelium were cultured in DMEM/F-12 with 5% FBS. After 48 hr, the cultures were incubated overnight at 4°C in DMEM/F-12 with 2.5% FBS and then treated with U0126, PD98059, and rhGGF2 as described above for the MAPK immunocytochemistry. The cultures were then briefly rinsed with cold PBS containing 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 10 μg/ml pepstatin, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 mg/ml 4-(2-aminoethyl)benzenesulfonyl fluoride, 50 mm NaF, and 5 mm EDTA. The pieces of sensory epithelium were harvested in that buffer by scraping. For each of the four conditions, the cells from 48–52 pieces were pooled in an Eppendorf tube and centrifuged at 16,000 ×g for 10 min at 4°C; the pellets were stored at −80°C and subsequently resuspended in lysis buffer containing 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, and 62.5 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, heated at 95°C for 5 min, and sonicated for 10 sec. Protein was measured using the bicinchoninic acid method according to the manufacturer's instructions (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE (20 μg/lane in 4–20% gradient gels) (Novex, San Diego, CA) and transferred to Immobilon-P membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA). Membranes were incubated in 5% (w/v) nonfat dry milk (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.2% Tween 20 (TTBS) overnight at 4°C. Membranes were washed and incubated with a 1:1500 dilution of the phosphospecific antibody to ERK-1 and ERK-2 in TTBS for 2 hr, washed again, and incubated for 1 hr with a peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody (1:10,000 in TTBS). Immunoreactive bands were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham, Princeton, NJ). The membranes were stripped in 2% SDS, 62.5 mm Tris-HCl, and 100 mm β-mercaptoethanol at pH 6.8, with shaking for 45 min at 60°C. Next, they were reprocessed with a mouse anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase antibody (1:1000 in TTBS) (Chemicon, Temecula, CA). Films were scanned and analyzed using a Molecular Dynamics (Sunnyvale, CA) Personal Densitometer and ImageQuant software.

RESULTS

RhGGF2 induces proliferation in an ErbB2 receptor-dependent manner

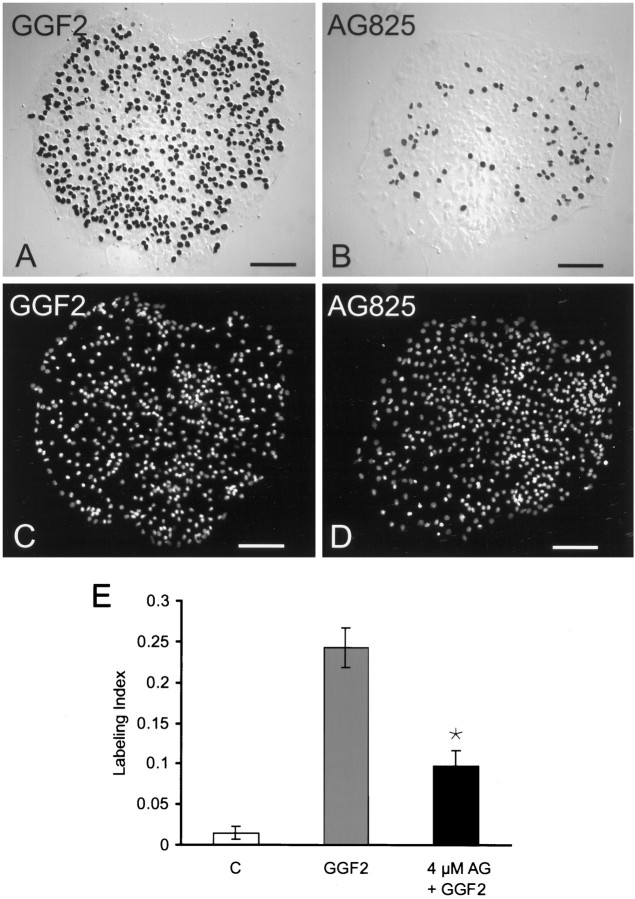

The fraction of cell nuclei that entered S-phase and were labeled with BrdU was >17 times greater in utricular sensory epithelia that were cultured for 72 hr in medium that contained 50 ng/ml rhGGF2 (373 ± 38.6 BrdU-labeled cells; mean ± SEM;n = 39 pieces of epithelium) than in parallel cultures in the standard medium (5.6 ± 1.9 labeled cells;n = 25) (Fig. 2). The rhGGF2-stimulated proliferation was reduced by 60% when epithelia were cultured in medium that also contained the ErbB2 receptor kinase inhibitor AG825 (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Selective inhibition of ErbB2 decreases the incidence of S-phase entry induced by rhGGF2. A, C, Pieces of utricular sensory epithelium fixed after 72 hr in culture in the standard medium with 50 ng/ml rhGGF2. A, Nuclei of cells that entered S-phase and incorporated BrdU were stained black after immunocytochemistry and were visualized by differential interference contrast microscopy. C, Fluorescent DAPI staining revealed the nuclei that did not enter S-phase in the same piece of epithelium. B, D, A piece of epithelium that was preincubated with the ErbB2 inhibitor AG825 at 4 μmfor 60 min and then cultured for 72 hr in the standard medium containing rhGGF2 and 4 μm AG825. All other inhibitors were tested in the same manner unless otherwise noted. The incidence of cells that entered S-phase was qualitatively different in epithelia cultured in the presence of AG825 as shown by the smaller number of darkly stained nuclei in B. E, The fraction of cells that had entered S-phase in the standard control medium (C), in that medium supplemented with 50 ng/ml rhGGF2 (GGF2), and in medium containing both rhGGF2 and 4 μm AG825 (4μm AG + GGF2). Each bar represents data from 26 to 37 pieces of epithelium. Anasterisk denotes significance compared with cultures treated with rhGGF2 alone unless otherwise noted (p < 0.05). Scale bars, 100 μm.

The role of PI-3K and mTOR

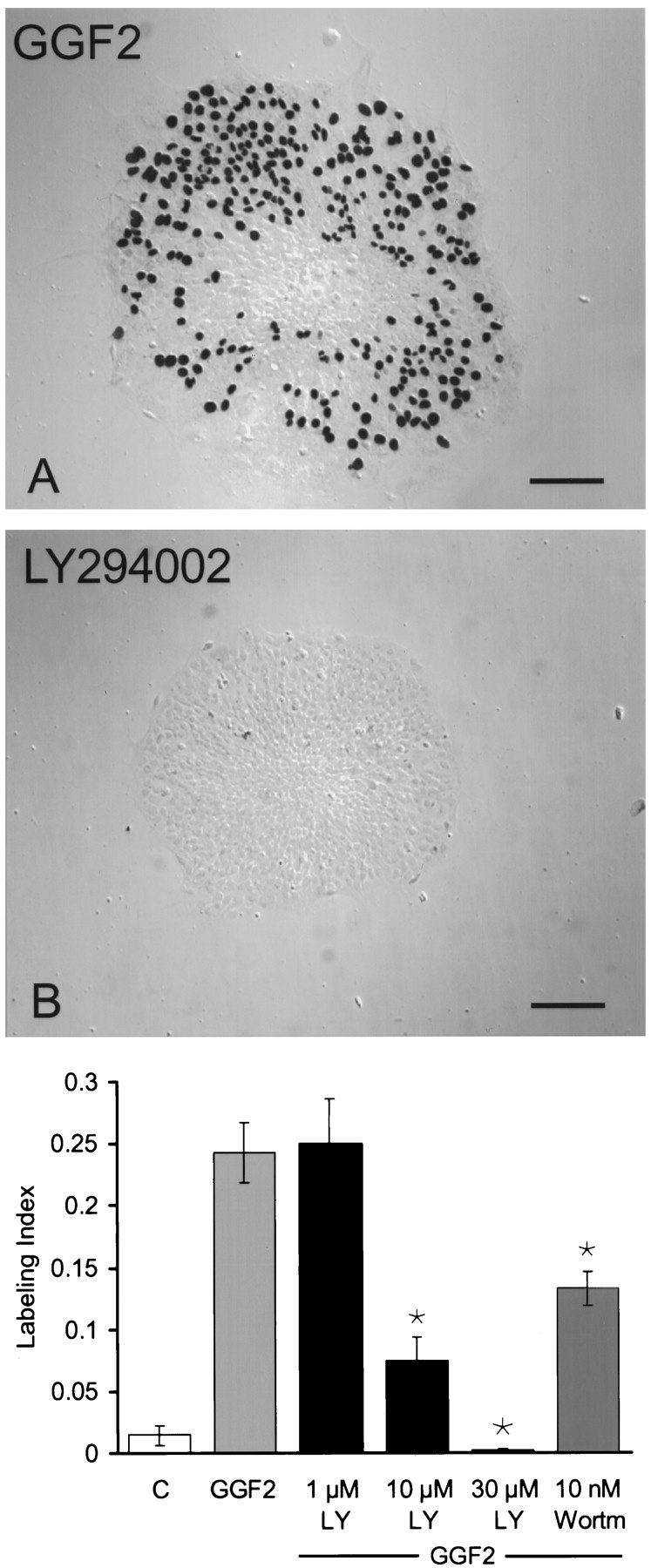

Wortmannin and LY294002 were used to assess the role of PI-3K in proliferation stimulated by rhGGF2. Treatment of epithelia with the PI-3K inhibitor LY294002 caused a dose-dependent inhibition of the rhGGF2-mediated response, with inhibition of nearly all S-phase entry at 30 μm (p < 0.05) (Fig.3B, bottom). LY294002 has been reported to inhibit mTOR at 30 μm (Brunn et al., 1996); therefore, it is possible that the inhibition observed in 30 μmLY294002 resulted from the inhibition of both PI-3K and mTOR. Wortmannin at 10 nm, a concentration that has been reported to inhibit PI-3K specifically (Okada et al., 1994a), also caused a significant reduction in the level of S-phase entry induced by rhGGF2 (Fig. 3, bottom).

Fig. 3.

Inhibition of the enzymatic activity of PI-3K effectively blocked S-phase entry. A, A differential interference contrast micrograph showing many black BrdU-labeled nuclei that entered S-phase in a piece of utricular epithelium during 72 hr in culture with rhGGF2. B, Only one black BrdU-labeled nucleus was visible in this piece of epithelium that was treated with the PI-3K inhibitor LY294002 at 30 μm in the presence of rhGGF2. The treatment with LY294002 at 30 μm resulted in a pronounced qualitative reduction in the amount of S-phase entry that occurred in the presence of rhGGF2, reducing S-phase entry to levels below those observed in control cultures. C, Quantitative measures of BrdU labeling that resulted from the inhibition of rhGGF2-induced S-phase entry by LY294002 (LY) at 1, 10, and 30 μm and by 10 nm wortmannin (Wortm). Each bar represents data from 21–37 pieces of epithelium. Scale bars, 100 μm.

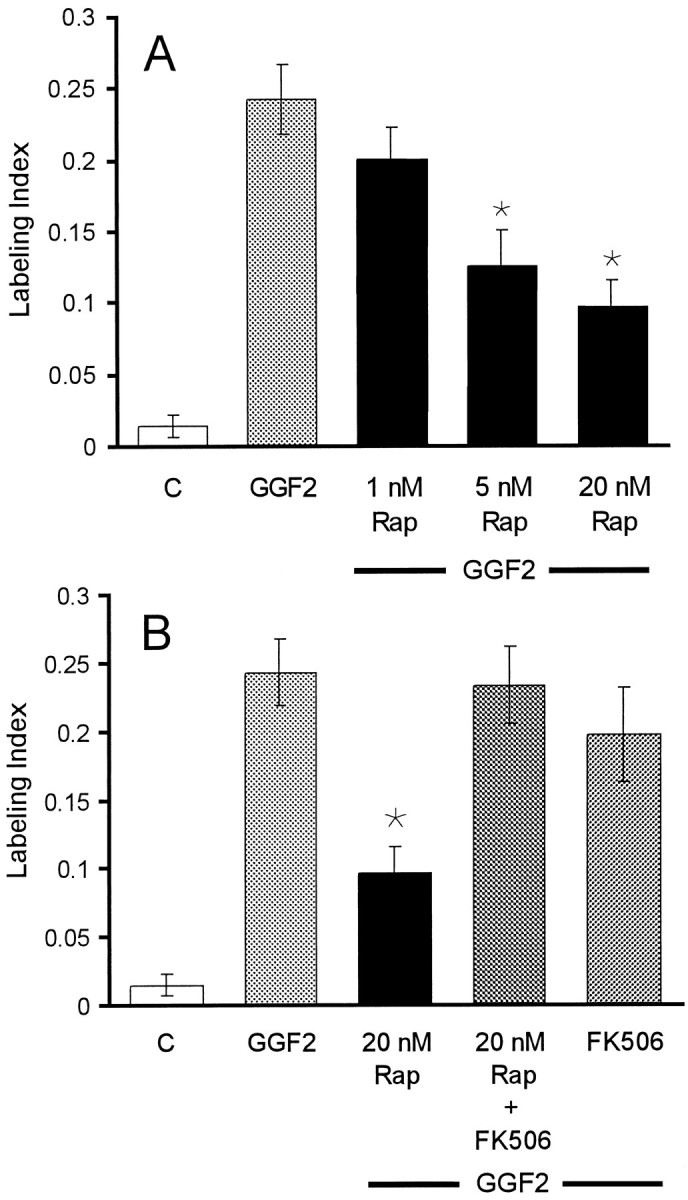

Incubation of sensory epithelia with rhGGF2 and rapamycin resulted in a dose-dependent inhibition of S-phase entry compared with the level induced in rhGGF2 alone. At 20 nm, rapamycin reduced the level of S-phase entry by ∼60% (p < 0.05) (Fig. 4A). The specificity of the inhibition achieved with rapamycin in this system was confirmed by culturing epithelia in medium containing rhGGF2 together with rapamycin and an excess of FK506, a structurally related drug that competes with rapamycin for the same binding site on FKBP12 (Abraham et al., 1996). The presence of FK506 blocked the inhibition observed with rapamycin (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Specific inhibition of mTOR reduced the incidence of S-phase entry induced by rhGGF2. A, A histogram of the level of BrdU labeling in epithelia that were treated with rapamycin (Rap) at 1, 5, and 20 nm in the presence of rhGGF2. B, The inhibitory effect of 20 nm rapamycin on S-phase entry was reversed by FK506, which competes with rapamycin for the same binding site of the immunophilin FKBP12. FK506 was added 1 hr before rapamycin, rhGGF2, and BrdU. When tested together with rhGGF2, FK506 did not change the level of S-phase entry significantly from the level induced by rhGGF2 alone. Each bar represents data from 20 to 44 pieces of epithelium.

The role of PKCs

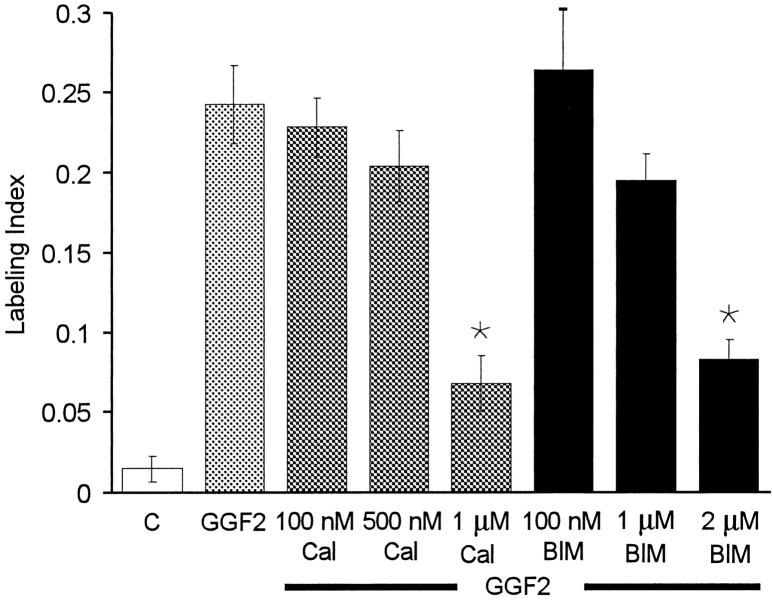

To determine whether PKCs are involved in the rhGGF2-mediated cell proliferation in utricular epithelia, we treated cultures with rhGGF2 in the presence of calphostin C, a specific inhibitor that binds to the regulatory domain of diacylglycerol (DAG)-dependent PKCs (IC50, 50 nm). Calphostin C at 100 nm, a concentration that has been reported to inhibit classical PKCs (cPKCs), did not inhibit rhGGF2-induced proliferation (Fig. 5). At 500 nm, a concentration reported to inhibit 50% of the activity of two novel PKC (nPKC) isoforms (δ and ε), the inhibitor induced a small but not significant decrease in the mean level of S-phase entry. At 1 μm, calphostin C reduced the level of S-phase entry by 72% from the level in cultures supplemented with rhGGF2 alone (p < 0.05).

Fig. 5.

Inhibition of the enzymatic activity of PKCs reduced the incidence of S-phase entry induced by rhGGF2. The PKC inhibitor calphostin C (Cal) at 0.1, 0.5, and 1 μm in the presence of rhGGF2 reduced S-phase entry by 70% compared with the level induced in the presence of rhGGF2 alone. The PKC inhibitor BIM at 0.1, 1, and 2 μm in the presence of rhGGF2 also produced dose-dependent reductions in S-phase entry compared with the level induced in rhGGF2 alone. Each bar in Figures5-8 represents data from 20 to 37 pieces of epithelium.

Bisindolylmaleimide I (BIM), an inhibitor that competitively binds to the ATP-binding site of PKCs (IC50, 10 nm), was used to provide an independent assessment of the role of PKCs in pathways that trigger rhGGF2-induced proliferation. At 100 nm, BIM did not inhibit rhGGF2-induced proliferation, but treatments with BIM at 1 and 2 μm resulted in mean levels of S-phase entry that decreased in a dose-dependent manner (Fig.5). At 2 μm, BIM reduced the level of rhGGF2-induced S-phase entry by ∼66% (p < 0.05).

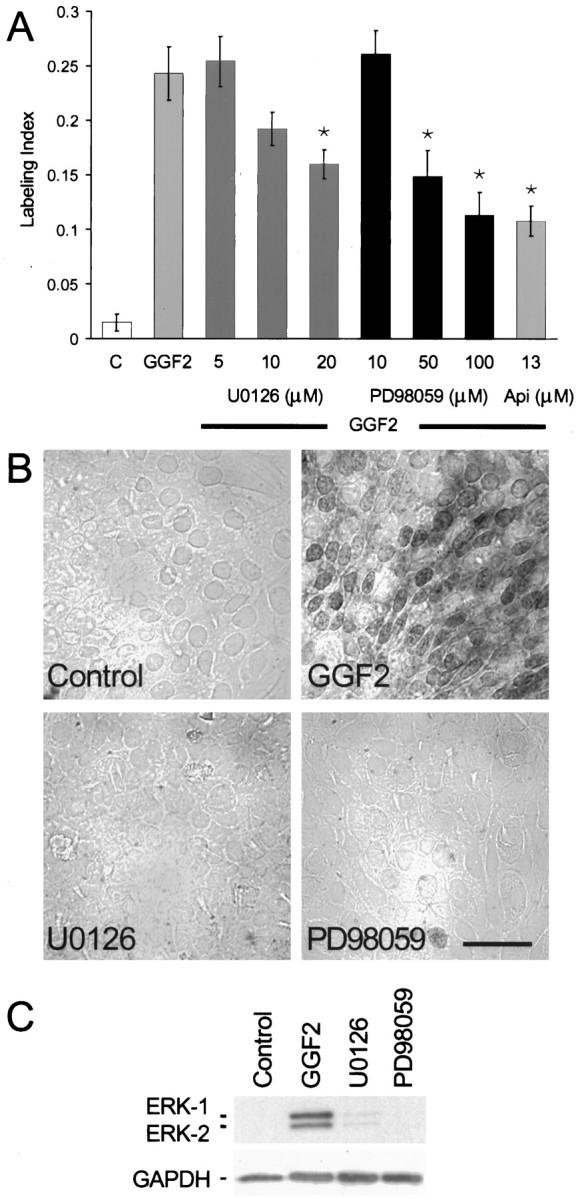

The role of MAP kinase

To assess the role of the ERK–MAPK pathway in the cell proliferation induced by rhGGF2, we used U0126, an inhibitor of MAPK–ERK kinase 1 (MEK1) and MEK2 (IC50values of 72 and 58 nm, respectively). At 20 μm, U0126 reduced the level of rhGGF2-induced S-phase entry by 34% (p < 0.05) (Fig.6A); lower concentrations were less effective.

Fig. 6.

Inhibitors of the ERK–MAPK cascade resulted in moderate reductions in the level of S-phase entry induced by rhGGF2.A, U0126 at 5 and 10 μm did not significantly reduce the level of S-phase entry induced by rhGGF2, but 20 μm reduced the response by 34% (p < 0.05). The MEK1 inhibitor PD98059 at 10, 50, and 100 μm produced a dose-dependent reduction of rhGGF2-induced S-phase entry. The ERK–MAPK inhibitor apigenin (Api) at 13 μm produced approximately the same level of reduction observed for PD98059 at 100 μmwhen tested in the presence of rhGGF2. B, Immunocytochemical analysis with an antibody recognizing activated ERK-1 and ERK-2 showed inhibition of phosphorylated forms of ERK-1 and ERK-2 in the presence of U0126 and PD98059. When pieces of utricular epithelium were treated with 20 μm U0126 or 100 μm PD98059 in the presence of rhGGF2 and then processed for immunocytochemistry, levels of phosphorylated ERK-1 or ERK-2 were virtually undetectable, similar to the control cultures. By comparison, pieces treated for 1 hr with rhGGF2 exhibited strong cytoplasmic and nuclear staining for the phosphorylated forms of ERK-1 and ERK-2. C, Immunoblot analysis of pieces of sensory epithelium that were treated with U0126 or PD98059. Phosphorylated forms of ERK-1 and ERK-2 were readily detected in samples treated with rhGGF2 (lane 2) but were nearly undetectable in samples treated with rhGGF2 in the presence of 20 μm U0126 (lane 3) or 100 μm PD98059 (lane 4) or in control cultures (lane 1). Scale bar, 50 μm.

Other pieces of epithelium were incubated with the MEK1 inhibitor PD98059 (IC50, 5–10 μm) to provide an independent assessment of the role of the ERK–MAPK pathway in the rhGGF2 response. PD98059 reduced the rhGGF2-induced S-phase entry by 39% at 50 μm and by 53% at 100 μm(p < 0.05) (Fig. 6A). Treatment with 13 μm apigenin, another inhibitor of the ERK–MAPK pathway, resulted in approximately the same level of inhibition observed with PD98059 at 100 μm (56%; p < 0.05).

To determine whether U0126 and PD98059 were effectively inhibiting the activation of the ERK–MAPK pathway in this culture system, we used a phosphospecific antibody to localize the activated (phosphorylated) forms of ERK-1 and ERK-2. Figure 6B shows immunostaining in control cultures and in cultures maintained in media containing rhGGF2 alone or rhGGF2 in combination with the U0126 or PD98059. The eight cultures that were maintained with rhGGF2 alone exhibited strong staining for the phosphorylated forms of ERK-1 and ERK-2 in both the cytoplasmic and nuclear regions of many cells. In contrast, there was virtually no staining for phosphorylated ERK-1 and ERK-2 in the eight cultures that were maintained in the same level of rhGGF2, but with 20 μm U0126, in the eight cultures that were maintained in rhGGF2 with 100 μm PD98059, or in the eight cultures that were maintained in the control medium.

To further assess the possibility for incomplete inhibition of the ERK–MAPK pathway, cultures were maintained with either rhGGF2 alone, rhGGF2 together with U0126, rhGGF2 together with PD98059, or in control medium; next, the cells were harvested for SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis for the level of ERK-1 and ERK-2 activation. Samples from 48–52 cultured pieces of epithelium per condition yielded two replicate immunoblots that showed that 96% of the phosphorylation of ERK-1 and 95% of the phosphorylation of ERK-2 was inhibited by 20 μm U0126 and that 96% and 92% of the phosphorylation, respectively, was inhibited by 100 μm PD98059 when cultures were maintained in those inhibitors together with rhGGF2 (Fig.6C).

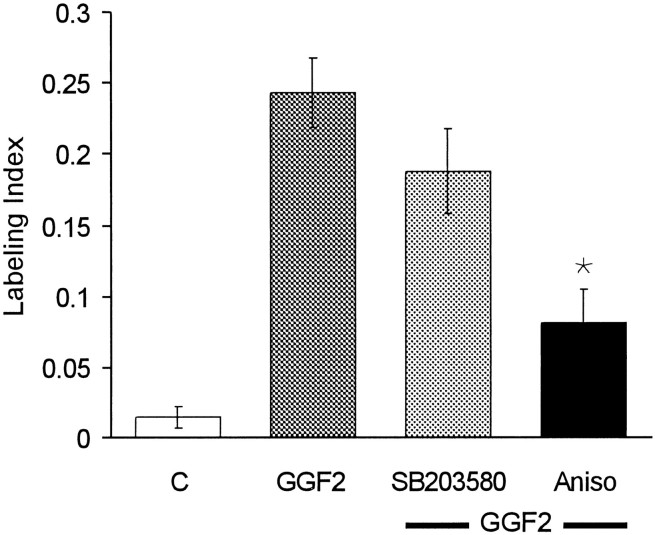

Another family of MAP kinases includes p38-MAPK and the c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNKs), which are involved in stress-activated responses. Treatment with 10 μm SB203580, a specific inhibitor of p38-MAPK (IC50, 600 nm), reduced the mean level of rhGGF2-induced S-phase entry, but the effect was not statistically significant in the 20 pieces of epithelium tested (Fig. 7). JNKs can be activated by the antibiotic anisomycin. Treatment with 10 ng/ml anisomycin for 72 hr reduced S-phase entry in the presence of rhGGF2 by 67% (Fig. 7; p < 0.05).

Fig. 7.

Inhibition of p38-MAPK and activation of JNKs were tested for effects on the level of S-phase entry that could be induced by rhGGF2. In the presence of rhGGF2, treatments with the p38-MAPK inhibitor SB203580 at 10 μm resulted in a reduced average incidence of S-phase labeling, but this effect was not significant when compared with the level of entry obtained with rhGGF2 alone. In contrast, treatments with 10 ng/ml anisomycin (Aniso), an activator of JNKs, significantly reduced the level of S-phase entry in the presence of rhGGF2.

Direct pharmacological stimulation of S-phase entry

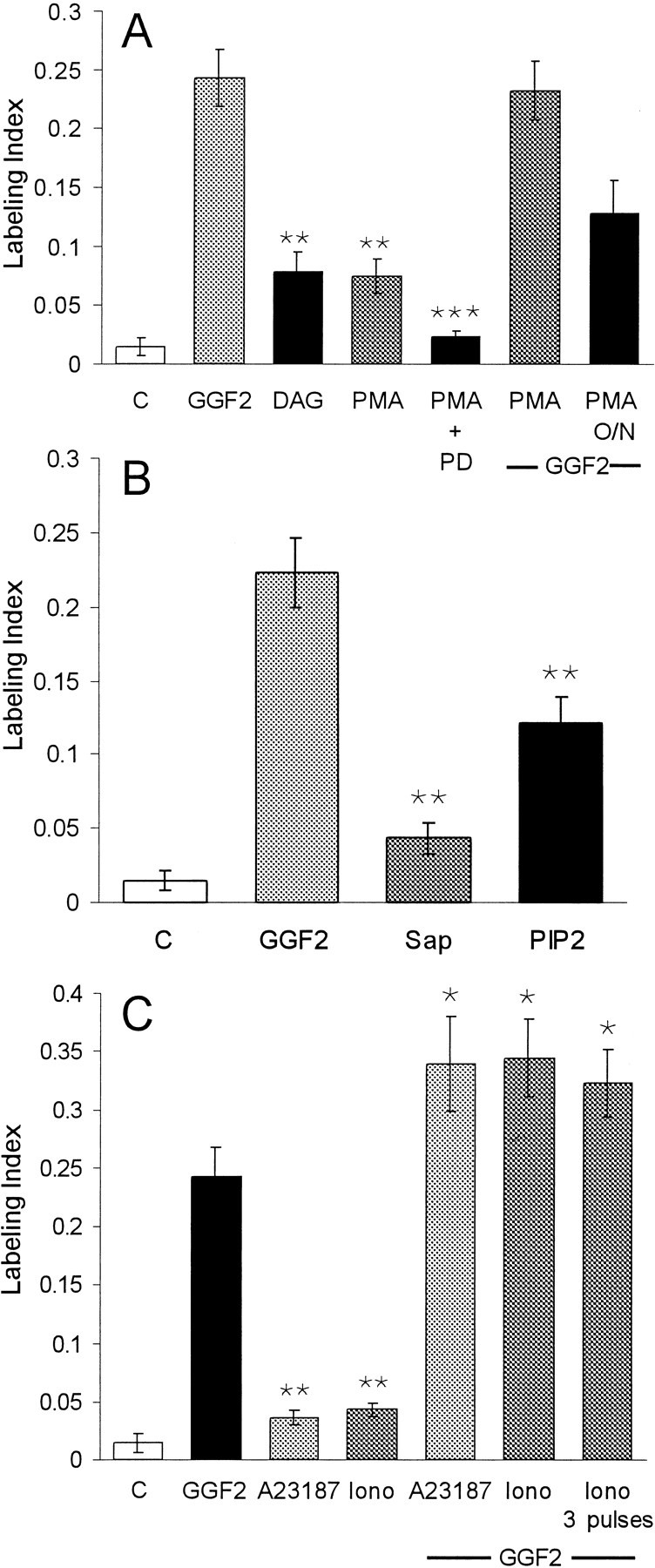

Epithelia were treated with the physiological PKC activator DAG and the phorbol ester PMA to determine whether activation of PKCs would stimulate S-phase entry directly in the absence of rhGGF2. When epithelia were treated with 10 μm DAG for just 15 min and subsequently maintained in the standard medium for 72 hr, S-phase entry was more than five times the level observed in control epithelia cultured in the same medium without pretreatment (p < 0.05) (Fig.8A). A 15 min treatment with 5 pm PMA also resulted in a fivefold increase in S-phase entry (p < 0.05) (Fig.8A). When the epithelia were preincubated with the MEK1 inhibitor PD98059 at 50 μm for 1 hr before treatment with 5 pm PMA, the PMA-induced S-phase entry was reduced significantly (Fig. 8A). Epithelia treated for 15 min with PMA and then with rhGGF2 responded with a mean level of S-phase entry that was nearly the same as that observed with rhGGF2 alone (Fig. 8). Downregulation of PKCs by a 16 hr treatment with 5 pm PMA caused a partial inhibition of the rhGGF2-induced S-phase entry, consistent with a role for PKCs in the induction of that proliferation (Fig. 8A).

Fig. 8.

Brief treatments with activators for PKCs, PKB–Akt, and increased intracellular calcium induced S-phase entry in utricular epithelia. A, When pieces of sensory epithelium were treated for 15 min with either 10 μm DAG or 5 pm PMA and then cultured in the standard medium for 72 hr, S-phase entry increased to approximately five times the level seen in control cultures. To inhibit signaling via the ERK–MAPK pathway, other pieces of epithelium were pretreated for 60 min with 50 μm PD98059 (PD) before the 15 min treatment with PMA. The medium was then changed to one containing 50 μm PD98059 and BrdU for the remainder of the 72 hr culture period. Inhibition of the ERK–MAPK pathway significantly reduced the level of S-phase entry induced by the PMA treatment. Other pieces of epithelium were treated with 5 pm PMA for 15 min and subse- quently changed to a medium that contained rhGGF2 for 72 hr. The sequential treatment with PMA and rhGGF2 did not increase the level of S-phase entry over that induced by rhGGF2 alone. To downregulate PKC activity, other cultures were incubated with 5 pm PMA for 16 hr [PMA overnight (O/N)] before rhGGF2 was added for the remaining 56 hr. This resulted in a 32% decrease in the level of labeling compared with that expected for 56 hr in rhGGF2 alone.B, Pieces of sensory epithelium were permeabilized by a 1 min treatment with 10 ng/ml saponin (Sap). Next, half of the pieces were changed to standard medium and cultured for 72 hr. The other half were changed to 2 μm PI-3,4-P2 (PIP2) for 15 min and then changed into standard medium and cultured for 72 hr. Compared with controls, the brief treatment with PI-3,4-P2 resulted in a ninefold increase in S-phase entry measured over the subsequent 72 hr culture period in the presence of BrdU. This was ∼50% of the level that was induced during 72 hr in the continuous presence of rhGGF2. C, When pieces of sensory epithelium were treated with either A23187 or ionomycin (Iono) at 100 nm for just 15 min and then cultured for 72 hr in the standard medium, a level of S-phase entry was induced that was 2.4 and 2.9 times the level that was measured in controls. When other pieces of epithelium were treated with A23187 for 15 min and then cultured for 72 hr with rhGGF2 and BrdU, a level of S-phase entry was observed that was 139% of the level induced by rhGGF2 (142% in the case of ionomycin). Treatments with three 15 min pulses of ionomycin (1 pulse per hour) followed by 72 hr in culture in the presence of rhGGF2 and BrdU did not produce an increase over the level measured for a single 15 min pulse. **Significance compared with control cultures (p < 0.05); ***Significance compared with cultures treated for 15 min with PMA alone (p < 0.05).

PKCs and Akt [also known as protein kinase B (PKB)] are important downstream targets of PI-3K. The major lipid phosphorylation products of PI-3K are phosphatidylinositol-3,4-biphosphate (PI-3,4-P2) and phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-triphosphate (PI-3,4,5-P3), which activate PKCs and Akt–PKB. Epithelia were treated with synthetic PI-3,4-P2 to assess signaling downstream from PI-3K after they were permeabilized with saponin at 10 ng/ml for 1 min to allow the phospholipid to cross the cell membrane. The saponin treatment increased the mean level of S-phase entry by ∼2.5-fold compared with control cultures, but that difference was not significant (p = 0.07), whereas permeabilization followed by a 15 min treatment with PI-3,4-P2 at 2 μmresulted in an eightfold increase in S-phase entry during the subsequent 72 hr period of culture in the standard medium compared with control (p < 0.05) (Fig. 8B). The increase was approximately threefold when compared with the level of S-phase entry in the saponin-treated controls (p < 0.05).

Incubation of the epithelia with the calcium ionophore A23187 at 100 nm for 15 min resulted in 2.4 times the level of S-phase entry that occurred in the controls (p < 0.05, Fig. 8C). A 15 min treatment with the calcium ionophore ionomycin at 100 nm raised S-phase entry to approximately three times the control level (p< 0.05). When epithelia were treated with either A23187 or ionomycin at 100 nm for 15 min and the medium was replaced by the standard medium containing rhGGF2, S-phase entry was increased significantly over that observed after rhGGF2 alone. Treatment with three 15 min pulses of ionomycin at 100 nm (one pulse per hour) followed by rhGGF2 did not significantly increase S-phase entry beyond that induced by a single 15 min ionomycin pulse that was followed by rhGGF2 (Fig. 8C).

DISCUSSION

PI-3K

The results show that inhibitors of PI-3K most effectively block signaling that is required for rhGGF2 induction of S-phase entry and cell proliferation in vestibular epithelia cultured from the ears of neonatal rats. PI-3K is a heterodimeric enzyme that phosphorylates phosphoinositides at the D3 position of the inositol ring to produce phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate, PI-3,4-P2, and PI-3,4,5-P3 (for review, see Carpenter and Cantley, 1996). The strong inhibition of the rhGGF2-mediated S-phase entry that occurred in epithelia treated with a low concentration of wortmannin and different concentrations of LY294002 suggests that PI-3K cascades play pivotal roles in triggering cell proliferation in utricular sensory epithelia. LY294002 is a synthetic compound that is much more specific for PI-3K inhibition than the fungal metabolite wortmannin. The reduction in S-phase entry in the presence of 30 μm LY294002 together with rhGGF2 was particularly pronounced and lower than in control cultures.

mTOR and p70/p85 S6Ks

Inhibition of the kinase activities of mTOR by rapamycin also led to a significant reduction in the incidence of rhGGF2-mediated S-phase entry. Rapamycin inhibition of mTOR blocks downstream activation of the p70/p85 isoforms of S6 kinase (p70/p85 S6Ks) (Brown et al., 1995;Abraham and Wiederrecht, 1996). Activated S6K induces an increase in protein synthesis that is required for cells to make the transition from G0 to G1 (for review, see Pullen and Thomas, 1997). The p70/p85 S6K isoforms are generated from alternative translation of the same transcript and differ in an N-terminal extension, which constitutively targets p85 S6K to the nucleus (Reinhard et al., 1992). The p85 isoform of S6K is much less abundant than the p70 isoform, and its accumulation in the nucleus has been shown to trigger G1 progression (Reinhard et al., 1994). In our experiments, rapamycin produced a dose-dependent inhibition of rhGGF2-induced S-phase entry, which suggests that mTOR participates in the mitogenic signaling pathway in supporting cells. In established pathways, mTOR and p70/p85 S6Ks are downstream from PI-3K (Weng et al., 1995; Brunn et al., 1996; McIlroy et al., 1997). One hypothesis is that the activation of PI-3K could lead, via PKC and/or Akt–PKB, to the activation of mTOR and p70/p85 S6Ks to trigger the proliferation of supporting cells.

ErbB receptors

Inhibition of the kinase activity of the ErbB2 receptor led to a significant reduction in the incidence of S-phase entry induced by rhGGF2. The EGF receptor (EGFR)/ErbB family includes the receptor tyrosine kinases EGFR (also known as ErbB1), ErbB2, ErbB3, and ErbB4. Signaling requires the formation of homodimeric or heterodimeric complexes of these receptors (Alroy and Yarden, 1997). ErbB2 does not have ligand-binding capacity, but it is the preferred dimerization partner for the other members (Graus-Porta et al., 1997). When epithelia were treated with rhGGF2 and the tyrphostin AG825, a specific ErbB2 kinase inhibitor, the level of S-phase entry was reduced by 60%. We hypothesize that the proliferation induced by rhGGF2 is initiated in part through signals that arise when ErbB2 dimerizes with either ErbB3 or ErbB4. The ErbB3 receptor can associate with the p85 regulatory subunit of PI-3K (Fedi et al., 1994; Kita et al., 1994; Prigent and Gullick, 1994). RT-PCR and immunohistochemistry have shown that ErbB2, ErbB3, and ErbB4 are all expressed in sensory epithelia from the utricles of neonatal rats (J. Corwin, Q. Shi, and T. Karaoli, unpublished observations).

PKC isoforms

PKCs are a large family of serine–threonine kinases composed of at least 11 isotypes that are classified into three groups (Nishizuka, 1995). cPKCs are activated by calcium and DAG, nPKCs are activated by DAG, and atypical PKCs (aPKCs) are not activated by calcium, DAG, or phorbol esters. BIM produced a modest but not significant mean reduction in the rhGGF2 response at 1 μm, a concentration that inhibits only cPKCs (Martiny-Baron et al., 1993). However 2 μm BIM, a concentration that blocks both cPKCs and nPKCs, significantly attenuated rhGGF2-induced S-phase entry. The involvement of nPKCs is also indicated by the strong inhibition in 1 μm calphostin C, a concentration reported to inhibit cPKCs and nPKCs (Seynaeve et al., 1994). Calphostin C used at concentrations reported to block cPKCs specifically did not significantly inhibit the rhGGF2-induced S-phase entry (Tamaoki et al., 1990; Seynaeve et al., 1994).

Treatments with DAG or PMA in the absence of rhGGF2 resulted in a fivefold increase in S-phase entry compared with controls, providing additional evidence for the involvement of cPKCs or nPKCs. The MEK1 inhibitor PD98059 blocked the increase in S-phase entry that resulted from the direct activation of PKC by PMA (Fig. 8). This result suggests that signals downstream from PMA-activated PKCs are transmitted through the ERK–MAPK cascade, as has been reported in several other cell types (Cai et al., 1997; Schonwasser et al., 1998).

Prolonged treatment with the phorbol ester PMA can result in the degradation of PKCs (Ueda et al., 1996; Cai et al., 1997; Soltoff, 1998). Treatment of sensory epithelia for 16 hr with PMA resulted in partial inhibition of rhGGF2-induced S-phase entry (Fig. 8), as expected for a signaling pathway that depends in part on activation of PKCs. Combined stimulation with PMA and rhGGF2 did not produce an additive effect on S-phase entry, which suggests that DAG-responsive cPKCs or nPKCs may already have been activated in response to rhGGF2.

The observation that a 15 min treatment with PI-3,4-P2 significantly increases S-phase entry in the absence of rhGGF2 provides further evidence for a role for PKCs in the pathways that lead to proliferation of supporting cells. PI-3,4-P2 and PI-3,4,5-P3 are products of PI-3K that can activate certain nPKCs and aPKCs (for review, see Toker, 1998;Rameh and Cantley, 1999). PI-3,4-P2 can also activate Akt–PKB (Franke et al., 1997; Klippel et al., 1997), which has been reported to induce the activation of p70 S6K (Kohn et al., 1998).

The MAP kinase cascades

The MAPK family includes ERK-1 and ERK-2 (also known as p42/44 MAPK), JNKs, and p38-MAPK. The level of rhGGF2-induced S-phase entry was reduced by 34% by 20 μm U0126, a MEK1 and MEK2 inhibitor, whereas 50 and 100 μm of the MEK1 inhibitor PD98059 produced 39% and 53% reductions. These levels of S-phase inhibition are noticeably less than have been reported from studies of rat hepatocytes and mouse endothelial cells, in which 50 μm PD98059 resulted in ∼80% inhibition of EGF-induced and serum-induced proliferation (Talarmin et al., 1999; Vinals et al., 1999). Both immunocytochemistry with a phosphospecific antibody and immunoblotting confirmed that 20 μm U0126 and 100 μm PD98059 inhibited 92–96% of the rhGGF2-induced phosphorylation of ERK-1 and ERK-2 in our cultures. A similar level of S-phase reduction occurred with apigenin, which has been reported to inhibit ERK-2 specifically. Although >92% of the phosphorylation of ERK-1 and ERK-2 was inhibited, 47% of cells continued to enter S-phase in the presence of rhGGF2, indicating that activation of the ERK–MAPK pathway is not critical for the proliferative responses of supporting cells. In other cell types, the effectiveness of the ERK–MAPK cascade can depend on activation of PI-3K (Duckworth and Cantley, 1997), and in some cells proliferative signaling depends on parallel activation of a PI-3K cascade and a ERK–MAPK cascade (Wennstrom and Downward, 1999).

Activation of the JNKs by anisomycin also resulted in a strong and significant inhibition of the rhGGF2 effect. A balance between the JNK and the ERK–MAPK pathways may play a role in determining whether cells in the vestibular sensory epithelium proliferate or die by apoptosis, as has been shown in other systems (Xia et al., 1995), but potential contributions of cell death have not been assessed here.

Calcium

Increased levels of intracellular Ca2+ have been reported to induce phosphorylation of the EGF receptor (Rosen and Greenberg, 1996), and treatments with calcium ionophores have been shown to activate PKCs and the ERK–MAPK pathway (Lev et al., 1995; Daulhac et al., 1997;Romanelli and van de Werve, 1997). Other studies have shown that an ionomycin-induced increase in intracellular calcium levels is sufficient for full activation of p70 S6K (Graves et al., 1997; Conus et al., 1998). In our experiments, 15 min exposures to different calcium ionophores increased S-phase entry significantly in the absence of rhGGF2, and combined treatments with rhGGF2 and each ionophore produced additive effects. The results are consistent with the possibility that the signaling pathways activated by intracellular calcium intersect with those that are also activated in response to rhGGF2, and may also function in parallel.

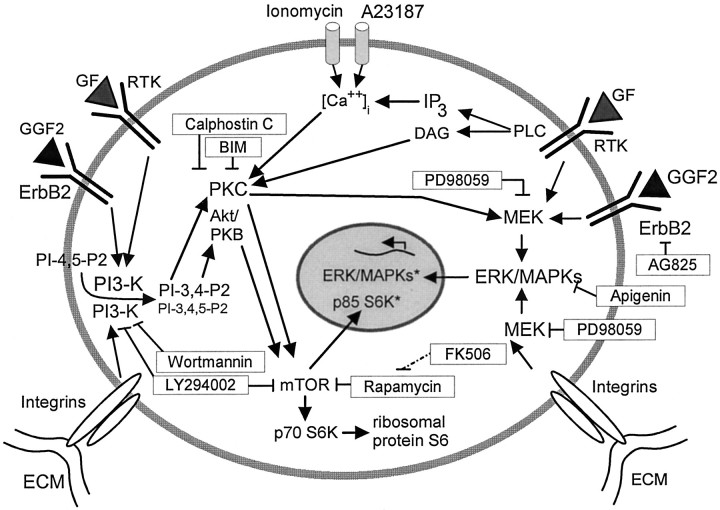

In summary, this investigation has shown that intracellular signals that influence the triggering of S-phase entry in vestibular epithelia from neonatal rodents are components of two established cascades (Fig.9). One cascade appears to involve activation of PI-3K, PKCs or Akt–PKB, mTOR, and presumably S6Ks. This cascade is critical for S-phase entry of mammalian supporting cells and showed the greatest sensitivity to inhibitors. The other pathway involves PKCs and the ERK–MAPK cascade. That pathway appears to have a supporting or permissive role that is less critical for the proliferation of cells in mammalian vestibular sensory epithelia. Future investigations should lead to the identification of the specific isoforms of the kinases that function in the proliferation cascades in these cells. The identification of those isoforms ultimately holds the potential to define drug targets suitable for modulation of progenitor cell proliferation and the capacity for regenerative replacement of sensory hair cells in mammalian ears.

Fig. 9.

A schematic model of intracellular signal components that control S-phase entry in vestibular epithelia from neonatal mammals. Inhibitors and activators that were used to identify the elements in the signaling cascades are shown inboxes. Binding of GGF2 and other growth factors (GF) to receptor tyrosine kinases (RTK, ErbB2) leads to activation in both the PI-3K cascade and the MAPK cascade. Activated ERK–MAPKs can translocate to the nucleus, resulting in changes in gene expression. Active PI-3K leads to the production of PI-3,4-P2 and PI-3,4,5-P3, which can activate PKCs and Akt–PKB. Certain activated isoforms of PKC and Akt–PKB phosphorylate and activate mTOR, which leads to the activation of p70/85 S6Ks. When p70 S6K is active, it phosphorylates and activates the S6 ribosomal protein, which is required for the synthesis of proteins involved in S-phase entry. Activated p85 S6K is translocated to the nucleus and mediates cell-cycle progression. Phospholipase C (PLC) induces the production of DAG and IP3. DAG can activate certain PKCs, which can activate the MAPK pathway. The production of IP3 increases the release of intracellular calcium ([Ca2+]i), which can also lead to the activation of PKCs. The anchorage-dependent proliferative response depends on the level of signals from growth factor receptors as well as anchorage of the cell to the extracellular matrix (ECM) via integrins. Bindings of integrins to specific components of the ECM can lead to the activation of the PI-3K cascade and the MAPK cascade.GGF2, Glial growth factor; ErbB2, receptor tyrosine kinase of the ErbB family; MEK, mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase; p70 S6K, the 70 kDa S6 protein kinase; p85 S6K, the 85 kDa S6 protein kinase; Akt–PKB, protein kinase B.

Footnotes

This work was supported by R01-DC00200 from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. We thank Sherri Smith, Themis Karaoli, and Larry Phillips for their technical help as well as David Brautigan, Mark Witte, Kambiz Karimi, David Lenzi, and Veena Vasandani for helpful comments and critical reading of this manuscript. We also thank Julie Sando for valuable suggestions, John Lawrence and Greg Brunn for their suggestions and the generous gift of FK506, and Mark Marchionni and Cambridge NeuroScience Inc. for the generous gift of rhGGF2.

Correspondence should be addressed to Mireille Montcouquiol, Departments of Otolaryngology and Neuroscience, University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville, VA 22908. E-mail:mm7vy@virginia.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abraham RT, Wiederrecht GJ. Immunopharmacology of rapamycin. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:483–510. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alessi DR, Cuenda A, Cohen P, Dudley DT, Saltiel AR. PD 098059 is a specific inhibitor of the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:27489–27494. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.46.27489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alroy I, Yarden Y. The ErbB signaling network in embryogenesis and oncogenesis: signal diversification through combinatorial ligand-receptor interactions. FEBS Lett. 1997;410:83–86. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00412-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown EJ, Albers MW, Shin TB, Ichikawa K, Keith CT, Lane WS, Schreiber SL. A mammalian protein targeted by G1-arresting rapamycin-receptor complex. Nature. 1994;369:756–758. doi: 10.1038/369756a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown EJ, Beal PA, Keith CT, Chen J, Shin TB, Schreiber SL. Control of p70 s6 kinase by kinase activity of FRAP in vivo. Nature. 1995;377:441–446. doi: 10.1038/377441a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brunn GJ, Williams J, Sabers C, Wiederrecht G, Lawrence JC, Abraham RT. Direct inhibition of the signaling functions of the mammalian target of rapamycin by the phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibitors, wortmannin and LY294002. EMBO J. 1996;15:5256–5267. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cai H, Smola U, Wixler V, Eisenmann-Tappe I, Diaz-Meco MT, Moscat J, Rapp U, Cooper GM. Role of diacylglycerol-regulated protein kinase C isotypes in growth factor activation of the Raf-1 protein kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:732–741. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.2.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cano E, Hazzalin CA, Mahadevan LC. Anisomycin-activated protein kinases p45 and p55 but not mitogen-activated protein kinases ERK-1 and -2 are implicated in the induction of c-fos and c-jun. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:7352–7362. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.11.7352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carpenter CL, Cantley LC. Phosphoinositide kinases. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1996;8:153–158. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(96)80060-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chung J, Kuo CJ, Crabtree GR, Blenis J. Rapamycin-FKBP specifically blocks growth-dependent activation of and signaling by the 70 kDa S6 protein kinases. Cell. 1992;69:1227–1236. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90643-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conus NM, Hemmings BA, Pearson RB. Differential regulation by calcium reveals distinct signaling requirement for the activation of Akt and p70S6K. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:4776–4782. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.8.4776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corwin JT, Oberholtzer JC. Fish n' chicks: model recipes for hair-cell regeneration? Neuron. 1997;19:951–954. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80386-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cuenda A, Rouse J, Doza YN, Meier R, Cohen P, Gallagher TF, Young PR, Lee JC. SB 203580 is a specific inhibitor of a MAP kinase homologue which is stimulated by cellular stresses and interleukin-1. FEBS Lett. 1995;364:229–233. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00357-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daulhac L, Kowalski-Chauvel A, Pradayrol L, Vaysse N, Seva C. Ca2+ and protein kinase C-dependent mechanisms involved in gastrin-induced Shc/Grb2 complex formation and P44-mitogen-activated protein kinase activation. Biochem J. 1997;325:383–389. doi: 10.1042/bj3250383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duckworth BC, Cantley LC. Conditional inhibition of the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade by wortmannin: dependence on signal strength. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:27665–27670. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.44.27665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dudley DT, Pang L, Decker SJ, Bridges AJ, Saltiel AR. A synthetic inhibitor of the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7686–7689. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Favata MF, Horiuchi KY, Manos EJ, Daulerio AJ, Stradley DA, Feeser WS, Van Dyk DE, Pitts WJ, Earl RA, Hobbs F, Copeland RA, Magolda RL, Scherle PA, Trzaskos JM. Identification of a novel inhibitor of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:18623–18632. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.29.18623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fedi P, Pierce JH, di Fiore PP, Kraus MH. Efficient coupling with phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, but not phospholipase Cγ or GTPase-activating protein, distinguishes ErbB3 signaling from that of other ErbB/EGFR family members. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:492–500. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.1.492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Forge A, Li L, Corwin JT, Nevill G. Ultrastructural evidence for hair cell regeneration in the mammalian inner ear. Science. 1993;259:1616–1619. doi: 10.1126/science.8456284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Franke TF, Kaplan DR, Cantley LC, Toker A. Direct regulation of the Akt proto-oncogene product by phosphatidylinositol-3,4-bisphosphate. Science. 1997;275:665–668. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5300.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Graus-Porta D, Beerli RR, Daly JM, Hynes NE. ErbB-2, the preferred heterodimerization partner of all ErbB receptors, is a mediator of lateral signaling. EMBO J. 1997;16:1647–1655. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.7.1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Graves LM, He Y, Lambert J, Hunter D, Li X, Earp HS. An intracellular calcium signal activates p70 but not p90 ribosomal S6 kinase in liver epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:1920–1928. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.3.1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kita YA, Barff J, Luo Y, Wen D, Brankow D, Hu S, Liu N, Prigent SA, Gullick WJ, Nicolson M. NDF/heregulin stimulates the phosphorylation of Her3/erbB3. FEBS Lett. 1994;349:139–143. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00644-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klippel A, Kavanaugh WM, Pot D. A specific product of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase directly activates the protein kinase Akt through its pleckstrin homology domain. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:338–344. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.1.338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kohn AD, Barthel A, Kovacina KS, Boge A, Wallach B, Summers SA, Birnbaum MJ, Scott PH, Lawrence JC, Jr, Roth RA. Construction and characterization of a conditionally active version of the serine/threonine kinase Akt. J Biol Chem. 1998;19:11937–11943. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.19.11937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuntz AL, Oesterle EC. Transforming growth factor α with insulin stimulates cell proliferation in vivo in adult rat vestibular sensory epithelium. J Comp Neurol. 1998;399:413–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuo ML, Yang NC. Reversion of v-H-ras-transformed NIH 3T3 cells by apigenin through inhibiting mitogen-activated protein kinase and its downstream oncogenes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;212:767–775. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lambert PR. Inner ear hair cell regeneration in a mammal: identification of a triggering factor. Laryngoscope. 1994;104:701–718. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199406000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lev S, Moreno H, Martinez R, Canoll P, Peles E, Musacchio JM, Plowman GD, Rudy B, Schlessinger J. Protein tyrosine kinase PYK2 involved in Ca2+-induced regulation of ion channel and MAP kinase functions. Nature. 1995;376:737–745. doi: 10.1038/376737a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin TA, Kong X, Saltiel AR, Blackshear PJ, Lawrence JC., Jr Control of PHAS-I by insulin in 3T3–L1 adipocytes: synthesis, degradation, and phosphorylation by a rapamycin-sensitive and mitogen-activated protein kinase-independent pathway. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:18531–18538. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.31.18531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marchionni MA, Goodearl AD, Chen MS, Bermingham-McDonogh O, Kirk C, Hendricks M, Danehy F, Misumi D, Sudhalter J, Kobayashi K, Wroblewski D, Lynch C, Baldassare M, Hiles I, Davis JB, Hsuan JJ, Totty NF, Otsu M, McBurney RN, Waterfield MD, Stroobant P, Gwynne D. Glial growth factors are alternatively spliced erbB2 ligands expressed in the nervous system. Nature. 1993;362:312–318. doi: 10.1038/362312a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martiny-Baron G, Kazanietz MG, Mischak H, Blumberg PM, Kochs G, Hug H, Marme D, Schachtele CJ. Selective inhibition of protein kinase C isozymes by the indolocarbazole Go 6976. J Biol Chem. 1993;13:9194–9197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McIlroy J, Chen D, Wjasow C, Michaeli T, Backer JM. Specific activation of p85–p110 phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase stimulates DNA synthesis by ras- and p70 S6 kinase-dependent pathways. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:248–255. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.1.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nadol JB., Jr Hearing loss. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1092–1010. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199310073291507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Navaratnam DS, Su HS, Scott S-P, Oberholtzer C. Proliferation in the auditory receptor epithelium mediated by cyclic AMP-dependent signaling pathway. Nat Med. 1996;2:1136–1139. doi: 10.1038/nm1096-1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nishizuka Y. Protein kinase C and lipid signaling for sustained cellular responses. FASEB J. 1995;9:484–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Okada T, Sakuma L, Fukui Y, Hazeki O, Ui M. Blockage of chemotactic peptide-induced stimulation of neutrophils by wortmannin as a result of selective inhibition of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. J Biol Chem. 1994a;269:3563–3567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Okada T, Kawano Y, Sakakibara T, Hazeki O, Ui M. Essential role of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in insulin-induced glucose transport and antilipolysis in rat adipocytes: studies with a selective inhibitor wortmannin. J Biol Chem. 1994b;269:3568–3573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Osherov N, Gazit A, Gilon C, Levitzki A. Selective inhibition of the epidermal growth factor and HER2/neu receptors by tyrphostins. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:11134–11142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parrizas M, Saltiel AR, LeRoith D. Insulin-like growth factor 1 inhibits apoptosis using the phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:154–161. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.1.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prigent SA, Gullick WJ. Identification of c-erbB-3 binding sites for phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase and SHC using an EGF receptor/c-erbB-3 chimera. EMBO J. 1994;13:2831–2841. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06577.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pullen N, Thomas G. The modular phosphorylation and activation of p70S6k. FEBS Lett. 1997;410:78–82. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00323-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rameh LE, Cantley LC. The role of phosphoinositide 3-kinase lipid products in cell function. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:8347–8350. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.13.8347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reinhard C, Thomas G, Kozma SC. A single gene encodes two isoforms of the p70 S6 kinase: activation upon mitogenic stimulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:4052–4056. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.9.4052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reinhard C, Fernandez A, Lamb NJ, Thomas G. Nuclear localization of p85s6k: functional requirement for entry into S phase. EMBO J. 1994;13:1557–1565. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06418.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Riese DJ, II, Stern DF. Specificity within the EGF family/ErbB receptor family signaling network. Bioessays. 1998;20:41–48. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199801)20:1<41::AID-BIES7>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Romanelli A, van de Werve G. Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase in freshly isolated rat hepatocytes by both a calcium- and a protein kinase C-dependent pathway. Metab Clin Exp. 1997;46:548–555. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(97)90193-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rosen LB, Greenberg ME. Stimulation of growth factor receptor signal transduction by activation of voltage-sensitive calcium channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:1113–1118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.3.1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ruben RJ. Development of the inner ear of the mouse: a radioautographic study of terminal mitoses. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1967;220:1–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Saffer LD, Gu R, Corwin JT. An RT-PCR analysis of mRNA for growth factor receptors in damaged and control sensory epithelia of rat utricles. Hear Res. 1996;94:14–23. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(95)00228-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sanchez-Margalet V, Goldfine ID, Vlahos CJ, Sung CK. Role of phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase in insulin receptor signaling: studies with inhibitor, LY294002. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;204:446–452. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schonwasser DC, Marais RM, Marshall CJ, Parker PJ. Activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway by conventional, novel, and atypical protein kinase C isotypes. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:790–798. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.2.790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Seynaeve CM, Kazanietz MG, Blumberg PM, Sausville EA, Worland PJ. Differential inhibition of protein kinase C isozymes by UCN-01, a staurosporine analogue. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;45:1207–1214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Soltoff SP. Related adhesion focal tyrosine kinase and the epidermal growth factor receptor mediate the stimulation of mitogen-activated protein kinase by the G-protein-coupled P2Y2 receptor: phorbol ester or [Ca2+]i elevation can substitute for receptor activation. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:23110–23117. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.36.23110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Talarmin H, Rescan C, Cariou S, Glaise D, Zanninelli G, Bilodeau M, Loyer P, Guguen-Guillouzo C, Baffet G. The mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase cascade activation is a key signalling pathway involved in the regulation of G1 phase progression in proliferating hepatocytes. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;9:6003–6011. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.9.6003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tamaoki T, Takahashi I, Kobayashi E, Nakano H, Akinaga S, Suzuki K. Calphostin (UCN1028) and calphostin-related compounds, a new class of specific and potent inhibitors of protein kinase C. Adv Second Messenger Phosphoprotein Res. 1990;24:497–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Toker A. Signaling through protein kinase C. Front Biosci. 1998;3:1134–1147. doi: 10.2741/a350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Toker A, Meyer M, Reddy KK, Falck JR, Aneja R, Aneja S, Parra A, Burns DJ, Ballas LM, Cantley LC. Activation of protein kinase C family members by the novel polyphosphoinositides PtdIns-3,4-P2 and PtdIns-3,4,5-P3. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:32358–32367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Toullec D, Pianetti P, Coste H, Bellevergue P, Grand-Perret T, Ajakane M, Baudet V, Boissin P, Boursier E, Loriolle F. The bisindolylmaleimide GF 109203X is a potent and selective inhibitor of protein kinase C. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:15771–15781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ueda Y, Hirai Si, Osada Si, Suzuki A, Mizuno K, Ohno S. Protein kinase C activates the MEK-ERK pathway in a manner independent of Ras and dependent on Raf. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:23512–23519. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.38.23512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vinals F, Chambard JC, Pouyssegur J. p70 S6 kinase-mediated protein synthesis is a critical step for vascular endothelial cell proliferation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:26776–26823. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.38.26776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vlahos CJ, Matter WF, Hui KY, Brown RF. A specific inhibitor of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, 2-(4-morpholinyl)-8-phenyl-4H-1-benzopyran-4-one (LY294002). J Biol Chem. 1994;269:5241–5248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Warchol ME, Lambert PR, Goldstein BJ, Forge A, Corwin JT. Regenerative proliferation in inner ear sensory epithelia from adult guinea pigs and humans. Science. 1993;259:1619–1622. doi: 10.1126/science.8456285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Weng QP, Andrabi K, Klippel A, Kozlowski MT, Williams LT, Avruch J. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signals activation of p70 S6 kinase in situ through site-specific p70 phosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5744–5748. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wennstrom S, Downward J. Role of phosphoinositide 3-kinase in activation of ras and mitogen-activated protein kinase by epidermal growth factor. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:4279–4288. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.6.4279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Xia Z, Dickens M, Raingeaud J, Davis RJ, Greenberg ME. Opposing effects of ERK and JNK-p38 MAP kinases on apoptosis. Science. 1995;270:1326–1331. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5240.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yamashita H, Oesterle EC. Induction of cell proliferation in mammalian inner ear sensory epithelia by transforming growth factor α and epidermal growth factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:3152–3155. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yao R, Cooper GM. Growth factor-dependent survival of rodent fibroblasts requires phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase but is independent of pp70S6K activity. Oncogene. 1996;13:343–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zheng JL, Helbig C, Gao W-Q. Induction of cell proliferation by fibroblast and insulin-like growth factors in pure rat inner ear epithelial cell cultures. J Neurosci. 1997;17:216–226. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-01-00216.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]