Abstract

A novel factor, termed Humanin (HN), antagonizes against neurotoxicity by various types of familial Alzheimer's disease (AD) genes [V642I and K595N/M596L (NL) mutants of amyloid precursor protein (APP), M146L-presenilin (PS) 1, and N141I-PS2] and by Aβ1–43 with clear action specificity ineffective on neurotoxicity by polyglutamine repeat Q79 or superoxide dismutase 1 mutants. Here we report that HN can also inhibit neurotoxicity by other AD-relevant insults: other familial AD genes (A617G-APP, L648P-APP, A246E-PS1, L286V-PS1, C410Y-PS1, and H163R-PS1), APP stimulation by anti-APP antibody, and other Aβ peptides (Aβ1–42 and Aβ25–35). The action specificity was further indicated by the finding that HN could not suppress neurotoxicity by glutamate or prion fragment. Against the AD-relevant insults, essential roles of Cys8 and Ser14 were commonly indicated, and the domain from Pro3 to Pro19 was responsible for the rescue action of HN, in which seven residues turned out to be essential. We also compared the neuroprotective action of S14G HN (HNG) with that of activity-dependent neurotrophic factor, IGF-I, or basic FGF for the antagonism against various AD-relevant insults (V642I-APP, NL-APP, M146L-PS1, N141I-PS2, and Aβ1–43). Although all of these factors could abolish neurotoxicity by Aβ1–43, only HNG could abolish cytotoxicities by all of them. HN and HN derivative peptides may provide a new insight into the study of AD pathophysiology and allow new avenues for the development of therapeutic interventions for various forms of AD.

Keywords: Humanin, neuronal cell death, rescue, Alzheimer's disease, mutant, Aβ

Suppressing neuronal death is mandatory to establish curative therapy for Alzheimer's disease (AD), because brain atrophy is the central abnormality in AD. Three kinds of known mutant genes cause familial AD (FAD): mutants of amyloid precursor protein (APP), presenilin (PS) 1, and PS2 (Shastry and Giblin, 1999). The most frequent causes for FAD are the mutations in PS1, whereas only a few mutations were found in PS2 (Cruts and Van Broeckhoven, 1998; Finckh et al., 2000). Among FAD-linked mutations of APP, V642 mutations to I, F, and G are the most popular cause (Hardy, 1992). In fewer FAD families, A617G, L648P, and K595N/M596L have been discovered in APP (Mullan et al., 1992; Hendriks and Van Broeckhoven, 1996; Kwok et al., 2000).

Multiple groups (Yamatsuji et al., 1996; Zhao et al., 1997; Luo et al., 1999) found that expression of V642I/F/G-APP causes death in multiple neuronal lines and primary neurons. Hashimoto et al. (2000) found that both V642I-APP and K595M/N596L-APP (NL-APP) causes neuronal cell death at as low expression as endogenous APP. Also, N141I-PS2 augments death in PC12 cells (Wolozin et al., 1996). FAD mutant PS1 enhances death in PC12 cells (Guo et al., 1996; Weihl et al., 1999) and primary neurons (Czech et al., 1998; Zhang et al., 1998; Guo et al., 1999; Weihl et al., 1999). Rohn et al. (2000) and Sudo et al. (2000,2001) independently found that treatment of neuronal cells with anti-APP antibody remarkably enhances the neurotoxic function of wild-type (wt) APP, whose overexpression could cause AD type of neurodegeneration in Down's syndrome. Therefore, an important clue in the development of AD therapy would be provided by finding the molecules that suppress neuronal cell death by these AD-relevant insults.

For this purpose, we used “death-trap” screening, developed byD'Adamio et al. (1997): an unbiased functional screening of molecules that allow dying cells to survive. We applied this method to V642I-APP-inducible neuronal cells (Niikura et al., 2000) with our unique modification. In the original screening, a normal tissue cDNA library was transfected to Jurkat cells, which were killed by T cell receptor antibody, and library fragments were recovered from surviving cells. In contrast, our approach was unique in that we used an expression cDNA library constructed from an occipital lobe of an autopsy-diagnosed AD patient brain, because we reasoned that neuroprotective genes must be expressed in an occipital lobe of the AD brain, which is maintained intact throughout the course. As a result of this screening, we identified Humanin (HN) cDNA, encoding a novel short polypeptide MAPRGFSCLLLLTSEIDLPVKRRA, that suppresses neuronal cell death by the four representative FAD genes (V642I-APP, NL-APP, M146L-PS1, and N141I-PS2) and by Aβ1–43 (Hashimoto et al., 2001a,b). Here, we characterize the neuroprotective function of HN against other AD-relevant insults, detailed structure–function relationship, and comparison with other neurotrophic factors known to protect against Aβ neurotoxicity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Genes, polypeptides, and materials. V642I-APP and NL-APP cDNAs (Yamatsuji et al., 1996; Hashimoto et al., 2001a,b) and M146L-PS1 and N141I-PS2 cDNAs (Hashimoto et al., 2001a), all in pcDNA vectors, were described previously. Other mutant PS1 cDNAs were provided by Dr. Peter St. George-Hyslop (University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada) and used after being subcloned to pcDNA. A617G-APP and L648P-APP cDNAs were constructed from wtAPP695(Sudo et al., 2001) using a kit (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) and inserted to pcDNA. HN peptides were chemically synthesized and purified to >95% purity (Peptide Institute, Osaka, Japan). Some of the HN peptides were synthesized by Sawady (Tokyo, Japan), which provided similar results. Activity-dependent neurotrophic factor (ADNF) was synthesized as ADNF-9, whose sequence is SALLRSIPA (Glazner et al., 1999). Both insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) were purchased from Roche Molecular Biochemicals (Mannheim, Germany). Other materials were obtained from commercial sources.

Cells and cell death experiments. F11 cells, the hybrid cells of a rat embryonic day 13 (E13) primary cultured neuron and a mouse neuroblastoma, were grown in Ham's F-12 (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD) plus 18% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Hyclone, Logan, UT) and antibiotics, as described previously (Platika et al., 1985; Yamatsuji et al., 1996; Huang et al., 2000;Niikura et al., 2001). F11 cells (7 × 104 cells per well in a six-well plate cultured in Ham's F-12 plus 18% FBS for 12–16 hr) were transfected with plasmids encoding FAD genes by lipofection [1 μg of FAD cDNA, 2 μl of LipofectAMINE, and 4 μl of PLUS reagent (Life Technologies)] in the absence of serum for 3 hr and were incubated with Ham's F-12 plus 18% FBS for 2 hr. Then, culture media were changed to Ham's F-12 plus 10% FBS with or without HN peptides, and cells were cultured for an additional 67 hr. Seventy-two hours after transfection, cell mortality was measured by trypan blue exclusion assay, performed as follows. Cells were suspended by pipetting gently, and 50 μl of 0.4% (finally 0.08%) Trypan blue solution (Sigma, St Louis, MO) was mixed with 200 μl of the cell suspension at room temperature. Stained cells were counted within 3 min after the mixture with trypan blue solution. The primary culture of mouse cortical neurons was performed in poly-d-lysine-coated 24-well plates (Sumitomo Bakelite, Akita, Japan), in the absence of serum and the presence of N2 supplement, as described previously (Sudo et al., 2000). The purity of neurons by this method was >98%. Prepared neurons (1.25 × 105 cells per well and 250 μl of culture media per well) were preincubated with or without x molar (xm) synthetic HN (sHN) for 16 hr and treated with 25 μm Aβ in the presence or absence of xm sHN for 72 hr. Because primary neurons were vulnerable to transient dryness during medium exchange, we treated neurons with 25 μm Aβ as follows. First, a half volume (125 μl) of old medium was discarded. Then, 125 μl of prewarmed fresh medium containing 50 μmAβ and xm sHN (Aβ was directly resolved) was added to the culture. Aβ1–42, Aβ1–43, Aβ25–35, and a synthetic peptide corresponding to prion protein (PrP) residues 106–126 (PrP106–126) were purchased from Bachem (Budendorf, Switzerland) and Peptide Institute. The Aβ peptides used at 25 μm to induce neurotoxicity formed aggregation in the medium during the cell culture at 37°C for 72 hr (Hashimoto et al., 2001a). The experiments using PrP106–126 or anti-APP antibody 22C11 (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland) were similarly performed using PrP106–126 or 22C11 instead of Aβ. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay was performed using a kit (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan) by sampling 6 μl of the media culturing neurons, according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Calcein staining was performed as described previously (Hashimoto et al., 2001a). In brief, 6 μm calcein AM (3′,6′-di-(O-acetyl)-2′,7′-bis [N,N-bis (carboxymethyl) aminomethyl] fluorescein, tetraacetoxymethyl ester; Dojindo) was added to neurons, and >30 min after calcein AM treatment, calcein-specific fluorescence (excitation, 485 nm; emission, 535 nm) was observed by fluorescence microscopy or measured by a spectrofluorometer (Wallac1420 ARVOsx Multi Label Counter).

Immunoblot analysis. Immunoblot analysis was performed as described previously (Hashimoto et al., 2001a,b). For the analysis of mutant PS1 expression, lysates (20 μg/lane) from cells transfected with each PS1 mutant were submitted to SDS-PAGE and were electrically blotted to a polyvinylidene difluoride sheet. After blocking, the sheet was soaked with anti-PS1 N-terminus antibody (1:2000 dilution;Chemicon, Temecula, CA) and then with 1:2000 of HRP-labeled anti-rat IgG antibody. The antigenic bands were visualized by ECL (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden).

Statistical analysis. All experiments described in this study were repeated at least three times with independent transfections or treatments. Statistical analysis was performed with Student'st test, in which p < 0.05 was assessed as significant.

RESULTS

Effect of sHN and its derivatives on Aβ1–42-induced neuronal death

As reported in previous studies (Yankner et al., 1990; Loo et al., 1993; Pike et al., 1993; Gschwind and Huber, 1995; Kaneko et al., 1995;Giovanni et al., 1999; Sudo et al., 2001), ≥10 μmAβ1–42 causes massive cell death in neurons. Although we identified previously the protective effects of HN and S14G HN (HNG) against neurotoxicity by Aβ1–43 (Hashimoto et al., 2001a., 1994; Mann et al., 1996) and because it is believed that Aβ42 neurotoxicity contributes to the pathogenesis of AD, we emphasize that there is no evidence showing that there is a difference between neurotoxicity by Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–43. We thus examined the effect of sHN or its derivative peptides on Aβ1–42-induced neuronal death (Fig.1). When primary cortical neurons were treated with 25 μm Aβ1–42, 70–80% of neurons underwent death within 72 hr, when only 20–30% of nontreated control cells did so (Fig. 1A, left). When neurons were treated with 25 μm Aβ1–42 in the presence of 10 μm sHN, cells died at a rate similar to that observed for nontreated neurons. This indicates that the death rate of neurons augmented by 25 μmAβ1–42 was completely suppressed by 10 μmsHN. This was also the case with synthetic HNG (sHNG), which at concentrations as low as 10 nm totally suppressed Aβ1–42-induced neuronal death. In contrast, synthetic C8A HN (sHNA) was without effect, even at concentrations as high as 10 μm.

Fig. 1.

Effect of sHN and its variants on neurotoxicity by Aβ1–42. A, Primary cultured cortical neurons were treated with 25 μm Aβ1–42 in the presence or absence of sHN (10 nm,L; 10 μm,H), 10 nm sHNG (L), or 10 μm sHNA (H). In these experiments, the indicated final concentrations of HN peptides were added 16 hr before the onset of treatment with Aβ1–42. Cell mortality (left) was measured 72 hr after Aβ treatment by trypan blue exclusion assay. Cell viability (right) was measured 72 hr after Aβ treatment by calcein assay in independent experiments same as in theleft panel. Similar experiments were performed at least three times with reproducible results. B, Seventy-two hours after treatment with Aβ1–42 in the presence or absence of HN peptides, neurons were stained with calcein AM, whose cytoplasmic fluorescence represents cell viability. Representative microscopic views are indicated. The insets indicate the twofold magnified views of the similarly treated cultures independent from the cultures shown. Similar experiments were performed at least three times. C, Primary cultured neurons were treated with 25 μm Aβ25–35 in the presence or absence of sHN (10 nm,L; 10 μm,H), sHNG (10 nm,L; 10 μm,H), or 10 μm(H) sHNA. Seventy-two hours after treatment, cell viability (measured by calcein fluorescence;right), as well as cell mortality (measured by trypan blue exclusion assay; left) were measured. All values in this study indicate means ± SD of at least three independent experiments. ** and * indicate significant and not significant versus Aβ treatment, respectively.

Cell viability assay using calcein confirmed these observations. Treatment of primary neurons with 25 μm Aβ1–42 resulted in a 70–80% decrease in viable cells, which were completely protected by 10 μm sHN and 10 nm sHNG but not by 10 nm sHN or 10 μm sHNA (Fig.1A, right). Figure 1Bindicates the microscopic views of calcein-loaded neurons treated with 25 μm Aβ1–42 in the presence or absence of 10 μm sHN, 10 nm sHNG, or 10 μm sHNA. Aβ1–42 treatment caused dystrophic neuritic changes as well as death of cell bodies, and the presence of 10 μm sHN or 10 nm sHNG, but not 10 μmsHNA, not only protected cell bodies from death but also prevented neurites from degeneration. These data demonstrate that HN completely protects neurons from Aβ1–42-induced neurodegeneration in a primary structure-dependent manner.

We also examined whether HN peptides inhibit neurotoxicity by Aβ25–35. The results, shown in Figure 1C, indicate that (1) sHN and sHNG were able to inhibit neurotoxicity by 25 μm Aβ25–35, but (2) they required 10–100 times higher concentrations to exert similar suppression of neurotoxicity by 25 μm Aβ1–42, and (3) sHNA was again without effect on Aβ25–35.

As a control, we examined whether HN peptides can antagonize glutamate neurotoxicity. Treatment of primary neurons with 20 μmglutamate resulted in massive cell death (cell mortality of total cells: no treatment, 28.1 ± 0.8%; 20 μm glutamate, 61.0 ± 5.7%). Neither sHN nor sHNG protected neurons from cytotoxicity by glutamate (cell mortality of total cells in the presence of 20 μm glutamate: 61.9 ± 3.9% by 10 μm sHN; 61.5 ± 0.2% by 10 μm sHNG; 62.1 ± 2.9% by 10 μm sHNA). These results provide additional lines of evidence that antagonistic actions of HN are selective (also see the effect of HNG on PrP106–126 in Fig.5A).

Fig. 5.

Comparison of the action of HNG with those of ADNF, IGF-I, and bFGF against Aβ1–43, V642I-APP, NL-APP, M146L-PS1, and N141I-PS2. A, Effects of sHNG, ADNF, bFGF, or IGF-I on neuronal death by Aβ1–43 or PrP106–126. Primary neurons were treated with 25 μm Aβ1–43 (left 4 panels) or 100 μm PrP106–126 (right 4 panels) in the presence or absence of various concentrations of sHNG (0, 10 pm, 100 pm, 1 nm, 10 nm, 100 nm, and 1 μm fromleft to right), ADNF (0, 10 am, 1 fm, 100 fm, 10 pm, 1 nm, and 10 nm fromleft to right), bFGF (0, 10 pg/ml, 100 pg/ml, 1 ng/ml, 10 ng/ml, 100 ng/ml, and 1 μg/ml from left toright), or IGF-I (0, 10 pm, 100 pm, 1 nm, 10 nm, 100 nm, and 1 μm from left to right).Top panels, Cell mortality was measured 72 hr after Aβ treatment by trypan blue exclusion assay. Bottom panels, Cell viability was measured 72 hr after Aβ treatment by calcein fluorescence assay in independent experiments. All values indicate means ± SD of at least three independent treatments. ** indicates significant versus Aβ treatment. B, Effects of sHNG, ADNF, bFGF, or IGF-I on neuronal cell death by FAD genes. F11 cells were transfected with V642I-APP, NL-APP, M146L-PS1, or N141I-PS2 cDNA in the presence or absence of the increasing concentrations of sHNG (0, 10 pm, 100 pm, 1 nm, 10 nm, 100 nm, and 1 μm fromleft to right), ADNF (10 am, 1 fm, 100 fm, 10 pm, 1 nm, and 10 nm from left to right), bFGF (0, 10 pg/ml, 100 pg/ml, 1 ng/ml, 10 ng/ml, 100 ng/ml, and 1 μg/ml from left to right), or IGF-I (10 pm, 100 pm, 1 nm, 10 nm, 100 nm, and 1 μm fromleft to right) for 72 hr, and cell mortality was similarly measured. In each series of experiments, cell mortality without transfection (no T) or with pcDNA transfection (vec) was measured as independent controls. ** indicates significance versus relevant FAD gene transfection.

Effect of sHN and its derivatives on neuronal death by anti-APP antibody

As Rohn et al. (2000) and Sudo et al. (2000, 2001) reported independently, treatment of primary neurons with anti-APP antibody 22C11 resulted in significantly increased cell death (Fig.2). When neurons were pretreated with 10 μm sHN, 22C11-induced neuronal death was nearly completely precluded (Fig. 2A). Neuroprotection was also reproduced by 10 nm and 10 μm sHNG but not by 10 nmsHN or 10 μm sHNA. The observed antagonism by 10 μm sHN and 10 nm sHNG, but not by 10 nm sHN or 10 μm sHNA, was also confirmed by the measurement of LDH release from 22C11-treated neurons (Fig. 2B). sHN at 10 μm and 10 nm-10 μm sHNG totally reverted the augmented release of LDH from 22C11-treated neurons to the basal levels, whereas 10 nm sHN or 10 μm sHNA had no effect. As was the case with their actions on the Aβ effect, sHN and sHNG exerted protective actions on the dystrophic neuritic changes of neurons by anti-APP antibody: 10 μm sHN and 10 nm sHNG, but not 10 nmsHN or 10 μm sHNA, prevented neurites from degeneration caused by 22C11 (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Effect of sHN and its derivatives on neurotoxicity by anti-APP antibody. Primary neurons were treated with 2.5 μg/ml 22C11 (anti-APP monoclonal antibody) in the presence or absence of sHN (10 nm,L; 10 μm, H), sHNG (10 nm,L; 10 μm,H), or 10 μm(H) sHNA. A, Cell mortality was measured by trypan blue exclusion assay 72 hr after the onset of 22C11 treatment. B, Cell damage was monitored before or after 22C11 treatment (at 24, 48, and 72 hr) by measuring released LDH in the culture medium. C, Phase-contrast microscopic views 72 hr after 22C11 treatment with or without sHN or HN derivatives. Representative views are indicated. Similar experiments were performed at least three times. ** and * indicate significant and not significant versus 22C11 treatment, respectively.

Effect of HN on neuronal cell death by APP mutants and PS mutants

Although it has been found that HN antagonizes neurotoxicity by V642I-APP and NL-APP (Hashimoto et al., 2001a,b), it was important to examine whether HN was protective against other FAD-linked mutants of APP, because the two mutations (V642I and K595N/M596L) in APP trigger neuronal cell death through different combinations of multiple mechanisms (Hashimoto et al., 2000). We next examined the effect of HN on F11 cell death by other APP mutants: A617G-APP and L648P-APP. F11 cells are neuronal hybrid cells established by fusing rat primary cultured E13 neurons with mouse NTG18 neuroblastoma cells and carry typical characteristics of primary cultured neurons, including generation of action potentials (Platika et al., 1985). As shown in Figure 3A, sHN dose-dependently suppressed death of F11 cells induced by A617G-APP and L648P-APP, and ≥10 μm sHN completely inhibited F11 cell death by both APP mutants (IC50 values were 100 nm to 1 μmagainst both mutants, which were comparable with the IC50 of the sHN effects against V642I-APP and NL-APP). In contrast, cell death by A617G-APP or L648P-APP was not suppressed by 100 μm sHNA, whereas ≥10 nm sHNG exerted complete inhibition of neuronal cell death by both mutants (IC50 values were 100 pm to 1 nm against both mutants). HN or HNG did not affect the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter-driven expression of these mutant APPs (data not shown), as reported previously for V642I-APP and NL-APP (Hashimoto et al., 2001a,b).

Fig. 3.

Effect of sHN and its derivatives on neuronal cell death by FAD genes. A, Effect of sHN and its derivatives on neuronal cell death induced by FAD-linked mutant APPs (A617G-APP and L648P-APP). F11 cells were transfected with or without either A617G-APP cDNA or L648P-APP cDNA and were treated with various concentrations of sHN (0, 10 pm, 100 pm, 1 nm, 10 nm, 100 nm, 1 μm, 10 μm, and 100 μm from left to right), sHNG (0, 10 pm, 100 pm, 1 nm, 10 nm, 100 nm, 1 μm, 10 μm, and 100 μm from left toright), and sHNA (0, 10 nm, 100 nm, 1 μm, 10 μm, and 100 μm from left to right). Seventy-two hours after transfection, cell mortality was similarly measured. As controls, cell mortality without transfection (no T) or with pcDNA transfection (vec) was measured in each experiment. B, Effect of sHN and its derivatives on neuronal cell death induced by FAD-linked mutant PS1s (A246E-PS1, L286V-PS1, C410Y-PS1, and H163R-PS1). Left, F11 cells were transfected with or without each mutant PS1 cDNA in pcDNA (pcDNA mutant PS1) and were treated with or without (1) 10 nm sHN (2), 10 μm sHN (3), 10 nm sHNG (4), or 10 μm sHNA (5). Seventy-two hours after transfection, cell mortality was similarly measured. As controls, cell mortality without transfection (no T) or with pcDNA transfection (vec) was measured in each experiment.Right, PS1 expression in the experiments shown in theleft panel. Seventy-two hours after transfection performed in the experiments shown in theleft panel, cell lysates were submitted to immunoblot analysis with anti-PS1 antibody [no T, no transfection; vec, pcDNA transfection instead of PS1 cDNAs; 1–5 correspond to those in the left panel (1, PS1 mutant transfection alone;2, PS1 mutant transfection in the presence of 10 nm sHN; 3, PS1 mutant transfection in the presence of 10 μm sHN; 4, PS1 mutant transfection in the presence of 10 nm sHNG; and5, PS1 mutant transfection in the presence of 10 μm sHNA)]. The top bands (∼50 kDa) correspond to the holoprotein of endogenous or mutant PS1s, and thebottom bands (∼30 kDa) correspond to the N-terminal fragments of the cognate PS1s. ** and * indicate significant and not significant versus relevant FAD gene transfection, respectively.

We next examined the effect of HN and its derivatives on neuronal cell death by A246E-PS1, L286V-PS1, C410Y-PS1, and H163R-PS1, all of which are the established causes of FAD. As was the case with M146L-PS1, all of these FAD mutants of PS1 caused cell death in F11 cells transfected with cognate cDNA for 72 hr. When transfected cells were treated with 10 μm sHN or 10 nm sHNG, the FAD gene-stimulated cell death was completely suppressed, and only basally occurring cell death was observed (Fig. 3B,left). In contrast, 10 nm sHN or 10 μm sHNA had no effect on cytotoxicities by A246E-PS1, L286V-PS1, C410Y-PS1, or H163R-PS1. The HN polypeptides did not affect the CMV promoter-driven expression of these mutants or their intracellular processing to the mature fragments (Fig. 3B,right), as reported previously for M146L-PS1 (Hashimoto et al., 2001a).

Detailed structure–function relationship for the defense activity of HN

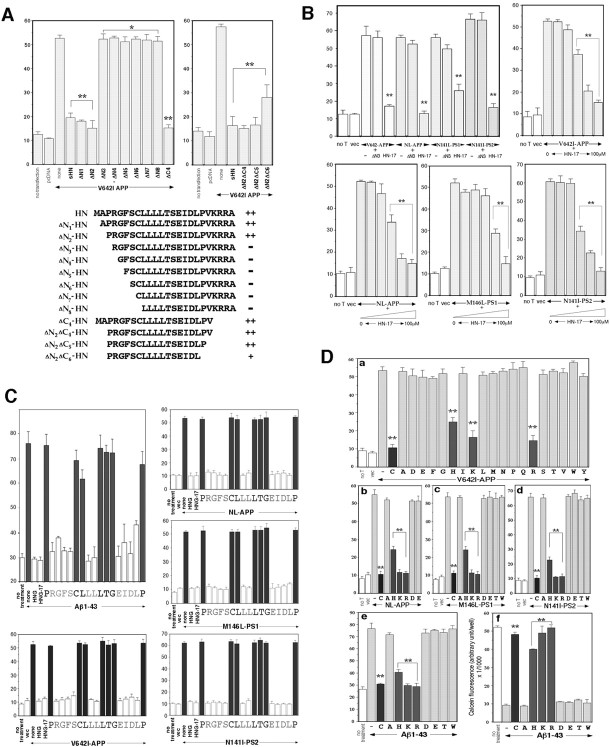

We investigated the detailed relationship between the primary amino acid structure and the rescue activity. Figure4A indicates the results of truncated HN peptides for the antagonism against V642I-APP. In the system in which F11 cells were transfected with V642I-APP cDNA and cultured in the presence of 10 μm of an HN derivative, N-terminal deletion of the two residues from HN little affected the protective activity. In contrast, N-terminal deletion of the three residues nullified the activity of HN, suggesting that the N-terminal dipeptide Met1-Ala2 was dispensable and that Pro3 was indispensable. A similar C-terminal deletion study, shown in Figure4A, revealed that the C-terminal pentapeptide Val20-Lys-Arg-Arg-Ala24was dispensable and that Pro19 was essential for maintaining the full protective activity of HN. The minimal region with the maximal activity was thus estimated to be Pro3-Pro19, consisting of 17 residues, termed HN-17 (equal to ΔN2ΔC5-HNin Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Detailed structure–function relationship for the rescue activity of HN. A, Effects of truncated HN derivatives on neuronal cell death by V642I-APP. F11 cells were transfected with V642I-APP cDNA in the presence or absence of each synthetic HN derivative (10 μm) for 72 hr, and cell mortality was similarly measured by trypan blue exclusion assay. Thetop left panel indicates the results of the examination in which the indicated N-terminally truncated peptides of HN were investigated. The top right panel indicates the results of the examination in which the indicated C-terminally truncated peptides of ΔN2 HN were investigated. The results obtained from the experiments shown in the panels are summarized in thebottom panel. ++, Strong suppression without significant differences from suppression by authentic HN; −, little suppression of cell death without significant differences from cell death by V642I-APP alone; +, intermediate suppression with significant differences from both V642I-APP alone and V642I-APP plus sHN. The vertical axis in all panels represents percentage of dead cells of total cells. B, Effects of ΔN3 HN and HN-17 on neuronal cell death by four representative FAD genes. F11 cells were transfected with V642I-APP, NL-APP, M146L-PS1, or N141I-PS2 cDNA in the presence or absence of 10 μm ΔN3 HN or 10 μm HN-17 for 72 hr, and cell mortality was similarly measured (top left panel). In otherpanels, the dose–response curves of the HN-17 effects for suppression of neuronal cell death by the four FAD genes are indicated. F11 cells were similarly transfected (Figure legend continued.) with each FAD gene in the presence or absence of increasing concentrations (0, 10 nm, 100 nm, 1 μm, 10 μm, and 100 μm from left toright) of HN-17 for 72 hr, and cell mortality was measured. In each series of experiments, cell mortality without transfection (no T) or with pcDNA transfection (vec) was measured as controls. ** and * inA and B indicate significant and not significant versus relevant FAD gene transfection, respectively.C, Effects of Ala-scanned HNG-17 on neuronal cell death by four representative FAD genes and Aβ1–43. Primary neurons were treated with 25 μm Aβ1–43 (top left panels) or F11 cells were transfected with each of V642I-APP, NL-APP, M146L-PS1, or N141I-PS2 cDNA (other panels) in the presence or absence of 10 nm Ala-substituted HNG-17 for 72 hr, and cell mortality was similarly measured. In this figure, cytoprotective effects were elicited by each Ala-substituted HNG-17 whose substituted residue was shown under the value of cell mortality. For instance (top left), when neurons were incubated with 25 μm Aβ1–43 in the presence of 10 nmARGFSCLLLLTGEIDLP (A is substituted fromP) for 72 hr, the cell mortality was 75.3 ± 4.4% (mean ± SD of three independent experiments), which was comparable with the mortality by Aβ1–43 incubation (76.1 ± 4.7%). When neurons were incubated with 25 μm Aβ1–43 in the presence of 10 nm HNG or HNG-17, the cell mortality was 29.3 ± 0.9 or 28.8 ± 1.3%, respectively, which was comparable with the basal mortality (30.0 ± 1.6%, shown asno treatment). When an Ala-substituted HNG-17 indicated drastic loss of neuroprotective activity, the correspondingcolumns are stained black. All values in these figures indicate means ± SD of three independent experiments. D, Effect of Cys8substitution on the rescue activity of HNG. a, F11 cells were transfected with or without V642I-APP cDNA (1 μg) and treated with each (10 nm) of the HNG mutant peptide whose Cys8 was substituted to one of the all 19 possible amino acid residue (indicated by one single letter). Cell mortality was measured 72 hr after the onset of transfection. The cell mortality above each letter represents the result of each experiment in which cells transfected with V642I-APP were incubated in the presence of 10 nm HNG with Cys8 substitution to the indicated amino acid residue. no T implies no transfection, andvec means empty pcDNA transfection without peptide treatment. C indicates authentic HNG. All values indicate means ± SD of three independent transfections.b–d, F11 cells were transfected with or without FAD gene (b, NL-APP; c, M146L-PS1;d, N141I-PS2) and treated with each (10 nm) of the HNG mutant peptide whose Cys8 was substituted to the indicated amino acid residue. Cell mortality was similarly measured 72 hr after the onset of transfection. All values indicate means ± SD of three independent transfections. e,f, Primary neurons were treated with 25 μmAβ1–43 in the presence of each (10 nm) of the HNG mutant peptide whose Cys8 was substituted to the indicated amino acid residue. The induced neurotoxicity was measured by trypan blue exclusion assay (e) and by calcein viability assay (f) 72 hr after the onset of Aβ treatment. All values indicate means ± SD of three independent transfections (a–d) or three independent treatments (e, f). ** indicates significant versus relevant FAD gene transfection (a–d) or Aβ treatment (e, f).

The left top panel of Figure 4B compares the effect of the N-terminal tripeptide-deleted HN (ΔN3) with the effect of HN-17 on neuronal cell death by four representative FAD genes (V642I-APP, NL-APP, M146L-PS1, and N141I-PS2). The data indicate that HN-17 exhibited sufficient antagonizing activity against death by these four FAD genes and that the ΔN3 peptide had no activity on either of them. The other panels of Figure 4Bindicate the dose–response relationships for the effects of HN-17 on neuronal cell death by the four FAD genes. Whereas the potency of HN-17 was slightly attenuated relative to that of authentic HN and higher doses were required to suppress cell death by M146L-PS1, low micromolar HN-17 exerted complete protection commonly against cytotoxicity by all four FAD genes, suggesting that the N-terminal two residues and the C-terminal five residues were dispensable for this common protective activity.

We further investigated which residue was essential for the neuroprotective activity of HN-17. We first confirmed that 10 nm HN-17 with S14G (HNG-17) completely suppressed death of F11 cells caused by V642I-APP, NL-APP, M146L-PS1, and N141I-PS2 and death of primary neurons by Aβ1–43 (Fig. 4C). Therefore, HNG-17 was as potent and efficacious as HNG against a wide spectrum of AD-relevant insults. We then synthesized HNG-17 mutants in which each residue from Pro3 to Pro19 was substituted to Ala one by one and examined the effect of each HNG-17 mutant on cytotoxicity by 25 μm Aβ1–43 in primary neurons. In Figure4C, neuroprotective effects are indicated for each Ala-substituted HNG-17 whose substituted residue is shown under the value of cell mortality. This examination clearly dissected the seven residues that were essential for the neuroprotection from Aβ1–43-induced death: Pro3, Cys8, Leu9, Leu12, Thr13, Gly14 (originally Ser14), and Pro19. Although this examination does not necessarily deny the role of other residues, they were exchangeable with Ala without altering the neuroprotective activity. The observed indispensability of Pro3 and Pro19 is consistent with the data from the truncation study that deletion with either Pro residue resulted in a complete loss of the antagonistic action (Fig. 4A). The indispensability of Cys8 and Gly14 in HNG-17 coincides well with the previous study (Hashimoto et al., 2001a), indicating that Cys8 and Ser14 play essential roles in HN against Aβ1–43. It should be emphasized that the Ser14 substitution to Gly caused potentiation of the neuroprotective activity, whereas the Ser14 substitution to Ala nullified the protective activity, suggesting that subtle changes of specific residues and their side chains affect the neuroprotective activity of HN against Aβ1–43 both positively and negatively.

The other panels in Figure 4C indicate the results of the examination for the effects of Ala-scanned HNG-17 on F11 neuronal cell death by each of V642I-APP, NL-APP, M146L-PS1, and N141I-PS2. The data revealed that the essential residues for the antagonism were exactly the same as observed for the antagonism against Aβ-induced neuronal death in primary neurons, strongly indicating that the mechanism whereby HN protects against neurotoxicity by AD-relevant insults is common not only against a wide spectrum of FAD genes and Aβ but also between primary neurons and F11 immortalized neuronal cells. These seven essential residues (Pro3, Cys8, Leu9, Leu12, Thr13, Ser14, and Pro19) would maintain a secondary or tertiary structure necessary for the recognition of a potential receptor molecule that commonly mediates the action of HN against various AD-relevant insults. This idea is quite consistent with our previous data demonstrating the existence of the specific binding of radiolabeled HNG on the cell surface (Hashimoto et al., 2001a).

Other structural dependency of HN

Our previous studies (Hashimoto et al., 2001a,b) and aforementioned data shown in this study clearly demonstrate the essential role of Cys8 in HN. Among others, Hashimoto et al. (2001a) showed that potent neuroprotective activity of HN requires the presence of a free thiol group in Cys8. However, such a requirement for the free thiol group in Cys8 may extremely limit the utility of HN when HN or its derivative is administered in a body, because various thiol group-modifying factors are present in plasma and tissues. For this reason, we examined whether certain residues can be substituted for Cys8without reducing the neuroprotective activity of HNG. Figure4Da indicates the results of the experiments in which each Cys8-substituted HNG was examined for the cytoprotective activity against V642I-APP-caused death of F11 cells, revealing that Lys and Arg substitutions for Cys8 did not alter the cytoprotective activity of HNG (Fig. 4Dc). In contrast, His substitution resulted in an HNG peptide with intermediately reduced activity, whereas all other 16 substitutions nullified the cytoprotective activity of HNG. These data indicate that either basic residue Lys or Arg can substitute Cys8 without attenuating the antagonizing activity against V642I-APP-induced neurotoxicity. We also tested whether this was the case against neurotoxicity by NL-APP, M146L-PS1, N141I-PS2, and Aβ1–43. As shown in Figure 4Db–De, Lys or Arg could substitute Cys8 without diminishing the antagonizing activity against neuronal cell death by NL-APP, M146L-PS1, N141I-PS2, and Aβ1–43, whereas His substitution resulted in an HNG peptide with intermediately reduced activity and other substitutions nullified the inhibitory activity against neurotoxicity by NL-APP, M146L-PS1, N141I-PS2, and Aβ1–43. Figure4Df indicates the results from the measurement of neuronal viability with calcein fluorescence assay. As reported previously (Hashimoto et al., 2001a), 25 μmAβ1–43 drastically diminished cell viability of primary neurons, and HNG completely recovered Aβ-treated neurons. HNG with C8K or C8R indicated as efficacious actions to recover Aβ-treated neurons as HNG, whereas HNG with C8H exhibited significantly attenuated antagonizing activity compared with HNG. In contrast, other substituents indicated no activity to recover. Thus, cell viability assay confirmed the results obtained from cell mortality.

We also noted that Arg4-Gly5 and Phe6-Ser7, respectively, are preferable sites for trypsin and chymotrypsin digestion. For the purpose of constructing more potent HNG derivatives, we therefore examined the action potency and efficacy of HNG with R4A and F6A, lacking both digestion sites. Complete suppression by R4A/F6A-HNG was observed at 100 pm against death of F11 cells by V642I-APP, NL-APP, M146L-PS1, and N141I-PS2 and at 300 pm against death of primary neurons by Aβ1–43 (IC50 values are 10–30 pm against V642I-APP, NL-APP, M146L-PS1, and N141I-PS2 and 30–100 pmagainst Aβ1–43) (data not shown), suggesting that R4A/F6A-HNG exerts inhibitory actions 3–10 times as potent as those of HNG.

Comparison of the action of HNG with those of ADNF, IGF-I, and bFGF against Aβ, V642I-APP, NL-APP, M146L-PS1, and N141I-PS2

We next compared the anti-FAD action of HNG with ADNF, IGF-I, and bFGF. Among known neurotrophic factors, ADNF (Brenneman and Gozes, 1996; Brenneman et al., 1998; Glazner et al., 1999), bFGF (Mark et al., 1997), and IGF-I (Dore et al., 1997) are known to suppress neurotoxicity by Aβ at femtomolar, low nanomolar, and high nanomolar concentrations, respectively, although ADNF cannot exert neuroprotection at concentrations higher than 100 pm. Here, we investigated whether and how these factors and HNG antagonize against neuronal cell death caused by the four representative FAD genes: V642I-APP, NL-APP, M146L-PS1, and N141I-PS2. First, the suppressive actions of these factors against Aβ1–43 were examined in comparison with the inhibitory action of HNG. As shown in Figure5A (left four panels), both cell mortality assay (trypan blue exclusion assay) and cell viability assay (calcein fluorescence assay) indicate that ADNF, IGF-I, and bFGF suppressed death of primary neurons augmented by Aβ1–43 as completely as HNG. One to 100 fmADNF, 100 pm to 1 nm IGF-I, 1–10 nm bFGF, and 1–10 nm HNG suppressed neuronal death by Aβ1–43 to the levels of basal cell death, indicating that these factors selectively abolish neurotoxicity by Aβ without affecting basally occurring death. Higher concentrations of IGF-I, bFGF, and HNG exerted complete neuroprotection, whereas ≥100 nm concentrations of ADNF lost its neuroprotective activity, as repeatedly reported in the literature (Brenneman and Gozes, 1996; Brenneman et al., 1998; Glazner et al., 1999). Although it remains unknown why the full action of ADNF was only observed at high femtomolar to low picomolar concentrations, such a phenomenon was not attributed to potential combination of its rescue action by low concentrations and its toxic action by higher concentrations, because ADNF alone was not neurotoxic, even at 100 nm (data not shown). In any event, these data indicate that all of ADNF, IGF-I, bFGF, and HNG can potently and completely protect neurons from Aβ neurotoxicity.

As a control, we examined the effect of HNG and other factors on neuronal death caused by PrP106–126. As reported previously (Forloni et al., 1996), treatment of primary neurons with micromolar PrP106–126 resulted in massive cell death. At up to 100 μm, sHNG could not protect against neurotoxicity by PrP106–126 (Fig.5A, right four panels). No effects on cytotoxicity by PrP106–126 were also the case with ADNF, IGF-I, and bFGF. Both trypan blue cell mortality assay and calcein fluorescence cell viability assay exhibited consistent results. Therefore, all of HNG, ADNF, IGF-I, and bFGF exerted selective neuroprotection against Aβ but not against the similarly amyloidogenic PrP fragment (Forloni et al., 1996).

We next investigated whether ADNF, IGF-I, and bFGF suppress neuronal cell death caused by V642I-APP (Fig. 5B, left top two panels). Whereas HNG totally suppressed V642I-APP-induced neuronal cell death to the level of basal cell death, all of ADNF, IGF-I, and bFGF partially inhibited V642I-APP-induced neurocytotoxicity down to the 30–35% level of cell death. Under the conditions used, V642I-APP-induced cytotoxicity consists of two independent cell deaths, wtAPP-induced cell death (30–35% of cell mortality), and V642I-specific cell death (50–60% of cell mortality), which occur in the same cells in a non-additive manner (Hashimoto et al., 2000). Therefore, it was highly likely that all of ADNF, IGF-I, and bFGF suppresses V642I-specific cytotoxicity but cannot inhibit wtAPP-induced cell death. In fact, ADNF, IGF-I, or bFGF could not affect wtAPP-induced death in F11 cells [in the experiments performed under the same conditions as in Figure 5B, cell death occurred for 72 hr were as follows (in percentage of dead cells per 72 hr, means ± SD of three independent transfections): no transfection, 9.0 ± 0.9%; pcDNA transfection, 9.9 ± 0.8%; wtAPP transfection, 33.6 ± 4.9%; wtAPP transfection plus 100 fm ADNF, 31.9 ± 1.0%; wtAPP transfection plus 100 ng/ml bFGF, 35.1 ± 0.1%; wtAPP transfection plus 10 nm IGF-I, 33.0 ± 1.7; and wtAPP transfection plus 10 nm HNG, 11.1 ± 1.5%]. In contrast, only HNG was able to suppress both V642I-specific cytotoxicity and wtAPP-induced cell death. The observed specific abolishment by IGF-I and bFGF of V642I-specific cytotoxicity coincides with the following: (1) V642I mutation-specific cell death occurs by apoptosis (Wolozin et al., 1996; Yamatsuji et al., 1996; Zhao et al., 1997; Luo et al., 1999; Hashimoto et al., 2000; Niikura et al., 2000); (2) wtAPP-induced cell death is nonapoptotic in F11 neuronal hybrid cells (Hashimoto et al., 2000); (3) both IGF-I and bFGF activate receptor tyrosine kinases that trigger anti-apoptotic mechanisms; and (4) IGF-I abolishes V642I-APP-induced apoptosis (Niikura et al., 2001). The inhibition by 10 nm HNG of wtAPP-induced cytotoxicity is consistent with that 10 nm HNG suppressed V642I-APP-induced cell death to the level of basal cell death.

The other panels of Figures 5B indicate the suppressive effects of ADNF, IGF-I, and bFGF on neuronal cell death by NL-APP, M146L-PS1, and N141I-PS2. At ≥10 nm, HNG exerted full suppression of neuronal cell death by all of these FAD genes (full suppression implies suppression down to the basal death levels). ADNF partially suppressed neurotoxicity by NL-APP down to the levels of cytotoxicity by wtAPP (see above). None of these factors except HNG suppressed neurotoxicity by M146L-PS1 and that by N141I-PS2. These data indicate the following: (1) except HNG, none of the known Aβ-antagonizing factors could inhibit neurotoxicity caused by mutant PS1 and PS2; and (2) neurocytotoxicity augmented by FAD mutants of PS does not occur through the same mechanisms as the neurocytotoxicity by APP mutants. The latter speculation does not conflict with the fact that all mutant PS1, PS2, and APP are causative of similar AD, because similar clinical manifestations could occur when these FAD mutants cause neuronal death in similar brain regions in similar time courses, mainly because the major, if not all, neurological abnormalities in AD patients are attributable to the result, but not the mechanism, of neuronal loss. These data demonstrate that HNG is the only Aβ-antagonizing factor that can abolish neurotoxicity by all known types of the FAD genes.

DISCUSSION

We showed herein that HN is effective in suppressing not only neurotoxicity by Aβ1–43, V642I-APP, NL-APP, M146L-PS1, and N141I-PS2 but also neurotoxicity by Aβ1–42/Aβ25–35, anti-APP antibody, other FAD mutants of APP (A617G-APP and L648P-APP), and other FAD mutants of PS1 (A246E-PS1, L286V-PS1, C410Y-PS1, and H163R-PS1). The observed effectiveness of HN against this broad spectrum of FAD genes provides the first advantage to this factor, when HN or HN derivatives are clinically applied. It is reasonable to assume that the curative reagent usable for sporadic AD patients must be effective at least on neurotoxicity by known FAD genes, because most sporadic AD occurs by yet unknown causes and a certain fraction of sporadic AD might share the causes with FAD. This study also indicates that HN is not effective in antagonizing neurotoxicity by glutamate or by PrP106–126. It has been shown that HN is not effective in suppressing neurotoxicity by a long polyglutamine repeat Q79, multiple superoxide dismutase 1 mutants causative of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or etoposide (Hashimoto et al., 2001a). Therefore, the present study lends additional credence to the notion that the neuroprotective function of HN is highly selective for FAD gene-relevant insults. This clear action selectivity provides the second advantage to HN as a potential therapeutic reagent of AD.

In addition, the present study indicates that HN is the only factor that can suppress neurocytotoxicity by FAD mutants of APP, PS1, and PS2 among the anti-Aβ neuroprotection factors that have thus far been reported. Although each of ADNF, IGF-I, and bFGF could suppress neurotoxicity induced by Aβ, as shown by previous studies (Brenneman and Gozes, 1996; Dore et al., 1997; Mark et al., 1997; Brenneman et al., 1998), ADNF, IGF-I, and bFGF only inhibited V642I-APP-induced cytotoxicity and could not affect neuronal cell death by mutant PS1 and PS2. In contrast, HN and HNG suppressed the neurotoxicities by mutants of APP, PS1, and PS2, which are all known FAD genes. Furthermore, it is quite characteristic that HN abolishes neurotoxicity by FAD genes without affecting basal cell death. Both total suppression by HN of AD-relevant neurotoxicity and lack of the HN action on basal cell death have been consistently noted in all cell systems so far investigated (Hashimoto et al., 2001a,b). These unique characteristics allow HN to be eligible to provide a basis of the development of therapeutic interventions for sporadic AD as well as FAD.

Finally, this study demonstrates that HN possesses a clear structural dependency for its neuroprotective function. The data indicate the following: (1) the Pro3-Pro19region acts as a core domain, among which Pro3, Cys8, Leu9, Leu12, Thr13, Ser14, and Pro19 are essential residues; and (2) Cys8 can be substituted to Lys and Arg without impairing the HN action, whereas His substitution significantly but not completely attenuated and any other substitution resulted in a loss of the rescue function of HN. Although it has been reported that iron mediates the neurotoxicity by Aβ peptides (Rottkamp et al., 2001), it is quite unlikely that HN and its active derivatives act as iron chelators, because of the following: (1) HN or HNG at ≤1 μm had no action on Aβ1–42 aggregation in vitro (data not shown), whereas Aβ aggregation is highly sensitive to redox-active metals, including iron (Jobling et al., 2001); and (2) HN and HNG had no inhibitory action against PrP106–126 induced neurotoxicity, as shown in this study, whereas neurotoxicity by PrP106–126 is abolished by chelation of redox-active metals (Jobling et al., 2001). In support of this notion, the presence of an HN action target other than Aβ is strongly indicated by the following observations: (3) HN and HNG were fully suppressive of neuronal death by anti-APP antibody, as shown in Figure 2, despite the fact that secreted Aβ does not mediate the neurotoxicity by anti-APP antibody (Sudo et al., 2001); and (4) HN and HNG can inhibit neuronal cell death by NL-APP mutant that cannot produce Aβ1–42 (Hashimoto et al., 2001b). It is also stressed that the observed potency of R4A/F6A-HNG, which exerts complete neuroprotection at 100–300 pm, is remarkable. It should also be emphasized that the profile for the alterations by various substitutions–deletions in the rescue function of HN was precisely the same for neurotoxicity by FAD mutants of APP, PS1, and PS2, and by Aβ. Therefore, HN most likely activates a mechanism that commonly suppresses these AD-relevant insults, pointing to the notion that a specific receptor mediates the action of HN. This is consistent with the previous study concluding the following: (1) HN acts on cells from the outside to exert its rescue function (Hashimoto et al., 2001a); and (2) the specific binding for HNG exists on the neuronal cell surface (Hashimoto et al., 2001a). The high potency, full efficacy, and strict selectivity of the action against a very wide spectrum of AD insults disclose a possibility that HNG and its additional derivatives may be quite useful as new therapeutic reagents for AD cases.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by grants from the Ono Medical Research Foundation, the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan, and the Organization for Pharmaceutical Safety and Research. We especially thank Kiyoshi Kurokawa, John T. Potts, Jr., Etsuro Ogata, and Keisuke Kouyama for essential help to this study. We are also indebted to Mark C. Fishman for F11 neuronal hybrids; Taisuke Tomita and Takeshi Iwatsubo for indispensable help; Peter St. George-Hyslop for various mutant PS1 cDNAs; Luciano D'Adamio for N141I-PS2 cDNA; Yusuke Tomita, Zongjun Shao, and Takako Hiraki for essential cooperation; Yumi and Yoshiomi Tamai for indispensable support; and Dovie Wylie and Kazumi Nishihara for expert assistance.

Y.H., T.N., and Y.I. contributed equally to this work.

Correspondence should be addressed to Ikuo Nishimoto, Department of Pharmacology and Neurosciences, Keio University School of Medicine, Shinanomachi, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 160-8582, Japan. E-mail:nisimoto@mc.med.keio.ac.jp.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brenneman DE, Gozes I. A femtomolar-acting neuroprotective peptide. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:2299–2307. doi: 10.1172/JCI118672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brenneman DE, Hauser J, Neale E, Rubinraut S, Fridkin M, Davidson A, Gozes I. Activity-dependent neurotrophic factor: structure-activity relationships of femtomolar-acting peptides. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;285:619–627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cruts M, Van Broeckhoven C. Presenilin mutations in Alzheimer's disease. Hum Mutat. 1998;11:183–190. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1998)11:3<183::AID-HUMU1>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Czech C, Lesort M, Tremp G, Terro F, Blanchard V, Schombert B, Carpentier N, Dreisler S, Bonici B, Takashima A, Moussaoui S, Hugon J, Pradier L. Characterization of human presenilin 1 transgenic rats: increased sensitivity to apoptosis in primary neuronal cultures. Neuroscience. 1998;87:325–336. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00162-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D'Adamio L, Lacana E, Vito P. Functional cloning of genes involved in T-cell receptor-induced programmed cell death. Semin Immunol. 1997;9:17–23. doi: 10.1006/smim.1996.0057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dore S, Kar S, Quirion R. Insulin-like growth factor I protects and rescues hippocampal neurons against β-amyloid- and human amylin-induced toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:4772–4777. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finckh U, Muller-Thomsen T, Mann U, Eggers C, Marksteiner J, Meins W, Binetti G, Alberici A, Hock C, Nitsch RM, Gal A. High prevalence of pathogenic mutations in patients with early-onset dementia detected by sequence analyses of four different genes. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;66:110–117. doi: 10.1086/302702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Forloni G, Bugiani O, Tagliavini F, Salmona M. Apoptosis-mediated neurotoxicity induced by β-amyloid and PrP fragments. Mol Chem Neuropathol. 1996;28:163–171. doi: 10.1007/BF02815218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giovanni A, Wirtz-Brugger F, Keramaris E, Slack R, Park DS. Involvement of cell cycle elements, cyclin-dependent kinases, pRb, and E2F·DP, in β-amyloid-induced neuronal death. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:19011–19016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.27.19011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glazner GW, Boland A, Dresse AE, Brenneman DE, Gozes I, Mattson MP. Activity-dependent neurotrophic factor peptide (ADNF9) protects neurons against oxidative stress-induced death. J Neurochem. 1999;73:2341–2347. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0732341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gschwind M, Huber G. Apoptotic cell death induced by β-amyloid 1–42 peptide is cell type dependent. J Neurochem. 1995;65:292–300. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65010292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo Q, Furukawa K, Sopher BL, Pham DG, Xie J, Robinson N, Martin GM, Mattson MP. Alzheimer's PS-1 mutation perturbs calcium homeostasis and sensitizes PC12 cells to death induced by amyloid β-peptide. NeuroReport. 1996;8:379–383. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199612200-00074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo Q, Sebastian L, Sopher BL, Miller MW, Glazner GW, Ware CB, Martin GM, Mattson MP. Neurotrophic factors [activity-dependent neurotrophic factor (ADNF) and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF)] interrupt excitotoxic neurodegenerative cascades promoted by a PS1 mutation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:4125–4130. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.4125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hardy J. Framing β-amyloid. Nat Genet. 1992;1:233–234. doi: 10.1038/ng0792-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hashimoto Y, Niikura T, Ito Y, Nishimoto I. Multiple mechanisms underlie neurotoxicity by different type Alzheimer's disease mutations of amyloid precursor protein. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:34541–34551. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005332200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hashimoto Y, Niikura T, Tajima H, Yasukawa Y, Sudo H, Ito Y, Kita Y, Kawasumi M, Kouyama K, Doyu M, Sobue G, Koide T, Tsuji S, Lang J, Kurokawa K, Nishimoto I. A rescue factor abolishing neuronal cell death by a wide spectrum of familial Alzheimer's disease genes and Aβ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001a;98:6336–6341. doi: 10.1073/pnas.101133498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hashimoto Y, Ito Y, Niikura T, Shao Z, Hata M, Oyama F, Nishimoto I. Mechanisms of neuroprotection by a novel rescue factor Humanin from Swedish mutant amyloid precursor protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001b;283:460–468. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hendriks L, Van Broeckhoven C. A βA4 amyloid precursor protein gene and Alzheimer's disease. Eur J Biochem. 1996;237:6–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0006n.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang P, Miao S, Fan H, Sheng Q, Yan Y, Wang L, Koide SS. Expression and characterization of the human YWK-II gene, encoding a sperm membrane protein related to the Alzheimer βA4-amyloid precursor protein. Mol Hum Reprod. 2000;6:1069–1078. doi: 10.1093/molehr/6.12.1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iwatsubo T, Odaka A, Suzuki N, Mizusawa H, Nukina N, Ihara Y. Visualization of Aβ42(43) and Aβ40 in senile plaques with end-specific Aβ monoclonals: evidence that an initially deposited species is Aβ42(43). Neuron. 1994;13:45–53. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90458-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jobling MF, Huang X, Stewart LR, Barnham KJ, Curtain C, Volitakis I, Perugini M, White AR, Cherny RA, Masters CL, Barrow CJ, Collins SJ, Bush AI, Cappai R. Copper and zinc binding modulates the aggregation and neurotoxic properties of the prion peptide PrP106–126. Biochemistry. 2001;40:8073–8084. doi: 10.1021/bi0029088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaneko I, Yamada N, Sakuraba Y, Kamenosono M, Tutsumi S. Suppression of mitochondrial succinate dehydrogenase, a primary target of β-amyloid, and its derivative racemized at Ser residue. J Neurochem. 1995;65:2585–2593. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65062585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kwok JB, Li QX, Hallupp M, Whyte S, Ames D, Beyreuther K, Masters CL, Schofield PR. Novel Leu723Pro amyloid precursor protein mutation increases amyloid beta42(43) peptide levels and induces apoptosis. Ann Neurol. 2000;47:249–253. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(200002)47:2<249::aid-ana18>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Loo DT, Copani A, Pike CJ, Whittemore ER, Walencewicz AJ, Cotman CW. Apoptosis is induced by β-amyloid in cultured central nervous system neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:7951–7955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.17.7951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luo JJ, Wallace W, Riccioni T, Ingram DK, Roth GS, Kusiak JW. Death of PC12 cells and hippocampal neurons induced by adenoviral-mediated FAD human amyloid precursor protein gene expression. J Neurosci Res. 1999;55:629–642. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19990301)55:5<629::AID-JNR10>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mann DM, Iwatsubo T, Ihara Y, Cairns NJ, Lantos PL, Bogdanovic N, Lannfelt L, Winblad B, Maat-Schieman ML, Rossor MN. Predominant deposition of amyloid-beta 42(43) in plaques in cases of Alzheimer's disease and hereditary cerebral hemorrhage associated with mutations in the amyloid precursor protein gene. Am J Pathol. 1996;148:1257–1266. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mark RJ, Keller JN, Kruman I, Mattson MP. Basic FGF attenuates amyloid β-peptide-induced oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and impairment of Na+/K+-ATPase activity in hippocampal neurons. Brain Res. 1997;756:205–214. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00196-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mullan M, Crawford F, Axelman K, Houlden H, Lilius L, Winblad B, Lannfelt L. A pathogenic mutation for probable Alzheimer's disease in the APP gene at the N-terminus of β-amyloid. Nat Genet. 1992;1:345–347. doi: 10.1038/ng0892-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Niikura T, Murayama N, Hashimoto Y, Ito Y, Yamagishi Y, Matsuoka M, Takeuchi Y, Aiso S, Nishimoto I. V642I APP-inducible neuronal cells: a model system for investigating Alzheimer's disorders. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;274:445–454. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Niikura T, Hashimoto Y, Okamoto T, Abe Y, Yasukawa T, Kawasumi M, Hiraki T, Kita Y, Terashita K, Kouyama K, Nishimoto I. Insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) protects cells from apoptosis by Alzheimer's V642I mutant APP through IGF-I receptor in an IGF-binding protein-sensitive manner. J Neurosci. 2001;21:1902–1910. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-06-01902.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pike CJ, Burdick D, Walencewicz AJ, Glabe GG, Cotman CW. Neurodegeneration induced by β-amyloid peptides in vitro: the role of peptide assembly state. J Neurosci. 1993;13:1676–1687. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-04-01676.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Platika D, Boulos MH, Braizer L, Fishman MC. Neuronal traits of clonal cell lines derived by fusion of dorsal root ganglia neurons with neuroblastoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:3499–3503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.10.3499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rohn TT, Ivins KJ, Bahr BA, Cotman CW, Cribbs DH. A monoclonal antibody to amyloid precursor protein induces neuronal apoptosis. J Neurochem. 2000;74:2331–2342. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0742331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rottkamp CA, Raina AK, Zhu X, Gaier E, Bush AI, Atwood CS, Chevion M, Perry G, Smith MA. Redox-active iron mediates amyloid-β toxicity. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;30:447–450. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00494-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shastry BS, Giblin FJ. Genes and susceptible loci of Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res Bull. 1999;48:121–127. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(98)00156-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sudo H, Jiang H, Yasukawa T, Hashimoto Y, Niikura T, Kawasumi M, Matsuda S, Takeuchi Y, Aiso S, Matsuoka M, Murayama Y, Nishimoto I. Antibody-regulated neurotoxic function of cell-surface β-amyloid precursor protein. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2000;16:708–723. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2000.0910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sudo H, Hashimoto Y, Niikura T, Shao Z, Yasukawa T, Ito Y, Yamada Y, Hata M, Hiraki T, Kawasumi M, Kouyama K, Nishimoto I. Secreted Aβ does not mediate neurotoxicity by antibody-stimulated amyloid precursor protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;282:548–556. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weihl CC, Ghadge GD, Kennedy SG, Hay N, Miller RJ, Roos RP. Mutant presenilin-1 induces apoptosis and downregulates Akt/PKB. J Neurosci. 1999;19:5360–5369. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-13-05360.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wolozin B, Iwasaki K, Vito P, Ganjei JK, Lacana E, Sunderland T, Zhao B, Kusiak JW, Wasco W, D'Adamio L. Participation of presenilin 2 in apoptosis: enhanced basal activity conferred by an Alzheimer mutation. Science. 1996;274:1710–1713. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamatsuji T, Matsui T, Okamoto T, Komatsuzaki K, Takeda S, Fukumoto H, Iwatsubo T, Suzuki N, Asami-Odaka A, Ireland S, Kinane TB, Giambarella U, Nishimoto I. G protein-mediated neuronal DNA fragmentation induced by familial Alzheimer's disease-associated mutants of APP. Science. 1996;272:1349–1352. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5266.1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yankner BA, Duffy LK, Kirschner DA. Neurotrophic and neurotoxic effects of amyloid β protein: reversal by tachykinin neuropeptides. Science. 1990;250:279–282. doi: 10.1126/science.2218531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang Z, Hartmann H, Do VM, Abramowski D, Sturchler-Pierrat C, Staufenbiel M, Sommer B, van de Wetering M, Clevers H, Saftig P, De Strooper B, He X, Yankner BA. Destabilization of β-catenin by mutations in presenilin-1 potentiates neuronal apoptosis. Nature. 1998;395:698–702. doi: 10.1038/27208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao B, Chrest FJ, Horton WE, Jr, Sisodia SS, Kusiak JW. Expression of mutant amyloid precursor proteins induces apoptosis in PC12 cells. J Neurosci Res. 1997;47:253–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]