Abstract

Objectives: There are no known studies of concurrent exposure to high temperature and yoga for the treatment of depression. This study explored acceptability and feasibility of heated (Bikram) yoga as a treatment for individuals with depressive symptoms.

Design: An 8-week, open-label pilot study of heated yoga for depressive symptoms.

Subjects: 28 medically healthy adults (71.4% female, mean age 36 [standard deviation 13.57]) with at least mild depressive symptoms (Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression [HRSD-17] score ≥10) who attended at least one yoga class and subsequent assessment visit.

Intervention: Participants were asked to attend at least twice weekly community held Bikram Yoga classes. Assessments were performed at screening and weeks 1, 3, 5, and 8. Hypotheses were tested using a modified-intent-to-treat approach, including participants who attended at least one yoga class and subsequent assessment visit (N = 28).

Results: Almost half of our subjects completed the 8-week intervention, and close to a third attended three quarters or more of the prescribed 16 classes over 8 weeks. Multilevel modeling revealed significant improvements over time in both clinician-rated HRSD-17 (p = 0.003; dGLMM = 1.43) and self-reported Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; p < 0.001, dGLMM = 1.31) depressive symptoms, as well as the four secondary outcomes: hopelessness (p = 0.024, dGLMM = 0.57), anxiety (p < 0.001, dGLMM = 0.78), cognitive/physical functioning (p < 0.001, dGLMM = 1.34), and quality of life (p = 0.007, dGLMM = 1.29). Of 23 participants with data through week 3 or later, 12 (52.2%) were treatment responders (≥50% reduction in HRSD-17 score), and 13 (56.5%) attained remission (HRSD score ≤7). More frequent attendance was significantly associated with improvement in self-rated depression symptoms, hopelessness, and quality of life.

Conclusions: The acceptability and feasibility of heated yoga in this particular sample with this protocol warrants further attention. The heated yoga was associated with reduced depressive symptoms, and other improved related mental health symptoms, including anxiety, hopelessness, and quality of life.

Keywords: yoga, heated yoga, depression, major depressive disorder (MDD), heat, hyperthermia

Introduction

Depressive disorders are associated with significant morbidity.1 The largest study of standard antidepressant treatment outcomes in major depressive disorder (MDD) reported an overall cumulative remission rate of only 67% for a multistep treatment involving both antidepressant medications and cognitive therapy,2 which may be lower, depending on the outcome measure reported.3 This reinforces the need for novel treatments. Heated yoga, an intervention that combines yoga and heat (the latter effectively a form of whole body hyperthermia [WBH]), is an understudied but increasingly popular and promising area for intervention research.

There has been mounting evidence that yoga has antidepressant effects. Two meta-analyses—one comprising 12 studies of adults with depressive symptoms4 and the other including 7 studies of adults with MDD5—suggested that yoga may be effective for treating depression. A lack of rigorous methodology (e.g., lack of standard reporting, a priori sample size calculations, randomization, allocation concealment, intention-to-treat analyses, blinding) prevents more definitive conclusions.5,6 Another limitation of the literature is the broad range of yoga styles employed, differing in postures, duration, and practice conditions, which limits the generalizability of findings.

Recent pilot evidence demonstrated that WBH, at temperatures similar to those offered in some forms of heated yoga (i.e., Bikram yoga [BY]), has antidepressant effects.7,8 In a double-blind randomized controlled trial (RCT), 34 medication-free patients with MDD were randomized to a single WBH session (temperature = 38.5°C/101.3°F) versus a plausible sham involving a lower temperature exposure.7 Participants receiving WBH demonstrated reduced depression scores, with greater effect sizes (d = 2.23–1.66, weeks 1–6 post treatment) than typically observed in antidepressant trials.7 The authors hypothesized that thermoregulatory cooling system dysregulation in depressed patients may be targeted by WBH.7–9

While the above studies might hypothetically suggest that the combination of yoga postures and heat may have additive or synergistic antidepressant effects, heated yoga has not yet been studied as a treatment for depression. BY is a popular heated yoga practice comprising 26 postures and 2 breathing exercises, with most postures performed twice in sequence during a 90-min session (Table 1).

Table 1.

Bikram Yoga Series

| Posture name in Sanskrit | Posture name in English | |

|---|---|---|

| Standing series | ||

| 1 | Pranayama | Standing deep breathing |

| 2 | Ardha-Chandrasana and Pada-Hastasana | Half moon pose and hands to feet |

| 3 | Utkatasana | Awkward |

| 4 | Garurasana | Eagle |

| 5 | Dandayamana-Janushirasana | Standing head to knee |

| 6 | Dandayamana-Dhanurasana | Standing bow pulling |

| 7 | Tuladandasana | Balancing stick |

| 8 | Dandayamana-Bibhaktapada-Paschimotthanasana | Standing separate leg stretching |

| 9 | Trikanasana | Triangle |

| 10 | Dandayamana-Bibhaktapada-Janushirasana | Standing separate leg head to knee |

| 11 | Tadasana | Tree |

| 12 | Padangustasana | Toe stand |

| Floor series | ||

| 13 | Savasana | Dead body |

| 14 | Pavanamuktasana | Wind removing |

| 15 | Yoga Sit-Up | Yoga sit-up |

| 16 | Bhujangasana | Cobra |

| 17 | Salabhasana | Locust |

| 18 | Poorna-Salabhasana | Full locust |

| 19 | Dhanurasana | Bow |

| 20 | Supta-Vajrasana | Fixed firm |

| 21 | Ardha-Kurmasana | Half tortoise |

| 22 | Ustrasana | Camel |

| 23 | Sasangasana | Rabbit |

| 24 | Janushirasana with Paschimotthanasana | Head to knee |

| 25 | Ardha-Matsyendrasana | Spine twisting |

| 26 | Khapalbhati | Blowing in firm |

Three studies of BY have been conducted among individuals experiencing high stress. In an uncontrolled study of 51 individuals, BY was associated with increased mindfulness and decreased stress.10 In an RCT of adult females with high perceived stress scores, dietary restraint, and emotional eating, BY demonstrated significant effects on perceived stress, stress reactivity, distress tolerance, and disordered eating behaviors relative to a waitlist control.11,12 In another RCT with stressed adults, BY (compared to a no treatment control) was associated with significant decreases in perceived stress, self-efficacy, and two domains of health-related quality of life.13 While these studies support the mental health benefits of heated yoga, no studies to date have evaluated its effects on depressive symptoms in clinical populations.

The purpose of this study is to investigate for the first time the acceptability and feasibility of heated yoga as a treatment of depression and explore its association with depressive symptoms. We hypothesized that heated yoga would be well received by a depressed population, and that attending heated yoga classes would be associated with significant decreases in depressive symptom severity, and improvements in other related constructs, including hopelessness, anxiety, quality of life, and cognitive and physical functioning.

Materials and Methods

Study design

This study examined the acceptability, feasibility, and the association with depressive symptoms of an open-label BY intervention for medically healthy participants with clinically significant depressive symptoms. Patients were asked to attend at least two community held (already existing) BY classes per week for 8 weeks in either of two community BY studios (under the same ownership). This was a first-step study to explore this potential modality of treatment, which allowed for “all comers”—in that, the study explored BY as both a monotherapy (alone without medications) and as an augmentation (in addition to stable, established use of medication and/or psychotherapy). The inclusion of both groups allowed for greater generalizability to reflect real-world populations.

Participants

Participants were recruited through the Depression Clinical and Research Program (DCRP) at the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) (e.g., through flyers and on-line advertisements) and through the participating yoga studios' websites and posted flyers. The Partners Human Research Committee Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved this protocol, and written informed consent was obtained before participation. Research visits were conducted at the DCRP.

Inclusion criteria: 18–65 years of age; depressive symptoms in at least the mild range (Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression [HRSD-17] total score ≥10).14

Exclusion criteria: substance abuse or dependence within the last 6 months; epilepsy, history of an abnormal electroencephalogram (EEG), severe head trauma, or stroke; lifetime history of psychosis or mania; current eating disorder; serious or uncontrolled medical conditions that could make participation unsafe; current active suicidal ideation or self-injurious behavior; electroconvulsive therapy within the past year; plans to become pregnant; participation in any single heated yoga session within the past 12 weeks; or any regular yoga practice (≥3 sessions per week for ≥1 month) within the past year. Concurrent treatment for depression was allowed, provided it was not recently initiated or altered during the study; this included established psychotherapy (at least 3 months) and/or stable psychotropic medications/doses (at least 4 weeks).

Intervention

Participants were provided with a free-of-charge, 8-week unlimited memberships to two Boston-area BY studios and were asked to attend at least two classes per week for 8 weeks. Research staff and the co-owners of two study-affiliated yoga studios (Jill, Brad, and Tomo Koontz) met before beginning the study to ascertain fidelity of the study intervention delivery. Patients were given the option to attend classes at both studios interchangeably (one location in Boston, one in Cambridge), and were informed of the studios' locations before entering the study to assure the accessibility of the classes. Both were readily accessible by public transportation.

BY provides a standardized intervention consisting of 26 sequenced postures (asanas) and two breathing exercises (pranayama), practiced for 90 min in a room heated to 105°F with 40% relative humidity. Please see Table 1 for a full list of the postures. The sequence is administered by trained instructors who follow a standardized dialogue and postures are held for the same duration in each class. BY instructors were trained and certified during an intensive 9-week teacher-training program at Bikram's Yoga College of India and are recertified every 3 years.15 The participating studios were in compliance with BY certification requirements. Intervention adherence was tracked using attendance data collected through a computerized system at the studios, transmitted to study staff via HIPAA-compliant means (i.e., via “SEND SECURE,” an institutional encrypted e-mail system for recipients outside the institutional firewall). Before their first BY class, participants completed a 50-min psychoeducational visit outlining expectations for this form of yoga and tips for practice.

Instruments and assessments

Assessments were completed at screen (referred to as “baseline” in analyses) and weeks 1, 3, 5, and 8 and 3 months following the first session. Self-report measures were completed via paper-and-pencil. Clinician-rated instruments were completed by a total of 12 psychiatrists, clinical psychologists, or supervised MD or PhD-level trainees. Psychiatric diagnoses were obtained at screening using the Structured Clinical Interview for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (SCID).16

Primary outcome measures

Feasibility and acceptability were assessed by attendance data and completion rates. The Structured Interview Guide for the HRSD-1714,17 was used to measure past-week depressive symptoms. Item ratings were summed for the first 17 items, with total scores indicating HRSD: not depressed (0–7), mildly depressed (8–16), moderately depressed (17–23), and severely depressed (≥ 24).18 Our group's clinicians routinely score observed recorded video interviews using the HRSD-17 with clinicians and actors as patients, with a current interrater reliability of 0.97 (Intraclass Correlation Coefficient). Self-report ratings of depression over the past week were measured with the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), which included 21 items rated on a scale from 0 to 3.19 Item ratings were summed to form total scores indicating normal (0–7), mild (8–13), moderate (14–18), severe (19–22), or very severe (>22) depression.20

Secondary outcome measures

Valid and reliable measures were administered for constructs frequently associated with depression: hopelessness, anxiety, quality of life, and functional impairment. Hopelessness was measured with the Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS), a self-report scale measuring negative attitudes about the future.21 The BHS includes 20 true/false statements. True responses are summed to form a total score indicating none or minimal (0–3), mild (4–8), moderate (9–14), or severe (14–20) hopelessness. Anxiety symptoms were assessed with the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), a self-report instrument.22 The BAI includes 21 items rated on a scale from 0 to 3. Total scores indicate minimal (0–7), mild (8–15), moderate (16–25), or severe (26–63) anxiety symptoms. Quality of life was measured with the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (QLESQ)-Short Form, a self-report instrument that assesses on a 1–5 scale, 13 specific areas of life including physical health, general feelings of wellbeing, work satisfaction, leisure activities, social relationships, medication, and overall life satisfaction over the past week.23 Higher scores indicate greater wellbeing. Functional impairment was assessed using the Massachusetts General Hospital Cognitive and Physical Functioning Questionnaire (CPFQ), a 7-item questionnaire that assesses difficulties with energy, alertness and cognition.24 Higher scores indicate greater impairment.

Alphas for the scales (not including the clinician-rated [HRSD] and dichotomous [BHS]) were as follows: BDI = 0.803; BAI = −0.841; QLESQ = 0.662; and CPFQ = 0.887.

Data analysis

SPSS version 20.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL) was used to complete all analyses. Feasbility and acceptability data (i.e., attendance and completion rates) were calculated using frequency data. Study hypotheses were tested by multilevel modeling (MLM), using restricted maximum-likelihood estimation and with repeated measures error covariance modeled as auto-regressive [AR(1)]. MLM is preferred for analyzing longitudinal data because it reduces bias due to participant dropout by including all participants regardless of missing data.25 A modified intent-to-treat approach was used; participants who attended at least one yoga class over the course of the study and one additional assessment following the baseline (BL) visit were included in the analyses. All analyses controlled for: (1) age (continuous); (2) use of antidepressants and other psychotropic medication (dichotomous); (3) baseline scores on the outcome measures (continuous); (4) and yoga attendance (i.e., intervention adherence; continuous). Time was centered at post-treatment (week-8), and standard (z) scores were used for all continuous covariates, to facilitate interpretation of β and p-values for main effects. Effect sizes were calculated per Feingold's recommendations for calculating and reporting effect sizes for linear mixed models [dGLMM = (bTIME × duration)/SDBL].26 Effect sizes for pre- to post-intervention change were also calculated by Cohen's d for repeated measures, using Morris and DeShon's equation (8) [dRM Mdiff/σ √2(1-/r)].27 To examine the effects of yoga attendance on degree of symptom change over time, post hoc analyses were conducted, adding a time-by-attendance interaction term to the MLM models above.

Results

Preliminary analyses

Participant characteristics

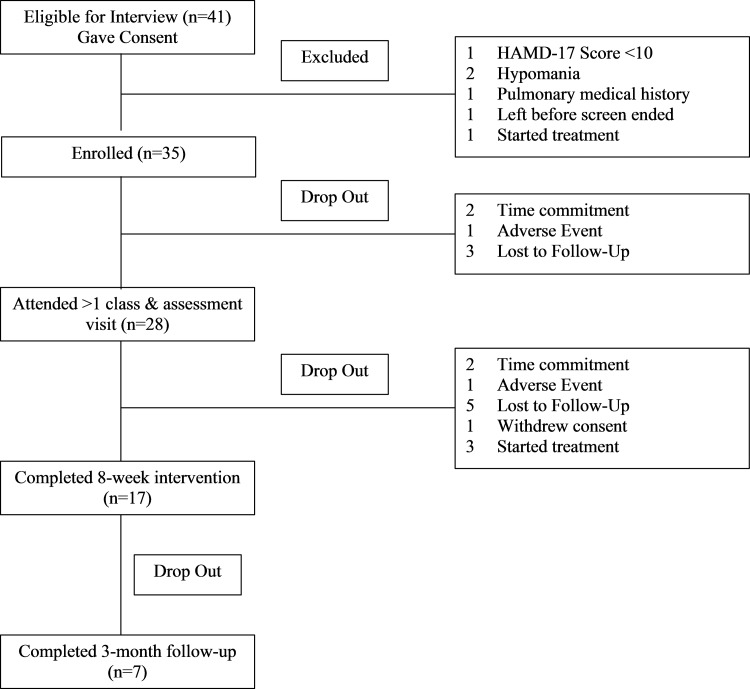

A summary of participant flow is as follows: 41 gave consent, 35 met study eligibility, and 28 attended at least 1 yoga class and a subsequent assessment visit (Fig. 1). Participant demographics and baseline clinical characteristics (including psychotropic medication use) are provided in Table 2. Twenty-six participants (92.9%) met criteria for current MDD based on the SCID. The two participants who did not meet criteria for MDD scored 11 and 12 on the HRSD-17 and 5 and 18 on the BDI. Both met criteria for current minor depressive disorder and had met criteria for MDD in the past. At screening, average depression severity was in the moderate range, based on clinician- and self-ratings. Table 3 provides means and standard deviations (SDs) for study variables at each time point.

FIG. 1.

CONSORT chart. CONSORT, Consolidated Standards of Reporting trials.

Table 2.

Baseline Demographics and Clinical Characteristics of the Sample (N = 28)

| Characteristic | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | Mean (SD) | |||

| Age | 19–64 | 36.46 (13.57) | ||

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 8 | 28.6 |

| Female | 20 | 71.4 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 18 | 64.3 |

| African American | 5 | 17.9 |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 1 | 3.6 |

| More than one selected | 3 | 10.7 |

| No response | 1 | 3.6 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic/Latina | 11 | 39.3 |

| Non-Hispanic/Latina | 14 | 50.0 |

| No response | 3 | 10.7 |

| Education | ||

| Graduate | 7 | 25.0 |

| Part graduate/professional school | 3 | 10.7 |

| Undergraduate | 9 | 32.1 |

| Part undergraduate/2-year degree | 6 | 21.4 |

| High school | 2 | 7.1 |

| No response | 1 | 3.6 |

| Marital status | ||

| Never married | 14 | 50.0 |

| Married or living with someone | 6 | 21.4 |

| Separated or divorced | 3 | 10.7 |

| No response | 5 | 17.9 |

| Employment | ||

| Full time | 13 | 46.4 |

| Part time | 4 | 14.3 |

| Student | 5 | 17.9 |

| Not currently employed (e.g., laid off, leave of absence, homemaker, retired) | 6 | 21.4 |

| Current psychotropic medication use (i.e., ≥1 of the following: fluoxetine, bupropion, mirtazapine, lamotrigine, venlafaxine, citalopram, duloxetine) | 6 | 21.4 |

| Anxiety disorder diagnosis, per SCID criteria16 | ||

| One diagnosis | 7 | 25.0 |

| Two diagnoses | 2 | 7.1 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 4 | 14.3 |

| Panic disorder | 3 | 10.7 |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 1 | 3.6 |

| Social anxiety disorder | 1 | 3.6 |

| Specific phobia | 1 | 3.6 |

| Anxiety disorder, NOS | 1 | 3.6 |

NOS, not otherwise specified; SD, standard deviation; SCID, Structured Clinical Interview for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition.

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics at Each Assessment Point

| Screen (n = 28) | Week 1 (n = 27) | Week 3 (n = 23) | Week 5 (n = 19) | Week 8 (Post-Tx; n = 17) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Total BY classes attended | 8.71 (5.45) | ||||

| Clinician-rated depression (HRSD-17) | 17.68 (4.78) | 13.56 (5.47) | 11.74 (5.88) | 12.63 (15.72) | 8.18 (5.76) |

| Self-reported depression (BDI) | 20.44 (7.34) | 17.27 (7.46) | 14.10 (9.23) | 12.11 (9.96) | 10.12 (10.41) |

| Hopelessness (BHS) | 9.54 (4.89) | 8.27 (4.58) | 7.64 (5.83) | 6.63 (6.19) | 7.47 (6.72) |

| Anxiety (BAI) | 12.21 (8.06) | 10.81 (7.21) | 8.33 (6.94) | 6.28 (6.19) | 6.06 (6.78) |

| Cognitive and physical functioning (CPFQ) | 25.50 (6.08) | 22.92 (6.10) | 21.81 (6.78) | 19.17 (7.25) | 17.38 (5.73) |

| Quality of life (QLESQ)a | 37.50 (5.59) | 39.35 (7.94) | 44.86 (9.50) | 44.05 (14.14) | 45.88 (13.08) |

Higher scores indicate improvement.

BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; BHS, Beck Hopelessness Scale; BY, Bikram Yoga; CPFQ, Cognitive and Physical Functioning Questionnaire; HRSD-17, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; QLESQ, Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire; SD, standard deviation.

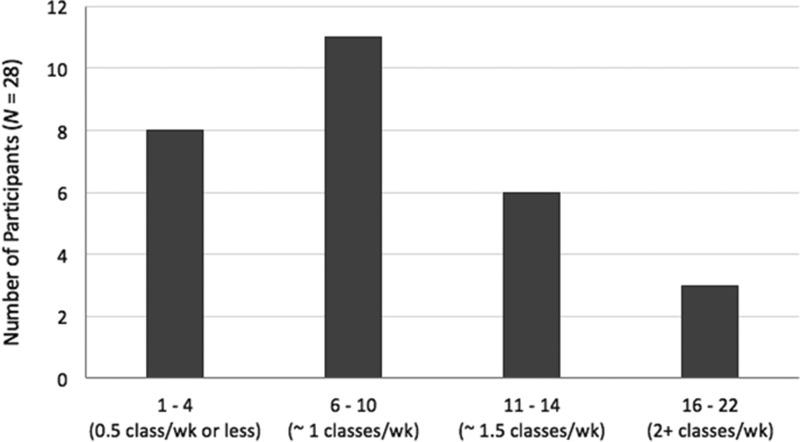

Feasibility: Retention and adherence to Bikram yoga intervention

Participants attended between 1 and 22 (M = 8.71, SD = 5.45) classes over the 8-week intervention period. Only 3 (10.7%) participants met or exceeded the recommended study dose of 16 sessions over 8 weeks (Fig. 1). Intervention retention rates by week, along with the actual number of participants who attended at least one BY class, are shown in Figure 2. Reasons for dropouts (per clinician study notes): (1) worsening of pre-existing condition (i.e., shoulder, back, post-traumatic stress disorder [PTSD] symptoms); (2) time commitment (i.e., started school, work stress), (3) difficulty adjusting to the practice; (4) change in treatment regimen (e.g., therapy initiated, aripiprazole augmentation (caused increased heat sensitivity), (5) adverse reactions to BY (e.g., dehydration symptoms [lightheadedness], hypoglycemia); (6) did not like BY (“did not find it relaxing”); (7) difficulty getting to yoga (i.e., due to winter weather); and (8) depressive symptoms interfered (e.g., motivation and cognitive impairment).

FIG. 2.

Number of classes attended by study participants over the 8-week intervention. Participants were asked to attend at least two classes per week. BY, Bikram Yoga; wk, week.

Main effects of change in depression and related symptoms

Primary depression measures

Clinician-rated HRSD-17 depression severity decreased significantly from baseline to week 8 [b = −1.71, t(82) = −3.05, p = 0.003, 95% confidence interval, CI (−2.83 to −0.59), dGLMM = 1.43; dRM = 1.35]. Self-reported depression severity, per the BDI, significantly decreased over time [b = −2.41, t(92) = −5.00, p < 0.001, 95% CI (−3.37 to −1.46), dGLMM = 1.31; dRM = 1.10].

Secondary depression measures

There were significant changes over time in each of the secondary outcome measures. Participants' self-reported hopelessness [b = −0.70, t(90) = −2.29, p = 0.024, 95% CI (−1.31 to −0.09), dGLMM = 0.57; dRM = 0.36], anxiety [b = −1.58, t(78) = −3.67, p < 0.001, 95% CI (−2.43 to −0.72), dGLMM = 0.78; dRM = 1.28], quality of life [b = 1.80, t(91) = 2.78, p = 0.007, 95% CI (0.51 to 3.08), dGLMM = 1.29; dRM = 0.71], and functional impairment [b = −2.04, t(95) = −5.72, p < 0.001, 95% CI (−2.74 to −1.33), dGLMM = 1.34; dRM = 1.30] each improved over the course of the intervention period.

Effects of degree of yoga attendance on symptom change

Improvements in self-reported anxiety and cognitive and physical functioning did not vary by number of yoga classes attended [BAI: b = −0.29, t(74) = −0.63, p = 0.532; CPFQ: b = −0.11, t(92) = −0.30, p = 0.769], and a nonsignificant effect of attendance was also observed for reduction in clinician-rated depression symptoms [b = −1.10, t(79) = −1.89, p = 0.063]. More frequent attendance was significantly associated with greater improvements in self-reported depression [b = −1.80, t(87) = −3.74, p < 0.001], hopelessness [b = −0.66, t(84) = −2.11, p = 0.038], and quality of life [b = 2.39, t(90) = 3.61, p = 0.001].

To estimate the frequency of yoga required for outcome improvement, models were re-run with the attendance variable centered at four different attendance rates: (1) once every 2 weeks (4 classes in total), (2) once a week (8 classes in total), (3) 1.5 classes per week (12 classes in total), and (4) 2 classes per week (16 classes in total).28,29 Significant improvements in clinician-rated depression [b = −1.22, t(82) = −2.02, p = 0.047] and self-reported depression [b = −1.60, t(89) = −3.24, p = 0.002] were achieved by participants who attended yoga at least once per week. Self-reported hopelessness [b = −0.89, t(86) = −2.83, p = 0.006] and quality of life [b = 2.64, t(91) = 4.03, p < 0.001] significantly improved among participants who attended at least 1.5 classes per week (12 sessions total).

Treatment response and remission rates (per HRSD-17)

Response and remission rates were examined based on last assessments in all subjects who completed an assessment at week 3 and/or later (i.e., participants who did not have assessments for weeks 3, 5, and 8 were excluded). Twenty-three participants were analyzed, using data from their last assessment point: week 8 (n = 17), week 5 (n = 3), or week 3 (n = 3). Of these 23 participants, 12 (52.2%) were responders (≥50% reduction in total HRSD-17 score) and 13 (56.5%) were remitters (final HRSD-17 score ≤7).

Among “low attenders” (i.e., <5 classes attended over 8 weeks; n = 3), all dropped out of the yoga intervention by the start of week 3, and none responded or remitted. Among “average attenders” (6–10 classes; n = 11), five responded (45.5%) and six remitted (54.5%). Among “above average attenders” (11–14 classes total; n = 6), four (66.7%) responded and five (83.3%) remitted. All three (100%) high attenders (18–20 classes total) responded and two (66.7%) remitted.

Intervention effects for participants with MDD (N = 26)

Since 26 of 28 subjects met criteria for MDD, a post hoc analysis of these subjects was conducted. When excluding the two participants who did not meet baseline criteria for MDD, each of the main effects of time held. Thus, the findings for participants meeting criteria for MDD (n = 26) were identical to those for the entire sample (N = 28).

Discussion

This is the first study to test heated yoga for a moderately clinically depressed population. This unfunded and uncontrolled pilot study utilized an open-label design to determine whether future more rigorous investigation with an RCT was warranted. This study evaluated BY as it is naturally delivered in the community, without modification or adjustment for clinically depressed individuals (of note: this manuscript only included individuals who completed at least one BY class and subsequent assessment visit). Almost 50% of participants completed the 8-week intervention (attended BY classes through week 8), and nearly 30% attended at least 75% of the prescribed 16 classes over 8 weeks. However, only three participants completed the full dose of the intervention. Overall our findings support the potential for heated yoga to be further evaluated as a potential intervention for depression as it was associated with a reduction in depressive symptoms, with the caveat that acceptability and feasibility require further attention when designing follow-up studies.

Improvements in symptoms were observed in both clinician-rated (HRSD-17) and self-rated (BDI-I) depression scales over the course of the intervention. Significant improvements were also found for secondary outcomes including hopelessness, anxiety, quality of life, and cognitive and physical functioning. Effect sizes were robust for most clinical outcome measures, with dGLMM values ranging from 0.57 to 1.43. This finding is encouraging, given that previous meta-analyses have suggested effect sizes in the range of 0.3–0.4 for antidepressant medications.30 More frequent yoga attendance was associated with greater symptom reductions across most outcomes. Despite this apparent dose-response effect, yoga practice frequency was not randomized, and therefore expectation effects cannot be ruled out. It is also possible that individuals with improving depression were better able to maintain frequent attendance. As reviewed in the Introduction section, these findings are consistent with previous literature supporting both nonheated yoga,4,6 as well as WBH7 as potential treatments for depression, and also support the limited extant literature of heated yoga's effect on stress.11,13

Almost half of the subjects completed the 8-week intervention, and close to a third attended three quarters or more of the prescribed 16 classes over 8 weeks. A meta-analysis of 115 studies (N = 20,995) of dropout from cognitive behavioral therapy found the average weighted dropout was 15.9% pretreatment and 26.2% during treatment, with depression having the hightest attrition rate.31 STAR*D, the largest clinical trial of depression, cited a 26% attrition-rate as a significant issue.32 However, the percentage of participants who completed primary study endpoints was significantly lower in this study than in two recent studies of nonheated yoga in subjects with MDD or resistant depression at 94% and 85%, respectively.33,34 The retention rate in this study was lower than in the other RCT of heated yoga for mental health symptoms, which was 81%11——though, this study did not select for clinically significant depressive symptoms. Despite the acceptability and feasibility challenges presented in the present study—such as those listed in the Results (e.g., worsening of pre-existing condition, time commitment, difficulty adjusting to the practice, adverse reactions to BY)—adherence was sufficient to be associated with an antidepressant effect. In essence, even minimal attendance was potentially beneficial, which may encourage participation by individuals who may be reticent about having to make a substantial time commitment. We are currently following up on these findings in a larger, more rigorous study that will yield new insights into feasibility and maximization of treatment adherence with BY in a similar population (NIH/NCCIH K23 AT0080430A1). The findings from this pilot study informed the design of this next-step study—for example, to enhance feasibility and acceptability participants now receive phone calls from the Principal Investigator (PI) on the nonassessment weeks to assess for safety, depressive symptoms, and answer questions; the hope is that these calls will also increase the accountability and connection to the study.

The mechanism by which BY exerts effects on depression remains speculative. Some MDD patients may have abnormal thermoregulation—that is, increased core body temperature and difficulty regulating temperature through perspiration.7,9,35 In an RCT on WBH for MDD (core body temperature was increased to 101.3°F), normalization of thermoregulatory functions occured after one session of WBH.7 One study suggested that BY increased core body temperature by 1.0°F–1.8°F, with more experienced practitioners demontrating greater temperature increases.36 A case study used an ingestible thermometer capsule to measure core body temperature during a BY class and found the maximum core body temperature to be 101.6°F,36 comparable to the core body termperature in WBH.7

Strengths

This is the first known study to examine the acceptability, feasibility, and associated reductions in depressive symptoms of heated yoga for individuals with clinically significant depression. Outcome measures were conducted with validated clinician- and self-rated instruments. Tracking of attendance allowed correlation between dose and depressive symptom improvement. BY classes were conducted by certified instructors, and delivered in real-world community studios that permitted a wide range of class options (time/day availability), increasing feasibility and generalizability.

Limitations

This was a small uncontrolled and unblinded pilot study. Those who did not take a yoga class were excluded from analyses, which likely self-selected for those with more motivation and/or ability to attend this intervention. Expectations for yoga were not collected pre-treatment which is also a limitation. An exit interview was only collected at 3-month follow-up (not at early termination) where attrition made data uninformative. Consistent with the national trend in yoga users, this sample consisted predominantly of white college educated females,37,38 and this limits generalizability with regard to depressed populations in general.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate heated yoga's association with decreased depressive symptoms in a clinically depressed sample. There were significant overall effects across all outcome variables, including depression symptom severity, hopelessness, anxiety, quality-of-life, and cognitive and physical functioning. Feasibility of yoga as an intervention for depression requires further characterization, based on the lower completion rate observed relative to other yoga studies. Replication of these preliminary findings in an RCT is warranted, in addition to comparative studies of heated versus nonheated forms of yoga and studies exploring core body temperature as a mechanism of change in heated yoga.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the following grants: National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) K23-Award (K23 AT0080430A1; MBN), NCCIH Loan Repayment Program (MBN). Our gratitude to Jill, Tomo, and Brad Koontz who provided the yoga classes free of charge to study participants through Bikram Yoga Boston and to Lucas Lambert who provided yoga classes free of charge to study participants through Bikram Yoga Cambridge.

Author Disclosure Statement

Dr. Miller has received study medication at no cost from Marinus Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Uebelacker's spouse is employed by Abbvie Pharmaceuticals.

Dr. Fava:

Research Support:

Abbott Laboratories; Acadia Pharmaceuticals; Alkermes, Inc.; American Cyanamid; Aspect Medical Systems; AstraZeneca; Avanir Pharmaceuticals; AXSOME Therapeutics; Biohaven; BioResearch; BrainCells Inc.; Bristol-Myers Squibb; CeNeRx BioPharma; Cephalon; Cerecor; Clarus Funds; Clexio Biosciences; Clintara, LLC; Covance; Covidien; Eli Lilly and Company; EnVivo Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Euthymics Bioscience, Inc.; Forest Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; FORUM Pharmaceuticals; Ganeden Biotech, Inc.; GlaxoSmithKline; Harvard Clinical Research Institute; Hoffman-LaRoche; Icon Clinical Research; Indivior; i3 Innovus/Ingenix; Janssen R&D, LLC; Jed Foundation; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development; Lichtwer Pharma GmbH; Lorex Pharmaceuticals; Lundbeck Inc.; Marinus Pharmaceuticals; MedAvante; Methylation Sciences Inc; National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia & Depression (NARSAD); National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM); National Coordinating Center for Integrated Medicine (NiiCM); National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA); National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH); Neuralstem, Inc.; NeuroRx; Novartis AG; Organon Pharmaceuticals; Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development, Inc.; PamLab, LLC.; Pfizer Inc.; Pharmacia-Upjohn; Pharmaceutical Research Associates., Inc.; Pharmavite® LLC; PharmoRx Therapeutics; Photothera; Reckitt Benckiser; Roche Pharmaceuticals; RCT Logic, LLC (formerly Clinical Trials Solutions, LLC); Sanofi-Aventis US LLC; Shenox Pharmaceuticals, LLC; Shire; Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Stanley Medical Research Institute (SMRI); Synthelabo; Taisho Pharmaceuticals; Takeda Pharmaceuticals; Tal Medical; VistaGen; Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories

Advisory Board/Consultant:

Abbott Laboratories; Acadia; Affectis Pharmaceuticals AG; Alkermes, Inc.; Amarin Pharma Inc.; Aspect Medical Systems; AstraZeneca; Auspex Pharmaceuticals; Avanir Pharmaceuticals; AXSOME Therapeutics; Bayer AG; Best Practice Project Management, Inc.; Biogen; BioMarin Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; BioXcel Therapeutics; Biovail Corporation; Boehringer Ingelheim; Boston Pharmaceuticals; BrainCells Inc; Bristol-Myers Squibb; CeNeRx BioPharma; Cephalon, Inc.; Cerecor; Clexio Biosciences; CNS Response, Inc.; Compellis Pharmaceuticals; Cypress Pharmaceutical, Inc.; DiagnoSearch Life Sciences (P) Ltd.; Dinippon Sumitomo Pharma Co. Inc.; Dov Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Edgemont Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eisai Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; EnVivo Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; ePharmaSolutions; EPIX Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Euthymics Bioscience, Inc.; Fabre-Kramer Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Forest Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Forum Pharmaceuticals; GenOmind, LLC; GlaxoSmithKline; Grunenthal GmbH; Indivior; i3 Innovus/Ingenis; Intracellular; Janssen Pharmaceutica; Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development, LLC; Knoll Pharmaceuticals Corp.; Labopharm Inc.; Lorex Pharmaceuticals; Lundbeck Inc.; Marinus Pharmaceuticals; MedAvante, Inc.; Merck & Co., Inc.; MSI Methylation Sciences, Inc.; Naurex, Inc.; Navitor Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Nestle Health Sciences; Neuralstem, Inc.; Neuronetics, Inc.; NextWave Pharmaceuticals; Novartis AG; Nutrition 21; Orexigen Therapeutics, Inc.; Organon Pharmaceuticals; Osmotica; Otsuka Pharmaceuticals; Pamlab, LLC.; Perception Neuroscience; Pfizer Inc.; PharmaStar; Pharmavite® LLC.; PharmoRx Therapeutics; Polaris Partners; Praxis Precision Medicines; Precision Human Biolaboratory; Prexa Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; PPD; PThera, LLC; Purdue Pharma; Puretech Ventures; PsychoGenics; Psylin Neurosciences, Inc.; RCT Logic, LLC (formerly Clinical Trials Solutions, LLC); Relmada Therapeutics, Inc.; Rexahn Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Ridge Diagnostics, Inc.; Roche; Sanofi-Aventis US LLC.; Sepracor Inc.; Servier Laboratories; Schering-Plough Corporation; Shenox Pharmaceuticals, LLC; Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Somaxon Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Somerset Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Sunovion Pharmaceuticals; Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Synthelabo; Taisho Pharmaceuticals; Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited; Tal Medical, Inc.; Tetragenex; Teva Pharmaceuticals; TransForm Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Transcept Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Usona Institute, Inc.; Vanda Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Versant Venture Management, LLC; VistaGen

Speaking/Publishing:

Adamed, Co; Advanced Meeting Partners; American Psychiatric Association; American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology; AstraZeneca; Belvoir Media Group; Boehringer Ingelheim GmbH; Bristol-Myers Squibb; Cephalon, Inc.; CME Institute/Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; Forest Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; GlaxoSmithKline; Imedex, LLC; MGH Psychiatry Academy/Primedia; MGH Psychiatry Academy/Reed Elsevier; Novartis AG; Organon Pharmaceuticals; Pfizer Inc.; PharmaStar; United BioSource,Corp.; Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories.

Stock/Other Financial Options:

Equity Holdings: Compellis; PsyBrain, Inc.

Royalty/patent, other income:

Patents for Sequential Parallel Comparison Design (SPCD), licensed by MGH to Pharmaceutical Product Development, LLC (PPD) (US_7840419, US_7647235, US_7983936, US_8145504, US_8145505); and patent application for a combination of Ketamine plus Scopolamine in Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), licensed by MGH to Biohaven. Patents for pharmacogenomics of Depression Treatment with Folate (US_9546401, US_9540691).

Copyright for the MGH Cognitive & Physical Functioning Questionnaire (CPFQ), Sexual Functioning Inventory (SFI), Antidepressant Treatment Response Questionnaire (ATRQ), Discontinuation-Emergent Signs & Symptoms (DESS), Symptoms of Depression Questionnaire (SDQ), and SAFER; Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; Wolkers Kluwer; World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte.Ltd.

Dr. Alpert has received research support from Abbott Laboratories, Alkermes, Lichtwer Pharma GmbH, Lorex Pharmaceuticals; Aspect Medical Systems, Astra-Zeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, Cephalon, Cyberonics, Eli Lilly & Company, Forest Pharmaceuticals, Inc., GlaxoSmithkline, J & J Pharmaceuticals, National Institutes of Health, NARSAD, Novartis, Organon, Inc., Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, PamLab, LLC, Pfizer, Inc., Pharmavite, Roche, Sanofi/Synthelabo, Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories; has served on the advisory board or as a consultant to Consulting Medical Assocites, Eli Lilly & Company, Luye Pharmaceuticals, PamLab, LLC, and Pharmavite, LLC; and has received speaking/publishing honoraria from the MGH Psychiatry Academy, Reed Medical Education, Primedia, Nevada Psychiatric Association, American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology, American Psychiatric Association, Belvoir Media Group, Eli Lilly & Company, Xian-Janssen, Organon, Psicofarma, Institut La Conference Hippocrate.port from Abbott Laboratories, Alkermes, Lichtwer Pharma GmbH, Lorex Pharmaceuticals; Aspect Medical Systems, Astra-Zeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, Cephalon, Cyberonics, Eli Lilly & Company, Forest Pharmaceuticals Inc., GlaxoSmithkline, J & J Pharmaceuticals, National Institutes of Health, NARSAD, Novartis, Organon, Inc., Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, PamLab, LLC, Pfizer, Inc., Pharmavite, Roche, Sanofi/Synthelabo, Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories; has served on the advisory board or as a consultant to Consulting Medical Assocites, Eli Lilly & Company, Luye Pharmaceuticals, PamLab, LLC, and Pharmavite, LLC; and has received speaking/publishing honoraria from the MGH Psychiatry Academy, Reed Medical Education, Primedia, Nevada Psychiatric Association, American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology, American Psychiatric Association, Belvoir Media Group, Eli Lilly & Company, Xian-Janssen, Organon, Psicofarma, Institut La Conference Hippocrate. Dr. Mischoulon has received research support from Nordic Naturals. He has provided unpaid consulting for Pharmavite, LLC and Gnosis USA, Inc. He has received honoraria for speaking from the Massachusetts General Hospital Psychiatry Academy, Harvard Blog, PeerPoint Medical Education Institute, LLC, and Blackmores. He has received royalties from Lippincott Williams & Wilkins for published book “Natural Medications for Psychiatric Disorders: Considering the Alternatives.” All other authors have no competing financial interests.

References

- 1. Baldessarini RJ, Forte A, Selle V, et al. Morbidity in depressive disorders. Psychother Psychosom 2017;86:65–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, et al. Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: A STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry 2006;163:1905–1917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kirsch I, Huedo-Medina TB, Pigott HE, Johnson BT. Do outcomes of clinical trials resemble those “real world” patients? A reanalysis of the STAR*D antidepressant data set. Psychol Conscious Theory Res Pract 2018;5:339–345 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cramer H, Lauche R, Langhorst J, Dobos G. Yoga for depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety 2013;30:1068–1083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cramer H. A systematic review of yoga for major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord 2017;213:70–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Uebelacker LA, Epstein-Lubow G, Gaudiano BA, et al. Hatha yoga for depression: Critical review of the evidence for efficacy, plausible mechanisms of action, and directions for future research. J Psychiatr Pract 2010;16:22–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Janssen CW, Lowry CA, Mehl MR, et al. Whole-body hyperthermia for the treatment of major depressive disorder: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2016;73:789–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hanusch K-U, Janssen CH, Billheimer D, et al. Whole-body hyperthermia for the treatment of major depression: Associations with thermoregulatory cooling. Am J Psychiatry 2013;170:802–804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hale MW, Raison CL, Lowry CA. Integrative physiology of depression and antidepressant drug action: Implications for serotonergic mechanisms of action and novel therapeutic strategies for treatment of depression. Pharmacol Ther 2013;137:108–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hewett ZL, Ransdell LB, Gao Y, et al. An examination of the effectiveness of an 8-week Bikram Yoga Program on Mindfulness, Perceived Stress, and Physical Fitness. J Exerc Sci Fit 2011;9:87–92 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hopkins LB, Medina JL, Baird SO, et al. Heated hatha yoga to target cortisol reactivity to stress and affective eating in women at risk for obesity-related illnesses: A randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol 2016;84:558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Medina J, Hopkins L, Powers M, et al. The effects of a hatha yoga intervention on facets of distress tolerance. Cogn Behav Ther 2015;44:288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hewett ZL, Pumpa KL, Smith CA, et al. Effect of a 16-week Bikram yoga program on perceived stress, self-efficacy and health-related quality of life in stressed and sedentary adults: A randomised controlled trial. J Sci Med Sport 2017;21:352–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960;23:56–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Choudhury B. Bikram Yoga: The Guru Behind Hot Yoga Shows the Way to Radiant Health and Personal Fulfillment. New York, NY: Harper Collins Publishing, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 16. First M, Gibbon M, Spitzer R, et al. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Non-Patient Edition (SCID-I/NP). New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Williams JB. A structured interview guide for the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988;45:742–747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mischoulon D, Fava M. Diagnostic rating scales and psychiatric instruments. In: Stern TA, Herman JB, Rubin DH, eds. Psychiatry Update and Board Preparation, 4th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 2018:355–363 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, et al. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1961;4:561–571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Roffman J, Mischoulon D, Stern T. Diagnostic rating scales and laboratory tests. In: Stern TA, Freudenreich O, Smith FA, Fricchione GL, Rosenbaum JF, eds. Massachusetts General Hospital Handbook of General Hospital Psychiatry, 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier, 2018:59–68 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Beck AT, Weissman A, Lester D, Trexler L. The measurement of pessimism: The hopelessness scale. J Consult Clin Psychol 1974;42:861–865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Beck AT, Steer RA. Manual for the Beck Anxiety Inventory. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation, 1990 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Endicott J, Nee J, Harrison W, Blumenthal R. Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire: A new measure. Psychopharmacol Bull 1993;29:321–326 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fava M, Iosifescu DV, Pedrelli P, Baer L. Reliability and validity of the Massachusetts General Hospital cognitive and physical functioning questionnaire. Psychother Psychosom 2009;78:91–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hamer RM, Simpson PM. Last observation carried forward versus mixed models in the analysis of psychiatric clinical trials. Am J Psychiatry 2009;166:639–641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Feingold A. A regression framework for effect size assessments in longitudinal modeling of group differences. Rev Gen Psychol 2013;17:111–121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Morris SB, DeShon RP. Combining effect size estimates in meta-analysis with repeated measures and independent-groups designs. Psychol Methods 2002;7:105–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Edwards JR, Lambert LS. Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychol Methods 2007;12:1–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tein J-Y, Sandler IN, MacKinnon DP, Wolchik SA. How did it work? Who did it work for? Mediation in the context of a moderated prevention effect for children of divorce. J Consult Clin Psychol 2004;72:617–624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Vöhringer PA, Ghaemi SN. Solving the antidepressant efficacy question: Effect sizes in major depressive disorder. Clin Ther 2011;33:B49–B61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fernandez E, Salem D, Swift JK, Ramtahal N. Meta-analysis of dropout from cognitive behavioral therapy: Magnitude, timing, and moderators. J Consult Clin Psychol 2015;83:1108–1122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sinyor M, Schaffer A, Levitt A. The sequenced treatment alternatives to relieve depression (STAR*D) trial: A review. Can J Psychiatry 2010;55:126–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Streeter CC, Gerbarg PL, Whitfield TH, et al. Treatment of major depressive disorder with iyengar yoga and coherent breathing: A randomized controlled dosing study. J Altern Complement Med 2017;23:201–207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Uebelacker LA, Tremont G, Gillette LT, et al. Adjunctive yoga v. health education for persistent major depression: A randomized controlled trial. Psychol Med 2017;47:2130–2142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Raison CL, Hale MW, Williams LE, et al. Somatic influences on subjective well-being and affective disorders: The convergence of thermosensory and central serotonergic systems. Front Psychol 2014;5:1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fritz ML, Grossman AM, Mukherjee A, et al. Acute metabolic, cardiovascular, and thermal responses to a single session of Bikram yoga: 593 Board #8 May 28, 3. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2014;46:146–147 [Google Scholar]

- 37. Birdee GS, Legedza AT, Saper RB, et al. Characteristics of yoga users: Results of a national survey. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23:1653–1658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Saper RB, Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, et al. Prevalence and patterns of adult yoga use in the United States: Results of a national survey. Altern Ther Health Med 2004;10:44–49 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]