Abstract

Children in immigrant families are twice as likely to be uninsured as their counterparts, and states may influence these inequities by facilitating or restricting immigrant families’ access to coverage. Our objective was to measure differences in insurance by mother’s documentation status among a nationally representative sample of US-born children in immigrant families and to examine the role of state-level immigrant health care policy—namely, state-level immigrant access to prenatal coverage. Compared with US-born children in immigrant families with citizen mothers, children with undocumented immigrant mothers had a 17.0 percentage point (P < .001) higher uninsurance rate (8.8 percentage points higher in adjusted models, P < .05). However, in states with nonrestrictive prenatal coverage for immigrants, there were no differences in children’s insurance by mother’s documentation status, while large inequities were observed within states with restrictive policies. Our findings demonstrate the potential for state-level immigrant health care policy to mitigate or exacerbate inequities in children’s insurance.

Keywords: Access to care, inequities, immigrant policy, healthcare policy

Health insurance disparities between children in immigrant families and their peers are substantial and persistent.1-4 Despite major gains,1,5 uninsurance among children in immigrant families is almost twice that of children with US-born parents.6 The 18 million children with immigrant parents, the majority of whom are US-born citizen children, make up 26% of all children in the United States,7 but make up nearly half of the remaining uninsured children.8

Most children with immigrant parents are in mixed-status families, or families where at least one parent is a noncitizen and one child is a citizen.9 Citizen children in mixed-status families are more likely to lack coverage than children with citizen parents.6 Citizen children with citizen parents may face fewer obstacles, while citizen children with noncitizen parents are more likely to face limited resources and greater vulnerability.10-14 Beyond parental citizenship lies an important, often masked distinction whose effect on insurance has yet to be fully examined in a nationally representative sample: Over 30% of US-born children in immigrant families have at least one parent who is an undocumented immigrant,7,15,16 a critical factor that may reveal, in fact, several levels of access among citizen children.

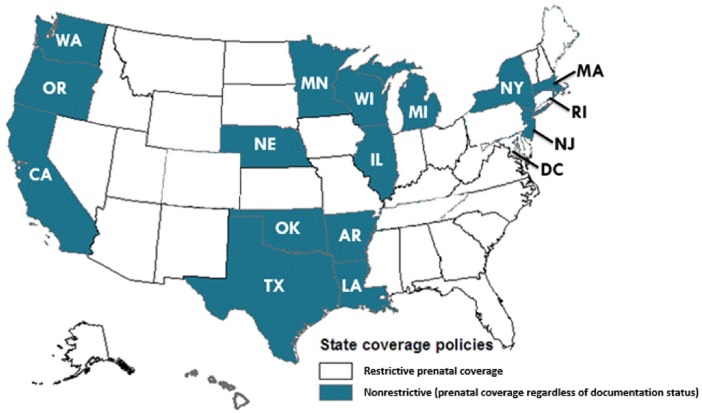

In the face of federal restrictions, such as the Personal Responsibility & Welfare Reform Act of 1996, states play an ever-increasing role in shaping immigrants’ access to insurance.17-20 In particular, states have a greater role in determining eligibility for immigrants excluded from federal programs. Although these state-level determinations do not directly affect US-born children’s eligibility, certain policies may help shape the likelihood that immigrant parents are able to enroll their children. One such key policy is the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) Unborn Child Option of 2002.21 This federal regulation allows states the option of receiving a 100% federal match to provide prenatal coverage to income-eligible pregnant women regardless of their immigration status. Thus, it represents a critical pathway to prenatal care for undocumented immigrant mothers in particular. The only other alternative is Emergency Medicaid,18 which covers only labor and delivery and not the prenatal care that is essential for the health of the mother and her child. This CHIP Option has been found to be associated with a higher probability of Medicaid enrollment during pregnancy.22 Despite the federal match and the program’s effectiveness in enrolling mothers, as of 2008 only 16 states plus the District of Columbia fund any type of coverage for pregnant women regardless of documentation status (see Figure 1; note: only one state [Missouri in 2015] has expanded access since 2008).23,24

Figure 1.

States with prenatal Medicaid/CHIP coverage available regardless of documentation status (2008).

Note: Tennessee had taken up the Unborn Child CHIP Option as of 2008 but required proof of immigration status, thus limiting coverage to citizen and legal permanent residents. Therefore, Tennessee was not considered nonrestrictive in our analysis. The District of Columbia, New Jersey, and New York use local/state funds to provide coverage regardless of documentation status.23,24

Unequal access to or delayed initiation of prenatal care can have health consequences for both mothers and children and also excludes mothers from an important opportunity to connect to a wealth of resources beyond health care.25-29 Providing early and comprehensive prenatal care may also help facilitate children’s insurance. Since immigrant mothers are themselves eligible to enroll in Medicaid/CHIP for the duration of the pregnancy, once their children are born they may be more likely to know how and where to enroll them. In qualitative work with undocumented immigrant mothers in one state that offers nonrestrictive prenatal coverage, mothers universally expressed the importance of this coverage in mitigating early on any fear or hesitation they initially felt about enrolling in Medicaid/CHIP, and connecting mothers and families to resources to subsequently enroll their children.30 This evidence suggests that insurance disparities for US-born children in mixed-status families may be mitigated by the availability of this pathway to coverage for mothers and families.30 A recent body of literature has shown the strong effects of parents’ own access to coverage on facilitating coverage for their children. For example, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and other Medicaid expansions led to increases in enrollment among the children of eligible adults,31,32 but the mechanism we assess here has yet to be explored.

Peer-reviewed studies that have broadly examined insurance disparities for children in mixed-status families have exposed previously masked disparities, but these studies have only examined this in certain states or localities.33-36 Thus, our first objective is to measure differences in children’s uninsurance by parental documentation status among US-born children of immigrants in a nationally representative survey. The tremendous state-level variation in immigrant health care policy also warrants an examination of how this variation impedes or facilitates coverage for children in mixed-status families. We probe the significance of one such policy, assessing whether the Unborn Child CHIP Option (or, broadly, availability of prenatal coverage regardless of documentation status) mitigates differences in children’s coverage by parental documentation status. Our sample and methodology fill several important gaps.

First, we focus on insurance among US-born citizen children to identify differences across parental status alone, taking advantage of measures of children’s birthplace/citizenship first introduced in the 2004 Panel of the Survey of Income & Program Participation (SIPP). Past research on parental documentation status in the SIPP has either not included children’s citizenship37 or imputed it based on parental characteristics.38 Second, by including both parents’ status in our model (where available), we account for differences among children with 1 undocumented immigrant parent and 2 undocumented immigrant parents. Finally, we assess the potential of a critical, yet under implemented, immigrant health care policy to reduce inequities for children in mixed-status families. Given the current hostile sociopolitical environment facing immigrant families, such as ramped-up immigration enforcement and deportations,39-42 it is especially important to understand the impact of immigrant health care policies.

Methods

The SIPP is an in-person and telephone survey, and the only nationally representative survey with measures of documentation status. The iteration we used followed individuals in the civilian noninstitutionalized population for 3 to 6 years in 4-month waves. Our sample includes 4080 US-born children in immigrant families from a cross-section in reference to December 2008 (from the 2008 Panel’s second wave). Children of immigrants had parents 18 or older who were born outside the United States. The 2008 Panel is the most recent SIPP panel with documentation status measures and only one state (Missouri in 2015) has taken up the CHIP Option since 2008.

Measures

Children’s Health Insurance

We identified uninsured children as those without any source of coverage (employer-sponsored insurance [ESI], public [Medicaid/CHIP], or other private) during the observed reference month.

Parental Documentation Status

To estimate differences by parental documentation status and account for differential access to resources between 1- and 2-parent families,13 we observe both parents’ status (except for children in 1-parent families). Children in 1-parent families may have a parent outside the sampled household who provides resources, but the SIPP does not capture any data for these parents. Core waves asked all household members about nativity and citizenship. The migration history topical module (Wave 2) asked noncitizens age 15+ whether they entered the United States as legal permanent residents—and if not whether they have adjusted their status. We categorized parents born outside the United States as naturalized citizens, legal permanent residents, or undocumented immigrants. We also included some US-born citizen parents (non-immigrant parents in families with at least one immigrant parent). Legal permanent residents either had this status when they arrived in the United States, or did not enter as legal permanent residents but had since adjusted. A limited number of observations were also assigned as legal permanent residents based on common-practice logical edits.18 Similar to the approach of immigration demographers and the SIPP measure’s use in peer-reviewed studies, remaining noncitizens who did not enter as legal permanent residents and had not since adjusted were categorized as undocumented immigrants.37,38,43 This may include a small proportion of immigrants on temporary visas. However, we would expect their children to be more likely to be insured, which would mean differences we estimate by parental documentation status are conservative. Twenty-one children with missing parental documentation status were excluded from the sample.

We assigned mother’s and father’s documentation status as follows: (1) citizen, (2) legal permanent resident, or (3) undocumented immigrant. Our primary focus is mother’s status, given the nature of the prenatal policy we examine, but we also include father’s documentation status.

A potential limitation of our documentation status measure is the fact that the Census Bureau imputed values (primarily through hotdeck) for 15.0% of respondents born outside the United States who did not respond to documentation status measures (15.7% for immigrant parents in our data). Yet, given the sensitivity and risk, there will likely always be a relatively high level of item nonresponse. We conducted sensitivity testing to assess the effect of including a binary indicator in our models that indicated whether either parent’s status had been imputed.

Covariates

Child variables included age and gender. Other covariates included whether the household was in a metropolitan area, father’s documentation status, mother’s race/ethnicity, whether at least one parent had been in the United States for 5+ years, whether anyone in the household age 15+ spoke English well or very well, parental education and employment, and family income as a percentage of federal poverty guidelines (FPG).44 Models with our state policy indicator also included state-level covariates of the percentage of the state’s immigrant population who were noncitizens and percentage of the total state population who were undocumented immigrants.

Analysis

We provide weighted sample characteristics, with tests (χ2) for differences by mother’s documentation status (Table 1). We first ran linear probability models to estimate differences by mother’s documentation status in the probability of US-born children being uninsured. We estimated differences for children with legal permanent resident or undocumented immigrant mothers, relative to children with citizen mothers (Table 2). Second, we included an interaction in our models between mother’s documentation status and whether the child lived in a state with “nonrestrictive” prenatal coverage that had taken up the Unborn Child CHIP Option or otherwise used state funding to provide prenatal coverage regardless of documentation status (see Figure 1 for grouping of states). We report adjusted probabilities according to mother’s documentation status and state policy (Figure 2); we also conducted Wald tests to test for the overall significance of the interaction. We first tested for differences for each group compared with children with citizen mothers who lived in states with restrictive prenatal coverage, given that we would not expect the absence (or presence) of this policy to have any effect on insurance for children with citizen mothers. We also tested for differences by mother’s documentation status within states with nonrestrictive prenatal coverage and differences within each group of mother’s documentation status (eg, uninsurance for children with undocumented immigrant mothers in restrictive vs nonrestrictive states; Figure 2). Analyses accounted for the complex survey design, which includes accounting for clustering (primary sampling units) and strata, and we used Taylor series linearization for variance estimation. Analyses were conducted in Stata 15.0.25

Table 1.

Uninsurance and Characteristics of US-Born Citizen Children in Immigrant Families by Mother’s Documentation Statusa,b.

| Unweighted n | Total, N = 4080 | Mother’s Status |

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citizen, n = 2092 | Legal Permanent Resident, n = 1375 | Undocumented immigrant, n = 613 | |||

| Weighted % of total | 51.1% | 33.8% | 15.1% | ||

| Uninsured | 20.1% | 14.9% | 22.6% | 31.9% | *** |

| Child’s age (mean) | 7.5 | 8.2 | 7.1 | 6.0 | *** |

| Female | 50.1% | 48.8% | 51.1% | 52.5% | .137 |

| Household in metropolitan area | 87.2% | 88.8% | 86.0% | 84.5% | .154 |

| Father’s documentation status | |||||

| Citizen | 44.3% | 62.5% | 31.7% | 11.3% | *** |

| Legal permanent resident | 27.0% | 19.9% | 45.2% | 10.7% | |

| Undocumented immigrant | 12.6% | 4.9% | 3.8% | 58.1% | |

| No father in household | 16.1% | 12.8% | 19.3% | 20.0% | |

| Mother’s race/ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Latina white | 24.8% | 31.8% | 20.2% | 11.1% | *** |

| Latina | 49.7% | 33.5% | 59.9% | 81.3% | |

| Non-Latina black | 8.6% | 11.0% | 7.0% | 3.8% | |

| Non-Latina Asian | 14.4% | 19.6% | 11.6% | 3.4% | |

| Non-Latina other/multiple | 2.6% | 4.1% | 1.3% | 0.4% | |

| At least 1 parent in the United States for 5+ years | 90.3% | 93.1% | 89.6% | 82.9% | *** |

| At least 1 person aged 15+ years speaks English well/very well | 77.8% | 91.5% | 70.0% | 49.0% | *** |

| At least one parent with high school diploma or higher | 79.1% | 91.6% | 69.2% | 58.9% | *** |

| Parental employment | |||||

| No parent employed | 9.4% | 4.9% | 13.4% | 15.9% | *** |

| At least one parent employed, but only part-time | 15.9% | 12.6% | 17.7% | 23.0% | |

| At least one parent employed full-time | 74.7% | 82.5% | 68.9% | 61.0% | |

| Family income as % of FPG | |||||

| FPG ≤ 100% | 28.5% | 16.8% | 35.3% | 52.9% | *** |

| FPG 101% to 200% | 26.1% | 22.3% | 30.4% | 29.2% | |

| FPG 201% to 300% | 15.1% | 17.0% | 14.5% | 10.4% | |

| FPG >300% | 30.2% | 43.9% | 19.8% | 7.4% | |

Abbreviation: FPG, federal poverty guidelines.

Source: Survey of Income & Program Participation, 2008 Panel Wave 2, December 2008.

χ2 test of differences by parental documentation status, F-test for age differences: ***P < .001.

Table 2.

Probability of Being Uninsured by Mother’s Documentation Status Among US-Born Citizen Children in Immigrant Familiesa.

| Unadjusted |

Adjusted |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Probability | 95% CI | Linear Probability | 95% CI | |

| Mother’s documentation status | ||||

| Citizen | Ref | Ref | ||

| Legal permanent resident | .077*** | (0.039 to 0.115) | .031 | (−0.015 to 0.078) |

| Undocumented immigrant | .170*** | (0.104 to 0.226) | .088* | (0.004 to 0.172) |

| Child’s age (mean) | .004* | (0.001 to 0.007) | ||

| Female | −.010 | (−0.034 to 0.015) | ||

| Household in metropolitan area | .008 | (−0.068 to 0.085) | ||

| Father’s documentation status | ||||

| Citizen | Ref | |||

| Legal permanent resident | 0.024 | (−0.027 to 0.075) | ||

| Undocumented immigrant | .025 | (−0.070 to 0.123) | ||

| No father in household | −.019 | (−0.090 to 0.052) | ||

| Mother’s race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Latina white | Ref | |||

| Latina | .063* | (0.005 to 0.121) | ||

| Non-Latina black | −.003 | (−0.075 to 0.070) | ||

| Non-Latina Asian | −.028 | (−0.077 to 0.021) | ||

| Non-Latina other/multiple | −.021 | (−0.089 to 0.047) | ||

| At least 1 parent in the United States for 5+ years | −.109** | (−0.182 to −0.036) | ||

| At least 1 person aged 15+ years speaks English well/very well | .032 | (−0.027 to 0.091) | ||

| At least 1 parent with high school diploma or higher | −.016 | (−0.078 to 0.046) | ||

| Parental employment | ||||

| No parent employed | Ref | |||

| At least 1 parent employed, but only part-time | 0.068 | (−0.031 to 0.167) | ||

| At least 1 parent employed full-time | .001 | (−0.085 to 0.088) | ||

| Family income as % of FPG | ||||

| FPG ≤ 100% | Ref | |||

| FPG 101% to 200% | −.013 | (−0.081 to 0.055) | ||

| FPG 201% to 300% | −.024 | (−0.100 to 0.052) | ||

| FPG > 300% | −.095** | (−0.163 to −0.027) | ||

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; FPG, federal poverty guidelines.

Source: Survey of Income and Program Participation, 2008 Panel Wave 2, December 2008.

P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

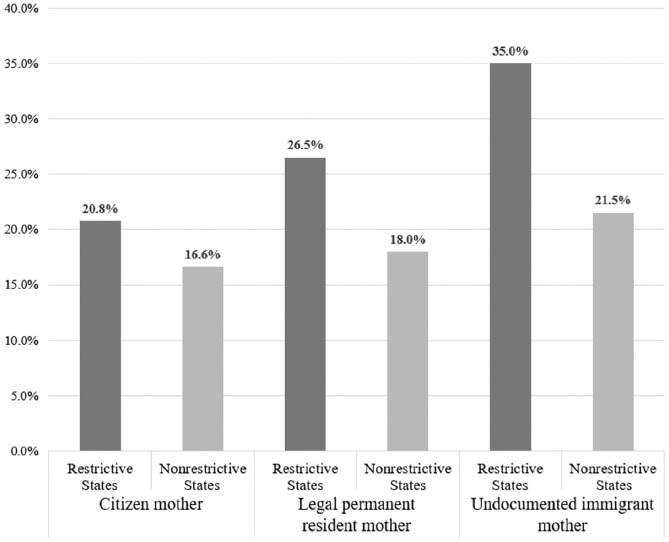

Figure 2.

Adjusted probabilities of children’s uninsurance by mother’s documentation status and state policy on prenatal coverage.

Source: Survey of Income & Program Participation, 2008 Panel Wave 2, December 2008.

Restrictive states only provide prenatal coverage to citizen and “qualified” immigrant mothers.

Nonrestrictive states provide prenatal coverage regardless of the mother’s documentation status.

Models adjust for child’s age and gender, household metropolitan area status, father’s documentation status, mother’s race/ethnicity, whether at least one parent had been in the United States for 5+ years, whether anyone in the household age 15+ spoke English well or very well, parental education and employment, family income as a percentage of FPG, the percentage of the state’s immigrant population who were noncitizens, and the percentage of the total state population made up by undocumented immigrants.

Ethical Approval and Informed Consent

This study was reviewed and approved by the university’s institutional review board. Informed consent was not required for the current analysis because public-use, deidentified secondary survey data were used.

Results

Among all US-born children in immigrant families, 51.1% had citizen mothers, 33.8% had mothers who were legal permanent residents, and the remaining 15.1% had undocumented immigrant mothers. Overall, 1 in 5 (20.1%) children in immigrant families lacked insurance and uninsurance varied significantly by parental documentation status (P < .001). Children whose mothers were undocumented immigrants had the highest rate of uninsurance (31.9%), while children whose mothers were citizens had the lowest (14.9%).

The majority of US-born children with citizen or undocumented immigrant mothers had fathers with similar immigration statuses. Mother’s race/ethnicity, whether at least one parent had lived in the United States for more than 5 years, and whether at least one person 15 years of age or older spoke English well or very well varied by maternal documentation status, as did parental education and employment and family income as a percentage of FPG.

Compared with children with citizen mothers, children whose mothers were undocumented immigrants had a 17.0 percentage point (pp) higher probability of being uninsured (P < .001), while children whose mothers were legal permanent residents had a 7.7 pp higher probability of lacking coverage (P < .001; Table 2). The gap for children with undocumented immigrant mothers remained but was attenuated in adjusted models (8.8 pp difference, P < .05), while the difference for children with legal permanent resident mothers was no longer statistically significant. Child’s age, maternal race/ethnicity, parents’ length of time in the United States, and family income were associated with uninsurance. Specifically, older children were more likely to be uninsured than younger children, children with Latina mothers were more likely to be uninsured than children with non-Latina white mothers, children with at least one parent in the United States for 5+ years were less likely to be uninsured, and children with family incomes greater than 300% FPG had a lower probability of being uninsured.

In models assessing the interaction between mother’s documentation status and state policy on prenatal coverage, the overall interaction was significant (P < .05). Significant covariates included child’s age, whether at least one parent had been in the United States for 5+ years, and family income. Mother’s race/ethnicity was not significant, in contrast to models only examining mother’s documentation status. As seen in Figure 2, children with undocumented immigrant mothers in states with restrictive prenatal coverage (eg, states that restrict prenatal coverage to income-eligible citizens or “qualified” immigrants) had the highest adjusted probability of being uninsured (35.0%). Relative to children with citizen mothers in states with restrictive prenatal coverage (20.8%), only children with undocumented immigrant mothers in restrictive states (35.0%) had a significantly higher probability of being uninsured (14.2 pp, P < .05). Neither children with legal permanent resident mothers in restrictive states (26.5%), nor any of the 3 groups of children in nonrestrictive states (16.6%, 18.0%, and 21.5%, respectively), were more likely to be uninsured than their counterparts with citizen mothers in restrictive states. However, compared with children with citizen mothers in nonrestrictive states (16.6%), both children with undocumented immigrant mothers and children with a legal permanent resident mother in states with restrictive prenatal coverage (35.0% and 26.5%, respectively) had a significantly higher probability of being uninsured (18.4 pp [P < .01] and 9.9 pp [P < .01], respectively). For children residing in states with nonrestrictive prenatal coverage, there were no significant differences in uninsurance by maternal documentation status. Finally, when examining differences by policy restrictiveness within each group of children, we found that state policy on prenatal coverage was only associated with being uninsured among children with noncitizen mothers. Children with citizen mothers in restrictive states (20.8%) were equally likely to be uninsured as those with citizen mothers in nonrestrictive states providing prenatal coverage to all immigrant mothers (16.6%). In contrast, children with undocumented immigrant mothers in restrictive states (35.0%) were significantly more likely to be uninsured than their counterparts with undocumented immigrant mothers in nonrestrictive states (21.5%; 13.5 pp difference, P < .05). The same pattern was observed for children with legal permanent resident mothers (8.5 pp difference, P < .05).

Sensitivity Analyses

Across all models, results were robust to including a binary variable indicating if children had at least one parent whose status had been imputed by SIPP.

Discussion

By examining differences in uninsurance by maternal documentation status within a nationally representative sample of US-born children in immigrant families, our study increases understanding of long-standing insurance inequities for children in mixed-status families. Extensive work has examined differences by parental citizenship status nationally10,12,13; we provide evidence of even larger disparities when considering parental documentation status. Furthermore, our study demonstrates the role of state-level implementation of federal health care policy as a potential mechanism in facilitating or impeding children’s access to insurance.

We found significant insurance gaps for US-born children with undocumented immigrant mothers, even in adjusted models. Coverage gaps for children with legal permanent resident mothers were also observed, but the demographic and socioeconomic factors included in our models—such as language, parents’ length of time in the United States, parental employment and education, and family income—appeared to explain these gaps as adjusted differences were not significant. In contrast, these factors do not appear to tell the whole story for children with undocumented immigrant mothers. This leaves unanswered questions and suggests that unmeasured mechanisms such as fear of detection or deportation may explain these differences.

Similar to previous work, we found that children with Latina mothers were more likely to be uninsured than children with non-Latina white mothers.45,46 Recent evidence demonstrates that despite large, significant gains in insurance for Latinx youth following the ACA, inequities remain, both compared with white youth and across various Latinx heritage groups.46,47 In our study, half of all US-born children in immigrant families had Latina mothers, ranging from 34% of children with citizen mothers to 81% of children with undocumented immigrant mothers. However, even when examining both maternal and paternal documentation status we find that the disparity for children with Latina mothers remained. We did not have sufficient power to model an interaction between maternal documentation status and race/ethnicity, but this finding may suggest that barriers related to documentation status manifest differently for Latina mothers than other racial/ethnic groups.48 This is especially important given the heightened racist, xenophobic rhetoric, and hostile policies toward the Latinx community.49,50

Even with gains in children’s insurance over the past decade, it is likely the disparities we observed in the current study persist. Due to increased Medicaid/CHIP eligibility, outreach/enrollment campaigns, and simplified enrollment,5,51 as well as the ACA’s “welcome mat” effect that led to gains in insurance for previously eligible but unenrolled children,32 children’s uninsurance has decreased considerably. Yet, even though the gap has lessened since 2008,1 children in immigrant families are currently still 2 times more likely to be uninsured than their counterparts.6 Whether even greater disparities according to parental documentation status remain is unknown, and the SIPP no longer includes measures of documentation status.

The exclusion of undocumented immigrants from the ACA could have actually increased disparities by parental documentation status. The movement of Medicaid enrollment into the marketplace in certain states also means information on citizenship/documentation status is now verified with the Department of Homeland Security, and even though parents’ status is not verified for children’s applications, this change could discourage some undocumented immigrant parents from enrolling children. More important, ramped-up deportation and detention under the current administration could also lead to substantial changes in coverage for US-born children in mixed-status families.39,41,42,52 Punitive immigration enforcement policies are associated with declines in seeking health care services48,53-56 and recent evidence suggests immigrant families may be dis-enrolling even their US-born children from public benefits out of fear.57 The administration’s current effort to change and expand the definition and application of public charge could also lead to substantial reductions in insurance for children with undocumented immigrant or legal permanent resident mothers.58,59

Our study provides evidence of one potential pathway for federal and state policy to mitigate inequities for children in mixed-status families. In previous qualitative work that informs the current analysis, immigrant parents and key community informants consistently reported the availability of prenatal coverage regardless of documentation status as a key factor in subsequently accessing Medicaid/CHIP for US-born children.30 Parents described access to prenatal coverage as an important buffer to any potential fear, hesitation, or confusion that undocumented immigrant parents would have felt in signing up their US-born children, since mothers learned during pregnancy about their children’s eligibility for coverage regardless of parents’ own documentation status. This helped lessen fear that enrolling in these programs would adversely affect their families. In the current analysis, racial/ethnic disparities were no longer significant in models including our state policy variable. Thus, beyond the explicit facilitation of prenatal coverage to undocumented immigrant mothers, this policy could be especially important for equalizing access for Latina mothers and, by extension, their children. In fact, previous evidence on the Unborn Child CHIP option showed increases in prenatal care for immigrant Latina mothers in states implementing this policy option compared with states that did not.60

Despite this compelling evidence, it is possible that this particular state-level policy variable is actually picking up on or serving as a proxy for other polices or structural factors within nonrestrictive versus restrictive states. Other legislation targeted at immigrant communities—such as legislation regarding local immigration enforcement, employment, and access to identification/driver’s licenses—could have a significant impact on whether or to what degree immigrant health care policy presents itself as a barrier to US-born children’s coverage. Indeed, the National Conference of State Legislatures asserted that in 2007 states were proposing and passing “an unprecedented amount” of immigrant legislation, with over 1400 total bills introduced across all states.61 Regardless of the underlying mechanism at work in the 34 restrictive states, a high percentage of US-born children with undocumented immigrant mothers were without insurance; a disparity not experienced by children in the 16 states + DC where prenatal coverage was accessible to all women regardless of documentation status as of 2008.

Although states receive a federal match (currently at 88% to 100%62) for the CHIP Unborn Child Option, since 2008 take-up has been stagnant63; only one additional state (Missouri in 201564) has expanded access to comprehensive prenatal coverage regardless of documentation status. This suggests that political factors may be preventing states from taking up a relatively inexpensive and critical initiative, which should be cause for concern among pediatricians considering the crucial role of health insurance for both maternal and children’s access to care and health.11,60,65 The fact that US-born children with undocumented immigrant mothers in several states were impeded from accessing the benefits that their counterparts in nonrestrictive states enjoy also highlights the need for federal legislation to equalize access across states. Rather than only extending coverage through this optional match, the federal government could end PRWORA restrictions entirely, if even for undocumented immigrant pregnant women. This would help more women access the comprehensive, quality prenatal care that is so crucial for maternal and child health and—as this analysis suggests—ensure that children in mixed-status families are connected to coverage. The feasibility of such a change is unclear, especially currently, but could be an important alternative. Advocates of women’s reproductive health rights have criticized the problematic nature of the motivation for and language employed in the regulation, which emphasizes care for the “unborn fetus” rather than the mother herself.66 Even while highlighting the importance of this policy for immigrant women and their families, it is critical to keep these points in mind and explore broader, permanent, women- and family-centered solutions. California has emerged as a leader in seeking solutions to extend coverage. Prior to the 2016 presidential election, the state requested a 1332 federal waiver to allow undocumented immigrants to buy insurance (at full cost) through Covered CA (the waiver was withdrawn after the election).67 Following the state’s May 2016 expansion of Medi-Cal to all children, California is now also considering expanding to all income-eligible adults regardless of status.68 While expanding to all income-eligible adults would not directly affect US-born children’s eligibility, our study suggests it may be a way to reach children in mixed-status families.

Limitations

We use the only measures of documentation status available in a nationally representative, public-use survey. No data on documentation status past 2008 are publicly available. Major policy shifts since 2008—such as those we note—could have implications for the disparities we document here and we attempt to address potential effects. Future research to explore the connections between maternal and children’s coverage among mixed-status families could draw on confidential data files from the California Health Interview Survey—the only representative health survey that currently inquires about documentation status. Second, the sensitivity of the documentation status measure presents limitations. Item nonresponse is relatively high, but the Census Bureau takes steps to correct it and our findings were robust to sensitivity analyses. Coverage and nonresponse error may contribute to underestimation of the total population of undocumented immigrants.43 However, a recent assessment of the SIPP’s measures shows that estimates of the number and characteristics of undocumented immigrants align with other widely used models.69 Any bias from an undercount would underestimate insurance disparities among children with undocumented immigrant parents. Parents who are not included in the sample frame or do not respond are less likely to interact with institutions that may increase risk of status disclosure, such as institutions through which families enroll in insurance. Third, we only examined access to prenatal coverage on a macro-, state-level with cross-sectional data. We were not able to estimate whether having Medicaid/CHIP during pregnancy led to increased probability of the child gaining insurance. We were not able to observe mothers’ insurance during pregnancy, whether these policies were in effect at the time of pregnancy, and state of residence during pregnancy. We only observed the current state of residence. In addition, general differences in health care and Medicaid policy—which can affect children’s enrollment—exist across states. We would not expect the impact of general policy differences to vary by parents’ documentation status. Our examination of uninsurance among children with citizen mothers serves as a form of control for testing for differences between restrictive and nonrestrictive states.

Conclusion

We provide evidence of a clear gradient of access to coverage for US-born children in immigrant families. Mixed-status families face numerous structural barriers that prevent children from accessing the health insurance crucial for their well-being.11,65 The Unborn Child CHIP Option has the potential to reduce inequities for mothers and children, but has been significantly under-implemented despite steady federal funding. While more work is needed to further probe this policy’s impacts, our findings demonstrate that access to insurance for mixed-status families differs substantially based on the state they call home. Through the crafting and maintenance of initiatives that provide access in the face of federal restrictions, states can and do play an important role in mitigating barriers to accessing coverage among mixed-status families.

Acknowledgments

We extend our profound gratitude to the immigrant parents who so graciously shared their experiences within the other components of the dissertation. Your narratives brought deep meaning to the work, which without your participation would not have been possible.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: JKP: Contributed to conception and design; contributed to acquisition, analysis, and interpretation; drafted the manuscript; critically revised the manuscript; gave final approval; agrees to be accountable for all aspects of work ensuring integrity and accuracy.

KTC: Contributed to conception and design; contributed to interpretation; critically revised the manuscript; gave final approval; agrees to be accountable for all aspects of work ensuring integrity and accuracy.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This project was supported by R36 Dissertation Grant Number R36HS021973 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The agency had no involvement in the study design, analysis and interpretation of data, or writing and submission of this manuscript. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

ORCID iD: Jessie Kemmick Pintor  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3860-4857

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3860-4857

References

- 1. Jarlenski M, Baller J, Borrero S, Bennett WL. Trends in disparities in low-income children’s health insurance coverage and access to care by family immigration status. Acad Pediatr. 2016;16:208-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Seiber EE. Which states enroll their Medicaid-eligible, citizen children with immigrant parents? Health Serv Res. 2013;48(2 pt 1):519-538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mendoza FS. Health disparities and children in immigrant families: a research agenda. Pediatrics. 2009;124(suppl 3):S187-S195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Acevedo-Garcia D, Stone LC. State variation in health insurance coverage for US citizen children of immigrants. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27:434-446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Howell EM, Kenney GM. The impact of the Medicaid/CHIP expansions on children: a synthesis of the evidence. Med Care Res Rev. 2012;69:372-396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Health coverage of immigrants. https://www.kff.org/disparities-policy/fact-sheet/health-coverage-of-immigrants/. Published February 15, 2019. Accessed March 15, 2019.

- 7. Migration Policy Institute. Children in US immigrant families (by age group and state, 1990 versus 2017). https://www.migrationpolicy.org/programs/data-hub/charts/children-immigrant-families. Accessed March 15, 2019.

- 8. Seiber EE. Covering the remaining uninsured children—almost half of uninsured children live in immigrant families. Med Care. 2014;52:202-207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fix M, Zimmermann W. All under one roof: mixed-status families in an era of reform. Int Migr Rev. 2001;35:397-419. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ku L, Matani S. Left out: immigrants’ access to health care and insurance. Health Aff (Millwood). 2001;20:247-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ku L. Improving health insurance and access to care for children in immigrant families. Ambul Pediatr. 2007;7:412-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Huang ZJ, Yu SM, Ledsky R. Health status and health service access and use among children in US immigrant families. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:634-640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ojeda VD, Brown ER. Mind the gap: parents’ citizenship as predictor of Latino children’s health insurance. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2005;16:555-575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Derose KP, Escarce JJ, Lurie N. Immigrants and health care: sources of vulnerability. Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26:1258-1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Passel JS. Demography of immigrant youth: past, present, and future. Future Child. 2011;21:19-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Passel JS, Cohn D. Children of unauthorized immigrants represent rising share of K-12 students. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/11/17/children-of-unauthorized-immigrants-represent-rising-share-of-k-12-students/. Published November 17, 2016. Accessed March 15, 2019.

- 17. Salami A. Immigrant eligibility for health care programs in the United States. http://www.ncsl.org/research/immigration/immigrant-eligibility-for-health-care-programs-in-the-united-states.aspx/. Published September 19, 2017. Accessed March 15, 2019.

- 18. Fortuny K, Chaudry A. Overview of immigrants eligibility for SNAP, TANF, Medicaid, and CHIP. https://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/overview-immigrants-eligibility-snap-tanf-medicaid-and-chip. Published March 27, 2012. Accessed March 15, 2019.

- 19. Varsanyi M, Lewis P, Provine D, Decker S. Immigration Federalism: Which Policy Prevails? Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fix M, Tumlin K. Welfare Reform and the Devolution of Immigrant Policy. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 21. US Department of Health and Human Services. State Children’s Health Insurance Program. Eligibility for prenatal care and other health services for unborn children; Final Rule 42 CFR 457. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2002/10/02/02-24856/state-childrens-health-insurance-program-eligibility-for-prenatal-care-and-other-health-services-for. Accessed August 17, 2019.

- 22. Jarlenski MP, Bennett WL, Barry CL, Bleich SN. Insurance coverage and prenatal care among low-income pregnant women: an assessment of states’ adoption of the “unborn child” option in Medicaid and CHIP. Med Care. 2014;52:10-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. New option for states to provide federally funded Medicaid and CHIP coverage to additional immigrant children and pregnant women. https://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/7933.pdf. Published July 10, 2019. Accessed August 17, 2019.

- 24. Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. Challenges of Providing Health Coverage for Children and Parents in a Recession: A 50 State Update on Eligibility Rules, Enrollment and Renewal Procedures, and Cost-Sharing Practices in Medicaid and SCHIP in 2009. Washington, DC: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Reichman NE, Corman H, Noonan K, Schwartz-Soicher O. Effects of prenatal care on maternal postpartum behaviors. Rev Econ Househ. 2010;8:171-197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. McCormick MC, Siegel JE. Recent evidence on the effectiveness of prenatal care. Ambul Pediatr. 2001;1:321-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Noonan K, Corman H, Schwartz-Soicher O, Reichman NE. Effects of prenatal care on child health at age 5. Matern Child Health J. 2013;17:189-199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kozhimannil KB, Hardeman RR, Henning-Smith C. Maternity care access, quality, and outcomes: a systems-level perspective on research, clinical, and policy needs. Semin Perinatol. 2017;41:367-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bryant AS, Worjoloh A, Caughey AB, Washington AE. Racial/ethnic disparities in obstetric outcomes and care: prevalence and determinants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202:335-343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kemmick Pintor J. Latino Children at the Intersection of Immigration & Health Care Policy: A Mixed-Methods Study of Parental Documentation Status, State-level Policy, and Access to Coverage and Care [dissertation]. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 31. DeVoe JE, Marino M, Angier Het al. Effect of expanding Medicaid for parents on children’s health insurance coverage: lessons from the Oregon Experiment. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:e143145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hudson JL, Moriya AS. Medicaid expansion for adults had measurable “welcome mat” effects on their children. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36:1643-1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Stevens GD, West-Wright CN, Tsai KY. Health insurance and access to care for families with young children in California, 2001-2005: differences by immigration status. J Immigr Minor Health. 2010;12:273-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Weathers AC, Minkovitz CS, Diener-West M, O’Campo P. The effect of parental immigration authorization on health insurance coverage for migrant Latino children. J Immigr Minor Health. 2008;10:247-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Oropesa R, Landale NS, Hillemeier MM. Legal status and health care: Mexican-origin children in California, 2001-2014. Popul Res Policy Rev. 2016;35:651-684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Flores G, Abreu M, Tomany-Korman SC. Why are Latinos the most uninsured racial/ethnic group of US children? A community-based study of risk factors for and consequences of being an uninsured Latino child. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e730-e740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ziol-Guest KM, Kalil A. Health and medical care among the children of immigrants. Child Dev. 2012;83:1494-1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lurie IZ. Welfare reform and the decline in the health-insurance coverage of children of non-permanent residents. J Health Econ. 2008;27:786-793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Trisi D, Herrera G. Administration Actions Against Immigrant Families Harming Children Through Increased Fear, Loss of Needed Assistance. Washington, DC: Center for Budget and Policy Priorities; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pierce S, Selee A. Immigration Under Trump: A Review of Policy Shifts in the Year Since the Election. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Artiga S, Ubri P. Living in an Immigrant Family in America: How Fear and Toxic Stress are Affecting Daily Life, Well-Being, & Health. Washington, DC: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cervantes W, Ullrich R, Matthews H. Our Children’s Fear: Immigration Policy’s Effects on Young Children. Washington, DC: Center for Law and Social Policy; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Judson DH, Swanson DA. Estimating characteristics of the foreign born by legal status: an evaluation of data and methods. In: Estimating Characteristics of the Foreign-Born by Legal Status. Heidelberg, Netherlands: Springer; 2011:1-50. [Google Scholar]

- 44. US Department of Health and Human Services. The 2008 HHS poverty guidelines. http://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty/08poverty.shtml. Accessed March 15, 2019.

- 45. Langellier BA, Chen J, Vargas-Bustamante A, Inkelas M, Ortega AN. Understanding health-care access and utilization disparities among Latino children in the United States. J Child Health Care. 2016;20:133-144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ortega AN, McKenna RM, Chen J, Alcalá HE, Langellier BA, Roby DH. Insurance coverage and well-child visits improved for youth under the Affordable Care Act, but Latino youth still lag behind. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18:35-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pintor JK, Chen J, Alcalá HEet al. Insurance coverage and utilization improve for Latino youth but disparities by heritage group persist following the ACA. Med Care. 2018;56:927-933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Beniflah JD, Little WK, Simon HK, Sturm J. Effects of immigration enforcement legislation on Hispanic pediatric patient visits to the pediatric emergency department. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2013;52:1122-1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Newman BJ, Shah S, Collingwood L. Race, place, and building a base: Latino population growth and the nascent Trump campaign for president. Public Opin Q. 2018;82:122-134. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Cisneros JD. Racial presidentialities: narratives of Latinxs in the 2016 campaign. Rhetoric Public Aff. 2017;20:511-524. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Goldstein IM, Kostova D, Foltz JL, Kenney GM. The impact of recent CHIP eligibility expansions on children’s insurance coverage, 2008-12. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33:1861-1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Baker SM, Li LZ, Steele RW. Detainment of immigrant children. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2019;58:266-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Toomey RB, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Williams DR, Harvey-Mendoza E, Jahromi LB, Updegraff KA. Impact of Arizona’s SB 1070 immigration law on utilization of health care and public assistance among Mexican-origin adolescent mothers and their mother figures. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(suppl 1):S28-S34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hacker K, Chu J, Arsenault L, Marlin RP. Provider’s perspectives on the impact of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) activity on immigrant health. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012;23:651-665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Rhodes SD, Mann L, Simán FMet al. The impact of local immigration enforcement policies on the health of immigrant Hispanics/Latinos in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:329-337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Pedraza FI, Nichols VC, LeBrón AMW. Cautious citizenship: the deterring effect of immigration issue salience on health care use and bureaucratic interactions among Latino US citizens. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2017;42:925-960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bazar E. Some immigrants, fearful of political climate, shy away from Medi-Cal. https://californiahealthline.org/news/some-immigrants-fearful-of-political-climate-shy-away-from-medi-cal/. Published February 16, 2017. Accessed August 17, 2019.

- 58. Batalova J, Fix M, Greenberg M. Chilling Effects: The Expected Public Charge Rule and Its Impact on Legal Immigrant Families’ Public Benefits Use. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Artiga S, Garfield R, Damico A. Estimated Impacts of the Proposed Public Charge Rule on Immigrants and Medicaid. Washington, DC: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Drewry J, Sen B, Wingate M, Bronstein J, Foster EM, Kotelchuck M. The impact of the State Children’s Health Insurance Program’s unborn child ruling expansions on foreign-born Latina prenatal care and birth outcomes, 2000-2007. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19:1464-1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. National Conference of State Legislatures. 2007. Enacted State Legislation related to immigrants and immigration. http://www.ncsl.org/research/immigration/2007-enacted-state-legislation-related-to-immigran.aspx. Published January 31, 2008. Accessed March 15, 2019.

- 62. Brooks T. CHIP funding has been extended, what’s next for children’s health coverage? https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20180130.116879/full/. Published January 30, 2018. Accessed August 17, 2019.

- 63. Green T, Hochhalter S, Dereszowka K, Sabik L. Changes in public prenatal care coverage options for noncitizens since welfare reform: Wide state variation remains. Med Care Res Rev. 2016;73:624-639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CHIP State Plan Amendments: MO-15-0009: The State Is Adding Coverage of Pregnant Women and Unborn Children From Conception to Birth to the State’s Separate CHIP. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Halfon N, DuPlessis H, Inkelas M. Transforming the US child health system. Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26:315-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Kaiser Health News. Bush administration to propose extending CHIP coverage to “Unborn” children. https://khn.org/morning-breakout/dr00005643/. Published June 11, 2009. Accessed August 17, 2019.

- 67. SB-10 Health care coverage: immigration status. California Legislature; 2015-2016. https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=201520160SB10. Accessed August 17, 2019.

- 68. AB-2965 Medi-Cal: immigration status. https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billTextClient.xhtml?bill_id=201720180AB2965. Published May 26, 2018. Accessed August 17, 2019.

- 69. Bachmeier JD, Van Hook J, Bean FD. Can we measure immigrants’ legal status? Lessons from two US surveys. Int Migr Rev. 2014;48:538-566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]