Abstract

This study examined the relationship of achievable mean dose and percent volumetric overlap of salivary gland with the planning target volume (PTV) in volumetric-modulated arc therapy (VMAT) plan in radiotherapy for a patient with head-and-neck cancer. The aim was to develop a model to predict the viability of planning objectives for both PTV coverage and organs-at-risk (OAR) sparing based on overlap volumes between PTVs and OARs, before the planning process. Forty patients with head-and-neck cancer were selected for this retrospective plan analysis. The patients were treated using 6 MV photons with 2-arc VMAT plan in prescriptions with simultaneous integrated boost in dose of 70 Gy, 63 Gy, and 58.1 Gy to primary tumor sites, high-risk nodal regions, and low-risk nodal regions, respectively, over 35 fractions. A VMAT plan was generated using Varian Eclipse (V13.6), in optimization with biological-based generalized equivalent uniform dose (gEUD) objective for OARs and targets. Target dose coverage (D95, Dmax, conformity index) and salivary gland dose (Dmean and Dmax) were evaluated in those plans. With a range of volume overlaps between salivary glands and PTVs and dose constraints applied, results showed that dose D95 for each PTV was adequate to satisfy D95 >95% of the prescription. Mean dose to parotid <26 Gy could be achieved with <20% volumetric overlap with PTV58 (parotid-PTV58). On an average, the Dmean was seen at 15.6 Gy, 21.1 Gy, and 24.2 Gy for the parotid-PTV58 volume at <5%, <10%, and <20%, respectively. For submandibular glands (SMGs), an average Dmean of 27.6 Gy was achieved in patients having <10% overlap with PTV58, and 36.1 Gy when <20% overlap. Mean doses on parotid and SMG were linearly correlated with overlap volume (regression R2 = 0.95 and 0.98, respectively), which were statistically significant (P < 0.0001). This linear relationship suggests that the assessment of the structural overlap might provide prospective for achievable planning objectives in the head-and-neck plan.

Keywords: Generalized equivalent uniform dose optimization, head-and-neck cancer, radiotherapy, salivary gland sparing, volumetric-modulated arc therapy plan

INTRODUCTION

Radiotherapy is the main nonsurgical treatment for those patients with head-and-neck cancer. To minimize potential adverse effects, like xerostomia during and after treatment, dosimetric sparing on salivary glands becomes essential. When considering oral salivary output, parotids are thought to be one of the most important organs at risks (OARs) for dose sparing. Salivary flow from the parotid is affected by the radiation dose received and the volume of gland irradiated.[1,2] The metric correlates best with long-term saliva production is the mean dose to the parotid. Up to 26 Gy for parotid mean dose is commonly acceptable.[3,4] Dose sparing of bilateral superficial lobes of parotids reduces the risk of developing high-grade subjective xerostomia.[5,6] Dose sparing on submandibular glands (SMGs) is also applied for reducing risk of xerostomia. The SMG salivary flow rates depend on mean dose with recovery over time with a threshold of 39 Gy.[7] Substantial SMG dose reduction to below this threshold without compromising planning target volume (PTV) dose coverage is feasible in some patients, at the expense of modestly higher doses to other organs.[8]

Parotid dose sparing has been previously studied in comparison of different planning techniques, including three-dimensional, static-intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT), volumetric-modulated arc therapy (VMAT), and tomo-helical IMRT.[9,10,11,12,13,14,15] Analysis of parotid volume irradiated and mean dose achieved has been reported in head-and-neck cancer patients treated using static-IMRT plan[16] and Tomo-helical plan.[17] A recent study concludes that >30% parotid volume overlapped with PTV is a predictor of poor parotid dose sparing by static-IMRT.[18] For the VMAT plan, there are limited data in the literature looking at the evaluation of salivary gland mean dose achieved and its volume overlapped with PTV. VMAT has become standard practice in the treatment of head-and-neck cancer patients with different dose prescriptions (so-called simultaneous integrated boost) and numerous OARs with different dose constraints. However, VMAT planning could be complicated and time-consuming because of the multiple target prescription aims and surrounding OAR dose constraints. Without clear evidence-based objectives, it can be difficult for the planner to determine when greater dose sparing of OARs, such as parotid and SMG, can be achieved without compromising target coverage. We examined 40 VMAT plans conducted using Eclipse with generalized equivalent uniform dose (gEUD) optimization that has been recently induced in planning.[19,20,21] Our results demonstrated a linear relationship between achievable mean dose and percent volumetric overlap of the parotid and SMG with the PTV, which could be useful for predicting what is possible for a particular patient in VMAT planning. Furthermore, the results could be applied in the development of a model used for automated planning.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient selection

In this retrospective study, 40 head-and-neck cancer patients treated at our institute during year 2014–2017 were selected following the criteria: (1) Treatment sites included primary cancer in nasopharynx, oropharynx, hypopharynx, larynx, base of tongue, superior glottis or oral cavity [Table 1], plus the lymph node regions in bilateral areas of the neck where the doses were examined on both sides of salivary glands; (2) Patients were prescribed with simultaneous integrated boost over 35 fractions, in dose of 70 Gy on primary cancer sites, 63 Gy on high-risk nodal regions and 58.1 Gy on low-risk nodal regions; (3) Patient's treatment was completed using 6 MV photon by 2-arc VMAT plan.

Table 1.

Disease site for treatment

| Primary site | TNM staging | Number of cases per site |

|---|---|---|

| Oropharynx | T2N2aM0 - T4bN2cM0 | 13 |

| Base of tongue | T1N2bM0 - T3N2bM0 | 8 |

| Nasopharynx | T2N1M0 - T4N2M1 | 7 |

| Larynx | T1aN0M0 - T4bN2aM0 | 6 |

| Hypopharynx | T2N2bM0 - T4aN0M0 | 3 |

| Superior glottis | T3N2bM0 - T4aN2cM0 | 2 |

| Oral cavity | T3N2cM0 | 1 |

Simulation and planning

The patient was immobilized using thermoplastic masks and scanned (Siemens Somatom CT-Scanner) at 3-mm interval as a part of the standard operating procedure in our institute. No contrast was applied in the process of computed tomography (CT) scanning. The PTV and OAR were contoured using Velocity (Version 3.1, Varian Medical System Inc., Atlanta, GA, USA). A co-registration of the CT images and diagnostic positron emission tomography or magnetic resonance was performed using the Velocity for the delineation of the target volumes if requested. Primary cancer sites, high-risk nodal regions, and low-risk nodal regions were contoured as PTV70, PTV63, and PTV58, respectively, according to the prescriptions. The contours of each plan underwent departmental peer review before planning.

A VMAT plan was generated using Eclipse (Version 13.6, Varian Medical System Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA) for each patient. The dose calculation model was with the Anisotropic Analytical Algorithm using a grid size of 0.25 cm × 0.25 cm × 0.25 cm and heterogeneity correction applied. Two arcs for each plan were designed with 10–30° of collimation to assist in modulation and to minimize radiation-leakage effects. The PTV70 was the principal target for plan optimization. Due to some overlaps among PTV70, PTV63 and PTV58, PTV63opt was created by subtracting PTV70 from PTV63, and PTV58opt was created by subtracting PTV63 from PTV58, both of which were used for plan optimization and data analysis. Biological optimization objective, i.e., gEUD, was applied for OARs and the target PTVs during each planning. Several studies have reported analyses of the performances and efficacy of the biologically based gEUD objectives implemented in Varian Eclipse treatment planning system.[18,19,20] Briefly, optimization with gEUD requires only a limited number of parameters, including tissue-specific parameter (α), the fractional organ volume (Vi), and receiving dose (Di). α value is suggested in AAPM TG-166 report.[22] In our optimization, OAR dose was minimized with the upper gEUD objective with α parameter varied from 1 to 40, typically 1 for minimizing mean dose and 10 for reducing the higher dose. To achieve dose distribution on PTVs, the lower gEUD objective was applied with α value from -1 to -40, typically -15. Based on our clinical experience, planners markedly benefited from optimization with gEUD in both OAR sparing and PTV coverage in VMAT plan. Dose constraints were determined by our institute's treatment directives, which follow RTOG0225 guidelines.[23]

Plan evaluation

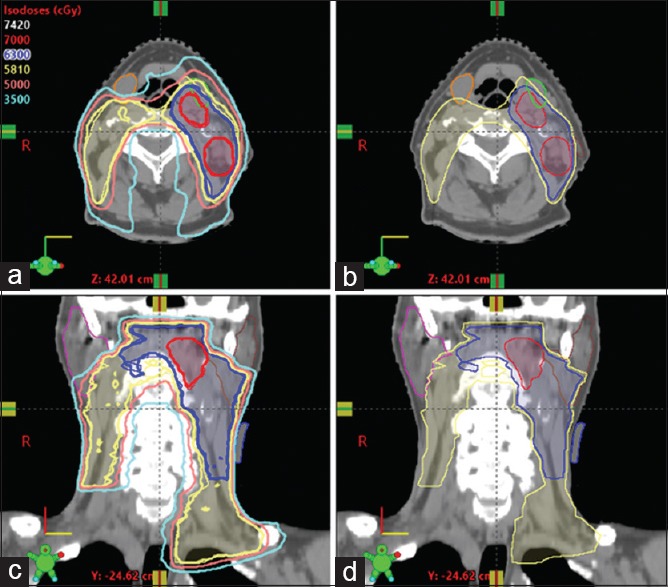

The plans selected in this study had normalization at 100% to the prescription in the evaluation of PTV coverage and OAR sparing. Following the prescriptive planning directives, cumulative dose-volume histograms were reviewed to ensure adequate PTV coverage. Visual inspection of the 95% isodose line in the axial, sagittal, and coronal planes was also conducted [Figure 1]. PTV coverage was accepted at D95 > 95% of the prescription dose, which was based on the criteria that 95% of PTV volume was covered by > 95% of the prescribed dose. Maximum pixel dose (Dmax) was not allowed to exceed 110% of the prescription and also limited within PTV70. Doses to PTV63opt and PTV58opt were evaluated in consideration of the dose coverage on PTV63 and PTV58. In addition, a conformity index (CI) was used to evaluate the homogeneity of dose distribution. The CI = VRI/VT, defined as the ratio between the volume VRI enclosed by the reference isodose and total volume VT. A CI of 100% represents the highest degree of conformity and 70% is considered acceptable.[24]

Figure 1.

An example of head-and-neck plan showing radiation dose distribution. (a and c) isodose lines are showed in lines of 70 Gy (red), 63 Gy (blue) and 58.1 Gy (yellow). (b and d) Targets were contoured in PTV70 (red), PTV63 (blue) and PTV58 (yellow). Parotids (brown, pink) and submandibular glands (green, orange) were outlined

Doses to the parotids and SMGs were reviewed for each plan and constrained under our planning directives. Volumetric information of each gland was measured in total volume and overlap with PTV58 in absolute value, i.e., cm3, using Eclipse. Correlation of percent overlapping of each gland and its mean dose was established, and linear regression was statistically examined using F-test (Excel, Microsoft Office 365). The goal of our planning was to achieve the mean doses to be <26 Gy and <35 Gy for parotids and SMGs, respectively, while PTV was maintained in dose coverage as mentioned above.

RESULTS

Evaluation of planning target volume coverage

In evaluating each plan [Table 2], PTV dose coverage was shown in relative dose (D95) and maximum pixel doses (Dmax). Dose D95 on each PTV was adequate to satisfy D95 > 95% of the prescription, as required. For all plans, dose D95 for PTV70 ranged from 69 Gy to 70.1 Gy that was 98.5%–100.1% of the prescribed 70 Gy, on an average of 69.7 Gy. CI for PTV70 ranged from 81% to 96.6%, on average of 91.2%. Maximum pixel dose for each plan was reviewed, showing on an average Dmax= 74.8 Gy ± 0.5 Gy, which was <110% of the prescription dose (70 Gy) as requested and also limited in distribution within the PTV70. For PTV63opt, dose D95 ranged from 60.7 Gy to 62.7 Gy, with an average of 62.1 Gy. An average Dmax was 72.3 Gy as its interfaced PTV70. CI varied from 79% to 94.4%, on average of 89.4%. Meanwhile, dose D95 was observed from 56.4 Gy to 58.2 Gy for PTV58opt, on average of 56.9 Gy, and CI was from 76.5% to 95%, 87.7% on average. An average Dmax67.4 Gy was seen on PTV58opt because of its interfaced area with PTV63 and/or closeness to PTV70. Conformity index at above 70% was acceptable and consistent with other report.[24] In addition, each PTV volume, i.e., cm3, was measured using Eclipse and indicated in variable sizes among those patients [Table 2]. Delivered monitor unit (MU) in those VMAT plans ranged from 462 MU to 813 MU, 660 MU on average, implying that plan was accomplished by minimizing over-optimization during the processes.

Table 2.

Planning target volume dose coverage

| PTV70 | PTV63opt | PTV58opt | |

|---|---|---|---|

| D95±SD, Gy | 69.7±0.3 | 62.1±0.5 | 56.9±0.5 |

| Dmax±SD, Gy | 74.8±0.5 | 72.3±0.7 | 67.4±1.8 |

| Conformity (CI) (%) | 91.2±3.1 | 89.4±3.6 | 87.7±3.1 |

| Volume, cm3 | 14-250 | 37-610 | 105-727 |

PTV: Planning target volume, SD: Standard deviation, CI: Conformity index, Dmax: Maximum pixel dose

Dosimetric sparing of parotids and submandibular glands

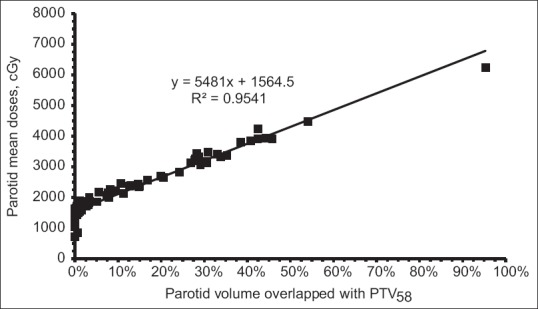

Parotid sparing stratified by overlap with PTV58 is shown in Table 3. In our analysis, we showed that mean doses (Dmean) could be <26 Gy for parotid with <20% volumetric overlap with PTV58(parotid-PTV58). Average mean doses of 15.6 Gy in the range of 7.1 Gy–20.0 Gy and 21.1 Gy in the range of 18.6 Gy–22.6 Gy were observed for those parotids having <5% and <10% parotid-PTV58 volumes, respectively. When the parotid-PTV58 volume reached to 20%, parotid Dmean increased to 24.2 Gy on average, in the range from 21.2 Gy to 26.9 Gy. Although Dmean<26 Gy might not be seen in those glands with an overlap from 20% to 40%, we showed an average mean dose 32.1 Gy in the range from 26.6 Gy to 38.5 Gy. Once >40% volume of parotid-PTV58 appeared, the idea was basically to limit the distribution of 30 Gy isodose line within the un-overlapped area of the parotid. The relationship between percent overlap and the parotid mean dose is shown in Figure 2.

Table 3.

Parotid mean dose versus percent overlap (parotid-PTV58)

| Parotid-PTV58 (%) | # gland | Dmean±SD, Gy | Dmax±SD, Gy |

|---|---|---|---|

| <5 | 38 | 15.6±2.8 | 60.8±4.5 |

| 5-10 | 9 | 21.1±1.3 | 67.7±3.6 |

| 10-20 | 9 | 24.2±1.6 | 70.2±2.9 |

| 20-40 | 17 | 32.1±2.9 | 72.3±1.7 |

| >40 | 7 | 43.7±8.6 | 72.7±1.7 |

PTV: Planning target volume, SD: Standard deviation, Dmax: Maximum pixel dose, Dmean: Mean dose

Figure 2.

Linear relationship of parotid mean dose and percent volume overlapped with PTV58. Increase of parotid mean dose was correlated with the percent overlap volume increased. Less than 26 Gy mean dose could be achieved in parotid with <20% overlapping volume. This linear relationship was statistically significant (P < 0.0001) and could be useful in a model development in knowledge-based planning in head-and-neck cancer

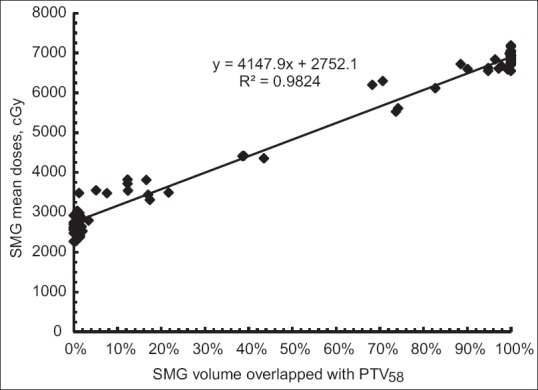

Besides dose sparing of parotids, we also strived to minimize dose to the SMG in each head-and-neck plan [Figure 3 and Table 4]. An average Dmean was 27.6 Gy in range from 22.7 Gy to 35.5 Gy in those SMGs with <10% volume overlapped with PTV58(SMG-PTV58). As volume of SMG-PTV58 increased to 20%, an average Dmean36.1 Gy was found in range from 35.4 Gy to 38.1 Gy. For SMGs with 20%–45% SMG-PTV58, an average Dmean was 41.7 Gy, ranged from 34.9 Gy to 44.1 Gy. In those plans having a higher percentage of overlapping, SMG sparing became unachievable.

Figure 3.

Relationship of mean doses of the submandibular glands and percent volume overlapped with PTV58. Less than 36 Gy mean doses were seen in those glands having <20% overlap. This linear relationship was statistically significant (P < 0.0001), suggesting that the assessment of structural overlap may provide prospective for achievable planning objectives in SMG in head-and-neck plan

Table 4.

Submandibular gland mean dose versus percent overlap (SMG-PTV58)

| SMG-PTV58 (%) | # gland | Dmean±SD, Gy | Dmax±SD, Gy |

|---|---|---|---|

| <10 | 29 | 27.6±3.3 | 60.7±4.0 |

| 10-20 | 6 | 36.1±2.1 | 68.1±2.3 |

| 20-45 | 4 | 41.7±4.5 | 70.3±1.7 |

| >45 | 41 | 67.3±3.5 | 72.9±1.5 |

SMG: Submandibular gland, PTV: Planning target volume, SD: Standard deviation, Dmax: Maximum pixel dose, Dmean: Mean dose

As the main focus of this study, we examined a relationship between salivary gland Dmean and its volumetric overlap with PTV58. Taking all data together, we found that the relationship could be described using a linear regression formula: Dmean = A × Voverlap + B (cGy), where Voverlap was the percentage volume overlapped with PTV58; A and B were regression constants. For parotids, the constant A in above equation was 5481 and B was 1564 with regression R2 = 0.95 [Figure 2]. For SMGs, the constant A and B was 4147 and 2752, respectively, with regression R2 = 0.98 [Figure 3]. This linear regression was statistically significant for parotid (P < 0.0001) and SMG (P < 0.0001). Using this linear model, estimation of mean dose on parotid and SMG became possible before planning. Mean dose < 26 Gy on parotid and <36 Gy on SMG should be feasibly achieved in the gland having 20% or less volume overlapped with PTV58. This model suggests that assessment of the structural overlap provides prospective for achievable planning objectives in the head-and-neck plan.

DISCUSSION

To minimize potential adverse effects, like xerostomia during and after treatment for head-and-neck cancer patient, dose sparing on both parotid and SMG becomes essential. The volumetric overlap is considered as a key factor primarily affecting gland mean dose. It has been proposed to use geometric factors such as parotid size and proximity to the target for dose estimation.[16,17] Previous studies demonstrate that parotid mean dose 26 Gy could be obtained at <20% overlapping in head-and-neck cancer patients treated using static-IMRT plan[16] and Tomo-helical plan.[17] More than 30% overlap occurred in parotid indicates a possibly poor sparing in the static-IMRT plan.[18] For the VMAT plan, however, the literature lacks data assessing achievable mean dose in both parotid and SMG and correlating with its volume overlapped with PTV. There are studies showing that a lower parotid mean dose could be accomplished by using static-IMRT rather than VMAT.[25,26] We asked whether parotid mean dose 26 Gy could be achieved at <20% overlapping in VMAT head-and-neck plan. Our results indicated that an acceptable mean dose of 26 Gy could be feasibly achieved in parotids with <20% volume of parotid-PTV58. Although 26 Gy mean doses might not be seen in parotids with increasing overlap up to 40%, we showed an average Dmean32.1 Gy in those parotids. Dose sparing of SMG, meanwhile, was also evaluated in this study, indicating mean dose 30 Gy or less (an average Dmean= 27.6 Gy) occurred in <10% volume of SMG-PTV58. An average Dmean was 36.1 Gy in SMGs with up to 20% overlap. When >20% overlapping existed, in these circumstances, although we strived to spare SMG, maintaining PTV dose coverage was prioritized because gross disease (PTV70) was near or overlapped with the SMGs. In addition, as depicted in [Figure 1] for the targets and OARs outlined at our institute, we understood that some overlap could exist between parotid or SMG and PTV63. As PTV63 is always located within the PTV58, therefore, the volume overlapped with PTV58 would be considered as primary causes in affecting the mean dose.

We demonstrated a linear relationship between mean dose achieved and salivary gland's volume overlapped with PTV58. The results of the current work could potentially be applied toward automated planning. Knowledge-based planning is an emerging field in radiation therapy. To apply machine learning techniques, the creation of automated planning model becomes essential.[27,28] The plan outcome is dependent on applied database quality, in which overlap volume histogram is considered as a critical factor.[29,30] To induce automated planning at our institute, we realize that data in this linear relationship could be useful and more data are required in the development of an accuracy model. We will continuously focus on study on quality and consistency of VMAT head-and-neck plan for automated planning.

CONCLUSION

In this retrospective analysis of 40 VMAT plans for head-and-neck cancer patients accomplished at our institute, we demonstrated a linear relationship between achievable mean dose and percent volumetric overlap of salivary gland with the PTV58. In VMAT plan using gEUD optimization, mean dose <26 Gy for parotid and <36 Gy for SMG could be obtained as long as the gland had <20% overlap volume with PTV58. This study suggests that the assessment of structural overlap may provide prospective for achievable planning objectives in head-and-neck plan.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cooper JS, Fu K, Marks J, Silverman S. Late effects of radiation therapy in the head and neck region. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;31:1141–64. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(94)00421-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones RE, Takeuchi T, Eisbruch A, D'Hondt E, Hazuka M, Ship JA, et al. Ipsilateral parotid sparing study in head and neck cancer patients who receive radiation therapy: Results after 1 year. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1996;81:642–8. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(96)80068-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuten A, Ben-Aryeh H, Berdicevsky I, Ore L, Szargel R, Gutman D, et al. Oral side effects of head and neck irradiation: Correlation between clinical manifestations and laboratory data. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1986;12:401–5. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(86)90358-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Makkonen TA, Tenovuo J, Vilja P, Heimdahl A. Changes in the protein composition of whole saliva during radiotherapy in patients with oral or pharyngeal cancer. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1986;62:270–5. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(86)90007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miah AB, Schick U, Bhide SA, Guerrero-Urbano MT, Clark CH, Bidmead AM, et al. A phase II trial of induction chemotherapy and chemo-IMRT for head and neck squamous cell cancers at risk of bilateral nodal spread: The application of a bilateral superficial lobe parotid-sparing IMRT technique and treatment outcomes. Br J Cancer. 2015;112:32–8. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miah AB, Gulliford SL, Morden J, Newbold KL, Bhide SA, Zaidi SH, et al. Recovery of salivary function: Contralateral parotid-sparing intensity-modulated radiotherapy versus bilateral superficial lobe parotid-sparing intensity-modulated radiotherapy. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2016;28:e69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2016.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee TF, Liou MH, Ting HM, Chang L, Lee HY, Wan Leung S, et al. Patient- and therapy-related factors associated with the incidence of xerostomia in nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients receiving parotid-sparing helical tomotherapy. Sci Rep. 2015;5:13165. doi: 10.1038/srep13165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murdoch-Kinch CA, Kim HM, Vineberg KA, Ship JA, Eisbruch A. Dose-effect relationships for the submandibular salivary glands and implications for their sparing by intensity modulated radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;72:373–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kam MK, Leung SF, Zee B, Chau RM, Suen JJ, Mo F, et al. Prospective randomized study of intensity-modulated radiotherapy on salivary gland function in early-stage nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4873–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.5501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pow EH, Kwong DL, McMillan AS, Wong MC, Sham JS, Leung LH, et al. Xerostomia and quality of life after intensity-modulated radiotherapy vs. conventional radiotherapy for early-stage nasopharyngeal carcinoma: Initial report on a randomized controlled clinical trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;66:981–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nutting CM, Morden JP, Harrington KJ, Urbano TG, Bhide SA, Clark C, et al. Parotid-sparing intensity modulated versus conventional radiotherapy in head and neck cancer (PARSPORT): A phase 3 multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:127–36. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70290-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khalifa J, Vieillevigne L, Boyrie S, Ouali M, Filleron T, Rives M, et al. Dosimetric comparison between helical tomotherapy and volumetric modulated arc-therapy for non-anaplastic thyroid cancer treatment. Radiat Oncol. 2014;9:247. doi: 10.1186/s13014-014-0247-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stromberger C, Cozzi L, Budach V, Fogliata A, Ghadjar P, Wlodarczyk W, et al. Unilateral and bilateral neck SIB for head and neck cancer patients: Intensity-modulated proton therapy, tomotherapy, and rapidArc. Strahlenther Onkol. 2016;192:232–9. doi: 10.1007/s00066-016-0945-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tol JP, Doornaert P, Witte BI, Dahele M, Slotman BJ, Verbakel WF, et al. A longitudinal evaluation of improvements in radiotherapy treatment plan quality for head and neck cancer patients. Radiother Oncol. 2016;119:337–43. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2016.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cilla S, Deodato F, Macchia G, Digesù C, Ianiro A, Piermattei A, et al. Volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT) and simultaneous integrated boost in head-and-neck cancer: Is there a place for critical swallowing structures dose sparing? Br J Radiol. 2016;89:20150764. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20150764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hunt MA, Jackson A, Narayana A, Lee N. Geometric factors influencing dosimetric sparing of the parotid glands using IMRT. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;66:296–304. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Millunchick CH, Zhen H, Redler G, Liao Y, Turian JV. A model for predicting the dose to the parotid glands based on their relative overlapping with planning target volumes during helical radiotherapy. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2018;19:48–53. doi: 10.1002/acm2.12203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bandlamudi BP, Sharan K, Yathiraj PH, Singh A, Reddy A, Fernandes DJ, et al. A study on the impact of patient-related parameters in the ability to spare parotid glands by intensity-modulated radiotherapy for head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. J Cancer Res Ther. 2018;14:1220–4. doi: 10.4103/jcrt.JCRT_362_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fogliata A, Thompson S, Stravato A, Tomatis S, Scorsetti M, Cozzi L, et al. On the gEUD biological optimization objective for organs at risk in photon optimizer of eclipse treatment planning system. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2018;19:106–14. doi: 10.1002/acm2.12224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pizarro F, Hernández A. Optimization of radiotherapy fractionation schedules based on radiobiological functions. Br J Radiol. 2017;90:20170400. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20170400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boughalia A, Marcie S, Fellah M, Chami S, Mekki F. Assessment and quantification of patient set-up errors in nasopharyngeal cancer patients and their biological and dosimetric impact in terms of generalized equivalent uniform dose (gEUD), tumour control probability (TCP) and normal tissue complication probability (NTCP) Br J Radiol. 2015;88:20140839. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20140839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Report of AAPM Task Group 166 of the Therapy Physics Committee. The Use and QA of Biologically Related Models for Treatment Planning. AAPM Report No. 166. 2012 doi: 10.1118/1.3685447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.RTOG Protocol 0225: A Phase II Study of IMRT +/Chemotherapy for Nasopharyngeal Cancer. [Last accessed on 2006 Dec 15]. Available from: http://www.rtog.org .

- 24.Feuvret L, Noël G, Mazeron JJ, Bey P. Conformity index: A review. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64:333–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wiezorek T, Brachwitz T, Georg D, Blank E, Fotina I, Habl G, et al. Rotational IMRT techniques compared to fixed gantry IMRT and tomotherapy: Multi-institutional planning study for head-and-neck cases. Radiat Oncol. 2011;6:20. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-6-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Broggi S, Perna L, Bonsignore F, Rinaldin G, Fiorino C, Chiara A, et al. Static and rotational intensity modulated techniques for head-neck cancer radiotherapy: A planning comparison. Phys Med. 2014;30:973–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmp.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ueda Y, Fukunaga JI, Kamima T, Adachi Y, Nakamatsu K, Monzen H, et al. Evaluation of multiple institutions' models for knowledge-based planning of volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT) for prostate cancer. Radiat Oncol. 2018;13:46. doi: 10.1186/s13014-018-0994-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heijmen B, Voet P, Fransen D, Penninkhof J, Milder M, Akhiat H, et al. Fully automated, multi-criterial planning for volumetric modulated arc therapy – An international multi-center validation for prostate cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2018;128:343–8. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2018.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wall PD, Carver RL, Fontenot JD. Impact of database quality in knowledge-based treatment planning for prostate cancer. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2018;8:437–44. doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2018.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Babier A, Boutilier JJ, McNiven AL, Chan TC. Knowledge-based automated planning for oropharyngeal cancer. Med Phys. 2018;45:2875–83. doi: 10.1002/mp.12930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]