Abstract

Context:

Elevated sperm DNA fragmentation index (DFI) is found to affect normal embryonic development, implantation and fetal development after intrauterine insemination (IUI), in vitro fertilization and intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI). Estimation of DFI by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated fluorescent deoxy uridine nucleotide nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay was found to have a high predictive value for pregnancy after fertility treatments.

Aim:

This study aims to find the effect of increased sperm DNA fragmentation by TUNEL assay on reproductive outcome after IUI and ICSI.

Primary Objective:

To find the association of DFI and pregnancy rate in IUI and ICSI.

Secondary Objectives:

To find the association of DFI with fertilization and implantation in ICSI. To find the association of DFI with miscarriage rate.

Settings and Design:

A prospective observational study performed at a tertiary care university teaching hospital.

Subjects and Methods:

105 male partners of infertile couple planned for IUI and ICSI underwent estimation of sperm-DFI by TUNEL assay. The treatment outcomes were compared between the DFI-positive (≥20%) and DFI-negative (<20%) groups.

Statistical Analysis Used:

Statistical analysis was performed by SPSS version 17, Software. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results:

The men with abnormal semen analysis were significantly higher in the DFI-positive group (77.15% vs. 22.85%). There was no significant difference in the pregnancy rate in IUI cycles (17.6% vs. 11.8%); but in the ICSI, the pregnancy rate was significantly reduced in the DFI-positive group (16.7% vs. 47.4%).

Conclusions:

Elevated DFI significantly affects the pregnancy rate in ICSI cycles.

Keywords: DNA fragmentation index, intracytoplasmic sperm injection, intrauterine insemination, male infertility, sperm function tests, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated fluorescent deoxy uridine nucleotide nick end labeling

INTRODUCTION

Infertility affects about 15% of all couples trying to conceive. Male factor is the sole or contributing factor in roughly half of the cases.[1] In 60%–75% of subfertile men, the etiology of abnormal semen parameters remains unexplained.[2] The standard measurements of sperm concentration, motility and morphology may not reveal the defects affecting the integrity of the male genome.[3] Spermatogenesis includes spermatogonial proliferation and differentiation, meiosis and spermiogenesis.[4] Spermiogenesis is a complex process that transforms round spermatids into mature spermatozoa. It involves six stages; Sa-1Sa-2: development of Golgi Complex and mitochondria and appearance of acrosome vesicle and chromatoid body, proximal centriole and axial filament. Sb-1, Sb-2: acrosome formation is completed, intermediate piece is formed, and tail develops. Sc-1, Sc-2: tail development is completed, and a mature sperm is formed. During spermiogenesis, progressive condensation of the nucleus occurs with the inactivation of the genome. This is facilitated by conversion of histones to transitional proteins, TP1 and TP2, and finally to protamines P1 and P2, linked by disulfide bonds. This process would cause compaction of sperm chromatin. In humans, about 85% of histones are replaced by protamines.[4,5] Following spermiation, spermatozoa undergo maturity in the epididymal transit for 1–2 weeks before being released into the ejaculate.[6] The causes responsible for elevated DNA fragmentation index (DFI) are broadly divided into two groups: intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Intrinsic factors include genetic mutations and polymorphisms. Extrinsic or environmental factors can be due to either testicular or posttesticular causes. The testicular causes of elevated DFI are smoking, alcohol intake, exposure to heat, chemicals and radiation, varicocele, and chemotherapy. Post-testicular factors causing elevated DFI are elevated reactive oxygen species in the seminal plasma.[7,8,9] These factors would cause an abnormally elevated DFI despite normal semen parameters.[10] Elevated DFI affects early fertility check points due to disruption of paternal genome, and causes decreased pregnancy rate in IUI. It is known to cause lower fertilization, early embryonic development, pregnancy and live birth rate, and elevated miscarriage rate in Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART): In vitro fertilization (IVF) and ICSI.[11,12,13] A few studies have claimed that ICSI would significantly improve the outcomes in men with elevated DFI.[14,15,16] However, many studies reported that elevated DFI by TUNEL or Comet assays was negatively correlated with fertilization and pregnancy even in ICSI cycles, though to a lesser extent than in IUI and IVF.[17,18,19,20,21] Moreover, in couple with repeated ICSI failures of whom men had elevated DFI, ICSI with testicular spermatozoa yielded higher pregnancies and live births, and a lower miscarriage rate.[22,23]

About 39%–50% of infertile men have idiopathic infertility. Elevated DFI could be a cause of the decreased reproductive potential in 64% of these cases. About 80% of couples with unexplained infertility have elevated DFI, and in 40% of them DFI would be abnormally high (>50%).[24,25,26,27,28] Tests which would assess the DNA damage in human spermatozoa include TUNEL, sperm chromatin structure (SCSA), COMET assay, DNA-breakage detection Fluorescent in situ hybridization (DBD-FISH), sperm chromatin dispersion (SCD), in situ nick translation (ISNT), Chromomycin A3. Among these tests, except for ISNT, TUNEL and COMET under neutral PH, the remaining tests require initial DNA denaturation, which does not occur in vivo in the oocyte at a pH of 7.[3] Hence, the DFI measured by those tests may not be clinically relevant. Despite having evolved as a robust test, there are concerns regarding SCSA that it measures potential damage rather than real DNA damage. TUNEL test is found to have a high predictive value for pregnancy, especially after IUI.[3,29] Unlike other assays, TUNEL detects double stranded DNA breaks which would significantly affect fertilization and implantation, as these could not be repaired by the oocyte.[30]

We did this prospective observational study, on the evaluation of the effect of sperm DFI on the clinical outcomes of IUI and ICSI. We used TUNEL assay as it is known to accurately estimate the sperm DFI and would not require denaturation of DNA during the procedure. Moreover, a flow cytometry-based TUNEL assay emerged as a robust and well standardized test for estimation of sperm DNA fragmentation.[31,32] We compared the various outcomes of IUI and ICSI such as fertilization, pregnancy, implantation and miscarriage between the TUNEL-positive and TUNEL-negative groups.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

All infertile couple attending our ART center, planned for either IUI or ICSI, were included in the study. Using a n master software with power of 80%, α-error of 5%, IUI pregnancy rate of 12%, and ICSI pregnancy rate of 40%, we arrived at a sample size of 37 individuals for ICSI, and 66 individuals for IUI. A total of 105 infertile couple (37 ICSI and 68 IUI cases) were included in the study. A written and informed consent was obtained from all the study participants. The study was approved by the institutional ethics committee. All men underwent semen analysis as per our hospital protocol. Female partner is evaluated by history, physical examination, and baseline ultrasound. Tubal factor was evaluated either by HSG or hysterolaparoscopy, before ovulation induction and IUI. The study questionnaire was filled for all the individuals. The exclusion criteria were men not consenting to undergo the test, those with severe oligozoospermia (<1 million/ml) where semen concentration is not enough to perform TUNEL assay, those with azoospermia, and cases where donor semen was used. All men of the infertile couple were asked to collect semen sample into a sterile plastic container by masturbation. A semen analysis was performed in all the samples, as per the WHO 2010 criteria.[2] The semen sample was subsequently transferred to the Central Research Facility within 1 h after semen collection, for further processing. DNA fragmentation was evaluated subsequently by TUNEL assay. The TUNEL assay protocol was standardized in our same laboratory by running the positive and negative control, as per the manufacturer's instructions [Figures 1 and 2]. All the women underwent either IUI or ICSI. Ovulation induction in IUI cycles was performed by clomiphene citrate 50–100 mg or Letrozole 5 mg with or without human menopausal gonadotropin (hMG), or hMG alone. Semen preparation was done by double-density gradient centrifugation. As per our department protocol, the following time line was be maintained in all the study participants who underwent IUI: semen collection to insemination time ≤90 min, semen preparation to insemination time <30 min. In women who underwent ICSI, controlled ovarian hyperstimulation was performed by either long luteal gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist or GnRH antagonist protocol. The study participants underwent either a day 2 or day 3 fresh embryo transfer, or a freeze all and subsequent frozen embryo transfer. Freeze-all was performed in those cases with elevated serum progesterone (>1.5 ng/ml) on the day of ovulation trigger, fibroid planned for surgery or medical management, hydrosalpinx planned for salpingectomy or clipping, severe endometriosis planned for surgery, and severe adenomyosis planned for medical management prior to embryo transfer.

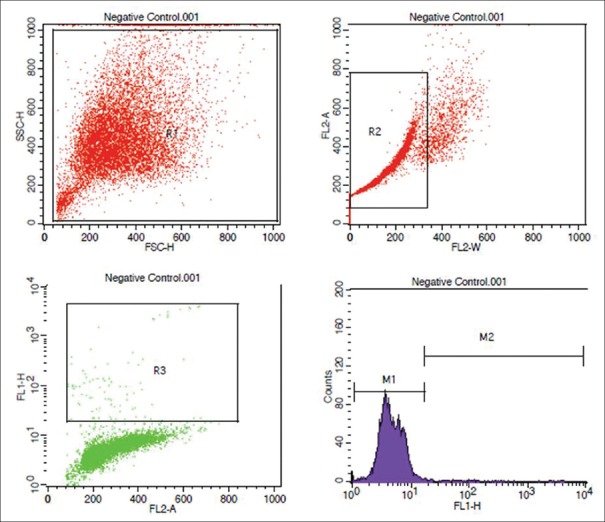

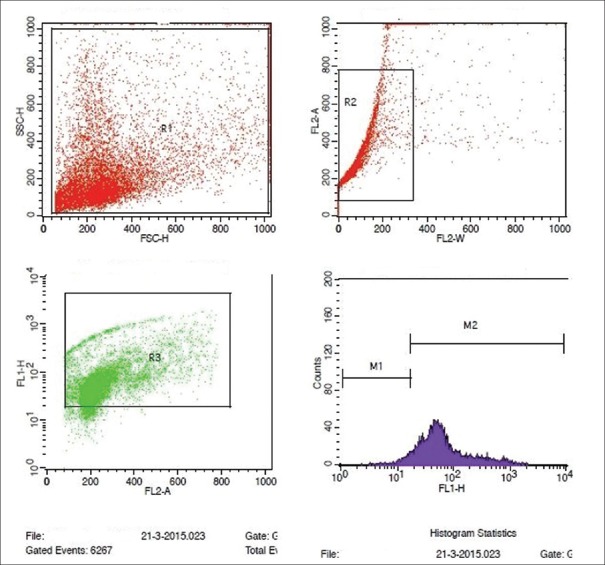

Figure 1.

Flowcytometric analysis of negative control

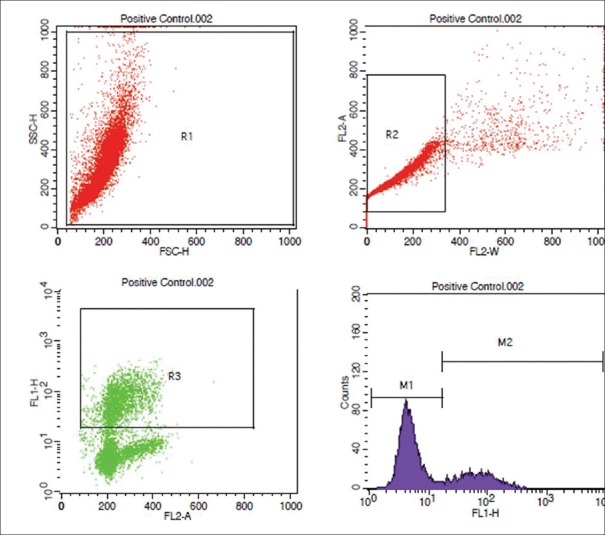

Figure 2.

Flowcytometric analysis of positive control

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated fluorescent deoxy uridine nucleotide nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay principle

The APO-BrdU TUNEL Assay Kit (Invitrogen) was used to perform the assay. DNA breaks expose a large number of 3' hydroxyl ends. TdT adds 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine-5' triphosphate (BrdUTP) to these sites. These were finally detected through binding of a fluorescent marker, Alexa Fluor 488 dye-labeled anti-BrdU antibody, and running through a flow cytometer.

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase mediated fluorescent deoxy uridine nucleotide nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay protocol

Initial preparation and storage of semen sample

One ml or equal volumes of semen was mixed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and washed thrice by centrifugation at 300 × g for 15 min. Sperm cells were adjusted to a concentration of 1–2 × 106 cells/ml and suspended in 0.5 mL of PBS. The cell suspension was added into 5 mL of 1% (w/v) paraformaldehyde in PBS and placed on ice for 15 min and washed and resuspended in PBS. The cells were mixed with 5 mL of ice-cold 70% (v/v) ethanol for 30 min and stored at –20°C in a freezer, till further processing.

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase mediated fluorescent deoxy uridine nucleotide nick end labeling reagent staining and flow cytometry

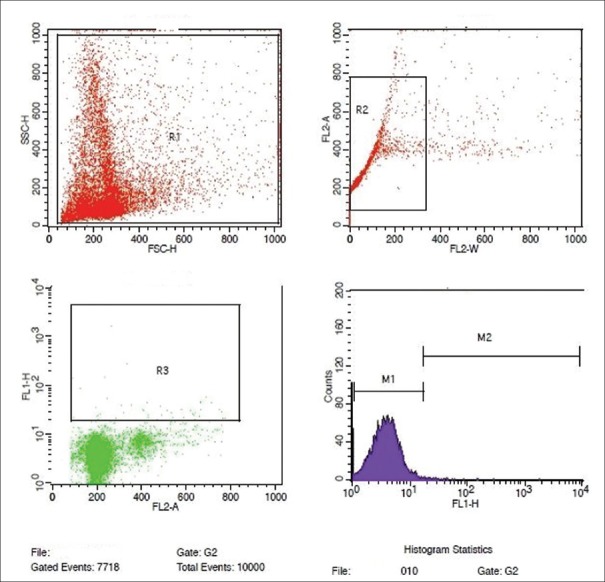

The test cell suspensions (approximately 1 × 106 cells/mL) were placed in 12 mm × 75 mm flow cytometry centrifuge tubes and centrifuged at 300 ×g for 5 min and the 70% (v/v) ethanol was removed by gentle aspiration. The test cells of each tube were washed twice with 1 mL of wash buffer. 50 μL of DNA – labeling solution (10 μL of reaction buffer + 0.75 μL of TdT enzyme + 8.0 μL of BrdUTP and 31.25 μL of dH2O) was added to positive and negative control and test cell pellets, and incubated at 37°C for 60 min in a temperature controlled bath. All the tubes were washed twice with 1.0 mL of rinse buffer. 100 μL of antibody staining solution (5.0 μL Alexa Fluor 488 dye-labeled anti-BrdU antibody + 95 μL of rinse buffer) was added to positive control, negative control, and test pellets and incubated for 30 min at room temperature, in dark. 0.5 mL of the Propidium iodide/RNase A staining buffer was added to each sample, and incubated for another 30 min at room temperature, in dark. The samples were then acquired in a flow cytometer (BD FACS Calibur), equipped with an air-cooled argon laser providing 15 mW at 488 nm and red laser with standard filter setup. Ten thousand (10,000) events were acquired, and the percentage of nicked DNA was analyzed using flowjo or CellQuest Pro software (Becton Dickinson, USA). By plotting the FL1 versus FL2A in a dot plot graph, the nicked DNA population was segregated, and the histogram plotted revealed the percentage of nicked DNA in each sample [Figures 3 and 4].

Figure 3.

Flowcytometric analysis of semen sample showing normal DNA fragmentation by TUNEL assay

Figure 4.

Flowcytometric analysis of semen sample showing elevated DNA fragmentation by TUNEL assay

Interpretation of the assay

A cut-off of ≥20% is taken as a positive test.[3,33] This cutoff of 20% has a higher sensitivity of 96.5%, a specificity of 89.4%, and a PPV of 92.5%.[34]

Statistical analysis used

Correlation analysis was used to analyze the correlation of DFI with various numerical variables. Various parametric and nonparametric tests such as Chi-square test, Mann-Whitney test, and independent sample t-test were used to analyze the association of DFI with numerical and qualitative variables. The analysis was performed by SPSS version 17 software. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

The prevalence of elevated sperm DNA fragmentation was found to be 33.30%, in our study.

Correlation of DNA fragmentation index with age and body mass index

There was a nonsignificant weak positive correlation between age, body mass index, and DFI [Table 1]. There was no significant association between the various occupational risk factors, recreational drugs, and associated clinical conditions with DFI [Table 2].

Table 1.

Correlation of age and body mass index with DNA fragmentation index

| Variable | Correlation coefficient | Inference | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.121 | Weak positive correlation | P=0.217; NS |

| BMI | 0.169 | Weak positive correlation | P=0.085; NS |

Correlation of age and BMI with DFI. DFI=DNA fragmentation index, BMI=Body mass index, NS=Not significant

Table 2.

Effect of risk factors on DNA fragmentation index

| Risk factor | DFI positive (%) | DFI negative (%) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Occupational exposure | |||

| Heat exposure | 13 (40.62) | 19 (59.38) | P=0.294; NS |

| Chemical exposure | 4 (25.0) | 12 (75.0) | P=0.442; NS |

| Habits | |||

| Smoking | 7 (25.0) | 21 (75.0) | P=0.275; NS |

| Alcohol intake | 4 (14.81) | 23 (85.19) | P=0.018 |

| Nicotinic drugs | Nil | 6 | P=0.074; NS |

| Associated conditions | |||

| Varicocele | 7 (26.92) | 19 (73.08) | P=0.424; NS |

| Hydrocele | 1 (33.33) | 2 (66.67) | P=1.000; NS |

Association of risk factors and DFI. DFI=DNA fragmentation index, NS=Not significant

Comparison of semen analyses between DNA fragmentation index-positive and DNA fragmentation index-negative groups

There was a significant decrease in the number of individuals with normal semen parameters in the DFI-positive group [Table 3]. In our study, the prevalence of individuals who were DFI positive and had normal semen analysis was 7.60%.

Table 3.

Effect of DNA fragmentation index on semen parameters

| Semen analysis | DFI positive (n=35) | DFI negative (n=70) |

|---|---|---|

| Normal | 8 (22.85) | 32 (45.71) |

| Abnormal | 27 (77.15) | 38 (54.29) |

| Asthenozoospermia | Nil (0) | 1 (1.43) |

| Teratozoospermia | 2 (5.72) | 12 (17.14) |

| Asthenoteratozoospermia | 9 (25.72) | 16 (22.85) |

| Oligoasthenoteratozoospermia | 5 (14.28) | 5 (7.14) |

| Severe oligoasthenoteratozoospermia | 11 (31.43) | 4 (5.73) |

| Significance | P=0.003; significant | |

Comparison of normal and abnormal semen analyses between the DFI-positive and DFI-negative groups. DFI=DNA fragmentation index

Of the 105 couples, 68 underwent IUI and 37 underwent ICSI. The outcomes were separately analyzed in these two groups.

Intrauterine insemination outcome

Of the 68 women who underwent IUI, 17 (25%) of their male partners were DFI positive, and 51 men were DFI negative. There was no difference in the various causes of infertility between the study groups who underwent IUI [Table 4]. There was no significant difference in the protocol used for IUI between the study groups [Table 5]. There was no significant difference in the pregnancy rate, clinical pregnancy rate and miscarriage rate between the DFI-positive and DFI-negative groups [Table 6]. The potential confounders known to affect pregnancy rate, namely female age ≥35 years, endometriosis, mild male factor and unexplained infertility were analyzed by logistic regression and found no significant effect [Table 7].

Table 4.

Association of DNA fragmentation index with causes of infertility in intrauterine insemination group

| Indication for IUI | DFI positive (n=17) | DFI negative (n=51) |

|---|---|---|

| Male factor infertility | 2 (11.77) | 6 (11.77) |

| Female factor infertility | ||

| PCOS | 2 (11.77) | 6 (11.76) |

| Tubal factor | Nil | 2 (3.92) |

| Uterine factor | 1 (5.88) | 2 (3.92) |

| Combined factor | 7 (41.17) | 11 (21.57) |

| Unexplained factor | 5 (29.41) | 24 (47.06) |

P=0.614; NS. Comparison of indications of IUI between DFI positive and DFI negative groups. DFI=DNA fragmentation index, PCOS=Polycystic ovarian syndrome, IUI=Intrauterine insemination, NS=Not significant

Table 5.

Ovulation induction protocol used in the intrauterine insemination individuals

| Protocol | DFI positive (n=17), n (%) | DFI negative (n=51), n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| CC | 9 (13.20) | 30 (44.10) |

| CC + hMG | 4 (5.90) | 6 (8.80) |

| Letrozole | 3 (4.40) | 7 (10.30) |

| Letrozole + hMG | 1 (1.50) | 5 (7.40) |

| hMG | Nil | 3 (4.40) |

| Significance | P=0.621; NS | |

Comparison of various protocols used for ovulation induction for IUI between the study groups. DFI=DNA fragmentation index, IUI=Intrauterine insemination, CC=Clomiphene citrate, hMG=Human menopausal gonadotropin, NS=Not significant

Table 6.

Effect of DNA fragmentation index on intrauterine insemination pregnancy rate

| Pregnancy by IUI (1st cycle) | DFI positive (n=17), n (%) | DFI negative (n=51), n (%) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pregnancy | 4 (23.5) | 6 (11.80) | P=0.236 |

| Clinical pregnancy | 3 (17.60) | 6 (11.80) | P=0.236 |

| Miscarriage | Nil | 1 | NS |

Comparison of IUI pregnancy and miscarriage rates between DFI positive and DFI negative groups. DFI=DNA fragmentation index, IUI=Intrauterine insemination, NS=Not significant

Table 7.

Logistic regression analysis of various potential confounders in individuals who underwent intrauterine insemination

| Variable | Confounding variable | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Pregnancy rate | Female age ≥35 years | P=1.00; NS |

| Hydrosalpinx | P=0.99; NS | |

| Endometriosis | P=0.99; NS | |

| Male factor | P=0.464; NS | |

| Unexplained infertility | P=0.299; NS |

Effect of potential confounders on the pregnancy rate in IUI. IUI=Intrauterine insemination, NS=Not significant

Intracytoplasmic sperm injection

The percentage of DFI positivity in ICSI was 48.60%, in our study. There were higher number of cases with male factor infertility in the DFI-positive group and higher number of cases with unexplained infertility in DFI-negative group [Table 8].

Table 8.

Causes of infertility in intracytoplasmic sperm injection group

| Indication for ICSI | DFI positive (%) | DFI negative (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Male factor infertility | 8 (44.44) | 4 (21.05) |

| Female factor infertility | 2 (11.11) | 8 (42.11) |

| Tubal factor | 2 (11.11) | 7 (36.84) |

| Decreased ovarian reserve | Nil | 1 (5.27) |

| Combined factor | 6 (33.34) | 1 (5.27) |

| Unexplained factor | 2 (11.11) | 6 (31.57) |

| Total | 18 | 19 |

| Significance | P=0.031; significant | |

Distribution of cause of infertility between DFI-positive and DFI-negative groups in ICSI. DFI=DNA fragmentation index, ICSI=Intracytoplasmic sperm injection

Outcome analysis

The various outcome parameters of ICSI were analyzed between the DFI-positive and the DFI-negative groups. There was no significant difference in the COH protocol used, between the two groups.

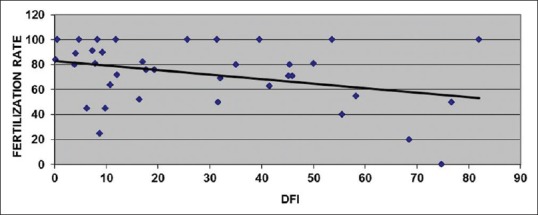

A correlation analysis of DFI and fertilization rate showed a weak and non-significant negative correlation (r = -0.203; P = 0.084) [Figure 5].

Figure 5.

Correlation analysis of DNA fragmentation index with fertilization rate

There were significantly higher numbers of good-quality embryos obtained in DFI-negative group. Implantation and pregnancy rates were significantly lower in the DFI-positive group than the DFI negative group. However, there was no significant difference in clinical pregnancy and miscarriage rates between the two groups [Table 9]. The effect of potential confounders known to affect pregnancy in ICSI cycles such as female age ≥35 years, endometriosis, male factor infertility and unexplained infertility, was analyzed by logistic regression analysis, and found to have no significant effect [Table 10].

Table 9.

Comparison of intracytoplasmic sperm injection outcome between the study groups

| Parameter | DFI positive (n=18) | DFI negative (n=19) | Significance (P) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agonist protocol, n (%) | 5 (27.77) | 2 (10.52) | 0.181 |

| Antagonist protocol, n (%) | 13 (72.23) | 17 (89.48) | |

| Fertilization rate, % (SD) | 68.31 (28.87) | 76.57 (21.39) | 0.328 |

| Good quality embryos, n (SD) | 6.63 (4.41) | 11 (6.67) | 0.018 |

| Poor quality embryos, n (SD) | 0.56 (0.99) | 0.53 (1.07) | 0.930 |

| Implantation rate, % (SD) | 4.90 (14.14) | 15.79 (22.54) | 0.002 |

| Number of pregnancies, n (%) | 3 (16.70) | 9 (47.40) | 0.046 |

| Clinical pregnancy, n (%) | 2 (11.10) | 7 (36.80) | 0.068 |

| Miscarriage, n (%) | Nil | 1 (5.30) | 0.324 |

Comparison of ICSI outcomes between DFI-positive and DFI-negative groups. DFI=DNA fragmentation index, ICSI=Intracytoplasmic sperm injection

Table 10.

Logistic regression analysis of various potential confounders in individuals who underwent intracytoplasmic sperm injection

| Variable | Confounding variable | Significance (P) |

|---|---|---|

| Pregnancy rate | Female age ≥35 years | 0.498; NS |

| Pregnancy rate | Hydrosalpinx | 0.397; NS |

| Pregnancy rate | Endometriosis | 1.00; NS |

| Pregnancy rate | Ovarian drilling | 0.824; NS |

| Pregnancy rate | Male factor | 0.079; NS |

| Pregnancy rate | Unexplained infertility | 0.974; NS |

Effect of potential confounders on the pregnancy rate in ICSI. ICSI=Intracytoplasmic sperm injection, NS=Not significant

DISCUSSION

Sperm DNA damage has been attributed to a variety of intratesticular and extratesticular factors. In a group of 320 unselected patients, Winkle et al. (modified Nicolette flow cytometry assay) reported the lack of correlation between male age and DFI. While Schmid et al. (COMET assay) reported that aged men had increased single stranded DNA breaks.[35,36] In our study, there was only a weak positive correlation of DFI with age. This is because majority of the study participants were <45 years age group, in whom the age is not likely to affect sperm chromatin integrity [Table 11]. Moskovtsev reported a significantly elevated DFI in men >45 years age group.[37]

Table 11.

Age distribution of the study participants

| Age (years) | Number of participants (%) |

|---|---|

| <20 | Nil |

| 21-25 | 1 (1.0) |

| 26-30 | 22 (21.0) |

| 31-35 | 49 (46.70) |

| 36-40 | 24 (22.90) |

| 41-45 | 8 (7.60) |

| >45 | 1 (1.0) |

| Total | 105 |

Age distribution of the study participants

Benchaib et al. (TUNEL) reported a negative correlation between the DFI and semen parameters viz., concentration and progressive motility.[38] In a prospective observational study by Henkel et al., of 208 IVF and 54 ICSI cycles, there was significant correlation of TUNEL-positive spermatozoa with abnormal semen parameters (viz., concentration, motility, morphology).[39] Similar findings were observed in our study.

DFI was acclaimed to be an independent risk factor for treatment failure in couples undergoing IUI. In 131 couples who underwent IUI, Bungum et al. (SCSA; >27% DFI, >10% HDS) reported significantly higher pregnancy, clinical pregnancy, and delivery rates (odds ratio = 20, 16 and 14) in men with normal DFI and HDS.[40] Duran et al.(TUNEL, DFI >12%) analyzed 154 IUI cycles and found that elevated DFI significantly affected conception.[17] Donald Evenson et al. performed a meta-analysis (SCSA, COMET; DFI >30%) and found that female partners of men with normal DFI were 7.3 times more likely to conceive than those with elevated DFI.[40,41] In our study, there was no significant difference in the number of IUI pregnancies between the study groups. This finding might be due to higher number of cases with polycystic ovary syndrome and significantly higher number of cases with unexplained infertility in DFI-negative group. The majority of these cases did not conceive. In these individuals, there would have been other factors such as abnormal hormonal milieu, abnormal oocyte and endometrial receptivity which would have probably affected the pregnancy rate [Table 12]. Henkel et al. reported no direct correlation between the percentage of TUNEL-positive spermatozoa and fertilization rate (r = 0.0113; P = 0.8718), embryo fragmentation rate (r = 0.0406; P = 0.5855) and pregnancy (r = −0.0889; P = 0.2016) for IVF and ICSI. However, there was a tendency (P = 0.0799) toward a lower number of pregnancies in the TUNEL-positive group (22.2 vs. 48.0%).[39] Larson et al. reported that elevated DFI (SCSA, ≥27%) significantly affected the pregnancy rates in ICSI (0 vs. 58.33%).[42] In our study, we found significantly lesser number of pregnancies in the DFI-positive group, in ICSI.

Table 12.

Distribution of various causes of infertility between the pregnant and non-pregnant patients who underwent intracytoplasmic sperm injection

| Infertility factor | DFI positive |

DFI negative |

Significance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pregnant | Nonpregnant | Pregnant | Nonpregnant | ||

| Male factor (43) | 3 (6.9) | 10 (23.3) | 4 (9.3) | 26 (60.5) | P=0.937 (DFI positive); P=0.678 (DFI negative); NS |

| Female factor | |||||

| PCOS (29) | 3 (10.3) | 6 (20.7) | 1 (3.4) | 19 (65.6) | P=0.376 (DFI positive); P=0.059 (DFI negative); NS |

| Tubal factor (8) | 1 (12.5) | 1 (12.5) | Nil | 6 (75) | |

| Endometriosis | Nil | 2 | Nil | Nil | |

| Uterine factor | Nil | 1 (33.4) | 1 (33.3) | 1 (33.3) | |

| Decreased ovarian reserve (3) | Nil | Nil | 1 (33.30) | 2 (66.7) | |

| Unexplained infertility (29) | 2 (6.9) | 3 (10.3) | 5 (17.2) | 19* (65.6) | P=0.223 (DFI positive); NS P*=0.001 (DFI negative); significant |

Comparison of the various factors of infertility between the pregnant and non-pregnant patients of the study groups, who underwent IUI. IUI=Intracytoplasmic sperm injection, DFI=DNA fragmentation index, NS=Not significant

Host et al., (TUNEL, DFI >45%) analyzed 236 IVF and ICSI cycles and observed that fertilization rate was significantly decreased in couples with men who had elevated DFI in IVF, but not in ICSI.[43] In a study done by Benchaib et al. 2007 (TUNEL), there was a negative correlation between the DFI and ICSI fertilization.[38] Henkel et al. Studied 208 IVF and 54 ICSI cycles, and found no correlation between DFI and fertilization rate, embryo morphology, and pregnancy rate in both the groups. In our study, we found a weak negative correlation between DFI and fertilization.

In a group of 233 couples undergoing ICSI, Kennedy et al. found that elevated DFI was associated with higher spontaneous miscarriage.[44] Zini et al. performed a meta-analysis of 11 studies that evaluated sperm DNA fragmentation by SCSA and TUNEL assays, in 1549 ART cycles (808 IVF, 741 ICSI), and found that elevated was significantly associated with increased miscarriage.[45] Benchaib et al. reported four fold increased risk of miscarriage when the DFI exceeded 15%, in IVF and ICSI (9.1% vs. 50% for IVF; 8.6% vs. 30% for ICSI).[38] In our study, we did not find significant association between DFI and miscarriage in both IUI and ICSI. This may be due to significantly lower number of miscarriages in our study participants.

CONCLUSIONS

Elevated DFI significantly reduces the pregnancy rate in ICSI cycles

The effect of elevated DFI on the outcome of IUI cycles needs to be evaluated on a larger and homogenous data

The effect of elevated DFI on miscarriage needs to be evaluated on a larger data.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

Dr. Manjula- Chief Embryologist, Department of Reproductive Medicine and Surgery, SRIHER

Mr. Sudhakar – Assistant Embryologist, Department of Reproductive Medicine and Surgery, SRIHER

Dr. Malini – Scientist, CRF, SRIHER

Dr. Rengarajan – Scientist, CRF, SRIHER.

REFERENCES

- 1.Oehninger S. Strategies for the infertile man. Semin Reprod Med. 2001;19:231–7. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-18042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. WHO Laboratory Manual for the Examination and Processing of Human Semen. World Health Organization. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Björndahl L, Mortimer D. Sperm function tests. In: Bjorndahl L, Mortimer D, editors. A Practical Guide to Basic Laboratory Andrology. UK; New York: Cambridge University Press; 2010. pp. 113–45. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharma R, Agarwal A. Spermatogenesis: An overview. In: Zini A, Agarwal A, editors. Sperm Chromatin for the Researcher: A Practical Guide. 1st ed. New York: Springer; 2013. pp. 127–60. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meistrich ML. Calculation of the incidence of infertility in human populations from sperm measures using the two-distribution model. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1989;302:275–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dacheux JL, Dacheux F. New insights into epididymal function in relation to sperm maturation. Reproduction. 2014;147:R27–42. doi: 10.1530/REP-13-0420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al Omrani B, Al Eisa N, Javed M, Al Ghedan M, Al Matrafi H, Al Sufyan H, et al. Associations of sperm DNA fragmentation with lifestyle factors and semen parameters of Saudi men and its impact on ICSI outcome. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2018;16:49. doi: 10.1186/s12958-018-0369-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sakkas D, Alvarez JG. Sperm DNA fragmentation: Mechanisms of origin, impact on reproductive outcome, and analysis. Fertil Steril. 2010;93:1027–36. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zini A, Albert O, Robaire B. Assessing sperm chromatin and DNA damage: Clinical importance and development of standards. Andrology. 2014;2:322–5. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-2927.2014.00193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharma RK, Said T, Agarwal A. Sperm DNA damage and its clinical relevance in assessing reproductive outcome. Asian J Androl. 2004;6:139–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erenpreiss J, Elzanaty S, Giwercman A. Sperm DNA damage in men from infertile couples. Asian J Androl. 2008;10:786–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7262.2008.00417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giwercman A, Lindstedt L, Larsson M, Bungum M, Spano M, Levine RJ, et al. Sperm chromatin structure assay as an independent predictor of fertility in vivo: A case-control study. Int J Androl. 2010;33:e221–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2009.00995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giwercman A, Richthoff J, Hjøllund H, Bonde JP, Jepson K, Frohm B, et al. Correlation between sperm motility and sperm chromatin structure assay parameters. Fertil Steril. 2003;80:1404–12. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(03)02212-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chi HJ, Kim SG, Kim YY, Park JY, Yoo CS, Park IH, et al. ICSI significantly improved the pregnancy rate of patients with a high sperm DNA fragmentation index. Clin Exp Reprod Med. 2017;44:132–40. doi: 10.5653/cerm.2017.44.3.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewis SE, John Aitken R, Conner SJ, Iuliis GD, Evenson DP, Henkel R, et al. The impact of sperm DNA damage in assisted conception and beyond: Recent advances in diagnosis and treatment. Reprod Biomed Online. 2013;27:325–37. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2013.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simon L, Proutski I, Stevenson M, Jennings D, McManus J, Lutton D, et al. Sperm DNA damage has a negative association with live-birth rates after IVF. Reprod Biomed Online. 2013;26:68–78. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2012.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duran EH, Morshedi M, Taylor S, Oehninger S. Sperm DNA quality predicts intrauterine insemination outcome: A prospective cohort study. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:3122–8. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.12.3122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang H, He RB, Wang CL, Zhu J. The relationship of sperm DNA fragmentation index with the outcomes of in vitro fertilisation-embryo transfer and intracytoplasmic sperm injection. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;31:636–9. doi: 10.3109/01443615.2011.590910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lopes S, Jurisicova A, Sun JG, Casper RF. Reactive oxygen species: Potential cause for DNA fragmentation in human spermatozoa. Hum Reprod. 1998;13:896–900. doi: 10.1093/humrep/13.4.896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morris ID, Ilott S, Dixon L, Brison DR. The spectrum of DNA damage in human sperm assessed by single cell gel electrophoresis (Comet assay) and its relationship to fertilization and embryo development. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:990–8. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.4.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun JG, Jurisicova A, Casper RF. Detection of deoxyribonucleic acid fragmentation in human sperm: Correlation with fertilization in vitro. Biol Reprod. 1997;56:602–7. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod56.3.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Esteves SC, Roque M, Garrido N. Use of testicular sperm for intracytoplasmic sperm injection in men with high sperm DNA fragmentation: A SWOT analysis. Asian J Androl. 2018;20:1–8. doi: 10.4103/aja.aja_7_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cho CL, Agarwal A, Majzoub A, Esteves SC. Use of sperm DNA fragmentation testing and testicular sperm for intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Transl Androl Urol. 2017;6:S688–90. doi: 10.21037/tau.2017.06.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aktan G, Doǧru-Abbasoǧlu S, Küçükgergin C, Kadıoǧlu A, Ozdemirler-Erata G, Koçak-Toker N, et al. Mystery of idiopathic male infertility: Is oxidative stress an actual risk? Fertil Steril. 2013;99:1211–5. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Attia A, Al-Inany H, Proctor M. The Cochrane Collaboration, editors. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Chichester, UK: John Wiley and Sons, Ltd; 2006. Gonadotrophins for idiopathic male factor subfertility. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bungum M. Sperm DNA integrity assessment: A new tool in diagnosis and treatment of fertility. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2012;2012:531042. doi: 10.1155/2012/531042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lewis SE. The place of sperm DNA fragmentation testing in current day fertility management. Middle East Fertil Soc J. 2013;18:78–82. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Venkatesh S, Singh A, Shamsi MB, Thilagavathi J, Kumar R, Mitra DK, et al. Clinical significance of sperm DNA damage threshold value in the assessment of male infertility. Reprod Sci. 2011;18:1005–13. doi: 10.1177/1933719111401662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. The clinical utility of sperm DNA integrity testing: A guideline. Fertil Steril. 2013;99:673–7. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.12.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tamburrino L, Marchiani S, Montoya M, Elia Marino F, Natali I, Cambi M, et al. Mechanisms and clinical correlates of sperm DNA damage. Asian J Androl. 2012;14:24–31. doi: 10.1038/aja.2011.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Agarwal A, Cho CL, Majzoub A, Esteves SC. Risk factors associated with sperm DNA fragmentation. Transl Androl Urol. 2017;6:S519–S521. doi: 10.21037/tau.2017.04.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ribeiro S, Sharma R, Gupta S, Cakar Z, De Geyter C, Agarwal A, et al. Inter- and intra-laboratory standardization of TUNEL assay for assessment of sperm DNA fragmentation. Andrology. 2017;5:477–85. doi: 10.1111/andr.12334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sergerie M, Laforest G, Bujan L, Bissonnette F, Bleau G. Sperm DNA fragmentation: Threshold value in male fertility. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:3446–51. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sharma RK, Sabanegh E, Mahfouz R, Gupta S, Thiyagarajan A, Agarwal A, et al. TUNEL as a test for sperm DNA damage in the evaluation of male infertility. Urology. 2010;76:1380–6. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schmid TE, Eskenazi B, Baumgartner A, Marchetti F, Young S, Weldon R, et al. The effects of male age on sperm DNA damage in healthy non-smokers. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:180–7. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Winkle T, Rosenbusch B, Gagsteiger F, Paiss T, Zoller N. The correlation between male age, sperm quality and sperm DNA fragmentation in 320 men attending a fertility center. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2009;26:41–6. doi: 10.1007/s10815-008-9277-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moskovtsev SI, Willis J, Mullen JBM. Age-related decline in sperm deoxyribonucleic acid integrity in patients evaluated for male infertility. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:496–9. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.05.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Benchaib M, Lornage J, Mazoyer C, Lejeune H, Salle B, François Guerin J, et al. Sperm deoxyribonucleic acid fragmentation as a prognostic indicator of assisted reproductive technology outcome. Fertil Steril. 2007;87:93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.05.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Henkel R, Kierspel E, Hajimohammad M, Stalf T, Hoogendijk C, Mehnert C, et al. DNA fragmentation of spermatozoa and assisted reproduction technology. Reprod Biomed Online. 2003;7:477–84. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)61893-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bungum M, Humaidan P, Spano M, Jepson K, Bungum L, Giwercman A, et al. The predictive value of sperm chromatin structure assay (SCSA) parameters for the outcome of intrauterine insemination, IVF and ICSI. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:1401–8. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Evenson D, Wixon R. Meta-analysis of sperm DNA fragmentation using the sperm chromatin structure assay. Reprod Biomed Online. 2006;12:466–72. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)62000-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Larson KL, DeJonge CJ, Barnes AM, Jost LK, Evenson DP. Sperm chromatin structure assay parameters as predictors of failed pregnancy following assisted reproductive techniques. Hum Reprod. 2000;15:1717–22. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.8.1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Høst E, Lindenberg S, Smidt-Jensen S. The role of DNA strand breaks in human spermatozoa used for IVF and ICSI. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000;79:559–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kennedy C, Ahlering P, Rodriguez H, Levy S, Sutovsky P. Sperm chromatin structure correlates with spontaneous abortion and multiple pregnancy rates in assisted reproduction. Reprod Biomed Online. 2011;22:272–6. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2010.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zini A, Boman JM, Belzile E, Ciampi A. Sperm DNA damage is associated with an increased risk of pregnancy loss after IVF and ICSI: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:2663–8. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]