Abstract

Previous research has reported that sleep problems1 longitudinally predict both onset of cannabis use and cannabis-related problems. However, the mediators of this relationship remain unclear. The present study examined (i) the concurrent relationship between insomnia symptoms and hazardous cannabis use and (ii) examined whether use of protective behavioral strategies (PBS) for cannabis mediated this relationship among college student cannabis users. Participants were 984 (69.9% female) college students who reported consuming cannabis at least once in the past month and completed measures of insomnia, cannabis PBS, and cannabis misuse. Data were analyzed by structural equation modeling for binary and count outcomes. The significance of the mediator was evaluated using bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals. Insomnia symptoms were associated with an increase in the odds of hazardous cannabis use and possible cannabis use disorder. Cannabis PBS significantly mediated the relationship between insomnia symptoms and hazardous cannabis use, cannabis use disorder symptoms, and cannabis-related problems. Specifically, higher reports of insomnia symptoms were associated with lower use of cannabis PBS; which in turn was associated with an increase in the odds of hazardous cannabis use and possible cannabis use disorder, as well as a higher report of cannabis-related problems. Implications of these findings on the prevention of cannabis use problems among college students in the U.S. were discussed.

Keywords: Sleep, cannabis protective behavioral strategies, hazardous cannabis use, cannabis-related consequences, college students

Insomnia Symptoms, Cannabis Protective Behavioral Strategies, and Hazardous Cannabis Use among U.S. College Students According to the World Health Organization, cannabis (i.e., marijuana) is the most cultivated, trafficked, and misused illicit drug worldwide (World Health Organization, 2018). Cannabis is the most widely used illicit substance among college students in the U.S. (Schulenberg et al., 2018) Prevalence of use was estimated to be 38% in the past year and 21% in the past 30 days. Since 2010, there has been steady increases in cannabis use in college students and young adults. Publicity on the legalization of cannabis for medical and recreational use in some states may have contributed to this trend (Schulenberg et al., 2018).

The therapeutic effects of cannabis on pain and physical functioning (e.g., nausea and vomiting in cancer patients) has been demonstrated (Aviram & Samuelly-Leichtag, 2017; Nugent et al., 2017; Sharkey, Darmani, & Parker, 2014; Turgeman & Bar-Sela, 2018). Adverse health and psychosocial consequences of acute (e.g., anxiety, panic reactions, paranoia, temporary cognitive impairment) and chronic cannabis use (e.g., psychotic symptoms, risk of cardiovascular disease, cognitive impairment, early school-leaving) have also been documented (Hall, 2015). Identifying risk factors and mediators that may explain the relationship between risk factors and problematic cannabis use will lead to a better understanding of its etiology and inform prevention and intervention efforts. The main purpose of this study was to examine (i) the relationship between insomnia symptoms (e.g., difficulties falling and staying asleep) and hazardous cannabis use and (ii) examine whether use of cannabis protective behavioral strategies mediated this relationship.

Sleep difficulties have been associated with onset of substance use as well as substance- related problems in both cross-sectional (Fakier & Wild, 2011; Johnson & Breslau, 2001; McKnight-Eily et al., 2011; Sivertsen, Skogen, Jakobsen, & Hysing, 2015) and longitudinal studies (Hasler et al., 2017; Miller, Janssen, & Jackson, 2017; Wong, Robertson, & Dyson, 2015). However, most research has examined alcohol use or substance use in general (i.e., includes cannabis use but not restricted to cannabis use). We briefly review cross-sectional and longitudinal studies that examine cannabis-related outcomes separately (i.e., not combined with other substance use).

Cross-sectional data of community samples have shown a positive relationship between sleep difficulties and cannabis use. A study of 703 9th and 11th graders in South Africa reported an association between sleep problems (trouble falling or staying asleep, morning tiredness and daytime sleepiness) and an increased likelihood of use of alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, methamphetamine and other illegal drugs (Fakier & Wild, 2011). Data from the U.S. National Household Survey on Drug Abuse (N=13,381, aged 12–17 years) indicated that adolescents (aged 12–17 years) who reported having trouble sleeping in the survey were more likely than those without such problems to use alcohol, cigarettes and other illicit drugs, including cannabis (Johnson & Breslau, 2001). In another nationally representative sample of U.S. high school students, the Youth and Health Risk Behavior Survey in 2007 (N=12,154), insufficient sleep was associated with higher probabilities of alcohol, cigarette and cannabis use in the last 30 days (McKnight-Eily et al., 2011). It is useful to note that insufficient sleep is not necessarily an outcome of sleep difficulties; factors such as poor sleep hygiene and increasing academic and psychosocial demands may also lead to insufficient sleep.

Findings from longitudinal research generally support these cross-sectional findings. Controlling for parental alcoholism, childhood sleep problems measured by maternal ratings at ages 3–5 predicted onset of any use of alcohol, nicotine, cannabis and other illicit drugs by ages 12–14 in a sample of boys (N=258) (Wong, Brower, Fitzgerald, & Zucker, 2004). In a mixed-sex sample (N=386), sleep problems predicted onset of cannabis use for boys, but not for girls (Wong, Brower, & Zucker, 2009), suggesting that these effects may be gender-specific.2 However, other studies that simply control for sex have found the sleep problems prospectively predict cannabis use among adolescents in general (LeBourgeois, Giannotti, Cortesi, Wolfson, & Harsh, 2005; Miller et al., 2017). Conversely, higher levels of weekday and total sleep among adolescents have been shown to predict a lower likelihood of cannabis use two years later (N=704) (Pasch, Latimer, Cance, Moe, & Lytle, 2012).

Taken together, prior research supports that sleep difficulties are associated with substance use in general and cannabis use in particular. However, most studies have not examined cannabis use separately, rather have focused on substance use more generally. Thus it is unclear whether insomnia symptoms are uniquely associated with cannabis use. Moreover, rather than examining any level of cannabis use, we focus on using cannabis at thresholds associated with “hazardous” use, possible cannabis use disorder, and negative cannabis-related problems (Adamson et al., 2010), which tend to have more serious consequences. Furthermore, research on mediators and moderators of sleep-cannabis use relationship is still lacking.

Stemming from a harm reduction perspective, protective behavioral strategies (PBS) are behaviors that are used immediately prior to, during, after, and/or instead of substance use that reduce consumption, intoxication, and/or substance-related harm (Pearson, 2013). Specific to cannabis, cannabis PBS (assessed via the Protective Behavioral Strategies for Marijuana Scale [PBSM], Pedersen et al., 2016, 2017) include strategies that are related to limiting cannabis intake by setting consumption limits (e.g., “Having a set amount of times you take a hit of a marijuana joint”), avoiding behaviors that lead to more intoxication than one would like (e.g., “Avoiding mixing marijuana with other drugs”), and avoiding serious harm from impaired driving (e.g., “Using a designated driver after using marijuana”). Increasing evidence suggests that cannabis PBS use is a robust protective factor associated with lower cannabis use and consequences (Bravo, Anthenien, Prince, & Pearson, 2017; Pedersen, Huang, Dvorak, Prince, & Hummer, 2017; Pedersen, Hummer, Rinker, Traylor, & Neighbors, 2016). Cannabis PBS has been shown to mediate the effects of known risk factors on cannabis outcomes including effects of gender, impulsivity-like traits, and specific cannabis use motives (Bravo, Prince, Pearson, & Marijuana Outcomes Study Team, 2017).

Previous research indicate that sleep difficulties and deficits have deleterious effects on inhibitory processes as well as cognitive control (Durmer & Dinges, 2005; Pilcher & Huffcutt, 1996; Wong, Brower, Nigg, & Zucker, 2010). The use of cannabis PBS plausibly requires inhibition of the impulses to consume cannabis as well as the ability to focus on safe use while dealing with distracting information (e.g., withstand friends’ encouragement to use more cannabis than planned). Taken together, sleep difficulties may be associated with problematic cannabis use via a reduction in the use of cannabis PBS.

Purpose of Present Study

The purpose of the present study is to examine the concurrent associations between insomnia symptoms, cannabis PBS, and problematic cannabis use among college students. Specifically, the present study used cross-sectional data to examine the hypotheses that insomnia symptoms lowered one’s tendency to engage in cannabis PBS and lower PBS use was associated with an increase in the likelihood of hazardous cannabis use, possible cannabis use disorder and more cannabis-related problems. Given mixed findings regarding whether the sleep-cannabis associations are consistent across the two sexes, exploratory analyses examined sex as a moderator in our models.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants were college students (n=7,307) recruited to complete an online cross-sectional survey via Psychology Department Participant Pools at ten universities across ten U.S. states (for more information, see (Bravo, Villarosa-Hurlocker, Pearson, & Protective Strategies Study Team, 2018). To minimize burden on participants, we utilized a planned missingness design, or matrix sampling (Graham, Taylor, Olchowski, & Cumsille, 2006; Schafer, 1997). To test our study aims, we limited the analytic sample for the present study to 984 students who reported consuming cannabis at least once in the last 30 days, completed measures of insomnia symptoms and cannabis PBS. Among our analytic sample, the majority of participants identified as being either White, non-Hispanic (n=740; 75.2%) or of Hispanic/Latino ethnicity (n=186; 16.8%), female (n=688; 69.9%), and reported a mean age of 20.21 (Median=19.00; SD=3.14) years. Participants received research participation credit for completing the study. This protocol was approved by institutional review boards at each participating university. Specifically, at the primary author’s institution, the protocol was approved by the Idaho State University Human Subjects Committee (Protocol: IRB-FY2017–206 and Title: Protective Strategies Study Team).

Measures

Insomnia symptoms.

Past 2-week insomnia symptoms were assessed using the 7-item Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) (Bastien, Vallieres, & Morin, 2001) measured on a 5-point response scale (0 = not at all, 4 = extremely). The seven items assess severity of difficulties falling asleep, staying asleep, sleep quality and its impact on daily functioning. We summed items to create a total score of insomnia (M=8.17; SD=5.80; α=.87).

Cannabis PBS.

Past month cannabis PBS use was assessed using the 17-item version (Pedersen et al., 2017) of the Protective Behavioral Strategies-Marijuana Scale (PBSM) (Pedersen et al., 2016). The items were measured on a 6-point response scale (1 = never, 6 = always). Example items include, “Avoid mixing marijuana with other drugs” and “Only use one time during a day/night”. We averaged items to create a total score of cannabis PBS use (M=4.35; SD=1.12; α=91).

Problematic cannabis use.

Problematic cannabis use was assessed using the 8-item Cannabis Use Disorders Identification Test-Revised (CUDIT-R) (Adamson et al., 2010). The CUDIT-R assesses the domains of consumption, cannabis problems (abuse), dependence, and psychological features. Cut-off scores of 8 (CUDIT-R scores ≥ 8) and 12 (CUDIT-R scores ≥13) were used to indicate hazardous cannabis use and possible cannabis use disorder, respectively (Adamson et al., 2010).

Cannabis-related problems.

Cannabis-related consequences were measured by a 21-item Brief Marijuana Consequences Questionnaire (B-MACQ) (Simons, Dvorak, Merrill, & Read, 2012). The B-MACQ measures eight domains of cannabis consequences in the past month (0=no, 1=yes), including interpersonal consequences, negative self-perception, impaired control, risk behaviors, self-care, academic/occupational consequences, physical dependence and blackout use. A composite score of cannabis-related problems was calculated by summing up responses on the items (α=.88). One item assessing difficulty with sleeping after cutting down cannabis use was omitted so that cannabis-related consequences do not overlap with insomnia symptoms measured by the ISI. The test-retest reliability, as well as the convergent and discriminant validity of MACQ has been demonstrated in previous research (Simons et al., 2012).

Analytic Strategy

We used structural equation modeling (SEM) to examine whether insomnia symptoms and cannabis PBS predicted cannabis-related outcomes. Three outcome variables of cannabis use were examined, hazardous cannabis use, possible cannabis use disorder, and cannabis-related consequences. Hazardous cannabis use and possible cannabis use disorder were modeled as binary variables. Model fit was evaluated by the χ2 goodness-of-fit test and three fit indices -Comparative Fit Index (CFI) (Bentler, 1990)), Tucker Lewis Index (TLI) (Tucker & Lewis, 1973), and root mean square of approximation (RMSEA) (Steiger & Lind, 1980). The χ2 statistic evaluates the difference between the data and the fitted covariance matrices, i.e., the hypothetical model (Bentler & Bonett, 1980). An insignificant value indicates a good fit. However, the χ 2 test becomes overly sensitive to small differences between the data and the hypothetical model when sample size increases (Bentler, 1990; West, Taylor, & Wu, 2012). Therefore, other indices are also used to evaluate model fit. A value of 0.9 or above on fit indices such as the CFI and TLI indicates a good fit, whereas a value of 0.95 above indicates an excellent fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Values of 0.06 or below on the root mean square of approximation (RMSEA) indicate a satisfactory fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Cannabis-related consequences were modeled as a count outcome, as the responses were positive integers. We fitted models with a Poisson distribution, a negative binomial distribution, and zero-inflated versions of these models. The Pearson χ 2, a goodness of fit index for count outcomes, was used to evaluate overall model fit (Cameron & Trivedi, 2013; Long, 1997). It measures the discrepancy between the observed counts and the model predicted counts. A nonsignificant χ2 indicates a good fit.

We used bias-corrected bootstrapped estimates (Efron & Tibshirani, 1993) to examine whether cannabis PBS mediated the relationship between insomnia symptoms and cannabis-related outcomes. These estimates are robust to deviations from normality of the indirect effects (Erceg-Hurn & Mirosevich, 2008; Hayes & Scharkow, 2013). A bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence interval based on 10,000 bootstrap samples was created for each cannabis use outcome. We chose 10,000 bootstrap samples as recommended in recent resampling literature to improve Monte Carlo accuracy (Chihara & Hesterberg, 2019). The mediator was significant if the 95% bootstrapped confidence interval does not include zero.

The three outcomes investigated in this paper were either binary or count data. To interpret the estimated coefficients for binary or count outcomes, it is standard practice to exponentiate the coefficient. If an explanatory variable has coefficient β, then eβ is the odds ratio (OR) for a binary outcome (Hosmer, Lemeshow, & Sturdivant, 2013) or the count ratio, also called incidence rate ratio (IRR), for a count outcome (Hilbe, 2011). Therefore, when the explanatory variable is increased by one standard deviation (SD), the odds (for binary outcome) or counts (for count outcome) is expected to change by (eβ*SD – l) × 100%. In particular, if the path from insomnia symptoms to PBS is a and the path from PBS to cannabis use outcome controlling for insomnia symptoms is b, the indirect effect of insomnia on cannabis use outcome in terms of percentage change is (eab*SD – 1) × 100% when insomnia symptoms increase by one SD (MacKinnon, 2008).Given the planned missingness design, missing data were handled by full information maximum likelihood estimates, which used all available data and produces unbiased estimates of coefficient parameters if data are missing completely at random (Enders, 2010; Graham, 2009). All analyses controlled for three demographic variables that have been shown to associate with substance use, i.e., sex (0 = Male, 1 = Female), age, and race (White: 0 = No; 1 = Yes). We also conducted exploratory analyses examining sex as a moderator in our models. SEM models were estimated using Mplus 7.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2018).

Results

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations of major variables are presented in Table 1. Among participants who consumed cannabis in the past 30 days, completed measures of insomnia symptoms and cannabis PBS, 43% reported hazardous cannabis use (score ≥8 on CUDIT-R) and 21% exceeded the cut-off for possible cannabis use disorder (score ≥13 on CUDIT-R). On the average, these participants reported slightly more than 3 (M=3.35, SD=4.00) cannabis-related consequences/problems in the previous month.

Table 1.

Zero-Order Correlations and Descriptive Statistics Among All Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | M | SD | |

| 1. Insomnia | - | 8.17 | 5.80 | |||||||

| 2. Protective Behavioral Strategies | −.07* | - | 4.35 | 1.11 | ||||||

| 3. Hazardous Cannabis Use | .02 | −.36** | - | .43 | .50 | |||||

| 4. Cannabis Use Disorder Symptoms | .07 | −.34** | .66** | - | .21 | .41 | ||||

| 5. Marijuana Consequences Questionnaire | .14** | −.28** | .53** | .57** | - | 3.35 | 4.00 | |||

| 6. Gender (0=men, 1=women) | .09** | .14** | −.17** | −.15** | −.19** | - | .70 | .46 | ||

| 7. Race (0=non-White, 1=White) | .03 | −.06 | .01 | .01 | −.001 | −.08** | - | .75 | .43 | |

| 8. Age | .09** | −.06 | .04 | −.007 | −.02 | −.007 | −.02 | - | 20.21 | 3.14 |

Note.

p < .05,

p < .01, M = Mean, SD = Standard Deviation

Controlling for sex, age and race, insomnia symptoms was associated with an increase in the odds of hazardous cannabis use (OR=1.02, p=.05) and cannabis use disorder symptoms (OR=1.04, p<.01). As insomnia symptoms increased by one standard deviation, the odds of hazardous cannabis use increased by 12% (e.02*5.80 – 1) and the odds of cannabis use disorder symptoms increased by 20% (e 04×5.80 – 1).

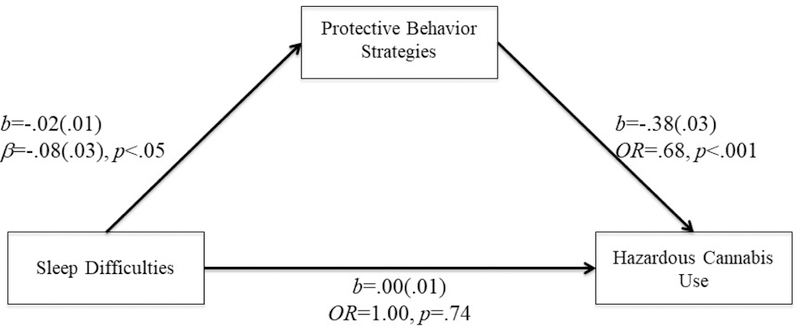

Hazardous Cannabis Use Model

Insomnia symptoms had a negative relationship with cannabis PBS (b=−.02(.01), β=−.08, t=−2.13, p<.05), such that higher insomnia symptoms were associated with lower use of cannabis PBS. Women were more likely to use cannabis PBS then men (b=.36(.08), β=.14, t=4.63, p<.001). Controlling for demographics variables and insomnia symptoms, cannabis PBS was negatively associated with the odds of hazardous cannabis use (b=−.38(.03); OR=.68, p<.001). Cannabis PBS significantly mediated the relationship between insomnia symptoms and hazardous cannabis use (95% bias-corrected bootstrap CI for ab=.001 to .01). Sex did not moderate this indirect relationship (sex effect on insomnia →cannabis PBS (“a” path): b=.01(.01), β=.03, t=.39, p=.70; cannabis PBS →hazardous cannabis use controlling for insomnia (“b” path): b=−.01(.03), β=−.05, t=−.62,p=.54). As insomnia symptoms increased by one SD, the odds of hazardous cannabis use increased by about 5% (e- 02*5−80*−.38) – 1 via cannabis PBS use. The model fit the data well, χ2(2)=5.13,p=.08, CFI=.98, TLI=.93, RMSEA=04

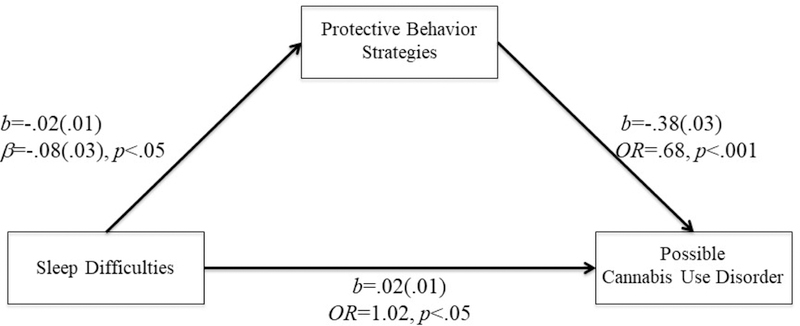

Possible Cannabis Use Disorder Model

Similar to the above findings, controlling for insomnia symptoms and demographic variables, cannabis PBS was negatively associated with the odds of a possible cannabis use disorder (b=−.38(.03), OR=.68, p<.001). Cannabis PBS significantly mediated the relationship between insomnia symptoms and a possible cannabis use disorder (95% bias-corrected bootstrap CI=.001 to .01). Sex did not moderate this relationship (sex effect on insomnia → cannabis PBS (“a” path): b=.01(.01), β=.04, t=.52,p=.61; cannabis PBS → possible cannabis use disorder controlling for insomnia (“b” path): b=.15(.17), β=.16, t=.87,p=.39). As insomnia symptoms increase by one SD, the odds of a possible cannabis use disorder increased by about 5% (e−.02*5.80*−.38 – 1) via cannabis PBS use. The direct effect of insomnia symptoms remained significant. Controlling for cannabis PBS, a one SD increase in insomnia symptoms was associated with 12% (e.02*5.80 – 1) increase in the odds of a possible cannabis use disorder. Overall model fit was good, χ2(2)=4.98, p=08, CFI=98, TLI=92, RMSEA=04.

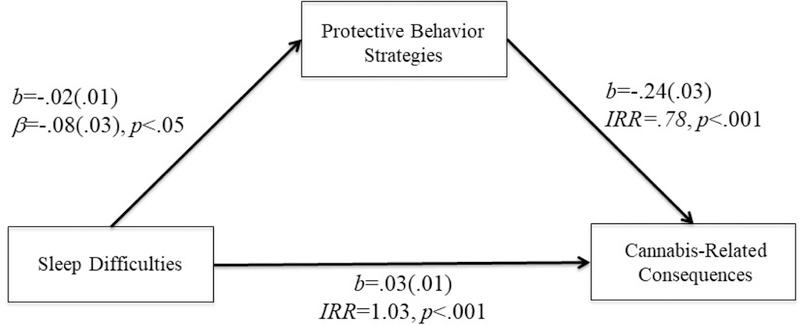

Cannabis-related Consequences Model

We fitted the cannabis-related consequences count outcome using Poisson, negative binomial and zero-inflated versions of these count models. The Poisson count model was rejected, Pearson χ2(978)=3685.38, p=.00. Zero-inflated Poisson model was also rejected, Pearson χ2(972)= 1756.27, p=.00. The negative binomial model fitted the data well, Pearson χ2(977)=861.45, p=.99. The zero-inflated negative binomial model showed similar fit, Pearson χ2(971)=845.63, p=.99. The parameter estimates, their significance, and the indirect effect are very similar in the two models. For ease of presentation, we chose the negative binomial model and reported the results below.

More severe insomnia symptoms were associated with lower cannabis PBS (b=−.02(.01), β=−.08, t=−2.37, p<.05), which significantly predicted cannabis-related consequences (b=−.24(.03), IRR=.78, t=−8.10,p<.001). Lower cannabis PBS significantly mediated the relationship between insomnia symptoms and cannabis-related consequences (95% bias-corrected bootstrap CI=.001 to .01). One SD increase in insomnia symptoms was associated with approximately 3% increase in the cannabis-related consequences via PBS. (e− 02*5.80*−.24 — 1) Sex did not significantly moderate the indirect effect (sex effect on insomnia → cannabis PBS (“a” path): b=.01(.01), β=.04, t=.47, p=.64; cannabis PBS → possible cannabis use disorder controlling for insomnia (“b” path): b=.04(.03), β=.24, t=1.34,p=.18). More severe insomnia symptoms also directly predicted cannabis-related consequences (b=.03(.01), IRR=1.03, t=4.67, p<.001). Controlling for cannabis PBS, a one SD increase of insomnia symptoms predicted approximately 19% (e.03*5.80 – 1) increase in the number of cannabis-related consequences.

Discussion

Previous studies examining the relationship between sleep difficulties and substance use reported an association between insomnia symptoms and cannabis-related outcomes. However, most of these studies focused on the association between sleep difficulties and substance use in general; only a few studies specifically analyzed the relationship between sleep parameters and cannabis use. Moreover, none of these studies examined hazardous cannabis use, possible cannabis use disorder, or a broad-spectrum assessment of cannabis-related problems. This study examined whether insomnia symptoms were associated with problematic cannabis use. Additionally, we tested whether cannabis PBS mediated these relationships. Overall, the results supported our hypotheses that insomnia symptoms were associated with lower use of cannabis PBS, which at least partially accounted for the associations between insomnia symptoms and cannabis-related outcomes.

The present study supports the plausibility that individuals with insomnia symptoms underutilize cannabis PBS, and thus are at higher risk of problematic cannabis use. To our knowledge, this is the first study showing insomnia symptoms had a negative relationship with cannabis PBS. Those who had insomnia symptoms were less likely to use cannabis PBS, which predicted a lower likelihood of hazardous cannabis use. There are at least two reasonable explanations for these findings.

A deficit-based model may suggest that individuals with sleep problems experience cognitive deficits and thus are less effective at planning or following through with plans to use PBS. Indeed, insomnia symptoms (e.g., difficulties falling and staying asleep) and inadequate sleep has been linked to memory deficits (Walker, 2008, 2009), emotional reactivity (Gujar, Yoo, Hu, & Walker, 2011; Walker & van der Helm, 2009), as well as poor executive functioning (Warren, Riggs, & Pentz, 2017; Wong et al., 2010). The use of cannabis PBS (e.g., limit use to weekends, avoid using marijuana to cope with emotions such as sadness or depression) requires planning and thinking in advance before cannabis use. Problems falling or staying asleep likely make it difficult for individuals to have the mental energy and self-control to engage in these strategies.

A motivation-based model may suggest that individuals with sleep problems are less motivated to use PBS, perhaps related to their motivations for using cannabis as a sleep aid (Bonn-Miller, Babson, & Vandrey, 2014; Goodhines, Gellis, Kim, Fucito, & Park, 2017; Walsh et al., 2013). In the alcohol research field, one of the primary reasons that drinkers reported not wanting to use alcohol PBS was their motivation to drink (Bravo, Pearson, Stevens, & Henson, 2018; Pearson, 2013). Related to the present findings, it is plausible that individuals who use cannabis to help with sleep-related problems may see using cannabis PBS as inconsistent with their goals.

Determining the extent to which these distinct explanations account for these associations has important implication for interventions. The deficit-based model would imply that self-regulation-based interventions that make PBS less cognitively demanding or more automatic would be ideal. The motivation-based model would imply that motivation-based interventions that highlight how use of PBS does not necessarily interfere with their goals for cannabis use would be ideal. Clearly, additional studies are needed to replicate and extend these findings to garner support for one or both of these explanations. Finally, we examined whether sex moderated the associations between insomnia symptoms and cannabis-related outcomes. The mediated effects of insomnia symptoms on hazardous cannabis use, possible cannabis use disorder, and cannabis-related problems were consistent across men and women, suggesting that the mediated effects of cannabis PBS are not gender-specific. A previous study found that the protective effect of cannabis PBS on cannabis use was slightly stronger among males than females, but found no gender differences in the association between cannabis PBS and cannabis- related consequences (Bravo, Anthenien, et al., 2017). Given that the Bravo et al. study used a different measure of cannabis use (Marijuana Use Grid) (Pearson & Marijuana Outcomes Study Team, 2018), further research is needed to clarify the associations between cannabis PBS use and cannabis outcomes across genders.

Limitations and Future Research

The present study had a number of important limitations that must be considered when interpreting our findings. The cross-sectional study design does not allow us to establish temporal precedence among variables. While our focus on the role of insomnia symptoms in problematic cannabis use is based on previous studies (Hasler et al., 2017; Wong et al., 2015), the relationship between insomnia and cannabis use is likely bidirectional and we are unable to determine whether insomnia symptoms lead to a higher likelihood of problematic cannabis use, or if problematic cannabis use leads to greater insomnia symptoms using data from a single time point. The effects of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) in cannabis vary across individuals, depending on factors such as the amount consumed, chronicity (whether someone is a naive, occasional or chronic user), methods of consumption (smoked in a joint or ingested as an edible), specific cannabinoid profile (the presence of cannabidiol (CBD) and other cannabinoids modulate the effects of THC), and interactions with other substance use (Iversen, 2007). Using cannabis as a sleep aid has been reported among college students (Goodhines et al., 2017), patients with post-traumatic disorder symptoms (Bonn-Miller et al., 2014), and patients with different medical conditions and symptoms (Walsh et al., 2013). However, cannabis may also increase onset latency, increase slow wave sleep and decrease REM sleep in others (Schierenbeck, Riemann, Berger, & Hornyak, 2008). Sleep disturbances are especially common during periods of withdrawal (Gates, Albertella, & Copeland, 2016). It is also possible that lower marijuana PBS caused increase in cannabis use and insomnia symptoms. Taken together, we cannot rule out alternative explanations such as problematic cannabis use leading to sleep difficulties or lower marijuana PBS causing increases in both cannabis use and insomnia symptoms. Future studies, especially those with longitudinal data, could investigate the temporal and the bidirectional relationships among sleep parameters, cannabis PBS and cannabis use.

In this study, we examined one possible mediator of the sleep-cannabis association. However, we realize that there are probably additional mediators that account for insomnia symptoms leading to cannabis use, and likely different mediators that account for cannabis use leading to insomnia symptoms. Longitudinal studies that explore these bidirectional pathways are needed. Although we obtained a large sample of college students, our convenience sampling methods did not ensure that our sample is representative of the college student population, thus there are concerns for generalizing our findings to the college student population as a whole. These concerns are mitigated by the fact that our sample appears rather similar to other national studies of college students in terms of cannabis use prevalence (Bravo, Prince, et al., 2017). For instance, the rate of possible CUD is this study (21%) is similar to the rate reported among college students who used cannabis in a previous study (24.6%) (Caldeira, Arria, O’Grady, Vincent, & Wish, 2008).

Conclusions

In conclusion, the present study identified cannabis PBS use as a possible mediator of the relationship between insomnia symptoms and hazardous cannabis use in a sample of college students. Intervention programs that emphasize on the importance of sleep hygiene, adequate sleep, as well as the relationship between insomnia and PBS may be beneficial to college students who use cannabis. The findings of this paper need to be replicated and extended in future studies. Longitudinal studies that reveal the reciprocal relations between sleep problems and cannabis use will be particularly useful.

Figure 1.

PBS mediated the relationship between sleep difficulties and hazardous cannabis use.

Model fit: χ2(2)=5.13, p=0.08., CFI=0.98, TLI=0.93, RMSEA=0.04; OR=Odds ratio

Figure 2.

PBS mediated the relationship between sleep difficulties and possible cannabis user disorder.

Model fit: χ2(2)=4.98, p=0.08., CFI=0.98, TLI=0.92, RMSEA=0.04; OR=Odds ratio

Figure 3.

PBS mediated the relationship between sleep difficulties and cannabis-related consequences.

Model fit: Pearson χ2(977)=861.45, p=.99; IRR=incidence rate ratio

Public Health Significance.

This study showed that insomnia symptoms were associated with an increase in the odds of hazardous cannabis use among college students from ten different U.S. campuses Use of cannabis protective behavioral strategies partially explained this relationship. Prevention and intervention programs could educate college students about the benefits of regular and sufficient sleep as well as its relationship with cannabis protective behavioral strategies and cannabis use.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Wong is supported by a research grant from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (R01 AA020365). Dr. Bravo is supported by a training grant (T32 AA018108) from the NIAAA. Dr. Pearson is supported by a career development grant (K01 AA023233) from the NIAAA.

Footnotes

Disclosures

All authors have contributed to the present manuscript in a significant way and have both read and approved the final manuscript.

Sleep problems or difficulties refer to problems such as insomnia or insomnia symptoms, nightmares and overtiredness. As we did not include any studies on sleep apnea, the terms did not include sleep apnea.

We used the term “gender” to refer to the social categories of female and male, e.g., certain behaviors may be influenced by social and cultural factors (Tobach, 2004; Unger, 2007). We used the term “sex” to refer to the biological status of being female or male.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Adamson SJ, Kay-Lambkin FJ, Baker AL, Lewin TJ, Thornton L., Kelly BJ, & Sellman JD (2010). An improved brief measure of cannabis misuse: The Cannabis Use Disorders Identification Test-Revised (CUDIT-R). Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 770(1–2), 137–143. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.02.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aviram J., & Samuelly-Leichtag G. (2017). Efficacy of Cannabis-Based Medicines for Pain Management: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Pain Physician, 20(6), E755-e796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastien CH, Vallieres A., & Morin CM (2001). Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Medicine, 2(4), 297–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 707(2), 238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM, & Bonett DG (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88(3), 588–606. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.88.3.588 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bonn-Miller MO, Babson KA, & Vandrey R. (2014). Using cannabis to help you sleep: Heightened frequency of medical cannabis use among those with PTSD. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 736, 162–165. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.12.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo AJ, Anthenien AM, Prince MA, & Pearson MR (2017). Marijuana protective behavioral strategies as a moderator of the effects of risk/protective factors on marijuana-related outcomes. Addictive Behaviors, 69, 14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo AJ, Pearson MR, Stevens LE, & Henson JM (2018). Weighing the Pros and Cons of Using Alcohol Protective Behavioral Strategies: A Qualitative Examination among College Students. Substance Use and Misuse, 53(13), 2190–2198. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2018.1464026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo AJ, Prince MA, Pearson MR, & Marijuana Outcomes Study Team. (2017). Can I use marijuana safely? An examination of distal antecedents, marijuana protective behavioral strategies, and marijuana outcomes. J Stud Alcohol Drugs, 78(2), 203–212. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2017.78.203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo AJ, Villarosa-Hurlocker MC, Pearson MR, & Protective Strategies Study Team. (2018). College student mental health: An evaluation of the DSM-5 self-rated level 1 cross-cutting symptom measure. Psychological Assessment. doi: 10.1037/pas0000628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldeira KM, Arria AM, O’Grady KE, Vincent KB, & Wish ED (2008). The occurrence of cannabis use disorders and other cannabis-related problems among first- year college students. Addictive Behaviors, 33(3), 397–411. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron AC, & Trivedi PK (2013). Regression analysis of count data. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chihara LM, & Hesterberg TC (2019). Mathematical Statistics with Resampling andR (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Durmer JS, & Dinges DF (2005). Neurocognitive consequences of sleep deprivation. Seminars in Neurology, 25(1), 117–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efron B., & Tibshirani RJ (1993). An introduction to the bootstrap. New York: Chapman & Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK (2010). Applied missing data analysis. New York, NY US: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Erceg-Hurn DM, & Mirosevich VM (2008). Modern robust statistical methods: An easy way to maximize the accuracy and power of your research. American Psychologist, 63(7), 591–601. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.63.7.591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fakier N., & Wild LG (2011). Associations among sleep problems, learning difficulties and substance use in adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 34(4), 717–726. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates P., Albertella L., & Copeland J. (2016). Cannabis withdrawal and sleep: A systematic review of human studies. Substance Abuse, 37(1), 255–269. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2015.1023484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodhines PA, Gellis LA, Kim J., Fucito LM, & Park A. (2017). Self-Medication for Sleep in College Students: Concurrent and Prospective Associations With Sleep and Alcohol Behavior. Behavioral Sleep Medicine, 1–15. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2017.1357119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW (2009). Missing data analysis: Making it work in the real world. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 549–576. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW, Taylor BJ, Olchowski AE, & Cumsille PE (2006). Planned missing data designs in psychological research. Psychological Methods, 11(4), 323–343. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.11.4.323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gujar N., Yoo S-S, Hu P., & Walker MP (2011). Sleep deprivation amplifies reactivity of brain reward networks, biasing the appraisal of positive emotional experiences. The Journal of Neuroscience, 31(12), 4466–4474. doi: 10.1523/JNEUR0SCI.3220-10.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall W. (2015). What has research over the past two decades revealed about the adverse health effects of recreational cannabis use? Addiction, 110(1), 19–35. doi: 10.1111/add.12703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasler BP, Franzen PL, de Zambotti M., Prouty D., Brown SA, Tapert SF, … Clark DB (2017). Eveningness and Later Sleep Timing Are Associated with Greater Risk for Alcohol and Marijuana Use in Adolescence: Initial Findings from the National Consortium on Alcohol and Neurodevelopment in Adolescence Study. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 41(6), 1154–1165. doi: 10.1111/acer.13401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF, & Scharkow M. (2013). The relative trustworthiness of inferential tests of the indirect effect in statistical mediation analysis: Does method really matter? Psychological Science, 24(10), 1918–1927. doi: 10.1177/0956797613480187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilbe JM (2011). Negative Binomial Regression (2nd ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S., & Sturdivant RX (2013). Applied Logistic Regression (3rd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L.-t., & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iversen L. (2007). The Science of Marijuana. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson EO, & Breslau N. (2001). Sleep problems and substance use in adolescence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 64(1), 1–7. doi: 10.1016/S0376-8716(00)00222-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBourgeois MK, Giannotti F., Cortesi F., Wolfson AR, & Harsh J. (2005). The relationship between reported sleep quality and sleep hygiene in Italian and American adolescents. Pediatrics, 115(1), 257–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long JS (1997). Regression models for categorical and limited dependent variables. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP (2008). Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis Group/Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- McKnight-Eily LR, Eaton DK, Lowry R., Croft JB, Presley-Cantrell L., & Perry GS (2011). Relationships between hours of sleep and health-risk behaviors in US adolescent students. Preventive Medicine, 53(4–5), 271–273. doi:http://dx.doi.ors/10.1016/i.ypmed.2011.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MB, Janssen T., & Jackson KM (2017). The prospective association between sleep and initiation of substance use in young adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 60(2), 154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.08.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998-2018). Mplus User’s Guide (Seventh ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Nugent SM, Morasco BJ, O’Neil ME, Freeman M., Low A., Kondo K., … Kansagara D. (2017). The Effects of Cannabis Among Adults With Chronic Pain and an Overview of General Harms: A Systematic Review. Annals of Internal Medicine, 167(5), 319–331. doi: 10.7326/m17-0155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasch KE, Latimer LA, Cance JD, Moe SG, & Lytle LA (2012). Longitudinal bidirectional relationships between sleep and youth substance use. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41(9), 1184–1196. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9784-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson MR (2013). Use of alcohol protective behavioral strategies among college students: A critical review. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(8), 1025–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson MR, & Marijuana Outcomes Study Team. (2018). Marijuana Use Grid: A brief, comprehensive measure of marijuana use. Manuscript submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen ER, Huang W., Dvorak RD, Prince MA, & Hummer JF (2017). The Protective Behavioral Strategies for Marijuana Scale: Further examination using item response theory. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 31(5), 548–559. doi: 10.1037/adb0000271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen ER, Hummer JF, Rinker DV, Traylor ZK, & Neighbors C. (2016). Measuring protective behavioral strategies for marijuana use among young adults. J Stud Alcohol Drugs, 77(3), 441–450. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2016.77.441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilcher JJ, & Huffcutt AI (1996). Effects of sleep deprivation on performance: A meta-analysis. Sleep, 19(4), 318–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL (1997). Analysis of incomplete multivariate data. New York: Chapman and Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Schierenbeck T., Riemann D., Berger M., & Hornyak M. (2008). Effect of illicit recreational drugs upon sleep: cocaine, ecstasy and marijuana. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 12(5), 381–389. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2007.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg JE, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Miech RA, & Patrick ME (2018). Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2017: Volume II, College students and adults ages 19–55. Retrieved from http://monitoringthefuture.org/pubs.html#monographs

- Sharkey KA, Darmani NA, & Parker LA (2014). Regulation of nausea and vomiting by cannabinoids and the endocannabinoid system. European Journal of Pharmacology, 722, 134–146. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.09.068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Dvorak RD, Merrill JE, & Read JP (2012). Dimensions and severity of marijuana consequences: Development and validation of the Marijuana Consequences Questionnaire (MACQ). Addictive Behaviors, 37(5), 613–621. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.01.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivertsen B., Skogen JC, Jakobsen R., & Hysing M. (2015). Sleep and use of alcohol and drug in adolescence A large population-based study of Norwegian adolescents aged 16 to 19 years. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 149, 180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.01.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiger JH, & Lind JC (1980). Statistically based tests for the number of common factors. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Psychometric Society, Iowa City, IA. [Google Scholar]

- Tobach E. (2004). Development of sex and gender: Biochemistry, physiology, and experience In Paludi MA (Ed.), Praeger guide to the psychology of gender. (pp. 240–270). Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers/Greenwood Publishing Group. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker LR, & Lewis C. (1973). A reliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika, 35(1), 1–10. doi: 10.1007/BF02291170 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turgeman I., & Bar-Sela G. (2018). Cannabis for cancer - illusion or the tip of an iceberg: a review of the evidence for the use of Cannabis and synthetic cannabinoids in oncology. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. doi: 10.1080/13543784.2019.1561859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger RK (2007). Afterword: From inside and out: Reflecting on a feminist politics of gender in psychology. Feminism & Psychology, 17(4), 487–494. doi: 10.1177/0959353507083099 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walker MP (2008). Cognitive consequences of sleep and sleep loss. Sleep Medicine, 9(Suppl1), S29–S34. doi:10.1016/S1389-10.1016/S1389-9457(08)70014-59457(08)70014-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker MP (2009). The role of sleep in cognition and emotion. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 168–197. doi: 10.1111/i.l749-6632.2009.Q4416.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker MP, & van der Helm E. (2009). Overnight therapy? The role of sleep in emotional brain processing. Psychological Bulletin, 135(5), 731–748. doi: 10.1037/a0016570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh Z., Callaway R., Belle-Isle L., Capler R., Kay R., Lucas P., & Holtzman S. (2013). Cannabis for therapeutic purposes: Patient characteristics, access, and reasons for use. International Journal of Drug Policy, 24(6), 511–516. doi:https://doi.ors/10.1016/i.drugpo.2013.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren CM, Riggs NR, & Pentz MA (2017). Longitudinal relationships of sleep and inhibitory control deficits to early adolescent cigarette and alcohol use. Journal of Adolescence, 57, 31–41. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West SG, Taylor AB, & Wu W. (2012). Model fit and model selection in structural equation modeling In Hoyle RH & Hoyle RH (Eds.), Handbook of structural equation modeling. (pp. 209–231). New York, NY, US: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wong MM, Brower KJ, Fitzgerald HE, & Zucker RA (2004). Sleep problems in early childhood and early onset of alcohol and other drug use in adolescence. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 28(4), 578–587. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000121651.75952.39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong MM, Brower KJ, Nigg JT, & Zucker RA (2010). Childhood sleep problems, response inhibition, and alcohol and drug outcomes in adolescence and young adulthood. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 34(6), 1033–1044. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01178.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong MM, Brower KJ, & Zucker RA (2009). Childhood sleep problems, early onset of substance use and behavioral problems in adolescence. Sleep Medicine, 10(7), 787–796. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2008.06.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong MM, Robertson GC, & Dyson RB (2015). Prospective relationship between poor sleep and substance-related problems in a national sample of adolescents. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 39(2), 355–362. doi: 10.1111/acer.12618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2018). Cannabis. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/substanceabuse/facts/cannabis/en/