Abstract

BACKGROUND

Metagenomic next-generation sequencing (NGS) of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) has the potential to identify a broad range of pathogens in a single test.

METHODS

In a 1-year, multicenter, prospective study, we investigated the usefulness of metagenomic NGS of CSF for the diagnosis of infectious meningitis and encephalitis in hospitalized patients. All positive tests for pathogens on metagenomic NGS were confirmed by orthogonal laboratory testing. Physician feedback was elicited by teleconferences with a clinical microbial sequencing board and by surveys. Clinical effect was evaluated by retrospective chart review.

RESULTS

We enrolled 204 pediatric and adult patients at eight hospitals. Patients were severely ill: 48.5% had been admitted to the intensive care unit, and the 30-day mortality among all study patients was 11.3%. A total of 58 infections of the nervous system were diagnosed in 57 patients (27.9%). Among these 58 infections, metagenomic NGS identified 13 (22%) that were not identified by clinical testing at the source hospital. Among the remaining 45 infections (78%), metagenomic NGS made concurrent diagnoses in 19. Of the 26 infections not identified by metagenomic NGS, 11 were diagnosed by serologic testing only, 7 were diagnosed from tissue samples other than CSF, and 8 were negative on metagenomic NGS owing to low titers of pathogens in CSF. A total of 8 of 13 diagnoses made solely by metagenomic NGS had a likely clinical effect, with 7 of 13 guiding treatment.

CONCLUSIONS

Routine microbiologic testing is often insufficient to detect all neuroinvasive pathogens. In this study, metagenomic NGS of CSF obtained from patients with meningitis or encephalitis improved diagnosis of neurologic infections and provided actionable information in some cases. (Funded by the National Institutes of Health and others; PDAID ClinicalTrials.gov number, .)

The existing paradigm for diagnosing infections relies on the physician formulating a differential diagnosis on the basis of a patient’s history, clinical presentation, and imaging findings, followed by serial laboratory testing. This traditional approach is particularly challenging for neuroinflammatory diseases given overlapping clinical manifestations of infectious and noninfectious causes, a lack of diagnostic tests for rare pathogens, and the limited availability and volume of central nervous system (CNS) samples owing to the requirement for invasive procedures, such as lumbar puncture or brain biopsy. Thus, a cause for acute meningoencephalitis cases is not identified in approximately 50% of patients.1–3 Failure to obtain a timely diagnosis in patients with CNS disease contributes to poor patient outcomes, increased patient and family anxiety, and a high cost burden to the health care system.4

Metagenomic next-generation sequencing (NGS) is a promising approach for the diagnosis of infectious disease because a comprehensive spectrum of potential causes — viral, bacterial, fungal, and parasitic — can be identified by a single assay.5,6 However, published reports describing the usefulness of metagenomic NGS in patients with meningitis or encephalitis are limited to individual patients or small, retrospective case series.7 The question remains whether the diagnostic performance and yield of clinical metagenomic NGS testing for neurologic infections justifies its wider adoption by the medical community.

We performed a 1-year, prospective, multicenter study involving hospitalized patients presenting with idiopathic meningitis, encephalitis, or myelitis (the Precision Diagnosis of Acute Infectious Diseases [PDAID] study). We recently described the analytic sensitivity and specificity of the metagenomic NGS assay of CSF for identification of pathogens in patients with neurologic infection confirmed by routine diagnostic testing, including culture and polymerase-chainreaction (PCR) assay.8,9 This study was designed to evaluate the real-life clinical performance and effect of the metagenomic NGS assay in comparison with conventional microbiologic testing in patient-care scenarios in which the test is likely to be used. As such, results of metagenomic NGS were reported in the electronic medical record (EMR) and used for contemporaneous patient-care decisions by treating physicians.

Methods

Study Design

This study was a 1-year, multicenter, prospective case series in which patients were enrolled on the basis of a particular exposure (i.e., idiopathic meningitis with or without encephalitis, myelitis, or both) and then followed over time to assess for the occurrence of the outcome (i.e., results of metagenomic NGS of CSF). Prospective enrollees were identified by means of physician referral, computerized provider-order entry, patient chart review, or screening of daily EMR reports (see the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org). Given the constraints on funding and clinicaltesting capacity, sample-size estimates (300 patients) were based on convenience without formal statistical considerations. The target condition was idiopathic meningitis, encephalitis, or myelitis in patients who had not received a diagnosis at the time of enrollment (Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix). The index test was a metagenomic NGS assay of CSF, and the reference standard was a composite of conventional testing and orthogonal confirmatory testing of positive tests for pathogens on metagenomic NGS only.

Because standard reference results for diagnosis of meningitis and encephalitis were not available (owing to the varying extent of diagnostic testing done at each hospital, a lack of detailed performance characteristics for each test performed locally, and a lack of comprehensive reference testing for meningitis and encephalitis), obtaining unbiased estimates of sensitivity and specificity was not possible. Thus, the comparative performance measures of metagenomic NGS relative to conventional testing are reported as positive percent agreement and negative percent agreement with the composite reference standard (see the Supplementary Appendix, including Fig. S1), in accordance with statistical guidance from the Food and Drug Administration.10

Metagenomic NGS of CSF

CSF samples were batched for weekly processing in the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments–certified clinical microbiology laboratory at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), with the use of a protocol for the validated metagenomic NGS assay, as described previously.8,9 RNA and DNA libraries that were generated from CSF samples obtained from patients were each sequenced to a depth of 5 million to 10 million single-end, 140-base-pair reads on an Illumina HiSeq instrument in rapidrun mode. Automated computational analysis of metagenomic NGS data was performed with the use of a modified clinical version of the Sequence-based Ultra-Rapid Pathogen Identification (SURPI) pipeline11; the modified SURPI+ pipeline incorporated taxonomic classification for species-specific identification and a graphical user interface (see the Supplementary Appendix). Detection of pathogens according to type was reported on the basis of preestablished threshold criteria.8,9

After review by the laboratory director, results were immediately reported in the patient EMR, with follow-up by discussion with the treating physicians through real-time teleconferencing at a meeting of the clinical microbial sequencing board (see the Supplementary Appendix). Physician feedback was elicited during these meetings regarding the effect of metagenomic NGS results on clinical reasoning, management of patient care, or both. Standardized physician surveys that were conducted before and after reporting of metagenomic NGS results were also used to elicit feedback (see the study protocol, available at NEJM.org).

Chart Review

The study enrollment target was 300 patients over the 1-year study period. All patients who were enrolled in the study provided written informed consent. Final clinical diagnoses for the patients who completed the study were adjudicated by retrospective, in-depth chart review independently performed by a board-certified neurologist (the first author) and infectious-diseases physician and microbiologist (the last author).

Orthogonal confirmation of discrepant results was performed with the use of a validated clinical assay (preferred) or PCR testing in a research laboratory. The result of the orthogonal confirmatory test was considered to be accurate and used to resolve the discrepancy. Confirmation was done to minimize incorporation bias by the inclusion of unverified results of the index text (i.e., metagenomic NGS) into the definition of an infectious diagnosis.12 Incidental findings and laboratory-reported contaminants were also recorded. Any discrepancies in assignment of diagnoses were resolved by direct communication with treating physicians or by mutual consensus.

Results

Patient Characteristics

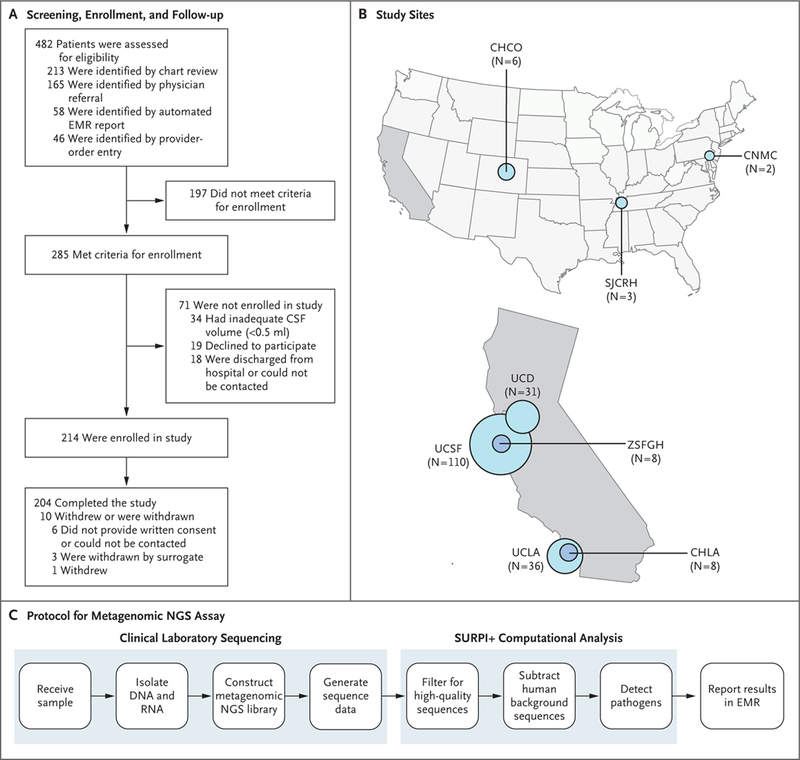

Between June 1, 2016, and July 1, 2017, a total of 482 patients were screened and referred across eight participating sites for review and prospective enrollment in this study (Fig. 1A). A total of 285 patients met the enrollment criteria (Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix), 214 were enrolled, and 204 completed the study. The average age of the 204 patients (55.9% were male) was 39.6 years; 46 patients (22.5%) were 18 years of age or younger (Table 1). The cohort primarily included patients with isolated meningitis (70 patients [34.3%]) or encephalitis (130 patients [63.7%]), with only 2.0% presenting with myelitis (4 patients). A total of 86.3% of the patients (176 patients) presented with an acute condition, whereas the remaining 13.7% (28 patients) presented with an acute exacerbation of a chronic condition. Most of the patients (193 patients [94.6%]) were enrolled from California hospitals (Fig. 1B), and 40.7% (83 patients) were immune-compromised (Table 1). Study patients had a mean length of stay of 27.9 days (median, 17; range, 1 to 246) and were severely ill: 48.5% (99 patients) were admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU). Critically ill patients who were enrolled at the University of California, Los Angeles, and UCSF (69 of the 146 patients [47.3%] who were enrolled at these two sites) spent an average of 17.8 days in the ICU. The overall 30-day mortality (both in the hospital and out of the hospital) was 11.3% (23 patients).

Figure 1. Overview of the Study.

Panel A shows the flow of patients through the study. Panel B shows 8 participating sites. The size of the circle is proportional to the number of patients enrolled at a given site. Panel C shows the protocol for the metagenomic next-generation sequencing (NGS) assay. After samples of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) are received in the clinical laboratory, nucleic acid (DNA and RNA) is isolated, followed by construction of a metagenomic NGS library and sequencing. The metagenomic NGS data are analyzed with the use of an automated computational pipeline (Sequence-based Ultra-Rapid Pathogen Identification [SURPI+]), with results reported in the electronic medical record (EMR) after review by the laboratory director. CHCO denotes Children’s Hospital Colorado; CHLA Children’s Hospital Los Angeles; CNMC Children’s National Medical Center; SJCRH St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital; UCD University of California, Davis; UCLA University of California, Los Angeles; UCSF University of California, San Francisco; and ZSFGH Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the 204 Patients.*

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Mean — yr | 39.6 |

| Distribution — no. (%) | |

| 0–2 yr | 5 (2.5) |

| 3–12 yr | 25 (12.3) |

| 13–18 yr | 16 (7.8) |

| 19–25 yr | 17 (8.3) |

| 26–40 yr | 40 (19.6) |

| 41–60 yr | 53 (26.0) |

| >60yr | 48 (23.5) |

| Male sex — no. (%) | 114 (55.9) |

| Syndrome — no. (%) | |

| Meningitis alone | 70 (34.3) |

| Encephalitis with or without meningitis | 130(63.7) |

| Myelitis with or without meningitis | 4 (2.0) |

| Exacerbation of chronic condition — no. (%)† | 28(13.7) |

| Institution — no. (%) | |

| University of California, San Francisco | 110(53.9) |

| University of California, Los Angeles | 36 (17.6) |

| University of California, Davis | 31 (15.2) |

| Children’s Hospital Los Angeles | 8 (3.9) |

| ZuckerbergSan Francisco General Hospital | 8 (3.9) |

| Children’s Hospital Colorado | 6 (2.9) |

| St.Jude Children’s Research Hospital | 3 (1.5) |

| Children’s National Medical Center | 2 (1.0) |

| Immunocompromised — no. (%) | 83 (40.7) |

| HIV–1 | 21 (10.3) |

| Solid–organ transplant | 14 (6.9) |

| Bone marrow transplant | 13 (6.4) |

| Chemotherapy | 14 (6.9) |

| Immunosuppression for non–neoplastic condition | 14 (6.9) |

| Congenital condition | 3 (1.5) |

| Other | 4 (2.0) |

| Existing CNS hardware — no. (%)‡ | 27 (13.2) |

| ICU admission — no. (%) | 99 (48.5) |

| Death within 30 days — no. (%) | 23 (11.3) |

| Mean Karnofsky performance–status score at time of discharge§ | 64.6 |

| Mean length of stay (range) — days | |

| In hospital | 27.9 (1–246) |

| In ICU¶ | 17.8 (1–71) |

| Percentage of hospitalization time spent in ICU¶ | 32.2 |

| Median no. of days after hospital admission that CSF was collected for metagenomic NGS (range) — days‖ | 3.0 (0–219) |

| Mean total cost (range) — U.S. $** | |

| All cases | 211,706 (73,819–158,795) |

| Infectious cases†† | 234,318 (42,368–110,840) |

CNS denotes central nervous system, CSF cerebrospinal fluid, HIV-1 human immunodeficiency virus 1, ICU intensive care unit, IQR interquartile range, and NGS next-generation sequencing. Percentages may not total 100 because of rounding.

Symptoms had been present for more than 4 weeks.

Included are patients with a shunt, pain pump, lumbar drain, or other neurosurgical hardware.

Karnofsky performance-status scores range from 0 to 100, with lower scores indicating greater disability. A score of 60 to 70 indicates that the patient requires occasional assistance but is able to care for most needs. Data were available for 191 patients.

Data are for patients enrolled at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), and University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) who were admitted to the ICU (69 patients).

Data do not include patients for whom an earlier CSF sample obtained at an outside hospital was used (13 patients from whom CSF was obtained a median of 3 days before transfer to a study site).

Data are for total (hospital and professional billing) costs paid for UCSF patients only (110 patients).

Data are for UCSF patients with an infectious diagnosis only (30 patients).

CSF Analysis by Metagenomic NGS Testing

CSF samples from all 204 patients were analyzed by means of metagenomic NGS and the automated SURPI+ computational pipeline, as described previously (Fig. 1C).11 The mean laboratory turnaround time from initiation of CSF sample processing by nucleic acid extraction to completion of SURPI+ analysis was 90 hours.

Performance of Metagenomic NGS Relative to Conventional Testing

An etiologic diagnosis was identified in 50.5% of the study patients (Fig. 2A), with infectious (27.9%) and autoimmune (8.3%) as the most common diagnostic categories. A composite reference standard that combined results from orthogonally confirmed metagenomic NGS with conventional testing was used to evaluate the comparative performance of metagenomic NGS (see the Supplementary Appendix). Of 58 infections in 57 patients, 19 (33%) were diagnosed by both conventional testing and metagenomic NGS, 26 (45%) by conventional testing only, and 13 (22%) by metagenomic NGS only (Table 2; also see the Case Vignettes in the Supplementary Appendix).

Figure 2 (facing page). Results of Metagenomic NGS Testing and Clinical Effect.

Panel A shows the proportion and categories of established diagnoses in the study patients. A diagnosis was made in 103 of 204 patients (50.5%) after routine clinical workup and metagenomic NGS testing of CSF. A total of 58 infections (pink circles) were identified in 57 patients (27.9%). Conventional testing included culture, polymerase-chain-reaction (PCR), serologic (antibody), and antigen testing of CSF and other body fluids or tissues. Diagnoses in the “Other” category included resolving treated infection, idiopathic intracranial hypertension, posterior reverse encephalopathy syndrome, postneurosurgical (chemical) meningitis, and hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. In Panel B, a plot shows the number and percentage of patients with high DNA or RNA background at designated intervals of CSF cell counts. The proportion of samples with high background (defined as samples in which the normalized read counts corresponding to the internal spiked DNA or RNA control did not meet preestablished thresholds) increases with increasing cell count. Panel C shows supplementary metagenomic NGS analyses discussed during meetings of the clinical microbial sequencing board (CMSB). Panel D shows clinician feedback for cases diagnosed solely by metagenomic NGS. Panel E shows the clinical effect of cases diagnosed solely by metagenomic NGS. The specific effect of metagenomic NGS results on the initiation, discontinuation, or length of antibiotic or antiviral treatment is described. EBV denotes Epstein–Barr virus, HEV hepatitis E virus, HIV-1 human immunodeficiency virus type 1, IV intravenous, and SLEV St. Louis encephalitis virus.

Table 2.

Infections Diagnosed by Means of Metagenomic NGS.*

| Microorganism | High Host Background | Relevant Clinical Microbiologic Testing | Orthogonal Confirmatory Testing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Concurrent diagnosis by metagenomic NGS and conventional microbiologic testing (19 infections) | |||

| Angiostrongylus cantonensis | No | CSF PCR assay for A. cantonensis (+) (CDC) | |

| A. cantonensis | No | CSF PCR assay for A. cantonensis (+) (CDC) | |

| Coxsackievirus B5† | No | CSF RT-PCR assay for EV (+), 800 copies/ml | |

| Cryptococcus neoformans | Yes | CSF culture for C. neoformans (+); CSF cryptococcal antigen assay (+), 1:640 | |

| C. neoformans | No | CSF culture for C. neoformans (+); FilmArray Meningitis/Encephalitis panel, C. neoformans (+) | |

| C. neoformans | No | CSF culture for C. neoformans (+) | |

| EBV (encephalitis)‡ | No | CSF PCR assay for EBV (+), 2000 copies/ml | |

| EBV (PTLD-associated) | No | CSF qPCR assay for EBV (+), <50 lU/ml (Viracor) | |

| Echovirus 11† | No | FilmArray Meningitis/Encephalitis panel, EV (+) (BioFire) | |

| HHV-6§ | No | FilmArray Meningitis/Encephalitis panel, HHV-6(+) (BioFire) | |

| HHV-6§ | No | CSF PCR assay for HHV-6 (+), 536,000 copies/ml (Viracor) | |

| HIV-1 (encephalopathy) | No | CSF PCR assay for HIV-1 (+), 6900 copies/ml (ARUP Laboratories) | |

| HIV-1 (HIV escape) | No | CSF PCR assay for HIV-1 (+), 36,000 copies/ml (ARUP Laboratories) | |

| HSV-1 | No | CSF PCR assay for HSV-1 (+) by Simplexa (UCSF) | |

| HSV-2 | No | CSF PCR assay for HSV-2 (+), 166,000 copies/ml (Viracor) | |

| JC polyomavirus | No | CSF PCR assay for JC polyomavirus (+), 162,000 copies/ml (Viracor) | |

| VZV | No | FilmArray Meningitis/Encephalitis panel, VZV (+) (BioFire) | |

| VZV | No | FilmArray Meningitis/Encephalitis panel, VZV (+) (BioFire) | |

| VZV | Yes | CSF PCR assay for VZV (+), 371,000 copies/ml (Viracor) | |

| Diagnosis by metagenomic NGS only (13 infections) | |||

| Candida tropicalis¶ | No | Serum and CSF l,3-β-D-glucan (+); CSF culture (−) | CSF fungal 28S rRNA and ITS PCR assay, C. tropicalis (+) (UW) |

| EBV (lymphoma-associated)‖ | No | — | CSF qPCR assay for EBV (+), 700 lU/ml (Viracor) |

| Echovirus 6† | No | — | CSF RT-PCR assay for EV (+), confirmed by Sanger sequencing (UCSF) |

| Echovirus 30† | No | — | CSF RT-PCR assay for EV (+), confirmed by Sanger sequencing (UCSF) |

| Enterobacter aerogenes** | Yes | CSF bacterial culture (−); CSF bacterial 16S rRNA PCR assay (−) (UW) | CSF PCR assay for E. aerogenes (renamed Klebsielta aerogenes) (+), confirmed by Sanger sequencing (UCSF) |

| Enterococcus faecaiis†† | No | CSF bacterial culture (−); FilmArray Meningitis/Encephalitis panel (−) | CSF bacterial 16S rRNA PCR assay (−) (UW); brain biopsy, E.faecalis by culture (+) (SJCRH) |

| HEV | No | — | CSF IgM assay for HEV (+); CSF IgG assay for HEV (−); CSF RT-PCR assay for HEV (+),5.96 million copies/ml (ARUP Laboratories) |

| MW polyomavirus | No | — | CSF PCR assay for MW polyomavirus (+), confirmed by Sanger sequencing (UCSF) |

| Neisseria meningitidis‡‡ | Yes | CSF Gram’s stain, gram-negative diplococci (+); CSF bacterial culture (−); CSF N. meningitidis antigen assay (−); FilmArray Meningitis/Encephalitis panel (−) (UCLA) | Neisseria, probably not N. meningitidis, by CSF metagenomic NGS and phylogenetic analysis |

| Nocardiafarcinica§§ | Yes | CSF bacterial culture (−); CSF bacterial 16S rRNA PCR assay (−) (UW) | CSF PCR assay for N.farcinica (+), confirmed by Sanger sequencing (UCSF) |

| SLEV | No | — | CSF RT-PCR assay for SLEV (+) (CDC) |

| Streptococcus agalactiae¶¶ | Yes | CSF bacterial culture (−) | FilmArray Meningitis/Encephalitis panel, S. agalactiae (+) (BioFire) |

| S. mitis‖‖ | No | CSF bacterial culture (−); FilmArray Meningitis/Encephalitis panel (−) (SJCRH) | CSF bacterial 16S rRNA PCR assay, S. mitis group (+) (UW) |

Plus signs indicate positive tests, and minus signs indicate negative tests. CDC denotes Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, EBV Epstein–Barr virus, EV enterovirus, HEV hepatitis E virus, HHV-6 human herpesvirus type 6, HSV-1 herpes simplex virus type 1, HSV-2 herpes simplex virus type 2, ITS internal transcribed spacer, PCR polymerase chain reaction, PTLD post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disorder, qPCR quantitative PCR, rRNA ribosomal RNA, RT-PCR reverse-transcriptase PCR, SJCRH St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, SLEV St. Louis encephalitis virus, UW University of Washington, and VZV varicella–zoster virus.

These are strains of enterovirus B.

The patient, who was immunocompromised because of renal transplantation, made a full neurologic recovery after antiviral treatment with ganciclovir directed against EBV.

Both patients with HHV-6–associated encephalitis had undergone bone marrow transplantation for acute myelogenous leukemia and were treated with antiviral agents (ganciclovir, foscarnet, or both); HHV-6 limbic encephalitis occurring in this patient population is well described.13

This child was immunocompromised because of bone marrow transplantation and had a history of disseminated candidiasis and persistently elevated 1,3-β-D-glucan levels in CSF but negative CSF fungal culture. The patient was treated empirically with multiple courses of antibacterial agents (meropenem, vancomycin, cefepime, and ceftriaxone) and antifungal agents (caspofungin, fluconazole, and liposomal amphotericin B) before CSF samples were obtained for metagenomic NGS testing.

This HIV-1–infected patient had the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and a CD4 cell count of 40 and had received a diagnosis of an aggressive EBV-associated B-cell lymphoma on the basis of a liver biopsy. EBV-associated B-cell lymphoma of the CNS was not considered in the differential diagnosis until EBV was detected in the CSF by both metagenomic NGS and conventional confirmatory testing.

The patient was treated empirically with 8 days of piperacillin–tazobactam plus vancomycin followed by 32 days of meropenem plus vancomycin in addition to gentamicin, linezolid, and fluconazole before CSF samples were obtained for metagenomic NGS testing.

The patient was treated empirically with 4 days of meropenem before CSF samples were obtained for metagenomic NGS testing.

The patient was treated empirically for 6 hours with ceftriaxone, vancomycin, and metronidazole before CSF samples were obtained for metagenomic NGS testing. A total of 124 DNA metagenomic NGS sequences (out of 10.3 million) aligned to neisseria species, with Neisseria meningitidis being the closest match identified by SURPI+ (Sequence-based Ultra-Rapid Pathogen Identification). We subsequently generated an additional 355,366 metagenomic NGS sequences aligning to neisseria species by sequencing the CSF sample to a depth of approximately 1.65 billion raw reads. Phylogenetic analysis of the gene encoding 50S ribosomal protein L6 (rplF), commonly used for neisseria identification,14 positioned this species in the “Neisseria sicca/mucosa” subgroup (Fig. S2 in the Supplementary Appendix). However, because we cannot be sure that this is the exact species, the confirmatory test result is reported as “neisseria, probably not N. meningitidis.”

The patient was treated empirically with 8 days of piperacillin–tazobactam plus vancomycin before CSF samples were obtained for metagenomic NGS testing.

The patient was treated empirically with 2 days of ceftriaxone or ceftazidime plus vancomycin before CSF samples were obtained for metagenomic NGS testing.

The patient was treated empirically with meropenem, vancomycin, and amikacin immediately before CSF samples were obtained for metagenomic NGS testing.

In total, metagenomic NGS identified 32 infections, as compared with 27 infections with conventional direct-detection testing alone (defined as culture, PCR, or antigen testing of CSF without including serologic testing or testing of samples other than CSF) (Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Appendix). High host DNA background, which can decrease the sensitivity of metagenomic NGS testing, was typically seen at CSF cell counts of more than 200 cells per cubic milliliter (Fig. 2B).

Infections that were diagnosed solely by metagenomic NGS included St. Louis encephalitis virus (SLEV),15 hepatitis E virus,16,17 and Streptococcus agalactiae; these pathogens had not been considered by the treating clinicians for the patients. Metagenomic NGS also identified pathogens for which there was some degree of clinical suspicion, although conventional testing had returned negative (neisseria, Nocardia farcinica Candida tropicalis, Enterobacter aerogenes [now renamed Klebsiella aerogenes], S. mitis, and Enterococcus faecalis). Other orthogonally confirmed metagenomic NGS findings included microbes that were of unclear significance (longitudinal detection of MW polyomavirus in an immune-compromised child18), were directly related to noninfectious clinical syndromes (Epstein–Barr virus [EBV] detection in a patient with EBV-positive primary hepatic lymphoma and associated encephalitis), or were not specifically tested for but would probably have been positive by conventional testing (two cases of enteroviral meningitis).

In 26 patients, metagenomic NGS testing of CSF was negative even though conventional microbiologic testing across all tissue types revealed an infectious cause (Table S2 in the Supplementary Appendix). These clinical false negative cases by metagenomic NGS fell into three categories: cases diagnosed by serologic testing alone (11 infections), for which conventional direct-detection tests from CSF (e.g., culture, PCR, and antigen-based testing) were also negative; cases diagnosed from samples other than CSF (7 infections), such as brain biopsy; and cases negative by metagenomic NGS owing to low titers of pathogens in CSF (8 infections), as evidenced by conventional microbiologic tests that were borderline positive or had discordant results. The last category included infections from Mycobacterium bovis, M. tuberculosis, Cryptococ cus neoformans, Propionibacterium acnes, fusobacterium, Staphylococcus aureus, cytomegalovirus, and herpes simplex virus type 2.

It is notable that reads mapping to all 6 missed bacterial and fungal pathogens were detected, but their abundance did not meet preestablished reporting thresholds (see the Supplementary Appendix).9 Metagenomic NGS also detected 19 viral infections adjudicated as incidental to the neurologic illness after chart review (Table S3 in the Supplementary Appendix). In 3 cases, results of metagenomic NGS were found to be false positives after discrepancy testing (pantoea, S. aureus, and S. agalactiae) and were attributed to sample contamination from the environment or normal human flora.

Clinical Microbial Sequencing Board

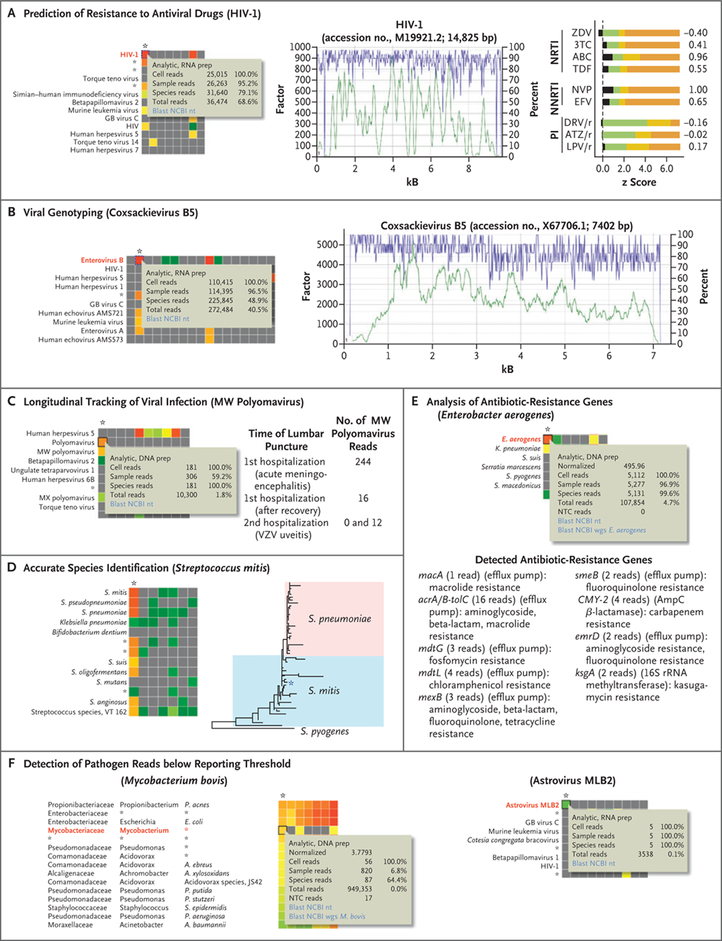

A clinical microbial sequencing board was established to hold weekly teleconferences for review of metagenomic NGS in clinical context and to communicate results of supplementary metagenomic NGS analyses, including species and strain typing, reporting of potential pathogens detected below preestablished thresholds, analysis of longitudinally collected samples in clinical context, and characterization of drug resistance (Figs. 2C and 3). During discussions of the clinical microbial sequencing board, clinicians expressed that the results of metagenomic NGS were useful for providing reassurance to the patient, surrogate, or both (e.g., SLEV); supporting the clinical decision to stop unnecessary empirical treatments (e.g., acyclovir for empirical coverage of herpesvirus infections); helping to rule out coinfections (e.g., detection of EBV alone in cases of post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disease or lymphoma with encephalitis); diagnosing infectious syndromes (e.g., CNS escape in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection23); and expediting appropriate treatment (e.g., chemotherapy for lymphoma or immunosuppressive agents, including glucocorticoids, for acute demyelinating encephalomyelitis) in suspected noninfectious cases, as well as for epidemiologic purposes, such as virus genotyping (e.g., positive enterovirus cases).

Figure 3 (facing page). Supplementary Metagenomic NGS Analyses.

Supplementary analyses of the metagenomic NGS data were performed and results discussed during weekly teleconferences with the clinical microbial sequencing board. The asterisk denotes the column on the interactive SURPI+ heat map corresponding to the patient’s CSF sample, and pop-up windows highlight the cell corresponding to the given species hit (see Supplementary Appendix for additional details). For Panels A and B, the green tracing corresponds to the coverage at a given nucleotide position (y axis, left), and the purple tracing corresponds to the pairwise identity (y axis, right) after automated mapping by SURPI+ of metagenomic NGS reads to the most closely matched viral reference genome in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) nucleotide (nt) database. Panel A shows prediction of resistance to antiviral drugs. Mapping HIV-1 reads from a patient CSF sample to the most closely matched genome in the reference database shows that the complete viral genome can be assembled (middle), thus enabling prediction of antiviral drug resistance (right). Predicted z scores were obtained with the use of Web-based geno2pheno software.19 The z scores corresponding to a subset of commonly prescribed antiretroviral drugs (black) are shown relative to reference z-score ranges for susceptible (green), intermediate (yellow), or resistant (orange) phenotypes. 3TC denotes lamivudine, ABC abacavir, ATZ/r ritonavir-boosted atazanavir, DRV/r ritonavir-boosted darunavir, EFV efavirenz, LPV/r ritonavir-boosted lopinavir, NNRTI nonnucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor, NRTI nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor, NVP nevirapine, PI protease inhibitor, TDF tenofovir, and ZDV zidovudine. Panel B shows viral genotyping. The viral genome in an enterovirus B–positive case was assembled from metagenomic NGS reads, and the specific viral strain was identified as coxsackievirus B5 by SURPI+ (right). Panel C shows longitudinal tracking of viral infection. MW polyomavirus, originally identified in stool from children with diarrhea,18 was detected in an immunocompromised child presenting with acute meningoencephalitis. The finding was thought to be of unclear clinical significance, although no other infectious cause was identified. Zero and 12 reads to MW polyomavirus were detected in two CSF samples obtained 3 months later, during a second hospitalization for documented varicella–zoster virus (VZV) uveitis. Panel D shows accurate species identification. Assembly of the full-length 16S rRNA gene from metagenomic NGS reads enabled phylogenetic analysis and assignment of the species as Streptococcus mitis. A phylogenetic tree was obtained by aligning 25 representative S. mitis and 25 representative Streptococcus pneumoniae strains (with Streptococcus pyogenes as an outgroup) with the patient’s 16S rRNA sequence with the use of MAFFT20 at default settings, followed by tree construction with the use of PhyML.21 Panel E shows analysis of antibiotic-resistance genes. Such genes were identified by alignment of Enterobacter aerogenes (now renamed Klebsiella aerogenes) metagenomic NGS reads to the comprehensive antibiotic-resistance database.22 Panel F shows the detection of pathogen reads below the reporting threshold, with heat maps corresponding to two pathogens (Mycobacterium bovis and astrovirus MLB2) that were not reported as positive by metagenomic NGS because the number and distribution of reads did not meet preestablished thresholds.9 In Panels E and F, AmpC denotes class C β-lactamase, and wgs the NCBI whole-genome shotgun database.

Some clinicians expressed a wish that the turnaround time for metagenomic NGS testing could be shortened to increase the likelihood that the results would be clinically actionable. For the case of MW polyomavirus identified by metagenomic NGS testing in an immunocom-promised child, one of the clinicians expressed that this result complicated clinical management, because it remained unknown whether the detected virus played a pathogenic role in the child’s acute neurologic illness. Among the 13 cases diagnosed solely by metagenomic NGS, treating physicians stated that the results of metagenomic NGS favorably affected their clinical reasoning in 8 cases (62%) (Fig. 2D) (also see the Supplementary Appendix). In 7 of these 8 cases, the results of metagenomic NGS guided therapy (Fig. 2E) (also see the Supplementary Appendix).

Discussion

We evaluated the clinical usefulness of metagenomic NGS for diagnosing neurologic infections in a series of patients with idiopathic acute meningitis, encephalitis, or myelitis at the time of enrollment, in parallel with conventional microbiologic testing. Thus, we sought to define the real-life performance of metagenomic NGS testing in a difficult-to-diagnose patient population for whom the assay is most likely to be performed, given current issues of cost, accessibility, and turnaround time. The highest diagnostic yield resulted from a combination of metagenomic NGS of CSF and conventional testing, including serologic testing and testing of sample types other than CSF. In this selected population, the metagenomic NGS assay identified more potential pathogens than conventional direct-detection testing of CSF (32 vs. 27). A total of 13 infections were diagnosed solely by metagenomic NGS. It is notable that 8 of these 13 diagnoses had a clinical effect, with physicians adjusting treatment in 7 cases. These findings show that neurologic infections remain undiagnosed in a proportion of patients despite conventional testing and demonstrate the potential usefulness of clinical metagenomic NGS testing in these patients.

The overall percentage of study patients with an infectious diagnosis (27.9% [57 patients]) is lower than the percentages reported in the literature of 29 to 60%.1–3 CSF samples for metagenomic NGS testing were obtained a median of 3 days after initial presentation to the hospital. However, in 35.3% of the patients (72 patients), the only available CSF sample was obtained from a second or later lumbar puncture at a median of 8 days after presentation (e.g., CSF from an initial lumbar puncture that was performed at an outside, non–study-site hospital was not always available). As a result, CSF samples for metagenomic NGS testing on these 72 patients were obtained later in the clinical course, often after patients were exposed to empirical antibiotics or after CSF samples had undergone multiple freeze–thaw cycles, thus potentially decreasing diagnostic yield. In addition, 42.6% of the patients who were enrolled in the study (87 of 204) were identified by physician referral, which probably biased enrollment toward patients with cases that were particularly challenging to diagnose.

In 8 of 13 samples that yielded a diagnosis by metagenomic NGS only, the causative pathogen was either not considered by treating clinicians or had tested negative by conventional testing and was therefore considered an unlikely cause. These findings highlight a key advantage of metagenomic NGS — that it does not rely on a priori selection of targeted pathogens but rather is able to detect many potential infectious agents in a single assay.5,6,24 Thus, the unbiased approach of metagenomic NGS may be useful for diagnostic testing of CSF samples, because sample volume and availability are often limited. The results of metagenomic NGS can also be valuable even when concordant with results of conventional testing (19 of 32 infections detected by metagenomic NGS), not only providing reassurance that the conventionally obtained diagnosis is correct but also potentially detecting or ruling out coinfections, especially in immune-compromised patients.

Of the 26 infections missed by metagenomic NGS, 18 were diagnosed by serologic testing alone or from sample types other than CSF. Like culture, PCR, and antigen-based testing, metagenomic NGS is fundamentally a direct-detection method and relies on the presence of nucleic acid from the causative pathogen in the CSF sample. Thus, the serologic diagnoses of West Nile virus (4 infections), varicella–zoster virus (3), and neurosyphilis (2) (Table S2 in the Supplementary Appendix) are not unexpected given the poor performance of corresponding pathogen-specific PCR assays for these organisms.25,26 Indeed, among 8 of these 9 cases with remaining CSF available, all 8 samples tested negative by pathogen-specific PCR. It is also not surprising that analysis of samples other than CSF, such as biopsy tissue or abscess fluid, established the diagnosis for some cases in the study, given direct sampling of the local infection site.

Modeled after the “tumor board” concept in oncology, the clinical microbial sequencing board afforded an opportunity to discuss reported results of metagenomic NGS in a clinical context, as well as to communicate additional information from supplementary metagenomic NGS analyses. Although the clinical usefulness of these analyses remains to be established, the generation and reporting of supplementary metagenomic NGS results are conceptually similar to pathologist-interpreted genomic analyses of variants of unknown significance in oncologic testing,27 which provide useful information to guide physicians beyond straightforward reporting of a binary test result (i.e., variant “detected” or “not detected”). However, clinical interpretation of supplementary metagenomic NGS results may be challenging given the lack of a reference standard in many instances.

Preestablished clinical thresholds for reporting a positive test for pathogens on metagenomic NGS were intentionally conservative in order to minimize false positive detections.8,9 In six of eight cases missed by metagenomic NGS owing to low pathogen titers, species-specific reads from the causative pathogen could still be identified. This raises the question of whether it would be appropriate to establish more liberal reporting thresholds for high-priority pathogens than for organisms such as environmental bacteria that are of unclear clinical significance. Alternatively, low-abundance metagenomic NGS detection of high-priority pathogens, such as M. tuberculosis or astrovirus MLB2 (see the Supplementary Appendix), could be discussed in settings such as the clinical microbial sequencing board, thereby prompting additional diagnostic testing that targets the specific pathogen.

Although metagenomic NGS testing was still useful in identifying a potential causative organism in CSF samples with a high host background (i.e., samples in which the normalized read counts corresponding to the internal spiked DNA or RNA control did not meet preestablished thresholds), our findings suggest that a negative test in this context should be interpreted with caution owing to the higher risk of false negative results. However, metagenomic NGS that is performed in combination with conventional testing may potentially be useful for ruling out an active infection in patients with suspected autoimmune encephalitis, who typically present with only mild-to-moderate lymphocytic pleocytosis (<100 cells per cubic millimeter)28 and thus low host background in CSF. Treating clinicians are often reluctant to initiate immunosuppressive therapies for autoimmune disease without a reasonably high degree of confidence that an occult infection has not been missed.

Our data show that clinical metagenomic NGS of CSF represents a potential step forward in the diagnosis of meningoencephalitis. This diagnostic approach may guide earlier and more targeted treatments for neuroinvasive infections, identify emerging infections and disease phenotypes, and accelerate the workup and treatment for noninfectious causes. The preferred timing and patient population for clinical metagenomic NGS testing remain to be defined through further research.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R01HL105704 (to Dr. Chiu), K08NS096117 (to Dr. Wilson), and K23AI28069 (to Dr. Messacar), a University of California Center for Accelerated Innovation grant funded by NIH grant U54HL119893 and NIH–National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences University of California, San Francisco–Clinical and Translational Science Institute grant UL1TR000004 (to Dr. Chiu), a grant from the California Initiative to Advance Precision Medicine (to Dr. Chiu, Ms. Sample, Ms. Zorn, Mr. Federman, Mr. Stryke, Drs. Fulton and Naccache, Mr. Murkey, Drs. Vespa, Humphries, and Klausner, Ms. Memar, Ms. Ocampo, and Drs. Polage, Wilson, and Miller), a grant from the Chan Zuckerberg Biohub (to Dr. DeRisi), a grant from the Charles and Helen Schwab Foundation (to Drs. Chiu and Miller), a grant from the George and Judy Marcus Innovation Fund (to Drs. Chiu and Miller), an endowment from the Rachleff family (to Dr. Wilson), and a grant from the Sandler and William K. Bowes, Jr., Foundations (to Dr. Chiu, Ms. Zorn, Ms. Sample, and Drs. Wilson, Gelfand, Fulton, Miller, Chow, and DeRisi).

We thank Danielle Ingebrigtsen, Walter Lorizio, Tiffany Kwak, Becky Fung, and Lydia Dang at the UCSF Clinical Microbiology Laboratory for their efforts in running the metagenomic next-generation sequencing assay; Herb Sandler, William Bowes, Charles and Helen Schwab, and George and Judy Marcus for their encouragement; and the patients and their families for their participation in this study.

Appendix

The authors’ full names and academic degrees are as follows: Michael R. Wilson, M.D., M.A.S., Hannah A. Sample, B.S., Kelsey C. Zorn, M.H.S., Shaun Arevalo, B.S., C.L.S., Guixia Yu, B.S., John Neuhaus, Ph.D., Scot Federman, B.A., Doug Stryke, B.S., Benjamin Briggs, M.D., Ph.D., Charles Langelier, M.D., Ph.D., Amy Berger, M.D., Ph.D., Vanja Douglas, M.D., S. Andrew Josephson, M.D., Felicia C. Chow, M.D., M.A.S., Brent D. Fulton, Ph.D., Joseph L. DeRisi, Ph.D., Jeffrey M. Gelfand, M.D., M.A.S., Samia N. Naccache, Ph.D., Jeffrey Bender, M.D., Jennifer Dien Bard, Ph.D., D(ABMM), Jamie Murkey, B.S., Magrit Carlson, M.D., Paul M. Vespa, M.D., Tara Vijayan, M.D., Paul R. Allyn, M.D., Shelley Campeau, Ph.D., D(ABMM), Romney M. Humphries, Ph.D., D(ABMM), Jeffrey D. Klausner, M.D., Czarina D. Ganzon, M.D., Fatemeh Memar, B.S., Nicolle A. Ocampo, B.S., Lara L. Zimmermann, M.D., Stuart H. Cohen, M.D., Christopher R. Polage, M.D., M.A.S., Roberta L. DeBiasi, M.D., Barbara Haller, M.D., Ronald Dallas, Ph.D., Gabriela Maron, M.D., Randall Hayden, M.D., Kevin Messacar, M.D., Samuel R. Dominguez, M.D., Ph.D., Steve Miller, M.D., Ph.D., and Charles Y. Chiu, M.D., Ph.D.

The authors’ affiliations are as follows: the Departments of Neurology (M.R.W., V.D., S.A.J., F.C.C., J.M.G.), Biochemistry and Biophysics (H.A.S., K.C.Z., J.L.D.), Laboratory Medicine (S.A., G.Y., S.F., D.S., B.B., B.H., S.M., C.Y.C.), and Epidemiology and Biostatistics (J.N.), the Department of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases (C.L., C.Y.C.), the Department of Medicine, Division of Hospital Medicine (A.B.), and Weill Institute for Neurosciences (M.R.W., V.D., S.A.J., F.C.C., J.M.G.), University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), UCSF–Abbott Viral Diagnostics and Discovery Center (S.A., G.Y., S.F., D.S., B.B., C.Y.C.), the Chan Zuckerberg Biohub (C.L., J.L.D.), and Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital (B.H.), San Francisco, the School of Public Health, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley (B.D.F.), Children’s Hospital Los Angeles (S.N.N., J.B., J.D.B.), the Department of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases (J.M., M.C., T.V., P.R.A., J.D.K.), and the Departments of Neurology (P.M.V.) and Pathology and Laboratory Medicine (S.C., R.M.H.), University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, and the Departments of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine (C.D.G., F.M., N.A.O., C.R.P.) and Neurological Surgery (L.L.Z.) and the Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases (S.H.C., C.R.P.), University of California, Davis, Davis — all in California; the Children’s National Medical Center and George Washington University School of Medicine, Washington, DC (R.L.D.); St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, TN (R.D., G.M., R.H.); and Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora (K.M., S.R.D.).

Footnotes

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

References

- 1.Glaser CA, Gilliam S, Schnurr D, et al. In search of encephalitis etiologies: diagnostic challenges in the California Encephalitis Project, 1998–2000. Clin Infect Dis 2003; 36: 731–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glaser CA, Honarmand S, Anderson LJ, et al. Beyond viruses: clinical profiles and etiologies associated with encephalitis. Clin Infect Dis 2006; 43: 1565–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Granerod J, Ambrose HE, Davies NW, et al. Causes of encephalitis and differences in their clinical presentations in England: a multicentre, population-based prospective study. Lancet Infect Dis 2010; 10: 835–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khetsuriani N, Holman RC, Anderson LJ. Burden of encephalitis-associated hospitalizations in the United States, 1988–1997. Clin Infect Dis 2002; 35: 175–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forbes JD, Knox NC, Ronholm J, Pagotto F, Reimer A. Metagenomics: the next culture-independent game changer. Front Microbiol 2017; 8: 1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldberg B, Sichtig H, Geyer C, Ledeboer N, Weinstock GM. Making the leap from research laboratory to clinic: challenges and opportunities for next-generation sequencing in infectious disease diagnostics. MBio 2015; 6(6): e01888–e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simner PJ, Miller S, Carroll KC. Understanding the promises and hurdles of metagenomic next-generation sequencing as a diagnostic tool for infectious diseases. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 66: 778–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schlaberg R, Chiu CY, Miller S, Procop GW, Weinstock G. Validation of metagenomic next-generation sequencing tests for universal pathogen detection. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2017; 141: 776–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller S, Naccache SN, Samayoa E, et al. Laboratory validation of a clinical metagenomic sequencing assay for pathogen detection in cerebrospinal fluid. Genome Res 2019; 29: 831–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guidance for industry: statistical guidance on reporting results from studies evaluating diagnostic tests. Rockville, MD: Food and Drug Administration, Center for Devices and Radiological Health, 2007: 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naccache SN, Federman S, Veeraraghavan N, et al. A cloud-compatible bioinformatics pipeline for ultrarapid pathogen identification from next-generation sequencing of clinical samples. Genome Res 2014; 24: 1180–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kohn MA, Carpenter CR, Newman TB. Understanding the direction of bias in studies of diagnostic test accuracy. Acad Emerg Med 2013; 20: 1194–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ogata M, Fukuda T, Teshima T. Human herpesvirus-6 encephalitis after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation: what we do and do not know. Bone Marrow Transplant 2015; 50: 1030–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bennett JS, Watkins ER, Jolley KA, Harrison OB, Maiden MC. Identifying Neisseria species by use of the 50S ribosomal protein L6 (rplF) gene. J Clin Microbiol 2014; 52: 1375–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chiu CY, Coffey LL, Murkey J, et al. Diagnosis of fatal human case of St. Louis encephalitis virus infection by metagenomic sequencing, California, 2016. Emerg Infect Dis 2017; 23: 1964–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamar N, Selves J, Mansuy J-M, et al. Hepatitis E virus and chronic hepatitis in organ-transplant recipients. N Engl J Med 2008; 358: 811–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murkey JA, Chew KW, Carlson M, et al. Hepatitis E virus-associated meningoencephalitis in a lung transplant recipient diagnosed by clinical metagenomic sequencing. Open Forum Infect Dis 2017; 4(3): ofx121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siebrasse EA, Reyes A, Lim ES, et al. Identification of MW polyomavirus, a novel polyomavirus in human stool. J Virol 2012; 86: 10321–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beerenwinkel N, Däumer M, Oette M, et al. Geno2pheno: estimating phenotypic drug resistance from HIV-1 genotypes. Nucleic Acids Res 2003; 31: 3850–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katoh K, Misawa K, Kuma K, Miyata T. MAFFT: a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res 2002; 30: 3059–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guindon S, Delsuc F, Dufayard JF, Gascuel O. Estimating maximum likelihood phylogenies with PhyML. Methods Mol Biol 2009; 537: 113–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McArthur AG, Waglechner N, Nizam F, et al. The Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2013; 57: 3348–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Edén A, Fuchs D, Hagberg L, et al. HIV-1 viral escape in cerebrospinal fluid of subjects on suppressive antiretroviral treatment. J Infect Dis 2010; 202: 1819–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Naccache SN, Peggs KS, Mattes FM, et al. Diagnosis of neuroinvasive astrovirus infection in an immunocompromised adult with encephalitis by unbiased next-generation sequencing. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 60: 919–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DeBiasi RL, Tyler KL. Molecular methods for diagnosis of viral encephalitis. Clin Microbiol Rev 2004; 17: 903–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marra CM, Gary DW, Kuypers J, Jacobson MA. Diagnosis of neurosyphilis in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Infect Dis 1996; 174: 219–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li MM, Datto M, Duncavage EJ, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation and reporting of sequence variants in cancer: a joint consensus recommendation of the Association for Molecular Pathology, American Society of Clinical Oncology, and College of American Pathologists. J Mol Diagn 2017; 19: 4–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Graus F, Titulaer MJ, Balu R, et al. A clinical approach to diagnosis of autoimmune encephalitis. Lancet Neurol 2016; 15: 391–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.