Abstract

Conservatives report greater life satisfaction than liberals, but this relationship is relatively weak. To date, the evidence is limited to a narrow set of well-being measures that ask participants for a single assessment of their life in general. We address this shortcoming by examining the relationship between political orientation and well-being using measures of life satisfaction, affect, and meaning and purpose in life. Participants completed well-being measures after reflecting on their whole life (Studies 1a, 1b, and 2), at the end of their day (Study 3), and in the present moment (Study 4). Across five studies, conservatives reported more meaning and purpose in life than liberals at each reporting period. This finding remained significant after adjusting for religiosity and was usually stronger than the relationships involving other well-being measures. Finally, meaning in life was more closely related to social conservatism than economic conservatism.

Keywords: meaning in life, well-being, political orientation, ecological momentary assessment, satisfaction with life

Political conservatives tend to be happier than liberals (Taylor, Funk, & Craighill, 2006), a finding that has been labeled the “happiness gap” in media reporting. One conservative commentator even described it as “…niftily self-reinforcing; it depresses liberals” (Will, 2006). The observation motivated different approaches to understand why conservatives may be more satisfied with their lives than liberals (e.g., Napier & Jost, 2008; Schlenker, Chambers, & Le, 2012; Wojcik, Hovasapian, Graham, Motyl, & Ditto, 2015). Because the relationship between political orientation and life satisfaction is relatively weak (Onraet, Hiel, & Dhont, 2013), much of the current research has focused on identifying specific variables that moderate this relationship (e.g., Stavrova & Luhmann, 2016). To date, this discussion has treated self-reported happiness, life-satisfaction, and temporary affective states as largely equivalent indicators of well-being. However, these indicators capture different aspects and a closer examination of their relationship with political orientation is warranted.

Aspects of Well-being

In conceptualizing well-being, it is useful to distinguish between how people evaluate their lives (evaluative well-being); how they feel moment-to-moment-when living their lives (experienced well-being); and how meaningful their lives seem to them (eudaimonic well-being; for discussions see Kahneman, 1999; Schwarz & Strack, 1999; Steptoe, Deaton, & Stone, 2015). Sometimes the conceptualization of eudaimonic well-being is extended beyond meaning in life to include several other constructs, such as personal growth and flourishing (Ryan & Deci, 2001). Each type of well-being can be assessed at different reporting periods, ranging from the current moment to one’s life as a whole. Measures of life satisfaction and meaning in life often refer to the respondent’s life as a whole, whereas measures of affect usually refer to shorter durations, such as the current day or situation.

Present research

To date, research on political orientation and well-being has only considered evaluative and experiential well-being, and has typically assessed both with regard to one’s life as a whole. Retrospective reports of affect over extended time periods are reconstructions based on general assumptions about one’s life and may not capture actual affective experience (National Research Council, 2013, pp. 29–30; Robinson & Clore, 2002; Schwarz, 2012; Schwarz, Kahneman, & Xu, 2009). In a few studies, participants reported their momentary affect at one time in response to a particular situation. Single reports of momentary affect in response to specific situations do not provide a representative sample of time points of one’s life and may not adequately characterize individual differences in affect.

Moreover, the relationship between political orientation and meaning and purpose in life has not been addressed. Empirically, measures of meaning and purpose in life can differ from evaluative and experiential well-being in terms of their correlates with other variables (e.g., Nezlek, Newman, & Thrash, 2017; Tov & Lee, 2015).

The present studies fill these gaps by assessing life satisfaction, positive and negative affect, and meaning and purpose in life with respect to different time frames, including life as a whole (studies 1a, 1b, and 2), a single day (through end-of-day reports; study 3), and the current situation (through concurrent measures; study 4). Because conservatives tend to be more religious than liberals (Feldman & Johnston, 2014), and because religiosity is a strong predictor of meaning in life (e.g., Steger & Frazier, 2005), we statistically adjusted for levels of religiosity in each study to determine the unique predictive effect of political orientation on meaning in life. We additionally examined differential effects of social and economic conservatism on meaning in life and satisfaction with life to provide some insight into individual differences concerning specific political issues.

Studies 1a – 1b

In Study 1a we examined the relationship between conservative political orientation and a global report of meaning in life using data from the European Values Survey, which includes large, nationally-representative samples from 14 European countries, the United States, and Canada (http://www.europeanvaluesstudy.eu). Study 1b replicated these analyses with data from the Baylor Religion Study, a nationally representative U.S. sample (https://www.baylor.edu/baylorreligionsurvey/).

Method

Study 1a

An item measuring meaning in life was included in Wave 1, collected between 1981 – 1984. Data from 19,051 (Mage = 41.03, SD = 17.86; 52.2% female) participants were used in the primary analyses. Of the 19,051 participants who completed the meaning in life measure, 15,319 participants completed the political orientation item. The items examined for the primary analyses included meaning in life, satisfaction with life, political orientation, religiosity, health, and income. The exact question wording, response options, and descriptive statistics are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Item wording, response options, and descriptive statistics of measures used in the European Values Survey, Study 1a.

| Measure | Item wording | Response options | Mean | Variance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Within-country | Between-country | ||||

| Meaning in life | How often, if at all, do you have the feeling that life is meaningless? | 1 = Often, 2 = Sometimes, 3 = Rarely, 4 = Never | 3.13 | .83 | .02 |

| Satisfaction with life | All things considered, how satisfied are you with your life as a whole these days? | 1 = Dissatisfied, 10 = Satisfied | 7.56 | 3.65 | .26 |

| Political orientation | In political matters, people talk of ‘the left’ and ‘the right’. How would you place your views on this scale generally speaking? | 1 = Left, 10 = Right | 5.62 | 4.11 | .26 |

| Religiosity | Apart from weddings, funerals and christenings, about how often do you attend religious services these days? | 1 = More than once a week, 2 = Once a week, 3 = Once a month, 4 = Only on special holy days/Christmas/Easter days, 5 = Other specific holy days, 6 = Once a year, 7 = Less Often, 8 = Never, practically never | 4.84 | 5.40 | 1.97 |

| Health | All in all, how would you describe your state of health these days? Would you say it is… | 1 = Very good, 2 = Good, 3 = Fair, 4 = Poor, 5 = Very poor | 2.04 | .83 | .05 |

| Income | Would you please give me the letter group which best represents the total annual income before taxes of all the members of your immediate family living in your household? | Categories varied by country and were recoded from 1 to 11. | 4.97 | 5.83 | .66 |

Study 1b

A U.S. survey of 1,595 (Mage = 51.01, SD = 16.28; 55.2% female) respondents, with data collected in 2007, allowed for a replication of these analyses (Baylor University, 2007). These data were collected by the Baylor Institute of Religion as part of a Templeton Foundation grant and in collaboration with the Gallup Organization. Questionnaires were mailed to a representative sample in the US, and demographics were similar to the General Social Survey.

Political orientation was measured with a single item that read, “How would you describe yourself politically?” Responses were recorded on a 7-point scale (1 = extremely conservative, 4 = moderate, 7 = extremely liberal). This item was reversed coded to be consistent with the way political orientation was measured in the other studies (M = 4.29, SD = 1.62). Purpose in life was assessed with a single item that read, “My life has a real purpose” with responses reported on a 4-point scale (1 = Strongly disagree …, 4 = Strongly agree; M = 3.18, SD = .63). Additional details are reported in the SOM.

Results

Study 1a

We used multilevel modeling with the program HLM 7.0 (Raudenbush, Bryk, & Congdon, 2011) and nested individuals within countries to account for between- and within-country variation in the European Values Survey. Political orientation was entered group-mean centered (i.e., centered around each country’s mean) at level 1 to account for any country-level differences, and the frequency with which they felt as if their life was meaningless was the outcome measure as follows:

Those who aligned themselves with the “right” reported greater meaning in life, γ10 = .03, 95% CI [.02, .05], t-ratio = 4.81, p < .001, r = .091 . HLM provides unstandardized coefficients, which means that a 1-point increase in political orientation indicates a .03 increase in meaning in raw scores. That is, conservatives were more likely to endorse low frequency options in response to how often they thought their lives were meaningless. We also tested quadratic and cubic relationships and neither were significant (p = .85, p = .87, respectively). Because conservatives tend to be more religious than liberals and because religiosity is a strong predictor of meaning in life, we adjusted statistically for religiosity in all analyses. After entering religiosity, conservatism was still significantly related to meaning in life, γ10 = .03, t-ratio = 4.10, p < .001. After additionally adding age, gender, area of residence (rural area-village, small-medium town, or large town) and income as predictors at level 1, political orientation was marginally related to meaning in life, γ10 = .02, t-ratio = 2.04, p = .062.

Political conservatives in these countries also reported greater satisfaction with life than liberals, γ10 = .09, 95% CI [.07, .11], t-ratio = 8.37, p < .001, r = .10, consistent with Onraet, Van Assche, Roets, Haesevoets, and Van Hiel (2017). The standardized coefficient from the meaning in life model was not significantly different from the standardized coefficient in the satisfaction with life model, χ2(1) = 2.30, p = .13. The estimated within-country correlation between life satisfaction and meaning in life was .30 (using a method that relies on reduction of level 1 variance when meaning in life was entered as a predictor; see Nezlek, 2012, pp. 84–85 and the Supplemental materials for details).

In sum, conservatives reported higher meaning in life and higher life-satisfaction than liberals. This was the case for representative samples from the 16 countries, which indicates that the observation is robust across diverse segments of Western culture. However, the data were collected in the early 1980s, raising questions about stability over time. To address this issue, we analyzed data from the Baylor Religion Survey, based on a representative U.S. sample collected in 2007 (Baylor University, 2007).

Study 1b

Using ordinary least squares regression, we regressed purpose in life on political orientation and found that conservatives reported greater purpose in life than liberals, b = .05, 95% CI [.03, .07], t(1481) = 5.05, p < .001, r = 13. This relationship held after statistically adjusting for age, gender, area of residence, income, and education, b = .06, 95% CI [.04, .08], t(1393) = 5.83, p < .001. We also statistically adjusted for religious attendance and found that political orientation was still positively related to purpose in life with demographic controls, b = .02, 95% CI [.00, .05], t(1344) = 2.11, p = .04. We also examined non-linear relationships. A significant quadratic relationship indicated a spike in purpose in life among the extreme conservatives, b = .01, t(1480) = 2.19, p = .03. In sum, data from representative samples showed that conservatives reported more meaning/purpose in life than liberals in the early 1980s and more recently in 2007.

Study 2

Study 2 provides a replication of these findings using psychometrically robust measures of each well-being measure instead of single-item survey measures. It also allows us to compare how strongly meaning in life and satisfaction with life are related to political orientation and to examine whether these measures would differentially relate to social and economic conservatism.

Method

We used data from YourMorals.org, an online psychological research website in which participants receive results about their responses in exchange for participating. Participants were allowed to complete as many or as few of the available measures on the website as they pleased. To maximize power, we conducted separate analyses for participants who completed the meaning in life measure and for participants who completed the satisfaction with life measure. That is, we did not restrict our analyses to participants who completed both measures. Data were downloaded on July 26, 2017 and included responses recorded as early as October 7, 2010.

3,322 participants (Mage = 32.81, SD = 14.47; 58.17% male) completed measures of political orientation and meaning in life. A measure of political orientation assessed the extent to which participants were liberal or conservative. The 7-point scale (1 = Very liberal, 4 = Moderate/middle-of-the-road, 7 = Very conservative) (M = 2.87, SD = 1.62) also included additional options for “Don’t know/not political”, “Libertarian,” and “Other.” Meaning in life was assessed with 5 items from the Presence subscale of the Meaning in Life Questionnaire (e.g., “I understand my life’s meaning”; Steger, Frazier, Oishi, & Kaler, 2006). Responses were recorded on a 7-point scale (1 = absolutely untrue, 7 = absolutely true) (M = 4.32, SD = 1.64, α = .90).

Social and economic political orientation were assessed with the following items: “In general, how liberal (left-wing) or conservative (right-wing) are you on social issues?” (M = 2.39, SD = 1.61) and “In general, how liberal (left-wing) or conservative (right-wing) are you on economic issues?” (M = 3.84, SD = 1.87) Responses were recorded on a 7-point scale (1 = Very liberal, 4 = Moderate/middle-of-the-road, 7 = Very conservative) with additional choices for “don’t know” and “can’t pick one label.”

40,327 participants (Mage = 37.31, SD = 15.33; 53.15% male) who completed the political orientation item also completed the Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985). This scale includes 5 items with responses that ranged on a 7-point scale (1 = Strongly disagree, 7 = Strongly agree) (M = 4.50, SD = 1.43, α = .89).

Results

Similar to Studies 1a – 1b, conservatives reported more meaning in life than liberals, b = .17, 95% CI [.13, .21], t(2387) = 8.58, p < .001, r = .17. This unstandardized coefficient remained essentially the same even after adjusting statistically for age, gender, and level of education, b = .18, t(2276) = 9.29, p < .001. (The sample sizes varied depending on how many participants completed demographic and third variables, which are optional on the YourMorals.org website.) Political orientation also remained significantly related to meaning in life after adjusting for religiosity with demographic controls, b = .05, t(1484) = 2.08, p = .04 and without, b = .06, t(1500) = 2.11, p = .04. Conservatives also reported more satisfaction with their lives than liberals, b = .05, 95% CI [.04, .06], t(33706) = 9.56, p < .001, r = .05, consistent with previous research (e.g., Wojcik et al., 2015). This relationship was significantly weaker than the relationship with meaning in life, z= 5.79, p < .001. Meaning in life and satisfaction with life were also positively correlated, r(1107) = .49, p < .001.

To understand why conservatives report more meaning in life than liberals, we examined the relationships between political orientation regarding social and economic issues (measured as individual differences) and meaning in life and satisfaction with life. In separate analyses, meaning in life was positively related to conservatism on social issues, r(2655) = .19, p < .001, and conservatism on economic issues, r(2557) = .08, p < .001. However, the relationship with social conservatism was significantly larger, z = −5.21, p < .001. We entered both social conservatism and economic conservatism as predictors simultaneously into a multiple regression. Social conservatism was significantly related to meaning in life, b = .19, t(2501) = 8.66, p < .001, whereas economic conservatism was not significantly related to meaning in life, b = −.01, t(2501) = −0.30, p = .77.

In contrast, the correlation between social conservatism and satisfaction with life, r(11825) = .06, p < .001, was significantly weaker than the correlation between economic conservatism and satisfaction with life, r(11825) = .10, p < .001, z = 3.76, p < .001. After adding each predictor simultaneously into a multiple regression, social conservatism was not significantly related to satisfaction with life, b = .02, t(11824) = 1.69, p = .09, whereas economic conservatism was, b = .07, t(11824) = 8.24, p < .001. These findings suggest that individual differences in distinct political issue positions relate differentially to meaning in life and satisfaction with life. The potential reasons why conservatives report greater satisfaction with life (e.g., rationalization of income inequality) might differ from the reasons why conservatives report more meaning in life.

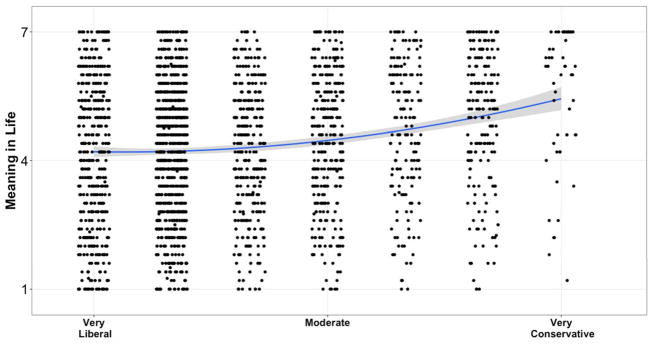

Finally, we further explored the relationship between political orientation and meaning in life by examining non-linear relationships. We found a significant quadratic relationship between political conservatism and meaning in life, b = .04, t(2386) = 3.28, p = .001; (See Figure 1). This shows that conservatives generally reported more meaning in life than liberals, and the slope spiked upwards among individuals who were very conservative.

Figure 1.

Study 2 quadratic relationship between political orientation and trait meaning in life scores. We used the jitter function to show densities of the political orientation responses.

Study 3

Method

In Study 3, we moved beyond global reports of well-being and examined end-of-day reports of well-being (including life satisfaction, affect, and meaning in life). 141 undergraduate students (Mage = 19.75, SD = 1.79; 80% female) at a large private university in the US participated in a daily diary study in exchange for course research credit. We collected data from as many participants as possible from the participant pool. Prior to beginning the two-week daily diary study, they attended a live online video information session with one of the researchers to learn about the details of the study and to improve compliance. They completed a trait questionnaire afterwards. On each of the fourteen days, they were sent an email with a link to a questionnaire at 9:00pm. They were instructed to complete the questionnaire just before going to bed. An additional reminder email was sent out the following morning at 7:00am and responses were accepted until 10:00am. After data cleaning, participants completed 1,711 daily reports (M = 12.13, SD = 1.76; minimum completed = 6), indicating good compliance.

Trait Measures

Political orientation was measured in the same way as Study 2 (M = 3.28, SD = 1.57). Religiosity was measured with three items to capture more than church attendance (e.g., Kirkpatrick, Shillito, & Kellas, 1999): “Overall, how important would you say are your religious beliefs or personal faith in your life?” with a 7-point scale (1 = not at all important, 7 = extremely important); “Would you say you have a personal relationship with God?” with options for “yes” or “no”; “How frequently do you attend religious services?” with 7 options (1 = never, 2 = a few times a year, 3 = every other month, 4 = once a month, 5 = a few times a month, 6 = once a week, 7 = several times per week). Each item was standardized and they were averaged together (α = .86).

Daily Measures

Daily meaning in life was assessed with two face valid items taken from the Meaning in Life Questionnaire (Steger et al., 2006) that were reworded to reflect the daily nature of the questionnaire (“How meaningful did you feel your life was today?” and “How much did you feel your life had purpose today?”). Participants responded to each item using a 7-point scale (1 = not at all, 7 = very much).

Daily satisfaction with life was assessed with a single face valid item from the Satisfaction with Life questionnaire (Diener et al., 1985), “How satisfied were you with your life today?” Responses were recorded on a 7-point scale (1 = Very dissatisfied, 7 = Very satisfied).

Affect was assessed by having participants reflect on their day and respond to a series of adjectives regarding how much they felt that day on a 7-point scale (1 = did not feel this way at all, 4 = felt this way moderately, 7 = felt this way very strongly). Positive affect was measured with happy, delighted, excited, enthusiastic, glad, at ease, calm, peaceful, relaxed, and contented. Negative affect was measured with tense, annoyed, stressed, angry, nervous, gloomy, miserable, sad, disappointed, and depressed.

Each of these measures has been used reliably in previous daily diary studies (e.g., Newman, Nezlek, & Thrash, in press; Nezlek, 2005).

Results

To account for both within-person and between-person variation, we built two-level multilevel models in which days were nested within persons as follows:

As shown in Table 2, political conservatives experienced greater daily meaning in life (estimated correlation, r = .18). Political conservatism was centered around the midpoint (political moderates) to facilitate in interpretation. In these models, the intercept represents the mean level of daily meaning in life that a moderate experienced (3.91 on a 1 to 7 scale). Those who were slightly conservative had average scores of 4.06 (3.91 + .15), whereas those who were slightly liberal had average scores of 3.76 (3.91–.15). All other relationships, including daily satisfaction with life, were not significant. The estimated within-person correlation between meaning in life and satisfaction with life was .62. Additionally, we constrained the standardized coefficients and found that the meaning in life relationship was stronger than the positive affect relationship, χ2(1) = 6.38, p = .01, although it was not significantly stronger than the negative affect relationship, χ2(1) = .24, p > .5, or the satisfaction with life relationship, χ2(1) = 2.13, p = .14.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and unstandardized coefficients for the daily measures from Study 3.

| Variance | Intercept | Political conservatism coefficient | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Mean | Reliability | Within | Between | γ00 | γ01 | 95% CI | t-ratio | p | |

| Daily meaning in life | 3.89 | .85 | 1.33 | 1.44 | 3.91 | .15 | [.01, .29] | 2.11 | .04 |

| Daily satisfaction with life | 4.97 | 1.30 | .66 | 4.95 | .05 | [−.05, .15] | < 1 | .36 | |

| Daily positive affect | 3.82 | .88 | .94 | .98 | 3.75 | −.03 | [−.15, .09] | <1 | .65 |

| Daily negative affect | 2.63 | .75 | .82 | .57 | 2.61 | −.07 | [−.17, .03] | 1.43 | .16 |

Note: Satisfaction with life was measured with a single item and therefore has no reliability statistic.

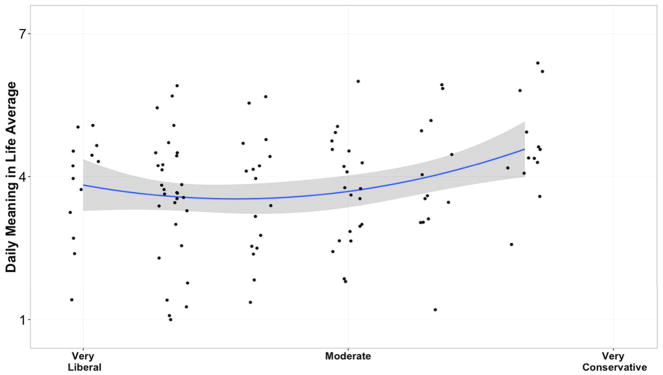

Similar to Study 2, we examined the quadratic effect in an exploratory manner by creating polynomial terms for political orientation. Again, there was a significant quadratic relationship between daily meaning in life and political orientation, γ02 = .11, t-ratio = 2.38, p = .02; (see Figure 2). After controlling for religiosity, this quadratic relationship remained significant, γ02 = .10, t-ratio = 2.32, p = .02.

Figure 2.

Study 3 quadratic relationship between political orientation and average daily meaning in life scores.

Study 4

Method

In Study 4, we moved beyond end-of-the-day reports and examined well-being reports in the moment through reanalysis of Ecological Momentary Assessment data collected by Hofmann et al. (2014) with a large and diverse sample. Participants completed momentary reports about their moral or immoral behaviors, affect, purpose in life, happiness, and stress. Prior to receiving the momentary assessments, participants answered the political orientation question used in Study 2 (M = 3.31, SD = 1.76). Religiosity was assessed with the item, “How religious are you?” on a 7-point scale (1 = not at all 7 = very much; M = 3.00, SD = 2.18). Given that the nature of their study was concerned with moral behaviors, Hofmann and colleagues did not report the relationships between political orientation and momentary well-being.

Participants and procedure

Participants from the US and Canada were recruited from January 2013 until June 2014 through various forms of advertising (Craigslist, Backpage, Facebook, Twitter, various local newspaper ads, blog and forum ads, crowdsurfing pages, and university mailing lists). 1,252 participants (Mage = 31.9, SD = 9.96, 51.8% female) completed 13,240 momentary reports over the course of three days (71% response rate). 73.0% of the participants were Caucasian, 9.0% were Asian, 7.3% were Hispanic/Latino, 5.7% were African American, 0.6% were Native American, and 4.5% were of other backgrounds. In terms of highest level of education, 0.3% had completed some high school, 4.2% completed high school, 35.2% completed some college, 31.1% completed college, and 29.2% had completed advanced/post-graduate studies.

Momentary purpose in life was measured with the item, “Do you feel that your life has a clear sense of purpose at the moment?” Because this item was not administered to all participants, analyses involving the purpose in life question were limited to 911 participants (Mage = 33.05, SD = 9.85; 45.9% female). Stress was measured with the item, “How stressed are you at the moment?” Responses to purpose and stress were recorded on a 7-point scale (0 = not at all, 6 = very much). Happiness was measured with the item, “How happy do you feel at the moment?” and responses were recorded on a 7-point scale (−3 = very unhappy, +3 = very happy).

Positive affect items were grateful, elevated, and proud. Negative affect items were embarrassed, angry, disgusted, contemptuous, guilty, and shameful. Responses were recorded on a 5-point scale (0 = not at all, 4 = very much). Descriptive statistics for these variables are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics from Study 4.

| Between-person variation | Within-person variation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Dependent variable | Reliability | Mean | Between-day | Within-day | |

| Purpose in life | 3.52 | 1.93 | .08 | .67 | |

| Happiness | .94 | .74 | .15 | 1.09 | |

| Stress | 2.33 | 1.35 | .31 | 1.39 | |

| Positive affect | .59 | 1.83 | .50 | .05 | .77 |

| Negative affect | .78 | .60 | .14 | .03 | .43 |

Note: Purpose in life, happiness, and stress were measured with a single item and therefore have no reliability statistics.

Results

We again used multilevel modeling to account for the nested data structure. To account for within-day, between-day, and between-person variation, we used three-level models in which moments were nested within days, and days were nested within people.

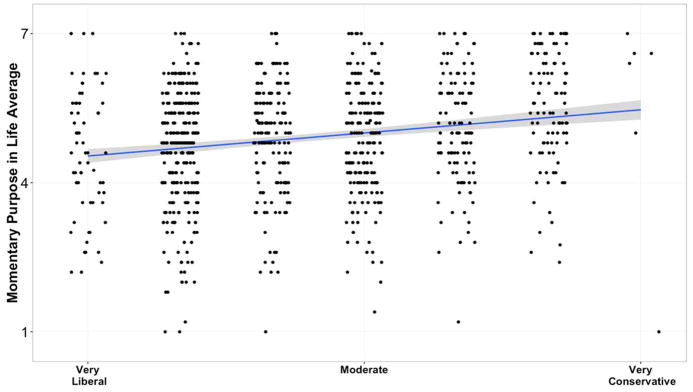

As can be seen in Figure 3, conservatives reported greater momentary purpose in life than liberals (estimated correlation, r = .21). They also reported greater happiness, positive affect, and less stress compared to liberals (See Table 4). The estimated within-person correlation between momentary purpose in life and happiness was .49. Next, we adjusted statistically for religiosity by entering the religiosity measure grand mean centered at level 3. As can be seen in Table 4, the relationship between momentary purpose in life and political orientation remained significant, whereas the coefficients for happiness and positive affect became marginally significant or non-significant, respectively. Stress remained negatively related to political orientation even after adjusting for religiosity.

Figure 3.

Study 4 linear relationship between political orientation and average momentary purpose in life scores.

Table 4.

Unstandardized coefficients from Study 4.

| Without controlling for religiosity | Controlling for religiosity | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||

| Intercept | Political conservatism coefficient | Intercept | Political conservatism | Religiosity | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| Dependent variable | γ00 | γ01 | 95% CI | t-ratio | p | γ00 | γ01 | 95% CI | t-ratio | p | γ02 | t-ratio | p |

| Purpose in life | 3.60 | .16 | [.11, .21] | 5.86 | < .001 | 3.58 | .09 | [.02, .16] | 2.57 | .01 | .09 | 3.32 | .001 |

| Happiness | .98 | .06 | [.03, .10] | 3.76 | < .001 | .96 | .03 | [−.01, .07] | 1.70 | .09 | .04 | 2.69 | < .01 |

| Stress | 2.28 | −.07 | [−.11, −.02] | 3.06 | .002 | 2.26 | −.10 | [−.15, −.05] | 3.75 | < .001 | .05 | 2.21 | .03 |

| Positive affect | 1.87 | .07 | [.04, .09] | 4.62 | < .001 | 1.83 | .00 | [−.03, .04] | < 1 | .87 | .09 | 6.89 | < .001 |

| Negative affect | .61 | .01 | [−.01, .03] | 1.18 | .24 | .60 | −.00 | [−.02, .02] | < 1 | .81 | .02 | 2.20 | .03 |

Following this, we compared the strengths of the standardized coefficients for purpose in life and the other standardized well-being variables without controlling for any other variables. (See Bauer, Preacher, & Gil, 2006 and the supplemental materials for a description of such models.) The strength of the relationship between political orientation and purpose in life was significantly stronger than the strengths of the relationships between political orientation and happiness, χ2(1) = 9.26, p = .003; stress, χ2(1) = 10.18, p = .002; positive affect, χ2(1) = 4.54, p = .03, and negative affect, χ2(1) = 36.04, p < .001. Thus, as in studies 2 and 3, the strength of the relationship between political orientation and meaning/purpose in life exceeded the strength of the relationship between political orientation and other well-being indicators.

We also tested quadratic and cubic relationships between political orientation and momentary purpose in life, but neither were significant (p = .27, p = .31, respectively).

General Discussion

The present set of studies, comprising 5 independent samples across 16 Western countries and 4 decades, establishes that political conservatives report more meaning in life than liberals at all reporting periods (global, daily, and momentary). Even when fine-grained analyses found quadratic relationships, this pattern remained. The relationship was generally robust after adjusting statistically for religiosity, which suggests that there is some unique aspect of political conservativism that provides people with meaning and purpose in life.

In three of the four studies that included multiple well-being measures, the relationship between political orientation and meaning in life was stronger than the relationship between political orientation and satisfaction with life or other well-being measures. Support for this was found by constraining coefficients and by demonstrating that the relationship between political orientation and meaning in life remained significant after adjusting for religiosity, whereas relationships involving other well-being measures were usually no longer significant after adjusting for religiosity. These findings add to a growing body of research suggesting that specific eudaimonic measures of well-being, such as meaning and purpose in life, are distinct from evaluative and experiential measures (e.g., Tov & Lee, 2015).

One exception is worth noting. Although conservatives reported higher meaning in life and higher life satisfaction in all studies, the strength of the relationship between political orientation and meaning in life did not significantly exceed the relationship involving satisfaction with life in Study 1a, based on the European Values Survey. This exception may reflect cultural and historical differences (the data were collected 1981–1984) as well as differences in question wording (the meaning in life measure was negatively-worded in the European Value Survey, but positively worded in Studies 1b – 4).

Given the correlational nature of the present data, any conjectures about why conservatives report more meaning in life than liberals are to be treated with great caution. It is possible and plausible that third variables, such as a child’s upbringing and community expectations, can foster a conservative political orientation as well as more meaning in life. In such cases, mediation analyses, which assume causal relationships (MacKinnon, Krull, & Lockwood, 2000; Preacher, 2015), can be misleading.

This said, our data constrain the range of likely candidate variables. Recall that social conservatism (in form of opposition to abortion and gay marriage) was a better predictor of meaning in life than economic conservatism, whereas the reverse was true for life satisfaction (Study 2). Previous research suggested that the observed link between economic conservatism and life satisfaction can be traced to rationalization of inequality (Napier & Jost, 2008), one of two key components of conservatism (Jost, Glaser, Kruglanski, & Sulloway, 2003). The second component, resistance to change, is more closely related to social conservatism, which involves opposition to cultural changes. This suggests that aspects of resistance to change may contribute to the observed relationship between conservatism and meaning in life. This conjecture is compatible with the observation that conservatism also relates to stability and coherence, situational factors that can increase the subjective experience of meaning in life (Heintzelman, Trent, & King, 2013; Kay, Laurin, Fitzsimons, & Landau, 2014). Future research may fruitfully address these possibilities.

Regarding possible implications, it is important to realize the limitations of the current findings. In terms of variance explained, the effect of political orientation on meaning in life was relatively small (effect sizes ranged from r = .09 to r = .21), consistent with the relationship between political orientation and life satisfaction (summarized in Onraet et al., 2013). However, small effect sizes are a common feature of well-being research and the effect sizes were comparable to the size of the effects of income and subjective health on meaning in life.

In sum, we have examined the relationship between political orientation and well-being by considering a more holistic view of well-being that includes evaluative, experiential, and eudaimonic well-being at various reporting periods. Overall, our findings show that conservatives report more meaning in life than liberals, and this effect is stronger and more robust than the effects previously found for evaluative and experiential well-being.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Wilhelm Hofmann, Daniel Wisneski, Mark Brandt, and Linda Skitka for the permission to reanalyze data reported by Hofmann, Wisneski, Brandt, & Skitka (2014).

This research was supported in part by the Roybal Center to Princeton University Grant P30 AG024928 awarded to Arthur A. Stone and Norbert Schwarz.

Biographies

David B. Newman is a Ph.D. candidate in the Social Psychology department at the University of Southern California.

Norbert Schwarz is a Provost Professor in the Department of Psychology and the Marshall School of Business at the University of Southern California and a co-director of the USC Dornsife Mind and Society Center.

Jesse Graham is the George S. Eccles Professor of Business Ethics & Associate Professor in the Department of Management at the David Eccles School of Business at the University of Utah.

Arthur A. Stone is a Professor of Psychology and the director of the USC Dornsife Center for Self-Report Science at the University of Southern California.

Footnotes

Effect size estimates in multilevel modeling should be interpreted cautiously. Fixed effects and random effects are estimated separately, and the reductions in variance (a measure of effect size) pertain to the random effects. Our interest concerned the fixed effects. Thus, the reduction in variance from the random effects may not be perfectly accurate. Nevertheless, we provide an estimate for basic models throughout. Any additional effect size estimates, particularly those involving multiple predictors, are not reported, as recommended by Nezlek (2012) and Kreft & de Leeuw (1998).

After adding control predictors, the sample size decreased to 12,004 (a 21.6% reduction). This lowered the power and contributed to a marginally significant coefficient.

References

- Bauer DJ, Preacher KJ, Gil KM. Conceptualizing and testing random indirect effects and moderated mediation in multilevel models: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2006;11(2):142–163. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.11.2.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baylor University. The Baylor Religion Survey, Wave II. Waco, TX: Baylor Institute for Studies of Religion; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1985;49(1):71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman S, Johnston C. Understanding the determinants of political ideology: Implications of structural complexity. Political Psychology. 2014;35(3):337–358. [Google Scholar]

- Heintzelman SJ, Trent J, King LA. Encounters with objective coherence and the experience of meaning in life. Psychological Science. 2013;24:991–998. doi: 10.1177/0956797612465878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann W, Wisneski DC, Brandt MJ, Skitka LJ. Morality in everyday life. Science. 2014;345(6202):1340–1343. doi: 10.1126/science.1251560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jost JT, Glaser J, Kruglanski AW, Sulloway F. Political conservatism as motivated social cognition. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:339–375. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.3.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D. Objective happiness. In: Kahneman D, Deiner E, Schwarz N, editors. Well-being: Foundations of hedonic psychology. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 1999. pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Kay AC, Laurin K, Fitzsimons GM, Landau MJ. A functional basis for structure-seeking: Exposure to structure promotes willingness to engage in motivated action. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2014;143:486–491. doi: 10.1037/a0034462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick LA, Shillito DJ, Kellas SL. Loneliness, social support, and perceived relationships with God. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1999;16(4):513–522. doi: 10.1177/0265407599164006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kreft IGG, de Leeuw J. Introducing multilevel modeling. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Krull JL, Lockwood CM. Equivalence of the mediation, confounding and suppression effect. Prevention Science. 2000;1(4):173–181. doi: 10.1023/A:1026595011371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napier JL, Jost JT. Why are conservatives happier than liberals? Psychological Science. 2008;19(6):565–572. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. Subjective well-being: Measuring happiness, suffering, and other dimensions of experience. Panel on measuring subjective well-being in a policy relevant framework. In: Stone AA, Mackie C, editors. Committee on National Statistics, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman DB, Nezlek JB, Thrash TM. The dynamics of searching for meaning and presence of meaning in daily life. Journal of Personality. doi: 10.1111/jopy.12321. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nezlek JB. Distinguishing affective and non-affective reactions to daily events. Journal of Personality. 2005;73(6):1539–1568. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nezlek JB. SAGE library of methods in social and personality psychology. London: Sage; 2012. Diary methods for personality and social psychology. [Google Scholar]

- Nezlek JB, Newman DB, Thrash TM. A daily diary study of relationships between feelings of gratitude and well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2017;12(4):323–332. [Google Scholar]

- Onraet E, Hiel AV, Dhont K. The relationship between right-wing ideological attitudes and psychological well-being. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2013 doi: 10.1177/0146167213478199. 0146167213478199. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Onraet E, Van Assche J, Roets A, Haesevoets T, Van Hiel A. The happiness gap between conservatives and liberals depends on country-level threat: A worldwide multilevel study. Social Psychological and Personality Science. 2017;8(1):11–19. doi: 10.1177/1948550616662125. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ. Advances in mediation analysis: A survey and synthesis of new developments. Annual Review of Psychology. 2015;66(1):825–852. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS, Congdon R. HLM 7 for Windows [Computer software] Skokie, IL: Scientific Software International, Inc; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson MD, Clore GL. Belief and feeling: Evidence for an accessibility model of emotional self-report. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128:934–960. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.6.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, Deci EL. On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology. 2001;52(1):141–166. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlenker BR, Chambers JR, Le BM. Conservatives are happier than liberals, but why? Political ideology, personality, and life satisfaction. Journal of Research in Personality. 2012;46(2):127–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2011.12.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz N. Why researchers should think “real-time”: a cognitive rationale. In: Mehl MR, Conner TS, editors. Handbook of research methods for studying daily life. New York: Guilford; 2012. pp. 22–42. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz N, Kahneman D, Xu J. Global and episodic reports of hedonic experience. In: Belli R, Alwin D, Stafford F, editors. Using calendar and diary methods in life events research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 2009. pp. 157–174. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz N, Strack F. Reports of subjective well-being: Judgmental processes and their methodological implications. In: Kahneman D, Diener E, Schwarz N, editors. Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1999. pp. 61–84. [Google Scholar]

- Stavrova O, Luhmann M. Are conservatives happier than liberals? Not always and not everywhere. Journal of Research in Personality. 2016;63:29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Steger MF, Frazier P. Meaning in life: One link in the chain from religiousness to well-being. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2005;52:574–582. [Google Scholar]

- Steger MF, Frazier P, Oishi S, Kaler M. The meaning in life questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2006;53(1):80–93. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.53.1.80. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe A, Deaton A, Stone AA. Subjective wellbeing, health, and ageing. The Lancet. 2015;385(9968):640–648. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61489-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor P, Funk C, Craighill P. Are we happy yet? Pew Research Center; 2006. Retrieved from http://pewresearch.org/assets/social/pdf/AreWeHappy. [Google Scholar]

- Tov W, Lee HW. A closer look at the hedonics of everyday meaning and satisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2015 doi: 10.1037/pspp0000081. No Pagination Specified. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Will G. Smile if (and only if) you’re conservative. Washington Post. 2006 Retrieved from http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/02/22/AR2006022202012.html.

- Wojcik SP, Hovasapian A, Graham J, Motyl M, Ditto PH. Conservatives report, but liberals display, greater happiness. Science. 2015;347(6227):1243–1246. doi: 10.1126/science.1260817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.