Abstract

Mucormycosis outbreaks have been linked to contaminated linen. We performed fungal cultures on freshly-laundered linens at 15 transplant and cancer hospitals. At 33% of hospitals, the linens were visibly unclean. At 20%, Mucorales were recovered from >10% of linens. Studies are needed to understand the clinical significance of our findings.

Keywords: healthcare linens, microbiologic surveillance, Mucorales, Rhizopus, Syncephalastrum

Mucormycosis is a life-threatening infection by fungi of the order Mucorales, which is associated with mortality rates that exceed 50% [1]. Risk factors include solid organ or stem cell transplantation, neutropenia, diabetic ketoacidosis, iron overload, burns, and trauma. The economic burden of mucormycosis is substantial, with average costs per hospitalization that are almost double those of aspergillosis ($152954 in 2017 US$) [2]. The disease usually occurs sporadically among immunosuppressed hosts in healthcare or community settings [1]. Outbreaks of healthcare-associated mucormycosis (HCM) can be difficult to recognize because it often is unclear whether cases are occurring above background rates at given centers. Nevertheless, HCM outbreaks are increasingly described [3]. Recently, 3 outbreaks were linked to contaminated healthcare linens (HCLs) [4, 5] or laundry carts [6]. The full extent to which HCLs contribute to the burden of HCM is unknown, and may be under-appreciated. Moreover, it is unknown whether contaminated HCLs account for sporadic cases of HCM, which are not typically subjected to epidemiologic investigations.

Microbiologic testing of HCLs is not mandated by government regulations in the United States or other countries, but it is required by certain third-party certification programs for healthcare laundries (http:// hygienicallyclean.org/wp- content/uploads/2017/12/hygienic_trsa_fs_standard.pdf; http:// hygienicallyclean.org/wp- content/uploads/2017/12/hygienic_trsa_fs_standard.pdf). The Textile Rental Services Association (TRSA) administers a voluntary program that certifies US laundries as providing “hygienically clean” HCLs, which are defined as “free of pathogens in sufficient numbers to cause human illness” (http://hygienicallyclean.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/hygienic_trsa_fs_standard.pdf). There are no scientifically validated definitions of what constitutes “sufficient numbers,” nor is there agreement about which pathogens pose the greatest risk to vulnerable hospitalized patients. Similar microbiologic standards are used by healthcare laundry certification programs in Australia and Europe (http://www.waeschereien.de/media/downloads/GG%20Imagebroschure%20RALGZ%20992-2%20EN.pdf). The objective of this study was to determine the extent to which freshly-laundered HCLs delivered to US transplant and cancer centers are contaminated with Mucorales.

METHODS

A dedicated team (A. J. S., C. J. C., M. H. N.) met HCL delivery trucks at each hospital and immediately performed HCL contact culturing using Replicate Organism Detection and Counting agar plates (25 cm2) with malt extract, lecithin, and Tween 80 (Supplementary Methods). TRSA and German certification standards that use US Pharmacopeia 61 and RAL-GZ-992/2 methods were adapted to define HCL from a laundry as hygienically clean if there was no growth of Mucorales on >90% of items (http://hygienicallyclean.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/hygienic_trsa_fs_standard.pdf; http://www.waeschereien.de/media/downloads/GG%20Imagebroschure%20RALGZ%20992-2%20EN.pdf).

RESULTS

A microbiologic surveillance study was conducted between 25 May 2017 and 29 December 2017 at 15 transplant and cancer hospitals that were drawn largely from the Transplant Associated Infection Surveillance Network [7]. There were hospitals located in each continental US time zone. Visual inspections revealed that HCL and laundry carts were unclean upon arrival at 33% (5/15) and 20% (3/15) of hospitals, respectively, with evidence of hair, lint, insects, or other soilage (Supplementary Figure).

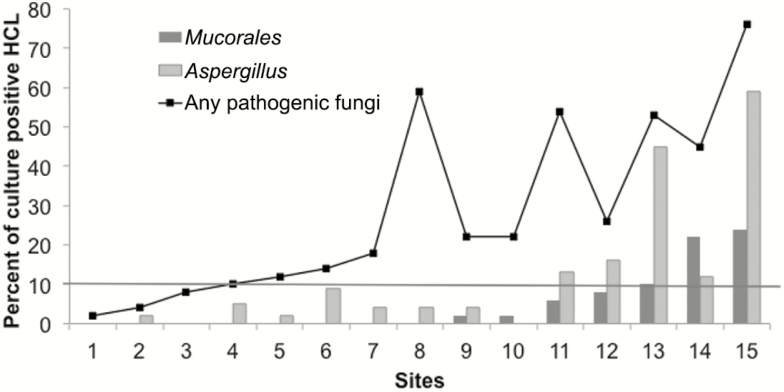

Microbiologic testing results for Mucorales, Aspergillus, and other pathogenic molds are summarized in Figure 1. Freshly-laundered HCLs were contaminated with Mucorales upon arrival at 47% (7/15) of hospitals. HCLs were not hygienically clean for Mucorales at 20% (3/15) of hospitals, based on the failure to attain a >90% culture negativity threshold. At individual centers, 0% to 24% (12/49) of HCLs were culture-positive for Mucorales. Visibly-soiled HCLs or carts and higher maximum temperatures and relative humidities in the vicinity of a laundry were significantly associated with Mucorales-contaminated HCLs (Supplementary Table).

Figure 1.

Percentages of healthcare linens (HCLs) that were culture positive for Mucorales, Aspergillus, and other pathogenic molds. Culture results by hospital. Percentages of HCLs that were culture positive for Mucorales, Aspergillus, and any pathogenic mold (defined as Mucorales, Aspergillus spp., Fusarium, and dematiaceous molds) are shown (y-axis). Centers are ordered on the x-axis by the ascending percentage of HCL contaminated with Mucorales. The threshold for defining hygienically-clean HCL was 10%, which was exceeded for Mucorales at 15% (3/20) of hospitals (indicated by the horizontal line). Mucorales were recovered from HCL at 47% (7/15) of hospitals and from 5% (37/745) of all HCLs. Mucorales included Rhizopus spp. (R. stolonifer, R. oryzae, and R. microsporus) and Syncephalastrum. In addition to Mucorales, pathogenic molds included Aspergillus (12%, 87/745), dematiaceous molds (11%, 82/745), and Fusarium (3%, 22/745). There were 26% (192/745) of HCLs that grew other molds of low pathogenic potential, including sterile mycelium (7%, 55/745) and Penicillium (3%, 23/745). Abbreviation: HCL, healthcare linen.

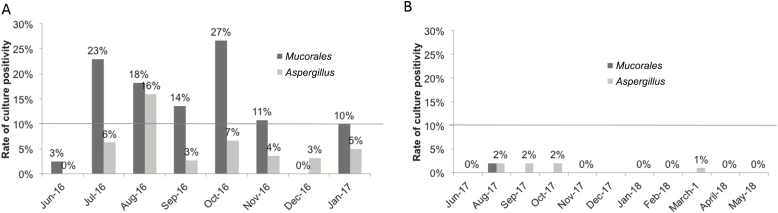

Longitudinal microbiologic testing was performed to evaluate the variability of Mucorales contamination of HCLs at 1 hospital (Figure 2). Between June 2016 and January 2017, freshly-laundered HCLs did not meet the hygienically-clean standard for Mucorales on 75% (6/8) of sampling dates. A median of 14% (range: 3–27%) of HCLs were contaminated with Mucorales. These data were shared with the laundry, which enacted environmental remediation between February and May 2017. Cleaning of HCL carts and lint control measures were the major steps undertaken. HCLs were hygienically clean for Mucorales on all post-remediation dates of microbiologic testing between June 2017 and January 2018. No Mucorales were recovered on 83% (5/6) of sampling dates; on 1 occasion, 2% (1/49) of HCLs were culture-positive for Mucorales.

Figure 2.

Percentages of healthcare linens (HCLs) that were culture positive for Mucorales, Aspergillus, and other pathogenic molds during a longitudinal study at 1 hospital. Monthly testing was performed over 2 time periods: A, June 2016–January 2017 and B, June 2017–January 2018. No sampling was performed in July or December 2017. Culture data from the first time period were shared with the off-site laundry, which performed environmental remediation between February and May 2017. The hospital was also included in the multicenter study (represented as Center 3 in Figure 1), using data from June 2017. The horizontal line represents the 10% culture positivity cut-off to define HCL as hygienically clean.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to measure the Mucorales contamination of freshly-laundered HCLs delivered to US hospitals. HCLs were contaminated with Mucorales upon arrival at 47% of transplant and cancer hospitals, and failed to achieve hygienically-clean standards for Mucorales at 20% of centers. Mucorales were recovered from as many as 24% of HCLs at individual hospitals. Visibly-soiled HCLs or carts, which were observed at 40% (6/15) of hospitals, were significantly associated with Mucorales contamination. These findings are concerning since several HCM outbreak investigations have linked cases to contaminated HCLs. Given our data, infection prevention (IP) programs should be aware that HCLs supplied to their hospitals may be contaminated with Mucorales. At the least, periodic visual inspections of HCLs and carts for general cleanliness are warranted. Based on the local epidemiology of mucormycosis and the populations at risk, programs can decide whether to incorporate microbiologic surveillance of HCLs and possible remediation into their IP practices. In the larger context, engaged clinicians, IP practitioners, hospital administrators, laundry industry professionals, and public health officials should collaborate in developing reasonable standards for producing, testing, and certifying hygienically-clean HCLs that balance patient safety, workflow considerations, and costs.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s guidelines for hospital environmental IP recognize that contaminated fabrics and textiles “can be a source of substantial numbers of pathogenic microorganisms,” but conclude that “the overall risk of disease transmission during the laundry process likely is negligible” (https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/pdf/guidelines/environmental-guidelines.pdf; http://hygienicallyclean.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/hygienic_trsa_fs_standard.pdf). At present, routine microbiologic testing of HCLs at laundries or in hospitals is not mandated in the United States or recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. However, hospitals regularly employ other strategies to reduce the exposure of immunosuppressed patients (in particular, those with neutropenia following chemotherapy or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation) to opportunistic fungi and bacteria, including the use of positive-pressure rooms, high-efficiency particulate air filtering, low-microbial food and beverages, protective isolation, restrictions on plants, and antimicrobial prophylaxis (https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/pdf/guidelines/environmental-guidelines.pdf). In many instances, there is no conclusive evidence of any benefit for these practices [8]. Since hospitalized patients are in close and constant contact with HCL, it is worth considering whether protocols that minimize the exposure of high-risk hosts to items contaminated with Mucorales or other potential pathogens are justified.

There is sound rationale for including microbiologic culturing of HCL in quality control and IP protocols, despite the lack of conclusive data on the dangers posed by contaminated items. First, it is clear that direct inoculation or aerosolization of Mucorales spores from contaminated HCLs can result in cutaneous, pulmonary, or systemic mucormycosis [4, 5]. Likewise, HCL-associated bacteria such as Bacillus cereus are well-recognized to cause outbreaks of nosocomial infections [9]. Second, the trend for third-party certification of healthcare laundries internationally is to require periodic microbiologic testing of linens by independent labs (http://hygienicallyclean.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/hygienic_trsa_fs_standard.pdf). Third, infectious inocula of Mucorales in vulnerable patients are not defined, but they are likely low based on studies of immunosuppressed mice [10]. Finally, our longitudinal study suggests that microbiologic surveillance and environmental remediation strategies may diminish Mucorales contamination during laundering and delivery of HCL. It is important to acknowledge that we cannot conclude definitively that the reduced contamination observed here resulted from remediation efforts, rather than reflecting a natural variation in the burdens of environmental molds. Indeed, better understanding of the factors that account for variations in environmental mold burdens would allow laundries and hospitals to focus on the periods of greatest risk for contamination and cases of mucormycosis. Meteorologic factors associated with the presence of Mucorales-contaminated HCL were higher maximum temperatures and relative humidities at the laundry agencies. In a recent study, seasonal variations in mucormysosis at a cancer center correlated with temperatures [11].

Our study has several limitations. First, it was not designed to assess HCLs for the acquisition of Mucorales within hospitals. Second, this was a descriptive microbiologic study of HCL contamination by molds, and we do not have epidemiologic or clinical data on mucormycosis or other fungal infections at the participating hospitals. Third, we did not culture HCLs for bacteria. Finally, the significance of our finding that HCLs were contaminated with Aspergillus or not hygienically clean for Aspergillus upon arrival at 73% and 33% of hospitals, respectively, is unclear. Transmission of Aspergillus or other non-Mucorales pathogenic molds from HCLs to patients has not been documented. However, a microbiologic surveillance study of bed pillows found a substantial load of many fungal species, in particular Aspergillus, which was postulated to present a potential health risk [12].

In conclusion, we have shown that freshly-laundered HCLs delivered to many United States transplant and cancer centers were contaminated with Mucorales and other pathogenic molds. Follow-up studies are indicated to understand the significance of our findings and to determine whether standardized microbiologic surveillance and remediation strategies are needed. Other priorities include developing practical and efficient microbiologic testing methods, criteria for interpreting culture results, and reasonable performance standards at laundries and in hospitals. It will be impossible to eliminate infections due to opportunistic environmental pathogens among the increasing populations of highly-immunosuppressed hosts. Rather, the objective for parties with a stake in this area is to work collaboratively to establish rational approaches to risk mitigation that optimize patient safety.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Financial support. This work was supported by an unrestricted research grant to M. H. N. from the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

Potential conflicts of interest. J. P. reports grants and personal fees from Astellas; grants, personal fees, and other support from Merck; personal fees and other support from F-2G, Cidara, Scynexis, and Viamet; and grants and other support from Amplyx during the conduct of the study. J. R. W. reports personal fees from Astellas, Merck, Shire, Fate, Pluristem, and Celgene outside the submitted work. S. G. R. reports grants from Gilead, Merck, Astellas, and Cidara; royalties from Elsevier; and travel expenses paid by Wayne State University. L. A. reports personal fees from Merck Sharp & Dohme Brazil, Achaogen, and Pfizer Latin America outside the submitted work. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Roden MM, Zaoutis TE, Buchanan WL, et al. . Epidemiology and outcome of zygomycosis: a review of 929 reported cases. Clin Infect Dis 2005; 41:634–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kontoyiannis DP, Yang H, Song J, et al. . Prevalence, clinical and economic burden of mucormycosis-related hospitalizations in the United States: a retrospective study. BMC Infect Dis 2016; 16:730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Davoudi S, Graviss LS, Kontoyiannis DP. Healthcare-associated outbreaks due to Mucorales and other uncommon fungi. Eur J Clin Invest 2015; 45:767–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Duffy J, Harris J, Gade L, et al. . Mucormycosis outbreak associated with hospital linens. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2014; 33:472–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cheng VCC, Chen JHK, Wong SCY, et al. . Hospital outbreak of pulmonary and cutaneous zygomycosis due to contaminated linen items from substandard laundry. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 62:714–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Teal LJ, Schultz KM, Weber DJ, et al. . Invasive cutaneous rhizopus infections in an immunocompromised patient population associated with hospital laundry carts. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2016; 37:1251–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pappas PG, Alexander BD, Andes DR, et al. . Invasive fungal infections among organ transplant recipients: results of the Transplant-Associated Infection Surveillance Network (TRANSNET). Clin Infect Dis 2010; 50:1101–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fenelon LE. Protective isolation: who needs it?J Hosp Infect 1995; 30(Suppl):218–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cheng VCC, Chen JHK, Leung SSM, et al. . Seasonal outbreak of bacillus bacteremia associated with contaminated linen in Hong Kong. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 64:91–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lamaris GA, Ben-Ami R, Lewis RE, Chamilos G, Samonis G, Kontoyiannis DP. Increased virulence of Zygomycetes organisms following exposure to voriconazole: a study involving fly and murine models of zygomycosis. J Infect Dis 2009; 199:1399–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sivagnanam S, Sengupta DJ, Hoogestraat D, et al. . Seasonal clustering of sinopulmonary mucormycosis in patients with hematologic malignancies at a large comprehensive cancer center. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2017; 6:123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Woodcock AA, Steel N, Moore CB, Howard SJ, Custovic A, Denning DW. Fungal contamination of bedding. Allergy 2006; 61:140–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.