Abstract

Significance: High-mobility group protein box 1 (HMGB1), a ubiquitous nuclear protein, regulates chromatin structure and modulates the expression of many genes involved in the pathogenesis of lung cancer and many other lung diseases, including those that regulate cell cycle control, cell death, and DNA replication and repair. Extracellular HMGB1, whether passively released or actively secreted, is a danger signal that elicits proinflammatory responses, impairs macrophage phagocytosis and efferocytosis, and alters vascular remodeling. This can result in excessive pulmonary inflammation and compromised host defense against lung infections, causing a deleterious feedback cycle.

Recent Advances: HMGB1 has been identified as a biomarker and mediator of the pathogenesis of numerous lung disorders. In addition, post-translational modifications of HMGB1, including acetylation, phosphorylation, and oxidation, have been postulated to affect its localization and physiological and pathophysiological effects, such as the initiation and progression of lung diseases.

Critical Issues: The molecular mechanisms underlying how HMGB1 drives the pathogenesis of different lung diseases and novel therapeutic approaches targeting HMGB1 remain to be elucidated.

Future Directions: Additional research is needed to identify the roles and functions of modified HMGB1 produced by different post-translational modifications and their significance in the pathogenesis of lung diseases. Such studies will provide information for novel approaches targeting HMGB1 as a treatment for lung diseases.

Keywords: HMGB1, inflammatory lung injury, pulmonary infection, pulmonary vascular remodeling, fibrosis, cancer

Introduction

High-mobility group protein box 1 (HMGB1) was first identified in 1973 as a nonhistone chromosomal nuclear protein (107). It was isolated from calf thymus chromatin and was categorized as a “high-mobility group” protein by its defining characteristic of rapid migration in polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis systems, without any signs of aggregation (107). In 1999, it was reported that extracellular HMGB1 was significantly increased in animal models of sepsis and in septic patients (336). Circulating HMGB1 can produce significant proinflammatory effects and cause lethal sepsis shock (336, 337). Over the last two decades, HMGB1 has been described as a damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMP) molecule or an alarmin that plays a role in the pathogenesis of an increasing number of diseases, including, but not limited to, sepsis, autoimmune diseases, cancer, liver diseases, and lung diseases (69, 145, 218, 262).

A number of reviews have been published in this journal that have discussed the (i) post-translational modifications of HMGB1 that occur during inflammatory responses; (ii) role of HMGB1 receptors in oxidative and inflammatory tissue injury; (iii) the involvement of HMGB1 in cardiovascular diseases, including pulmonary hypertension; and (iv) targeting HMGB1 for the treatment of various metabolic disorders resulting from sterile inflammation (44, 96, 289). In this review, we focus on recent studies regarding the potential cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying the roles of HMGB1, especially in the pathogenesis of lung diseases where it could represent a biomarker for disease prognosis and a target for therapeutic strategies in treating lung diseases.

HMGB1 Structure and Its Function in the Nucleus

HMGB1 is a 215 amino acid nuclear protein, weighing 25 kDa (123a). The gene that encodes for HMGB1 is located on chromosome 13q12.3 and was sequenced in 1996 (91). The primary structure of HMGB1 is well conserved across species and shares high sequence homology among species such as yeast, Drosophila, Chironomidae, bacteria, plants, and fish (101, 175, 282, 331, 347, 351, 354). Furthermore, mouse and rat HMGB1 shares 100% homology, while human and rodent HMGB1 has 99% homology (45, 91, 98, 271, 344).

The binding of nuclear HMGB1 in the minor groove of DNA can facilitate DNA bending, producing higher transcription factor activity, DNA repair, and remodeling of the chromatin (34, 208, 250, 264). As illustrated in Figure 1, HMGB1 binds to DNA via two unique binding domains, the A-box (amino acid residues 9–79) and the B-box (amino acid residues 95–163), which share high sequence similarity with each other (11, 32). The A-Box and B-Box are separated by a short interlinking peptide sequence (32, 264, 265). The C-terminal of HMGB1 (amino acid residues 186–215) is composed of a highly acidic tail containing aspartic and glutamic acid residues (22, 34). The acidic C-terminal tail of HMGB1, which is not required for binding, regulates its effects on transcriptional activity, as it is required for DNA bending (119, 300, 332). The C-terminal plays an essential role in the binding of protein p53 to DNA to regulate cell cycle and death pathways (6, 22).

FIG. 1.

The structure and function determining sequence of HMGB1. Human HMGB1 is a protein with 215 amino acids, encoded by the gene located at chromosome 13q12.3. HMGB1 contains two DNA-binding domains: the A Box (amino acids 9–79) and B-Box (amino acids 95–163), and a C-terminal tail (amino acids 186–215), which is involved in promoting the interaction of A and B box with DNA. HMGB1 contains two NLS, which are located at amino acids 28–44 (NLS1) and 179–185 (NLS2), responsible for the nuclear localization of HMGB1 and for regulating HMGB1's translocation between the nucleus and the cytoplasm on post-translational modifications, such as phosphorylation and acetylation. There are three critical cysteines (C23, C45, and C106) subject to redox modifications, which determine whether HMGB1 functions as a cytokine, a chemokine, or an inactive protein. HMGB1 also has a heparin binding site (amino acids 6–12), a TLR4 binding site (amino acids 89–108), and an RAGE binding site (amino acids 150–183). HMGB1, high-mobility group protein box 1; NLS, nuclear localization signals; RAGE, receptor for advanced glycation end products; TLR, toll-like receptor.

HMGB1 Localization and Lung Diseases

Wang et al. reported in 1999 that treatment of cultured macrophages with endotoxin lipopolysaccharide (LPS) caused a significant release of nuclear HMGB1 into cell culture media. They further demonstrated that extracellular HMGB1 in the serum of subjects with sepsis can act as a late mediator of inflammation for septic shock mice (336). Since then, excessive accumulation of extracellular HMGB1, especially airway and sputum HMGB1, has been reported in many studies of a variety of lung diseases, such as cystic fibrosis (CF), asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), acute lung injury (ALI), acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, pneumonia, tuberculosis (TB), pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), and lung cancer (Table 1). Thus, blocking the accumulation of extracellular HMGB1 has been postulated in the treatment of these disorders.

Table 1.

Levels and Modifications of High-Mobility Group Protein Box 1 in Biological Samples in Lung Diseases

| Lung disease | Sample (origin) | Fold increase compared to control | HMGB1 modification | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asthma | Sputum | 5 | Reduced and disulfide | (71) |

| COPD | Sputum | 37 | — | (128) |

| Plasma | 3.83 | — | (128) | |

| Serum | 4.0 | — | (366) | |

| ALI/ARDS | BAL | 10–17 | Oxidized, reduced, and disulfide | (377) |

| PF | Serum | 1.97–5.66 | — | (296) |

| CF | Serum | 5.11 | — | (57) |

| Sputum | 4.64 | |||

| BAL | 20.11 | — | (86) | |

| Pneumonia | BAL | 4 | — | (378) |

| TB | Plasma | 1.68 | — | (368) |

| Sputum | 1.82 | — | (368) | |

| Lung cancer | Serum | 1.8–8.2 | — | (343) |

| PAH | Serum | 2.47 | — | (366) |

ALI, acute lung injury; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage; CF, cystic fibrosis; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HMGB1, high-mobility group protein box 1; PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension; PF, pulmonary fibrosis; TB, tuberculosis.

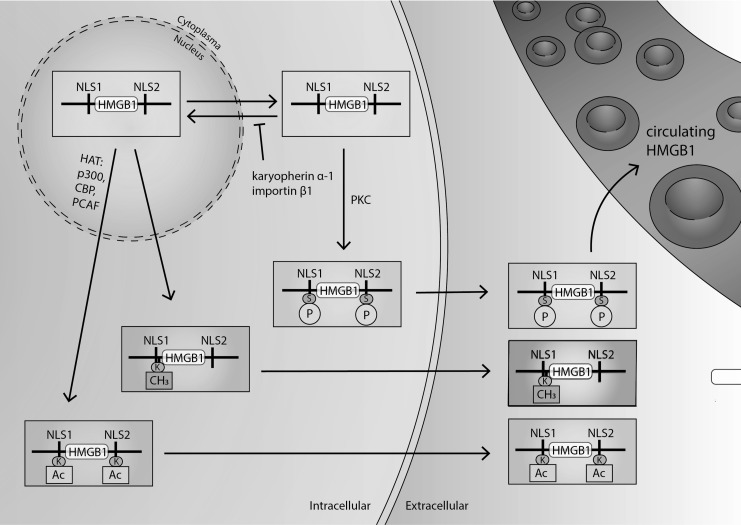

Under normal physiological conditions, HMGB1 is localized in the nucleus, due to its two nuclear localization signals (NLS), located at amino acids 28–44 (NLS1) and 179–185 (NLS2) (Fig. 2) (138, 253, 278). However, HMGB1 can be readily shuttled between the nucleus and the cytoplasm by modifications of NLS1 and NLS2 via acetylation and deacetylation (Fig. 2) (138, 280, 363). Acetylation and deacetylation of HMGB1 are mediated by histone acetyltransferase (HAT) family proteins and histone deacetylase, thus regulating its translocation between the nucleus and the cytoplasm (37, 201, 363).

FIG. 2.

Regulation of HMGB1 localization. HMGB1 is a nuclear nonhistone binding protein that can shuttle between the nucleus and the cytosol through nuclear pores. HMGB1 contains two nuclear localization sequences (NSL1 and NLS2). These NLS are post-translationally modified by hyperacetylating lysine residues within NLS1 and NLS2. Hyperacetylation of NLS by HAT (p300, PCAF, CBP) is required to induce nucleocytoplasmic translocation. Also, the phosphorylation of cytoplasmic HMGB1 by PKC can cause HMGB1 to bind with karyopherin-α-1 and importin-β-1, which can block its nuclear import, keeping it in the cytoplasm. In addition, the methylation of lysine-42 at NLS1 alters HMGB1 conformation, which can result in its decreased ability to bind with DNA and causing HMGB1's passive diffusion to the cytoplasm. Under conditions of oxidative stress, HMGB1 translocates from the nucleus to the cytoplasm through nuclear export factor 1 (CRM1). Cytoplasmic HMGB1 can then be secreted from the cell in secretory vesicle-mediated exocytosis. Alternatively, HMGB1 can be passively secreted from injured or necrotic cells. Whether passively or actively secreted, HMGB1 then can accumulate in extracellular spaces such as the airways and circulating blood. Extracellular HMGB1 also is subjected to redox modifications of three critical cysteine residues (C23, C45, and C106). When HMGB1 fully reduces it can function as a cytokine and when HMGB1 is oxidized it forms a disulfide bond between C23 and C45, which imparts chemokine and cytokine activity. HMGB1 can be terminally oxidized (sulfonic acid) at all three cysteines, which inactivates all activity. CRM1, chromosome region maintenance 1; HAT, histone acetyltransferase; PCAF, p300/CBP-associated factor; PKC, protein kinase C.

Under cellular stress, the translocation of HMGB1 from the nucleus to the cytoplasm can be favored by post-translational modifications of nuclear HMGB1, such as hyperacetylation, phosphorylation, methylation, and oxidation (37, 68, 99, 139, 166, 238, 314). The accumulation of HMGB1 in the cytoplasm can lead to active HMGB1 release from cells into the extracellular milieu by secretory lysosomes (37, 97, 238).

The translocation of HMGB1 from the nucleus to the cytoplasm was first shown in HMGB1 with hyperacetylated lysine residues in NLS1 and NLS2 (37, 201, 363). It was found that the acetylation of HMGB1 is primarily regulated by the HAT family protein p300/CBP and p300/CBP-associated factor (PCAF) (37, 362). In addition, under oxidative conditions, HMGB1 can form a complex with chromosome region maintenance 1 (CRM1), a nuclear export factor (NEF), and is readily translocated to the cytoplasm on acetylation (314). Hyperacetylated HMGB1 was found in cells or animals subjected to oxidative stress under conditions of exposure to hyperoxia or proinflammatory stimuli (66, 301).

Interestingly, it was recently discovered that oxidation of the critical cysteine residues of HMGB1 (Fig. 1) can directly affect its subcellular location (166). HMGB1 has three critical cysteine residues at amino acids C23, C45, and C106 (Fig. 1). Intracellular HMGB1 is present in the fully reduced state (85). In a recent study, Kwak et al. demonstrated that hydrogen peroxide generated in macrophages on exposure to LPS can facilitate the intramolecular disulfide formation between cysteines C23 and C45. Such oxidation of HMGB1 cysteines can stimulate its nucleocytoplasmic translocation and release from macrophages (166).

In addition to NLS acetylation-dependent subcellular localization, the phosphorylation of serine residues of NLS1 and NLS2 is another modification that regulates the shuttling of HMGB1 from the nucleus to the cytoplasm (99, 363). The phosphorylation of specific serine residues in HMGB1 is mediated by protein kinase C (PKC). Compounds that are specific PKC inhibitors (i.e., okadaic acid and baicalein) can cause a concentration-dependent reduction in HMGB1 phosphorylation (363), whereas activators of PKC (e.g., 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate [PMA] and bryostatin-1) increase HMGB1 phosphorylation and its secretion (238). On phosphorylation, HMGB1 can bind to karyopherin-α1, a member of the importin-α family, which induces the sequestration of HMGB1 in the cytoplasm by blocking its translocation to the nucleus (Fig. 2) (363).

Nuclear HMGB1 can also be methylated at Lys42, which can alter HMGB1 protein conformation, decreasing HMGB1-DNA binding activity (139, 349). Decreased binding of HMGB1 to DNA increases its passive diffusion out of the nucleus and into the cytoplasm (139, 149, 280). This has been reported in neutrophils under chronic inflammatory conditions (139). Moreover, the secretion of HMGB1 from macrophages can be facilitated when HMGB1 is poly(ADP-ribosyl)ated, a post-translational modification produced by poly(ADP)-ribose polymerase (PARP)-1 (68, 360).

In summary, many post-translational modifications regulate HMGB1's translocation from the nucleus to the cytoplasm and the subsequent active release from cells (Fig. 2) (37, 68, 99, 139, 238, 314). Because of the critical role of extracellular HMGB1 in the pathogenesis of numerous lung diseases, blocking the release of HMGB1 has been postulated for therapeutic approaches. In fact, inhibiting PARP-1, either genetically or pharmacologically, has been shown to effectively attenuate LPS-stimulated HMGB1 release, suggesting its therapeutic application in treating lung disorders caused by bacterial infections (68). Other studies have shown that ascorbic acid and GTS-21, a partial agonist of α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, can effectively attenuate ALI and enhance host defense against pulmonary infections by inhibiting HMGB1 hyperacetylation (247, 301). These studies are discussed further in this review.

HMGB1 can also be passively released by leaking necrotic cells, a process that can induce inflammation (37, 280). Interestingly, HMGB1 is not easily released by cells undergoing apoptosis due to its high affinity to chromatin and the low levels of NLS acetylation (280). The significant difference in HMGB1-induced clinical outcomes, by HMGB1 released from cells undergoing either necrosis or apoptosis, was elegantly demonstrated in a recent study by Rafikov et al. (258). In this study, the authors show that HMGB1 released from necrotic cells was in a reduced redox status, exhibiting a more potent and sustained inflammatory ability than HMGB1 released from apoptotic cells. The redox regulation of HMGB1 activities is further discussed in this review.

HMGB1 Signaling in Pathophysiology of Lung Diseases

Extracellular HMGB1, as a DAMP through similar pathways, can play a critical role in activating signaling pathways leading to inflammatory responses, vascular remodeling, and fibrotic progression in several lung diseases. Figure 3 illustrates these HMGB1-elicited signaling events mediated by HMGB1 receptors.

FIG. 3.

The role of HMGB1 in the pathogenesis of lung diseases. In the studies reviewed in this article, elevated extracellular HMGB1, whether it is in the airways, serum, or other extracellular milieu, can signal as a DAMP through similar pathways that lead to the pathogenesis of different lung diseases. The binding of extracellular HMGB1 to its receptors, such as TLR2, TLR4, TLR9, and RAGE, can initiate innate immune responses by increasing NF-κB and MAPK activities. The activation of NF-κB is responsible for the increased secretion of numerous proinflammatory mediators, including the active release of HMGB1 into the airways. Proinflammatory mediators can induce the infiltration of leukocytes into the lungs and airways, leading to lung inflammation. This further causes an elevation in the levels of proteases and ROS, which feeds back and contributes to increased NF-κB activity. A significant elevation in ROS can damage and cause dysfunction, injury, and death to lung cells, including macrophages and endothelial and epithelial cells. Both ROS and extracellular HMGB1 can directly disrupt epithelial and endothelial intercellular tight junctions, reduce their barrier integrity, and result in increased alveolar permeability. Macrophage injury reduces efferocytosis, which contributes to the higher leukocyte counts, as well as impairs the phagocytosis of invading bacteria, resulting in increased susceptibility to infections. Pulmonary infections and damage to the lung cells further increase the accumulation of extracellular HMGB1, establishing a negative feedback cycle. In addition, the binding of HMGB1 to RAGE receptors increases MAPK activity, altering cell proliferation and inducing vascular remodeling. Overall, HMGB1-induced inflammatory lung cell damage, in combination with vascular remodeling, can significantly compromise lung functions and cause lung diseases. DAMP, damage-associated molecular pattern; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; NF-κβ, nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

Extracellular HMGB1 can function as a DAMP molecule that can activate immune cells via the pattern recognition receptors, including toll-like receptors (TLRs), TLR2, TLR4, TLR9, and receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE). The binding of HMGB1 to these cell surface receptors can elicit inflammatory responses by activating nuclear factor kappa light-chain enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)/c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK)/p38 pathways (Fig. 3) (56, 117, 193, 239, 334, 366). It has been shown that extracellular HMGB1 has high affinity for the TLR2, TLR4, and RAGE, on pneumocytes and leukocytes (137, 245).

Binding of extracellular HMGB1 to TLR2/4/9 receptors can activate the canonical pathway of NF-κB. Following the activation of TLR2 and TLR4 receptors, the phosphorylation of the inhibitory IκB-α protein by IκB kinase (IKK) causes the NF-κB subunit complex (p65 [NF-kappa-B p65 subunit/transcription factor p65] and p50) to translocate to the nucleus after p65 phosphorylation (17, 18, 58, 169, 170). On entering the nucleus, NF-κB upregulates the expression of more than 150 proteins (41, 195, 292). On HMGB1 binding to RAGE, it can activate the MAPK pathway to phosphorylate extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and p38, which also can activate NF-κB (188).

HMGB1-induced activation of canonical NF-κB pathways can induce the synthesis secretion and secretion of proinflammatory mediators, including interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-8, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interferon (IFN)-γ, and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), which are involved in the recruitment of leukocytes and lymphocytes to the lung, and contribute to furthering lung inflammation (56, 59, 67, 106, 114, 334). The chemokine activity of HMGB1 was revealed following the pharmacological inhibition of α-chemokine receptors, which resulted in the attenuation of the HMGB1-induced increase in airway levels of infiltrated neutrophils, subsequent lung injury, or even death of the animals (192).

During pulmonary bacterial infection, pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP) molecules, including bacterial components such as LPS, peptidoglycan, and lipoteichoic acid, can activate airway cells, including alveolar macrophages and epithelial cells, through surface receptor PRRs, TLR2, TLR4, TLR9, and RAGE (324, 376). The activation of these receptors can increase HMGB1 expression and induce the translocation and release of HMGB1 into the extracellular milieu (338, 376). Together, PAMPs and HMGB1 can cause synergetic effects on activating immune cells, producing exacerbated inflammatory lung injury (8, 130, 256). The binding of HMGB1 to RAGE, TLR2, and TLR9 receptors has been shown to increase the production of chemokines and cytokines that are critical in the host defense against TB, demonstrated in TB-infected TLR2 and TLR9 knockout mice and TLR2/9 double knockout mice (95, 116).

Although inflammation is essential for host defense against pulmonary infection, activated leukocytes in the lung can release myeloperoxidase (MPO), matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9), proteases, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) (52, 270, 272). In addition, neutrophils undergoing cell death release various DAMPs (e.g., HMGB1, chemokine ligand 8 [CXCL8], IL-8, TNF-α, and IL-1β). When airway epithelial cells are exposed to these DAMPs, epithelial cells can release the potent chemotactic protein, CXCL8 (120, 205). CXCL8 can increase the infiltration of more neutrophils, thereby augmenting neutrophil-induced damage (120, 163, 205, 281). It has been reported that in epithelial cells exposed to necrotic neutrophil DAMPs, the pharmacological inhibition of TLR2, TLR4, and RAGE can significantly decrease CXCL8 levels (120).

The activation of HMGB1-mediated RAGE can compromise endothelial cell/cell junctions and increase endothelial barrier permeability (287, 348). The binding of HMGB1 to RAGE primarily activates the MAPK/p38 pathway (87, 160, 348). One of the downstream targets of MAPK/p38 activation catalyzes the phosphorylation of heat shock protein 27 (Hsp27), an actin binding protein (145, 313, 348). The phosphorylation of Hsp27 produces actin stress fiber formation, actin cytoskeletal disorganization, and cell/cell junction dissociation (108, 148, 348). These changes increase the permeability of endothelial cells, which contributes to decreased lung function (348).

The increase in ROS levels and extracellular HMGB1 can directly disrupt epithelial and endothelial intercellular tight junctions, damage alveolar architecture, and stimulate further upregulation of proinflammatory mediators and the release of HMGB1 into the airways, establishing a vicious feedback loop (156, 204). Thus, neutrophil-derived ROS and protease secretion can promote cell injury and death, disrupting the distribution of junction proteins, resulting in the loss of epithelial/endothelial barrier integrity, which contributes to poorer lung function, airway obstruction, and the progression of many lung diseases, including COPD, ALI/ARDS, PAH, and pneumonia (1, 103, 131, 302, 366).

In addition, extracellular HMGB1 can directly induce macrophage injury, causing reduced efferocytosis, which contributes to an increased number of leukocytes, and impairing the phagocytosis of invading bacteria, resulting in increased susceptibility to infections (86, 194, 248). Pulmonary infections and resulting damage to lung cells can further increase the accumulation of extracellular HMGB1, establishing a positive feedback cycle. Moreover, HMGB1 has been reported to mediate the recruitment of inflammatory cells in subjects with asthma, thereby exacerbating oxidative stress-mediated asthma pathology (126, 206). Therefore, blocking HMGB1 activities using neutralizing anti-HMGB1 antibodies could effectively enhance host defense against bacterial infections and attenuate lung injuries, as demonstrated in mouse models of ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) and CF (86, 248).

In addition, HMGB1-induced activation of MAPK pathways via binding to RAGE can lead to vascular remodeling by enhancing endothelial and epithelial cell proliferation (Fig. 3). HMGB1 has also been shown to directly increase the proliferation of primary arterial endothelial cells and pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells, as evidenced by activation of MAPK/ERK/p38 and activator protein 1 (AP-1; c-fos/c-jun) (366). Silencing the expression of c-jun significantly decreased the HMGB1-induced proliferation of endothelial and epithelial cells (366).

HMGB1-mediated activation of NF-κB can also induce the upregulation of α-smooth muscle actin (α-sma) and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) (340). As a mediator of vascular remodeling, TGF-β1 can induce phosphorylation of SMAD2 and SMAD3, which can phosphorylate the transcription factor signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT-3) (251, 316). Activated STAT-3 can induce cell proliferation and TGF-β-dependent myofibroblast differentiation (56, 251, 340). TGF-β-induced proliferation is STAT-3 dependent and inhibition of STAT-3 decreased α-sma, collagen deposition, total airway leukocytes, and the transition of fibroblasts to myofibroblasts (251, 316). Zhang et al. also reported that the exposure of alveolar epithelial cells to TGF-β1 promoted HMGB1 expression and epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT), as well as decreased RAGE expression (372).

EMT is stimulated by abnormal cell proliferation and differentiation and is characterized by a reversible alteration in the phenotype of epithelial cells to motile mesenchymal cells (117, 181, 305). During this process, epithelial cells are transformed into myofibroblasts, which secrete extracellular matrix (ECM) components and collagen (305, 315). During EMT, cell/cell junction dissolution occurs and fibroblasts and myofibroblasts accumulate, producing profibrotic factors, fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2) and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), in addition to α-sma, collagen, and ECM proteins (239, 340). The accumulation of ECM proteins can further promote airway remodeling, through which ECM components are cleaved causing ECM dysregulation, resulting in increased collagen deposition and tissue stiffening (117, 305). Lung stiffening and increased deposition of collagen and ECM promote fibrosis of lung tissue (305).

It has been reported that COPD patients have not only increased levels of HMGB1 in cigarette smoke-exposed neutrophils but also an increase in neutrophil autophagy, which can induce excessive levels of intracellular ROS, incite the release of neutrophil elastase, and increase airway obstruction (120, 205, 297). Excessive levels of neutrophil MPO and MMP9 can damage lung elastic fibers and the ECM, which impairs vascular remodeling (59, 302). Thus, HMGB1 may play a role in vascular remodeling and airway obstruction in COPD.

Overall, data suggest that decreasing the accumulation of extracellular HMGB1 and attenuating its downstream signaling with TLRs and RAGE may decrease inflammation, vascular remodeling, and fibrotic lung injury. Therefore, compounds targeting HMGB1 signaling pathways have been postulated to treat patients with lung diseases. Reagents, such as anti-HMGB1 antibodies, thrombomodulin, pulmonary rehabilitation mixture, and ethyl pyruvate, have been tested in animal models of lung diseases and are discussed further in this review.

Redox Regulation of HMGB1 Pathophysiology

On its secretion into the extracellular milieu, HMGB1 is subject to redox modifications at three critical cysteine residues: C23, C45, and C106 (149, 276, 328). Redox modification of these cysteine residues determines whether HMGB1 will function as a cytokine, chemokine, or an inactive protein (118, 159, 359). The oxidation of HMGB1 can form disulfide (C23 and C45) or fully oxidized isoforms, such as sulfonic acid (276, 359). Redox-modified HMGB1 has been shown to present in bronchoalveolar lavage fluids (BALF) of mouse models of ALI (85, 301). Redox regulation of HMGB1 has also been shown to play an essential role in the gender differences in PAH (258).

HMGB1, whether in the fully reduced or disulfide isoform, produces cytokine activity (203, 358, 359). However, on terminal oxidation (i.e., the sulfonic acid isoform), HMGB1's cytokine activity is abrogated, further demonstrating the significant role of redox modifications on the functions of HMGB1 (141, 359). When all three critical cysteines of HMGB1 are fully reduced, HMGB1 retains chemoattractant activity (213, 328).

Reduced HMGB1 with cytokine activity can induce inflammatory responses following binding to its receptors, such as the receptor for RAGE at HMGB1 150–183 residues (Fig. 1), by stimulating the expression and secretion of TNF-α by macrophages (13, 125, 178, 280, 310). Reduced HMGB1 can also bind to TLR4 and TLR2 at the 89–108 residues to stimulate the expression and secretion of proinflammatory mediators such as IL-8, IL-6, and TNF-α (358). The cysteine present at residue 106 (Fig. 1) is critical for the binding of HMGB1 to TLR4 (178, 358).

Interestingly, the heparin-binding domain of HMGB1, located in the A-box at amino acid residues 6–12 (Fig. 1), also regulates its binding to cell surface receptors (140, 217, 333, 355). When heparin is bound to HMGB1, the binding affinity of HMGB1 to RAGE is significantly decreased, indicating a unique mechanism for modulating HMGB1 activity (140, 217, 303, 375). Studies in our laboratory using 2-O,3-O desulfated heparin (ODSH), a modified heparin, demonstrated that blocking HMGB1 binding to its receptors could effectively attenuate bacterial infection-induced lung injury (291).

The clinical relevance of redox regulation of HMGB1 in the pathophysiology was demonstrated in the gender differences between female and male patients with PAH (258). In this study, the authors showed that cells from males are more likely to die by necrosis, while cells from females more likely die by apoptosis. During necrotic cell death, many thiols were released into the extracellular milieu, creating a reduced environment for extracellular HMGB1. Reduced HMGB1 elicits further inflammation, prolonging the stimulation of downstream inflammatory pathways. On the contrary, extracellular HMGB1 is more oxidized in an inflammatory environment in females with the influx of thiols from necrotic cells, thus losing the ability to bind to PRRs and triggering further inflammatory responses (258). Thus, redox regulation of HMGB1 may provide another approach to modulate the impact of extracellular HMGB1 on the pathogenesis of lung diseases.

Asthma

Globally, 300 million people suffer from asthma (244, 249, 277, 322). More than 80% of asthma deaths occur in low-income to lower middle-income countries, and in 2015, it was estimated that 383,000 deaths occurred from asthma globally (244, 345). Although asthma has a relatively low fatality rate compared with other chronic diseases, many asthmatics have symptoms that can significantly reduce their quality of life (80, 237, 244, 249). Asthma is often underdiagnosed and undertreated, creating a substantial burden to individuals that can restrict various activities for the remainder of their lives (244, 249). Recurrent asthma symptoms frequently cause sleeplessness, daytime fatigue, reduced activity levels, and school and work absenteeism (237, 244, 249).

Asthma is typically characterized by reversible airway obstruction, airway remodeling, airway hyperresponsiveness, and inflammation (71, 123). Airway irritants, such as pollution, dust, pollen, cold air, tobacco smoke, and chemical irritants, may trigger asthmatic reactions (26, 244, 249, 322, 345). Airway smooth muscle in asthmatic patients is hyperresponsive to certain stimuli such as environmental allergens, resulting in airway constriction and obstruction (236, 254). In addition, there is an increase in inflammatory mediator release and the smooth muscle mass of the lungs (80, 123, 126, 171, 206, 323). Furthermore, asthma airflow obstruction and airway remodeling can be triggered by inflammatory mediators (80, 105, 123, 228, 277, 279).

Extracellular HMGB1 has been shown to be involved in mediating certain inflammatory responses in asthma (Fig. 4) (145, 180). Indeed, HMGB1 levels are significantly increased in the airways of asthmatic patients and in animal models of asthma (71, 126, 206, 295, 315). Di Candia et al. reported that sputum concentrations of HMGB1 and HMGB1 expression in smooth muscle were significantly increased in patients with severe asthma (71). An increase in the airway levels of HMGB1 has been shown to occur in tandem with increased inflammation in neutrophilic sputum, increased blood neutrophil counts, and increased levels of MMP, chemokines, and cytokines in severe asthmatic patients (123, 126).

FIG. 4.

The role of HMGB1 in the pathogenesis of asthma. Asthma is pathologically characterized by airway inflammation, vascular remodeling, airway hyperreactivity, and constriction. Extracellular HMGB1 levels have been reported to be increased in asthma patients. The increased levels of airway HMGB1 in asthma can produce inflammation and vascular remodeling. Airway HMGB1 can bind to RAGE, TLR2, and TLR4. The binding of HMGB1 to these receptors can activate NF-κB and MAPK pathways. NF-κB activation stimulates the expression and secretion of proinflammatory mediators such as IL-8, IL-4, IL-5, IFN-γ, IFN-α, IL-13, IL-6, and IL-17, initiating the infiltration of eosinophils, neutrophils, and helper T cells into the airway. The presence of activated neutrophils in the lungs can increase the levels of ROS, proinflammatory cytokines, proteases (e.g., MMP9), and HMGB1, which can produce cell injury, further increasing neutrophil infiltration. HMGB1-mediated NF-κB activation can also promote the secretion of VEGF and TGF-β, which are involved in vascular remodeling. The subsequent vascular remodeling is characterized by loss of epithelial integrity, increased smooth muscle mass, smooth muscle cell proliferation, and subepithelial fibrosis. TGF-β-induced remodeling can result in an increase in lung fibroblast migration, mucus production, and secretion of ECM components as well as levels of MMP9, collagen, and α-sma. The airway injury that occurs as a result of inflammation and vascular remodeling produces airway hyperreactivity and reversible airway obstruction. ECM, extracellular matrix; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; MMP9, matrix metalloproteinase 9; sma, smooth muscle actin; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

The use of anti-HMGB1 antibodies has provided information about the role of HMGB1 in the pathogenesis of asthma. In mouse models of asthma, generated by exposing animals to compounds such as toluene 2,6-diisocyanate (TDI) or ovalbumin, the treatment of these animals with anti-HMGB1 antibody significantly attenuated elevated airway levels of MMP9, cytokines, cell counts, collagen levels, and leukocyte infiltration (126, 206, 369). In addition, airway hyperresponsiveness, inflammatory responses, and airway remodeling were significantly decreased in mice administered anti-HMGB1 antibodies (126, 206).

Moreover, in a mouse model of ovalbumin-induced airway hypersensitivity that produces some of the pathogenic characteristics of asthma, an antibody to HMGB1 significantly (i) inhibited lung HMGB1 expression; (ii) suppressed HMGB1-induced infiltration of neutrophils in the airways; (iii) decreased IL-23 levels and airway hyperresponsiveness; and (iv) attenuated T helper cell type 17 (Th17) secretion of IL-17, IL-4, and IFN-γ (369). Furthermore, eosinophilic airway inflammation, nonspecific airway resistance, and airway responsiveness were also significantly decreased in these animals (295).

Data obtained from mouse models of asthma indicate that HMGB1 stimulates the secretion of proinflammatory mediators such as TNF-α, IL-17, IL-6, IL-8, IL-1β, IL-4, and IL-5 (126, 295, 369). Moreover, HMGB1 mediates the recruitment of inflammatory cells, thereby exacerbating oxidative stress-mediated asthma pathology (126, 206). Indeed, fully reduced HMGB1 significantly increased intracellular ROS levels in the smooth muscles of nonasthmatics (71). The induction of oxidative stress by activation of the HMGB1/TLR4 pathway can subsequently oxidize HMGB1, thereby attenuating inflammatory responses as oxidized HMGB1 is less effective than reduced HMGB1 in eliciting inflammation (258). Although it is not clear how an oxidative environment affects the pathology of asthma, it may facilitate asthmatic airway remodeling of smooth muscle cells (71).

In patients with severe asthma, airway remodeling involves the accumulation of ECM proteins such as fibulin-1 and collagen (193). HMGB1 has been implicated in the increased deposition of ECM proteins suggesting a potential role in the airway remodeling that occurs in asthma (126, 239). HMGB1's role in airway remodeling is, in part, due to the upregulation of several proteases (i.e., MMPs), other enzymes, and growth-related proteins such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (76, 188). MMP9 and α-sma are involved in the remodeling of airway smooth muscle (89, 126, 171, 172). In mice with ovalbumin-induced airway hypersensitivity similar to asthma, HMGB1 can upregulate α-sma expression and increase MMP9 expression in the airways and interstitial lung tissue (126).

Excessive levels of airway HMGB1 in subjects with asthma are associated with increased lung levels of α-sma, increased number of fibroblasts (as a result of increased migratory activity), higher secretion of VEGF, TGF-β, higher collagen content, and airway hyperresponsiveness (126). In these mice, high levels of extracellular HMGB1 increased the hyperplasia of mucus secreting goblet cells, increasing mucus secretion (206). This is supported by findings showing that HMGB1 upregulates MUC5AC and MUC5B messenger RNA (mRNA) and protein in human bronchial epithelial cells via HMGB1-RAGE signaling (165).These changes were significantly attenuated by the systemic administration of an anti-HMGB1 antibody (206).

The HMGB1-induced increase in mucus could potentially contribute to the severity of rhinorrhea, airway hyperreactivity, and reversible airway obstruction in asthmatic patients. Overall, these studies suggest that HMGB1 may play a role in mediating inflammation and remodeling in asthmatic subjects. Thus, HMGB1 represents a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of asthma.

Studies using reagents that inhibit the release of HMGB1 or attenuate its downstream signaling pathways provide further support for the critical role of HMGB1 in the pathogenesis of asthma. In ovalbumin-induced asthmatic mice, the intravenous (via tail vein) administration of vitamin D significantly decreased airway resistance, inflammatory response, and inflammatory cytokine secretion, and increased the secretion of the anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-10 (370). Importantly, attenuation of these effects was correlated with a significant decrease in HMGB1 levels and HMGB1 translocation from the nucleus to cytoplasm (370). In addition, 10–100 mg/kg of ethyl pyruvate interperitoneally administered to mice with TDI-induced asthma significantly decreased the number of immune, cells including macrophages, neutrophils, eosinophils, and lymphocytes, and significantly decreased the levels of extracellular HMGB1 (315).

Overall, there are data suggesting that in asthma, HMGB1 plays a deleterious role in disease progression and severity by inducing inflammation and airway remodeling. Therefore, HMGB1 may be a potential therapeutic target in the treatment of asthmatic patients.

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

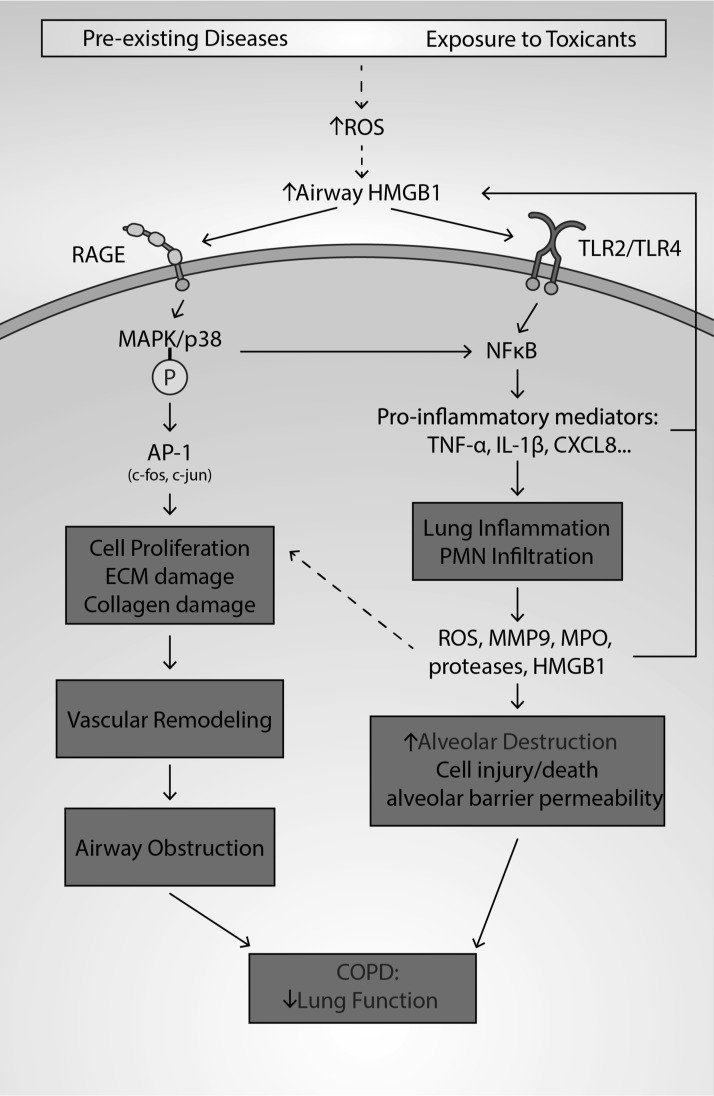

COPD (Fig. 5) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. As of 2010, estimates suggest that ∼328 million people suffer from COPD (198). Approximately 3 million people die each year from COPD, making it the fourth largest cause of death since the year 2000 (198). About 70% of all cases of COPD are caused by cigarette smoking or chronic inhalation of environmental and occupational air pollutants (198, 335). COPD is characterized by emphysema and chronic bronchitis (112, 162, 207). Decreased airflow in the lungs of COPD patients is a symptom caused by fixed airway obstruction and increased pulmonary inflammation (112, 162, 207). Repeated injury to the respiratory system from cigarette smoke or air pollutants in patients with COPD can result in alveolar tissue destruction (i.e., emphysema), hypersecretion of mucus (i.e., chronic bronchitis), and fibrosis, which can hasten disease progression (112, 162, 207).

FIG. 5.

The role of HMGB1 in the pathogenesis of COPD. COPD, caused by chronic inhalation of environmental pollutants, cigarette smoking, or preexisting diseases, is pathologically characterized by chronic obstruction of airways, alveolar dysfunction, and airway inflammation. Increased levels of ROS in the lungs of subjects with COPD can induce the accumulation of airway HMGB1. Airway HMGB1, via a number of mechanisms, can exacerbate COPD by inducing excessive lung inflammation and vascular remodeling. Lung inflammation is induced by HMGB1 binding to TLR2, TLR4, and RAGE, which increases the likelihood of NF-κB translocating to the nucleus. Subsequently, NF-κB increases the expression and secretion of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-8, TNF-β, IFN-γ, and MCP-1, which induce leukocyte infiltration and produce inflammation. Increased MPO activity, MMP9, and ROS levels from the neutrophils/monocytes can cause damage to the tight junctions of endothelial/epithelial cells, causing a loss of barrier integrity. Furthermore, the increased levels of elastase, proteases, MPO, and ROS can damage epithelial/endothelial cells, causing increased vascular and alveolar permeability, subsequently contributing to further HMGB1 accumulation in the airways and exacerbating lung inflammation. The injury and death of endothelial and epithelial cells can further result in alveolar destruction and a decline in lung function. HMGB1 also signals through RAGE to activate MAPK pathways. MAPK can activate the transcription factor AP-1, promoting proliferation of pulmonary endothelial and smooth muscle cells. Neutrophil elastase and MMP9 contribute to ECM and elastic fiber damage. Overall, these aforementioned changes promote vascular remodeling, which contributes to airway obstruction. AP-1, activator protein 1; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; MPO, myeloperoxidase; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

Recently, studies in both patients and animal models have implicated the role of HMGB1 in the pathogenesis of COPD. First, HMGB1 levels in the lung tissue of COPD patients were either 17-fold (smokers) or 10-fold (nonsmokers) greater than those of healthy controls (158). In addition, the increase in the airway levels of HMGB1 is negatively correlated with a 60% (smokers with COPD) and 40% (nonsmokers with COPD) decrease in the forced expiratory volume 1% (FEV1%) (90, 144). Furthermore, BALF samples from 14 healthy nonsmokers, 13 smokers without COPD, and 30 smokers with COPD were analyzed, and the levels of peripheral (alveolus and bronchioles) airway HMGB1 were significantly increased in COPD patients. This increase was positively correlated with a significant decrease in the FEV1% score (90). The mean HMGB1 levels in the peripheral BALF of smokers with COPD, smokers without COPD, and healthy controls were 1496, 816, and 250 ng/mL, respectively. Thus, both smokers with COPD and nonsmokers with COPD had significantly higher (p < 0.01) levels of peripheral airway HMGB1 compared with healthy controls (144).

In addition, in the subset of patients with COPD who also have other lung diseases, such as idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (COPD+IPAH), serum HMGB1 levels are further increased compared with healthy patients (366). The serum levels of HMGB1 from COPD+IPAH patients were 4.2 and 2.6 ng/mL for patients with only COPD, compared with 1.05 ng/mL in healthy volunteers (366). A study in 36 COPD patients reported a significant increase in serum HMGB1 compared with healthy controls. Increased HMGB1 levels were positively correlated with significant decreases in FEV1% and oxygen saturation (302). Interestingly, recent genome-wide association studies reported that HMGB1 is the top differentially expressed gene (p = 5.40 × 10−10) that is significantly correlated with decreased lung function (FEV1%) in COPD patients (224). Based on these results, it has been hypothesized that HMGB1 is involved in the pathogenesis of COPD (144, 224, 302, 366).

Numerous studies in animal models of COPD provide further compelling evidence for the role of HMGB1 in COPD pathology (31, 56, 366). While it is currently unknown whether HMGB1 accumulation in the lungs of COPD patients is due to disease progression or from direct injury to the lungs, it has been found that cigarette smoke induces the accumulation of HMGB1 in the airways of mice. The exposure of mice to five cigarettes four times a day for 3 days significantly increased HMGB1 accumulation in the airways and significantly upregulated TLR4 expression (56). Long-term exposure of mice to cigarette smoke can induce higher levels of HMGB1 in lung tissues (31). In addition, HMGB1 expression is increased in the lung tissue in animal models of COPD (59, 334). Furthermore, studies in in vitro models of COPD have revealed that hydrogen peroxide can induce the nuclear to cytoplasmic translocation of HMGB1, subsequently releasing significantly high levels of HMGB1 into the cell culture media (127).

Numerous studies indicate that excessive lung inflammation can also contribute to airway obstruction and exacerbation of COPD (59, 90, 158, 302, 366). It has been reported that in COPD patients, platelet-activating factor receptor (PAFR) levels are increased compared with nonsmoking healthy controls (297). The activation of PAFRs in COPD can elicit inflammatory cell recruitment, proinflammatory cytokine production, oncogenic cell growth, angiogenesis, and tumor growth and exacerbate inflammation (56, 205, 290, 297). HMGB1 levels are significantly increased in cigarette smoke-exposed neutrophils, which have an upregulated expression of PAFR (120, 297). In addition, the JNK, p38, and NF-κB pathways were activated by smoke exposure, and this effect was augmented by exogenous HMGB1 (56).

In TLR4-knockout mice exposed to cigarette smoke or in mice treated with an HMGB1 polyclonal antibody, the airway levels of IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, IFN-γ, IL-8, and MCP-1 were significantly decreased (56). In fact, in myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MyD88) knockout mice exposed to cigarette smoke and exogenous HMGB1, there was no significant activation of JNK and p38, and phosphorylation of NF-κB inhibitor (IκB-α) (56). Ethyl pyruvate (20 mg/kg administered concomitantly with cigarette smoke), an inhibitor of NF-κB activation (56), significantly decreased cigarette smoke-induced HMGB1 airway accumulation. These studies in mouse models of COPD suggest that airway HMGB1 can activate NF-κB and JNK/p38 pathways by TLR4- and MyD88-mediated pathways (56). The inflammation in COPD caused by cigarette smoke has been shown to induce neutrophil infiltration into the lung (56, 120, 205). Interestingly, continuous exposure of airway neutrophils to cigarette smoke induced a shift from neutrophil apoptosis to necrosis (120, 162, 205). Neutrophil-derived ROS and protease secretion can promote the progression of COPD (1, 77, 93, 259).

Moreover, the binding of HMGB1 to RAGE activates MAPK/p38 pathways in mouse models of COPD to induce vascular remodeling, which occurs in the lungs of COPD patients (173, 334). Overall, these data suggest that (i) HMGB1 may play a role in vascular remodeling and airway obstruction, and (ii) oxidative stress, generated after exposure to smoke, can induce the accumulation of extracellular HMGB1 in animals, activating its downstream pathways, leading to the COPD pathologies (127). Thus, while it is unclear whether HMGB1 induces COPD or is secondary to COPD initiation, it is evident that HMGB1 plays an essential role in the pathogenesis of emphysema and chronic bronchitis in COPD.

Acute Lung Injury/Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome

ALI and ARDS (Fig. 6) are major concerns for patients in intensive care units (ICUs) (29, 134, 227). A recent international study of 50 countries indicated that 10% of all admitted ICU patients were diagnosed with ALI/ARDS (29). Patients diagnosed with ALI/ARDS can develop respiratory failure and hypoxemia, and, currently, the only supportive measure is invasive mechanical ventilation (MV) with hyperoxia, which has been shown to exacerbate ALI and ARDS (29, 161, 227). The clinical outcomes for patients with ARDS are problematic, with mortality rates as high as 75% (367). ALI/ARDS is primarily caused by infection, sepsis, trauma, shock, and inhalation of toxicants, including particulate matter or other substances (161, 246, 252, 269). In addition, it is well known that animal models of ALI can be induced or exacerbated by prolonged exposure to hyperoxia (85, 115, 269, 319).

FIG. 6.

The role of HMGB1 in the pathogenesis of ALI and ARDS. ALI and ARDS are caused by various conditions and characterized by excessive lung inflammation, increased alveolar permeability, and impairment of respiratory function. Increased levels of airway HMGB1 in patients and animals with ALI and ARDS induce the accumulation of airway HMGB1. The deleterious effects of airway HMGB1 are mediated by excessive lung inflammation and alveolar destruction. Airway HMGB1 induces lung inflammation by binding to TLR2, TLR4, and RAGE, which increases the likelihood of NF-κB translocating to the nucleus, where it increases the transcription of genes that code for proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-4, and IL-6, causing leukocyte infiltration and inflammation. Leukocytes increase the levels of MPO activity, ROS production, and proteases, thereby damaging endothelial/epithelial cells and their tight junctions, causing the dysfunction of endothelial/epithelial and other lung cells, which compromises alveolar barrier and lung function. In addition, the activation of NF-κB is associated with HMGB1 hyperacetylation, which leads to its subsequent translocation to the cytoplasm and its active release into the airways. The increased production of ROS, such as NO, can inhibit SIRT-1 (a deacetylase enzyme) and can further stimulate HMGB1 release. Airway HMGB1 can also signal through RAGE-activated MAPK/p38 pathways, which can induce the phosphorylation of Hsp27, an actin-binding protein. Phosphorylated Hsp27 can produce endothelial cytoskeleton disorganization, paracellular gap formation, and the loss of peripheral organized actin fibers. These effects produced by phosphorylated Hsp27 can produce cell/cell junction dissociation and a loss of alveolar barrier integrity, which also contribute to a decrease in lung function. The accumulation of airway HMGB1 can be attenuated by cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway modulators (e.g., endogenous acetylcholine or GTS-21) and NF-κB inhibitors (e.g., ethyl pyruvate or GTS-21). Antioxidants, such as ascorbic acid, hydrogen sulfide (in gaseous form), and resveratrol, can also decrease ROS levels and decrease airway HMGB1 levels. ALI, acute lung injury; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; Hsp27, heat shock protein 27; SIRT-1, Sirtuin-1.

ALI is characterized by excessive lung inflammation with neutrophil/monocyte infiltration and dysfunction of the alveolar endothelial/epithelial barrier, leading to increased alveolar capillary permeability, subsequent lung cell dysfunction, and pulmonary edema (43, 85, 113, 269). A major pathological feature of ALI/ARDS is increased levels of cytokines/chemokines in the airways and plasma, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, MCP-1, IL-6, and IL-8 (13, 106, 185). Proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β and TNF-α, are early mediators of inflammation and are present primarily at the onset of ALI/ARDS (16).

After the first report of HMGB1's role as a late mediator of inflammation during septic shock, it was postulated that HMGB1 could be a major mediator of lung inflammation in endotoxin-induced lung injury (336). The intratracheal administration of HMGB1 can induce a concentration-dependent increase in the infiltration of interstitial/intra-alveolar neutrophils, alveolar red blood cells, levels of MPO and lung edema, similar to endotoxin-induced ALI. This suggests that HMGB1 may play a role in mediating inflammatory lung injury in ALI/ARDS (3, 326).

The level of HMGB1 in the airways of postsurgical patients who required MV for several days was 10-fold higher compared with patients who were ventilated for 5 h (377). However, the levels of airway HMGB1 in patients ventilated for 5 h were not significantly different from healthy controls. In addition, patients who developed postsurgery VAP had a 17-fold higher level of airway HMGB1 compared with healthy controls. These data suggest that prolonged exposure to MV is required to induce the accumulation of HMGB1 in the airways (377).

The role of HMGB1 in the pathogenesis of ALI has been further confirmed in mouse models. For example, the intratracheal administration of anti-HMGB1 antibodies (360 μg anti-HMGB1 antibody/mouse) ameliorated the development of lung injury and increased survival rates (3, 85, 248). In addition, airway HMGB1 can attenuate the phagocytosis of invading bacteria and apoptotic neutrophils by alveolar macrophages, exacerbating inflammatory lung injury (86, 94, 109, 248). Moreover, the HMGB1 box A protein, an antagonist of HMGB1 binding to the RAGE receptor, can significantly attenuate lung injury by decreasing airway inflammation, further suggesting that HMGB1 is involved in the initiation and progression of ALI/ARDS (103).

One major pathological feature of ALI/ARDS is the presence of excessive lung inflammation (191, 214, 342). The accumulation of airway HMGB1 has been reported to produce excessive lung inflammation (3, 13, 85). Extracellular HMGB1, on binding to pneumocytes, neutrophils, and macrophages, can produce potent proinflammatory effects that induce the release of other proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-8, MCP-1, and IL-6 (13, 178). Consequently, lung cells are injured, cell/cell junctions are damaged, and endothelial/epithelial barrier permeability is increased, causing lung injury and loss of lung function (43, 85, 113, 269, 348).

The other major pathological feature of ALI/ARDS is the presence of lung edema, in part, mediated by an increase in the permeability of the endothelial/epithelial barrier (33, 78, 219, 346). The binding of extracellular HMGB1 to TLR2, TLR4, and RAGE can compromise endothelial cell/cell junction and increase endothelial barrier permeability (348). While the binding to TLR receptors can cause inflammatory damage to lung cells, HMGB1 can also affect the permeability of endothelial cells by activation of RAGE-mediated pathway (287), as illustrated in Figure 3. Several mechanisms have been implicated in the accumulation of HMGB1 in the airways during lung injury. Various biomolecules, such as endotoxins, TNF-α, IFN-β, and hydrogen peroxide, as well as hyperoxia, can induce hyperacetylation and release of HMGB1 from lung cells (85, 201, 248, 314, 336). These results suggest that HMGB1 is one of the mediators that induce the loss of endothelial barrier integrity, causing inflammatory lung injury in patients with ALI/ARDS.

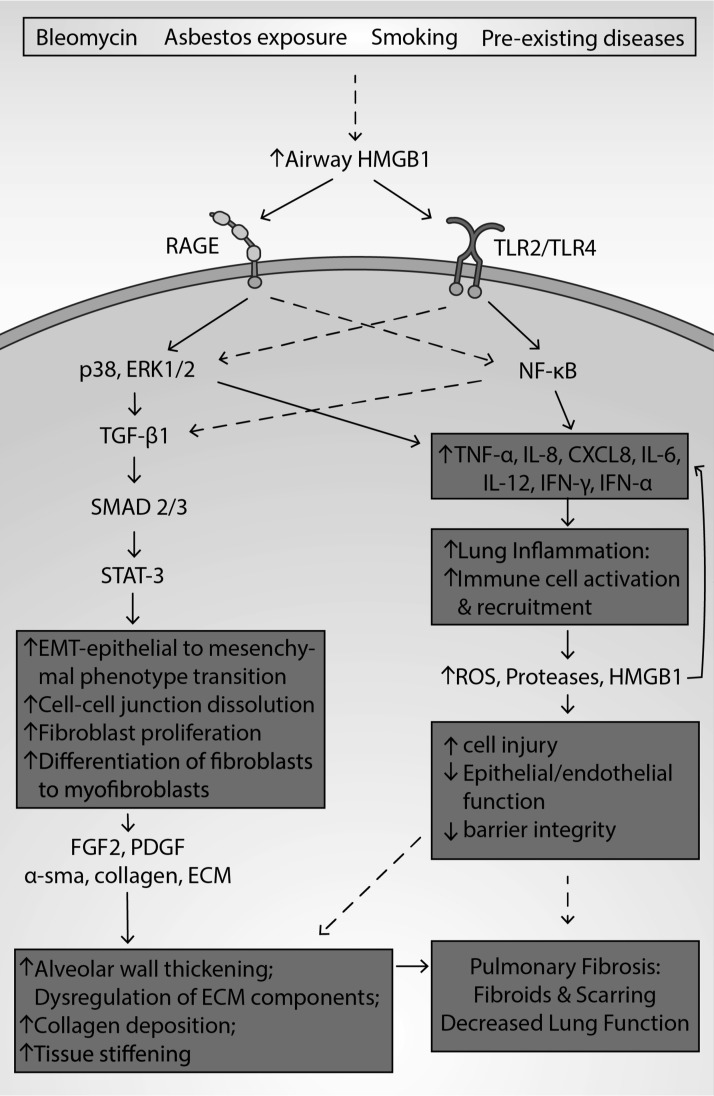

Pulmonary Fibrosis

Pulmonary fibrosis (PF) is an interstitial lung disease that is often irreversible and lethal (153, 157, 284, 341). The median survival of PF is 3 years, and it affects 50,000 individuals annually in the United States (283, 341). Between 1988 and 2005, the estimated incidence of PF increased from 6.8 to 17.4 per 100,000 people in the United States (230). PF is characterized by lung scarring and the formation of fibroids, inflammation, vascular leakage, myofibroblast recruitment, and deposition of elevated amounts of ECM proteins (157, 180, 283). Lung tissue scarring impairs the diffusion of oxygen through alveolar walls into the bloodstream (5, 174, 284).

Patients with PF experience shortness of breath and dry cough (84, 157, 284). PF can increase susceptibility to other conditions such as pneumonia, pneumothorax, pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary embolism, and eventually, respiratory and heart failure (135, 284, 304). While individuals can be genetically predisposed to PF, exposure to hazardous materials (e.g., asbestos, pollutants, and cigarettes) and comorbidities such as autoimmune diseases, sarcoidosis, COPD, and viral infections can increase the risk of PF (157, 284, 294). Genetics can account for up to 30% of the risk of developing PF (7, 146, 284, 286, 360). Mutations in surfactant protein A2 and C, and mutations affecting telomere length are all associated with an increased risk of PF (7, 360).

In patients and subjects with PF, decreased survival has been associated with increased levels of serum and airway HMGB1 (84, 114, 296, 372). In addition, in a mouse model of bleomycin-induced PF, the administration of anti-HMGB1 antibody significantly attenuated the thickening of alveolar walls, decreased collagen content in lung homogenate, and lowered the number of total immune cells present in the airways (114). These studies suggest that HMGB1 plays a role in PF pathogenesis and the degree of disease severity.

HMGB1 plays a role in mediating fibrosis and airway remodeling in PF. HMGB1 can stimulate ROS production, increase α-sma, collagen deposition, and TGF-β, induce the differentiation of fibroblasts to myofibroblasts, and increase the gene expression of MUC8, a mucin that denotes aberrant alveolar epithelia common in PF (154, 340). Zhang et al. also reported that in a model of PF, collagen fibers in the lung tissue of rats were significantly increased in bleomycin-treated rats compared with animals treated with vehicle (373).

The HMGB1-RAGE axis also plays a role in the inflammatory pathology of PF. In a bleomycin-induced PF model, 29% of wild-type mice survived after 14 days of bleomycin administration, while 100% of RAGE knockout mice survived (117). Furthermore, in this PF model, RAGE knockout mice had lower levels of fibrotic deposition and decreased airway levels of TGF-β1. However, total leukocyte, lymphocyte, macrophage, and neutrophil infiltration into the lung, and airway levels of HMGB1 were not reduced, suggesting that HMGB1 inflammatory signaling in PF may be more complicated than RAGE signaling alone (117). Treatment of animals with an anti-RAGE antibody and pharmacological inhibition of ERK1/2 significantly decreased epithelial barrier disruption and permeability associated with inflammation (117, 133). Furthermore, direct inhibition of NF-κB by pyrrolidinedithiocarbamate (PDTC) or upstream inhibition by targeting TLR2 in bleomycin-induced PF reduces edema, histological markers of inflammation in lung tissue, HMGB1-induced TGF-β1 release, collagen-1 levels, and α-sma expression (177, 340).

The role of HMGB1 and the levels of RAGE expression and its signaling pathways are not only limited to lung inflammation but are also associated with remodeling and deposition of fibrotic tissue in PF. Increased levels of RAGE are associated with ameliorated lung injury and decreased apoptosis in alveolar epithelial cells (372). However, in a rat model of PF, RAGE expression was significantly decreased compared with the controls (372). Furthermore, in a model of bleomycin-induced PF, RAGE null mice had less fibrotic injury, such as edematous alveolar thickening, cellular infiltration, fibrosis, and collagen deposition (84, 117). Thus, HMGB1/RAGE interaction and signaling in the profibrotic processes play a role in the development of PF.

HMGB1-mediated activation of NF-κB also plays a role in airway remodeling in PF. HMGB1-mediated activation of NF-κB can induce the upregulation of α-sma and TGF-β1, a mediator of vascular remodeling via SMAD-STAT-3 signaling (84, 180, 251, 316, 373). Activated STAT-3 can increase α-sma, collagen deposition, and total airway leukocytes and can induce cell proliferation and TGF-β-dependent myofibroblast differentiation (251, 316, 340). Zhang et al. also reported that the exposure of alveolar epithelial cells to TGF-β1 promoted HMGB1 expression and decreased RAGE expression (372). These studies suggest that HMGB1 may play a role in EMT via SMAD-STAT signaling.

Compounds targeting RAGE or HMGB1 have been used in PF models; however, the clinical efficacy of these compounds remains to be determined. Anti-HMGB1 antibodies and HMGB1 neutralizing reagents such as thrombomodulin decrease the levels of HMGB1 in animals and attenuate fibrotic lung injury (2, 140, 153, 187). Thrombomodulin binds directly to HMGB1 and cleaves it, degrading it to a less inflammatory form (2, 140, 153, 187). Thrombomodulin improves the survival rate of patients by inactivating coagulant factors and thrombin, as well as by competitively inhibiting the binding of HMGB1 to receptors such as TLR4 and RAGE (153, 180, 296).

Treatments targeting the RAGE-HMGB1 signaling pathway could significantly ameliorate the pathology and symptomatology of PF. Although current treatments, such as prednisone, azathioprine, and N-acetylcysteine, may improve the symptoms of PF, there is a need for PF-specific therapies targeting disease biomarkers such as HMGB1 (124, 211, 306). Overall, data suggest that decreasing the accumulation of HMGB1 and attenuating its downstream signaling with RAGE may decrease inflammation in PF. Thus, HMGB1 may be a novel therapeutic target that has the potential to decrease mortality and severity of symptoms in PF (Fig. 7) (153).

FIG. 7.

The role of HMGB1 in the pathogenesis of PF. PF, an interstitial lung disease, is characterized by fibroblast proliferation, EMT, lung inflammation and the formation of fibroids, producing lung scarring. Patients and animals with PF have been shown to have increased levels of airway HMGB1. HMGB1 may be involved in the pathogenesis of PF as it can produce fibroblast differentiation and proliferation, alveolar wall thickening or muscularization thickening, and collagen accumulation. HMGB1 binds to RAGE, TLR2, and TLR4, activating both NF-κB and MAPK/p38/ERK 1/2 pathways. NF-κB activation and the p38 pathway can increase the levels of proinflammatory mediators and TGF-β1. As a mediator of vascular remodeling, TGF-β1 can induce phosphorylation of SMAD2 and SMAD3, which phosphorylate the transcription factor STAT-3. STAT-3, when activated, induces cell proliferation and myofibroblast differentiation. STAT-3 activation promotes EMT, where epithelial cells develop mesenchymal characteristics such as loss of cell/cell adhesion. The increased number of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts can stimulate the formation of fibrotic tissue. TGF-β1 can elicit the release of α-sma, upregulate HMGB1 expression, and induce secretion of the profibrotic factors FGF2 and PDGF. α-sma directly stimulates the EMT process, causing an increased accumulation of ECM proteins, which augments airway remodeling. ECM-mediated remodeling involves the dysregulation of ECM composition, cleavage of ECM components, increased collagen deposition, and stiffening of tissue. In addition to inducing remodeling, the binding of HMGB1 to RAGE and TLR4 stimulates the expression and secretion of TNF-α, MCP-1, IL-8, and IL-1β. These proinflammatory mediators recruit and induce the accumulation of macrophages, neutrophils, and lymphocytes into the airways, increasing the levels of proteases, ROS, and HMGB1, establishing a deleterious feedback loop. The release of these molecules contributes to epithelial and endothelial injury and death, dissolution of cell/cell junctions, and loss of barrier integrity, thereby increasing alveolar permeability. Thus, HMGB1-mediated airway remodeling and inflammation contribute to lung fibrosis, scarring, and decreased lung function. EMT, epithelial to mesenchymal transition; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; FGF2, fibroblast growth factor 2; PF, pulmonary fibrosis; STAT-3, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3.

Cystic Fibrosis

CF (Fig. 8) is a genetic disease affecting 30,000 people, with ∼1000 new cases diagnosed each year in the United States (64, 81). CF is diagnosed by phenotypic features, including sinopulmonary disease, gastrointestinal and nutritional abnormalities, persistent cough with thick mucus, wheezing, recurrent lung infections, as well as poor weight gain and growth (82, 102, 285). Histopathological studies indicate that neutrophilic inflammation and pulmonary infections occur frequently in CF patients, producing acute pulmonary exacerbation and severe lung dysfunction (21, 35, 50, 57, 83, 102).

FIG. 8.

The role of HMGB1 in the pathogenesis of CF. CF is a disease caused by mutations in the CFTR gene and its pathological hallmarks include neutrophilic inflammation and bacterial infections. An increased expression and accumulation of HMGB1 are present in CF airways, resulting in an increase in HMGB1 levels in bronchoalveolar lavage fluids, sputum, and serum of CF patients. HMGB1 elicits chemotactic activity by interacting with the chemokine CXCR2 receptors on neutrophils, thereby recruiting them into the airways, compromising macrophage phagocytosis. In CF, HMGB1 may produce an impairment of macrophage efferocytosis, which decreases the removal of apoptotic neutrophils and the clearance of pathogenic bacteria. We postulate that the activation of the TLR4 receptor by HMGB1 attenuates macrophage function, producing a higher bacterial load and excessive inflammation in the airways and lung tissue, causing lung injury. The increase in PAMP and DAMP biomolecules from the increased bacterial load and excessive inflammation further stimulates the release of HMGB1 from airway cells, producing a deleterious feedback cycle between the release of HMGB1 and the development of lung injury. In addition, serum HMGB1 impairs the function of pancreatic β cells by activating RAGE and TLR4, producing insulin deficiency and insulin resistance, causing CFRD. Insulin and ODSH can reduce HMGB1 expression and translocation from the nucleus to cytoplasm in cells (epithelial cells and macrophages, respectively). ODSH can also reduce chronic neutrophil-mediated inflammation induced by neutrophil elastase in CF. CF, cystic fibrosis; CFRD, cystic fibrosis-related diabetes; CXCR, CXC-chemokine receptor; ODSH, 2-O,3-O desulfated heparin; PAMP, pathogen-associated molecular pattern.

The first clinical report on CF was published in 1938 and, until recently, the majority of individuals diagnosed with CF died in infancy or early childhood (10). As a result of improvements in symptomatic management, including the use of anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial drugs and nutritional supplements, more than two decades have been added to the life span of CF patients (82, 240). However, the median survival age is still only around 40 years, and thus, novel therapeutic approaches and biomarkers that are predictive of the development of CF are urgently needed (40, 64, 240).

Studies over the last two decades suggest that HMGB1 may represent a new therapeutic target for CF (86, 320). CF is caused by mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene that encodes the CFTR protein (151, 164). Almost 2000 mutations in the CFTR gene have been identified, which are classified into six major classes based on the effects of the mutations on the CFTR protein (28, 82, 164). The mutations alter the secondary and tertiary structure of CFTR protein, a chloride ion channel, resulting in impaired secretion of chloride and an increase in sodium absorption (164). This can cause abnormal levels of chloride, bicarbonate, sodium ions, and water, affecting the epithelial lining in the lungs and digestive system (38, 151).

Levels of HMGB1 are significantly increased in the BALF, sputum, and serum of CF patients (110). The two secondary pathogenic mechanisms of CF in the airway are the recruitment of neutrophils and susceptibility to Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA) infections, which further increase HMGB1 release into the airways (110). A high load of neutrophil elastase, as a result of neutrophil recruitment, can further induce the in vitro and in vivo release of HMGB1 from macrophages (110). In Scnn1b-transgenic mice, which exhibit obstructed mucus production similar to the CF phenotype, and in CFTR−/− CF mouse models, HMGB1 levels are significantly increased in the lungs and airways, subsequently increasing the number of leukocytes in the airways through a CXC-chemokine receptor (CXCR)-dependent mechanism (86, 274). Moreover, an anti-HMGB1 antibody decreases the chemotactic efficacy of HMGB1 in CF patient sputum and in the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) of CF Scnn1b-transgenic mice (274). These findings are congruent with studies reporting that the administration of an anti-HMGB1 antibody to CF mice significantly decreased neutrophil infiltration into the airways and attenuated inflammatory lung injury (86, 274). Thus, these studies suggest that HMGB1 plays a role in mediating neutrophilic inflammation in CF.

Pulmonary infections, particularly those due to PA, occur frequently in CF patients, as a result of compromised immunity (42, 64, 86, 142, 167). For example, macrophages from CF patients have a significantly lower phagocytic activity compared with healthy individuals (142). The impaired macrophage phagocytosis compromised by CF patient BALF may be mediated by increased levels of airway HMGB1 as CF BALF-compromised macrophage phagocytic activity was attenuated following the administration of an anti-HMGB1 antibody (86). Furthermore, macrophages from TLR4−/− mice do not respond to the HMGB1-mediated impairment of macrophage phagocytosis, suggesting that HMGB1-mediated macrophage dysfunction occurs via HMGB1 activation of TLR4 (86).

HMGB1 can also inhibit neutrophil efferocytosis by macrophages in CF, resulting in the accumulation of apoptotic neutrophils in the airways, which can augment proinflammatory responses (194). Alveolar macrophages in CF are also characterized by the overproduction of sCD14 and inflammatory cytokines, as well as a decreased expression of CD11b and TLR5, leading to an overactive proinflammatory response and nonresolution of infection by CF macrophages (142). Pulmonary infections, such as PA, can further induce the release and subsequent accumulation of airway HMGB1, creating a detrimental feedback cycle between infections and HMGB1 accumulation in the lungs (200). However, PA in CF patients does not significantly alter the expression of HMGB1 mRNA, suggesting that PA induces HMGB1 extracellular accumulation by increasing HMGB1 nucleocytoplasmic translocation and release into the airways in CF (320).

At present, the mechanisms that induce HMGB1 accumulation in the airways of CF patients remain to be elucidated. Montanini et al. reported that HMGB1 expression in the CF epithelial cell line, CFBE41o-, is significantly higher than the normal control 16HBE14o- cells (222). The incubation of 16HBE14o- cells with a CFTR inhibitor (CFTR inh 172) increases HMGB1 expression, suggesting that loss of CFTR function can induce HMGB1 expression (222). In the same study, insulin significantly decreased HMGB1 gene expression in CF epithelial cells, suggesting a correlation between upregulated HMGB1 and the diabetic condition in CF subjects. It was postulated that HMGB1 can serve a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of patients with CF (222).

In conclusion, these studies suggest that HMGB1 can serve as a biomarker in CF. However further studies are needed to determine the sources and mechanisms of extracellular HMGB1 accumulation in CF patients, as well as to verify the role of HMGB1 as a therapeutic target in CF.

Pneumonia

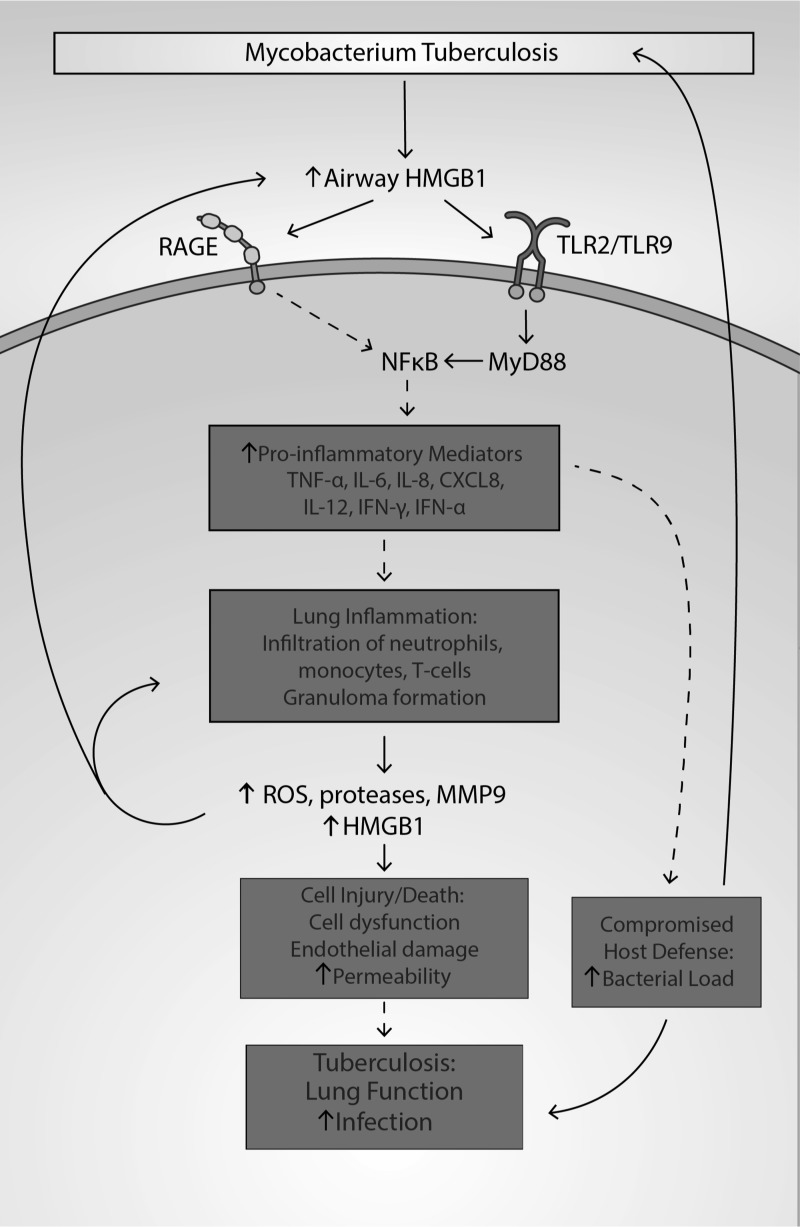

Pneumonia (Fig. 9) is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the alveoli. The main cause of pneumonia is infection of the lung parenchyma, and it is symptomatically characterized by productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and troubled breathing (325). Pneumonia is a leading cause of hospitalization among adults and children in the United States, and at least 1 million people seek medical care for the disease every year. In the United States, ∼50,000 people die from pneumonia annually (60, 61, 241). Globally, 1 million children younger than the age of 5 die from pneumonia each year, which is greater than the numbers of death by any other infectious disease in children, including HIV, malaria, and TB (47, 197, 209, 330). Pneumonia can be caused by bacteria, viruses, and less commonly, fungi. The risk of pneumonia is increased in patients with other health conditions such as asthma, COPD, diabetes, or compromised host defense due to treatments with drugs (60, 61, 232, 241). Based on the setting in which it develops, pneumonia can be categorized into (i) community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), (ii) hospital-acquired pneumonia, (iii) health care-acquired pneumonia, and (iv) aspiration pneumonia (23, 73, 241, 255, 268).

FIG. 9.

The role of HMGB1 in the pathogenesis of pneumonia. Pneumonia is a disease caused by bacteria, viruses, and fungi that can produce pulmonary inflammation. Risk factors include the presence of other diseases such as CF, COPD, and asthma. PAMP molecules released by viruses and bacteria interact with cell surface receptors such as TLRs and RAGE, which increases oxidative stress and the expression of HMGB1, leading to its increased translocation and subsequent release of HMGB1 from airway cells such as macrophages and epithelial cells. The release of HMGB1 induced by LPS is JNK dependent. The accumulation of HMGB1 in the airway activates NF-κB and ERK/p38 pathways by binding to TLRs and RAGE on airway cells, increasing the production of ROS, inflammatory cytokines, ICAM-1, and vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1). Airway HMGB1 can also induce the expression of TLR2 on certain cells, further increasing inflammatory responses in the lung. These molecules mentioned above can elicit excessive inflammation and tissue damage in the lung. ICAM-1, intercellular adhesion molecule 1; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; VCAM-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule 1.

The levels of HMGB1 in the lung tissues and body fluids are altered in patients with pneumonia. Significantly higher levels of HMGB1 in BALF, sputum, and plasma have been reported in patients with different types of pneumonia compared with healthy individuals (8, 14, 122, 248, 338, 378). Interestingly, Wang et al. reported that plasma levels of HMGB1 are decreased in patients with pneumonia after antibiotic treatments (338). Furthermore, the plasma levels of HMGB1 were positively correlated with the pneumonia severity index (PSI) score, suggesting that HMGB1 levels may be indicative of pneumonia severity, although lack of such correlation was also observed in other studies (14, 122, 338). Such conflicting results may be due to small sample sizes, differences in the causes of pneumonia, and other confounding risk factors during the treatments and hospitalization (8). Nonetheless, these studies indicate that HMGB1 concentrations in plasma/serum were elevated in patients with pneumonia and remained elevated throughout the course of treatments in hospitals. In addition, the level of HMGB1 in the sputum is significantly higher in patients with pneumonia caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae (8). These studies suggest that significantly increased levels of HMGB1 can be a biomarker of pneumonia, but they do not indicate the prognosis of pneumonia. Thus, future research should be conducted under narrower scopes and focus on the role of HMGB1 in pneumonia with more specific settings.

Studies using anti-HMGB1 antibodies have demonstrated that HMGB1 mediates the pathology of pneumonia (129, 248, 317). In numerous mouse models of pneumonia, targeting HMGB1 with monoclonal antibodies not only attenuated inflammatory lung injury but also decreased bacterial burden in the lungs of mice with VAP, Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia, and pneumonia due to influenza A virus subtypes H5N1 and H1N1 (92, 129, 235, 248). By neutralizing HMGB1 with anti-HMGB1 antibodies in mouse and human adenovirus-infected epithelial cells, HMGB1-mediated inflammation can be significantly reduced, accompanied by a decrease in the expression of HMGB1 receptors, (e.g., TLR4, TLR9, RAGE), and decreased NF-κB activation (317).

PAMPs, including bacterial components such as LPS, peptidoglycan, and lipoteichoic acid, can activate airway cells via PRRs (alveolar macrophages and epithelial cells) to increase HMGB1 expression and induce the translocation and release of HMGB1 into the extracellular milieu (324, 376). Bacteria, including Mycoplasma pneumoniae, S. pneumoniae, S. aureus, and Escherichia coli, have been shown to induce the release of HMGB1 into the airways in mice (4, 74, 260). Viruses, such as human adenovirus and influenza A virus, can evoke HMGB1 release and subsequently induce an HMGB1-mediated inflammatory response via activation of NF-κB (317, 379).

In addition, these pathogens not only promote HMGB1 expression and HMGB1 release by interacting with PRRs such as RAGE but also upregulate the expression of these receptors, exacerbating the downstream cascades that can result in an inflammatory response. Morbini et al. reported that RAGE expression was significantly upregulated in patients with interstitial and postobstructive pneumonia (223). TLR receptors and RAGE are also upregulated during pneumonia caused by M. pneumoniae, S. pneumoniae, human adenovirus, and influenza A virus (74, 317, 379).

HMGB1 can be passively or actively released into the airways by injured cells and immune cells on exposure to respiratory infections, which contributes to the high levels of extracellular HMGB1 accumulation in the lung of patients with pneumonia (199, 248). However, the main source of the circulating HMGB1 in plasma/serum is from activated immune cells rather than injured cells in patients with CAP (8). Airway HMGB1 can function as a DAMP molecule that can activate immune cells via PRRs (e.g., TLR2, TLR4, and TLR9) and RAGE (267). During pulmonary bacterial infection, PRRs can be activated by both PAMPs and DAMPs such as HMGB1, which together can cause synergetic effects in activating immune cells, producing exacerbated inflammatory lung injury (8, 130, 256).