Abstract

CRISPR-Cas systems are widespread bacterial adaptive defence mechanisms that provide protection against bacteriophages. In response, phages have evolved anti-CRISPR proteins that inactivate CRISPR-Cas systems of their hosts, enabling successful infection. Anti-CRISPR genes are frequently found in operons with genes encoding putative transcriptional regulators. The role, if any, of these anti-CRISPR-associated (aca) genes in anti-CRISPR regulation is unclear. Here, we show that Aca2, encoded by the Pectobacterium carotovorum temperate phage ZF40, is an autoregulator that represses the anti-CRISPR–aca2 operon. Aca2 is a helix-turn-helix domain protein that forms a homodimer and interacts with two inverted repeats in the anti-CRISPR promoter. The inverted repeats are similar in sequence but differ in their Aca2 affinity, and we propose that they have evolved to fine-tune, and downregulate, anti-CRISPR production at different stages of the phage life cycle. Specific, high-affinity binding of Aca2 to the first inverted repeat blocks the promoter and induces DNA bending. The second inverted repeat only contributes to repression at high Aca2 concentrations in vivo, and no DNA binding was detectable in vitro. Our investigation reveals the mechanism by which an Aca protein regulates expression of its associated anti-CRISPR.

INTRODUCTION

Among the mechanisms that bacteria possess to protect themselves against bacteriophages (phages) and other mobile genetic elements (MGEs), CRISPR-Cas systems are the only known adaptive means of defence (1,2). CRISPR-Cas systems are subdivided into two classes and multiple types and subtypes (3). Most types acquire short sequences from an invader and store them as ‘spacers’ in loci termed clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPRs) (4,5). Transcription and processing of CRISPR loci generates short CRISPR RNAs (crRNAs), each containing a spacer which guides CRISPR-associated (Cas) proteins to the complementary sequence within the invading MGE and triggering nucleolytic cleavage of the target (6).

Recently, phages and MGEs have been shown to encode anti-CRISPR proteins (Acrs) that they use to inactivate the CRISPR-Cas systems of their hosts (7). Since the discovery of Acrs, significant effort has been directed towards the elucidation of their structures and mechanisms of action (8), their applicability in Cas9- or Cas12-mediated genome editing (9) and their evolutionary and ecological implications (10–12). Since the targets of Acrs include a broad variety of CRISPR-Cas subtypes and proteins, they are diverse, making it difficult to identify new acr genes based on sequence similarity alone. However, acrs were originally found immediately next to a highly conserved gene, later termed anti-CRISPR-associated 1 (aca1) (7,13). Based on this finding, gene synteny became a major strategy to identify novel acrs that were highly divergent in sequence but encoded next to the same aca gene (13–16). This led to the further discovery of genes encoding the associated proteins Aca2-7 (13,15,17). Despite their role in anti-CRISPR discovery, the function of Aca proteins is unclear. All known Aca proteins contain predicted helix-turn-helix motifs (13,15,17), which led to the proposal that they may regulate their respective operons containing acr and aca genes, and thus control Acr levels (14). However, whether Aca proteins are autoregulators and regulators of anti-CRISPRs remains untested.

Aca2 is an anti-CRISPR-associated protein found with various anti-CRISPRs (13). For example, in the prophage ZF40 of Pectobacterium carotovorum str. ZM1 (18,19), the aca2 gene is associated with acrIF8 in an acrIF8–aca2 operon (Figure 1). AcrIF8 is an anti-CRISPR that inactivates the type I-F CRISPR-Cas systems of both Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Pectobacterium atrosepticum (13), two important model organisms for the elucidation of type I-F system function (20–23). Here, we show that Aca2 is a dimer that represses the expression of the acrIF8–aca2 operon, and that this autoregulation is mediated through binding to inverted repeats in the promoter region.

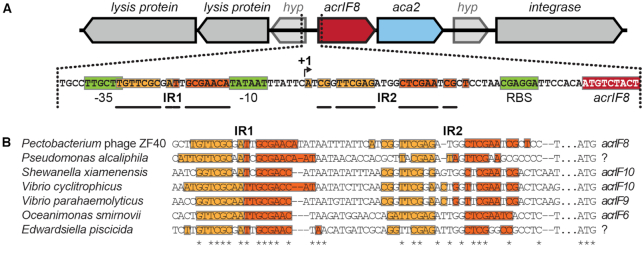

Figure 1.

Inverted repeat pairs are conserved in acr–aca2 operon promoters. (A) Genomic context of the acrIF8–aca2 locus of phage ZF40 with inverted repeat pairs (shades of orange; bold bars illustrate symmetry and distance between each half-site of the respective repeat). Predicted regulatory sequences (-35 and -10 sites, and ribosome binding site (RBS)) in green, predicted transcription start site (+1) indicated by an arrow. (B) Alignment (24) of acr–aca2 operon promoters with inverted repeats displayed as in (A). Invariant residues are indicated by an asterisk and the acr genes encoded downstream are given where known. Question marks indicate genes that have no matches among known acr genes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

Strains used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table S1. Unless otherwise noted, P. carotovorum and Escherichia coli strains were grown at 30°C and 37°C, respectively, either in Lysogeny Broth (LB) at 180 rpm or on LB-agar plates containing 1.5% (w/v) agar. When required, media were supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (25 μg/ml), l-arabinose (as noted) and/or isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (as noted). Growth was monitored as the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) in a Jenway 6300 Spectrophotometer or in a Varioskan LUX Microplate Reader.

DNA isolation and manipulation

Oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table S2. Plasmid DNA was isolated using the Zyppy Plasmid Miniprep Kit (Zymo Research) and all plasmids were confirmed by DNA sequencing. Plasmids used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table S3 and their construction is outlined in the Supplementary Methods. Restriction digests, ligations, E. coli transformations and agarose gel electrophoresis were performed using standard techniques. Transformation of P. carotovorum strains was carried out by electroporation using a Bio-Rad GenePulser Xcell system (set to 1800 V, 25 μF, 200 Ω) in Bio-Rad electroporation cuvettes with a 0.1 cm electrode gap, followed by 2 h recovery in LB medium at 30°C at 180 rpm. DNA from PCR and agarose gels was purified using the Illustra GFX PCR DNA and Gel Band Purification Kit (GE Healthcare). Polymerases, restriction enzymes and T4 ligase were obtained from New England Biolabs or Thermo Scientific.

Structural modelling and sequence analysis

DNA sequence analyses were performed using Geneious 10.0.7 software (https://www.geneious.com) and ClustalΩ was used for sequence alignments (24). Protein BLAST (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) was used for identification of Aca2 homologs. The Aca2 structural model was generated by homology modelling using Phyre2 (25) with the MqsA structure bound to DNA (PDB: 3O9X) (26). The DNA-bound Aca2 dimer model was generated by aligning copies of the Phyre2 Aca2 model with each of the DNA-bound MqsA subunits using Pymol. The genome similarity of P. carotovorum strains RC5297 and ZM1 was compared using the ChunLab's online Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) Calculator (27). Strengths of ribosome binding sites were calculated using the De Novo DNA RBS Calculator (Salis Lab, https://salislab.net/software/).

Reporter assays

Reporter assays for measuring acrIF8–aca2 promoter activity involved arabinose-inducible aca2 expression plasmids and/or reporter plasmids with eyfp under control of the acrIF8–aca2 promoter. To determine the effect of aca2 expression on acrIF8–aca2 expression, each eyfp reporter plasmid was tested with an aca2 expression plasmid (+Aca2; pPF1532) as well as the corresponding empty vector (–Aca2; pBAD30). Overnight starter cultures of P. carotovorum strains containing plasmids were grown in 96-well plates in an IncuMix incubator shaker (Select BioProducts) at 1200 rpm at 30°C. The OD600 for each was adjusted to 0.05 in LB medium containing the appropriate antibiotics, and if required, arabinose and IPTG were added to final concentrations of 0.05% (w/v) and 50 μM, respectively, unless otherwise noted. After 20 h of growth, fluorescence of plasmid-encoded mCherry and eYFP was measured by flow cytometry using a BD LSRFortessa cell analyzer. Cells were first gated based on forward and side scatter area, and mCherry-positive cells, as detected using a 610/20-nm bandpass filter with a detector gain of 606 V, were further analysed for eYFP levels using a 530/30-nm bandpass filter and detector at 600 V. Median fluorescence intensity of eYFP was measured for at least three replicates. Measurements for a control strain containing empty vectors were subtracted from the other samples to account for background fluorescence.

Aca2 expression and purification

An overnight culture of E. coli BL21(DE3) carrying the aca2 expression plasmids pPF1575 (wild-type Aca2) or pPF1857 (Aca2R30A) was diluted 1:100 in 500 mL LB supplemented with ampicillin. The culture was incubated at 25°C and 200 rpm until it reached an OD600 of ∼0.5, at which point IPTG was added to a final concentration of 1 mM. The culture was incubated at 18°C for 18 h and pelleted by centrifugation (10 000 g, 4°C, 10 min). For protein purification, 0.5 g of wet cell pellet was resuspended in 20 ml binding buffer (25 mM HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl and 25 mM imidazole, 0.1 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP)) supplemented with one cOmplete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail tablet (Roche), 20 μg/ml DNase I and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF). Cells were lysed by two cycles through a French Press at 10 000 psi. The lysate was cleared by centrifugation (10 000 g, 4°C, 10 min), followed by the addition of more PMSF (1 mM) and a second centrifugation step (10 000 g, 4°C, 10 min).

The clarified lysate was loaded, using an FPLC system (ÄKTA pure, GE Healthcare), onto a 1 ml HisTrap FF column (GE Healthcare) that was pre-equilibrated with binding buffer. The column was washed with binding buffer and 5 column volumes (CV) of 10% elution buffer (0.1 mM TCEP, 25 mM HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl and 500 mM imidazole). Aca2 was eluted using a linear imidazole gradient to 100% elution buffer over 10 CV. Fractions containing Aca2, as determined using NuPAGE 4-12% Bis-Tris Protein Gels (Thermo Scientific), were pooled into dialysis tubing (SnakeSkin 3.5 kDa MWCO, Thermo Scientific) and TEV protease was added. The sample was dialyzed overnight at 4°C in size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) buffer (0.1 mM TCEP, 25 mM HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.5 and 300 mM NaCl). Reverse-IMAC was performed to separate the cleaved Aca2 from the rest of the sample. The dialyzed sample was centrifuged (15 000 g, 4°C, 5 min) and soluble protein loaded onto an IMAC column. The column was washed with 10 CV binding buffer and 10 CV elution buffer. Cleaved Aca2 was collected in the unbound fraction and peak fractions were pooled and further purified by size-exclusion chromatography using a Superose 12 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare) pre-equilibrated in SEC buffer. Fractions containing Aca2 were pooled and glycerol was added to a final concentration of 5% (v/v). Protein concentrations were determined using the Qubit Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific). Aliquots were snap-frozen using dry ice and ethanol and stored at -80°C.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs)

DNA probes for EMSAs were PCR-amplified using the primers listed in Supplementary Table S2 from the plasmids listed in Supplementary Table S3. Probes were fluorescently labelled with IRDye-700 on their 5′ ends, whereas for binding specificity controls, unlabelled primers of the same sequence were used.

EMSAs involved 20 μl reactions containing 20 mM HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM TCEP, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 μg/μl BSA, 0.01 μg/μl poly(dI•dC), 0.05 μg/ml poly-l-lysine, labelled DNA probe (final concentration 0.25 nM) and purified Aca2 to final concentrations as indicated. For competition assays, excess unlabelled probe (final concentration 50 nM) was incubated with Aca2 for 15 min prior to addition of the labelled probe. All binding reactions were incubated for 15 min at room temperature in the dark. Next, 5 μl loading dye (0.5× TBE (45 mM Tris, pH 8.3, ∼45 mM boric acid and 1 mM EDTA), 34% glycerol (v/v), 0.2% bromophenol blue (w/v)) was added and samples were loaded on 8% polyacrylamide gels (19:1 acrylamide/bis-acrylamide (Bio-Rad), 0.5× TBE, 2.5% (v/v) glycerol, 0.6 mg/ml ammonium persulfate and 0.05% (v/v) tetramethylethylenediamine) which had been pre-run for at least 30 min at 4°C. Gel electrophoresis was performed at 100 V and 4°C in the dark for ∼1 h. DNA was imaged at 700 nm using the LI-COR Odyssey Fc imaging system and Image Studio software. Image Studio was used to quantitate band shifts from at least three independent assays, and dissociation constants were determined using GraphPad Prism (Version 7.00).

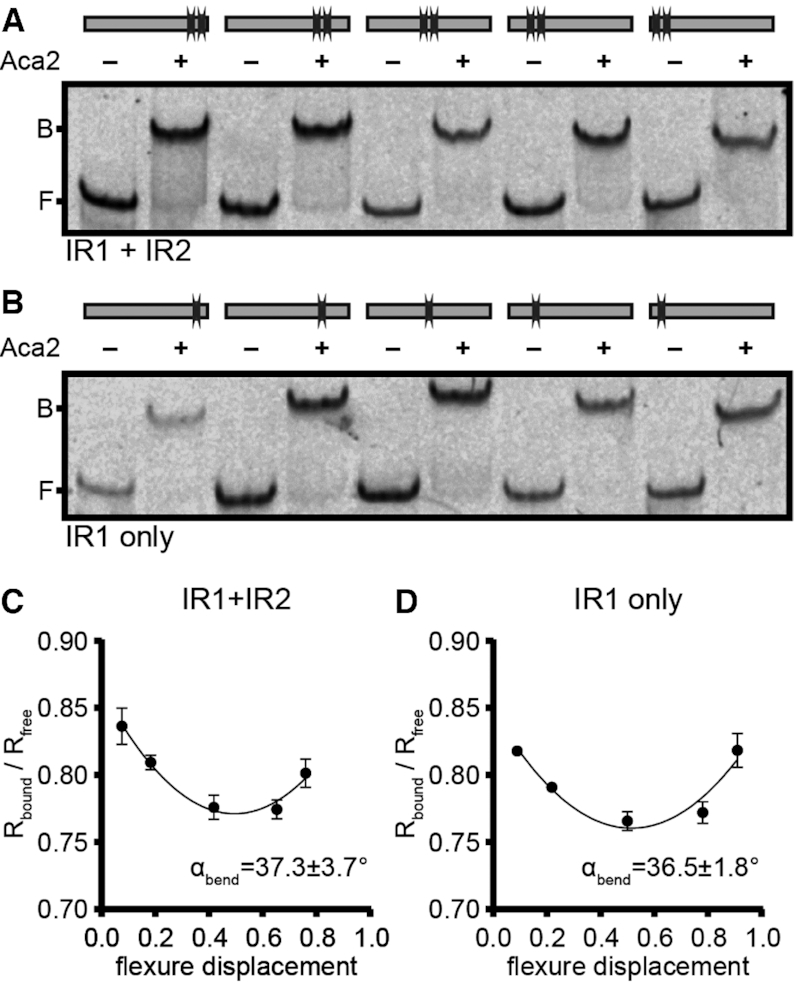

DNA bending assays

DNA bending assays were based on (28). Probes for bending assays were generated by PCR using the IRDye700-labelled oligonucleotides and the templates indicated in Supplementary Table S2. Probes were characterized by varying flexure displacement, defined as the ratio of (a) the distance from the centre of the putative protein binding site to the 5′ end of the probe, and (b) the total length of the probe. The DNA-binding reactions were assembled according to EMSA conditions with 20 nM Aca2 and probe concentrations of 1 nM. After imaging, mobility of shifted and unshifted DNA probes (Rbound and Rfree, respectively) was determined as the distance between the probe and the gel well. The ratio Rbound/Rfree was plotted as a function of flexure displacement, and a quadratic equation of the form y = ax2 + bx + c describing the best-fit curve was used to determine the bending angle according to the formula αbend = cos–1[(2c – a)/2c] = cos–1[(2c + b)/2c], as described in (29). The bending angle was calculated as the mean ± standard deviation of at least three independent DNA bending assays.

RESULTS

The acrIF8–aca2 promoter contains conserved inverted repeats

To elucidate whether Aca proteins autoregulate and also control their associated anti-CRISPR genes, we first searched the acrIF8–aca2 promoter of phage ZF40 for potential protein binding sites. We identified two pairs of inverted repeats (IR1 and IR2) upstream of acrIF8, within the promoter and 5′ UTR, indicative of binding sites for regulatory proteins (Figure 1A). IR1 and IR2 share the same core inverted nucleotides (5′-TTCG-3′) but differ in the sequence and spacing (N6 or N8 for IR1 and IR2, respectively) of the region between these core complementary halves. Interestingly, we found these IRs conserved in most aca2-associated loci that were identified previously (13), and in other aca2-positive species such as Pseudomonas alcaliphila and Edwardsiella piscicida (Figure 1B). Generally, IR1 appears more conserved than IR2, with all examined species displaying near-perfect IR1 symmetry, whereas IR2 symmetry was often disrupted due to some non-complementary nucleotide pairs. We hypothesized that Aca2 might autoregulate the acrlF8–aca2 operon by binding these IRs within the promoter region.

Aca2 represses the acrIF8–aca2 operon

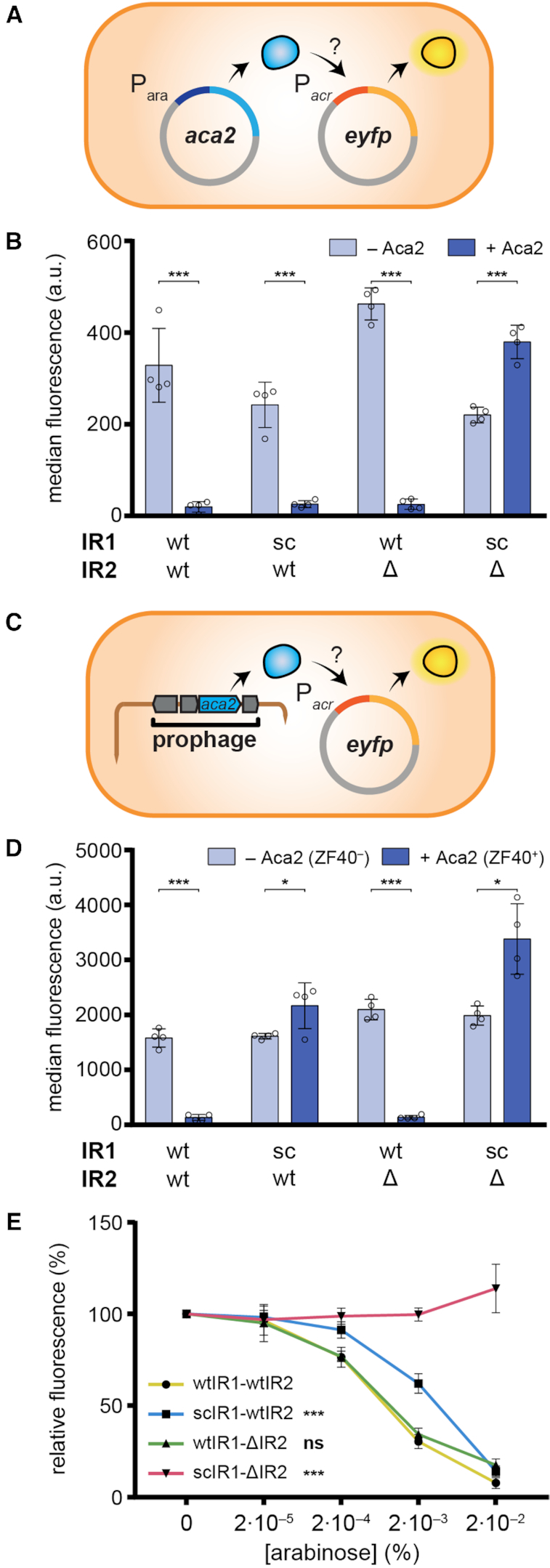

To determine whether Aca2 influences expression from the acrIF8–aca2 locus, we used a plasmid-based fluorescent reporter autoregulation assay in P. carotovorum RC5297, a strain closely related to ZM1 (95.5% average nucleotide identity). RC5297 lacks the ZF40 prophage and therefore endogenous aca2 expression, and will hence hereafter be called Pca ZF40– (Figure 2). The acrIF8–aca2 promoter from phage ZF40 was inserted into an eyfp transcriptional reporter plasmid and aca2 was expressed from a second plasmid under control of the arabinose-inducible araBAD promoter (Figure 2A). In the absence of Aca2, we observed robust expression from the acrIF8–aca2 promoter. This strong promoter activity is consistent with the presence of a predicted perfect consensus -10 sequence (TATAAT) with the optimal spacing of N17 to a -35 sequence (TTGCTT). In agreement, mutation of the predicted -10 sequence abolished activity of the promoter (Supplementary Figure S1A and B). Expression was repressed by Aca2, demonstrating a role for Aca2 in operon repression (Figure 2B). To determine whether the repression was due to Aca2 binding to the inverted repeats, we tested promoter mutants with either IR1 or IR2 sequences scrambled (Supplementary Figure 1A). Scrambling the IR1 site (scIR1) did not affect Aca2 regulation in Pca ZF40– cells (Figure 2B). The scrambled IR2 (scIR2) mutant attenuated expression of the acrIF8–aca2 promoter in the absence of Aca2, preventing analyses of Aca2 regulation (Supplementary Figure S1C, D). To circumvent this effect, we deleted IR2 (ΔIR2), which did not affect basal promoter activity or Aca2-dependent repression (Figure 2B). Therefore, either IR1 or IR2 alone were sufficient for repression in vivo. By contrast, Aca2 was incapable of repressing the double IR mutant, scIR1-ΔIR2.

Figure 2.

Aca2 represses the acrIF8–aca2 operon. (A) Schematic of the plasmid setup for the assay to measure autoregulation of the acrIF8–aca2 promoter by Aca2 in a Pca ZF40– host (Pca RC5297). (B) Activity of acrIF8–aca2 promoter variants in Pca ZF40– in the presence and absence of Aca2, determined as the median eYFP fluorescence. The IR sites were mutated as indicated; sc: scrambled or Δ: deleted. (C) Schematic of the acrIF8–aca2 promoter assay in the ZF40+ strain (Pca lysogen ZM1). (D) Activity of acrIF8–aca2 promoter variants in the Pca ZF40+ strain, determined as the median eYFP fluorescence. The Pca ZF40– control strain lacks aca2 and in the Pca ZF40+ strain aca2 is expressed natively from the ZF40 prophage. (E) Activity of acrIF8–aca2 promoter variants in the Pca ZF40– strain in the presence of different concentrations of arabinose to induce aca2 expression. In (B) and (D), data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of four biological replicates and statistical significance was tested by two-tailed unpaired t-tests (*P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001). In (E), data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of six biological replicates and statistical significance compared to the wtIR1-wtIR2 promoter was tested by two-way ANOVA with Dunnett's Multiple Comparisons Test (***P < 0.001, ns: P > 0.05).

The ZF40 prophage produces sufficient Aca2 to repress the acrIF8–aca2 promoter

Next, we examined Aca2 regulation in the ZF40 lysogen, P. carotovorum str. ZM1 (hereafter Pca ZF40+), by introducing the acrIF8–aca2 promoter reporters in the absence of the aca2 expression plasmids (Figure 2C). We observed strong repression of the wild-type promoter in the presence of the ZF40 prophage, which contains the native aca2 gene, in contrast to the Pca ZF40– control strain (Figure 2D). These data demonstrate that there is basal expression of aca2 from the ZF40 prophage in stable lysogens, and that this is able to repress the acrIF8–aca2 operon. Surprisingly, repression of the acrIF8–aca2 promoter was impaired by disruption of IR1, both IR1 and IR2, but not IR2 alone (Figure 2D). These data contrast the results obtained with our heterologous aca2 regulation assay in the ZF40– strain, where either IR1 or IR2 were sufficient for repression. We hypothesized that IR1 and IR2 have different affinities for Aca2 and that this difference is masked by an increased concentration of Aca2 in the heterologous system. To test this, we performed an arabinose dose-response experiment to generate a range of Aca2 concentrations in the Pca ZF40– autoregulation system (Figure 2E). While the wild-type and ΔIR2 promoters responded similarly to Aca2 abundance, the scIR1 promoter required a higher Aca2 concentration for the same level of repression (Figure 2E). Our results suggest that IR1 is a higher-affinity site than IR2 for Aca2 repression and that in the prophage stage, acrIF8–aca2 repression is predominantly mediated via IR1.

Aca2 binds tightly to an inverted repeat in the acrIF8–aca2 promoter

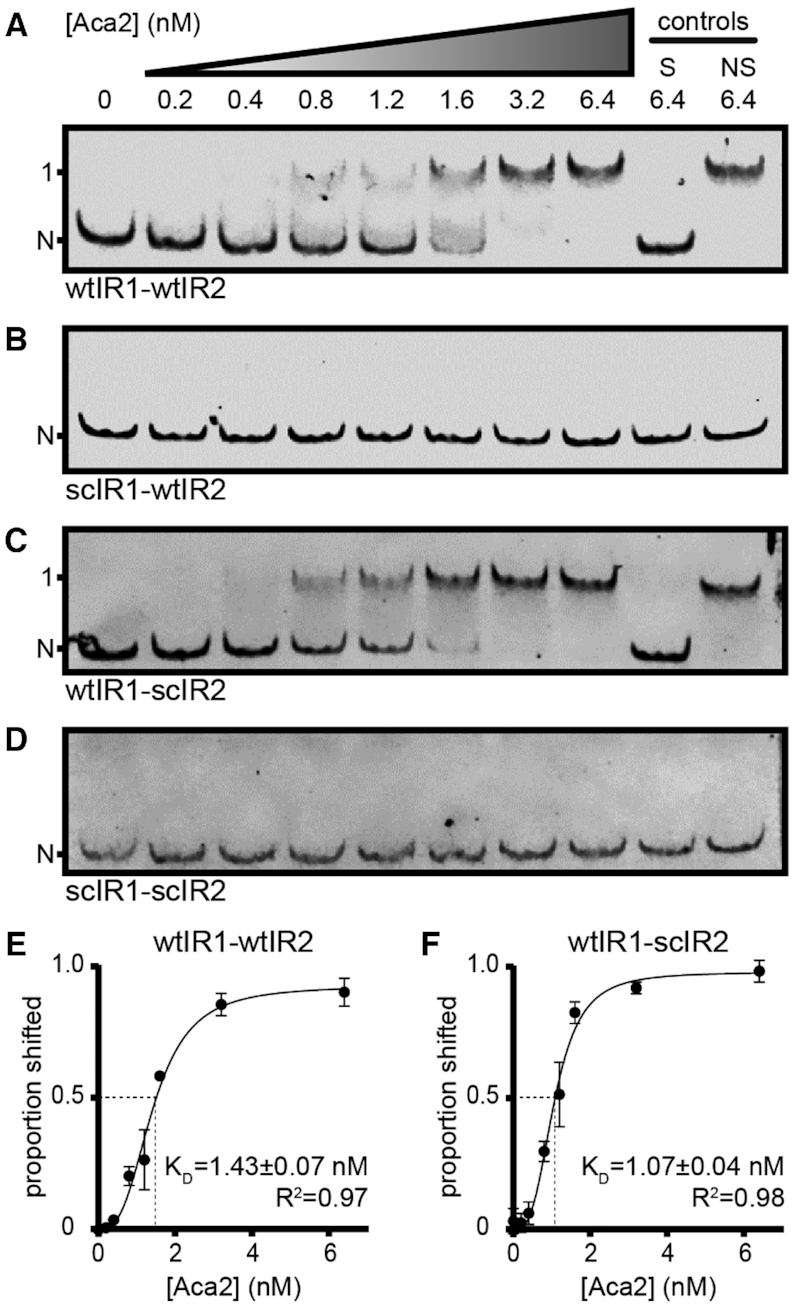

We next investigated whether the repression of the acrIF8–aca2 promoter was due to direct DNA binding by Aca2 to the IRs. We performed electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) using purified Aca2 and fluorescently labelled DNA probes covering 152 bp upstream of the acrIF8 start codon. Upon incubation of Aca2 with the wild-type promoter, a concentration-dependent shift was apparent, demonstrating direct binding between Aca2 and the acrIF8–aca2 promoter DNA (Figure 3A). DNA binding specificity by Aca2 was demonstrated by competition with excess unlabelled DNA of the specific (S) sequence, but not with a non-specific (NS) sequence (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Aca2 binds tightly to IR1 in the acrIF8–aca2 promoter. (A–D) Representative mobility shifts of indicated DNA probes with increasing Aca2 concentrations. Specific and non-specific controls (200-fold excess) are denoted S and NS, respectively. N and 1 indicate non-shifted and single-shifted bands, respectively. (E, F) Dose-response curves of the proportion of shifted probe (± standard deviation) as a function of Aca2 concentration and the resulting apparent dissociation constants (KD) based on three independent assays.

To examine Aca2 binding at the individual IRs, we used probes containing scrambled IR sites. Scrambling IR1 abrogated the Aca2-dependent shift, whereas scrambling IR2 did not, indicating that IR1 is requisite for Aca2 binding in this assay (Figure 3B and C). As expected, scrambling both sites abolished Aca2 binding (Figure 3D). Since our in vivo experiments suggested that Aca2 has a lower affinity for IR2 than IR1, we increased the Aca2 concentration in the EMSA. However, we still did not observe any additional shifts, indicating that IR2 is not bound by Aca2 under these in vitro conditions with up to 128 nM Aca2 (Supplementary Figure S2) or 1000 nM Aca2 (data not shown). Quantification of Aca2 binding to both the wild-type and the wtIR1-scIR2 promoter regions revealed strong DNA binding with 1.43 and 1.07 nM dissociation constants, respectively (Figure 3E and F). These results show that, in vitro, IR1 is essential for high affinity DNA binding between Aca2 and the acrIF8–aca2 promoter, whereas IR2 is dispensable for DNA binding.

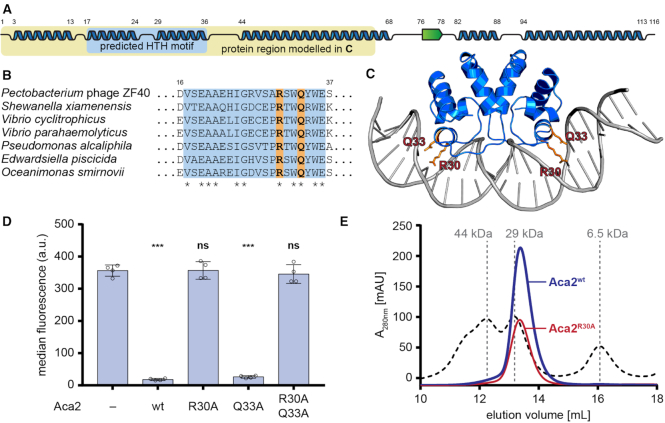

Regulation by Aca2 is mediated by the helix-turn-helix domain

Our data demonstrates that Aca2 functions as a transcriptional repressor by binding to the acrIF8–aca2 promoter. Phyre2 (25) secondary structure predictions suggested the presence of multiple α-helices in the Aca2 sequence, two of which are predicted to constitute the helix-turn-helix (HTH) motif in the N-terminal domain of Aca2 (Figure 4A). Several residues in this region are highly conserved across Aca2 homologs from various species (Figure 4B). We further identified proteins with similarity to Aca2 whose structures were known. The N-terminal domain of Aca2 matched the antitoxin and transcriptional repressor MqsA from E. coli (23% amino acid identity), which binds inverted repeats as a dimer (26). Based on the published structure of MqsA in complex with its DNA template (PDB: 3O9X), we used protein structural homology modelling to generate a model for the N-terminal domain of Aca2 bound to DNA (Figure 4C). In support of our DNA-bound Aca2 model, two residues in the MqsA major HTH recognition helix that contribute to DNA binding (26), N97 and R101, align with the conserved residues R30 and Q33 in Aca2, respectively (Figure 4C). Moreover, mutation of R30, but not Q33, to alanine disrupted Aca2 repression of the acrIF8–aca2 promoter (Figure 4D). During size-exclusion chromatography, wild-type Aca2 eluted at a volume corresponding to a dimer (an Aca2 monomer is ∼13.7 kDa), which was unaffected by the R30A mutation (Figure 4E). Taken together, these findings strongly support that Aca2 is a dimeric HTH transcriptional repressor that binds IRs in the acrIF8–aca2 promoter. Based on the homology with MqsR, we propose that each half of an IR is recognized by each Aca2 subunit.

Figure 4.

Aca2 is a dimeric HTH protein. (A) Predicted secondary structures of Aca2 from phage ZF40, with α-helices displayed as blue ribbons and a β-strand as a green arrow and their amino acid positions indicated by numbers. The predicted HTH motif is highlighted in light blue. The yellow box highlights the part of the protein used for modelling in panel (C). (B) Alignment of Aca2 HTH motifs from various bacterial species, with highly conserved residues indicated by an asterisk. Residues mutated in Aca2 point mutants are highlighted in orange. Numbers indicate amino acid positions in the ZF40 homolog. (C) An Aca2 dimer (region highlighted in panel A) modeled with a DNA template, based on the published structure of MqsA in complex with DNA. The residues R30 and Q33 are highlighted. (D) Median eYFP fluorescence, as measured during a reporter assay, for different Aca2 point mutants. Data presented are the mean ± standard deviation of four biological replicates and statistical significance was calculated by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's Multiple Comparisons Test (***P < 0.001, ns: P > 0.05). (E) SEC elution profile of wild-type Aca2 (blue) and Aca2R30A (red), with size standards indicated by dashed lines for comparison.

Aca2 binding bends the acrIF8–aca2 promoter DNA

DNA binding by MqsA induces a bend in the DNA of approximately 55° (26). Transcriptional repressors commonly bend DNA to interfere with transcription initiation by RNA polymerase (30). To determine whether Aca2 may use a similar mechanism, we measured changes to the acr–aca2 promoter topology by bound Aca2 using a DNA bending assay. The assay uses a series of probes with varying flexure displacement (i.e. with different positions of the Aca2 binding site relative to the centre of the probe). We observed that the magnitude of the DNA shift was dependent on flexure displacement, indicating that Aca2 bends its template upon binding (Figure 5A, B). Indeed, we determined the bending angle of the IR1+IR2 probe to be ∼37.5° (Figure 5C). Using probes containing only IR1 led to a similar bending angle (∼36.6°), further supporting the notion that IR1 is the only DNA site bound by Aca2 in these in vitro assays (Figure 5D). In conclusion, we show that binding of Aca2 to IR1 involves topological changes in the DNA template, which we predict to be an important factor in transcriptional repression.

Figure 5.

Aca2 binding bends the acrIF8–aca2 promoter DNA. (A, B) Mobility shifts of DNA probes with varying flexure displacement (as indicated by the binding site schematics) in the absence or presence of Aca2. B and F indicate the positions of bound and free DNA, respectively. (C, D) DNA bending curves used to determine bending angles (αbend) ± standard deviation based on the difference of mobility for bound and unbound DNA (Rbound/Rfree) at varying flexure displacements of the probes, based on three independent replicates.

DISCUSSION

Genes encoding Aca proteins are frequently associated with anti-CRISPR genes, and their conservation implies that they fulfil an important role in Acr function. Here we show that the Aca2 dimer is involved in repression of the anti-CRISPR operon through two inverted repeat binding sites, leading to the downregulation of both the anti-CRISPR and Aca2 itself. Based on our data, we propose the following model. The acrIF8–aca2 promoter is strong, with promoter elements close to the consensus for the housekeeping sigma factor (σ70). In our model, this promoter enables ZF40 to produce large quantities of anti-CRISPR immediately upon infection that are sufficient to suppress the host CRISPR-Cas system and allow viral replication and host cell lysis, or lysogeny. Note that neither AcrIF8 nor Aca2 are components of the ZF40 virion (31) and therefore must be produced upon genome injection. We predict that a constantly high rate of Acr production could cause a fitness cost and be toxic, which is supported by toxicity observed upon Acr overexpression (13). Moreover, since prophage success is tied to lysogen survival, significant CRISPR-Cas immunosuppression is likely to be unfavourable by reducing defence against other (un)related phages (11,12,32). Therefore, we propose that it is beneficial for the prophage to repress the anti-CRISPR operon once sufficient Acr has inactivated the CRISPR-Cas complexes. In support of this model, Aca2 proteins are typically encoded as the second gene in acr operons. Therefore, a pulse of Acr will be produced, followed by production of Aca, which we show is able to reduce expression of the operon. We predict that the levels of Aca2 relative to AcrIF8 will accumulate more slowly, due to a weaker ribosome-binding site for aca2 compared with acrIF8, which helps establish an initial Acr pulse (Supplementary Figure S3). Importantly, we show that in ZF40 lysogens Aca2 activity is detectable, albeit low compared to the plasmid overexpression system, which means that the prophage does not entirely shut off the anti-CRISPR properties. This suggests that anti-CRISPR levels might be fine-tuned to balance the benefits of the host maintaining some CRISPR-Cas activity (preventing superinfection) against potential recognition of the integrated prophage by existing spacers.

The two IRs in the acrIF8–aca2 promoter responded to different levels of the Aca2 dimer. Each monomer of Aca2 is predicted to bind one half-site of the IR and the spacing between the IR half-sites is likely to influence the binding strength. Aca2 binds to IR1 with a high affinity and induces bending by 37°, directly blocking the -35 and -10 promoter region. In contrast, IR2 does not seem to play a role for repression once lysogeny is established but can mediate repression at higher Aca2 concentrations. This suggests that IR2 might function shortly after phage infection when expression of the acrIF8–aca2 operon is presumably high, potentially allowing modulation of anti-CRISPR expression in the transition between infection and establishment of the prophage. Furthermore, based on our in vitro data, it is possible that an additional factor is required for IR2 to be recognized by Aca2. According to the predicted location of the transcriptional start site (Figure 1A), IR2 is part of the 5′ UTR of the acrIF8–aca2 transcript. As such, the palindromic sequence could create a hairpin loop and have a posttranscriptional role in fine-tuning anti-CRISPR expression. In any case, the roles of the two inverted repeats are likely to be similar across many aca2-positive strains, because the symmetry and the spacing between the half-sites of the individual IRs are largely conserved. In conclusion, we have revealed the DNA binding mechanism of repression by the Aca2 protein in the control of anti-CRISPR expression. Based on the common occurrence of helix-turn-helix motifs in Aca proteins, our model for the Aca2 regulatory mechanism is likely to be conserved across other Aca proteins.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Natalia Korol and Fedor Tovkach (National Academy of Science, Ukraine) for providing P. carotovorum strains ZM1 and RC5297, and Alan Davidson (University of Toronto) and members of the Fineran laboratory for helpful discussions.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

Marsden Fund, Royal Society of New Zealand (to P.C.F.); N.B. and L.M.S. were funded by University of Otago Doctoral Scholarships. Funding for open access charge: Marsden Fund, Royal Society of New Zealand.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Dy R.L., Richter C., Salmond G.P.C., Fineran P.C.. Remarkable mechanisms in microbes to resist phage infections. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2014; 1:307–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rostøl J.T., Marraffini L.. (Ph)ighting phages: how bacteria resist their parasites. Cell Host Microbe. 2019; 25:184–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Koonin E.V., Makarova K.S.. Origins and evolution of CRISPR-Cas systems. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2019; 374:20180087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barrangou R., Fremaux C., Deveau H., Richards M., Boyaval P., Moineau S., Romero D.A., Horvath P.. CRISPR provides acquired resistance against viruses in prokaryotes. Science. 2007; 315:1709–1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jackson S.A., McKenzie R.E., Fagerlund R.D., Kieper S.N., Fineran P.C., Brouns S.J.J.. CRISPR-Cas: adapting to change. Science. 2017; 356:eaal5056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brouns S.J.J., Jore M.M., Lundgren M., Westra E.R., Slijkhuis R.J.H., Snijders A.P.L., Dickman M.J., Makarova K.S., Koonin E.V., van der Oost J.. Small CRISPR RNAs guide antiviral defense in prokaryotes. Science. 2008; 321:960–964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bondy-Denomy J., Pawluk A., Maxwell K.L., Davidson A.R.. Bacteriophage genes that inactivate the CRISPR/Cas bacterial immune system. Nature. 2013; 493:429–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pawluk A., Davidson A.R., Maxwell K.L.. Anti-CRISPR: discovery, mechanism and function. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018; 16:12–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bondy-Denomy J. Protein inhibitors of CRISPR-Cas9. ACS Chem. Biol. 2018; 13:417–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shehreen S., Chyou T., Fineran P.C., Brown C.M.. Genome-wide correlation analysis suggests different roles of CRISPR-Cas systems in the acquisition of antibiotic resistance genes in diverse species. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2019; 374:20180384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Landsberger M., Gandon S., Meaden S., Rollie C., Chevallereau A., Chabas H., Buckling A., Westra E.R., van Houte S.. Anti-CRISPR phages cooperate to overcome CRISPR-Cas immunity. Cell. 2018; 174:908–916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Borges A.L., Zhang J.Y., Rollins M.F., Osuna B.A., Wiedenheft B., Bondy-Denomy J.. Bacteriophage cooperation suppresses CRISPR-Cas3 and Cas9 immunity. Cell. 2018; 174:917–925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pawluk A., Staals R.H.J., Taylor C., Watson B.N.J., Saha S., Fineran P.C., Maxwell K.L., Davidson A.R.. Inactivation of CRISPR-Cas systems by anti-CRISPR proteins in diverse bacterial species. Nat. Microbiol. 2016; 1:16085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pawluk A., Bondy-Denomy J., Cheung V.H.W., Maxwell K.L., Davidson A.R.. A new group of phage anti-CRISPR genes inhibits the type I-E CRISPR-Cas system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. MBio. 2014; 5:e00896-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pawluk A., Amrani N., Zhang Y., Garcia B., Hidalgo-Reyes Y., Lee J., Edraki A., Shah M., Sontheimer E.J., Maxwell K.L. et al.. Naturally occurring off-switches for CRISPR-Cas9. Cell. 2016; 167:1829–1838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lee J., Mir A., Edraki A., Garcia B., Amrani N., Lou H.E., Gainetdinov I., Pawluk A., Ibraheim R., Gao X.D. et al.. Potent Cas9 inhibition in bacterial and human cells by AcrIIC4 and AcrIIC5 anti-CRISPR proteins. MBio. 2018; 9:e02321-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Marino N.D., Zhang J.Y., Borges A.L., Sousa A.A., Leon L.M., Rauch B.J., Walton R.T., Berry J.D., Joung J.K., Kleinstiver B.P. et al.. Discovery of widespread type I and type V CRISPR-Cas inhibitors. Science. 2018; 362:240–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Comeau A.M., Tremblay D., Moineau S., Rattei T., Kushkina A.I., Tovkach F.I., Krisch H.M., Ackermann H.-W.. Phage morphology recapitulates phylogeny: the comparative genomics of a new group of myoviruses. PLoS One. 2012; 7:e40102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tovkach F.I. Study of Erwinia carotovora phage resistance with the use of temperate bacteriophage ZF40. Microbiology. 2002; 71:72–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fagerlund R.D., Wilkinson M.E., Klykov O., Barendregt A., Pearce F.G., Kieper S.N., Maxwell H.W.R., Capolupo A., Heck A.J.R., Krause K.L. et al.. Spacer capture and integration by a type I-F Cas1–Cas2-3 CRISPR adaptation complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2017; 114:E5122–E5128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chowdhury S., Carter J., Rollins M.F., Golden S.M., Jackson R.N., Hoffmann C., Nosaka L., Bondy-Denomy J., Maxwell K.L., Davidson A.R. et al.. Structure reveals mechanisms of viral suppressors that intercept a CRISPR RNA-guided surveillance complex. Cell. 2017; 169:47–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rollins M.F., Chowdhury S., Carter J., Golden S.M., Miettinen H.M., Santiago-Frangos A., Faith D., Lawrence C.M., Lander G.C., Wiedenheft B.. Structure reveals mechanism of CRISPR-RNA-guided nuclease recruitment and anti-CRISPR viral mimicry. Mol. Cell. 2019; 74:132–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jackson S.A., Birkholz N., Malone L.M., Fineran P.C.. Imprecise spacer acquisition generates CRISPR-Cas immune diversity through primed adaptation. Cell Host Microbe. 2019; 25:250–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Madeira F., Park Y.mi, Lee J., Buso N., Gur T., Madhusoodanan N., Basutkar P., Tivey A.R.N., Potter S.C., Finn R.D. et al.. The EMBL-EBI search and sequence analysis tools APIs in 2019. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019; 47:W636–W641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kelley L.A., Mezulis S., Yates C.M., Wass M.N., Sternberg M.J.E.. The Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling, prediction and analysis. Nat. Protoc. 2015; 10:845–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Brown B.L., Wood T.K., Peti W., Page R.. Structure of the Escherichia coli Antitoxin MqsA (YgiT/b3021) bound to its gene promoter reveals extensive domain rearrangements and the specificity of transcriptional regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 2011; 286:2285–2296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yoon S.H., Ha S., Lim J., Kwon S., Chun J.. A large-scale evaluation of algorithms to calculate average nucleotide identity. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2017; 110:1281–1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hampton H.G., Jackson S.A., Fagerlund R.D., Vogel A.I.M., Dy R.L., Blower T.R., Fineran P.C.. AbiEi binds cooperatively to the Type IV abiE toxin–antitoxin operator via a positively-charged surface and causes DNA bending and negative autoregulation. J. Mol. Biol. 2018; 430:1141–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Papapanagiotou I., Streeter S.D., Cary P.D., Kneale G.G.. DNA structural deformations in the interaction of the controller protein C.AhdI with its operator sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007; 35:2643–2650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pérez-Martín J., Rojo F., de Lorenzo V.. Promoters responsive to DNA bending: a common theme in prokaryotic gene expression. Microbiol. Rev. 1994; 58:268–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Korol N., Van den Bossche A., Romaniuk L., Noben J.-P., Lavigne R., Tovkach F.. Experimental evidence for proteins constituting virion components and particle morphogenesis of bacteriophage ZF40. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2016; 363:fnw042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Borges A.L., Davidson A.R., Bondy-Denomy J.. The discovery, mechanisms, and evolutionary impact of Anti-CRISPRs. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2017; 4:37–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.