Abstract

Background:

Given high on-treatment mortality in heart failure (HF), identifying molecular pathways that underlie adverse cardiac remodeling may offer novel biomarkers and therapeutic avenues. Circulating extracellular RNAs (ex-RNAs) regulate important biological processes and are emerging as biomarkers of disease, but less is known about their role in the acute setting, particularly in the setting of HF.

Methods:

We examined the ex-RNA profiles of 296 acute coronary syndrome (ACS) survivors enrolled in the Transitions, Risks, and Actions in Coronary Events Center for Outcomes Research and Education Cohort. We measured 374 ex-RNAs selected a priori, based on previous findings from a large population study. We employed a two-step, mechanism-driven approach to identify ex-RNAs associated with echocardiographic phenotypes (left ventricular [LV] ejection fraction, LV mass, LV end-diastolic volume, left atrial [LA] dimension, and LA volume index) then tested relations of these ex-RNAs with prevalent HF (N=31, 10.5%). We performed further bioinformatics analysis of microRNA (miRNAs) predicted targets’ genes ontology categories and molecular pathways.

Results:

We identified 44 ex-RNAs associated with at least one echocardiographic phenotype associated with HF. Of these 44 exRNAs, miR-29-3p, miR-584-5p, and miR-1247-5p were also associated with prevalent HF. The three microRNAs were implicated in the regulation p53 and transforming growth factor-β signaling pathways and predicted to be involved in cardiac fibrosis and cell death; miRNA predicted targets were enriched in gene ontology categories including several involving the extracellular matrix and cellular differentiation.

Conclusions:

Among ACS survivors, we observed that miR-29-3p, miR-584-5p, and miR-1247-5p were associated with both echocardiographic markers of cardiac remodeling and prevalent HF.

Relevance for Patients:

miR-29c-3p, miR-584-5p, and miR-1247-5p were associated with echocardiographic phenotypes and prevalent HF and are potential biomarkers for adverse cardiac remodeling in HF.

Keywords: Extracellular RNAs, Heart failure, Cardiac remodelling, Echocardiographic phenotypes, Biomarkers

1. Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is a rapidly rising public health problem that affects more than 37 million people worldwide with high morbidity and mortality [1,2]. It is a systemic disease, in which structural, neurohumoral, cellular, and molecular mechanisms that maintain physiological functions become pathological [3,4]. Together, these dysfunctional processes lead to increased cardiac remodeling, circulation redistribution, and volume overload [5]. Key to prevention and treatment of HF is the understanding of maladaptive cellular responses that lead to this disease. In particular, there is an urgent need to better understand the molecular mechanisms by which this pathological response is coordinated.

Small noncoding RNAs regulate signaling pathways that dictate physiological as well as pathological responses to stress. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small noncoding RNAs that modulate cardiac differentiation, proliferation, maturation, and pathological remodeling responses to environmental stimuli [6,7]. Extracellular RNAs (ex-RNAs) are endogenous small noncoding RNAs that exist in the plasma with remarkable stability and may reflect cellular states and cellular communication [8]. Although there are several reports implicating ex-RNAs in HF [9-11], the observations are biased due to the study of only a limited number of miRNAs. In a broader and unbiased screen of circulating ex-RNAs, specific miRNAs were found to be expressed in the setting of HF; however, the expression of ex-RNAs in acute clinical settings remains unknown [12]. Data illustrating the expression of plasma ex-RNAs in the acute clinical setting could provide relevant ex-RNA biomarkers and shed light on the molecular mechanisms underlying clinical HF.

Transthoracic echocardiography is a useful noninvasive technique to assess cardiac function and for prognostication of HF [13]. Cardiac remodeling as measured by enlarged cardiac chamber size, lower left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) or higher LV mass (LV mass) is associated with the incidence of HF [14-16]. Furthermore, changes in echocardiographic phenotypes are associated with rapid progression of the disease [17]. The high utility of echocardiographic parameters in the evaluation and prognostication of HF is due to its ability to define structural processes underpinning pathological cardiac remodeling. Although echocardiographic phenotypes associated with HF are well known, the molecular basis for pathological cardiac remodeling is less understood.

To better understand the signaling pathways activated in HF, we examined ex-RNAs relevant to cardiac remodeling as well as clinical HF in a hospitalized patient population. We employed a two-step analysis model that leveraged echocardiographic phenotypes associated with cardiac remodeling and prevalent HF in acute coronary syndrome (ACS) survivors from the Transitions, Risks, and Action in Coronary Events Center for Outcomes Research and Education (TRACE-CORE) cohort. In this study, we applied a mechanism-based framework to identify promising candidate ex-RNAs in the acute clinical setting to shed light on the molecular processes that drive HF.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Study population

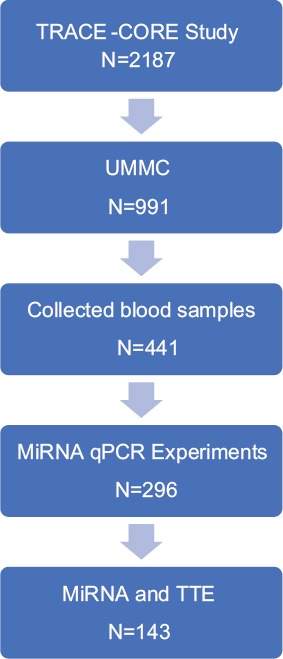

Details of the design, participant recruitment, interview processes, and medical record abstraction procedures used in TRACE-CORE study have previously been reported [18,19]. In brief, TRACE-CORE used a 6-site prospective cohort design to follow 2187 patients discharged after an ACS hospitalization from April 2011 to May 2013 (Figure 1). Sites in Central Massachusetts included two academic teaching hospitals and a large community hospital. The other sites included two hospitals affiliated with a managed care organization in Atlanta, GA, and an academic medical center. At the sites in Central Massachusetts, 411 blood samples were collected, processed as described previously, and plasma was stored in −80°C [8,20]. Of the plasma collected, 296 were of sufficient quality for RNA extraction and qPCR experiment. The institutional review boards at each participating recruitment site approved this study. All participants provided written informed consent.

Figure 1. Sample selection for the analyses from the Transitions, Risks, and Action in Coronary Events Center for Outcomes Research and Education study.

2.2 Ascertainment of HF

Trained study staff abstracted participants’ baseline demographic, clinical, laboratory, and electrocardiographic data and in-hospital clinical complications from available hospital medical records. Comorbidities present at the time of hospital admission were identified from each participant’s admission history and physical examination. Any patient with documentation of HF by a trained medical provider was considered as having prevalent HF.

2.3 ex-RNA selection and profiling

As part of a transcriptomic profiling study, we collected venous blood samples from 296 TRACE-CORE participants’ in-hospital admission. The methods for processing blood samples, storing plasma samples, and RNA isolation have previously been described [20]. We have previously published methods for quantification of ex-RNAs, which included miRNAs and small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs) [8]. ex-RNAs were selected a priori, based on previously generated data from the Framingham Heart Study [8]. The ex-RNA profiling of plasma was performed at the High-Throughput Gene Expression and Biomarker Core Laboratory at the University of Massachusetts Medical School. ex-RNA levels reported in quantification cycles (Cq) where higher Cq values reflect lower ex-RNA levels. This approach yielded 331 miRNAs and 43 snoRNAs. Full details of ex-RNA profiling are described in supplementary information (Supplementary Table 1).

2.4 Echocardiographic measurements

Complete two-dimensional (2D) echocardiograms were performed during hospitalization. Ejection fraction, 2D volumes, and linear dimensions were measured according to ASE guidelines [21]. We quantified LV mass, LVEF, LV end diastolic (LVED) volume, left atrial (LA) volume, and LA volume index (LAVI) (Table 1). In brief, Simpson’s biplane summation of disks method was used to make measurements in apical 2-chamber and 4-chamber views. LV mass was calculated by LV mass=0.8 (1.04[LVID+PWTd+SWTd]3–[LVID]3)+0.6g [22].

Table 1. Characteristics of TRACE-CORE participants included in the analytic sample.

| Characteristics | No heart failure (n=265) | Heart Failure (N=31) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean SD | 63±11 | 68±13 | <0.01 |

| Female | 34% | 23% | 0.19 |

| Race (Caucasian) | 96% | 100% | 0.32 |

| Height (inches) | 69±14 | 68±5 | 0.29 |

| Weight (lbs) | 187±46 | 191±57 | 0.66 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 29±6 | 30±5 | 0.79 |

| Social history | |||

| Education | |||

| High school | 38% | 58% | |

| Some college | 28% | 26% | <0.01 |

| College | 34% | 16% | |

| Married | 68% | 52% | 0.08 |

| Risk factors | |||

| Hyperlipidemia | 67% | 77% | 0.25 |

| Myocardial infarction | 25% | 74% | <0.001 |

| Anginal pectoris/CHD | 23% | 67% | <0.001 |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 28% | 32% | 0.65 |

| Stroke/TIA | 2% | 3% | 0.64 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 7% | 29% | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 68% | 90% | <0.01 |

| Heart failure symptoms | |||

| Angina | 71% | 68% | 0.74 |

| Dyspnea | 37% | 52% | 0.11 |

| Seattle angina questionnaire | |||

| Physical limitation | 83.9±21.6 | 64.7±28.2 | <0.01 |

| Angina stability | 43.1±27.4 | 44.6±31.9 | 0.81 |

| Angina frequency | 75.4±23.7 | 68.3±22.8 | 0.12 |

| Treatment satisfaction | 94±11.5 | 91.7±9.9 | 0.30 |

| Quality of life | 64.8±25.9 | 56.3±27.5 | 0.09 |

| Admission medications | |||

| Aspirin | 45% | 81% | <0.001 |

| Beta-blocker | 38% | 87% | <0.001 |

| ACEI or ARB | 36% | 71% | <0.001 |

| Statin | 56% | 84% | <0.01 |

| Plavix | 12% | 26% | 0.06 |

| Coumadin | 4% | 26% | <0.001 |

| Physical activity | |||

| No physical activity | 59% | 77% | |

| <150 min/week | 16% | 13% | 0.08 |

| >150 min/week | 25% | 10% | |

| Acute coronary syndrome category | |||

| ST-elevation myocardial infarction | 28% | 10% | <0.05 |

| Physiological factors | |||

| Heart rate (beats per minute) | 79±21 | 84±25 | 0.17 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 141±24 | 129±29 | <0.01 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 80±17 | 70±14 | <0.01 |

| Respiratory rate (breaths per minute) | 18±4 | 19±3 | 0.51 |

| Electrocardiogram | |||

| QRS duration | 95±18 | 120±34 | <0.01 |

| PR interval | 164±30 | 182±25 | <0.01 |

| Lab values | |||

| Troponin peak | 25.8±36.7 | 6.0±17.1 | <0.001 |

| Total cholesterol | 175.4±46.1 | 130.1±36.2 | <0.01 |

| Brain natriuretic peptide | 581.8±846.3 | 758.7±665.9 | 0.55 |

| Creatinine | 1.1±0.4 | 1.8±1.0 | <0.01 |

| Hemoglobin | 11.7±2.2 | 10.8±2.2 | <0.05 |

| Sodium | 136±3 | 135±4 | 0.32 |

| Echocardiographic phenotype* | |||

| LV ejection fraction | 53.7±13.0 | 45.0±8.8 | 0.07 |

| LV mass | 180.0±58.1 | 230.3±77.0 | <0.05 |

| LAVI=LAVavg/BSA | 23.0±8.9 | 32.0±9.0 | <0.01 |

| LA volume | 45.7±19.3 | 64.2±24.8 | <0.01 |

| LV end diastolic volume | 83.5±38.3 | 132±51.4 | <0.01 |

CHD: Coronary heart disease, TIA: Transient ischemic attack, ACEi: Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, ARB: Angiotensin II receptor blockers, LV: Left ventricle, LA: Left atrium, LAVI: Left atrial volume index, LAVavg/BSA: Average left atrial volume/body surface area.

Echocardiographic phenotypes were characterized in a subset of patients (n=143) where TTE were available, TRACE-CORE: Transitions, Risks, and Actions in Coronary Events Center for Outcomes Research and Education

2.5 Statistical analysis

A two-step analysis model was used to leverage echocardiographic phenotypes to identify candidate ex-RNAs and then examining ex-RNAs identified and prevalent HF. In Step 1, we examined the relations between ex-RNAs with one or more echocardiographic phenotypes (Table 2, Supplementary Table 2). In Step 2, we examined the associations of ex-RNAs identified from Step 1 with prevalent HF (Table 3). Of note, the number of participants in each step differed as we did not have echocardiographic data available for all participants with plasma ex-RNA data. There are 143 cases with both ex-RNA and echocardiographic data in our TRACE-CORE cohort (Figure 1). We used this group to determine the ex-RNAs significantly related to one or more echo parameters. Using this significant list of ex-RNAs, we queried for a relationship with prevalent HF on the full 296 cases with ex-RNA data.

Table 2. ex-RNAs associated with echocardiographic phenotypes.

| ex-RNA | No heart failure | Heart failure | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean (1/Cq) | Median (1/Cq) | Std. Dev | N | Mean (1/Cq) | Median (1/Cq) | Standard deviation | |

| hsa_miR_10a_5p | 73 | 0.0526 | 0.0490 | 0.0216 | 10 | 0.0623 | 0.0484 | 0.0449 |

| hsa_miR_10b_5p | 111 | 0.0529 | 0.0519 | 0.0064 | 13 | 0.0531 | 0.0539 | 0.0036 |

| hsa_miR_1246 | 263 | 0.0699 | 0.0689 | 0.0079 | 31 | 0.0695 | 0.0691 | 0.0053 |

| hsa_miR_1247_5p | 198 | 0.0533 | 0.0513 | 0.0146 | 25 | 0.0500 | 0.0496 | 0.0022 |

| hsa_miR_1271_5p | 8 | 0.0894 | 0.0522 | 0.0707 | 1 | 0.0458 | 0.0458 | . |

| hsa_miR_142_5p | 153 | 0.0548 | 0.0540 | 0.0129 | 15 | 0.0541 | 0.0517 | 0.0105 |

| hsa_miR_144_5p | 93 | 0.0538 | 0.0500 | 0.0340 | 9 | 0.0493 | 0.0495 | 0.0014 |

| hsa_miR_148b_3p | 192 | 0.0540 | 0.0537 | 0.0045 | 24 | 0.0528 | 0.0518 | 0.0039 |

| hsa_miR_152_3p | 118 | 0.0544 | 0.0528 | 0.0153 | 12 | 0.0546 | 0.0555 | 0.0038 |

| hsa_miR_17_3p | 39 | 0.0570 | 0.0484 | 0.0458 | 3 | 0.0484 | 0.0472 | 0.0028 |

| hsa_miR_185_3p | 12 | 0.0808 | 0.0470 | 0.0785 | 1 | 0.0457 | 0.0457 | . |

| hsa_miR_186_5p | 108 | 0.0495 | 0.0493 | 0.0027 | 14 | 0.0495 | 0.0494 | 0.0024 |

| hsa_miR_190a_3p | 30 | 0.0548 | 0.0482 | 0.0259 | 0 | . | . | . |

| hsa_miR_200b_3p | 40 | 0.0543 | 0.0476 | 0.0258 | 4 | 0.0716 | 0.0636 | 0.0297 |

| hsa_miR_210_3p | 65 | 0.0484 | 0.0481 | 0.0021 | 4 | 0.0471 | 0.0470 | 0.0011 |

| hsa_miR_2110 | 63 | 0.0493 | 0.0483 | 0.0072 | 9 | 0.0487 | 0.0480 | 0.0024 |

| hsa_miR_212_3p | 18 | 0.0596 | 0.0464 | 0.0517 | 2 | 0.0465 | 0.0465 | 0.0011 |

| hsa_miR_224_5p | 90 | 0.0491 | 0.0484 | 0.0030 | 8 | 0.0492 | 0.0495 | 0.0026 |

| hsa_miR_29b_3p | 106 | 0.0511 | 0.0492 | 0.0148 | 5 | 0.0486 | 0.0487 | 0.0019 |

| hsa_miR_29c_3p | 157 | 0.0517 | 0.0512 | 0.0035 | 15 | 0.0497 | 0.0489 | 0.0035 |

| hsa_miR_29c_5p | 262 | 0.0589 | 0.0612 | 0.0057 | 31 | 0.0570 | 0.0545 | 0.0064 |

| hsa_miR_337_3p | 54 | 0.0540 | 0.0493 | 0.0212 | 1 | 0.0540 | 0.0540 | . |

| hsa_miR_342_5p | 25 | 0.0479 | 0.0474 | 0.0025 | 4 | 0.0860 | 0.0460 | 0.0802 |

| hsa_miR_34a_3p | 44 | 0.0481 | 0.0477 | 0.0038 | 5 | 0.0481 | 0.0473 | 0.0018 |

| hsa_miR_424_3p | 15 | 0.0618 | 0.0481 | 0.0539 | 1 | 0.0480 | 0.0480 | . |

| hsa_miR_425_5p | 67 | 0.0511 | 0.0494 | 0.0086 | 7 | 0.0541 | 0.0484 | 0.0117 |

| hsa_miR_4446_3p | 253 | 0.0577 | 0.0605 | 0.0067 | 29 | 0.0554 | 0.0523 | 0.0065 |

| hsa_miR_450b_5p | 36 | 0.0630 | 0.0482 | 0.0414 | 5 | 0.0501 | 0.0504 | 0.0042 |

| hsa_miR_454_3p | 51 | 0.0601 | 0.0487 | 0.0342 | 3 | 0.0494 | 0.0479 | 0.0031 |

| hsa_miR_4770 | 34 | 0.0730 | 0.0495 | 0.0497 | 4 | 0.0475 | 0.0469 | 0.0023 |

| hsa_miR_494_3p | 26 | 0.0571 | 0.0476 | 0.0323 | 2 | 0.0598 | 0.0598 | 0.0146 |

| hsa_miR_497_5p | 62 | 0.0509 | 0.0491 | 0.0085 | 7 | 0.0494 | 0.0490 | 0.0031 |

| hsa_miR_532_5p | 39 | 0.0591 | 0.0477 | 0.0377 | 2 | 0.0801 | 0.0801 | 0.0440 |

| hsa_miR_545_5p | 12 | 0.0850 | 0.0497 | 0.0636 | 0 | . | . | . |

| hsa_miR_548d_3p | 32 | 0.0475 | 0.0472 | 0.0014 | 2 | 0.0481 | 0.0481 | 0.0009 |

| hsa_miR_584_5p | 159 | 0.0537 | 0.0510 | 0.0284 | 22 | 0.0492 | 0.0487 | 0.0024 |

| hsa_miR_590_3p | 20 | 0.0503 | 0.0486 | 0.0058 | 0 | . | . | . |

| hsa_miR_596 | 13 | 0.0480 | 0.0480 | 0.0014 | 1 | 0.0474 | 0.0474 | . |

| hsa_miR_642a_5p | 16 | 0.1061 | 0.0972 | 0.0882 | 1 | 0.0479 | 0.0479 | . |

| hsa_miR_656_3p | 203 | 0.0587 | 0.0613 | 0.0078 | 22 | 0.0558 | 0.0547 | 0.0088 |

| hsa_miR_6803_3p | 41 | 0.0493 | 0.0483 | 0.0076 | 5 | 0.0990 | 0.0467 | 0.1154 |

| hsa_miR_877_3p | 71 | 0.0523 | 0.0504 | 0.0135 | 10 | 0.0562 | 0.0518 | 0.0159 |

| hsa_miR_885_5p | 67 | 0.0526 | 0.0486 | 0.0187 | 8 | 0.0641 | 0.0480 | 0.0350 |

| hsa_miR_9_3p | 78 | 0.0510 | 0.0498 | 0.0054 | 8 | 0.0558 | 0.0518 | 0.0137 |

Table 3. miRNAs significantly related to prevalent HF.

| miRNA | n | Mean | Std | Estimate | Standard error | Prob Chi-square | Odds ratio | Lower CL | Upper CL | RawP value | FDRP value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hsa_miR_1247_5p | 223 | 19.3333 | 1.87668 | 0.4849 | 0.209 | 0.0203 | 1.624 | 1.078 | 2.446 | 0.0203 | 0.0485 |

| hsa_miR_125b_5p | 126 | 20.0642 | 1.00202 | 1.0689 | 0.4716 | 0.0234 | 2.912 | 1.156 | 7.34 | 0.0234 | 0.0485 |

| hsa_miR_17_5p | 207 | 19.2059 | 1.49941 | 0.3744 | 0.1849 | 0.0429 | 1.454 | 1.012 | 2.089 | 0.0429 | 0.0485 |

| hsa_miR_181a_3p | 216 | 19.0163 | 1.53413 | 0.587 | 0.2012 | 0.0035 | 1.799 | 1.212 | 2.668 | 0.0035 | 0.0185 |

| hsa_miR_197_3p | 237 | 19.8007 | 1.09519 | 0.454 | 0.2105 | 0.031 | 1.575 | 1.042 | 2.379 | 0.031 | 0.0485 |

| hsa_miR_1_3p | 92 | 19.8936 | 2.46961 | 1.3026 | 0.6502 | 0.0451 | 3.679 | 1.029 | 13.158 | 0.0451 | 0.0485 |

| hsa_miR_200c_3p | 31 | 20.0822 | 3.42561 | -1.0268 | 0.4689 | 0.0285 | 0.358 | 0.143 | 0.898 | 0.0285 | 0.0485 |

| hsa_miR_222_3p | 221 | 18.9489 | 1.42712 | 0.3672 | 0.1803 | 0.0417 | 1.444 | 1.014 | 2.056 | 0.0417 | 0.0485 |

| hsa_miR_26a_5p | 261 | 17.5297 | 1.77419 | 0.3637 | 0.118 | 0.002 | 1.439 | 1.142 | 1.813 | 0.002 | 0.0185 |

| hsa_miR_26b_5p | 275 | 17.6456 | 1.65162 | 0.376 | 0.1272 | 0.0031 | 1.457 | 1.135 | 1.869 | 0.0031 | 0.0185 |

| hsa_miR_27b_3p | 226 | 19.1171 | 1.4456 | 0.351 | 0.1738 | 0.0434 | 1.421 | 1.01 | 1.997 | 0.0434 | 0.0485 |

| hsa_miR_29c_3p | 172 | 19.4854 | 1.28407 | 0.5425 | 0.2457 | 0.0272 | 1.72 | 1.063 | 2.784 | 0.0272 | 0.0485 |

| hsa_miR_30a_5p | 254 | 18.461 | 1.51398 | 0.3463 | 0.1443 | 0.0164 | 1.414 | 1.066 | 1.876 | 0.0164 | 0.0485 |

| hsa_miR_30e_3p | 143 | 19.6694 | 1.9183 | -0.4287 | 0.2019 | 0.0337 | 0.651 | 0.439 | 0.967 | 0.0337 | 0.0485 |

| hsa_miR_30e_5p | 217 | 18.8058 | 1.45978 | 0.3254 | 0.1636 | 0.0467 | 1.385 | 1.005 | 1.908 | 0.0467 | 0.0485 |

| hsa_miR_3613_3p | 243 | 18.4669 | 1.6719 | 0.4435 | 0.1415 | 0.0017 | 1.558 | 1.181 | 2.056 | 0.0017 | 0.0185 |

| hsa_miR_382_3p | 96 | 20.389 | 1.12669 | 2.3048 | 1.168 | 0.0485 | 10.022 | 1.016 | 98.898 | 0.0485 | 0.0485 |

| hsa_miR_495_3p | 115 | 19.7469 | 1.49644 | 0.7446 | 0.3642 | 0.0409 | 2.106 | 1.031 | 4.299 | 0.0409 | 0.0485 |

| hsa_miR_574_3p | 108 | 20.0059 | 1.99826 | 1.103 | 0.5517 | 0.0456 | 3.013 | 1.022 | 8.884 | 0.0456 | 0.0485 |

| hsa_miR_584_5p | 181 | 19.6137 | 2.00572 | 0.4672 | 0.2098 | 0.026 | 1.595 | 1.058 | 2.407 | 0.026 | 0.0485 |

| hsa_miR_7_5p | 116 | 20.0465 | 1.01701 | 0.793 | 0.3373 | 0.0187 | 2.21 | 1.141 | 4.281 | 0.0187 | 0.048 |

Bolded are those significantly associated with echocardiographic phenotypes

For Step 1 of our analyses, we used ordinary least-squares linear regression to quantify associations between ex-RNA levels and one or more echocardiographic phenotypes in all participants. To account for multiple testing, we employed Bonferroni correction to establish a more restrictive threshold for defining statistical significance. We established a 5% false discovery rate (via the Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate approach) to screen associations between ex-RNAs and one or more echocardiographic phenotypes. The α for achieving significance was set at 0.05/340=0.000147 a priori. Note that, Cq represents a log measure of concentration, with exponentiation factor 2. In Step 2 of the analysis, we examined the associations of miRNAs identified from Step 1, with prevalent HF using a logistic regression model. Here, we used continuous Cq values to compare with prevalent HF (Table 3).

Differentially expressed miRNAs were analyzed using miRDB, an online database that captures miRNA and gene target interactions [23,24]. We acknowledge our use of the gene set enrichment analysis software, and molecular signature database (MSigDB) for gene ontology (GO) analysis [25]. The network and functional analyses were generated through the use Qiagen’s Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) [26]. All statistics were performed with SAS software version 9.3 (SAS Institute) with a 2-tailed P<0.05 as significant.

3. Results

3.1 Patient characteristics

The baseline demographic, clinical, and echocardiographic characteristics of the 296 study participants are outlined in Table 1. Study participants were middle-aged to older adults (mean age of 63±11 and 68±13 for the no HF [control group] vs. the HF group, respectively). There was a male predominance; women represented 34% and 23% of control and HF groups, respectively. The patients with HF had a significant higher history of myocardial infarction, coronary heart disease, hypertension, and atrial fibrillation (Table 1). The HF group was more likely to have experienced STEMI as compared with NSTEMI. Furthermore, QRS intervals tended to be longer in the group with HF. Patients with HF had lower LEVF and displayed a concordant trend of higher LV mass, LVED volume, LA volume, and LAVI. The mean LV mass in a patient with HF was 230±8.9 gm as compared to180±58.1 g those without prevalent HF (Table 1).

3.2 Association of ex-RNAs with echocardiographic phenotypes

A total of 374 ex-RNAs (331 miRNAs and 43 snoRNAs) were quantified in the plasma of TRACE-CORE participants included in our investigation. There were 44 ex-RNAs that associated with one or more echocardiographic parameters, independent of other clinical variables (Table 2). Three miRNAs that were associated with three or more echocardiographic traits, miR-190a-3p, miR-885-5p, and miR-596 (Supplementary Table 2).

3.3 Associations of ex-RNAs with prevalent HF

ex-RNAs associated with echocardiographic phenotypes (n=44 miRNAs) were investigated for their relationships with prevalent HF using logistic regression models. Three were significantly associated with prevalent HF, miR-29c-3p, miR-584-5p, and miR-1247-5p, all of which were inversely correlated. In general, lower ex-RNAs levels correlated with higher odds of having prevalent HF (Table 2). However, this is not consistent across all identified ex-RNAs. We found 21 ex-RNAs that associated with prevalent HF through unadjusted logistic regression modeling (Table 3).

3.4 Gene Targets of ex-RNAs associated with prevalent HF

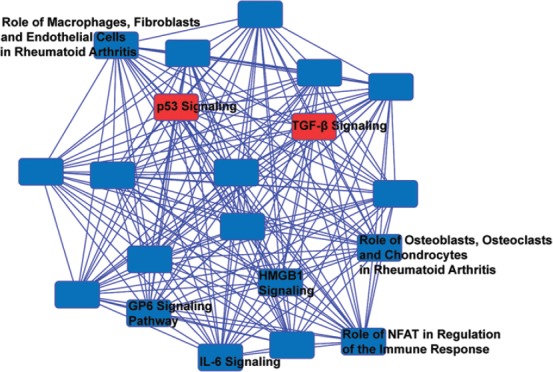

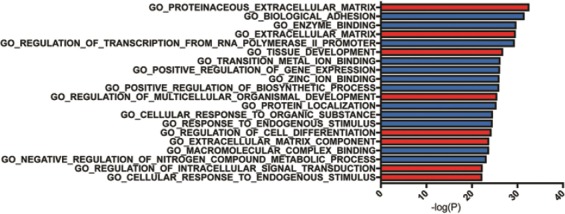

We investigated predicted targets of the three miRNAs associated with echocardiographic phenotypes and prevalent HF through miRDB. From this, 839 genes were predicted as targets for at least one miRNA. As miRNA are known to act in concert, we used the combined targets of miR-29c-3p, miR-584-5p, and miR-1247-5p to perform further analysis [6]. IPA was utilized to identify the molecular network and cellular toxicity pathways regulated by predicted targets. Overlapping canonical pathways were mapped to allow for visualization of the shared biological pathways through the common genes (Figure 2). The nodes identified included p53 signaling, transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) signaling, role of macrophages, fibroblasts and endothelial cells in rheumatoid arthritis, IL6 signaling, role of osteoblasts, osteoclasts and chondrocytes in rheumatoid arthritis, role of NFAT in regulation of the immune response, and mouse embryonic stem cell pluripotency (Figure 3, Supplementary Table 3). Highlighted in Figure 3 are pathways that were implicated in inflammation, fibrosis, and cell death; the complete list in the show in Supplementary Table 3. IPA identified predicted targets that are known to be involved in cellular toxicity based on previous reports. Table 4 lists the predicted targets as well as the cellular toxicity pathway, for example, cell death, cardiac fibrosis, p53, and TGFβ signaling. Notably, DICER1, TGFB2, HDAC1, THBS4, THBS2, and PPARC1A were among the targets identified. Gene ontology (GO) terms enrichment analysis using the MSigDB showed that miRNAs associated with echocardiographic phenotype and prevalent HF have strong associations with genes involved in the extracellular matrix, biological adhesion, and tissue development and cellular differentiation (Figure 2). We searched the literature for work exploring functions of miR-29c-3p, miR-584-5p, and miR-1247-5p (Supplementary Table 4). Dysregulation of miR-29c-3p has been implicated in cardiac development and cardiac fibrosis. miR-584-5p and miR-1247-5p have been implicated in the regulation of cellular proliferation and apoptosis in several malignancies (Supplementary Table 4).

Figure 2. A network analysis of predicted targets of miR-29-3p, miR-584-5p, and miR-1247-5p as performed by ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA). Nodes represent signaling pathways, and lines are protein targets that are common between nodes. Nodes labeled with pathways are previously associated with inflammation, cardiac necrosis, and fibrosis. p53 and TGF-β signaling pathways are highlighted in red as they are pathways consistent with GO term analysis. Full list of top 20 predicted pathway by IPA is available in Supplementary Table 3.

Figure 3. Gene ontology (GO) term analysis of predicted targets of miR-29-3p, miR-584-5p, and miR-1247-5p as performed by gene set enrichment analysis molecular signature database. Labeled in red is GO terms associated with p53 and transforming growth factor-β pathways and in blue are otherwise.

Table 4. Cellular toxicity pathways implicated by predicted targets of miR 29c-3p, miR 584-5p, and miR 1247-5p.

| Ingenuity toxicity pathway | -log (P-value) | Ratio | Gene |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiac necrosis/cell death | 3.75 | 0.068 | FNG, THBS4, LEP, LIF, PPIF, UBE4B, TNFAIP3, MDM2, KRAS, DICER1, THBD, THBS2, PRKAA1, WISP1, NAMPT, GSK3B, CDK2, MCL1, CALCA, PPARGC1A |

| p53 signaling | 3.61 | 0.0982 | AKT2, TP53INP1, CCND2, TP63, GAB1, PIK3CG, PIK3R1, HDAC1, MDM2, GSK3B, CDK2 |

| Renal necrosis/cell death | 3.23 | 0.0527 | PTHLH, EMP2, NF2, TNFAIP3, KRAS, PKN2, NFAT5, PRKAA1, NAMPT, PPM1A, AMER1, GNA13, GSK3B, CALB1, ZNF512B, MCL1, TRAF1, ITGB1, IFNG, TP53INP1, FOS, PEX5, GLIS2, CDC42, TMX1, CALCR, CDK2, CALCA, BIRC2 |

| TGF-b signaling | 2.91 | 0.0938 | RAP2A, FOS, RUNX2, CDC42, BMPR1A, HDAC1, TGFB2, KRAS, TAB1 |

| TR/RXR activation | 2.85 | 0.0918 | AKT2, GAB1, COL6A3, PIK3CG, PIK3R1, MDM2, G6PC, PPARGC1A, NCOA4 |

| Anti-apoptosis | 2.79 | 0.156 | HDAC1, TMX1, TNFAIP3, MCL1, BIRC2 |

| Hepatic fibrosis | 2.64 | 0.0857 | IFNG, LEP, COL6A3, COL4A3, THBS2, TGFB2, PDGFB, AHR, NID1 |

| Cell cycle: G1/S checkpoint regulation | 2.57 | 0.101 | CCND2, HDAC1, CDK6, TGFB2, MDM2, GSK3B, CDK2 |

| Cardiac fibrosis | 2.2 | 0.0605 | PTX3, ITGB1, IFNG, TRDN, TNFAIP3, CACNA1C, DICER1, NF1, BMPR1A, THBS2, GSK3B, DAG1, AHR |

| VDR/RXR activation | 1.71 | 0.0769 | IFNG, RUNX2, MXD1, TGFB2, CALB1, THBD |

| Liver necrosis/cell death | 1.63 | 0.0484 | IFNG, LIF, PIK3R1, DICER1, PDGFB, NPC1, FOS, NF1, PIK3CG, G6PC, GSK3B, AHR, PPARGC1A, BIRC2, MCL1 |

| Increases renal nephritis | 1.63 | 0.0833 | IFNG, LEP, LIF, TRAF3IP2, COL4A3 |

| Liver proliferation | 1.49 | 0.05 | ITGB1, IFNG, FOS, LEP, NFATC3, PIK3R1, HDAC1, PRKAA1, DICER1, GSK3B, CDK2, AHR |

| Primary glomerulonephritis biomarker panel (human) | 1.46 | 0.182 | SAMD4A, MCL1 |

| NF-kB signaling | 1.39 | 0.0469 | RAP2A, IL36G, AKT2, TRAF3, GAB1, BMPR1A, PIK3CG, PIK3R1, HDAC1, TNFAIP3, KRAS, GSK3B, TAB1 |

| Mechanism of gene regulation by peroxisome proliferators via PPARa | 1.34 | 0.0632 | FOS, PIK3R1, KRAS, PDGFB, TAB1, PPARGC1A |

| Increases cardiac proliferation | 1.33 | 0.08 | LEP, BMPR1A, WISP1, DICER1 |

| Increases renal proliferation | 1.3 | 0.0541 | ITGB1, PTHLH, YBX3, WISP1, RNF144B, PTP4A1, PDGFB, CDK2 |

| Decreases depolarization of mitochondria and mitochondrial membrane | 1.25 | 0.0938 | CSTB, MCL1, PPARGC1A |

TGF-b: Transforming growth factor-b

4. Discussion

In our investigation of ex-RNA profiles of 296 hospitalized ACS survivors in the TRACE-CORE Cohort, we identified 44 plasma ex-RNAs associated with one or more echocardiographic traits. Furthermore, three of these ex-RNAs, miR-29c-3p, miR-584-5p, and miR-1247-5p were associated with prevalent HF. While the association of miRNA and HF has been explored previously, our study uniquely examined the association between ex-RNA and HF in the acute clinical setting. We identified miR-29c-3p, miR-584-5p, and miR-1247-5p as regulators in cardiac remodeling and HF in patients hospitalized for ACS. Although miR-29 is a known to be downregulated in acute myocardial infarction and is a modulator of cardiac fibrosis [27], this is the 1st time miR-584-5p and miR-1247-5p have been implicated as having a role in HF.

4.1 Echocardiographic phenotypes and cardiac remodeling in HF

Lower LVEF and concurrent higher in LV mass, LVED volume, LA volume, and LAVI reflect adverse cardiac remodeling [13,28,29]. Echocardiographic measures of cardiac remodeling have been shown to correlate with cellular hypertrophy as well as extracellular collagen deposition, metabolic dysregulation, and myocyte cell death [30]. Furthermore, changes in these characteristics prognosticate HF disease progression with unrivaled accuracy. Although HF involves several important pathological processes, we focused on cardiac remodeling as it is key in the evolution of HF. Here, we employed a mechanism-based approach to analyze the plasma miRome to tease out the complex components that contribute to cardiac remodeling in HF.

4.2 Association of ex-RNAs, cardiac remodeling, and HF

The association of ex-RNAs with structural remodeling has been explored recently [12]. However, few prior studies have examined quantitative echocardiographic phenotypes in humans in relation to plasma miRNA expression in the acute clinical setting. Consistent with previous data, our results revealed that miR-29c-3p is associated with cardiac remodeling [27]. We identified 44 ex-RNAs with statistically significant associations with the pre-specified echocardiographic HF endophenotypes, three of which were also associated with prevalent HF. Functional analysis of downstream targets supports existing evidence that HF is coordinated through several signaling pathways, most notably p53 and TFG-β signaling.

Cardiomyocyte cell death leads to cardiac dysfunction. Consistent with previous reports, we find that p53 signaling pathway is associated with prevalent HF [31]. p53 is a major inducer of apoptosis [32,33] which is upregulated in ventricular cardiomyocytes of patients with HF [31,34]. Promotion of p53 degradation prevents myocardial apoptosis [35]. We speculate that miR-29c-3p, miR-584-5p, and miR-1247-5p targets such as CDK2 and HDAC1 to regulate p53 signaling and that decrease of these regulators results in upregulation on p53, which leads to an increase in apoptosis [36-38].

One of the targets implicated in cardiac apoptosis is DICER1, a gene encoding a RNase III endonuclease essential for miRNA processing [39]. Chen et al. found that DICER is deceased in a patient with end-stage dilated cardiomyopathy HF requiring LV assist device (LVAD) compared to patients without HF [40]. Remarkably, DICER expression is increased post-LVAD transplantation, correlating with improved cardiac function. Furthermore, they found that cardiac-specific Dicer knockout in a mouse model leads to rapid progressive dilated cardiomyopathy, HF, and postnatal lethality [40]. Dicer mutant mice show aberrant expression of cardiac contractile proteins and profound sarcomere disarray. Existing literature supports our identification of DICER1, a predicted target of miRNA identified, as critical for cardiac structure and function.

Our analysis suggests that TGF-β plays an integral part in adult patients with HF. Cardiac cell death subsequently leads to tissue fibrosis, which is in part coordinated through the TGF-β signalizing pathway [41,42]. TGF-β2 is a predicted target of identified miRNAs along with other genes (Table 4). TGF-β has been shown to downregulate the miR-29 family, which, in turn, regulate expression of collagen Type I, alpha 1 and 2 and collagen Type III, alpha 1, all of which are involved in extracellular matrix production in the heart [27]. In addition, TGF-β1 has been shown to induce endothelial cells to undergo an endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition to contribute to cardiac fibrosis [43]. Serum TGF-β levels increase significantly in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy [44]. Furthermore, myocardial TGF-β synthesis is consistently upregulated in animal models of HF [45,46].

GO categories analysis supported the hypothesis that miR-29c-3p, miR-584-5p, and miR-1247-5p have regulatory roles in cardiac remodeling through TGF-β. The top five GO categories are a proteinaceous extracellular matrix (GO:0005578), biological adhesion (GO:0022610), enzyme binding (GO:0031012), regulation of transcription from RNA polymerase promoter (GO:0006357), and tissue development (GO:0009888). Notably, there is a recurring theme of the GO term enrichment in extracellular matrix remodeling and cell differentiation, both of which has been shown to be regulated by TFG-β [47,48]. Together, our data support that miR-29c-3p, miR-584-5p, and miR-1247-5p affect cardiac remodeling structurally by influencing cell death and fibrosis, in part through the p53 and TFG-β signaling pathways.

Previously, we identified that miR-106b-5p, miR-17-5p, and miR-20a-5p 3 were associated with a reduction in long-term incident HF [12]. In our current analysis, we found that miR-17-5p was independently associated with prevalent HF. Wong et al. have examined the plasma miRome in patients with HF, HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFPEF), and HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFREF) and identified miRNAs associated with the clinical phenotypes [49]. We do not find an overlap between our ex-RNAs and those previously identified to be associated with HF. This could be due to the fact that the Singapore HF Outcomes and Phenotype (SHOP) cohort was a different racial and geographical cohort. Importantly, patients from the SHOP cohort were recruited from the ambulatory setting, whereas our TRACE-CORE cohort focused on patients in the hospitalized setting. Mick et al. examined ex-RNA associated with stroke or coronary heart disease [50]. There is no overlap in the ex-RNA identified to be associated with stroke, perhaps highlighting key differences between ACS and stroke.

4.3 Strength and limitations

Our study has several strengths. We examined ex-RNA associations with echocardiographic traits and HF in a well-characterized cohort study. TRACE-CORE is a cohort hospitalized ACS survivors, which uniquely provided the expression profiles of plasma ex-RNA in the acute clinical setting. In this study, our observations may reflect biomarker changes secondary to ACS rather than HF. However, we did not find any significant differences in ex-RNA due to AMI in our previous work [50]. As we used the same methodology to study ex-RNA in this study, the differential expression of ex-RNA observed is more likely secondary to HF status rather than ACS.

Our study has several shortcomings, among which is its relatively small sample size that is not racially or geographically diverse. We lack the power to examine whether these three miRNAs were associated with HF subtypes, HFPEF, or HFREF. Although we find that these miRs are associated with echophenotypes and HF, we have not located the sources or understand the mechanism by which they are transported in the blood. Further experiments at the bench are needed to explore these key questions to improve understanding of the molecular processes by which these miRs regulate HF.

5. Conclusions

In our analysis of echocardiographic, clinical, and ex-RNAs data from ACS survivors enrolled in the TRACE-CORE cohort, we observed that three ex-RNAs, miR-29c-3p, miR-584-5p, and miR-1247-5p were associated with echocardiographic phenotypes and prevalent HF. These ex-RNAs were predicted to mediate cardiac remodeling in part through the p53 and TFG-β signaling pathways. Further studies with a diverse cohort as well as basic experimentation are needed to validate our results. Our work establishes a mechanism-based framework for the identification of novel ex-RNAs biomarkers and downstream targets to attenuate cardiac remodeling that lead to HF.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by 5T32HL120823 (KVT), 1U01HL105268, R01HL126911 (DDM), R01HL137734 (DDM), R01HL137794 (DDM), R01HL13660 (DDM), and R01HL141434 (DDM) from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, Grant 1522052 from the National Science Foundation (DDM), and 16SFRN31740000 from the American Heart Association (JEF); RFA-HL-12-008 (JEF), RO1 HL087201A (JEF, KT), RFA-HL-12-008 (JEF), and U01HL105268 (CIK from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosures

DDM has received research support from Apple Computer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringher-Ingelheim, Pfizer, Samsung, Philips Healthcare, Biotronik, has received consultancy fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Flexcon, Boston Biomedical Associates, Samsung, and has inventor equity in Mobile Sense Technologies, Inc. (CT).

References

- [1].Ziaeian B, Fonarow GC. Epidemiology and Aetiology of Heart Failure. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2016;13:368–78. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2016.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics--2015 Update:A Report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;131:e29–322. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Voelkel NF, Quaife RA, Leinwand LA, Barst RJ, McGoon MD, Meldrum DR, et al. Right Ventricular Function and Failure:Report of a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Working Group on Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Right Heart Failure. Circulation. 2006;114:1883–91. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.632208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Mann DL, Bristow MR. Mechanisms and Models in Heart Failure:The Biomechanical Model and Beyond. Circulation. 2005;111:2837–49. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.500546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Tanai E, Frantz S. Pathophysiology of Heart Failure. Compr Physiol. 2015;6:187–214. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c140055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Bartel DP. Metazoan MicroRNAs. Cell. 2018;173:20–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].McManus DD, Ambros V. Circulating MicroRNAs in Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation. 2011;124:1908–10. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.062117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Freedman JE, Gerstein M, Mick E, Rozowsky J, Levy D, Kitchen R, et al. Corrigendum:Diverse Human Extracellular RNAs are widely Detected in Human Plasma. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11902. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Tijsen AJ, Creemers EE, Moerland PD, de Windt LJ, van der Wal AC, Kok WE, et al. MiR423-5p as a Circulating Biomarker for Heart Failure. Circ Res. 2010;106:1035–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.218297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Scrutinio D, Conserva F, Passantino A, Iacoviello M, Lagioia R, Gesualdo L, et al. Circulating MicroRNA-150-5p as a Novel Biomarker for Advanced Heart Failure:A Genome-wide Prospective Study. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2017;36:616–24. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2017.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Melman YF, Shah R, Danielson K, Xiao J, Simonson B, Barth A, et al. Circulating MicroRNA-30d is associated with Response to Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy in Heart Failure and Regulates Cardiomyocyte Apoptosis:A Translational Pilot Study. Circulation. 2015;131:2202–16. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.013220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Shah RV, Rong J, Larson MG, Yeri A, Ziegler O, Tanriverdi K, et al. Associations of Circulating Extracellular RNAs with Myocardial Remodeling and Heart Failure. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3:871–6. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.2371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Prastaro M, D'Amore C, Paolillo S, Losi M, Marciano C, Perrino C, et al. Prognostic Role of Transthoracic Echocardiography in Patients affected by Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction. Heart Fail Rev. 2015;20:305–16. doi: 10.1007/s10741-014-9461-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Maurer MS, Koh WJ, Bartz TM, Vullaganti S, Barasch E, Gardin JM, et al. Relation of the Myocardial Contraction Fraction, as Calculated from M-mode Echocardiography, with Incident Heart Failure, Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality (Results from the Cardiovascular Health Study) Am J Cardiol. 2017;119:923–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.11.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Zoccola PM, Manigault AW, Figueroa WS, Hollenbeck C, Mendlein A, Woody A, et al. Trait Rumination Predicts Elevated Evening Cortisol in Sexual and Gender Minority Young Adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14:E1365. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14111365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Almahmoud MF, O'Neal WT, Qureshi W, Soliman EZ. Electrocardiographic Versus Echocardiographic Left Ventricular Hypertrophy in Prediction of Congestive Heart Failure in the Elderly. Clin Cardiol. 2015;38:365–70. doi: 10.1002/clc.22402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Carluccio E, Dini FL, Biagioli P, Lauciello R, Simioniuc A, Zuchi C, et al. The 'Echo Heart Failure Score':An Echocardiographic Risk Prediction Score of Mortality in Systolic Heart Failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2013;15:868–76. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hft038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Waring ME, McManus RH, Saczynski JS, Anatchkova MD, McManus DD, Devereaux RS, et al. Transitions, Risks, and Actions in Coronary Events-center for Outcomes Research and Education (TRACE-CORE):Design and Rationale. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5:e44–50. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.112.965418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].McManus DD, Saczynski JS, Lessard D, Waring ME, Allison J, Parish DC, et al. Reliability of Predicting Early Hospital Readmission after Discharge for an Acute Coronary Syndrome using Claims-based Data. Am J Cardiol. 2016;117:501–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].McManus DD, Lin H, Tanriverdi K, Quercio M, Yin X, Larson MG, et al. Relations between Circulating MicroRNAs and Atrial Fibrillation:Data from the Framingham Offspring Study. Heart Rhythm. 2014;11:663–9. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, Afilalo J, Armstrong A, Ernande L, et al. Recommendations for Cardiac Chamber Quantification by Echocardiography in Adults:An Update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015;28:1–3.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Devereux RB, Alonso DR, Lutas EM, Gottlieb GJ, Campo E, Sachs I, et al. Echocardiographic Assessment of Left Ventricular Hypertrophy:Comparison to Necropsy Findings. Am J Cardiol. 1986;57:450–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(86)90771-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Wong N, Wang X. MiRDB:An Online Resource for MicroRNA Target Prediction and Functional Annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D146–52. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Wang X. Improving MicroRNA Target Prediction by Modeling with Unambiguously identified MicroRNA-target Pairs from CLIP-ligation Studies. Bioinformatics. 2016;32:1316–22. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, et al. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis:A Knowledge-based Approach for Interpreting Genome-wide Expression Profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15545–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Krämer A, Green J, Pollard J, Jr, Tugendreich S. Causal Analysis Approaches in Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:523–30. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].van Rooij E, Sutherland LB, Thatcher JE, DiMaio JM, Naseem RH, Marshall WS, et al. Dysregulation of MicroRNAs after Myocardial Infarction Reveals a Role of miR-29 in Cardiac Fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:13027–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805038105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Gaasch WH, Zile MR. Left Ventricular Structural Remodeling in Health and Disease:With Special Emphasis on Volume, Mass, and Geometry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:1733–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Verma A, Meris A, Skali H, Ghali JK, Arnold JM, Bourgoun M, et al. Prognostic Implications of Left Ventricular Mass and Geometry following Myocardial Infarction:The VALIANT (VALsartan in Acute Myocardial iNfarcTion) Echocardiographic Study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2008;1:582–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2008.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Cohn JN, Ferrari R, Sharpe N. Cardiac Remodeling-concepts and Clinical Implications:A Consensus Paper from an International Forum on Cardiac Remodeling. Behalf of an International Forum on Cardiac Remodeling. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:569–82. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00630-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Birks EJ, Latif N, Enesa K, Folkvang T, Luong le A, Sarathchandra P, et al. Elevated p53 Expression is associated with Dysregulation of the Ubiquitin-proteasome System in Dilated Cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;79:472–80. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Crow MT, Mani K, Nam YJ, Kitsis RN. The Mitochondrial Death Pathway and Cardiac Myocyte Apoptosis. Circ Res. 2004;95:957–70. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000148632.35500.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Fujita T, Ishikawa Y Apoptosis in Heart Failure. The Role of the Beta-adrenergic Receptor-mediated Signaling Pathway and p53-mediated Signaling Pathway in the Apoptosis of Cardiomyocytes. Circ J. 2011;75:1811–8. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-11-0025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Song H, Conte JV, Jr, Foster AH, McLaughlin JS, Wei C. Increased p53 Protein Expression in Human Failing Myocardium. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1999;18:744–9. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(98)00039-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Naito AT, Okada S, Minamino T, Iwanaga K, Liu ML, Sumida T, et al. Promotion of CHIP-mediated p53 Degradation Protects the Heart from Ischemic Injury. Circ Res. 2010;106:1692–702. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.214346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Zalzali H, Nasr B, Harajly M, Basma H, Ghamloush F, Ghayad S, et al. CDK2 Transcriptional Repression is an Essential Effector in p53-dependent Cellular Senescence-implications for Therapeutic Intervention. Mol Cancer Res. 2015;13:29–40. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-14-0163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Ito A, Kawaguchi Y, Lai CH, Kovacs JJ, Higashimoto Y, Appella E, et al. MDM2-HDAC1-mediated Deacetylation of p53 is required for its Degradation. EMBO J. 2002;21:6236–45. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Lagger G, Doetzlhofer A, Schuettengruber B, Haidweger E, Simboeck E, Tischler J, et al. The Tumor Suppressor p53 and Histone Deacetylase 1 are Antagonistic Regulators of the Cyclin-dependent Kinase Inhibitor p21/WAF1/CIP1 Gene. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:2669–79. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.8.2669-2679.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Hutvágner G, McLachlan J, Pasquinelli AE, Bálint E, Tuschl T, Zamore PD, et al. ACellular Function for the RNA-interference Enzyme Dicer in the Maturation of the Let-7 Small Temporal RNA. Science. 2001;293:834–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1062961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Chen JF, Murchison EP, Tang R, Callis TE, Tatsuguchi M, Deng Z, et al. Targeted Deletion of Dicer in the Heart Leads to Dilated Cardiomyopathy and Heart Failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:2111–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710228105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Border WA, Noble NA. Transforming Growth Factor Beta in Tissue Fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1286–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199411103311907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Khalil H, Kanisicak O, Prasad V, Correll RN, Fu X, Schips T, et al. Fibroblast-Specific TGF-β-smad2/3 Signaling Underlies Cardiac Fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:3770–83. doi: 10.1172/JCI94753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Zeisberg EM, Tarnavski O, Zeisberg M, Dorfman AL, McMullen JR, Gustafsson E, et al. Endothelial-to-mesenchymal Transition Contributes to Cardiac Fibrosis. Nat Med. 2007;13:952–61. doi: 10.1038/nm1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Ayça B, Sahin I, Kucuk SH, Akin F, Kafadar D, Avşar M, et al. Increased Transforming Growth Factor-βLevels associated with Cardiac Adverse Events in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Clin Cardiol. 2015;38:371–7. doi: 10.1002/clc.22404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Dobaczewski M, Chen W, Frangogiannis NG. Transforming Growth Factor (TGF)-βSignaling in Cardiac Remodeling. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;51:600–6. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.10.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Li JM, Brooks G. Differential Protein Expression and Subcellular Distribution of TGFbeta1, beta2 and beta3 in Cardiomyocytes during Pressure Overload-induced Hypertrophy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1997;29:2213–24. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1997.0457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Watabe T, Miyazono K. Roles of TGF-beta Family Signaling in Stem Cell Renewal and Differentiation. Cell Res. 2009;19:103–15. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Bhandary B, Meng Q, James J, Osinska H, Gulick J, Valiente-Alandi I, et al. Cardiac Fibrosis in Proteotoxic Cardiac Disease is Dependent upon Myofibroblast TGF-βSignaling. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e010013. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.010013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Wong LL, Armugam A, Sepramaniam S, Karolina DS, Lim KY, Lim JY, et al. Circulating MicroRNAs in Heart Failure with Reduced and Preserved Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2015;17:393–404. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Mick E, Shah R, Tanriverdi K, Murthy V, Gerstein M, Rozowsky J, et al. Stroke and Circulating Extracellular RNAs. Stroke. 2017;48:828–34. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.015140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]