Abstract

Telomere DNA, at the ends of each chromosome, is conserved in nature and required for chromosome replication and stability. Reduction in telomere length has been observed in several malignancies as well as in leukocytes from healthy persons with advancing age. There is a paucity of data regarding telomere length and the effects of in vivo aging in different tissues. These data could be helpful in interpreting telomere length and understanding the role of telomere integrity and telomerase activity in malignant cells. We report telomeric DNA integrity studies of blood and skin collected from eight Caucasians of both sexes representing each decade of life from the fetus to 72 years of age without exposure to chemotherapy or radiation. In addition, telomeric data from 15 other tissues from the fetus and 8 other tissues from the 72-year-old male were examined. No significant differences were found in the shortest telomere size, the average telomere size, or telomere size variation between blood and skin from subjects at different ages. The average telomere size was 11.7 ± 2.2 kb for blood and 12.8 ± 3.7 for skin in all subjects studied. The shortest telomere length was 5.4 ± 1.9 kb for blood and 4.3 ± 0.9 kb for skin. Significant differences (P < 0.001) were found in the overall length of the DNA hybridization signal representing the shortest telomere size and the length of the DNA peak migration hybridization signal representing variation in telomere size between the 20-week fetus and the 72-year-old male. The 72-year-old male showed the shortest telomeres and the most variation (heterogeneity) in telomere size for all tissues studied, but the greatest differences were observed in blood compared with other tissues (e.g., average telomere length was 12.2 kb in the fetus and 7.2 kb in the 72-year-old male). The size of the telomere was negatively correlated with age for all tissues studied.

INTRODUCTION

The telomere is the region of DNA at the end of each chromosome. Telomere DNA consists of terminal repeat arrays of base pairs characterized by clusters of G residues in the 3’ strand (TTAGGG)n, which have been isolated from telomeres of humans [1, 2], They are highly conserved in nature and have been found in the termini of linear chromosomes from plants, animals, protists, and fungi [3]. The telomere is required for chromosome replication and stability. The terminal repeat arrays prevent the binding of the ends of DNA from other chromosomes, thus preventing end-to-end fusions or telomeric associations. Interestingly, telomeric associations in conjunction with telomere reduction and telomerase activity have been reported in malignancies such as giant cell tumor of bone, a primary skeletal neoplasm with telomeric reduction [4–6].

Reduction in telomere length has been observed in several malignancies including colon, glioblastoma, leukemia, Wilms tumor, breast, and lung, as well as the in vitro senescence of human fibroblasts [7–13]. We and others have reported loss of telomere size in leukocytes from healthy persons with advancing age (e.g., average 40 base pairs per year), with the greatest loss identified in the younger persons (less than 20 years old) [14–16]. Thus, loss of telomeric DNA during cell proliferation may play a role in aging and cancer [11, 15]. The average telomere length in healthy human cells varies from 5 (60–70 years old) to 20(<10 years) kilobases [15]. The telomere is shorter in somatic tissue than in sperm cells [14]. There is a paucity of data regarding the telomere length in different tissues synchronously harvested from one subject and the effects that in vivo aging has on the telomere. These data could be helpful in interpreting telomere length and understanding the role of telomere integrity and telomerase activity in malignant cells. Therefore, we report for the first time characterization of telomere integrity and variation in size in multiple human tissues collected from subjects at different ages.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Peripheral blood (5–10 cc) and skin samples (1 cm3) were collected from eight different Caucasians of both sexes (20-week female fetus, 4-year-old male, 16-year-old male, 24-year-old male, 33-year-old female, 44-year-old female, 58-year-old male, and 72-year-old male) without exposure to chemotherapy or radiation. Seventeen tissue specimens were collected at the time of autopsy after institutional review board approval from a 20-week female fetus (blood, liver, spleen, brain, kidney, skeletal muscle, heart, lung, thymus, fat, placenta, fascia, pancreas, stomach, adrenal, ovary, and skin), and 10 specimens were collected from a 72-year-old male (heart, lung, liver, pancreas, brain, fat, skin, blood, large intestine, and skeletal muscle) for comparison purposes.

Genomic DNA was successfully isolated from the tissue and blood samples from all subjects studied following standard protocols [15]. Five micrograms of genomic DNA was digested from each sample with HinfI enzyme at 37°C for 4 hours after a minigel electrophoresis was performed to check for DNA degradation. HinfI cleaves frequently in human genomic DNA but not within telomeric sequences, therefore leaving the telomeric DNA intact. A minigel electrophoresis was then performed to check for completeness of digestion. DNA was loaded onto 0.8% agarose gel, and electrophoresis was performed for 5 hours at 58 V. The gel was then blotted to Gene Screen Plus nylon membrane and hybridized with the 32P-nick-labeled (TTAGGG)50 telomeric probe synthesized by the polymerase chain reaction (Oncor, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD). Completeness of DNA transfer to the membrane after the blotting process was visually checked after staining the gel with ethidium bromide and exposing it to ultraviolet light. Hybridization was performed at 42°C for 2 days, and the filter was washed in an SSC/SDS mixture at 42°C. The filters were then exposed to high-performance autoradiographic film. The signal for each autoradiograph was standardized visually by varying the exposure of the autoradiographic film to allow for equal intensity of the DNA hybridization signal among the different films for analysis. The autoradiographs were then analyzed by using an LBK soft laser spectrophotometer as performed in previous studies [7, 15, 17] to determine the maximum DNA peak location, length of the DNA peak hybridization signal, and overall length of the DNA signal.

Each DNA lane was scanned for a distance of 17 cm by densitometry to include the total DNA hybridization signal for each of the autoradiographic films analyzed. To control for variation in interpretation of telomere size among the experiments (e.g., fetus vs. 72-year-old male), Southern blots, densitometry, and DNA extraction and digestion of the same tissue sample were repeated for several specimens. The data from these repeated measures were combined, and the averages and standard deviations are shown in Tables 1 and 2. DNA fragments migrating farther, detected by the hybridized radiolabeled telomere probe, represented shorter telomeres, and those not migrating as far represented longer telomeres. An average telomere size was calculated from the distance of the maximum DNA peak location determined by densitometry and after comparison with DNA markers of known size following the protocols reported previously [7, 15]. The shortest telomere size of the telomeric DNA migrating farthest from the source of the DNA origin was determined by the overall length of the DNA hybridization signal. The length or width of the DNA peak hybridization signal was determined by densitometry and represented the various telomere sizes reflecting telomeric length heterogeneity.

Table 1.

Comparison of telomere data between blood and skin from all ages

| Shortest telomere size determined by: | Average or mode telomere size determined by: | Variation in telomere size determined by: | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject | Overall length of DNA migration (mm) | Shortest telomere length (kb) | Maximum DNA peak migration (mm) | Average telomere length (kb) | Length of DNA peak migration (mm) | Length of DNA Peak migration (kb)a |

| Blood | ||||||

| 20 week fetus | 33.1 ± 1.9 | 6.6 ± 0.3 | 21.7 ± 2.3 | 12.2 ± 2.5 | 26.9 ± 2.9 | 8.7 |

| 4 years | 32.9 | 6.7 | 20.2 | 13.5 | 30.6 | 7.6 |

| 16 years | 35.1 ± 3.6 | 6.1 ± .09 | 19.3 ± 5.0 | 14.5 ± 5.9 | 26.6 ± 1.8 | 9.2 |

| 24 years | 31.8 | 7.0 | 20.7 | 12.0 | 20.6 | 12.8 |

| 33 years | 51.2 | 4.1 | 21.5 | 11.5 | 41.8 | 5.1 |

| 44 years | 40.6 ± 0.8 | 5.1 ± .05 | 23.5 ± 7.1 | 10.6 ± 4.8 | 30.0 ± 0.8 | 7.8 |

| 58 years | 44.1 ± 1.6 | 4.6 ± 0.1 | 20.8 ± 0.4. | 11.8 ± 0.4 | 40.0 ± 7.5 | 5.4 |

| 72 years | 67.6 ± 5.9 | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 30.2 ± 4.8 | 7.2 ± 1.0 | 59.8 ± 1.5 | 2.8 |

| Mean + SD | 42.1 ± 12.3 | 5.4 ± 1.9 | 22.2 ± 3.4 | 11.7 ± 2.2 | 34.5 ± 12.4 | 7.4 ± 3.0 |

| Skin | ||||||

| 20 week fetus | 41.2 ± 1.8 | 5.1 ± 0.6 | 19.8 ± 2.8 | 13.0 ± 2.2 | 38.2 ± 3.1 | 5.3 |

| 16 years | 45.5 ± 4.9 | 4.5 ± 0.4 | 19.4 ± 2.4 | 14.3 ± 2.9 | 38.4 ± 5.9 | 5.7 |

| 33 years | 37.6 | 5.7 | 19.7 | 13.0 | 29.4 | 8.0 |

| 44 years | 60.3 ± 4.6 | 3.0 ± 0.3 | 24.9 ± 4.7 | 9.4 ± 3.0 | 58.5 ± 3.8 | 3.3 |

| 58 years | 52.4 ± 15.8 | 4.3 ± 1.2 | 25.6 ± 1.8 | 9.0 ± 0.7 | 45.3 ± 14.1 | 4.6 |

| 72 years | 48.5 ± 7.9 | 4.0 ± 0.5 | 23.1 ± 1.0 | 9.8 ± 1.0 | 45.0 ± 7.1 | 4.2 |

| Mean ± SD | 47.6 ± 8.1 | 4.3 ± 0.9 | 22.1 ± 2.8 | 12.8 ± 3.7 | 42.5 ± 9.8 | 5.2 ± 1.6 |

No significant differences were found in the overall length of telomere DNA migration (in mm) (independent t = −1.0; P > 0.05); shortest telomere length (in kb) (independent t = 1.4; P > 0.05); maximum DNA peak (in mm) (independent t = 0.1; P > 0.05); average telomere length (in kb) (independent t = 0.2; P > 0.05 or length of DNA peak migration (in mm) (independent t = − 1.3; P > 0.05) between blood and skin from subjects of different ages.

The length of the DNA peak migration is converted into kilobases by using a curve generated from DNA markers of known size. When length is converted into kilobase size, the longer the DNA peak migration, the smaller the telomere size in kb. In addition, the greater the length or width of the DNA peak migration, the more variation in telomere size. Therefore, there were no differences in the telomere size or variation in blood or skin from individuals at all ages.

Table 2.

Comparison of telomere data among tissues from 20-week female fetus and 72-year-old male

| Shortest telomere size determined by: | Average or mode telomere size determined by: | Variation in telomere size determined by: | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject | Overall length of DNA migration (mm)a | Shortest telomere length (kb)b | Maximum DNA peak migration (mm)c | Average telomere length (kb)d | Length of DNA peak migration (mm)e | Length of DNA peak migration (kb)f |

| 20-week female fetus | ||||||

| Bloodg | 33.1 ± 1.9 | 6.6 ± 0.3 | 21.7 ± 2.3 | 12.2 ± 2.5 | 26.9 ± 2.9 | 8.7 |

| Sking | 41.2 ± 1.8 | 5.1 ± 0.6 | 19.8 ± 2.8 | 13.0 ± 2.2 | 38.2 ± 5.4 | 5.3 |

| Skeletal Muscleg | 37.1 | 5.4 | 21.5 | 10.5 | 36.5 | 5.5 |

| Heartg | 36.5 | 5.4 | 24.9 | 9.2 | 22.9 | 11.0 |

| Liverg | 38.2 ± 2.5 | 5.4 ± 0.0 | 20.8 ± 1.4 | 12.0 ± 2.1 | 30.0 ± 7.5 | 7.3 |

| Pancreasg | 38.5 ± 2.9 | 5.4 ± 0.1 | 21.6 ± 2.7 | 11.5 ± 2.8 | 30.0 ± 9.2 | 7.3 |

| Stomach | 35.3 | 5.7 | 20.5 | 11.5 | 21.8 | 11.8 |

| Spleen | 39.4 | 5.1 | 23.4 | 10.0 | 31.2 | 6.9 |

| Lungg | 37.9 ± 2.9 | 5.5 ± 0.1 | 21.3 ± 2.3 | 12.0 ± 2.1 | 30.0 ± 9.2 | 7.3 |

| Braing | 32.4 | 6.2 | 21.3 | 11.5 | 26.5 | 8.8 |

| Fatg | 44.1 | 4.4 | 21.6 | 10.5 | 31.2 | 6.9 |

| Kidney | 39.4 | 5.0 | 22.4 | 10.5 | 33.5 | 6.2 |

| Adrenal | 37.6 | 5.2 | 22.9 | 10.5 | 29.4 | 7.6 |

| Placenta | 38.2 | 5.2 | 20.1 | 12.0 | 28.8 | 7.8 |

| Ovary | 37.1 | 5.3 | 23.5 | 9.4 | 28.8 | 7.8 |

| Thymus | 38.8 | 5.1 | 22.6 | 10.0 | 35.9 | 5.6 |

| Fascia | 38.2 | 5.2 | 22.6 | 10.5 | 25.3 | 9.5 |

| Mean ± SD | 37.8 ± 2.7 | 5.4 ± 0.5 | 21.9 ± 1.3 | 11.0 ± 1.1 | 29.8 ± 4.5 | 7.7 ± 1.8 |

| 72-year-old male | ||||||

| Bloodg | 67.6 ± 5.9 | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 30.2 ± 4.8 | 7.2 ± 1.0 | 59.8 ± 1.5 | 2.8 |

| Sking | 48.5 ± 7.9 | 4.0 ± 0.5 | 23.1 ± 1.0 | 9.8 ± 1.0 | 45.0 ± 7.1 | 4.2 |

| Skeletal muscleg | 48.8 | 4.1 | 19.3 | 12.5 | 40.6 | 4.8 |

| Heartg | 55.3 | 3.6 | 20.7 | 11.5 | 50.0 | 3.6 |

| Liverg | 78.2 ± 16.6 | 5.6 ± 4.1 | 29.8 ± 12.9 | 8.8 ± 4.5 | 75.9 ± 13.3 | 2.0 |

| Pancreasg | 45.0± 17.9 | 5.2 ± 2.4 | 24.1 ± 1.5 | 9.7 ± 0.5 | 36.8 ± 23.7 | 5.6 |

| Large intestine | 46.5 | 4.3 | 19.8 | 12.5 | 41.2 | 4.7 |

| Lungg | 66.5 ± 9.2 | 4.1 ± 2.1 | 31.1 ± 13.4 | 7.9 ± 3.7 | 44.4 ± 31.2 | 4.3 |

| Braing | 52.9 | 3.8 | 22.6 | 10.0 | 44.1 | 4.3 |

| Fatg | 51.8 | 3.8 | 23.8 | 10.0 | 51.8 | 3.4 |

| Mean ± SD | 56.1 ± 11.0 | 4.1 ± 0.8 | 24.5 ± 4.4 | 10.0 ± 1.8 | 48.9 ± 11.5 | 4.0 ± 1.0 |

Significant difference was found for overall length of telomere DNA migration (in mm) among all tissues from the fetus and 72-year-old male (independent t = −6.6; P < 0.001). A longer migration distance was observed in the tissues from the 72-year-old male.

Significant difference was found for the shortest telomere length (in kb) among all the tissues from the fetus and 72-year-old male (independent t = 4.5; P < 0.001). Shorter telomeres were observed in tissues from 72-year-old male.

Significant difference was found for the maximum DNA peak migration (in mm) (independent t = −2.2; P < 0.05).

No significant difference was found for average telomere length (in kb) (independent t = 1.6; P > 0.05) among all tissues from the fetus and 72-year-old male.

Significant difference was found in length of DNA peak migration (in mm) among all tissues tissues from the fetus and 72-year-old male (independent t = −5.0; P < 0.001).

The length of the DNA peak migration is converted into kilobases by using a curve generated from DNA markers of known size. When length is converted into kilobase size, the longer the DNA peak migration, the smaller the telomere size in kb. In addition, the greater the length or width of the DNA peak migration, the more variation in telomere size. Therefore, shorter telomere sizes determined in tissues from the 72-year-old male compared with tissues from the 20-week fetus in our study represented a wider range of telomere lengths or more variation in size in the older male.

Tissues common to the fetus and the 72-year-old male.

To determine the distribution of telomere sizes in the total DNA hybridization pattern, the hybridization signal was divided into seven representative zones, or regions, and converted into telomere size (>24 kb; 24–16 kb, 16–9 kb; 9–7 kb; 7–4 kb; 4—2 kb; < 2 kb) on the basis of a curve generated by a power equation produced from DNA markers of known size by using an SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) computer program for fitting data to a curve. By the use of the equation (e.g., kilobase = 983.477 x millimeter−1435), kilobases could be determined from DNA migration distance in millimeters for each subject. Representative tissue specimens were examined from the 20-week fetus and 72-year-old male as well as blood and skin samples at different ages. The proportion or percentage of telomere sizes found in each of the hybridization zones was then determined by calculating the area under the DNA hybridization curve for each zone. For statistical analysis, independent and matched f-tests, regression, and correlation values were calculated from the telomeric data throughout this study.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

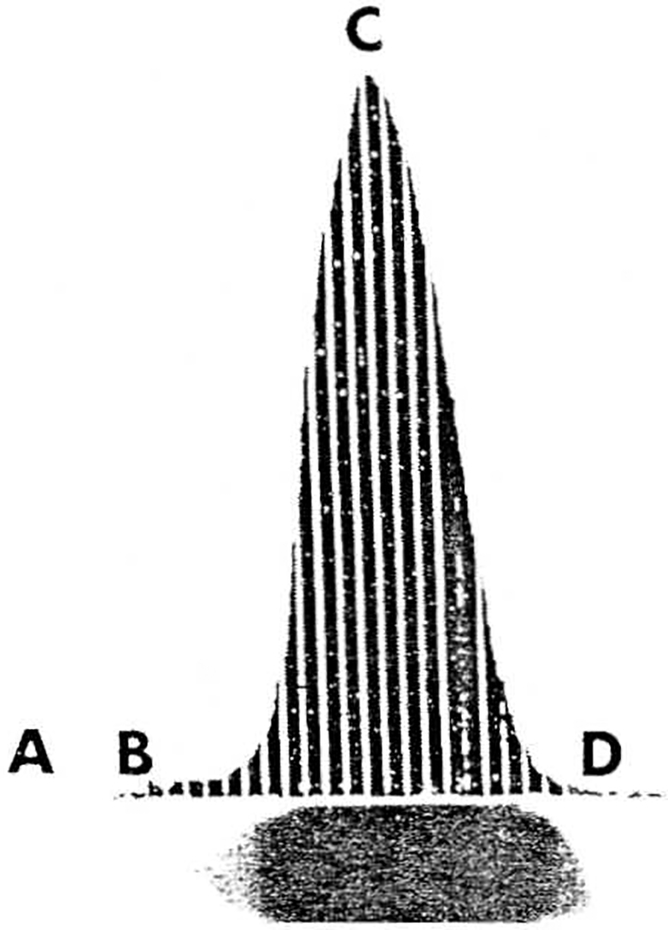

The subjects, ages, tissue specimens, overall length of DNA migration in millimeters, shortest telomere length in kilobases, maximum DNA peak migration in millimeters, average telomere length in kilobases, and length of the DNA peak migration in millimeters and converted into kilobases are given in Tables 1 and 2. Autoradiographs of the radiolabeled hybridized filters were densitometrically scanned, producing a DNA hybridization pattern for each lane. Optical density recorded by the scanner signifies this DNA migration pattern, which can be converted into kilo-base size for the telomeres. The telomere length was established with the use of DNA markers of known size and the development of a curve. A mean peak intensity was calculated for each of the DNA samples. The overall length of the DNA hybridization signal from the origin of the DNA lane to the end of the signal was converted into telomere size (in kb) and represents the shortest telomeres. The length of the DNA peak migration represents the variation or heterogeneity of telomere size. Thus, the wider (or longer) the DNA peak migration, the more variation (heterogeneity) was found in the size of the telomere. The average telomere length, shortest telomere size, and variation in telomere length were determined by the aforedescribed methodology (Fig. 1). To our knowledge, the shortest telomere size and telomere length variation were recorded for the first time in human tissues from subjects at various ages.

Figure 1.

A diagram of a typical densitometric tracing generated after scanning a telomeric DNA hybridization lane, which is represented in the horizontal axis. Letter A represents the origin of the DNA lane, B represents the beginning of the DNA hybridization peak, C represents the maximum DNA peak migration, and D represents the end of the hybridization signal. The overall length of the hybridization signal is measured from the origin of the DNA lane (A) to the end of the signal (D) and represents the shortest telomeres when converted into telomere size (in kb). The average or mode telomere size is represented by the maximum peak migration (C) and converted into kilobases. The length of DNA peak migration is measured from B to D and represents the variation in telomere size.

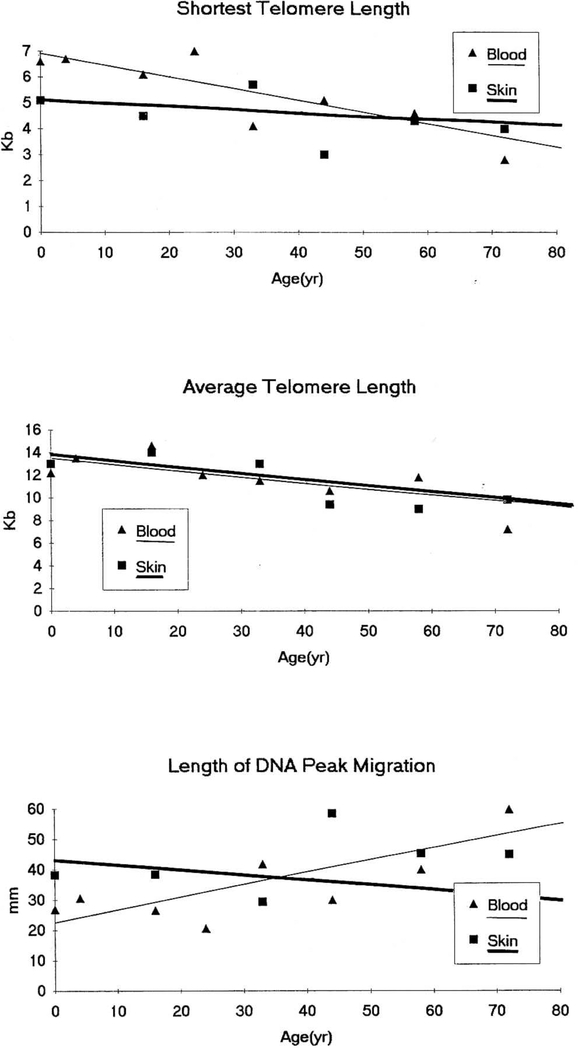

Comparison of telomeric DNA isolated from peripheral blood and skin was undertaken from eight Caucasians representing the decades of life and ranging from a 20-week female fetus to a 72-year-old male. There were no significant differences in the shortest telomere size (independent t-test = 1.0; P > 0.05), variation in telomere size (independent t-test = −1.3; P > 0.05), or average telomere length (independent t-test = 0.1; P > 0.05) when comparing blood and skin from subjects at different ages (see Table 1). However, significant negative correlations with age were found for the average telomere length from DNA (i.e., shorter average telomere size in the older subjects) isolated from both blood (r = −0.78; P < 0.05) and skin cells (r = −0.82; P < 0.05). In addition, a significant negative correlation with age was found for the shortest telomere length from DNA isolated from blood (r = −0.87; P < 0.01) (i.e., shorter telomere length in blood in older subjects) but not in skin (r = −0.48; P > 0.05). A significant positive correlation with age was found for the length of DNA peak migration from DNA isolated from blood (r = 0.77; P < 0.05) but not for skin (r = 0.43; P > 0.05) (i.e., greater telomere length heterogeneity in blood from older subjects).

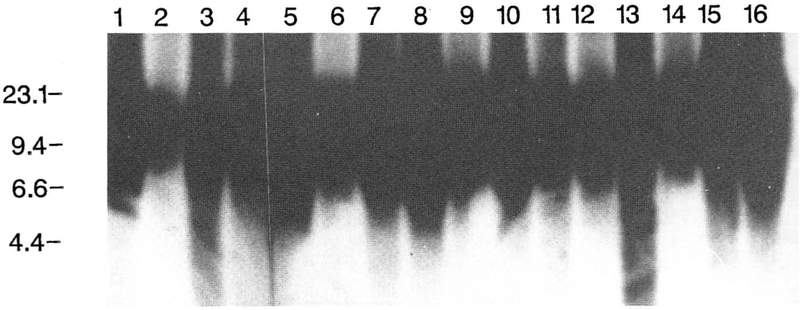

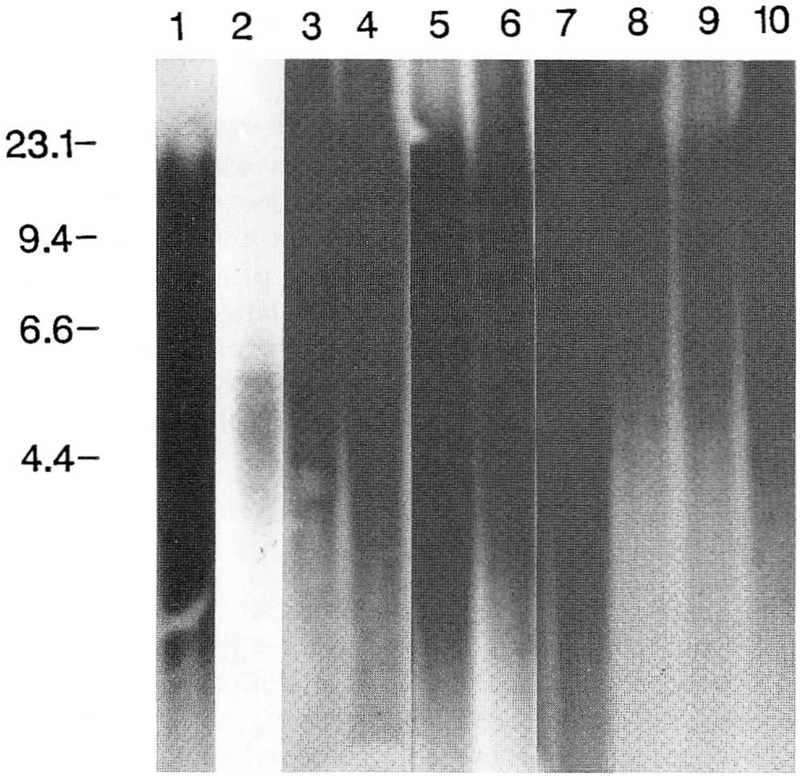

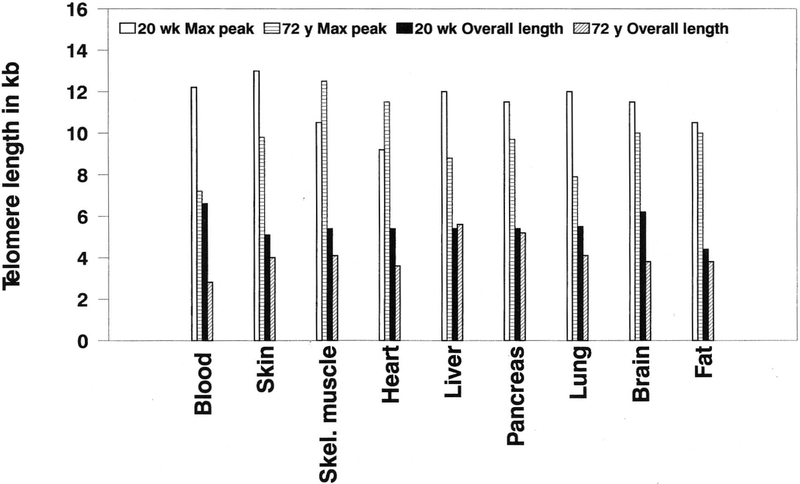

Figure 2 shows the Southern hybridization pattern of telomeric DNA for 16 tissues isolated from the 20-week female fetus. Figure 3 shows the Southern hybridization pattern of telomeric DNA from the 10 tissues isolated from the 72-year-old male. Figure 4 shows scatterplots of telomere integrity data with regression lines comparing blood and skin with age in years. Lastly, Figure 5 shows the average telomere length (maximum DNA peak) and shortest telomere size (overall length of the DNA hybridization signal) for the 9 tissues common to the 20-week fetus and the 72-year-old male. When the overall length of migration of telomeric DNA is similar to the length of the DNA peak migration, then telomere size is most variable. The shortest telomere length was observed in all 9 tissues from the 72-year-old male compared with the fetus. Fat tissue showed the most similarity in telomere findings when comparing the fetus and the 72-year-old male. Telomeric DNA isolated from blood showed the greatest differences.

Figure 2.

Southern hybridization pattern of telomere DNA isolated from 16 different tissues from a 20-week female fetus. DNA from smaller telomeres migrates farther by electrophoresis and thus has a longer signal length. DNA marker sizes (in kb) are shown on the left. Lane 1, DNA from blood; lane 2, DNA from skin; lane 3, DNA from fat; lane 4, DNA from fascia; lane 5, DNA from heart; lane 6, DNA from lung; lane 7, DNA from thymus; lane 8, DNA from spleen; lane 9, DNA from kidney; lane 10, DNA from adrenal; lane 11, DNA from pancreas; lane 12, DNA from liver; lane 13, DNA from stomach; lane 14, DNA from brain; lane 15, DNA from placenta; lane 16, DNA from ovary.

Figure 3.

Southern hybridization pattern of telomeric DNA isolated from 10 different tissues from a 72-year-old male. DNA from smaller telomeres migrates farther by electrophoresis and thus has a longer signal length. DNA marker sizes (in kb) are shown on the left. Lane 1, DNA from blood; lane 2, DNA from skin; lane 3, DNA from heart; lane 4, DNA from lung; lane 5, DNA from liver; lane 6, DNA from pancreas; lane 7, DNA from small intestine; lane 8, DNA from large intestine; lane 9, DNA from brain; lane 10, DNA from lymph node.

Figure 4.

Scatterplots of telomere integrity variables for both blood and skin versus age in years (20-week fetus represented as 0 years) with computed linear regression lines (thin line, blood; heavy line, skin).

Figure 5.

Histogram representing the telomeric DNA length (in kb) among the nine tissues common to the 20-week fetus and 72-year-old comparing the overall length of the DNA hybridization signal (representing the shortest telomeres) and the maximum DNA peak (representing the average telomere length). In all tissues, the shortest telomeres were observed in the 72-year-old male, with the greatest differences found for the average and shortest telomere sizes in blood.

There was a significant difference in the overall length of the DNA hybridization signal representing the shortest telomere size (matched t-test = −4.7; P < 0.01) and length or width of the DNA peak migration representing the variation in telomere size (matched t-test = −4.3; P < 0.01) between the 9 tissues common to the 20-week fetus and the 72-year-old male. However, average telomere lengths (matched t-test = 2.0; P > 0.05) were not significantly different (see Table 2). The 72-year-old male showed the shortest telomere lengths and the most variation (heterogeneity) in telomere size for all tissues studied with greatest differences observed in blood compared with other tissues. In addition, there was not a significant difference [P > 0.05) in the average telomere size between blood and skin cells, but there was a tendency for shorter telomere sizes in blood compared with skin for all ages of those subjects studied between the 20-week fetus and the 72-year-old male. Fetal telomeric DNA from the 17 tissues studied was more homogeneous in size than was telomere DNA isolated from the 10 tissues of the 72-year-old male. Three tissues (blood, liver, and lung) from the 72-year-old male had shorter telomere length, with more variation in size than did the other tissues with longer DNA migration distances; whereas the telomeres from the 20-week fetus showed shorter DNA migration distances (representing longer telomeres), without as much variation among the tissues. This observation would indicate more uniform telomere size in the fetal tissues, indicating fewer cell divisions in the fetus compared with the elderly adult male.

In the comparison of telomere sizes present in each of the seven hybridization zones from the DNA hybridization pattern or curve (>24 kb; 24–16 kb; 16–9 kb; 9 −7 kb; 7–4 kb; 4 −2 kb; < 2 kb), we found that the calculated average or mode telomere length was generally located in the hybridization zone with the greatest proportion or percentage of telomeric DNA. Table 3 shows the percentage of telomeres represented in each of the seven DNA hybridization zones. The percentage of telomeric DNA from blood for all ages (20 wk fetus, 16 yr, 44 yr, 58 yr, 72 yr) ranged from 0 in zone 7 (<2 kb) to 30.2 in zones 5 (7–4 kb), and the highest percentage recorded was in zone 5. For skin at all ages (20 wk fetus, 16 yr, 44 yr, 58 yr, 72 yr), the percentage of telomeric DNA ranged from 3.1 in zone 7 (<2 kb) to 25.7 in zone 3 (16–9 kb). For blood and skin combined from the 20-week fetus, the percentage ranged from 0 in zone 7 (<2 kb) to 25.3 in zone 5 (7–4 kb) and from 0 in zone 7 (<2 kb) to 29.8 in zone 5 (7–4 kb) for the 72-year old male. There were no obvious differences in the percentage of telomeric DNA in the different zones in blood or skin at all ages; however, differences were noted when comparing the different percentages of telomeric DNA in the seven hybridization zones between the 20-week fetus and the 72-year-old male. The average percentage (±SD) of telomeric DNA found in blood and skin from the 20-week fetus in zone 1 (>24 kb) was 12.1 ± 5.0 and 3.4 ± 1.4 for the 72-year-old male. The average percentage (±SD) of telomeric DNA found in blood and skin from the fetus was 5.3 ± 7.4 in zone 6 (4–2 kb) and 18.9 ± 9.2 for the 72-year-old male. The average percentage of telomeric DNA found in each of the remaining hybridization zones was similar between the fetus and the 72-year-old male. Therefore, the greater proportion or percentage of telomeric DNA for the 72-year-old male was found in the zones of the hybridization curve with shorter DNA length [e.g., zone 6 (4–2 kb size)]. These data farther support the notion that shortening of the telomere length occurs with aging.

Table 3.

Percentage of telomeres represented in each of the DNA hybridization zones

| 20-wk fetus | 16 years | 44 years | 58 years | 72 years | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hybridization zone | Blood | Skin | Blood | Skin | Blood | Skin | Blood | Skin | Blood | Skin |

| 1 (>24 kb) | 8.5 | 15.6 | 14.7 | 3.6 | 19.2 | 13.9 | 2.3 | 3.7 | 2.4 | 4.4 |

| 2(24–16 kb) | 5.8 | 16.3 | 25.1 | 21.8 | 9.4 | 9.2 | 9.0 | 8.6 | 6.7 | 10.5 |

| 3(16–9.4 kb) | 18.0 | 34.5 | 43.0 | 36.6 | 19.1 | 17.9 | 32.2 | 19.3 | 15.6 | 20.2 |

| 4(9.4–6.6 kb) | 15.3 | 24.8 | 17.2 | 25.3 | 20.7 | 17.4 | 29.3 | 17.2 | 18.8 | 24.1 |

| 5(6.6–4.4 kb) | 41.8 | 8.8 | 0.0 | 12.6 | 24.8 | 27.2 | 22.9 | 26.9 | 31.1 | 28.4 |

| 6(4.4–2.3 kb) | 10.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.8 | 14.2 | 4.3 | 18.4 | 25.4 | 12.4 |

| 7(<2.3 kb) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 5.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

In summary, we found differences in telomere length, particularly shorter telomeres, and more variation in telomere size in older subjects from different tissues within an individual subject and in vivo age effects within any one subject’s somatic cells. The average telomere lengths were similar despite more heterogeneity with advancing age. Additional studies are underway to further characterize these differences and to understand the variation in telomere size and its relation, if any, with telomerase activity (required to maintain telomere integrity) in normal and malignant cells as well as in the embryonic cell origin of the variation tissues studied. A better description of telomere integrity in cells from normal tissue will allow for a better understanding of the role of the telomere (and telomerase activity) in malignancy and its unlimited cell growth.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lisa Woods and Annis Marney for expert preparation of this manuscript. This research was partly supported by a University Research Council grant from Vanderbilt University (M.G.B.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Allshire RC, Dempster M, Hastie ND (1989): Human telomeres contain at least three types of G-rich repeats distributed non-randomly. Nucleic Acids Res 17:4611–4627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moyzis RK, Buckingham JM, Cram LS, Dani M, Deaven LL, Jones MD, Meyne J, Ratliss RF, Wu J-R (1988): A highly conserved repetitive DNA sequence, (TTAGGG)n, present at the telomeres of human chromosome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 85:6622–6626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blackburn EH (1990): Telomeres and their synthesis. Science 249:489–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwartz HS, Allen GA, Butler MG (1990): Telomeric associations. Appl Cytogenet 16:133–137. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwartz HS, Butler MG, Jenkins RB, M iller DA, Moses HL (1991): Telomeric associations and consistent growth factor overexpression detected in giant cell tumor of bone. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 56:263–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwartz HS, Juliao SF, Sciadini MF, M iller LK, Butler MG (1995): Telomerase activity and oncogenesis in giant cell tumor of bone. Cancer 75:1094–1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butler MG, Sciadini M, Hedges LK, Schwartz HS (1996): Chromosome telomere integrity of human solid neoplasms. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 86:50–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nurnberg P, Thiel G, Weber F, Epplen JT (1993): Changes of telomere lengths in human intracranial tumors. Hum Genet 91:190–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harley CB, Futcher AB, Greider CW (1990): Telomeres shorten during aging of human fibroblasts. Nature 345:458–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmitt H, Blin N, Zankl H, Scherthan H (1994): Telomere length variation in normal and malignant human tissues. Genes Chromosom Cancer 11:171–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harley CB, Villeponteau B (1995): Telomeres and telomerase in aging and cancer. Curr Opin Genet Dev 5:249–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamada O, Oshimi K, Motoji T, Mizoguchi H (1995): Telomeric DNA in normal and leukemic blood cells. J Clin Invest 95:1117–1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adamson DJA, King DJ, Haites NE (1992): Significant telomere shortening in childhood leukemia. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 61:204–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hastie ND, Dempster M, Dunlop MG, Thompson AM, Green DK, Allshire RC (1990): Telomere reduction in human colorectal carcinoma and with aging. Nature 346:866–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwartz HS, Dahir GA, Butler MG (1993): Telomere reduction in giant cell tumor of bone and with aging. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 71:132–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vaziri H, Schachter F, Uchida I, Wei L, Zhu X, Effros R, Cohen D, Harley CB (1993): Loss of telomeric DNA during aging of normal and trisomy 21 human lymphocytes. Am J Human Genet 52:661–667. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Butler MG, Dahir GA, Schwartz HS (1993): Molecular analysis of transforming growth factor beta in giant cell tumor of bone. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 66:108–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]