Abstract

Cells need to consistently synthesize and degrade proteins. Maintaining a balanced level of protein in the cell requires a carefully controlled system and significant energy. Degradation of unwanted or damaged proteins into smaller peptide units can be accomplished by the proteasome. The proteasome is composed of two main subunits. The first is the core particle (20S CP) and within this core particle are three types of threonine proteases. The second is the regulatory complex (19S RP) that has a myriad of activities including recognizing proteins marked for degradation and shuttling the protein into the 20S CP to be degraded. Small molecule inhibitors to the 20S CP have been developed and are exceptional treatments for multiple myeloma. 20S CP inhibitors disrupt the protein balance leading to cellular stress and eventually cell death. Unfortunately, the 20S CP inhibitors currently available have dose-limiting off-target effects and resistance can be acquired rapidly. Here we discuss small molecules that have been discovered to interact with the 19S RP or a protein closely associated with 19S RP activity. These molecules still elicit their toxicity by preventing the proteasome from degrading proteins, but do so through a different mechanism of action.

Graphical Abstract

For ubiquitin-dependent degradation of proteins, the 20S core particle of the proteasome must be associated with the 19S regulatory particle. Limiting protein degradation by inhibiting the core particle with small molecules has been well established. Affecting the myriad activities of the regulatory particle has recently also been shown to be beneficial in a variety of disease models.

1. Introduction

1.1. Protein Degradation by the Proteasome

One of the most essential cellular processes for proliferation and survival is degradation of unwanted proteins in a cell. The build-up of misfolded, oxidized, or no longer required proteins can lead to a myriad of problems and eventually apoptosis. Proteins are degraded by two major pathways.[1] The first is through the process of autophagy. The autophagy pathway involves delivering cargo, which can be protein aggregates, damaged organelles, or other large cytoplasmic materials, to the lysosome. Once the cargo reaches the lysosome, it is degraded by hydrolases to generate amino acids that can be used as building blocks for new proteins. The second protein degradation pathway uses an enzyme complex known as the proteasome. The proteasome is responsible for degrading up to 80% of unwanted proteins in a cell,[2] therefore a significant amount of proteasome is required to accomplish this goal. It has been estimated that 2% of a cell’s protein content is proteasome-related.[3] Originally discovered in the 1970’s,[4,5] a recent resurgence of targeting the proteasome as a therapeutic target has emerged.

The proteasome is composed of two main components. The first component is the core particle, or 20S CP, which is made up of 14 different protein subunits. There are two copies of each protein to generate a barrel-shaped particle with four heptameric rings (α1-7-β1-7-β1-7-α1-7). The alpha-rings form a gate that limits the undesired degradation of proteins and form essential contacts with the other main proteasome component, the 19S regulatory particle (19S RP), Figure 1.[6] The hydrolysis activity of the proteasome is carried out within the beta-rings. The 20S CP cleaves proteins with three different types of activity: β1- caspase-like activity, β2- trypsin-like activity, and β5- chymotrypsin-like activity. All three active sites use a catalytically active N-terminal threonine to hydrolyze peptide bonds. The other beta subunits do not have any catalytic activity and serve a structural role to aid in assembly of the core particle.

Figure 1.

Cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) structure of the 26S proteasome that was released in 2016. (PDB code: 5GJR)

The 20S CP can either be in its free form or capped with the 19S RP. When the 20S is not capped with the 19S RP, disordered proteins without any ubiquitination can passively enter through the gate formed by the α-subunits. When the 20S CP is capped with the 19S RP, the pool of proteins that can be degraded significantly increases. Technically, the 20S CP can be doubly capped by the 19S RP since it has two α-rings, but the single capped form is much more prevalent in the cell.[7] The single capped form, commonly referred to as the 26S, is the proteasome isoform whose activity is the most critical for a cell to survive and is responsible for ubiquitin-dependent degradation of proteins.

If a protein has been misfolded or is no longer needed by a cell, it gets tagged with a small protein called ubiquitin through a multi-step process, Figure 2. A chain of 4-5 ubiquitin moieties must be appended to a protein of interest in order to engage with the 26S proteasome.[8] More specifically, the chain of ubiquitin moieties appended to the protein of interest are required to interact with one or both of the ubiquitin receptors within the 19S RP. After interaction with ubiquitin, the 19S RP is responsible for removing the ubiquitin moieties, recruiting other deubiquitinases (DUBs) if required, unfolding the protein into a linear scaffold to allow passage into the core particle for degradation. The protein is then hydrolyzed by the 20S CP with caspase-like, trypsin-like, and chymotrypsin-like specificity to generate peptides between 3-22 amino acids in length.[9] These peptides can be further degraded into smaller units by other cellular proteases and re-used for new protein synthesis.[10]

Figure 2.

The ubiquitination cascade starts with the E1 enzyme, which activates ubiquitin (Ub). E1 then passes activated ubiquitin to the E2 enzyme. The E2-ubiquitin complex can then interacts with an E3, which is the ubiquitin ligase. This complex can transfer ubiquitin to the substrate (S). This process is repeated until the substrate has a polyubiquitin chain of 4-5 ubiquitin moieties. This chain can then be recognized by the 19S RP of the proteasome to begin degradation of the substrate.

1.2. Proteasome Core Particle Inhibitors

As previously mentioned, the balance of synthesizing and degrading proteins must be carefully controlled to prevent cell death. The accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins leads to cellular stress and unwanted side-effects. As proteins begin to accumulate in a cell, the unfolded protein response (UPR) attempts to re-fold the proteins, but eventually this cellular process becomes overwhelmed and programmed cell death occurs.[11] This pathway to cell death is most prevalent in plasma cells, as they produce large amounts of immunoglobulins that must be degraded or re-folded for the cell to survive.[12] When plasma cells become malignant, a cancer called multiple myeloma (MM) develops.

Proteasome inhibition was originally hypothesized to be helpful in treating cachexia in cancer patients,[13-15] however, preclinical studies in cancerous cell lines, including MM, suggested inhibitors could be potential chemotherapeutic agents. It was initially believed that 20S CP inhibitors lead to cell death by preventing the degradation of IκB, the endogenous inhibitor of NF-κB.[12] When IκB is present, NF-κB cannot translocate to the nuclease to regulate gene expression. While this mechanism plays a role in cell death, 20S CP inhibitors are typically considered cytotoxic because they prevent protein degradation, which has a trickle-down effect to other cellular processes that lead to cell death if disrupted. It has also been hypothesized that inhibition of protein catabolism by the proteasome results in cell starvation, disrupting the cell’s ability to synthesize new proteins, and therefore, cell death.[16]

The first 20S CP inhibitor, bortezomib, was approved by the FDA in 2003.[17] Bortezomib is a covalent, reversible inhibitor (Figure 3A). It contains a boronic acid moiety that can form a bond with the N-terminal threonine of the β5 subunit of the 20S proteasome. At higher concentrations, it can also interact with the β1 and β2 subunits.[18] Bortezomib can be used alone or in combination with other small molecules, such as dexamethasone or lenalidomide to treat MM.[19] Unfortunately, patients often experience peripheral neuropathy if bortezomib is administered at high concentrations or over long periods of time.[20]

Figure 3.

Structures of 20S CP inhibitors. (A) Bortezomib is a tripeptide that reversibly inhibits β5 catalytic activity utilizing a boronic acid moiety. (B) Carfilzomib is a tetrapeptide that irreversibly inhibits β5 catalytic activity via an epoxyketone.

To circumvent the limited dosing-window, a second generation of proteasome inhibitors were developed that did not contain the boronic acid, but instead included an epoxyketone moiety. The epoxyketone forms an irreversible covalent bond with the N-terminal threonine.[21] The second-generation inhibitors were designed like this with the hypothesis that the proteasome would be inhibited longer because the covalent bond was not reversible, in contrast to the boronic acid in bortezomib. The most well studied epoxyketone inhibitor of the proteasome is carfilzomib (Figure 3B), which was approved in 2012 by the FDA.[22] While treating with carfilzomib successfully lowered the rate of patients that experienced peripheral neuropathy, additional cardiovascular complications were discovered.[23]

While these two molecules, along with a variety of combination therapies, has revolutionized the way that MM and mantle-cell lymphoma is treated, there is a need for molecules that still target the proteasome but do so through a different mechanism of action. Both bortezomib and carfilzomib can inhibit the ubiquitin-dependent and -independent pathways of protein degradation because they target only the core particle. Small molecules that can disrupt only the ubiquitin-dependent pathway by inhibiting one of the 19S RP subunits could be less toxic or and used in combination with a core particle inhibitor. Since the undesired effects of bortezomib and carfilzomib are related to dose, a lower dosage could potentially be used along with a 19S RP inhibitor. Here, we describe a number of 19S RP subunits, Table 1,[24] that currently have small molecule inhibitors or binders that can lead to toxicity in a variety of different cancer cell lines. Many of these molecules highlight the potential of dual-dosing with a 20S CP and 19S RP inhibitor, and some are effective against 20S CP-inhibitor resistant cells.

Table 1.

List of 19S RP subunits, their gene name, MW, and known activities.

| Subunit Name | Gene code (Human) |

MW* (kDa) |

Role in 19S RP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rpt-1 | PSMC2 | 48.6 | ATPase |

| Rpt-2 | PSMC1 | 49.2 | ATPase, Gate-opening |

| Rpt-3 | PSMC4 | 47.4 | ATPase, Gate-opening |

| Rpt-4 | PSMC6 | 44.2 | ATPase |

| Rpt-5 | PSMC3 | 49.2 | ATPase, Gate-opening |

| Rpt-6 | PSMC5 | 45.6 | ATPase |

| Rpn-1 | PSMD2 | 100.2 | Proteasome-interacting proteins scaffold |

| Rpn-2 | PSMD1 | 105.8 | Proteasome-interacting proteins scaffold |

| Rpn-3 | PSMD3 | 61.0 | Non-ATPase, Assembly component |

| Rpn-5 | PSMD12 | 52.9 | Non-ATPase, Assembly component |

| Rpn-6 | PSMD11 | 47.5 | Non-ATPase, Assembly component |

| Rpn-7 | PSMD6 | 45.5 | Non-ATPase, Assembly component |

| Rpn-8 | PSMD7 | 37.0 | Non-ATPase, Assembly component |

| Rpn-9 | PSMD13 | 42.9 | Non-ATPase, Assembly component |

| Rpn-10 | PSMD4 | 40.7 | Ub receptor |

| Rpn-11 | PSMD14 | 34.6 | DUB |

| Rpn-12 | PSMD8 | 39.6 | Non-ATPase, Assembly component |

| Rpn-13 | ADRM-1 | 42.1 | Ub receptor, Uch37 recruiter |

| Rpn-15 | DSS-1 | 8.3 | Non-ATPase, Assembly component |

gene names were used in the Uniprot database to determine roles and MW

2. Small Molecule Inhibitors of subunits of the 19S RP

2.1. Ubiquitin Receptors

The 26S proteasome has two ubiquitin receptors in the 19S RP: Rpn-10 and Rpn-13. Rpn-10 (originally called S5) was first reported in 1994,[25] and Rpn-13 was first identified in humans as a proteasome subunit in 2006.[26-28] These ubiquitin receptors are positioned at the apex of the 26S proteasome, allowing for accessible capture of polyubiquitinated substrates for degradation. Rpn-13 has one ubiquitin interacting surface, whereas Rpn-10 contains two ubiquitin interacting motifs (UIMs) that can bind to ubiquitin chains simultaneously and at different affinities.[29] It is proposed that polyubiquitinated substrates bind to Rpn-10 before binding to Rpn-13 or they bind through a cooperative effect.[30,31]

In mice, mutation of Rpn-10’s UIM has been observed to be lethal,[32] but Rpn-13 is non-essential and Rpn-13-siRNA (small-interfering RNA) knockdown decreases MM cell viability.[33,34] Rpn-13 has been a more attractive target than Rpn-10 because Rpn-13 is non-essential in healthy cells is overexpressed in a variety of cancers, including MM, ovarian, and gastric cancer.[34-36] Without Rpn-13, Rpn-10 can handle the normal protein loads for proteasome degradation in healthy cells; but since MM cells have a higher volume of misfolded and immunoglobulin proteins, it is hypothesized that Rpn-13’s assistance in ubiquitin recognition for proteasomal degradation is required for the survival and proliferation of these diseased cells.[34]

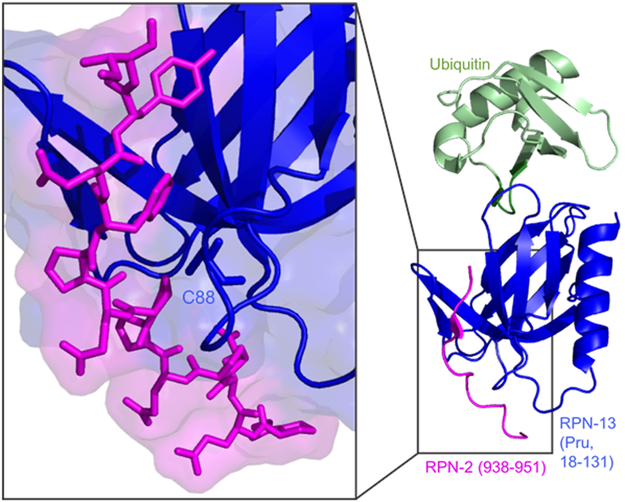

Rpn-13’s structure alone and with its binding partners has been well-characterized over the past ten years by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and x-ray crystallography. Rpn-13 has three main protein binding partners, which allows it to interact with the 19S RP, as well as DUBs and ubiquitin, Figure 4A. Rpn-13 contains a N-terminal Pru (pleckstrin-like receptor for ubiquitin) domain which interacts with ubiquitin and Rpn-2.[37,38] These Pru domain interactions allow Rpn-13 to dock onto the 19S RP and also interact with the polyubiquitinated substrate for degradation. Followed by the Pru domain is a disordered region of more than 130 amino acids, and at its C-terminus is a DEUBAD (DEUBiquitinase Adaptor) domain that interacts with a DUB, Uch37.[39] Human Rpn-13’s full-length structure was elucidated by NMR in 2010, Figure 4B.[40]

Figure 4.

(A). Schematic of Rpn-13’s interactions with Uch37, Ub, and Rpn-2. (B) Solution structure of full-length Rpn-13 solved in 2010, with the DEUBAD (orange) and Pru (blue) domain indicated. (PDB: 2KR0)

There are two known inhibitors of Rpn-13: a covalent irreversible chalcone called RA190 and a non-covalent reversible peptoid called KDT-11. RA190 was discovered in 2013 during optimization of the activity and solubility of previously reported chalcones,[41] such as AM114, which are known to inhibit ubiquitin-mediated protein degradation.[42,43] RA190 has been observed to cause accumulation of polyubiquitinated proteins, trigger the UPR, and lead to eventual cell apoptosis. This mechanism of action can overcome bortezomib-resistant cell lines and also has promising anti-cancer activity towards MM, ovarian, and cervical cancer.[41,43] RA190 (20 mg/kg/day, i.p. administration) was demonstrated to inhibit tumor growth in NOG mice carrying a NCI-H929 MM line and in a xenograft model of ovarian cancer immunocompromised mice.[41] Further in vivo applications have shown that the RA190 scaffold and its mechanism of inhibition is promising for the treatment of ovarian cancer.[44,45]

Although glycerol gradient studies have shown RA190 to not displace Rpn-13 from the 26S proteasome, NMR studies support that RA190 binds to Rpn-13’s Cys-88 in the Pru domain near the Rpn-13:Rpn-2 interface, which could disrupt Rpn-13’s ability to dock onto the 19S RP, highlighted in Figure 5.[38] RA190 was initially observed to bind to Cys-88 in the Pru domain, but it has also been reported that RA190 can react with Cys-357 in the DEUBAD domain and possibly other surface exposed cysteine residues.[37] Changes in RA190’s structure, such as the introduction of electron-withdrawing p-nitro groups in compound RA183, have enhanced potency and binding to Rpn-13’s Cys-88 residue. Despite this enhancement, RA183 was still shown to be non-selective and bound to Rpn-13’s DEUBAD domain, as well as DUBs Usp14 and Uch37.[46]

Figure 5.

Close-up of the Pru domain Rpn-13:Rpn-2 interface, with Cys-88 (RA-190’s binding residue) highlighted. (PDB: 5V1Y)

KDT-11, the second Rpn-13 known inhibitor, was discovered in 2015 through a one-bead one-compound (OBOC) peptoid library screen of 100,000 compounds.[47] Binding Rpn-13 with a modest affinity of 2 μM, KDT-11 has also been observed to cause accumulation of polyubiquitinated proteins in MM cells, similar to RA190 and known 20S CP β5 inhibitors, leading to eventual cell apoptosis. This accumulation of polyubiquitinated proteins was also selective towards cells that require high proteasomal activity for cell proliferation and survival, such as MM but not HEK-293T cells. While the binding surface of KDT-11’s surface remains unknown, competitive fluorescence polarization (FP) assay has shown that KDT-11 does not bind to the same surface RA-190 or Lys48-linked penta-ubiquitin chains, suggesting KDT-11 could instead disrupt the Uch37:Rpn-13 interaction or bind to a novel surface on Rpn-13. KDT-11 has also been observed to be selective for Rpn-13 in MM cells by affinity chromatography, but despite the selectivity advantage that KDT-11 has over RA190, improvement of KDT-11’s physical properties are required for further in vivo investigation.

Along with RA190 and KDT-11 inhibitors, there have also been efforts of generating peptide-based strategies for inhibiting Rpn-13 function.[48] In 2015, a truncated Rpn-2 peptide (916-953) was reported to bind Rpn-13 with 12 nM affinity, and overexpression of this peptide in HEK-293T cells led to an accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins. Furthermore, in 2017, alanine point mutants of the Rpn-2 peptide (938-952) were found to inhibit Rpn-13 with varying Kis from 16.6 to 18,760 nM.[38] These point mutations indicate the key Rpn-2 amino acids for the Rpn-13:Rpn-2 interaction. This specific interaction could serve as a promising target for anti-cancer agents, but more validation is necessary.

Additionally, there has been recent development of another competitive FP assay that includes fluorescently-labeled monoubiquitin bound to the Uch37:Rpn13 complex and then competed off with unlabeled ubiquitin chains. This competitive FP assay was demonstrated to be amenable for high-throughput screening to discover competitors that disrupt the Uch37:Rpn-13 complex’s interaction with monoubiquitin.[49] Inhibition of this complex’s binding to ubiquitin is not yet well-studied.

2.2. Deubiquitinases

The ubiquitination and deubiquitination of a protein heavily relate to protein function, cell cycle, signaling transduction, cell growth, and endoplasmic-reticulum-associated degradation (ERAD).[50] After the ubiquitinating process and recruitment by ubiquitin receptors Rpn-10 and Rpn-13, the 19S RP utilizes three primary proteins called deubiquitinases or DUBs for the removal of ubiquitin from the substrate. These DUBs are ubiquitin-specific protease 14 (Usp14), ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase (Uch37, also known as UCH-L5), and regulatory particle non-ATPase 11 (Rpn-11). Ubiquitin is a small 8.6 kDa protein found in all cells, and it can attach itself to another ubiquitin to form a polyubiquitin chain, as previously seen in Figure 2, that can connect at eight different locations within ubiquitin. These different positions on ubiquitin includes seven lysine residues and an N-terminal methionine.[51,52] Since these ubiquitin chains can be attached at different positions, the DUBs have different ways to compensate for many types of substrates: (1) Uch37 (a thiol protease) is activated by binding to Rpn-13 and trims ubiquitin from the distal end of the chain,[53] (2) Usp14 (also a thiol protease) binds to Rpn-1, can release di- and tri-ubiquitin from the chain or remove the entire ubiquitin chain from the substrate,[54] and (3) Rpn-11 (an intrinsic 19S RP subunit and a metalloprotease) deubiquitinates at the proximal end of the chain.[55] While most proteasomal substrates are Lys48-linked polyubiquitin chains, Uch37 and Usp14 have also been observed to remove the Lys63 polyubiquitin chain (but Lys63-linked proteins are mostly considered to be nonproteolytic related). [56,57]

It has been shown that early removal of the ubiquitin chain could result in weakening the binding of the target protein with the 19S RP, and limiting the amount of proteasome degradation.[53,54] Rpn-11 is different from Usp14 and Uch37 since it is proposed that Rpn-11 deubiquitinates the substrate after it is committed to degradation and after the proteasome’s ATPases have engaged with the substrate.[53] Each of these DUBs strongly influence the function of the 26S proteasome by different mechanisms and have been thoroughly studied as potential targets for cancer therapy.

Usp14 inhibitors

Usp14’s N-terminal ubiquitin-like domain (UBL) docks onto the proteasome through interacting with Rpn-1’s T2 domain.[58][58,59][57,58][53,54][52,53][49,50][48,49][46,47][45,46] A 2016 cryo-EM structure at 4.35 Å resolution was solved of the 26S proteasome bound to the Usp14-ubiquitin aldehyde complex (UbAl, a covalent inhibitor of Usp14 where the C-terminal carboxylate is replaced with an aldehyde), Figure 6A.[6] It displayed Usp14’s proximity to Rpn-1 (although the UBL domain appeared to have no density due to its flexibility), and Rpn-1’s position in the 19S RP was observed to undergo the most movement (50-60 Å) when bound to Usp14.[6] While the UBL domain interacts with Rpn-1, Usp14 also interacts with Rpt-1 and Rpt-2 oligosacharide-binding domains to further help dock itself onto the proteasome. After the UBL domain, Usp14 has a 45 kDa catalytic domain, which has three regions (thumb, finger, and palm) that undergo conformational changes (specifically two surface loops, BL1 and BL2, above the catalytic cleft) when bound to UbAl.[60]

Figure 6.

(A) Cryo-EM structure showing Usp14’s and UbAl’s position when docked onto the 19S RP. (PDB: 5GJQ) (B) Co-crystal of USP14’s catalytic domain and IU1 demonstrating the binding pocket of IU1. (PDB: 6IIK).

The first reported general DUB inhibitor was UbAl, but it was not selective towards specific DUBs.[61] The first selective DUBs inhibitor was IU1 which was discovered through screening over 63,000 compounds using a fluorescence assay using ubiquitin-7-amino-4-methylcoumarin (Ub-AMC) as a reporter and vinylsulfone-proteasomes (VS-proteasomes).[62,63] IU1 was shown to inhibit Usp14, resulting in proteasome activity promotion. The small molecule was also selective towards Usp14, but the mechanism of Usp14 inhibition is unclear. Although the possible mechanism of IU1 on neurotoxicity was explained and a better inhibitor IU1-47 was published in 2017, the mechanism of IU1 inhibition was not demonstrated until recently. [64,65] The co-crystal structure of IU1 with Usp14’s catalytic domain, Figure 6B, was obtained and found that IU1 acts through a steric blockade mechanism. Binding to the thumb-palm cleft region, IU1’s binding prevents ubiquitin from reaching the catalytic cysteine for deubiquitination. After the characterization of IU1’s binding pocket in Usp14’s catalytic domain, structure-guided optimization led to the discovery of a 10-fold more potent inhibitor of Usp14 called IU1-248.[66] The addition of a hydroxyl group to IU1-248’s showed improved solubility as compared to IU1, and the incorporation of an electron-withdrawing cyano group on the benzene ring enhanced π-π stacking.

The development of α,β-unsaturated ketones as Michael acceptors for DUB thiol activity have also been used to explore the potential of DUB inhibition. In 2011, a dual inhibitor of both Usp14 and Uch37 called b-AP15 was discovered.[67] Despite the non-selectivity of b-AP15, it was observed to overcome bortezomib resistance in MM cells.[68] With further improvements on b-AP15, VLX1570 (which is approved for clinical trials in combination with dexamethasone) was then discovered to be more selective towards Usp14, was more soluble, and had better plasma stability.[69]

Uch37 inhibitors

Uch37 currently has no selective inhibitors. As mentioned previously, b-AP15 targeted Uch37 but was not selective.[67] Later in 2013, AC17 was reported to be an irreversible DUB inhibitor and was initially found during the synthesis of 4-arylidene curcumin analogs for the search of NF-κB pathway inhibitors.[70,71] While AC17 is selective for 19S RP deubiquitinase activity in cells, it still has multiple targets within the 19S RP. Understanding the mechanism of inhibition to known Uch37 inhibitors is required before further studies can be undertaken.

Rpn-11 inhibitors

Recent studies have demonstrated that Rpn-11-siRNA knockdown decreases MM cell viability, and that Rpn-11’s inhibition activates the caspase cascade and endoplasmic stress response signaling, which can overcome bortezomib resistance.[72] Deubiquitinating activity of Rpn-11 occurs in a motif within the MPN (Mpr1, Pad1 N-terminal) domain.[73] This motif is referred to as a JAMM motif, or Jab1/Pad1/MPN domain metalloenzyme, and its active site consists of two histidines and an aspartic acid coordinated with a zinc ion, Figure 7.[74] Most structural work so far of Rpn-11 has been done on a heterodimer in complex with Rpn-8 from Saccharomyces cerevisiae.[74-76] X-ray crystallography data at 2.0 Å resolution of the zinc-bound and zinc-free Rpn-11:Rpn-8 heterodimer supports that Rpn-11 stabilizes its substrate with a flexible Insert-1 (Ins-1) loop, which interacts with the distal ubiquitin on the polyubiquinated substrate.[74] Rpn-11’s coordination with zinc and its Ins-1 loop played important roles in the discovery of the first class of Rpn-11 inhibitors.

Figure 7.

X-ray crystal structure close-up of S. cerevisiae Rpn-11:Rpn-8 heterodimer to display the Zn2+ ion site on Rpn-11. (PDB: 4O8X)

By fragment-based drug discovery screening, quinoline-8-thiol (8TQ), a fragment with an IC50 value of approximately 2.5 μM for Rpn-11, was identified through a library from a library of metal-binding pharmacophores. Structural optimization to increase potency and decrease off-target effects (for other JAMM proteases and metalloenzymes) led to the discovery of capzimin, a small molecule with an IC50 value of approximately 300 nM for Rpn-11.[77] Capzimin treatment at 10 μM in human colon cancer cell line HCT116 was observed to cause accumulation of polyubiquitinated proteins, as well as increased levels of p53 and Hif1α. Additional computational analysis supported capzimin’s selectivity for Rpn-11 over other JAMM proteins, showing that even though the 8TQ moiety can be promiscuous, capzimin’s thiazole moiety aids in selectivity as it interacts with the distal ubiquitin cleavage site. This important interaction, which includes Rpn-11’s Ins-1 region that is not conserved in other JAMM proteases, contributes greatly for capzimin’s selectivity.[78] While 8TQ has been previously reported to be orally bioavailable and tolerable in mice,[79] capzimin’s in vivo efficacy has yet to be established. Targeting Rpn-11 could be a promising anti-cancer target, but further validation in mouse models of hematological cancers is required.

Another promising scaffold, the reduced form of thiolutin (THL), can inhibit proteins with the JAMM motif. This antibiotic and anti-angiogenic compound can act as a zinc chelator, and was reported to inhibit Rpn-11 activity.[80] However, THL and other dithiopyrrolones (DTP) inhibited other JAMM metalloenzymes as well. Additional structural optimization, similar to 8TQ’s development into capzimin, could potentially increase selectivity of THL and DTPs for Rpn-11.

2.3: ATPases

ATPases associated with diverse cellular activities (AAA proteins) is a family of proteins that are found in all organisms.[81,82] First discovered in the 1970’s,[4] the ATPases related to the proteasome were classified as the classical AAA clade and were highly conserved throughout the archaeal to eukaryotic species, which suggests that the function of proteasomal ATPases remained the same during evolution.[83] Research on the proteasomal ATPase began with archaeal proteasome-activating nucleotidase (PAN) since its a ring of six identical nucleotidase copies is structurally similar to the human proteasome ATPase.[84,85] Later research on PAN demonstrated the highly cooperative activity between ATPases and proteasome. Therefore, human proteasomal ATPases were considered to facilitate proteasome activity similarly to PAN ATPases.

Proteasome’s Rpt subunit inhibitors

In the human proteasome, six distinct ATPases (called Rpt-1 through Rpt-6) form a heterohexameric ring-like structure (Figure 8A)[6] that rest on top of the 20S CP’s alpha subunits.[86] This ATPase ring is responsible for unfolding and shuttling the proteasome’s target proteins for degradation within the 20S CP. Recently, two structural dynamic studies of the human 26S proteasome revealed some interesting protein-protein interactions between the ATPase ring and the alpha ring during protein degradation. During the gate-opening process of degradation, the dynamic studies showed that the ATPase subunits undergo conformational changes and that the degradation of the target protein was a cooperative process by the lid and base of the 19S RP.[87,88]

Figure 8.

(A) Cryo-EM structure of heterohexameric ATPase ring of the Rpt subunits (PDB: 5GJQ) (B) Cryo-EM structure of the homohexameric ATPase ring of p97, with one protomer highlighted (above) and the D1, D2, and N domains indicated (below). (PDB: 5FTK)

In early 2007, a peptoid named as RIP-1 was identified from screening 30,000 compounds.[89] Identification of RIP-1 was through a OBOC peptoid library screen and later target identification was performed by chemical cross-linking using a biotin-dihydroxyphenylalanine (DOPA) conjugate of RIP-1. While the biotin-DOPA-RIP-1 conjugate was observed to only cross-link with Rpt-4 over the other proteasomal ATPases, this particular chemical cross-linking does not denote selectivity and the off-target effects of the compound has yet to be presented. Considering the high abundance of ATPase inside of cells, further research is required to understand it targeting Rpt-4 is a viable mechanism of toxicity.

p97 inhibitors

Besides the ATPase subunits incorporated within the 26S proteasome, p97 (VCP, for Valosin-containing protein) is another ATPase that is highly involved in the UPS.[90] Unlike the Rpt subunits, the homohexameric p97 protein complex is considered to “pick” ubiquitinated proteins from inside the cell and transport them to the 19S RP.[91,92] The most well-studied system using p97 is related to ERAD, in which the proteasome is the destination for degradation of the target protein.[93-95] p97 is also considered to be upregulated in multiple diseases and cancers, highlighting the importance of p97 as a potential therapeutic target.[96,97]

Structural elucidation for p97 has mostly utilized x-ray crystallography, with a full-length 4.4 Å resolution structure resolution of p97 (in complex with adenosine diphosphate, ADP) solved in 2008.[98] A 2.4 Å resolution cryo-EM structure of p97 (in complex with ADP) was more recently solved in 2016, Figure 8B, which mostly agreed with the 2008 structure.[99] Each p97 protomer in its homohexameric structure consists of a N-terminal domain (N domain), two ATPase domains (D1 and D2), and a C-terminal domain.[99] The D2 domain has also been shown to be the major contributor of p97’s ATPase activity, whereas the D1 domain is involved with heat-induced activity under stressed conditions.[100]

Research on p97 inhibition has been more productive than Rpt subunit inhibition, with multiple sites of inhibition being discovered and explored. In 2004, Eeyarestatin I (EerI) was identified as an inhibitor of the ERAD system through a fluorescent high-throughput screen that affected class I major histocompatibility complex (MHC I) turnover.[101] Later in 2010, EerI was observed to have bi-modular functionality, where its aromatic region contributed to recruitment towards the ER membrane and its nitrofuran-containing (NFC) region bound to p97’s D1 domain. This mechanism of inhibition, specifically the NFC module’s interaction with p97, caused cell death with a similar manner to bortezomib.[89]

Competitive inhibition of ATP with p97 has also been thoroughly explored. From a 2011 high-throughput luciferase assay that measured ATP concentration, a library of 16,000 compounds was screened to identify 925 primary hits, and eventually DBeQ, a selective and potent p97 inhibitor, was discovered.[104] DBeQ was found to be selective for p97 over other ATPases and rapidly caused cancer cell death. Further structural-activity relationship (SAR) studies led to the discovery of ML240 and ML241, which were also ATP-competitive. ML240’s effect was similar to DBeQ, but ML241 was less slower in causing cell death, suggesting that pathway-specific inhibitors could affect different p97 substrates.[105] Later in 2015, utilizing DBeQ and ML240 as references, CB-5083 was discovered. CB-5083 was found to be 41% orally bioavailable and selectively bound to the D2 domain over the D1 domain of p97 to induce proteotoxic stress via CHOP (CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein homologous protein) and DR5 (death receptor 5) upregulation. Binding to the D2 domain was proposed to be more favorable since it is the major contributor of p97’s ATPase activity. In 2017, preclinical data of CB-5083 later showed efficacy in several MM models.[106]

Allosteric inhibition of p97 has been examined with the discovery of NMS-873 in 2013, which was identified through a high-throughput screen of a one million compound library using a NADH-coupled assay. NMS-873 was observed to interfere with protein degradation and induce cancer cell death.[107] NMS-873’s allosteric inhibition was proposed to prevent p97’s conformational changes to undergo ATP hydrolysis. Also potentially through an allosteric mechanism, natural product withaferin A was identified from a 968 natural product compound library with a high-throughput ATPase assay, utilizing the highly colored complex of malachite green and phosphomolybdate.[108] Cysteine mutation studies in the D1 and D2 domains revealed that withaferin A and certain analogs lost their inhibition activity with the Cys-522 mutant, suggesting that there was covalent binding to the D2 domain. While withaferin A is not specific for p97, three analogs that were optimized through SAR were identified to cause cell death in lymphoma cell lines.

To further explore the multiple binding site on p97 and its dynamics, a 2485-member fragment library was screened by surface plasmon resonance (SPR), followed by NMR, to identify fragments that bound to the D1 or N domain of p97.[109] Even though this strategy is less high-throughput than previously mentioned assays, it is useful in identifying fragments for p97’s dynamic nature, and the results could be used for further lead optimization of future inhibitors.

As described earlier, there have recently been cryo-EM structures that demonstrate the 26S proteasome’s different states and the dynamic nature of its ATPases.[88] There is now an opportunity to look deeper into the assembly and conformational changes of the ATPase ring to selectively design inhibitors that can interfere with the dynamic process. For p97, the results of CB-5083 is encouraging so far, and further in vivo characterization of CB-5083 treatment alone and in combination of 20S CP inhibitors should be explored.

2.4. Chaperone Proteins

While chaperone proteins are not intrinsically assembled in the 19S RP, they play an important and dynamic role in the regulation of cellular signaling pathways by bringing binding partners together and assisting the proteasome’s overall function, especially under stress conditions. In addition to assistance during ER stress, chaperones proteins have several roles in handling misfolded proteins in relation to the UPS.[110] Examples of chaperones in the UPS are heat shock cognate 70 (Hsc70), heat shock proteins (Hsp90, Hsp70, Hsp40), and gankyrin. While there are efforts going into the discovery of Hsc/Hsp inhibitors, our discussion is focused on gankyrin, due to its oncogenic roles and multiple interactions with the 19S RP[111] and to highlight the recent success in the discovery of its first selective inhibitor.[112]

Gankyrin

Gankyrin is an oncoprotein that contains seven repeats of ankyrin, which is a 33-amino acid sequence consisting of two antiparallel α-helices and a short β-hairpin. Two crystal structures of human gankyrin were published in 2004,[113,114] and its NMR solution structure was then published later in that year.[115] Gankyrin is overexpressed in early hepatocellular carcinomas, is involved in cell cycle regulation, and is a chaperone protein for proteasomal degradation by interacting with the C-terminal of Rpt-3 in the ATPase ring.[116,117] Due to gankyrin’s involvement in cell cycle regulation and its overexpression in various cancers,[118-120] it has been regarded as a potential therapeutic target for the inhibition of cancer cell proliferation.[121]

Using computational docking and the crystal structures available, 21 molecules were designed by predicting binding sites within gankyrin using Ligbuilder 1.2.[122] Molecule 17 exhibited the lowest predicted binding energy into one of gankyrin’s hydrophobic pockets. Although no following studies were found that further explore this de novo approach from 2011, this computational study was one of the first efforts towards discovering a gankyrin inhibitor.

Another study of gankyrin discovered a molecule named LBH589, which was shown to downregulate the gankyrin/STAT3/Akt pathway, but unfortunately it had poor selectivity properties.[123] In 2016, a small molecule inhibitor called cjoc42 was discovered through a small molecule diversity screen using a thermal shift assay. In this assay compounds were considered binders if they increased gankyrin’s melting point greater than or equal to 0.5 °C.[112] With an affinity of 630 nM to gankyrin, cjoc42 was observed to bind to the Rpt-3 binding surface by NMR, thus preventing the interaction of Rpt-3 and gankyrin. Cjoc42 was also observed to enhance p53 levels in vitro. Further studies showed that cell proliferation was halted with cjoc42 inhibition in liver cancer cell lines, and in vivo characterization of this small molecule is ongoing.[124]

3. Summary and Outlook

The inhibition of the proteasome leads to an accumulation of unwanted proteins in a cell and eventually cell death. Perturbing the protein-load balance in healthy cells can be moderately tolerated but is lethal to a variety of cancers that produce an excess amount of protein. This high dependence on proteasome activity in some cancer types, especially hematological cancers, led to the development of a variety of proteasome core particle inhibitors. Small molecule inhibitors of the proteasome, such as bortezomib, have been shown to increase the median overall survival and increase progression free time for those suffering from MM.[125]

In addition to the side effects of covalent inhibitors to the core particle of the proteasome previously described, resistance can also occur rapidly. While the mechanism of resistance is currently unknown, small molecules that target other subunits within the 26S proteasome system could prove to overcome this resistance but still be as efficacious as the core particle inhibitors. Alternative proteasome inhibitors that target one of the 19S RP subunits have recently been demonstrated to accomplish this goal and are summarized in Table 2. The most success in targeting the 19S RP has been demonstrated by discovering small molecules that interfere with Rpn-13, the non-essential ubiquitin recognition subunit, and Rpn-11, the proteasome’s DUB. Targeting either of these 19S RP subunits with a small molecule is cytotoxic to MM, and a few have been demonstrated to be effective in bortezomib-resistant cell lines.

Table 2.

Summary Table of 19S RP inhibitors.

| Target | Compound Name |

Structure | Identification Method |

Mechanism of Action |

Potency | Selectivity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rpn-13 | RA190 |  |

Optimization of previously reported chalcones | Michael Addition (Rpn-13’s Cys-88) | 100 nM | Can also covalently bind to Rpn-13’s Cys-357 and other DUBs | Anchoori 2013 |

| KDT-11 |  |

OBOC Peptoid Library Screen | Unknown | 2 μM | Selective for Rpn-13 through pull-down assay of MM lysate | Trader 2015 | |

| RA183 |  |

Improving potency of RA190 | Michael Addition (Rpn-13’s Cys-88) | 40 nM | Can also covalently bind to Rpn-13’s Cys-357 and other DUBs | Anchoori 2018 | |

| Usp14 | VLX1570 |  |

Optimization of b-AP15 | Michael addition | 10 μM | Selective for USP14 | Wang 2015 |

| IU1 |  |

Ub-AMC Fluorescent HTS Assay | ATP Competitive Inhibitor | 4-5 μM | Selective for USP14 | Lee 2012 | |

| IU1-248 |  |

Optimization of IU1 | ATP Competitive Inhibitor | 0.83 μM | Selective for USP14 | Wang 2018 | |

| Uch37 and Usp14 | b-AP15 |  |

NCI screening | Michael Addition | 0.8 μM | Not selective, USP14 and UCHL5 and possibly the 20S also | Berndtsson 2009, D’arcy 2011 |

| Uch37 | AC17 |  |

Initially from Screening for NF-κB pathway inhibitors | Michael Addition | 4.3 μM | Selective for 19S RP DUB activity, but not selective for a specific DUB | Zhou 2013 |

| Rpn-11 | 8TQ |  |

Fragment-Based Drug Discovery with Metal-Binding Pharmacophores | Binds to Rpn-11’s catalytic Zn2+ ion in bidentate manner | 2.5 μM | Non-specific towards JAMM proteases | Perez 2017 |

| Capzimin |  |

Optimization of 8TQ | Binds to Rpn-11’s catalytic Zn2+ ion in bidentate manner | 300 nM | >5-fold selectivity for Rpn-11 over other JAMM proteases | Li 2017 | |

| Rpt-4 | RIP-1 |  |

OBOC Peptoid Library Screen | Unknown | 3.0 μM | Not selective for Rpt-4 | Lim 2007 |

| p97 | EerI |  |

Fluorescent HTS Assay for MHC I turnover | Binds to the D1 domain of p97 | 5-10 μM | Dual binder of the ER membrane and p97 | Fiebiger 2004, Wang 2020 |

| DBeQ |  |

Luciferase HTS Assay | Competitive binding with ATP | 1.6 μM | Selective for p97 | Chou 2011 | |

| ML240 |  |

SAR studies with DBeQ | Competitive binding with ATP | 0.11 μM | Selective for p97 | Chou 2013 | |

| ML241 |  |

SAR studies with DBeQ | Competitive binding with ATP | 0.11 μM | Selective for p97 | Chou 2013 | |

| NMS-859 |  |

NADH-coupled HTS Assay | Non-competitive with ATP; Covalently Binds to Cys-522 | 2.66 μM | Selective for p97 | Magnaghi 2013 | |

| CB-5083 |  |

Optimization of DBeQ and ML240 | Competitive binding with ATP | 11 nM | Selective for p97 | Anderson 2015 | |

| Gankyrin | cjoc42 | Diversity-Oriented Screening with Thermal Shift Assay | Binds to gankyrin’s Rpt-3 binding surface | 630 nM | Selective for gankyrin | Chattopadhyay 2016 |

There still remains a number of potential protein targets within the 19S SP that may be amenable to interacting with a small molecule inhibitor, Figure 9. Very few of the 19S RP protein subunits have enzymatic activity, therefore molecules that interrupt an essential binding event may need to be created. For example, Rpn-6 is considered the “hinge” of the proteasome as it makes essential protein-protein interactions between other 19S RP subunits and the 20S CP.[126] These interactions are required to completely form the 26S to perform ubiquitin-dependent degradation of proteins. One could imagine that a small molecule could be discovered that could prevent the loading of the 19S RP onto the 20S CP or prevent Rpn-6 from interacting with the other 19S RP subunits. Discovery of these types of molecules could be accomplished by screening libraries of compounds to purified Rpn-6 and using methods such as a thermal shift assay or OBOC binding assays. Screening of DNA-encoded libraries, which can include millions of compounds, could also be applied. Discovery of ligands to Rpn-2, the only subunit with direct contacts with Rpn-13, could also be beneficial. Peptides that interrupt this protein-protein interaction have been demonstrated.[38]

Figure 9.

There remains a large number of 19S RP subunits that that may be amenable to inhibition by small molecules. Additionally, preventing PTMs or designing PROTACs to overexpressed subunits may also be viable methods to disrupt proteasome activity.

Another method to disrupt the activity of the 19S RP would be to prevent post-translational modifications, such as the phosphorylation of several of the subunits. Various subunits of the 19S RP can become phosphorylated, which then leads to an increase in proteasome activity.[127] Protein kinase A (PKA) has been shown to phosphorylate Ser-14 of Rpn-6. Proteasomes that have a phosphorylated Rpn-6 have higher peptidase activities. Conversion of this serine to an alanine, which cannot be phosphorylated, showed a decrease in protease activity. Blocking the interaction of PKA and Rpn-6 could be an interesting method to dampen the activity of the proteasome. Other subunits such as Rpt-3 and Rpt-6 can also be phosphorylated to modify the activity of the proteasome. The kinases that perform these phosphorylations are DYRK2 for Rpt-3[128] and calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) for Rpt-6.[129] Alanine mutants of these proteins decreased proteasome activity, which was the same result as the mutant Rpn-6. Inhibition of these kinases would lead to a myriad of effects; therefore, it may be more beneficial to discover small molecule binders that prevent these phosphorylation events of the 19S RP subunits.

Increasing degradation of certain proteasome subunits, which could limit the amount of fully assembled 26S proteasomes, could be accomplished by designing a proteolysis targeting chimera or PROTAC.[130] Certain 19S RP subunits are overexpressed in various cancers, such as Rpn-13 and Rpn-6, and probably have roles beyond that in the proteasome. For example, it has been noted that certain proteasome subunits are known to interact with RNA and actually preventing this interaction could be more cytotoxic than affecting proteasome activity.[131] Controlled degradation of 19S RP subunits overexpressed and not associated with the 26S could be a plausible anti-cancer mechanism. The E3 ligase for Rpn-13 is already known, Ube3C. Since Ube3C has limited tertiary structure that could bind a small molecule, it is currently unknown if this E3 ligase could be used in the PROTAC mechanism of degradation.[132] Another potential PROTAC target could be Rpn-10, which interacts with the E3 ligase Rsp5.[133] However, since Rpn-10 is essential in healthy cells, its therapeutic window may be limited. Rpn-6 is another 19S RP subunit that is overexpressed relative to other proteasome subunits, and after a small molecule binder is discovered to non-proteasome associated Rpn-6, a PROTAC could be tested.

Targeting the chymotrypsin-like active site of the proteasome with small molecule inhibitors provided the foundation to continue pursuing this pathway for new anti-cancer therapeutics. While the β5 inhibitors have thus far been the most promising, with several on the market, there are a number of other 26S subunits, including the 19S RP, that can be targeted. Modulating the activity of the proteasome has already proven to be beneficial in hematological cancers, but there are other diseases where increasing or decreasing overall proteasome activity could be beneficial. For example, it has long been hypothesized that increasing proteasome activity could combat premature aging or neurological diseases. There are several examples of molecules that can stimulate the activity of the proteasome.[134-137] More recently, proteasome inhibitors have been proposed to aid in treating autoimmune diseases.[138,139] Small molecule binders to the 19S RP could also be beneficial to the afore mentioned diseases. With more stream-lined screening techniques such as the thermal shift assay and the development of DNA-encoded libraries, it is expected that discovery of more 19S RP binders will be forth coming.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported through a start-up package from Purdue University School of Pharmacy, the Purdue University Center for Cancer Research NIH grant P30 CA023168, and the American Cancer Society Institutional Research Grant (IRG-14-190-56) to the Purdue University Center for Cancer Research is gratefully acknowledged.

Biography

Darci Trader received a PhD in chemistry from Indiana University with Prof. Erin Carlson in 2013 developing new resins to isolate natural products. She then went on to do a NIH NRSA-supported postdoc at The Scripps Research Institute with Prof. Thomas Kodadek. She started at Purdue University in 2016 as an assistant professor in the Department of Medicinal Chemistry and Molecular Pharmacology. Her lab is focused on developing new probes and methods to monitor or perturb proteasome activity.

References

- [1].Dikic I, Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2017, 86, 193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Lee DH, Goldberg AL, Trends Cell Biol. 1998, 8, 397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Lecker SH, J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2006, 17, 1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Etlinger JD, Goldberg AL, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1977, 74, 54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Goldberg AL, Dice JF, Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1974, 43, 835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Huang X, Luan B, Wu J, Shi Y, Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2016, 23, 778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ben-Nissan G, Sharon M, Biomolecules 2014, 4, 862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Thrower JS, EMBO J. 2000, 19, 94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kisselev AF, Akopian TN, Woo KM, Goldberg AL, J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 3363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Saric T, Graef CI, Goldberg AL, J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 46723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Lee A-H, Iwakoshi NN, Anderson KC, Glimcher LH, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2003, 100, 9946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Manasanch EE, Orlowski RZ, Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 14, 417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Hobler SC, Williams A, Fischer D, Wang JJ, Sun X, Fischer JE, Monaco JJ, Hasselgren P-O, Am. J. Physiol.-Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 1999, 277, R434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Hobler SC, Tiao G, Fischer JE, Monaco J, Hasselgren P-O, Am. J. Physiol.-Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 1998, 274, R30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Tawa NE, Odessey R, Goldberg AL, J. Clin. Invest. 1997, 100, 197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Mizrachy-Schwartz S, Cohen N, Klein S, Kravchenko-Balasha N, Levitzki A, IUBMB Life 2010, 62, 757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Kane RC, Clin. Cancer Res. 2006, 12, 2955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Blackburn C, Gigstad KM, Hales P, Garcia K, Jones M, Bruzzese FJ, Barrett C, Liu JX, Soucy TA, Sappal DS, Bump N, Olhava EJ, Fleming P, Dick LR, Tsu C, Sintchak MD, Blank JL, Biochem. J. 2010, 430, 461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Richardson PG, Weller E, Lonial S, Jakubowiak AJ, Jagannath S, Raje NS, Avigan DE, Xie W, Ghobrial IM, Schlossman RL, Mazumder A, Munshi NC, Vesole DH, Joyce R, Kaufman JL, Doss D, Warren DL, Lunde LE, Kaster S, DeLaney C, Hideshima T, Mitsiades CS, Knight R, Esseltine D-L, Anderson KC, Blood 2010, 116, 679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Argyriou AA, Iconomou G, Kalofonos HP, Blood 2008, 112, 1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Kuhn DJ, Chen Q, Voorhees PM, Strader JS, Shenk KD, Sun CM, Demo SD, Bennett MK, van Leeuwen FWB, Chanan-Khan AA, Orlowski RZ, Blood 2007, 110, 3281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Herndon TM, Deisseroth A, Kaminskas E, Kane RC, Koti KM, Rothmann MD, Habtemariam B, Bullock J, Bray JD, Hawes J, Palmby TR, Jee J, Adams W, Mahayni H, Brown J, Dorantes A, Sridhara R, Farrell AT, Pazdur R, Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 4559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Korde N, Roschewski M, Zingone A, Kwok M, Manasanch EE, Bhutani M, Tageja N, Kazandjian D, Mailankody S, Wu P, Morrison C, Costello R, Zhang Y, Burton D, Mulquin M, Zuchlinski D, Lamping L, Carpenter A, Wall Y, Carter G, Cunningham SC, Gounden V, Sissung TM, Peer C, Maric I, Calvo KR, Braylan R, Yuan C, Stetler-Stevenson M, Arthur DC, Kong KA, Weng L, Faham M, Lindenberg L, Kurdziel K, Choyke P, Steinberg SM, Figg W, Landgren O, JAMA Oncol. 2015, 1, 746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Tanaka K, Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B 2009, 85, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Deverauxf Q, Ustrellf V, Pickart C, Rechsteiner M, 3. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Jørgensen JP, Lauridsen A-M, Kristensen P, Dissing K, Johnsen AH, Hendil KB, Hartmann-Petersen R, J. Mol. Biol. 2006, 360, 1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Qiu X-B, Ouyang S-Y, Li C-J, Miao S, Wang L, Goldberg AL, EMBO J. 2006, 25, 5742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Hamazaki J, Iemura S, Natsume T, Yashiroda H, Tanaka K, Murata S, EMBO J. 2006, 25, 4524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Zhang N, Wang Q, Ehlinger A, Randles L, Lary JW, Kang Y, Haririnia A, Storaska AJ, Cole JL, Fushman D, Walters KJ, Mol. Cell 2009, 35, 280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Sakata E, Bohn S, Mihalache O, Kiss P, Beck F, Nagy I, Nickell S, Tanaka K, Saeki Y, Forster F, Baumeister W, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012, 109, 1479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Finley D, Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2009, 78, 477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Hamazaki J, Sasaki K, Kawahara H, Hisanaga S. -i., Tanaka K, Murata S, Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007, 27, 6629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Al-Shami A, Jhaver KG, Vogel P, Wilkins C, Humphries J, Davis JJ, Xu N, Potter DG, Gerhardt B, Mullinax R, Shirley CR, Anderson SJ, Oravecz T, PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e13654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Song Y, Ray A, Li S, Das DS, Tai YT, Carrasco RD, Chauhan D, Anderson KC, Leukemia 2016, 30, 1877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Yu G-Y, Wang X, Zheng S-S, Gao X-M, Jia Q-A, Zhu W-W, Lu L, Jia H-L, Chen J-H, Dong Q-Z, Lu M, Qin L-X, Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 47, 1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Fejzo MS, Anderson L, Chen H-W, Anghel A, Zhuo J, Anchoori R, Roden R, Slamon DJ, Genes. Chromosomes Cancer 2015, 54, 506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Lu X, Nowicka U, Sridharan V, Liu F, Randles L, Hymel D, Dyba M, Tarasov SG, Tarasova NI, Zhao XZ, Hamazaki J, Murata S, Burke TR Jr., Walters KJ, Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].VanderLinden RT, Hemmis CW, Yao T, Robinson H, Hill CP, J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 9493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Sahtoe DD, van Dijk WJ, El Oualid F, Ekkebus R, Ovaa H, Sixma TK, Mol. Cell 2015, 57, 887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Chen X, Lee B-H, Finley D, Walters KJ, Mol. Cell 2010, 38, 404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Anchoori RK, Karanam B, Peng S, Wang JW, Jiang R, Tanno T, Orlowski RZ, Matsui W, Zhao M, Rudek MA, Hung C, Chen X, Walters KJ, Roden RBS, Cancer Cell 2013, 24, 791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Anchoori RK, Khan SR, Sueblinvong T, Felthauser A, Iizuka Y, Gavioli R, Destro F, Isaksson Vogel R, Peng S, Roden RBS, Bazzaro M, PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e23888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Bazzaro M, Anchoori RK, Mudiam MKR, Issaenko O, Kumar S, Karanam B, Lin Z, Isaksson Vogel R, Gavioli R, Destro F, Ferretti V, Roden RBS, Khan SR, J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Jiang RT, Yemelyanova A, Xing D, Anchoori RK, Hamazaki J, Murata S, Seidman JD, Wang T-L, Roden RBS, J. Ovarian Res. 2017, 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Soong R-S, Anchoori RK, Yang B, Yang A, Tseng S-H, He L, Tsai Y-C, Hung C-F, Hung C-F, Oncotarget 2016, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Anchoori RK, Jiang R, Peng S, Soong R, Algethami A, Rudek MA, Anders N, Hung C-F, Chen X, Lu X, Kayode O, Dyba M, Walters KJ, Roden RBS, ACS Omega 2018, 3, 11917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Trader DJ, Simanski S, Kodadek T, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 6312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Lu X, Liu F, Durham SE, Tarasov SG, Walters KJ, PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0140518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Du J, Strieter ER, Anal. Biochem. 2018, 550, 84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Amerik AY, Hochstrasser M, Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA - Mol. Cell Res. 2004, 1695, 189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Swatek KN, Komander D, Cell Res. 2016, 26, 399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Saeki Y, J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 2017, mvw091. [Google Scholar]

- [53].Lee MJ, Lee B-H, Hanna J, King RW, Finley D, Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2011, 10, R110.003871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Hanna J, Hathaway NA, Tone Y, Crosas B, Elsasser S, Kirkpatrick DS, Leggett DS, Gygi SP, King RW, Finley D, Cell 2006, 127, 99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Reyes-Turcu FE, Ventii KH, Wilkinson KD, Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2009, 78, 363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Xu P, Duong DM, Seyfried NT, Cheng D, Xie Y, Robert J, Rush J, Hochstrasser M, Finley D, Peng J, Cell 2009, 137, 133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Kim W, Bennett EJ, Huttlin EL, Guo A, Li J, Possemato A, Sowa ME, Rad R, Rush J, Comb MJ, Harper JW, Gygi SP, Mol. Cell 2011, 44, 325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Kim HT, Goldberg AL, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2018, 115, E11642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Shi Y, Chen X, Elsasser S, Stocks BB, Tian G, Lee B-H, Shi Y, Zhang N, de Poot SAH, Tuebing F, Sun S, Vannoy J, Tarasov SG, Engen JR, Finley D, Walters KJ, Science 2016, 351, aad9421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Hu M, Li P, Song L, Jeffrey PD, Chenova TA, Wilkinson KD, Cohen RE, Shi Y, EMBO J. 2005, 24, 3747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Hershko A, Rose IA, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1987, 84, 1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Lee B-H, Lee MJ, Park S, Oh D-C, Elsasser S, Chen P-C, Gartner C, Dimova N, Hanna J, Gygi SP, Wilson SM, King RW, Finley D, Nature 2010, 467, 179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Kisselev AF, van der Linden WA, Overkleeft HS, Chem. Biol. 2012, 19, 99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Kiprowska MJ, Stepanova A, Todaro DR, Galkin A, Haas A, Wilson SM, Figueiredo-Pereira ME, Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA - Mol. Basis Dis. 2017, 1863, 1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Boselli M, Lee B-H, Robert J, Prado MA, Min S-W, Cheng C, Silva MC, Seong C, Elsasser S, Hatle KM, Gahman TC, Gygi SP, Haggarty SJ, Gan L, King RW, Finley D, J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 19209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Wang Y, Jiang Y, Ding S, Li J, Song N, Ren Y, Hong D, Wu C, Li B, Wang F, He W, Wang J, Mei Z, Cell Res. 2018, 28, 1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].D’Arcy P, Brnjic S, Olofsson MH, Fryknäs M, Lindsten K, De Cesare M, Perego P, Sadeghi B, Hassan M, Larsson R, Linder S, Nat. Med. 2011, 17, 1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Tian Z, D’Arcy P, Wang X, Ray A, Tai Y-T, Hu Y, Carrasco RD, Richardson P, Linder S, Chauhan D, Anderson KC, Blood 2014, 123, 706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Wang X, Mazurkiewicz M, Hillert E-K, Olofsson MH, Pierrou S, Hillertz P, Gullbo J, Selvaraju K, Paulus A, Akhtar S, Bossler F, Khan AC, Linder S, D’Arcy P, Sci. Rep. 2016, 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Zhou B, Zuo Y, Li B, Wang H, Liu H, Wang X, Qiu X, Hu Y, Wen S, Du J, Bu X, Mol. Cancer Ther. 2013, 12, 1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Qiu X, Du Y, Lou B, Zuo Y, Shao W, Huo Y, Huang J, Yu Y, Zhou B, Du J, Fu H, Bu X, J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 8260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Song Y, Li S, Ray A, Das DS, Qi J, Samur MK, Tai Y-T, Munshi N, Carrasco RD, Chauhan D, Anderson KC, Oncogene 2017, 36, 5631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Verma R, Science 2002, 298, 611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Worden EJ, Padovani C, Martin A, Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2014, 21, 220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Worden EJ, Dong KC, Martin A, Mol. Cell 2017, 67, 799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Pathare GR, Nagy I, Sledz P, Anderson DJ, Zhou H-J, Pardon E, Steyaert J, Forster F, Bracher A, Baumeister W, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2014, 111, 2984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Li J, Yakushi T, Parlati F, Mackinnon AL, Perez C, Ma Y, Carter KP, Colayco S, Magnuson G, Brown B, Nguyen K, Vasile S, Suyama E, Smith LH, Sergienko E, Pinkerton AB, Chung TDY, Palmer AE, Pass I, Hess S, Cohen SM, Deshaies RJ, Nat. Chem. Biol. 2017, 13, 486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Kumar V, Naumann M, Stein M, Front. Chem. 2018, 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Borg-Neczak K, Tjälve H, Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1994, 74, 185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Lauinger L, Li J, Shostak A, Cemel IA, Ha N, Zhang Y, Merkl PE, Obermeyer S, Stankovic-Valentin N, Schafmeier T, Wever WJ, Bowers AA, Carter KP, Palmer AE, Tschochner H, Melchior F, Deshaies RJ, Brunner M, Diernfellner A, Nat. Chem. Biol. 2017, 13, 709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Finley D, Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2009, 78, 477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Bar-Nun S, Glickman MH, Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA - Mol. Cell Res. 2012, 1823, 67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Beyer A, Protein Sci. 2008, 6, 2043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Stadtmueller BM, Ferrell K, Whitby FG, Heroux A, Robinson H, Myszka DG, Hill CP, J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Smith DM, Benaroudj N, Goldberg A, J. Struct. Biol. 2006, 156, 72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Confalonieri F, Duguet M, BioEssays 1995, 17, 639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Chen S, Wu J, Lu Y, Ma Y-B, Lee B-H, Yu Z, Ouyang Q, Finley DJ, Kirschner MW, Mao Y, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2016, 113, 12991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Dong Y, Zhang S, Wu Z, Li X, Wang WL, Zhu Y, Stoilova-McPhie S, Lu Y, Finley D, Mao Y, Nature 2019, 565, 49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Lim H-S, Archer CT, Kodadek T, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 7750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Jentsch S, Rumpf S, Trends Biochem. Sci. 2007, 32, 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Zhang X, Shaw A, Bates PA, Newman RH, Gowen B, Orlova E, Gorman MA, Kondo H, Dokurno P, Lally J, Leonard G, Meyer H, van Heel M, Freemont PS, Mol. Cell 2000, 6, 1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Meyer HH, EMBO J. 2002, 21, 5645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Ye Y, Meyer HH, Rapoport TA, Nature 2001, 414, 652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Jarosch E, Taxis C, Volkwein C, Bordallo J, Finley D, Wolf DH, Sommer T, Nat. Cell Biol. 2002, 4, 134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Kloppsteck P, Ewens CA, Förster A, Zhang X, Freemont PS, Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA - Mol. Cell Res. 2012, 1823, 125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Meyer H, Weihl CC, Cell Sci J. 2014, 127, 3877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Anderson DJ, Le Moigne R, Djakovic S, Kumar B, Rice J, Wong S, Wang J, Yao B, Valle E, Kiss von Soly S, Madriaga A, Soriano F, Menon M-K, Wu ZY, Kampmann M, Chen Y, Weissman JS, Aftab BT, Yakes FM, Shawver L, Zhou H-J, Wustrow D, Rolfe M, Cancer Cell 2015, 28, 653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Davies JM, Brunger AT, Weis WI, Structure 2008, 16, 715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Banerjee S, Bartesaghi A, Merk A, Rao P, Bulfer SL, Yan Y, Green N, Mroczkowski B, Neitz RJ, Wipf P, Falconieri V, Deshaies RJ, Milne JLS, Huryn D, Arkin M, Subramaniam S, 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Song C, Wang Q, Li C-CH, J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 3648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Fiebiger E, Hirsch C, Vyas JM, Gordon E, Ploegh HL, Tortorella D, Mol. Biol. Cell 2004, 15, 1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Wang Q, Li L, Ye Y, J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 7445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Wang Q, Shinkre BA, Lee J, Weniger MA, Liu Y, Chen W, Wiestner A, Trenkle WC, Ye Y, PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e15479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Chou T-F, Brown SJ, Minond D, Nordin BE, Li K, Jones AC, Chase P, Porubsky PR, Stoltz BM, Schoenen FJ, Patricelli MP, Hodder P, Rosen H, Deshaies RJ, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2011, 108, 4834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Chou T-F, Li K, Frankowski KJ, Schoenen FJ, Deshaies RJ, ChemMedChem 2013, 8, 297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Le Moigne R, Aftab BT, Djakovic S, Dhimolea E, Valle E, Murnane M, King EM, Soriano F, Menon M-K, Wu ZY, Wong ST, Lee GJ, Yao B, Wiita AP, Lam C, Rice J, Wang J, Chesi M, Bergsagel PL, Kraus M, Driessen C, Kiss Von Soly S, Yakes FM, Wustrow D, Shawver L, Zhou H-J, Martin TG, Wolf JL, Mitsiades CS, Anderson DJ, Rolfe M, Mol. Cancer Ther. 2017, 16, 2375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Magnaghi P, D’Alessio R, Valsasina B, Avanzi N, Rizzi S, Asa D, Gasparri F, Cozzi L, Cucchi U, Orrenius C, Polucci P, Ballinari D, Perrera C, Leone A, Cervi G, Casale E, Xiao Y, Wong C, Anderson DJ, Galvani A, Donati D, O’Brien T, Jackson PK, Isacchi A, Nat. Chem. Biol. 2013, 9, 548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Tao S, Tillotson J, Wijeratne EMK, Xu Y, Kang M, Wu T, Lau EC, Mesa C, Mason DJ, Brown RV, La Clair JJ, Gunatilaka AAL, Zhang DD, Chapman E, ACS Chem. Biol. 2015, 10, 1916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Chimenti MS, Bulfer SL, Neitz RJ, Renslo AR, Jacobson MP, James TL, Arkin MR, Kelly MJS, J. Biomol. Screen. 2015, 20, 788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Kriegenburg F, Ellgaard L, Hartmann-Petersen R, FEBS J 2012, 279, 532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Nanaware PP, Ramteke MP, Somavarapu AK, Venkatraman P, Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinforma. 2014, 82, 1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Chattopadhyay A, O’Connor CJ, Zhang F, Galvagnion C, Galloway WRJD, Tan YS, Stokes JE, Rahman T, Verma C, Spring DR, Itzhaki LS, Sci. Rep. 2016, 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Krzywda S, Brzozowski AM, Higashitsuji H, Fujita J, Welchman R, Dawson S, Mayer RJ, Wilkinson AJ, J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Manjasetty BA, Quedenau C, Sievert V, Büssow K, Niesen F, Delbrück H, Heinemann U, Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinforma. 2004, 55, 214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Yuan C, Li J, Mahajan A, Poi MJ, Byeon I-JL, Tsai M-D, Biochemistry 2004, 43, 12152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].Dawson S, Apcher S, Mee M, Higashitsuji H, Baker R, Uhle S, Dubiel W, Fujita J, Mayer RJ, J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 10893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [117].Dawson S, Higashitsuji H, Wilkinson AJ, Fujita J, Mayer RJ, Trends Cell Biol. 2006, 16, 229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [118].Fu X-Y, World J Gastroenterol. 2002, 8, 638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [119].Man J-H, Liang B, Gu Y-X, Zhou T, Li A-L, Li T, Jin B-F, Bai B, Zhang H-Y, Zhang W-N, Li W-H, Gong W-L, Li H-Y, Zhang X-M, J. Clin. Invest. 2010, 120, 2829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [120].Zhen C, Chen L, Zhao Q, Liang B, Gu Y-X, Bai Z, Wang K, Xu X, Han Q, Fang D, Wang S, Zhou T, Xia Q, Gong W, Wang N, Li H-Y, Jin B-F, Man J, Oncogene 2013, 32, 3452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [121].Wang C, Cheng L, Invest. New Drugs 2017, 35, 655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [122].Thakur PK, Hassan MI, Int. J. Comput. Biol. Drug Des. 2011, 4, 373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [123].Song X, Wang J, Zheng T, Song R, Liang Y, Bhatta N, Yin D, Pan S, Liu J, Jiang H, Liu L, Mol. Cancer 2013, 12, 114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [124].D’Souza AM, Jiang Y, Cast A, Valanejad L, Wright M, Lewis K, Kumbaji M, Shah S, Smithrud D, Karns R, Shin S, Timchenko N, Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 6, 239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [125].Fonseca R, Abouzaid S, Bonafede M, Cai Q, Parikh K, Cosler L, Richardson P, Leukemia 2017, 31, 1915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [126].Pathare GR, Nagy I, Bohn S, Unverdorben P, Hubert A, Korner R, Nickell S, Lasker K, Sali A, Tamura T, Nishioka T, Forster F, Baumeister W, Bracher A, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012, 109, 149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [127].Mayor T, Sharon M, Glickman MH, Am. J. Physiol.-Cell Physiol 2016, 311, C793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [128].Guo X, Wang X, Wang Z, Banerjee S, Yang J, Huang L, Dixon JE, Nat. Cell Biol. 2016, 18, 202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [129].Bingol B, Wang C-F, Arnott D, Cheng D, Peng J, Sheng M, Cell 2010, 140, 567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [130].Sakamoto KM, Kim KB, Kumagai A, Mercurio F, Crews CM, Deshaies RJ, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001, 98, 8554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [131].Huang R, Han M, Meng L, Chen X, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2018, 115, E3879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [132].Fajner V, Maspero E, Polo S, FEBS Lett. 2017, 591, 2636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [133].Isasa M, Katz EJ, Kim W, Yugo V, González S, Kirkpatrick DS, Thomson TM, Finley D, Gygi SP, Crosas B, Mol. Cell 2010, 38, 733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [134].Coleman R, Trader D, ACS Comb Sci 2018, 20, 269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [135].Coleman R, Trader D, ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci 2018, 1, 140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [136].Jones CL, Njomen E, Sjögren B, Dexheimer TS, Tepe JJ, ACS Chem. Biol. 2017, 12, 2240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [137].Witkowska J, Giżyńska M, Grudnik P, Golik P, Karpowicz P, Giełdoń A, Dubin G, Jankowska E, Sci. Rep. 2017, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [138].Fierabracci A, Curr. Drug Targets 2012, 13, 1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [139].Verbrugge S, Scheper RJ, Lems WF, de Gruijl TD, Jansen G, Arthritis Res. Ther. 2015, 17, 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]