Abstract

The diverse requirements of hydrogels for tissue engineering motivate the development of cross-linking reactions to fabricate hydrogel networks with specific features, particularly those amenable to the activity of biological materials (e.g., cells, proteins) that do not require exposure to UV light. We describe gelation kinetics for a library of thiolated poly(ethylene glycol) sulfhydryl hydrogels undergoing enzymatic cross-linking via horseradish peroxidase, a catalyst-driven reaction activated by hydrogen peroxide. We report the use of small-amplitude oscillatory shear (SAOS) to quantify gelation kinetics as a function of reaction conditions (hydrogen peroxide and polymer concentrations). We employ a novel approach to monitor the change of viscoelastic properties of hydrogels over the course of gelation (Δtgel) via the time derivative of the storage modulus (dG′/dt). This approach, fundamentally distinct from traditional methods for defining a gel point, quantifies the time interval over which gelation events occur. We report that gelation depends on peroxide and polymer concentrations as well as system temperature, where the effects of hydrogen peroxide tend to saturate over a critical concentration. Further, this cross-linking reaction can be reversed using L-cysteine for rapid cell isolation, and the rate of hydrogel dissolution can be monitored using SAOS.

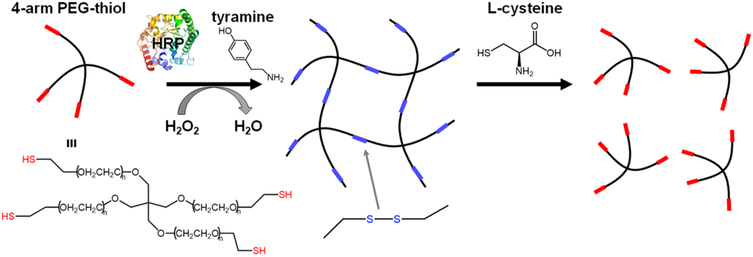

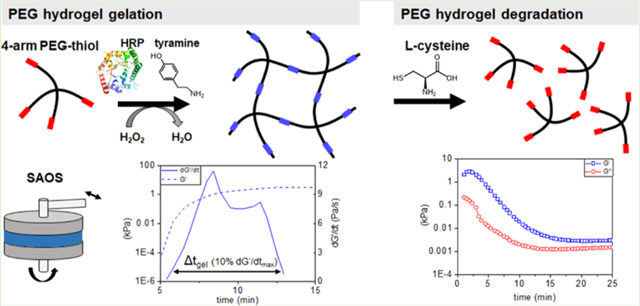

Graphical Abstract

1. INTRODUCTION

Hydrogels are ubiquitous in the field of tissue engineering. As three-dimensional networks of hydrophilic polymers that absorb and retain water, they can present a range of structural and compositional properties that mimic features of the extracellular matrix, such as high water content, viscoelasticity, and metabolite biotransport.1–5 The physical properties of these networks (e.g., elasticity and swelling) can be strongly influenced by the manner of polymer cross-linking, typically achieved through physical interactions between6 or chemical bonding of the polymeric macromers.7 In an effort to improve structural stability, chemical cross-links offer advantages in terms of permanence of the hydrogel network.8 In particular, light-catalyzed reactions not only provide the ability to rapidly generate hydrogel networks but also provide a means to locally define9–11 or alter (stiffen, soften)12–14 cross-linking density, as well as selectively incorporate biomolecules of interest such as growth factors.15–17 While widely applicable, potential drawbacks such as poor light penetration leading to significant differences in the final network architecture and thickness for constructs of different sizes (millimeter-scale vs micron-scale),18 restriction to the use of potentially damaging photoinitiators, and the potential for reduced cell activity due to light intensity motivate the use of other cross-linking methods.19

Enzymatic cross-linking provides the ability to generate strong covalent bonds between polymer chains under mild conditions that are less damaging to encapsulated drugs, proteins, and living cells. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP), an oxidation-catalyzing enzyme with high stability and activity, can catalyze gelation via radical coupling of phenol and aniline derivatives in the presence of exogenous hydrogen peroxide (H2O2).20 Such reactions offer the ability to tune the gelation rate and final gel properties (e.g., stiffness). Notably, Groll et al. reported HRP-catalyzed redox-sensitive disulfide crosslinked hydrogels in basic pH conditions (pH 8.5) and without H2O2 but with slow (>110 min) reaction times.21 Moriyama et al. reported HRP-catalyzed gelation (~30 min) of thiomers using phenolic compounds that accelerate disulfide cross-linking by promoting thiol oxidation. Theoretically, gelation can be further accelerated via exogenous H2O2,22 though this approach carries the risk of reduced cell viability.23 Regardless, the resultant disulfide cross-links offer the potential to be cleaved with the use of mild reductants such as l-cysteine (5 mM),24,25 suggesting that these hydrogels can be degraded under conditions minimally harmful to encapsulated cells. This class of reaction introduces variability in cross-linking rate, the final network architecture, and the kinetics of degradation. Here, we report approaches to develop a comprehensive strategy to monitor these dynamic processes. While the gelation kinetics of HRP-catalyzed disulfide cross-linked hydrogels have not been rigorously established,21,24 oscillatory shear rheology offers a framework to monitor gelation kinetics via shifts in viscoelastic properties.26 Continuously monitoring the stress response to small-amplitude oscillatory shear (SAOS) via rheometry provides an objective means to monitor elastic and viscous properties via the storage G′(ω, t) and loss moduli G″(ω, t). Traditionally, efforts to monitor gelation report a characteristic timescale, the critical gel point. Classical work by Chambon and Winter27 identified the gel point as the point where the storage and loss moduli follow the same power-law behaviors with respect to the frequency: G′(ω) ∝ G″(ω) ∝ ωn. Nonetheless, for rapid reactions, such as the HRP-catalyzed disulfide cross-linked hydrogel system described here, it is practically difficult to measure G′ and G″ in a short enough interval to claim quasi-stable material properties27 and thus hard to apply the Winter–Chambon rule. To quantify gelation rate of these systems with rapid reactions, efforts often report the time at which the dynamic moduli cross (G′ = G″) as a measure of gelation rate.28–31 It is important to mention that this timescale can strongly depend on the imposed frequency32 and is fundamentally different from the gel point determined from the Winter–Chambon rule in which the power-law behavior is observed. The crossover state simply splits the gelation into two stages, predominantly viscous (G′ < G″) and predominantly elastic (G′ > G″), and is one approximate measure of gelation time. However, for many tissue engineering applications that involve encapsulation of cells within a hydrogel network, it can be important to employ metrics to describe dynamic cross-linking reactions to balance considerations regarding cross-linking kinetics, final network architecture, and resultant cell activity.

We report the use of SAOS analytical methods to describe the kinetics of gelation and degradation for a poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) hydrogel generated via HRP-catalyzed disulfide cross-linking of four-arm thiolated PEG macromers (Scheme 1). PEG is commonly employed as a hydrogel backbone because of the diverse functional groups that can be added to its backbone to facilitate cross-linking, degradation, and biomolecular functionalization, as well as its biocompatibility.2,33–36 We describe the influence of orthogonal changes in PEG weight percent (wt %) and exogenous H2O2 for a library of hydrogels on the kinetics of gelation and the equilibrium viscoelastic properties of the network using both conventional and newly developed metrics of gelation. Notably, we describe a novel derivative-based metric to quantify the duration of the gelation process. This metric differs from more conventional identification of a gel point by quantifying the duration over which the viscoelastic properties of the material are changing, affording a more comprehensive probing of the transient property changes in the material. We also demonstrate limited cell viability in the hydrogels during gelation and following degradation with l-cysteine and describe an adapted SAOS rheology method to monitor the kinetics of network degradation.

Scheme 1. Formation of a Poly(ethylene glycol) Sulfhydryl (PEG-SH) Polymer Mesh Network via HRP-Catalyzed Cross-Linking and Subsequent Degradation of the Hydrogel via a Reducing Agent, L-Cysteinea.

aH2O2 activates HRP by changing the oxidation state of its central iron heme group. Activated HRP oxidizes tyramine, creating phenol radicals that readily oxidize thiol groups. Thiol radicals are subsequently transformed into disulfides after reacting with molecular oxygen, forming a cross-linked polymer network. This polymer network can be degraded with a reductant, in this case, l-cysteine.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Preparation of PEG-SH Hydrogels and Analysis of Equilibrium Water Content (EWC).

A library of hydrogel precursor suspensions was created from mixtures of a polymer solution generated from four-arm PEG-thiol (PEG-SH; 20 000 MW, JenKem Technology, Plano, TX) dissolved in Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) (pH 7.3, Corning cellgro, Corning, NY) at a series of polymer weight percentages (wt %) mixed with a reaction solution generated from H2O2 (30% solution, Macron, Radnor, PA), tyramine (99%, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and HRP (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) (Supporting Information (SI), Table S1). The polymer and reaction solutions were then mixed to generate the polymerization reaction, with all measures of cross-linking reaction rate calculated relative to the time of mixing. Hydrogel samples were named according to their composition of PEG-SH and H2O2 (e.g., P5H5 is 5 wt % PEG-SH and 5 mM H2O2).

PEG-SH hydrogels were made into disks by pipetting 250 μL of the reacting prepolymer solution into cylindrical wells (8 mm dia., 5 mm thick) within a Teflon mold. Gelation proceeded at ambient room temperature for 1 h to allow all samples to polymerize and to allow a consistent period of time past the slowest sample crossover state (tcross). Following gelation, the equilibrium water content (EWC) for each hydrogel sample was calculated by submerging specimens in 5 mL of DPBS for 12 h to determine swollen mass after hydrating (mh) followed by lyophilization to measure mass after drying (mD). EWC was calculated as (mh − md)/mh × 100%.37

2.2. Rheological Analysis of Gelation.

For each sample, a polymer solution at the desired wt % and a reaction solution at the desired concentrations of H2O2, tyramine, and HRP (Supporting Information, Table S1) were mixed and immediately loaded onto the bottom plate of a DHR-3 rheometer (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE) with a Peltier system controlling the temperature at 25 ± 0.1 °C. A parallel plate fixture (20 mm diameter) was used with a measuring gap of 1000 μm. Oscillatory shear was continuously applied at 0.8 rad/s in the rheological linear regime to monitor gelation at a sampling interval of 30 s. Mixing and loading times were added to the start of the time sweep measurements to account for the short period of reaction prior to starting the measurement. For measurements to test the temperature dependence of gelation, a procedure identical to the above was used with the temperatures set to 10 and 0 °C. For measuring unperturbed gels, samples were loaded onto the bottom plate of the rheometer and allowed to fully gel for 1 h before linear regime frequency sweeps were applied across a range from 0.1 to 100 rad/s.

2.3. Cell Viability Studies.

Analysis of cell–hydrogel interactions was performed using a 5 wt % four-arm PEG-SH hydrogel formed with 10 mM H2O2 (sample P5H10) along with the addition of a 0.1 wt % thiolated gelatin (gel-SH, 0.0598 μmol thiol per mg) to enhance cellular adhesion.38 Previous studies have shown that the addition of such a small wt % of thiolated gelatin did not significantly alter the final hydrogel storage modulus.38 These findings were substantiated through the rheological analysis of PEG-SH hydrogels with the addition of 0.1 and 1 wt % thiolated gelatins (Figure S4).

Thiolated gelatin (gel-SH) was produced from 5 g of gelatin (Sigma-Aldrich, Type A, 300-Bloom from porcine skin) dissolved in 50 mL of 1× PBS buffer (Lonza, Switzerland, pH 7.4) at 40 °C using a hot plate and a magnetic stir bar. Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA, 15 mg, 51 μmol) was added and the mixture was stirred for 5 min. Traut’s reagent (240 mg, Thermo Fisher Scientific, 1.175 mmol) was immediately added and stirred for 1 h at 40 °C. The reaction mixture was diluted with 50 mL of deionized (DI) water, poured into regenerated cellulose-based dialysis membranes (molecular weight cutoff 14 000), and dialyzed in DI water at 50 °C for 2 days, followed by lyophilization, affording the product as a white solid. The presence of thiol groups was assessed using Ellman’s reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific).39

Human bone-marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs; Lonza) were cultured in 75 cm2 flasks (Thermo Fisher Scientific Nunc EasYFlask) in growth medium comprising low-glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium with a 10 vol % MSC fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Ireland) and 1 vol % of 100× antibiotic–antimitotic (Gibco) and incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Cells were fed every 3 days, lifted at 80% confluency using 1× 0.05% trypsin–EDTA (Gibco), and used at passage 6.

hMSCs were suspended in polymer solution (5 wt % PEG-SH, 0.1 wt % gel-SH) and mixed with a stock reaction solution (10 mM H2O2, 5 units/mL HRP, 5 mM tyramine) inside a Teflon mold (8 mm dia., 5 mm thick). The solution was left to polymerize for 30 min in ambient conditions. Hydrogel specimens were subsequently placed in individual wells of 24-well plates in 1 mL of growth medium and maintained in a tissue culture incubator at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 48h. Cell viability was then measured using a live/dead cytotoxicity kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Briefly, each hMSC-seeded gel was incubated in 500 μL of staining mixture comprising 0.5 μL/mL of calcein and 2 μL/mL of ethidium homodimer in PBS (Lonza). For the degradation of gels, each hMSC-seeded gel was incubated on an orbital shaker in 1 mL of 50, 10, or 5 mM of l-cysteine (97%, Sigma-Aldrich) for 10, 20, and 25 min, respectively, which was the time it took for the solid gels to fully dissolve into solution. The gels were placed in polystyrene tissue-culture-treated plates (Corning) to allow for cell adhesion following release from the degrading gels. Immediately following gel degradation, 500 μL of staining mixture was added directly to the dissolved gel solution. Samples were viewed using a DMi8 inverted microscope (Leica, Germany), with post-imaging analysis, and live/dead cell counting was performed using Fiji (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).40

2.4. Rheological Analysis of PEG-SH Hydrogel Degradation.

The kinetics of hydrogel degradation were monitored using PEG-SH hydrogels (sample P5H10; 16 mm dia., 1.2 mm thick) made from 250 μL of prepolymer solution to conform to the dimensions of the rheometer plates. Hydrogels were made within a three-dimensional printed polylactic acid mold (MakerBot Replicator 2X, Brooklyn, NY). Samples were subsequently left at ambient room temperature in a desiccator for 12 h to allow the hydrogels to fully dry. Once dry, gels were removed from the mold and submerged in 5 mL of 10 mM l-cysteine for either 1 or 2 min. Direct exposure for longer than 5 min resulted in a partially degraded gel that could no longer be manipulated. Following swelling in l-cysteine, samples were immediately transferred to the rheometer. An identical oscillatory shear protocol used to monitor gelation was then employed to monitor the change of viscoelastic properties during the course of degradation at 25 °C. The hydrogel desiccation followed by swelling assay was used to more precisely measure the kinetics of degradation from a known starting time.

2.5. Statistics.

At least n = 3 samples were examined for time-dependent SAOS analysis for gelation and degradation, n = 3 samples for the EWC studies, and n = 6 samples for the live/dead cell viability assays. All error bars reported are ±standard deviation unless otherwise noted.

3. RESULTS

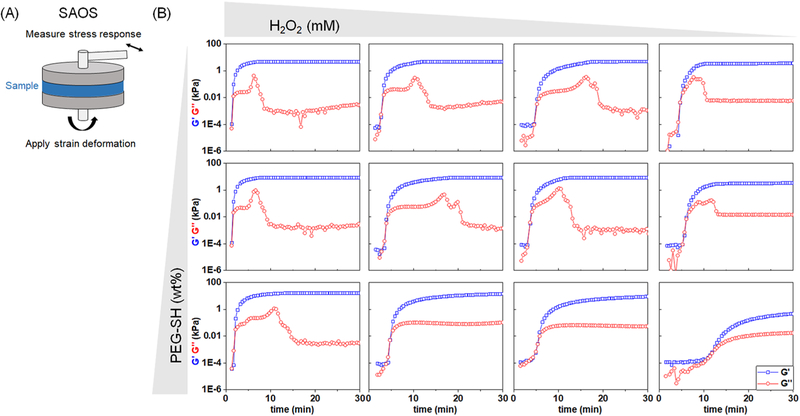

3.1. SAOS Reveals Time-Dependent Changes in Storage and Loss Modulus during Gelation.

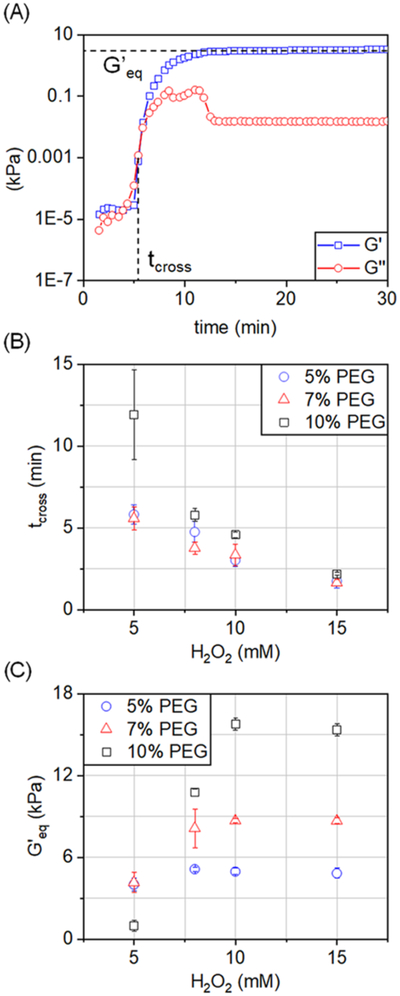

SAOS was used to monitor the gelation of PEG-SH hydrogels as a function of H2O2 (mM) and four-arm PEG-thiol (wt %) (Figure 1A). While quantitatively different, all hydrogel variants displayed qualitatively similar behaviors, with trends of increasing storage modulus (G′) that reach a plateau within 1 h of the start of gelation, time-dependent changes in loss modulus (G″), and a characteristic crossover state where G′ = G″ (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

(A) Small-amplitude oscillatory shear (SAOS) at 0.8 rad/s and 2% strain was used to determine the viscoelastic properties of cross-linking PEG-SH hydrogels, specifically the storage modulus (G′) and loss modulus (G″) of the material as a function of time. (B) Representative plots of G′ and G″ as a function of time for hydrogels varying in H2O2 (5, 8, 10, 15 mM) and PEG-SH (5, 7, 10 wt %) with tyramine (5 mM) and HRP (5 units/mL) held constant.

3.2. Gelation Time and Equilibrium G′ Vary with Hydrogel Formulation and Temperature.

Hydrogel gelation and final network properties were defined via tcross, set at the intersection between the storage and loss moduli (G′ = G″), and via an equilibrium storage modulus (G′eq) set at 1 h after the initiation of gelation, at which point all samples had a plateau in G′ (Figure 2A). Both H2O2 concentration and polymer wt % affected tcross of the cross-linking gel (Figure 2B). Gelation was generally more rapid among samples with a lower polymer wt % and higher concentration of H2O2. However, the effect of polymer wt % on tcross diminished with an increasing amount of available H2O2, reaching a point of excess H2O2 at 15 mM, where all samples had identical tcross regardless of polymer wt %. This suggests that H2O2 is a major effector of gelation rate and that the rate of activation of the enzyme can rapidly increase the rate of cross-linking. Furthermore, tcross increased as the sampling temperature was lowered, with no effect in the plateau value of G′ (Figure S5A). Both H2O2 concentration and polymer wt % affected the final network properties as reflected in G′eq (Figure 2C). Here, G′eq was greater for hydrogels with a higher polymer wt % and increasing H2O2 concentration, eventually reaching a plateau value at the highest concentration (15 mM) of H2O2.

Figure 2.

(A) For each hydrogel sample, the crossover state (tcross) was determined as the point where G′ and G″ intersect (G′ = G″) at a measurement frequency of 0.8 rad/s (2% strain), and the equilibrium storage modulus (G′eq) was obtained from the plateau value of G′ at 60 min postgelation. (B) tcross and (C) G′eq for each of the tested hydrogel samples (n = 3).

Measurements of hydrogel swelling capacity revealed that EWC decreased with increasing polymer wt %, which suggests greater cross-linking and denser polymer networks (Figure S1). Similarly, EWC decreased at higher concentrations of H2O2, eventually reaching a plateau at the highest (15 mM) H2O2 concentration, like the trend seen for G′eq.

To confirm that the serial measurement of hydrogel properties during gelation did not significantly influence the final network properties, hydrogel specimens were alternatively allowed to fully gel within the rheometer for 1 h before rheological testing via a frequency sweep to determine an unperturbed G′eq. Values of G′eq found by time sweep measurements were normalized to unperturbed G′eq (Figure S2) and revealed little deviation in the value of G′eq due to continuous monitoring. However, samples that took longer to gel had greater deviations from the unperturbed G′eq when measured (further from a normalized value of 1).

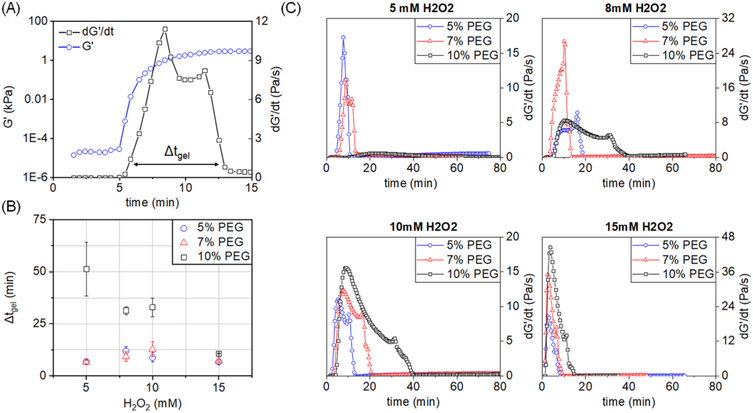

3.3. Gelation Interval Depicts the Timescale of the Gel Cross-linking Process.

We subsequently calculated the time derivative of G′ (dG′/dt) during gelation as a metric of the overall duration of the gelation process from start to finish (Figure 3A). In this manner, the dG′/dt curve can identify the time interval over which the majority of changes in the storage modulus of the material occurs. Representative plots of dG′/dt as a function of time and hydrogel formulation show clear differences in the duration of gelation (Figure 3C). A duration of gelation (Δtgel) was calculated as the full width (time) at 10% of the maximum value of the peak of the derivative of G′ (dG′/dt). Full width at 10% of the maximum value was used to include only the span of time in which large changes in viscoelastic properties occur, particularly to omit negligible or small changes in the rate of change of the storage modulus at the beginning and end of the material gelation. At values smaller than 10%, Δtgel would grow to encompass time at the beginning of gelation prior to the material rapidly gelling and time after the material has significantly stabilized and is no longer actively changing, which is not the overall target of this metric, to give a more accurate representation of the timescale over which the material is dynamically evolving. Values of Δtgel follow a similar trend as observed for the crossover state (G′ = G″; Figure 3B). Notably, Δtgel was smaller among samples with a lower wt % of polymer and a higher concentration of H2O2, eventually reaching a point of excess H2O2 at 15 mM where all samples had identical Δtgel regardless of polymer wt % (Figure 3B). Calculation of dG′/dt also reveals clear differences in the shape and distinguishable number of peaks that comprise the dG′/dt curve for different hydrogel formulations (Figure 3C). This procedure is reminiscent of the time-resolved rheometry approach of Mours and Winter,41 in which a mutation number associated with a particular physical property is defined by the reciprocal of the normalized temporal derivative. Our approach of determining Δtgel is therefore equivalent to a measure of the time over which the mutation number is nonzero, which represents the time over which the material response is mutating, rather than the rate at which it mutates.

Figure 3.

(A) Schematic of approach for calculating a gelation interval (Δtgel) as the full width at 10% of the maximum value of the derivative of G′ (dG′/dt). G′ is shown on a logarithmic scale. SAOS: 0.8 rad/s, 2% strain. (B) Resultant Δtgel values determined for all hydrogel groups (n = 3). (C) Representative plots of dG′/dt for each of the tested hydrogel groups.

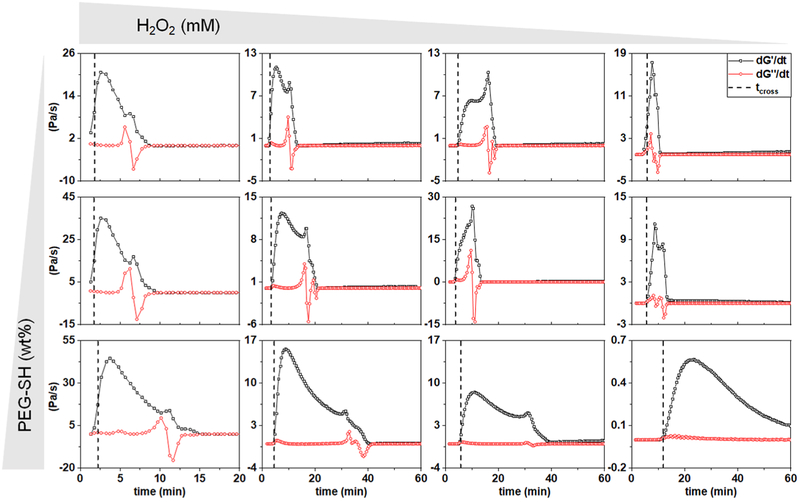

3.4. Rapid Changes in Hydrogel Viscoelastic Properties Occur Prior to Reaching Equilibrium.

To quantify changes of G″ during Δtgel, we plotted dG″/dt as a function of time (Figure 4). We see an identical event occurring in all hydrogel samples immediately before the end of the gelation interval (marked by dG′/dt reaching a plateau value): a strong positive peak in dG″/dt, indicating an increase in the rate of energy dissipation, followed immediately by a larger negative peak in dG″/dt, indicating a sudden and rapid decrease in the rate of energy dissipation. Following these rapid changes in material properties, both dG″/dt and dG′/dt reach zero, indicating that an equilibrium state has been reached, and viscoelastic properties are no longer changing.

Figure 4.

Representative plots of dG′/dt and dG″/dt as a function of time for each of the tested hydrogel conditions, where tcross is included (dotted line) as a point of comparison. SAOS: 0.8 rad/s, 2% strain.

3.5. Portion of hMSCs Remains Viable in PEG-SH Hydrogels Following Encapsulation and Gel Degradation.

We subsequently examined the viability of hMSCs, both after encapsulation within HRP cross-linked PEG-SH hydro-gels (sample P5H10) and following hydrogel degradation in l-cysteine. After encapsulation and a 48 h culture in hydrogels, the percentage of live hMSCs was significantly greater than that of dead hMSCs (Table 1 and Figure S7). Following exposure to 5, 10, or 50 mM of l-cysteine, during which hydrogels dissolved within 25 min to the extent where cells could be isolated via pipetting, a limited percentage of isolated cells remained viable immediately following degradation and release from gels (Table 1 and Figure S7).

Table 1.

Percent of Live hMSCs Encapsulated in PEG-SH Hydrogels (Sample P5H10) after 48 h Culture Immediately Followed by Hydrogel Degradation in 50, 10, and 5 mM of l-Cysteine (n = 6)

| sample | % live cells |

|---|---|

| 48 h culture | 73.4 ± 4.4 |

| 5 mM degradation | 30.8 ± 6.9 |

| 10 mM degradation | 30.7 ± 4.6 |

| 50 mM degradation | 28.8 ± 13.4 |

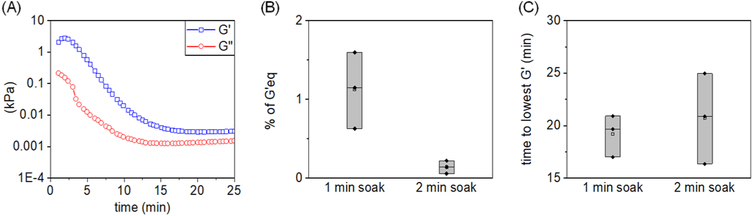

3.6. SAOS Reveals Time-Dependent Changes in Storage and Loss Modulus during Degradation.

SAOS was subsequently employed to measure changes in the dynamic moduli (G′, G″) over time as indicators of hydrogel degradation following direct exposure to l-cysteine (Figure 5A). Hydrogels subjected to 1 or 2 min exposure to l-cysteine reached a value of G′ lower than 2% of its fully gelled value (G′eq) within 20 min (Figure 5B,C), suggesting rapid, significant degradation.

Figure 5.

(A) Representative graph of changes in moduli for degrading PEG-SH hydrogels (sample P5H10) after exposure to l-cysteine. (B) Lowest G′ reached during the degradation of hydrogels after exposure to 10 mM l-cysteine normalized to G′eq (G′/G′eq; 0–100%) as a function of total exposure time (1 vs 2 min soak) to l-cysteine (n = 3). (C) Time after exposure to 10 mM l-cysteine required for hydrogel network to reach the lowest G′ as a function of total exposure time (1 vs 2 min soak) to l-cysteine (n = 3).

4. DISCUSSION

Here, we report the adaptation of SAOS rheology approaches to monitor time-dependent changes in storage and loss moduli for a library of enzymatically cross-linked PEG hydrogels under development for tissue engineering applications. The PEG monomer is commonly used as a backbone for a wide range of hydrogel-based biomaterials,42 making it ideal as a model system to develop approaches to monitor the kinetics of the cross-linking reaction required to form hydrogel networks. Light-based cross-linking reactions are commonly used to generate such hydrogel structures,43 and rapid reaction times and the means to locally alter the degree of light exposure have provided a facile means to generate complex cross-linked networks. Recently, alternative cross-linking methods have been described, including the use of guest–host reactions44 and enzymatically catalyzed reactions. Enzymatically catalyzed reactions hold particular promise for instances where exposure to light is difficult or unfeasible and mild reaction conditions are required, such as injectable hydrogels for biomedical applications where polymer solutions must gel only after they have entered the body.45 Such reactions, which could extend from minutes to hours, motivate the development of methods to determine a relevant timescale for gelation beyond just the critical gel point, the instant when the molecular weight diverges to infinity.46

The Winter–Chambon criterion has paved a rigorous way to determine the gel point for physically and chemically crosslinked gels.47,48 However, the application of the Winter–Chambon criterion is not always experimentally feasible,49 and reporting the crossover state (tcross) of the dynamic moduli is commonly used in its place. For systems with a fast gelation rate, the Winter–Chambon rule can be difficult to follow and the crossover state, which generally depends on the imposed frequency, has been commonly adopted in these cases.28–31,50 However, emerging needs to fabricate spatially and temporally complex biomaterial systems to replicate a wide range of transitional zones in tissues (e.g., orthopedic insertions51 and the margins of tumors52) introduce the need to understand not only the gel point of a system but also information about the overall kinetics of the cross-linking reaction.

We describe the use of SAOS rheology methods to monitor time-dependent changes in the storage and loss moduli for a library of enzymatically cross-linked PEG hydrogels as a function of the polymer (four-arm PEG-SH wt %) and reaction (H2O2 concentration) conditions. Equilibrium storage moduli for the library varied from 1 to 16 kPa, ideal for a wide range of soft-tissue applications.53,54 tcross varied from ~2 to ~12 min, showing a tunable rapidly gelling system suitable for cell encapsulation applications.55 We find that the crossover state and equilibrium storage modulus are sensitive to polymer wt % and H2O2, but there are concentrations that are able to saturate the reaction (low polymer, high H2O2, faster reaction; high polymer, low H2O2, slower reaction).

Physically, the critical gel point indicates the timescale at which a sol–gel transition occurs, but the interval over which materials undergo drastic changes of viscoelastic properties is not represented by this timescale. For instance, a rapid gelation process after some extended quiescence could have the same critical gel point as a slowly evolving gelation process with no quiescence, though there are clearly different mechanisms causing each. In addition to the critical gel point, the gelation interval provides a framework to describe the entirety of the gelation process, from nascent processes that begin to rapidly change a material’s viscoelastic properties to when the material has reached an equilibrium state. The knowledge of this interval involving sharp changes of viscoelasticity is important when characterizing the transient changes in material properties of a gelling system and when one wants to more accurately determine when the material has reached a state of stability. This metric is useful in a multitude of applications, from transient injectable systems, where a time frame exists during which the material is extrudable and past which the material has stabilized and become fully rigid,56 to cell culture hydrogels, where a material that quickly stabilizes during encapsulation may be better suited than one that changes in material properties over an extended period of time. In this basis, we proposed the use of the duration over which the derivative of G′ (and therefore the mutation number of Mours and Winter) is nonzero to indicate such a time interval for gelation. For our tested hydrogel system, increasing amounts of polymers not only delayed the crossover state but the gelation interval was also extended. Δtgel seemed to be more independent of H2O2 concentration than tcross and was approximately constant for a fixed polymer wt %. It is worth noting that tcross precedes the start of the Δtgel interval for all of the tested samples (Figure S3), further demonstrating that the Δtgel metric is essential for accurately representing the time frame over which gelation actually occurs. To show the broad applicability of Δtgel for other gelling systems, similar rheological analyses were carried out using gel-SH and gelatin polymer backbones. Gel-SH hydrogels were made using an identical HRP-catalyzed cross-linking chemistry, and gelatin hydrogels were made by cooling a solution of dissolved gelatin from ambient temperature to 10 °C. Although the polymer backbone and manner of gelation differed in these cases, both gelling systems had distinct Δtgel intervals preceded by tcross (Figure S6).

As polymers form cross-links and contort into various conformations, they travel through a large potential energy landscape, representing all possible polymer conformations and spatial positions of the interacting polymers in the system.57 Gelling systems navigate through this energy landscape until they reach conformational states that are energetically favorable, whether those be local minima representing pseudo-equilibrium states or a global minimum representing the overall equilibrium state the material can reach. We posit that as these materials undergo gelation, transitions into pseudo-equilibrium states, or local minima states in the energy landscape, are represented by shifts in the rate of change of viscoelastic properties, which can be monitored via time derivatives of G′ and G″. Two distinct peaks in dG′/dt can be seen throughout the Δtgel time window in the majority of hydrogel samples and a lower number of distinct peaks are seen in hydrogels that have longer gelation timescales (Figure 4). This suggests that it is less likely for these longer gelling systems to reach a secondary equilibrium conformational state represented by the second peak, due to changes in the energetics of the system brought about by system reaction parameters (polymer wt %, H2O2 concentration). It might also be that by changing these parameters, we have altered the energy landscape such that these low-energy conformational states no longer exist, motivating efforts beyond the scope of this study to evaluate the performance of these gelling systems at longer timescales. Temperature dependence measurements support our claim of there being multiple conformational energy states in our system, as multiple peaks were not apparent at lower temperatures (Figure S5).

While this manuscript prioritizes methods to monitor the kinetics of gelation, an analogous process is that of hydrogel degradation, often required to isolate cells, as well as secreted proteins and biomolecules from the hydrogel environment for analysis. While enzymatic approaches are often used for natural (e.g., collagen, gelatin, hyaluronic acid) hydrogels as well as PEG hydrogels containing enzymatically sensitive peptide sequences, it can lead to significant degradation of many of the biomolecules to be quantified.58 Further, direct exposure to proteolytic enzymes can lead to significant cell death, suggesting the opportunity to develop orthogonal degradation processes (e.g., sortase-catalyzed degradation58), as well as methods to quantify the kinetics of degradation. Therefore, here we report the adaptation of SAOS methods to monitor the degradation of PEG-SH hydrogels after exposure to l-cysteine. The viscoelastic properties of hydrogels reduced rapidly after exposure to l-cysteine, as reflected by the marked reduction in G′, similar to that reported for Zustiak et al. during the degradation of a PEG vinyl sulfone hydrogel.59 For this PEG-SH hydrogel, the dynamic moduli (G′, G″) show sharp decreases during the first 10 min after exposure to l-cysteine, resulting in a near linear change of G′ and G″, as seen in the semilog plot (Figure 5A). The degradation appears to slow down after the first 10 min until reaching equilibrium values within 20 min, possibly due to the depletion of l-cysteine within the swelled gels or cleaving of all existing cross-links in the hydrogel network.

Lastly, while secondary to developing methods to monitor the kinetics of gelation and degradation of a model PEG hydrogel, we report that with the addition of 0.1 wt % of thiolated gelatin macromers the PEG and gelatin hydrogel sustain encapsulated hMSCs through 48 h in culture (Table 1 and Figure S7). Further, a fraction of cells could be isolated from hydrogels (Table 1) after exposure to l-cysteine (5–50 mM) for times required to degrade the hydrogel network (<25 min), as the gel is degraded to the point that the solution is a fluid that can be readily manipulated. This provides the capability for the isolation of intact live cells after hydrogel culture for applications such as flow cytometry or analysis of gene expression and signaling pathway activation. While there remains an opportunity to improve the fraction of viable cells isolated from the hydrogel network via optimizing the l-cysteine concentration and exposure time, via the use of alternative cell populations, or via more cell-friendly degradation schemes, such efforts are secondary to our effort here, which demonstrates the proof of concept of a reversible gelation reaction scheme and the use of SAOS to monitor the kinetics of such processes.

5. CONCLUSIONS

We describe the gelation kinetics of an enzyme cross-linked PEG hydrogel. Mild reaction conditions, relatively short timescale of gelling, and final range of material stiffness lend themselves for use of this hydrogel system for use in soft-tissue biological applications, particularly those requiring cell encapsulation. Using SAOS rheometry, we observe that the characteristic gelation process depends on the wt % of polymer, H2O2 concentration, and system temperature. With a higher amount of H2O2 and reduced polymer present, the crossover state (tcross) generally occurs more rapidly. While a decrease in temperature appeared to slow gelation, the materials manifested the same equilibrium modulus G′eq once the networks fully formed. We describe a novel approach for describing the entirety of the gelation process, defining a gelation interval, Δtgel, via the time interval over which the derivative of the storage modulus is nonzero. Beyond considering the gelation as a single time point, this approach provides a framework to monitor shifts in viscoelastic properties of the material as they change and provides valuable information for applications involving in situ control of gelation processes.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01 DK099528, as well as the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbe r R01 CA197488 (B.A.C.H.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The authors are grateful for the funding for this study provided by the NSF Graduate Research Fellowship DGE-1144245 (R.S.H.C.). The authors are also grateful for additional funding provided by the Department of Chemical & Biomolecular Engineering and the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.biomac.9b00116.

Tested hydrogels, equilibrium water content of hydro-gels, frequency sweep of unperturbed hydrogels, plots for G′ and dG′/dt of hydrogels, time sweep of gelatin-incorporated hydrogels, temperature dependence time sweep, G′ and dG′/dt for gelatin hydrogels, and live/dead stain images (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Zhu J; Marchant RE Design properties of hydrogel tissue-engineering scaffolds. Expert Rev. Med. Devices 2011, 8, 607–626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Lin CC; Anseth KS PEG hydrogels for the controlled release of biomolecules in regenerative medicine. Pharm. Res. 2009, 26, 631–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Chaudhuri O; Gu L; Darnell M; Klumpers D; Bencherif SA; Weaver JC; Huebsch N; Mooney DJ Substrate stress relaxation regulates cell spreading. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, No. 6364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Discher DE; Mooney DJ; Zandstra PW Growth factors, matrices, and forces combine and control stem cells. Science 2009, 324, 1673–1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Huebsch N; Mooney DJ Inspiration and application in the evolution of biomaterials. Nature 2009, 462, 426–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Hennink WE; van Nostrum CF Novel crosslinking methods to design hydrogels. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2012, 64, 223–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Slaughter BV; Khurshid SS; Fisher OZ; Khademhosseini A; Peppas NA Hydrogels in Regenerative Medicine. Adv. Mater. 2009, 21, 3307–3329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Fairbanks BD; Scott TF; Kloxin CJ; Anseth KS; Bowman CN Thiol-Yne Photopolymerizations: Novel Mechanism, Kinetics, and Step-Growth Formation of Highly Cross-Linked Networks. Macromolecules 2009, 42, 211–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Kloxin AM; Benton JA; Anseth KS In situ elasticity modulation with dynamic substrates to direct cell phenotype. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Benton JA; DeForest CA; Vivekanandan V; Anseth KS Photocrosslinking of gelatin macromers to synthesize porous hydrogels that promote valvular interstitial cell function. Tissue Eng., Part A 2009, 15, 3221–3230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).DeForest CA; Polizzotti BD; Anseth KS Sequential click reactions for synthesizing and patterning three-dimensional cell microenvironments. Nat. Mater. 2009, 8, 659–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Kloxin AM; Tibbitt MW; Kasko AM; Fairbairn JA; Anseth KS, Tunable Hydrogels for External Manipulation of Cellular Microenvironments through Controlled Photodegradation. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 61–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Tibbitt MW; Kloxin AM; Dyamenahalli KU; Anseth KS Controlled two-photon photodegradation of PEG hydrogels to study and manipulate subcellular interactions on soft materials. Soft Matter 2010, 6, 5100–5108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Caliari SR; Perepelyuk M; Cosgrove BD; Tsai SJ; Lee GY; Mauck RL; Wells RG; Burdick JA Stiffening hydrogels for investigating the dynamics of hepatic stellate cell mechanotransduction during myofibroblast activation. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, No. 21387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Mahadik BP; Pedron Haba S; Skertich LJ; Harley BA The use of covalently immobilized stem cell factor to selectively affect hematopoietic stem cell activity within a gelatin hydrogel. Biomaterials 2015, 67, 297–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Font Tellado S; Balmayor ER; Van Griensven M Strategies to engineer tendon/ligament-to-bone interface: Biomaterials, cells and growth factors. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2015, 94, 126–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Demoor M; Ollitrault D; Gomez-Leduc T; Bouyoucef M; Hervieu M; Fabre H; Lafont J; Denoix JM; Audigie F; Mallein-Gerin F; Legendre F; Galera P Cartilage tissue engineering: molecular control of chondrocyte differentiation for proper cartilage matrix reconstruction. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Gen. Subj. 2014, 1840, 2414–2440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Burdick JA; Peterson AJ; Anseth KS Conversion and temperature profiles during the photoinitiated polymerization of thick orthopaedic biomaterials. Biomaterials 2001, 22, 1779–1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Baroli B Photopolymerization of biomaterials: issues and potentialities in drug delivery, tissue engineering, and cell encapsulation applications. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2006, 81, 491–499. [Google Scholar]

- (20).Kobayashi S; Uyama H; Kimura S Enzymatic Polymerization. Chem. Rev. 2001, 101, 3793–3818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Singh S; Topuz F; Hahn K; Albrecht K; Groll J Embedding of Active Proteins and Living Cells in Redox-Sensitive Hydrogels and Nanogels through Enzymatic Cross-Linking. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 3000–3003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Tanaka M; Matsuura K; Yoshioka S; Takahashi S; Ishimori K; Hori H; Morishima I Activation of hydrogen peroxide in horseradish peroxidase occurs within approximately 200 micro s observed by a new freeze-quench device. Biophys. J. 2003, 84, 1998–2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Halliwell B; Clement MV; Long LH Hydrogen peroxide in the human body. FEBS Lett. 2000, 486, 10–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Moriyama K; Minamihata K; Wakabayashi R; Goto M; Kamiya N Enzymatic preparation of a redox-responsive hydrogel for encapsulating and releasing living cells. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 5895–5898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Matsusaki M; Yoshida H; Akashi M The construction of 3D-engineered tissues composed of cells and extracellular matrices by hydrogel template approach. Biomaterials 2007, 28, 2729–2737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Lee CW; Rogers SA A sequence of physical processes quantified in LAOS by continuous local measures. Korea-Aust. Rheol. J. 2017, 29, 269–279. [Google Scholar]

- (27).Chambon F; Winter HH Analysis of linear viscoelasticity of a crosslinking polymer at the gel point. J. Rheol. 1986, 30, 367–382. [Google Scholar]

- (28).Ghosh K; Shu XZ; Mou R; Lombardi J; Prestwich GD; Rafailovich MH; Clark RA Rheological characterization of in situ cross-linkable hyaluronan hydrogels. Biomacromolecules 2005, 6, 2857–2865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Sahiner N; Singh M; De Kee D; John VT; McPherson GL Rheological characterization of a charged cationic hydrogel network across the gelation boundary. Polymer 2006, 47, 1124–1131. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Lee KY; Kong HJ; Larson RG; Mooney DJ Hydrogel formation via cell crosslinking. Adv. Mater. 2003, 15, 1828–1832. [Google Scholar]

- (31).Moura MJ; Figueiredo MM; Gil MH Rheological study of genipin cross-linked chitosan hydrogels. Biomacromolecules 2007, 8, 3823–3829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Winter HH Can the gel point of a cross-linking polymer be detected by theG? -G? crossover? Polym. Eng. Sci. 1987, 27, 1698–1702. [Google Scholar]

- (33).Kloxin AM; Tibbitt MW; Kasko AM; Fairbairn JA; Anseth KS Tunable hydrogels for external manipulation of cellular microenvironments through controlled photodegradation. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 61–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Kloxin AM; Kasko AM; Salinas CN; Anseth KS Photodegradable hydrogels for dynamic tuning of physical and chemical properties. Science 2009, 324, 59–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Deforest CA; Sims EA; Anseth KS Peptide-Functionalized Click Hydrogels with Independently Tunable Mechanics and Chemical Functionality for 3D Cell Culture. Chem. Mater. 2010, 22, 4783–4790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Tokuda EY; Leight JL; Anseth KS Modulation of matrix elasticity with PEG hydrogels to study melanoma drug responsiveness. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 4310–4318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Lin-Gibson S; Walls HJ; Kennedy SB; Welsh ER Reaction kinetics and gel properties of blocked diisocyinate crosslinked chitosan hydrogels. Carbohydr. Polym. 2003, 54, 193–199. [Google Scholar]

- (38).Moriyama K; Wakabayashi R; Goto M; Kamiya N Enzyme-mediated preparation of hydrogels composed of poly(ethylene glycol) and gelatin as cell culture platforms. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 3070–3073. [Google Scholar]

- (39).Aitken A; Learmonth M Estimation of Disulfide Bonds Using Ellman’s Reagent In The Protein Protocols Handbook; Walker JM, Ed.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, 2009; pp 1053–1055. [Google Scholar]

- (40).Schindelin J; Arganda-Carreras I; Frise E; Kaynig V; Longair M; Pietzsch T; Preibisch S; Rueden C; Saalfeld S; Schmid B; Tinevez JY; White DJ; Hartenstein V; Eliceiri K; Tomancak P; Cardona A Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Mours M; Winter HH Time-resolved rheometry. Rheol. Acta 1994, 33, 385–397. [Google Scholar]

- (42).Zhu J Bioactive modification of poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogels for tissue engineering. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 4639–4656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Nguyen KT; West JL Photopolymerizable hydrogels for tissue engineering applications. Biomaterials 2002, 23, 4307–4314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Rodell CB; Mealy JE; Burdick JA Supramolecular Guest–Host Interactions for the Preparation of Biomedical Materials. Bioconjugate Chem. 2015, 26, 2279–2289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Sivashanmugam A; Arun Kumar R; Vishnu Priya M; Nair SV; Jayakumar R An overview of injectable polymeric hydrogels for tissue engineering. Eur. Polym. J. 2015, 72, 543–565. [Google Scholar]

- (46).Flory PJ Principles of Polymer Chemistry; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, 1953; pp 1953. [Google Scholar]

- (47).Higham AK; Garber LA; Latshaw DC; Hall CK; Pojman JA; Khan SA Gelation and Cross-Linking in Multifunctional Thiol and Multifunctional Acrylate Systems Involving an in Situ Comonomer Catalyst. Macromolecules 2014, 47, 821–829. [Google Scholar]

- (48).Djabourov M Gelation—A review. Polym. Int. 1991, 25, 135–143. [Google Scholar]

- (49).Félix L; Hernández J; Argüelles-Monal WM; Goycoolea FM Kinetics of Gelation and Thermal Sensitivity of N-Isobutyryl Chitosan Hydrogels. Biomacromolecules 2005, 6, 2408–2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Yan C; Pochan DJ Rheological properties of peptide-based hydrogels for biomedical and other applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 3528–3540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Caliari SR; Weisgerber DW; Grier WK; Mahmassani Z; Boppart MD; Harley BA Collagen Scaffolds Incorporating Coincident Gradations of Instructive Structural and Biochemical Cues for Osteotendinous Junction Engineering. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2015, 4, 831–837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Pedron S; Polishetty H; Pritchard AM; Mahadik BP; Sarkaria JN; Harley BAC Spatially graded hydrogels for preclinical testing of glioblastoma anticancer therapeutics. MRS Commun. 2017, 7, 442–449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Wang T; Lai JH; Yang F Effects of Hydrogel Stiffness and Extracellular Compositions on Modulating Cartilage Regeneration by Mixed Populations of Stem Cells and Chondrocytes In Vivo. Tissue Eng., Part A 2016, 22, 1348–1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Wang C; Tong X; Yang F Bioengineered 3D brain tumor model to elucidate the effects of matrix stiffness on glioblastoma cell behavior using PEG-based hydrogels. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2014, 11, 2115–2125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Caliari SR; Burdick JA A practical guide to hydrogels for cell culture. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 405–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Kondiah PJ; Choonara YE; Kondiah PP; Marimuthu T; Kumar P; du Toit LC; Pillay V A Review of Injectable Polymeric Hydrogel Systems for Application in Bone Tissue Engineering. Molecules 2016, 21, No. 1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Wales D Energy Landscapes: Applications to Clusters, Biomolecules and Glasses; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- (58).Valdez J; Cook CD; Ahrens CC; Wang AJ; Brown A; Kumar M; Stockdale L; Rothenberg D; Renggli K; Gordon E; Lauffenburger D; White F; Griffith L On-demand dissolution of modular, synthetic extracellular matrix reveals local epithelial-stromal communication networks. Biomaterials 2017, 130, 90–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Zustiak SP; Leach JB Hydrolytically Degradable Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Hydrogel Scaffolds with Tunable Degradation and Mechanical Properties. Biomacromolecules 2010, 11, 1348–1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.