Abstract

Increasing overdose mortality and new HIV outbreaks in the US highlight the need to identify risk behavior profiles among people who inject drugs (PWID). We characterized latent classes of drug use among a community-based sample of 671 PWID in Baltimore during 2017 and evaluated associations of these classes with sharing syringes, obtaining syringes from pharmacies or syringe services programs (SSPs), and nonfatal overdose in the past six months. We identified three classes of current drug use: infrequent use (76% of participants), prescription drug use (12%), and heroin and/or cocaine injection (12%). PWID in the heroin and/or cocaine injection and prescription drug use classes had higher odds of both overdose and sharing syringes (relative to infrequent use). PWID in the prescription drug use class were 64% less likely to obtain syringes through SSPs/pharmacies relative to heroin and/or cocaine injection. Harm reduction programs need to engage people who obtain prescription drugs illicitly.

Keywords: People Who Inject Drugs, Syringe Sharing, Overdose, Harm Reduction, Latent Class Analysis

INTRODUCTION

Increases in nonmedical prescription opioid, heroin, and injection drug use and the introduction of illicitly manufactured fentanyl into the heroin supply have had major public health consequences for HIV and overdose (Peters et al., 2016; Rudd, Seth, David, & Scholl, 2016). A 2014–2015 HIV outbreak in Scott County, Indiana highlighted the vulnerability of rural US communities to syringe sharing and HIV transmission in the absence of harm reduction services (Peters et al., 2016). Increases in injection drug use have also led to a doubling of new hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections in the US, some of which has been attributed to rising prescription opioid injection (Bruneau, Roy, Arruda, Zang, & Jutras-Aswad, 2012; Puzhko et al., 2017; Zibbell et al., 2018; Zibbell, Hart-Malloy, Barry, Fan, & Flanigan, 2014).

Additionally, people who use drugs via any route are at risk for experiencing fatal and nonfatal overdose. Approximately 45% of people who use drugs experience a nonfatal overdose in their lifetime (Martins, Sampson, Cerdá, & Galea, 2015). Opioids were involved in 47,600 deaths in the US in 2017, a figure alarmingly close to the peak annual mortality from AIDS (50,628 deaths in 1995) (NIDA, 2018; CDC, 2011). The 5-fold rise in opioid overdose mortality rates since 1999 is attributed to steady increases in prescription opioid overdose, a rise in heroin overdoses beginning around 2011, and the introduction of illicitly manufactured fentanyl into the heroin supply around 2014 (CDC, 2017; NIDA, 2018). Taken together, changes in opioid use trends have had major implications for overdose risk and infectious disease transmission.

The magnitude of increases in overdose mortality and bloodborne virus incidence have been especially large in young, white, suburban and rural dwelling people who inject drugs (PWID) (NIDA, 2018; CDC, 2018). This may be due, in part, to differences in adoption of protective behaviors, such as engagement with harm reduction services (Marshall, Green, Yedinak, & Hadland, 2016), which have tended to exist primarily in urban settings (Des Jarlais et al., 2015). Recent research has highlighted a disengagement from SSPs among young, primarily white, people who use prescription opioids non-medically (Mateu-Gelabert, Guarino, Jessell, & Teper, 2015) and the increased likelihood of receptive syringe sharing among PWID obtaining syringes from pharmacies rather than SSPs (Zlotorzynska, Weidle, Paz-Bailey, Broz, & NHBS Study Group, 2018). It is unknown whether PWID who use prescription opioids in different contexts also report a disengagement from SSPs.

Drug use and its consequences have remained pervasive public health challenges in urban areas, including Baltimore, which has documented increased opioid overdose mortality rates alongside use of illicitly obtained prescription opioids and the contamination of the heroin supply with fentanyl (MDHMH, 2018; Park, Weir, Allen, Chaulk, & Sherman, 2018). While prescription drug use appears to be prevalent among current and former PWID in Baltimore, the polysubstance patterns that include heroin, cocaine, and prescription opioids have not been fully characterized in the fentanyl-era, nor has the relationship of these polysubstance use patterns with HIV risk behaviors and overdose been examined (Anagnostopoulos, Abraham, Genberg, Kirk, & Mehta, 2018; Khosla, Juon, Kirk, Astemborski, & Mehta, 2011). Using data from 2017, we characterized the predominant substance use typologies among a sample of 671 current and former PWID who participated in the AIDS Linked to the IntraVenous Experience Study (ALIVE) in Baltimore, MD, using a latent class analysis (LCA) (Vlahov et al., 1991). We also examined the relationship of these typologies with sharing syringes, obtaining syringes through a SSP or pharmacy, and overdose during the six months preceding study participation.

METHODS

Study Participation and Inclusion Criteria

The ALIVE study is a community-based prospective cohort study established in 1988 to characterize HIV incidence and natural history among current and former PWID in Baltimore, MD (Vlahov et al., 1991). Open recruitment of new participants occurred during 1988–1989, 1994–1995, 1998, 2005–2008, and 2015–2018. Participants were recruited through flyers at several locations (e.g., Baltimore City Needle Exchange Program, HIV clinics) and via community events. To be eligible to participate, individuals must be ≥18 years old, and report a history of injection drug use. Participation involves a bi-annual interview, HIV antibody and HIV viral load testing for HIV-seropositive participants, and an Audio Computer-Assisted Self-Interview (ACASI) to assess drug use during the past six months (Macalino, Celentano, Latkin, Strathdee, & Vlahov, 2002).

This analysis included the first semi-annual ALIVE visit in 2017 for the subset of participants who used (by injection or other modes) cocaine, crack, or heroin, or who used prescription opioids, sedatives, or tranquilizers that they obtained outside of a medical setting in the six months before interview. Of the 1,175 participants who had at least 1 study visit in 2017, 676 used one or more of the inclusion drugs. We excluded 5 additional participants with missing data for the following measures (described further below): HIV viral load, homelessness, overdose, and use of SSPs or pharmacies to obtain syringes, leaving 671 participants for the analysis. This study was approved by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Institutional Review Board and all participants provided written informed consent during their first ALIVE study visit.

Measures

Primary Drug Use Measures for the Latent Class Analysis

Participants reported the drugs they used and mode of use during the six months before interview via ACASI. We formed binary indicators for use of the following drugs: cocaine injection, heroin injection, speedball (cocaine and heroin together), prescription opioid injection (including Oxycontin, Percocet, codeine, Darvon, Percodan, Dilaudid, Demerol, and/or buprenorphine), crack smoking, cocaine snorting, heroin snorting, oral use of illicitly obtained prescription sedatives (including sleeping pills, barbiturates, Seconal, Quaaludes, chloral hydrates, and/or clonidine), oral use of illicitly obtained prescription tranquilizers or antianxiety drugs (including Valium, Librium, muscle relaxants, benzodiazepines, Klonopin, Ativan, and/or Xanax), and oral use of illicitly obtained prescription opioids (including methadone, Oxycontin, Percocet, codeine, Darvon, Percodan, Dilaudid, Demerol, and/or buprenorphine). Illicitly obtained prescription drugs included those obtained from the street, friends, or family. We summarized oral prescription sedative and/or tranquilizer use as one indicator as there was considerable overlap in the reported use of these two prescription drugs in our sample.

Primary Outcomes

The primary outcomes in this analysis included overdose (among all participants), sharing syringes (among those actively injecting), and obtaining syringes from a SSP or pharmacy (among those actively injecting). Participants reported whether they had experienced an overdose in the past six months after being read the following definition of an overdose: “a situation where, after using, you or another person passed out and couldn’t wake up. The lips of the person who overdosed might have turned blue and their breathing was very slow or stopped.” We defined syringe sharing as “shar[ing] needles, even once,” “borrow[ing] a needle from someone, even once,” “buy[ing] a needle from someone and you weren’t sure it was brand new, even once,” or “[going] to someone else’s place where people had shot up and you used someone else’s needles there, even once” during the six months before the interview. Finally, participants reported whether they obtained syringes through the Baltimore City Needle Exchange Program (BCNEP) van or a pharmacy in the last six months. The BCNEP van provides sterile injection equipment, trains clients to respond to an overdose, and distributes naloxone, an opioid antagonist that can reverse an opioid overdose, throughout Baltimore City (Gindi, Rucker, Serio-Chapman, & Sherman, 2009). Pharmacies also dispense sterile syringes and naloxone is available without an individual prescription via a standing order (Wen & Warren, 2018).

Covariates

Participant’s sex (male or female) and race (African American, white, or other) were recorded during their first study interview. We summarized age at the time of the 2017 interview and whether participants lived within Baltimore city. Participants reported whether they were homeless, incarcerated ≥1 week, or made <$5,000 legal income before taxes (i.e., excluding supplemental or social security or disability income) in the past 6 months. We measured past-week depressive symptom severity using the Center for Epidemiological Studies – Depression (CES-D) Scale (Radloff, 1977) and formed a binary indicator for severe depressive symptoms, defined as CES-D score ≥23 (Perdue, Hagan, Thiede, & Valleroy, 2003). Participants reported the frequency they consumed alcohol and whether they used marijuana or were prescribed methadone or buprenorphine in the past six months. We summarized whether they had ever been infected with HCV and, among a subset of 339 participants with available data, whether they had ever used fentanyl (that they knew of) that they obtained from the street (by any mode of use).

Analytic Strategy

Latent class analysis (LCA) is a clustering technique used to identify unobservable (i.e., latent) subgroups in a dataset based on the covariance patterns of several related, observed items (Lanza, Collins, Lemmon, & Schafer, 2007). We used LCA to identify latent drug use classes using nine dichotomous drug use variables: cocaine injection, heroin injection, speedball (concurrent cocaine and heroin injection), prescription opioid injection, heroin snorting, cocaine snorting, smoking crack, oral use of illicitly obtained prescription opioids, and oral use of illicitly obtained prescription sedatives and/or tranquilizers. We hypothesized that we would identify 3 to 5 classes based on prior LCAs in Baltimore (Harrell, Mancha, Petras, Trenz, & Latimer, 2012; Kuramoto, Bohnert, & Latkin, 2011). To characterize the number of latent classes, we compared model interpretability, fit indices, and model stability for models with two to six latent classes (Lanza et al., 2007).

After selecting the number of drug use classes, we assigned labels to each class by interpreting item response probabilities (i.e. the percentage of participants in each class that used each drug item) and by comparing behavioral attributes of substance use not included in the LCA model (e.g. route and frequency of use) by class. We also summarized the prevalence of each latent drug use class and each participant’s most likely class membership using their maximum posterior probability of class assignment. We examined bivariate relationships of most probable class membership with primary outcomes and covariates. We used SAS 9.4 with PROC LCA for analyses (Lanza et al., 2007). A comprehensive description of the LCA methods applied is available in the Supplemental Methods.

We examined the association of drug use class with overdose, syringe sharing, and obtaining syringes through the BCNEP or a pharmacy in the past six months using logistic regression. Analyses of syringe sharing and obtaining syringes were restricted to current PWID (i.e., participants who injected drugs in the past six months). Multivariable analyses adjusted for several potential confounders that were previously associated with drug use patterns and/or injection behaviors, including demographic characteristics (age, African American race, and gender), homelessness, HIV (status and viral load detectability), depressive symptoms, and alcohol use (Anagnostopoulos et al., 2018; Fu et al., 2012; Khosla et al., 2011; Knowlton et al., 2000; Linton, Celentano, Kirk, & Mehta, 2013; Song, Safaeian, Strathdee, Vlahov, & Celentano, 2000).

The practice of assigning individuals to one latent class by forming a categorical variable using their maximum posterior probability of class assignment can bias associations of class with outcomes towards the null (Clark & Muthén, 2009). Thus, we conducted a sensitivity analysis of the logistic regression results after removing individuals with <80% maximum posterior probability.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

Participants were a median age of 53 years, 68% were male, 74% were African American, 24% were white, and 77% earned <$5,000 in legal income in the past 6 months (Table 1). The most commonly used drug was crack (61%); 51% snorted heroin, 43% injected heroin, and 34% injected heroin and cocaine at the same time. Nearly 20% used illicitly obtained prescription opioids, 27% used illicitly obtained prescription sedatives and/or tranquilizers, and 27% smoked marijuana. Among the 339 participants with data available on fentanyl use, 40% reported that they had used fentanyl either alone or in combination with other drugs at some point in their lifetime. Of the 27% of participants who had HIV infection, 69% had a detectable viral load. Approximately 13% reported experiencing an overdose in the 6 months before the interview. Among the 64% of participants actively injecting drugs, 31% reported sharing syringes in the prior six months and 51% obtained syringes from the BCNEP or a pharmacy.

Table 1.

Drug Use, Sociodemographic Characteristics, Overdose, and HIV Risk Behaviors among a Sample of 671 Current and Former People who Inject Drugs in Baltimore, MD, 2017

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Total | 671 (100) |

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |

| Female | 215 (32.0) |

| Race | |

| African American | 493 (73.5) |

| White | 159 (23.7) |

| Other | 19 (2.8) |

| Homeless | 138 (20.6) |

| Incarcerated ≥7 days in past 6 months | 29 (4.3) |

| Legal income <$5000 in the past 6 months | 515 (77.3)a |

| Depression (CES-D Score ≥23) | 285 (42.5) |

| Residence location in past 6 monthsb | |

| In Baltimore city | 566 (86.5) |

| Outside Baltimore city | 88 (13.5) |

| Age, Median (IQR) | 52.7 (45.5–58.0) |

| Year recruited into ALIVE study | |

| 1988–1989 | 83 (12.4) |

| 1994–1995 | 42 (6.3) |

| 1998 | 27 (4.0) |

| 2005–2008 | 186 (27.7) |

| 2015–2018 | 333 (49.6) |

| Drug Use in Past 6 Months | |

| Injected cocaine | 176 (26.2) |

| Injected heroin | 285 (42.5) |

| Speedball (concurrent heroin and cocaine injection) | 231 (34.4) |

| Injected prescription opioids | 40 (6.0) |

| Snorted heroin | 344 (51.3) |

| Snorted cocaine | 115 (17.1) |

| Smoked crack | 407 (60.7) |

| Nonmedical prescription opioid use (oral use) | 132 (19.7) |

| Used to get high | 84 (63.6)c |

| Used to treat withdrawal symptoms | 77 (58.3)c |

| Nonmedical prescription sedatives and/or tranquilizer use (oral use) | 178 (26.5) |

| Used sedatives to get high | 81 (62.8)d |

| Used sedatives to treat withdrawal symptoms | 74 (56.9)d |

| Used tranquilizers to get high | 88 (64.2)e |

| Used tranquilizers to treat withdrawal symptoms | 75 (54.7)e |

| Alcohol use frequency | |

| Didn’t drink | 251 (37.4) |

| Drank >1 day per week | 373 (55.6) |

| Drank 7 days per week | 47 (7.0) |

| Used marijuana | 183 (27.3) |

| Years since initiating injection drug use, median (IQR) | 28.5 (19.7–36.6)f |

| Frequency of injecting drugs | |

| No injection drug use | 240 (35.8) |

| Injected <once per day | 215 (32.0) |

| Injected ≥once per day | 216 (32.2) |

| Frequency of using non-injection drugs | |

| No non-injection drugs used | 80 (11.9) |

| Used <once per day | 309 (46.1) |

| Used ≥once per day | 282 (42.0) |

| Number of drugs used | |

| 1 | 190 (28.3) |

| 2 | 166 (24.7) |

| 3–4 | 192 (28.6) |

| 5–6 | 92 (13.7) |

| ≥7 | 31 (4.6) |

| Median (IQR) no. drug used | 2 (1–4) |

| Drug use route | |

| Injection drug use only | 80 (11.9) |

| Non-injection drug use only | 240 (35.8) |

| Polyroute (injection and non-injection) | 351 (52.3) |

| Lifetime use of fentanyl from the streetg | |

| Yes | 134 (39.5) |

| No | 186 (54.9) |

| Refused to answer | 19 (5.6) |

| Prescribed opioid agonist therapy in the past 6 months | |

| Prescribed buprenorphine | 117 (17.4) |

| Prescribed methadone | 346 (51.6) |

| HIV and Hepatitis C status and risk behaviors in past 6 months | |

| HIV seropositive | 181 (27.0) |

| Detectable HIV viral load | 124 (68.5)h |

| Hepatitis C seropositive | 488 (73.5)i |

| Syringe sharing | |

| Did not inject drugs | 240 (35.8) |

| Injected drugs and did not share syringes | 296 (44.1) |

| Injected drugs and shared syringes | 135 (20.1) |

| Obtained syringes (from BCNEP or pharmacy) | |

| Did not inject drugs | 240 (35.8) |

| Injected drugs and did not obtain syringes | 211 (31.5) |

| Injected drugs and obtain syringes | 220 (32.8) |

| Overdosed in past 6 months | 86 (12.8) |

5 participants missing income information excluded from percentage calculation.

17 participants missing residence information excluded from percentage calculation.

Among 132 participants who used prescription opioids nonmedically.

131 participants used prescription sedatives nonmedically. Percentages are calculated among 130 who answered questions about sedative use to treat withdrawal and 129 who answered questions about sedative use to get high.

Among 137 participants who used prescription tranquilizers nonmedically.

Among 659 participants who reported age at first drug injection.

332 participants were not asked questions about fentanyl.

Among 181 participants with HIV infection.

Among 664 participants tested for HCV antibody.

Abbreviations: BCNEP: Baltimore City Needle Exchange Program; IQR: interquartile range.

Latent Drug Use Classes

The BIC and entropy supported a 3-class model, which also had optimal model stability (Supplemental Table 1). Other fit statistics (AIC, adjusted BIC, and the BLRT) favored a 6-class solution. We retained the 3-class solution, which maximized model interpretability.

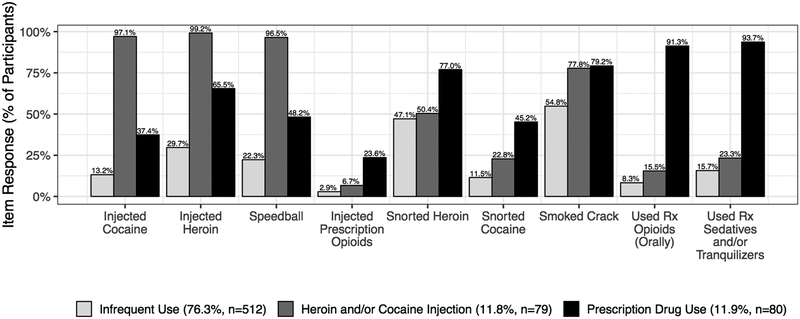

The largest class included 76% of participants (Figure 1). Because 75% of these participants injected drugs never or <once per day, 62% used non-injection drugs never or <once per day, and 98% used 4 or fewer substances, we named this class ‘Infrequent Use’ (Table 2). A second class termed ‘Heroin and/or Cocaine Injection’ included 12% of participants, among whom 99% injected heroin by itself, 97% injected cocaine by itself, and 97% injected heroin and cocaine together. The remaining 12% were classified in a ‘Prescription Drug Use’ class as they commonly used prescription opioids (91%) and sedatives and/or tranquilizers (94%) orally. Participants in the prescription drug use class also had the highest prevalence of snorting heroin (77%), snorting cocaine (45%), and injecting prescription opioids (24%) compared to other classes. Smoking crack was common in the prescription drug use (79% of participants) and heroin and/or cocaine injection (78%) classes compared to infrequent use (55%).

Figure 1.

Latent Classes of Drug Use among Current and Former People who Inject Drugs in Baltimore, MD, 2017

We interpreted item response probabilities for a 3-class model of drug use to characterize the predominant drug use typologies among participants in the ALIVE study during 2017. Most participants (76.3%) were assigned to an infrequent drug use class. All participants in the infrequent use class used ≤5 total substances and tended to use <once per day (Table 2). Nearly all participants in the heroin and/or cocaine injection class (11.8% of participants) injected heroin by itself (99.2%), cocaine by itself (97.1%), and speedball (heroin and cocaine at the same time, 96.5%). The remaining 11.9% of participants commonly used prescription drugs (93.7% used sedatives and/or tranquilizers and 91.3% used prescription opioids).

Table 2.

Bivariate Associations of Drug Use Class and Sociodemographic Characteristics, Overdose, and HIV Risk Behaviors 671 Current and Former People who Inject Drugs in Baltimore, MD, 2017

| Characteristic | Latent Drug Use Class | Chi-Squared p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infrequent Drug Use N (%) | Heroin and/or Cocaine Injection N (%) | Prescription Drug Use N (%) | ||

| Total | 512 (76.3) | 79 (11.8) | 80 (11.9) | -- |

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||||

| Female | 170 (33.2) | 14 (17.7) | 31 (38.8) | 0.009 |

| Race | ||||

| African American | 403 (78.7) | 41 (51.9) | 49 (61.3) | <0.0001a |

| White | 95 (18.6) | 35 (44.3) | 29 (36.3) | |

| Other | 14 (2.7) | 3 (3.8) | 2 (2.5) | |

| Homeless | 83 (16.2) | 36 (45.6) | 19 (23.8) | <0.0001 |

| Incarcerated ≥7 days in past 6 months | 20 (3.9) | 2 (2.5) | 7 (8.8) | 0.14a |

| Legal income <$5000 in the past 6 monthsb | 389 (76.7) | 64 (81.0) | 62 (77.5) | 0.70 |

| Depression (CES-D Score ≥23) in the past 6 months | 197 (38.5) | 37 (46.8) | 51 (63.8) | <0.0001 |

| Residence in the past 6 monthsc | ||||

| Baltimore city | 439 (86.9) | 59 (83.1) | 68 (87.2) | 0.67 |

| Outside Baltimore city | 66 (13.1) | 12 (16.9) | 10 (12.8) | |

| Age, median (IQR) | 53.6 (47.0–58.5) | 47.4 (39.3–56.6) | 49.4 (41.3–55.1) | <0.0001d |

| Year recruited into ALIVE study | ||||

| 1988–1989 | 67 (13.1) | 12 (15.2) | 4 (5.0) | <0.0001 |

| 1994–1995 | 39 (7.6) | 1 (1.3) | 2 (2.5) | |

| 1998 | 26 (5.1) | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0) | |

| 2005–2008 | 157 (30.7) | 16 (20.3) | 13 (16.3) | |

| 2015–2018 | 223 (43.6) | 49 (62.0) | 61 (76.3) | |

| Drug use in past 6 months | ||||

| Used prescription opioids to get highe | 13 (30.2) | 5 (45.5) | 66 (84.6) | <0.0001a |

| Used prescription opioids to treat withdrawal symptomse | 18 (41.9) | 4 (36.4) | 55 (70.5) | 0.0031a |

| Used prescription sedatives to get highf | 28 (49.1) | 8 (80.0) | 45 (72.6) | 0.017a |

| Used prescription sedatives to treat withdrawal symptomsf | 26 (45.6) | 8 (80.0) | 40 (63.5) | 0.046a |

| Used prescription tranquilizers to get highg | 30 (53.6) | 11 (64.7) | 47 (73.4) | 0.077 |

| Used prescription tranquilizers to treat withdrawal symptomsg | 26 (46.4) | 10 (58.8) | 39 (60.9) | 0.26 |

| Alcohol use frequency | ||||

| Did not drink | 203 (39.7) | 31 (39.2) | 17 (21.3) | 0.0016 |

| Drank >1 day per week | 276 (53.9) | 46 (58.2) | 51 (63.8) | |

| Drank 7 days per week | 33 (6.5) | 2 (2.5) | 12 (15.0) | |

| Used marijuana | 110 (21.5) | 28 (35.4) | 45 (56.3) | <0.0001 |

| Years since initiating injection drug use, median (IQR)h | 29.5 (20.9–37.0) | 23.2 (15.6–34.6) | 23.5 (15.4–32.4) | 0.0009d |

| Frequency of injecting drugs | ||||

| No injection drug use | 230 (44.9) | 0 (0) | 10 (12.5) | <0.0001 |

| Injected <once per day | 154 (30.1) | 24 (30.4) | 37 (46.3) | |

| Injected ≥once per day | 128 (25.0) | 55 (69.6) | 33 (41.3) | |

| Frequency of using non-injection drugs | ||||

| No non-injection drugs used | 72 (14.1) | 8 (10.1) | 0 (0) | 0.0002 |

| Used <once per day | 244 (47.7) | 27 (34.2) | 38 (47.5) | |

| Used ≥once per day | 196 (38.3) | 44 (55.7) | 42 (52.5) | |

| No. drugs used | ||||

| 1 | 190 (37.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | <0.0001 |

| 2 | 166 (32.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| 3–4 | 146 (28.5) | 29 (36.7) | 17 (21.3) | |

| 5–6 | 10 (2.0) | 44 (55.7) | 38 (47.5) | |

| ≥7 | 0 (0) | 6 (7.6) | 25 (31.3) | |

| Median (IQR) no. drugs used | 2 (1–3) | 5 (4–6) | 6 (5–7) | <0.0001d |

| Drug use route | ||||

| Injection drug use only | 72 (14.1) | 8 (10.1) | 0 (0) | <0.0001a |

| Non-injection drug use only | 230 (44.9) | 0 (0) | 10 (12.5) | |

| Polyroute (injection and non-injection) | 210 (41.0) | 71 (89.9) | 70 (87.5) | |

| Lifetime use of fentanyl from the streeti | ||||

| Yes | 104 (36.9) | 17 (58.6) | 13 (46.4) | 0.080a |

| No | 163 (57.8) | 11 (37.9) | 12 (42.9) | |

| Refused to answer | 15 (5.3) | 1 (3.5) | 3 (10.7) | |

| Prescribed opioid agonist therapy in past 6 months | ||||

| Prescribed buprenorphine | 88 (17.2) | 11 (13.9) | 18 (22.5) | 0.35 |

| Prescribed methadone | 266 (52.0) | 41 (51.9) | 39 (48.8) | 0.87 |

| HIV | ||||

| HIV-positive | 148 (28.9) | 19 (24.1) | 14 (17.5) | 0.084 |

| Detectable HIV viral loadj | 97 (65.5) | 17 (89.5) | 10 (71.4) | 0.10 |

| Hepatitis C Virus seropositivek | 376 (73.9) | 63 (82.9) | 49 (62.0) | 0.012 |

| Shared syringesl | 69 (24.5) | 39 (49.4) | 27 (38.6) | <0.0001 |

| Obtained syringes (from BCNEP or pharmacy)l | 128 (45.4) | 56 (70.9) | 36 (51.4) | 0.0003 |

| Overdosed in past 6 months | 41 (8.0) | 20 (25.3) | 25 (31.3) | <0.0001 |

Fisher exact test p-value.

5 participants missing income information excluded from percentage calculation.

17 participants missing residence information excluded from percentage calculation.

Kruskal-Wallis test p-value.

Among 132 participants who used prescription opioids nonmedically.

131 participants used prescription sedatives nonmedically. Percentages are calculated among 130 who answered questions about sedative use to treat withdrawal and 129 who answered questions about sedative use to get high.

Among 137 participants who used prescription tranquilizers nonmedically.

Among 659 participants who reported age at first drug injection.

332 participants were not asked questions about fentanyl use.

Among 181 participants with HIV infection.

Among 664 participants with a completed hepatitis C antibody test.

Among 429 participants who injected drugs in the past 6 months.

Abbreviations: BCNEP: Baltimore City Needle Exchange Program; IQR: Interquartile range; No.: Number.

In bivariate analyses, participants in the prescription drug use and infrequent use classes were more commonly female than in the heroin and/or cocaine injection class (p=0.009). Participants in the heroin and/or cocaine injection and prescription drug use classes were younger (p<0.0001), more often white (p<0.0001), more commonly active injectors (<0.0001), and had initiated injecting drugs more recently (p=0.0009). Participants in the prescription drug use class more commonly experienced depressive symptoms (p<0.0001), drank alcohol (p=0.002), and smoked marijuana (p<0.0001). Participants in the heroin and/or cocaine injection class were more likely to experience homelessness (p<0.0001) and inject drugs daily (p<0.0001). Among participants who used illicitly obtained prescription opioids, those in the prescription drug use class most commonly used prescription opioids to get high (p<0.0001) or to treat withdrawal symptoms (p=0.003).

HIV prevalence was highest in the infrequent use class (29%) compared to the other classes though this was of marginal statistical significance (p=0.08). Among participants living with HIV, 90% of participants in the heroin and/or cocaine injection class were not virally suppressed vs. 71% in the prescription drug use class and 66% of those in the infrequent use class (p=0.1). HCV infection was most prevalent among participants who injected heroin and/or cocaine (83%) and least common among the prescription drug use class (62%, p=0.01).

Overdose, Syringe Sharing, and Obtaining Syringes (from SSP or Pharmacy)

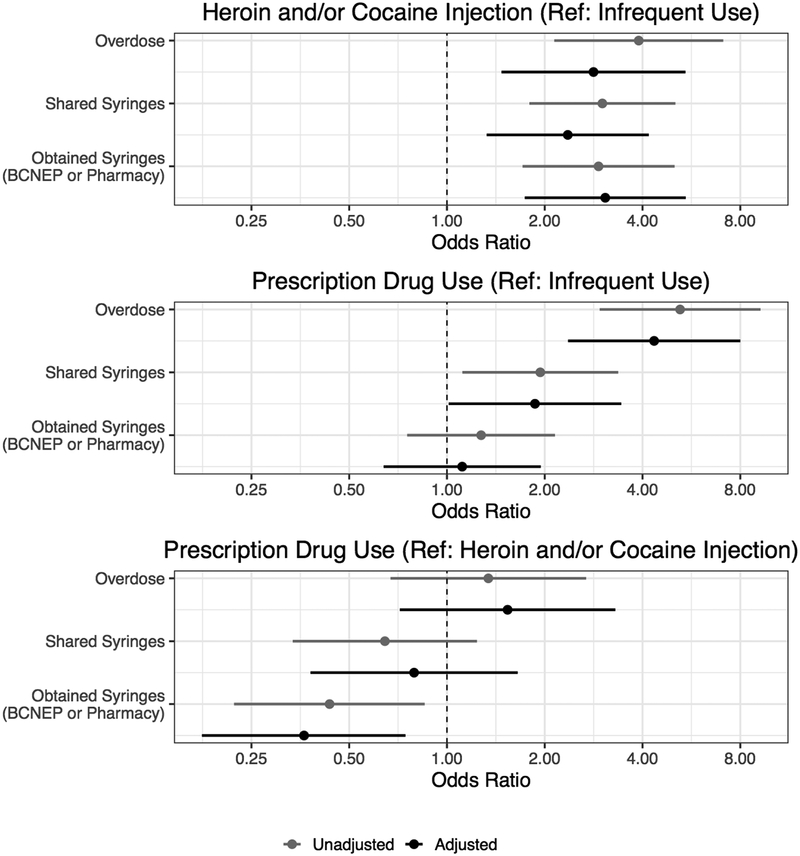

Relative to participants with infrequent use, participants in the heroin and/or cocaine injection class had 2.8-fold higher odds of reporting an overdose in the prior six months (95% CI: 1.5–5.4) and participants in the prescription drug use class had 4.3-fold higher odds of overdose (95% CI: 2.4–8.0) after adjusting for age, race, gender, homelessness, HIV status, depressive symptoms, and alcohol use (Figure 2). Current PWID in the heroin and/or cocaine injection class had 2.4-fold higher odds of sharing syringes (95% CI: 1.3–4.2) in the past 6 months than current PWID in the infrequent use class after adjustment. Current PWID in the prescription drug use class had 1.9-fold higher odds of sharing syringes (95% CI: 1.0–3.4, p=0.046) in the past 6 months relative to current PWID in the infrequent use class after adjustment.

Figure 2.

Associations of Drug Use Class with Overdose, Syringe Sharing, and Obtaining Syringes among 671 Current and Former People who Inject Drugs in Baltimore, MD, 2017

We examined how membership in the heroin and/or cocaine injection (top) and prescription drug use classes (middle) was associated with three outcomes relative to infrequent use: overdose, syringe sharing (among 431 participants who injected drugs in the past 6 months), and obtaining syringes from the Baltimore City Needle Exchange Program (BCNEP) or a pharmacy (among 431 participants who injected drugs in the past 6 months) using logistic regression. We also compared prescription drug use with heroin and/or cocaine injection (bottom). Adjusted results present the association of class with outcomes after adjustment for age, African American race, gender, homelessness, HIV (status and viral load detectability), depression, and alcohol use. Participants in the prescription drug use class had elevated odds of overdose and sharing syringes, but not of obtaining syringes compared to participants in the infrequent use class. Participants in the heroin and/or cocaine injection classes had higher odds of overdose, sharing syringes, and obtaining syringes relative to participants in the infrequent use class. Participants in the prescription drug use class were less likely to obtain syringes relative to participants in the heroin and/or cocaine injection class.

Current PWID in the heroin and/or cocaine injection class were more likely to obtain syringes through the BCNEP or a pharmacy in the past 6 months relative to infrequent use participants (adjusted odds ratio, aOR: 3.1, 95% CI: 1.7–5.4). There was no difference in obtaining syringes between current PWID in the prescription drug use class and the infrequent use class (aOR: 1.1, 95% CI: 0.64–1.9). Relative to current PWID in the heroin and/or cocaine injection class, those in the prescription drug use class had 64% lower odds of obtaining syringes from the BCNEP or a pharmacy (aOR: 0.36, 95% CI: 0.18–0.75). The magnitude and significance of most results was unchanged in a sensitivity analysis among 621 participants with ≥80% posterior probability of class assignment (Supplemental Table 2); however, syringe sharing was only marginally more common among current PWID in the prescription drug use class relative those in the infrequent use class (p=0.1).

DISCUSSION

Our study identified three classes of drug use among a community-based sample of current and former PWID who recently used drugs in Baltimore in 2017. While the majority were characterized by infrequent use, nearly one quarter either injected heroin and/or cocaine or used prescription opioids, sedatives, and/or tranquilizers alongside illicit substances. The most striking finding was that PWID who predominantly used prescription drugs were at comparable risk of overdose and as likely to share syringes as those injecting heroin and/or cocaine. However, they were significantly less likely to obtain syringes through the BCNEP or a pharmacy than the heroin and/or cocaine injection class.

The results of our analysis among current and former PWID in Baltimore in 2017 differed from two previous LCAs among people who used heroin and/or cocaine in Baltimore during 1997–1998 and 2001–2006, at the beginning of a two-decade increase in opioid use and overdose (Harrell et al., 2012; Kuramoto et al., 2011). Kuramoto et al. described 3 classes of PWID: heroin injecting (13% of participants), heroin and cocaine injecting (38%), and polydrug and polyroute injecting (8%) and 2 classes of non-PWID: crack smoking (14%) and heroin snorting (26%) (Kuramoto et al., 2011). Harrell et al. identified 3 classes: heroin injecting (21.8%), polysubstance use (predominately heroin and cocaine injection, 34.8%), and crack smoking/nasal heroin (43.5%) (Harrell et al., 2012). Consistent with temporal increases in nonmedical prescription drug use and related overdose, our study characterized a new group of PWID who used prescription drugs, commonly alongside snorting heroin and smoking crack (CDC, 2017; NIDA, 2018). In alignment with both studies, sharing syringes was associated with heroin and cocaine injection (Harrell et al., 2012; Kuramoto et al., 2011). The infrequent use group we identified may overlap with the crack smoking/nasal heroin class described by Harrell et al., though crack use was highly prevalent across all classes in our study (Harrell et al., 2012).

The prevalence of using illicitly obtained prescription opioids in our study using data from 2017 was similar to previous estimates among ALIVE participants in 2005–2014 (8–17% used prescription opioids) (Khosla et al., 2011; Anagnostopoulos et al., 2018; Genberg et al., 2013). However, use of illicitly obtained prescription sedatives and/or tranquilizers was more common than previous estimates (approximately 5–12%), though this likely reflects the inclusion criteria we applied (i.e. use of an illicit substance or illicitly obtained prescription drugs in the past six months) (Anagnostopoulos et al., 2018; Khosla et al., 2011). Polysubstance use among participants who used prescription drugs (e.g., heroin, cocaine, alcohol, and marijuana) remained common, and may contribute to the increased nonfatal overdose risk in this group relative to infrequent use, especially given the dangers of combining opioids with prescription tranquilizers (e.g. benzodiazepines) and/or alcohol (Anagnostopoulos et al., 2018; Kandel, Hu, Griesler, & Wall, 2017).

PWID in the prescription drug use class were similarly likely to share syringes, but less likely to obtain syringes from a SSP or pharmacy compared to PWID who injected heroin and/or cocaine. This finding aligns with prior work, including a study among young people who used prescription opioids in New York City that highlighted a preference for pharmacies as a source of sterile syringes over SSPs (Mateu-Gelabert et al., 2015). Another study suggested that obtaining syringes from pharmacies (rather than SSPs) was associated with younger age, white race, injecting less often than daily, primarily injecting prescription opioids, and receptively sharing syringes (Zlotorzynska et al., 2018).

The increased risk of overdose, potential for bloodborne virus infection and transmission, and a disengagement from SSPs and pharmacies among PWID who used illicitly obtained prescription drugs highlight an opportunity for harm reduction program outreach and expansion. These participants were more commonly female and experienced depressive symptoms in the six months before the survey. About 60% were African American and 36% white. Polyroute and polysubstance use and injecting less than daily were common. Conversely, BCNEP clients are primarily male (69%), African American (73%), aged ≥30 years (86%), and injected an average of four times per day (Gindi et al., 2009). Efforts to engage women, both African Americans and people of other races, and people who do not inject on a daily basis may increase the representation of BCNEP clients who use prescription drugs. Further, the high prevalence of depression highlights an opportunity to offer referrals to mental health services when these individuals engage with SSPs.

Participants in the heroin and/or cocaine injection class were both more likely to share syringes and to obtain syringes through a SSP or pharmacy than participants in the infrequent use class, suggesting that access to sterile syringes did not prevent syringe sharing among participants in the heroin and/or cocaine injection class. There are several potential drivers of syringe sharing, including relationship dynamics with potential partners, the normalization of sharing among peers, HIV status, perception of HIV risk, daily or more frequent injection, psychological functioning, obtaining syringes from pharmacies (versus SSPs), injecting in public spaces, residential instability, and incarceration history (Zlotorzynska et al., 2018; Golub et al., 2007; Mackesy-Amiti, Donenberg, & Ouellet, 2014; Morris et al., 2014; Heimer et al., 2015; Muñoz, Burgos, Cuevas-Mota, Teshale, & Garfein, 2015; Staton et al., 2017; Boodram, Hotton, Shekhtman, Gutfraind, & Dahari, 2018; Hunter et al., 2018). One potential explanation for the increased syringe sharing in both the heroin and/or cocaine injection and prescription drug use classes relative to infrequent use in our study is their greater frequency of injecting drugs. Assessing other reasons for sharing syringes could inform future harm reduction programming for injection safety. Harm reduction programming should also include overdose prevention (e.g. naloxone distribution) given the elevated overdose risk from the introduction of illicitly manufactured fentanyl into the heroin supply, which may explain some of the elevated overdose risk among the heroin and/or cocaine injection and prescription drug use classes that we observed (Peters et al., 2016; Rudd, Seth, David, & Scholl, 2016).

Most participants in our study (73%) were HIV seronegative, emphasizing an opportunity for infection prevention. Approximately two-thirds of participants living with HIV had a detectable HIV viral load, higher than prior studies among ALIVE participants who were not actively using drugs (Viswanathan et al., 2015). A particularly concerning finding was that nearly all participants in the heroin and/or cocaine injection class living with HIV were not virally suppressed and that nearly half of these participants reported having shared syringes. These results emphasize the need for safe injection practices and interventions to bolster engagement in HIV care among people actively using drugs. Counterintuitively, HIV prevalence was highest in our lowest risk class, infrequent use. However, on closer examination, participants in the infrequent use class also had the highest prevalence of viral suppression, had been injecting drugs for the longest duration, and were older relative to participants in other classes, suggesting that some of these participants may have acquired HIV several years ago and have since stopped sharing syringes.

Limitations

Our findings should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. All data are self-reported (with the exception of HIV and HCV testing) and subject to recall bias. Social desirability may have influenced participant disclosures around drug use, overdose history, and other information (Latkin & Vlahov, 1998; Latkin, Vlahov, & Anthony, 1993; Macalino et al., 2002). Second, available data limit our ability to separately evaluate whether PWID obtained syringes through SSPs versus pharmacies despite that utilizing these venues is differentially associated with overdose and HIV risk (Zlotorzynska et al., 2018). Finally, we evaluated the association of drug use classes with outcomes by assigning participants to their most probable latent drug use class, which may have biased associations towards the null (Bolck, Croon, & Hagenaars, 2004; Clark & Muthén, 2009; Vermunt, 2010). However, we found little change in our conclusions during a sensitivity analysis restricted to participants assigned to a single latent class with >80% probability.

CONCLUSIONS

PWID who used prescription drugs and those who injected heroin and cocaine were more likely to personally experience a recent overdose relative to those who used fewer substances (i.e., infrequent use). What was particularly concerning was that persons characterized by prescription drug use more commonly reported sharing syringes but did not report a higher frequency of obtaining syringes from a SSP or pharmacy relative to infrequent use. Further, current PWID in the prescription drug use class were less likely to obtain syringes than those in the heroin and/or cocaine injection class. Participants who injected heroin and cocaine were more likely to overdose, share syringes, and obtain syringes from a SSP or pharmacy than those with infrequent use. These findings suggest that harm reduction providers may need alternative models for engaging people who use prescription drugs that they obtain from nonmedical sources.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA036297 and DA012568), the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (AI102623), and the Johns Hopkins University Center for AIDS Research (P30AI094189).

REFERENCES

- Anagnostopoulos A, Abraham AG, Genberg BL, Kirk GD, & Mehta SH (2018). Prescription drug use and misuse in a cohort of people who inject drugs (PWID) in Baltimore. Addictive Behaviors, 81, 39–45. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.01.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolck A, Croon M, & Hagenaars J (2004). Estimating Latent Structure Models with Categorical Variables: One-Step Versus Three-Step Estimators. Political Analysis, 12(1), 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Boodram B, Hotton AL, Shekhtman L, Gutfraind A, & Dahari H (2018). High-Risk Geographic Mobility Patterns among Young Urban and Suburban Persons who Inject Drugs and their Injection Network Members. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 95(1), 71–82. 10.1007/s11524-017-0185-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruneau J, Roy E, Arruda N, Zang G, & Jutras-Aswad D (2012). The rising prevalence of prescription opioid injection and its association with hepatitis C incidence among street-drug users. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 107(7), 1318–1327. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03803.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. (2011). HIV surveillance--United States, 1981–2008. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 60(21), 689–693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. (2017, August 30). Understanding the Epidemic | Drug Overdose | CDC Injury Center. Retrieved May 22, 2018, from https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/epidemic/index.html [Google Scholar]

- CDC. (2018). Viral Hepatitis Surveillance - United States, 2016, 75. [Google Scholar]

- Clark S, & Muthén B (2009). Relating Latent Class Analysis Results to Variables not Included in the Analysis. University of California, Los Angeles: Retrieved from http://statmodel2.com/download/relatinglca.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Des Jarlais DC, Nugent A, Solberg A, Feelemyer J, Mermin J, & Holtzman D (2015). Syringe Service Programs for Persons Who Inject Drugs in Urban, Suburban, and Rural Areas - United States, 2013. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 64(48), 1337–1341. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6448a3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu T, Westergaard RP, Lau B, Celentano DD, Vlahov D, Mehta SH, & Kirk GD (2012). Changes in sexual and drug-related risk behavior following antiretroviral therapy initiation among HIV-infected injection drug users. AIDS (London, England), 26(18), 2383–2391. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835ad438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genberg BL, Gillespie M, Schuster CR, Johanson C-E, Astemborski J, Kirk GD, … Mehta SH (2013). Prevalence and correlates of street-obtained buprenorphine use among current and former injectors in Baltimore, Maryland. Addictive Behaviors, 38(12), 2868–2873. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gindi RM, Rucker MG, Serio-Chapman CE, & Sherman SG (2009). Utilization patterns and correlates of retention among clients of the needle exchange program in Baltimore, Maryland. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 103(3), 93–98. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.12.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub ET, Strathdee SA, Bailey SL, Hagan H, Latka MH, Hudson SM, … DUIT Study Team. (2007). Distributive syringe sharing among young adult injection drug users in five U.S. cities. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 91 Suppl 1, S30–38. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell PT, Mancha BE, Petras H, Trenz RC, & Latimer WW (2012). Latent classes of heroin and cocaine users predict unique HIV/HCV risk factors. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 122(3), 220–227. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimer R, Levina OS, Osipenko V, Ruiz MS, Sergeyev B, Sirotkin AV, & Vyshemirskaya I (2015). Impact of incarceration experiences on reported HIV status and associated risk behaviours and disease comorbidities. European Journal of Public Health, 25(6), 1089–1094. 10.1093/eurpub/ckv157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter K, Park JN, Allen ST, Chaulk P, Frost T, Weir BW, & Sherman SG (2018). Safe and unsafe spaces: Non-fatal overdose, arrest, and receptive syringe sharing among people who inject drugs in public and semi-public spaces in Baltimore City. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 57, 25–31. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.03.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Hu M-C, Griesler P, & Wall M (2017). Increases from 2002 to 2015 in prescription opioid overdose deaths in combination with other substances. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 178, 501–511. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.05.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khosla N, Juon HS, Kirk GD, Astemborski J, & Mehta SH (2011). Correlates of non-medical prescription drug use among a cohort of injection drug users in Baltimore City. Addictive Behaviors, 36(12), 1282–1287. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.07.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowlton AR, Latkin CA, Chung S, Hoover DR, Ensminger M, & Celentano DD (2000). HIV and Depressive Symptoms Among Low-Income Illicit Drug Users. AIDS and Behavior, 4(4), 353–360. 10.1023/A:1026450405989 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuramoto SJ, Bohnert ASB, & Latkin CA (2011). Understanding subtypes of inner-city drug users with a latent class approach. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 118(2–3), 237–243. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.03.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza ST, Collins LM, Lemmon DR, & Schafer JL (2007). PROC LCA: A SAS Procedure for Latent Class Analysis. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(4), 671–694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latkin CA, & Vlahov D (1998). Socially desirable response tendency as a correlate of accuracy of self-reported HIV serostatus for HIV seropositive injection drug users. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 93(8), 1191–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latkin CA, Vlahov D, & Anthony JC (1993). Socially desirable responding and self-reported HIV infection risk behaviors among intravenous drug users. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 88(4), 517–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linton SL, Celentano DD, Kirk GD, & Mehta SH (2013). The longitudinal association between homelessness, injection drug use, and injection-related risk behavior among persons with a history of injection drug use in Baltimore, MD. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 132(3), 457–465. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macalino GE, Celentano DD, Latkin C, Strathdee SA, & Vlahov D (2002). Risk behaviors by audio computer-assisted self-interviews among HIV-seropositive and HIV-seronegative injection drug users. AIDS Education and Prevention: Official Publication of the International Society for AIDS Education, 14(5), 367–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackesy-Amiti ME, Donenberg GR, & Ouellet LJ (2014). Psychiatric correlates of injection risk behavior among young people who inject drugs. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors: Journal of the Society of Psychologists in Addictive Behaviors, 28(4), 1089–1095. 10.1037/a0036390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall BDL, Green TC, Yedinak JL, & Hadland SE (2016). Harm reduction for young people who use prescription opioids extra-medically: Obstacles and opportunities. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 31, 25–31. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2016.01.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins SS, Sampson L, Cerdá M, & Galea S (2015). Worldwide Prevalence and Trends in Unintentional Drug Overdose: A Systematic Review of the Literature. American Journal of Public Health, 105(11), 2373 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302843a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mateu-Gelabert P, Guarino H, Jessell L, & Teper A (2015). Injection and sexual HIV/HCV risk behaviors associated with nonmedical use of prescription opioids among young adults in New York City. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 48(1), 13–20. 10.1016/j.jsat.2014.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MDHMH. (2018). Unintentional Drug- and Alcohol-Related Intoxication Deaths in Maryland Annual Report, 2017 (pp. 1–58). Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; Retrieved from https://bha.health.maryland.gov/OVERDOSE_PREVENTION/Documents/Drug_Intox_Report_2017.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Morris MD, Evans J, Montgomery M, Yu M, Briceno A, Page K, & Hahn JA (2014). Intimate injection partnerships are at elevated risk of high-risk injecting: a multi-level longitudinal study of HCV-serodiscordant injection partnerships in San Francisco, CA. PloS One, 9(10), e109282 10.1371/journal.pone.0109282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz F, Burgos JL, Cuevas-Mota J, Teshale E, & Garfein RS (2015). Individual and socio-environmental factors associated with unsafe injection practices among young adult injection drug users in San Diego. AIDS and Behavior, 19(1), 199–210. 10.1007/s10461-014-0815-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIDA. (2018, August 9). Overdose Death Rates. Retrieved October 24, 2018, from https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates [Google Scholar]

- Park JN, Weir BW, Allen ST, Chaulk P, & Sherman SG (2018). Fentanyl-contaminated drugs and non-fatal overdose among people who inject drugs in Baltimore, MD. Harm Reduction Journal, 15(1), 34 10.1186/s12954-018-0240-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perdue T, Hagan H, Thiede H, & Valleroy L (2003). Depression and HIV risk behavior among Seattle-area injection drug users and young men who have sex with men. AIDS Education and Prevention: Official Publication of the International Society for AIDS Education, 15(1), 81–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters PJ, Pontones P, Hoover KW, Patel MR, Galang RR, Shields J, … Indiana HIV Outbreak Investigation Team. (2016). HIV Infection Linked to Injection Use of Oxymorphone in Indiana, 2014–2015. The New England Journal of Medicine, 375(3), 229–239. 10.1056/NEJMoa1515195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puzhko S, Roy É, Jutras-Aswad D, Artenie AA, Fortier E, Zang G, & Bruneau J (2017). High hepatitis C incidence in relation to prescription opioid injection and poly-drug use: Assessing barriers to hepatitis C prevention. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 47, 61–68. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.05.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D Scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. 10.1177/014662167700100306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, & Scholl L (2016). Increases in Drug and Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths - United States, 2010–2015. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 65(5051), 1445–1452. 10.15585/mmwr.mm655051e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song JY, Safaeian M, Strathdee SA, Vlahov D, & Celentano DD (2000). The prevalence of homelessness among injection drug users with and without HIV infection. Journal of Urban Health, 77(4), 678–687. 10.1007/BF02344031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staton M, Strickland JC, Tillson M, Leukefeld C, Webster JM, & Oser CB (2017). Partner Relationships and Injection Sharing Practices among Rural Appalachian Women. Women’s Health Issues: Official Publication of the Jacobs Institute of Women’s Health, 27(6), 652–659. 10.1016/j.whi.2017.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermunt J (2010). Latent Class Modeling with Covariates: Two Improved Three-Step Approaches. Political Analysis, 18(4), 450–469. [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan S, Detels R, Mehta SH, Macatangay BJC, Kirk GD, & Jacobson LP (2015). Level of Adherence and HIV RNA Suppression in the Current Era of Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART). AIDS and Behavior, 19(4), 601–611. 10.1007/s10461-014-0927-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlahov D, Anthony JC, Munoz A, Margolick J, Nelson KE, Celentano DD, … Polk BF (1991). The ALIVE study, a longitudinal study of HIV-1 infection in intravenous drug users: description of methods and characteristics of participants. NIDA Research Monograph, 109, 75–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen LS, & Warren KE (2018). Combatting the opioid epidemic: Baltimore’s experience and lessons learned. Journal of Public Health (Oxford, England), 40(2), e107–e111. 10.1093/pubmed/fdx093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zibbell JE, Asher AK, Patel RC, Kupronis B, Iqbal K, Ward JW, & Holtzman D (2018). Increases in Acute Hepatitis C Virus Infection Related to a Growing Opioid Epidemic and Associated Injection Drug Use, United States, 2004 to 2014. American Journal of Public Health, 108(2), 175–181. 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zibbell JE, Hart-Malloy R, Barry J, Fan L, & Flanigan C (2014). Risk factors for HCV infection among young adults in rural New York who inject prescription opioid analgesics. American Journal of Public Health, 104(11), 2226–2232. 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlotorzynska M, Weidle PJ, Paz-Bailey G, Broz D, & NHBS Study Group. (2018). Factors associated with obtaining sterile syringes from pharmacies among persons who inject drugs in 20 US cities. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 62, 51–58. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.08.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.