Abstract

Objective

To investigate pathways by which interventions that promote shared reading and play help prevent child behavior problems. We examined whether family processes associated with the family investment pathway (eg, cognitive stimulation) and the family stress pathway (e.g., psychosocial functioning) mediated impacts of a pediatric-based preventive intervention on child behavior.

Study design

The sample included 362 low-income mothers and their children who participated in a randomized controlled trial of Video Interaction Project (VIP), a pediatric-based preventive intervention that promotes parent-child interactions in the context of shared reading and play. Parent-child dyads were randomly assigned to group at birth. Three mediators—parental cognitive stimulation, maternal stress about the parent-child relationship, and maternal depressive symptoms—were assessed at child ages 6 and 36 months. The outcome, child externalizing behaviors, was assessed at 36 months. We employed a series of path analytic models to examine how these family processes, separately or together, mediated impacts of VIP on child behavioral outcomes.

Results

Intervention impacts on child behavior were mediated by enhancements in cognitive stimulation and by improvements in mothers’ psychosocial functioning. A sequential mediation model showed that VIP impacts on cognitive stimulation at 6 months were associated with later reductions in mothers’ stress about the parent-child relationship, and that this pathway mediated intervention impacts on child behavioral outcomes at age 3 (P = .023).

Conclusions

Utilizing an experimental design, this study identifies pathways by which parentchild interactions in shared reading and play can improve child behavioral outcomes.

Trial registration

Keywords: preventive intervention, parenting, behavior problems, early childhood, poverty

Poverty-related disparities in school readiness emerge early in childhood and have long-term consequences for academic achievement.1 Although much of the literature on school readiness has focused on language and cognitive outcomes, there is growing recognition that social-emotional development is critical to children’s school adjustment and academic performance2. Two key perspectives have emerged to explain how poverty affects family processes that mediate disparities in child development. The “family stress model” emphasizes the effects of economic hardship on parental stress, which negatively affects the quality of parent-child relationships and children’s social-emotional development 3,4. Separately, the “family investment model” emphasizes how limitations in material resources affect parents’ provision of cognitive stimulation, with associated negative effects on children’s cognitive and language outcomes 5,6.

These 2 models have informed different approaches to addressing disparities in school readiness. Some interventions have focused on mitigating the impacts of poverty-related stress on families’ psychosocial functioning7, and others have focused on promoting parents’ provision of cognitive stimulation8. However, there is increasing recognition that these family processes are interrelated9,10. In particular, although activities like shared reading and play have typically been viewed as important for promoting cognitive and language outcomes, these activities may also encourage interactions that strengthen the parent-child relationship and support children’s social-emotional development 11–13. Indeed, some interventions for children with conduct problems (e.g., the Incredible Years) have used therapeutic play interactions, together with parent coaching in positive discipline strategies, as a strategy to reduce children’s behavior problems. However, there is limited study of whether primary prevention programs that focus on promoting shared reading and play in low-income families can also improve child behavioral outcomes, and of the degree to which these impacts are mediated by changes in families’ psychosocial functioning.

In the current study, we investigate pathways by which parenting interventions that promote cognitively stimulating activities like shared reading and play may improve child behavioral outcomes. We utilize longitudinal data from a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of the Video Interaction Project (VIP), a pediatric-based intervention that promotes parent-child interactions in shared reading and play, and which has shown reductions on child externalizing behaviors14,15. Our first hypothesis was that intervention impacts on child behavior would be mediated by family processes associated with the family investment pathway, in particular parents’ provision of cognitive stimulation. Our second hypothesis was that intervention impacts on child behavior would be mediated by family processes associated with the stress pathway, particularly mothers’ psychosocial functioning. Our third hypothesis was that investment and stress-related family processes would be interrelated and together would mediate intervention impacts on child behavior. Investigation of these pathways provides new insights into how intervention strategies that are typically studied in the context of language and cognitive development might have benefits for children’s behavioral outcomes, with broad implications for theory and policy.

METHOD

This is a longitudinal analysis of parent-child dyads enrolled in the Bellevue Project for Early Language, Literacy and Education Success (BELLE), a RCT of pediatric primary care interventions on parenting and child development. A single-blind, 3-way RCT was conducted at an urban public hospital serving low-income families (Bellevue Hospital Center). Consecutive enrollment of mother–child dyads occurred in the postpartum unit. After enrollment, parent–child dyads were assigned to 1 of 2 intervention groups (Video Interaction Project [VIP] or Building Blocks [BB]) or to a control group by using a random number generated by the project director in Microsoft Excel 2003 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA). Group assignments were concealed from staff and study participants until enrollment was completed. Approval was obtained from the New York University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board and the Bellevue Hospital Center Research Review Committee. The primary goal of this RCT was to investigate effects of VIP and BB on parenting, child development, and school readiness. The current paper reports secondary analyses of this RCT, examining mediating pathways of VIP impacts on child behavioral outcomes at 36 months.

Participants

Enrollment took place between November 2005 and October 200816. Consecutive mother-infant dyads who met inclusion criteria and provided informed consent were enrolled 1–2 days after birth. Inclusion criteria were plans to receive pediatric care at Bellevue, full-term birth, no significant medical complications or eligibility for Early Intervention, and a mother who was the primary caregiver, was over 18 years of age, spoke primarily English or Spanish, and had a telephone to maintain contact with the program. A total of 675 families were enrolled, 225 families per group, providing 80% power to detect a minimum effect size (ES) of 0.33 SD assuming 33.3% attrition by age 3 years. Owing to limited resources to conduct follow-up assessments, BB was assessed only through 24 months; thus, the current analysis includes only participants in the VIP and Control groups.

Intervention Group: The Video Interaction Project

VIP was developed as an enhancement to Reach Out and Read (ROR), a program that promotes parent-child reading aloud at pediatric well-child visits and that has had wide dissemination and evidence of impacts17. VIP sessions add an interventionist who meets with families one-on-one for approximately 25–30 minutes on the same day as regularly scheduled well-child visits, with 14 VIP sessions between birth and age 3 years.. The interventionist video-records parent-child dyads during 5-minute play and shared reading episodes utilizing a developmentally appropriate toy and/or book provided by the program, and which families take home. The video is reviewed by the interventionist and parent together to identify and reinforce strengths in the interaction and promote parent self-reflection, and is given to the parent to take home to promote generalization of identified responsive behaviors. Messages are further emphasized through personalized pamphlets that provide suggestions related to responsive parenting during play, reading and daily routines and facilitate parent development of individualized goals for engaging the child. Interventionists typically have bachelor’s degrees in fields related to child development and receive training and supervision by developmental psychologists.

Control Group

Control families received standard pediatric care, including all anticipatory guidance and observation of developmental milestones. Standard pediatric care included ROR for all groups.

Measures

All measures were collected by research assistants blind to group assignment during in-person visits that took place in a research space at Bellevue Hospital Center. Child externalizing behaviors, the outcome variable, was assessed at 36 months (the end of the intervention period). Mediators included parental cognitive stimulation and parent’s psychosocial functioning, assessed through 2 measures, mothers’ stress about the parent-child relationship and) maternal depressive symptoms. All mediators were assessed when children were 6 months (6-months after the start of the intervention) and again at 36 months.

Child Behavioral Outcomes

Parents reported on their child’s behavioral problems at 36 months using four subscales from the Parent Rating Scales of the Behavior Assessment System for Children–Second Edition (BASC-218). The BASC-2 has been normed for use in English and Spanish. It was administered in interview format in the parent’s preferred language by trained research assistants blind to group assignment. T scores (mean ± SD: 50 ± 10) were calculated for each subscale, with higher T scores reflecting a greater degree of behavioral problems. The current analysis examines Externalizing Behaviors, a composite of the Hyperactivity and Aggression subscales, which has been shown in previous studies to be reduced by the VIP intervention 14,15.

Cognitive Stimulation

Cognitive stimulation was assessed via parent interview using the StimQ2 19, a structured interview assessing parents’ provision of cognitive stimulation in the home. It has been validated for use in low SES populations in English and Spanish, and found to have high concurrent validity with the HOME Inventory20. It consists of four subscales: (1) Availability of Learning Materials (ALM) assesses the type and variety of toys in the home; (2) Reading (READ) assesses the quantity and quality of parent-child reading activities; (3) Parental Involvement in Developmental Advance (PIDA) assesses parent-child engagement in teaching and play activities; and (4) Parental Verbal Responsivity (PVR) assesses the quantity and quality of parent-child verbal interactions. These four subscales were summed to obtain a total score. The StimQ-I2 (developed for use with infants 5–12 months) was used at 6 months and the StimQ-P2 (developed for preschoolers 36–72 months) was used at 36 months.

Stress about the Parent-child Relationship

Mothers’ stress about the parent-child relationship was assessed using the Parent-Child Dysfunctional Interaction (P-CDI) subscale of the Parenting Stress Index-Short Form 21. The P-CDI consists of 12 items that measure parents’ perceptions of dysfunction in their relationship with their child. Total P-CDI scale scores range from 12 to 60, with higher scores reflecting more negative feelings about the parent-child relationship; P-CDI scores were converted to percentile scores and log transformed due to non-normal (Kolmogorov–Smirnov 6 months: Z = 3.53, p<.001, 36 months: Z=2.29, p<.001), positively skewed distribution (6 months: skewness = 1.09, SE = 0.15; 36 months: skewness = .41, SE = 0.14).

Depressive Symptoms

At the six-month assessment, maternal depressive symptoms were assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), a screening instrument based on nine questions that assess depressed mood during the prior 2 weeks 22. Examples include “little interest or pleasure in doing things” and “feeling tired or having little energy.” Each question is scored from 0 to 3, with total scores ranging from 0 to 27 and higher scores representing greater frequency of symptoms. It has been validated in Spanish 23.

At 36 months, maternal depressive symptoms were assessed using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D24). The CES-D is a 20-item measure that asks caregivers how often during the past week they experienced symptoms associated with depression (e.g., restless sleep, poor appetite, feeling lonely). Each item is scored from 0 to 3, with total scores ranging from 0 to 60 and higher scores representing greater depressive symptoms. The CES-D has been validated in Spanish 25.

Socio-demographic Characteristics

Information on socio-demographic characteristics was collected during the postpartum period and when infants were 6 months of age through interviews with the mother. This included data on maternal age, ethnicity, education, literacy, country of origin, marital status, and primary language, as well as child sex and birth order. Families were classified into lower (Hollingshead groups IV and V) or higher socioeconomic strata (Hollingshead groups I-III) based on the Hollingshead Four Factor Index. Families were classified as being at increased psychosocial risk if the mother reported one or more of the following: being a victim of violence, homelessness, involvement with child protective services, significant financial hardship, food insecurity, cigarette smoking or alcohol use during pregnancy, and history of previous mental illness.

Statistical Analyses

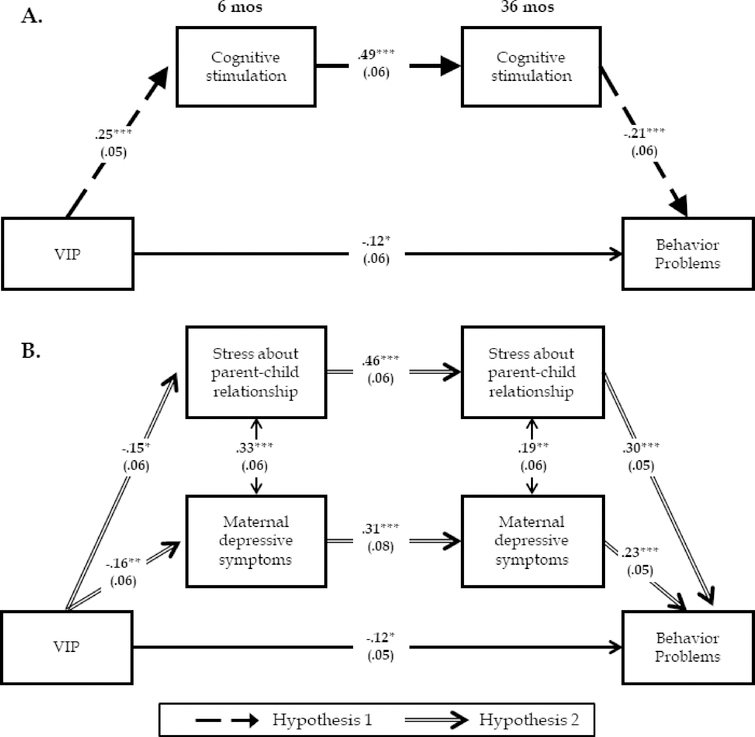

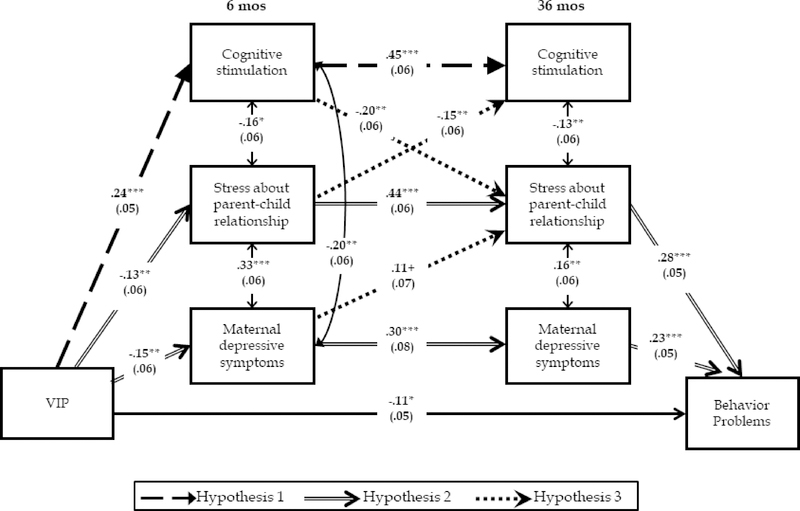

The theoretical model for analyses is presented in Figure 2. We tested our main hypotheses using a series of path analytic models using the Structural Equation Model (SEM) module in Stata SE 12 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX). We used Full Information Maximum Likelihood estimation, a method that accommodates missing data by estimating each parameter using all available data for that specific parameter. Model 1 assessed mediation via parental cognitive stimulation only (Hypothesis 1); Model 2 assessed mediation via parents’ psychosocial functioning only (Hypothesis 2); Model 3 assessed mediation via parental cognitive stimulation and psychosocial functioning, taking into account interrelations between different family processes (Hypothesis 3); this model included covariation between the three sets of mediators within each timepoint as well as six paths from each of the 6-month mediators to each of the 36-month mediators. All analyses modeled continuity of the same mediator between 6 and 36 months and adjusted for socio-demographic characteristics.

Figure 2.

Theoretical model and hypotheses.

To evaluate acceptable fit of the models, we used the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). Based on McDonald & Ho (2002), values of ≥.90 for CFI and ≤.08 for RMSEA indicate adequate model fit26. For each model, we assessed the significance of all direct and indirect effects using the estat teffects command in Stata. Direct effects measure the effect of the independent variable (VIP) on child behavior when the mediators are held constant, and indirect effects measure the extent to which child behavior changes in relation to the mediators when the independent variable is held constant. The proportion of the VIP effect that was mediated was computed by dividing the indirect effect of VIP on child behavior by the total effect of VIP on child behavior.

We employed sequential mediation analysis to examine longitudinal pathways that mediated VIP effects on child behavior. This method, also referred to as a “serial multiple mediator model”, allows estimation of multiple meditators that are serially linked in a chain 27, enabling examination of the full chain within the same model. The significance of each pathway was estimated by dividing the mediated effect size by its standard error (see formulas in MacKinnon & Dwyer, 199328) using the ‘nonlinear combination of estimators’ (nlcom) function in Stata. Consistent with current recommendations, the significance of the indirect effect (a × b × c [see below and Table II) is used as the measure of mediation.

Table 2.

Significance of mediated effects in each of the three path models.

| a | b | c | Mediated effect a × b × c | Z | Proportion of VIP effect mediated | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | |||||||

| Total mediated effecta | −0.55 (.20) | −2.71** | 18% | ||||

| VIP → CS 6m → CS 36m → Behavior | 3.45 | 0.58 | −0.27 | −0.55 (.20) | −2.71** | ||

| Model 2 | |||||||

| Total mediated effecta | −0.83 (.29) | −2.86** | 25% | ||||

| VIP → PCR 6m → PCR 36m → Behavior | −0.29 | 0.46 | 3.11 | −0.42 (.19) | −2.19* | ||

| VIP → MDS 6m → MDS 36m → Behavior | −1.25 | 0.70 | 0.27 | −0.24 (.12) | −2.04* | ||

| Model 3 | |||||||

| Total mediated effecta | −1.29 (.37) | −3.49*** | 35% | ||||

| Individual variable pathways | |||||||

| VIP → CS 6m → CS 36m → Behavior | 3.28 | 0.53 | −0.10 | −0.17 (.14) | −1.25 | ||

| VIP → PCR 6m → PCR 36m → Behavior | −0.27 | 0.44 | 2.89 | −0.34 (.17) | −2.00* | ||

| VIP → MDS 6m → MDS 36m → Behavior | −1.18 | 0.69 | 0.26 | −0.21 (.11) | −1.94+ | ||

| Interrelated variables pathways | |||||||

| VIP → CS 6m → PCR 36m → Behavior | 3.28 | −0.03 | 2.89 | −0.27 (.12) | −2.27* | ||

| VIP → CS 6m → MDS 36m → Behavior | 3.28 | −0.13 | 0.26 | −0.11 (.10) | −1.12 | ||

| VIP → PCR 6m → CS 36m → Behavior | −0.27 | −1.23 | −0.10 | −0.03 (.03) | −1.04 | ||

| VIP → PCR 6m → MDS 36m → Behavior | −0.27 | 0.46 | 0.26 | −0.03 (.05) | −0.62 | ||

| VIP → MDS 6m → CS 36m → Behavior | −1.18 | −0.15 | −0.10 | −0.02 (.02) | −0.79 | ||

| VIP → MDS 6m → PCR 36m → Behavior | −1.18 | 0.03 | 2.89 | −0.10 (.07) | −1.36 |

Includes all paths in the model

Note: M, Mediator; 6m, 6 months; 36m, 36 months; CS, Cognitive Stimulation; PCR, Stress about the Parent-Child Relationship; MDS, Maternal Depressive Symptoms. Unstandardized coefficients are presented for each path, from VIP to the 6-mo mediator (a), from the 6-mo mediator to the 36-mo mediator (b), and from the 36-mo mediator to child behavior (c). The mediated effect (standard error in parentheses) represents the indirect effect of VIP on child behavior through the 6- and 36-month mediators.

p <.10

p <.05

p <.01

p <.001

RESULTS

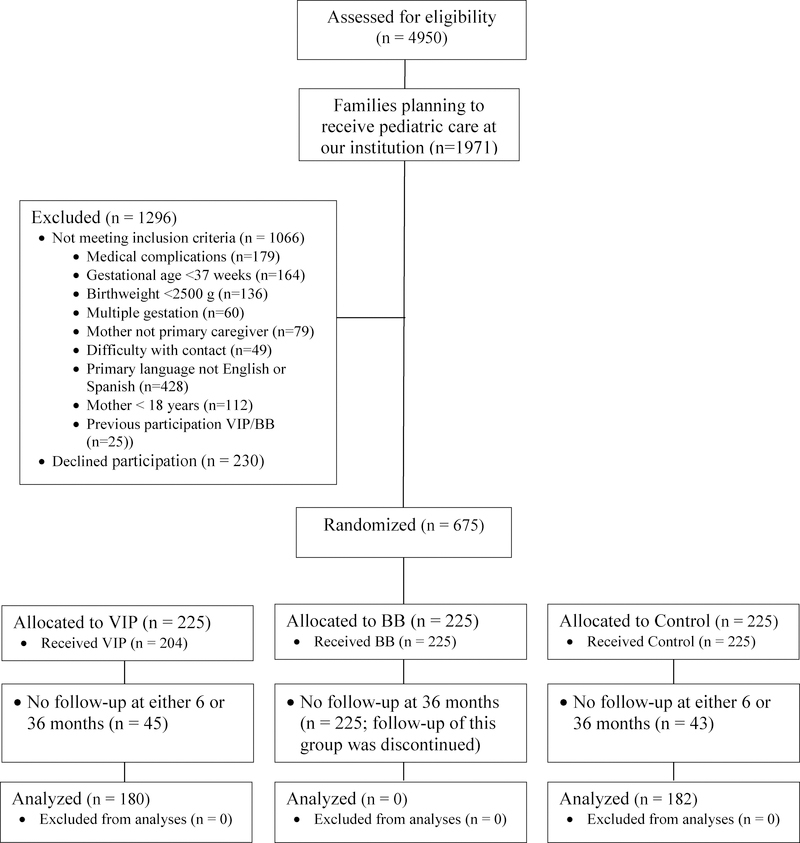

Participants included 362 of 450 mother-infant dyads in the VIP or Control group (80%) who were assessed at the 6-month and/or 36-month assessments (Figure 1 [available at www.jpeds.com], participant flowchart). Mean child age in months was: 6.9 (1.3) at the 6-month assessment and 39.2 (3.8) at the 36-month assessment. Table 1 (available at www.jpeds.com) shows sociodemographic characteristics by group for those participants with data collected during at least one follow-up assessment point. Participants were primarily Latino immigrant families who virtually all had low SES, with approximately one-third who were considered at greater risk due to exposure to one or more psychosocial risk factors.

Figure 1,

online only. Participant flowchart.

Table 1.

Baseline socio-demographic characteristics of families in the analytic sample.

| All families (N = 362) | VIP (N = 180) | Control (N = 182) | pb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mother <Age 21 | 10% | 10% | 11% | .89 |

| Mother Hispanic/Latina | 93% | 94% | 93% | .86 |

| Mother born outside US | 88% | 90% | 85% | .22 |

| Mother primarily Spanish-speaking | 83% | 82% | 83% | .96 |

| Mother non high school grad | 62% | 62% | 61% | .89 |

| Low maternal literacy (<9th grade) | 29% | 34% | 25% | .07 |

| Low SES | 92% | 92% | 92% | .99 |

| High psychosocial risk | 33% | 36% | 30% | .28 |

| Female child | 52% | 54% | 50% | .46 |

| First born child | 41% | 43% | 39% | .47 |

Analytic sample includes all families contributing data at one or more of the follow-up time points.

p-value for Chi-Square tests comparing VIP and Control.

Dyads who contributed data for at least one assessment point did not significantly differ from those who did not contribute data on maternal age, marital status, presence of one or more additional psychosocial risks, child birth order, or child sex. However, mothers contributing data were more likely than those not contributing data to: speak Spanish as their primary language (p<.001), self-identify as Latina (p<.001), be immigrants to the US (p<.01), have low education and literacy (p<.01), and be low SES (p<.1). Importantly, there were no differences in sociodemographic characteristics by randomization group at enrollment16 either for the full sample or for participants analyzed in the current study (Table 1).

Direct Effect of the VIP Intervention on Child Behavior

Impacts of VIP on the mediators and outcomes included here have been previously reported14–16,29–31. To verify the effect of VIP on child behavior after adjusting for covariates, a direct effects model estimated the direct path between VIP and externalizing problems while controlling for the effects of all covariates. Consistent with prior analyses, there was a significant effect of VIP on child externalizing problems at 36 months (β = −0.140, p = .013).

Mediation Models

Figure 3 and Figure 4 show results of the path analyses (SEM) for each of the three models. In the figures and in the text below, we report standardized coefficients for each path; these coefficients represent the strength of the relationship between variables in standard deviation units (i.e., for every standard deviation unit increase in one variable [e.g., cognitive stimulation], the succeeding variable [e.g., child externalizing behavior] increases or decreases by that number of standard deviation units). The larger the coefficient is in absolute value, the stronger the relationship between the variables (while adjusting for other variables in the model); the closer the coefficient is to 0, the weaker the relationship. In addition, Table 2 shows results from the sequential mediation analysis (see above) for all models, including unstandardized coefficients for each path (from VIP to the 6-month mediator [a], from the 6-month mediator to the 36-month mediator [b], and from the 36-month mediator to child behavior [c]). The coefficient for the mediated effect (a × b × c) represents the indirect effect of VIP on child behavior through the 6-and 36-month mediators sequentially; the z-score indicates whether the entire sequential pathway met criteria for significant mediation, suggesting that some of VIP’s effect on child behavior is accounted for by that pathway. Table 2 also shows the proportion of the VIP effect that was mediated by all paths included in each model.

Figure 3.

Path modeling showing the effects of VIP on children’s behavioral outcomes at 36 months, as mediated by A) cognitive stimulation, or B) parent psychosocial functioning. Standardized coefficients (standard errors) are shown for all modeled pathways. *p <.05, **p <.01, ***p <.001

Figure 4.

Path modeling showing the effects of VIP on children’s behavioral outcomes at 36 months, as mediated by cognitive stimulation, parent psychosocial functioning and their interrelations. Standardized coefficients (standard errors) are shown for all pathways with p<.1. +p <.10, *p <.05, **p <.01, ***p <.001

Cognitive Stimulation Model

Model 1 (Figure 3, A) tested whether parents’ provision of cognitive stimulation at 6 and 36 months mediated VIP impacts on child behavior. This model (CFI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.05) revealed a significant effect of VIP predicting higher cognitive stimulation at 6 months (β = 0.25, p < .001), longitudinal stability in cognitive stimulation between 6 and 36 months (β = 0.49, p < .001), and a significant link between 36-month cognitive stimulation and child behavior (β = −0.21, p < .001). As shown in Table 2, sequential mediation analysis (VIP→ cognitive stimulation [6 months] → cognitive stimulation [36 months] → Child behavior) revealed a significant indirect effect of VIP on child behavior (estimate = −.55, SE = .20, p = .007), indicating mediation was significant. After inclusion of the mediators, VIP continued to predict child behavior (β = −0.12, p = .03), suggesting partial mediation. The mediating pathway explained 18% of the total effect of VIP on child behavior.

Parental Stress Model

Model 2 (Figure 3, B) tested whether 2 mediators associated with parents’ psychosocial functioning – maternal stress about the parent-child relationship and maternal depressive symptoms – mediated VIP impacts on child behavior. This model (CFI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.046) revealed a significant effect of VIP on maternal stress about the parent-child relationship (β = −0.15, p = .012) and on maternal depressive symptoms (β = −0.16, p = .007) at 6 months, longitudinal stability in each of the mediators between 6 and 36 months (parenting stress: β = 0.46, p < .001; maternal depression: β = 0.31, p < .001), and significant paths between the 36-month mediators and child behavior (parenting stress: β = 0.30, p < .001; maternal depression: β = 0.23, p < .001). The indirect effect of VIP on child behavior via these mediators was significant (estimate = −.83, SE = .29, p = .004), and explained 25% of the total effect of VIP on child behavior. Sequential mediation analyses revealed that each of these pathways was significant: 1) VIP→ Parenting stress [6 months] → Parenting stress [36 months] → Child behavior (estimate = −.42, SE = .19, p = .03); 2) VIP→ Maternal depressive symptoms [6 months] → Maternal depressive symptoms [36 months] → Child behavior (estimate = −.24, SE = .12, p = .04; Table 2). After inclusion of the mediating pathways, VIP continued to predict child behavior (β = −0.12, p = .02), indicating partial mediation.

Interplay between Parental Cognitive Stimulation and Psychosocial Functioning

Model 3 (Figure 4) tested whether cross-time interrelations between parental cognitive stimulation and psychosocial functioning helped explain VIP impacts on child behavior. This model (CFI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.053) showed significant cross-time relationships between some, but not all, mediators. Higher levels of cognitive stimulation at 6 months predicted lower maternal stress about the parent-child relationship at 36 months; conversely, higher levels of maternal stress about parent-child relationship at 6 months predicted lower cognitive stimulation at 36 months. In contrast, maternal depressive symptoms were not significantly related to preceding or subsequent cognitive stimulation; nor was maternal depression associated with preceding or subsequent stress about the parent-child relationship, although this latter relationship approached significance; β = 0.11, p = .092.

Collectively, the indirect effect of VIP on child behavior via these mediators was significant (estimate = −1.29, SE = .37, p < .001) and explained 35% of the total effect of VIP on child behavior. Two of the sequential meditation pathways were significant (Table 2): 1) VIP→ Parenting stress [6 months] → Parenting stress [36 months] → Child behavior (estimate = −.34, SE = .17, p = .046), and 2) VIP→ Cognitive stimulation [6 months] → Parenting stress [36 months] → Child behavior (estimate = −.27, SE = .12, p = .023). The indirect pathway from VIP to maternal depressive symptoms at 6 months to maternal depressive symptoms at 36 months to child behavior approached significance (estimate = −21, SE = .11, p = .052). The indirect pathway involving only cognitive stimulation was not significant (estimate = −.17, SE = .14, p = .21). After inclusion of the mediating pathways, VIP continued to predict child behavior (β = −0.11, p = .027), indicating partial mediation.

DISCUSSION

The current study advances our understanding of the mechanisms by which pediatric primary care interventions that promote reading aloud and play can help prevent child behavior problems. VIP, a preventive intervention that supports parent-child interactions in the context of shared reading and play, led to improved child behavioral outcomes that were mediated by enhancements in parental cognitive stimulation and psychosocial functioning. In particular, VIP impacts on parents’ provision of cognitive stimulation in infancy was associated with later reductions in mothers’ stress about the parent-child relationship and, together, these changes mediated intervention impacts on child behavioral outcomes at age 3. The mediation models explain between 18–35% of VIP’s effect on child behavior. VIP’s effect on child behavior has been reported to be 0.25 SD, a modest effect size that is comparable with those of other, higher intensity, interventions and likely to be associated with clinically important individual and population-level effects14, and model 3 accounts for õne-third of this effect.

Findings show that enhancements in parents’ provision of cognitive stimulation at 6 months had cascading benefits on mothers’ psychosocial functioning at 36 months, suggesting that parent-child engagement in cognitively stimulating activities may bring about improvements in the parent-child relationship that reduce parental stress. Conversely, reductions in parental stress about the parent-child relationship at 6 months had cascading benefits for cognitive stimulation at 36 months, suggesting that as parents feel more enjoyment of the parent-child relationship they may seek out more opportunities to engage with their child in cognitively stimulating activities. Together, these findings suggest that the effects of early parenting interventions may be sustained over time via longitudinal continuity in individual family processes as well as interrelations between different family processes that potentiate each other over time. It is also possible that this occurs in part through transactional processes, with enhancements in the parent-child relationship contributing to improvements in child behavior and vice versa.

These findings suggest a potential link between strategies for promoting cognitive-language development and those for preventing child behavior problems: namely, parent-child engagement in shared reading and play. Although there is broad recognition that reading and play are potent contexts for facilitating aspects of parent-child interactions that contribute to language and cognitive development32,33, less research has examined how these activities support social-emotional development beginning in infancy. Prior work examining contributions of reading and play to children’s social-emotional development has focused on how these activities support the development of children’s self-regulatory capacities (e.g., executive function, emotion regulation), especially in children preschool-aged and older 34–36. A small number of studies also suggest that engagement in shared reading is associated with parent-child bonding and secure attachment13,37,38. The current study adds evidence from a RCT suggesting that parent-child interactions in shared reading and play can improve behavioral outcomes in young children by improving the parent-child relationship.

As a pediatric primary care-based program, VIP is relatively low cost (e.g., ~1/10th the cost of many home visiting programs39) and provides opportunities for complementing home visiting (e.g., addressing what is directly observed in families’ homes), with potential for wide reach. Indeed, new models are being developed to study how programs like VIP can work synergistically with home visiting within a public health model of prevention. For example, in Smart Beginnings40, VIP is delivered universally to all low-income families through pediatric primary care, and higher intensity services (Family Check Up41) are delivered to higher risk families through home visiting. Scaling of such programs requires capacity to integrate an interventionist into the pediatric primary care team. A number of local and national initiatives (e.g., City’s First Readers42, Bridging the Word Gap8) are currently in progress that seek to implement parenting programs in pediatric primary care, including ROR, VIP, and Healthy Steps, and may demonstrate their scalability.

Findings from this study provide not only direct support for VIP but also indirect support for other primary care programs that enhance parent-child interactions in the context of shared reading and play, by demonstrating that engagement in these activities may have cascading effects on parent psychosocial functioning and child behavior. VIP begins at the first well-child visit and has impacts as early as 6 months that have cascading consequences for the parent-child relationship and child behavior outcomes at age 3. Although ROR has traditionally started at 6 months of age, there have been recent initiatives to begin ROR at birth, and findings from this study support these initiatives.

This study has important methodological strengths, which include use of a longitudinal prospective RCT following a cohort of low-income families from birth through early childhood. The study also has several limitations. First, our measures relied exclusively on parent report and, although we used measures that have been shown to be reliable and valid, these measures can nonetheless be subject to recall and social desirability biases. Future research should try to incorporate observational measures of parenting behaviors, as well as teacher, clinician, or examiner reports of child behavior. Second, although we assessed mothers’ feelings of stress about the parent-child relationship, we did not assess the parent-child relationship directly. Future research could expand the present findings by including additional measures of parent-child relationship quality. Third, participating mothers were primarily first-generation Hispanic/Latino immigrants and the analytic sample was slightly less advantaged than the enrolled sample; although, importantly, this did not differ by treatment and control. Thus, these results may not be generalizable to families with other sociodemographic characteristics. Finally, although the effects of VIP on parenting outcomes and child behavior are causal, it is possible there could be additional mediators accounting for the relationships found in this study. In addition, although overall analyses were conducted utilizing data collected longitudinally, assessments of the mediators at 36 months were performed concurrently with assessments of child behavior, limiting our capacity for causal inference.

Family processes associated with both the investment and stress pathways contribute to children’s behavioral outcomes, either directly, as in the case of parenting stress and maternal depression, or indirectly, as in the case of cognitive stimulation. In addition, enhancements in parent-child interactions in infancy are carried forward via continuity in individual family processes as well as potentiation among different family processes over time. Together, these findings support a conceptualization of relational health in which cognitively stimulating activities and positive parent-child relationships are mutually supportive and, together, enhance parent and child psychosocial functioning.

These findings have important implications for policies seeking to address poverty-related disparities in school readiness. First, they suggest that programs that target the family investment or stress pathways are not only complementary but are also likely to be interdependent. As such, policies capitalizing on synergies between these pathways may have greater potential to enhance impacts for children living in poverty. Second, they underscore the importance of promoting positive parent-child interactions starting early in infancy. Finally, they highlight the role of pediatric primary care in universal promotion of child development across domains. In particular, findings suggest that primary care preventive interventions that promote parent-child interactions in the context of shared reading and play (e.g., VIP, ROR) have the potential to enhance parent-child psychosocial functioning, in addition to early language and literacy, and thus help reduce poverty-related disparities in school readiness.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01 HD047740 [to A.M.]); the Tiger Foundation; the Marks Family Foundations; Children of Bellevue, Inc; KiDS of NYU Foundations, Inc; the Rhodebeck Charitable Trust; and an Institutional National Research Service Award from the Health Resources and Services Administration (T32 HD047740 [to A.W.]). The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shonkoff JP, Garner AS, The Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health, Committee on Early Childhood, Adoption, and Dependent Care, and Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, Siegel BS, Dobbins MI, et al. The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e232–e246. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rimm-Kaufman SE, Pianta RC. An ecological perspective on the transition to kindergarten: a theoretical framework to guide empirical research. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2000;21:491–511. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conger RD, Conger KJ, Elder GH, Lorenz FO, Simons RL, Whitbeck LB. A family process model of economic hardship and adjustment of early adolescent boys. Child Dev. 1992;63:526–541. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1600820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mcloyd VC. The impact of economic hardship on Black families and children: psychological distress, parenting, and socioemotional development. Child Dev. 1990;61:311–346. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2188806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradley RH, Corwyn RF, McAdoo HP, Coll CG. The home environments of children in the United States part I: variations by age, ethnicity, and poverty status. Child Dev. 2001;72:1844–1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foster EM. How economists think about family resources and child development. Child Dev. 2002;73:1904–1914. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blair C, Raver CC. Poverty, stress, and brain development: new directions for prevention and intervention. Acad Pediatr. 2016;16(3 Suppl):S30–6. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2016.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greenwood CR, Carta JJ, Walker D, Watson-Thompson J, Gilkerson J, Larson AL, et al. Conceptualizing a public health prevention intervention for bridging the 30 Million Word Gap. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2017;20:1–22. doi: 10.1007/s10567-017-0223-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yeung WJ, Linver MR, Brooks-Gunn J. How money matters for young children’s development: parental investment and family processes. Child Dev. 2002;73:1861–1879. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3696422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weisleder A, Marchman VA. How socioeconomic differences in early language environments shape children’s language development In: Bar-On A, Ravid D, eds. Handbook of Communication Disorders: Theoretical, Empirical, and Applied Linguistics. De Gruyter; 2018:545–564. doi: 10.1515/9781614514909-027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xie Q-W, Chan CHY, Ji Q, Chan CLW. Psychosocial effects of parent-child book reading interventions: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2018;141:e20172675. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Webster-Stratton C, Reid MJ. Parents,teachers and therapists using the child-directed play therapy and coaching skills to promote children’s social and emotional competence and to build positive relationships In: Schaefer CE, ed. Play Therapy for Preschool Children. Washington, DC; 2009:245–273. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Milteer RM, Ginsburg KR, Mulligan DA. The importance of play in promoting healthy child development and maintaining strong parent-child bond: focus on children in poverty. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e204–e213. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weisleder A, Cates CB, Dreyer BP, Johnson SB, Huberman HS, Seery AM, et al. Promotion of positive parenting and prevention of socioemotional disparities. Pediatrics. 2016;137:e20153239. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mendelsohn AL, Cates CB, Weisleder A, Johnson SB, Seery AM, Canfield CF, et al. Reading aloud, play, and social-emotional development. Pediatrics. 2018;141:e20173393. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mendelsohn AL, Huberman HS, Berkule SB, Brockmeyer CA, Morrow LM, Dreyer BP. Primary care strategies for promoting parent-child interactions and school readiness in at-risk families: The Bellevue Project for Early Language, Literacy, and Education Success. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165:33–41. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zuckerman B Promoting early literacy in pediatric practice: twenty years of Reach Out and Read. Pediatrics. 2009;124:1660–1665. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reynolds C, Kamphaus R. BASC-2: Behavior Assessment System for Children. 2004. https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&q=behavior+assessment+system+for+children&btnG=&as_sdt=1%2C33&as_sdtp=#4. Accessed June 9, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mendelsohn AL, Cates CB, Tamis-LeMonda CS, Dreyer BP. StimQ Cognitive Home Environment [Internet]. http://www.med.nyu.edu/pediatrics/developmental/research/belle-project/stimq-cognitive-home-environment.

- 20.Dreyer BP, Mendelsohn AL, Tamis-LeMonda CS. Assessing the child’s cognitive home environment through parental report: reliability and validity. Early Dev Parent. 1996;5:271–287. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abidin RR. The Parenting Stress Index: a measure of the parent–child system In: Zalaquett CP, Woods RJ, eds. Evaluating Stress. Lathan, MD: University Press of America; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kroenke K, Spitzer R, Williams J. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diez-Quevedo C, Rangil T, Sanchez-Planell L, Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. Validation and utility of the Patient Health Questionnaire in diagnosing mental disorders in 1003 general hospital Spanish inpatients. Psychosom Med. 2001;63:679–686. http://journals.lww.com/psychosomaticmedicine/Abstract/2001/07000/Validation_and_Utility_of_the_Patient_Health.21.aspx. Accessed September 5, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruiz-Grosso P, Loret de Mola C, Vega-Dienstmaier JM, Arevalo JM, Chavez K, Vilela A, et al. Validation of the Spanish Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression and Zung Self-Rating Depression Scales: a comparative validation study. Fontenelle L, ed. PLoS One. 2012;7:e45413. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McDonald RPP, Ho M-HRR. Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychol Methods. 2002;7:64–82. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press; 2013. http://www.guilford.com/p/hayes3. [Google Scholar]

- 28.MacKinnon DP, Dwyer JH. Estimating mediated effects in prevention studies. Eval Rev. 1993;17:144–158. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berkule SB, Cates CB, Dreyer BP, Huberman HS, Arevalo J, Burtchen N, et al. Reducing maternal depressive symptoms through promotion of parenting in pediatric primary care. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2014;53:460–469. doi: 10.1177/0009922814528033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cates CB, Weisleder A, Dreyer BP, Johnson SB, Vlahovicova K, Ledesma J, et al. Leveraging healthcare to promote responsive parenting: impacts of the Video Interaction Project on parenting stress. J Child Fam Stud. 2016;25:827–835. doi: 10.1007/s10826-015-0267-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cates CB, Weisleder A, Johnson SB, Seery AM, Canfield CF, Huberman H, et al. Enhancing parent talk, reading, and play in primary care: sustained impacts of the Video Interaction Project. J Pediatr. 2018;199:49–56.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tamis-LeMonda CS, Bornstein MH. Specificity in mother-toddler language-play relations across the second year. 1994;30:283–292. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dickinson DK, Griffith JA, Golinkoff RM, Hirsh-Pasek K. How reading books fosters language development around the world. Child Dev Res. 2012;2012:1–15. doi: 10.1155/2012/602807 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singer DG, Golinkoff RM, Hirsh-Pasek K. Play = learning: how play motivates and enhances children’s cognitive and social-emotional growth. Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berk L, Mann T, Ogan A. Make-believe play: wellspring for development of self-regulation. In: Play= learning: how play motivates and enhances children’s cognitive and social-emotional growth. 2006:74–100. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=9EaIvUQziRgC&oi=fnd&pg=PA74&ots=Q9KqYmmMS1&sig=2kNkV1dXJ2Sc9EELESlLzMgqP4Y. Accessed March 14, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vygotsky LS. Play and its role in the mental development of the child In: Bruner JS, Jolly A, Sylva K, eds. Play, its role in development and evolution. New York: Penguin; 1976:537–554. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lariviere J, Rennick JE. Parent picture-book reading to infants in the neonatal intensive care unit as an intervention supporting parent-infant interaction and later book reading. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2011;32:146–152. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e318203e3a1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bus AG, van Ijzendoorn MH. Affective dimension of mother-infant picturebook reading. J Sch Psychol. 1997;35:47–60. doi: 10.1016/S0022-4405(96)00030-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cates CB, Weisleder A, Mendelsohn AL. Mitigating the effects of family poverty on early child development through parenting interventions in primary care. Acad Pediatr. 2016;16:S112–S120. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2015.12.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smart Beginnings. https://steinhardt.nyu.edu/ihdsc/smart

- 41.Shaw DS, Dishion TJ, Supplee L, Gardner F, Arnds K. Randomized trial of a family-centered approach to the prevention of early conduct problems: 2-year effects of the Family Check-Up in early childhood. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74:1–9. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.1.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Canfield CF, Seery AM, Weisleder A, Workman C, Cates CB, Roby E, et al. Encouraging parent–child book sharing: potential additive benefits of literacy promotion in health care and the community. Early Child Res Q. 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2018.11.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.