Abstract

Objective:

To determine the impact of damaging genetic variation in pro-angiogenic pathways on placental function, complications of pregnancy, fetal growth and clinical outcomes in pregnancies with fetal CHD.

Study design:

Families delivering a baby with a CHD requiring surgical repair in infancy were recruited. The placenta and neonate were weighed and measured. Hemodynamic variables were recorded from a third trimester (36.4 +/− 1.7 weeks) fetal echocardiogram. Exome sequencing was performed on the probands (N=133) and consented parents (114 parent-child trios, and 15 parent-child duos) and the GeneVetter analysis tool used to identify damaging coding sequence variants in 163 genes associated with the positive regulation of angiogenesis (PRA) (GO:0045766).

Results:

117 damaging variants were identified in PRA genes in 133 CHD probands with 73 subjects having at least one variant. Presence of a damaging PRA variant was associated with increased umbilical artery pulsatility index (mean 1.11 with variant vs. 1.00 without; P = .01). The presence of a damaging PRA variant was also associated with lower neonatal length and head circumference for age z-score at birth (mean −0.44 and −0.47 with variant vs 0.23 and −0.05 without; P=0.01 and 0.04, respectively). During median 3.1 years (interquartile range 2.0–4.1 years) of follow-up, deaths occurred in 2/60 (3.3%) subjects with no PRA variant and in 9/73 (12.3%) subjects with 1 or more PRA variants (P=0.06).

Conclusion:

Damaging variants in pro-angiogenic genes may impact placental function and are associated with impaired fetal growth in pregnancies involving a fetus with CHD.

Despite dramatic improvements in surgical outcomes, early mortality for complex congenital heart defects remains as high as 20% for some defects with greater than one-third of infants experiencing a major complication and prolonged hospitalization (1). Improvement in outcomes depends on identifying risk determinants and developing treatment strategies to mitigate those risks. Previous studies have identified premature birth, age and weight at the time of surgery, pre-operative comorbidities, the presence of a genetic syndrome and operative complexity as risk factors for adverse outcomes after surgery for CHD (2). These risk factors, however, only account for approximately 30% of between-patient differences in mortality (1). Therefore, there remains a critical need to identify as yet unrecognized factors that impact morbidity and mortality to improve pre-operative risk assessment and develop appropriate therapeutic strategies.

One emerging risk factor for adverse clinical outcomes in infants with critical congenital heart defects is the effect of impaired placental function and pregnancy complications. Prior studies have determined that pregnancies involving a fetus with CHD are at a higher risk of complications (including gestational hypertension (with or without pre-eclampsia), and pre-term and small for gestational age births) (3, 4) and that these complications lead to worse outcomes after cardiac surgery in infancy (5). The effect of fetal CHD on pregnancy complications is likely due at least in part to abnormal placental vascular development and function caused by the alterations in vascular flow dynamics and tissue oxygen delivery resulting from the cardiac defect (6). However, not all pregnancies involving a fetus with critical CHD have complications suggesting that modifying factors have an important role.

Based on previous studies noting the effects of genetic variation on the incidence of pregnancy complications (7, 8) and the contribution of genetic variation in vascular signaling pathways on clinical outcomes in infants with CHD (9, 10), we anticipated that genetic variants in the fetus, and potentially the mother, that affect vascular development would modify the effects of fetal CHD on placental function and on fetal growth and development. Specifically, we hypothesized that the presence of genetic variants that compromise angiogenesis would impair in utero hemodynamics, prenatal growth and development and clinical outcomes in patients with CHD requiring surgery in infancy. Therefore, in this study, we examined the effects of damaging genetic variants in an annotated set of genes determined to promote angiogenesis. The gene set “positive regulation of angiogenesis” (PRA) (Gene Ontology database: GO:0045766) was selected for the analysis because it met the following criteria it contained genes critical to angiogenesis, it contained only positive regulators thereby enhancing the likelihood that a “damaging” variant would reduce protein function and therefore reduce angiogenic signaling, and the number of genes and variant frequency in the gene set yielded sufficient numbers of subjects with and without variants to allow for a robust comparison.

METHODS

The study cohort has been previously described (5). The inclusion criterion was CHD necessitating cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) prior to 45 weeks post-conception age. Exclusion criteria were a known genetic syndrome, a major extra-cardiac anomaly, and language other than English spoken in the home. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Informed, written consent was obtained from parents or guardians of all the participants. Details of the prenatal course and perioperative outcomes were abstracted from the medical record.

At the time of delivery, the placental weight was measured using standard approaches (11). The newborn length, weight and head circumference was measured and the z-score of each growth measurement was calculated using WHO standards for full-term infants and the Fenton growth chart for pre-term infants (12, 13). Survival data and vital status were obtained from the medical record and family contact.

For this study, gestational hypertension (GHTN) was defined as two blood pressure measurements in excess of 140/90 mmHg at least 4 hours apart at >20 weeks gestational age. Preeclampsia was defined as GHTN with proteinuria or end-organ (liver or kidney) injury. Fetal echocardiography data were obtained from the medical record. The middle cerebral artery (MCA) and umbilical artery (UA) pulsatility indices (PI) were measured in accordance with standard practice. The cerebroplacental ratio (CPR) was obtained by dividing the MCA-PI by the UA-PI. The UA-PI and CPR vary by gestational age; they were converted to z-scores using a web-based calculator (https://fetalmedicine.org/research/doppler). Placental weights were not available for infants born at other institutions or lacking a prenatal diagnosis of CHD (24/133; 18%).

Although subjects with a known genetic syndrome (including for example Down, DiGeorge, VACTRL, Noonan, CHARGE, and Kabuki syndrome) were excluded prior to enrollment, many anomalies are not diagnosed by usual prenatal care and recognition of dysmorphic features can be difficult in neonates, thus some subjects with unrecognized syndromes were enrolled. Patients were evaluated by a genetic dysmorphologist at the 18 month neurodevelopmental evaluation and some previously unrecognized anomalies were identified. Genetic testing was performed as clinically indicated. Patients were classified as “abnormal/suspect” if they had a definite or suspected genetic syndrome or chromosomal abnormality.

To determine if PRA variants were more common in subjects with CHD, exome sequences from a control population of 200 subjects without CHD were analyzed using the same analysis pipeline and variant adjudication approach. The control cohort is composed of healthy parents of children evaluated at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia for non-cardiac conditions. The controls are unrelated to any of the cases but have very similar demographic and racial/ethnic composition.

Whole exome sequencing was performed on 133 subjects and all consented parents (114 parent-child trios, 15 parent-child duos and 4 child only). Exons were captured from fragmented and adaptor ligated genomic DNA samples using the SureSelect Human All Exon v.5 containing 51 Mb (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Paired-end 2×101-base massively parallel sequencing was carried out on the Illumina HiSeq2500 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA), according to the manufacture’s protocols. Base calling was performed by the Illumina CASAVA software (version 1.8.2) with default measures. Sequencing reads passing the quality filter were aligned to the human reference genome (GRCh37-derived alignment set used in 1000 Genomes Project) with Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA, v.0.7.12) and Dragen (14). PCR duplicates were removed using Picard (v.1.97). The Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK, v.2.6–5) was used to generate variant calls (15).

The Gene Ontology (GO) database was used to identify the target gene set. The GO term “positive regulator of angiogenesis” (PRA) (GO:0045766) was selected to minimize potential opposing effects of damaging variants in positive and negative regulators. The PRA gene set contains 163 genes (see accompanying Data in Brief).

Damaging variants in the PRA gene set were identified using the GeneVetter program (16), a web-based analysis tool designed to improve the accuracy of pathogenicity prediction for single nucleotide variants identified by exome sequencing. To be adjudicated as damaging by using the program’s default settings, a variant must meet all of the following criteria: (i) have a maximum allele frequency in the sample population of <0.05, (ii) be adjudicated as “Damaging” by at least 2 of 3 of the following algorithms: PolyPhen2, SIFT, and MutationTaster, and (iii) have a maximum allele frequency across European Americans and African Americans of <0.005.

Data are reported as frequency with percentage for categorical variables and mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range) for continuous variables. Patient characteristics, growth and outcomes measures by presence/absence of damaging PRA variants were evaluated using Chi-square test or Fisher exact test for categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank sum test or two-sample t-test for continuous variables. Similarly, univariate associations of patient and clinical characteristics with each of fetal growth z-scores at birth, and UA-PI and CPR z-scores were examined using 2-sample t-test. Factors found to be associated with each of fetal growth z-scores at birth and CPR z-score in univariate analysis (P<0.1) were included in the multivariable analysis. Multivariable linear regression was performed to evaluate an independent association of patient characteristics identified from the univariate analysis with each of fetal growth z-scores at birth and CPR z-score. Least square mean ± standard error from multivariable regression was also reported. Survival was examined using Kaplan-Meier curve and compared between subjects with and without presence of a damaging PRA variant using log-rank test. All of the statistical analyses were performed using SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Of the 133 subjects in the study, 81 (60.9%) were male (Table I). Gestational hypertension was identified in 10 pregnancies (7.5%) and was associated with pre-eclampsia in 7 of those cases (5.3%). The most common cardiac diagnoses were hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) in 41 subjects (30.8%) and d-transposition of the great arteries (TGA) in 48 subjects (36.1%). The median age at operation was 4 days. During median 3.1 years (interquartile range 2.0–4.1 years) of follow-up, there were 11 deaths (8.3%) in the cohort at a median of 4.5 months after surgery.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (N=133)

| All (N=133) | Variant | P-value§ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (N=60) | 1 or 2+ (N=73) | |||

| Male sex | 81 (60.9) | 40 (66.7) | 41 (56.2) | 0.22 |

| Non-Caucasian race | 30 (22.6) | 14 (23.3) | 16 (21.9) | 0.85 |

| Genetic anomaly | 0.049β | |||

| Suspect | 20 (15.0) | 7 (11.7) | 13 (17.8) | |

| Abnormal | 13 (9.8) | 3 (5.0) | 10 (13.7) | |

| Small for gestational age | 16 (12.0) | 3 (5.0) | 13 (17.8) | 0.02 |

| Preterm birth (gestational age < 37 weeks) | 10 (7.5) | 4 (6.7) | 6 (8.2) | 1.00 |

| Gestational hypertension (with or without pre-eclampsia) | 10 (7.5) | 3 (5.0) | 7 (9.6) | 0.51 |

| Birth weight, kg | 3.2 ± 0.51 | 3.3 ± 0.46 | 3.2 ± 0.54 | 0.049 |

| Placental weight, gram (N=109) | 442 (376–504) | 422 (380–520) | 448 (364–504) | 0.93 |

| Placental weight/Birth weight, % (N=109) | 13.5 (12.0–15.2) | 12.9 (11.3–15.3) | 13.8 (12.1–15.0) | 0.36 |

| Birth length, cm | 49.1 ± 3.1 | 49.9 ± 2.8 | 48.4 ± 3.2 | 0.005 |

| Birth head circumference, cm | 33.7 ± 1.6 | 34.1 ± 1.6 | 33.4± 1.6 | 0.02 |

| Weight z-score | −0.09 ± 0.94 | 0.08 ± 0.86 | −0.22 ± 0.98 | 0.06 |

| Length z-score | −0.14 ± 1.45 | 0.23 ± 1.36 | −0.44 ± 1.46 | 0.01 |

| Head circumference z-score | −0.28 ± 1.17 | −0.05 ± 1.20 | −0.47 ± 1.12 | 0.04 |

| Diagnosis | 0.35γ | |||

| IAA/Arch | 6 (4.5) | 2 (3.3) | 4 (5.5) | |

| TGA | 48 (36.1) | 30 (50.0) | 18 (24.7) | |

| TOF | 10 (7.5) | 2 (3.3) | 8 (11.0) | |

| Truncus | 6 (4.5) | 1 (1.7) | 5 (6.8) | |

| Other | 22 (16.5) | 9(15.0) | 13 (17.8) | |

| Single ventricle | 0.15 | |||

| No | 82 (61.7) | 41 (68.3) | 41 (56.2) | |

| Age at the first operation, days | 4 (3–6) | 4 (3–5) | 5 (3–7) | 0.04 |

| Weight at the first operation, kg | 3.3 ± 0.63 | 3.4 ± 0.64 | 3.2 ± 0.60 | 0.02 |

| Duration of follow-up, years | 3.1 (2.0–4.1) | 3.2 (2.0–4.2) | 3.0 (1.7–4.0) | 0.25 |

Data are presented as N (%) for categorical variables and Median (interquartile range) or Mean ± Standard deviation for continuous variables.

P-value for a comparison of variant 0 vs. 1 or. 2+ from Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank sum test or two-sample t-test for continuous variables.

Comparison was made as Suspect or Abnormal vs. None.

Comparison was made as HLHS vs. all others.

GeneVetter identified 113 pathogenic variants in the 163 PRA genes in 73 subjects (see accompanying Data in Brief for summary of specific variants); there were 60 subjects (45%) with no identified pathogenic variants. All variants were inherited or inheritance could not be assessed (affected 19/133 subjects due to lack of sequence from one or both parents). GeneVetter analysis of exome sequence from 200 control individuals without known CHD revealed a similar prevalence of damaging PRA variants (197 pathogenic variants identified in 125 subjects; there were 75 subjects (37.5%) with no identified pathogenic variants) (data not shown).

The clinical characteristics, growth and outcomes measures of subjects with and without PRA variants are summarized in Table 1. The prevalence of GHTN was not significantly different in pregnancies with or without a damaging PRA variant in the fetus (occurring in 7/73 pregnancies with and 3/60 pregnancies without a damaging PRA variant; P=0.51). Presence of a damaging PRA variant in the child with CHD was not associated with placental weight (median 488 g with PRA variant vs. 422 g without; P=0.93) or placental weight/birth weight ratio (median 13.8% with PRA variant vs. 12.9% without; P=0.36).

The impact of damaging angiogenic variants on fetal growth was determined by assessing weight, length and head circumference z-scores at the time of birth. In both univariate and multivariable analyses, there was a trend toward reduced birth weight z-score in subjects with at least one damaging PRA variant (Table 2). The presence of a damaging PRA variant was significantly associated with lower length z-score at birth in the univariate analysis (mean −0.44 with PRA variant vs. 0.23 without; P=0.01) and remained independently associated with lower length z-score at birth in multivariable analysis (P=0.01) controlling for GHTN (Table 2). The presence of at least one damaging PRA variant was also associated with lower birth head circumference z-score in both univariate and multivariable analyses (Table 2). Although we noted that the infants with TGA tended to be larger than those with HLHS at birth, we found that there was an effect of PRA variants on fetal growth regardless of the type of heart defect (at least with respect for HLHS and TGA for which there were sufficient numbers to evaluate).

Table 2.

Factors associated with each of fetal growth parameter

| Unadjusted | Weight z-score | Height z-score | Head circumference z-score | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | P-value¥ | Mean ± SD | P-value¥ | Mean ± SD | P-value‡ | |

| Sex Male |

−0.16 ± 0.99 |

0.25 |

−0.13 ± 1.54 |

0.93 |

−0.29 ± 1.19 |

0.92 |

| Female | 0.03 ± 0.85 | −0.15 ± 1.32 | −0.27 ± 1.15 | |||

| Race Caucasian |

0.01 ± 0.92 |

0.02 |

−0.03 ± 1.51 |

0.12 |

−0.14± 1.18 |

0.01 |

| Non-Caucasian | −0.42 ± 0.96 | −0.50 ± 1.18 | −0.75 ± 1.05 | |||

| Genetic anomaly None |

−0.06 ± 0.92 |

0.53 |

−0.17 ± 1.44 |

0.43 |

−0.31 ± 1.22 |

0.55 |

| Abnormal/Suspect | −0.17 ± 1.01 | −0.04 ± 1.49 | −0.17 ± 1.02 | |||

| Gestational hypertension Yes |

−0.82 ± 0.90 |

0.01 |

−1.18 ± 1.85 |

0.02 |

−0.97 ± 1.14 |

0.051 |

| No | −0.03 ± 0.92 | −0.05 ± 1.39 | −0.22 ± 1.16 | |||

| Diagnosis HLHS |

−0.18 ± 0.95 |

0.46 |

−0.40 ± 1.41 |

0.16 |

−0.28 ± 1.24 |

0.98 |

| Others | −0.04 ± 0.94 | −0.02 ± 1.46 | −0.28 ± 1.15 | |||

| Single ventricle Yes |

−0.17 ± 1.00 |

0.39 |

−0.36 ± 1.37 |

0.16 |

−0.34 ± 1.20 |

0.65 |

| No | −0.03 ± 0.90 | −0.01 ± 1.49 | 0.24 ± 1.15 | |||

| PRA gene variants 0 |

0.08 ± 0.86 |

0.06 |

0.23 ± 1.36 |

0.01 |

−0.05 ± 1.20 |

0.04 |

| 1 or 2+ | −0.22 ± 0.98 | −0.44 ± 1.46 | −0.47 ± 1.12 | |||

| Adjusted | LSMean ± SE | P-value | LSMean ± SE | P-value | LSMean ± SE | P-value |

| Race Caucasian |

−0.27 ± 0.16 |

0.04 | N/A | N/A |

−0.38 ± 0.20 |

0.02 |

| Non-Caucasian | −0.66 ± 0.20 | −0.95 ± 0.25 | ||||

| Pregnancy-induced hypertension Yes |

−0.81 ± 0.29 |

0.03 |

−1.05 ± 0.44 |

0.03 |

−0.95 ± 0.36 |

0.13 |

| No | −0.13 ± 0.10 | −0.03 ± 0.13 | −0.37 ± 0.12 | |||

| PRA gene variants 0 |

−0.33 ± 0.18 |

0.08 |

−0.23 ± 0.27 |

0.01 |

−0.46 ± 0.23 |

0.04 |

| 1 or 2+ | −0.61 ± 0.16 | −0.85 ± 0.25 | −0.86 ± 0.21 | |||

Abbreviations: SE, standard error; LSMean, least squares mean.

Data are presented as Mean ± Standard deviation from univariate analysis and LSMean ± SE from multivariable analysis.

P-value from two-sample t-test.

P-value from multivariable linear regression.

The presence of a damaging PRA variant in the fetus was associated with an increased UA-PI z-score (mean 1.2 with PRA variant vs 0.62 without; P=0.03) (Table 3). Although there was a trend toward reduced CPR z-score in the fetus with a damaging PRA variant, this association did not reach statistical significance in univariate or multivariable analysis (Table 3).

Table 3.

Factors associated with UA PI z-score and MCA/UA PI (CPR) z-score

| Unadjusted | UA PI z-score | CPR z-score | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | P-value¥ | Mean ± SD | P-value‡ | |

| Sex | 0.26 | 0.32 | ||

| Female | 0.73 ± 1.57 | −0.91 ± 1.74 | ||

| Race | 0.99 | 0.17 | ||

| Non-Caucasian | 0.93 ± 1.49 | −0.68 ± 1.82 | ||

| Genetic anomaly | 0.76 | 0.29 | ||

| Abnormal/Suspect | 1.00 ± 1.21 | −1.60 ± 2.42 | ||

| Diagnosis | 0.62 | 0.04 | ||

| Others | 0.88 ± 1.47 | −0.86 ± 1.83 | ||

| Single ventricle | 0.58 | 0.14 | ||

| No | 0.87 ± 1.50 | −0.91 ± 1.90 | ||

| PRA gene variants | 0.03 | 0.055 | ||

| 1 or 2+ | 1.20 ± 1.25 | −1.47 ± 1.97 | ||

| Adjusted | LSMean ± SE | P-value | LSMean ± SE | P-value |

| Diagnosis | N/A | N/A | 0.0495 | |

| Others | −0.85 ± 0.22 | |||

| PRA gene variants | N/A | N/A | 0.08 | |

| 1 or 2+ | −1.56 ± 0.25 | |||

Abbreviations: SE, standard error; LSMean, least squares mean.

Data are presented as Mean ± Standard deviation from univariate analysis and LSMean ± SE from multivariable analysis.

P-value from two-sample t-test.

P-value from multivariable linear regression.

Presence of a damaging PRA variant was also associated with a trend toward reduced survival based on Kaplan-Meier analysis (log-rank test; P=0.06); deaths occurred in 2/60 (3.3%) subjects with no PRA variants and 9/73 (12.3%) subjects with at least one variant. Because 8/11 deaths occurred in subjects with HLHS, we examined that subset of patients specifically and noted that deaths occurred in 1/16 HLHS subjects (6.3%) with no damaging PRA variants and 7/25 HLHS subjects (28.0%) with at least one damaging variant, but this did not reach statistical significance (log-rank test; P=0.09).

Because maternal angiogenesis is also required for placental development and maturation, we assessed whether maternal PRA variants, either inherited or not inherited by the fetus, had a greater effect on placental function and fetal growth than a paternal PRA variant. Although the numbers were small, inherited PRA variants affected height and head circumference at birth if they were inherited from the mother (see accompanying Data in Brief). Damaging PRA variants inherited from the father demonstrated a reduced length and head circumference in the fetus but this did not reach statistical significance in this cohort. In contrast, variants present in either parent that were not inherited by the child had no significant effect on fetal growth or placental function (see the accompanying Data in Brief for more detailed analysis).

After we completed our analysis, we performed similar analyses with several other gene sets to make sure that these findings were specific to the PRA gene set and did not simply reflect a higher damaging variant burden across multiple pathways. We examined 6 other pathways, 3 related to angiogenesis (GO:0001525; GO:0048010; GO:0001938) and 3 unrelated (GO:0045927; GO:0045862; GO:0042088), and found no significant association with any of the fetal growth measures with damaging variant burden in 5 out of the 6 other gene sets (data not shown). Only the angiogenesis gene set (G0001525) which has 478 genes including the 163 genes of the PRA gene set showed an effect on fetal growth (weight for age z-score and head circumference for age z-score).

DISCUSSION

In this study, pathogenic variants in PRA genes were associated with impaired fetal growth, as determined by length and head circumference z-scores at birth. The growth deficiency may be secondary to placental dysfunction as there was also an increase in the UA-PI, an indicator of placental insufficiency.

The findings are consistent with what is known about placental development and the relationship between placental development and fetal growth. The placenta is a highly-vascularized organ, with vessels of maternal and fetal origin.(17, 18) Dysregulation of angiogenesis in the maternal-fetal circulation is one of the main pathophysiological correlates of pregnancy-induced hypertension, preeclampsia, and fetal growth restriction (FGR).(18,,19) Angiogenic factors, including VEGF, angiopoietins, placental growth factor (PGF) and endoglin (ENG) regulate placental vasculogenesis and angiogenesis.(18) Alterations in these factors lead to impaired angiogenesis resulting in ischemic placental disease with preeclampsia and FGR.(18, 20) Mothers with preeclampsia and FGR show anti-angiogenic profiles characterized by elevated plasma levels of soluble Flt-1 (sFlt-1) and ENG with reduced PGF and VEGF levels.(8, 21) Based on these studies, enhancement of placental angiogenesis through overexpression of VEGF has been proposed as a therapeutic approach to FGR (22).

Vascular signaling in pregnancy is influenced by genetic factors. Variation in genes which modulate angiogenesis, including VEGFA, VEGFC, Flt1, hypoxia inducible factor 1α (HIF1α), and ENG, have been associated with the risk of preeclampsia, preterm birth and FGR (7, 8, 23–26). Variants upstream of the Flt-1 gene, which encodes for a VEGF receptor, were associated with late-term pre-eclampsia in a large genome-wide association study (26). In addition, presence of the VEGF-T936 allele (associated with reduced VEGFA expression) in both the mother and fetus increases the risk of GHTN and preeclampsia.(8) When both the mothers and newborns were carriers, there was an anti-angiogenic profile with lower maternal VEGF and higher sFlt1 levels and mothers with PIH and severe preeclampsia had a greater risk of preterm birth (<37 weeks’ gestation) and FGR.(8)

How these genetic factors may modify the effects of other conditions which influence fetal growth and development has not been well studied. Recent studies have noted impaired fetal growth and development in pregnancies involving fetal CHD. Infants with CHD are more likely to be SGA (27) an effect that may be even more pronounced when the fetus has a single ventricle heart defect. The fact that the damaging PRA variants had an effect on growth of both HLHS subjects and TGA subjects in our study suggest that the variants’ effects on growth are not dependent on the type of heart defect (and the associated differences in fetal blood flow and tissue oxygenation patterns).

The mechanism for the growth impairment may be due to relative placental vascular insufficiency regardless of CHD subtype in the presence of a damaging PRA variant in the fetus. The increased UA-PI in the presence of damaging PRA variant in the fetus indicates altered placental flow dynamics with increased placental vascular resistance. High resistance reduces diastolic flow velocity, increasing the difference between systolic and diastolic flow velocity and increasing UA pulsatility.

In utero growth and development is an important emerging contributor to clinical outcomes in patients with CHD. Infants who are small for gestational age (SGA) at birth, which can result from reduced growth potential and/or fetal growth restriction, have increased operative mortality, and an increased rate of major complications including prolonged mechanical ventilation and hospital length of stay, postoperative cardiac arrest, and infection. In a cohort of infants undergoing cardiac surgery, 30-day mortality was greater in SGA infants, even in those with normal birth weight (>2500 g).(27) In our cohort, we did note a trend towards increased postoperative mortality in subjects with a damaging PRA variant that may result from its effects on fetal growth and development. The potential effects merit further study.

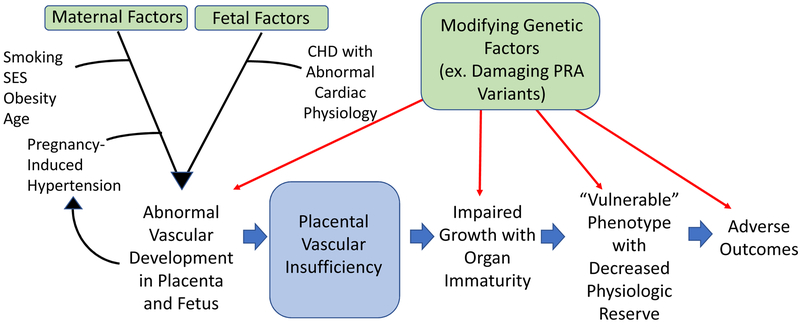

The emerging model from this study and others is that there are maternal and fetal factors that affect placental health and function in pregnancies involving fetal CHD (Figure). Impaired placental function, in turn, impacts fetal growth and development. The incidence and severity of the effects of fetal CHD on growth and development can be modified by an array of maternal and fetal factors including genetic variation affecting angiogenesis.

Figure:

Impaired in utero vascular development in CHD

There are some important study limitations. First, due to the limited sample size, a specific biologic process was examined. It may not be the most important process regulating fetal growth. An undirected examination of all pathologic variants and adjudication of the pathways and processes most affected will be required to determine if there are processes with an even more substantial effect on fetal growth in subjects with CHD. Furthermore, there are multiple signaling pathways that promote angiogenesis; which of these are most important and might be most suitable for therapeutic targeting cannot be determined in a cohort of this size.

The findings advance the understanding of how individual genetic factors may have an important impact on placental function and on fetal growth and development in pregnancies affected by fetal CHD. Of particular relevance will be how genetic variant-mediated vulnerability of or reduced capability for angiogenesis may impact the ability of the fetus with CHD to grow and develop in utero and, potentially, affect their intermediate term survival after cardiac surgery in infancy.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Daniel M. Tabas and Alice Langdon Warner Endowed Chairs in Pediatric Cardiothoracic Surgery and the Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and the Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, and NIH/NCATS (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences) (UL1TR000003). The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Mark W. Russell, Division of Pediatric Cardiology, Department of Pediatrics, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI.

Julie S Moldenhauer, Center for Fetal Diagnosis and Therapy, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA.

Jack Rychik, Division of Pediatric Cardiology, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA.

Nancy B. Burnham, Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA.

Erin Zullo, Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA.

Samuel I Parry, Division of Maternal Fetal Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine, The University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA.

Rebecca A Simmons, Division of Neonatology, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA.

Michal A Elovitz, Division of Maternal Fetal Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine, The University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA.

Susan C Nicolson, Division of Cardiothoracic Anesthesiology, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA.

Rebecca L. Linn, Division of Anatomic Pathology, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA.

Mark P Johnson, Center for Fetal Diagnosis and Therapy, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA.

Sunkyung Yu, Division of Pediatric Cardiology, Department of Pediatrics, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI.

Matthew G. Sampson, Division of Pediatric Nephrology, Department of Pediatrics, and Center for Computational Medicine and Bioinformatics, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI.

Hakon Hakonarson, The Center for Applied Genomics, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and the Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA.

J. William Gaynor, Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gaies MBM, Zhang W, Russell M, Gaynor JW, Pasquali S The Quest for Precision Medicine: Unidentified Patient Factors Predict Mortality After Congenital Heart Surgery. Circulation. 2018;136:A18860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacobs JP, O’Brien SM, Pasquali SK, Gaynor JW, Mayer JE Jr., Karamlou T, et al. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Congenital Heart Surgery Database Mortality Risk Model: Part 2-Clinical Application. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;100:1063–8; discussion 8–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams RV, Ravishankar C, Zak V, Evans F, Atz AM, Border WL, et al. Birth weight and prematurity in infants with single ventricle physiology: pediatric heart network infant single ventricle trial screened population. Congenit Heart Dis. 2010;5:96–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matthiesen NB, Henriksen TB, Agergaard P, Gaynor JW, Bach CC, Hjortdal VE, et al. Congenital Heart Defects and Indices of Placental and Fetal Growth in a Nationwide Study of 924 422 Liveborn Infants. Circulation. 2016;134:1546–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaynor JW, Parry S, Moldenhauer JS, Simmons RA, Rychik J, Ittenbach RF, et al. The impact of the maternal-foetal environment on outcomes of surgery for congenital heart disease in neonates. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2018;54:348–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones HN, Olbrych SK, Smith KL, Cnota JF, Habli M, Ramos-Gonzales O, et al. Hypoplastic left heart syndrome is associated with structural and vascular placental abnormalities and leptin dysregulation. Placenta. 2015;36:1078–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Srinivas SK, Morrison AC, Andrela CM, Elovitz MA. Allelic variations in angiogenic pathway genes are associated with preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202:445 e1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Procopciuc LM, Caracostea G, Zaharie G, Stamatian F. Maternal/newborn VEGF-C936T interaction and its influence on the risk, severity and prognosis of preeclampsia, as well as on the maternal angiogenic profile. The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine: the official journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstet. 2014;27:1754–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim DS, Kim JH, Burt AA, Crosslin DR, Burnham N, McDonald-McGinn DM, et al. Patient genotypes impact survival after surgery for isolated congenital heart disease. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;98:104–10; discussion 10–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mavroudis CD, Seung Kim D, Burnham N, Morss AH, Kim JH, Burt AA, et al. A vascular endothelial growth factor A genetic variant is associated with improved ventricular function and transplant-free survival after surgery for non-syndromic CHD. Cardiol Young. 2018;28:39–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khong TY, Mooney EE, Ariel I, Balmus NC, Boyd TK, Brundler MA, et al. Sampling and Definitions of Placental Lesions: Amsterdam Placental Workshop Group Consensus Statement. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016;140:698–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fenton TR, Kim JH. A systematic review and meta-analysis to revise the Fenton growth chart for preterm infants. BMC Pediatr. 2013;13:59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Onis M, Garza C, Victora CG, Onyango AW, Frongillo EA, Martines J. The WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study: planning, study design, and methodology. Food Nutr Bull. 2004;25:S15–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DePristo MA, Banks E, Poplin R, Garimella KV, Maguire JR, Hartl C, et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat Genet. 2011;43:491–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gillies CE, Robertson CC, Sampson MG, Kang HM. GeneVetter: a web tool for quantitative monogenic assessment of rare diseases. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3682–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cerdeira AS, Karumanchi SA. Angiogenic factors in preeclampsia and related disorders. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khankin EV, Royle C, Karumanchi SA. Placental vasculature in health and disease. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2010;36:309–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Llurba E, Crispi F, Verlohren S. Update on the pathophysiological implications and clinical role of angiogenic factors in pregnancy. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2015;37:81–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hod T, Cerdeira AS, Karumanchi SA. Molecular Mechanisms of Preeclampsia. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2015;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alahakoon TI, Zhang W, Trudinger BJ, Lee VW. Discordant clinical presentations of preeclampsia and intrauterine fetal growth restriction with similar pro- and anti-angiogenic profiles. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014;27:1854–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.David AL. Maternal uterine artery VEGF gene therapy for treatment of intrauterine growth restriction. Placenta. 2017;59 Suppl 1:S44–S50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bell MJ, Roberts JM, Founds SA, Jeyabalan A, Terhorst L, Conley YP. Variation in endoglin pathway genes is associated with preeclampsia: a case-control candidate gene association study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andraweera PH, Dekker GA, Thompson SD, Dissanayake VH, Jayasekara RW, Roberts CT. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha gene polymorphisms in early and late onset preeclampsia in Sinhalese women. Placenta. 2014;35:491–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Langmia IM, Apalasamy YD, Omar SZ, Mohamed Z. Association of VEGFA gene polymorphisms and VEGFA plasma levels with spontaneous preterm birth. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2015;25:199–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McGinnis R, Steinthorsdottir V, Williams NO, Thorleifsson G, Shooter S, Hjartardottir S, et al. Variants in the fetal genome near FLT1 are associated with risk of preeclampsia. Nat Genet. 2017;49:1255–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sochet AA, Ayers M, Quezada E, Braley K, Leshko J, Amankwah EK, et al. The importance of small for gestational age in the risk assessment of infants with critical congenital heart disease. Cardiol Young. 2013;23:896–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]