Abstract

Objective:

The intestinal lumen contains several proteases. Our aim was to determine the role of fecal proteases in mediating barrier dysfunction and symptoms in IBS.

Design:

39 IBS patients and 25 healthy volunteers completed questionnaires, assessments of in vivo permeability, ex vivo colonic barrier function in Ussing chambers, tight junction (TJ) proteins, ultrastructural morphology, and 16s sequencing of fecal microbiota rRNA. A casein-based assay was used to measure proteolytic activity (PA) in fecal supernatants (FSNs). Colonic barrier function was determined in mice (ex-germ free) humanized with microbial communities associated with different human PA states.

Results:

IBS patients had higher fecal PA than healthy volunteers. 8/20 post infection-IBS (PI-IBS) and 3/19 IBS-C had high PA (>95 percentile). High PA patients had more and looser bowel movements, greater symptom severity, higher in vivo and ex vivo colonic permeability. High PA FSNs increased paracellular permeability, decreased occludin and increased pMLC expression. Serine but not cysteine protease inhibitor significantly blocked high PA FSN effects on barrier. The effects on barrier were diminished by pharmacological or siRNA inhibition of PAR-2. High PA IBS patients had lower occludin expression, wider TJs on biopsies and reduced microbial diversity than low PA patients. Mice humanized with high PA IBS microbiota had greater in vivo permeability than those with low PA microbiota.

Conclusion:

A subset of IBS patients, especially in PI-IBS, has substantially high fecal PA, greater symptoms, impaired barrier and reduced microbial diversity. Commensal microbiota affects luminal proteolytic activity which can influence host barrier function.

Keywords: trypsin, microbiome, Campylobacter, gastroenteritis, germ-free mice

INTRODUCTION

A large number of proteases and protease inhibitors are present in the intestinal lumen and the mucosa.[1] The pancreas, intestinal epithelial cells,[2] immune cells (neutrophils, mast cells, macrophages)[3] and the commensal microbiota[4–6] all produce proteases. These proteases play important roles in maintaining physiological homeostasis and in host defense mechanisms during infection and inflammation.[7] Serine and cysteine proteases are the most abundant family of fecal proteases.[8] Protease inhibitors like secretory leucocyte protease inhibitor (SLPI), serpins and elafin secreted by the host and microbes counter the action of proteases.[9–11] A significantly higher and qualitatively different proteolytic activity (PA) has been described in the ileostomy contents compared to the feces.[12, 13] Additionally, germ free (GF) or microbiota depleted mice using antibiotics have been shown to have higher fecal PA.[14, 15] This suggests that microbiota is important for modulation of PA, and transit through the colon results in depletion of PA, either due to the direct effects of microbiota or from the effects of microbiota on the host.

An increased PA has been described in fecal and tissue supernatants from both diarrhea and constipation predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) patients.[16–20] Administration of these supernatants in mice resulted in increased intestinal permeability and development of visceral hypersensitivity.[16, 18, 21, 22] Exaggerated peripheral nociceptive signaling (and increased PA) was seen in a mouse model of Citrobacter infection which could be blocked by protease inhibitors.[23] However, the effect of proteases on intestinal barrier function in humans with IBS and the role of microbiota in regulation of PA and barrier function has not been studied. Patients with post-infection IBS (PI-IBS) develop IBS after an acute intestinal infection and have been described to have alterations in epithelial, immune and microbial structure.[24, 25] It is unknown if patients with PI-IBS also have changes in the fecal protease milieu.

The primary objective of this study was to determine the role of PA on barrier function in post-infection IBS (PI-IBS) and in constipation predominant IBS (IBS-C) and to associate it with clinical symptoms and microbiota composition.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human subjects

39 IBS (20 PI-IBS and 19 IBS-C) patients who met the Rome III criteria for IBS and 25 healthy volunteers were prospectively recruited. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are provided in Supplementary Methods. Mayo Clinic IRB approved the study and all participants provided written informed consent for participation in the study.

Stool preparation

100 mg of stool was diluted in 0.8 mL of phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and homogenized using a pellet pestle (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). After centrifuging twice for 10 min, 5000 g at 4°C, supernatants were filtered with 0.22 μm spin-x tube filters (Corning Life Sciences, Durham, NC, USA). Fecal supernatants (FSN) were freshly made prior to each experiment.

Proteolytic activity measurement

PA was measured in FSN in triplicates using Pierce Fluorescent Protease Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific, St. Peters, MO, USA). Briefly, 5μl of FSN was added to 195 μl of fluorescein isothiocyanate labeled (FITC) casein substrate on 96-well plates to digest into smaller, labeled fragments. After 10 minutes incubation, the plates were read at 485/528 filter (Synergy™ Mx Multi-Mode Microplate Reader; BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA). PA was normalized to protein content measured by the Bradford dye-binding method (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). To determine protease family driving PA, selective serine protease inhibitor, AEBSF (4-(2-Aminoethyl) benzenesulfonyl fluoride hydrochloride, 0.2 mM) and selective cysteine protease inhibitor (E64 0.1 mM) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) were used. Additional details on dose titration for inhibitors is provided in Supplementary Methods. Additionally, trypsin-like, chymotrypsin-like, neutrophil elastase, pancreatic elastase and kallikrein proteolytic activities were determined using their respective substrates N-p-Tosyl-Gly-Pro-Arg 7-amido-methylcoumarin HCl (AMC),[26] Suc-Ala-Ala-Pro-Phe-AMC,[27] Suc-Ala-Ala-Pro-Val-AMC,[28] Suc-Ala-Ala-Ala-AMC[29] and Pro-Phe-Arg-AMC.[30, 31] The fecal supernatants were mixed with 100μM substrate solution in 50mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0 containing 10mM CaCl2 in a microtiter plate. Substrate hydrolysis was determined based on change in fluorescence (Excitation/Emission = 380/460) measured kinetically for 15 minutes at 37 0C on a BioTek Synergy™ Mx Microplate Reader. The amount of product released (nmoles/min) by each enzyme was determined using a standard curve generated for free AMC and this was converted to specific activity (nmoles/min/μg) using the protein concentration obtained for each sample by Bradford method. Additionally, activity-based probes (ABP) have been developed for assessment of serine protease activity in secreted contents[32] as well as in vivo.[33] They are based on covalent binding of active proteases to the reactive group on the ABP that mimics enzymatic substrate.

Cell culture

Human intestinal Caco-2 cells were cultured in 75 cm2 tissue culture flasks until confluent, then seeded at a density of 5×105 cells/mL on 12 well Polycarbonate Membrane Transwell® Inserts with the pore size of 0.4 μm (Corning Life Sciences, Durham, NC, USA) and cultured for 10–14 days with media changes every other day until cells established a monolayer. For western blot analysis, cells were seeded on 12 well plates at the same concentration. Additional details in Supplementary Methods.

In vitro flux measurement

After confirming the establishment of polarized monolayer with Epithelial Volt/ohm meter (EVOM2) (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL, USA) with Transepithelial resistance (TER) >350 Ω*cm2, Caco-2 cells were exposed to 100 μL of the FSN and 50 μg of 3000 Dalton Texas Red Dextran (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) on apical surface for 24 hrs. Texas Red Dextran flux was measured in basolateral media with the filter of 595/615 (Synergy™ Mx Multi-Mode Microplate Reader; BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA). AEBSF (final concentration 0.2 mM) or E64 (final concentration 0.1 mM) were added 30 min prior to FSN addition to determine the possible inhibitory effect on PA of FSN. 100μL of PBS, instead of FSN, was added for control experiments. The flux measurement was done in triplicate and the average flux percentage compared to PBS control was calculated.

In vitro transepithelial resistance measurement in cellZscope®

cellZscope® (NanoAnalytics, Münster, Germany) is an automated, parallel, real-time recording system for measurement of impedance in polarized epithelium using spectroscopy.[34] Further details are provided in Supplementary methods. AEBSF and E64 were used to study inhibition of FSN effects on barrier. Selective protease-activated receptor 2 (PAR-2) antagonist ENMD1068 150μM (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and selective inhibitor of myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) ML-7 10 μM (EMD Millipore, Danvers, MA, USA) were used to explore the downstream signaling mechanisms of FSN. All the inhibitors were applied 30 min prior to FSN addition. TER data were reported as percentages of baseline (before addition of inhibitors or FSN) and averaged for 3 technical replicates.

Suppression of PAR-2 expression in Caco-2 cells by siRNA

Caco-2 cells (1.25×105 cells/mL) were seeded in 25 cm2 tissue culture flasks. The cells were then allowed to grow and attach for 72 h. After the incubation, the cells were treated with serum-free DMEM and incubated for an additional 24 h. Transfection details are provided in Supplementary Methods. After a 24 h-incubation, cells were cultivated and seeded on Transwell® inserts. TER was measured 6 to 7 days after transfection. Transfection efficacy was assessed by qPCR gene expression (48 h and 6–7 d after transfection) and western blot analysis (6–7 d after transfection).

Western Blot analysis and immunofluorescence microscopy in cell culture and biopsies

For western blot, Caco-2 cells grown on 12-well plates were exposed to 200 μL of FSN/well (in 1000 μL of media) for 6 hours. For immunofluorescence, Caco-2 cells grown on 12-well Transwell® plates were exposed to 100 μL of FSN/well (in 500 μL of media) for 6 hours. Human colonic biopsies were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and mounted in O.C.T. compound (Sakura FineTek, Torrance, CA, USA). Further details are provided in Supplementary Methods.

Ex vivo assessment of barrier function on biopsies

A flexible sigmoidoscopy was done in all subjects following a tap water enema. Biopsies were mounted within 1 hour of collection on 4 mL Ussing chambers (Physiologic Instruments, San Diego, CA) exposing 0.031 cm2 area with Krebs with 10 mM mannitol and Krebs with 10 mM glucose on the mucosal and submucosal sides, respectively. FITC Dextran (3000–5000 Daltons) was used to measure paracellular flux. Further details are provided in Supplementary Methods.

Transmission Electron Microscopy

Biopsies were placed in Trump’s fixative for scanning electron microscopy. Tight junction width was measured using ImageJ software on ten tight junctions per biopsy and values were averaged. Details are provided in Supplementary Methods.

In situ zymography

Trypsin-like activity was determined on colonic mucosal biopsies using N-p-Tosyl-Gly-Pro-Arg 7-AMC. Details are provided in Supplementary Methods.

In vivo Permeability Testing

Measurement of in vivo intestinal permeability was done using lactulose and mannitol excretion based assay, as previously described and in Supplementary Methods.[35]

Transit Studies

Seventeen IBS patients (all PI-IBS) underwent scintigraphic intestinal transit analysis with a methacrylate-coated capsule which dissolves in the alkaline pH of the distal ileum to release 111In-labeled activated charcoal particles. Geometric center at 24 h was calculated for assessment of colonic transit as previously described.[36]

Microbiota Analysis

Microbiome analysis was done on a subset of IBS patients (11 high PA: 8 PI-IBS, 3 IBS-C and 19 low PA: 16 IBS-C, 3 PI-IBS). Stool samples were collected in a standardized fashion and stored at −80°C until further use. Sequencing details are provided in Supplementary Methods.

Humanized Mice

All animal experiments were approved by Mayo Clinic Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. GF Swiss Webster (outbred strain) female mice were housed in standard flexible film isolators (CBC, WI, USA) and given autoclaved feed and water. GF mice between 4–6 weeks of age were gavaged with 200 μL of the stool suspension (1:2 with pre-reduced PBS) and housed in individually ventilated Maxiseal TOTAL 420 cages (Arrowmight, Hereford, England) for 6 weeks to allow for stable colonization. Fecal PA was assessed as stated above on single pellets collected at baseline (4-week-old, germ-free) and 6-weeks post humanization (10-week-old) for each mouse. Additional details are provided in Supplementary Methods.

In vivo permeability testing in mice

Mice were fasted for 2 hours but allowed free access to water and then given an oral gavage (0.2 mL) containing 100 mg/mL creatinine, 60mg/mL FITC-4 kDa dextran and 40mg/mL of rhodamine B isothiocyanate-70 kDa dextran (Sigma). The three molecules allow assessment of pore (creatinine, radius 2.6 Å), leak (FITC-Dextran, radius 13 Å) and unrestricted (RITC-Dextran, radius 64 Å) barrier pathways.[37] Additional details are provided in Supplementary Methods.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean (SD) for continuous variables, and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. Mann-Whitney U test or Wilcoxon signed-ranks test, assuming non-Gaussian distributions, were used to analyze the data. For comparisons of >2 groups, non-parametric 1-way ANOVA test (Kruskal-Wallis) with post-hoc comparison was used. A p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. The study was powered for detecting changes in in vivo permeability between high and low PA IBS patients. A sample size of 10/group is sufficient to detect 26% difference (effect size) in 2–24 hr cumulative lactulose excretion between the 2 groups with 80% confidence. The remaining comparisons are secondary endpoints.

Microbiota composition analysis:

After sequencing, adapter-primer sequences were removed from reads as previously described.[38] All 30 samples, 4,120,057 reads (median 119,150 reads per sample, range 35,687 to 284,459), passed quality control (QC). Paired R1 and R2 sequence reads were then processed via the hybrid-denovo bioinformatics pipeline,[39] which clustered these good-quality paired-end and single-end reads into OTUs at 97% similarity level. OTUs were assigned taxonomy using the RDP classifier trained on the GreenGenes database (v13.5). Singleton OTUs as well as samples with less than 2,000 reads were removed as a QC step. A total of 817 OTUs were clustered and these OTUs belonged to 13 phyla, 60 families and 102 genera. Alpha-and beta-diversity were analyzed for the OTU data. Further details are provided in Supplementary Methods.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

Table 1 shows characteristics of healthy volunteers and IBS patients. Twelve of 20 PI-IBS patients were diarrhea predominant IBS (IBS-D) and 8 were mixed IBS (IBS-M) subtypes. Anxiety and depression scores were higher in IBS groups compared to healthy volunteers. However, there was no difference between the PI-IBS and IBS-C groups (p=0.15 for both anxiety and depression). There were no significant differences in the IBS-QOL score or the IBS-SSS between the PI-IBS and IBS-C groups.

Table 1:

Demographic characteristics of healthy volunteers and IBS patients

| Healthy volunteers | PI-IBS | IBS-C | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 41.6 (12.2) | 40 (15.1) | 45.4 (12.3) |

| Female/male | 23/2 | 14/6 | 19/0 |

| HADS Anxiety Score (mean, SD) | 2.7 (2.2) | 5.2 (3.8) | 3.4 (2.2)* |

| HADS Depression Score (mean, SD) | 0.4 (0.6) | 2.3 (2.8) | 1.1 (1.7)* |

| IBS Symptom Severity Score (mean, SD) | - | 254.5 (94) | 206.7 (78.7) |

| IBS Quality of Life Score (mean, SD) | - | 30.5 (19.9) | 32.3 (11.4) |

p<0.05 for healthy vs PI-IBS. Non-parametric 1-way ANOVA (Kruskal-Wallis) with Dunn’s post-hoc analysis

H&E examination of the colonic biopsies done by an independent blinded-observer (RG) showed no increase in neutrophils, eosinophils or mast cells (Tryptase staining).

Fecal proteolytic activity in PI-IBS and IBS-C

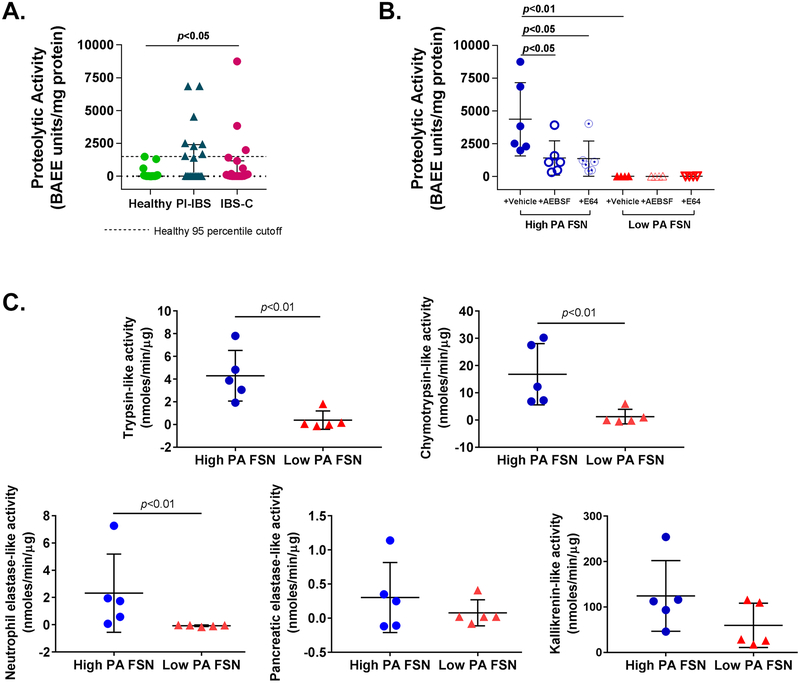

Proteolytic activity (PA) of FSNs from IBS patients was significantly higher than healthy volunteers {Mean (SD); Healthy 153.6 (392.2), PI-IBS 1510 (2221), IBS-C 967.4 (2122) BAEE units/mg protein, p<0.05} (Figure 1A). Within the IBS patients, a subset had higher PA than the rest and the healthy volunteers. We used 95 percentile of activity for healthy volunteers (1428.9 BAEE units/mg protein) for dividing IBS patients into a “high PA” and a “low PA” group. Eight of the 20 (40%) PI-IBS patients and 3 of 19 (16%) IBS-C patients were above the 95 percentile, resulting in a total of 11 out of 39 IBS patients classified as high PA. High PA in FSNs was significantly inhibited by incubation with serine protease inhibitor (AEBSF; 67.5% inhibition, p<0.05) or cysteine protease inhibitor (E64; 68.7% inhibition, p<0.05), while low PA was not affected upon incubation with the inhibitors (Figure 1B). Activity-based probes demonstrated that high PA IBS patients have greater activity of trypsin (3.9 vs 0.07 nmoles/min/μg, p<0.01), chymotrypsin (16.8 vs 1.2 nmoles/min/μg, p<0.01) and neutrophilic elastase (2.23 vs −0.07 nmoles/min/μg, p<0.01). However, the activity of pancreatic elastase and kallikrein was similar (Figure 1C).

Figure 1:

Characterisation of faecal proteolytic activity (PA). (A) Faecal PA in IBS and healthy subjects. PA of faecal supernatants (FSNs) was significantly higher in patients with IBS (n=39) compared with healthy volunteers (n=25) (p<0.05, one-way analysis of variance [ANOVA]). Eleven of 39 patients with IBS had PA >1429 BAEE units/mg protein (dotted line, 95th percentile PA for healthy volunteers), which was used to classify patients with IBS as ‘high PA’ and ‘low PA’. (B) Effect of protease inhibitors on faecal PA. PA from high-PA FSNs was significantly inhibited by serine protease inhibitor (AEBSF) and cysteine protease inhibitor (E64) (n=6/group, p<0.05, one-way ANOVA with repeated measures). No significant effect of inhibitors was seen with low-PA FSNs. (C) Serine protease characterisation using specific probes. High-PA IBS FSNs have greater trypsin-like, chymotrypsin-like, neutrophilic elastase-like activities (n=5/group, p<0.05, Mann-Whitney U test) but not pancreatic elastase-like or kallikrenin-like activities when compared with low PA IBS FSNs. AEBSF, 4-(2-aminoethyl) benzenesulfonyl fluoride hydrochloride; IBS-C, constipation-predominant IBS; PI-IBS, postinfection IBS.

Clinical and physiological characterization by proteolytic activity

Demographic and physiological characterization of IBS patients categorized by PA is summarized in Table 2. High PA patients had greater severity on the IBS-SSS {Mean (SD) high PA 293 (88.1), low PA 211 (75.9), p<0.05}. Within the PI-IBS cohort, the high PA patients (n=8) had greater frequency of bowel movements {Average bowel movement/day: 2.7 (0.9) vs 1.5 (0.6), p<0.01} and looser consistency {Average Bristol Stool Scale: 5.2 (0.5) vs 4.3 (0.9), p<0.05} than the low PA patients (n=12). Additionally, high PA IBS patients had higher in vivo colonic permeability and macromolecular (3–5 KDa FITC) flux across sigmoid colonic biopsies. Fecal PA positively correlated with 2–24 hr lactulose excretion (Spearman r=0.35, p<0.05) but not with TMR and FITC flux across biopsies (Supplementary Figure 1). No correlation was seen between fecal PA and colonic transit measured using geometric center at 24 hours (Supplementary Figure 2).

Table 2.

Demographic and physiological characteristics of high PA and low PA IBS patients

| High PA (n=11) | Low PA (n=28) | |

| Demographic Characteristics | ||

| Age (mean, SD) | 38.7, 12.1 | 44.1, 14.4 |

| Female/Male | 8/3 | 25/3 |

| HADS Anxiety Score (mean, SD) | 5.0, 4.9 | 4.0, 2.3 |

| HADS Depression Score (mean, SD) | 2.6, 3.6 | 1.3, 1.7 |

| IBS Symptom Severity Score (mean, SD) | 293, 88 | 211, 76* |

| IBS Quality of Life Score (mean, SD) | 38.5, 17.0 | 28.6, 15.1 |

| Ex vivo Colonic Barrier | ||

| Transmucosal resistance (mean, SD) Q*cm2 | 16.1, 7.0 | 21.1, 6.7† |

| 4KDa FITC flux at 3 hr (mg) | 350.9, 429.9 | 135.5, 175.4* |

| In vivo Colonic Permability | ||

| 2–24 hour cumulative lactulose excretion (mg) | 5.98, 5.6 | 2.48, 1.7* |

| Characteristics of subset chosen for PA inhibition & barrier experiments | High PA (n=6) | Low PA (n=6) |

| Demographic Characteristics | ||

| Age (mean, SD) | 39.8, 7.9 | 37.2, 14.8 |

| Female/Male | 5/1 | 5/1 |

| HADS Anxiety Score (mean, SD) | 3.3, 3.5 | 3.5, 2.4 |

| HADS Depression Score (mean, SD) | 1.3, 1.8 | 1.5, 1.4 |

| IBS Symptom Severity Score (mean, SD) | 314, 88 | 192, 72* |

| IBS Quality of Life Score (mean, SD) | 37.3, 13.4 | 36.9, 15.6 |

| Ex vivo Colonic Barrier | ||

| Transmucosal resistance (mean, SD) Q*cm2 | 14.4, 6.1 | 19.4, 7.1 |

| 4KDa FITC flux at 3 hr (mg) | 479.5, 485.5 | 249.4, 340.7 |

| In vivo Colonic Permeability | ||

| 2–24 hour cumulative lactulose excretion (mg) | 8.8, 6.9 | 2.9, 2.3 |

p<0.05;

p=0.07, Non-parametric t-test (Mann-Whitney)

Effect of fecal supernatants on in vitro barrier function

Six high PA patients and six low PA IBS patients were randomly selected from each group for subsequent in vitro experiments. The characteristics of this subset are also presented in Table 2. For electron microscopy and western blot experiments on biopsies, 1 high PA and 2 low PA patients had to be replaced due to lack of tissue availability. New patients were randomly selected from the larger cohort (presented in Table 1) and all results displayed. High PA FSNs caused greater increase in paracellular flux across Caco-2 monolayers compared to low PA FSNs {Mean (SD) 24 hr 3000 Da Texas Red dextran flux as % of PBS control; high PA 167.3 (29.3)%, low PA 106.7 (12.2)%, n=6/group, p<0.01) (Figure 2A). High PA FSNs caused significantly higher drop in TER compared to low PA FSNs {Mean (SD) 24 hr TER as % of initial TER; High PA 41 (12.9)%, low PA 116.1 (17.2)%, n=6/group, p<0.01) (Figures 2B,2C). Baseline PA of the FSN positively correlated with the magnitude of flux increase (Spearman r=0.66, p<0.05) and negatively with % of initial TER (Spearman r=−0.77, p<0.01) (Supplementary Figure 3). We also tested FSNs from two healthy volunteers with high PA (1304 and 1482 BAEE units/mg protein) and three randomly selected healthy volunteers with low PA. The high PA FSNs caused increased flux and drop in TER similar to that seen with high PA IBS FSNs, whereas, low PA FSNs did not result in flux increase or TER drop (Supplementary Figure 4).

Figure 2:

Effects of faecal supernatants on in vitro barrier function and effects of PAR-2 inhibition. (A) Effect of faecal PA on in vitro macromolecular flux. High proteolytic activity (PA) FSNs caused greater apical to basolateral flux of 3 KDa Texas Red Dextran across Caco-2 monolayers compared with low-PA FSNs (p<0.01) which was significantly inhibited by AEBSF (n=6/group, p<0.05, one-way analysis of variance [ANOVA] with repeated measures) but not by E64. Low-PA FSNs had no significant effect on flux. Similarly, AEBSF and E64 alone had no significant effect on flux. (B and C) Effect of faecal PA on in vitro transepithelial resistance (TER). High-PA FSNs caused significantly higher TER drop compared with low PA FSNs (n=6/group, p<0.01). TER drop caused by high-PA application was significantly inhibited by AEBSF and ENMD1068, a selective PAR-2 antagonist but not by E64 (n=6/group, p<0.05, one-way ANOVA with repeated measures for AEBSF and ENMD1068). Averaged 24-hour TER tracing: inhibitor added 30 min prior to FSN addition. (D) PAR-2 inhibition using siRNA. At day 7 following transfection of Caco-2 cells with RNAi, 40% inhibition of PAR-2 protein was observed. (E and F) siPAR-2-mediated inhibition of effects on barrier function. The TER drop after addition of high-PA FSN from day 6 to day 7 was significantly lower in siPAR-2 Caco-2 cells compared with negative controls (n=6/group, p<0.05, Mann-Whitney U test). FSNs, faecal supernatants.

The increased paracellular permeability caused by high PA FSNs was reduced significantly by serine protease inhibitor AEBSF (167% to 108% of PBS control, p<0.05), but not by cysteine protease inhibitor E64 (167.3% to 152% of PBS control) (Figure 2A). TER drop was also significantly inhibited by AEBSF (56% inhibition, p<0.05), but not by E64 (Figure 2B, 2C). No differences were observed between PI-IBS and IBS-C samples on effects on barrier function or the inhibition of that effect (n=3 each).

Role of PAR-2 inhibition on fecal supernatant induced loss of barrier function

FSN induced TER drop of Caco-2 monolayers was inhibited by ENMD1068, a selective PAR-2 antagonist {36.4 (11.1)% vs 67.6 (10.6)%, p<0.05, Figure 2B, 2C). At day 7, following transfection of Caco-2 cells with RNAi, 40% inhibition of PAR-2 protein was observed by western blot (Figure 2D). TER drop after addition of high PA FSNs from day 6 to day 7 was significantly lower in siPAR-2 Caco-2 cells compared to negative controls {55.2 (17.8)% vs 32.8 (21.9)% of the initial TER, p<0.05) (Figure 2E, 2F).

Effect of fecal supernatants on tight junction proteins

High PA FSN exposure to Caco-2 monolayers resulted in increased pMLC/MLC expression compared to low PA FSNs {1.55 (0.28) vs 0.68 (0.30), p<0.01]} Figure 3A, 3B). pMLC protein was upregulated and co-localized with phalloidin upon incubation with high PA compared to low PA FSN (Figure 3C). Isotype controls are shown (Supplementary Figure 5). Although the inhibitory effect of PAR-2 protein was ~40% by day 7, pMLC protein was still downregulated when high PA FSNs were added to siPAR-2 Caco-2 cells compared to negative control cells (Supplementary Figure 6).

Figure 3:

Effect of faecal supernatants on myosin light chain phosphorylation and occludin (A) pMLC/MLC protein expression following FSN incubation. High-PA FSNs caused significantly increased pMLC (20kDa) in Caco-2 cells compared to low PA FSNs. Red: target band; green: β-actin. (B) Quantitative changes in pMLC/MLC ratio. pMLC expression was significantly higher after high-PA FSNs application (n=5–6/group, p<0.01, Mann-Whitney U test). The protein bands were measured using densitometric quantitation with ImageJ software, normalised to β-actin. (C) pMLC localisation following FSN incubation. Immunofluorescence showing pMLC protein following high-PA and low-PA FSNs. pMLC colocalised with phalloidin staining. (D) Occludin protein expression following FSN incubation. High PA FSNs caused significantly decreased occludin protein (63kDa) in Caco-2 cells compared with low-PA FSNs. Red: target band; green: β-actin. (E) Quantitative changes in occludin protein. Occludin protein was significantly lower after high-PA FSNs application (n=5–6/group, p<0.05, Mann-Whitney U test). The protein bands were measured using densitometric quantitation with ImageJ software, normalised to β-actin. (F) Occludin localisation following FSN incubation. Immunofluorescence showing occludin following high-PA and low-PA FSNs. Occludin was internalised into cytoplasm from tight junction after high PA FSNs application. Scale bar=20μm. FSN, faecal supernatant; PA, proteolytic activity.

High PA FSNs caused a decrease in occludin protein in Caco-2 cells {0.39 (0.17) vs. 1 (0.09), p<0.05, Figure 3D, 3E}. Additionally, occludin was internalized into the cytoplasm from the tight junction(s) after high PA FSN application compared to low PA FSN (Figure 3F). AEBSF abolished internalization of occludin (Supplementary Figure 7). Expression of Claudin-2, a key regulator of pore pathway was unchanged upon exposure to high vs low PA FSN (Supplementary Figure 8).

Colonic biopsy samples of high PA and low PA IBS patients

Sigmoid colonic biopsies from high PA IBS patients had lower quantitative occludin protein expression {0.72 (0.03) vs 1 (0.13), p<0.05, Figure 4A, 4B) and decreased distribution at the tight junctions (Figure 4C) as compared to the biopsies from the low PA IBS patients. Transmission electron microscopy showed significantly wider tight junctions in high PA patient colonic biopsies (Figure 4D) compared to the low PA patients (Figure 4E) {Mean (SD); high PA 7.74 (1.28) nm, low PA 6.44 (0.58) nm, n=10 apical junction complexes/patient; 6 patients/group, p<0.05} (Figure 4F). In situ zymography done on a pilot set of high and low PA IBS patients did not reveal differences in trypsin-like tissue PA (Figure 4G).

Figure 4:

Occludin protein and tight junction structure in sigmoid colonic biopsies from patients with high-PA and low-PA IBS. (A) Occludin protein expression. Biopsies of high-PA patients showed decreased expression of occludin (63 kDa) compared with low-PA patients. Red: target band; green: β-actin. (B) Quantitative changes in occludin expression. Occludin expression was significantly lower in high-PA patients (n=4–5/group, p<.05, Mann-Whitney U test). The protein bands were measured using densitometric quantitation with ImageJ software, normalised to β-actin. (C) Occludin localisation. Immunofluorescence showing occludin in sigmoid colonic biopsies of high-PA and low-PA IBS patients. (D and E) Apical junction complex ultrastructure. Representative scanning electron microscopy images from a high-PA and low-PA IBS patient, respectively. (F) Quantitative comparison of tight junction intercellular distance. High-PA patients revealed greater intercellular space at TJ space than low-PA IBS (n=6/group, p<.05, Mann-Whitney U test). (G) In situ zymography showing trypsin-like PA in sigmoid colonic biopsies. No differences were seen between a pilot set of high and low PA IBS patients (n=3–4/group, p>0.05, Mann-Whitney U test). PA, proteolytic activity.

Microbiota composition of high PA and low PA IBS patients

High PA IBS patients demonstrated lower fecal diversity as compared to low PA IBS patients. Considering the higher proportion of PI-IBS phenotype in high PA group and the higher proportion of IBS-C in the low PA group, comparison was done after adjusting for IBS type. Alpha diversity metrics showed decreased microbial diversity in high PA IBS {observed (p<0.05), Shannon (p<0.01) and Inverse Simpson (p<0.05)} (Figure 5A–C). Beta diversity {unweighted UniFrac (p<0.05)} revealed an overall compositional difference in fecal microbiome between high PA and low PA IBS patients (Figure 5D). Since stool consistency has also been associated with fecal microbial diversity, we performed additional analysis adjusting for both IBS type as well as average Bristol stool scale. Although the significance level declined, high PA patients still had decreased alpha {observed OTUs (p < 0.1), Shannon (p < 0.01), Inverse Simpson (p < 0.05)} and beta diversity {Unweighted UniFrac (p < 0.1)} as compared to low PA patients.

Figure 5:

Microbiome composition of patients with high-PA and low-PA IBS. (A–C) Alpha diversity indices. Patients with high-PA IBS have lower microbial diversity than low-PA patients on observed operational taxonomic units (OTU), Shannon and Inverse Simpson tests (p<0.05). (D) Beta diversity index. Patients with high-PA IBS have different community structure than patients with low-PA IBS as shown by unweighted UniFrac analysis of beta diversity (p<0.05). PA, proteolytic activity.

Mice humanized with high PA, low PA and healthy microbiota

Mice humanized with healthy volunteer feces had 18.9 (23.9)% of PA of GF state retained, low PA PI-IBS feces had 22.2 (35.2)% of PA retained compared to 68 (116.5)% retained PA in mice humanized with high PA PI-IBS feces (p<0.05 for healthy vs high PA and low vs high PA) (Figure 6A, 6B). An inhibition of fecal PA from GF state was seen in a majority of the mice (65/72); however, a smaller subset of mice (7/72) had an increase in fecal PA from GF state. Mice humanized with fecal suspension from high PA PI-IBS patients showed a higher in vivo colonic permeability for creatinine 0.88 (0.28) mg/dL than those humanized with fecal suspension from low PA PI-IBS patients 0.54 (0.25) mg/dL or healthy volunteers 0.49 (0.34) mg/dL (p<0.05: healthy vs high PA, p=0.05 low vs high PA). No differences were seen in permeability of 4 kDa FITC-Dextran or 70 kDa RITC-Dextran (Figure 6C). The % of PA retained post-humanization correlated with excretion of creatinine but not with excretion of FITC-Dextran 4 kDa or RITC-Dextran 70 kDa (Figure 6D). Mice humanized with microbiota from the two high PA healthy volunteers showed ineffective suppression of fecal PA but no increase in intestinal permeability (Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 6:

Proteolytic activity and in vivo permeability changes in humanised mice. (A) Schematic showing humanisation of germ-free mice. Faecal slurry from healthy, patients with high-PA IBS and low-PA IBS were administered in 4-week-old germfree mice. PA assessment was done just at baseline (just prior to administering faecal slurry) and after 6 weeks (humanised state). In vivo permeability assessment was done in humanised state. (B) PA changes after humanisation. Lower inhibition from baseline (germ free) or increased production were seen in mice humanised with high PA as compared with healthy and low PA human stool (n=2129 mice/group, 3–4 donors/group, p<0.05, one-way analysis of variance [ANOVA]). Hollow symbols represent mice that were only used for PA assessment and not for in vivo permeability assessment. (C) In vivo permeability assessment in humanised mice. Greater permeability for creatinine in high-PA humanised mice was seen as compared with low-PA and healthy humanised mice (n=9–13 mice/group, 3–4 donors/group, p<0.05 healthy vs high PA and p=0.05 low vs high PA, one-way ANOVA with post hoc calculations). FITC-Dextran 4kDa and Rhodamine-Dextran 70 kDa permeability were similar in the three groups. (D) Correlations between PA changes and in vivo permeability. Creatinine permeability correlates with % PA change following humanisation (Spearman r=0.4, p<0.05). FITC-Dextran 4kDa and Rhodamine-Dextran 70 kDa permeability do not correlate with % PA change. PA, proteolytic activity.

DISCUSSION

This study provides evidence that intestinal proteases may mediate the effects of microbial dysbiosis on the pathophysiology of IBS. A subset of IBS patients has high PA which associates with in vivo and ex vivo barrier dysfunction and symptom severity. This high PA subset is much more common in PI-IBS (40%) than the IBS-C patient cohort (15%). Exposure to fecal contents from this subset (high PA) is disruptive to barrier function in vitro, and this effect can be blocked by serine protease inhibitors, but not cysteine protease inhibitors. The effect on barrier function appears to be mediated by the PAR-2 receptor and involves phosphorylation of MLC and loss and relocation of occludin from TJ to cytoplasm. This loss and internalization of occludin was also seen in biopsies of the high PA IBS subset. The high PA IBS subset has decreased microbial diversity and different community structure than the low PA IBS subset. Finally, humanization of germ-free mice with healthy volunteer or low PA PI-IBS stool results in significantly higher inhibition of fecal PA (from germ-free state) and lower intestinal permeability as compared to humanization with high PA PI-IBS patient stool. This suggests that the intestinal microbiota plays an important role in downregulating PA, and specific microbes in high PA patients may cause increased production or ineffective suppression of luminal proteases.

Previous studies have shown increased protease-like activity in fecal contents[18, 22, 40–42] and colonic biopsy supernatants from IBS patients.[16, 17, 19, 20] The effect of proteases on barrier function has been studied mostly in vitro (predominantly basolateral exposure) or in vivo in animal models upon application of exogenous proteases or biopsy supernatants from IBS patients. Repeated intracolonic infusion of IBS-C FSN increased in vivo permeability and occludin degradation in mice, both of which were inhibited by cysteine protease inhibitor E64.[18] Serine protease activity was significantly increased in the IBS-D cohort in this study but not in the IBS-C cohort. No data on barrier function in these patients was provided.[18] Another study showed elevated serine protease activity in IBS-D and intracolonic infusion using a mouse model resulting in allodynia and increased paracellular permeability which was dependent on mucosal expression of PAR-2. This was associated with MLC phosphorylation 1 h after intracolonic infusion, similar to infusion with PAR-2 agonist SLIGRL.[22] A recent study showed that addition of exogenous trypsin-3 to basolateral media of Caco-2 monolayers increased dextran flux and resulted in disorganization of TJ proteins.[2] TER and expression of TJ protein JAM-A in Caco-2 monolayers was reduced upon co-culture with mast cell line which could be inhibited with a tryptase inhibitor.[43] Elevated trypsin-like activity and lower occludin expression was seen in IBS colonic biopsies in another study.[44]

The current study shows that FSNs from both PI-IBS and IBS-C patients have an effect on barrier function which can be inhibited by serine but not a cysteine protease inhibitor. Considering increased in vitro flux of 3000 Da Texas Red Dextran (molecular radius 14 Å) and in vivo permeability of lactulose (molecular radius 5.4 Å), the PA likely affects the leak pathway of barrier function which is known to involve MLC phosphorylation and occludin internalization.[45, 46] This effect is partially mediated by PAR-2 receptors. Serine proteases can signal through PAR-1, 2 and 4 receptors.[1] In rats, dexamethasone treatment improves PAR-2 agonist induced visceral hypersensitivity but not the increase in colonic permeability.[47] Opposing actions on different PAR receptors with differential downstream effect on neuronal activation has been shown with IBS biopsy supernatants and PAR activating peptides.[17, 21] Our study using pharmacological-and si-inhibition of PAR-2 suggests its role in mediating the FSN effect as well and the complementary data that patients with high PA have greater in vivo and ex vivo permeability, decreased occludin expression and wider tight junctions on ultrastructural studies. Lack of inhibition of barrier effects by E-64, a specific inhibitor for cysteine proteases can be due to activation of epithelial PARs with serine but not cysteine proteases, differences in downstream signaling to barrier function between serine and cysteine proteases or lastly counter-protective effects by some of the proteases upon inhibition of cysteine proteases. Also, in our cohort 2/25 healthy volunteers had moderately high PA. Their FSNs also caused in vitro barrier disruption. In humanized mice, these microbes ineffectively suppressed proteases but the permeability was not increased. Small sample size of this cohort makes it hard to reach conclusions, however, it is possible that epithelial or other protective mechanisms may prevent downstream effects of luminal proteases.

The role of proteases in mediating visceral hypersensitivity has been extensively studied over the last decade, both upon administration in vivo in animals[18, 21, 22] and ex vivo on neuronal cultures.[16, 17, 19, 20, 48] Colonic mucosal biopsy supernatants were shown to activate human submucosal (mostly IBS-D patients) [19, 20] and thoracic sensory neurons (all IBS subtypes)[17] through PAR-1 activation. Clinically, both serine[43] and cysteine[18] protease activity have been correlated with abdominal pain. We found that patients with high PA have higher IBS symptom severity. Additionally, the frequency of bowel movements was higher and stool consistency was looser in the high PA PI-IBS group. Although a previous study has debated whether it is the faster transit through the colon that results in greater fecal PA,[42] we found no correlations between colonic transit measured using scintigraphy and fecal PA.

Both pancreatic[42] and colonic epithelial[2] origin of proteases has been shown to associate with IBS. Specific ELISA assays in a cohort of IBS-D patients did not reveal activity to originate from trypsin, pancreatic elastase 1 or neutrophil derived elastase. Additionally, the expression of SLPI was not changed.[22] Similarly, another study also did not find differences in mast cell tryptase, pancreatic elastase-1 or SLPI levels.[41] Fecal protease activity has been associated with compositional differences in microbiota.[40] Recently, serine proteases from commensal microbiota, especially Faecalibacterium prausnitzii were shown to suppress excitability of DRG neuron via the PAR-4 receptor.[49] The origin of the PA observed in our patients and in the previous studies remains unclear. Although, epithelium and lamina propria can be important source of proteases, their contribution towards luminal proteases is unclear. In our pilot experiments, although some IBS patients had high tissue PA, the overall tissue trypsin-like tissue PA was similar between the high and low PA IBS subjects. Transit of contents through the colon lowers PA in majority of the mice (65/72). However, mice humanized with high PA associated microbiota either showed an ineffective inhibition or in some cases, an increase in fecal PA compared to GF state. This supports a predominantly inhibitory role of microbiota on PA[13] which could be due to secretion of protease inhibitors like elafin,[50] siropins,[51] alpha-2 macroglobulin,[52] and miropins.[53] However, microbial production of proteases is also possible,[5, 54, 55] which in some cases like Enterococcus faecalis produced gelatinase, can disrupt barrier function.[4] Recently, non-ribosomal gene clusters, present in 88% of samples from the human microbiome project, were found to secrete small molecules with protease inhibitory properties.[56] Reduced levels of protease inhibitors have been seen in patients with celiac disease[9] and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).[11] Host polymorphisms in ubiquitin proteasome system genes have been associated with the risk of IBD.[57] This is relevant considering that both microbiota based[58] and non-microbiota[59, 60] based inhibition of protease activity has been investigated. We also showed that intestinal permeability is higher in mice humanized with high PA stool suggesting that microbiota may regulate intestinal permeability via ineffective inhibition or production of specific intestinal proteases. A limitation of the current study is the sample size which did not allow us to delineate specific microbiota changes in high and low PA patients. Subsequently, metagenomic, metatranscriptomic and metaproteomics approaches are needed to further characterize the fecal microbiota, protease profiles and activity. Such studies will also be able to determine the identity of proteases and protease inhibitors that may be differentially regulated in response to various microbial communities.

In conclusion, this study provides comprehensive human in vivo, ex vivo and in vitro evidence for serine proteases in mediating barrier dysfunction and symptom severity in IBS, especially post infection IBS. The fecal protease activity associated with changes in microbiota composition. Intestinal proteases may therefore mediate the effects of microbial dysbiosis on the pathophysiology of IBS. Further studies will be needed to expand our understanding of the specific proteases involved and the effects of PA modulation.

Supplementary Material

Significance of this Study.

- What is already known about this subject?

- Proteases are increased in a subset of IBS patients in fecal and tissue supernatants.

- Proteases play a role in development of visceral hypersensitivity in animal models.

- Proteases disrupt barrier function in vitro and in vivo in animal models.

- What are the new findings?

- 40% post infection IBS patients have elevated fecal proteolytic activity (PA).

- Serine proteases in fecal supernatants disrupt barrier through PAR-2 mediated signaling, myosin light chain phosphorylation and loss of occludin.

- Patients with high fecal PA have greater diarrhea, worse symptom severity, increased permeability (in vivo and ex vivo) and wider tight junctions on ultrastructure.

- Patients with high fecal PA have decreased fecal microbial diversity.

- Transfer of feces into germ-free mice (humanization) results modulates fecal PA suggesting microbial influence on regulation of proteases.

- Humanization using high PA feces results in ineffective suppression of PA and greater intestinal permeability suggesting proteases may mediate the effects of microbial dysbiosis on pathophysiology of PI-IBS.

- How might it impact on clinical practice in the foreseeable future?

- Increased fecal PA associates with a unique subset of IBS patients with increased intestinal permeability and reduced fecal microbial diversity.

- Identifying and supplementing microbiota with protease inhibitory properties might prevent or reverse barrier dysfunction in PI-IBS.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Grant Support: This project was funded by NIDDK K23 DK103911 to Dr. Madhusudan Grover. Dr. Jun Chen is supported by Mayo Clinic Center for Individualized Medicine.

Acknowledgement: The authors wish to thank Ms. Lori Anderson for administrative assistance.

Disclosures: MG has served on the advisory board or received research support from Takeda, DongA, Ironwood and Napo. Nothing to disclose for other authors.

Abbreviations:

- TJ

tight junctions

- HADS

hospital anxiety and depression scale

- MLC

myosin light chain

- OTUs

operational taxonomic units

- PAR

protease activated receptor

- FSN

fecal supernatant

- PA

Proteolytic activity

- PI-IBS

Post-infection irritable bowel syndrome

REFERENCES

- 1.Vergnolle N Protease inhibition as new therapeutic strategy for GI diseases. Gut 2016;65(7):1215–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rolland-Fourcade C, Denadai-Souza A, Cirillo C, et al. Epithelial expression and function of trypsin-3 in irritable bowel syndrome. Gut 2017;66(10):1767–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biancheri P, Di Sabatino A, Corazza GR, et al. Proteases and the gut barrier. Cell Tissue Res 2013;351(2):269–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maharshak N, Huh EY, Paiboonrungruang C, et al. Enterococcus faecalis gelatinase mediates intestinal permeability via protease-activated receptor 2. Infect Immun 2015;83(7):2762–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rao MB, Tanksale AM, Ghatge MS, et al. Molecular and biotechnological aspects of microbial proteases. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 1998;62(3):597–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pruteanu M, Hyland NP, Clarke DJ, et al. Degradation of the extracellular matrix components by bacterial-derived metalloproteases: implications for inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2011;17(5):1189–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shen W, Matsui T. Current knowledge of intestinal absorption of bioactive peptides. Food Funct 2017;8(12):4306–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rawlings ND, Barrett AJ, Thomas PD, et al. The MEROPS database of proteolytic enzymes, their substrates and inhibitors in 2017 and a comparison with peptidases in the PANTHER database. Nucleic Acids Res 2018;46(D1):D624–D32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galipeau HJ, Wiepjes M, Motta JP, et al. Novel role of the serine protease inhibitor elafin in gluten-related disorders. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109(5):748–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Motta JP, Magne L, Descamps D, et al. Modifying the protease, antiprotease pattern by elafin overexpression protects mice from colitis. Gastroenterology 2011;140(4):1272–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmid M, Fellermann K, Fritz P, et al. Attenuated induction of epithelial and leukocyte serine antiproteases elafin and secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor in Crohn’s disease. J Leukoc Biol 2007;81(4):907–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Macfarlane GT, Allison C, Gibson SA, et al. Contribution of the microflora to proteolysis in the human large intestine. J Appl Bacteriol 1988;64(1):37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gibson SA, McFarlan C, Hay S, et al. Significance of microflora in proteolysis in the colon. Appl Environ Microbiol 1989;55(3):679–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Genell S, Gustafsson BE, Ohlsson K. Immunochemical quanitation of pancreatic endopeptidases in the intestinal contents of germfree and conventional rats. Scand J Gastroenterol 1977;12(7):811–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Genell S, Gustafsson BE. Impaired enteric degradation of pancreatic endopeptidases in antibiotic-treated rats. Scand J Gastroenterol 1977;12(7):801–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cenac N, Andrews CN, Holzhausen M, et al. Role for protease activity in visceral pain in irritable bowel syndrome. J Clin Invest 2007;117(3):636–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Desormeaux C, Bautzova T, Garcia-Caraballo S, et al. Protease-activated receptor 1 is implicated in irritable bowel syndrome mediators-induced signalling to thoracic human sensory neurons. Pain 2018;159(7):1257–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Annahazi A, Ferrier L, Bezirard V, et al. Luminal cysteine-proteases degrade colonic tight junction structure and are responsible for abdominal pain in constipation-predominant IBS. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108(8):1322–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buhner S, Hahne H, Hartwig K, et al. Protease signaling through protease activated receptor 1 mediate nerve activation by mucosal supernatants from irritable bowel syndrome but not from ulcerative colitis patients. PLoS One 2018;13(3):e0193943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buhner S, Li Q, Vignali S, et al. Activation of human enteric neurons by supernatants of colonic biopsy specimens from patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2009;137(4):1425–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Annahazi A, Gecse K, Dabek M, et al. Fecal proteases from diarrheic-IBS and ulcerative colitis patients exert opposite effect on visceral sensitivity in mice. Pain 2009;144(1–2):209–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gecse K, Roka R, Ferrier L, et al. Increased faecal serine protease activity in diarrhoeic IBS patients: a colonic lumenal factor impairing colonic permeability and sensitivity. Gut 2008;57(5):591–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ibeakanma C, Ochoa-Cortes F, Miranda-Morales M, et al. Brain-gut interactions increase peripheral nociceptive signaling in mice with postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2011;141(6):2098–108 e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klem F, Wadhwa A, Prokop LJ, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and outcomes of irritable bowel syndrome after infectious enteritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2017;152(5):1042–54 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grover M, Camilleri M, Smith K, et al. On the fiftieth anniversary. Postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome: mechanisms related to pathogens. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2014;26(2):156–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Evnin LB, Vasquez JR, Craik CS. Substrate specificity of trypsin investigated by using a genetic selection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990;87(17):6659–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DelMar EG, Largman C, Brodrick JW, et al. A sensitive new substrate for chymotrypsin. Anal Biochem 1979;99(2):316–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Edwards JV, Prevost NT, French AD, et al. Kinetic and structural analysis of fluorescent peptides on cotton cellulose nanocrystals as elastase sensors. Carbohydr Polym 2015;116:278–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sabotic J, Bleuler-Martinez S, Renko M, et al. Structural basis of trypsin inhibition and entomotoxicity of cospin, serine protease inhibitor involved in defense of Coprinopsis cinerea fruiting bodies. J Biol Chem 2012;287(6):3898–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morita T, Kato H, Iwanaga S, et al. New fluorogenic substrates for alpha-thrombin, factor Xa, kallikreins, and urokinase. J Biochem 1977;82(5):1495–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ceuleers H, Hanning N, Heirbaut J, et al. Newly developed serine protease inhibitors decrease visceral hypersensitivity in a post-inflammatory rat model for irritable bowel syndrome. Br J Pharmacol 2018;175(17):3516–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Denadai-Souza A, Bonnart C, Tapias NS, et al. Functional proteomic profiling of secreted serine proteases in health and inflammatory bowel disease. Sci Rep 2018;8(1):7834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Edgington-Mitchell LE, Barlow N, Aurelio L, et al. Fluorescent diphenylphosphonate-based probes for detection of serine protease activity during inflammation. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2017;27(2):254–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wegener J, Abrams D, Willenbrink W, et al. Automated multi-well device to measure transepithelial electrical resistances under physiological conditions. Biotechniques 2004;37(4):590, 92,–4, 96–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grover M, Camilleri M, Hines J, et al. (13) C mannitol as a novel biomarker for measurement of intestinal permeability. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2016;28(7):1114–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Szarka LA, Camilleri M. Methods for the assessment of small-bowel and colonic transit. Semin Nucl Med 2012;42(2):113–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsai PY, Zhang B, He WQ, et al. IL-22 upregulates epithelial claudin-2 to drive diarrhea and enteric pathogen clearance. Cell Host Microbe 2017;21(6):671–81 e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baldwin EA, Walther-Antonio M, MacLean AM, et al. Persistent microbial dysbiosis in preterm premature rupture of membranes from onset until delivery. PeerJ 2015;3:e1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jeraldo P, Kalari K, Chen X, et al. IM-TORNADO: a tool for comparison of 16S reads from paired-end libraries. PLoS One 2014;9(12):e114804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carroll IM, Ringel-Kulka T, Ferrier L, et al. Fecal protease activity is associated with compositional alterations in the intestinal microbiota. PLoS One 2013;8(10):e78017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roka R, Rosztoczy A, Leveque M, et al. A pilot study of fecal serine-protease activity: a pathophysiologic factor in diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;5(5):550–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tooth D, Garsed K, Singh G, et al. Characterisation of faecal protease activity in irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhoea: origin and effect of gut transit. Gut 2014;63(5):753–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilcz-Villega EM, McClean S, O’Sullivan MA. Mast cell tryptase reduces junctional adhesion molecule-A (JAM-A) expression in intestinal epithelial cells: implications for the mechanisms of barrier dysfunction in irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108(7):1140–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Coeffier M, Gloro R, Boukhettala N, et al. Increased proteasome-mediated degradation of occludin in irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 2010;105(5):1181–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weber CR, Raleigh DR, Su L, et al. Epithelial myosin light chain kinase activation induces mucosal interleukin-13 expression to alter tight junction ion selectivity. J Biol Chem 2010;285(16):12037–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shen L, Weber CR, Raleigh DR, et al. Tight junction pore and leak pathways: a dynamic duo. Annu Rev Physiol 2011;73:283–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roka R, Ait-Belgnaoui A, Salvador-Cartier C, et al. Dexamethasone prevents visceral hyperalgesia but not colonic permeability increase induced by luminal protease-activated receptor-2 agonist in rats. Gut 2007;56(8):1072–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reed DE, Barajas-Lopez C, Cottrell G, et al. Mast cell tryptase and proteinase-activated receptor 2 induce hyperexcitability of guinea-pig submucosal neurons. J Physiol 2003;547(Pt 2):531–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sessenwein JL, Baker CC, Pradhananga S, et al. Protease-Mediated Suppression of DRG Neuron Excitability by Commensal Bacteria. J Neurosci 2017;37(48):11758–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McCarville JL, Dong J, Caminero A, et al. A commensal Bifidobacterium longum strain improves gluten-related immunopathology in mice through expression of a serine protease inhibitor. Appl Environ Microbiol 2017. August 4 pii: AEM.01323–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mkaouar H, Akermi N, Mariaule V, et al. Siropins, novel serine protease inhibitors from gut microbiota acting on human proteases involved in inflammatory bowel diseases. Microb Cell Fact 2016;15(1):201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Garcia-Ferrer I, Arede P, Gomez-Blanco J, et al. Structural and functional insights into Escherichia coli alpha2-macroglobulin endopeptidase snap-trap inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2015;112(27):8290–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Goulas T, Ksiazek M, Garcia-Ferrer I, et al. A structure-derived snap-trap mechanism of a multispecific serpin from the dysbiotic human oral microbiome. J Biol Chem 2017;292(26):10883–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gibson SA, Macfarlane GT. Characterization of proteases formed by Bacteroides fragilis. J Gen Microbiol 1988;134(8):2231–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thornton RF, Murphy EC, Kagawa TF, et al. The effect of environmental conditions on expression of Bacteroides fragilis and Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron C10 protease genes. BMC Microbiol 2012;12:190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Guo CJ, Chang FY, Wyche TP, et al. Discovery of reactive microbiota-derived metabolites that inhibit host proteases. Cell 2017;168(3):517–26 e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cleynen I, Vazeille E, Artieda M, et al. Genetic and microbial factors modulating the ubiquitin proteasome system in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 2014;63(8):1265–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Motta JP, Bermudez-Humaran LG, Deraison C, et al. Food-grade bacteria expressing elafin protect against inflammation and restore colon homeostasis. Sci Transl Med 2012;4(158):158ra44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kobayashi H Prevention of cancer and inflammation by soybean protease inhibitors. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2013;5:966–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.De Santis S, Galleggiante V, Scandiffio L, et al. Secretory leukoprotease inhibitor (Slpi) expression is required for educating murine dendritic cells inflammatory response following quercetin exposure. Nutrients 2017;9(7) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.