Abstract

Priming is one of the mechanisms for the induction of the antioxidant defense system and various stress-responsive proteins which help plants to survive under various abiotic stresses. Based on the observation that the rice seedlings primed with UV-B (low dose of UV-B irradiation—6 kJm−2) induced the acclimation against NaCl, PEG and UV-B stresses, it was of interest to see the augmentation of antioxidative potential and stress-responsive proteins accumulation in rice seedlings due to UV-B priming under these stresses. Various stresses result in production of ROS, which cause membrane degradation resulting in the accumulation of malondialdehyde. These negative impacts were observed exceedingly in rice seedlings from non-primed PEG stress (NP+P) condition than UV-B and NaCl stresses. The production of non-enzymatic antioxidants, activity/mRNA-level expressions of enzymatic antioxidants and stress-responsive proteins were effectively augmented in UV-B-primed rice seedlings subjected to NaCl stress (P+N) condition followed by UV-B stress (P+U) and PEG stress (P+P). The activation of stress-responsive proteins (HSP and LEA) in rice due to the UV-B priming of rice seedlings is being reported for the first time. The results revealed that the UV-B seedling priming was alleviating the effect of NaCl, PEG, and UV-B stresses in rice seedlings. The positive impacts of UV-B seedling priming were more prominent in rice seedlings subjected to NaCl stress, indicating the cross tolerance imparted by UV-B priming.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13205-019-1903-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Seedling priming, Rice, Reactive oxygen species, Antioxidants, UV-B, Stress-responsive proteins

Introduction

Rice is one of the most important food crops that feeds over half of the world population. Majority of the people in Asia, Africa, and South America use rice and its derived products as their chief food source. To meet the demand of the increasing population, rice production has to be increased by at least 70% by 2050. Rice production is being encountered with various abiotic stress conditions which negatively influence their production rate (Chunthaburee et al. 2016; Bergman 2019).

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation is the preliminary responses of plant cells to abiotic stresses and these disrupt different metabolic processes. ROS like singlet oxygen, superoxide radicals, hydrogen peroxide and hydroxyl radicals are reactive forms of molecular oxygen (Czarnocka and Karpinski 2018). The ROS accumulation is injurious to plant cells and at the same time plays a key role in signaling pathways that regulate acclamatory and defense mechanisms in crop plants. ROS production results in chlorophyll degradation and membrane lipid peroxidation, reduces membrane fluidity and selectivity. Over-produced ROS cause oxidative damages and destruction of plant macromolecules, cell structures and also disturb the redox homeostasis equilibrium which leads to induced cell death and ultimately leads to yield reduction and plant death (Czarnocka and Karpinski 2018). Highly sophisticated antioxidant systems are developed in plants to scavenge the ROS and thus develop tolerance against various abiotic stresses. To stabilize the detrimental influence of ROS, plant cells have evolved protection systems containing enzymatic antioxidants (peroxidase, superoxide dismutase, and catalase) and non-enzymatic antioxidants (glutathione, GSH; ascorbic acid, AsA).

Various abiotic stresses such as low temperature, salinity, desiccation, high-intensity irradiations, wounding, and heavy metals stresses induce the production of stress-induced proteins such as heat-shock proteins (HSPs) and Late Embryogenesis Abundant (LEA) proteins (Al-Whaibi 2011; Battaglia and Covarrubias 2013). The main role of HSPs is to act as molecular chaperones, which regulate the folding and accumulation of proteins as well as localization and degradation in plants. Other than acting as molecular chaperons, Hsp90 has a role in signaling function and trafficking and regulating cellular signals such as the regulation of glucocorticoid receptor (GR) activity (Al-Whaibi 2011).

LEA proteins reduce the damage and protect the cells from various stresses. Abiotic stress protection strategies of LEA proteins include hydration buffering, metal ion binding, antioxidant activity, membrane stabilization and DNA and RNA interactions (Zeng et al. 2018). LEA proteins also can stabilize cell structure, preventing inactivation and aggregation of proteins and the loss of the membranes integrity (Lutts et al. 2016).

Researchers are adopting different methods to cope up with the tolerance towards various stresses. Priming with seeds and seedlings is one of the most adaptable and effective strategies to enhance uniform germination, high seedling vigor, and better yields in crop plants under various environmental stress conditions. Priming causes biochemical, physiological, molecular, and genetic changes such as the accumulation of latent signaling components that will be utilized during a re-exposure to a stress. These modifications of molecular mechanisms allow the plants to memorize previous priming events and thus generate memory imprints during further exposure to stress. Priming activates DNA repair pathways and antioxidant mechanisms and ensures appropriate seedling development and tolerance towards stress conditions (Hussain et al. 2016). In several species, priming induces HSP production, which stabilizes protein and membrane structures (Chen and Arora 2013). Different seed-priming treatments alter the expression/accumulation of LEA transcript/protein in association with stress-tolerance mechanisms (Chen et al. 2012; Kubala et al. 2015).

Researchers have also reported the role of different types of UV radiation (in low dose) in seed and seedling priming and their positive effects in stress-tolerance mechanisms (Dillon et al. 2018; Thomas and Puthur 2019; Xu et al. 2019). Very few studies are under taken in the area of priming the seeds/seedlings with UV-B irradiation leading to stress tolerance in rice (Thomas and Puthur 2017). In this study, the potential of the UV-B-primed rice seedlings in encountering salinity, drought, and UV-B stresses is examined on the basis of antioxidative potential and prominent stress-responsive proteins such as HSP and LEA.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

Rice (Oryza sativa L.), var. Kanchana was selected for this study. The rice seeds were collected from Regional Rice Research station, Pattambi, Kerala, India.

Seedling priming techniques

For the surface sterilization, the seeds were treated with 0.1% HgCl2 solution for 5 min, and further washed thoroughly with distilled water. After washing, the seeds were germinated in Petri-dishes layered with germination paper and wetted with distilled water. For seedling priming, the 4 days-old seedlings were exposed to low dose of UV-B (6 kJm−2). The primed and non-primed seedlings were transferred to plastic bottles (22 × 12 cm) containing cotton soaked with one of the following (a) distilled water, (b) NaCl (100 mM) and (c) PEG-6000 (20%). The bottles were kept under a 14/10 h light–dark cycles at 300 μmol m−2 s−1, 25 ± 3 °C and RH 55 ± 5%. For UV-B stress, UV-B irradiation (28 kJm−2 d−1) in addition to continuous white fluorescent illumination of 300 μmol m−2 s−1 was given with the aid of mobile adjustable frames over the plants. The biologically effective UV-B (UV-BBE) was gained through normalization at 300 nm; calculation of the same was done according to Caldwell (1971). The UV-B intensity was measured using radiometer (UV-B irradiation meter, RM-12, Opsytec Dr. Grobel). The UV-B tubes were covered with 0.13-mm thick cellulose diacetate filters to avoid transmission of wave lengths below 280 nm. Further physiological, biochemical, and molecular analyses were done in rice seedlings emerging from UV-B-primed seedlings (P) and non-primed seedlings (NP) after 9 days of growth.

Estimation of malondialdehyde, superoxide, and hydrogen peroxide contents

As per the method of Heath and Packer (1968), the malondialdehyde (MDA) content in rice seedlings was analyzed and its molar extinction coefficient of 155 mM−1 cm−1 was used for calculation. Hydrogen peroxide content was measured according to the procedure of Junglee et al. (2014) and the standard used was hydrogen peroxide. Superoxide content was estimated as per the procedure of Doke (1983) and sodium nitrate was used as standard.

Membrane stability index and electrolyte leakage percentage

Membrane stability index (MSI) was estimated as described by Sairam et al. (1997). Electrolyte leakage (EL%) was estimated as described by Lutts et al. (1996) with modifications.

Quantification of non-enzymatic and enzymatic antioxidants

Proline content in the plant parts was estimated according to the method of Bates et al. (1973) and l-proline was used for preparing the standard curve. Total phenolics content was estimated using Folin–Denis reagent according to the method of Folin and Denis (1915) and standard curve was prepared using catechol.

Ascorbate and glutathione contents were estimated according to Chen and Wang (2002) and l-ascorbic acid and reduced glutathione were, respectively, used for preparing the standard curve.

From fresh seedlings, the crude enzyme extract was prepared as described by the procedure of Yin et al. (2009). Protein estimation in the enzyme extract was done by the method of Bradford (1976) and BSA was used as standard. APX (EC 1.11.1.11) activity was recorded as per Nakano and Asada (1981). SOD (EC 1.15.1.1) activity was analyzed by the procedure of Giannopolitis and Ries (1977). The CAT (EC 1.11.1.6) in the fresh samples was measured by following the method of Kar and Mishra (1976).

Gene expression analysis of enzymatic antioxidants and stress-responsive proteins

Total RNA was extracted as per the protocol of Valenzuela-Avendañ et al. (2005), from non-primed and primed rice seedlings. Using Nano Drop spectrophotometer (Jenway, Genova Nano) and agarose gel electrophoresis, the RNA concentration and integrity were checked. From RNA, the first strand of cDNAs was synthesized according to manufacturer’s instruction of iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad). Using the primer-3 software, primers for SOD (Cu/Zn SOD), CAT (CatA), APX (APx1), HSP (Hsp90), LEA (group3) and actin (internal control) were designed (Supplementary Table) and the RT-PCR was performed using Bio-Rad Thermo cycler (C1000). Differential expression of the genes was analyzed by running the PCR products in 1% agarose gel followed by measuring the band intensities using ImageJ program.

Statistical analysis

According to Duncan’s test (P ≤ 0.05) the statistical analysis of the data was done. The data were average of three separate experimental observations with three replicates (i.e., n = 9). The data denote mean ± standard error (SE). One-way ANOVA was applied using the SPSS software (Version 16.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA) to evaluate the significant difference among UV-B-primed rice seedlings exposed to various stress conditions.

Results

ROS production and related cellular changes

Exposure of non-primed rice seedlings (NP) to NaCl, UV-B, and PEG stresses significantly increased the superoxide and hydrogen peroxide content in them. The increases were maximum in PEG stress condition, i.e., 57% increase of superoxide and 196% increase of hydrogen peroxide content over the control. However, the priming treatments of rice seedlings with UV-B significantly assuaged the damaging effects of all three stress conditions. Compared with control plant, the superoxide and hydrogen peroxide contents were increased in primed stressed condition but the increases were not as high as in seedlings of non-primed stressed condition. The least increment of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide content (10–30%) was observed in UV-B-primed seedlings subjected to NaCl stress condition. Even the control plants had a noticeable level of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide content and in primed unstressed rice seedlings, the level of these ROS was reduced as compared to control (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Superoxide and hydrogen peroxide (a), MDA content (b), electrolyte leakage (c) and membrane stability index (d) in seedlings from UV-B-primed and non-primed seedlings with UV-B and subjected to various stress conditions (NaCl, PEG and UV-B). (P+C-Primed+Control; P+N-Primed+NaCl; P+P-Primed+PEG; P+U-Primed+UV-B)

In non-primed stressed state, the MDA content and electrolyte leakage were significantly increased, and that was highest in PEG stress condition, i.e., about 119 and 30%, respectively, higher over the control. Compared with non-primed stressed condition, the MDA content and electrolyte leakage were reduced in primed stressed condition but at the same time it was increased as compared with the control. The increment of MDA content and electrolyte leakage was recorded least in primed seedlings subjected to NaCl stress (P+N) condition. As compared with control, reduced MDA content and electrolyte leakage were observed in primed unstressed condition and the rate of reduction was 42 and 16%, respectively (Fig. 1).

The three stress conditions were found to hamper the membrane stability in rice seedlings. Compared with control, the membrane stability index (MSI) in seedlings subjected to NaCl, UV-B and PEG stresses was reduced by 14, 20, and 26%, respectively. An insignificant reduction of MSI was observed in all primed stressed conditions as compared to control. Nevertheless, in primed unstressed state there was slight increment of MSI (Fig. 1).

Antioxidants content/activities

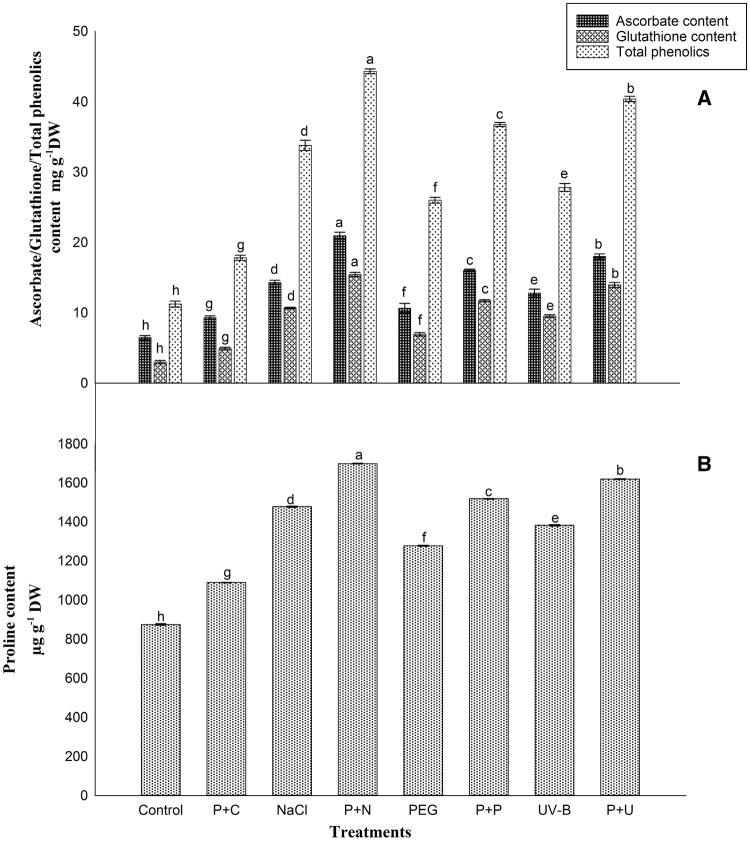

Proline and total phenolics contents were increased in primed stressed seedlings. The effects of UV-B priming were most effectively observed in P+N (Primed+NaCl) based on higher accumulation of proline and total phenolics content and it was about 92 and 350%, respectively, higher over the control and it was higher when compared with other primed stressed conditions such as P+U (Primed+UV-B) and P+P (Primed+PEG). The accumulation of above metabolites/antioxidants in non-primed stressed seedlings was increased than the control but was at a reduced rate than in the primed stressed seedlings. The increases of these metabolites were least in non-primed PEG stress seedlings and it was only 44 and 121%, respectively, over the control. In the case of primed unstressed seedlings, negligible increase of proline and total phenolics content was observed as compared to control (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Ascorbate, glutathione, total phenolics (a) and proline (b) content in seedlings from UV-B-primed and non-primed seedlings with UV-B and subjected to various stress conditions (NaCl, PEG and UV-B). (P+C-Primed+Control; P+N-Primed+NaCl; P+P-Primed+PEG; P+U-Primed+UV-B)

Compared with the control, ascorbate and glutathione contents were also significantly enhanced in seedlings subjected to primed stressed conditions. The increment was maximum in seedlings of P+N condition than other primed stressed states and it was about 224 and 417%, respectively, higher over the control. However, in non-primed stressed conditions, the ascorbate and glutathione contents were increased as compared with control but compared with primed stressed condition it was less. The increases of ascorbate and glutathione content were less in PEG stress condition than UV-B and NaCl stress; it was about 65 and 133%, respectively. In the case of primed unstressed rice seedlings, the ascorbate and glutathione contents were also slightly increased over the control (Fig. 2).

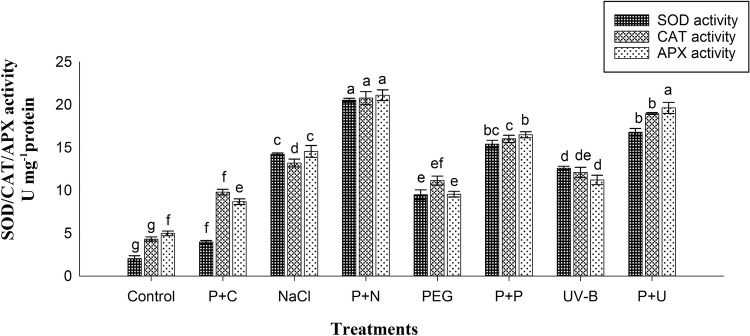

The enzymatic antioxidant activities and gene expressions of these enzymes were significantly enhanced in primed stressed condition than stressed condition. The higher activities and mRNA level expression of SOD, CAT, and APX were seen in P+N state and the increase was 896, 380, and 322% of enzyme activities and 98, 369 and 405% of gene expression levels, respectively, over the control. Non-primed seedlings subjected to PEG stress showed lowest increment of SOD, CAT, and APX activities (361, 158, and 91%, respectively) and mRNA expression levels (32, 140, and 122%, respectively) than other stresses (NaCl and UV-B) as compared to the control. Very less level of increment in SOD, CAT, and APX activities was observed in primed unstressed condition over the control (Figs. 3, 4).

Fig. 3.

SOD, CAT, and APX activities in seedlings from UV-B-primed and non-primed seedlings with UV-B and subjected to various stress conditions (NaCl, PEG, and UV-B). (P+C-Primed+Control; P+N-Primed+NaCl; P+P-Primed+PEG; P+U-Primed+UV-B)

Fig. 4.

mRNA level expression of SOD, CAT, and APX gene in seedlings from UV-B-primed and non-primed seedlings with UV-B and subjected to various stress conditions (NaCl, PEG, and UV-B). (P+C-Primed+Control; P+N-Primed+NaCl; P+P-Primed+PEG; P+U-Primed+UV-B)

Gene expression of stress-responsive proteins

Gene expression at mRNA level was significantly enhanced in the case of stress-responsive proteins such as HSP and LEA proteins in primed stressed conditions. Remarkable enhancement in gene expression level was recorded in UV-B-primed seedlings subjected to UV-B stress (369%) and the increase in P+N and P+P was only 161 and 140%, respectively. Moderate enhancement of HSP gene expression was noticed in non-primed NaCl (NP+N) and PEG (NP+P) stressed condition but in the NP+U condition seedlings exhibited 251% increase. In the case of LEA proteins, an incredible increase of gene expression was noticed in PEG stress conditions than NaCl and UV-B stress. The highest expression was observed in P+P and NP+P, i.e., 528 and 396%, respectively, than control. Although in P+N and P+U there was enhancement of LEA protein gene expression, it was 293 and 220% only. The enhancement in LEA protein gene expression in non-primed stressed condition was at a moderate level. An insignificant enhancement of HSP and LEA proteins was noted in primed unstressed condition than the control (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

mRNA level expression of HSP and LEA gene in seedlings from UV-B-primed and non-primed seedlings with UV-B and subjected to various stress conditions (NaCl, PEG and UV-B). (P+C-Primed+Control; P+N-Primed+NaCl; P+P-Primed+PEG; P+U-Primed+UV-B)

Discussion

NaCl, PEG, and UV-B are the major abiotic stresses which negatively influence the growth and productivity of crop plants. The present study revealed that exposure of non-primed rice seedlings to these stresses led to higher accumulation of ROS such as hydrogen peroxide and superoxide content. In general, PEG and salinity stresses damage the plant tissues by the effect of over-accumulated ROS, owing to ion imbalance and hyperosmotic stresses. Over production of ROS was a major indicator of the oxidative stress in rice seedlings. The ROS over production negatively affects the stability of cell membranes which results in the production of MDA content via the lipid peroxidation and followed by electrolyte leakage in seedlings. The phenomenon of oxidative injury modifies the structures of the membranes by the lipid peroxidation resulting in electrolyte leakage and ultimately results in loss of cell viability (Espanany et al. 2016; Chunthaburee et al. 2016; Choudhury et al. 2017). Lipid peroxidation is an ascribed symptom to oxidative damage and it is used as a maker of oxidative stress (Taïbi et al. 2016). MDA is the main cytotoxic product of lipid peroxidation and is a major indicator of free radical production (Espanany et al. 2016).

In rice seedlings subjected to primed stressed conditions, the hydrogen peroxide and superoxide contents were reduced which was seen to be directly proportionate to the reduced MDA content and electrolyte leakage in rice seedlings. These reductions point out that the stress-induced oxidative damages were effectively alleviated by priming of the rice seedlings with UV-B. Previous researchers have concluded that the positive effects of various seed priming treatments under various abiotic stresses occur presumably due to the protection against oxidative damages (Abid et al. 2018; Dillon et al. 2018). Similar positive effects were reported as a result of seed priming with low dose of UV radiation and the positive effects include averting lipid peroxidation, electrolyte leakage and ROS production as noted in maize (Javadmanesh et al. 2012), black cumin (Espanany et al. 2016) and rice (Hussain et al. 2016; Thomas and Puthur 2019). The effect of seedling priming with UV-B, assuaging the rate of lipid peroxidation, electrolyte leakage and ROS production were effectively observed in primed seedlings subjected to NaCl stress followed by UV-B and PEG. The effective tolerance in the case of rice seedlings subjected to P+N highly activated antioxidant defense system than that observed in P+U and P+P conditions.

Accumulation of proline is a well-known strategy adopted by plants to cope with drought or salinity stress. It also takes a key role in protecting the sub-cellular structures and arbitrating osmotic adjustment in stressed conditions. In addition, it plays an adaptive role like protection of cellular functions by scavenging ROS, acting as storage form of carbon to supply energy required during recovery from stress and also acts as a signal molecule regulating reproductive development (Chunthaburee et al. 2016). Moreover, under stressed conditions proline acts as osmolyte, signaling molecule and antioxidative defense molecule and its accumulation promotes plant damage repair by increasing antioxidant activity (Pandey and Shukla 2015). Phenolic compounds take multiple roles in plants such as structural components of cell walls, involved in the modulation of growth and developmental processes as well as in the mechanisms of defense against abiotic stresses (Taïbi et al. 2016).

Both these metabolites are highly accumulated in plants in response to stress tolerance/adaptive mechanism. UV-B priming significantly enhances the proline and total phenolics contents so as to cope up with various stresses. Higher accumulation of these metabolites was noted in primed seedlings subjected to stress condition than non-primed seedlings exposed to different stresses. Of these different stresses, the enhanced accumulation of these metabolites/non-enzymatic antioxidants was seen in P+N condition and this is a clear cut evidence that UV-B priming has the potential to exhibit cross tolerance effect, i.e., UV-B priming of rice seedlings imparting greater tolerance to NaCl stress than other two stresses. Similar to our observations enhanced accumulation of proline and total phenolics was reported in seedlings of various plants as a result of different means of seed priming (Espanany et al. 2016).

The increased level of antioxidant capacity confers the ability of plants to scavenge ROS and to withstand the NaCl, PEG, and UV-B stresses. The protective role of ascorbate, glutathione, SOD, CAT, and APX against oxidative stress is well evident in many crop plants (Gill and Tuteja 2010). Ascorbate and glutathione were involved in scavenging H2O2 in combination with monodehydroascorbate reductase and glutathione reductase, which regenerate ascorbate. Furthermore, ascorbate displays multiple actions in plant growth including cell division, cell wall expansion and other developmental processes (Taïbi et al. 2016). Glutathione is non-enzymatic antioxidant and it is involved in various cellular processes under stress and it also acts as a substrate for glutathione S-transferase and glutathione peroxidase. Moreover, it can detoxify superoxide and hydroxyl radical and also function as non-enzymatic ROS scavenger (Foyer 2018). In this study, the UV-B priming induced the over synthesis of ascorbate and glutathione in rice seedlings. The enhanced accumulation of ascorbate and glutathione content aids in the detoxification of the ROS and thus plays a major role in effectively controlling lipid peroxidation and electrolyte leakage by retaining the membrane stability. The effective and efficient action of non-enzymatic antioxidants was observed in UV-B-primed rice seedlings exposed to NaCl stress than in the case of UV-B and PEG stresses. According to Hussain et al. (2016), various seed-priming treatments enhance the non-enzymatic antioxidants in rice seedlings.

In this study, seedling-priming treatments with low dose of UV-B trigger SOD, CAT, and APX activities as well as their mRNA level expression in rice seedlings under NaCl, PEG, and UV-B stresses. The enhanced antioxidant activity in UV-B-primed rice seedlings showed higher ROS scavenging ability and greater tolerance to these three stresses. However, less antioxidant activities in non-primed rice seedlings subjected to three stresses suggested the general incapability of these plants to tolerate stress-induced oxidative damage. The SOD plays an important role in catalyzing the dismutation of superoxide, while CAT and APX contribute to scavenging of H2O2 (Anjum et al. 2015). In stressed conditions, CAT and APX display a crucial role in preventing cell damage by regulating hydrogen peroxide in intracellular regions (Taïbi et al. 2016).Various other seed priming techniques were also found to induce enhanced SOD, CAT, and APX activities in rice seedlings (Hussain et al. 2016).

The mRNA-level expression of SOD, CAT, and APX was significantly augmented by the influence of seedling priming with UV-B. The isoforms of SOD, CAT, and APX such as Cu/Zn SOD, CatA, and APx1 got enhanced under the influence of oxidative, cold, and drought stresses to detoxify the ROS (Li et al. 2017; Rossatto et al. 2017). In this study mRNA expression levels of Cu/Zn SOD, CatA, and APx1 isoforms increased in rice by the effect of seedling priming with UV-B exposed to NaCl, UV-B, and PEG stresses.

Moreover, the results also revealed that the seedling priming with UV-B was more effective under NaCl stress than other stress treatments in rice. The greater antioxidative defense exhibited in this treatment was linked with the greater ROS scavenging mechanism, which reduced the lipid peroxidation and thus retained the membrane integrity in primed rice seedlings subjected to NaCl. The cross-tolerance exhibited in this case is one of the significant features of seedling priming with UV-B.

UV-B priming also significantly altered the mRNA level expression of stress-responsive proteins such as HSP and LEA in rice seedlings. HSPs act as molecular chaperones and have the capacity to act as a key factor in contributing towards cellular homeostasis under both normal and adverse growth conditions. The role of HSPs extends beyond their chaperone activity, they are involved in reducing the damage that results from ROS’ accumulation. The HSP gene was highly expressed in both primed and non-primed rice seedlings under UV-B stress than stressed conditions (NaCl and PEG). There are several reports of enhancement of HSP gene expression due to UV-B stress but none on UV priming. According to Al-Whaibi (2011), in plants under UV-B stress condition, the gene for HSPs was highly expressed in their aerial tissues (shoot). In rice plants, the HSP genes were over expressed in response to tolerance mechanisms against UV-B stress (Xu et al. 2011). In response to UV-B stress, genes of several HSPs were upregulated in grapevine (Pontin et al. 2010). These results can be correlated to the observation in this study, wherein gene expression level was higher in rice seedlings subjected to UV-B stress and still higher in these subjected to UV-B stress after UV-B priming. The enhanced HSP proteins largely contribute to the mechanisms of DNA repair as part of their molecular chaperone capabilities by interacting with DNA repair proteins. This could be one of the mechanisms of plant acclimation to UV-B stress radiation (Kravets et al. 2012).

Equally other abiotic stresses also have the potential to induce the expression of HSP genes as part of stress tolerance mechanisms. In rice, salinity (NaCl), desiccation (PEG), high pH and high temperature stresses induces the expression of Hsp90 gene (Al-Whaibi 2011). Liu et al. (2006) reported that expression of gene for Hsp90 was significantly increased in rice under salt stress. HSPs induced during priming in various plants have the potential to stabilize protein and membrane structures (Chen and Arora 2013). There are also some previous reports of priming (osmopriming) inducing activation of HSP gene. In tomato plants, the HSP gene activation was induced by osmopriming of seeds (Gupta et al. 2008). Although the above case was reported for seed priming, priming of seedlings also stimulated the expression of HSP gene in rice seedlings. The UV-B primed rice seedlings subjected to NaCl and PEG stress conditions also persuaded the mRNA-level expression of HSP gene.

LEA proteins have been implicated in various stress responses of plants. High-level accumulation of LEA proteins was reported in drought, osmotic, salt and cold stress (Lutts et al. 2016). In rice, group 3 LEA protein gene was over-expressed under drought, salt stress and abscisic acid treatment (Xiao et al. 2007). Various seed priming techniques were reported to induce the expression/accumulation of LEA transcript/protein, bringing about improved stress tolerance of seedlings emerging from primed seeds (Chen et al. 2012; Kubala et al. 2015). It was found that due to seed osmopriming in Spinacia oleracea (Chen et al. 2012) and Brassica napus (Kubala et al. 2015), the expression/accumulation of LEA transcript/protein was significantly altered under drought stress. Similarly, in our study, priming when carried out at seedling stage also influenced the gene expression level of LEA proteins. Both primed and non-primed PEG stress conditions of rice seedlings radically induced the expression level of LEA proteins. This observation can be justified because LEA proteins are well known to be involved in stress-tolerance process associated with drought/osmotic stress tolerance. Various reports have conclusively shown that drought stress significantly alters the expression/accumulation of LEA transcript/protein in different plants (Wojtyla et al. 2016).

Conclusion

In this study, the exposure of rice seedlings to NaCl, UV-B, and PEG stresses significantly hampered the growth performance. However, the rice seedling priming with UV-B effectively assuaged the damaging effects of these stress. The seedling priming treatment with UV-B ensured vigorous seedling growth in rice seedlings under three different stress conditions. The primed stressed seedlings reduce the negative effects of stress through the enhancement of antioxidative potential and gene expression of stress-responsive proteins, and thus rice seedlings attain the tolerance potential against these stresses. The UV-B-primed seedlings exposed to NaCl stress were found to be more effective among all other treatments in imparting stress tolerance. This indicates that, the seedling priming with UV-B imparts a cross-tolerance mechanism which has to be studied in detail.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors express sincere thanks to Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) (09/0493(0175)/2016 EMR _1), India for providing funding in the form of SRF fellowship. Also acknowledge RARS, Pattambi, for providing rice seeds.

Author contributions

DTTT was responsible for the design of experiments, data analysis, and drafting the manuscript. DC and JTP took care of the study conception and design, and edited the manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, Jos T. Puthur states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical statement

This material has not been published in whole or in part elsewhere. The manuscript is not currently being considered for publication in another journal. All authors have been personally and actively involved in substantive work leading to the manuscript, and will hold themselves jointly and individually responsible for its content.

References

- Abid M, Hakeem A, Shao Y, Liu Y, Zahoor R, Fan Y, Suyu J, Ata-Ul-Karim ST, Tian Z, Jiang D, Snider JL. Seed osmopriming invokes stress memory against post-germinative drought stress in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Environ Exp Bot. 2018;145:12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2017.10.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Whaibi MH. Plant heat-shock proteins: a mini review. J King Saud Univ Sci. 2011;23:139–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jksus.2010.06.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anjum SA, Tanveer M, Hussain S, Bao M, Wang L, Khan I, Ullah E, Tung SA, Samad RA, Shahzad B. Cadmium toxicity in maize (Zea mays L.): consequences on antioxidative systems, reactive oxygen species and cadmium accumulation. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2015;22:17022–17030. doi: 10.1007/s11356-015-4882-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates LS, Waldren RP, Teare ID. Rapid determination of free proline for water studies. Plant Soil. 1973;39:205–207. doi: 10.1007/BF00018060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia M, Covarrubias AA. Late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) proteins in legumes. Front Plant Sci. 2013;4:190. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman CJ. Rice end-use quality analysis. Rice. 2019;2019:273–337. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-811508-4.00009-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantification of microgram quantities of proteins utilizing the principle of protein dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell MM. Solar UV irradiation and the growth and development of higher plants. In: Giese AC, editor. Photophysiology current topics in photobiology and photochemistry. New York: Academic Press; 1971. pp. 131–177. [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Arora R. Priming memory invokes seed stress-tolerance. Environ Exp Bot. 2013;94:33–45. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2012.03.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JX, Wang XF. Guide to plant physiological experiments. Guangzhou: South China University of Technology Press; 2002. pp. 123–127. [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Fessehaie A, Arora R. Dehydrin metabolism is altered during seed osmopriming and subsequent germination under chilling and desiccation in Spinacia oleracea L. cv. Bloomsdale: possible role in stress tolerance. Plant Sci. 2012;183:27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury FK, Rivero RM, Blumwald E, Mittler R. Reactive oxygen species, abiotic stress and stress combination. Plant J. 2017;90:856–867. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chunthaburee S, Dongsansuk A, Sanitchon J, Pattanagul W, Theerakulpisut P. Physiological and biochemical parameters for evaluation and clustering of rice cultivars differing in salt tolerance at seedling stage. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2016;23:467–477. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2015.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czarnocka W, Karpiński S. Friend or foe? Reactive oxygen species production, scavenging and signaling in plant response to environmental stresses. Free Radical Bio Med. 2018;122:4–20. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon FM, Tejedor MD, Ilina N, Chludil HD, Mithöfer A, Pagano EA, Zavala JA. Solar UV-B radiation and ethylene play a key role in modulating effective defenses against Anticarsia gemmatalis larvae in field-grown soybean. Plant Cell Environ. 2018;41:383–394. doi: 10.1111/pce.13104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doke N. Involvement of superoxide anion generation in the hypersensitive response of potato tuber tissues to infection with an incompatible race of Phytophthora infestans and to the hyphal wall components. Physiol Plant Pathol. 1983;23:345–357. doi: 10.1016/0048-4059(83)90019-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Espanany A, Fallah S, Tadayyon A. Seed priming improves seed germination and reduces oxidative stress in black cumin (Nigella sativa) in presence of cadmium. Ind Crops Prod. 2016;79:195–204. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2015.11.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Folin O, Denis W. A calorimetric method for the determination of phenols (and phenol derivatives) in urine. J Biol Chem. 1915;22:305–308. [Google Scholar]

- Foyer CH. Reactive oxygen species, oxidative signaling and the regulation of photosynthesis. Environ Exp Bot. 2018;154:134–142. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2018.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannopolitis CN, Ries SK. Superoxide dismutase in higher plants. Plant Physiol. 1977;59:309–314. doi: 10.1104/pp.59.2.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill SS, Tuteja N. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant machinery in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2010;48:909–930. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A, Dadlani M, Arun Kumar MB, Roy M, Naseem M, Choudhary VK, Maiti RK. Seed priming: the aftermath. Int J Agric Environ Biotechnol. 2008;1:199–209. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain S, Khan F, Cao W, Wu L, Geng M. Physiological and biochemical mechanisms of seed priming-induced chilling tolerance in rice cultivars. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:116. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javadmanesh S, Rahmani F, Pourakbar L. UV-B radiation, soil salinity, drought stress and their concurrent effects on some physiological parameters in maize plant. Am Eurasian J Toxicol Sci. 2012;4:154–164. [Google Scholar]

- Junglee S, Urban L, Sallanon H, Lopez-Lauri F. Optimized assay for hydrogen peroxide determination in plant tissue using potassium iodide. Am J Analyt Chem. 2014;5:730. doi: 10.4236/ajac.2014.511081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kar M, Mishra D. Catalase, peroxidase, and polyphenoloxidase activities during rice leaf senescence. Plant Physiol. 1976;57:315–319. doi: 10.1104/pp.57.2.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kravets EA, Zelena LB, Zabara EP, Blume YB. Adaptation strategy of barley plants to UV-B radiation. Emir J Food Agr. 2012;24:632. doi: 10.9755/ejfa.v24i6.632645. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kubala S, Garnczarska M, Wojtyla L, Clippe A, Kosmala A, Zmienko A, Lutts S, Quinet M. Deciphering priming-induced improvement of rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) germination through an integrated transcriptomic and proteomic approach. Plant Sci. 2015;231:94–113. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2014.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Han X, Song X, Zhang Y, Jiang J, Han Q, Liu M, Qiao G, Zhuo R. Overexpressing the Sedum alfredii Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase increased resistance to oxidative stress in transgenic Arabidopsis. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:1010. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Zhang X, Cheng Y, Takano T, Liu S. rHsp90 gene expression in response to several environmental stresses in rice (Oryza sativa L.) Plant Physiol Biochem. 2006;44:380–386. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutts S, Kinet JM, Bouharmont J. NaCl-induced senescence in leaves of rice (Oryza sativa L.) cultivars differing in salinity resistance. Ann Bot. 1996;78:389–398. doi: 10.1006/anbo.1996.0134. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lutts S, Benincasa P, Wojtyla L, Kubala S, Pace R, Lechowska K, Quinet M, Garnczarska M. New challenges in seed biology-basic and translational research driving seed technology. London: Intech Open; 2016. Seed priming: new comprehensive approaches for an old empirical technique. [Google Scholar]

- Nakano Y, Asada K. Hydrogen peroxide is scavenged by ascorbate-specific peroxidase in spinach chloroplast. Plant Cell Physiol. 1981;22:867–880. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey V, Shukla A. Acclimation and tolerance strategies of rice under drought stress. Rice Sci. 2015;22:147–161. doi: 10.1016/j.rsci.2015.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pontin MA, Piccoli PN, Francisco R, Bottini R, Martinez-Zapater JM, Lijavetzky D. Transcriptome changes in grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) cv. Malbec leaves induced by ultraviolet-B radiation. BMC Plant Biol. 2010;10:224. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-10-224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossatto T, do Amaral MN, Benitez LC, Vighi IL, Braga EJB, de Magalhaes Júnior AM, Maia MAC, da Silva Pinto L. Gene expression and activity of antioxidant enzymes in rice plants, cv. BRS AG, under saline stress. Physiol Mol Biol Plants. 2017;23:865–875. doi: 10.1007/s12298-017-0467-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sairam RK, Deshmukh PS, Shukla DS. Tolerance of drought and temperature stress in relation to increased antioxidant enzyme activity in wheat. J Agron Crop Sci. 1997;178:171–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-037X.1997.tb00486.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taïbi K, Taïbi F, Abderrahim LA, Ennajah A, Belkhodja M, Mulet JM. Effect of salt stress on growth, chlorophyll content, lipid peroxidation and antioxidant defence systems in Phaseolus vulgaris L. S Afr J Bot. 2016;105:306–312. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2016.03.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas DTT, Puthur JT. UV radiation priming: a means of amplifying the inherent potential for abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Environ Exp Bot. 2017;138:57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2017.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas DT, Puthur JT. Amplification of abiotic stress tolerance potential in rice seedlings with a low dose of UV-B seed priming. Funct Plant Biol. 2019;46:455–466. doi: 10.1071/FP18258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela-Avendañ JP, Mota IAE, Uc GL, Perera RS, Valenzuela-Soto EM, Aguilar JJZ. Use of a simple method to isolate intact RNA from partially hydrated Selaginella lepidophylla plants. Plant Mol Biol Rep. 2005;23:199–200. doi: 10.1007/BF02772713. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wojtyla Ł, Lechowska K, Kubala S, Garnczarska M. Molecular processes induced in primed seeds-increasing the potential to stabilize crop yields under drought conditions. J Plant Physiol. 2016;203:116–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2016.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao B, Huang Y, Tang N, Xiong L. Over-expression of a LEA gene in rice improves drought resistance under the field conditions. Theor Appl Genet. 2007;115:35–46. doi: 10.1007/s00122-007-0538-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Zhan C, Huang B (2011) Heat shock proteins in association with heat tolerance in grasses. Int J Proteom 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Xu Y, Charles MT, Luo Z, Mimee B, Tong Z, Véronneau PY, Roussel D, Rolland D. UV-C priming of strawberry leaves against subsequent Mycosphaerella fragariae infection involves the action of ROS, plant hormones and terpenes. Plant Cell Environ. 2019;42:815–831. doi: 10.1111/pce.13491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin D, Chen S, Chen F, Guan Z, Fang W. Morphological and physiological responses of two Chrysanthemum cultivars differing in their tolerance to water logging. Environ Exp Bot. 2009;67:87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2009.06.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng X, Ling H, Yang J, Li Y, Guo S. LEA proteins from Gastrodia elata enhance tolerance to low temperature stress in Escherichia coli. Gene. 2018;646:136–142. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2018.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.