Abstract

目的

研究新型抗抑郁药沃替西汀对环磷酸腺苷/环磷酸腺苷反应元件结合蛋白/脑源性神经营养因子(cAMP/CREB/ BDNF)信号转导通路的影响。

方法

将昆明小鼠随机分为对照组和慢性不可预知性温和应激(CUMS)造模组进行造模,采用糖水偏爱试验考察模型是否成功建立。造模结束后将CUMS组小鼠随机分为模型组、氟西汀组和沃替西汀组。采用悬尾试验、强迫游泳试验和旷场试验,考察沃替西汀对抑郁小鼠的抗抑郁作用。采用ELISA试剂盒检测小鼠海马组织中cAMP的含量。采用蛋白免疫印迹法检测小鼠海马组织中磷酸化CREB(pCREB)和BDNF的蛋白表达。

结果

沃替西汀显著缩短小鼠在悬尾和强迫游泳试验中的不动时间(P < 0.01),而对其在旷场试验中的自主活动行为没有影响(P>0.05),表明沃替西汀可改善抑郁小鼠的抑郁样行为;ELISA结果显示沃替西汀能显著增加小鼠海马组织内cAMP的含量(P < 0.01);蛋白免疫印迹结果表明沃替西汀可以促进pCREB和BDNF的蛋白表达(P < 0.01)。

结论

沃替西汀产生抗抑郁作用机制可能与影响cAMP/CREB/BDNF信号转导通路有关。

Keywords: 沃替西汀, 环磷酸腺苷, 环磷酸腺苷反应元件结合蛋白, 脑源性神经营养因子, 抑郁症

Abstract

Objective

To investigate the effects of vortioxetine on cAMP/CREB/BDNF signal pathway.

Methods

Forty Kunming mice were randomized into control group and chronic unpredictable mild stress (CUMS) group. After establishment of depressive models verified by sucrose preference test, the mice in CUMS group were divided into model group, fluoxetine group and vortioxetine group. The antidepressive effect of vortioxetine was analyzed by tail suspension test, forced swim test and open field test. The levels of cAMP were detected using a commercial ELISA kit, and the expressions of pCREB and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) were evaluated with Western blotting.

Results

Vortioxetine significantly shortened the immobility time of the depressive mice in tail suspension test and forced swim test without affecting the locomotor activity of the mice in open fields, suggesting the antidepressive effect of against depression in mice. Vortioxetine significantly increased the levels of cAMP and promoted the expression of pCREB and BDNF in the hippocampus of the mice (P < 0.01).

Conclusion

Vortioxetine improves the behaviors of mice with depression possibly by affecting the cAMP/CREB/BDNF signal pathway.

Keywords: vortioxetine, cAMP, cyclic AMP response element-binding protein, brain-derived neurotrophic factor, depression

抑郁症是一种常见的慢性精神性疾病,以心境低落、快感缺失为主要临床特征[1]。目前临床上用于抑郁症的药物主要有选择性5-羟色胺重摄取抑制剂(SSRIs)、三环类抗抑郁药(TCA)等[2-3]。其中,SSRIs如氟西汀,通过增加脑内突触间隙的神经递质5-羟色胺(5-HT)含量改善抑郁症状。随着研究的不断深入,已有报道表明氟西汀的抗抑郁作用机制不仅仅能增加神经递质5-HT含量,还能通过激活环磷酸腺苷反应元件结合蛋白/脑源性神经营养因子(cAMP/CREB/BDNF)信号转导通路,升高CREB蛋白磷酸化水平、促进BDNF的表达[4-5],从分子生物学效应上逆转抑郁症引起的病理病变,起到抗抑郁的作用和保护神经细胞不受应激损伤的作用。

2013年9月,美国食品药品监督管理局(FDA)批准选择性5-羟色胺重摄取抑制剂沃替西汀上市,用于抑郁症的治疗[6]。沃替西汀是5-HT3和5-HT7受体拮抗剂[7],主要是通过抑制5-HT再摄取并增强5-HT的活性而起到抗抑郁作用[8-9]。沃替西汀可以增加5-HT与其受体的结合,然而,结合后的下游事件则还不清楚,通过哪条信号通路介导其抗抑郁作用也不知道。我们前期在皮质酮模拟的抑郁症体外细胞模型实验中发现PKA/ CREB/BDNF信号通路参与氟西汀的药效作用[10],但这一信号通路是否也参与沃替西汀的抗抑郁作用则还未见报道。本课题旨在以氟西汀为阳性对照药,初步在经典的抑郁症动物模型中探讨沃替西汀是否也能对cAMP/CREB/BDNF信号转导通路产生影响,从而发挥抗抑郁作用。这一研究将进一步阐述沃替西汀抗抑郁作用的下游机制,同时也将证实cAMP/CREB/BDNF信号通路在抑郁症发病机制中的作用。

1. 材料和方法

1.1. 主要试剂

氟西汀(美仑生物技术有限公司);沃替西汀(阿拉丁生化科技股份有限公司);RIPA裂解液(凯基生物技术股份有限公司);蛋白酶抑制剂、磷酸酶抑制剂(Sigma-Aldrich);BCA蛋白定量分析试剂盒(赛默飞世尔科技公司);Western blot试剂(碧云天生物技术);Rabbit anti-CREB(Cell Signaling Technology, CST);Rabbit anti-pCREB(Merck Millipore);Rabbit antiBDNF(Sigma-Aldrich);Rabbit anti-GAPDH(Abcam);PVDF膜(Merck Millipore);蛋白Maker(赛默飞世尔科技公司);羊抗兔二抗(弗德生物科技有限公司);cAMP试剂盒(R & D Systems)。

1.2. 实验动物

雄性昆明小鼠,体质量22~25 g,南方医科大学实验动物中心提供。实验动物合格证编号:SCXK(粤)2011-0015。试验前动物适应饲养环境1周,遵循昼夜节律,环境安静,室温25 ℃,动物自由饮食饮水。

1.3. 建立模型及动物分组

雄性昆明小鼠在适应环境后,随机分为对照组、CUMS组。采用慢性不可预知性温和应激对CUMS组进行造模,应激因子如:夹尾1 min、足底电击10 s、4 ℃冰水游泳5 min、昼夜颠倒、禁食24 h、禁水24 h、湿笼24 h、倾斜45°饲养24 h等。每日选取1~2种应激方式,避免重复,持续6周。造模结束时进行糖水偏爱试验判定造模是否成功。将造模成功的动物随机分为模型组、氟西汀给药组(10 mg/kg)、沃替西汀给药组(5 mg/kg)。按0.1 mL/10 g的剂量连续灌胃给药28 d。

1.4. 行为学方法

1.4.1. 糖水偏爱试验

糖水偏爱试验先训练小鼠48 h,使小鼠适应饮糖水。所有小鼠均分笼饲养,每笼放置2小瓶,一瓶装1%糖水溶液,另一瓶装纯水。每12 h换1次瓶子位置。训练完后,动物先禁水禁食12 h,再给予每笼小鼠事先称过重量的2瓶水:1%糖水溶液和纯水,自由饮水1 h。试验结束后称取饮水瓶的重量计算糖水消耗量、纯水消耗量,再按公式计算小鼠糖水的偏好百分比:动物对糖水的偏好百分比(%)=糖水消耗量(g)/总液体消耗量(糖水消耗量(g)+纯水消耗量(g)×100%。

1.4.2. 强迫游泳试验

强迫游泳试验采用Prosolt等[11]建立的方法加以改进:小鼠放入高30 cm,直径11 cm,水深15 cm的圆形透明塑料桶,水温25 ℃,其后肢无法接触塑料桶底部,需通过不断挣扎得以浮于水面。录像记录小鼠在水中游泳6 min的行为表现,以小鼠漂浮于水面、四肢停止挣扎为不动的判定标准,记录开始后4 min的不动时间。

1.4.3. 悬尾试验

悬尾试验采用Steru等[12]建立的方法加以改进:用医用胶布粘在小鼠尾端,用夹子夹住胶布,使小鼠呈倒悬状态,录像记录6 min内小鼠的行为表现,统计6 min的不动时间。以停止挣扎、身体呈垂直倒悬状态、静止不动为判定标准。

1.4.4. 旷场试验

旷场试验在长×宽×高为40 cm×40 cm× 15 cm的敞箱中进行,敞箱被均分为5 cm×5 cm等份,内壁涂成黑色[13]。实验时将小鼠放入正中央的格子内,录像记录5 min内小鼠的活动情况。统计小鼠的水平运动得分(穿越格子数)和垂直运动得分(直立次数)。每次测试结束后用酒精清洁盒子底面。

1.5. 海马cAMP含量测定

冰上迅速剥离海马组织,用PBS冲洗组织样品,并按w(g):v(mL)=1:5体系加入0.1 mmoL的HCL,超声粉碎,10 000×g离心15 min(4 ℃),弃沉淀,取上清,并加入定量的1 mmoL氢氧化钠调pH至7左右。按ELISA试剂盒说明书操作,通过酶标仪测定样品吸光度值,计算样品cAMP含量。

1.6. 蛋白免疫印迹

冰上迅速取小鼠海马组织,置于含蛋白酶抑制剂、磷酸酶抑制剂的RIPA裂解液中匀浆,16 000×g离心30 min,取上清。按照BCA蛋白分析方法测定样品蛋白含量。按V(蛋白样品溶液):V(5×SDS-PAGE Loading Buffer)=4:1加入5×SDS-PAGE上样缓冲液。煮沸变性10 min,保存备用。各组样品进行SDS聚丙烯酰胺凝胶电泳,再转移至PVDF膜上,经5%脱脂奶粉室温封闭2 h后加入一抗4 ℃孵育过夜。经TBST漂洗后加入二抗,室温孵育2 h。再经漂洗后滴加ECL发光液于暗室中曝光显影。操作方法参考文献[14]。

1.7. 统计学方法

所有实验数据均采用均数±标准误表示,采用SPSS13.0统计软件进行单因素方差分析进行统计。组间多个样本间的两两比较先经方差齐性检验,若方差齐则采用Tukey's post-hoc法,若不齐则采用Dunnett's T3法,P < 0.05为差异具有显著性。柱状图采用GraphPad Prism 5软件绘制。

2. 结果

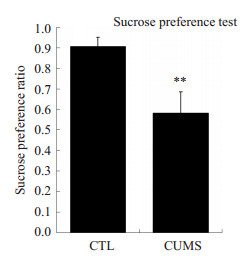

2.1. 慢性应激对小鼠糖水偏爱度的影响

快感缺失是抑郁症患者的典型症状,而抑郁小鼠的症状则表现为对糖水偏爱的显著下降。我们用糖水偏爱试验来考察抑郁小鼠对糖水偏爱程度的变化,从而判断小鼠是否出现抑郁症状。造模后,验证对照组(CTL)8只小鼠和CUMS组28只小鼠的糖水偏爱情况,结果如图 1所示,与对照组相比,模型组小鼠的糖水偏爱程度显著降低(P < 0.01),表明我们采用的慢性不可预知温和刺激抑郁模型(CUMS)成功建立。在此基础上,我们将28只CUMS组小鼠随机分为模型组(8只)、沃替西汀给药组(10只)和氟西汀给药组(10只),进行后续实验。

1.

慢性应激对小鼠糖水偏爱度的影响

Effect of CUMS on sucrose preference ratio of the mice in sucrose preference test. CTL group, n=8; CUMS group, n=28. **P < 0.01 vs CTL group.

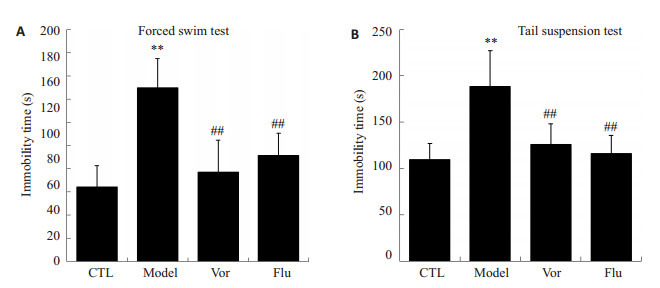

2.2. 沃替西汀对CUMS小鼠在强迫游泳试验和悬尾试验中不动时间的影响

强迫游泳试验和悬尾试验中的不动时间可反映试验动物的绝望状态和抑郁症状,其不动时间越长,表明其行为越绝望。图 2的结果显示与对照组相比,模型组小鼠在强迫游泳试验(图 2A)和悬尾实验(图 2B)中的不动时间显著延长,且具有统计学意义(P < 0.01)。而沃替西汀和阳性对照药氟西汀均能显著缩短小鼠在这两个试验中的不动时间(P < 0.01),表明沃替西汀具有抗抑郁的作用。

2.

沃替西汀对CUMS小鼠在强迫游泳和悬尾试验中不动时间的影响

Effect of vortioxetine on immobility time in forced swim test and tail suspension test of the mice with chronic unpredictable mild stress (CUMS) in CTL group (n=8), model group (n=8), Vor group (n=10) and Flu group (n=10). **P < 0.01 vs CTL group; ##P < 0.01 vs model group.

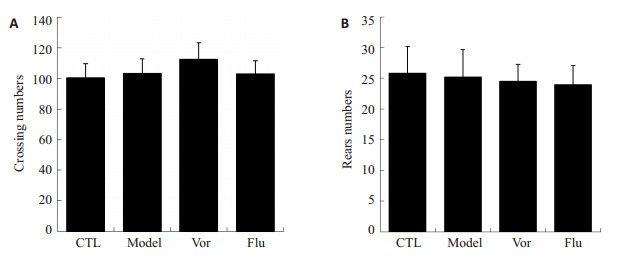

2.3. 沃替西汀对CUMS小鼠在旷场试验中自主活动的影响

旷场实验是评价动物自主行为、探索行为的行为学方法,通过其水平运动穿越格子的次数和垂直运动的站立次数,观察小鼠的自主行为和探索行为是否存在差异。结果如图 3显示,各组小鼠在5 min内,水平运动得分(图 3A)和垂直运动得分(图 3B)与对照组相比,均无显著性差异(P>0.05)。表明抑郁模型、氟西汀和沃替西汀给药均不会影响动物的自主运动活性和探索能力。

3.

沃替西汀对CUMS小鼠在旷场试验中自主活动的影响

Effects of vortioxetine on locomotor activity in open field test of CUMS mice in CTL group (n=8), model group (n=8), Vor group (n=10) and Flu group (n=10). A: Numbers of line crossing; B: Numbers of rearing.

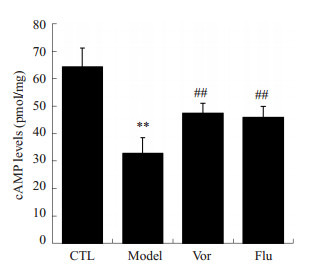

2.4. 沃替西汀对小鼠海马组织内cAMP含量的影响

行为学结束后,取小鼠海马组织检测cAMP含量。结果如图 4所示,模型组小鼠海马组织中cAMP含量明显低于对照组(P < 0.01)。而分别给予沃替西汀和氟西汀后,CUMS小鼠海马内cAMP的含量显著升高,且具有显著性差异(P < 0.01)。

4.

沃替西汀对CUMS小鼠海马组织内cAMP含量的影响

Effects of vortioxetine on the cAMP level in hippocampus of CUMS mice in CTL group (n=8), model group (n=8), Vor group (n=10) and Flu group (n=10). **P < 0.01 vs CTL group; ##P < 0.01 vs model group.

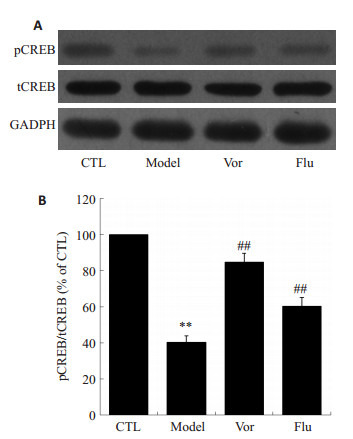

2.5. 沃替西汀对小鼠海马组织内pCREB蛋白表达的影响

取小鼠海马组织蛋白通过Western blot检测CREB蛋白的磷酸化水平。结果如图 5所示,模型组小鼠海马内pCREB蛋白水平明显低于对照组(P < 0.01)。而给予沃替西汀和氟西汀后,小鼠海马内pCREB蛋白表达显著上调(P < 0.01)。

5.

沃替西汀增加CUMS小鼠海马组织内pCREB的表达

Vortioxetine enhanced the expression of pCREB in CUMS mice. A: Expression of pCREB detected by Western blotting; B: Quantitative analysis of the results of Western blotting in CTL group (n=8), model group (n=8), Vor group (n=10) and Flu group (n=10). **P < 0.01 vs CTL group; ##P < 0.01 vs model group.

2.6. 沃替西汀对小鼠海马组织内BDNF蛋白表达的影响

取小鼠海马组织蛋白通过Western blot检测BDNF蛋白表达水平,结果如图 6所示,与对照组相比,模型组小鼠海马内BDNF蛋白表达显著降低(P < 0.01)。而给予沃替西汀和氟西汀后,小鼠海马内BDNF蛋白的表达明显上调(P < 0.01)。

6.

沃替西汀增加CUMS小鼠海马组织内BDNF的表达

Vortioxetine enhanced the expression of BDNF in CUMS mice. A: Expression of BDNF detected by Western blotting; B: Quantitative analysis of the results of Western blotting in CTL group (n=8), model group (n=8), Vor group (n=10) and Flu group (n=10). **P < 0.01 vs CTL group; ##P < 0.01 vs model group.

3. 讨论

SSRIs作为抑郁症治疗的一线药物,因疗效确切、服用方便、毒副作用小等优点,广泛用于临床。沃替西汀是一种新型SSRIs,由Lundbeck和Takeda制药公司联合研发,于2013年由FDA批准上市。对于沃替西汀的抗抑郁作用机制,目前公认的说法为抑制5-HT再摄取、增强5-HT活性[15]。然而药物对机体的作用往往涉及到多种作用机制,沃替西汀改善抑郁症的其它潜在机制值得进一步探究。本课题以经典SSRIs氟西汀为阳性对照药,初步探讨沃替西汀抗抑郁的其他作用机制,并首次发现沃替西汀的抗抑郁作用机制可能与影响cAMP/CREB/BDNF信号转导通路有关。

在本次研究中,我们采用经典的CUMS的方法,长期给予动物厌恶、不可逃避的应激刺激,诱导小鼠抑郁。这与人类抑郁症中慢性、低水平的应激源导致抑郁症的发生相接近,是目前应用最广泛的抑郁模型[16]。利用小鼠喜爱糖水的特性,采用糖水偏爱试验检测其是否出现快感缺失的抑郁症状[17]。强迫游泳和悬尾试验是用于评价动物抑郁样状态的经典方法,小鼠在试验中的不动时间越长,表明行为越绝望[11, 18]。为了排除药物因具有中枢兴奋作用而导致行为学试验的假阳性结果[19],我们通过旷场试验对动物的自主运动活性进行评价,以提高行为学试验结果的可信度。本次实验结果显示,在成功获得CUMS抑郁模型之后,给予沃替西汀能够显著缩短小鼠在强迫游泳和悬尾试验中的不动时间,而对小鼠在旷场试验中自主活动则无影响,表明沃替西汀的抗抑郁作用在抑郁小鼠上得到验证。此外,通过cAMP试剂盒及蛋白免疫印迹法检测cAMP及pCREB、BDNF含量,结果表明沃替西汀能够使抑郁小鼠海马内cAMP水平、pCREB及BDNF蛋白含量增加,这就表明沃替西汀可能是通过激活cAMP/CREB/BDNF信号转导通路来发挥抗抑郁作用。

大量的研究结果表明:抑郁症患者脑内海马组织pCREB和BDNF含量显著减少[20-21]。抗抑郁药激活细胞膜上的腺苷酸环化酶,AC催化ATP脱去一个焦磷酸而生产cAMP。cAMP作为第二信使在视觉和嗅觉、细胞生长分化和代谢、记忆和神经传递等生理过程中起重要的作用。它通过激活蛋白激酶A(PKA)进一步使其下游靶标CREB在133位的丝氨酸发生磷酸化[22-23]。CREB是核转录因子,被活化后通过结合核蛋白CRE调节下游靶基因的转录过程。BDNF是CREB的经典下游靶基因,其基因启动子区域含有CRE序列,CREB磷酸化从而促进了BDNF的表达[21, 24]。这与我们的研究结果沃替西汀增加cAMP含量、促进pCREB和BDNF表达相一致。BDNF对多种类型的神经元具有分化、增殖、营养以及成熟等作用,可影响神经元的可塑性及神经递质的合成,是抑郁症治疗中至关重要的神经营养因子[25-26]。

综上所述,沃替西汀可通过提高小鼠海马cAMP的含量、促进pCREB和BDNF的表达来改善小鼠的抑郁样症状,即沃替西汀的抗抑郁作用机制可能与激活cAMP/CREB/BDNF信号转导通路有关。

Biography

余汇,在读硕士研究生,E-mail: yuhuiguangzhou@163.com

Funding Statement

广东省科技计划项目(2012B061700110)

Contributor Information

余 汇 (Hui YU), Email: yuhuiguangzhou@163.com.

徐 江平 (Jiangping XU), Email: jpx@smu.edu.cn.

刘 永刚 (Yonggang LIU), Email: liuyg1999@163.com.

References

- 1.Mahar I, Bambico FR, Mechawar NA. Stress, serotonin, and hippocampal neurogenesis in relation to depression and antidepressant effects. http://d.scholar.cnki.net/detail/SJESTEMP_U/SJES14010600165763. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014;38(7):173–92. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.11.009. [Mahar I, Bambico FR, Mechawar NA. Stress, serotonin, and hippocampal neurogenesis in relation to depression and antidepressant effects[J]. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 2014, 38(7): 173-92.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lane RM. Antidepressant drug development: Focus on triple monoamine reuptake inhibition. J Psychopharmacol. 2015;29(5):526–44. doi: 10.1177/0269881114553252. [Lane RM. Antidepressant drug development: Focus on triple monoamine reuptake inhibition[J]. J Psychopharmacol, 2015, 29 (5): 526-44.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Purgato M, Gastaldon C, Papola D, et al. Drug dose as mediator of treatment effect in antidepressant drug trials: the case of fluoxetine. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2015;131(6):408–16. doi: 10.1111/acps.12381. [Purgato M, Gastaldon C, Papola D, et al. Drug dose as mediator of treatment effect in antidepressant drug trials: the case of fluoxetine [J]. Acta Psychiatr Scand, 2015, 131(6): 408-16.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qi XL, Lin WJ, Li JF, et al. Fluoxetine increases the activity of the ERK-CREB signal system and alleviates the depressive-like behavior in rats exposed to chronic forced swim stress. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;31(2):278–85. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.05.003. [Qi XL, Lin WJ, Li JF, et al. Fluoxetine increases the activity of the ERK-CREB signal system and alleviates the depressive-like behavior in rats exposed to chronic forced swim stress[J]. Neurobiol Dis, 2008, 31(2): 278-85.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tiraboschi E, Tardito D, Kasahara J, et al. Selective phosphorylation of nuclear CREB by fluoxetine is linked to activation of CaM kinase IV and MAP kinase cascades. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29(10):1831–40. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300488. [Tiraboschi E, Tardito D, Kasahara J, et al. Selective phosphorylation of nuclear CREB by fluoxetine is linked to activation of CaM kinase IV and MAP kinase cascades[J]. Neuropsychopharmacology, 2004, 29(10): 1831-40.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.张 建忠, 柯 樱, 沈 佳琳. 抗抑郁药的研发进展及市场情况. http://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-SYIY201421021.htm. 上海医药. 2014;(21):66–70. [张建忠, 柯樱, 沈佳琳.抗抑郁药的研发进展及市场情况[J].上海医药, 2014(21): 66-70.] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bang-Andersen B, Ruhland T, Jorgensen MA, et al. Discovery of 1-{[}2-(2, 4-Dimethylphenylsulfanyl) phenyl] piperazine (Lu AA21004): A novel multimodal compound for the treatment of major depressive disorder. J Med Chem. 2011;54(9):3206–21. doi: 10.1021/jm101459g. [Bang-Andersen B, Ruhland T, Jorgensen MA, et al. Discovery of 1-{[}2-(2, 4-Dimethylphenylsulfanyl) phenyl] piperazine (Lu AA21004): A novel multimodal compound for the treatment of major depressive disorder[J]. J Med Chem, 2011, 54(9): 3206-21.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.赵 桂平, 刘 文芳, 张 颖超, et al. 抗抑郁新药沃替西汀的药理与临床研究. http://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-GLYZ201502022.htm. 中国临床药理学杂志. 2015;(02):143–5. [赵桂平, 刘文芳, 张颖超, 等.抗抑郁新药沃替西汀的药理与临床研究[J].中国临床药理学杂志, 2015(02): 143-5.] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keks NA, Hope J, Culhane C. Vortioxetine: a multimodal antidepressant or another selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. Australas Psychiatry. 2015;23(3):210–3. doi: 10.1177/1039856215581297. [Keks NA, Hope J, Culhane C. Vortioxetine: a multimodal antidepressant or another selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor[J]. Australas Psychiatry, 2015, 23(3): 210-3.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zeng B, Li Y, Niu B, et al. Involvement of PI3K/Akt/FoxO3a and PKA/CREB signaling pathways in the protective effect of fluoxetine against Corticosterone-Induced cytotoxicity in PC12 cells. J Mol Neurosci. 2016;59(4):567–78. doi: 10.1007/s12031-016-0779-7. [Zeng B, Li Y, Niu B, et al. Involvement of PI3K/Akt/FoxO3a and PKA/CREB signaling pathways in the protective effect of fluoxetine against Corticosterone-Induced cytotoxicity in PC12 cells [J]. J Mol Neurosci, 2016, 59(4): 567-78.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Porsolt RD, Le Pichon M, Jalfre M. Depression: a new animal model sensitive to antidepressant treatments. Nature. 1977;266(564):730–2. doi: 10.1038/266730a0. [Porsolt RD, Le Pichon M, Jalfre M. Depression: a new animal model sensitive to antidepressant treatments[J]. Nature, 1977, 266 (564): 730-2.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steru L, Chermat R, Thierry B, et al. The tail suspension test: a new method for screening antidepressants in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1985;85(3):367–70. doi: 10.1007/BF00428203. [Steru L, Chermat R, Thierry B, et al. The tail suspension test: a new method for screening antidepressants in mice[J]. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 1985, 85(3): 367-70.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xiao L, O'callaghan JP, O'donnell JM. Effects of repeated treatment with phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors on cAMP signaling, hippocampal cell proliferation, and behavior in the Forced-Swim test. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;338(2):641–7. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.179358. [Xiao L. O'callaghan JP, O'donnell JM. Effects of repeated treatment with phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors on cAMP signaling, hippocampal cell proliferation, and behavior in the Forced-Swim test[J]. J Pharmacol Exp Ther, 2011, 338(2): 641-7.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang C, Cheng YF, Wang HT, et al. RNA Interference-Mediated knockdown of Long-Form phosphodiesterase-4D (PDE4D) enzyme reverses amyloid-beta (42)-Induced memory deficits in mice. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;38(2):269–80. doi: 10.3233/JAD-122236. [Zhang C, Cheng YF, Wang HT, et al. RNA Interference-Mediated knockdown of Long-Form phosphodiesterase-4D (PDE4D) enzyme reverses amyloid-beta (42)-Induced memory deficits in mice[J]. J Alzheimers Dis, 2014, 38(2): 269-80.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stahl SM. nodes explain the mechanism of action of vortioxetine. A multimodal agent (MMA): blocking 5HT3 receptors enhances release of serotonin, norepinephrine, and acetylcholine. CNS Spectr. 2015;20(05):455–9. doi: 10.1017/S1092852915000346. [Stahl SM, nodes explain the mechanism of action of vortioxetine. A multimodal agent (MMA): blocking 5HT3 receptors enhances release of serotonin, norepinephrine, and acetylcholine[J]. CNS Spectr, 2015, 20(05): 455-9.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Validity WP. Reliability and utility of the chronic mild stress model of depression: a 10-year review and evaluation. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1997;134(4):319–29. doi: 10.1007/s002130050456. [Validity WP. Reliability and utility of the chronic mild stress model of depression: a 10-year review and evaluation[J]. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 1997, 134(4): 319-29.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katz RJ, Roth KA, Carroll BJ. Acute and chronic stress effects on open field activity in the rat: implications for a model of depression. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1981;5(2):247–51. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(81)90005-1. [Katz RJ, Roth KA, Carroll BJ. Acute and chronic stress effects on open field activity in the rat: implications for a model of depression [J]. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 1981, 5(2): 247-51.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cryan JF, Valentino RJ, Lucki I. Assessing substrates underlying the behavioral effects of antidepressants using the modified rat forced swimming test. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/7847223_Assessing_substrates_underlying_the_behavioral_effects_of_antidepressants_using_the_modified_rat_forced_swimming_test. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2005;29(4/5, SI):547–69. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.03.008. [Cryan JF, Valentino RJ, Lucki I. Assessing substrates underlying the behavioral effects of antidepressants using the modified rat forced swimming test[J]. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 2005, 29(4/5, SI): 547-69.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mccarthy MM, Felzenberg E, Robbins A, et al. Infusions of diazepam and allopregnanolone into the midbrain central gray facilitate open-field behavior and sexual receptivity in female rats. Horm Behav. 1995;29(3):279–95. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1995.1020. [Mccarthy MM, Felzenberg E, Robbins A, et al. Infusions of diazepam and allopregnanolone into the midbrain central gray facilitate open-field behavior and sexual receptivity in female rats [J]. Horm Behav, 1995, 29(3): 279-95.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dowlatshahi D, Macqueen GM, Wang JF, et al. Increased temporal cortex CREB concentrations and antidepressant treatment in major depression. Lancet. 1998;352(9142):1754–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)79827-5. [Dowlatshahi D, Macqueen GM, Wang JF, et al. Increased temporal cortex CREB concentrations and antidepressant treatment in major depression[J]. Lancet, 1998, 352(9142): 1754-5.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mlyniec K, Budziszewska B, Holst BA, et al. GPR39(Zinc receptor) knockout mice exhibit Depression-Like behavior and CREB/BDNF Down-Regulation in the hippocampus. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/268387236_GPR39_(Zinc_Receptor)_Knockout_Mice_Exhibit_Depression-Like_Behavior_and_CREBBDNF_Down-Regulation_in_the_Hippocampus. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015;18(3):2. doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyu002. [Mlyniec K, Budziszewska B, Holst BA, et al. GPR39(Zinc receptor) knockout mice exhibit Depression-Like behavior and CREB/BDNF Down-Regulation in the hippocampus[J]. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol, 2015, 18(3): 2.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nibuya M, Nestler EJ, Duman RS. Chronic antidepressant administration increases the expression of cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) in rat hippocampus. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/14598369_Chronic_antidepressant_administration_increases_the_expression_of_cAMP_response_element_binding_protein_CREB_in_rat_hippocampus?_sg=7vsx4FgyvO4T_VstN6WCkDK2D-Lb4xRDMpHX7lF3QVbGso2Hlqo8bIwMr_h3n1ZNX4LAEqFvlLFLNk6mjGbqMQ. J Neuro. 1996;16(7):2365–72. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-07-02365.1996. [Nibuya M, Nestler EJ, Duman RS. Chronic antidepressant administration increases the expression of cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) in rat hippocampus[J]. J Neuro, 1996, 16 (7): 2365-72.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thome J, Sakai N, Shin K, et al. cAMP response element-mediated gene transcription is upregulated by chronic antidepressant treatment. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/12500112_cAMP_response_element-mediated_gene_transcription_is_upregulated_by_chronic_antidepressant_treatment. J Neurosci. 2000;20(11):4030–6. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-04030.2000. [Thome J, Sakai N, Shin K, et al. cAMP response element-mediated gene transcription is upregulated by chronic antidepressant treatment[J]. J Neurosci, 2000, 20(11): 4030-6.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ge L, Liu LW, Liu HS, et al. Resveratrol abrogates lipopolysaccharide-induced depressive-like behavior, neuroinflammatory response, and CREB/BDNF signaling in mice. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283048681_Resveratrol_abrogates_lipopolysaccharide-induced_depressive-like_behavior_neuroinflammatory_response_and_CREBBDNF_signaling_in_mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2015;768(4):49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.10.026. [Ge L, Liu LW, Liu HS, et al. Resveratrol abrogates lipopolysaccharide-induced depressive-like behavior, neuroinflammatory response, and CREB/BDNF signaling in mice[J]. Eur J Pharmacol, 2015, 768 (4): 49-57.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Angelucci F, Brene S, Mathe AA. BDNF in schizophrenia, depression and corresponding animal models. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10(4):345–52. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001637. [Angelucci F, Brene S, Mathe AA. BDNF in schizophrenia, depression and corresponding animal models[J]. Mol Psychiatry, 2005, 10(4): 345-52.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pittenger C, Duman RS. Stress, depression, and neuroplasticity: A convergence of mechanisms. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33(1):88–109. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301574. [Pittenger C, Duman RS. Stress, depression, and neuroplasticity: A convergence of mechanisms[J]. Neuropsychopharmacology, 2008, 33(1): 88-109.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]