Dear Editor,

Confident diagnosis of acute cutaneous graft-versus-host disease (aGVHD) is often challenging due to nonspecific clinical appearance and histopathology.1,2 Biopsies from different locations on the same patient frequently differ in grade, while normal-appearing skin may show aGVHD features.3 Serial biopsies of a single lesion are not possible. Lacking ability for informed site selection, timing, and serial noninvasive microscopic monitoring, some clinicians advocate empiric treatment in lieu of skin biopsies.4 In vivo reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM), of proven value in many skin diseases,5 might offer these missing insights and has been considered for aGVHD.6 A description of RCM features in patients is the next essential step towards evaluating possible clinical utility.

To create a consensus understanding and initial description of the features of aGVHD visible by RCM, we convened a panel of experts (SG, MA, MG, ET, CF), including an RCM-trained dermatopathologist (MG). We retrospectively reviewed all upper chest RCM cases from the Vanderbilt transplant program with clinical diagnosis of aGVHD rendered by a transplant physician. We included only patients whose biopsy, taken immediately from the RCM site, was consistent with aGVHD. Patients already treated for aGVHD were excluded. This yielded five patients (3 male, 2 female) age 54–70 years, 22–34 days after hematopoietic cell transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia (n=2) and myelodysplastic syndrome (n=3). Skin biopsies showed Lerner7 grade two (4/5 cases) or three (1/5). The panel had 20 videoconferences (seven with most experts present). Additionally, ET had five in-person data review meetings with one or more co-authors at the World Congress of Confocal Microscopy in Rome. Full datasets (histopathology, clinical history, images, and four to six 64 mm2 RCM blocks per case) were available to the panel and frequently consulted throughout this process. Through a modified Delphi method (without total anonymity), we resolved points of disagreement and agreed on a glossary of the essential features, as well as on specific verbiage describing them. ET and IS then jointly reconfirmed presence or absence of each feature in all five RCM datasets.

We assessed the following features based on the previously published RCM descriptions:8 (1) spongiosis (present in 4/5 of cases by RCM, 3/5 by histopathology); (2) exocytosis (5/5, 3/5); (3) dermal inflammation (5/5, 5/5); (4) vesicles (1/5, 2/5); (5) obscured DEJ (1/5 by RCM). By contrast, our consensus created or refined the following definitions: (6) irregular honeycomb: the epidermal honeycomb architecture is visible but irregular in terms of the size and/or shape of cells (5/5 by RCM); (7) disarranged epidermis: the epidermal architecture is so severely abnormal that it is difficult to see any honeycomb pattern (2/5 by RCM); (8) vacuolization: cell-sized dark holes in the epidermis and/or at the DEJ (5/5, 5/5); (9) necrotic keratinocytes: variably bright, homogenized usually round but may be bizarrely shaped structures that fit within the epidermal pattern but appear disconnected from the surrounding epithelium (5/5, 5/5); (10) satellite necrosis: necrotic keratinocytes that are physically touching one or more adjacent lymphocytes (5/5, 5/5); (11) periadnexal inflammation and necrosis: inflammatory cells (4/5, 4/5) or necrotic keratinocytes (4/5, 2/5) within 2–3 cells of adnexae; (12) colloid bodies: light grey, homogenous and uniform round aggregated structures (typically consisting of individual 15–25 µm elements) just beneath the epidermis (2/5, 2/5); (13) prominent vessels: vessels that appear more pronounced than in normal skin, either due to larger than usual dark lumina or increased density or movement of variably bright, variably sized bright structures (3/5, 2/5).

The most prominent RCM features of aGVHD (present in at least 4/5 cases) are spongiosis, irregular honeycomb, vacuolization, necrotic keratinocytes (including periadnexal and satellite necrosis), and epidermal, dermal and periadnexal inflammation. Several features such as irregular honeycomb pattern, epidermal disarrangement, and exocytosis (especially in effaced epidermis) are more readily visible in en face RCM views than on traditional vertical section histopathology. Because numerous adnexal structures are typically visible on the 8×8 mm2 horizontal sections, RCM enables a thorough examination of their involvement, which is a valuable, but non-specific histopathology finding. Although we observed the main aGVHD histopathology features by RCM, as in histopathology they may not be specific to aGVHD. Additionally, RCM cannot distinguish eosinophils from other granulocytes.

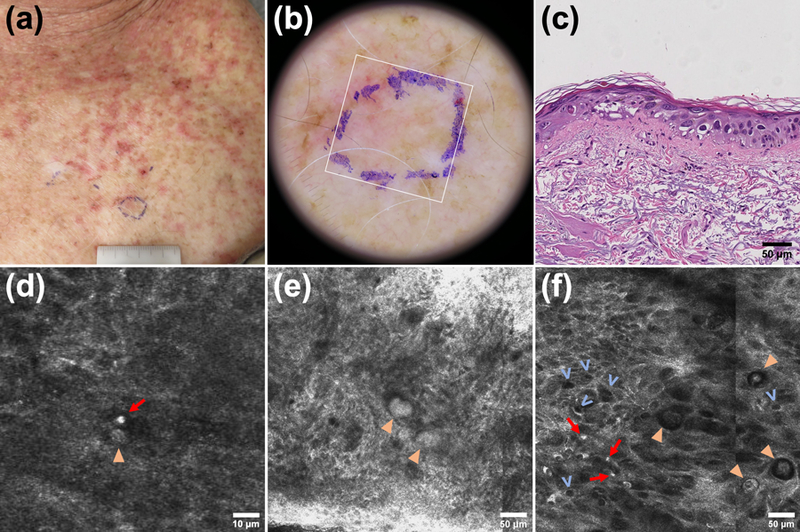

In summary, we have created and validated in five patients a glossary defining the RCM features of aGVHD (above in numbered list and Figure 1). The following RCM features were present in all cases: irregular honeycomb, vacuolization, necrotic keratinocytes, satellite necrosis, exocytosis, and dermal inflammation. This work will aid future studies aimed to improve patient care by monitoring aGVHD evolution and response to treatment over time.

Fig. 1.

RCM features of aGVHD in a 66 year-old male 28 days post-transplant for MDS from a match-related female donor. (a,b) Clinical and dermatoscopic photograph including the biopsy site (blue ink) and the RCM imaging site (white square). (c) Corresponding histopathology showing basilar and suprabasilar vacuolization (focally bordering on vesiculation), necrotic keratinocytes, keratinocytic nuclear pleomorphism (likely chemotherapy-induced), a sparse exocytosis, interface and dermal inflammation, and solar elastosis. (d) Satellite necrosis: a necrotic keratinocyte (arrowhead) adjacent to a lymphocyte (arrow). (e) Colloid bodies (arrowheads). (f) Irregular honeycomb (focally disarranged), lymphocytes (arrows) in the epidermis (exocytosis), and necrotic keratinocytes (arrowheads). Keratinocyte pleomorphism is also noted as in histopathology. Presence of vacuolization (v): cell-sized dark holes; note that these are sometimes referred to as “signet rings”. Obscured DEJ, periadnexal inflammation and necrosis, dermal inflammation, and prominent vessels in the dermis were also present; a more comprehensive figure with additional images can be offered on direct request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Funding statement: The work was supported by the Vanderbilt University Medical Center Department of Medicine, Career Development Award Number IK2 CX001785 from the United States Department of Veterans Affairs Clinical Sciences R&D (CSRD) Service, and the National Institutes of Health Grant K12 CA090625 to E.R.T.

Disclosures: Dr. Gill is a consulting investigator on an investigator-initiated study sponsored by DBV Technologies. Ms. Alessi-Fox is an employee and a shareholder of Caliber Imaging and Diagnostics Inc, the company that manufactures and sells the VivaScope confocal microscope. Dr. Gonzalez is a scientific Advisory Board member of Caliber ID. Other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. Dr. Tkaczyk has served as a paid scientific advisory board member for GVHD biomarker development to Incyte corporation.

References

- 1.Harris AC, Young R, Devine S, et al. International, multi-center standardization of acute graft-versus- host disease clinical data collection: a report from the MAGIC consortium. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2016; 22(1):4–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lehman JS, Gibson LE, El-Azhary RA, et al. Acute cutaneous graft-vs.-host disease compared to drug hypersensitivity reaction with vacuolar interface changes: A blinded study of microscopic and immunohistochemical features. J Cutan Pathol 2015; 42(1):39–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vassallo C, Brazzelli V, Alessandrino PE, et al. Normal-looking skin in oncohaematological patients after allogenic bone marrow transplantation is not normal. Br J Dermatol 2004; 151(3):579–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou Y, Barnett MJ, Rivers JK. Clinical significance of skin biopsies in the diagnosis and management of graft-vs-host disease in early postallogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Arch Dermatol 2000; 136(6):717–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grant-Kels JM, Pellacani G, Longo C. Reflectance confocal microscopy clinical applications: the skin from inside. Dermatol Clin 2016; 34:xii–xiv https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0733863516300833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huzaira M, Gonzalez S. Graft-versus-host disease, as seen by reflectance confocal microscopy and correlation with the corresponding histology. J Invest Dermatol 2003; 121(1):0374. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lerner KG, Kao GF, Storb R, Buckner CD, Clift RA, Thomas ED. Histopathology of graft vs. host reaction (GvHR) in human recipients of marrow from HLA matched sibling donors. Transplantation Proceedings 1974; 6:367–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ardigo M, Longo C, Gonzalez S, et al. Multicentre study on inflammatory skin diseases from The International Confocal Working Group: specific confocal microscopy features and an algorithmic method of diagnosis. Br J Dermatol 2016; 175(2):364–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]