Abstract

Phytoplasmas, a large group of plant-pathogenic, phloem-inhabiting bacteria were discovered by Japanese scientists in 1967. They are transmitted from plant to plant by phloem-feeding insect hosts and cause a variety of symptoms and considerable damage in more than 1,000 plant species. In the first quarter century following the discovery of phytoplasmas, their tiny cell size and the difficulty in culturing them hampered their biological classification and restricted research to ecological studies such as detection by electron microscopy and identification of insect vectors. In the 1990s, however, tremendous advances in molecular biology and related technologies encouraged investigation of phytoplasmas at the molecular level. In the last quarter century, molecular biology has revealed important properties of phytoplasmas. This review summarizes the history and current status of phytoplasma research, focusing on their discovery, molecular classification, diagnosis of phytoplasma diseases, reductive evolution of their genomes, characteristic features of their plasmids, molecular mechanisms of insect transmission, virulence factors, and chemotherapy.

Keywords: phytoplasma, genome, host specificity, mycoplasma-like organism, pathogenicity, plant pathology

1. History of mysterious plant diseases

The earliest record of phytoplasma diseases dates back about 1,000 years.1) Phytoplasma-infected tree peonies exhibiting floral virescence (green flowers) were prized in the imperial court of Song China, not as exemplars of plant disease but as the most precious and beautiful variety of the plant (Fig. 1). The earliest scientific record of a phytoplasma disease in Japan is of mulberry dwarf disease,2) which was first observed about 200 years ago.3) This disorder is highly destructive to the production of mulberry leaves (Fig. 2A), which are the sole food source of silkworms. Mulberry dwarf disease thus causes considerable damage to the silk manufacturing industry, which was a major export industry and important in the modernization of Japan. In 1897, the National Diet set up the first national research committee to determine the cause of the disease, but the committee failed after researching the problem for 7 years. Later, the discovery of its transmissibility by insects and by grafting led to the hypothesis that mulberry dwarf disease was caused by a virus, although the pathogen remained undiscovered.3) Many similar diseases caused by unknown insect-transmissible agents had also long been considered to be caused by undiscovered viruses (Fig. 2B). These so-called “yellows diseases” included rice yellow dwarf (Fig. 2C) and sweet potato witches’ broom, both of which caused serious damage to agricultural production in Japan, as well as aster yellows (Fig. 2D). These diseases still devastate many plant species worldwide. For example, in 2001, an outbreak of witches’ broom disease in apple trees caused losses of about €100 million in Italy and €25 million in Germany.4) Lethal yellowing has killed millions of coconut palm trees in the Caribbean over the past 40 years.5) Aster yellows disease is probably the best-known of these virus-like diseases, affecting more than 300 species in 38 families of plants; the disease is transmitted by leafhoppers.6)

Figure 1.

The earliest record of a phytoplasma disease is evident in peonies, attributed to Zhao Chang, a court painter of the Song Dynasty of China. The two flowers on the middle-right exhibit floral virescence symptoms. Printed with permission of the Museum of the Imperial Collections, Sannomaru-Shozokan.

Figure 2.

Various symptoms caused by yellows diseases. (A) Mulberry dwarf. (B) Paulownia witches’ broom. (C) Rice yellow dwarf. (D) Aster yellows. (E) Coconut lethal yellowing. (F) Poinsettia witches’ broom. (G) Hydrangea phyllody. (B, C, F, G) right side: infected plants; left side: healthy plants. The photographs were kindly provided by Drs. Akira Shirata (A), Norio Nishimura (B), and Akira Shinkai (C, D).

2. Discovery of mycoplasma-like organisms

In 1967, using electron microscopy, Doi et al. first described the consistent presence of small pleomorphic bodies (80–800 nm in diameter) resembling mycoplasmas (bacterial pathogens of humans and animals) in ultrathin sections of the phloem sieve elements of plants infected with mulberry dwarf, aster yellows, and other typical yellows diseases (Fig. 3A), but not in healthy plants.7) These microbes resembled mycoplasmas in their cell size, lack of a cell wall, and sensitivity to the antibiotic tetracycline (Fig. 3B),8) which inhibits protein synthesis by binding to the 30S ribosomal subunits of many prokaryotes. Given these similarities in morphological and biological properties, Doi et al. named them mycoplasma-like organisms (MLOs). The discovery of MLOs stimulated worldwide re-investigation of the etiology of numerous yellows diseases that had been assumed to be caused by viruses. Several hundred reports (initially employing electron microscopy) revealed the consistent presence of MLOs and their sensitivity to tetracycline, and confirmed the association between MLOs and yellows diseases.9–11)

Figure 3.

The discovery of mycoplasma-like organisms (MLOs). (A) MLO cells observed via electron microscopy in an ultrathin section of a plant phloem cell. (B) Tetracycline-mediated recovery of mulberry from dwarf symptoms. Symptomatic mulberries infected with mulberry dwarf MLO (left panel) were treated with tetracycline (100 ppm) via foliage spraying (20 mL/pot) and soil drenching (200 mL/pot) at intervals of 2 or 3 days (12 applications). One month later, the plants had recovered (right panels). The photographs in (B) were originally published in ref. 8.

3. Molecular detection and classification of MLOs

Although some researchers sought to differentiate yellows diseases based on symptomatology and host range,12,13) this was difficult because MLOs are associated with very similar symptoms in different plant species. Consequently, every time a new MLO disease was reported, the MLO was named using its original host plant name and symptom (e.g., mulberry dwarf, aster yellows). Eventually, more than 700 names were reported for MLO-associated diseases.14,15) Around 1990, advances in molecular biology enabled the direct detection of MLO DNA via DNA–DNA hybridization,16) polymerase chain reaction (PCR),17) and the cloning and sequencing of 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA).18) A universal PCR amplification method for MLO 16S rDNA was then developed19–21) and has become the gold standard for the detection of MLOs. These rDNA sequences revealed that MLOs form a monophyletic group that is evolutionarily distinct from mycoplasmas and can be phylogenetically classified via sequence comparisons.22–24) In 1993, the first MLO-specific universal PCR primer set exploiting conserved regions of mollicute 16S rDNA was developed, which selectively amplified 16S MLO rDNA from infected plants.19) Moreover, direct sequencing of PCR-amplified 16S rDNA fragments was pioneered, which made cloning unnecessary and enabled simple phylogenetic analyses.22) At about the same time, other MLO classification approaches [PCR amplification of 16S rDNA followed by analysis of restriction fragment length polymorphisms (RFLPs) revealed by restriction enzymes] were reported.20,25) Taken together, these studies contributed to the establishment of the taxonomy of MLOs by the International Organization for Mycoplasmology. MLOs were renamed phytoplasmas (phyto-: Greek for “plant”; plasma: Greek for “a thing that is molded”), and classified as a new genus ‘Candidatus (Ca.) Phytoplasma’ with rules based on the 16S rDNA sequences for the description of organisms as novel taxa.26–29) Following these rules, 44 ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma’ species have been reported to date (Fig. 4).30–38) Each phytoplasma was also found to have two rDNA operons.39) When closely related phytoplasmas within the same ‘Candidatus’ species are compared, housekeeping gene sequences are used in addition to those of 16S rDNA sequences for finer molecular characterization.40–42)

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic tree of life. MLOs are included in class Mollicutes (together with mycoplasmas), but they form a distinct group designated as the new genus ‘Ca. Phytoplasma’. More than 40 species have been described to date. This figure was reproduced with modifications based on the original literature.124)

These findings dramatically simplified the detection, diagnosis, and classification of MLOs, as well as encouraging phytoplasma research around the world.

4. Maintenance and mutation of phytoplasmas

Since the late nineteenth century, microbiology has relied on the ability to grow pure cultures of microorganisms on artificial media.43) Such culture enables the isolation, maintenance, propagation, and mutagenesis of microorganisms of interest, and plays central roles in many studies of microbial taxonomy and plant pathology. However, it is difficult to culture phytoplasmas, and maintenance requires periodic insect-vector-mediated transmission or grafting. The onion yellows phytoplasma (‘Ca. P. asteris’) OY-W (wild-type line) was selected for study because it has been stably maintained in a plant host [garland chrysanthemum (Glebionis coronaria)] using an insect vector (Macrosteles striifrons), and has been widely used as an experimental model in Japan. Garland chrysanthemum is a small long-lived plant that is suitable for propagation of both the phytoplasma and its insect vector. The isolation of phytoplasma mutant lines was attempted to identify the determinants of differences in their phenotypes. OY-M (mildly pathogenic line) was isolated from OY-W, which has been maintained with the aid of plant and insect hosts for 20 years (Fig. 5A); the mutant exhibits almost no plant pathogenicity.44,45) The genome size of OY-W is ca. 1 million base pairs (Mbp) but that of OY-M is ca. 0.86 Mbp. Furthermore, OY-NIM (non-insect-transmissible derivative of OY-M) was isolated after maintenance of OY-M in plants via periodic grafting onto healthy plants over 2 years (Fig. 5B).45) OY-NIM was not detected in the insect vector at any time after acquisition feeding on OY-NIM-infected plants, implying that the mutant cannot be acquired or multiply in the insect. The development of these first phytoplasma mutants (Fig. 5C) allowed us to take genetic approaches when exploring the pathogenicity and insect transmissibility of phytoplasmas.

Figure 5.

Establishment of the first phytoplasma mutant lines. (A) The mildly pathogenic mutant OY-M was isolated after 20 years of maintenance of the wild-type OY-W line in plant and insect hosts. (B) The non-insect-transmissible mutant line OY-NIM was isolated via 2-year grafting maintenance of OY-M (in the absence of the insect host). (C) Healthy plant and plants infected with OY-W and the mutant lines OY-M and OY-NIM. This figure was reproduced with modifications based on the original literature.124)

5. Phytoplasma genomics

Unlike common bacteria and many other organisms, including animals and plants, mycoplasmas use the UGA stop codon as a tryptophan-encoding codon.46) This unusual codon usage makes it difficult to study the functions of mycoplasma genes by expressing them in canonical hosts such as Escherichia coli and cultured eukaryotic cells; it is very burdensome to overcome this experimental barrier by replacing UGA with the general tryptophan codon UGG. However, when several phytoplasma operons were analyzed to determine the numbers of presumed tryptophan UGA codons, it was found that, unlike mycoplasmas, every UGA was a functional stop codon.47) Moreover, a gene encoding peptide chain release factor 2 that recognizes UGA as a termination codon is present in the phytoplasma genome.48) This, combined with several other genetic features shared between phytoplasmas and common bacteria such as E. coli,49,50) prompted us to commence advanced molecular and genetic analyses of phytoplasmas.

In 1994, phytoplasma whole-genome sequencing started in Japan. The onion yellows phytoplasma OY-W and mutant line OY-M were used, because these lines had been stably maintained in Japan, as described above, and because OY-M is a unique mutant lacking some determinants associated with pathogenicity. Finally, the draft genome of OY-W was reported in 200251) and the first complete genome sequence of 860,631 bp of the mutant OY-M was reported in 2004.52) The OY-M genome was circular with a G+C content of 28% and contained 754 open reading frames (ORFs) comprising 73% of the genome.

Gene annotation analysis revealed that although the genome encoded basic cellular functions including DNA replication, transcription, translation, and protein translocation, the genes required for amino acid and fatty acid biosynthesis, the tricarboxylic acid cycle, and electron transport/oxidative phosphorylation had been lost, as was also the case for Mycoplasma genitalium G-37 (580,070 bp), the smallest microbial genome known at that time (Fig. 6).53) The phytoplasma genome contained even fewer metabolic genes than the mycoplasma genome: the former genome lacked the phosphotransferase transport system, the pentose phosphate pathway, and (surprisingly) even adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthase, which had previously been regarded as essential for life. Rather, phytoplasma ATP synthesis may require the glycolytic54) and malate55) pathways. The genome was considered to reflect the reductive evolution often present in intracellular parasites and symbiotic bacteria.56–58) Such organisms frequently exhibit reduced genomes because they do not need many metabolic genes, given that they live in host-created nutrient-rich environments.

Figure 6.

Reductive evolution of phytoplasma metabolic pathways. This figure was reproduced with modifications based on the original literature.124)

Although metabolic genes were few in number, the OY-M genome contained many transporter genes absent from the mycoplasma genome. Phytoplasmas are obligate parasites of host cells, from which they obtain nutrients, instead of synthesizing essential substrates necessary for survival. The many transporters may play essential roles if an organism chooses “a little life without work” ([7] at https://www.newswise.com/articles/view/502315/). The phytoplasma genome is also rich in repeat regions with duplicated genes and transposon-like elements59) called potential mobile units;60) these feature similar genes organized in a conservative manner,59,61) and are thought to play roles in the regulation of gene expression62) and to serve as drivers of phytoplasma evolution in insect symbiosis and plant parasitism.54,63)

Phytoplasmas have also been discovered to possess plasmids.64–71) Of note, these plasmids were found to have chimeric replication proteins (Reps) with characteristics of both bacterial plasmid Reps and DNA viral Reps (Fig. 7). Additionally, the membrane protein-encoding gene (ORF3) of OY-M plasmids was lacking in plasmids of the insect-transmission-deficient mutant OY-NIM, implying that the gene may be involved in insect-mediated transmission, as described below.

Figure 7.

The chimeric “Rep” proteins of phytoplasma plasmids may be the missing link between bacterial plasmids and DNA viruses. This figure was reproduced with modifications based on the original literature.124)

6. Mechanisms to infect plants and insects

Phytoplasmas parasitize plants and insects (Fig. 8). They reside endocellularly within the plant phloem and are spread between plants by phloem-feeding insects such as leafhoppers, planthoppers, and psyllids. Due to their wide range of plant hosts, phytoplasmas are often detected in various crops and wild plants on which insect vectors have fed. When phytoplasma-infected insects feed on plants, phytoplasmas are initially injected into the phloem sieve tubes and then propagate within and spread from phloem tissues of the infected leaf to the main stem, root, and leaves via the bipolar movement of the phloem fluid at night and in the day.72)

Figure 8.

The life cycle of phytoplasmas; these are acquired by insects from plant phloem (via the stylets) and then enter the insect gut (acquisition feeding). Phytoplasmas must overcome three insect barriers to phytoplasma transmission (gut, hemocoel, and salivary gland barriers) if they are to be transmitted to plants. Phytoplasmas are transmitted from the insect to the phloem (of another plant) via inoculation feeding, and then multiply and establish a systemic infection, causing many unique symptoms. PP: phloem parenchymal cell, CC: companion cell, SE: sieve element. This figure was reproduced with modifications based on the original literature.124)

Because phytoplasmas have strict insect host ranges73–76) and are generally not transmitted transovarially (with a few exceptions),77) the presence or absence of insect hosts is a critical determinant of their survival in the natural environment. In insects, phytoplasmas establish systemic infection by spreading from the gut to hemocoel, then to the salivary gland, each of which presents a barrier to insect transmissibility (Fig. 8).45,78–80)

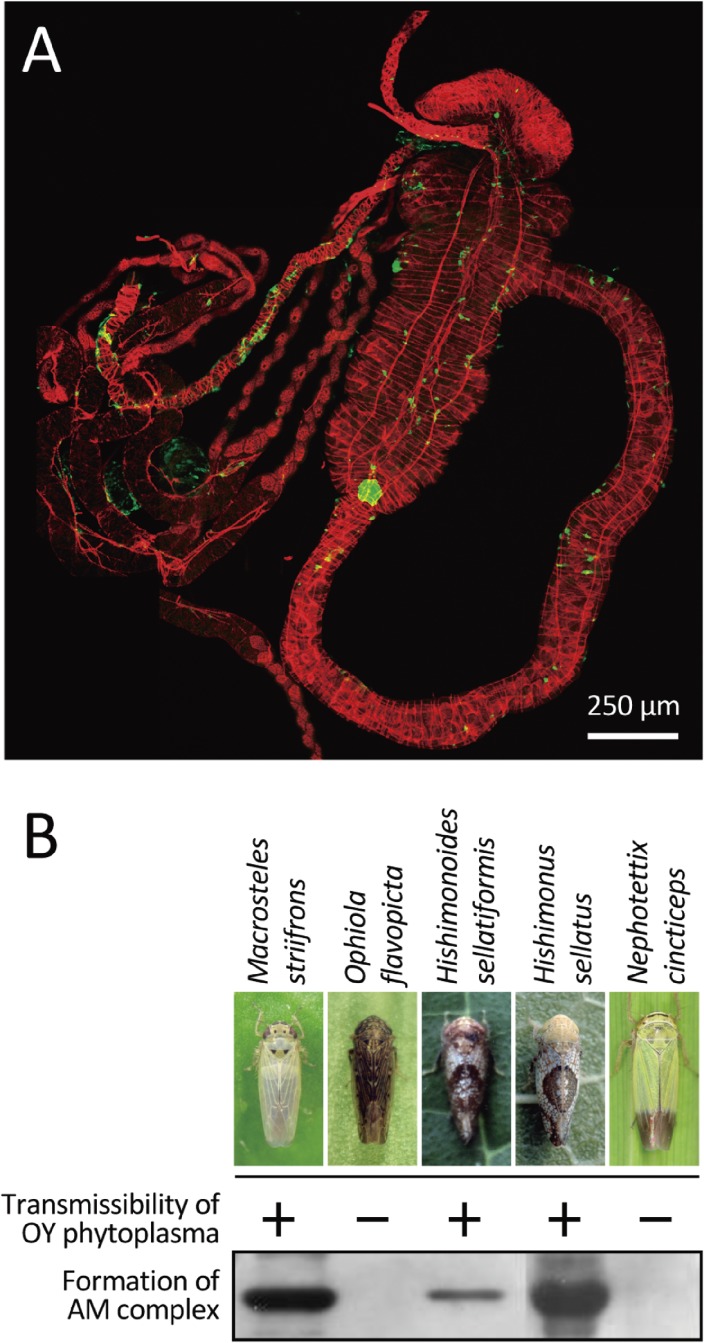

When invading insects, extracellular membrane proteins of phytoplasmas may play important roles in terms of phytoplasma-host interactions. The phytoplasma membrane proteins are delivered to the cell surface by the Sec protein-translocation system (Fig. 9).48,81–88) Notably, antigenic membrane protein (AMP) is a representative of phytoplasma membrane proteins that is predominantly detected on the phytoplasma cell surface.85) AMP was found to form a complex with host microfilaments (Fig. 10A) (Koinuma et al., unpublished data). The formation of such AMP-microfilament protein complexes determines whether an insect can transmit a phytoplasma (Fig. 10B).89,90) Additionally, the ATP synthase β-subunit of vector insects was found to be present in AMP-microfilament complexes.91) These reports contributed to elucidating the molecular mechanism by which pathogenic microorganisms of plants and animals are transmitted by specific insect vectors. Subsequently, immunodominant membrane protein (IMP), another phytoplasma membrane protein, was shown to bind to plant actin.92) Phytoplasmas lack movement genes, so this implies that actin-binding facilitates phytoplasma transport within sieve elements and through sieve plates, thus within the phloem, and ultimately ensures colonization of the plant host.92)

Figure 9.

The immunodominant membrane proteins of phytoplasmas and their localization. Most of the phytoplasma cell surface is covered with three membrane proteins termed immunodominant membrane proteins (IMP, AMP, and IDPA (immunodominant membrane protein A)), which are thought to be involved in interactions with both the insect and plant hosts. This figure was reproduced with modifications based on the original literature.124)

Figure 10.

The insect host ranges of OY phytoplasmas are determined by interactions between AMP and insect microfilaments. (A) Phytoplasma AMP co-localizes with microfilaments in the guts of insect vectors. Green: AMP detected with the aid of Alexa 488-conjugated IgG; Red: microfilaments stained with Alexa 546-coupled phalloidin. (B) Insect vector-specific formation of an AMP-microfilament complex. The photographs were kindly provided by Drs. Toshiki Shiomi (Ophiola flavopicta), Norio Nishimura (Hishimonoides sellatiformis), and Akira Shinkai (Hishimonus sellatus). This figure was reproduced with modifications based on the original literature.124)

Furthermore, a highly sensitive phytoplasma microarray, an in vitro transcription system, and an RNA sequencing method were developed to analyze gene expression patterns.93–95) These technical advances revealed that phytoplasmas dramatically alter the gene expression of approximately one-third of their genes using transcription factors to establish host switching between plants and insects.

7. Genetic factors determining symptom development

Phytoplasma-infected plants exhibit phloem necrosis and decline96) associated with a variety of unique morphological changes such as stunting, yellowing, witches’ broom (“tengu-su”, many tiny shoots with small leaves), phyllody (formation of leaf-like tissues instead of flowers), floral virescence; abnormal proliferation (growth of shoots from floral organs), and purple top (reddening of the upper leaves and apical parts).97) Some of these attributes have become successful gardening varieties worldwide. For example, all commercial poinsettias owe their economic value to their small bushy shape induced by grafting of a poinsettia branch-inducing strain of ‘Ca. P. pruni’ (Fig. 2F).87) Moreover, hydrangeas exhibiting floral virescence and phyllody were very valuable until the plants were shown to host phytoplasmas (Fig. 2G). However, the mechanisms by which phytoplasmas induce these various symptoms were unknown until recently.

Some of the molecular mechanisms by which phytoplasmas induce their typical symptoms have gradually been elucidated. Comparing the genome sequences of OY-W and OY-M revealed duplication of glycolytic gene clusters in the OY-W genome. It has been suggested that this difference is responsible for the high consumption of carbon sources, resulting in the high growth rates and severe symptoms, such as yellowing, dwarfism, and decline (Fig. 5C), associated with OY-W phytoplasma.54) Furthermore, the mechanisms of purple-top symptoms have been revealed. Phytoplasma infection activates the anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway. Increased accumulation of anthocyanin not only changes the color of leaves to purple but also acts as an antioxidant that protects plant cells from damage caused by reactive oxygen species, which results in leaf cell death.98)

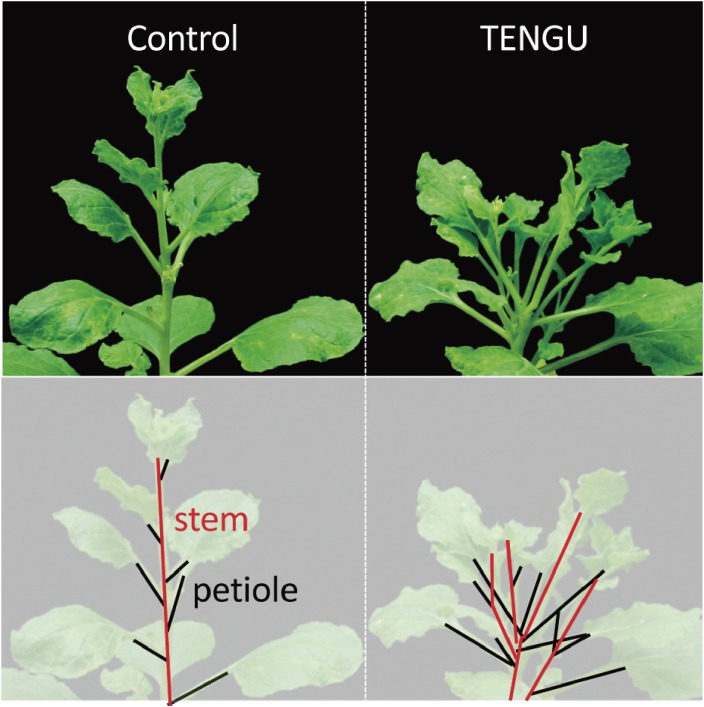

Many plant-pathogenic bacteria secrete proteins, termed effectors, into the cytoplasm of host cells for successful colonization. However, the phytoplasma genome does not contain any known effector-like genes.52) A comprehensive search was conducted for pathogenicity-related genes, in which phytoplasma genes encoding secreted proteins were introduced into host plants with the aid of a potato virus X-based gene expression vector. However, because gene mapping focused mostly on large proteins comprising 100 amino acids or more, it took some time to focus on small proteins or peptides comprising several tens of amino acids. In 2009, the first phytoplasma effector protein, TENGU, a secreted peptide of 38 amino acids, was identified as an inducer of witches’ broom (“tengu-su” symptoms; Fig. 11).99) TENGU is conserved among various phytoplasma strains. Following secretion from the phytoplasma cell, TENGU is cleaved in planta to a peptide of 12 amino acids, which is then transported to the shoot apical meristem, wherein it inhibits the signaling pathway of the plant hormone auxin and induces witches’ broom symptoms.99,100)

Figure 11.

Virus-vector-mediated expression of TENGU-peptide-induced “tengu-su” (witches’ broom) symptoms. Originally published in ref. 99.

These results elucidated the molecular mechanism of “tengu-su” symptoms, and were important findings in plant physiology. They also opened the way to a new breeding technology using TENGU peptide, instead of traditional plant production by inoculating phytoplasmas into commercial horticultural plants such as poinsettias, which may spread phytoplasmas.

TENGU also induces the sterility of male and female flowers by inhibiting the signaling pathway of another plant hormone, jasmonic acid (JA).101) The reduction in endogenous JA levels is thought to contribute to attracting insect vectors. Similarly, another secreted protein, SAP11, downregulates JA synthesis and increases the fecundity of insect vectors.102)

Floral organs are modified leaves,103) under the control of four combinations of floral homeotic proteins known as ABCE-class MADS-domain transcription factors (MTFs). In phytoplasma-infected plants, floral phyllody often affects sepals, but rarely stamens.104–106) Similarly, abnormal expression patterns of MTFs were found in all floral organs except stamens in phytoplasma-infected petunias.105) Recently, SAP54 and PHYL1 were found to be homologous proteins that induce phyllody in the floral organs of Arabidopsis thaliana.107,108) The proteins interact with and then degrade A- and E-class MTFs via the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway (Fig. 12),108–110) and are genetically and functionally conserved among phytoplasma strains and species.108,111,112) Therefore, these genetic homologs were placed in a phyllody-inducing gene/protein (phyllogen) family; the proteins induce floral phyllody and related floral malformations (virescence and proliferation).108,112) Phyllogens induce floral phyllody in various angiosperms (Fig. 13A), and MTF degradation in non-flowering plants (gymnosperms and a fern; Fig. 13B).112) These results indicated that phyllogen targets a conserved and functionally important region in MTFs.113,114)

Figure 12.

Phyllody symptom induction. A phyllogen protein expressed by phytoplasmas binds to and induces degradation of A- and E-class, MADS-domain-containing transcription factors (MTFs) via the 26S proteasome pathway, downregulating B-class MTF expression. Thus, phyllogens disturb the floral quartet model in an organ-specific manner. This figure was reproduced with modifications based on the original literature.124)

Figure 13.

Phyllogen converts the flowers of all plants to leaves. (A) Virus-vector-mediated expression of a phyllogen peptide induced phyllody symptoms in eudicot plants. (B) Phyllogen induced degradation of YFP-fused MTFs not only of eudicots but also of monocots, gymnosperms, and ferns. This figure was reproduced with modifications based on the original literature.124) The sunflower photographs were originally published in ref. 112.

Phyllogens induce virescence, phyllody, and proliferation symptoms, indicating that these floral symptoms are not independent symptoms induced by distinct effectors, but rather a series of gradually changing phenotypes that are all induced by a single effector, the phyllogen. In other words, floral virescence is a mild form of phyllody and loss of floral meristem determinacy is a severe form of phyllody.107–109,112) Thus, “phyllody” is a generic term that includes virescence, phyllody, and proliferation.

These findings elucidated the mechanisms of phyllody symptoms in plants at the molecular level, deepening the basic understanding of the mechanism of floral organogenesis and opening the way for new breeding technologies that use phyllogen to create high-value ornamental horticultural plants, such as hydrangeas with green flowers.

Why do phytoplasmas induce symptoms accompanied by unique morphological changes such as witches’ broom and phyllody? Both symptoms increase the prevalence of short branches and small young leaves,104) which are preferred by sap-feeding insects. Furthermore, the life of small young leaves and flowers with phyllody symptoms is prolonged. In particular, phyllody flowers remain green even when healthy flowers wither. These features are likely to enhance attraction of insect vectors and thus the spread of phytoplasmas. Such manipulations of the morphology of host plants appear to be a common strategy for the survival of phytoplasmas.

8. Detection and control of phytoplasmas

Because phytoplasmas are difficult to culture, electron microscopy observation using ultra-thin sections of sieve elements and plant recovery after tetracycline treatment were the only diagnostic methods available when phytoplasmas were discovered. Subsequently, several technologies to detect phytoplasmas have been developed, including autofluorescence when phloem-limited necrosis is present;115) fluorescent staining of phytoplasma DNA in phloem tissue;116) an antiserum-based method to detect the conserved membrane protein;82) and PCR to amplify conserved gene regions.19) However, these methods require expensive equipment or a complicated experimental technique, so diagnosing a phytoplasma disease is difficult in laboratories that lack modern facilities or with unstable infrastructure, such as unreliable power supply. Thus, easy, rapid, and sensitive diagnostic methods based on loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) were developed. The initial LAMP methods were species- or group-specific,117–120) but a universal LAMP kit for detecting all phytoplasma species in a single tube has recently been developed (Fig. 14A).41,42,121) Furthermore, to allow the kit to be carried, sent, or stored at room temperature, a method to dry the kit reagents was developed (Fig. 14B). Use of this dry kit is increasing in developing countries, where phytoplasma disease outbreaks are common (Fig. 14C).

Figure 14.

The universal LAMP kit for phytoplasma detection. (A) The LAMP kit is 1000-fold more sensitive than conventional PCR. (B) The reagents are dry; the kit can thus be transported and stored at room temperature. (C) Phytoplasmas detected in the field from sawdust of coconut trees within 1 h without the need for electrical equipment. This figure was reproduced with modifications based on the original literature.124) The photographs in (C) were kindly provided by Dr. Toshiro Shigaki.

In addition to the development of diagnostic methods, there has been an urgent requirement for agents/molecules to control phytoplasma diseases. To date, however, only tetracycline-class antibiotics have exhibited transient suppression of phytoplasma propagation and symptoms;8) no other chemical control agents are currently available. This is because screening is difficult given that phytoplasmas cannot easily be cultured in vitro. Although treatment using tetracycline-class antibiotics also suppresses phytoplasma propagation in infected plants cultured in vitro, high concentrations of antibiotics (>100 ppm) damage plant tissues.122,123) Therefore, a comprehensive screening system was developed that uses a plant-phytoplasma co-culture system to evaluate antibiotics, using lower concentrations of antibiotics (<100–20 ppm), to reduce damage to plant tissues and sustain the defense response of plant cells to phytoplasma (Fig. 15).121) Using this system, more than 40 antibiotics were tested, and several decreased OY-W phytoplasma concentrations. Moreover, phytoplasmas were completely eliminated from infected plants not only by application of tetracycline but also by application of rifampicin. Rifampicin was the first antibiotic found by this new method that specifically targets phytoplasmas, whereas tetracycline targets phytoplasmas and mycoplasmas. This co-culture system will contribute to the discovery of new anti-phytoplasma agents. Elimination of phytoplasma by in vitro culture using anti-phytoplasma agents will enable the production of phytoplasma-free nursery stocks, contributing to the preservation of mother trees and plants with cultural, biological, or religious significance; it will also support the international distribution of botanical resources.

Figure 15.

Identification of antimicrobials that control phytoplasma diseases. (A) The screening protocol. Phytoplasma-infected micropropagated shoots are cultured on Murashige and Skoog medium containing antimicrobials; anti-phytoplasma compounds are thus selected. (B) The targets of the antimicrobials. Phytoplasmas exhibit few such targets because they have lost most metabolic pathways, including those for cell wall biosynthesis, during reductive evolution. (C) Antimicrobials effective against phytoplasmas. The photographs were taken 4 weeks after beginning antimicrobial treatment. Phytoplasmas were not detected from host plants after tetracycline or rifampicin treatment for 4 months. This figure was reproduced with modifications based on the original literature.124)

Concluding remarks

Half a century ago, the discovery of phytoplasmas through Doi’s pioneering electron microscopy work led to a new research field on these novel pathogens, plant mycoplasmology, that was distinct from traditional virology and bacteriology.124) In the last quarter century, although there have been many barriers to the study of phytoplasmas, such as the difficulty of culturing and transforming them and the necessity of producing plant or insect hosts to maintain them, their molecular and biological properties have been elucidated. These advances have led to a new research field, phytoplasmology. Further developments, including functional definitions for all genes upon establishment of a transformation system, and the development of effective and eco-friendly agents to control phytoplasmas, will greatly contribute to both the understanding of phytoplasma biology and agricultural production over the next half-century.

Acknowledgments

The author sincerely thanks all of his colleagues and graduate students for their fruitful and long-term collaborations and valuable discussions. The work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) and the Program for Promotion of Basic Research Activities for Innovative Bioscience (PROBRAIN). The author appreciates the contributions of all the Japanese and foreign research collaborators.

Profile

Shigetou Namba was born in Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo in 1951, and later graduated and received his Ph.D. from The University of Tokyo. He was appointed as an Assistant Professor at The University of Tokyo in 1985. He subsequently spent a period as a visiting researcher at Cornell University (NY, U.S.A.). He was appointed as an Associate Professor (1992–1995), Professor (1995–2017), Project Professor (2006–), Professor Emeritus (2017–), a Special Advisor to the President (2009–) at the University of Tokyo, and a Fellow of the American Academy of Microbiology (2015–). He was President of the Phytopathological Society of Japan, and Vice Chairman of the Japanese Society of Mycoplasmology, a Managing Director of the International Organization of Mycoplasmology, a Councilor of the International Congress of Plant Pathology, a Team Leader of The International Research Program on Comparative Mycoplasmology and other academic societies. He was a Senior Editor of Molecular Plant Pathology (Wiley), and a member of the editorial boards of the Journal of General Plant Pathology (Springer) and other scientific journals. He received the Phytopathological Society Young Scientist Award in 1982, the Phytopathological Society Award in 2002, the Japanese Society of Mycoplasmology Kitamoto Award in 2004, the Emmy Klieneberger-Novel Award in Mycoplasmology in 2010, Medal with Purple Ribbon in 2013, the Japan Prize of the Agricultural Science in 2014, and the Japan Academy Prize in 2017.

References

- 1).Wang, M. and Maramorosch, K. (1988) Earliest historical record of a tree mycoplasma disease: Beneficial effect of mycoplasma-like organisms on peonies. In Mycoplasma Diseases of Crops: Basic and Applied Aspects (eds. Maramorosch, K. and Raychaudhuri, S.P.). Springer-Verlag, New York, pp. 349–356. [Google Scholar]

- 2).The Phytopathological Society of Japan (2018) Common Names of Plant Diseases in Japan (2018 edition). The Phytopathological Society of Japan, Tokyo (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 3).Ishiie T. (1965) Dwarf disease of mulberry tree. Ann. Phytopathol. Soc. Jpn. 31, 139–144 (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 4).Strauss E. (2009) Phytoplasma research begins to bloom. Science 325, 388–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5).Brown S.E., Been B.O., McLaughlin W.A. (2006) Detection and variability of the lethal yellowing group (16Sr IV) phytoplasmas in the Cedusa sp. (Hemiptera: Auchenorrhyncha: Derbidae) in Jamaica. Ann. Appl. Biol. 149, 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- 6).Davis, M.R. and Raid, R.N. (2002) Aster yellows and beet leafhopper-transmitted virescence agent yellows. In Compendium of Umbelliferous Crop Diseases. APS Press, St. Paul, pp. 58–59. [Google Scholar]

- 7).Doi Y., Teranaka M., Yora K., Asuyama H. (1967) Mycoplasma or PLT group-like microorganisms found in the phloem elements of plants infected with mulberry dwarf, potato witches’ broom, aster yellows, or Paulownia witches’ broom. Ann. Phytopathol. Soc. Jpn. 33, 259–266 (in Japanese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- 8).Ishiie T., Doi Y., Yora K., Asuyama H. (1967) Suppressive effects of antibiotics of tetracycline group on symptom development of mulberry dwarf disease. Ann. Phytopathol. Soc. Jpn. 33, 267–275 (in Japanese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- 9).Granados R.R., Maramorosch K., Shikata E. (1968) Mycoplasma: Suspected etiologic agent of corn stunt. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 60, 841–844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10).Hull R., Home R.W., Nayar R.M. (1969) Mycoplasma-like bodies associated with sandal spike disease. Nature 224, 1121–1122. [Google Scholar]

- 11).McCoy, R.E., Caudwell, A., Chang, C.J., Chen, T.A., Chiykowski, L.N., Cousin, M.T. et al. (1989) Plant diseases associated with mycoplasma-like organisms. In The Mycoplasmas, Vol. V (eds. Whitcomb, R.F. and Tully, J.G.). Academic Press, San Diego, pp. 545–640. [Google Scholar]

- 12).McCoy, R.E. (1979) Mycoplasmas and yellows diseases. In The Mycoplasmas, Vol. III (eds. Whitcomb, R.F. and Tully, J.G.). Academic Press, New York, pp. 229–264. [Google Scholar]

- 13).Shiomi T., Sugiura M. (1984) Difference among Macrosteles orientalis-transmitted MLO, potato purple-top wilt MLO in Japan and aster yellows MLO from USA. Ann. Phytopathol. Soc. Jpn. 50, 455–460 (in Japanese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- 14).Namba S. (2002) Molecular biological studies on phytoplasmas. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 68, 257–259. [Google Scholar]

- 15).Namba S. (2011) Phytoplasmas: A century of pioneering research. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 77, 345–349. [Google Scholar]

- 16).Kirkpatrick B.C., Stenger D.C., Morris T.J., Purcell A.H. (1987) Cloning and detection of DNA from a nonculturable plant pathogenic mycoplasma-like organism. Science 238, 197–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17).Deng S., Hiruki C. (1991) Amplification of 16S rRNA genes from culturable and nonculturable mollicutes. J. Microbiol. Methods 14, 53–61. [Google Scholar]

- 18).Lim P.O., Sears B.B. (1989) 16S rRNA sequence indicates that plant-pathogenic mycoplasmalike organisms are evolutionarily distinct from animal mycoplasmas. J. Bacteriol. 171, 5901–5906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19).Namba S., Kato S., Iwanami S., Oyaizu H., Shiozawa H., Tsuchizaki T. (1993) Detection and differentiation of plant-pathogenic mycoplasmalike organisms using polymerase chain reaction. Phytopathology 83, 786–791. [Google Scholar]

- 20).Lee I.-M., Hammond R.W., Davis R.E., Gundersen D.E. (1993) Universal amplification and analysis of pathogen 16S rDNA for classification and identification of mycoplasmalike organisms. Phytopathology 83, 834–842. [Google Scholar]

- 21).Schneider, B., Seemüller, E., Smart, C.D. and Kirkpatrick, B.C. (1995) Phylogenetic classification of plant pathogenic mycoplasma-like organisms or phytoplasmas. In Molecular and Diagnostic Procedures in Mycoplasmology (eds. Razin, S. and Tully, J.G.). Academic Press, San Diego, pp. 369–380. [Google Scholar]

- 22).Namba S., Oyaizu H., Kato S., Iwanami S., Tsuchizaki T. (1993) Phylogenetic diversity of phytopathogenic mycoplasmalike organisms. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 43, 461–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23).Namba S. (1993) Detection and differentiation of plant-pathogenic mycoplasma like organisms (MLO) using PCR amplification of 16S rRNA genes. Plant Protect. 47, 86–93 (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 24).Kuske C.R., Kirkpatrick B.C. (1992) Phylogenetic relationships between the western aster yellows mycoplasmalike organism and other prokaryotes established by 16S rRNA gene sequence. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 42, 226–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25).Schneider B., Ahrens U., Kirkpatrick B.C., Seemüller E. (1993) Classification of plant-pathogenic mycoplasma-like organisms using restriction-site analysis of PCR-amplified 16S rDNA. Microbiology 139, 519–527. [Google Scholar]

- 26).Namba S. (1995) New development in research of phytoplasmas. Plant Protect. 49, 11–14 (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 27).Namba S. (1996) Taxonomy of phytoplasmas. Plant Protect. 50, 152–156 (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 28).Namba S., Sawayanagi T., Lu X., Kagami T., Sun L. (1998) Phylogenetic classification of plant pathogenic mycoplasma. Jpn. J. Microbiol. 53, 443–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29).IRPCM (2004) ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma’, a taxon for the wall-less, non-helical prokaryotes that colonize plant phloem and insects. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 54, 1243–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30).Sawayanagi T., Horikoshi N., Kanehira T., Shinohara M., Bertaccini A., Cousin M.-T., et al. (1999) ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma japonicum’, a new phytoplasma taxon associated with Japanese Hydrangea phyllody. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 49, 1275–1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31).Jung H.-Y., Sawayanagi T., Kakizawa S., Nishigawa H., Miyata S., Oshima K., et al. (2002) ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma castaneae’, a novel phytoplasma taxon associated with chestnut witches’ broom disease. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 52, 1543–1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32).Jung H.-Y., Sawayanagi T., Kakizawa S., Nishigawa H., Wei W., Oshima K., et al. (2003) ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma ziziphi’, a novel phytoplasma taxon associated with jujube witches’-broom disease. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 53, 1037–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33).Jung H.-Y., Sawayanagi T., Wongkaew P., Kakizawa S., Nishigawa H., Wei W., et al. (2003) ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma oryzae’, a novel phytoplasma taxon associated with rice yellow dwarf disease. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 53, 1925–1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34).Jung H.-Y., Hahm Y.-I., Lee J.-T., Hibi T., Namba S. (2003) Characterization of phytoplasma associated with witches’ broom disease of potatoes in Korea. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 69, 87–89. [Google Scholar]

- 35).Jung H.-Y., Yae M.-C., Lee J.-T., Hibi T., Namba S. (2003) Aster yellows subgroup (Candidatus Phytoplasma sp. AY 16S-group, AY-sg) phytoplasma associated with porcelain vine showing witches’ broom symptoms in South Korea. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 69, 208–209. [Google Scholar]

- 36).Jung H.-Y., Woo T.-H., Hibi T., Namba S., Lee J.-T. (2003) Phylogenetic and taxonomic status of phytoplasma associated with water dropwort (Oenanthe javanica DC) diseases in Korea and Japan. Plant Pathol. J. 18, 109–114. [Google Scholar]

- 37).Jung H.-Y., Chang M.-U., Lee J.-T., Namba S. (2006) Detection of “Candidatus Phytoplasma asteris” associated with henon bamboo witches’ broom in Korea. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 72, 261–263. [Google Scholar]

- 38).Miyazaki A., Shigaki T., Koinuma H., Iwabuchi N., Rauka G.B., Kembu A., et al. (2018) ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma noviguineense’, a novel taxon associated with Bogia coconut syndrome and banana wilt disease on the island of New Guinea. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 68, 170–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39).Jung H.-Y., Miyata S., Oshima K., Kakizawa S., Nishigawa H., Wei W., et al. (2003) First complete nucleotide sequence and heterologous gene organization of the two rRNA operons in the phytoplasma genome. DNA Cell Biol. 22, 209–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40).Mitrović J., Kakizawa S., Duduk B., Oshima K., Namba S., Bertaccini A. (2011) The groEL gene as an additional marker for finer differentiation of ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma asteris’-related strains. Ann. Appl. Biol. 159, 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- 41).Iwabuchi N., Endo A., Kameyama N., Satoh M., Miyazaki A., Koinuma H., et al. (2018) First report of ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma malaysianum’ associated with Elaeocarpus yellows of Elaeocarpus zollingeri. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 84, 160–164. [Google Scholar]

- 42).Koinuma H., Miyazaki A., Wakaki R., Fujimoto Y., Iwabuchi N., Nijo T., et al. (2018) First report of ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma pruni’ infecting cassava in Japan. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 84, 300–304. [Google Scholar]

- 43).Austin B. (2017) The value of cultures to modern microbiology. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 110, 1247–1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44).Shiomi T., Tanaka M., Sawayanagi T., Yamamoto S., Tsuchizaki T., Namba S. (1998) A symptomatic mutant of onion yellows phytoplasma derived from a greenhouse-maintained isolate. Ann. Phytopathol. Soc. Jpn. 64, 501–505 (in Japanese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- 45).Oshima K., Shiomi T., Kuboyama T., Sawayanagi T., Nishigawa H., Kakizawa S., et al. (2001) Isolation and characterization of derivative lines of the onion yellows phytoplasma that do not cause stunting or phloem hyperplasia. Phytopathology 91, 1024–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46).Razin S., Yogev D., Naot Y. (1998) Molecular biology and pathogenicity of mycoplasmas. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62, 1094–1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47).Miyata S., Furuki K., Oshima K., Sawayanagi T., Nishigawa H., Kakizawa S., et al. (2002) Complete nucleotide sequence of the S10-spc operon of phytoplasma: Gene organization and genetic code resemble those of Bacillus subtilis. DNA Cell Biol. 21, 527–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48).Kakizawa S., Oshima K., Kuboyama T., Nishigawa H., Jung H.-Y., Sawayanagi T., et al. (2001) Cloning and expression analysis of Phytoplasma protein translocation genes. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 14, 1043–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49).Miyata S., Furuki K., Sawayanagi T., Oshima K., Kuboyama T., Tsuchizaki T., et al. (2002) Gene arrangement and sequence of str operon of phytoplasma resemble those of Bacillus more than those of Mycoplasma. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 68, 62–67. [Google Scholar]

- 50).Miura C., Sugawara K., Neriya Y., Minato N., Keima T., Himeno M., et al. (2012) Functional characterization and gene expression profiling of superoxide dismutase from plant pathogenic phytoplasma. Gene 510, 107–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51).Oshima K., Miyata S., Sawayanagi T., Kakizawa S., Nishigawa H., Jung H.-Y., et al. (2002) Minimal set of metabolic pathways suggested from the genome of onion yellows phytoplasma. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 68, 225–236. [Google Scholar]

- 52).Oshima K., Kakizawa S., Nishigawa H., Jung H.-Y., Wei W., Suzuki S., et al. (2004) Reductive evolution suggested from the complete genome sequence of a plant-pathogenic phytoplasma. Nat. Genet. 36, 27–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53).Fraser C.M., Gocayne J.D., White O., Adams M.D., Clayton R.A., Fleischmann R.D., et al. (1995) The minimal gene complement of Mycoplasma genitalium. Science 270, 397–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54).Oshima K., Kakizawa S., Arashida R., Ishii Y., Hoshi A., Hayashi Y., et al. (2007) Presence of two glycolytic gene clusters in a severe pathogenic line of Candidatus Phytoplasma asteris. Mol. Plant Pathol. 8, 481–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55).Saigo M., Golic A., Alvarez C.E., Andreo C.S., Hogenhout S.A., Mussi M.A., et al. (2014) Metabolic regulation of phytoplasma malic enzyme and phosphotransacetylase supports the use of malate as an energy source in these plant pathogens. Microbiology 160, 2794–2806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56).Oshima K., Namba S. (2005) Metabolic pathways encoded in the small genomes of bacterial parasites. Rec. Res. Develop. Bioenergetics 3, 45–61. [Google Scholar]

- 57).Oshima K., Maejima K., Namba S. (2013) Genomic and evolutionary aspects of phytoplasmas. Front. Microbiol. 4, 230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58).Namba, S., Oshima, K. and Gibb, K. (2005) Phytoplasma genomics. In Mycoplasmas: Pathogenesis, Molecular Biology, and Emerging Strategies for Control (eds. Blanchard, A. and Browning, G.). Horizon Bioscience, Norfolk, pp. 97–133. [Google Scholar]

- 59).Arashida R., Kakizawa S., Hoshi A., Ishii Y., Jung H.-Y., Kagiwada S., et al. (2008) Heterogeneic dynamics of the structures of multiple gene clusters in two pathogenetically different lines originating from the same phytoplasma. DNA Cell Biol. 27, 209–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60).Bai X., Zhang J., Ewing A., Miller S.A., Radek A., Schevchenko D.V., et al. (2006) Living with genome instability: The adaptation of phytoplasmas to diverse environments of their insect and plant hosts. J. Bacteriol. 188, 3682–3696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61).Jomantiene R., Davis R.E. (2006) Clusters of diverse genes existing as multiple, sequence-variable mosaics in a phytoplasma genome. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 255, 59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62).Toruño T.Y., Musić M.S., Simi S., Nicolaisen M., Hogenhout S.A. (2010) Phytoplasma PMU1 exists as linear chromosomal and circular extrachromosomal elements and has enhanced expression in insect vectors compared with plant hosts. Mol. Microbiol. 77, 1406–1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63).Miyata S., Oshima K., Kakizawa S., Nishigawa H., Jung H.-Y., Kuboyama T., et al. (2003) Two different thymidylate kinase gene homologues, including one that has catalytic activity, are encoded in the onion yellows phytoplasma genome. Microbiology 149, 2243–2250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64).Kuboyama T., Huang C.-C., Lu X., Sawayanagi T., Kanazawa T., Kagami T., et al. (1998) A plasmid isolated from phytopathogenic onion yellows phytoplasma and its heterogeneity in the pathogenic phytoplasma mutant. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 11, 1031–1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65).Oshima K., Kakizawa S., Nishigawa H., Kuboyama T., Miyata S., Ugaki M., et al. (2001) A plasmid of phytoplasma encodes a unique replication protein having both plasmid- and virus-like domains: Clue to viral ancestry or result of virus/plasmid recombination? Virology 285, 270–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66).Nishigawa H., Miyata S., Oshima K., Sawayanagi T., Komoto A., Kuboyama T., et al. (2001) In planta expression of a protein encoded by the extrachromosomal DNA of a phytoplasma and related to geminivirus replication proteins. Microbiology 147, 507–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67).Nishigawa H., Oshima K., Kakizawa S., Jung H.-Y., Kuboyama T., Miyata S., et al. (2002) Evidence of intermolecular recombination between extrachromosomal DNAs in phytoplasma: A trigger for the biological diversity of phytoplasma? Microbiology 148, 1389–1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68).Nishigawa H., Oshima K., Kakizawa S., Jung H.-Y., Kuboyama T., Miyata S., et al. (2002) A plasmid from a non-insect-transmissible line of a phytoplasma lacks two open reading frames that exist in the plasmid from the wild-type line. Gene 298, 195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69).Nishigawa H., Oshima K., Miyata S., Ugaki M., Namba S. (2003) Complete set of extrachromosomal DNAs from three pathogenic lines of onion yellows phytoplasma and use of PCR to differentiate each line. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 69, 194–198. [Google Scholar]

- 70).Ishii Y., Kakizawa S., Hoshi A., Maejima K., Kagiwada S., Yamaji Y., et al. (2009) In the non-insect-transmissible line of onion yellows phytoplasma (OY-NIM), the plasmid-encoded transmembrane protein ORF3 lacks the major promoter region. Microbiology 155, 2058–2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71).Ishii Y., Oshima K., Kakizawa S., Hoshi A., Maejima K., Kagiwada S., et al. (2009) Process of reductive evolution during 10 years in plasmids of a non-insect-transmissible phytoplasma. Gene 446, 51–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72).Wei W., Kakizawa S., Suzuki S., Jung H.-Y., Nishigawa H., Miyata S., et al. (2004) In planta dynamic analysis of onion yellows phytoplasma using localized inoculation by insect transmission. Phytopathology 94, 244–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73).Nishimura N., Nakajima S., Sawayanagi T., Namba S., Shiomi T., Matsuda I., et al. (1998) Transmission of Cryptotaenia japonica witches’ broom and onion yellows phytoplasmas by Hishimonus sellatus Uhler. Ann. Phytopathol. Soc. Jpn. 64, 474–477. [Google Scholar]

- 74).Nishimura N., Nakajima S., Kawakita H., Sato M., Namba S., Fujisawa I., et al. (2004) Transmission of Cryptotaenia japonica witches’ broom and onion yellows by Hishimonoides sellatiformis. Jpn. J. Phytopathol. 70, 22–25 (in Japanese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- 75).Nishimura N., Nakajima S., Fujisawa I., Tsuchizaki T., Jung H.-Y., Kakizawa S., et al. (2007) A survey studying insects as vectors for the paulownia witches’ broom phytoplasma. Ann. Rep. Kanto-Tosan Plant Protect. Soc. 54, 93–97 (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 76).Weintraub P.G., Beanland L. (2006) Insect vectors of phytoplasmas. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 51, 91–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77).Bertaccini, A., Oshima, K., Kakizawa, S., Duduk, B. and Namba, S. (2016) Dissecting the multifaceted mechanisms that drive leafhopper host–phytoplasma specificity. In Vector-Mediated Transmission of Plant Pathogens (ed. Brown, J.K.). APS Press, St. Paul, pp. 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- 78).Nakajima S., Nishimura N., Matsuda I., Shiomi T., Namba S., Tsuchizaki T. (2002) Detection of mulberry dwarf and onion yellows phytoplasmas by PCR from insect vectors and noninsect vectors. Jpn. J. Phytopathol. 68, 39–42 (in Japanese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- 79).Hogenhout S.A., Oshima K., Ammar E.-D., Kakizawa S., Kingdom H.N., Namba S. (2008) Phytoplasmas: Bacteria that manipulate plants and insects. Mol. Plant Pathol. 9, 403–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80).Nakajima S., Nishimura N., Jung H.-Y., Kakizawa S., Fujisawa I., Namba S., et al. (2009) Movement of onion yellows phytoplasma and Cryptotaenia japonica witches’ broom phytoplasma in the nonvector insect Nephotettix cincticeps. Jpn. J. Phtopathol. 75, 29–34 (in Japanese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- 81).Kakizawa S., Oshima K., Nighigawa H., Jung H.-Y., Wei W., Suzuki S., et al. (2004) Secretion of immunodominant membrane protein from onion yellows phytoplasma through the Sec protein-translocation system in Escherichia coli. Microbiology 150, 135–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82).Wei W., Kakizawa S., Jung H.-Y., Suzuki S., Tanaka M., Nishigawa H., et al. (2004) An antibody against the SecA membrane protein of one phytoplasma reacts with those of phylogenetically different phytoplasmas. Phytopathology 94, 683–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83).Kakizawa S., Oshima K., Jung H.-Y., Suzuki S., Nishigawa H., Arashida R., et al. (2006) Positive selection acting on a surface membrane protein of the plant-pathogenic phytoplasmas. J. Bacteriol. 188, 3424–3428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84).Kakizawa S., Oshima K., Namba S. (2006) Diversity and functional importance of phytoplasma membrane proteins. Trends Microbiol. 14, 254–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85).Kakizawa S., Oshima K., Ishii Y., Hoshi A., Maejima K., Jung H.-Y., et al. (2009) Cloning of immunodominant membrane protein genes of phytoplasmas and their in planta expression. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 293, 92–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86).Kakizawa, S., Oshima, K. and Namba, S. (2010) Functional genomics of phytoplasmas. In Phytoplasmas: Genomes, Plant Hosts and Vectors (eds. Weintraub, P.G. and Jones, P.). CABI, Oxfordshire, pp. 37–50. [Google Scholar]

- 87).Neriya Y., Sugawara K., Maejima K., Hashimoto M., Komatsu K., Minato N., et al. (2011) Cloning, expression analysis, and sequence diversity of genes encoding two different immunodominant membrane proteins in poinsettia branch-inducing phytoplasma (PoiBI). FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 324, 38–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88).Neriya Y., Maejima K., Nijo T., Tomomitsu T., Yusa A., Himeno M., et al. (2014) Onion yellows phytoplasma P38 protein plays a role in adhesion to the hosts. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 361, 115–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89).Suzuki S., Oshima K., Kakizawa S., Arashida R., Jung H.-Y., Yamaji Y., et al. (2006) Interaction between the membrane protein of a pathogen and insect microfilament complex determines insect-vector specificity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 4252–4257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90).Hoshi A., Ishii Y., Kakizawa S., Oshima K., Namba S. (2007) Host-parasite interaction of phytoplasmas from a molecular biological perspective. Bull. Insectology 60, 105–107. [Google Scholar]

- 91).Galetto L., Bosco D., Balestrini R., Genre A., Fletcher J., Marzach C. (2011) The major antigenic membrane protein of “Candidatus Phytoplasma asteris” selectively interacts with ATP synthase and actin of leafhopper vectors. PLoS One 6, e22571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92).Boonrod K., Munteanu B., Jarausch B., Jarausch W., Krczal G. (2012) An immunodominant membrane protein (Imp) of ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma mali’ binds to plant actin. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 25, 889–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93).Oshima K., Ishii Y., Kakizawa S., Sugawara K., Neriya Y., Himeno M., et al. (2011) Dramatic transcriptional changes in an intracellular parasite enable host switching between plant and insect. PLoS One 6, e23242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94).Miura C., Komatsu K., Maejima K., Nijo T., Kitazawa Y., Tomomitsu T., et al. (2015) Functional characterization of the principal sigma factor RpoD of phytoplasmas via an in vitro transcription assay. Sci. Rep. 5, 11893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95).Nijo T., Neriya Y., Koinuma H., Iwabuchi N., Kitazawa Y., Tanno K., et al. (2017) Genome-wide analysis of the transcription start sites and promoter motifs of phytoplasmas. DNA Cell Biol. 36, 1081–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96).Uehara T., Tanaka M., Shiomi T., Namba S., Tsuchizaki T., Matsuda I. (1999) Histopathological studies on two symptom types of phytoplasma associated with lettuce yellows. Ann. Phytopathol. Soc. Jpn. 65, 465–469. [Google Scholar]

- 97).Maejima K., Oshima K., Namba S. (2014) Exploring the phytoplasmas, plant pathogenic bacteria. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 80, 210–221. [Google Scholar]

- 98).Himeno M., Kitazawa Y., Yoshida T., Maejima K., Yamaji Y., Oshima K., et al. (2014) Purple top symptoms are associated with reduction of leaf cell death in phytoplasma-infected plants. Sci. Rep. 4, 4111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99).Hoshi A., Oshima K., Kakizawa S., Ishii Y., Ozeki J., Hashimoto M., et al. (2009) A unique virulence factor for proliferation and dwarfism in plants identified from a phytopathogenic bacterium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 6416–6421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100).Sugawara K., Honma Y., Komatsu K., Himeno M., Oshima K., Namba S. (2013) The alteration of plant morphology by small peptides released from the proteolytic processing of the bacterial peptide TENGU. Plant Physiol. 162, 2005–2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101).Minato N., Himeno M., Hoshi A., Maejima K., Komatsu K., Takebayashi Y., et al. (2014) The phytoplasmal virulence factor TENGU causes plant sterility by downregulating of the jasmonic acid and auxin pathways. Sci. Rep. 4, 7399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102).Sugio A., Kingdom H.N., MacLean A.M., Grieve V.M., Hogenhout S.A. (2011) Phytoplasma protein effector SAP11 enhances insect vector reproduction by manipulating plant development and defense hormone biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, E1254–E1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103).von Goethe, J.W. (1790) Versuch die Metamorphose der Pflanzen zu erklären. C.W. Ettinger, Gotha. [Google Scholar]

- 104).Arashida R., Kakizawa S., Ishii Y., Hoshi A., Jung H.-Y., Kagiwada S., et al. (2008) Cloning and characterization of the antigenic membrane protein (Amp) gene and in situ detection of Amp from malformed flowers infected with Japanese hydrangea phyllody phytoplasma. Phytopathology 98, 769–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105).Himeno M., Neriya Y., Minato N., Miura C., Sugawara K., Ishii Y., et al. (2011) Unique morphological changes in plant pathogenic phytoplasma-infected petunia flowers are related to transcriptional regulation of floral homeotic genes in an organ-specific manner. Plant J. 67, 971–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106).Takinami Y., Maejima K., Takahashi A., Keima T., Shiraishi T., Okano Y., et al. (2013) First report of ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma asteris’ infecting hydrangea showing phyllody in Japan. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 79, 209–213. [Google Scholar]

- 107).MacLean A.M., Sugio A., Makarova O.V., Findlay K.C., Grieve V.M., Toth R., et al. (2011) Phytoplasma effector SAP54 induces indeterminate leaf-like flower development in Arabidopsis plants. Plant Physiol. 157, 831–841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108).Maejima K., Iwai R., Himeno M., Komatsu K., Kitazawa Y., Fujita N., et al. (2014) Recognition of floral homeotic MADS-domain transcription factors by a phytoplasmal effector, phyllogen, induces phyllody. Plant J. 78, 541–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109).MacLean A.M., Orlovskis Z., Kowitwanich K., Zdziarska A.M., Angenent G.C., Immink R.G., et al. (2014) Phytoplasma effector SAP54 hijacks plant reproduction by degrading MADS-box proteins and promotes insect colonization in a RAD23-dependent manner. PLoS Biol. 12, e1001835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110).Maejima K., Kitazawa Y., Tomomitsu T., Yusa A., Neriya Y., Himeno M., et al. (2015) Degradation of class E MADS-domain transcription factors in Arabidopsis by a phytoplasmal effector, phyllogen. Plant Signal. Behav. 10, e1042635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111).Yang C.Y., Huang Y.H., Lin C.P., Lin Y.Y., Hsu H.C., Wang C.N., et al. (2015) MicroRNA396-targeted SHORT VEGETATIVE PHASE is required to repress flowering and is related to the development of abnormal flower symptoms by the phyllody symptoms1 effector. Plant Physiol. 168, 1702–1716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112).Kitazawa Y., Iwabuchi N., Himeno M., Sasano M., Koinuma H., Nijo T., et al. (2017) Phytoplasma-conserved phyllogen proteins induce phyllody across the Plantae by degrading floral MADS domain proteins. J. Exp. Bot. 68, 2799–2811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113).Puranik S., Acajjaoui S., Conn S., Costa L., Conn V., Vial A., et al. (2014) Structural basis for the oligomerization of the MADS domain transcription factor SEPALLATA3 in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 26, 3603–3615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114).Iwabuchi N., Maejima K., Kitazawa Y., Miyatake H., Nishikawa M., Tokuda R., et al. (2019) Crystal structure of phyllogen, a phyllody-inducing effector protein of phytoplasma. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 513, 952–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115).Namba S., Yamashita S., Doi Y., Yora K. (1981) Direct fluorescence detection method (DFD method) for diagnosing yellows-type virus diseases and mycoplasma diseases of plants. Ann. Phytopathol. Soc. Jpn. 47, 258–263 (in Japanese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- 116).Hiruki C., da Rocha A. (1986) Histochemical diagnosis of mycoplasma infections in Catharanthus roseus by means of a fluorescent DNA-binding agent, 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole-2HCl (DAPI). Can. J. Plant Pathol. 8, 185–188. [Google Scholar]

- 117).Tomlinson J.A., Boonham N., Dickinson M. (2010) Development and evaluation of a one-hour DNA extraction and loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay for rapid detection of phytoplasmas. Plant Pathol. 59, 465–471. [Google Scholar]

- 118).Bekele B., Hodgetts J., Tomlinson J., Boonham N., Nikolić P., Swarbrick P., et al. (2011) Use of a real-time LAMP isothermal assay for detecting 16SrII and XII phytoplasmas in fruit and weeds of the Ethiopian Rift Valley. Plant Pathol. 60, 345–355. [Google Scholar]

- 119).Obura E., Masiga D., Wachira F., Gurja B., Khan Z.R. (2011) Detection of phytoplasma by loop-mediated isothermal amplification of DNA (LAMP). J. Microbiol. Methods 84, 312–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120).Sugawara K., Himeno M., Keima T., Kitazawa Y., Maejima K., Oshima K., et al. (2012) Rapid and reliable detection of phytoplasma by loop-mediated isothermal amplification targeting a house-keeping gene. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 78, 389–397. [Google Scholar]

- 121).Tanno K., Maejima K., Miyazaki A., Koinuma H., Iwabuchi N., Kitazawa Y., et al. (2018) Comprehensive screening of antimicrobials to control phytoplasma diseases using an in vitro plant–phytoplasma co-culture system. Microbiology 164, 1048–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122).Davies D.L., Clark M.F. (1994) Maintenance of mycoplasma-like organisms occurring in Pyrus species by micropropagation and their elimination by tetracycline therapy. Plant Pathol. 43, 819–823. [Google Scholar]

- 123).Aldaghi M., Massart S., Druart P., Bertaccini A., Jijakli M.H., Lepoivre P. (2008) Preliminary evaluation of antimicrobial activity of some chemicals on in vitro apple shoots infected by ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma mali’. Commun. Agric. Appl. Biol. Sci. 73, 335–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124).Namba, S. (2017) Phytoplasmology. University of Tokyo Press, Tokyo (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]