Abstract

While the triple tracer isotope dilution method has enabled accurate estimation of carbohydrate turnover after a mixed meal, use of the simple carbohydrate glucose as the carbohydrate source limits its translational applicability to everyday meals that typically contain complex carbohydrates. Hence, utilizing the natural enrichment of [13C]polysaccharide in commercially available grains, we devised a novel tracer method to measure postprandial complex carbohydrate turnover and indices of insulin action and β-cell function and compared the parameters to those obtained after a simple carbohydrate containing mixed meal. We studied healthy volunteers after either rice (n = 8) or sorghum (n = 8) and glucose (n = 16) containing mixed meals and modified the triple tracer technique to calculate carbohydrate turnover. All meals were matched for calories and macronutrient composition. Rates of meal glucose appearance (2,658 ± 736 vs. 4,487 ± 909 μM·kg−1·2 h−1), endogenous glucose production (−835 ± 283 vs. −1,123 ± 323 μM·kg−1·2 h−1) and glucose disappearance (1,829 ± 807 vs. 3,606 ± 839 μM·kg−1·2 h−1) differed (P < 0.01) between complex and simple carbohydrate containing meals, respectively. Interestingly, there were significant increase in indices of insulin sensitivity (32.5 ± 3.5 vs. 25.6 ± 3.2 10−5 (dl·kg−1·min−2)/pM, P = 0.006) and β-cell responsivity (disposition index: 1,817 ± 234 vs. 1,236 ± 159 10−14 (dl·kg−1·min−2)/pM, P < 0.005) with complex than simple carbohydrate meals. We present a novel triple tracer approach to estimate postprandial turnover of complex carbohydrate containing mixed meals. We also report higher insulin sensitivity and β-cell responsivity with complex than with simple carbohydrates in mixed meals of identical calorie and macronutrient compositions in healthy adults.

Keywords: complex carbohydrates, endogenous glucose production, glucose metabolism

INTRODUCTION

Landmark randomized clinical trials have demonstrated proven benefit of reducing glycemic exposure for preventing microvascular complications in diabetes mellitus (19, 39, 40). It is also recognized that postprandial glucose concentrations contribute significantly to glycemic exposure (24). Postprandial glucose concentrations reflect a net balance between the amount of glucose entering (rate of appearance: Ra) and leaving (rate of disappearance: Rd) the circulation (6, 33). Ra in turn is largely dependent on the rate of appearance of meal carbohydrate (Rameal) and, to a lesser extent, on the rate of endogenous glucose production (EGP), while Rd reflects the rate of whole body glucose uptake. Following meal ingestion, blood glucose concentrations rise for as long as Ra exceeds Rd and start to fall when Rd exceeds Ra. It is possible to estimate postprandial carbohydrate turnover using the isotope dilution technique. Initial methods applied the dual glucose tracer technique where a glucose tracer was infused constantly intravenously to measure the rate of appearance of another glucose tracer mixed with the glucose contained in the mixed meal (17, 23). To improve the measurement precision by minimizing non-steady-state errors in calculation of postprandial glucose turnover, in addition to an intravenous infusion of glucose tracer to mimic EGP, a third glucose tracer was infused intravenously to mimic the anticipated pattern of the rate of appearance of meal glucose (7). This triple tracer approach is currently a significant advancement for estimation of postprandial glucose turnover in nondiabetic humans (7, 32, 37) and has been applied in both type 1 (22) and type 2 diabetes (6). However, the fundamental premise of this approach requires that the tracer and tracee possess the same biochemical backbone to ensure identical metabolic processing by the human body. This principle therefore dictates that because the carbohydrate tracers used thus far in dual and triple tracer studies are exogenously labeled glucose (i.e., monosaccharide or simple carbohydrate), the tracee necessarily also has to be glucose in all of these mixed meal studies. Therefore, the dual and triple tracer studies published thus far mandate that all meal carbohydrate be in the form of glucose, i.e., monosaccharide.

A limitation of these studies is that they do not reflect everyday meals where people consume polysaccharides (complex carbohydrates) as the primary source of carbohydrates. Therefore, although the published studies provide some insight into postprandial glucose turnover in humans, the real-world translational applicability is limited. To the best of our knowledge, there has been one such attempt where the tracee carbohydrate was pasta (polysaccharide) but the tracer was labeled glucose (monosaccharide) mixed with the pasta (15). In that study, each subject also underwent an intravenous isoglycemic clamp to reproduce the plasma insulin and glucose concentrations obtained during the meal study. Rates of EGP calculated during the isoglycemic clamp were subtracted from total glucose appearance estimated during the meal studies to derive a measure of Rameal after ingestion of complex carbohydrates contained within the low or high glycemic load meals. This complicated methodological approach, was necessary because while the tracee (food) was complex carbohydrates (pasta and pie) contained in the meals, the tracer was simple carbohydrate ([13C]glucose), hence subject to differential metabolic processing after ingestion. Hence, quite appropriately, the authors did not use the meal tracer to calculate Rameal in their study. However, the authors acknowledge that since the meal and the isoglycemic clamp studies were conducted on separate days, their interpretation was confounded by interday variability within subjects.

The purpose of this study was to develop a novel approach by utilizing the natural abundance of 13C-labeled polysaccharide, which occurs with carbon fixation during photosynthesis, from commercially available food products. Carbon fixation in plants occurs via the C3 (Calvin-Benson) (5) and the C4 (Hatch-Slack) pathways (35). C3 plants, comprising ~95% of all of Earth’s plant biomass, draws carbon dioxide (CO2) directly from the atmosphere. These plants have in their isotopic signature a greater degree of 13C depletion in their polysaccharide backbone than the C4 plants. In contrast, the C4 plants fix carbon from the CO2 dissolved as malate in the ground water. These pathways lead to different 13C levels, with the C4 plants having δ13C values between −8 and −20‰ (29) and C3 plants varying between −22 and −35‰ (25). We utilized these differences in natural abundance of 13C to develop this method for estimation of carbohydrate fluxes following consumption of commercial food products in nondiabetic humans and compared the estimated pattern of Rameal, EGP, and Rd with those obtained in isocaloric meals containing the same quantity of simple carbohydrates and similar macronutrient proportions and content. We also measured and compared insulin sensitivity, β-cell responsivity to glucose and disposition indices in both simple versus complex carbohydrate meals.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

All study procedures and protocol were approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board. After informed consent, history, and physical examination, blood was tested to ensure normal kidney and liver functions. All women of childbearing potential had negative urine pregnancy test before proceeding further. An oral glucose tolerance test was performed to ensure normal glucose tolerance. A dietary history was taken at the time of screening to ensure adherence to a weight maintaining diet. Malabsorption disorders (e.g., celiac sprue) were excluded based on clinical history. Body composition was measured using dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (33). All subjects meeting the enrollment criteria returned to the Mayo Clinic Clinical Research Trials Unit (CRTU) for the study visits within 4 wk of the screen visit (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics and meal content

| Variables | Rice | Sorghum |

|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 30.9 ± 7.0 | 34.8 ± 10.5 |

| Sex, M/F | 4/4 | 5/3 |

| Weight, kg | 74.6 ± 14.9 | 67.3 ± 11.7 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.9 ± 2.7 | 22.9 ± 2.1 |

| FFM, kg | 54.8 ± 14.2 | 51.3 ± 10.1 |

| FBG, mM | 5.1 ± 0.8 | 4.8 ± 0.5 |

| PPG2h, mM | 4.9 ± 0.4 | 5.1 ± 0.8 |

| HbA1C, % | 5.0 ± 0.3 | 5.1 ± 0.3 |

| HbA1C, mmol/mol | 31.4 ± 3.1 | 32.5 ± 3.3 |

| TSH, mIU/L | 2.3 ± 0.5 | 2.2 ± 0.9 |

| BUN, mg/dL | 13.6 ± 2.8 | 16.3 ± 2.9 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 0.9 ± 0.1 |

| Meal Composition (Complex Carbohydrate) | ||

| Energy content, kcal | 599.4 ± 0.4 | 600.0 ± 0 |

| Carbohydrate, g | 52.2 ± 0.4 | 52.1 ± 0 |

| Protein, g | 38.4 ± 2.3 | 35.6 ± 0 |

| Fat, g | 25.7 ± 0.7 | 25.4 ± 0 |

| Fiber, g | 2.3 ± 0 | 8.0 ± 0 |

| Meal Composition (Jello) | ||

| Energy content, kcal | 600.1 ± 0.3 | 600.2 ± 0.1 |

| Carbohydrate, g | 52.2 ± 0.2 | 52.3 ± 0.1 |

| Protein, g | 35.3 ± 0.5 | 35.2 ± 0.1 |

| Fat, g | 27.1 ± 0.4 | 27.1 ± 0.4 |

| Fiber, g | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 |

Values are means ± SD. BMI, body mass index; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; FBG, fasting blood glucose; FFM, fat free mass; PPG2h, postprandial glucose at 2 hours; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone.

Study Visits

Subjects were studied twice, once with a standard mixed meal (Jello-O) containing simple carbohydrates (SC), exogenously labeled with [1-13C]glucose (7) and once with mixed meal containing either sorghum or Madagascar pink rice as the carbohydrate component, i.e., complex carbohydrates (CC). These two grains were chosen because they showed an abundance of [13C]polysaccharide significantly different from the natural [13C]polysaccharide enrichment of the average mixed meal and was also differentially detectable by mass spectrometry (Table 2). In addition, in all studies, two tracers were infused intravenously: [6, 6-2H2]glucose was started 3 h before the meal and then adjusted in a manner that mimics the anticipated changes in EGP, while [6-3H]glucose was started with the first bite of the meal and then adjusted to mimic the anticipated pattern of the meal glucose rate of appearance (Rameal) in plasma.

Table 2.

13C signatures of selected food products

| Description | Delta 13C, ‰ | Differences Between Other Starches And Average American Products (Delta 13C), ‰ |

|---|---|---|

| Madagascar pink rice | −28.90 | −2.35 |

| Argentinian arborio rice | −28.00 | −1.45 |

| Italian risotto rice | −27.30 | −0.75 |

| America long grain rice | −27.20 | −0.65 |

| Thai jasmine rice | −27.00 | −0.45 |

| Indian basmati rice | −26.80 | −0.25 |

| Uncle Ben instant rice | −26.60 | −0.05 |

| Spanish Calasparra rice | −26.60 | −0.05 |

| Average American products | −26.55 | 0.00 |

| American all-purpose flour | −26.50 | 0.05 |

| Indian flour | −25.80 | 0.75 |

| Thai tapioca flour | −25.30 | 1.25 |

| Australian Weet-Bix | −25.00 | 1.55 |

| Sorghum flour | −11.6 | 14.95 |

Each study involved an overnight stay in the CRTU. Subjects reported to the CRTU at ~1600. A point of care urine pregnancy test was performed where appropriate to ensure that the test was negative before proceeding further. Subjects were provided a standard 10 kcal/kg meal (55% carbohydrate, 15% protein, and 30% fat) consumed between 1700 and 1730. No additional food was eaten until the next morning. In the evening, an intravenous cannula was inserted into a forearm vein for glucose tracer infusion during the study.

In the morning, an intravenous cannula was inserted in a retrograde fashion into a hand vein for periodic blood draws and placed in a heated (55°C) Plexiglas box to enable drawing of arterialized-venous blood for plasma glucose, glucose tracer, and hormone analyses (33). At ~0500, a primed-continuous infusion of [6, 6-2H2]glucose based on fat free mass (11.84 mg/kg prime; 0.1184 mg·kg−1·min−1 continuous; Mass-Trace, Woburn, MA) was started. At 0800 (time 0), the test mixed meal was provided and consumed within ~30 min. The test meal consisted of ~50 g of carbohydrate as either Jell-O, cooked Madagascar pink rice, or cooked sorghum pancake with appropriate proportions of fat and protein to total 600 calories. As previously described for all studies, an infusion of [6-3H]glucose was started with the first bite of the meal at time 0, the infusion rate varied to mimic the anticipated rate of appearance of the [1-13C]glucose or [13C]polysaccharide contained within the meal to minimize perturbations in the ratio of [6-3H]glucose to [13C]glucose (specific activity ratio). At time 0, the rate of infusion of [6,6-2H2]glucose was altered to approximate the anticipated pattern of fall in EGP to minimize perturbations in the ratio of [6,6-2H2] glucose to endogenous glucose (tracer-to-tracee ratio). We analyzed data from previous pilot experiments for both rice and sorghum meals to determine the optimum tracer infusion rates to minimize changes in tracer-tracee ratios and applied these infusion rates of both [6-3H]glucose and [6, 6-2H2]glucose throughout the study. Following the last blood draw, all tracer infusions were stopped, all cannulas were removed, and subjects were provided a standard lunch and dismissed.

Finally, each subject was studied on another occasion with rice or sorghum containing mixed meal to assess the effects, if any, of interday variability of carbohydrate absorption on postprandial carbohydrate turnover. The study visits were at least 1 wk but not more than 4 wk apart. All visits were completed within 12 wk of the screen visit.

Due to technical reasons, data from the second visit were incomplete in three subjects in each of the rice and sorghum group (loss of intravenous access). However, all complete data sets were used to perform the statistical analysis (see below).

Study Meals

Weighed meals were provided by the CRTU kitchen. The rice and sorghum were cooked in the kitchen and served along with appropriate proportions of fat and protein ensuring that the macronutrient composition did not vary between meals. This meal provided 600 calories to all subjects, which represents the caloric content of an average breakfast meal. Contrary to some of our prior mixed meal studies that contained 75 g of carbohydrates (as monosaccharide glucose), we chose ~50 g of carbohydrates for this study due to the bulkiness of the cooked rice or sorghum that could have made it uncomfortable for the subjects to consume a meal containing 75 g instead. However, the SC and CC meals were matched for both carbohydrate amount and other macronutrients (Table 1).

Analytical Techniques

Plasma glucose, insulin, glucagon, [1-13C]glucose, [6, 6-2H2]glucose enrichment, and [6-3H]glucose specific activity were measured as described (33). The molar ratios were calculated for [13C]glucose ([13C]glucose/[12C]glucose) and [6, 6-2H2]glucose ([6, 6-2H2]glucose/[12C]glucose), respectively, with mass spectroscopy. C-peptide assays were performed on the Cobas e411 (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN), a two-site immunometric (sandwich) assay using electrochemiluminescence detection. Insulin assays used a two-site immunoenzymatic assay performed on the DxI automated immunoassay system (Beckman Instruments, Chaska, MN). Glucagon was measured by a direct, double antibody radioimmunoassay (Linco Research, St. Charles, MO).

Sorghum and Rice Digestion

To estimate 13C enrichment of the polysaccharides contained in sorghum and Madagascar pink rice, samples of the two products were digested by total starch assay procedures (12, 27). In brief, a total starch kit based on the use of thermo-stable α-amylase and amyloglucosidase was applied (Megazyme International, Ireland) which hydrolyzed starch into soluble branched and unbranched maltodextrins. Thereafter, amyloglucosidase hydrolyzed maltodextrins to d-glucose. By the above procedures, total starch was completely digested into d-glucose. The assay is specific for α-glucans (including starch, glycogen, phytoglycogen, and nonresistant maltodextrins). Thereafter, [13C]glucose enrichment of the digested product was performed as described below.

Analysis of Complex Carbohydrate Plasma 13C Enrichment

[13C]glucose obtained after absorption of the complex carbohydrate meal was analyzed by gas chromatograph (GC)/combustion/isotope ratio (IR)/MS by preparing the acetyl methyl boronate derivative. Briefly, 50 μL plasma was taken and proteins precipitated with 500 μL ice-cold ethanol. After centrifugation, the supernatant was evaporated to dryness and 100 μL of freshly prepared methane boronic acid in pyridine was added (15mg/ml) and the sample heated at 95°C for 45 min. After cooling, 50 μL acetic anhydride was added and the mixture heated at 95°C for 1 h. The cooled solution was evaporated to dryness under N2 and the residue dissolved in 100 μL isooctane (containing 5% acetic anhydride). The acetyl methyl boronate derivative of glucose was analyzed using a Thermo DeltaV Advantage isotope ratio mass spectrometer using a Thermo Trace Ultra gas chromatograph with online oxidation furnace held at 1,030°C. Separation of components was performed using a 30 mm × 0.25 mm ID × 0.25 μm DB5-MS capillary column utilizing Helium as carrier gas at 1.5 ml/min. Temperature program was 80°C–280°C at 15°C/min, 280–300°C at 30°C/min with a 3-min hold at 300°C. Split/splitless injector temp was 250°C, with 1 μL sample being injected in the splitless mode. The enrichment of 13CO2 resulting from the combustion of the glucose derivative was expressed as delta per mille (δ‰) versus Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite (VPDB). The delta value was then converted to mole percent by assuming that all six carbon atoms were labeled with 13C. The mole percent excess (MPE) values of the samples were then calculated by subtracting the baseline sample value from the enriched time points. Also, a sample of the respective meal carbohydrate, sorghum or rice, was run under the same conditions and the MPE calculated against the patient baseline.

The natural 13C levels in the CO2 produced were then measured by monitoring the ratio of 13CO2/12CO2 using a Thermo Delta V mass spectrometer and compared with a calibration curve (4, 28). The amount of [13C]glucose in the sample was expressed as the percentage of 13C above or below the natural levels in plasma before the meal comparing to VPDB international standard (δ13C) (10, 28). Precision (standard deviation) of measurement of [13C]glucose at natural abundance prepared as its methyl boronate derivative and analyzed using a Thermo Delta V GC/Comb/IR/MS was found to be ± 0.2 δ‰. The raw δ value for the natural abundance samples was −28.9 δ‰ for Madagascar pink rice and −11.7 δ‰ for sorghum (Table 2). Isotope correction and calibration procedure for carbon and oxygen in CO2 followed standard procedures.

Quality Control

To ensure consistency of natural labeling of the rice/sorghum products, we ensured that 1) the same batch of both these food products were used for every study subject; 2) samples of each food product were tested for consistency of the natural enrichment of [13C]glucose to use as a quality control check for each run of the assays. The gas chromatograph (GC)-combustion-isotope ratio mass spectrometer technique was performed and results interpreted in accordance with Good Practice Guide for Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometry (10).

Calculations

Fluxes.

The measured [13C]glucose molar ratio (MR) in plasma, i.e., the ratio of [13C]glucose to [12C]glucose in plasma (MR13C) corrected for natural abundance of 13C to 12C in natural glucose (MR13C,nat), is defined in (7) as

| (1) |

where G13C is the [13C]glucose tracer concentration, Gnat is natural glucose concentration, and G2H is intravenously infused [6,6-2H2]glucose tracer concentration in plasma.

[13C]polysaccharide in the meal is assumed to entirely contribute to G13C, while Gnat and G2H are assumed to both contribute to [12C]glucose and to [13C]glucose with 1/(1+MR13C,nat) = 98.9% and MR13C,nat/(1+MR13C,nat) = 1.1% of their mass, respectively. Similarly, the above natural MR13C in the meal, i.e., the ratio of [13C]glucose to [12C]glucose in the meal (MR13C,meal) corrected for natural abundance is proportional to the ratio between the tracer and the tracee in the meal (ttrmeal) as

| (2) |

Equations 1 and 2 can be applied in case of a meal that is naturally enriched (sorghum meal) with [13C]glucose, while this is not applicable in case of meal relatively depleted of [13C]glucose (rice meal) requiring modifications to Eq. 1 as

| (3) |

Similarly, Eq. 2 is modified as

| (4) |

This is in line with the relative 13C depletion in C4 plants (e.g., rice), with respect to the natural abundance of 13C levels in the average American diet.

As described (7), the measured [6,6-2H2]glucose molar ratio in plasma (MR2H), i.e., the ratio of [6,6-2H2]glucose to [6,6-1H2]glucose in plasma, can be calculated as

| (5) |

where [6,6-2H2]glucose tracer consists primarily of [6,6-2H2]glucose (with purity2H equal to 94%), a minor amount of [6,6-2H1-1H1]glucose, and a negligible amount of [6,6-2H1]glucose, while the total plasma glucose concentration (G) is

| (6) |

Coupling Eqs. 5 and 6 with Eq. 1 or Eq. 3 in case of meal enriched (sorghum) or depleted (rice) of [13C]glucose, respectively, the calculation of G13C, G2H, and Gnat can be summarized as

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

where |MR13C − MR13C,nat| is the absolute value of above natural MR13C. Finally, the endogenously produced plasma glucose concentration (Gend) can be calculated by subtracting from Gnat the contribution of ingested natural glucose, which is proportional to G13C as measured by ttrmeal, and accounting for the meal enriched or depleted with [13C]glucose as

| (10) |

where |ttrmeal| is the absolute value of ttrmeal.

Postprandial glucose fluxes, i.e., the rate of appearance of ingested glucose (Rameal), rate of endogenous glucose production (EGP), and rate of glucose disposal (Rd), were calculated using both a single (1-CM) (36) and a two-compartment (2-CM) description of glucose kinetics (31) using the same formulas reported in (7, 32). For sake of brevity, here we present results of the 1-CM model only (the use of 2-CM did not alter the results or the interpretation).

In particular, as reported in (7, 32), according to the 1-CM one obtains

| (11) |

where inf is the tracer infusion rate, TTR the tracer-to-tracee or specific activity ratio in plasma, C is the tracee plasma concentration, p is the pool fraction (fixed to 0.65), and V is the total volume of distribution (fixed in all subjects to 200 mL/kg).

Rate of appearance of the ingested tracer in the meal (Ra13C) was calculated using Eq. 11 assuming [6-3H]glucose as tracer and [1-13C]glucose as tracee, hence TTR is [6-3H]glucose/[1-13C]glucose, leading to

| (12) |

where F3H and G3H are the rate of intravenous infusion and the plasma concentration of [6-3H]glucose tracer, respectively. Rameal was finally calculated as

| (13) |

EGP was calculated using Eq. 11 but assuming [6,6-2H2]glucose as tracer and Gend as tracee, hence TTR is [6,6-2H2]glucose/Gend, leading to

| (14) |

where F2H is the infusion rate of [6,6-2H2]glucose tracer. Finally, Rd was calculated as

| (15) |

Insulin Sensitivity, β-Cell Responsivity Indices and Disposition Indices.

The indices of β-cell responsivity to glucose were estimated from plasma glucose and C-peptide concentrations using the oral C-peptide minimal model (8, 11). The model assumes that insulin secretion is made up of three components. The basal component is constant and represents the hormone secretion in fasting condition when glucose is also at baseline and is proportional (through parameter Φb; 10−9 min−1) to basal glucose concentration. The dynamic component represents secretion of promptly releasable insulin and is proportional to the rate of increase of glucose concentration through a parameter (Φd; 10−9) that defines the dynamic responsivity index. The static component derives from provision of new insulin to the releasable pool and is characterized by a static index (Φs; 10−9 min−1) and by a delay time constant (T; min). Total β-cell responsivity (Φtot; 10−9 min−1) is calculated as a composite of Φd and Φs.

Insulin sensitivity (SI), which measures the overall effect of insulin to stimulate glucose disposal and suppress endogenous glucose production, was estimated from plasma glucose and insulin concentrations using the oral glucose minimal model (11, 13). The model assumes that insulin acts from a compartment remote from plasma and describe the meal rate of appearance with a piecewise linear function. Dynamic, static, and total disposition indices (DId, DIs, DItot), which measure the β-cell function for prevailing insulin sensitivity, were then calculated as the product of Φ and SI.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as means ± SD if not differently stated. This study was designed to allow for estimation of differences in carbohydrate turnover between simple and complex carbohydrates. Differences were assessed using paired two-way ANOVA accounting for missing values. A P value <0.05 is considered statistically significant. The factors used in the analysis were the type of carbohydrate (SC vs. CC) and the visit (visit 1 vs. visit 2 of complex carbohydrate meals). In all the comparisons, visit 1 did not differ from visit 2. Additionally, there were no differences in either glucose or hormonal excursions or in the patterns of carbohydrate turnover and indices of insulin secretion and action between the rice and sorghum meals. Therefore, we have opted to report pooled data for the comparison of SC versus CC meals.

RESULTS

Plasma Glucose, Insulin, Glucagon, and C-Peptide

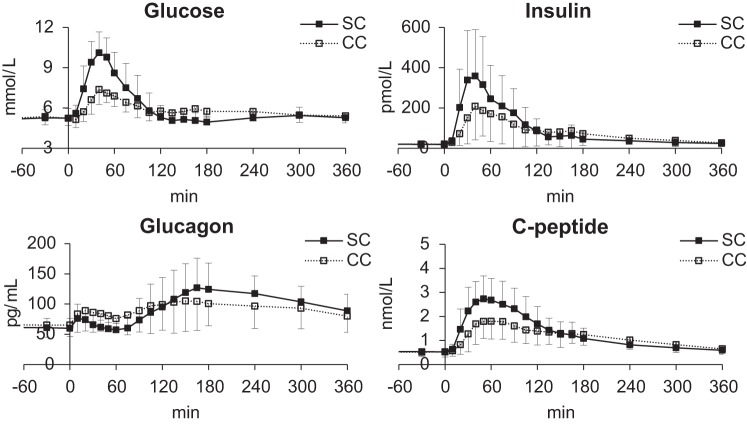

Basal plasma glucose concentrations were virtually identical during the SC and CC visits. However, the peak postprandial glucose concentrations were significantly lower with CC than SC while the time to peak did not differ between SC and CC. In addition, while the incremental (above-basal) area under the curve in the first 2 h after the meal (iAUC0–120) was significantly lower during CC versus SC meal, the incremental AUC during 6 h after the meal did not differ between the meals. Similarly, basal plasma insulin concentrations were similar during the SC and CC visit, while the postprandial insulin peak, the iAUC0–120, and iAUC0–360 were significantly lower with CC compared with SC. A similar pattern was observed with the pattern of C-peptide concentrations. In contrast, the integrated glucagon excursion for the first 2 h (P = 0.06) tended to be lower after SC than CC likely due to the enhanced insulin secretion with SC than CC during this period while the integrated glucagon excursion for the entire 6 h was lower (P < 0.02) with CC than SC (Fig. 1, Table 3). Additional comparisons of the parameters from 0 to 180 min are provided in Supplemental Table S1 (All Supplemental material is available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.8408975.v1).

Fig. 1.

Mean (±SD) plasma glucose (top left), insulin (top right), glucagon (bottom left), and C-peptide concentrations (bottom right) following mixed meal ingestion during simple carbohydrate (SC; ■) and complex carbohydrate (CC) meals (☐).

Table 3.

Glucose, glucagon, insulin, and C-peptide concentrations; RaMEAL, EGP, and Rd excursions during SC and CC containing meals

| SC | CC | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | |||

| Baseline, mmol/L | 5.2 ± 0.7 | 5.2 ± 0.5 | 0.72 |

| Peak, mmol/L | 10.6 ± 1.4 | 7.7 ± 1.0 | <0.0001 |

| Peak time, min | 44 ± 8 | 50 ± 16 | 0.13 |

| iAUC0–120, mmol·L−1·min−1 | 267 ± 122 | 121 ± 44 | 0.0001 |

| iAUC0–360, mmol·L−1·min−1 | 262 ± 202 | 217 ± 105 | 0.70 |

| Glucagon | |||

| Baseline, pg/mL | 59.8 ± 16.4 | 65.1 ± 19.1 | 0.18 |

| Peak, pg/mL | 139.9 ± 48.6 | 121.9 ± 46.3 | 0.07 |

| Peak time, min | 191 ± 48 | 155 ± 100 | 0.26 |

| iAUC0–120, pg·mL−1·min−1 | 1,225 ± 1,707 | 2,453 ± 2,194 | 0.06 |

| iAUC0–360, pg·mL−1·min−1 | 13,471 ± 6,078 | 9,819 ± 7,784 | 0.018 |

| Insulin | |||

| Baseline, pmol/L | 18.6 ± 8.3 | 21.8 ± 13.9 | 0.18 |

| Peak, pmol/L | 434.8 ± 225.5 | 255.9 ± 157.6 | 0.0004 |

| Peak time, min | 43 ± 15 | 45 ± 15 | 0.74 |

| iAUC0–120, pmol·L−1·min−1 | 21,630 ± 14,467 | 12,794 ± 9,359 | 0.0009 |

| iAUC0–360, pmol·L−1·min−1 | 26,854 ± 18,966 | 20,748 ± 14469 | 0.019 |

| C-Peptide | |||

| Baseline, nmol/L | 0.53 ± 0.14 | 0.52 ± 0.21 | 0.78 |

| Peak, nmol/L | 3.08 ± 0.96 | 2.06 ± 0.79 | <0.0001 |

| Peak time, mi] | 54 ± 17 | 73 ± 35 | 0.034 |

| iAUC0–120, mmol·L−1·min−1 | 184 ± 72 | 107 ± 47 | <0.0001 |

| iAUC0–360, nmol·L−1·min−1 | 278 ± 131 | 227 ± 87 | 0.031 |

| Rameal | |||

| Peak, μmol·kg FFM−1·min−1 | 79.2 ± 25.1 | 38.9 ± 10.6 | 0.0002 |

| Peak time, min | 30 ± 14 | 47 ± 31 | 0.09 |

| iAUC0–120, μmol·kg FFM−1·min−1 | 4,487 ± 909 | 2,658 ± 736 | <0.0001 |

| iAUC0–360, μmol/kg FFM | 6,326 ± 1441 | 5,566 ± 1,165 | 0.13 |

| EGP | |||

| Baseline, μmol·kg FFM−1·min−1 | 14.0 ± 1.5 | 13.2 ± 1.6 | 0.016 |

| Nadir, μmol·kg FFM−1·min−1 | 1.0 ± 3.1 | 1.6 ± 3.0 | 0.39 |

| Nadir time, min | 60 ± 27 | 79 ± 34 | 0.045 |

| iAUC0–120, μmol·kg FFM−1·min−1 | −1,123 ± 323 | −835 ± 283 | 0.002 |

| iAUC0–360, μmol/kg FFM | −2,121 ± 846 | −2,061 ± 801 | 0.70 |

| Rd | |||

| Peak, μmol·kg FFM−1·min−1 | 74.7 ± 15.7 | 43.5 ± 11.3 | <0.0001 |

| Peak time, min | 53 ± 12 | 87 ± 53 | 0.034 |

| iAUC0–120, μmol/kg FFM | 3,606 ± 839 | 1,829 ± 807 | <0.0001 |

| iAUC0–360, μmol/kg FFM | 4,558 ± 1,165 | 3,691 ± 1,099 | 0.018 |

Mean ± SD of basal (if present), peak, time of the peak, and incremental area under the curve in the first 2 and 6 h after the meal (iAUC0–120, iAUC0–360) of glucose, insulin, glucagon, rates of meal carbohydrate appearance (Rameal), endogenous glucose production (EGP), and glucose disappearance (Rd) in both rice and sorghum groups for all subjects. CC, complex carbohydrates; SC, simple carbohydrates.

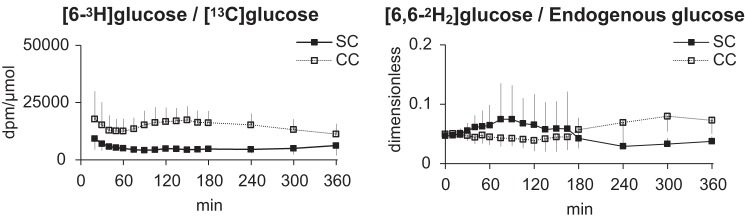

Specific Activities and Tracer-to-Tracee Ratios

Specific activity ratio for the calculation of meal carbohydrate appearance ([6-3H]glucose/[13C]glucose) was virtually constant during the SC meal, while during the CC meal there was mild perturbations during the first hour after meal consumption. On the other hand, the tracer-to-tracee ratio for calculation of endogenous glucose production ([6,6-2H2]glucose/endogenous glucose) showed mild perturbations during the first 3 h after SC meal consumption and in the last 3 ho after CC meal consumption. Furthermore, direct comparisons of the specific activity and tracer-to-tracee ratios between the CC visits revealed minimal intrasubject variability (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Left: mean (±SD) ratio of [6-3H]glucose to [13C] glucose following simple carbohydrate (SC; ■) and complex carbohydrate (CC) meals (☐). Right: ratio of [6,6-2H2]glucose to endogenous glucose following SC (■) and CC meals (☐).

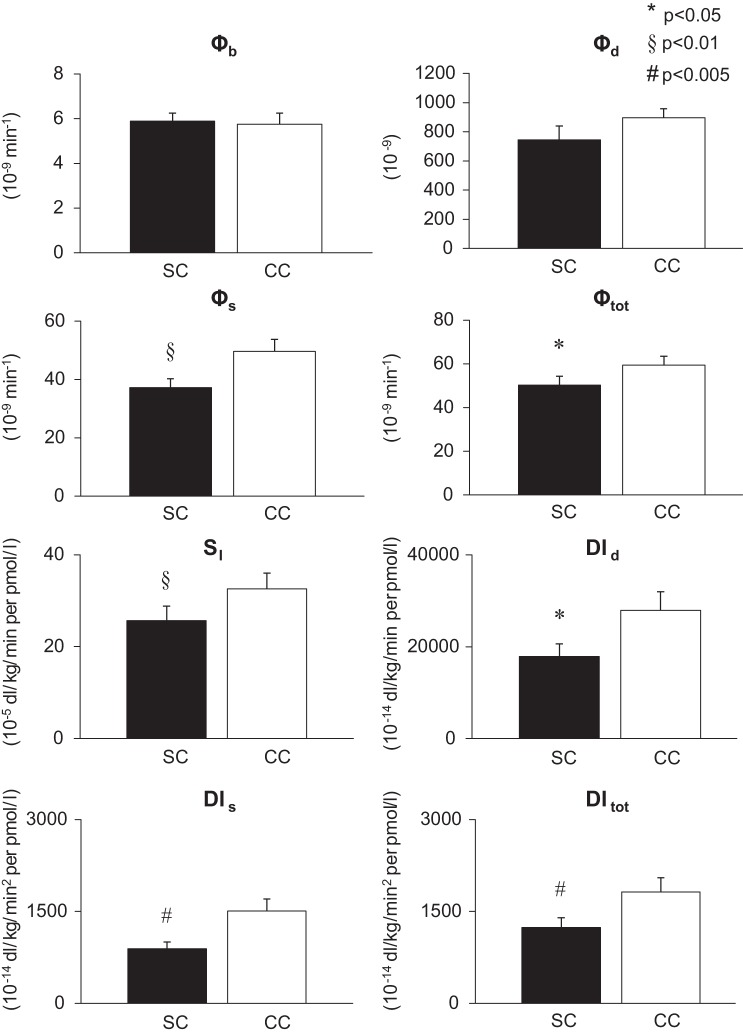

Meal Rate of Appearance, Endogenous Glucose Production, and Rate of Glucose Disappearance

The peak meal rate of appearance was significantly lower and tended to occur later with CC versus SC meal. As a result, the iAUC0–120 was also significantly lower during CC versus SC meal while the iAUC0–360 did not differ. In addition, the fraction of the total amount of glucose absorbed during the meal, expressed as the ratio between iAUC0–360 of Rameal and the carbohydrate load actually administered, was 1.08 ± 0.22 and 1.01 ± 0.21 for SC and CC meals, respectively, hence not significantly different from 1. Basal EGP was slightly but significantly lower in CC than SC and then fell to a similar nadir value with both CC and SC meals. However, EGP suppression during the first 2 h after meal consumption (iAUC0–120) was significantly less with CC than SC meal. Finally, the peak Rd, iAUC0–120, and iAUC0–360 were lower with CC than SC meal while time to peak was delayed with CC than SC meal (Fig. 3, Table 3). (The metabolic clearance rate of glucose for the SC and CC meals is provided in Supplemental Fig. S1. Furthermore, comparison of the minimal model estimated RaMeal vs. the tracer calculated RaMeal is shown in Supplemental Fig. S2. Additional comparisons of the parameters from 0 to 180 min are provided in Supplemental Table S1.

Fig. 3.

Mean (±SD) rates of meal carbohydrate appearance (Rameal; top), endogenous glucose production (EGP; middle), and glucose disappearance (Rd, lower) following mixed meal ingestion with simple carbohydrates (SC; ■) and complex carbohydrates (CC; ☐). FFM, fat free mass.

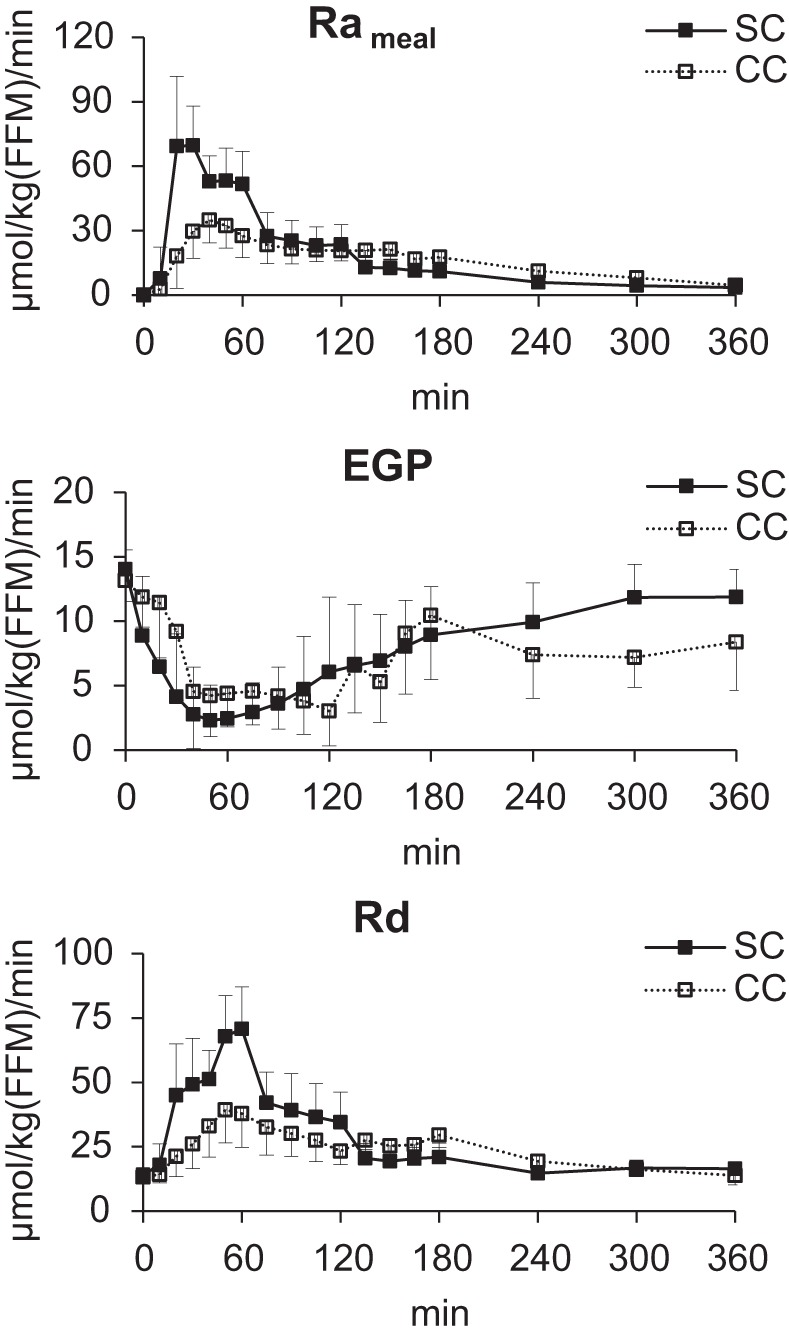

β-Cell Responsivity, Insulin Sensitivity and Disposition Indices

For both SC and CC meals, the oral glucose and C-peptide minimal models were able to predict the data well and precisely estimate model parameters with a clear physiological interpretation. Basal and dynamic responsivity indices were unchanged during CC and SC visits. On the other hand, Φs, Φtot, SI, DId, DIs, and DItot were all significantly higher in CC than SC, in agreement with the finding that during CC meals, glucose was better controlled despite lower circulating insulin concentrations (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Mean (±SE) of β-cell responsivity indices (basal Φb, static Φs, dynamic Φd, and total Φtot), insulin sensitivity and disposition indices (dynamic DId, static DIs, and total DItot) during mixed meal ingestion with simple carbohydrates (SC; ■) and complex carbohydrates (CC; ☐).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have successfully applied the isotope dilution technique to measure postprandial complex carbohydrate turnover using naturally enriched [13C]polysaccharide-labeled commercial grains while maintaining the fundamental premise that requires the biochemical spine of the tracer and tracee to be identical. Additionally, we have been able to demonstrate significant differences in the patterns of postprandial glucose fluxes, postprandial glucose excursions, and indices of insulin sensitivity and β-cell responsivity in the same individuals despite consuming mixed meals with similar calorie and macronutrient compositions.

We have utilized the natural enrichment of [13C]polysaccharide that the plants acquire during CO2 fixation from the atmosphere (C3 plants: rice) or the soil water (C4 plants: sorghum). As anticipated, we observed that the selected C3 grain (rice) was more 13C deplete while the selected C4 grain (sorghum) was less 13C deplete than the typical average American diet. After extensively testing the natural 13C enrichment in commonly available food products, we selected Madagascar pink rice and sorghum as the products that detectably differed from the average 13C enrichment of the standard mixed meals supplied by the Mayo CRTU over the previous decade. While there have been a few prior reports (14, 30) that have utilized the natural abundance of 13C in starches, the investigators utilized the dual tracer technique to estimate postprandial carbohydrate fluxes. Furthermore, these investigators used wheat-based products artificially enriched with 13C by growing the plants in a 13CO2 enriched atmosphere. In contrast, we utilized commercially available food products that are generally available in grocery stores. While the dual tracer technique applied without (37) and with (20) advanced computational methods does provide reasonable estimates of the parameters of postprandial glucose turnover, the triple tracer technique, though analytically intense, likely provides a more accurate estimate of rates of EGP in the postprandial state.

The aim of the triple tracer approach (7) was to minimize fluctuations in tracer-to-tracee ratios to limit non-steady-state calculation errors. To determine Rameal, the ratio of infused tracer [6-3H]glucose to meal tracee [13C]glucose in plasma is used. The tracer-to-tracee ratios during complex carbohydrate meals did not change appreciably after the first 30 min following meal ingestion. Likewise, to calculate EGP, the ratio of infused tracer [6,6-2H2]glucose to endogenous glucose concentration in plasma is used. This ratio during complex carbohydrate meals did not change appreciably for the first 180 min and gently rose thereafter. Therefore, the calculated rates of Rameal and EGP in both groups by the non-steady-state Steele’s method (36) are reliable, with the robustness comparable to published results from other triple tracer studies that have used glucose as the only source of meal carbohydrate (6, 33). Of note, comparing CC versus SC meals, higher values of EGP [8.38 ± 3.75 vs. 11.86 ± 2.18 μmol·kg fat free mass (FFM)−1·min−1 in CC vs. SC, P = 0.0007) and Rd (13.82 ± 3.72 vs. 16.42 ± 2.40 μmol·kg FFM−1·min−1, P = 0.01) are observed at the end of experiment. However, since Rameal appears to be similar in CC versus SC meal at the end of experiment (4.53 ± 4.31 vs. 3.36 ± 2.96 μmol·kg FFM−1·min−1 in CC vs. SC, P = 0.43), these effects are probably attributable to other factors, including ambient concentrations of glucose, glucagon, insulin, or their combined effects. However, further studies are needed to assess the effect sizes of these factors individually.

In contrast to monosaccharides, polysaccharides need to be converted by salivary/pancreatic amylase and intestinal disaccharidases to monosaccharides before absorption in the jejunum (18). Furthermore, the presence of dietary fiber from plant cell walls in polysaccharides slows gastric emptying (9) that in turn delay and attenuate postprandial rise in plasma glucose concentrations. Although the fiber content of the CC meals differed between rice and sorghum, there were no differences in either glucose or hormonal excursions or in the patterns of carbohydrate turnover and indices of insulin secretion and action between the rice and sorghum meals. It is possible though that larger differences in fiber content could have resulted in significant differences in the above outcome variables. It is also noteworthy that our study was not powered to detect differences in the outcome variables between rice and sorghum meals because there were no prior data on the variables using the triple tracer technique with complex carbohydrates.

It is also fundamental to note that this novel triple tracer method for estimating postprandial carbohydrate fluxes after complex carbohydrate ingestion cannot be directly compared within subjects to the triple tracer technique used to estimate postprandial carbohydrate fluxes after simple carbohydrate ingestion. This is because the physiology of carbohydrate digestion is fundamentally different between complex and simple carbohydrate containing meals as noted above. This is a new method that enabled us to measure complex carbohydrate turnover and demonstrate that, as expected, complex carbohydrates are slowly absorbed with respect to simple carbohydrates.

The favorable effects of complex carbohydrates on postprandial plasma glucose excursions are well characterized. Furthermore, population-based analyses (16) and clinical trials (34) have espoused cardiovascular, metabolic, and anthropometric benefits of diets that contain complex (low glycemic index) versus simple (high glycemic index) carbohydrates. A large body of literature (1, 26) has supported the benefits of meals containing low glycemic index carbohydrates on metabolism and risks for cardiovascular disease. A prior study (21) demonstrated the beneficial effects of slowly absorbable carbohydrate containing mixed meal on postprandial plasma glucose and insulin concentrations compared with an isocaloric meal with similar macronutrient composition but containing rapidly absorbable carbohydrates. This study reported that although the integrated postprandial glucose responses were similar between the two meals, the integrated insulin excursions were lower with slowly absorbable than rapidly absorbable carbohydrate containing meal, implying higher insulin sensitivity with slowly absorbable carbohydrate containing meal. Our current study demonstrates lower glucose and insulin excursions for the first 2 h after meal consumption with complex than simple carbohydrates that was in turn due to lower and delayed peak rates of Rameal. It is entirely plausible that the lower RaMeal with CC (statistically lower during 0–120 min and numerically lower during 0–360 min) could be due to enhanced splanchnic glucose uptake with CC than SC meal. Further studies are necessary to test this hypothesis. Rd was also lower during CC meals, but this was more likely due to the lower circulating glucose and insulin concentrations, rather than to a direct defect in glucose disposal. However, further analyses of the postprandial data for the entire 6 h duration reveal that though integrated glucose excursions were slightly but not significantly lower, insulin excursions were significantly lower with complex than simple carbohydrates, implying higher insulin sensitivity with complex than simple carbohydrates. Use of reliable models additionally supported these observations by confirming that when an isocaloric complex versus simple carbohydrate meal is ingested, higher indices of insulin sensitivity (SI), β-cell functions (Φ indices), and disposition indices (DI) are achieved. However, the numerical values of the indices depend upon the test used to assess them. The different metabolic challenge of CC versus SC meal do not imply that overall metabolic indices of glucose control have improved, but simply a higher efficiency of insulin action and secretion in CC versus SC meal, which is translated into higher model parameters in CC versus SC meal.

The pattern of postprandial glucagon excursions in this study was interesting. After SC meal, glucagon concentrations fell in the early postprandial period likely due to the rapid rise in insulin and glucose excursions, followed by a rise in the late postprandial phase due to falling insulin and glucose excursions. In contrast, during CC meal, fluctuations in glucagon concentrations were less dramatic during the 6-h observation period of this study. This was likely due to the slower and modest fluctuations to insulin and glucose excursions with the CC meal.

Like all studies, our study has limitations. From the analytical standpoint of 13C enrichment, it is important to note that the IRMS method measures the total 13C enrichment and not the individual enrichments in each of the 6 carbons of glucose. Hence, if recycling of 13C occurs between the carbon atoms, the main consequence would be an overestimation of [M+1] and [M+2] ions representing the [13C]glucose and [6,6-2H2]glucose. This may result in some confounding effects on estimation of glucose fluxes, in particular, marginal exaggeration of the RaMeal. However, as shown before (38), concentrations of recycled glucose molecules have been estimated to be minimal (~2%) up to 380 min after the start of tracer infusion, hence recycling can be assumed negligible in our experimental settings. Although it is also true that the primary measurement with an IRMS is the molar ratio, most analyses reference the measurement to VPDB. This is to allow this absolute value to be compared with different samples whose measurements may be performed on another day. This analytical approach ensures continuity. In this study, however, we are not examining absolute values but relative to the baseline of the patient (Δ sample – Δ background). The delta value was then converted to MPE assuming that all six carbons in the glucose molecule were enriched. We also calculated the parameters using either molar ratio or MPE. It is important to note that the results did not differ between the two approaches.

It is also important to account for the effect of any natural 13C enrichment in the [6,6-2H2]glucose that is infused. As a separate experiment, we infused [6,6-2H2]glucose without a meal in a subject and did not observe any changes to 13C glucose enrichment before, during, or after stopping the infusion, thus implying that the confounding effects of natural 13C enrichment in the infused [6,6-2H2]glucose, if any, are negligible. Furthermore, the methyl boronate approach was chosen to minimize the number of added carbon atoms in the derivatized molecule. It may be that the added groups that contain carbon may contribute to the 13C signature, but at this time, we do not have a way of determining this. However, to mitigate such variations, all samples were run using the same batch of derivatizing reagents. Future studies are needed to examine the effects, if any, of such an approach.

To summarize, we have demonstrated a novel triple tracer approach to estimate postprandial turnover of complex carbohydrate containing mixed meals using the natural 13C abundance of polysaccharides contained in commercially available food products in healthy nondiabetic adults, finding that the slower pattern of Rameal provides a lower postprandial glucose peak with significant increase in insulin sensitivity and β-cell function. Further studies are necessary using mixed simple and complex carbohydrate containing meals and in those with diabetes to advance the method further.

GRANTS

This work was supported by funds from NIH Grant DK-085516 and DK-094331 to A.B., NIH Grant DK-029953 to R.B., and Grant UL1 TR000135 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science to Mayo Clinic. C.C., C.D.M., and M.S. were partially supported by Italian Ministero dell’Università e della Ricerca Scientifica (Progetto di Ateneo dell’Università di Padova 2014).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

R.B., X.-M.P., R.C., and A.B. conceived and designed research; R.B., L.H., and A.B. performed experiments; R.B., M. Schiavon, X.-M.P., M. Slama, R.C., C.D.M., and A.B. analyzed data; R.B., M. Schiavon, X.-M.P., C.D.M., C.C., and A.B. interpreted results of experiments; R.B., M. Schiavon, C.D.M., and A.B. prepared figures; R.B., M. Schiavon, M. Slama, C.D.M., and A.B. drafted manuscript; R.B., M. Schiavon, M. Slama, C.D.M., C.C., and A.B. edited and revised manuscript; R.B., M. Schiavon, X.-M.P., L.H., M. Slama, R.C., C.D.M., C.C., and A.B. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to the research subjects, the staff of the Mayo CRTU for their superb nursing care and dietetics support, to Barbara Norby and Brent McConahey for assistance with the studies and sample analyses. We gratefully acknowledge valuable suggestions from Dr. Robert A. Rizza during the preparation of this manuscript.

Dr. Ananda Basu is the guarantor who takes full responsibility for the work as a whole, including the study design, access to data, and the decision to submit and publish the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Augustin LS, Kendall CW, Jenkins DJ, Willett WC, Astrup A, Barclay AW, Björck I, Brand-Miller JC, Brighenti F, Buyken AE, Ceriello A, La Vecchia C, Livesey G, Liu S, Riccardi G, Rizkalla SW, Sievenpiper JL, Trichopoulou A, Wolever TM, Baer-Sinnott S, Poli A. Glycemic index, glycemic load and glycemic response: An International Scientific Consensus Summit from the International Carbohydrate Quality Consortium (ICQC). Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 25: 795–815, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2015.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balagopal P, Ljungqvist O, Nair KS. Skeletal muscle myosin heavy-chain synthesis rate in healthy humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 272: E45–E50, 1997. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1997.272.1.E45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bassham JA, Benson AA, Calvin M. The path of carbon in photosynthesis. J Biol Chem 185: 781–787, 1950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Basu A, Dalla Man C, Basu R, Toffolo G, Cobelli C, Rizza RA. Effects of type 2 diabetes on insulin secretion, insulin action, glucose effectiveness, and postprandial glucose metabolism. Diabetes Care 32: 866–872, 2009. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Basu R, Di Camillo B, Toffolo G, Basu A, Shah P, Vella A, Rizza R, Cobelli C. Use of a novel triple-tracer approach to assess postprandial glucose metabolism. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 284: E55–E69, 2003. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00190.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Breda E, Cavaghan MK, Toffolo G, Polonsky KS, Cobelli C. Oral glucose tolerance test minimal model indexes of beta-cell function and insulin sensitivity. Diabetes 50: 150–158, 2001. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.1.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Camilleri M, Colemont LJ, Phillips SF, Brown ML, Thomforde GM, Chapman N, Zinsmeister AR. Human gastric emptying and colonic filling of solids characterized by a new method. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 257: G284–G290, 1989. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1989.257.2.G284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carter JF, Barwick BJ (Editors). Good Practice Guide for Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometry. FIRMS, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cobelli C, Dalla Man C, Toffolo G, Basu R, Vella A, Rizza R. The oral minimal model method. Diabetes 63: 1203–1213, 2014. doi: 10.2337/db13-1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crabb DW, Shetty J. Improving the properties of amylolytic enzymes by protein engineering. Trends Glycosci Glycotechnol 15: 115–126, 2003. doi: 10.4052/tigg.15.115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dalla Man C, Caumo A, Basu R, Rizza R, Toffolo G, Cobelli C. Minimal model estimation of glucose absorption and insulin sensitivity from oral test: validation with a tracer method. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 287: E637–E643, 2004. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00319.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eelderink C, Moerdijk-Poortvliet TC, Wang H, Schepers M, Preston T, Boer T, Vonk RJ, Schierbeek H, Priebe MG. The glycemic response does not reflect the in vivo starch digestibility of fiber-rich wheat products in healthy men. J Nutr 142: 258–263, 2012. doi: 10.3945/jn.111.147884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elleri D, Allen JM, Harris J, Kumareswaran K, Nodale M, Leelarathna L, Acerini CL, Haidar A, Wilinska ME, Jackson N, Umpleby AM, Evans ML, Dunger DB, Hovorka R. Absorption patterns of meals containing complex carbohydrates in type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia 56: 1108–1117, 2013. doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-2852-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferretti F, Mariani M. Simple vs. complex carbohydrate dietary patterns and the global overweight and obesity pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health 14: E1174, 2017. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14101174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Firth R, Bell P, Rizza R. Insulin action in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: the relationship between hepatic and extrahepatic insulin resistance and obesity. Metabolism 36: 1091–1095, 1987. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(87)90031-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gorboulev V, Schürmann A, Vallon V, Kipp H, Jaschke A, Klessen D, Friedrich A, Scherneck S, Rieg T, Cunard R, Veyhl-Wichmann M, Srinivasan A, Balen D, Breljak D, Rexhepaj R, Parker HE, Gribble FM, Reimann F, Lang F, Wiese S, Sabolic I, Sendtner M, Koepsell H. Na(+)-D-glucose cotransporter SGLT1 is pivotal for intestinal glucose absorption and glucose-dependent incretin secretion. Diabetes 61: 187–196, 2012. doi: 10.2337/db11-1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nathan DM, Genuth S, Lachin J, Cleary P, Crofford O, Davis M, Rand L, Siebert C; Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group . The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 329: 977–986, 1993. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309303291401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haidar A, Elleri D, Allen JM, Harris J, Kumareswaran K, Nodale M, Acerini CL, Wilinska ME, Jackson N, Umpleby AM, Evans ML, Dunger DB, Hovorka R. Validity of triple- and dual-tracer techniques to estimate glucose appearance. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 302: E1493–E1501, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00581.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harbis A, Perdreau S, Vincent-Baudry S, Charbonnier M, Bernard MC, Raccah D, Senft M, Lorec AM, Defoort C, Portugal H, Vinoy S, Lang V, Lairon D. Glycemic and insulinemic meal responses modulate postprandial hepatic and intestinal lipoprotein accumulation in obese, insulin-resistant subjects. Am J Clin Nutr 80: 896–902, 2004. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.4.896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hinshaw L, Dalla Man C, Nandy DK, Saad A, Bharucha AE, Levine JA, Rizza RA, Basu R, Carter RE, Cobelli C, Kudva YC, Basu A. Diurnal pattern of insulin action in type 1 diabetes: implications for a closed-loop system. Diabetes 62: 2223–2229, 2013. doi: 10.2337/db12-1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katz H, Homan M, Jensen M, Caumo A, Cobelli C, Rizza R. Assessment of insulin action in NIDDM in the presence of dynamic changes in insulin and glucose concentration. Diabetes 43: 289–296, 1994. doi: 10.2337/diab.43.2.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ketema EB, Kibret KT. Correlation of fasting and postprandial plasma glucose with HbA1c in assessing glycemic control; systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Public Health 73: 43, 2015. doi: 10.1186/s13690-015-0088-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kohn MJ. Carbon isotope compositions of terrestrial C3 plants as indicators of (paleo)ecology and (paleo)climate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 19691–19695, 2010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004933107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Livesey G, Taylor R, Livesey HF, Buyken AE, Jenkins DJA, Augustin LSA, Sievenpiper JL, Barclay AW, Liu S, Wolever TMS, Willett WC, Brighenti F, Salas-Salvadó J, Björck I, Rizkalla SW, Riccardi G, La Vecchia C, Ceriello A, Trichopoulou A, Poli A, Astrup A, Kendall CWC, Ha MA, Baer-Sinnott S, Brand-Miller JC. Dietary glycemic index and load and the risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and updated meta-analyses of prospective cohort studies. Nutrients 11: E1280, 2019. doi: 10.3390/nu11061280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCleary BV, Gibson TS, Mugford DC. Measurement of total starch in cereal products by amyloglucosidase-a-amylase method: collaborative study. J AOAC Int 80: 571–579, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muccio Z, Jackson GP. Isotope ratio mass spectrometry. Analyst (Lond) 134: 213–222, 2009. doi: 10.1039/B808232D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Leary MH. Carbon isotope fractionation in plants. Biochemistry 20: 553–567, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Priebe MG, Wachters-Hagedoorn RE, Heimweg JA, Small A, Preston T, Elzinga H, Stellaard F, Vonk RJ. An explorative study of in vivo digestive starch characteristics and postprandial glucose kinetics of wholemeal wheat bread. Eur J Nutr 47: 417–423, 2008. doi: 10.1007/s00394-008-0743-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Radziuk J, Norwich KH, Vranic M. Experimental validation of measurements of glucose turnover in nonsteady state. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 234: E84–E93, 1978. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1978.234.1.E84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rizza RA, Toffolo G, Cobelli C. Accurate measurement of postprandial glucose turnover: why is it difficult and how can it be done (relatively) simply? Diabetes 65: 1133–1145, 2016. doi: 10.2337/db15-1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saad A, Dalla Man C, Nandy DK, Levine JA, Bharucha AE, Rizza RA, Basu R, Carter RE, Cobelli C, Kudva YC, Basu A. Diurnal pattern to insulin secretion and insulin action in healthy individuals. Diabetes 61: 2691–2700, 2012. doi: 10.2337/db11-1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sacks FM, Carey VJ, Anderson CA, Miller ER III, Copeland T, Charleston J, Harshfield BJ, Laranjo N, McCarron P, Swain J, White K, Yee K, Appel LJ. Effects of high vs low glycemic index of dietary carbohydrate on cardiovascular disease risk factors and insulin sensitivity: the OmniCarb randomized clinical trial. JAMA 312: 2531–2541, 2014. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.16658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Slack CR, Hatch MD. Comparative studies on the activity of carboxylases and other enzymes in relation to the new pathway of photosynthetic carbon dioxide fixation in tropical grasses. Biochem J 103: 660–665, 1967. doi: 10.1042/bj1030660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Steele R, Wall JS, De Bodo RC, Altszuler N. Measurement of size and turnover rate of body glucose pool by the isotope dilution method. Am J Physiol 187: 15–24, 1956. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1956.187.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Toffolo G, Basu R, Dalla Man C, Rizza R, Cobelli C. Assessment of postprandial glucose metabolism: conventional dual- vs. triple-tracer method. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 291: E800–E806, 2006. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00461.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Toffolo G, Dalla Man C, Cobelli C, Sunehag AL. Glucose fluxes during OGTT i7n adolescents assessed by a stable isotope triple tracer method. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 21: 31–45, 2008. doi: 10.1515/JPEM.2008.21.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33) [Erratum in Lancet 4:602.]. Lancet 352: 837–853, 1998. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)07019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Relative efficacy of randomly allocated diet, sulphonylurea, insulin, or metformin in patients with newly diagnosed non-insulin dependent diabetes followed for three years BMJ 310: 83–88, 1995. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6972.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]