Abstract

The auditory brain stem response (ABR) is an evoked potential that indexes a cascade of neural events elicited by sound. In the present study we evaluated the influence of sound frequency on a derived component of the ABR known as the binaural interaction component (BIC). Specifically, we evaluated the effect of acoustic interaural (between-ear) frequency mismatch on BIC amplitude. Goals were to 1) increase basic understanding of sound features that influence this long-studied auditory potential and 2) gain insight about the persistence of the BIC with interaural electrode mismatch in human users of bilateral cochlear implants, presently a limitation on the prospective utility of the BIC in audiological settings. Data were collected in an animal model that is audiometrically similar to humans, the chinchilla (Chinchilla lanigera; 6 females). Frequency disparities and amplitudes of acoustic stimuli were varied over broad ranges, and associated variation of BIC amplitude was quantified. Subsequently, responses were simulated with the use of established models of the brain stem pathway thought to underlie the BIC. Collectively, the data demonstrate that at high sound intensities (≥85 dB SPL), the acoustically elicited BIC persisted with interaurally disparate stimulation (click frequencies ≥1.5 octaves apart). However, sharper tuning emerged at moderate sound intensities (65 dB SPL), with the largest BIC occurring for stimulus frequencies within ~0.8 octaves, equivalent to ±1 mm in cochlear place. Such responses were consistent with simulated responses of the presumed brain stem generator of the BIC, the lateral superior olive. The data suggest that leveraging focused electrical stimulation strategies could improve BIC-based bilateral cochlear implant fitting outcomes.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Traditional hearing tests evaluate each ear independently. Diagnosis and treatment of binaural hearing dysfunction remains a basic challenge for hearing clinicians. We demonstrate in an animal model that the prospective utility of a noninvasive electrophysiological signature of binaural function, the binaural interaction component (BIC), depends strongly on the intensity of auditory stimulation. Data suggest that more informative BIC measurements could be obtained with clinical protocols leveraging stimuli restricted in effective bandwidth.

Keywords: auditory brain stem response, binaural hearing, binaural interaction, cochlear implants

INTRODUCTION

Evoked potentials enable noninvasive assessment of sensory function. The auditory brain stem response (ABR) is an evoked potential elicited via repeated presentation of brief sounds and measured via electrodes placed on the scalp (Jewett et al. 1970). The ABR consists of a sequence of voltage peaks that index summating activity of neurons along the ascending auditory pathway. ABR measurements are widely applied in clinical and research settings to assess hearing function in humans (Stapells and Oates 1997). Over the past several decades, a derived component of the ABR, the binaural interaction component (BIC), has generated interest as a prospective biomarker of binaural hearing (Dobie and Berlin 1979; Laumen et al. 2016). The BIC is derived by measuring monaural (left and right ear) ABRs, summing the result, and subtracting this sum from the ABR elicited via binaural stimulation (see Fig. 1). The most prominent feature of the difference waveform is a negative peak indicating a smaller binaural response (known as DN1; see Fig. 1). The latency of the BIC and its dominant negative peak are consistent with inhibitory processes within the lateral superior olive of the pons (LSO; Benichoux et al. 2018; Ungan et al. 1997). Further suggestive of a binaural origin, BIC amplitude is modulated by the binaural cues to sound location: interaural time and level differences (ITD and ILD, respectively; e.g., Furst et al. 1990).

Fig. 1.

A: a midline electrode montage was used to record auditory brain stem response (ABR) waveforms elicited by unilateral or bilateral stimulation with one-third-octave Gabor clicks. The stimulus to the left ear was always 4 kHz; the stimulus to the right ear was varied in center frequency (and thus duration) parametrically. GND, ground electrode. B: left (L), right (R), and binaural waveforms were recorded independently. The monaural ABR sum [mono sum (L + R)] was then computed and subtracted from the binaural ABR (bin) to derive the binaural interaction component (BIC). A standard index of BIC amplitude is the value of the most prominent negative deflection (peak DN1); we instead computed root-mean-square amplitude (see text).

Although a few human studies have demonstrated modulation of the BIC with changes in binaural cues (Furst et al. 1990; Riedel and Kollmeier 2006) or even linked reduced BIC with spatial hearing deficits (Gunnarson and Finitzo 1991), human BIC is small in amplitude (~0.1–0.2 µV), requiring several thousand stimulus repetitions to obtain reliable averaged responses. Some authors have reported an inability to measure BIC at all, even in normal-hearing subjects (Haywood et al. 2015). A notable exception is in the field of cochlear implants, where electrically evoked BIC has been linked with binaural hearing outcomes in human bilateral cochlear implantees (Gordon et al. 2012; He et al. 2012; Hu and Dietz 2015; Hu et al. 2016; Pelizzone et al. 1990), bearing an apparent relation to ITD sensitivity in the auditory midbrain (in cat; Hancock et al. 2010; cf. Smith and Delgutte 2007). In one promising study, BIC amplitude predicted bilateral cochlear implant behavioral performance better than standard pitch-based perceptual measures (Hu and Dietz 2015): the binaural electrode pair producing the largest-amplitude BIC also yielded the best behavioral sensitivity to ITD, the dominant binaural cue in acoustic hearing. However, reported tuning curves (BIC amplitude vs. electrode disparity) have typically been broad, with little differentiation of BICs elicited by electrode pairs millimeters apart (representing potentially thousands of Hertz in equivalent cochlear place; Greenwood 1990). The reason for such broad tuning is unclear, because the influence of interaural frequency mismatch on the acoustically elicited BIC is unknown. Broad tuning functions could arise from electrical current spread within the cochlea (Kral et al. 1998), resulting in effectively broadband stimulation and large binaural overlap across electrode positions. However, in an animal study, little difference in BIC tuning was observed between broad (monopolar) and more focused (bipolar) electrical stimulation (Smith and Delgutte 2007), raising the possibility that the neural circuit that produces the BIC is intrinsically tolerant to interaural mismatch. In support of this possibility, recordings from LSO (in gerbil; Sanes and Rubel 1988) show that the frequency matching of excitatory and inhibitory inputs is inexact (see results and discussion).

The present study evaluated the influence of interaural frequency mismatch on acoustically elicited BIC in an animal model audiometrically similar to humans, the chinchilla. This preparation enabled dense sampling of the frequency mismatch-by-level stimulus space. Results demonstrate that the acoustic BIC is broadly tuned at high stimulus intensities but sharply modulated by frequency mismatch at moderate intensities (e.g., 65 dB SPL). Such modulation was reproduced with the use of an LSO model that included physiologically constrained variation of excitatory and inhibitory frequency tuning. Implications for clinical use of the BIC are considered.

METHODS

Ethics statement.

All experimental procedures complied with guidelines set forth by the National Institutes of Health and were approved under a protocol submitted to the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center Animal Care and Use Committee [#B-73515(11)1D].

ABR measurements.

Data were obtained from 6 adult female (500–660 g) long-tailed chinchillas (Chinchilla lanigera). Animals were anesthetized initially with intramuscular injections of ketamine HCl (KetaVed; 22.5 mg/kg) and xylazine HCl (TranquiVed; 5 mg/kg). An anesthetized preparation was used because of the extensive battery of conditions tested (long recording sessions) and to avoid measurement artifacts caused by animal or electrode contact repositioning (see Ferber et al. 2016). Ketamine-xylazine effects on ABRs are minimal (e.g., Ruebhausen et al. 2012). Hair was removed from the top of the head along the midline to enable visualization of the bullae, which served as landmarks for electrode placement. Three platinum subdermal electrodes (model F-E2; Grass Technologies) were placed in a midline montage: the active electrode was positioned between the bullae, the reference was positioned at the nape of the neck, and the ground electrode was positioned in the left hind paw (Fig. 1). Supplementary anesthesia was given at regular intervals, and body temperature was maintained throughout testing at 37°C by use of a recirculating hot water pad (model HTP-1500; Adroit Medical Systems). Blow-by oxygen was provided throughout testing; heart rate and blood oxygen level were monitored via a pulse oximeter attached to the right hind paw. At the conclusion of testing procedures, which generally lasted 10–12 h, animals were euthanized with an intracardiac injection of pentobarbital sodium (Euthasol).

Experiments were completed in a double-walled sound-attenuating chamber (Industrial Acoustics). Acoustic stimuli were generated in MATLAB, synthesized at 44,100 Hz with 24-bit resolution using a USB-connected digital-to-analog converter (FireFace UCX; RME), and presented via insert earphones (Etymotic ER-2) with custom-fit foam tips, which provided a spectrally flat response (in magnitude and phase) from ~200 to 10,000 Hz (cf. Beutelmann et al. 2015; cf. Elberling et al. 2012). ABRs were elicited via repeated presentation of narrowband Gabor click stimuli (cosine × Gaussian envelope; e.g., Brown and Tollin 2016; nominal one-third octave, ~10 cycles of the carrier cosine). In most measurements, the center frequency of the click to the left ear was fixed at 4,000 Hz while the center frequency of the click to the right ear was varied parametrically (click duration thus also varied, given the fixed one-third-octave bandwidth). Testing was completed binaurally at other frequencies in a few cases, as described in results. The frequency of the right ear was varied over a ±1.5-octave range (9 frequencies total: ±1.5, ±1, ±1/3, ±1/6, 0 octaves re: 4,000 Hz), resulting in right ear click center frequencies from 1,414 to 11,314 Hz. Binaural intensity was varied across a 70-dB SPL range (nominal levels 25–95 dB SPL), although not all intensities were tested in all animals. Because narrowband Gabor clicks include several periods of the enveloped tone, nominal stimulus level (in dB SPL) was defined according to the root-mean-square (RMS) level (re: 20 µPa) of a sinusoid with equivalent peak amplitude (i.e., the peak was 3 dB above the nominal value). In practice, this definition yields slightly higher values than would be obtained by RMS averaging of the full Gabor waveform (which includes many small-amplitude samples on the fringes of the envelope) but lower values than would be obtained by taking the peak value alone, as for broadband transients. Within testing blocks, click frequencies and intensity were fixed; the ordering of frequencies and intensities was randomized within each animal. Signals inside each ear canal were verified before testing and were monitored online using probe microphones (Etymotic ER-7C), with probe tubes threaded through the inserted foam ear tips. The intensity (in dB SPL) was equal in the two ears, although an asymmetry of 9–10 dB was present when the right-ear test frequency was 11,314 Hz (left ear fixed at 4,000 Hz), which was slightly beyond the upper limit (~10,000 Hz) of “flat” ER-2 output. Thus, throughout, the observed level at 11,314 Hz was ~9–10 dB below the nominal level (our playback system did not readily allow for additional gain, and, as will be shown, this data point is generally beyond the spectral region of interest). For each frequency-by-intensity combination, at least 1,000 stimulus repetitions (typically 1,500) were presented within each of the three conditions required for BIC measurement (left alone, right alone, and binaural). The electrode signal was amplified (10,000×; ISO-80 system; World Precision Instruments) and recorded at a 44,100-Hz sampling frequency with 24-bit resolution (FireFace UCX). Accumulating average traces for left, right, and binaural presentation were viewed online. Following verification of reproducible ABR waveforms at 4,000 Hz at intensities ≥65 dB SPL, frequency-by-intensity blocks were completed in randomized order.

Data were analyzed offline using MATLAB scripts that computed cross-trial averaged waveforms for each condition [frequency × intensity × ear(s) of presentation]. The BIC waveform was computed from averaged traces by subtracting the monaural ABR sum from the binaural ABR. The amplitude of the BIC waveform can be defined by several metrics, most simply (and commonly) as a raw peak or peak-to-peak value (in µV). However, this approach is subject to bias dependent on the peak-picking algorithm/method used and discards secondary peaks and other reproducible features that may be present and informative. To address these issues, Benichoux et al. (2018) proposed a cross-correlation approach that is agnostic to the morphology of the BIC and reliably detects deflections occurring at shifted latencies (e.g., due to the imposition of large-stimulus ITDs). Although this approach was suitable for follow-up experiments involving ITD manipulations (see results), the bulk of our experiments featured variation of stimulus frequency, which fundamentally altered the ABR/BIC waveform, yielding low correlations even when large-amplitude BICs were present. To deal with this issue, we adopted a different but similarly agnostic metric, the RMS amplitude of the BIC waveform in the temporal window between 3 and 9 ms post-onset, which captured the BIC for all frequencies evaluated (including longer duration BICs driven by low-frequency stimuli; see results). Similar RMS-based analyses of BIC have been used in prior BIC studies (Gordon et al. 2012; He et al. 2010, 2012). Last, the RMS amplitude of the prestimulus waveform was subtracted from the RMS amplitude of the BIC to express BIC amplitude above the noise inherent in computed waveforms. If the BIC RMS was not greater than the noise RMS, it was assigned a value of 0.

Simulation of frequency-dependent BIC.

Recent evidence strongly suggests that the BIC reflects excitatory-inhibitory interactions in the LSO, one of the major nuclei of the superior olivary complex of the pons (Benichoux et al. 2018; Ungan et al. 1997). We simulated such interactions using a combination of two established phenomenological auditory models. First, Gabor click stimuli were passed through the auditory nerve (AN) model of Zilany et al. (2009, 2014). The output of this model is a simulated peristimulus time histogram (PSTH). Responses were generated for nominal “left” and “right” ears. Although the stimulus to the left ear was fixed at 4,000 Hz (as in the ABR experiments), stimuli of sufficiently high intensity would be expected to excite off-frequency fibers as well (tested intensities followed the values used in empirical BIC measurements, 25–95 dB SPL). Stimulus frequency in the right ear was explicitly mismatched from −1.5 to +1.5 octaves re: 4,000 Hz (also following the values used in empirical BIC measurements), leading to excitation across many frequencies depending on the mismatch condition and stimulus level. Thus, for both left and right ears, AN model simulations were completed for 11 characteristic frequencies spanning the range from 1,260 to 12,699 Hz (ANSI S1.11-2004 one-third-octave band values; American National Standards Institute 2004), yielding sets of left- and right-ear Gabor-elicited PSTHs.

AN responses were simulated for three “populations” of low-, medium-, and high-spontaneous-rate AN fibers (200 fibers of each type). Responses were generated using a single stimulus repetition. The populations were then randomly sampled (with replacement) to generate inputs to the “coincidence-counting” LSO model of Ashida et al. (2016), as described below. Selected AN model parameters are given in Table 1. Note that the AN model employed cat auditory filter widths, which closely follow filter widths in chinchilla (Verschooten et al. 2018).

Table 1.

Summary of model parameters employed for simulation of the binaural interaction component

| Auditory Nerve Fibers (Zilany et al. 2014) | Lateral Superior Olive (Ashida et al. 2016) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| species | 1 (cat) | spEx | Summated AN PSTH for “ipsi” ear* |

| nrep | 1 (no. of stimulus repetitions) | spIn | Summated AN PSTH for “contra” ear* |

| noiseType | 1 (variable noise) | Tref | 1.6 ms (refractory period) |

| implnt | 0 (approximate power law) | WiEx | 0.8 or 0.4 ms (duration of excitation) |

| cihc | 1.0 (healthy inner hair cells) | WiIn | 1.6 or 0.8 ms (duration of inhibition) |

| cohc | 1.0 (healthy outer hair cells) | ThEx | 8 (threshold no. of excitatory inputs) |

| psthbinwidth | 100 µs (PSTH bin width) | ThIn | 2 (threshold increase by inhibition) |

Listed parameters were kept constant across model iterations. For the auditory nerve (AN) model, fiber characteristic frequencies and spontaneous rates were varied as described in the text. For the lateral superior olive (LSO) model, the number of excitatory and inhibitory fibers used to generate input spike vectors was also varied as described in the text.

Spike vectors had the same temporal resolution as AN model peristimulus time histograms (PSTHs; 100-µs bin size) and were assigned an “excitatory” or “inhibitory” value depending on whether the nominal “left” or “right” model LSO was being considered.

See cited sources for additional interpretation of model parameters. contra, contralateral; ipsi, ipsilateral.

AN model outputs from frequency-matched channels were used as inputs to the coincidence-counting LSO model of Ashida et al. (2016). Like other LSO models (e.g., Wang and Colburn 2012), this model assumes that competitive excitatory and inhibitory inputs interact within a brief temporal window of integration. The model was previously shown to predict LSO single-unit electrophysiological data obtained with variation of stimulus ITDs and ILDs (Ashida et al. 2016, 2017). In the present case, “excitatory” and “inhibitory” inputs consisted of PSTHs (in units of spike count per 100-µs time bin) generated by summating responses across a specified number of AN fibers within each of the 11 simulated frequency channels. For simulation of the left LSO, the left ear input was assigned excitatory value and the right ear input (AN PSTH) was assigned inhibitory value. For simulation of the right LSO, these values were reversed.

The temporal window of excitatory-inhibitory interaction is determined by the effective durations of excitatory and inhibitory postsynaptic inputs. We initially applied values of 0.8 and 1.6 ms, respectively, which are the default values adopted by Ashida et al. (2016) and agree well with observations reported in the literature (e.g., Sanes 1990). In light of recent reports suggesting that the effective integration window may be somewhat shorter in LSO principal cells (Franken et al. 2018), we also evaluated excitatory and inhibitory durations of 0.4 and 0.8 ms, respectively. These values were intended to define a “lower bound” on the temporal integration window and were expected to reveal any major effects of varied integration time occurring within a physiologically reasonable range (Franken et al. 2018; Sanes 1990). [Note: compared with the influence of frequency mismatch and input number (below), effects of this parameter generally proved slight.]

Another intuitively important parameter is the number of excitatory and inhibitory inputs to the model neuron, which naturally biases its tendency toward excitation (spiking output) vs. inhibition (no output). In a study of gerbil LSO, Sanes (1990) reported an average of 8 inhibitory inputs and at least 10 excitatory inputs but noted the likelihood of additional excitatory inputs that would not have been detected by the assay employed. The model(s) of Ashida et al. (2016, 2017) used values of 8 inhibitory and 20 excitatory inputs. In a more recent study, Gjoni et al. (2018) examined excitatory and inhibitory input numbers in mouse LSO (C57Bl6 strain), finding evidence for 5 or 6 inhibitory inputs and ≥20 excitatory inputs per LSO neuron. Considering 20 to be a lower bound, the authors proceeded to model LSO responses with 40 excitatory inputs and 8 inhibitory inputs. We evaluated the influence of excitatory input number variation systematically, using values of 10, 20, or 40 excitatory inputs (AN fibers) against 8 inhibitory inputs (see results).

Because inputs to LSO are spontaneously active (e.g., Franken et al. 2018; Joris et al. 1994, Joris and Yin 1998), we also considered the influence of input spontaneous rate by sampling the three different populations of modeled AN nerve fibers in three different proportions: 1) 0.0, 0.0, and 1.0, denoting 0% low, 0% medium, and 100% high spontaneous rate; 2) 0.0, 1.0, and 0.0, denoting 100% medium spontaneous rate; and 3) 0.1, 0.3, and 0.6, denoting 10% low, 30% medium, and 60% high spontaneous rate (approximating the distribution observed in the AN itself; see Schmiedt 1989). These proportions were applied to the total number of excitatory (10, 20, 40) and inhibitory (8) inputs, defining the integer number (after rounding) of AN fibers subsampled from each of the three spontaneous rate populations. Although it is clear that inputs to LSO are spontaneously active, the distribution of rates, or the correspondence of these rates to the fiber types described in the AN, is unclear. Nonetheless, considering a variety of spontaneous rate distributions enabled evaluation of spontaneous rate interactions with other dimensions of the simulation.

Finally, a fundamentally different kind of parameter was considered: the characteristic frequency (CF) of inputs to the model LSO neuron. Empirical data suggest that the CFs (and thus the presumed cochlear origins) of excitatory and inhibitory inputs to the LSO are generally well matched (Boudreau and Tsuchitani 1968; Sanes and Rubel 1988; see Tollin 2003 for review) and thus that simulating interaction within each of the 11 channels with the assumption of frequency-matched inputs is a reasonable first approach. However, the matching of input CFs to individual LSO neurons is not exact: across a population of 85 neurons in the adult gerbil LSO (Sanes and Rubel 1988), excitatory and inhibitory input CFs varied over a roughly 0.4-octave range. To account for this natural variation in fiber input CF, which would necessarily interact with variation in stimulus frequency, we explicitly considered the effect of random variation of nominal excitatory and inhibitory fiber CF. Selected LSO model parameters are given in Table 1.

In all cases, to generate an analog of the BIC, the AN/LSO simulation was completed twice, yielding one response for the “left LSO” and another for the “right LSO” for each the 11 frequency channels simulated. These responses were summed (across channels and then across LSOs) to simulate the ensemble response that would be indexed in an evoked potential recording. As for ABR measurements, model responses were computed for left monaural, right monaural, and binaural stimulation (note: monaural simulations still included 2 “ears” to capture any influence of spontaneous activity in the unstimulated ear). The simulated BIC was derived by subtracting the monaural sum from the binaural response; as in empirical measurements, BIC amplitude was taken as the RMS of this difference. These steps were completed 200 times at each combination of frequency mismatch and intensity that was tested empirically to generate a mismatch-by-level response map. Absolute response amplitudes were meaningless in this context; rather, the goal was to evaluate modulation (“tuning”) of BIC amplitude as a function of stimulus frequency mismatch and level in simulated vs. observed responses.

Several features of the simulation as constructed differ from the architecture of the LSO pathway (e.g., cochlear nucleus and medial nucleus of the trapezoid body processing stages were not explicitly simulated). Although frequency-tuning properties of AN fibers and the neurons that serve as inputs to LSO (bushy cells of the cochlear nucleus and principal cells of the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body) are similar (Koka and Tollin 2014), their temporal response properties (and spontaneous rate profiles) are expected to differ somewhat (Joris and Yin 1998; Koka and Tollin 2014). Nonetheless, the simulation as constructed included the components essential to probe the influence of interaural frequency mismatch on excitatory-inhibitory binaural interaction, and parameters thought likely to influence simulation results were varied over physiologically plausible ranges rather than selecting single parameter values.

Experimental design and statistical analysis.

Data were obtained from six animals, a number sufficient to capture across-animal and test-retest variance in the BIC (in chinchilla; Ferber et al. 2016). Because all animals were female, sex was not considered as a variable. Although influences of stimulus frequency and intensity are not expected to vary strongly between sexes, sex can influence some aspects of ABR and BIC morphology (see Laumen et al. 2016) and may be an appropriate variable to consider in a future study. BIC analysis was automated using RMS amplitude or cross-correlation calculations rather than relying on subjective peak picking. Standard signal processing techniques for data postprocessing, calculation of descriptive statistics, and BIC simulation (Ashida et al. 2016; Zilany et al. 2009, 2014) were all implemented using MATLAB. Simulation data were compared against empirical data with the use of a simple R2 metric, i.e., the squared correlation of simulated and empirically measured BIC values across a defined set of stimulus conditions.

RESULTS

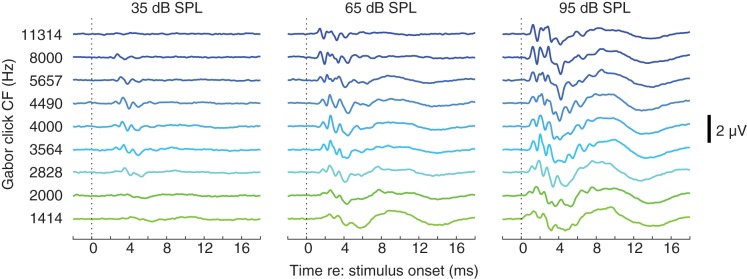

Variation of monaural response characteristics across frequency and level.

In the course of evaluating the influence of frequency disparity on BIC amplitude, we obtained monaural ABRs from each animal across nine frequencies at several different intensities. Example waveforms from a single animal recorded at three different intensities across all test frequencies are shown in Fig. 2. The nominal onset time is operationally defined as the time at which the stimulus envelope exceeded −20 dB re: peak (due to the relatively long duration of narrowband Gabor envelopes at lower frequencies, referencing the first nonzero sample would have resulted in exaggerated latency values). At low-to-moderate intensities, lower frequency stimuli yielded greater response latency, as expected because greater cochlear delay is incurred with more apical cochlear stimulation (cf. Gorga et al. 1988; Lewis et al. 2015; Rasetshwane et al. 2013). Within each frequency, increasing stimulus intensity led to decreasing response latency, because 1) the stimulus envelope effectively crossed the “threshold” amplitude earlier given the higher amplitude scaling factor and 2) nominal “low-frequency” stimulation spread to increasingly basal regions of the cochlea (see Rasetshwane et al. 2013). At the highest tested intensities (85–95 dB SPL), response latency was similar across frequency, and the ABR waveform took on a notably multipeaked morphology; one-third-octave Gabor clicks convey multiple (~10) cycles of the carrier signal, potentiating convolution of multiple auditory responses, particularly at high levels for which several carrier cycles are likely to be well above threshold. Despite the change in waveform morphology, the rationale for BIC calculation remains the same as for traditional (e.g., transient-elicited) ABR waveforms, and, as described below, a BIC was readily obtained from such waveforms.

Fig. 2.

Example auditory brain stem response waveforms from a single animal for 9 different frequencies (rows) across 3 different intensities (columns). All waveforms were elicited by monaural (right ear) stimulation. Vertical dashed line indicates the nominal stimulus onset. Vertical scale bar, 2 µV. CF, center frequency.

Binaural interaction elicited using Gabor click stimuli.

The BIC was readily elicited in all six animals of the present study. A BIC waveform was generally evident in the online accumulating average after a few hundred trials or less. Figure 3A shows the ABR and BIC waveforms elicited at 65 dB SPL with frequency-matched stimuli (4,000 Hz bilaterally) for each animal (S1–S6). Variation of ABR and BIC waveform morphology across animals is typical (e.g., Ferber et al. 2016), but each BIC waveform included an initial negative deflection. The magnitude of this deflection varied from 0.27 µV (S5) to 0.56 µV (S1; mean = 0.38 µV). Although this deflection resembled the DN1 peak evaluated in many previous BIC studies (see Laumen et al. 2016), changes in BIC morphology across frequency, including multiple peaks in many cases, suggested the need for a more comprehensive metric. Therefore, we used RMS BIC amplitude, a measure that makes no assumptions about waveform morphology (see methods). For the traces shown in Fig. 3A, RMS amplitude varied across animals from 0.05 to 0.13 µV (mean = 0.08 µV). These values served as reference values for normalization in cross-subject analyses (see below).

Fig. 3.

A: auditory brain stem responses (ABRs) and derived binaural interaction components (BIC) for each animal in the present study (S1–S6) at 65 dB SPL in the frequency-matched condition (4-kHz Gabor click to both ears). Blue traces are the ABR for monaural presentation to the left ear (L); red traces are the ABR for monaural presentation to the right ear (R); magenta traces are the binaural ABR (B); dashed red and blue traces are the sum of left and right ABRs (L+R); black trace is the BIC; and gray shaded region indicates the temporal window over which BIC amplitude (root mean square) was computed (3–9 ms; see methods). Vertical scale bar, 1 µV. B: BIC across frequency-mismatch conditions at 65 dB SPL for a single animal (S1); each panel shows the L, R, B, and L+R ABRs and the derived BIC for presentation of a Gabor click at the given frequency in the right ear and presentation of a 4-kHz Gabor click in the left ear. C: BIC across 3 levels of frequency mismatch (columns) and 3 nominal sound intensities (rows) in a single animal (S1). Vertical scale bar, 2 µV.

Figure 3B shows the effect of interaural frequency mismatch on the ABR and BIC across all nine tested mismatches (−1.5 to +1.5 octave) at 65 dB SPL for a single animal (S1). The BIC decreased with increasing frequency mismatch but persisted to mismatches of at least ± 0.5 octave (2,828 and 5,657 Hz), representative of the pattern observed in other animals. At higher intensities (e.g., 95 dB SPL; Fig. 3C, top row), the BIC persisted at all tested mismatches, including ± 1.5 octave (1,414 and 11,314 Hz). At low intensities, BIC amplitude decreased, approaching the noise floor even in the frequency-matched condition (e.g., 35 dB SPL; Fig. 3C, bottom row).

Figure 4A plots BIC amplitudes across frequency at three different intensities for each animal. Reproducing the pattern shown in Fig. 3C, the BIC was greatest in amplitude but weakly modulated by frequency mismatch at high stimulus intensities (85–95 dB) and lowest in amplitude, approaching the noise floor in most cases, at low stimulus intensities (35–45 dB). Similarly, calculation of BIC signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), given by signal variance for the 3- to 9-ms window of BIC calculation vs. noise variance for the recording window preceding stimulus presentation, revealed relatively large BIC SNR on the order of 10–20 dB at the highest stimulus intensities (85–95 dB SPL) across a broad range of frequency mismatches. Values decreased to 3–6 dB at the lowest intensities (25–35 dB SPL), with lesser values (and signal variance generally not significantly above noise variance, as assessed by an F-test) for most frequency-mismatched stimuli. A summary normalized response map using the values in Fig. 4A is given in Fig. 4B, showing broad “tuning” (high mismatch tolerance) of the BIC at higher intensities but relatively sharper tuning at intermediate intensities. The moderate intensity of 65 dB SPL yielded BIC modulation across frequency mismatch in all six animals, a result summarized in Fig. 4C, which shows average normalized BIC tuning (RMS amplitude re: on-frequency at 65 dB SPL). This tuning function was quite consistent across animals (±1 SD). The half-width of the averaged function was ~0.8 octave, at a reference frequency of 4,000 Hz, representing ~2,250 Hz and ±1 mm in cochlear extent (in chinchilla; Eldredge et al. 1981).

Fig. 4.

A: BIC amplitudes (root mean square, RMS) across frequency for 3 intensities (rows) for each animal (S1–S6). Larger downward values indicate greater BIC amplitude. Vertical scale bar, 0.2 µV. B: BIC amplitude across all frequencies and intensities normalized within subjects to the value obtained at 65 dB in the frequency-matched condition (open circle at center). Shaded points represent cross-subject averages, with darker shades representing greater BIC amplitudes. The size of each point reflects the number of animals tested and reflected in the average (n = 2, 4, or 6 animals; see inset legend). Contour lines reflect the cross-subject weighted BIC tuning function [weights according to number of animals per data point; contour interval = 0.25 normalized units, with the lightest shaded contour approximating the values yielding 0.25 (25%) of the BIC amplitude observed at 65 dB in the frequency-matched condition]. C: because BIC modulation appeared sharpest at intermediate levels (B), “tuning” at 65 dB SPL was evaluated for each animal by normalizing amplitudes at each frequency to the amplitude recorded for the frequency-matched condition (black trace is mean; gray shading indicates ±SD).

Evaluating the influence of ITD variation on amplitude of Gabor click-elicited BIC.

The constant one-third-octave bandwidth of our Gabor stimuli dictated that click envelopes varied in duration with changes in center frequency. Stimuli were presented such that the amplitude peaks of the click envelopes were aligned, considered to reflect 0-µs ITD. However, in this arrangement, the leading and falling edges of spectrally mismatched envelopes were unavoidably asynchronous such that a nonzero effective ITD existed on the envelope flanks. ITD is known to influence BIC amplitude: specifically, nonzero ITDs lead to reduced BIC amplitude (see introduction). It was therefore important to evaluate the influence of nonzero ITDs on measured BIC amplitudes for our Gabor stimuli. This was achieved in two additional sets of measurements.

First, to demonstrate the influence of ITD on the Gabor-elicited BIC, also demonstrating that a BIC could be elicited at “matched” frequencies other than 4,000 Hz, Fig. 5A shows ABR and BIC waveforms obtained using an 8,000-Hz Gabor click across variation of click ITD (−1,000, 0, and +1,000 µs), where negative values denote that the left ear led in time). Figure 5B plots BIC amplitude across nine ITDs (±1,500, ±1,000, ±500, ±250, and 0 µs) for two animals using the same 8,000-Hz stimulus (similar data were obtained at 4,000 Hz). Here, amplitudes were computed after the cross-correlation method of Benichoux et al. (2018). Briefly, the BIC waveform at 0-µs ITD (e.g., Fig. 5A, middle) was cross-correlated with the BIC waveform obtained at all measured ITDs. The peak value of the cross-correlation function obtained at each ITD was then normalized to the value obtained at 0 µs. This method, which could not be used for our frequency-mismatch analyses because of frequency-related changes in the morphology of the BIC waveform, successfully detects reproducible BIC features across ITD-induced changes in amplitude and latency (Benichoux et al. 2018). A decrease in BIC amplitude was evident at nonzero ITDs as expected and consistent with many previous reports of studies using broadband transients (cf. Furst et al. 1990; see Laumen et al. 2016). The width of the ITD-BIC function was also similar to that measured in previous studies using broadband transients (~1–2 ms; cf. Benichoux et al. 2018).

Fig. 5.

A: auditory brain stem response (ABR) for an 8,000-Hz Gabor click across 3 interaural time differences (ITDs) for a single animal (S6). Blue traces are the ABR for monaural presentation to the left ear (L); red traces are the ABR for monaural presentation to the right ear (R); magenta traces are the binaural ABR (B); dashed red and blue traces are the sum of left and right ABRs (L+R); black traces are the BIC. B: BIC amplitude across 9 ITDs as computed via cross-correlation (x-corr.) and normalized to the value obtained at 0 µs for 2 animals (S5 and S6; thin lines); the mean is given by the thick line.

Next, the same set of ITD measurements was completed for two frequency-mismatch conditions. As described above, frequency-mismatched envelopes aligned at their peaks are asynchronous on their flanks. Varying ITD for a static frequency mismatch enabled us to quantify BIC when envelope segments other than the maxima were aligned (e.g., the rising edges of the envelopes where the envelope slope maxima occurred, expected to be particularly salient for ITD coding; Greenberg et al. 2017; cf. Dietz et al. 2013). BIC amplitudes across ITD for two different mismatches (±0.5 octave) are given in Fig. 6. For the −0.5-octave case, wherein the right ear was lower in frequency, the envelope slope maxima aligned at a left-leading ITD (−172 µs; Fig. 6A). Correspondingly, a subtle bias appeared in the cross-ITD BIC amplitudes, with slightly higher amplitudes for left-favoring than right-favoring ITDs. However, for both animals, the highest amplitude still occurred at 0 µs, i.e., with envelope peak alignment. The reverse trend was observed for the +0.5-octave case, where the envelope slope maxima were aligned at a slight right-favoring ITD (+119 µs; Fig. 6B), and one animal showed higher amplitude BIC at a right-favoring ITD (+250 µs) than at 0 µs.

Fig. 6.

A, top: Gabor click waveform (black) and envelope (gray) for the −1/2-octave frequency-mismatch condition (L, left ear, 4,000 Hz; R, right ear, 2,828 Hz). Whereas envelope peaks are temporally aligned with a nominal interaural time difference (ITD) of 0 µs, the envelope flanks are temporally misaligned. Here the envelope slope (red traces) reaches a maximum 172 µs earlier in the right (lower frequency) channel (R′) than in the left channel (L′). Bottom: the binaural interaction component (BIC) as measured via peak cross-correlation (x-corr.; as in Fig. 5B) for 2 animals (S5 and S6; thin lines) reached a maximum at a nominal ITD of 0 µs, although amplitudes were skewed to negative (left-leading) ITD values that produced greater alignment of the rising envelope slopes (vertical dashed line demarcates maximum slope alignment at −172 µs; thick line indicates mean BIC). B: same as in A, but for the +1/2-octave frequency-mismatch condition, where the left ear (lower frequency) slope maximum preceded the right. Correspondingly, BIC amplitudes were skewed to the right, with the trace for 1 animal peaking at a nonzero (right leading) ITD.

Notably, cochlear delay/response latency across frequency (e.g., Fig. 2) could also bias the timing of “maximal” effective temporal alignment, and the direction of influence would oppose that of the time-of-maximum-slope difference, with greater alignment occurring for ITDs favoring the lower frequency ear. The foregoing data, with amplitudes slightly biased toward ITDs favoring the higher frequency ear, suggest that cochlear delay was a not a dominant influence for the modest frequency disparities and suprathreshold sound level (65 dB SPL) evaluated. Collectively, data demonstrate that ITD modulated the Gabor-elicited BIC and suggest that frequency mismatch and ITD interacted to only a limited extent. BIC amplitudes measured at mismatched frequencies were at their largest, or nearly so, at 0-µs nominal ITD; variation in BIC amplitude with frequency mismatch can thus be chiefly attributed to frequency variation per se.

Simulation of the BIC with established phenomenological models of the AN and LSO.

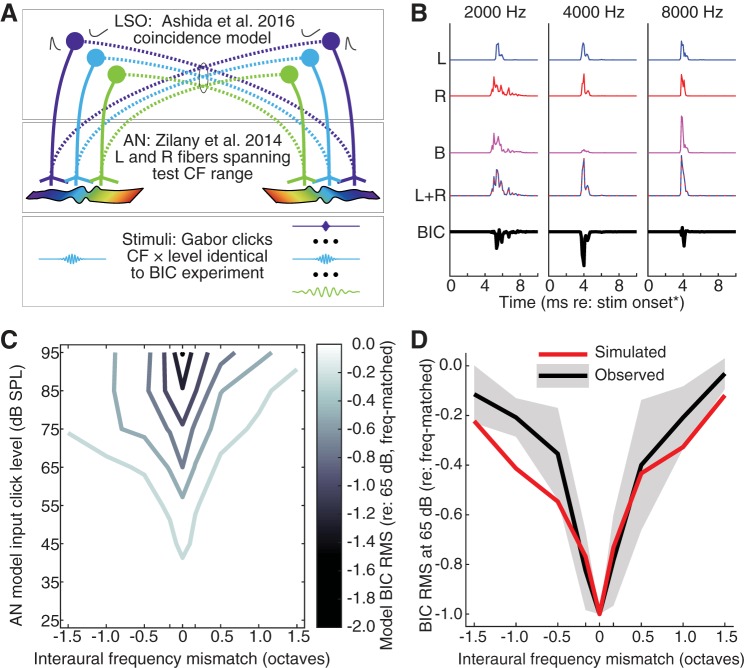

Recent evidence suggests that the BIC arises from the LSO, the initial site of binaural excitatory-inhibitory interaction in the brain stem (see introduction). Thus we next investigated whether the BIC modulation by frequency mismatch was consistent with that expected for an LSO-like circuit receiving tonotopically matched excitatory and inhibitory binaural inputs. Toward this objective, it was first necessary to simulate inputs to the LSO that reflected the spectrotemporal response characteristics expected for Gabor clicks of varying frequency and intensity. This was achieved by passing Gabor clicks of the same frequencies and intensities tested empirically through a “two-eared” phenomenological model of the AN (Zilany et al. 2009, 2014; see methods). Outputs from each simulated ear then served as excitatory or inhibitory inputs to a coincidence-counting model of the LSO (Ashida et al. 2016). The model construction is schematized in Fig. 7A (see methods and Table 1 for additional details). Figure 7B illustrates an initial simulation of LSO responses at 65 dB SPL using default parameters of the Ashida et al. (2016) model. Responses were generated using populations of low-threshold, high-spontaneous-rate AN fibers (the most numerous fiber type in the AN, though a coarse proxy for inputs to LSO; see below) with 20 excitatory and 8 inhibitory CF-matched inputs to each model LSO neuron in each of 11 frequency channels (the simulation was repeated 200 times; see methods). Responses are shown for on-frequency and ±1-octave mismatch stimulus conditions; the “BIC” is computed in the same manner as for ABR data (binaural minus monaural sum). The simulated response map across stimulus-frequency mismatch and intensity is illustrated in Fig. 7C. As for the map shown in Fig. 4B, responses are normalized to the response at 65 dB SPL in the frequency-matched condition. Figure 7D shows the simulated BIC amplitude at 65 dB normalized to the on-frequency amplitude at 65 dB; the empirically measured curve and standard deviation (from Fig. 4C) is shown for comparison.

Fig. 7.

A: schematic illustration of simulation procedure. From bottom to top: Gabor click stimuli (fixed at 4,000 Hz in left ear, varied over a 3-octave range in right ear) were presented to “left ear” and “right ear” populations of model auditory nerve (AN) fibers (Zilany et al. 2009, 2014; Table 1), which were relayed as excitatory ipsilateral projections (solid lines) and contralateral inhibitory projections (dashed lines) to simulated lateral superior olive (LSO) neurons (Ashida et al. 2016). In practice, monaural stimulation and binaural interaction were simulated within 11 parallel channels spanning the range of frequencies tested empirically (see methods). B: simulated LSO responses and resultant binaural interaction, derived as for empirical auditory brain stem response measurement, at a 65-dB SPL stimulus intensity. Blue traces are monaural presentation to the left ear (L); red traces are monaural presentation to the right ear (R); magenta traces are binaural presentation (B); dashed red and blue traces are the sum of left and right (L+R); black traces are the binaural interaction component (BIC). Vertical scale is arbitrary. C: response map across frequency mismatch and Gabor click intensity; as in Fig. 4B, values are normalized to the frequency-matched condition at 65 dB SPL. Contour interval = 0.25. D: normalized BIC amplitude via simulated responses (red line) vs. empirical measurements (black line and shading; from Fig. 4C) at 65 dB SPL. CF, characteristic frequency; RMS, root mean square.

The simulated response map shares some similarities with the empirically measured map (simulated map in Fig. 7C vs. weighted-average map in Fig. 4B including all stimulus levels, R2 = 0.71) but exhibits relatively sharp tuning at low stimulus intensities (e.g., 35 dB SPL) for which it was generally more difficult to discern an empirical BIC. This difference can be attributed to reduced influence of background noise in the simulated data, which enabled detection of small-amplitude but very sharply tuned responses [e.g., at 35 dB SPL in the frequency-matched condition (best case), the mean empirical SNR was 6.3 dB, whereas the model SNR was infinite because there was no prestimulus background noise]. At moderate intensities for which the BIC was large enough for reliable detection, simulated BIC amplitude closely followed empirically observed amplitudes (e.g., yielding an R2 value of 0.95 at the 65-dB SPL level; Fig. 7D, predicted re: observed mean). However, the predicted and empirical responses diverged somewhat for lower frequency mismatches, with less relative decrease in BIC amplitude predicted than observed empirically (divergence of curves at “negative” mismatches in Fig. 7D).

Several features of the foregoing simulation as constructed depart from physiological features of the LSO circuit of interest (see also discussion). We next evaluated the effects of adjusting several model parameters expected to influence the simulated BIC. For example, the use of a homogenous population of low-threshold, high-spontaneous-rate inputs (“type 1” fibers in the AN model), which readily respond to off-frequency stimuli of moderate amplitude and saturate with higher intensity stimulation, does not recapitulate the more moderate spontaneous activity of inputs to LSO (e.g., Joris et al. 1994; Joris and Yin 1998). The number of excitatory vs. inhibitory inputs to individual LSO neurons is another likely influential parameter to consider, with varied values suggested in the literature (Ashida et al. 2016; Gjoni et al. 2018; Sanes 1990). Additionally, homogenous populations of excitatory and inhibitory inputs in each frequency band that are tuned to exactly the same CF are not representative of the modest variability in input CFs evident in empirical LSO recordings (Sanes and Rubel 1988; see Fig. 8A). Finally, the effective excitatory-inhibitory integration time within LSO neurons, controlled by the effective durations of excitatory and inhibitory postsynaptic inputs, may be shorter (Franken et al. 2018) than the values implemented by default in the Ashida et al. (2016) model. Simulations were next repeated with systematic adjustment of these several parameters.

Fig. 8.

A: measurements of the intrinsic matching of the inputs to lateral superior olive (LSO; in gerbil, replotted from data in Sanes and Rubel 1988) demonstrate that inputs are closely, but not exactly, matched in characteristic frequency (CF). The distribution of excitatory (Exc)-inhibitory (Inh) disparity across 85 neurons (fit with a Gaussian) yields a half-width of 0.42 octave. B: binaural interaction component (BIC) simulations (see Fig. 7 and text) were repeated with variation of Exc and Inh input number (columns) using 3 different distributions of spontaneous rate inputs (rows; L, low; M, medium; H, high). For each input number-by-type distribution, simulations were completed using Exc and Inh integration windows in the model neurons of 0.8 and 1.6 ms, respectively (red curves; Ashida et al. 2016) and “short” windows of 0.4 and 0.8 ms, respectively (blue curves; see text). All simulations were completed using exact matching of Exc and Inh input CFs (solid curves) and variable mismatching within an ~0.4-octave window (E/I CF var.; dashed curves). FWHM, full width at half maximum; integ., integration; oct., octave.

Figure 8B summarizes model outputs obtained at 65 dB SPL across all parameter variations, including excitatory input number (columns), spontaneous rate input distribution (rows), default vs. short integration time (color traces), and identical vs. varied excitatory and inhibitory input CFs (randomly varied using ~0.4-octave rectangular distribution; solid and dashed lines). Generally, the best fits to observed data were obtained with 20 excitatory and 8 inhibitory inputs (Fig. 8B, middle column). For the default integration window duration, all simulations with 20 excitatory and 8 inhibitory inputs yielded R2 values of 0.92 or greater (65-dB data). Shorter integration window duration generally yielded lower R2 values, although the poorest fit (short window, 100% medium-spontaneous-rate inputs, 0 input CF variation) still yielded an R2 value of 0.78 (Fig. 8B, center panel). Simulations using 10 excitatory and 8 inhibitory inputs (Fig. 8B, left column) were generally poor, yielding predictions outside the observed range regardless of variation in other parameters. In this configuration, inhibition appeared to overwhelm excitation across stimulus frequency mismatch, yielding relatively large BIC (re: matched frequency) even with large frequency mismatches. Simulations using 40 excitatory and 8 inhibitory inputs (Fig. 8B, right column) also yielded generally poorer fits, with a notable exception in the simulation that also implemented 100% medium-spontaneous-rate fibers. In this case, the simulation that implemented 40 excitatory and 8 inhibitory inputs with the “short” window duration yielded R2 values between 0.95 and 0.96 for both “matched” and “varied” CFs.

Comparing the full set of simulated responses against empirically measured values across all stimulus frequency-by-level combinations (e.g., simulated map in Fig. 7C vs. weighted-average map in Fig. 4B) generally reinforced the foregoing trends, but R2 values were lower overall, reflecting divergence of simulated and observed values (e.g., at low intensities, as described above). The best fit across the full set of tested values was obtained with 20 excitatory and 8 inhibitory medium-spontaneous-rate inputs, default temporal integration window length (Ashida et al. 2016), and random variation of excitatory and inhibitory CF (R2 = 0.85). Parameter optimization, for example, of excitatory/inhibitory input number and spontaneous rate or of internal parameters such as the number of “coincident” excitatory inputs required to reach spiking threshold, would be expected to yield still better fits. Further consideration of such parameters, or of other response types that could contribute to measured binaural potentials (e.g., EE; see Ungan et al. 1997), was beyond the present scope. Rather, our simulation results simply convey that excitatory-inhibitory interaction broadly consistent with that observed in the LSO is modulated by interaural frequency mismatch in a manner consistent with that observed in the BIC of the ABR.

DISCUSSION

Binaural hearing provides distinct perceptual advantages over hearing with one ear alone (reviewed in Blauert 1997), and is integral to normal auditory function. Binaural dysfunction can lead to deficits in binaural hearing tasks including speech perception in noisy environments and sound localization (Moore 2007). In humans, clinical detection and treatment of binaural dysfunction poses a major challenge, because binaural hearing assessments are time-consuming and can be impractical or impossible in some populations (e.g., patients that are young, elderly, or present with comorbid impairments; cf. Chermak et al. 1999; Gates et al. 2003; Nozza et al. 1988). Moreover, once hearing loss is detected and treated with hearing aids or cochlear implants, adjusting device outputs to optimize binaural hearing outcomes is subject to similar challenges (e.g., Ching et al. 2007). A reliable biomarker of binaural hearing function could significantly improve detection and treatment of hearing loss and associated difficulties.

The observation that the binaural ABR is not a linear sum of the monaural ABRs, and that this nonlinearity might be used to index binaural function, was first reported 40 years ago (Dobie and Berlin 1979). Since that time, the BIC has been used to study binaural function in a wide variety of mammalian species (see Laumen et al. 2016). Although the BIC has shown some promise as an objective marker of binaural function in humans (Furst et al. 1990; Gunnarson and Finitzo 1991; Riedel and Kollmeier 2006), the SNR of the acoustically elicited human BIC is notoriously poor, even with several thousand stimulus repetitions. Although this fact has thus far precluded use of the BIC as a clinical tool (Laumen et al. 2016; cf. Haywood et al. 2015), further basic study stands to elucidate the BIC’s physiological origin and may point to improved measurement protocols. Recent endeavors to use the electrically evoked BIC as an objective measure for the fitting of bilateral cochlear implants have also motivated new efforts to understand its basis.

Modulation of BIC with frequency mismatch consistent with LSO source.

Our measurements indicated that the BIC was quite sensitive to interaural frequency matching (i.e., cochlear place-of-stimulation matching) at low to moderate intensities, yielding a tuning function with a half-width of 0.8 octave at a moderate intensity of 65 dB SPL (at a center frequency of 4,000 Hz). Such tuning was degraded at higher intensities; at 85–95 dB SPL, a BIC was elicited with severely mismatched inputs (click frequencies ≥1.5 octaves apart).

The hypothesized source of the BIC is the LSO (Benichoux et al. 2018; Ungan et al. 1997; see introduction). Inputs to the LSO exhibit primary-like frequency response areas, i.e., “V-shaped” tuning curves (e.g., Boudreau and Tsuchitani 1968). Thus, intuitively, given frequency-mismatched inputs, the effectiveness of “off-frequency” inhibition should be minimal at low to moderate intensities, yielding a small- or zero-amplitude BIC, whereas increasing stimulus intensity should increase the overlap of nominally mismatched inputs to yield more effective off-frequency inhibition and a larger BIC. This pattern was borne out in the simulated responses of an LSO-like circuit with physiologically constrained parameters. A balance of 20 excitatory and 8 inhibitory inputs, as suggested by Ashida et al. (2016, 2017; cf. Gjoni et al. 2018; Sanes 1990), yielded consistently good fits to empirical data; fewer (10) or additional (40) excitatory inputs generally yielded poorer fits. Simulation results were relatively robust to variation of other parameters, including excitatory and inhibitory integration time and input spontaneous rates. Importantly, predicted responses continued to follow empirically observed responses after incorporation of modest variation of excitatory vs. inhibitory input CFs, as observed physiologically in the LSO (Sanes and Rubel 1988).

Empirical measurements also demonstrated variation of BIC amplitude with ITD, reproducing the canonical 1- to 2-ms ITD tuning width of the BIC evident across many species, including those lacking a medial superior olive (Benichoux et al. 2018). BIC-vs.-ITD variation elicited by Gabor clicks in the present study was also similar to that reported for transients in chinchilla (Benichoux et al. 2018; Ferber et al. 2016). Taken together, existing evidence strongly implicates the LSO as the dominant source of the BIC.

Use of the BIC as a biomarker of binaural interaction in bilateral cochlear implant fitting.

Despite aforementioned challenges in implementing the acoustically elicited BIC as a diagnostic tool, the electrically elicited BIC has generated considerable interest as a treatment tool for the fitting of cochlear implants (Gordon et al. 2012; Hancock et al. 2010; He et al. 2010, 2012; Hu et al. 2016; Hu and Dietz 2015; Pelizzone et al. 1990; Smith and Delgutte 2007). Binaural hearing via bilateral cochlear implants requires that the separate electrical signals delivered to the two ears stimulate an overlapping binaural neural population. Asymmetries in surgical placement of the two electrode arrays and in the status of surviving AN fiber populations across the two ears are common, requiring post hoc electrode “pairing” procedures to improve binaural overlap. The standard pairing procedure, subjective “pitch-matching” of electrodes between the two ears, suffers from poor reliability and does not assay binaural function (Hu and Dietz 2015). The electrically elicited BIC offers an objective pairing metric that may outperform such pitch-matching procedures (Hu and Dietz 2015). However, the broad electrode-vs.-BIC tuning functions reported thus far (Gordon et al. 2012; He et al. 2010, 2012; Hu and Dietz 2015) limit the precision with which electrodes can be paired, and thus the precision with which binaural neurons may be stimulated, ultimately limiting binaural perceptual gains.

Our findings strongly suggest that the sharpest BIC-based interaural electrode pairing functions should be obtained at modest stimulation levels with focused (place limited) stimulation (e.g., He et al. 2010). Even nominal one-third-octave band acoustic stimuli led to cross-frequency saturation of BIC amplitudes (in an animal model audiometrically similar to humans) at intensities of 85–95 dB SPL that caused spread of excitation within the cochleae (and thus significant binaural overlap despite nominally disparate stimulus frequencies).

Previous cochlear implant BIC studies in humans (Gordon et al. 2012; He et al. 2010, 2012; Hu et al. 2016; Hu and Dietz 2015) have employed monopolar stimulation, in which the return electrode is located outside the cochlea. Monopolar stimulation yields broad spread of electrical stimulation with intrinsically poor spatial resolution (e.g., Kral et al. 1998). In an animal study (cat), Smith and Delgutte (2007) explicitly compared electrically evoked BIC tuning functions measured via monopolar stimulation vs. bipolar stimulation, in which the return electrode was adjacent to the stimulating electrode. Although bipolar stimulation is expected to be somewhat more spatially focused than monopolar (e.g., Kral et al. 1998; Sato et al. 2016), Smith and Delgutte (2007) reported similar BIC tuning functions for the two cases. However, comparison of auditory midbrain responses to monopolar and bipolar stimulation suggests that both yield relatively broad tuning. Tripolar stimulation, in which the electrodes to either side of the stimulating electrode are used as return electrodes, appears to elicit sharper tuning at the level of the midbrain (Snyder et al. 2004, Fig. 13; cf. Kral et al. 1998). This observation suggests that leveraging tripolar stimulation in future cochlear implant BIC protocols may be an effective means to more precisely identify physiologically matched electrodes. Further suggesting a need to control stimulation bandwidth, a previous psychoacoustic simulation of bilateral CI stimulation with mismatched electrodes demonstrated that increasing effective stimulus bandwidth (from 1.5 to 3.0 mm) led to reduced modulation of ITD sensitivity with frequency mismatch, and thus reduced differentiation of binaurally frequency-matched and mismatched conditions (Kan et al. 2013).

Electrically vs. acoustically elicited BIC in human subjects.

It is unclear why, in humans, the electrically elicited BIC appears to be more readily measured than acoustic BIC. One explanation is that brief electrical pulses delivered by implanted electrode arrays yield high neural synchrony, whereas broadband acoustic pulses become temporally dispersed in the cochleae, leading to reduced coherence and weaker summed potentials downstream. Evidence presented and discussed throughout this report implicates the LSO as the dominant generator of the BIC (see Benichoux et al. 2018). The human LSO (Moore 2000) is deep in the brain stem (pons) and distant from electrode contacts used in standard ABR recording montages. Increased neural synchrony realized via electrical stimulation could help to elevate a small-amplitude signal above intervening noise sources. In support of this possibility, Riedel and Kollmeier (2002) reported that larger amplitude BICs were elicited via chirp stimuli (tone sweep rapidly increasing from low to high frequency) that were explicitly designed to offset cochlear delay to produce maximally synchronous stimulation (Dau et al. 2000). Prospects for electrically elicited BIC aside, an approach that combined synchrony-optimizing stimuli with an electrode montage optimized to record from the pons/superior olivary complex, might hold promise for more reliable measurement of acoustic BIC in human patients. The advent of other electrophysiological signatures of binaural hearing (e.g., the interaural phase modulation following response; Haywood et al. 2015), which is also modulated by interaural frequency disparity (McAlpine et al. 2016), may provide another promising path forward.

Limitations of the present study.

The present study used an animal model audiometrically similar to humans, the chinchilla, to enable BIC measurement across an extensive battery of stimulus conditions. Future studies could employ a reduced set of stimulus conditions informed by the present measurements (e.g., ±1 octave at 65 dB SPL) to measure useful BIC tuning functions in human subjects. The AN model that was employed (Zilany et al. 2009, 2014) used auditory filter widths from the cat. Although the mapping of frequency to cochlear place differs considerably across species, the frequency tuning of cat and chinchilla AN fibers is similar (Verschooten et al. 2018). Likewise, whereas binaural interaction in the LSO ultimately arises via inputs from the cochlear nucleus and medial nucleus of the trapezoid body, frequency tuning at these stages does not appear to differ fundamentally from that observed in the AN (Koka and Tollin 2014). The particular LSO model employed (Ashida et al. 2016) uses parameters informed by data from a variety of species. We endeavored to vary default parameters across a range of values. In the future it may be informative to further evaluate effects of variation in excitatory vs, inhibitory input number, which may vary across species (cf. Gjoni et al. 2018; Sanes and Rubel 1988). Of parameters we evaluated, excitatory input number exerted the strongest influence on simulated BIC tuning.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute for Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Grants F32-DC013927 (to A. D. Brown), R21-DC017213-01 (to A. D. Brown), R01-DC011555 (to D. J. Tollin), and F31-DC014219 (to K. L. Anbuhl), National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant T32-HD041697 and the University of Colorado School of Medicine Neuroscience Training Program (to J. I. Gilmer), and the University of Washington (to A. D. Brown).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.D.B., K.L.A., and D.J.T. conceived and designed research; A.D.B., K.L.A., and J.I.G. performed experiments; A.D.B. and D.J.T. analyzed data; A.D.B., K.L.A., J.I.G., and D.J.T. interpreted results of experiments; A.D.B. and D.J.T. prepared figures; A.D.B. and D.J.T. drafted manuscript; A.D.B., K.L.A., J.I.G., and D.J.T. edited and revised manuscript; A.D.B., K.L.A., J.I.G., and D.J.T. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Victor Benichoux for helpful comments on a previous version of this manuscript and Dr. Alex Ferber and Jamie Costabile for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- American National Standards Institute ANSI S1.11-2004: American National Standard. Specification for Octave-Band and Fractional-Octave-Band Analog and Digital Filters. New York: American National Standards Institute, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ashida G, Kretzberg J, Tollin DJ. Roles for coincidence detection in coding amplitude-modulated sounds. PLoS Comput Biol 12: e1004997, 2016. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashida G, Tollin DJ, Kretzberg J. Physiological models of the lateral superior olive. PLoS Comput Biol 13: e1005903, 2017. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benichoux V, Ferber A, Hunt S, Hughes E, Tollin D. Across species “natural ablation” reveals the brainstem source of a noninvasive biomarker of binaural hearing. J Neurosci 38: 8563–8573, 2018. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1211-18.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutelmann R, Laumen G, Tollin D, Klump GM. Amplitude and phase equalization of stimuli for click evoked auditory brainstem responses. J Acoust Soc Am 137: EL71–EL77, 2015. doi: 10.1121/1.4903921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blauert J. Spatial Hearing: The Psychophysics of Human Sound Localization. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Boudreau JC, Tsuchitani C. Binaural interaction in the cat superior olive S segment. J Neurophysiol 31: 442–454, 1968. doi: 10.1152/jn.1968.31.3.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AD, Tollin DJ. Slow temporal integration enables robust neural coding and perception of a cue to sound source location. J Neurosci 36: 9908–9921, 2016. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1421-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chermak GD, Hall JW 3rd, Musiek FE. Differential diagnosis and management of central auditory processing disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Audiol 10: 289–303, 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ching TY, van Wanrooy E, Dillon H. Binaural-bimodal fitting or bilateral implantation for managing severe to profound deafness: a review. Trends Amplif 11: 161–192, 2007. doi: 10.1177/1084713807304357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dau T, Wegner O, Mellert V, Kollmeier B. Auditory brainstem responses with optimized chirp signals compensating basilar-membrane dispersion. J Acoust Soc Am 107: 1530–1540, 2000. doi: 10.1121/1.428438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz M, Marquardt T, Salminen NH, McAlpine D. Emphasis of spatial cues in the temporal fine structure during the rising segments of amplitude-modulated sounds. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 15151–15156, 2013. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1309712110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobie RA, Berlin CI. Binaural interaction in brainstem-evoked responses. Arch Otolaryngol 105: 391–398, 1979. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1979.00790190017004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elberling C, Kristensen SG, Don M. Auditory brainstem responses to chirps delivered by different insert earphones. J Acoust Soc Am 131: 2091–2100, 2012. doi: 10.1121/1.3677257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldredge DH, Miller JD, Bohne BA. A frequency-position map for the chinchilla cochlea. J Acoust Soc Am 69: 1091–1095, 1981. doi: 10.1121/1.385688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferber AT, Benichoux V, Tollin DJ. Test-retest reliability of the binaural interaction component of the auditory brainstem response. Ear Hear 37: e291–e301, 2016. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franken TP, Joris PX, Smith PH. Principal cells of the brainstem’s interaural sound level detector are temporal differentiators rather than integrators. eLife 7: e33854, 2018. doi: 10.7554/eLife.33854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furst M, Eyal S, Korczyn AD. Prediction of binaural click lateralization by brainstem auditory evoked potentials. Hear Res 49: 347–359, 1990. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(90)90113-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates GA, Murphy M, Rees TS, Fraher A. Screening for handicapping hearing loss in the elderly. J Fam Pract 52: 56–62, 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gjoni E, Zenke F, Bouhours B, Schneggenburger R. Specific synaptic input strengths determine the computational properties of excitation-inhibition integration in a sound localization circuit. J Physiol 596: 4945–4967, 2018. doi: 10.1113/JP276012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon KA, Salloum C, Toor GS, van Hoesel R, Papsin BC. Binaural interactions develop in the auditory brainstem of children who are deaf: effects of place and level of bilateral electrical stimulation. J Neurosci 32: 4212–4223, 2012. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5741-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorga MP, Kaminski JR, Beauchaine KA, Jesteadt W. Auditory brainstem responses to tone bursts in normally hearing subjects. J Speech Hear Res 31: 87–97, 1988. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3101.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg D, Monaghan, Dietz M, Marquardt T, McAlpine D. Influence of envelope waveform on ITD sensitivity of neurons in the auditory midbrain. J Neurophysiol 118: 2358–2370, 2017. doi: 10.1152/jn.01048.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood DD. A cochlear frequency-position function for several species–29 years later. J Acoust Soc Am 87: 2592–2605, 1990. doi: 10.1121/1.399052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnarson AD, Finitzo T. Conductive hearing loss during infancy: effects on later auditory brain stem electrophysiology. J Speech Hear Res 34: 1207–1215, 1991. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3405.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock KE, Noel V, Ryugo DK, Delgutte B. Neural coding of interaural time differences with bilateral cochlear implants: effects of congenital deafness. J Neurosci 30: 14068–14079, 2010. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3213-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haywood NR, Undurraga JA, Marquardt T, McAlpine D. A comparison of two objective measures of binaural processing: the interaural phase modulation following response and the binaural interaction component. Trends Hear 19: 2331216515619039, 2015. doi: 10.1177/2331216515619039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He S, Brown CJ, Abbas PJ. Effects of stimulation level and electrode pairing on the binaural interaction component of the electrically evoked auditory brain stem response. Ear Hear 31: 457–470, 2010. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e3181d5d9bf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He S, Brown CJ, Abbas PJ. Preliminary results of the relationship between the binaural interaction component of the electrically evoked auditory brainstem response and interaural pitch comparisons in bilateral cochlear implant recipients. Ear Hear 33: 57–68, 2012. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31822519ef. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H, Dietz M. Comparison of interaural electrode pairing methods for bilateral cochlear implants. Trends Hear 19: 2331216515617143, 2015. doi: 10.1177/2331216515617143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H, Kollmeier B, Dietz M. Suitability of the binaural interaction component for interaural electrode pairing of bilateral cochlear implants. Adv Med Exp Biol 894: 57–64, 2016. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-25474-6_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewett DL, Romano MN, Williston JS. Human auditory evoked potentials: possible brain stem components detected on the scalp. Science 167: 1517–1518, 1970. doi: 10.1126/science.167.3924.1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joris PX, Carney LH, Smith PH, Yin TC. Enhancement of neural synchronization in the anteroventral cochlear nucleus. I. Responses to tones at the characteristic frequency. J Neurophysiol 71: 1022–1036, 1994. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.3.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joris PX, Yin TC. Envelope coding in the lateral superior olive. III. Comparison with afferent pathways. J Neurophysiol 79: 253–269, 1998. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.1.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kan A, Stoelb C, Litovsky RY, Goupell MJ. Effect of mismatched place-of-stimulation on binaural fusion and lateralization in bilateral cochlear-implant users. J Acoust Soc Am 134: 2923–2936, 2013. doi: 10.1121/1.4820889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koka K, Tollin DJ. Linear coding of complex sound spectra by discharge rate in neurons of the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body (MNTB) and its inputs. Front Neural Circuits 8: 144, 2014. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2014.00144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kral A, Hartmann R, Mortazavi D, Klinke R. Spatial resolution of cochlear implants: the electrical field and excitation of auditory afferents. Hear Res 121: 11–28, 1998. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5955(98)00061-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laumen G, Ferber AT, Klump GM, Tollin DJ. The physiological basis and clinical use of the binaural interaction component of the auditory brainstem response. Ear Hear 37: e276–e290, 2016. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JD, Kopun J, Neely ST, Schmid KK, Gorga MP. Tone-burst auditory brainstem response wave V latencies in normal-hearing and hearing-impaired ears. J Acoust Soc Am 138: 3210–3219, 2015. doi: 10.1121/1.4935516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAlpine D, Haywood N, Undurraga J, Marquardt T. Objective measures of neural processing of interaural time differences. Adv Med Exp Biol 894: 197–205, 2016. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-25474-6_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore BC. Spatial hearing and advantages of binaural hearing. In: Cochlear Hearing Loss: Physiological, Psychological, and Technical Issues, edited by Moore BC. West Sussex, UK: Wiley, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Moore JK. Organization of the human superior olivary complex. Microsc Res Tech 51: 403–412, 2000. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nozza RJ, Wagner EF, Crandell MA. Binaural release from masking for a speech sound in infants, preschoolers, and adults. J Speech Hear Res 31: 212–218, 1988. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3102.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelizzone M, Kasper A, Montandon P. Binaural interaction in a cochlear implant patient. Hear Res 48: 287–290, 1990. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(90)90069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasetshwane DM, Argenyi M, Neely ST, Kopun JG, Gorga MP. Latency of tone-burst-evoked auditory brain stem responses and otoacoustic emissions: level, frequency, and rise-time effects. J Acoust Soc Am 133: 2803–2817, 2013. doi: 10.1121/1.4798666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedel H, Kollmeier B. Auditory brain stem responses evoked by lateralized clicks: is lateralization extracted in the human brain stem? Hear Res 163: 12–26, 2002. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5955(01)00362-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedel H, Kollmeier B. Interaural delay-dependent changes in the binaural difference potential of the human auditory brain stem response. Hear Res 218: 5–19, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2006.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruebhausen MR, Brozoski TJ, Bauer CA. A comparison of the effects of isoflurane and ketamine anesthesia on auditory brainstem response (ABR) thresholds in rats. Hear Res 287: 25–29, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanes DH. An in vitro analysis of sound localization mechanisms in the gerbil lateral superior olive. J Neurosci 10: 3494–3506, 1990. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-11-03494.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanes DH, Rubel EW. The ontogeny of inhibition and excitation in the gerbil lateral superior olive. J Neurosci 8: 682–700, 1988. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-02-00682.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato M, Baumhoff P, Kral A. Cochlear implant stimulation of a hearing ear generates separate electrophonic and electroneural responses. J Neurosci 36: 54–64, 2016. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2968-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmiedt RA. Spontaneous rates, thresholds and tuning of auditory-nerve fibers in the gerbil: comparisons to cat data. Hear Res 42: 23–35, 1989. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(89)90115-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith ZM, Delgutte B. Using evoked potentials to match interaural electrode pairs with bilateral cochlear implants. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 8: 134–151, 2007. doi: 10.1007/s10162-006-0069-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder RL, Bierer JA, Middlebrooks JC. Topographic spread of inferior colliculus activation in response to acoustic and intracochlear electric stimulation. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 5: 305–322, 2004. doi: 10.1007/s10162-004-4026-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stapells DR, Oates P. Estimation of the pure-tone audiogram by the auditory brainstem response: a review. Audiol Neurotol 2: 257–280, 1997. doi: 10.1159/000259252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tollin DJ. The lateral superior olive: a functional role in sound source localization. Neuroscientist 9: 127–143, 2003. doi: 10.1177/1073858403252228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungan P, Yağcioğlu S, Özmen B. Interaural delay-dependent changes in the binaural difference potential in cat auditory brainstem response: implications about the origin of the binaural interaction component. Hear Res 106: 66–82, 1997. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5955(97)00003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verschooten E, Desloovere C, Joris PX. High-resolution frequency tuning but not temporal coding in the human cochlea. PLoS Biol 16: e2005164, 2018. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2005164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Colburn HS. A modeling study of the responses of the lateral superior olive to ipsilateral sinusoidally amplitude-modulated tones. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 13: 249–267, 2012. [Erratum in J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 18: 729, 2017.] doi: 10.1007/s10162-011-0300-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilany MS, Bruce IC, Carney LH. Updated parameters and expanded simulation options for a model of the auditory periphery. J Acoust Soc Am 135: 283–286, 2014. doi: 10.1121/1.4837815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilany MS, Bruce IC, Nelson PC, Carney LH. A phenomenological model of the synapse between the inner hair cell and auditory nerve: long-term adaptation with power-law dynamics. J Acoust Soc Am 126: 2390–2412, 2009. doi: 10.1121/1.3238250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]