Summary

This article outlines recent developments in safety science. It describes the progression of three ‘ages’ of safety, namely the ‘age of technology’, the ‘age of human factors’ and the ‘age of safety management’. Safety science outside healthcare is moving from an approach focused on the analysis and management of error (‘Safety‐1’) to one which also aims to understand the inherent properties of safety systems that usually prevent accidents from occurring (‘Safety‐2’). A key factor in the understanding of safety within organisations relates to the distinction between ‘work as imagined’ and ‘work as done’. ‘Work as imagined’ assumes that if the correct standard procedures are followed, safety will follow as a matter of course. However, staff at the ‘sharp end’ of organisations know that to create safety in their work, variability is not only desirable but essential. This positive adaptability within systems that allows good outcomes in the presence of both favourable and adverse conditions is termed resilience. We argue that clinical and organisational work can be made safer, not only by addressing negative outcomes, but also by fostering excellence and promoting resilience. We outline conceptual and investigative approaches for achieving this that include ‘appreciative inquiry’, ‘positive deviance’ and excellence reporting.

Keywords: quality measures: patient care, root cause analysis: essential elements

Introduction

Optimising patient safety is a goal of healthcare. Much has been spoken and written about it, and it is well established as a core activity for all those working in healthcare systems. This has not always been the case; historically, error and harm from healthcare was an accepted risk of treatment. However, as standards of treatment and care have improved this acceptability was questioned and refuted, and the patient safety movement born.

This article summarises the evolution of safety science, describing historical approaches, comparing them with recent concepts in safety, and describing how they affect staff working within the healthcare system. It introduces some of the models we use to explain safety‐related work and the way we view the system as a whole, and it gives examples of tools and techniques to apply in practice. It does not aim to be a systematic review 1, but instead reflects the authors’ (at times partisan) interpretation of the research literature and reflection on clinical and organisational experience. Its purpose is to give the reader an insight into the evolution of current approaches to patient safety and an appreciation of some of their limitations. It also gives an account of some of the newer concepts and the ways they can be applied in everyday safety work.

The three ‘ages’ of safety

Hale and Hovden have traced the development of safety by describing three ‘ages’ of safety, namely ‘the age of technology’, ‘the age of human factors’ and ‘the age of safety management’ 2. In the first age, it was technology that posed the main threat to safety. This was not only because machines were inherently unreliable and dangerous, but also because people had not yet learned to identify and avoid the risks they posed. This age is generally held to have begun around the time of the industrial revolution (c. 1770), but extended well into the 20th century. Both Heinrich's seminal book on industrial safety in the early 1930s 3, and the development in the 1950s and 1960s of a number of methods of analysing risks within technological systems describe this view of safety. Accidents in the first age of safety were attributed to breakdown, failure and malfunction of machinery. The models used to describe and explain accidents have evolved in parallel with the changes in safety thinking, typified by the three ages listed above. The Domino model, proposed by Heinrich in the 1930s 3 describes a set of domino pieces that fall, each knocking down the next, exemplifying simple, sequential, linear causality. Within this paradigm, event analysis is geared towards finding the step (or component) that ‘failed’. Although simple, this model guided risk management well into the 20th century and gave rise to many sophisticated prospective analytical techniques, such as hazard and operability studies and failure modes and effects analysis. Such prospective approaches are fruitful and have also been applied to healthcare, as in a previous study that attempted to identify points in the peri‐operative pathway where safety could be enhanced 4. These were used to try to anticipate the likelihood and severity of possible points of failure or malfunction in industrial systems, so that procedures and ‘fail‐safes’ could be put into place to deal with possible hazards and prevent accidents. Although they focused on the technology rather than the humans operating it, they were applied even to complex mechanical systems such as power plants and led to considerable advances in safety at the time.

The limitations of focusing on technology as the source of accidents were illustrated by the disaster at the Three Mile Island nuclear plant in the US in 1979. During the preceding 20–30 years, there had been some attempts at scientific study of the interplay between humans and technology, but these had focused on efficiency and productivity rather than safety. In comparison with technology, humans ‘came to be seen as too imprecise, variable and slow’ 5. The Three Mile Island incident evolved from a minor mistake made during routine maintenance; the operators in the plant control room interpreted conflicting instrument readings in a way that allowed them to apply standard operating procedures in an attempt to correct the problem. However, this interpretation was incorrect and made the situation worse. Only when (some hours later) a new technician was called in to the control room was the situation correctly re‐interpreted and a much more serious outcome averted. This incident struck a blow to the notion (supported implicitly by the domino model of accident explanation) that all possibilities of failure could be predicted or managed by predictable means. Furthermore, it also became generally accepted within the safety science community that it was no longer possible to ignore the role of people in complex systems. To promote human reliability, the aim became to reduce the human contribution in the processes of care to a minimum by standardising and improving basic processes, and automating work as much as possible 6.

However, there are some problems with this approach, especially as applied to healthcare. Many things cannot, or should not, be standardised (see below). Automation is helpful in some aspects of care, but unnecessary or undesirable in others. Logically, human reliability is inevitably accompanied by the potential for unreliability. Although technology can be thought of as morally neutral (it is a nonsense to suppose, for instance, that a machine might deliberately malfunction), humans carry the power of agency, meaning that intention can be ascribed to their actions and with it the possibility of blame. Thus, the idea that humans (as well as machines) should play a part in systems of safety not only introduced the concept of human reliability (to complement mechanical reliability) but also promoted identification of human error as a key part of accident analysis. The enduring legacy of the second age of safety is thus the possibility of castigation, victimisation and admonishment of humans as they are blamed for their ‘mistakes’.

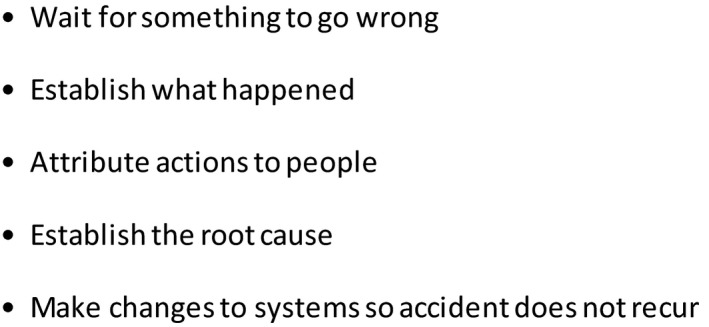

This new view of safety needed a better explanatory model, and the 1980s saw the publication of Reason's ‘Swiss cheese’ model 7. This represents events in terms of composite linear causality, where adverse events can be attributed to combinations of active failures (unsafe acts) and latent conditions (hazards). The types of conditions influencing safety include team and organisational factors, as well as individual personality and behaviour. The model is still inherently linear; investigation of accidents still assumes that it is possible to work backwards and identify causative features. Using this model, a substantial amount of effort has been devoted to examining the sequence of events leading up to accidents to try to understand how the accident came about and thus help to prevent recurrence. This approach was adopted in aviation and subsequently in healthcare, in the NHS and especially in anaesthesia 8, 9, 10. A typical approach is depicted in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

A typical approach to accident investigation.

However, within 10 years or so (towards the end of the 1980s) it became clear that although the inclusion of human elements was necessary, it was not in itself sufficient to give form to a model that could explain accidents in complex organisational systems. The resulting attention given to broader safety management systems led to the name given to this ‘third age’. A move away from the probabilistic assessment of possible risks, and the linear backward search for contributing or causal factors in accidents, was accompanied by a trend towards understanding organisational culture and processes in addition to technology and human behaviour. The relationships between individual human beings, the technology they use, and the organisational setting they work within, together make up complex sociotechnical systems.

The transitions between the first and second, and especially between the second and third, ages have not been clear cut. As Hollnagel noted in 2014, ‘the practices of risk assessment and safety management still find themselves in the transition from the second to the third age’ 5 and indeed elements of all three ages may co‐exist. We should also note here that the three ages of safety (having first been described in 2001) are retrospective constructs that aim to make sense of (and possibly over‐simplify) history. Nevertheless, we believe they offer a useful perspective. A summary can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1.

The ages of safety and associated models

| ‘Age’ | Model | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | The age of technology | Domino model |

| 2 | The age of human factors | Swiss cheese model |

| 3 | The age of safety management | Safety‐1 and Safety‐2 |

From Safety‐1 to Safety‐2 and two views of work

The focus in the third age of safety is more on trying to understand and strengthen everyday features of work within complex sociotechnological systems that promote safety. This is the dominant paradigm in what Hollnagel has termed ‘Safety‐2’ in comparison with ‘Safety‐1’, where the focus is essentially on errors and how they have arisen 5. The system property promoting the maintenance of safety has been termed resilience, and is well defined by Hollnagel as ‘the ability to succeed under expected and unexpected conditions alike, so that the number of intended and acceptable outcomes is a high as possible’ (p. 134) 5.

Hollnagel went on to articulate the concepts of ‘work as imagined’ and ‘work as done’ as two contrasting ways of understanding work 5. ‘Work as imagined’ is defined by the rules and standards outlining the way things should work and represents how designers, managers, regulators and authorities believe work happens or should happen. ‘Work as done’, on the other hand, describes the work as carried out by ‘front‐line’ employees at the ‘sharp end’; in the case of healthcare, clinicians who interact with patients. Those who work at this level know that although protocols and guidelines have their place, work is only possible by continually adjusting what you do, which sometimes means improvising and working outside the ‘rules’. This variability in performance is necessary, partly due to not only the inherent unpredictability of much of the work in healthcare but also sometimes due to the very organisational conditions created by those at the ‘blunt end’; the policies they have produced, or the way in which they view work. We suggest that the ‘work as done’/‘work as imagined’ model helps to explain why there are contrasting (and sometimes conflicting) views about how safety should be managed in healthcare organisations.

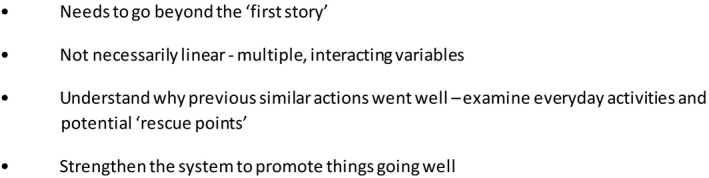

Taking a work‐based view of accidents, each step of the investigation model in Fig. 1 can now be seen to be at best limited in its usefulness, and at worst fundamentally flawed. Waiting for something to go wrong risks unnecessary harm if the problems within the system can be detected before they cause an accident. Finding out what happened (typically by root cause analysis, which is now well embedded in NHS culture) often focuses on the ‘first story’; that is, establishing the ‘facts’ and the timeline linking them. This is essential, but gives an account of events that is incomplete without the meanings given to them by the people concerned, or an understanding of why they acted as they did 11. The third step, that of attributing actions to people, is the most dangerous. This can very easily stray into the allocation of blame, which is bad for safety in general; humans need to feel safe to act safely, and a punitive culture will discourage reporting of error and its balanced analysis. Furthermore, safety investigations often stop as soon as human error has been identified as a causative factor. As noted above, attributing actions to one individual is undesirable and also closes off further investigation into organisational function, norms and behaviour. The fourth element (finding the root cause) is problematic, as the ‘root’ may never actually be reached, and it is also logically asymmetrical 12; although it is possible to argue that every cause must have an effect, not every event has an identifiable antecedent, let alone one that can be considered causative (reverse causality).

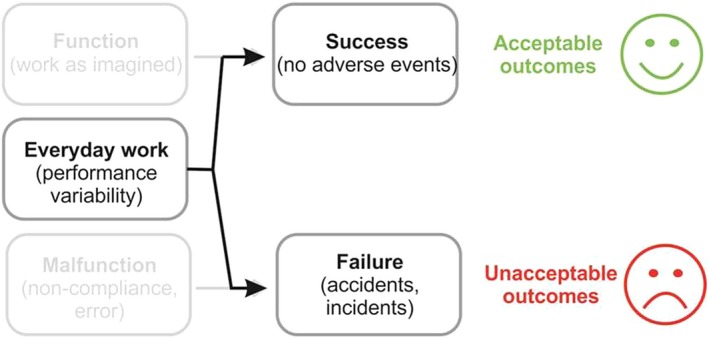

The final step, that of fixing the system (so that the accident does not happen again) ignores that fact that the system usually operates successfully to prevent the occurrence or propagation of accidents, and so in that sense it does not need fixing. At its simplest, safety becomes a matter of procedures and compliance with them. Means of repair such as recommendations and guidelines very much demonstrate a reinforcement of ‘safety as imagined’, and often do not mean much to those on the front line. Large enquiries offer many recommendations that are naively assumed to be independent, but which in practice may be contradictory. However, the strongest indictment of the ‘fixing’ approach is that it implies a binary view of work and outcome; that correctly functioning systems (and the humans within them) do not lead to adverse outcomes, which can only come about through malfunction or error 13. As we argued above, this is an oversimplification of work; responsiveness to changing needs and circumstances is essential to get the job done. This performance variability helps produce the right outcome, although sometimes it may contribute to an unacceptable outcome. This is illustrated in Fig. 2. It then becomes possible to posit a revised investigation model (Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

Relationship between performance variability and outcome. Reproduced from Safety‐1 to Safety‐2: A White Paper. EUROCONTROL 201314.

Figure 3.

Revised approach to accident investigation.

Problem areas in patient safety

Studying patient safety and applying its scientific principles to practice is complicated. Here, we deal with four factors that contribute to this.

The first is the ambivalent role of human beings in safety. On the one hand, humans bring variability and uncertainty, and hence can be thought of as increasing the risk of error. On the other (as in the Three Mile Island incident above) they also act to promote safety. Human variability is what permits us to improvise and try new responses to newly encountered situations and is therefore desirable. As Vincent notes, there are two broad approaches to this issue that fit neatly with the Safety‐1 and Safety‐2 approaches, respectively 6. One is to simplify, standardise and automate; in the other, enhanced safety comes about not through minimising the human contribution, but by understanding how people think about (and respond to) the risks in their work, overcome hazards and, in effect ‘create’ safety.

The second is related to this and deals with the advantages and disadvantages of standardisation. In a short but brilliant recent article, Wears explored the complexities behind the common and deceptively simple call for greater standardisation in healthcare 15. The benefits of standardisation are obvious in many settings and are of particular relevance to safety. Standards promote routinisation, which in turn allows the freeing‐up of ‘attentional resources, diverting them from mundane to truly complex or pressing issues' 16. Wears goes on to delineate five problematic aspects of standardisation, especially in healthcare. These include: its philosophical basis rooted in old‐fashioned production line industrial processes; its tendency to ignore existing practices, albeit without the formality and documentation usually preferred by managers (see, for instance, our previous work on recovery room handovers 17); and the fact that standardisation can be psychologically and organisationally comforting, even if it is ineffective 15. One need only refer to recently published articles within the medical literature to see that the debate as to what extent standardisation and protocolisation are effective is continuing unabated 18, 19, 20, 21. Even within industries where there are formally established safety practices such as aviation and the offshore oil industry, practical skills, support from colleagues, the creation of ‘performance spaces’ and flexibility in problem‐solving (all rooted in the informal elements of work) are important in maintaining safety 22.

The third problem area is transferability. Ideas from safety science have been applied to healthcare and have much to offer, but there are barriers to transferability. First, safety is rightly seen as only one dimension of healthcare quality 23, but as in industry, timeliness, efficiency and customer focus (‘patient‐centred care’) are also important. However, effectiveness and equity of care must also be included in healthcare quality 23. Second, although patient safety is a clinical and policy priority, the ideas and principles outlined above can be quite abstract, and it may be that this presents difficulties for healthcare staff. Perhaps for this reason, there is often a rather reductionist feel to many patient safety initiatives in healthcare. For instance, substantial resources are expended on preventing and managing healthcare‐associated infections (the UK Government have made infection rates with certain organisms one measure of the quality of care in hospitals) and the World Health Organization surgical checklist, whose use has been mandated in the UK National Health Service (NHS). However, unless the underlying principles and ideas are fully understood, there is a risk that patient safety will be interpreted superficially as a series of single issues and without appreciation of the importance of culture.

Finally, safety science may be politically neutral, but its application is not. Notions of risk and safety have come to shape private and public discourse so powerfully that they are sometimes used towards ends which, on careful examination, have little bearing on safety per se. For instance, as Fischhoff has noted, couching problems in terms of safety may lead them to be taken more seriously within organisations, where people discover that being disgruntled does not have legal standing, but complaining about risks does 24. It has also been argued that the notion of patient safety has been used as an instrument of governmental control; Yeung and Dixon‐Woods refer to ‘discourse creep’ as issues within healthcare are redefined as safety problems to legitimise intervention and potentially limit professional autonomy 25. Thus, safety is closely related to personal/professional identity and roles. In this context, it is worth noting that despite numerous initiatives to improve patient safety, we have little idea whether they have worked. Although Vincent has argued that this is because we lack the systematic measures to evaluate possible changes, it is also possible (though speculative) that it is more important politically for care to appear to be getting safer than for this to be actually achieved 26. He and Amalberti have also more recently made the point that care envisaged by standards and guidelines differs from the care given to patients. They note that much care falls below the levels envisaged by standards and guidelines, but point out that it is politically unpalatable for organisations (let alone governments) to admit this openly. They argue that this has two consequences for the management of risk. First, ‘it becomes very difficult to study or to value the many adaptive ways in which staff cope in difficult environments to prevent harm coming to patients’. Secondly, and more importantly, ‘attempts to improve safety may not be targeting the right levels (of the organisation) or the right behaviours’ 27.

Creating safety and promoting resilience

We suggested above that the key property of safe systems as understood within the Safety‐2 paradigm is robustness in the face of error‐creating conditions – resilience. Resilience can be defined as the ‘everyday performance variability that provides the adaptations that are needed to produce good outcomes, both when conditions are favourable and when they are not’. Although this review has chosen not to focus on individual resilience, well‐being and mental health (these are well dealt with elsewhere), like many, we believe these underpin the resilience of organizations 28, 29. We would simply point out that human performance is poorer if people are tired 30, 31 hungry, stressed, sad or are the victims or even witnesses of rudeness or coercion 32, 33. Mental state also influences how people deal with the consequences of error. They need to feel safe to be safe 5, but we would argue that anaesthetists also need to feel safe to act safely; working within a system where individuals are punished for ‘mistakes’ does not create a good working atmosphere. They also need to feel able to ask for help 34 and to raise concerns 35 without being criticised. As professionals, we need to learn to balance comfort with constant vigilance and ‘intelligent wariness’ without becoming overwatchful 36. A ‘sixth sense’ for safety 37, coupled with the conscientiousness to act on one's diagnostic hunches (whether clinical or organisational) are probably the two most important traits of the resilient professional. At whatever level we might look, the principle is the same; nurturing both individual and organisational resilience must be considered fundamental to the safe delivery of healthcare.

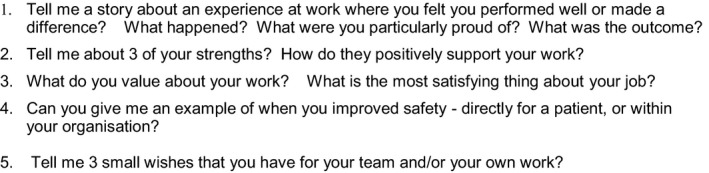

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement takes this concept one step further. In 2017, it published a White Paper describing a ‘Framework for Improving Joy in Work’ 38. This paper sets out the link between the level of staff engagement and the quality of patient care, including safety. It references the ‘burnout epidemic’ affecting healthcare, citing the link between physician burnout and medical error 39. Hypothesising that joy is the antithesis of burnout, it describes a framework of factors that facilitate joy, one of which is physical and psychological safety (Fig. 4). These factors should not be considered as optional extras to our workplace, but rather the starting point to ensure that staff can deliver safe, high‐quality care. Fostering joy in work, or even just one aspect of it – psychological safety – can be a challenge when the language we use when we talk about safety is primarily negative. We discuss critical incidents 10, error 7, never events 40, 41, 42 and colloquially the names of incident reporting systems have become verbs, for example, ‘I'm Datix‐ing that’. What is more significant is that we do not have a similar vocabulary for successful events. We have succeeded in developing our ability to describe human factors and non‐technical skills thanks to frameworks like the SHELL (software, hardware, environment, liveware) model, Oxford NOTECHS (non‐technical Skills) and ANTS (anaesthetist's non‐technical skills) 43, 44, 45, but regarding positive interactions at work our tendency is, at best, to gratefully accept these and move on. Could we improve our safety culture and introduce some balance by discussing ‘great catches’ (a positive spin on the near miss), episodes of excellence or ‘always conditions’ 46?

Figure 4.

Institute for Healthcare Improvement framework for improving joy in work 38. Reproduced with permission.

This brings us to a definition of safety culture. The culture of an organisation is important, as it is logical that the success of efforts to create safe systems is inherent in the behaviours that support them. The Health and Safety Executive quote the Confederation of British Industry's description of safety culture as ‘the ideas and beliefs that all members of the organisation share about risk, accidents and ill health’ 47. Therefore, the description of the ‘ages’ of safety gives context to the current safety culture within safety‐focussed organisations.

Healthcare is similar, and the subject of safety culture in healthcare was discussed at a Health Foundation roundtable event in 2013 with experts in the field of patient safety. The event report offers the following description:

‘A safety culture in healthcare can be thought of as one where staff have positive perceptions of psychological safety, teamwork, and leadership, and feel comfortable discussing errors. In addition, there is a ‘collective mindfulness’ about safety issues, where leadership and front‐line staff take a shared responsibility for ensuring care is delivered safely’ 48, 49.

We believe that a strength of this definition is that it highlights the conditions needed to promote resilience. The report goes on to suggest that an active approach to safety must be developed with a focus on creating safety and not just identification of and measurement of harm.

Resilience and excellence – methodology and models

If we are to effectively manage our systems and create safety, it is logical that we must first properly understand how they work in order to recognise why problems occur. It is imperative that we measure quality and safety appropriately and accurately, which as mentioned previously 26 is arguably not happening currently.

Our traditional approaches to quantify safely (or risk) only tell part of the story; focusing on excellence in practice is also vital 50, 51. To understand things fully, a different approach is required, one that ‘gets under the skin’ of how people behave within systems of work and digs deeper into how their interactions ‘create safety’.

This requires qualitative approaches 52, 53, 54, 55, 56 such as that used by the ‘Sign up to Safety’ campaign launched by the Department of Health in 2014 57. The campaign focuses on improving safety by helping individuals and organisations create a ‘safety culture’ in the context of the limitations of the system described above and to better understand what we need to enable us to work safely. The current focus of the campaign is to find ways to encourage conversations about ‘work as done’. If this can be managed in a safe and supportive way, without fear of retribution when this deviates from ‘work as imagined’, then we can learn from these differences and use both examples of success and failure to improve.

With the above definition of resilience, how can we identify examples of everyday performance variability that contribute to good outcomes? If our current focus on safety only captures examples of when safety is lacking, can we learn from examples of good practice to find and fix problems and generate further examples of standardised processes and policies? A possible answer may emerge from many of the positive reporting systems emerging in healthcare. Initially described in Birmingham 58, the Learning from Excellence initiative is designed to capture examples of individual good practice, or the system working despite challenging and variable circumstances. This appears to offer a simple but potentially effective approach to improving quality and safety. Pilot data suggest that rates of best‐practice antibiotic prescriptions increased when positive feedback from reports occurred 59. In contrast to focussing on finding and fixing errors, this asset‐focussed approach is being used in quality improvement methodology in a Health Foundation funded project, positive reporting and appreciative inquiry in sepsis 60.

Noticing and showing appreciation for good work also has the potential to help staff feel valued and improve engagement, potentially fostering ‘joy in work’ 38. As the concepts of Safety‐2 and resilience have become more commonplace, so have positive reporting systems. Since 2014, the initiative has spread to over 100 other organisations in the NHS. Some organisations use the terminology Learning from Excellence, but variation in nomenclature exists with ‘Favourable Event Reporting Forms’ in Southampton, ‘Sharing Outstanding Excellence’ in Salisbury 61, ‘Excellence Reporting’ in County Durham 62 and ‘Greatix’ in the East Midlands 63. The practicalities of the systems vary, with some organisations using paper reporting systems; they all provide a means for noticing, appreciating and giving feedback on good practice to staff involved.

Although a Safety‐2 approach to improving safety in healthcare is relatively new, studying success is less so. Two similar strengths‐based approaches are increasingly being used to identify what is working within systems; Appreciative Inquiry and Positive Deviance. The philosophy behind Appreciative Inquiry is that human systems move in the direction of what they study 64. Studying examples of what is working therefore provide insights into how to improve and develop further, such as improving handover by identifying what factors make this work well 65.

Appreciative Inquiry methodology is a natural fit for positive reporting systems and has been adopted for investigation of Learning from Excellence reports. One example of this reverses the current approach to root cause analysis, replacing the existing Serious Incidents Requiring Investigation meetings with a renamed ‘Improving Resilience, Inspiring Success’ approach 58. A strength of these meetings is that individuals and teams cocreate the improvement strategies for their areas of practice. Appreciative Inquiry can also be used outside positive reporting systems. Deficits or problems are reframed, and generative conversations create solutions based on what can be achieved 66. One author (EP) has used appreciative inquiry conversations to establish ‘what makes a good day’ with anaesthetic and intensive care colleagues in service development meetings with teams and during study days. An example of an appreciative conversation can be seen in Fig. 5.

Figure 5.

An example of an appreciative conversation. Taken from EP's work with appreciating people and reproduced with permission.

Positive Deviance is similar in its philosophy to Appreciative Inquiry. It harnesses variation in a system to drive improvement and involves identifying helpful adaptations ‘positive deviants’ to generate hypotheses about improvement methodologies. This approach has been advocated in a patient safety setting, with examples of improving hand hygiene and improving ‘door‐to‐balloon’ time for treatment of acute myocardial infarction 67.

Critics of these positive approaches might feel uncomfortable with the absence of criteria to define what constitutes excellence, but this would seem to be a strength of the systems. If we wish to better understand what makes a system perform well under pressure and identify novel approaches to improvement, we need to allow freedom to describe the system when it is working. Perhaps this reflects a reluctance to accept that ‘work as done’ can vary from ‘work as imagined’, as well as the ingrained nature of our prevailing approach to safety. However, the repeated occurrence of never events (despite patient safety alerts), improved frameworks and procedures suggest that innovative strategies should be encouraged.

Conclusion

The unspoken expectation is that healthcare practitioners of every profession are to undertake three roles. The first is to undertake the clinical function for which they are engaged, whatever that might be. The second is to not only maintain and enhance patient safety in their own work but also by intervening as necessary in the organisational systems they work within. The third is to seek out opportunities for improving quality and make sure that positive changes are made. We hope that our review has contributed to understanding how these roles intersect and has provided conceptual and practical tools for making sense of some of the demands of the politicised activity that is modern healthcare.

Acknowledgements

EP's work on Learning from Excellence is supported through funding from the West Midlands Patient Safety Collaborative. AS is an Editor of Anaesthesia.

You can respond to this article at http://www.anaesthesiacorrespondence.com

The copyright line for this article was changed on 12 July 2019 after original online and print publication.

References

- 1. Smith AF, Carlisle JC. Reviews, systematic reviews and Anaesthesia. Anaesthesia 2015; 70: 644–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hale A, Hovden J. Management and culture: the third age of safety – a review of approaches to organisational aspects of safety, health and environment In: Feyer A, Williamson A, eds. Occupational injury: risk prevention and intervention. London, UK: Taylor and Francis, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Heinrich HW. Industrial accident prevention: a scientific approach. New York, NY: Mc Craw Hill, 1931. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Smith AF, Boult M, Woods I, Johnson S. Promoting patient safety through prospective risk identification: example from perioperative care. Quality and Safety in Health Care 2010; 19: 69–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hollnagel E. Safety‐I and Safety‐II: the past and future of safety management Aldershot, UK: Ashgate; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vincent C. Essentials of patient safety. 2012. http://www.chfg.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/Vincent-Essentials-of-Patient-Safety-2012.pdf (accessed 26/03/2018).

- 7. Reason J. Human error: models and management. British Medical Journal 2000; 320: 768–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Thomas AN, MacDonald JJ. A review of patient safety incidents reported as ‘severe’ or ‘death’ from critical care units in England and Wales between 2004 and 2014. Anaesthesia 2016; 71: 1013–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Arnot‐Smith J, Smith AF. Patient safety incidents involving neuromuscular blockade: analysis of the UK National Reporting and Learning System data from 2006 to 2008. Anaesthesia 2010; 65: 1106–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Maclennan A, Smith AF. An analysis of critical incidents relevant to paediatric anaesthesia reported to the UK National Reporting and Learning System, 2006–2008. Pediatric Anesthesia 2011; 21: 841–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Woods D, Cook R. Nine steps to move forward from error. Cognition, Technology and Work 2002; 4: 137–44. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bernard D, Hollnagel E. I want to believe: some myths about the management of industrial safety. Cognition, Technology and Work 2012; 16: 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Braithwaite J, Wears RL, Hollnagel E. Resilient health care: turning patient safety on its head. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 2015; 27: 419–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hollnagel E, Wears RL, Braithwaite J. From Safety‐I to Safety‐II: A White Paper. The Resilient Health Care Net : 2015. University of Southern Denmark, University of Florida, USA, and Macquarie University, Australia. https://www.england.nhs.uk/signuptosafety/wp-content/uploads/sites/16/2015/10/safety-1-safety-2-whte-papr.pdf (accessed 17/11/2018).

- 15. Wears RL. Standardisation and its discontents. Cognition, Technology and Work 2015; 17: 89–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Macrae C. Interfaces of regulation and resilience in healthcare In: Hollnagel E, Braithwaite J, Wears RL, eds. Resilient health care. Farnham, UK: Ashgate, 2013: 111–22. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Smith AF, Pope C, Goodwin D, Mort M. Interprofessional handover and patient safety in anaesthesia: observational study of handovers in the recovery room. British Journal of Anaesthesia 2008; 101: 332–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Komesaroff PA, Kerridge IH, Isaacs D, Brooks PM. The scourge of managerialism and the Royal Australasian College of Physicians. Medical Journal of Australia 2015; 202: 519–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. White SM, Griffiths R, Moppett IK. Standardising anaesthesia for hip fracture surgery. Anaesthesia 2016; 71: 1391–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Marshall SD, Pandit JJ. Radical evolution: the 2015 Difficult Airway Society guidelines for managing unanticipated difficult or failed tracheal intubation. Anaesthesia 2016; 71: 131–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pandit JJ, Matthews J, Pandit M. “Mock before you block”: an in‐built action‐check to prevent wrong‐side anaesthetic nerve blocks. Anaesthesia 2017; 72: 150–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Aase K, Nybo G. Organisational knowledge in high‐risk industries: supplementing model‐based learning approaches. International Journal of Learning and Intellectual Capital 2005; 2: 49–65. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Institute of Medicine . Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fischhoff B. Risk perception and communication unplugged: twenty years of process. Risk Analysis 1995; 15: 137–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yeung K, Dixon‐Woods M. Design‐based regulation and patient safety: A regulatory studies perspective. Social Science and Medicine 2010; 71: 502–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vincent C, Aylin P, Franklin BD, et al. Is health care getting safer? British Medical Journal 2008; 337: a2426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Vincent C, Amalberti R. Safer healthcare. Strategies for the real world. Heidelberg: Springer, 2016. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007%2F978-3-319-25559-0 (accessed 25/03/2018). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zwack J, Schweitzer J. If every fifth physician is affected by burnout, what about the other four? Resilience strategies of experienced physicians. Academic Medicine 2013; 88: 382–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Epstein RM, Krasner MS. Physician resilience: what it means, why it matters, and how to promote it. Academic Medicine 2013; 88: 301–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Farquhar M. For nature cannot be fooled. Why we need to talk about fatigue. Anaesthesia 2017; 72: 1055–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. McClelland L, Holland J, Lomas JP, Redfern N, Plunkett E. A national survey of the effects of fatigue on trainees in anaesthesia in the UK. Anaesthesia 2017; 72: 1069–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Riskin A, Erez A, Foulk TA, et al. The impact of rudeness on medical team performance: a randomized trial. Pediatrics 2015; 136: 487–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Porath C, Pearson C. The price of incivility. Harvard Business Review 2013; 91: 114–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Smith MA, Byrne AJ. ‘Help! I need somebody’: getting timely assistance in clinical practice. Anaesthesia 2016; 71: 755–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Beament T, Mercer SJ. Speak up! Barriers to challenging erroneous decisions of seniors in anaesthesia. Anaesthesia 2016; 71: 1332–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Greaves JD, Grant J. Watching anaesthetists work: using the professional judgement of consultants to assess the developing clinical competence of trainees. British Journal of Anaesthesia 2000; 84: 525–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Smith AF, Arfanis K. ‘Sixth sense’ for patient safety. British Journal of Anaesthesia 2013; 110: 167–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Perlo J, Balik B, Swensen S, Kabcenell A, Landsman J, Feeley D. IHI framework for improving joy in work. IHI white paper. Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2017. http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/IHIWhitePapers/Framework-Improving-Joy-in-Work.aspx (accessed 26/03/2018). [Google Scholar]

- 39. Shanafelt TD, Black CM, Bechamps G, et al. Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Annals of Surgery 2010; 25: 995–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pandit JJ. Deaths by horsekick in the Prussian army – and other ‘Never Events’ in large organisations. Anaesthesia 2016; 71: 7–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Moppett IK, Moppett SH. Surgical caseload and the risk of surgical Never Events in England. Anaesthesia 2016; 71: 17–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Smith MA, Smith AF. Better names for ‘Never Events’. Anaesthesia 2016; 71: 601–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hawkins FH. Human factors in flight (2nd Ed.). Aldershot, UK: Ashgate, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mishra A, Catchpole K, McCulloch P. The Oxford NOTECHS System: reliability and validity of a tool for measuring teamwork behaviour in the operating theatre. Quality and Safety in Health Care 2009; 18: 104–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Fletcher G, Flin R, McGeorge P, Glavin R, Maran N, Patey R. Anaesthetists’ Non‐Technical Skills (ANTS): evaluation of a behavioural marker system. British Journal of Anaesthesia 2003; 90: 580–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Shorrock S. Never/zero thinking. 2016. https://humanisticsystems.com/2016/02/27/neverzero-thinking/ (accessed 25/10/2018).

- 47. Health and Safety Executive Human Factors Briefing Note No. 7‐Safety Culture . 2012. http://www.hse.gov.uk/humanfactors/topics/07culture.pdf (accessed 14/08/2018).

- 48. Leonard M, Frankel A. How can leaders influence a safety culture? Health foundation. 2012. https://www.health.org.uk/publication/how-can-leaders-influence-safety-culture (accessed 14/08/2018).

- 49. The Health Foundation . Safety culture: What is it and how do we monitor and measure it? 2012. http://patientsafety.health.org.uk/sites/default/files/resources/safety_culture_-_what_is_it_and_how_do_we_monitor_and_measure_it.pdf (accessed 14/08/2018).

- 50. Smith AF. In search of excellence in anaesthesiology. Anesthesiology 2009; 110: 4–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Smith AF, Greaves JD. Beyond competence: defining and promoting excellence in anaesthesia. Anaesthesia 2010; 65: 184–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Vincent C. Social scientists and patient safety: critics or contributors? Social Science and Medicine 2009; 69: 1777–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Goodwin D, Pope C, Mort M, Smith AF. Access, boundaries and their effects: legitimate participation in anaesthesia. Sociology of Health and Illness 2005; 27: 855–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Mort M, Smith AF. Beyond Information: intimate relations in sociotechnical practice. Sociology 2009; 43: 215–31. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Shelton CL, Smith AF, Mort M. Opening up the black box: an introduction to qualitative research methods in anaesthesia. Anaesthesia 2014; 69: 270–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Charlesworth M, Mort M, Smith AF. An observational study of critical care physicians’ assessment and decision‐making practices in response to patient referrals. Anaesthesia 2017; 72: 80–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Sign up to safety. 2014. https://www.signuptosafety.org.uk/ (accessed 17/11/2018).

- 58. Kelly N, Blake S, Plunkett A. Learning from excellence in healthcare: a new approach to incident reporting. Archives of Disease in Childhood 2016; 101: 788–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Morley G, Kelly N, Plunkett A. G531 Learning from excellence: positive reporting to improve prescribing practice (PRIP). Archives of Disease in Childhood 2016; 101: A313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. The Health Foundation . Positive reporting and appreciative inquiry in sepsis (PRAISe). 2018. http://www.health.org.uk/programmes/innovating-improvement/projects/positive-reporting-and-appreciative-inquiry-sepsis-praise (accessed 25/10/2018).

- 61. Learning from Excellence . LFE Conference Posters. 2017. https://learningfromexcellence.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Sharing-Outstanding-Excellence-SOX-at-Salisbury-NHSFT.pdf (accessed 25/10/2018).

- 62. Hixson R, Mole S, Winnard J. Excellence reporting – Learning from ‘the good stuff’. Health Services Journal 2017. https://www.hsj.co.uk/patient-safety/excellence-reporting-learning-from-the-good-stuff/7021160.article (accessed 27/03/2018).

- 63. Sinton D, Lewis G, Roland D. Excellence reporting (Greatix): creating a different paradigm in improving safety and quality. Emergency Medical Journal 2016; 33: 901–2. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Cooperider D, Whitney D. Appreciative inquiry – a positive revolution in change (1st edn.)., Oakland, CA: Berrett‐Koehler Publishers; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Shendell‐Falik N, Feinson M, Mohr B. Enhancing patient safety: improving the patient handoff process through appreciative inquiry. Journal of Nursing Administration 2007; 37: 95–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Trajkovski S, Schmied V, Vickers M, Jackson D. Using appreciative inquiry to transform health care. Contemporary Nurse 2013; 45: 95–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Lawton R, Taylor N, Clay‐Williams R, Braithwaite J. Positive deviance: a different approach to achieving patient safety. BMJ Quality and Safety 2014; 23: 880–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]