Abstract

Aim

The current study determined survival, short‐term neonatal morbidity and predictors for death or adverse outcome of very preterm infants in Austria.

Methods

This population‐based cohort study included 5197 very preterm infants (53.3% boys) born between 2011 and 2016 recruited from the Austrian Preterm Outcome Registry. Main outcome measures were gestational age‐related mortality and major short‐term morbidities.

Results

Overall, survival rate of all live‐born infants included was 91.6% and ranged from 47.1% and 73.4% among those born at 23 and 24 weeks of gestation to 84.9% and 88.2% among infants born at 25 and 26 weeks to more than 90.0% among those with a gestational age of 27 weeks or more. The overall prevalence of chronic lung disease, necrotising enterocolitis requiring surgery, intraventricular haemorrhage Grades 3–4, and retinopathy of prematurity Grades 3–5 was 10.0%, 2.1%, 5.5%, and 3.6%, respectively. Low gestational age, low birth weight, missing or incomplete course of antenatal steroids, male sex, and multiple births were significant risk predictors for death or adverse short‐term outcome.

Conclusion

In this national cohort study, overall survival rates were high and short‐term morbidity rate was low.

Keywords: Preterm infants, Short‐term outcome, Survival

Abbreviations

- CLD

Chronic lung disease

- GA

Gestational age

- IVH

Intraventricular haemorrhage

- NEC

Necrotising enterocolitis

- ROP

Retinopathy of prematurity

- SGA

Small for gestational age

Key notes.

This study determined survival, short‐term morbidities and predictors for adverse outcome of very preterm infants in Austria.

Overall survival rate of all live‐born infants included in the Network was high at 91.6% and prevalence of short‐term morbidities was low.

Low gestational age, low birth weight, missing or incomplete course of antenatal steroids, male sex and multiple births were significant risk predictors for death or adverse short‐term outcome.

Introduction

Advances in perinatal and neonatal care have gradually improved survival of very preterm infants. However, disability rates remain significant, especially among the most immature babies 1, 2. Since countries vary substantially in healthcare systems, in provision of proactive care for extremely preterm babies and available resources, national data are important for clinicians regarding decision‐making and objective counselling of parents.

So far, last data on mortality and morbidities of extremely preterm infants for Austria was published in 2005 and included infants born between 1999 and 2001 3. Therefore, the Austrian Preterm Outcome Study Group was founded. The current national cohort study included all live‐born infants with a gestational age (GA) of 23 to 31 weeks born in Austria. There was only a very small number of infants with 22 weeks of gestation being treated in Austria.

Our aim was to report the rates of survival to discharge home and short‐term morbidities related to different GAs and to characterise risk predictors for death or adverse short‐term outcome in this national cohort.

Methods

The Austrian Preterm Outcome Study was based on data collected prospectively by the Austrian Preterm Outcome Study Network. The Network was established with the aim of reporting on survival and outcome in all live‐born very preterm infants born in this geographical region.

The Network comprises seven Level III (highest level) and 15 Level II (specialised for neonatal care) centres. All collaborators are listed at the end of the paper. In each centre, one neonatal study coordinator was responsible for data acquisition and quality control. Data were collected electronically with a secure interface that protected confidentiality and privacy of data.

For the current study, infants were included that were born alive with a GA between 23 + 0 and 31 + 6 weeks between 1 January 2011 and 31 December 2016 in Austria. Live birth was defined according to World Health Organization guidelines and refers ‘to the complete expulsion or extraction from its mother of a product of conception, irrespective of the duration of the pregnancy, which, after such separation, breathes or shows any other evidence of life' 4.

Ethics

The Austrian Preterm Outcome Registry is part of a governmental quality assessment programme for neonatal care in Austria. Assessment of outcome until school entry for all preterm infants with a GA less than 32 weeks is mandatory and based on the federal law promoting quality in health care. Anonymised data are centrally administered by Gesundheit Österreich GmbH, and scientific analyses are approved and supervised by an academic review board.

Neonatal data

GA was calculated from the first day of the last menstrual period. This was compared with assessment of GA by ultrasound scans performed before 24 weeks. A full course of antenatal steroids was considered as two doses with a 24 h interval, with the last dose administered more than 24 hours before birth. Small for gestational age (SGA) was defined as a birth weight less than the 10th percentile for GA 5.

Mortality

Overall mortality was defined as all deaths occurring after birth until discharge from hospital and included delivery room deaths and deaths on the neonatal intensive care unit.

Short‐term outcome

The following major short‐term morbidities were analysed: chronic lung disease (CLD) defined as oxygen dependence at 36 weeks postconceptional age, necrotising enterocolitis (NEC) defined according to Bell's criteria 6 and classified as medical by clinical symptoms and signs plus evidence of pneumatosis on abdominal x ray or defined as surgical NEC by histological evidence of NEC on surgical specimens of intestine, intraventricular haemorrhage (IVH) classified according to the method of Papile et al. 7, and retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) graded according to the international classification 8.

Adverse short‐time outcome

Adverse short‐time outcome was defined as development of any of the following diseases: CLD, severe NEC (requiring surgical treatment), severe IVH (Grades 3–4), or severe ROP (Grades 3–5).

Survival free of major complications

Survival free of major complications was defined as percentage of the cohort surviving without one of the four major short‐term morbidities contributing to an adverse short‐time outcome.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis were performed using SPSS software, version 24.0 for Windows (IBM; Armonk, New York, USA). Descriptive statistics are provided in percentages, if not otherwise stated. Survival rates are presented as percentages with 95% binomial confidence intervals. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for risk profiles for adverse short‐term outcome were calculated by logistic regression analysis. Parameters entered in the multivariate regression model were GA, birth weight, antenatal steroids, sex and multiple births. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. To account for clustering of multiple births odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were also calculated by a generalised linear model which was extended by generalised estimating equations. Parameters entered in this model were GA, birth weight, antenatal steroids and sex. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Over the six‐year period, there were 5843 live‐born infants with a GA between 23 + 0 and 31 + 6 weeks in Austria (data from the National Birth Registry). Data on 5197 live‐born infants (89%) were entered into the registry and hence included in our analysis. In more detail, data were 95% complete for the GA range between 24 and 29 weeks of gestation, and missing data were more common for infants at the border of viability, namely a GA of 23 weeks (73% participation rate) and for infants with a GA of 30 and 31 weeks (participation rates of 84% and 74%), who were less likely admitted to one of the 22 participating centres.

Neonatal characteristics of infants born alive during the study period were summarised by year and by GA and are shown in Table 1a and b. There were no significant differences in use of antenatal corticosteroids, mode of birth, or infants born SGA over the six‐year period. There was a significant decrease in number of multiple births during the study period (p = 0.045; Table 1a). The most immature babies with a GA of 23 weeks had a low rate of lung maturation with only 38.5% having received a completed course of antenatal steroids. The rates of mortality and short‐term morbidities decreased with increasing GA (Table 1b).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and neonatal characteristics of preterm infants <32 weeks gestational age (a) by year, (b) gestational age

| (a) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics N (%) | Total | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 |

| Live births | 5197 (100.0) | 877 (16.9) | 853 (16.4) | 865 (16.6) | 914 (17.6) | 821 (15.6) | 867 (16.7) |

| Male sex | 2769 (53.3) | 463 (52.8) | 456 (53.5) | 465 (53.8) | 489 (53.5) | 441 (53.7) | 455 (52.5) |

| Mortality | 436 (8.4) | 65 (7.4) | 72 (8.4) | 64 (7.4) | 55 (6.0) | 113 (13.8) | 67 (7.7) |

| SGA | 667 (12.8) | 111 (12.7) | 110 (12.9) | 123 (14.2) | 117 (12.8) | 100 (12.2) | 106 (12.2) |

| Multiple births | 1677 (32.3) | 311 (35.5) | 266 (31.2) | 309 (35.7) | 282 (30.9) | 248 (30.2) | 261 (30.1) |

| Caesarean section | 4321 (83.1) | 735 (83.8) | 711 (83.4) | 732 (84.6) | 752 (82.3) | 674 (82.2) | 717 (82.7) |

| Antenatal steroids – incomplete course | 1056 (20.3) | 180 (20.5) | 168 (19.7) | 216 (25.0) | 180 (19.7) | 140 (17.1) | 172 (19.8) |

| Antenatal steroids – complete course | 3346 (64.4) | 563 (64.2) | 539 (63.2) | 541 (62.5) | 595 (65.1) | 524 (66.0) | 566 (65.3) |

| IVH (all) | 906 (17.4) | 190 (21.7) | 158 (18.5) | 142 (16.4) | 150 (16.4) | 130 (15.8) | 136 (15.7) |

| Severe IVH (Grades 3–4) | 285 (5.5) | 60 (6.8) | 57 (6.7) | 40 (4.6) | 38 (4.2) | 43 (5.2) | 47 (5.4) |

| NEC | 208 (4.0) | 31 (3.5) | 30 (3.5) | 34 (3.9) | 35 (3.8) | 36 (4.4) | 42 (4.8) |

| Severe NEC | 111 (2.1) | 14 (1.6) | 14 (1.6) | 17 (2.0) | 20 (2.2) | 22 (2.7) | 24 (2.8) |

| CLD | 518 (10.0) | 93 (10.6) | 82 (9.6) | 99 (11.4) | 96 (10.5) | 67 (8.2) | 81 (9.3) |

| ROP (all) | 999 (19.2) | 156 (17.8) | 148 (17.4) | 170 (19.7) | 174 (19.0) | 167 (20.3) | 184 (21.2) |

| Severe ROP (Grades 3–5) | 187 (3.6) | 45 (5.1) | 36 (4.2) | 38 (4.4) | 28 (3.1) | 10 (1.2) | 30 (3.5) |

| (b) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics N (%) | Total | Gestational age, weeks | ||||||||||

| 23–27 | 28–31 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | ||

| Live births | 5197 (100.0) | 1771 (34.1) | 3426 (65.9) | 187 (3.6) | 297 (5.7) | 331 (6.4) | 422 (8.1) | 534 (10.3) | 662 (12.7) | 757 (14.6) | 941 (18.1) | 1066 (20.5) |

| Male sex | 2769 (53.3) | 966 (54.5) | 1803 (52.6) | 104 (55.6) | 156 (52.5) | 180 (54.4) | 232 (55.0) | 294 (55.1) | 361 (54.5) | 393 (51.9) | 497 (52.8) | 552 (51.8) |

| Mortality | 436 (8.4) | 316 (17.8) | 120 (3.5) | 99 (52.9) | 79 (26.6) | 50 (15.1) | 50 (11.8) | 38 (7.1) | 22 (3.3) | 24 (3.2) | 38 (4.0) | 36 (3.4) |

| SGA | 667 (12.8) | 224 (12.6) | 443 (12.9) | 23 (12.3) | 33 (11.1) | 38 (11.5) | 59 (14.0) | 71 (13.3) | 91 (13.7) | 94 (12.4) | 123 (13.1) | 135 (12.7) |

| Multiple births | 1677 (32.3) | 465 (26.3) | 1212 (35.4) | 56 (29.9) | 66 (22.2) | 98 (29.6) | 102 (24.2) | 143 (26.8) | 215 (32.5) | 252 (33.3) | 324 (34.4) | 421 (39.5) |

| Caesarean section | 4321 (83.1) | 1404 (79.3) | 2917 (85.1) | 87 (46.5) | 232 (78.1) | 281 (84.9) | 360 (85.3) | 444 (83.1) | 571 (86.3) | 654 (86.4) | 800 (85.0) | 892 (83.7) |

| Antenatal steroids – incomplete course | 1056 (20.3) | 381 (21.5) | 675 (19.7) | 61 (32.6) | 70 (23.6) | 76 (23.0) | 94 (22.3) | 80 (15.0) | 122 (18.4) | 140 (18.5) | 183 (19.4) | 230 (21.6) |

| Antenatal steroids – complete course | 3346 (64.4) | 1103 (62.3) | 2243 (65.5) | 72 (38.5) | 174 (58.6) | 212 (64.0) | 273 (64.7) | 372 (69.7) | 461 (69.6) | 517 (68.3) | 607 (64.5) | 658 (61.7) |

| IVH (all) | 906 (17.4) | 533 (30.1) | 373 (10.9) | 92 (49.2) | 126 (42.4) | 101 (30.5) | 101 (23.9) | 113 (21.2) | 106 (16.0) | 96 (12.7) | 103 (10.9) | 68 (6.4) |

| Severe IVH(Grades 3–4) | 285 (5.5) | 223 (12.6) | 62 (1.8) | 53 (28.3) | 51 (17.2) | 45 (13.6) | 35 (8.3) | 39 (7.3) | 23 (3.5) | 20 (2.6) | 13 (1.4) | 6 (0.6) |

| NEC | 208 (4.0) | 137 (7.7) | 71 (2.1) | 22 (11.8) | 31 (10.4) | 24 (7.3) | 43 (10.2) | 17 (3.2) | 21 (3.2) | 18 (2.4) | 23 (2.4) | 9 (0.8) |

| Severe NEC | 111 (2.1) | 78 (4.4) | 33 (1.0) | 13 (7.0) | 19 (6.4) | 11 (3.3) | 25 (5.9) | 10 (1.9) | 9 (1.4) | 9 (1.2) | 10 (1.1) | 5 (0.5) |

| CLD | 518 (10.0) | 409 (23.1) | 109 (3.2) | 51 (27.3) | 103 (34.7) | 108 (32.6) | 75 (17.8) | 72 (13.5) | 54 (8.2) | 31 (4.1) | 15 (1.6) | 9 (0.8) |

| ROP (all) | 999 (19.2) | 737 (41.6) | 262 (7.6) | 69 (36.9) | 165 (55.6) | 187 (56.5) | 158 (37.4) | 158 (29.6) | 107 (16.2) | 78 (10.3) | 54 (5.7) | 23 (2.2) |

| Severe ROP (Grades 3–5) | 187 (3.6) | 165 (9.3) | 22(0.6) | 36 (19.3) | 62 (20.9) | 30 (9.1) | 25 (5.9) | 12 (2.2) | 10 (1.5) | 6 (0.8) | 4 (0.4) | 2 (0.2) |

CLD, chronic lung disease; IVH, intraventricular haemorrhage; NEC, necrotising enterocolitis; ROP, retinopathy of prematurity; SGA, small for gestational age.

Mortality

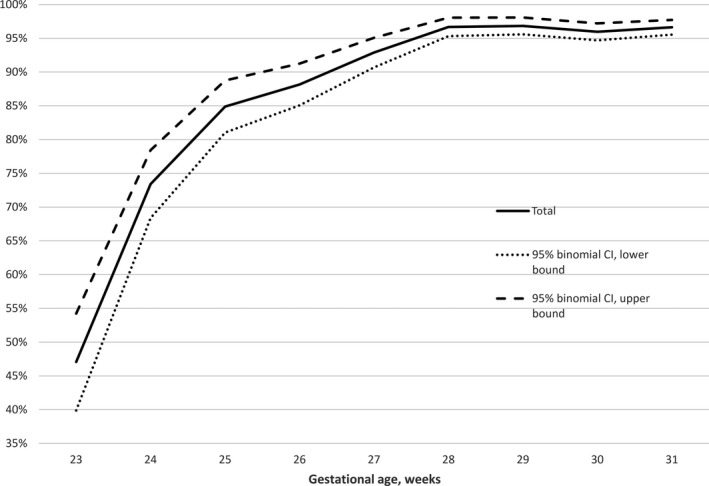

Of 5197 live‐born infants, 436 (8.4%) died during the study period (2011–2016). There was no significant decrease in mortality over this six‐year period. Death rates in infants having 23, 24, 25, 26, and 27 weeks of gestation were 52.9%, 26.6%, 15.1%, 11.8%, 7.1%, respectively. Corresponding death rates for infants having a GA of 28, 29, 30, and 31 weeks were 3.3%, 3.2%, 4.0% and 3.4%, respectively. There was no significant difference in death rate between males and females (9.2% vs. 7.6%, p = 0.07). Survival percentages and 95% confidence intervals by GA are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Survival to discharge plotted against gestational age.

Adverse short‐term outcome

The overall prevalence of major morbidities was 10.0% for CLD, 2.1% for severe NEC, 5.5% for IVH Grades 3–4, and 3.6% for ROP Grades 3–5. Prevalence of adverse short‐term outcome ranged from 55.6% in infants with 23 weeks of gestation to 13.1% in those with 28 weeks and 1.9% in infants with 31 weeks of gestation (Table 2). There was no significant change in adverse short‐term outcome over the six‐year period (p = 0.531). The overall rate of death or adverse short‐term outcome was 21.8% ranging from 86.1% to 4.9% according to GA (Table 2).

Table 2.

Short‐term outcomes of preterm infants <32 weeks gestational age 2011–2016

| Total | Gestational age, weeks | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 23–27 | 28–31 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | |||

| Adverse short‐term outcome | N (%) | 860 (16.5) | 654 (36.9) | 206 (6.0) | 104 (55.6) | 168 (56.6) | 150 (45.3) | 121 (28.7) | 111 (20.8) | 87 (13.1) | 59 (7.8) | 40 (4.3) | 20 (1.9) |

| Death or adverse short‐term outcome | N (%) | 1132 (21.8) | 829 (46.8) | 303 (8.8) | 161 (86.1) | 208 (70.0) | 175 (52.9) | 153 (36.3) | 132 (24.7) | 100 (15.1) | 80 (10.6) | 71 (7.5) | 52 (4.9) |

| Alive with adverse short‐term outcome | N (%) | 696(13.4) | 513 (29.0) | 183 (5.3) | 62 (33.2) | 129 (43.4) | 125 (37.8) | 103 (24.4) | 94 (17.6) | 78 (11.8) | 56 (7.4) | 33 (3.5) | 16 (1.5) |

| Survival free of major complications | N (%) | 4065 (78.2) | 942 (53.2) | 3123 (91.2) | 26 (13.9) | 89 (30.0) | 156 (47.1) | 269 (63.7) | 402 (75.3) | 562 (84.9) | 677 (89.4) | 870 (92.5) | 1014 (95.1) |

Adverse short‐time outcome (CLD, severe NEC, severe IVH, or severe ROP); survival free of major complications (survival without CLD, severe NEC, severe IVH, or severe ROP).

In a multivariate approach low GA, low birth weight, missing or incomplete course of antenatal steroids, male sex and multiple births were significant risk predictors for death or adverse short‐term outcome (Table 3). When using the generalised linear model to account for clustering of multiple births results were almost identical to those obtained by logistic regression analysis.

Table 3.

Multivariate association between risk variables and death or adverse short‐term outcome (severe IVH ≥3, severe NEC, ROP ≥3, or CLD) in preterm infants <32 weeks gestational age 2011–2016

| Variable | Univariate | Multivariate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p value | OR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Low gestational age (one‐week decrement) | 1.76 (1.70–1.83) | <0.001 | 1.49 (1.40–1.56) | <0.001 |

| Low birth weight (100 g decrement) | 1.43 (1.39–1.47) | <0.001 | 1.16 (1.12–1.21) | <0.001 |

| Antenatal corticosteroids (no or incomplete vs. complete course) | 1.62 (1.40–1.86) | <0.001 | 1.60 (1.35–1.89) | <0.001 |

| Male sex (vs. female) | 1.34 (1.17–1.53) | <0.001 | 1.50 (1.27–1.77) | <0.001 |

| Multiple births | 1.49 (1.30–1.73) | <0.001 | 1.22 (1.02–1.46) | 0.029 |

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio derived from logistic regression analysis of risk variables for adverse short‐term outcome.

The multivariate model [Chi‐square (5) = 1312.596; p < 0.001; included in analysis N = 4888] was fitted with a forward stepwise selection procedure.

Survival free of major complications

Overall survival free of major short‐term morbidity was 78.2%. Rates of survival without adverse short‐time outcome by gestational weeks are shown in Table 2 and ranged from 13.9% at 23 weeks to up to 95.1% at 31 weeks and did not significantly increase between 2011 and 2016.

Discussion

In this population‐based cohort of very preterm‐born infants studied between 2011 and 2016, the overall survival rate of live‐born infants was 91.6%. Survival rate in the extremely preterm age group (GA 23–27 weeks) was also high, starting at a 47.1% in infants with a GA of 23 weeks and rising steeply to 85% in infants with 25 weeks of gestation (Fig. 1). Compared to the data from Austria from 1999–2001 3 there was improvement in all aspects, now there is less mortality and less morbidity within the reported population. However, there was no further reduction in mortality and morbidity during the study period which might probably be due to a time interval of six years only. In a recent paper from Switzerland, Chen et al. reported on trends over a 13‐year period and compared three time periods 9. Survival and severe ICH showed a significant improvement only when the periods 2000–2004 and 2009–2012 were compared, NEC and CLD remained the same.

Available studies of the outcomes of preterm infants have reported varying data on survival, especially regarding the extremely preterm group 1, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, ranging from 35% (18) to 70% (1), and from 59% (18) to 81% (1) for those at 25 weeks of gestation. Differences in care practices at the limit of viability 19, different study periods as well as different study cohorts (all births vs. all livebirths) may contribute to the variations in reported survival rates 20. Management of infants with 22 weeks of gestation is discussed controversially in literature, because survival to discharge is poor in many countries, nevertheless, there are some countries that showed improved survival for those infants 21. However, for babies born at 23 and 24 weeks weighing 500 g and above, survival for all births including stillbirth varies between 0% to 25% and 21% to 50% in five different European countries 22.

In our cohort, overall survival free of adverse short‐term outcome was 78.2% and overall prevalence of CLD, severe NEC, IVH Grades 3–4, and severe ROP was 10.0%, 2.1%, 5.5%, and 3.6%, respectively. In comparison to other studies, outcome results in the EPIPAGE‐2 (Etude Epidémiologique sur les Petits Ages Gestationnels 2) cohort 17 were similar, namely 82.9% survival free of severe neonatal morbidities for those born between 23 and 31 weeks of gestation. In EPIPAGE‐2, prevalence of severe CLD, severe NEC, severe IVH, and severe ROP was 8.0%, 3.7%, 5.3% and 1.2%, respectively 17. Other studies including only extremely preterm infants reported much higher rates of short‐term morbidities 10, 13. CLD, one of the most frequent complications in extremely preterm babies, was reported with a prevalence ranging from 25% (1) to 44% (13), and the prevalence of severe ROP showed ranges from 8% (9) to 34% (1). The lowest prevalence of severe IVH in extremely preterm infants (6.0% and 6.9%) was reported in a Swedish 12 and a Dutch 10 study, respectively, as well as 5.3% reported in a study also including very preterm infants 17. The rate of NEC in high‐income countries was reported to range from 5% to 22% among babies with a birth weight < 1000 g 23. A recent international comparison between seven countries (Australia and New Zealand, Canada, Israel, Japan, Spain, Sweden and Switzerland) of infants admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit without major congenital malformation and born weighing less than 1500 g at 24–31 weeks of gestation showed great variations in adverse short‐time outcome (26%–42%) as well as overall mortality rate (5%–17%) and in each morbidity across these countries; for example, the country with the lowest mortality had the highest rate of treatment for ROP, and the country with the greatest mortality had a relatively low rate of CLD 24. However, when comparing these data to data from our cohort, both an overall mortality rate also including babies born at 23 weeks of GA of 8.4% as well as a rate of death or adverse short‐term of 21.8% in our cohort were within the lower ranges.

When calculating risk predictors for death or adverse short‐term outcome, not only low GA and low birth weight, but also missing or incomplete course of antenatal steroids, male sex, and multiple births were significantly associated with adverse outcome. Our findings are in accordance with the study conducted by Tyson et al. who found that the likelihood of a favourable outcome in extremely premature infants is dependent not only on GA, but also on birth weight, multiple births, sex, and exposure to antenatal corticosteroids 25. Regarding multiple births and mortality risk results of various studies differ, with some reporting similar risk rates 26, others showing no difference 27, or even a reduced risk for multiples 28.

Further implications

Even if a GA‐related mortality rate of 47.1% and a rate of adverse short‐term outcome of 55.6% for infants born with 23 weeks GA is low in comparison to other cohorts 9, 17, improvement in the care of the most immature babies is mandatory to further decrease overall mortality and morbidity rates. In addition, the overall rate of completed course of antenatal steroids of 65.3% has to be increased. Regarding a prevalence of 38.5% for babies with a GA of 23 weeks this is particularly true for the most immature babies, but also applies to the more mature ones. Considering the fact that missing or incomplete course of antenatal steroids was significantly associated with an increased risk for death or adverse short‐term outcome in our cohort this is of outmost importance.

Strengths and limitations of this study

A strength of the current study was the population‐based cohort design with a prospective enrolment of infants born very preterm. These outcomes have been reported infrequently, because most studies focus on extremely preterm infants only. Even though children born between 27 and 31 weeks of GA have a lower relative risk for adverse outcome, they make up a much larger proportion of preterm births and in absolute numbers they account for most children with deficits 29. This study gives the first description of short‐term outcome of very preterm infants born in Austria.

Our study had some limitations. Only 89% of all live‐born very preterm infants in the Austrian Preterm Birth Cohort were able to be included in the Austrian Preterm Outcome Registry. Considering the fact that data entry was based on voluntariness and no funding was available for individual centres, the inclusion rate seems adequate and is comparable to other studies: missing data in other population studies ranged from 3% in the Israel Neonatal Network to up to more than 40% in the Neonatal Research Network of Japan 24. However, more favourable outcomes might entail a selection bias, which is a well‐known limitation of population‐based studies. This is especially true for infants born at the border of viability. In addition, delivery room mortality could not be extracted from our mortality data. Therefore, live births where therapy was withheld in the further course were also included in our death rates. On the other hand, variation in the classification whether delivery room death was recorded as a stillbirth or as a live birth cannot be excluded and might also have an impact on the observed neonatal mortality rate. The EPIPAGE cohort study, a comparable population‐based study including all infants born before 33 weeks of GA, showed an overall difference in survival rates of 8% for the whole cohort and about 20% for the lower GA groups depending on whether all births or all live births were included 11. To further improve data quality of the Austrian Preterm Outcome Study Network all births including stillbirths will be documented in the database from 2019 onwards.

To compare our outcome data to those of other populations, the Austrian healthcare system and policy on treatment of very preterm infants must be taken into account. According to national guidelines, proactive care is offered to extremely preterm babies with a gestational age of 23 weeks or older 30. Prenatal care in Austria is well structured, free of charge and accessible for every pregnant woman. For uncomplicated pregnancies and term deliveries at least five well‐documented health check‐ups during pregnancy are necessary to qualify for financial benefit. Also perinatal and neonatal health care including intensive care is accessible without additional costs for every baby. This health system may lead to better care in pregnancy and in the neonatal period and might also be one explanation for the overall favourable outcome data.

Conclusion

Our population‐based study from Austria of very preterm infants showed mortality and also short‐term morbidity rates low in regard to literature. These national data provide additional information to help make appropriate recommendations in treatment and can help further improve outcome of very preterm babies.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Funding

The study was supported by a grant of the ‘Gemeinsame Gesundheitsziele aus dem Rahmen Pharmavertrag' of the ‘Main Association of the Austrian Social Insurance Carriers'.

Acknowledgement

We thank Hermann Leitner, MSc, main coordinator of the National Birth Registry, for his valuable help regarding the study database.

Appendix 1. Collaborators

The following doctors and hospitals participated in the Austrian Preterm Outcome Study group: Medical University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria (Angelika Berger); Sozialmedizinsches Zentrum Ost, Donauspital, Vienna, Austria (Herbert Kurz); Kaiser‐Franz‐Josef‐Spital, Vienna, Austria (Günther Bernert); Wilhelminenspital, Vienna, Austria (Thomas Frischer); Rudolfstiftung Hospital, Vienna (Milen Minkov); Universtitätsklinikum St. Pölten, St. Pölten, Austria (Karl Zwiauer); Landesklinikum Wiener Neustadt, Wiener Neustadt, Austria (Doris Ehringer‐Schetitska); Universitätsklinikum Tulln, Tulln an der Donau, Austria (Hans Salzer); Landesklinikum Mistelbach, Mistelbach, Austria (Jutta Falger); Landesklinikum Zwettl, Zwettl, Austria (Zdenek Jaros); Krankenhaus Barmherzige Brüder Eisenstadt, Eisenstadt, Austria (Hans Peter Wagentristl); Krankenhaus Oberwarth, Oberwarth, Austria (Robert Bruckner, MD); Landeskrankenhaus Villach, Villach, Austria (Robert Birnbacher); Klinikum Klagenfurt am Wörthersee, Klagenfurt, Austria (Wilhelm Kaulfersch); Medical University of Graz, Graz, Austria (Berndt Urlesberger); Landeskrankenhaus Hochsteiermark, Leoben, Austria (Reinhold Kerbl); Kepler University Hospital, Linz, Austria (Gabriele Wiesinger‐Eidenberger); Klinikum Wels‐Grieskirchen, Wels, Austria (Martin Wald); Paracelsus Universität, Salzburg, Austria (Martin Wald); Kardinal Schwarzenberg Klinikum, Schwarzach, Austria (Josef Riedler); Medical University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria (Ursula Kiechl‐Kohlendorfer); Academic Teaching Hospital, Landeskrankenhaus Feldkirch, Feldkirch, Austria (Burkhard Simma).

The members of the Austrian Preterm Outcome Study Group are provided in Appendix 1.

Contributor Information

U Kiechl‐Kohlendorfer, Email: ursula.kohlendorfer@i-med.ac.at.

the Austrian Preterm Outcome Study Group:

Herbert Kurz, Günther Bernert, Thomas Frischer, Milen Minkov, Karl Zwiauer, Hans Salzer, Jutta Falger, Zdenek Jaros, Hans Peter Wagentristl, Robert Bruckne, Robert Birnbacher, Wilhelm Kaulfersch, Gabriele Wiesinger‐Eidenberger, and Josef Riedler

References

- 1. EXPRESS Group , Fellman V, Hellström‐Westas L, Norman M, Westgren M, Källén K, Lagercrantz H, et al. One‐year survival of extremely preterm infants after active perinatal care in Sweden. JAMA 2009; 301: 2225–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bolisetty S, Dhawan A, Abdel‐Latif M, Bajuk B, Stack J, Lui K, et al. Intraventricular hemorrhage and neurodevelopmental outcomes in extreme preterm infants. Pediatrics 2014; 133: 55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Weber Ch, Weninger M, Klebermass K, Reiter G, Wiesinger‐Eidenberger G, Brandauer M, et al. Mortality and Morbidity in extremely preterm infants (22 to 26 weeks of gestation): Austria 1999‐2001. Wien Klin Wochenschr 2005; 117: 740–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. World Health Organization . Health statistics and information systems. Maternal mortality ratio (per 100 000 live births). Available at: www.who.int/healthinfo/statistics/indmaternalmortality/en/.

- 5. Fenton TR, Kim JH. A systematic review and meta‐analysis to revise the Fenton growth chart for preterm infants. BMC Pediatr 2013; 13: 59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bell MJ, Ternberg JL, Feigin RD, Keating JP, Marshall R, Barton L, et al. Neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. Therapeutic decisions based upon clinical staging. Ann Surg 1978; 187: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Papile LA, Burstein J, Burstein R, Koffler H. Incidence and evolution of subependymal and intraventricular hemorrhage: a study of infants with birth weights less than 1500 gm. J Pediatr 1978; 92: 529–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Committee for the Classification of Retinopathy of Prematurity . An international classification of retinopathy of prematurity. Arch Ophthalmol 1984; 102: 1130–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chen F, Bajwa NM, Rimensberger PC, Posfay‐Barbe KM, Pfister RE; Swiss Neonatal Network . Thirteen‐year mortality and morbidity in preterm infants in Switzerland. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2016; 101: F377–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. de Waal CG, Weisglas‐Kuperus N, van Goudoever JB, Walther FJ; NeoNed Study Group ; LNF Study Group . Mortality, neonatal morbidity and two year follow‐up of extremely preterm infants born in the Netherlands in 2007. PLoS ONE 2012; 7: e41302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Larroque B, Breart G, Kaminski M, Marchand L, André M, Arnaud C, et al. Survival of very preterm infants: epipage, a population based cohort study. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2004; 89: F139–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Markestad T, Kaaresen PI, Ronnestad A, Reigstad H, Lossius K, et al. Early death, morbidity, and need of treatment among extremely premature infants. Pediatrics 2005; 115: 1289–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vanhaesebrouck P, Allegaert K, Bottu J, Debauche C, Devlieger H, et al. The EPIBEL study: outcomes to discharge from hospital for extremely preterm infants in Belgium. Pediatrics 2004; 114: 663–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Boland RA, Davis PG, Dawson JA, Doyle LW; Victorian Infant Collaborative Study Group . Predicting death or major neurodevelopmental disability in extremely preterm infants born in Australia. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2013; 98: F201–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Berger TM, Steurer MA, Woerner A, Meyer‐Schiffer P, Adams M; Swiss Neonatal Network . Trends and centre‐to‐centre variability in survival rates of very preterm infants (<32 weeks) over a 10‐year‐period in Switzerland. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2012; 97: F323–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Younge N, Goldstein RF, Cotten CM; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network . Survival and neurodevelopment of periviable infants. N Engl J Med 2017; 376: 1890–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ancel PY, Goffinet F; EPIPAGE‐2 Writing Group . Survival and morbidity of preterm children born at 22 through 34 weeks' gestation in France in 2011: results of the EPIPAGE‐2 cohort study. JAMA Pediatr 2015; 169: 230–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Field DJ, Dorling JS, Manktelow BN, Draper ES. Survival of extremely premature babies in a geographically defined population: prospective cohort study of 1994‐9 compared with 2000‐5. BMJ 2008; 336: 1221–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rysavy MA, Li L, Bell EF, Das A, Stoll BJ, Vohr BR, et al. Between‐hospital variation in treatment and outcomes in extremely preterm infants. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 1801–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Evans DJ, Levene MI. Evidence of selection bias in preterm survival studies: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2001; 84: F79–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kono Y, Yonemoto N, Nakanishi H, Kusuda S, Fujimura M. Changes in survival and neurodevelopmental outcomes of infants born at < 25 weeks gestation: a retrospective observational study in tertiary centers in Japan. BMJ Pediatrics Open 2018; 2: e000211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Smith LK, Blondel B, Van Reempts P, Draper ES, Manktelow BN, Barros H, et al. Variability in the management and outcomes of extremely preterm births across five European countries: a population‐based cohort study. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2017; 102: F400–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Battersby C, Santhalingam T, Costeloe K, Modi N. Incidence of neonatal necrotising enterocolitis in high‐income countries: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2018; 103: F182–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shah PS, Lui K, Sjörs G, Mirea L, Reichman B, Adams M, et al. Neonatal outcomes of very low birth weight and very preterm neonates: an international comparison. J Pediatr 2016; 177: 144–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tyson JE, Parikh NA, Langer J, Green C, Higgins RD, et al. Intensive care for extreme prematurity–moving beyond gestational age. N Engl J Med 2008; 358: 1672–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hoffman EL, Bennett FC. Birth weight less than 800 grams: changing outcomes and influences of gender and gestation number. Pediatrics 1990; 86: 27–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nielsen HC, Harvey‐Wilkes K, MacKinnon B, Hung S. Neonatal outcome of very premature infants from multiple and singleton gestations. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1997; 177: 653–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Draper ES, Manktelow B, Field DJ, James D. Prediction of survival for preterm births by weight and gestational age: retrospective population based study. BMJ 1999; 319: 1093–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Larroque B, Ancel PY, Marret S, Marchand L, André M, Arnaud C, et al. Neurodevelopmental disabilities and special care of 5‐year‐old children born before 33 weeks of gestation (the EPIPAGE study): a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet 2008; 371: 813–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Berger A, Kiechl‐Kohlendorfer U, Berger J, Dilch A, Kletecka‐Pulker M, Urlesberger B, et al. Erstversorgung von Frühgeborenen an der Grenze der Lebensfähigkeit. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd 2016; 165: 139–47 (German). [Google Scholar]